Target Validation Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development Success

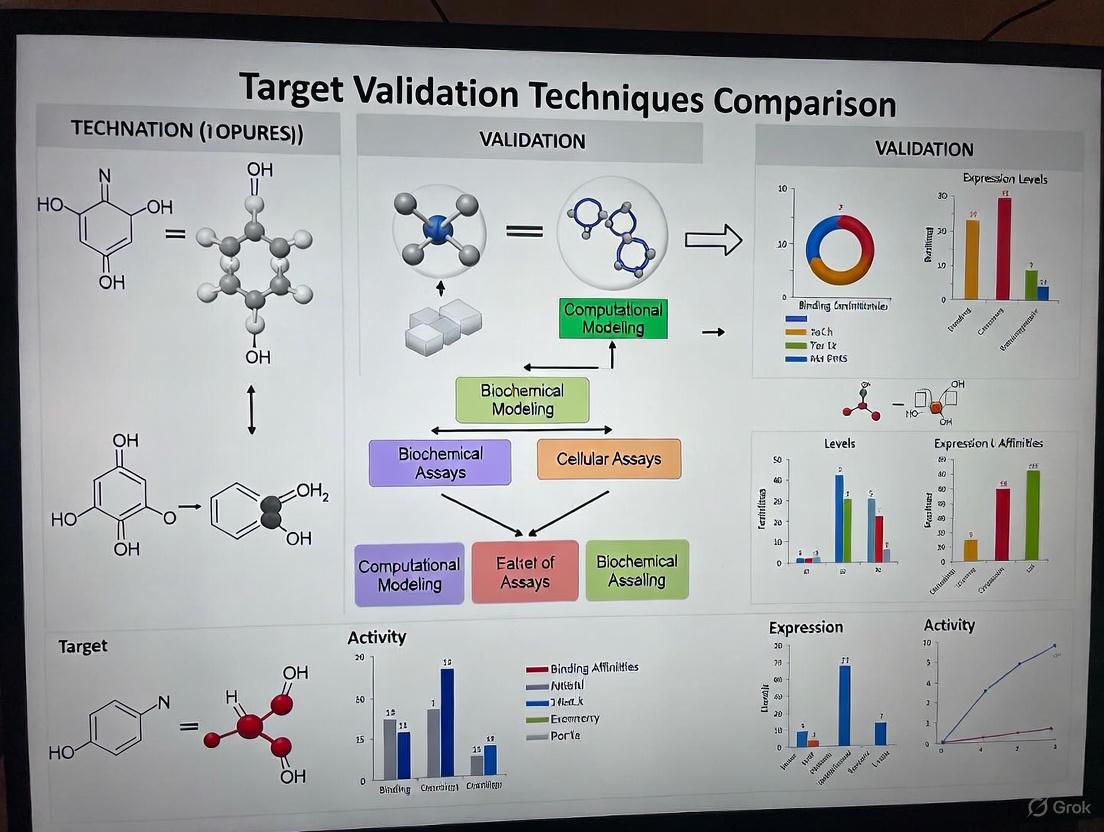

This article provides a detailed comparison of target validation techniques, a critical process in drug discovery that confirms a biological target's role in disease and its potential for therapeutic intervention.

Target Validation Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development Success

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of target validation techniques, a critical process in drug discovery that confirms a biological target's role in disease and its potential for therapeutic intervention. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts, key methodological approaches, common troubleshooting strategies, and a comparative analysis of techniques from RNAi to emerging AI-powered tools. The content synthesizes current best practices to help scientists build robust evidence for their targets, mitigate clinical failure risks, and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapies.

What is Target Validation and Why is it the Cornerstone of Drug Discovery?

Target validation is a critical, early-stage process in drug discovery that focuses on establishing a causal relationship between a biological target and a disease. It provides the foundational evidence that modulating a specific target (e.g., a protein, gene, or RNA) will produce a therapeutic effect with an acceptable safety profile [1]. This process typically takes 2-6 months to complete and is essential for de-risking drug development, as inadequate validation is a major contributor to the high failure rates seen in clinical trials, often due to lack of efficacy [1] [2]. This guide objectively compares the performance, experimental protocols, and data outputs of the primary techniques used to establish the functional role of a target in disease.

Core Methodologies in Target Validation

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, applications, and data outputs of the primary target validation methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Target Validation Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Application / Context | Typical Experimental Readout | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico Target Prediction [3] [4] | Uses AI/ML and similarity principles to predict drug-target interactions from chemical and biological data. | Prioritizing targets for novel compounds; generating MoA hypotheses; initial triage. | - Ranked list of potential targets.- Probability scores (e.g., pChEMBL value).- Similarity to known ligands. | - High speed; can screen thousands of targets.- Low resource consumption.- Reveals hidden polypharmacology. | - Predictive performance varies.- Relies on quality/completeness of existing data.- Requires experimental confirmation. |

| Functional Analysis (In Vitro) [1] | Uses "tool" molecules in cell-based assays to measure biological activity and the effect of target modulation. | Establishing a direct, causal link between target function and a cellular phenotype. | - Changes in cell viability, signaling, or reporter gene expression.- Quantification of biomarkers (qPCR, Luminex). | - Provides direct evidence of pharmacological effect.- Controlled, reductionist environment.- Amenable to high-throughput screening. | - May not capture full systemic physiology.- Can lack translational predictivity. |

| Genetic Approaches (In Vitro/In Vivo) [5] | Employs gene editing (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) to knock out or knock in a gene to study the consequent phenotype. | Establishing a causal link between a gene and a disease process in a biological system. | - Presence or absence of a disease-relevant phenotype (e.g., cell death, morphological defect).- Changes in biomarker expression. | - Provides strong causal evidence.- Highly versatile and precise.- Enables study of loss-of-function and gain-of-function. | - Potential for compensatory mechanisms.- Off-target effects of gene editing. |

| In Vivo Validation (Mammalian Models) [6] | Tests the therapeutic hypothesis in a living mammal, typically a mouse model with disease pathology. | Proof-of-concept studies to show disease modification in a complex, systemic organism. | - Improvement in disease symptoms/scores.- Protection of relevant cells (e.g., motor neurons).- Extension of survival. | - Captures full systemic physiology and PK/PD.- Highest preclinical translatability for human efficacy. | - Very high cost and time-intensive.- Low- to medium-throughput.- Ethical considerations. |

| In Vivo Validation (Zebrafish Models) [5] | Uses zebrafish, particularly CRISPR-generated F0 "crispants," for rapid functional gene assessment in a whole organism. | Rapidly narrowing down gene lists from GWAS; validating causal involvement in a living organism. | - Phenotypic outputs in systems like nervous or cardiovascular system (e.g., behavioral alterations, cardiac defects). | - High genetic and physiological similarity to humans.- Rapid results (within days).- Amenable to medium-throughput screening. | - Not a mammal; some physiological differences.- Less established for some complex diseases. |

| Target Engagement Assays (e.g., CETSA) [7] | Directly measures the physical binding of a drug molecule to its intended target in a physiologically relevant environment (e.g., intact cells). | Confirming that a drug candidate engages its target within the complex cellular milieu. | - Quantified, dose-dependent stabilization of the target protein.- Shift in protein melting temperature. | - Confirms mechanistic link between binding and phenotypic effect.- Provides quantitative, system-level validation. | - Does not, by itself, establish therapeutic effect. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Techniques

Protocol for In Silico Target Prediction and Validation

This protocol leverages computational tools like MolTarPred, which was identified as a highly effective method in a 2025 systematic comparison [3].

Step 1: Database Curation

- Retrieve bioactivity data from a structured database like ChEMBL (e.g., version 34) [3].

- Filter records for high-confidence interactions (e.g., confidence score ≥ 7) and standard values (IC50, Ki, EC50) below 10,000 nM [3].

- Exclude entries associated with non-specific or multi-protein targets and remove duplicate compound-target pairs.

Step 2: Model Application and Prediction

- Input the query molecule's structure (e.g., as a SMILES string).

- Run the target prediction algorithm (e.g., MolTarPred using Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores for optimal performance) [3].

- Generate a ranked list of potential targets based on similarity to known active ligands or other prediction metrics.

Step 3: Validation and Hypothesis Generation

- The top predictions, such as the potential repurposing of fenofibric acid as a THRB modulator for thyroid cancer, serve as testable hypotheses for experimental validation [3].

Protocol for Rapid In Vivo Validation Using Zebrafish

Zebrafish offer a powerful platform for rapid functional validation, especially when combined with CRISPR/Cas9 [5].

Step 1: Model Generation

- Design CRISPR/Cas9 guide RNAs targeting the candidate gene's zebrafish ortholog.

- Inject embryos to create F0 "crispant" models, which exhibit mosaic gene inactivation within days, bypassing the need for stable lines [5].

Step 2: Phenotypic Screening

- Screen the crispants for disease-relevant phenotypes using optimized injection and screening protocols to select embryos with a high mutational load [5].

- Assay phenotypes across different biological systems (e.g., behavioral assays for neuroscience, cardiac function monitoring for cardiovascular disease, or tumor development for oncology) [5].

Step 3: Data Analysis and Target Prioritization

- Correlate gene inactivation with the emergence of a phenotype to establish causal involvement. This approach serves as a functional filter to prioritize targets from large gene lists derived from sources like genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [5].

The workflow for this rapid in vivo validation is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol for In Vivo Proof-of-Concept in Mammalian Models

The In Vivo Target Validation Program by Target ALS exemplifies a robust protocol for testing therapeutic strategies in mammalian models of disease [6].

Step 1: Model and Therapeutic Selection

Step 2: In Vivo Dosing and Monitoring

- Administer the therapeutic compound to the model organism according to a defined dosing regimen.

- Monitor animals for disease symptoms and functional outcomes over time.

Step 3: Endpoint Analysis

- Assess primary efficacy endpoints, such as improvement in motor function, protection of vulnerable cells (e.g., motor neurons), and extension of survival [6].

- Conduct ex vivo analyses to confirm engagement of the intended target and understand the mechanism of action (e.g., reduction in TDP-43 phosphorylation) [6].

Quantitative Performance Metrics for Method Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of target validation methods, particularly computational ones, requires rigorous metrics. Standard n-fold cross-validation can produce over-optimistic results; therefore, more challenging validation schemes like time-splits or clustering compounds by scaffold are recommended for a realistic performance estimate [4]. The following table compares key metrics for assessing target prediction models, highlighting the limitations of generic metrics for the imbalanced datasets common in drug discovery.

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating Target Prediction Model Performance

| Metric | Calculation / Principle | Relevance to Target Validation | Limitations in Biopharma Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Predictions | Provides an overall measure of correct predictions. | Can be highly misleading with imbalanced datasets (e.g., many more inactive than active compounds), as simply predicting "inactive" for all will yield high accuracy [8]. |

| Precision | True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives) | Measures the reliability of a positive prediction. High precision reduces wasted resources on false leads [8]. | Does not account for false negatives, so a high-precision model might miss many true interactions [8]. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) | Measures the ability to find all true positives. High recall ensures promising targets are not missed [8]. | A high-recall model may generate many false positives, increasing the validation burden [8]. |

| F1 Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) | Balances precision and recall into a single metric. | May dilute focus on top-ranking predictions, which are most critical for lead prioritization [8]. |

| Precision-at-K | Precision calculated only for the top K ranked predictions. | Directly relevant for prioritizing the most promising drug candidates or targets from a screened list [8]. | Does not evaluate the performance of the model beyond the top K results. |

| Rare Event Sensitivity | A metric tailored to detect low-frequency events (e.g., specific toxicities). | Critical for identifying rare but critical events, such as adverse drug reactions or activity against rare target classes [8]. | Requires specialized dataset construction and is not a standard metric. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimental validation relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used across the featured methodologies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Validation | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise gene knockout or knock-in to study gene function and create disease models. | Generating F0 zebrafish "crispants" for rapid gene validation [5]. |

| Tool Molecules (e.g., selective agonists/antagonists) | To pharmacologically modulate a target's activity in a functional assay. | Demonstrating the desired biological effect in vitro during functional analysis [1]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | To confirm direct binding of a drug to its protein target in a physiologically relevant cellular context. | Quantifying target engagement of a compound, such as for DPP9 in rat tissue [7]. |

| Validated Antibodies | To detect and quantify protein expression, localization, and post-translational modifications. | Assessing expression profiles and biomarker changes in healthy vs. diseased states [1]. |

| qPCR Assays & Panels | To accurately measure mRNA expression levels of targets and biomarkers. | Biomarker identification and validation via transcriptomics [1]. |

| iPSCs (Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells) | To create disease-relevant human cell types (e.g., neurons) for physiologically accurate in vitro testing. | Using human stem cell-derived models in functional cell-based assays [1]. |

| ChEMBL Database | A curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-target interactions to train and benchmark predictive models. | Providing the reference dataset for ligand-centric target prediction methods like MolTarPred [3]. |

Target validation is not a one-size-fits-all process but a multi-faceted endeavor requiring a strategic combination of techniques. Computational methods like MolTarPred offer high-speed prioritization, while cellular assays establish pharmacological proof-of-concept. In vivo models, from the rapid zebrafish to the physiologically complex mouse, provide critical evidence of efficacy in a whole organism. The emerging trend is the integration of these approaches into cross-disciplinary pipelines, augmented by AI and functional validation tools like CETSA, to build an irrefutable case for a target's role in disease before committing to the costly later stages of drug development [6] [7]. This rigorous, multi-technique comparison empowers researchers to select the optimal validation strategy, thereby increasing the likelihood of clinical success.

Clinical trials are the cornerstone of drug development, yet approximately 90% fail to achieve regulatory approval [9]. A significant portion of these failures, particularly in early phases, can be traced back to a single, fundamental problem: inadequate target validation. When the underlying biology of a drug target is not thoroughly understood and validated, clinical trials are built on a fragile foundation, leading to costly late-stage failures. This analysis compares contemporary target validation techniques, highlighting how rigorous, multi-faceted validation strategies are critical for de-risking the drug development pipeline and reducing the staggering rate of clinical trial attrition.

The Staggering Cost of Clinical Trial Failure

Failed clinical trials represent one of the most significant financial drains in the biopharmaceutical industry. The average cost of a failed Phase III trial alone can exceed $100 million [9]. Beyond the financial loss, these failures delay life-saving treatments and raise ethical concerns regarding participant exposure without therapeutic benefit. An analysis of failure reasons reveals that a substantial number of programs collapse because the selected target is poorly understood or turns out to be less relevant in humans than in preclinical models [9]. This underscores that the failure often begins not during the trial's execution, but much earlier, during the drug discovery and design phases.

A Comparative Analysis of Target Validation Techniques

A robust validation strategy employs a combination of computational and experimental methods to build confidence in a target's role in disease. The table below summarizes the core methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Target Validation Techniques

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Principle | Key Output/Readout | Relative Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Prediction | In-silico Target Fishing [3] | Ligand-based similarity searching against known bioactive molecules | Ranked list of potential protein targets | Low | Dependent on quality and scope of underlying database |

| AI/ML Models (e.g., CMTNN, RF-QSAR) [3] | Machine learning trained on chemogenomic data to predict drug-target interactions | Target interaction probability scores | Low to Medium | Model accuracy depends on training data; "black box" concern | |

| Genetic Manipulation | Antisense Oligonucleotides [10] | Chemically modified oligonucleotides bind mRNA, blocking protein synthesis | Measurement of target protein reduction and phenotypic effect | Medium | Toxicity and bioavailability issues; non-specific actions |

| Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) [10] | Double-stranded RNA activates cellular machinery to degrade specific mRNA | Measurement of target protein reduction and phenotypic effect | Medium | Challenges with in vivo delivery and potential off-target effects | |

| Transgenic Animals (Knockout/Knock-in) [10] | Generation of animals lacking or with an altered target gene | Observation of phenotypic endpoints in a whole organism | Very High | Expensive, time-consuming; potential for compensatory mechanisms | |

| Pharmacological Modulation | Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) [10] | High-specificity binding to extracellular targets to modulate function | In vivo efficacy and safety profiling | High | Generally restricted to cell surface and secreted proteins |

| Tool Compounds/Chemical Genomics [10] | Use of small bioactive molecules to modulate target protein function | Demonstration of phenotypic change with pharmacological intervention | Medium | Difficulty in finding highly specific tool compounds | |

| Direct Binding Assessment | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [7] | Measure of target protein thermal stability shift upon ligand binding in cells | Quantitative confirmation of direct target engagement in a physiologically relevant context | Medium | Requires specific reagents and instrumentation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Methods

To ensure reproducibility and informed selection, detailed protocols for three critical techniques are outlined below.

Protocol: In-silico Target Prediction with MolTarPred

MolTarPred is a ligand-centric method identified as one of the most effective for predicting molecular targets [3].

- Objective: To identify potential protein targets for a query small molecule based on structural similarity to known ligands.

- Database Setup: A validated database of ligand-target interactions, such as ChEMBL 34, is hosted locally. This database contains over 2.4 million compounds and 2.1 million interactions [3].

- Fingerprint Calculation: The canonical SMILES of both the query molecule and all database molecules are converted into molecular fingerprints. The Morgan fingerprint (radius 2, 2048 bits) has been shown to outperform others like MACCS [3].

- Similarity Searching: The Tanimoto similarity coefficient is calculated between the query molecule's fingerprint and every molecule in the database.

- Hit Identification: Database molecules are ranked by similarity score. The top 1, 5, 10, or 15 most similar ligands are selected, and their annotated targets are retrieved as the predicted targets for the query molecule [3].

Protocol: Target Engagement Validation with CETSA

CETSA bridges the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy by confirming direct binding in physiologically relevant environments [7].

- Objective: To provide quantitative, system-level validation of direct drug-target engagement in intact cells or tissues.

- Cell Treatment: Live cells or tissue samples are treated with the compound of interest or a vehicle control (DMSO) across a range of concentrations and for specified time periods.

- Heat Challenge: Aliquots of the treated cell suspension are heated to different temperatures (e.g., from 45°C to 65°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 3 minutes) in a thermal cycler.

- Cell Lysis & Soluble Protein Extraction: Heated samples are subjected to freeze-thaw cycles or chemical lysis to break open the cells. The soluble protein fraction is separated from insoluble aggregates by high-speed centrifugation.

- Target Protein Quantification: The amount of soluble, non-aggregated target protein in each sample is quantified. This is typically done via immunoblotting (Western blot) or, for higher throughput and precision, high-resolution mass spectrometry [7].

- Data Analysis: The melting curve of the target protein (amount of soluble protein vs. temperature) is plotted for both compound-treated and vehicle-treated samples. A rightward shift in the melting curve (increased thermal stability) in the compound-treated samples confirms direct target engagement.

Protocol: Phenotypic Validation with siRNA

siRNA provides a reversible means of validating target function by selectively reducing its expression [10].

- Objective: To silence a specific target gene and observe the resulting phenotypic consequences in a cellular model of disease.

- siRNA Design: Commercially available or custom-designed double-stranded siRNAs (21-25 base pairs) targeting specific mRNA sequences of the gene of interest are acquired. A non-targeting (scrambled) siRNA must be used as a negative control.

- Cell Culture & Transfection: Relevant cell lines are cultured under standard conditions. The siRNA is introduced into the cells using a transfection reagent (e.g., lipofectamine), optimizing the reagent:siRNA ratio for maximum efficiency and minimal toxicity.

- Validation of Knockdown: 48-72 hours post-transfection, the efficiency of gene knockdown is confirmed. This is typically done by measuring a reduction in target mRNA levels using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and/or a reduction in target protein levels using immunoblotting.

- Phenotypic Assay: Cells with confirmed knockdown are subjected to disease-relevant phenotypic assays. These could include proliferation assays (for oncology), migration assays, or measurements of specific biochemical outputs. The phenotype of siRNA-treated cells is compared to cells treated with the non-targeting control siRNA.

Visualizing the Link Between Validation and Attrition

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in the drug discovery pipeline where rigorous target validation acts as a filter to prevent costly clinical trial failures.

Diagram: The Target Validation Funnel. Each validation stage filters out targets with poor translatability, preventing their progression to costly clinical trials where attrition is high. Bypassing or performing weak validation at any stage (red arrows) significantly increases the risk of failure [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

A successful validation campaign relies on a suite of high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function in Validation | Key Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Detection and quantification of target protein levels (e.g., via Western blot) after genetic or pharmacological perturbation. | Specificity (monoclonal vs. polyclonal), application validation (e.g., ICC, IHC, WB), and species reactivity. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Selective knockdown of target gene expression to study consequent phenotypic changes in cellular models. | On-target efficiency and validated minimal off-target effects; use of pooled vs. arrayed formats. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Complete knockout of the target gene in cell lines to establish its necessity for a phenotype. | Efficiency of delivery (lentivirus, electroporation) and need for single-cell clone validation. |

| Tool Compounds | Pharmacological modulation of the target protein to establish a causal link between target function and phenotype. | High specificity and potency; careful matching of mechanism of action (agonist, antagonist, etc.) to the biological question. |

| Bioactive Compound Libraries | Used in chemical genomics to probe cellular function and identify novel targets through phenotypic screening. | Library diversity, chemical tractability, and availability of structural information. |

| ChEMBL / Public Databases | Provide a vast repository of known ligand-target interactions for in-silico target prediction and model training. | Data confidence scores, size of the database, and frequency of updates [3]. |

| AI-Powered Discovery Platforms | Accelerate data mining and hypothesis generation by uncovering hidden relationships between targets, diseases, and drugs from literature. | Ability to synthesize evidence from multiple sources and provide transparent citation of supporting data [11]. |

The high failure rate of clinical trials is a systemic challenge, but a significant portion of it is addressable through rigorous, front-loaded target validation. As the comparison of techniques demonstrates, no single method is sufficient; confidence is built through a convergence of evidence from computational, genetic, and pharmacological approaches. The integration of modern tools like AI for predictive analysis and CETSA for direct binding confirmation in cells provides an unprecedented ability to de-risk drug candidates before they enter the clinical phase. For researchers and drug developers, investing in a comprehensive, multi-faceted validation strategy is not merely a scientific best practice—it is a critical financial and ethical imperative to overcome the high cost of clinical trial failure.

The process of validating a drug target is a critical foundation upon which successful drug discovery and development is built. This initial phase determines whether a hypothesized biological target, typically a protein, is genuinely involved in a disease pathway and can be safely and effectively modulated by a therapeutic agent. The high failure rates in clinical development, often exceeding 90%, are frequently attributed to inadequate target validation, highlighting the crucial importance of this preliminary stage [12] [13]. The ideal drug target must satisfy three fundamental properties: demonstrated druggability (the ability to bind to drug-like molecules with high affinity), established safety (modulation does not produce unacceptable adverse effects), and clear disease-modifying potential (intervention alters the underlying disease pathology) [13].

Target validation has evolved significantly from traditional methods to incorporate sophisticated multi-omics approaches and artificial intelligence. The Open Targets initiative exemplifies this modern approach, systematically integrating evidence from human genetics, perturbation studies, transcriptomics, and proteomics to generate and prioritize therapeutic hypotheses [13]. This comprehensive evidence-gathering is essential for mitigating the substantial risks inherent in drug development, where the average cost exceeds $2 billion per approved therapy and the timeline spans 10-15 years [14] [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary target validation techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols, to equip researchers with practical frameworks for assessing the core properties of promising drug targets.

Core Properties of an Ideal Drug Target

Druggability: Structural and Functional Considerations

Druggability refers to the likelihood that a target can bind to a drug-like molecule with sufficient affinity and specificity to produce a therapeutic effect. This property is fundamentally determined by the target's structural characteristics, including the presence of suitable binding pockets, and its biochemical function.

Structural Druggability: The presence of well-defined binding pockets is a primary determinant of structural druggability. For instance, the discovery of cryptic allosteric pockets in mutant KRAS (G12C), once considered undruggable, enabled the development of covalent inhibitors like sotorasib and adagrasib [13]. Modern computational approaches have dramatically advanced structural assessment. AlphaFold2-generated protein structures have demonstrated remarkable utility in molecular docking for protein-protein interactions (PPIs), performing comparably to experimentally solved structures in virtual screening protocols [15]. As shown in Table 1, specific benchmarking against 16 PPI targets revealed that high-quality AlphaFold2 models (interface pTM + pTM > 0.7) achieved docking performance metrics similar to native structures, validating their use when experimental structures are unavailable [15].

Functional Druggability: Beyond structure, functional druggability considers the target's role in cellular pathways and the feasibility of modulating its activity. As Michelle Arkin notes, researchers may pursue multiple mechanistic hypotheses for the same target: "I want to inhibit the expression of the transcription factor; speed the degradation of this transcription factor; block the transcription factor binding to certain proteins it interacts with; stop its binding to DNA; stop the transcription of some of its downstream targets that I think are bad" [13]. Each approach represents a distinct druggability hypothesis with different implications for modality selection.

Table 1: Benchmarking AlphaFold2 Models for Druggability Assessment in Protein-Protein Interactions

| Metric | Performance in PPI Docking | Implication for Druggability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Model Quality (ipTM+pTM) | >0.7 (high-quality) for most complexes [15] | Suitable for initial binding site identification |

| TM-score | Median: 0.972 vs. experimental structures [15] | Accurate backbone prediction for binding pocket analysis |

| DockQ Score | Median: 0.838; 9/16 complexes high-quality (DockQ > 0.8) [15] | Reliable complex structure for interface targeting |

| Docking Performance | Comparable to native structures in virtual screening [15] | Validated use in absence of experimental structures |

| MD Refinement Impact | Improved outcomes in selected cases; significant variability [15] | Ensemble docking may enhance hit identification |

Safety: Therapeutic Index and Genetic Validation

Safety considerations for a drug target extend beyond compound-specific toxicities to include inherent risks associated with modulating the target itself. Ideal targets should offer a wide therapeutic index, where efficacy is achieved well below doses that cause mechanism-based adverse effects.

Genetic Evidence for Safety: Human genetics provides powerful insights into target safety profiles. As David Ochoa explains, "The more you understand about the problem, the less risks you have" [13]. Targets with human loss-of-function variants that are not associated with serious health consequences often represent safer intervention points. The presence of a target in essential biological processes or its expression in critical tissues may raise safety concerns that require careful evaluation during target selection [13].

Predictive Toxicology: Advanced computational models are increasingly employed to predict safety liabilities early in the validation process. Large language models (LLMs) and specialized AI tools can predict drug efficacy and safety profiles by analyzing historical data and chemical structures [14]. For example, the FP-ADMET and MapLight frameworks combine molecular fingerprints with machine learning models to establish robust prediction frameworks for a wide range of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties, enabling earlier identification of potential safety issues [16].

Disease-Modifying Potential: Biomarkers and Clinical Translation

The ultimate validation of a target's disease-modifying potential requires demonstration that its modulation alters the underlying disease pathology and produces clinically meaningful benefits. This requires establishing a clear causal relationship between target activity and disease progression.

Biomarker Development: Biomarkers serve as essential tools for establishing disease-modifying potential throughout the drug development pipeline. In Alzheimer's disease, for example, the recent FDA approval of the Lumipulse G blood test measuring plasma pTau217/Aβ1-42 ratio provides a less invasive method for diagnosing cerebral amyloid plaques in symptomatic patients [17]. The 2018 and 2024 NIA-AA diagnostic criteria recognize multiple categories of biomarkers, including diagnostic, monitoring, prognostic, predictive, pharmacodynamic response, safety, and susceptibility biomarkers [17]. As shown in recent Alzheimer's trials, biomarker changes can provide early evidence of disease-modifying effects. Treatment with buntanetap reduced levels of neurofilament light (NfL), a protein fragment released from damaged neurons, indicating improved cellular integrity and neuronal health [18].

Clinical Endpoint Correlation: For a target to demonstrate genuine disease-modifying potential, its modulation must ultimately translate to improved clinical outcomes. In Huntington's disease research, the AMT-130 gene therapy reportedly showed approximately 75% slowing of disease progression based on the cUHDRS, a comprehensive clinical metric [19]. Similarly, Alzheimer's disease-modifying therapies lecanemab and donanemab showed 25% and 22.3% slowing of cognitive decline, respectively, in phase 3 trials, though these modest benefits highlight the challenges in achieving robust disease modification [17].

Table 2: Biomarker Classes for Establishing Disease-Modifying Potential

| Biomarker Category | Role in Target Validation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Identify disease presence and involvement of specific targets [17] | Plasma pTau217/Aβ1-42 ratio for amyloid plaques [17] |

| Pharmacodynamic | Demonstrate target engagement and biological activity [17] | Reduction in IL-6, S100A12, IFN-γ, IGF1R with buntanetap [18] |

| Prognostic | Identify disease trajectory and treatment-responsive populations [17] | Neurofilament light (NfL) for neuronal damage [18] |

| Monitoring | Track treatment response and disease progression [17] | EEG changes in pre-symptomatic Huntington's disease [19] |

| Predictive | Identify patients most likely to respond to specific interventions [17] | APOE4 homozygosity status for ARIA risk with anti-amyloid antibodies [17] |

Comparative Analysis of Target Validation Techniques

Computational and AI-Driven Approaches

Artificial intelligence, particularly large language models, has introduced transformative capabilities for target validation. LLMs can process vast scientific literature and complex biomedical data to uncover target-disease linkages, predict drug-target interactions, and identify novel target opportunities [14]. Two distinct paradigms have emerged for applying LLMs in drug discovery:

Specialized Language Models: These models are trained on domain-specific scientific language, such as SMILES for small molecules and FASTA for proteins and polynucleotides. They learn statistical patterns from raw biochemical and genomic data to perform specialized tasks including predicting protein-ligand binding affinities when provided with a ligand's SMILES string and a protein's amino acid sequence [14].

General-Purpose Language Models: Pretrained on diverse text collections including scientific literature, these models possess capabilities such as reasoning, planning, tool use, and information retrieval. Researchers interact with these models as conversational assistants to solve specific problems in target validation [14].

The maturity of these approaches varies across different stages of target validation. For understanding disease mechanisms, specialized LLMs have reached "advanced" maturity (demonstrated efficacy in laboratory studies), while general LLMs remain at "nascent" stage (primarily investigated in silico) [14]. The optSAE + HSAPSO framework exemplifies advanced computational approaches, integrating stacked autoencoders with hierarchically self-adaptive particle swarm optimization to achieve 95.52% accuracy in drug classification and target identification tasks on DrugBank and Swiss-Prot datasets [12].

Experimental and Biochemical Methods

While computational approaches provide valuable initial insights, experimental validation remains essential for confirming a target's therapeutic potential. Several established methodologies provide critical evidence for druggability, safety, and disease-modifying potential.

Cellular and Molecular Profiling: Modern molecular representation methods have significantly advanced experimental target validation. AI-driven strategies such as graph neural networks, variational autoencoders, and transformers extend beyond traditional structural data, facilitating exploration of broader chemical spaces [16]. These approaches enable more effective characterization of the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity, which is crucial for assessing a target's druggability.

Biomarker Validation: As previously discussed, biomarkers provide critical evidence for a target's disease-modifying potential. The reduction of inflammatory markers (IL-5, IL-6, S100A12, IFN-γ, IGF1R) and neurofilament light chain in response to buntanetap treatment in Alzheimer's patients exemplifies how biomarker changes can demonstrate target engagement and biological effects [18]. Such pharmacodynamic biomarkers are increasingly incorporated into early-phase trials to provide proof-of-concept for a target's role in disease pathogenesis.

Structural Biology Techniques: Experimental methods for determining protein structure, such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy, provide the gold standard for assessing structural druggability. When experimental structures are unavailable, AlphaFold2 models have proven valuable alternatives, particularly for protein-protein interactions. Benchmarking studies reveal that local docking strategies using TankBind_local and Glide provided the best results across different structural types, with performance similar between native and AF2 models [15].

Integrated Workflow for Target Validation

The most effective target validation strategies combine computational and experimental approaches in a sequential workflow. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive framework for evaluating druggability, safety, and disease-modifying potential:

Diagram Title: Integrated Target Validation Workflow

This integrated approach ensures comprehensive evaluation across all three critical properties. As emphasized throughout this guide, successful target validation requires evidence from multiple complementary methods rather than reliance on a single technique.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Advancing a target through validation requires specialized research tools and platforms. The following table details key solutions used in contemporary target validation studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application in Target Validation |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 Models | Protein structure prediction [15] | Druggability assessment when experimental structures unavailable [15] |

| Molecular Docking Platforms (Glide, TankBind) | Binding pose and affinity prediction [15] | Virtual screening for initial hit identification [15] |

| LLM-Based Target-Disease Linkage Tools (Geneformer) | Disease mechanism understanding [14] | Identifying therapeutic targets through in silico perturbation [14] |

| Biomarker Assay Platforms (Lumipulse G) | Target engagement measurement [17] | Quantifying pharmacodynamic response in clinical trials [17] [18] |

| AI-Driven Molecular Representation (GNNs, VAEs, Transformers) | Chemical space exploration [16] | Scaffold hopping and lead compound optimization [16] |

| Automated Drug Design Frameworks (optSAE+HSAPSO) | Drug classification and target identification [12] | High-accuracy prediction of drug-target relationships [12] |

These tools represent the current state-of-the-art in target validation methodology. Their integrated application enables researchers to systematically evaluate the three fundamental properties of an ideal drug target before committing substantial resources to clinical development.

The validation of drug targets with ideal properties—demonstrated druggability, established safety, and clear disease-modifying potential—remains a complex but essential process in therapeutic development. As this comparison guide illustrates, successful validation requires integrating multiple lines of evidence from computational predictions, experimental data, and clinical observations. The emergence of sophisticated AI tools, particularly large language models and advanced molecular representation methods, has enhanced our ability to assess these properties earlier in the discovery process [14] [16]. However, these computational approaches complement rather than replace rigorous experimental validation.

The modest clinical benefits observed with recently approved disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer's disease highlight the challenges in translating target validation to patient outcomes [17]. These experiences underscore the importance of continued refinement in validation methodologies, including the development of more predictive biomarkers and improved understanding of disease heterogeneity. As the field advances, the integration of multi-omics data, AI-driven analytics, and human clinical evidence will provide increasingly robust frameworks for identifying targets with genuine potential to address unmet medical needs safely and effectively.

In the intricate journey of drug discovery, target identification and target validation represent two fundamentally distinct yet deeply interconnected phases. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this critical distinction is not merely academic—it is essential for de-risking development pipelines and avoiding costly late-stage failures. Target identification encompasses the process of discovering biological molecules (proteins, genes, RNA) that play a key role in disease pathology. In contrast, target validation is the rigorous process of confirming that modulating the identified target will produce a meaningful therapeutic effect [20].

The distinction matters profoundly because many drug programs fail not due to compound inefficacy, but because the biological target itself was flawed—being non-essential, redundant, or insufficiently disease-modifying [20]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these critical processes, examining their methodologies, experimental protocols, and technological frameworks within the broader context of target validation techniques research.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

At its essence, target identification is a discovery process, while target validation is a confirmation process. Target identification aims to pinpoint a "druggable" biological molecule that can be modulated—inhibited, activated, or altered—to produce a therapeutic effect. The output is typically a list of potential targets with established disease relevance and druggability [20].

Target validation, however, asks a more definitive question: Does modulating this target actually produce the desired therapeutic effect in a biologically relevant system? This phase focuses on establishing causal relationships between target modulation and disease phenotype, providing critical evidence for go/no-go decisions in the drug development pipeline [20].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Target Identification and Validation

| Aspect | Target Identification | Target Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Discover disease-relevant biological targets | Confirm therapeutic relevance of identified targets |

| Key Question | "What target should we pursue?" | "Does this target actually work as expected?" |

| Output | List of potential targets with disease relevance | Evidence of causal relationship between target and disease |

| Stage in Pipeline | Early discovery | Late discovery/early preclinical |

| Risk Mitigation | Identifies potential targets | Reduces attrition by validating target biology |

Methodological Comparison: Techniques and Technologies

Target Identification Methodologies

Modern target identification employs increasingly sophisticated technologies ranging from classical biochemical approaches to cutting-edge computational methods. Affinity purification, a cornerstone technique, operates on the principle of specific physical interactions between ligands and their targets. This "target fishing" approach uses immobilized compound bait to capture functional proteins from cell or tissue lysates for identification, typically via mass spectrometry [21] [22].

Advanced methods include photoaffinity labeling (PAL), which incorporates photoreactive moieties that form covalent bonds with target proteins upon light exposure, enabling the identification of even transient interactions [21] [22]. Click chemistry approaches utilize bioorthogonal reactions to label and identify target proteins within complex biological systems [21].

Computational approaches represent a paradigm shift in target identification. Artificial intelligence platforms now leverage knowledge graphs integrating trillions of data points from multi-omics datasets, scientific literature, and clinical databases. For instance, the PandaOmics platform analyzes over 1.9 trillion data points from more than 10 million biological samples to identify novel therapeutic targets [23]. Deep learning models can predict drug-target interactions with accuracies exceeding 95% in some implementations [12].

Target Validation Techniques

Target validation employs functional assays to establish causal relationships. CRISPR/Cas9 and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies enable targeted gene knockout or knockdown to observe resulting phenotypic changes [20]. Small-molecule inhibitor or activator assays test whether pharmacological modulation produces the expected therapeutic effects [20].

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a powerful label-free method for validating target engagement in physiologically relevant contexts. CETSA detects changes in protein thermal stability induced by ligand binding, providing direct evidence of compound-target interactions within intact cells and tissues [7]. Recent advances have coupled CETSA with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantify drug-target engagement ex vivo and in vivo, confirming dose-dependent stabilization of targets like DPP9 in rat tissue [7].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Key Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Technical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification | Target identification | Direct physical interaction capture; works with native proteins | Requires compound modification; may miss weak/transient interactions |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) | Target identification | Captures transient interactions; suitable for membrane proteins | Complex probe design; potential for non-specific labeling |

| AI/Knowledge Graphs | Target identification | Holistic biology perspective; integrates multimodal data | Dependent on data quality; "black box" interpretability challenges |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Target validation | Precise genetic manipulation; establishes causal relationships | Off-target effects; may not reflect pharmacological modulation |

| CETSA | Target validation | Confirms binding in intact cells; no labeling required | Limited to interactions that alter thermal stability |

Experimental Protocols: Key Workflows

Affinity-Based Pull-Down Assay for Target Identification

The affinity purification protocol begins with chemical probe design, where the compound of interest is modified with a functional handle (e.g., biotin, alkyne/azide for click chemistry) while preserving its biological activity [21] [22]. The modified compound is then immobilized on a solid support (e.g., streptavidin beads for biotinylated probes).

Cell lysates are prepared under non-denaturing conditions to preserve native protein structures and interactions. The lysate is incubated with the compound-immobilized beads to allow specific binding between the target proteins and the compound bait. After extensive washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins, the specifically bound proteins are eluted and identified using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [22].

Data analysis involves comparing the identified proteins against appropriate controls (e.g., beads with immobilized compound versus blank beads or beads with an inactive analog) to distinguish specific binders from non-specific interactions.

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) for Target Validation

The CETSA protocol begins by treating intact cells or cell lysates with the compound of interest or vehicle control across a range of concentrations. Following compound treatment, the samples are divided into aliquots and heated to different temperatures (typically spanning 37-65°C) for a fixed duration (e.g., 3 minutes) [7].

The heated samples are then cooled, and soluble proteins are separated from aggregated proteins by centrifugation or filtration. The remaining soluble target protein in each sample is quantified using immunoblotting, enzyme activity assays, or mass spectrometry. The resulting melting curves, plotting protein abundance against temperature, are compared between compound-treated and control samples [7].

A rightward shift in the melting curve (increased thermal stability) in compound-treated samples indicates direct binding and stabilization of the target protein. This shift can be quantified to determine the temperature at which 50% of the protein is denatured (Tm), providing a robust measure of target engagement.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Sequential Relationship in Drug Discovery

Affinity Purification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Target Identification and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin/Azide Handles | Enable compound immobilization or click chemistry conjugation | Affinity purification probes; photoaffinity labeling |

| Streptavidin Beads | Solid support for immobilizing biotinylated compound baits | Affinity pull-down assays |

| Photoactivatable Groups | (e.g., diazirines, aryl azides) form covalent bonds upon UV exposure | Photoaffinity labeling probes |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precise gene editing for functional gene knockout | Target validation via genetic perturbation |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Gene silencing through RNA interference | High-throughput target validation screening |

| CETSA Reagents | Buffer systems, detection antibodies, thermal cyclers | Cellular thermal shift assays for target engagement |

| Activity-Based Probes | Covalently label active sites of enzyme families | Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) |

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The landscape of target identification and validation is being transformed by artificial intelligence and novel chemical biology approaches. AI platforms now leverage multi-modal data integration, combining chemical, omics, text, and image data to construct comprehensive biological representations [23]. Generative AI models are being used not only for target identification but also for designing novel molecular entities optimized for binding affinity and metabolic stability [23] [24].

Label-free target deconvolution methods are gaining prominence, with techniques like solvent-induced denaturation shift assays enabling the study of compound-protein interactions under native conditions without chemical modifications that might disrupt biological activity [22]. These approaches are particularly valuable for identifying the targets of natural products, which often possess complex structures that challenge conventional modification strategies [21].

Integrated platforms that combine target identification and validation in seamless workflows represent the future of early drug discovery. Companies like Recursion and Verge Genomics have developed closed-loop systems where computational predictions are experimentally validated in-house, creating continuous feedback that refines both biological hypotheses and model performance [23]. As these technologies mature, the distinction between target identification and validation may blur, ultimately accelerating the translation of biological insights into therapeutic breakthroughs.

In modern drug development, establishing a therapeutic window—the dose range between efficacy and toxicity—is paramount for delivering safe medicines. A compound's safety profile is profoundly influenced by its interaction with both intended and off-target proteins, a concept known as polypharmacology [3]. While off-target effects can cause adverse reactions, they also present opportunities for drug repurposing, as exemplified by drugs like Gleevec and Viagra [3]. Consequently, accurately predicting drug-target interactions during early discovery phases is crucial for hypothesizing a molecule's eventual therapeutic window.

This guide objectively compares the performance of leading computational target prediction methods, which have become indispensable for initial target identification and validation. By enabling more precise identification of a compound's primary targets and potential off-targets, these in silico methods help researchers prioritize molecules with a higher probability of success, thereby de-risking the long and costly journey toward establishing a clinical therapeutic window [25].

Performance Comparison of Target Prediction Methods

A precise comparative study published in 2025 systematically evaluated seven stand-alone codes and web servers using a shared benchmark of FDA-approved drugs [3]. The performance was measured using Recall, which indicates the method's ability to identify all known targets for a drug, and Precision, which reflects the accuracy of its predictions. High recall is particularly valuable for drug repurposing, as it minimizes missed opportunities, while high precision provides greater confidence for downstream experimental validation [3].

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and characteristics of the evaluated methods.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Target Prediction Method Performance and Characteristics

| Method Name | Type | Core Algorithm | Key Database Source | Recall (Top 1) | Precision (Top 1) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolTarPred [3] | Ligand-centric | 2D Similarity | ChEMBL 20 | 0.410 | 0.310 | Most effective overall; Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto score recommended. |

| PPB2 [3] | Ligand-centric | Nearest Neighbor/Naïve Bayes/Deep Neural Network | ChEMBL 22 | 0.250 | 0.160 | - |

| RF-QSAR [3] | Target-centric | Random Forest | ChEMBL 20 & 21 | 0.230 | 0.160 | - |

| TargetNet [3] | Target-centric | Naïve Bayes | BindingDB | 0.210 | 0.130 | - |

| ChEMBL [3] | Target-centric | Random Forest | ChEMBL 24 | 0.200 | 0.130 | - |

| CMTNN [3] | Target-centric | ONNX Runtime | ChEMBL 34 | 0.190 | 0.120 | - |

| SuperPred [3] | Ligand-centric | 2D/Fragment/3D Similarity | ChEMBL & BindingDB | 0.180 | 0.110 | - |

Key Performance Insights

- Performance Trade-offs: The data reveals a clear performance gap, with MolTarPred significantly outperforming other methods in both recall and precision [3]. This makes it a superior choice for applications where maximizing the identification of true targets is critical.

- Ligand-centric vs. Target-centric: On average, ligand-centric methods (MolTarPred, PPB2) in this evaluation demonstrated higher recall than target-centric approaches (RF-QSAR, TargetNet). Ligand-centric methods predict targets based on the similarity of a query molecule to known active ligands, while target-centric methods use predictive models built for specific targets [3].

- Impact of High-Confidence Filtering: Applying a high-confidence filter (e.g., using only interactions with a ChEMBL confidence score ≥ 7) improves precision but at the cost of reduced recall. This makes such filtering less ideal for exploratory drug repurposing projects where the goal is to uncover all possible opportunities [3].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

To ensure a fair and unbiased comparison, the evaluation of the seven target prediction methods followed a rigorous and standardized experimental protocol [3].

Database Preparation and Curation

- Data Source: The ChEMBL database (version 34) was used as the primary source of bioactivity data. It contained over 2.4 million compounds and 20.7 million interactions against 15,598 targets at the time of the study [3].

- Data Filtering:

- Bioactivity records were selected based on standard values (IC50, Ki, or EC50) below 10,000 nM.

- Entries associated with non-specific or multi-protein targets were excluded.

- Duplicate compound-target pairs were removed, resulting in 1,150,487 unique ligand-target interactions for the main database [3].

- Benchmark Dataset: A separate benchmark dataset was created from 100 randomly selected FDA-approved drugs. Critically, these molecules were excluded from the main database to prevent any overlap and avoid over-optimistic performance estimates during prediction [3].

Prediction and Validation Methodology

- Method Execution: The seven methods were run against the prepared database. MolTarPred and CMTNN were executed locally using stand-alone codes, while the others were accessed via their respective web servers [3].

- Performance Metrics Calculation: For each method, predictions were generated for the 100 benchmark drugs. Recall and Precision at the top prediction (Top 1) were calculated based on the methods' ability to correctly identify the known annotated targets from the curated ChEMBL data [3].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process from data preparation to performance evaluation.

Case Study: Target Prediction in Action

A practical application of this pipeline was demonstrated through a case study on fenofibric acid, a drug used for lipid management. The target prediction and MoA hypothesis generation pipeline suggested the Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta (THRB) as a potential target, indicating opportunities for repurposing fenofibric acid for thyroid cancer treatment [3].

This case exemplifies how computational target prediction can generate testable mechanistic hypotheses. By proposing a new target and potential indication, it lays the groundwork for subsequent experimental validation, a critical step in translating a computational finding into a therapeutic strategy with a viable clinical window.

Successful target prediction and validation rely on a foundation of high-quality data and software tools. The table below lists key resources utilized in the benchmark study and the wider field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Target Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [3] | Bioactivity Database | Provides curated, experimentally validated bioactivity data (IC50, Ki, etc.) for training and validating prediction models. | Contains over 2.4 million compounds and 20 million interactions; includes confidence scores. |

| MolTarPred [3] | Stand-alone Software | Predicts drug targets based on 2D chemical similarity to known active ligands. | Open-source; allows local execution; configurable fingerprints and similarity metrics. |

| PPB2, RF-QSAR, etc. [3] | Web Server / Software | Provides alternative algorithms (Neural Networks, Random Forest) for target prediction via web interface or code. | Accessible without local installation; some integrate multiple data sources and methods. |

| CETSA [7] | Experimental Assay | Validates target engagement in intact cells or tissues, bridging computational prediction and physiological relevance. | Measures thermal stabilization of target proteins upon ligand binding in a cellular context. |

| AlphaFold [25] | AI Software | Generates highly accurate 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences, enabling structure-based prediction. | Expands target coverage for methods requiring protein structures (e.g., molecular docking). |

The systematic comparison establishes MolTarPred as the most effective method for comprehensive target identification, a critical first step in hypothesizing a compound's therapeutic window [3]. The broader trend in drug discovery is the integration of such computational methods with experimental validation techniques like CETSA to create robust, data-rich workflows [7]. This synergy between in silico prediction and empirical validation helps de-risk the drug development process, enabling more informed decisions earlier in the pipeline.

As the field evolves, the emergence of agentic AI systems and more sophisticated foundation models promises to further augment this process [26]. However, these computational tools remain powerful complements to, rather than replacements for, traditional medicinal chemistry and experimental biology. The ultimate goal of establishing a safe and efficacious therapeutic window is best served by a hybrid human-AI approach that leverages the strengths of both [26].

A Practical Guide to Key Target Validation Methods and Techniques

In modern drug discovery, establishing a direct causal relationship between a gene target and a disease phenotype is paramount. Genetic perturbation tools—technologies that allow researchers to selectively reduce or eliminate the function of a gene—form the backbone of this functional validation process. For over a decade, RNA interference (RNAi) served as the primary method for gene silencing. However, the emergence of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 has fundamentally transformed the landscape [27] [28]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two foundational technologies, focusing on their mechanisms, performance, and optimal applications within target validation workflows. Understanding their distinct operational frameworks, strengths, and limitations enables researchers to select the most appropriate tool, thereby de-risking the early stages of therapeutic development.

RNA Interference (RNAi): The Knockdown Pioneer

RNAi is an endogenous biological process that harnesses a natural cellular pathway for gene regulation. Experimental RNAi utilizes synthetic small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or vector-encoded short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that are introduced into cells. The core mechanism involves several steps. First, the cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is processed by the endonuclease Dicer into small fragments approximately 21 nucleotides long. These siRNAs then load into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Within RISC, the antisense strand guides the complex to complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences. Finally, the Argonaute protein within RISC cleaves the target mRNA, preventing its translation into protein. This results in a knockdown—a reduction, but not complete elimination, of gene expression at the mRNA level [27]. The effect is typically transient and reversible, which can be advantageous for studying essential genes.

CRISPR-Cas9: The Genome Editing Powerhouse

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a programmable DNA-editing tool, adapted from a bacterial immune defense mechanism. Its operation occurs at the genomic DNA level and requires two components: a Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA, designed to be complementary to a specific DNA locus, directs the Cas9 nuclease to the target site in the genome. Upon binding, the Cas9 nuclease creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA. The cell's repair machinery, specifically the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, then fixes this break. This repair often introduces small insertions or deletions (indels), which can disrupt the coding sequence of the gene. If a frameshift mutation occurs, it leads to a premature stop codon and a complete loss of functional protein, resulting in a permanent knockout [27] [29]. This fundamental difference—operating at the DNA level versus the mRNA level—is the primary source of the contrasting performance profiles of CRISPR and RNAi.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic differences between these two technologies.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

Direct comparative studies and user surveys provide critical insights into the real-world performance of RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9. The data below summarize key performance metrics from published literature and industry reports.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9

| Performance Metric | RNAi (shRNA/siRNA) | CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Outcome | Reversible knockdown (mRNA level) | Permanent knockout (DNA level) | [27] [29] |

| Silencing Efficiency | Moderate to low (variable protein reduction) | High (complete, stable silencing) | [30] [31] |

| Off-Target Effects | High (due to miRNA-like off-targeting) | Low (with optimized gRNA design) | [27] [31] |

| Primary Use in Screens | ~34% of researchers (non-commercial) | ~49% of researchers (non-commercial) | [32] |

| Essential Gene Detection (AUC) | >0.90 | >0.90 | [33] |

| Typical Workflow Duration | Weeks | 3-6 months for stable cell lines | [32] |

A systematic comparison in the K562 chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line demonstrated that both technologies are highly capable of identifying essential genes, with Area Under the Curve (AUC) values exceeding 0.90 for both [33]. However, the same study revealed a surprisingly low correlation between the specific hits identified by each technology, suggesting that they may reveal distinct aspects of biology or be susceptible to different technical artifacts [33].

Industry adoption data from a recent survey underscores the shifting preference, with 48.5% of researchers in non-commercial institutions reporting CRISPR as their primary genetic modification method, compared to 34.6% for RNAi [32]. Notably, the survey also highlighted that CRISPR workflows are often more time-consuming, with researchers reporting a median of 3 months to generate knockouts and needing to repeat the entire workflow a median of 3 times before success [32].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

RNAi Workflow for Gene Knockdown

The standard workflow for an RNAi experiment involves a series of defined steps. First, siRNA/shRNA Design: Sequences of 21-22 nucleotides are designed to be complementary to the target mRNA, often using algorithms to maximize specificity and efficacy [27]. Next is Delivery: The designed siRNAs (synthetic) or shRNA-encoding plasmids are introduced into cells via transfection. A key advantage of RNAi is that cells possess the endogenous machinery (Dicer, RISC) required for the process, simplifying delivery [27]. Finally, Validation: The efficiency of gene silencing is typically measured 48-72 hours post-transfection by quantifying mRNA transcript levels (using qRT-PCR) and/or protein levels (using immunoblotting or immunofluorescence) [27].

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Gene Knockout

The CRISPR-Cas9 workflow, while more complex, enables permanent genetic modification. A critical first step is gRNA Design and Selection: A 20-nucleotide guide RNA sequence is designed to target a specific genomic locus adjacent to a PAM sequence. The use of state-of-the-art design tools and algorithms (e.g., Benchling) is critical for predicting cleavage efficiency and minimizing off-target effects [27] [34]. The next step is Delivery of CRISPR Components: The Cas9 nuclease and gRNA can be delivered in various formats, including plasmids, in vitro transcribed RNAs (IVT), or pre-complexed ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. The RNP format is increasingly the preferred choice due to its high editing efficiency and reduced off-target effects [27] [34]. Following delivery, a Clonal Isolation and Expansion step is often necessary. After editing, cells are single-cell sorted and expanded into clonal populations to isolate those with homozygous knockouts. This step is notoriously time-consuming, often requiring repetition to obtain the desired edit [32] [34]. The process concludes with Validation and Genotyping: The editing efficiency is analyzed in the cell pool using tools like T7E1 assay or TIDE. For clonal lines, Sanger sequencing of the target locus is performed, with analysis by tools like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) to determine the exact indel sequences [27] [34]. Western blotting is recommended to confirm the complete absence of the target protein, as some indels may not result in a frameshift and functional knockout [34].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of the key steps in a CRISPR knockout experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful genetic perturbation experiments rely on a suite of critical reagents and tools. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Genetic Perturbation Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA (synthetic) | Chemically synthesized double-stranded RNA for transient knockdown. | Ideal for rapid, short-term experiments; high potential for off-target effects [27]. |

| shRNA (lentiviral) | DNA vector encoding a short hairpin RNA for stable, long-term knockdown. | Allows for selection of transduced cells; potential for integration-related artifacts [33]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Bacterial-derived or recombinant enzyme that cuts DNA. | High-fidelity variants are available to reduce off-target activity [27] [34]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Synthetic RNA that directs Cas9 to a specific DNA sequence. | Chemically modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) enhance stability and efficiency [34]. |

| RNP Complex | Pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and gRNA. | Gold standard for delivery; high efficiency, rapid action, and reduced off-target effects [27]. |

| ICE / TIDE Analysis | Bioinformatics tools for analyzing Sanger sequencing data from edited cell pools. | Provides a quantitative estimate of indel efficiency without needing full NGS [27] [34]. |

The choice between RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9 is not a simple matter of one technology being universally superior. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the specific research question, the gene of interest, and the desired experimental outcome.

CRISPR-Cas9 has rightfully become the gold standard for most loss-of-function studies due to its high efficiency, permanence, and DNA-level precision. It is the preferred tool for definitive target validation, creating stable knockout cell lines, and screening for non-essential genes. However, its permanent nature and the lengthy process of generating clonal lines are significant drawbacks for certain applications [32] [29].

RNAi remains a valuable and complementary tool. Its transient nature is advantageous for studying essential genes, whose complete knockout would be lethal to cells. It also allows for the verification of phenotypes by observing reversal upon restoration of gene expression. The simpler and faster workflow makes it suitable for initial, high-throughput pilot screens [27] [28].

A powerful emerging strategy is to use both technologies in tandem. Initial hits from a genome-wide CRISPR screen can be validated using RNAi-mediated knockdown. The convergence of phenotypes across both technologies provides strong evidence for a true genotype-phenotype link, minimizing the risk of technology-specific artifacts [33] [31]. As the field advances, the integration of these perturbation tools with other cutting-edge technologies like AI-driven target prediction [3] and cellular target engagement assays [7] will further strengthen the rigor of target validation and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

Chemical probes are highly characterized small molecules that serve as essential tools for determining the function of specific proteins in experimental systems, from biochemical assays to complex in vivo settings [35]. These probes represent powerful reagents in chemical biology for investigating protein function and establishing the therapeutic potential of molecular targets [36]. The critical importance of high-quality chemical probes lies in their ability to increase the robustness of fundamental and applied research, ultimately supporting the development of new therapeutic agents, including cancer drugs [36].

The field has evolved significantly from earlier periods when researchers frequently used weak and non-selective compounds, which generated an abundance of erroneous conclusions in the scientific literature [35]. Contemporary guidelines have established minimal criteria or "fitness factors" that define high-quality chemical probes, requiring high potency (IC50 or Kd < 100 nM in biochemical assays, EC50 < 1 μM in cellular assays) and strong selectivity (selectivity >30-fold within the protein target family) [35]. Additionally, best practices mandate the use of appropriate controls, including inactive analogs and structurally distinct probes targeting the same protein, to confirm on-target effects [35].

With the growing importance of chemical probes in biomedical research, several resources have emerged to help scientists select the most appropriate tools for their experiments. The table below provides a comparative overview of the major publicly available chemical probe resources:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Chemical Probe Resources

| Resource Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Coverage | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Expert-curated probe recommendations | "TripAdvisor-style" star ratings (1-4 stars), expert reviews, usage guidelines [36] [37] | ~800 expert-annotated chemical probes, 570 human protein targets [36] | International expert panel review (Scientific Expert Review Panel) [36] |

| Probe Miner | Comprehensive bioactivity data analysis | Statistically-based ranking derived from mining bioactivity data [35] | >1.8 million small molecules, >2,200 human targets [35] | Computational analysis of medicinal chemistry literature from ChEMBL and canSAR [35] |

| SGC Chemical Probes Collection | Unencumbered access to chemical probes | Openly available probes without intellectual property restrictions [35] | >100 chemical probes targeting epigenetic proteins, kinases, GPCRs [35] | Collaborative development between academia and pharmaceutical companies [35] |

| OpnMe Portal | Pharmaceutical company-developed probes | Freely available high-quality small molecules from Boehringer Ingelheim [35] | In-house developed chemical probes | Pharmaceutical company curation and distribution [35] |

Each resource offers distinct advantages depending on researcher needs. The Chemical Probes Portal provides expert guidance on optimal usage conditions and limitations, while Probe Miner offers comprehensive data-driven rankings across a broader chemical space [35]. The SGC Chemical Probes Collection and OpnMe Portal provide direct access to physical compounds, with the former specializing in unencumbered probes that stimulate open research [35].

Experimental Approaches for Probe Characterization

Target Engagement Validation with CETSA

A critical step in confirming chemical probe utility involves demonstrating direct engagement with the intended protein target in physiologically relevant environments. The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a leading approach for validating direct binding in intact cells and tissues [7]. This method is particularly valuable for confirming that chemical probes effectively engage their targets in complex biological systems rather than merely under simplified biochemical conditions.

Table 2: Key Applications of CETSA in Probe Characterization

| Application Area | Experimental Approach | Key Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Target Engagement | Heating probe-treated cells, measuring thermal stabilization of target protein [7] | Dose-dependent and temperature-dependent stabilization of target protein [7] |

| Tissue Penetration Assessment | Ex vivo CETSA on tissues from probe-treated animals [7] | Confirmation of target engagement in relevant physiological environments [7] |

| Mechanistic Profiling | CETSA combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry [7] | System-level validation of drug-target engagement across multiple protein targets [7] |

Recent work by Mazur et al. (2024) applied CETSA in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantitatively measure drug-target engagement of DPP9 in rat tissue, successfully confirming dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization both ex vivo and in vivo [7]. This approach provides crucial evidence bridging the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy, addressing a fundamental challenge in chemical biology and drug discovery.

Proximity-Based Target Validation for Heterobifunctional Molecules

For novel modalities such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and other heterobifunctional molecules, conventional binding assays may not adequately capture the complex proximity-inducing mechanisms of these compounds. A 2025 study developed an innovative method using AirID, a proximity biotinylation enzyme, to validate proteins that interact with heterobifunctional molecules in cells [38].