Transforming Drug Discovery: The Critical Role and Future of AI-Driven ADMET Prediction

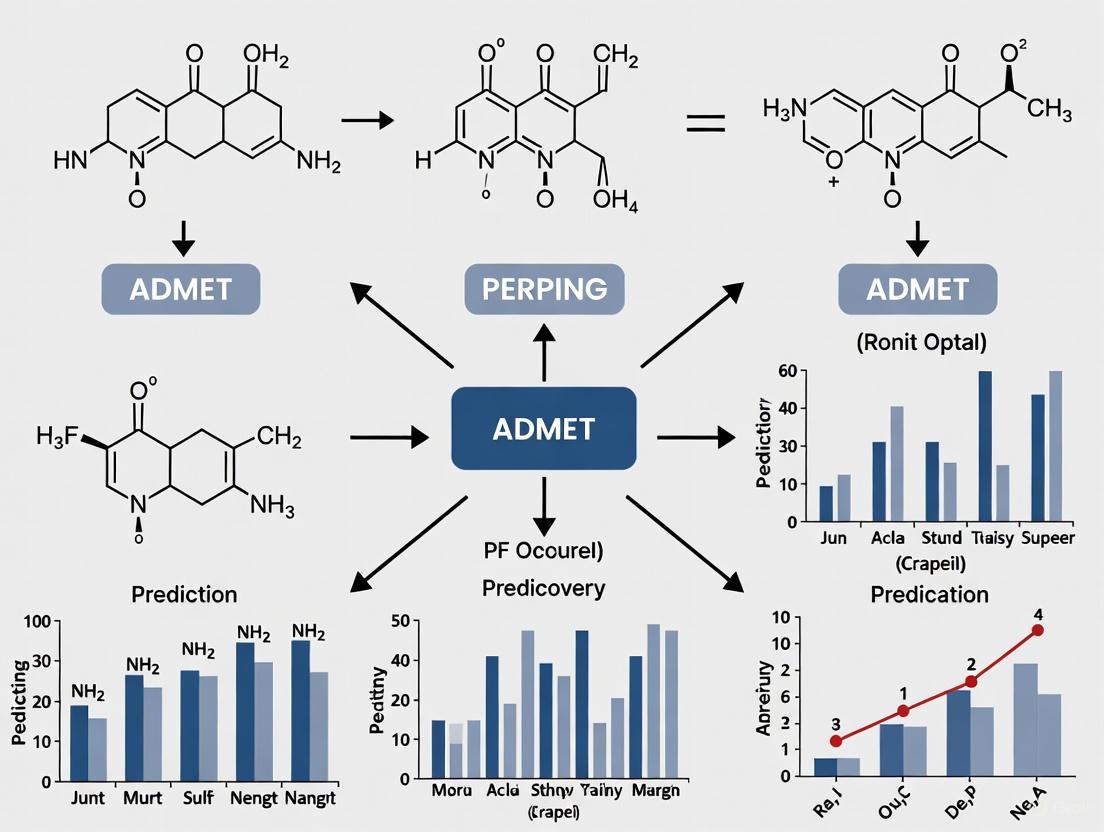

This article explores the transformative role of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction in accelerating early-stage drug discovery.

Transforming Drug Discovery: The Critical Role and Future of AI-Driven ADMET Prediction

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction in accelerating early-stage drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of how artificial intelligence and machine learning are overcoming traditional bottlenecks. The scope covers foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, strategies for troubleshooting model limitations, and rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating predictive ADMET profiling into lead optimization, scientists can now efficiently prioritize compounds with favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles, substantially reducing late-stage attrition rates and development costs.

Why ADMET Prediction is a Game-Changer in Early Drug Discovery

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties constitute a critical determinant of clinical success for drug candidates. Despite significant technological advancements in pharmaceutical research, undesirable ADMET profiles remain a primary cause of failure throughout the drug development pipeline. This whitepaper examines the quantitative impact of ADMET-related attrition, explores the underlying physicochemical and biological mechanisms, and presents advanced computational and experimental methodologies that are being integrated into early discovery phases to mitigate these risks. By framing ADMET assessment as a front-loaded activity rather than a downstream checkpoint, research organizations can significantly improve compound prioritization, reduce late-stage failures, and enhance the overall efficiency of drug development.

The Staggering Economic and Temporal Cost of Drug Development

The pharmaceutical industry faces a profound productivity challenge characterized by escalating costs and unsustainable failure rates. Comprehensive analysis reveals that bringing a single new drug to market requires an average investment of $2.6 billion over a timeline spanning 10 to 15 years [1]. This resource-intensive process culminates in a clinical trial success rate of approximately 10%, meaning 90% of drug candidates that enter human testing ultimately fail [1].

This phenomenon is paradoxically described by Eroom's Law (Moore's Law spelled backward), which observes that the number of new drugs approved per billion US dollars spent on R&D has halved roughly every nine years since 1950 [1]. This inverse relationship between investment and output underscores a fundamental efficiency problem within conventional drug development paradigms.

Table 1: Phase-by-Phase Attrition Rates in Clinical Development

| Development Phase | Primary Focus | Failure Rate | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Safety and dosage in healthy volunteers | ~37% | Unexpected human toxicity, undesirable pharmacokinetics [1] |

| Phase II | Efficacy in patient populations | ~70% | Insufficient therapeutic efficacy, safety concerns [1] |

| Phase III | Large-scale efficacy confirmation | ~42% | Inability to demonstrate superiority over existing treatments, subtle safety issues [1] |

The Central Role of ADMET Properties in Drug Attrition

Undesirable ADMET properties represent a dominant cause of the high failure rates documented in Table 1. Research indicates that approximately 30% of overall drug candidate attrition is directly attributable to a lack of safety, much of which stems from unpredictable toxicity [2]. Furthermore, unfavorable pharmacokinetic profiles (encompassing absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) contribute significantly to the remaining failures, particularly in early development phases.

The critical importance of ADMET properties stems from their fundamental influence on whether a molecule that demonstrates potent target engagement in vitro can become a safe and effective medicine in humans. A compound must navigate complex biological barriers, avoid accumulation in sensitive tissues, and be eliminated without producing toxic metabolites—all while maintaining sufficient concentration at the site of action for the required duration.

Physicochemical Drivers of ADMET Failure

The relationship between a molecule's intrinsic physicochemical properties and its ADMET behavior is well-established. Key properties include size, lipophilicity, ionization, hydrogen bonding capacity, polarity, aromaticity, and molecular shape [3]. Among these, lipophilicity stands as arguably the most influential physical property for oral drugs, directly affecting solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and promiscuity (lack of selectivity) [3].

The Rule of 5 (Ro5), developed by Lipinski and colleagues, provided an early warning system for compounds likely to exhibit poor absorption or permeability. The Ro5 states that poor absorption is more likely when a compound violates two or more of the following criteria:

- Molecular weight > 500

- Calculated Log P (cLogP) > 5

- Hydrogen bond donors > 5

- Hydrogen bond acceptors > 10 [3]

While the Ro5 raised awareness of compound quality, it represents a minimal filter rather than an optimization goal. More sophisticated approaches like Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency (LLE), which combines potency and lipophilicity (LLE = pIC50 - cLogP), help identify improved leads even for challenging targets [3]. Additionally, the Property Forecast Index (PFI), calculated as LogD + number of aromatic rings, has emerged as a composite measure where increasing values adversely impact solubility, CYP inhibition, plasma protein binding, permeability, hERG inhibition, and promiscuity [3].

Machine Learning and Computational Approaches for Early ADMET Prediction

The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) into ADMET prediction represents a paradigm shift in early drug discovery. ML models have demonstrated significant promise in predicting key ADMET endpoints, in some cases outperforming traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [4] [5]. These approaches provide rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives that seamlessly integrate with existing drug discovery pipelines [4].

Foundational ML Methodologies and Workflows

The development of robust ML models for ADMET prediction follows a systematic workflow:

- Data Collection and Curation: Models are trained on large-scale experimental data from public repositories like ChEMBL, DrugBank, and specialized ADMET databases [4] [6].

- Data Preprocessing: This critical step involves cleaning, normalization, and feature selection to improve data quality and reduce irrelevant information [4].

- Feature Engineering: Molecular descriptors and representations are crucial. Traditional fixed-length fingerprints are now complemented by graph-based representations where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges, enabling graph convolutional networks to achieve unprecedented accuracy [4].

- Model Training and Validation: Using algorithms ranging from random forests to deep neural networks, with emphasis on cross-validation and independent testing to ensure generalizability [4] [6].

Benchmarking and Practical Implementation

Recent benchmarking studies provide critical insights into optimal ML strategies for ADMET prediction. Research indicates that the optimal combination of algorithms and feature representations is highly dataset-dependent [6]. However, some general patterns have emerged:

- Feature Representation: The systematic combination of different molecular representations (e.g., descriptors, fingerprints, embeddings) often outperforms single representations, but requires structured feature selection rather than simple concatenation [6].

- Model Evaluation: Integrating cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing provides more robust model comparison than single hold-out test sets [6].

- Practical Performance: Models trained on one data source frequently experience performance degradation when evaluated on data from a different source, highlighting the importance of data quality and consistency [6].

Table 2: Key Software and Platforms for ADMET Prediction

| Tool/Platform | Key Features | Endpoints Covered | Underlying Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| admetSAR3.0 [7] | Search, prediction, and optimization modules | 119 endpoints including environmental and cosmetic risk | Multi-task graph neural network (CLMGraph) |

| ADMETlab 2.0 [4] | Integrated online platform | Comprehensive ADMET properties | Multiple machine learning algorithms |

| ProTox-II [2] | Toxicity prediction | Organ toxicity, toxicity endpoints, pathways | Machine learning and molecular similarity |

| SwissADME [7] | Pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion | Rule-based and predictive models |

Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

While in silico methods provide valuable early screening, experimental validation remains essential. The following protocols represent standardized methodologies for assessing critical ADMET parameters.

Protocol: In Vitro Metabolic Stability Assay

Objective: To evaluate the metabolic stability of drug candidates using liver microsomes or hepatocytes, predicting in vivo clearance [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test compounds (10 mM stock in DMSO)

- Pooled human or rat liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL final protein concentration)

- NADPH regenerating system (1 mM NADP+, 10 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 1 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4)

- Stop solution (acetonitrile with internal standard)

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Methodology:

- Incubation Setup: Prepare incubation mixtures containing microsomes, buffer, and test compound (1 µM final concentration). Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the NADPH regenerating system.

- Time Course Sampling: Remove aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes) and transfer to stop solution to terminate metabolism.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge samples (14,000 × g, 10 minutes) to precipitate protein. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine parent compound concentration.

- Data Analysis: Plot remaining compound percentage versus time. Calculate half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) using the formula: CLint = (0.693 / t1/2) × (incubation volume / microsomal protein).

Protocol: Caco-2 Permeability Assay for Absorption Prediction

Objective: To assess intestinal permeability and potential for oral absorption using the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2).

Materials and Reagents:

- Caco-2 cells (passage number 25-40)

- Transwell inserts (0.4 µm pore size, 12 mm diameter)

- DMEM culture medium with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% L-glutamine

- Transport buffer (HBSS with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4)

- Test compound (10 mM stock in DMSO)

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Seed Caco-2 cells on Transwell inserts at high density (∼100,000 cells/insert) and culture for 21-28 days to allow differentiation and tight junction formation. Monitor transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) to confirm monolayer integrity.

- Experiment Setup: Replace culture medium with transport buffer. Add test compound (10 µM) to the donor compartment (apical for A→B transport, basolateral for B→A transport).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate at 37°C with gentle shaking. Sample from the receiver compartment at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes, replacing with fresh buffer.

- Analysis: Measure compound concentration in samples using LC-MS/MS. Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) × (1/(A × C0)), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C0 is the initial donor concentration.

- Data Interpretation: Papp > 1 × 10⁻⁶ cm/s suggests high permeability and likely good oral absorption. Efflux ratio (Papp B→A / Papp A→B) > 2 suggests involvement of active efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for ADMET Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in ADMET |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line [8] | Model of human intestinal epithelium | Prediction of oral absorption and permeability |

| Human Liver Microsomes [8] | Enzyme systems for Phase I metabolism | Metabolic stability and metabolite identification |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes [8] | Intact liver cells with full metabolic capacity | Hepatic clearance, metabolite profiling, enzyme induction |

| hERG-Expressing Cell Lines [2] | Assay for potassium channel binding | Prediction of cardiotoxicity risk (QT prolongation) |

| Transfected Cell Systems [8] | Overexpression of specific transporters (e.g., P-gp, BCRP) | Assessment of transporter-mediated DDI potential |

| Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) [8] | Ultra-sensitive detection of radiolabeled compounds | Human ADME studies with microdosing |

| PBPK Modeling Software [8] | Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic simulation | Prediction of human PK, DDI, and absorption |

Integrated Strategies and Future Directions

The evolving landscape of ADMET optimization reflects a shift from siloed, sequential testing to integrated, predictive approaches. Key advancements shaping this field include:

The Rise of AI-Driven Discovery Platforms

Several leading AI-driven drug discovery companies have successfully advanced novel candidates into the clinic by leveraging machine learning for ADMET optimization. For instance:

- Exscientia used generative AI to design and develop clinical compounds "at a pace substantially faster than industry standards," incorporating patient-derived biology into its discovery workflow [9].

- Insilico Medicine progressed an AI-designed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months [9].

- Schrödinger's physics-enabled design strategy advanced the TYK2 inhibitor, zasocitinib, into Phase III clinical trials [9].

Regulatory Harmonization and Best Practices

Recent initiatives like the ICH M12 guideline on drug-drug interaction studies aim to harmonize international regulatory requirements, providing clearer frameworks for in vitro and clinical DDI assessments [8]. This harmonization facilitates more standardized and predictive ADMET screening strategies across the industry.

Advanced Modeling and Simulation

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling has become increasingly integrated into discovery workflows, bridging the gap between in vitro assays and human pharmacokinetic predictions [8]. These models incorporate in vitro data on permeability, metabolism, and transporter interactions to simulate drug behavior in virtual human populations, enabling more informed candidate selection and clinical trial design.

The high cost of drug attrition due to poor ADMET properties represents both a fundamental challenge and a significant opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry. By leveraging advanced machine learning models, standardized high-quality experimental protocols, and integrated AI-driven platforms, researchers can front-load ADMET assessment into early discovery stages. This proactive approach enables the identification and optimization of drug candidates with a higher probability of clinical success, ultimately reducing the staggering economic and temporal costs associated with late-stage failures. The continued evolution of in silico tools, coupled with more predictive in vitro systems and sophisticated modeling approaches, promises to transform ADMET evaluation from a gatekeeping function to a strategic enabler of more efficient and successful drug development.

In modern drug discovery, the paradigm is decisively shifting from late-stage, reactive ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) evaluation to proactive, early-stage integration. This "shift left" approach addresses the stark reality that poor pharmacokinetics and unforeseen toxicity remain leading causes of clinical-stage attrition, accounting for approximately 30% of drug candidate failures [10]. Traditional drug development workflows often deferred ADMET assessment to later stages, relying on resource-intensive experimental methods that, while reliable, lacked the throughput required for early-phase decision-making [10]. The evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies has fundamentally transformed this landscape, providing scalable, efficient computational alternatives that decipher complex structure-property relationships [10] [11]. By integrating ADMET prediction into lead generation and optimization, researchers can now prioritize compounds with optimal pharmacokinetic and safety profiles before committing to extensive synthesis and testing, thereby mitigating late-stage attrition and accelerating the development of safer, more efficacious therapeutics [10].

The strategic importance of early ADMET integration is underscored by the continued dominance of small molecules in new therapeutic approvals, accounting for 65% of FDA-approved treatments in 2024 [10]. These compounds must navigate intricate biological systems to achieve therapeutic concentrations at their target sites while avoiding off-target toxicity, a balance governed by their fundamental ADMET characteristics [10]. Absorption determines the rate and extent of drug entry into systemic circulation; distribution reflects dissemination across tissues and organs; metabolism describes biotransformation processes influencing drug half-life and bioactivity; excretion facilitates clearance; and toxicity remains the pivotal consideration for human safety [10]. Computational approaches now enable the high-throughput prediction of these critical properties directly from chemical structure, positioning ADMET assessment as a foundational element—rather than a downstream checkpoint—in contemporary drug discovery pipelines [10] [11].

Core ADMET Properties and Their Impact on Candidate Viability

The ADMET profile of a drug candidate constitutes a critical determinant of its clinical success, with each property governing specific aspects of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Understanding these fundamental parameters and their interrelationships enables more effective compound design and optimization throughout the drug discovery process.

Table 1: Core ADMET Properties and Their Experimental/Prediction Methodologies

| ADMET Property | Impact on Drug Candidate | Common Experimental Measures | Computational Prediction Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Determines bioavailability and dosing regimen | Caco-2 permeability, PAMPA, P-glycoprotein substrate identification | Predicted permeability, P-gp substrate likelihood, intestinal absorption % [10] [12] |

| Distribution | Affects tissue targeting and off-target exposure | Blood-to-plasma ratio, plasma protein binding, logD | Predicted volume of distribution, blood-brain barrier penetration, plasma protein binding [10] [13] |

| Metabolism | Influences half-life, drug-drug interactions | Microsomal/hepatocyte stability, CYP450 inhibition/induction | CYP450 inhibition/isoform specificity, metabolic stability, sites of metabolism [10] [13] |

| Excretion | Impacts dosing frequency and accumulation | Biliary and renal clearance measurements | Clearance rate predictions, transporter interactions [10] [13] |

| Toxicity | Determines safety margin and therapeutic index | Ames test, hERG inhibition, hepatotoxicity assays | Predicted mutagenicity, cardiotoxicity (hERG), hepatotoxicity, organ-specific toxicity [10] [14] |

The relationship between molecular properties and these ADMET endpoints is complex and often nonlinear. For instance, intestinal permeability, frequently evaluated using Caco-2 cell models, helps predict how effectively a drug crosses intestinal membranes, while interactions with efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) can actively transport compounds out of cells, limiting absorption and bioavailability [10] [12]. Distribution characteristics, particularly blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, determine whether compounds reach central nervous system targets or avoid central liabilities [10]. Metabolic stability, primarily mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes (especially CYP3A4), directly impacts drug half-life and exposure, while inhibition of these enzymes poses significant drug-drug interaction risks [10]. Toxicity endpoints, such as hERG channel binding associated with cardiac arrhythmia, represent critical safety liabilities that must be eliminated during optimization [10] [15].

The emergence of comprehensive benchmarks like PharmaBench, which aggregates data from 14,401 bioassays and contains 52,482 entries for eleven key ADMET properties, provides the foundational datasets necessary for robust model development [16]. These resources address previous limitations in dataset size and chemical diversity, particularly the underrepresentation of compounds relevant to drug discovery projects (typically 300-800 Dalton molecular weight), enabling more accurate predictions for lead-like chemical space [16]. By mapping these complex structure-property relationships, researchers can establish predictive frameworks that guide molecular design toward regions of favorable ADMET space, substantially de-risking the candidate selection process.

Machine Learning Approaches for ADMET Prediction

Machine learning technologies have catalyzed a paradigm shift in ADMET prediction, moving beyond traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to advanced algorithms capable of deciphering complex, high-dimensional structure-property landscapes [10] [11]. ML approaches leverage large-scale compound databases to enable high-throughput predictions with improved efficiency, addressing the inherent challenges posed by the nonlinear nature of biological systems [10]. These methodologies range from feature representation learning to deep neural networks and ensemble strategies, each offering distinct advantages for specific ADMET prediction tasks.

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches for ADMET Prediction

| ML Approach | Key Features | Representative Algorithms | ADMET Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Directly operates on molecular graph structure; captures atomic interactions and topology | Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN), Graph Attention Networks (GAT) | Metabolic stability prediction, toxicity endpoints, permeability [10] [11] |

| Ensemble Methods | Combines multiple models to improve robustness and predictive accuracy | Random Forest, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | Caco-2 permeability, solubility, plasma protein binding [10] [12] |

| Multitask Learning (MTL) | Simultaneously learns multiple related tasks; improves data efficiency and generalizability | Multitask DNN, Multitask GNN | Concurrent prediction of related ADMET endpoints (e.g., multiple CYP450 isoforms) [10] |

| Transformer/Language Models | Processes SMILES strings as sequential data; captures contextual molecular patterns | BERT-based architectures, SMILES transformers | Drug-drug interaction prediction, molecular property estimation [16] [14] |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combines multiple representations and algorithms for enhanced performance | GNN + Descriptor fusion, Multimodal fusion | Comprehensive ADMET profiling, cross-property optimization [12] [11] |

The performance of these ML approaches is highly dependent on both algorithmic selection and molecular representation. For Caco-2 permeability prediction, systematic comparisons reveal that ensemble methods like XGBoost often provide superior predictions compared to other models, particularly when combined with comprehensive molecular representations such as Morgan fingerprints and RDKit 2D descriptors [12]. Similarly, graph neural networks demonstrate exceptional capability in modeling toxicity endpoints like drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and hERG-mediated cardiotoxicity by directly capturing atom-level interactions and functional group contributions [10] [14]. Emerging strategies include multimodal data integration, where molecular structures are combined with pharmacological profiles, gene expression data, and experimental conditions to enhance model robustness and clinical relevance [10] [16].

Recent advancements also address the critical challenge of model interpretability through techniques such as attention mechanisms, gradient-based attribution, and counterfactual explanations [10] [14]. For instance, the ADMET-PrInt tool incorporates local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) and counterfactual explanations to help researchers understand the structural features driving specific ADMET predictions [14]. These interpretability features are essential for building trust in ML predictions and providing medicinal chemists with actionable insights for structural optimization, ultimately bridging the gap between predictive algorithms and practical drug design decisions [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

High-Throughput ADMET Screening Protocol

The transition to early ADMET assessment requires robust, standardized experimental protocols that generate high-quality data for both candidate evaluation and computational model development. A representative protocol for Caco-2 permeability assessment—a critical absorption endpoint—demonstrates the integration of experimental and computational approaches:

Protocol: Integrated Caco-2 Permeability Screening and Modeling

Cell Culture and Monolayer Preparation: Plate Caco-2 cells at high density on collagen-coated transwell filters. Culture for 21 days with regular medium changes to ensure complete differentiation into enterocyte-like phenotype. Verify monolayer integrity by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) ≥ 300 Ω·cm² before experimentation [12].

Permeability Assay: Prepare compound solutions in transport buffer (e.g., HBSS with 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Apply donor solution to apical (for A→B transport) or basolateral (for B→A transport) chamber. Incubate at 37°C with agitation. Sample from receiver chambers at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) [12].

Analytical Quantification: Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to determine compound concentrations. Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C₀ is the initial donor concentration [12].

Data Standardization: Convert permeability measurements to consistent units (cm/s × 10⁻⁶) and apply logarithmic transformation (logPapp) for modeling. For duplicate measurements, retain only entries with standard deviation ≤ 0.3 and use mean values for subsequent analysis [12].

Computational Model Building: Employ molecular standardization using RDKit's MolStandardize to achieve consistent tautomer canonical states and neutral forms. Generate multiple molecular representations including Morgan fingerprints (radius 2, 1024 bits), RDKit 2D descriptors, and molecular graphs for algorithm training [12].

Model Training and Validation: Implement multiple machine learning algorithms (XGBoost, Random Forest, SVM, DMPNN) using training/validation/test splits (typically 8:1:1 ratio). Perform Y-randomization testing and applicability domain analysis to assess model robustness. Validate against external industry datasets to evaluate transferability [12].

This integrated protocol highlights the synergy between experimental measurement and computational prediction, enabling the development of models that can reliably prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing.

Workflow for Early ADMET Integration

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for integrating ADMET assessment throughout lead generation and optimization:

Integrated ADMET Workflow in Drug Discovery

This workflow demonstrates the progressive intensification of ADMET assessment throughout the discovery pipeline, beginning with computational predictions during lead generation, advancing to targeted experimental screening in lead optimization, and culminating in comprehensive profiling for preclinical candidate selection. The foundation of this approach rests on AI/ML prediction platforms that enable data-driven decision-making at each stage.

Successful implementation of early ADMET assessment requires access to specialized computational tools, datasets, and analytical resources. The following toolkit compiles essential solutions for researchers establishing or enhancing ADMET capabilities within their discovery workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial ADMET Platforms | ADMET Predictor [13], ADMET-AI [15] | Comprehensive property prediction (>175 endpoints), PBPK modeling, risk assessment | Enterprise-level ADMET integration; high-throughput screening of virtual compounds |

| Open-Source ML Frameworks | Chemprop [14], Deep-PK [11], RDKit [12] | Graph neural network implementation, toxicity prediction, molecular descriptor calculation | Custom model development; academic research; specific endpoint optimization |

| Benchmark Datasets | PharmaBench [16], TDC [16], MoleculeNet [16] | Curated ADMET data with standardized splits; performance benchmarking | Model training and validation; algorithm comparison; transfer learning |

| Web Servers & APIs | ADMETlab 3.0 [14], ProTox 3.0 [14], ADMET-PrInt [14] | Web-based property prediction; REST API integration; explainable AI | Rapid compound profiling; tool interoperability; educational use |

| Specialized Toxicity Tools | hERG prediction models [14], DILI predictors [14], Cardiotoxicity platforms [14] | Target-specific risk assessment; structural alert identification | Safety profiling; lead optimization; liability mitigation |

The multi-agent LLM system for data extraction represents an emerging approach to overcoming data curation challenges. This system employs three specialized agents: a Keyword Extraction Agent (KEA) that identifies key experimental conditions from assay descriptions, an Example Forming Agent (EFA) that generates few-shot learning examples, and a Data Mining Agent (DMA) that extracts structured experimental conditions from unstructured text [16]. This approach has enabled the creation of large-scale, consistently annotated benchmarks like PharmaBench, which incorporates experimental conditions that significantly influence measurement outcomes (e.g., buffer composition, pH, experimental procedure) [16].

For predictive model implementation, the ADMET Risk scoring system provides an illustrative framework for integrating multiple property predictions into a unified risk assessment. This system employs "soft" thresholds that assign fractional risk values based on proximity to undesirable property ranges, combining risks across absorption (AbsnRisk), CYP metabolism (CYPRisk), and toxicity (TOX_Risk) into a composite score that helps prioritize compounds with the highest probability of success [13]. Such integrated scoring approaches facilitate decision-making by distilling complex multidimensional data into actionable insights for medicinal chemists.

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges persist in the widespread implementation of early ADMET prediction. Model interpretability remains a critical barrier, with many advanced deep learning architectures operating as "black boxes" that limit mechanistic understanding and hinder trust among medicinal chemists [10] [11]. Emerging explainable AI (XAI) approaches, including attention mechanisms, gradient-based attribution, and counterfactual explanations, are addressing this limitation by highlighting structural features responsible for specific ADMET predictions [10] [14]. Additionally, the generalizability of models beyond their training chemical space continues to present difficulties, particularly for novel scaffold classes or underrepresented therapeutic areas [10] [12]. Applicability domain analysis and conformal prediction methods are evolving to quantify prediction uncertainty and identify when models are operating outside their reliable scope [14].

The quality and heterogeneity of training data constitute another significant challenge. Experimental results for identical compounds can vary substantially under different conditions—for example, aqueous solubility measurements influenced by buffer composition, pH levels, and experimental procedures [16]. The development of multi-agent LLM systems for automated data extraction and standardization represents a promising approach to addressing these inconsistencies, enabling the creation of larger, more consistently annotated datasets [16]. Furthermore, the integration of multimodal data sources, including molecular structures, bioassay results, omics data, and clinical information, presents both a challenge and opportunity for enhancing model robustness and clinical relevance [10] [11].

Future directions in ADMET prediction point toward increasingly integrated, AI-driven workflows that span the entire drug discovery and development continuum. Hybrid AI-quantum computing frameworks show potential for more accurate molecular simulations and property predictions [11]. The convergence of AI with structural biology through advanced molecular dynamics and free energy perturbation calculations enables more precise prediction of binding affinities and metabolic transformations [11]. Additionally, the growing adoption of generative AI models for de novo molecular design incorporates ADMET constraints directly into the compound generation process, fundamentally shifting the paradigm from predictive filtering to proactive design of compounds with inherently optimized properties [17] [11]. These innovations collectively promise to further accelerate the shift left of ADMET assessment, solidifying its role as a cornerstone of modern, efficient drug discovery.

The acronym ADMET stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. These parameters describe the disposition of a pharmaceutical compound within an organism and critically influence the drug levels, kinetics of drug exposure to tissues, and the ultimate pharmacological activity and safety profile of the compound [18]. In the context of early drug discovery research, ADMET prediction is paramount for de-risking the development pipeline. It is estimated that close to 50% of drug candidates fail due to unacceptable efficacy, and up to 40% have historically failed due to toxicity issues [19]. By identifying ADMET liabilities early, researchers can increase the probability of clinical success, decrease overall costs, and reduce time to market [20].

The term ADME was first introduced in the 1960s, building on seminal works like those of Teorell (1937) and Widmark (1919) [21]. The inclusion of Toxicity (T) created the now-standard ADMET acronym, widely used in scientific literature, drug regulation, and clinical practice [18]. An alternative framework, ABCD (Administration, Bioavailability, Clearance, Distribution), has also been proposed to refocus the descriptors on the active drug moiety in the body over space and time [21]. However, the ADMET paradigm remains the cornerstone for evaluating a compound's druggability.

Defining the Core ADMET Parameters

Absorption

Absorption is the first stage of pharmacokinetics and refers to the process by which a drug enters the systemic circulation from its site of administration [22]. The extent and rate of absorption critically determine a drug's bioavailability—the fraction of the administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged [21].

Factors influencing drug absorption are multifaceted and include:

- Drug Solubility and Chemical Stability: Poor compound solubility or instability in the gastric environment can limit absorption [18].

- Route of Administration: This is a primary consideration. Common routes include oral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, transdermal, and inhalation [22]. Each route presents unique barriers and absorption characteristics.

- Physiological Factors: Gastric emptying time, intestinal transit time, and the ability to permeate the intestinal wall are critical, especially for oral administration [18].

- First-Pass Effect: For medications administered orally or enterally, a significant portion of the drug may be deactivated by enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract and liver before it reaches the systemic circulation. This process results in a reduced concentration of the active drug and is known as the first-pass effect [22]. Alternative routes like intravenous, transdermal, or inhalation can bypass this effect.

Distribution

Distribution is the reversible transfer of a drug between the systemic circulation and various tissues and organs throughout the body [22] [18]. Once a drug enters the bloodstream, it is carried to its effector site, but it also distributes to other tissues, often to differing extents.

Key factors affecting drug distribution include:

- Regional Blood Flow: Organs with high blood flow, such as the heart, liver, and kidneys, often receive the drug more rapidly.

- Molecular Size and Polarity: These properties influence a drug's ability to cross cellular membranes.

- Protein Binding: Drugs can bind to serum proteins (e.g., albumin), forming a complex that is too large to cross capillary walls and is thus pharmacologically inactive. Only the unbound (free) drug can exert a therapeutic effect [22] [18].

- Barriers to Distribution: Natural barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier, can pose significant challenges for drugs intended to act on the central nervous system [18].

Metabolism

Metabolism, also known as biotransformation, is the process by which the body breaks down drug molecules [22]. The primary site for the metabolism of small-molecule drugs is the liver, largely mediated by redox enzymes, particularly the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family [18].

The consequences of metabolism are pivotal:

- Deactivation: Most metabolites are pharmacologically inert, meaning metabolism deactivates the administered parent drug and terminates its effect [18].

- Activation: Some metabolites are pharmacologically active. In the case of prodrugs, the administered compound is inactive, and it is the metabolite that produces the therapeutic effect [18]. Sometimes, metabolites can be more active or toxic than the parent drug.

- Clearance: Metabolism is a key component of clearance, which is the irreversible removal of the active drug from the systemic circulation [21].

Excretion

Excretion is the final stage of pharmacokinetics and refers to the process by which the body eliminates drugs and their metabolites [22]. This process must be efficient to prevent the accumulation of foreign substances, which can lead to adverse effects [18].

The main routes and mechanisms of excretion are:

- Renal Excretion (via urine): This is the most important route of excretion. It involves three main mechanisms: glomerular filtration of unbound drug, active secretion by transporters, and passive reabsorption in the tubules [18].

- Biliary/Fecal Excretion: The liver can excrete drugs or metabolites into the bile, which are then passed into the feces.

- Other Routes: Excretion can also occur via the lungs (e.g., anesthetic gases) and through sweat or saliva.

Two key pharmacological indicators for renal excretion are the fraction of drug excreted unchanged in urine (fe), which shows the contribution of renal excretion to overall elimination, and renal clearance (CLr), which is the volume of plasma cleared of the drug by the kidneys per unit time [23].

Toxicity

Toxicity encompasses the potential or real harmful effects of a compound on the body [18]. Evaluating toxicity is crucial for understanding a drug's safety profile and is a major cause of late-stage drug attrition [19].

Toxicity can manifest in various ways, including:

- Organ-Specific Toxicity: Such as hepatotoxicity (liver) or cardiotoxicity (heart), the latter often linked to inhibition of the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) channel [24] [20].

- Genotoxicity: The ability of a compound to damage DNA, leading to mutations. Common tests include the Ames test [20].

- Carcinogenicity: The potential to cause cancer [24].

- Cytotoxicity: General toxicity to cells, often assessed through cell viability assays [20].

Parameters used to characterize toxicity include the median lethal dose (LD50) and the therapeutic index, which compares the therapeutic dose to the toxic dose [18].

Table 1: Summary of Core ADMET Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Key Determinants | Common Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Process of a drug entering systemic circulation [22] | Route of administration, solubility, chemical stability, first-pass effect [22] [18] | Caco-2 permeability assay, PAMPA, P-gp substrate assays [24] [20] |

| Distribution | Reversible transfer of drug between blood and tissues [18] | Blood flow, protein binding, molecular size, polarity [18] | Plasma protein binding assays, volume of distribution (Vd) studies [19] |

| Metabolism | Biochemical breakdown of a drug molecule [22] | Cytochrome P450 enzymes,UGT enzymes [18] [19] | Liver microsomes, hepatocytes (CYP inhibition/induction) [25] [19] |

| Excretion | Elimination of drug and metabolites from the body [22] | Renal function, transporters, biliary secretion [18] | Urinary/fecal recovery studies, renal clearance models [23] |

| Toxicity | The potential of a drug to cause harmful effects [18] | Off-target interactions, reactive metabolites [19] | hERG inhibition, Ames test, cytotoxicity assays (e.g., HepG2) [24] [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A robust ADMET screening strategy employs a combination of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methods. The following are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in ADMET research.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity Assays

Objective: To assess the general cytotoxic and mutagenic potential of a new chemical entity (NCE) in a high-throughput format [20].

Protocol for Multiplexed Cytotoxicity Evaluation (as used at UCB Pharma) [20]:

- Cell Culture: Plate equilibrated cells (e.g., HepG2 human hepatoma cell line) in 96-well plates and incubate overnight.

- Dosing: Expose cells to a range of concentrations of the test compound for 2 and 24 hours.

- Multiplexed Endpoint Analysis: Measure the following parameters in each well:

- Cell Viability: Using assays like MTT or Alamar Blue.

- Membrane Integrity: By measuring Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release.

- Cellular Energy Levels: Via Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) measurement.

- Apoptosis Induction: By assessing caspase activity.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the LC50 value (concentration lethal to 50% of cells) for each endpoint to determine the cytotoxic potential.

Protocol for Genotoxicity Screening [20]:

- High-Throughput Pre-screening: Use bacterial or yeast-based assays like VitoTox or GreenScreen that monitor the induction of DNA-repair enzymatic activity.

- Confirmatory Testing: Confirm positive results from HTS assays using the Ames II test, which measures the ability of the compound to cause mutations in bacterial cells, allowing them to grow on selective media. This test is predictive of the regulatory gold standard, the miniAmes test.

In Vitro Permeability and Metabolism Studies

Objective: To predict human intestinal absorption and drug-drug interaction potential.

Protocol for Caco-2 Permeability Assay [20] [19]:

- Model Setup: Culture Caco-2 cells (human colon adenocarcinoma cell line) on semi-permeable filter supports until they form a confluent, differentiated monolayer that mimics the intestinal epithelium.

- Validation: Measure the Trans Epithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) to confirm monolayer integrity.

- Dosing: Add the test compound to the donor compartment (e.g., apical side for absorption studies).

- Sampling: At designated time points, sample from the receiver compartment (e.g., basolateral side).

- Analysis: Use HPLC or LC/MS to quantify the compound that has traversed the monolayer. Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp).

Protocol for CYP Inhibition Assay [19]:

- Incubation: Incubate test compound with human liver microsomes or recombinant CYP enzymes in the presence of a CYP-specific probe substrate and the cofactor NADPH.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction at linear time points with a quenching agent (e.g., acetonitrile).

- Metabolite Quantification: Use LC-MS/MS to measure the formation rate of the specific metabolite from the probe substrate.

- Data Analysis: Compare the metabolite formation rate in the presence of the test compound to a control (without inhibitor) to determine the percentage inhibition and calculate the IC50 value.

In Silico Prediction of Renal Excretion

Objective: To predict the human fraction of drug excreted unchanged in urine (fe) and renal clearance (CLr) using only chemical structure information [23].

Protocol for fe and CLr Prediction [23]:

- Data Set Curation: Assemble a dataset of compounds with known fe or CLr values from reliable sources (e.g., PharmaPendium, ChEMBL).

- Descriptor Calculation: Use open-source software (e.g., Mordred, PaDEL-Descriptor) to calculate 2D molecular descriptors and fingerprints from the compound's chemical structure.

- Model Building:

- For fe, build a binary classification model (e.g., using Random Forest) to predict if a compound has high or low urinary excretion.

- For CLr, create a two-step system: First, a classification model predicts the excretion type (reabsorption, intermediate, or secretion). Second, separate regression models for each type predict the numerical CLr value.

- Model Validation: Split the data into training and test sets. Validate model performance on the test set using metrics like balanced accuracy for classification and fold-error for regression.

- Public Availability: The finalized model can be deployed as a freely available web tool for use by the scientific community.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for ADMET Studies

| Reagent/Model | Function in ADMET Testing | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Contain metabolic enzymes (CYP450, UGT) for in vitro metabolism studies [19] | Predicting metabolic stability, metabolite identification, and CYP inhibition studies [25] [19] |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Gold-standard cell-based model containing a full complement of hepatic enzymes and transporters [20] [19] | Studying complex metabolism, enzyme induction, and species-specific differences [20] |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon cancer cell line that forms polarized monolayers mimicking the intestinal barrier [20] | Assessing intestinal permeability and active transport mechanisms (e.g., P-gp efflux) [19] |

| HepG2 Cell Line | A human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line used for toxicity screening [20] | Multiplexed cytotoxicity assays (viability, LDH, ATP, apoptosis) [20] |

| PAMPA Plates | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay; a non-cell-based model for passive diffusion [20] | High-throughput screening of passive transcellular permeability [20] |

| Transil Kits | Bead-based technology coated with brain lipid membranes or other relevant membranes [20] | Predicting brain absorption or intestinal absorption in a high-throughput format [20] |

| hERG-Expressing Cells | Cell lines engineered to express the hERG potassium channel [20] | In vitro screening for potential cardiotoxicity (QT interval prolongation) [24] [20] |

| EpiAirway System | A 3D, human cell-based model of the tracheal/bronchial epithelium [20] | Evaluating inhalation route absorption and local toxicity [20] |

ADMET Workflow in Early Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how ADMET studies are integrated into the early drug discovery process to inform decision-making.

ADMET Integration in Drug Discovery

A deep understanding of the core ADMET parameters—Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity—is non-negotiable in modern drug discovery. As detailed in this guide, these parameters are interdependent and critically determine the safety and efficacy of a new chemical entity. The integration of robust in silico prediction tools, high-throughput in vitro assays, and targeted in vivo studies into the early research phases provides a powerful framework for evaluating and optimizing the druggability of lead compounds. By systematically applying these concepts and methodologies, researchers and drug development professionals can make more informed decisions, prioritize the most promising candidates, and significantly reduce the high rates of late-stage attrition that have long plagued the pharmaceutical industry. The continued evolution of ADMET prediction technologies promises to further enhance the efficiency and success of bringing new therapeutics to patients.

The journey from Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) to artificial intelligence (AI) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in pharmacological research. This evolution has transformed drug discovery from a largely trial-and-error process to a sophisticated, data-driven science capable of predicting molecular behavior with remarkable accuracy. At the heart of this transformation lies the critical importance of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction in early-stage research, where these properties now serve as decisive filters for selecting viable drug candidates. The integration of AI-powered computational approaches has revolutionized molecular modeling and ADMET prediction, enabling researchers to interpret complex molecular data, automate feature extraction, and improve decision-making across the entire drug development pipeline [11].

The pharmaceutical industry's embrace of these technologies is driven by compelling economic and scientific imperatives. Traditional drug development requires an average of 14.6 years and approximately $2.6 billion to bring a new drug to market [26]. AI-powered approaches are projected to generate between $350 billion and $410 billion annually for the pharmaceutical sector by 2025, primarily through innovations that streamline drug development, enhance clinical trials, enable precision medicine, and optimize commercial operations [26]. By integrating AI with established computational methods, researchers can now reduce drug discovery costs by up to 40% and slash development timelines from five years to as little as 12-18 months [26].

The Foundations: Classical QSAR Modeling

Historical Development and Fundamental Principles

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling emerged as the foundational framework for predictive pharmacology, establishing mathematical relationships between chemical structures and their biological activities. The core hypothesis underpinning QSAR is that molecular structure descriptors can be quantitatively correlated with biological response, enabling property prediction based on structural characteristics alone. This approach represented a significant advancement over previous qualitative structure-activity relationship observations, providing a systematic methodology for chemical space navigation and activity prediction.

Classical QSAR methodologies relied heavily on statistical modeling techniques including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Principal Component Regression (PCR). These approaches were valued for their simplicity, speed, and interpretability, particularly in regulatory settings where understanding model decision processes was essential. The molecular descriptors employed in these models evolved from simple one-dimensional (1D) properties like molecular weight to more sophisticated two-dimensional (2D) topological indices and three-dimensional (3D) descriptors capturing molecular shape and electrostatic potential maps [27].

Molecular Descriptors and Statistical Techniques

The predictive power of QSAR models depends critically on the molecular descriptors that numerically encode various chemical, structural, and physicochemical properties. These descriptors are systematically categorized by dimensionality:

Table: Classification of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Type | Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Molecular weight, atom count | Preliminary screening, simple property estimation |

| 2D Descriptors | Topological indices, connectivity indices | Virtual screening, similarity analysis |

| 3D Descriptors | Molecular surface area, volume, shape descriptors | Protein-ligand docking, conformational analysis |

| 4D Descriptors | Conformational ensembles, interaction fields | Pharmacophore modeling, QSAR refinement |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, molecular orbital energies | Electronic property prediction, reactivity assessment |

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) became essential for enhancing model efficiency and reducing overfitting. Feature selection methods including LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) and mutual information ranking helped identify the most significant molecular features, improving both model performance and interpretability [27].

Experimental Protocol: Classical QSAR Model Development

Software and Tools: QSARINS, Build QSAR, DRAGON, PaDEL, RDKit [27] [28]

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Dataset Curation: Collect and curate a homogeneous set of compounds with consistent biological activity measurements (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki). A typical dataset should include 37+ compounds to ensure statistical significance [28].

Structure Optimization: Draw 2D molecular structures using chemoinformatics software (e.g., ChemDraw Professional) and convert to 3D structures. Perform geometry optimization using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with Becke's three-parameter exchange functional hybrid with the Lee, Yang, and Parr correlation functional (B3LYP) and basis set of 6-31G [28].

Descriptor Calculation: Calculate molecular descriptors using software packages like PaDEL or DRAGON. Generate 1,500+ molecular descriptors encompassing topological, electronic, and physicochemical properties [28].

Dataset Division: Split the dataset into training (70%) and evaluation sets (30%) using algorithms such as Kennard and Stone's approach to ensure representative chemical space coverage [28].

Descriptor Selection and Model Building: Employ genetic algorithms and ordinary least squares methods in QSARINS software to select optimal descriptor combinations. Apply a cutoff value of R² > 0.6 for descriptor selection [28].

Model Validation: Validate model robustness using both internal (cross-validation, leave-one-out Q²) and external validation (evaluation set prediction R²). Apply Golbraikh and Tropsha acceptable model criteria: Q² > 0.5, R² > 0.6, R²adj > 0.6, and |r₀²−r'₀²| < 0.3 [28].

Domain of Applicability (DA) Assessment: Define the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions using leverage calculations and hat matrices. The threshold value is typically set at ± 3 [28].

Y-Randomization Testing: Perform Y-randomization to confirm model robustness by rearranging the evaluation set activities. Validate using cR₂p ≥ 0.5 for the Y-randomization coefficient to ensure the model wasn't obtained by chance [28].

Classical QSAR Modeling Workflow

The AI Revolution in Pharmacological Modeling

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Integration

The integration of artificial intelligence into pharmacological modeling represents a fundamental shift from traditional statistical approaches to data-driven pattern recognition. Machine learning (ML) algorithms including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) have become standard tools in cheminformatics, capable of capturing complex nonlinear relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activity without prior assumptions about data distribution [27]. The robustness of Random Forests against noisy data and redundant descriptors makes them particularly valuable for handling high-dimensional chemical datasets.

Deep learning (DL) architectures have further expanded predictive capabilities through graph neural networks (GNNs) and SMILES-based transformers that automatically learn hierarchical molecular representations without manual feature engineering. These approaches generate "deep descriptors" - latent embeddings that capture abstract molecular features directly from molecular graphs or SMILES strings, enabling more flexible and data-driven QSAR pipelines across diverse chemical spaces [27]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated remarkable performance in QSAR modeling, as evidenced by their application in screening natural products as tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitors for Parkinson's disease treatment [29].

Key Algorithmic Advancements and Applications

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs operate directly on molecular graph structures, atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, enabling natural representation of molecular topology. This approach has proven particularly effective for molecular property prediction and virtual screening [11].

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): These generative models facilitate de novo drug design by creating novel molecular structures with optimized properties. GANs employ a generator-discriminator framework to produce chemically valid structures, while VAEs learn continuous latent spaces for molecular representation [11].

Transformers and Attention Mechanisms: Originally developed for natural language processing, transformer architectures adapted for SMILES strings or molecular graphs can capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within molecular structures, significantly improving predictive accuracy [11] [27].

Multi-Task Learning: This approach enables simultaneous prediction of multiple ADMET endpoints by sharing representations across related tasks, addressing data scarcity issues and improving model generalizability through inductive transfer [11].

Experimental Protocol: AI-Enhanced QSAR with ADMET Prediction

Software and Tools: Deep-PK, DeepTox, admetSAR 2.0, SwissADME, PharmaBench [11] [24] [30]

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Collection and Curation: Access large-scale benchmark datasets like PharmaBench, which contains 52,482 entries across eleven ADMET properties compiled from ChEMBL, PubChem, and BindingDB using multi-agent LLM systems for experimental condition extraction [16].

Molecular Representation: Implement learned molecular representations using graph neural networks or SMILES-based transformers instead of manual descriptor engineering. These latent embeddings capture hierarchical molecular features directly from structure [27].

Model Architecture Selection: Choose appropriate architectures based on data characteristics:

- Graph Neural Networks for molecular property prediction

- Convolutional Neural Networks for image-like structural data

- Recurrent Neural Networks for sequential SMILES data

- Ensemble Methods for improved robustness and accuracy

Multi-Task Learning Framework: Implement shared representation learning across multiple ADMET endpoints to leverage correlations between related properties and address data scarcity [11].

Model Training and Regularization: Employ advanced regularization techniques including dropout, batch normalization, and early stopping to prevent overfitting. Use Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning [27].

Interpretability Analysis: Apply model-agnostic interpretation methods including SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to identify influential molecular features and maintain regulatory compliance [27].

Validation and Benchmarking: Evaluate model performance using both random and scaffold splits to assess generalizability across chemical space. Compare against classical QSAR models and existing benchmarks [16].

ADMET Prediction: The Cornerstone of Modern Drug Discovery

The Critical Role of ADMET in Early-Stage Research

ADMET properties have emerged as decisive factors in early drug discovery, serving as critical filters for candidate selection and optimization. Historical analysis reveals that inadequate pharmacokinetics and toxicity account for approximately 60% of drug candidate failures during development [24]. The implementation of comprehensive ADMET profiling during early stages has therefore become essential for mitigating late-stage attrition rates and improving clinical success probabilities.

The paradigm has shifted from simple rule-based filters like Lipinski's "Rule of Five" to quantitative, multi-parameter optimization. The development of integrated scoring functions such as the ADMET-score provides researchers with a comprehensive metric for evaluating chemical drug-likeness across 18 critical ADMET properties [24]. This approach enables more nuanced candidate selection compared to binary classification methods, acknowledging the continuous nature of drug-likeness while incorporating essential in vivo and in vitro ADMET properties beyond simple physicochemical parameters.

Essential ADMET Endpoints and Predictive Modeling

Table: Critical ADMET Properties for Early-Stage Drug Discovery

| ADMET Category | Key Endpoints | Prediction Accuracy | Significance in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA), Caco-2 permeability | HIA: 0.965, Caco-2: 0.768 [24] | Determines oral bioavailability and dosing regimen |

| Distribution | Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration, P-glycoprotein substrate | P-gp substrate: 0.802 [24] | Influences target tissue exposure and central nervous system effects |

| Metabolism | CYP450 inhibition (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4), CYP450 substrate | Varies 0.645-0.855 [24] | Predicts drug-drug interactions and metabolic stability |

| Excretion | Organic cation transporter protein 2 inhibition | OCT2i: 0.808 [24] | Affects clearance rates and potential organ toxicity |

| Toxicity | Ames mutagenicity, hERG inhibition, Carcinogenicity, Acute oral toxicity | Ames: 0.843, hERG: 0.804 [24] | Identifies safety liabilities and potential clinical adverse effects |

The accuracy metrics demonstrate the current capabilities of AI-powered ADMET prediction models, with human intestinal absorption models achieving exceptional accuracy (0.965) while areas like CYP3A4 substrate prediction show room for improvement (0.66) [24]. These quantitative assessments enable researchers to make informed decisions about compound prioritization early in the discovery pipeline.

Integrated ADMET Scoring and Decision-Making

The ADMET-score represents a significant advancement in comprehensive drug-likeness evaluation, integrating 18 predicted ADMET properties into a single quantitative metric [24]. This scoring function incorporates three weighting parameters: the accuracy rate of each predictive model, the importance of the endpoint in the pharmacokinetic process, and a usefulness index derived from experimental validation. The implementation of such integrated scoring systems has demonstrated statistically significant differentiation between FDA-approved drugs, general small molecules from ChEMBL, and withdrawn drugs, confirming its utility in candidate selection [24].

Integrated Computational Workflows: Case Studies and Applications

Case Study 1: Anti-Tuberculosis Nitroimidazole Compounds

A comprehensive computational study exemplifies the power of integrated AI-QSAR approaches in developing anti-tuberculosis agents targeting the Ddn protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [30]. The workflow incorporated multiple computational techniques:

QSAR Modeling: Researchers developed a multiple linear regression-based QSAR model with strong predictive accuracy (R² = 0.8313, Q²LOO = 0.7426) using QSARINS software [30].

Molecular Docking: AutoDockTool 1.5.7 identified DE-5 as the most promising compound with a binding affinity of -7.81 kcal/mol and crucial hydrogen bonding interactions with active site residues PRO A:63, LYS A:79, and MET A:87 [30].

ADMET Profiling: SwissADME analysis confirmed DE-5's high bioavailability, favorable pharmacokinetics, and low toxicity risk [30].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A 100 ns simulation demonstrated the stability of the DE-5-Ddn complex, with minimal Root Mean Square deviation, stable hydrogen bonds, low Root Mean Square Fluctuation, and compact structure reflected in Solvent Accessible Surface Area and radius of gyration values [30].

Binding Affinity Validation: MM/GBSA computations (-34.33 kcal/mol) confirmed strong binding affinity, supporting DE-5's potential as a therapeutic candidate [30].

Case Study 2: Parkinson's Disease Tryptophan 2,3-Dioxygenase Inhibitors

Another study showcasing integrated computational methods focused on identifying natural products as tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) inhibitors for Parkinson's disease treatment [29]:

CNN-Based QSAR Modeling: Machine learning and convolutional neural network-based QSAR models predicted TDO inhibitory activity with high accuracy [29].

Virtual Screening and Docking: Molecular docking revealed strong binding affinities for several natural compounds, with docking scores ranging from -9.6 to -10.71 kcal/mol, surpassing the native substrate tryptophan (-6.86 kcal/mol) [29].

ADMET Profiling: Comprehensive assessment confirmed blood-brain barrier penetration capability, suggesting potential central nervous system activity for the selected compounds [29].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Provided insights into binding stability and dynamic behavior of top candidates within the TDO active site under physiological conditions, with Peniciherquamide C maintaining stronger and more stable interactions than the native substrate throughout simulation [29].

Energy Decomposition Analysis: MM/PBSA decomposition highlighted the energetic contributions of van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation forces, further supporting the binding stability of key compounds [29].

Integrated AI-Driven Drug Discovery Workflow

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AI-Enhanced Pharmacology

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR Modeling Software | QSARINS, Build QSAR, DRAGON | Descriptor calculation, model development, validation | Develop robust QSAR models with strict validation protocols [27] [28] |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDockTool, Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Protein-ligand interaction analysis, binding affinity prediction | Evaluate compound binding modes and interactions with target proteins [30] |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | admetSAR 2.0, SwissADME, Deep-PK, DeepTox | Comprehensive ADMET property prediction | Early-stage pharmacokinetic and toxicity screening [11] [24] [30] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Biomolecular simulation, conformational sampling | Analyze ligand-protein complex stability under physiological conditions [30] |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Spartan'14, Gaussian | DFT calculations, molecular orbital analysis, geometry optimization | Generate accurate 3D molecular structures and quantum chemical descriptors [28] |

| Benchmark Datasets | PharmaBench, MoleculeNet, Therapeutics Data Commons | Standardized data for model training and validation | Train and benchmark AI models on curated experimental data [16] |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit, PaDEL, Open Babel | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, file format conversion | Process chemical structures and calculate molecular features [27] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implementation of ML/DL algorithms, neural network architectures | Develop AI models for chemical property prediction [27] |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolution from QSAR to AI represents more than a technological advancement; it signifies a fundamental transformation in pharmacological research methodology. The integration of AI-powered approaches with traditional computational methods has created a new paradigm where predictive modeling serves as the foundation for drug discovery decision-making. As these technologies continue to mature, several emerging trends are poised to further reshape the landscape:

Hybrid AI-Quantum Frameworks: The convergence of artificial intelligence with quantum computing holds promise for tackling increasingly complex molecular simulations and chemical space explorations that exceed current computational capabilities [11].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining AI-powered pharmacological modeling with genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data will enable more comprehensive approaches to personalized medicine and targeted therapeutics [11] [27].

Large Language Models for Data Curation: The successful application of multi-agent LLM systems, as demonstrated in the creation of PharmaBench, highlights the potential for natural language processing to address critical data curation challenges and extract experimental conditions from scientific literature at scale [16].

Enhanced Explainability and Regulatory Acceptance: As interpretability methods like SHAP and LIME continue to evolve, AI models will become more transparent and trustworthy, facilitating their adoption in regulatory decision-making and clinical applications [27].

The pharmaceutical industry stands at the threshold of a new era, with AI projected to play a role in discovering 30% of new drugs by 2025 [26]. This transformation extends beyond scientific innovation to encompass institutional and cultural shifts as the industry adapts to AI-driven workflows. The companies leading this charge are those embracing the synergistic potential of biological sciences and algorithmic innovation, successfully integrating wet and dry laboratory experiments to accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics [31].

The integration of ADMET prediction into early-stage drug discovery represents one of the most significant advancements in modern pharmacology. By identifying potential pharmacokinetic and toxicity issues before substantial resources are invested, researchers can prioritize candidates with optimal efficacy and safety profiles, ultimately reducing late-stage attrition rates and improving the efficiency of the entire drug development pipeline. As AI technologies continue to evolve and overcome current challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, and generalizability, their impact on pharmaceutical research will only intensify, potentially transforming drug discovery from a high-risk venture to a more predictable, engineered process.

A Practical Guide to Modern AI and Machine Learning for ADMET Profiling

The process of drug discovery and development is a notoriously complex and costly endeavor, often spanning 10 to 15 years of rigorous research and testing [4]. Despite technological advances, pharmaceutical research and development continues to face substantial attrition rates, with approximately 90% of drug candidates failing between clinical trials and marketing authorization [32] [10]. A significant proportion of these failures—estimated at nearly 10% of all drug failures—stem from unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties and safety concerns, specifically related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles [12] [4]. These ADMET properties fundamentally govern a drug candidate's pharmacokinetics and safety profile, directly influencing bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and the likelihood of regulatory approval [10]. The early assessment and optimization of ADMET properties have therefore become paramount for mitigating the risk of late-stage failures and improving the overall efficiency of drug development pipelines [16].

In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool in the prediction of ADMET properties, offering new opportunities for early risk assessment and compound prioritization [4] [10]. The integration of ML technologies into pharmaceutical research has catalyzed the development of more efficient and automated tools that enhance the drug discovery process by providing predictive, data-driven decision support [10]. These computational approaches provide a fast and cost-effective means for drug discovery, allowing researchers to focus on candidates with better ADMET potential and reduce labor-intensive and time-consuming wet-lab experiments [16]. The movement toward "property-based drug design" represents a significant shift from traditional approaches that focused primarily on optimizing potency, introducing instead a more holistic approach based on the consideration of how fundamental molecular and physicochemical properties affect pharmaceutical, pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and safety properties [33]. This review systematically examines the machine learning arsenal—encompassing supervised, deep learning, and generative models—that is revolutionizing ADMET prediction in early-stage drug discovery research.

The Machine Learning Arsenal for ADMET Prediction

Supervised Learning Approaches

Supervised learning methods form the foundation of traditional ML applications in ADMET prediction. In this paradigm, models are trained using labeled data to make predictions about properties of new compounds based on input attributes such as chemical descriptors [4]. The standard methodology begins with obtaining a suitable dataset, often from publicly available repositories tailored for drug discovery, followed by crucial data preprocessing steps including cleaning, normalization, and feature selection to improve data quality and reduce irrelevant or redundant information [4].

Table 1: Key Supervised Learning Algorithms in ADMET Prediction

| Algorithm | Key Characteristics | Common ADMET Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Ensemble method using multiple decision trees | Caco-2 permeability, CYP inhibition, solubility | Robust to outliers, handles high-dimensional data well |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting framework with sequential tree building | Caco-2 permeability (shown to outperform comparable models) | Generally provides better predictions than comparable models [12] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Finds optimal hyperplane for separation in high-dimensional space | Classification of ADMET properties, toxicity endpoints | Effective for binary classification, performance depends on kernel selection |

| k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) | Instance-based learning using distance metrics | Metabolic stability prediction, property similarity assessment | Simple implementation, sensitive to irrelevant features |

Among supervised methods, tree-based algorithms like Random Forest and XGBoost have demonstrated particular effectiveness in ADMET modeling. In a comprehensive study evaluating Caco-2 permeability prediction, XGBoost generally provided better predictions than comparable models for test sets [12]. Similarly, ensemble methods, also known as multiple classifier systems based on the combination of individual models, have been applied to handle high-dimensionality issues and unbalanced datasets commonly encountered in ADMET data [32].

Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning approaches have gained significant traction in ADMET prediction due to their ability to automatically learn relevant features from raw molecular representations without extensive manual feature engineering. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as particularly powerful tools because they naturally represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [12] [10]. The Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) framework, implemented in packages like ChemProp, serves as a foundational approach for molecular property prediction that effectively captures nuanced molecular features [12].

The Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) architecture has demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in ADMET property prediction by representing molecules as graphs and applying graph convolutions to these explicit molecular representations [4]. Hybrid approaches such as CombinedNet employ a combination of Morgan fingerprints and molecular graphs, with the former providing information on substructure existence and the latter conveying connectivity knowledge [12]. These deep learning architectures significantly enhance prediction accuracy by learning task-specific features that transcend the limitations of traditional fixed-length fingerprint representations [4].