Unlocking Nature's Pharmacy: How In Silico ADMET is Revolutionizing Natural Product Research

This article explores the transformative role of in silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling in natural product-based drug discovery.

Unlocking Nature's Pharmacy: How In Silico ADMET is Revolutionizing Natural Product Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of in silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling in natural product-based drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it details how computational methods overcome historical bottlenecks such as limited compound availability, complex mixtures, and costly experimental testing. The discussion spans foundational concepts, key methodologies like machine learning and molecular dynamics, practical strategies for troubleshooting, and rigorous validation techniques. By providing a comprehensive roadmap, this article demonstrates how integrating computational predictions early in the research pipeline de-risks development and accelerates the identification of viable natural product-derived therapeutics.

The In Silico Advantage: Overcoming Fundamental Challenges in Natural Product Research

Why Natural Products Are Problematic for Traditional ADMET Testing

In pharmaceutical development, the failure of drug candidates due to unfavorable Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties remains a primary cause of clinical attrition. Approximately 40–45% of clinical failures are attributed to poor ADMET characteristics, representing enormous financial losses and inefficiencies in the drug development pipeline [1]. While this problem affects all drug candidates, natural products present unique and formidable challenges for traditional ADMET testing methodologies. These challenges have prompted a significant shift toward in silico approaches that can overcome the limitations of conventional experimental protocols.

Natural products have long been recognized as invaluable sources of therapeutic agents, with approximately 40-50% of approved drugs originating from or inspired by natural compounds [2]. Their chemical diversity and structural complexity offer tremendous therapeutic potential, yet these very characteristics create substantial obstacles for systematic ADMET evaluation using traditional methods. This technical guide examines the fundamental challenges natural products pose to conventional ADMET testing and explores how computational approaches are revolutionizing this critical phase of drug development.

Distinctive Characteristics of Natural Products

Natural products differ significantly from synthetic molecules in their structural and physicochemical properties, which directly impact their behavior in biological systems. Understanding these differences is essential for appreciating why they complicate traditional ADMET testing protocols.

Structural Complexity and Diversity

Compared to synthetic compounds, natural products exhibit greater structural complexity with more chiral centers, increased oxygen content, and less aromatic character [3] [4]. They tend to be larger molecular weight compounds with higher numbers of rotatable bonds and more diverse functional group arrangements. This complexity stems from their evolutionary biosynthesis in biological systems, resulting in three-dimensional architectures that are often difficult to characterize fully and expensive to synthesize in sufficient quantities for comprehensive testing.

Physicochemical Properties

Natural products frequently violate conventional drug-likeness rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, yet many demonstrate favorable bioavailability and therapeutic effects through alternative absorption mechanisms [3]. They typically contain greater oxygen content and less nitrogen, sulfur, and halogens than synthetic molecules, contributing to their distinct pharmacokinetic profiles [4]. This deviation from established pharmaceutical norms complicates prediction using traditional models calibrated primarily for synthetic compound libraries.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | High (more chiral centers, complex stereochemistry) | Generally lower |

| Molecular Weight | Often higher | Typically optimized for drug-likeness |

| Oxygen Content | Higher | Lower |

| Nitrogen/Sulfur Content | Lower | Higher |

| Compliance with Rule of Five | Often violated | Typically compliant |

| Chemical Stability | Often lower (sensitive to environment) | Generally higher |

Fundamental Challenges for Traditional ADMET Testing

Material Availability and Complexity

The limited availability of many natural products represents a primary constraint for experimental ADMET assessment. Numerous plant-derived compounds can only be isolated in milligram quantities insufficient for comprehensive testing [3]. This scarcity is compounded by the fact that natural products often exist as complex mixtures where multiple constituents may interact synergistically or antagonistically, making it difficult to attribute ADMET properties to individual components [5].

Experimental assessment of natural products is further complicated by their chemical instability. Many natural compounds are highly sensitive to environmental factors including temperature, moisture, oxygen, and pH variations, resulting in limited shelf-life and difficulties in developing stable commercial products [3] [4]. This instability introduces significant variability into experimental results and requires specialized handling conditions that increase the cost and complexity of testing.

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Traditional ADMET testing relies heavily on in vitro models that may inadequately capture the complex behavior of natural products in human systems. For example, cell models like Caco-2 (for intestinal absorption prediction) and MDCK (for blood-brain barrier penetration) provide useful but simplified representations of biological barriers [5]. These systems often fail to account for the metabolic transformations and transporter interactions that significantly influence natural product disposition [5].

The growing imperative to reduce animal use in medical research further limits traditional testing approaches [3] [4]. While in vivo models provide the most physiologically relevant ADMET data, ethical concerns and regulatory restrictions have substantially constrained their application. This reduction in animal testing capacity has created a critical gap in experimental ADMET assessment that computational approaches are increasingly filling.

Economic and Temporal Constraints

Traditional experimental ADMET evaluation is both time-consuming and expensive, with comprehensive profiling of a single compound often requiring weeks to months and costing tens of thousands of dollars [3]. The high-throughput screening used for synthetic compound libraries is rarely feasible for natural products due to their structural complexity, limited availability, and specialized handling requirements [2].

The typical drug discovery and development timeline spans 10-15 years, with ADMET complications representing a major contributor to this extended timeframe [6]. The pharmaceutical industry has consequently shifted toward earlier ADMET screening to identify and eliminate problematic compounds before significant resources are invested, creating demand for rapid, cost-effective predictive methods suitable for natural products [6].

In Silico Solutions for Natural Product ADMET Challenges

Computational ADMET prediction methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional experimental approaches, offering particular advantages for natural products research. These methods can effectively address many of the challenges associated with natural product complexity, scarcity, and instability.

Key Computational Methodologies

Quantum Mechanics and Molecular Mechanics Methods

Quantum mechanics (QM) and molecular mechanics (MM) calculations provide insights into molecular interactions, reactivity, and metabolic transformations at the atomic level [3] [4]. QM/MM simulations have been successfully applied to study enzyme-mediated metabolism of natural compounds, such as cytochrome P450-catalyzed transformations, providing mechanistic understanding of metabolic stability and regioselectivity [4]. These methods are particularly valuable for predicting metabolic soft spots and understanding the molecular basis of ADMET properties.

Molecular Docking and Dynamics

Molecular docking predicts interactions between natural products and biological targets such as metabolic enzymes and transporters [7] [4]. Molecular dynamics simulations extend these predictions by modeling the time-dependent behavior of these complexes, providing insights into binding stability and conformational changes [4]. These approaches have been widely applied to natural products, as exemplified by studies of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from traditional medicines [7].

QSAR and Machine Learning Models

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models correlate structural features of natural products with specific ADMET endpoints [6]. With advances in machine learning, these approaches have evolved into sophisticated predictive tools using algorithms such as random forests, support vector machines, and neural networks [8] [6]. These models can identify patterns across diverse chemical structures, making them particularly suitable for natural product libraries with broad structural diversity.

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Natural Product ADMET Prediction

| Methodology | Primary Applications | Advantages for Natural Products |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics | Metabolic prediction, reactivity assessment | Atomic-level insight into metabolic transformations |

| Molecular Docking | Protein-ligand interactions, transporter effects | Identification of binding modes without physical samples |

| Molecular Dynamics | Binding stability, conformational changes | Time-dependent behavior of molecular complexes |

| QSAR/Machine Learning | Property prediction from structural features | Pattern recognition across diverse chemical space |

| PBPK Modeling | Whole-body pharmacokinetic simulation | Integration of multiple ADME processes |

| Federated Learning | Multi-institutional model training | Expands chemical space without data sharing |

Federated Learning for Expanded Chemical Coverage

A particularly innovative approach to addressing the data limitations of natural product ADMET prediction is federated learning, which enables collaborative model training across multiple institutions without centralizing sensitive proprietary data [1]. This method systematically alters the geometry of chemical space that a model can learn from, improving coverage and reducing discontinuities in the learned representation [1].

Federated learning has demonstrated significant advantages for natural product research, with studies showing that federated models systematically outperform local baselines, and performance improvements scale with the number and diversity of participants [1]. This approach is especially valuable for natural products research, where chemical space is vast but data for individual compounds is often limited across multiple research groups.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized In Silico ADMET Profiling Protocol

A robust workflow for computational ADMET assessment of natural products involves multiple stages of analysis and validation:

Data Collection and Curation: Compound structures are obtained from natural product databases (e.g., BIOFACQUIM, NuBBEDB, TCM Database) or experimental characterization [2]. Structures undergo cleaning, standardization, and format conversion (e.g., to SMILES notation) for computational analysis.

Descriptor Calculation: Molecular descriptors representing structural and physicochemical properties are calculated using tools such as SwissADME or pkCSM [2] [9]. These include constitutional descriptors, topological indices, electronic properties, and quantum chemical parameters.

Model Application: Predictive models are applied to estimate specific ADMET endpoints. This may involve consensus predictions from multiple algorithms to improve reliability [2].

Result Interpretation and Validation: Predictions are interpreted in the context of established drug-likeness criteria (e.g., Lipinski, Veber rules) and compared to available experimental data for validation [2] [9].

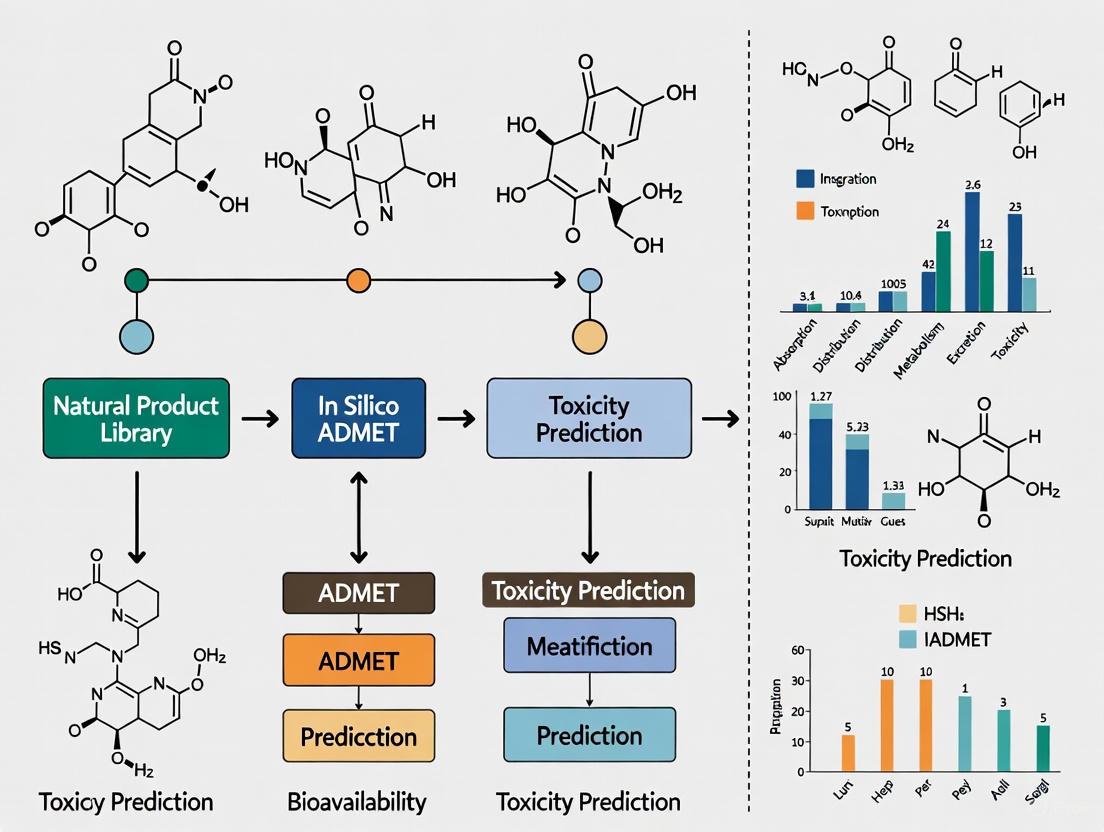

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard protocol for in silico ADMET profiling of natural products:

Machine Learning Model Development Workflow

For novel natural product libraries without established predictive models, a comprehensive machine learning workflow can be implemented:

Data Preprocessing: Cleaning, normalization, and feature selection to improve data quality and reduce irrelevant information [6].

Model Selection and Training: Application of appropriate algorithms (e.g., random forests, support vector machines, neural networks) using training datasets [6].

Validation and Optimization: Cross-validation techniques (e.g., k-fold validation) and hyperparameter optimization to enhance model accuracy and generalizability [6].

Independent Testing: Evaluation of optimized models using independent datasets to assess performance based on classification and regression metrics [6].

Successful implementation of in silico ADMET prediction for natural products requires familiarity with key software tools and databases. The following table summarizes essential resources for computational natural products research:

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Natural Product ADMET Research

| Resource Category | Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Databases | BIOFACQUIM, AfroDB, NuBBEDB, TCM Database | Source of natural product structures and metadata [2] |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | SwissADME, pkCSM | Comprehensive ADMET property prediction [2] [9] |

| Molecular Descriptor Software | PaDEL, RDKit, Dragon | Calculation of structural and physicochemical descriptors [6] |

| Docking and Simulation Tools | AutoDock, GROMACS, AMBER | Protein-ligand interaction modeling and molecular dynamics [3] [4] |

| Cheminformatics Workflows | KNIME, Orange | Data preprocessing, model building, and visualization [2] |

| Federated Learning Frameworks | kMoL, Apheris Platform | Collaborative model training without data sharing [1] |

Natural products present formidable challenges for traditional ADMET testing methodologies due to their structural complexity, limited availability, chemical instability, and deviation from conventional drug-like properties. These limitations have accelerated the adoption of computational approaches that can effectively predict ADMET properties without physical samples or extensive laboratory infrastructure.

In silico methods represent a paradigm shift in natural product ADMET assessment, offering rapid, cost-effective alternatives to traditional experimental approaches while avoiding many of their inherent limitations [3]. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, these approaches will play an increasingly central role in harnessing the therapeutic potential of natural products while minimizing the resource investments and ethical concerns associated with conventional testing methodologies.

The integration of computational ADMET prediction early in the natural product drug discovery pipeline promises to reduce late-stage attrition rates, accelerate development timelines, and ultimately bring promising natural product-derived therapies to patients more efficiently. For researchers working with natural products, familiarity with these computational approaches has become an essential component of modern drug discovery expertise.

The drug discovery landscape for natural products is fraught with unique challenges, including the limited availability of rare compounds, their inherent chemical instability, and the profound costs associated with experimental pharmacokinetic profiling [3] [10]. In silico ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) methods have emerged as a transformative solution, offering a paradigm shift in how researchers evaluate the developmental potential of natural compounds [11]. These computational approaches provide compelling advantages that align with the core needs of modern research and development: significant cost reduction, accelerated timelines, and the conservation of precious samples [3]. By leveraging computational power, scientists can now bypass many traditional bottlenecks, performing critical early-stage assessments without the need for physical substance, laboratory infrastructure, or animal models [3] [12]. This technical guide details the quantitative benefits of these methods and provides actionable protocols for their implementation within natural product research.

Quantitative Advantages of In Silico ADME

The benefits of integrating in silico methods into the natural product research workflow are substantial and measurable. The tables below summarize the core advantages and specific methodological comparisons.

Table 1: Core Benefits of In Silico vs. Experimental ADME for Natural Products

| Benefit Dimension | Traditional Experimental Approach | In Silico Approach | Impact on Natural Product Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | High (costly materials, reagents, laboratory operations) [3] | Very low (requires only computational resources) [3] [10] | Enables screening of rare/expensive compounds without financial risk |

| Speed | Weeks to months for data generation [3] | Minutes to hours for predictions [3] | Dramatically compresses early discovery timelines |

| Sample Conservation | Requires milligrams to grams of pure compound [3] | Requires zero physical sample (only structural formula) [3] | Permits study of compounds available in minuscule quantities |

| Throughput | Low to moderate (limited by assay capacity) | Very high (can screen thousands of compounds virtually) [13] | Ideal for profiling complex natural product libraries |

Table 2: In Silico ADME Methodologies and Their Applications

| Computational Method | Key Function in ADME Prediction | Example Application in Natural Products |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | Predicts chemical reactivity, stability, and metabolic pathways [3] [10] | Studying regioselectivity of CYP-mediated metabolism of estrone and equilenin [3] |

| Molecular Docking | Models binding affinity and interactions with enzymes (e.g., CYPs) and transporters [11] [14] | Virtual screening of 80,617 natural compounds to identify BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease [14] |

| QSAR & Machine Learning | Builds predictive models linking molecular structures to ADME properties [15] [16] | Bayer's in-house ADMET platform uses ML to guide lead selection and optimization [15] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates dynamic behavior of molecule-protein complexes over time [11] [14] | Assessing stability of a natural product-BACE1 inhibitor complex over a 100 ns simulation [14] |

| PBPK Modeling | Predicts compound concentration-time profiles in whole organisms [3] | - |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key In Silico Workflows

Protocol 1: Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking for Natural Product Prioritization

This protocol is designed to identify potential hit compounds from large libraries of natural products based on their predicted binding affinity to a target of interest.

Target Protein Preparation

- Source: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., BACE1, PDB ID: 6ej3) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank [14].

- Preparation: Using software like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard, process the protein by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning bond orders, correcting for missing residues, and optimizing the hydrogen-bonding network.

- Energy Minimization: Refine the structure by performing energy minimization using a force field (e.g., OPLS 2005) to relieve steric clashes and ensure geometric stability [14].

Natural Product Library Preparation

- Compound Sourcing: Curate a library of natural product structures from databases such as ZINC.

- Ligand Preparation: Use a tool like Schrödinger's LigPrep to generate 3D structures, assign protonation states at biological pH, generate possible tautomers, and perform energy minimization [14].

- Drug-Likeness Filtering: Apply filters like Lipinski's Rule of Five to focus on compounds with higher probability of oral bioavailability [14].

Molecular Docking Execution

- Grid Generation: Define the active site of the target protein by generating a grid around the co-crystallized ligand or known binding residues [14].

- Docking Run: Perform flexible ligand docking using a tool like GLIDE. A standard workflow often employs a multi-stage approach:

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS): Rapidly screen the entire library.

- Standard Precision (SP): Re-dock the top-ranking hits from HTVS for more accuracy.

- Extra Precision (XP): Apply a rigorous scoring function to the best SP compounds to identify the most promising leads [14].

- Analysis: Analyze the binding poses, focusing on docking scores (reported in kcal/mol) and specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-pi stacking) with key amino acid residues [14].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based ADMET Property Prediction

This protocol leverages machine learning models to predict key pharmacokinetic and toxicity endpoints for natural product candidates.

Data Collection and Curation

- Dataset Assembly: Compile a dataset of molecules with experimentally determined ADMET properties. This can be sourced from public databases or internal assays. The dataset must include the chemical structure (e.g., SMILES notation) and the corresponding experimental endpoint value (e.g., solubility, CYP inhibition) [15] [16].

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing data, remove duplicates, and address data imbalance. Crucially, ensure high data quality, as this is foundational for model performance [15].

Molecular Featurization

- Descriptor Calculation: Convert molecular structures into numerical descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological surface area) or more advanced representations like molecular fingerprints [15].

- Graph Representations: For deep learning models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), represent molecules as graphs where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [16].

Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, or Deep Neural Networks) based on the dataset size and problem type (classification or regression) [15] [17].

- Training: Train the model on a subset of the data to learn the relationship between molecular features and the ADMET endpoint.

- Validation: Evaluate the model's performance on a held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, or R² to ensure its predictive reliability [15].

Prediction and Interpretation

- Deployment: Use the trained model to predict ADMET properties for novel natural products.

- Explainability: Employ model interpretation techniques (e.g., attention mechanisms in models like OmniMol) to understand which structural features of the molecule contribute most to the prediction, providing valuable insights for chemists [16].

Diagram 1: In Silico-Enabled Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines key computational tools and resources that function as the essential "reagents" for conducting in silico ADME research on natural products.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for In Silico ADME

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC Database [14] | Compound Library | A freely accessible repository of commercially available compounds, including a vast collection of natural products for virtual screening. |

| Schrödinger Suite [14] | Software Platform | Provides an integrated environment for protein preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), ligand preparation (LigPrep), molecular docking (GLIDE), and molecular dynamics (Desmond). |

| SwissADME [18] [14] | Web Tool | Allows for the rapid prediction of key physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness of small molecules. |

| ADMETlab 2.0 [16] [14] | Web Tool | A comprehensive platform for predicting a wide array of ADMET and physicochemical properties using robust machine learning models. |

| Gaussian [18] | Software | Performs quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., DFT) to predict electronic properties, reactivity, and stability of natural compounds. |

| AutoDock [18] [13] | Software | A widely used, open-source package for molecular docking simulations to predict protein-ligand binding. |

| OmniMol [16] | AI Framework | A unified molecular representation learning framework for predicting multiple molecular properties from imperfectly annotated data. |

Diagram 2: In Silico ADME Method Taxonomy

The adoption of in silico ADME methods represents a strategic imperative for advancing natural product research. The quantifiable benefits of radical cost reduction, unparalleled speed, and complete sample conservation directly address the most pressing constraints in the field [3] [10]. As computational power and artificial intelligence continue to evolve, platforms like OmniMol and Bayer's in-house ADMET system are demonstrating that these methods are not merely alternatives but are becoming the foundational tools for lead identification and optimization [15] [16]. By integrating the protocols and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can build more efficient and predictive workflows, de-risking the development of natural products and accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics from nature.

The development of natural products into viable therapeutics is frequently hampered by a trio of significant pharmacokinetic challenges: poor aqueous solubility, chemical instability, and extensive first-pass metabolism. These properties often result in low oral bioavailability, undermining the promising biological activities observed in initial screening. Traditionally, identifying these issues relied on late-stage experimental testing, leading to high attrition rates and substantial financial losses when promising candidates failed during development [4]. The pharmaceutical industry has consequently shifted toward early and extensive screening of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties [4].

Within this framework, in silico (computational) methods have emerged as a powerful, cost-effective strategy to overcome these hurdles. These approaches eliminate the need for physical samples in the early stages, require no laboratory infrastructure, and provide rapid insights before synthetic or isolation efforts begin [4]. For natural products, which are often structurally complex, available in limited quantities, and sensitive to environmental factors, the advantages of computational tools are particularly pronounced [4] [19]. This technical guide details how modern in silico methodologies are being deployed to predict, understand, and optimize the solubility, stability, and metabolic fate of natural products, thereby de-risking their development path.

In Silico Strategies for Solubility Prediction

Aqueous solubility is a critical determinant of a compound's bioavailability. Poor solubility can limit absorption and efficacy, making it one of the most common failure points in drug development [20]. Computational prediction of solubility has evolved from traditional empirical parameters to sophisticated machine learning and physics-based models.

Traditional and Physics-Based Modeling Approaches

Traditional methods often operate on the principle of "like dissolves like," using empirically derived parameters to predict miscibility.

- Hildebrand Solubility Parameter (δ): This single-parameter model is derived from the cohesive energy density of a substance. It is most effective for predicting the solubility of non-polar and slightly polar molecules in similarly characterized solvents but fails to account for strong specific interactions like hydrogen bonding [21].

- Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP): An extension of the Hildebrand parameter, HSP partitions the total solubility parameter into three components: dispersion forces (δd), dipolar interactions (δp), and hydrogen bonding (δh). A solute's solubility in a solvent is determined by the proximity of their respective HSP coordinates in this three-dimensional space. HSP is particularly popular in polymer science but can struggle with very small, strongly hydrogen-bonding molecules like water and methanol [21].

- Physics-Based Methods: These approaches leverage fundamental thermodynamics to compute solubility from first principles, requiring no parametrization against experimental solubility data. They involve separately calculating the free energy of the solid crystalline phase (lattice energy) and the solvation free energy of the dissolved molecule. While highly accurate and providing rich thermodynamic data, these methods are computationally intensive and must account for factors such as crystalline polymorphic form [20].

Data-Driven Machine Learning Models

Machine learning (ML) models represent the state-of-the-art in solubility prediction, offering speed and high accuracy across a wide range of chemical spaces.

- Descriptor-Based ML Models: These models use a small set of rationally selected molecular descriptors that capture key physicochemical aspects of the dissolution process. These may include molecular weight, solvation energy, dipole moment, molecular volume, and solvent-accessible surface area. Various ML algorithms, including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), are then trained on these descriptors. This approach has been shown to achieve an accuracy close to the expected level of noise in experimental training data (LogS ± 0.7) [22].

- The

fastsolvModel: A prominent example of a deep-learning model,fastsolvis trained on the large experimental BigSolDB dataset. It can predict not just categorical solubility but the actual log10(Solubility) value across a range of temperatures and for a wide variety of organic solvents. It can also predict non-linear temperature effects and report uncertainty estimates for its predictions, providing crucial information for experimental planning [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Solubility Prediction Methods

| Method | Basis of Prediction | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hildebrand Parameter | Cohesive energy density | Simple, fast calculation | Only suitable for non-polar systems; low accuracy |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) | Dispersion, polarity, hydrogen bonding | Useful for solvent mixtures; widely used for polymers | Struggles with strong H-bonders; requires experimental data for fitting |

| Physics-Based Methods | First-principles thermodynamics | High accuracy; no empirical solubility data needed; provides thermodynamic insights | Computationally very expensive; requires knowledge of crystal structure |

Machine Learning (e.g., fastsolv) |

Statistical learning on large datasets | High accuracy; predicts exact solubility & temperature dependence; fast | Requires large, high-quality training data; "black box" nature can limit interpretability |

Computational Forecasting of Chemical Stability

Chemical instability in natural products can lead to loss of potency, formation of impurities, and limited shelf-life. Stability can be compromised by environmental factors like temperature, pH, and light. In silico tools help predict both intrinsic chemical reactivity and long-term stability under various conditions.

Quantum Mechanics for Reactivity Assessment

Quantum mechanical (QM) calculations can be used to explore the electronic structure of a molecule to evaluate its intrinsic stability and reactivity.

- Application Example: Semiempirical QM methods (e.g., PM3, PM6, MNDO) have been employed to characterize the chemical stability and reactivity of natural compounds. For instance, studies on alternamide-A and uncinatine-A used these methods to conclude that these compounds possess high reactivity and limited stability, flagging them as potential liabilities [4].

- Methodology: The molecular structure is optimized using appropriate levels of theory (e.g., B3LYP/6-311+G*). Analyses of molecular orbitals, such as the energy and shape of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), can reveal sites susceptible to nucleophilic or electrophilic attack, respectively. Calculations of bond dissociation energies can also predict susceptibility to oxidative degradation [4].

Advanced Kinetic Modeling for Shelf-Life Prediction

For forecasting long-term stability under storage conditions, Advanced Kinetic Modeling (AKM) provides a powerful solution that moves beyond simple zero- or first-order models.

- Principle: AKM uses data from short-term accelerated stability studies (e.g., at 5°C, 25°C, and 37°C/40°C) to build phenomenological kinetic models based on the Arrhenius equation. These models can describe complex degradation pathways, including multi-step reactions with an initial rapid drop followed by a slower phase [23].

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: Generate stability data for the critical quality attribute (e.g., potency, purity) at a minimum of three temperatures, ensuring significant degradation (e.g., 20%) is reached at the highest temperature.

- Model Screening: Fit the experimental data to a suite of kinetic models, from simple to complex multi-step models.

- Model Selection: Identify the optimal model using statistical parameters like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

- Prediction and Validation: Use the selected model to simulate degradation under recommended storage conditions (e.g., 2-8°C) over the desired shelf-life (e.g., 24-36 months) and establish prediction intervals. This methodology has been successfully validated for predicting stability up to 3 years for various biotherapeutics and vaccines [23].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Stability Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Example / Reagent | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics Software | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA | Calculates electronic structure, molecular orbitals, and bond energies to predict intrinsic chemical reactivity. |

| Semi-Empirical Methods | MOPAC (with PM6, PM3, MNDO) | Provides faster, approximate QM calculations for initial reactivity screening of large compound sets. |

| Kinetic Modeling Software | AKTS-Thermokinetics Software | Fits accelerated stability data to complex kinetic models and predicts shelf-life under various temperature profiles. |

| Statistical Software | SAS, JMP | Performs statistical analysis and linear regression for traditional ICH-based stability modeling. |

Predicting and Modulating First-Pass Metabolism

First-pass metabolism, primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in the liver and gut and efflux by transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp), can drastically reduce the systemic exposure of an orally administered natural product.

Molecular Docking to Predict Enzyme and Transporter Interactions

Molecular docking is a cornerstone technique for predicting how a small molecule (ligand) will interact with a biological macromolecule (target), such as a CYP enzyme or P-gp.

- Target Preparation: The 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6, P-gp) is obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Water molecules and heteroatoms are removed, and hydrogen atoms are added.

- Ligand Preparation: The 3D structure of the natural product is drawn or imported, and its geometry is optimized and energy-minimized.

- Docking Simulation: Software like AutoDock Vina is used to simulate the binding of the ligand into the target's active site. The algorithm searches for the optimal binding conformation and scores it based on a scoring function, which estimates the binding affinity (often reported in kcal/mol) [24] [25].

- Interpretation: A more negative binding energy suggests stronger binding. If a natural product shows a strong binding affinity to a major CYP enzyme's active site, it can be predicted as a substrate for metabolism. Conversely, strong binding without being metabolized might suggest inhibitory potential.

Modeling Metabolism with Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics

For a deeper understanding of the metabolic process itself, hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) simulations can be employed.

- Application: This method is used to study the detailed molecular mechanism of enzymatic reactions. For example, QM/MM simulations on the bacterial P450cam enzyme have been used to explore the controversial mechanisms of camphor hydroxylation, providing atom-level insight into the reactivity of the enzyme's catalytic center [4].

- Methodology: In a QM/MM setup, the enzyme's active site (including the heme and bound substrate) is treated with high-accuracy QM, while the surrounding protein environment is handled with faster, classical MM. This allows researchers to simulate the electronic rearrangements involved in the breaking and forming of bonds during metabolism [4].

Integrated ADME and Target Prediction Platforms

Web servers and software suites provide integrated platforms for efficiently screening natural products.

- SwissADME: This freely available tool allows for the rapid prediction of key pharmacokinetic properties, including gastrointestinal absorption, blood-brain barrier penetration, and interactions with CYP enzymes. It provides a simple interface for inputting chemical structures and returns easy-to-interpret reports [24].

- SwissTargetPrediction: This tool predicts the most likely protein targets of a small molecule based on its 2D and 3D similarity to known ligands. This can help identify off-target interactions, including unintended binding to metabolic enzymes or transporters [24].

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Reagents for Validation

Bridging in silico predictions with experimental validation is crucial for building confidence in computational models. The following workflow and toolkit outline this integrated approach.

A Unified In Silico Protocol

A comprehensive in silico assessment of a natural product can be conducted as follows, integrating the methods described above:

- Input: Obtain or draw the 2D/3D structure of the natural product.

- Solubility Screening: Run the structure through a machine learning predictor like

fastsolvto estimate aqueous solubility (LogS) and its temperature dependence. - Stability Triage: Perform a QM calculation to identify potentially unstable functional groups (e.g., hydrolyzable esters, oxidizable catechols).

- Metabolism and Transport Prediction:

- Use molecular docking against major CYP isoforms (3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 2C19) and P-gp.

- Use SwissADME to get a rapid profile of CYP inhibition and passive absorption.

- Data Integration and Decision: Synthesize all predictions to profile the compound. A candidate with poor predicted solubility, high reactivity, and high affinity for CYP3A4 would be flagged for structural modification or deprioritized.

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Table 3: Essential Experimental Tools for Validating In Silico Predictions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An in vitro model of human intestinal permeability used to assess absorption and P-gp mediated efflux. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | A subcellular fraction containing CYP enzymes, used to measure metabolic stability and identify metabolites. |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Individual CYP isoforms used to determine which specific enzyme is responsible for metabolizing a compound. |

| P-glycoprotein Assay Kits | Cell-based or membrane-based kits (e.g., from Solvo Biotechnology) to definitively determine P-gp substrate or inhibitor status. |

| Forced Degradation Studies | Exposure of the compound to stress conditions (acid, base, oxidants, light, heat) to validate predicted instability and identify degradation products. |

| Stability Chambers | Controlled environmental chambers to conduct accelerated stability studies for validating AKM shelf-life predictions. |

The integration of in silico methods into the natural product development pipeline represents a paradigm shift. By proactively addressing the critical hurdles of solubility, stability, and first-pass metabolism, computational tools empower researchers to make data-driven decisions earlier in the process, saving time and resources. The ability to screen virtual libraries of natural products or to rationally modify lead compounds based on predicted structure-property relationships significantly de-risks the path from bioactivity hit to viable drug candidate. As these computational models continue to improve in accuracy and scope, fueled by larger datasets and more powerful algorithms like AI, their role in unlocking the full therapeutic potential of natural products will only become more central. The future of natural product drug discovery lies in the strategic synergy between predictive in silico models and targeted experimental validation.

The Shift to Early-Stage Screening in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

The traditional drug discovery pipeline is a notoriously long and costly endeavor, taking an average of 12–15 years and costing in excess of $1 billion to bring a new drug to market [26]. A significant contributor to this high cost and lengthy timeline is the late-stage attrition of drug candidates, often due to unforeseen adverse effects or suboptimal pharmacokinetic profiles. Historically, promising compounds failed in clinical development for two main reasons: they were either ineffective or unsafe [26]. In response, the pharmaceutical industry has undergone a strategic pivot, moving critical safety and pharmacokinetic assessments earlier in the discovery process. This paradigm shift aims to identify and eliminate problematic compounds before substantial resources are invested in their development.

This shift is particularly pertinent for research involving natural products. Natural compounds often possess unique chemical structures with promising biological activities, but they also present distinct challenges, including complex chemical instability, low aqueous solubility, and limited availability from natural sources [4]. Furthermore, they may be degraded by stomach acid or undergo extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver before reaching their target [4]. Early-stage screening provides a framework to evaluate these properties at the outset, de-risking the development of natural products. The integration of in silico (computational) tools has been a cornerstone of this transformation, offering a rapid, cost-effective, and animal-free method to profile compounds based solely on their structural information, thus perfectly aligning with the needs of modern natural products research [4] [11].

The Core Components of Early-Stage Screening

Early-stage screening is a multi-faceted strategy that integrates computational and advanced in vitro and in vivo models to build a comprehensive profile of a candidate compound as quickly as possible.

1In SilicoADMET Profiling

In silico methods leverage computational power to predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of molecules, eliminating the need for a physical sample [4].

Key Methods and Tools: A range of computational approaches is employed for ADMET prediction.

- Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) is used to explore enzyme-inhibitor interactions and predict metabolic pathways, such as those involving the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme family responsible for metabolizing most drugs [4].

- Molecular Docking and Pharmacophore Modeling help identify potential biological targets and understand how a compound might interact with proteins, a process known as "target fishing" [27] [11].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Analysis and machine learning models are used to predict toxicity and physicochemical properties based on the compound's structural features [4] [11].

- Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling provides a more holistic, system-wide simulation of a drug's journey through the body [4].

- Popular software tools and web servers like SwissADME and admetSAR are routinely used to compute key parameters such as gastrointestinal absorption, blood-brain barrier permeability, and drug-likeness [27] [28].

Application to Natural Products: In silico profiling is exceptionally valuable for natural products research. For example, a study on phytochemicals from Ethiopian indigenous aloes used these tools to evaluate drug-likeness, predict human targets, and elucidate associated biological pathways, demonstrating the polypharmacology of these compounds [27]. Similarly, an ADMET analysis of 308 phytochemicals from the genus Dracaena identified 12 compounds with favorable profiles, prioritizing them for further investigation [28].

Table 1: Key ADMET Properties and Their Ideal Ranges for Natural Compounds

| Property | Description | Ideal Range for Drug-Likeness |

|---|---|---|

| Lipinski's Rule of Five | Predicts oral bioavailability based on molecular weight, Log P, H-bond donors/acceptors | ≤ 2 violations is common for natural products [27] |

| Veber's Rules | Assesses oral bioavailability based on polar surface area and rotatable bonds | TPSA ≤ 140 Ų, ≤ 10 rotatable bonds [27] |

| Water Solubility (Log S) | Aqueous solubility | Ideally > -4 log mol/L [27] |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) Absorption | Likelihood of oral absorption | High [27] [28] |

| BBB Permeability | Ability to cross the blood-brain barrier | Dependent on therapeutic intent (CNS vs. peripheral) [27] |

| CYP Inhibition | Potential for drug-drug interactions | Non-inhibitor of key enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, 2D6) [4] |

| hERG Inhibition | Indicator of cardiotoxicity risk | Non-inhibitor [28] [29] |

AdvancedIn Vitroand Cellular Models

While in silico tools provide an excellent starting point, experimental validation in biologically relevant systems is crucial. Technological advances have led to more predictive in vitro models.

- Primary Human Hepatocytes: The liver is the primary site of drug metabolism. The use of primary human hepatocytes in formats like the sandwich culture or as 3D spheroids provides a more physiologically relevant model for assessing metabolic stability, drug-drug interactions, and mechanisms of toxicity than traditional cell lines. These advanced cultures can maintain metabolic function for more than 14 days, allowing for the detection of metabolites from slowly metabolized drugs [30].

- Organoid Technology: Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) are 3D cell cultures that closely mimic the genetic and morphological characteristics of their tissue of origin. They are superior to traditional 2D cell lines for drug screening because they maintain a high degree of similarity to the original tissue, including gene expression and drug response. They can be scaled for high-throughput screening, with assays demonstrating high robustness (Z-factors ~0.7) and reproducibility [31].

- Cellular Target Engagement Assays: Technologies like the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) provide direct, quantitative evidence of intracellular target engagement in intact, living cells. This confirms that a compound not only is active in a simplified biochemical assay but actually binds to its intended target in a physiological environment, helping to triage false positives early [32].

IntegrativeIn VivoModels

Bridging the gap between in vitro assays and mammalian testing, certain in vivo models offer a balance of physiological relevance and scalability.

- Zebrafish Models: Zebrafish have become a powerful platform for the hit-to-lead (H2L) optimization phase. Their small size, rapid development, and genetic similarity to humans make them ideal for early in vivo toxicity and efficacy screening. They serve as a cost-effective filter, reducing the number of compounds that need to be tested in more expensive rodent models, potentially saving 10 months and reducing costs by 60% in some cases [33]. Real-world successes include the identification of Clemizol for Dravet syndrome, which advanced to phase II clinical trials based on zebrafish screening [33].

Experimental Protocols for Key Screening Methodologies

Protocol:In SilicoADMET and Drug-Likeness Profiling

This protocol outlines the steps for computationally profiling a natural compound.

- Compound Structure Preparation: Obtain or draw the 2D chemical structure of the natural compound. Convert it into a standardized format like SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line-Entry System) or SDF.

- Physicochemical Property Calculation: Input the structure into a tool like the SwissADME webserver. Calculate key descriptors:

- Drug-Likeness Evaluation: Apply established rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's Rules to assess the compound's potential for oral bioavailability. Note that natural products often have 2-3 violations but may still be successful drugs [27].

- ADMET Prediction: Use servers like admetSAR or SwissADME to predict:

- Absorption: Gastrointestinal absorption (high/low)

- Distribution: Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) permeability (yes/no)

- Metabolism: Inhibition of major Cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, 2D6)

- Excretion: Substrate status for P-glycoprotein (P-gp)

- Toxicity: AMES mutagenicity, hERG inhibition, and hepatotoxicity [27] [28]

- Data Integration and Prioritization: Compile results. Prioritize compounds that show a favorable balance of potency (from separate assays) and drug-like ADMET properties for further experimental validation.

Protocol: Off-Target Pharmacological Profiling

This protocol describes the use of a focused assay panel to identify unintended compound activities.

- Panel Selection: Select a pre-configured panel of 50-70 pharmacologically relevant targets (e.g., GPCRs, ion channels, kinases) known to be associated with adverse effects. This panel can be optimized to maximize diversity and minimize redundancy [29].

- Screening: Test the compound at a single concentration (typically 10 µM) in radioligand binding or enzyme activity assays for each target in the panel.

- Hit Identification: Identify an assay "hit" as a compound demonstrating significant inhibition or binding (e.g., ≥50% inhibition at 10 µM, or an IC50 ≤ 1 µM) [29].

- Data Analysis: Calculate a "panel hit score" (the number of targets hit). A high score indicates promiscuity, which is often correlated with poor in vivo tolerability. This score can be used to select safer compounds for animal studies [29].

Diagram 1: Integrated early-stage screening workflow for natural products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Platforms for Early-Stage Screening

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Screening | Application in Natural Product Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Hepatocytes | Models human drug metabolism and clearance. | Predicts metabolic stability and identifies metabolites of natural compounds [30]. |

| 3D Spheroid & Organoid Cultures | Provides physiologically relevant tissue architecture for efficacy/toxicity testing. | Used in high-throughput panels (e.g., OrganoidXplore) to test natural compounds across many cancer types [31]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Measures direct target engagement of compounds in intact cells. | Validates hypothesized mechanism of action for natural products in a native cellular environment [32]. |

| Zebrafish Embryos/Larvae | Whole-organism in vivo model for phenotypic and toxicity screening. | Allows rapid assessment of natural product effects on complex biological processes (e.g., neuropharmacology, cardiotoxicity) [33]. |

| SwissADME / admetSAR | In silico platforms for predicting pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties. | First-pass evaluation of natural product drug-likeness and ADMET properties before any wet-lab experimentation [27] [28]. |

| Optimized Off-Target Panel | A curated set of binding assays to identify promiscuous compounds. | Flags natural products with potential for mechanism-based side effects early in development [29]. |

The strategic shift to early-stage screening represents a fundamental evolution in drug discovery, prioritizing the rapid collection of critical pharmacokinetic and safety data to de-risk the development pipeline. For the field of natural products research, this paradigm is transformative. By leveraging a synergistic combination of in silico predictions, physiologically relevant in vitro models, and efficient in vivo systems, researchers can confidently navigate the unique challenges posed by natural compounds. This integrated approach enables the identification of high-quality lead candidates with a greater probability of clinical success, unlocking the immense therapeutic potential of nature's chemical diversity in a more efficient and cost-effective manner.

A Practical Toolkit: Key In Silico Methods and Their Application to Natural Compounds

Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Predictive ADMET Profiling

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties remains a critical bottleneck in drug discovery, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates [6]. Traditional experimental approaches are often time-consuming, cost-intensive, and limited in scalability [4]. The pharmaceutical industry has significantly changed its strategy in recent decades, performing extensive ADMET screening earlier in the drug discovery process to identify and eliminate problematic compounds before they enter costly development phases [4]. For natural products, which are characterized by greater structural diversity and complexity than synthetic molecules, these challenges are even more pronounced [4] [3]. Fortunately, recent advances in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have revolutionized ADMET prediction by enhancing accuracy, reducing experimental burden, and accelerating decision-making during early-stage drug development [6] [34]. This transformation is particularly valuable for natural product research, where ML tools accelerate discovery in oncology, infection, inflammation, and neuroprotection by enabling activity prediction, mechanism inference, and compound prioritization [35].

Fundamentals of Machine Learning in ADMET Prediction

Core Concepts and Workflow

Machine learning refers to a method of data analysis involving the development of new algorithms and models capable of interpreting a multitude of data [6]. In the context of ADMET prediction, ML techniques leverage large-scale compound databases to enable high-throughput predictions with improved efficiency [34]. The standard methodology begins with obtaining a suitable dataset, often from publicly available repositories tailored for drug discovery. The quality of this data is crucial, as it directly impacts model performance [6].

The development of a robust ML model follows a systematic workflow that includes multiple critical stages, as visualized below.

Machine Learning Algorithms for ADMET

ML methods are generally divided into supervised and unsupervised approaches [6]. In supervised learning, models are trained using labeled data to make predictions, such as predicting pharmacokinetic properties based on input attributes like chemical descriptors of new compounds. Unsupervised learning aims to find patterns, structures, or relationships within a dataset without using labeled or predefined outputs [6].

Table 1: Common Machine Learning Algorithms Used in ADMET Prediction

| Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | Key Applications in ADMET | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Based Methods | Random Forests, Decision Trees, LightGBM, CatBoost [6] [36] | Classification and regression tasks for solubility, permeability, toxicity [36] | Handles non-linear relationships, robust to outliers |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks, Message Passing Neural Networks, Deep Neural Networks [35] [34] [36] | Complex endpoint prediction, molecular property learning [34] | Automates feature extraction, models intricate patterns |

| Support Vector Machines | SVM with various kernels [6] [36] | Binary classification tasks | Effective in high-dimensional spaces |

| Ensemble Methods | Gradient Boosting Frameworks [6] [36] | Improving prediction accuracy across multiple endpoints | Combines multiple weak learners for better performance |

Key Methodologies and Molecular Representations

Molecular Descriptors and Feature Engineering

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that convey the structural and physicochemical attributes of compounds based on their 1D, 2D, or 3D structures [6]. These descriptors form the foundation upon which ML models are built. Feature engineering plays a crucial role in improving ADMET prediction accuracy [6]. Traditional approaches rely on fixed fingerprint representations, but recent advancements involve learning task-specific features by representing molecules as graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [6].

Several feature selection methods are employed to determine relevant properties for specific classification or regression tasks [6]:

- Filter Methods: Applied during pre-processing to select features without relying on any specific ML algorithm, efficiently eliminating duplicated, correlated, and redundant features.

- Wrapper Methods: Iteratively train the algorithm using subsets of features, dynamically adding and removing features based on insights gained during previous model training iterations.

- Embedded Methods: Integrate the feature selection algorithm into the learning algorithm, combining the strengths of filter and wrapper techniques while mitigating their respective drawbacks.

Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as particularly powerful tools for ADMET prediction because they naturally operate on molecular graph structures, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [34]. These approaches have achieved unprecedented accuracy in ADMET property prediction by explicitly modeling the topological structure of molecules [6]. Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs), as implemented in tools like Chemprop, have shown strong performance across multiple ADMET benchmarks [36].

Multitask learning frameworks represent another significant advancement, where models are trained simultaneously on multiple related ADMET endpoints [34]. This approach leverages shared information across tasks, often leading to improved generalization and reduced overfitting, especially when data for individual endpoints may be limited.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Collection and Preprocessing

The first critical step in developing ML models for ADMET prediction involves data collection from publicly available or proprietary databases. Key data sources include:

- Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC): Provides curated benchmarks for ADMET-associated properties [36]

- ChEMBL: A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [6]

- PubChem: Provides access to chemical property data, including kinetic solubility measurements [36]

Data cleaning is essential to ensure model reliability and involves several standardized steps [36]:

- Remove inorganic salts and organometallic compounds from datasets

- Extract organic parent compounds from their salt forms

- Adjust tautomers to have consistent functional group representation

- Canonicalize SMILES strings to ensure consistent molecular representation

- De-duplicate entries, keeping the first entry if target values are consistent, or removing the entire group if inconsistent

Model Training and Validation Protocol

A robust methodology for model development includes the following steps [6] [36]:

Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into training, validation, and test sets using scaffold-based splitting to ensure that structurally similar molecules are grouped together, providing a more challenging and realistic evaluation scenario.

Feature Representation: Select appropriate molecular representations, which may include:

- Molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit descriptors)

- Fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints)

- Learned representations (e.g., graph embeddings)

Model Selection and Training: Choose appropriate algorithms based on dataset size and complexity, then train multiple models using the training set.

Hyperparameter Optimization: Tune model-specific parameters using the validation set through methods like grid search or Bayesian optimization.

Model Evaluation: Assess performance on the held-out test set using appropriate metrics:

- For classification tasks: AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall

- For regression tasks: RMSE, MAE, R²

Statistical Validation: Employ cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing to compare model performance robustly [36].

Special Considerations for Natural Products

When applying these methods to natural products, several additional factors must be considered [35] [4]:

- Data Imbalance: Natural product datasets are often small and imbalanced, requiring techniques like data augmentation or specialized sampling approaches

- Structural Complexity: Natural compounds tend to be larger, contain more chiral centers, and have greater structural diversity than synthetic molecules

- Provenance and Variability: Issues of mixture and batch variability, incomplete provenance, and domain shift must be addressed through appropriate model regularization and validation strategies

Applications in Natural Product Research

Case Studies and Validation

ML-driven ADMET prediction has demonstrated significant success in natural product research. In oncology, infection, inflammation, and neuroprotection, AI tools have accelerated natural product discovery by enabling activity prediction, mechanism inference, and prioritization [35]. These approaches include tree ensembles, graph neural networks, and self-supervised molecular embeddings for mixtures, isolated metabolites, and peptide analogs [35].

Network pharmacology models have been particularly valuable for natural products, creating herb-ingredient-target-pathway graphs to propose synergistic effects [35]. For example, in a study examining phytoconstituents from Tulipa gesneriana L., SwissADME computational tools were used to evaluate the ADME properties of 31 phytocompounds [9]. The analysis identified quercetin as a promising candidate due to its favorable bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profile, while coumarin demonstrated potential for blood-brain barrier penetration [9].

Another study aimed at identifying natural analgesic compounds through molecular docking-virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulation, and ADMET computations found that three compounds—apigenin, kaempferol, and quercetin—demonstrated the highest affinity for the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) receptor [37]. Pharmacokinetic and toxicity assessments indicated favorable oral bioavailability and an overall acceptable safety profile for these compounds [37].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of ML Models on ADMET Prediction Tasks

| ADMET Endpoint | Best Performing Algorithm | Key Molecular Representation | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | Random Forest | RDKit Descriptors + FCFP4 | Accuracy: >80% [6] |

| Bioavailability | Logistic Algorithm | 47 selected molecular descriptors | Predictive Accuracy: >71% [6] |

| Solubility | Message Passing Neural Networks | Morgan Fingerprints | RMSE: <0.8 log units [36] |

| PPBR (Plasma Protein Binding) | Gradient Boosting | Combined Descriptors + Fingerprints | R²: >0.7 [36] |

| hERG Toxicity | Graph Neural Networks | Molecular Graph Representation | AUC-ROC: >0.85 [34] |

Implementing ML approaches for ADMET prediction requires a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key platforms and their applications in natural product research.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ML-based ADMET Prediction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Functionality | Application in Natural Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissADME [9] | Web Tool | Predicts pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, medicinal chemistry properties | Free accessibility for screening phytochemicals |

| Schrödinger Suite [14] | Commercial Software | Molecular docking, dynamics simulations, ADMET predictions | Structure-based drug design for natural compounds |

| RDKit [36] | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Feature generation for natural product datasets |

| Chemprop [36] | Deep Learning Framework | Message Passing Neural Networks for molecular property prediction | Modeling complex natural product structures |

| ZINC Database [14] | Compound Library | Natural product structures for virtual screening | Source of natural compounds for screening campaigns |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [36] | Benchmarking Platform | Curated ADMET datasets and model evaluation | Benchmarking natural product ADMET prediction |

Integrated Workflow for Natural Product ADMET Profiling

The application of ML for ADMET prediction in natural products research follows a comprehensive workflow that integrates multiple computational approaches, from initial screening to advanced validation, as depicted below.

This integrated approach leverages the strengths of multiple computational methods: machine learning models for rapid ADMET profiling, molecular docking for binding mode analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations for assessing complex stability over time. For natural products, this workflow is particularly valuable as it helps prioritize the most promising candidates from large phytochemical libraries before committing to resource-intensive experimental validation [37] [14].

Machine learning and deep learning have emerged as transformative technologies in ADMET prediction, offering new opportunities for early risk assessment and compound prioritization in natural product research [6]. These approaches provide rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives that integrate seamlessly with existing drug discovery pipelines [6]. While challenges such as data quality, algorithm transparency, and regulatory acceptance persist, continued integration of ML with experimental pharmacology holds the potential to substantially improve drug development efficiency and reduce late-stage failures [6] [34]. For natural products specifically, these computational methods help address unique challenges including structural complexity, data scarcity, and mixture variability [35]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents from natural sources while providing deeper insights into their mechanisms of action and pharmacokinetic profiles.

Molecular Docking and Dynamics for Mechanistic Insights

Molecular docking and dynamics simulations have emerged as indispensable tools in modern computational drug discovery, providing unprecedented insights into molecular interactions at an atomic level. These techniques are particularly transformative for researching natural products, where the complex chemical space presents both extraordinary opportunities and significant challenges. When framed within the context of in silico Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction, these computational approaches offer a powerful strategy for de-risking natural product development by identifying promising candidates with favorable pharmacological profiles early in the discovery pipeline [38] [39].

The integration of molecular docking and dynamics addresses a critical bottleneck in natural product research. While natural products have a long history of use in treating various diseases, particularly in developing countries, traditional discovery efforts have mostly involved the use of crude extracts in in-vitro and/or in-vivo assays with limited efforts at isolating active principles for structure elucidation studies [38]. Molecular docking serves as a computational technique that predicts the binding affinity and orientation of ligands (such as natural compounds) to receptor proteins, enabling researchers to study the behavior of small molecules within the binding site of a target protein and understand the fundamental biochemical processes underlying these interactions [39]. This approach is structure-based and requires a high-resolution three-dimensional representation of the target protein, typically obtained through techniques like X-ray crystallography, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, or Cryo-Electron Microscopy [39].

The combination of these computational methods with ADMET prediction creates a powerful framework for prioritizing which natural products to investigate experimentally, potentially saving substantial time and resources [38] [34]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of molecular docking and dynamics methodologies, with special emphasis on their application to natural products research and integration with ADMET profiling to facilitate more efficient and targeted drug discovery efforts.

Technical Foundations of Molecular Docking

Fundamental Principles and Algorithms

Molecular docking aims to predict the optimal binding orientation and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) within a protein's binding site to form a stable complex [39]. The process involves two fundamental steps: sampling plausible ligand conformations within the protein's active site and ranking these conformations using scoring functions to identify the most likely binding mode [39]. The sampling algorithms systematically explore the rotational, translational, and conformational degrees of freedom of the ligand relative to the protein target.

Search algorithms in molecular docking are broadly classified into systematic methods, stochastic approaches, and deterministic techniques. Systematic or direct methods include:

- Conformational search: Gradually changes torsional (dihedral), translational, and rotational degrees of freedom of the ligand's structural parameters [39].

- Fragmentation: Docks multiple fragments either by forming bonds between them or building outward from an initially docked fragment using tools like FlexX, DOCK, and LUDI [39].

- Database search: Generates numerous reasonable conformations of small molecules already recorded in databases and docks them as rigid bodies using tools like FLOG [39].

Stochastic methods incorporate randomness in the search process and include:

- Monte Carlo algorithms: Randomly place ligands in the receptor binding site, score them, and generate new configurations using tools like MCDOCK and ICM [39].

- Genetic algorithms: Begin with a population of poses where each "gene" describes the configuration and location relative to the receptor, with the score representing "fitness." Subsequent generations are created through transformations and hybrids of the fittest individuals, implemented in programs like GOLD and AutoDock [39].

- Tabu search: Operates by implementing constraints that prevent re-examination of previously explored areas of the ligands' conformational space using tools like PRO LEADS and Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) [39].

Scoring Functions for Binding Affinity Prediction

Scoring functions are mathematical procedures used to predict the binding affinity of protein-ligand complexes generated by docking simulations. These functions are typically classified into four main categories:

- Force field-based: Calculate binding affinity by summing contributions from non-bonded interactions including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and Coulombic electrostatics, along with bond angle and torsional deviation terms. Tools implementing this approach include AutoDock, DOCK, and GoldScore [39].

- Empirical functions: Utilize multiple linear regression analysis on trained sets of protein-ligand complexes with known binding affinities, parameterizing functional groups and specific interaction types like hydrogen bonds and aromatic ring stacking. Examples include LUDI score, ChemScore, and AutoDock scoring [39].

- Knowledge-based: Statistically assess collections of complex structures to derive potentials of mean force for atom pairs or functional groups, implemented in tools like PMF and DrugScore [39].

- Consensus scoring: Combine evaluations or classifications obtained through multiple scoring methods in various arrangements to improve prediction reliability [39].

Table 1: Major Categories of Scoring Functions in Molecular Docking

| Type | Basis of Function | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field-based | Molecular mechanics principles; sums non-bonded interaction energies | Strong theoretical foundation; physically meaningful parameters | Doesn't explicitly account for solvation/entropy; computationally intensive | AutoDock, DOCK, GoldScore |

| Empirical | Linear regression of known binding energies using interaction terms | Fast calculation; good correlation with experimental data | Parameterized for specific systems; limited transferability | LUDI, ChemScore, AutoDock scoring |

| Knowledge-based | Statistical potentials derived from structural databases | Implicitly accounts for complex effects; no parameter fitting | Dependent on database quality and size; less interpretable | PMF, DrugScore |

| Consensus | Combination of multiple scoring functions | Improved reliability and robustness; reduced method bias | Computationally expensive; implementation complexity | Multiple implementations |

Molecular Dynamics for Binding Stability Assessment

Principles and Methodologies

While molecular docking provides static snapshots of protein-ligand interactions, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer a dynamic perspective by simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, typically following Newton's laws of motion. This approach is crucial for understanding the stability and evolution of binding interactions under more physiologically realistic conditions [40]. MD simulations can capture conformational changes, ligand dissociation pathways, and binding mode stability that are inaccessible through static docking approaches.

A typical MD simulation protocol involves several key steps. First, the system is prepared by placing the docked protein-ligand complex in a solvation box filled with water molecules, followed by system neutralization through the addition of ions and setting ionic strength to physiological levels (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [40]. The simulation then proceeds through a careful equilibration protocol before production runs:

- Initial stage: 100 ps Brownian dynamics NVT simulation at 10 K with constraints on protein's heavy atoms [40]

- Second stage: 12 ps NVT simulation at 10 K with restrictions on solute heavy atoms [40]

- Third stage: 12 ps NPT simulation at 10 K, retaining restrictions on solute heavy atoms [40]

- Final relaxation stage: Increasing temperature from 10 K to 300 K in 12 ps of NPT ensemble [40]

- Production simulation: Continued for the desired duration (e.g., 100 ns) in NPT ensemble at 300 K with no restraints [40]

The OPLS_2005 force field parameters are commonly used in such simulations, providing accurate parameterization for proteins and small molecules [40].

Analysis Methods for MD Trajectories

Following MD simulations, trajectories are analyzed using various parameters to assess system stability and interaction patterns. Key analysis methods include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability by calculating the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures, with lower values indicating more stable complexes [40].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Assesses flexibility of specific protein regions during simulation, helping identify dynamic binding site residues [40].

- Binding free energy calculations: Methods like MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area) combine molecular mechanics calculations with implicit solvation models to estimate binding affinities from simulation trajectories [40].

- Hydrogen bond analysis: Tracks formation and persistence of specific hydrogen bonds between ligand and protein throughout the simulation.

- Interaction fingerprints: Characterize and visualize specific molecular interactions (hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking, salt bridges) over time.