Target Product Profile vs. Actual Profile: A Strategic Framework for Drug Development Success

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Target Product Profile (TPP) as a strategic tool in drug development, contrasting its intended role with the realities of its application and...

Target Product Profile vs. Actual Profile: A Strategic Framework for Drug Development Success

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Target Product Profile (TPP) as a strategic tool in drug development, contrasting its intended role with the realities of its application and the resulting 'Actual Profile.' Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of TPPs, methodologies for their effective creation and use, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and frameworks for validating and comparing the TPP against final outcomes. By synthesizing current research and industry insights, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to bridge the gap between strategic planning and execution, thereby enhancing development efficiency, regulatory success, and commercial viability.

What is a Target Product Profile? Defining Your Strategic Compass

In drug development, the Target Product Profile (TPP) serves as a strategic blueprint that outlines the desired characteristics of a final product. It embodies the principle of "beginning with the end goal in mind," guiding research and development from discovery through regulatory approval and commercialization [1]. This guide compares the intended goals defined in a TPP with the actual performance data of a developed product, providing a framework for researchers and developers to objectively assess development success.

Defining the Target Product Profile

A Target Product Profile (TPP) is a strategic development process tool that summarizes the key attributes of an intended commercial product. It acts as a planning tool to focus development activities on a clearly articulated set of goals [2] [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes a TPP as a document that outlines the desired characteristics of a product aimed at a particular disease. It specifies the intended use, target populations, and other desired product attributes, including safety and efficacy-related characteristics [3]. WHO TPPs often describe both a preferred profile and a minimally acceptable profile for vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, or medical devices [3].

In industry, a well-designed TPP provides a framework for development candidates, typically structured with minimally acceptable targets and "stretch" goals. Failure to meet the "essential" parameters often leads to program termination, while meeting the "ideal" profile increases the product's value [2].

Table: Core Components of a Target Product Profile

| TPP Component | Description | Strategic Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Target Population | Defines the specific patient cohort with an unmet medical need [2]. | Guides clinical trial design and patient recruitment strategies. |

| Indication & Context of Use | Specifies the intended disease and clinical use case [4]. | Determines regulatory pathway and labeling claims. |

| Efficacy Endpoints | Outlines primary and secondary efficacy measures for Phase III trials [2]. | Serves as key benchmarks for regulatory success. |

| Safety Profile | Defines the required safety parameters and differentiation from standard of care [2]. | Establishes the product's benefit-risk profile. |

| Dosage & Administration | Details proposed route, schedule, and formulation [2]. | Impacts patient compliance and commercial potential. |

| Shelf Life & Stability | Specifies required product storage conditions and longevity [4]. | Critical for manufacturing, distribution, and market access. |

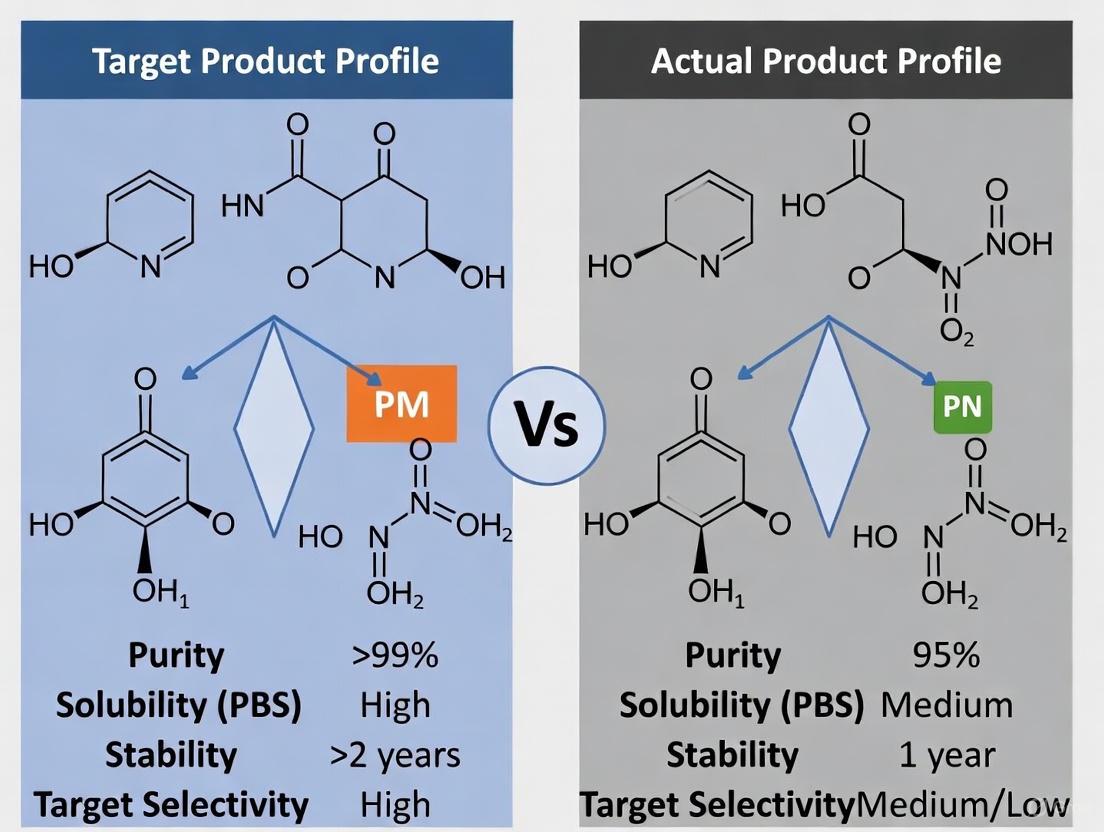

TPP vs. Actual Profile: A Quantitative Framework for Comparison

The true test of a development program's success lies in systematically comparing the Target Product Profile against the Actual Product Profile derived from experimental and clinical data. This comparison objectively measures how well the final product met its initial development goals.

Table: TPP vs. Actual Profile: Efficacy and Safety Comparison

| Performance Attribute | Target Profile (Goal) | Actual Profile (Experimental Data) | Variance Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Efficacy Endpoint | ≥15% improvement over standard of care (SOC) in disease-specific score [2]. | 12% improvement over SOC (p<0.05) from Phase III trial (N=450). | Marginally Missed: Statistically significant but below target delta. |

| Key Safety Metric | Incidence of severe adverse events (SAEs) <5% [2]. | SAEs observed in 4.2% of treatment group vs. 4.8% for SOC. | Met: Profile safer than SOC and within target threshold. |

| Dosage Convenience | Once-daily oral dosing [2]. | Achieved stable pharmacokinetics with once-daily formulation. | Met: Final formulation aligns with target product vision. |

| Stability & Shelf Life | 24-month shelf life at room temperature [4]. | Experimental stability data confirms 22-month shelf life. | Partially Met: Slight shortfall may impact supply chain. |

Experimental Protocol for Efficacy Validation

This protocol outlines the key in vivo experiment to measure efficacy against the TPP's primary endpoint.

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of the investigational product "TheraCandidate" versus Standard of Care (SOC) in a validated mouse model of Disease X, using the clinically relevant primary endpoint defined in the TPP.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Female C57BL/6 mice (n=60, 8-10 weeks old) are induced with Disease X via standard genetic modification protocol.

- Randomization & Blinding: Mice are randomly assigned to three groups (n=20 each): Vehicle control, SOC (50 mg/kg daily), and "TheraCandidate" (10 mg/kg daily). The researcher performing endpoint measurements is blinded to treatment groups.

- Dosing Regimen: Treatments are administered orally once daily for 8 weeks.

- Primary Endpoint Measurement: The disease-specific functional score (e.g., mobility on rotarod) is measured for all animals at baseline and weekly until study end. The primary analysis is the mean percent change from baseline to Week 8 in the "TheraCandidate" group versus the SOC group.

- Statistical Analysis: A two-sample t-test is used to compare the mean percent improvement between the "TheraCandidate" and SOC groups. A p-value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant. The sample size provides 90% power to detect a ≥15% difference.

Visualizing the TPP-Driven Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous process of using the TPP to guide drug development, highlighting the critical feedback loop where experimental data from each stage is used to refine the profile.

The Impact of TPPs on Regulatory and Commercial Success

Using a TPP as a strategic framework significantly influences both regulatory outcomes and commercial performance. Data shows that development programs utilizing a TPP experience tangible benefits.

Table: Impact of TPP Use on Regulatory Outcomes [1]

| Regulatory Metric | With Formal TPP | Without Formal TPP | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median FDA Review Time | Benchmark | 30 days longer | Accelerated approval timeline |

| Refuse-to-File Notification Rate | 0% | Nearly 5% | Higher first-pass submission success |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for conducting the experiments necessary to validate a product against its TPP.

Table: Key Research Reagents for TPP Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Animal Model | In vivo efficacy testing in a biologically relevant system. | Transgenic C57BL/6 mouse model of Disease X. Must display key pathological hallmarks by age 12 weeks. |

| Clinical Grade API | Active pharmaceutical ingredient for formulation and dosing. | "TheraCandidate" API, >99% purity, stored at -20°C under inert atmosphere. |

| Reference Standard | Benchmark for analytical testing and potency assays. | SOC compound (e.g., CommerciallyAvailable), USP grade. |

| Validated Assay Kits | Quantification of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints. | Commercial ELISA kit for Disease X biomarker (e.g., Plasma Protein Y). Measurement range: 15.6-1000 pg/mL. |

| Cell-Based Systems | In vitro mechanism-of-action and safety pharmacology studies. | Stably transfected HEK293 cell line overexpressing Human Target Z. |

The TPP is more than a static document; it is a strategic framework and living document that aligns R&D and commercial functions [1]. The comparative analysis between the target and actual profiles is not merely a final checkmark but a critical, ongoing process that de-risks development. By systematically using the TPP to guide decision-making and incorporating experimental feedback to refine the profile, development teams can significantly enhance the probability of regulatory and commercial success, ensuring that the final product not only meets scientific and regulatory standards but also addresses the unmet medical needs it was designed to solve.

A Target Product Profile (TPP) is a strategic planning tool that outlines the desired characteristics of a medical product, including its intended use, target population, and key performance and safety features [5]. Developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a strategic development process tool, the TPP "embodies the notion of beginning with the goal in mind" [1]. This document serves as a foundational strategic framework that guides the entire drug development process, from initial discovery through regulatory submission and commercial planning. By defining the target label attributes early in development, a TPP ensures that all research and development activities align with specific clinical needs and regulatory requirements, ultimately increasing the likelihood of developing a successful product that addresses unmet medical needs [5].

The strategic purpose of a TPP extends beyond mere documentation; it represents a proactive approach to drug development that facilitates stakeholder alignment, enables efficient resource allocation, and enhances regulatory communication [5]. Perhaps most importantly, a TPP should be considered a living document that continuously evolves with emerging data and insights, supporting informed decision-making at every stage of development [5]. This dynamic nature allows development teams to adapt to new scientific findings, regulatory feedback, and market changes while keeping the ultimate development goals in clear focus.

TPP Structure and Core Components: A Comparative Framework

The structure of a TPP follows a logical format that maps key attributes to target outcomes, typically organized in a summary table that outlines the minimum acceptable and ideal target results for each critical product attribute [5]. This comparative framework enables development teams to distinguish between essential characteristics that must be achieved for regulatory and commercial success and aspirational targets that would provide competitive differentiation or enhanced therapeutic value.

The core components of a TPP are fundamentally aligned with the key sections of drug labeling, ensuring that development efforts focus explicitly on generating the evidence needed to support the desired prescribing information [5]. These typically include:

- Indications and Usage: The primary intended use and any secondary indications

- Dosage and Administration: Including delivery mode, treatment duration, and dose regimen

- Clinical Studies: Target population and clinical efficacy endpoints

- Safety Profile: Adverse reactions and contraindications

- Other Considerations: Pharmacological properties, drug interactions, and product stability

Table 1: Core Components of a Target Product Profile for a New Pharmacotherapeutic

| Drug Label Attributes | Product Properties | Minimum Acceptable Results | Ideal Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indications and Usage | Primary Indication | Specific to therapeutic area | Specific to therapeutic area |

| Indications and Usage; Clinical Studies | Target Population | Specific to therapeutic area | Specific to therapeutic area |

| Dosage and Administration | Treatment Duration | Specific to therapeutic area | Specific to therapeutic area |

| Dosage and Administration | Delivery Mode | Specific to therapeutic area | Specific to therapeutic area |

| Clinical Studies | Clinical Efficacy | Statistically significant improvement vs. placebo | Superior efficacy to standard of care |

| Adverse Reactions | Risk/Side Effect | Acceptable risk-benefit profile | Superior safety to standard of care |

| How Supplied, Storage and Handling | Product Stability and Storage | Standard temperature stability | Extended stability at room temperature |

| Affordability (Price) | Cost of Goods | Commercially viable | Significant advantage over alternatives |

Adapted from NIDA TPP Worksheet [5]

This structured approach ensures that development priorities are clearly defined and that all stakeholders—from R&D to commercial teams—maintain alignment on the target product characteristics throughout the development lifecycle. The TPP becomes particularly valuable when benchmarking against existing therapies, as it allows for direct comparison of attributes and identification of areas where the new product can demonstrate meaningful improvement [5].

Quantitative Impact: TPPs in Regulatory and Commercial Outcomes

The strategic implementation of TPPs demonstrates measurable benefits across regulatory and commercial dimensions. Evidence indicates that development programs incorporating TPPs experience more efficient regulatory reviews and enhanced commercial performance compared to those that do not utilize this strategic tool [1].

A comprehensive analysis of regulatory outcomes revealed that New Drug Applications (NDAs) that referenced a TPP during FDA negotiations underwent a median review time that was 30 days shorter than applications that did not include a TPP [1]. Furthermore, nearly 5% of NDAs approved between 2008 and 2015 that did not reference a formal TPP received an initial refuse-to-file notification, whereas none of the applications that referenced a formal TPP received this notification [1]. This significant regulatory advantage underscores the value of TPPs in facilitating clearer communication between sponsors and regulatory agencies throughout the development process.

From a commercial perspective, products developed with TPPs are more likely to meet their commercial forecasts. A Deloitte survey identified three common reasons for commercial disappointment that TPPs can directly address: (1) poor understanding of the market, including target audience and drivers; (2) limited product differentiation; and (3) market access limitations such as unfavorable formulary placements [1]. The same survey highlighted the TPP as both the cause of and solution to product commercial performance issues, noting that poor performance often reflects "the tendency to progress products through clinical development at the expense of eroding TPP criteria" [1].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Development Programs With vs. Without TPPs

| Performance Metric | With TPP | Without TPP |

|---|---|---|

| Median NDA Review Time | 30 days faster | Baseline |

| Refuse-to-File Notifications | 0% | Nearly 5% |

| First-Year Sales Forecast Achievement | Higher likelihood | 2/3 of recent launches failed |

| Strategic Misalignment Between R&D and Commercial | Reduced | 53% cite as main cause of poor productivity |

Data compiled from Premier Consulting and industry surveys [1]

The data clearly demonstrates that the systematic use of TPPs correlates with improved regulatory outcomes and enhanced commercial performance. This quantitative evidence supports the strategic value of TPPs not merely as administrative documents but as critical tools for de-risking drug development and maximizing the potential for regulatory and commercial success.

TPP Applications Across Product Types: Drugs, Devices, and Diagnostics

The utility of TPPs extends across various medical product categories, including pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and diagnostic tests, with adaptations to address the unique considerations of each product type [5]. The fundamental principle remains consistent—defining target characteristics early to guide development—while the specific attributes reflect the regulatory and performance requirements of each product category.

For pharmaceutical products, TPPs typically focus on the key labeling concepts outlined in Table 1, with particular emphasis on indications, dosing, efficacy, and safety [5]. The example of Lucemyra (lofexidine) for opioid withdrawal mitigation demonstrates how a TPP can be constructed using an existing FDA-approved medication as a benchmark, with the proposed therapy aiming to meet or exceed the standard of care on critical attributes [5].

For medical devices, TPPs address distinct considerations such as technological characteristics, intended use, and clinical testing specific to device performance. For instance, a TPP for a device intended for opioid withdrawal management would include attributes such as treatment duration per session, technological characteristics (e.g., electrical stimulation parameters), and clinical performance metrics such as reduction in Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) scores [5].

For diagnostic tests, including in vitro tests, TPPs focus on analytical performance, clinical validity, and practical implementation factors. A TPP for a fentanyl urine test, for example, would specify attributes such as target molecule, sample type, time to result, diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, and stability during transport [5].

Table 3: Comparative TPP Attributes Across Product Types

| Product Property Category | Pharmaceuticals | Medical Devices | Diagnostic Tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Performance Metrics | Clinical efficacy, Safety profile | Technological characteristics, Clinical performance | Analytical performance, Clinical validity |

| Key Regulatory Considerations | Indications, Dosing, Safety | Intended use, Risk analysis | Sensitivity, Specificity, Reference method |

| Implementation Factors | Treatment duration, Dose regimen | Treatment duration, User training | Time to result, Ease of interpretation |

| Example Benchmarking | Lucemyra for opioid withdrawal | NET Device for opioid withdrawal | Fentanyl urine test strips |

Adapted from NIDA examples of different product TPPs [5]

The adaptation of TPP frameworks to digital health technologies (DHTs), including those incorporating artificial intelligence (AI), represents an emerging application. A systematic review identified 14 TPPs for DHTs, consolidating 248 different characteristics into 33 key attributes, highlighting the need for standardized approaches in this rapidly evolving field [6]. Considerations such as cybersecurity, interoperability, and algorithm transparency become critical components of TPPs for these technologies [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for TPP Development

The development of a robust TPP requires systematic methodologies to ensure that the target characteristics are evidence-based, feasible, and aligned with stakeholder needs. While specific approaches may vary depending on the product type and development stage, several established protocols support effective TPP development.

Landscape Assessment and Competitive Benchmarking

A comprehensive analysis of the current treatment landscape forms the foundation of TPP development [5]. This involves:

- Identifying approved therapies: Documenting existing treatments, their mechanisms of action, efficacy profiles, safety limitations, and approved labeling

- Analyzing clinical practice patterns: Understanding current standard of care, treatment algorithms, and unmet needs from clinician and patient perspectives

- Evaluating pipeline candidates: Assessing competitive products in development through clinical trial databases and scientific publications

- Mapping stakeholder requirements: Incorporating perspectives from patients, providers, payers, and regulators on desired product attributes

This methodology enables the identification of optimal positioning opportunities and differentiation strategies for the new product. For example, when developing a medication for opioid withdrawal, a thorough appraisal of existing options like Lucemyra (lofexidine) provides critical benchmarking data for constructing a competitive TPP [5].

Stakeholder Engagement and Consensus Building

Effective TPP development incorporates input from multiple stakeholders throughout the process. The systematic review of DHT TPPs identified stakeholder engagement as a critical component, with development typically involving stages of "scoping," "drafting," and "consensus-building" [6]. This protocol includes:

- Stakeholder identification: Mapping all relevant parties including patients, clinicians, regulators, payers, and internal stakeholders from R&D, commercial, and manufacturing

- Structured input collection: Using interviews, surveys, advisory boards, and workshops to gather perspectives on desired product attributes

- Iterative refinement: Circulating draft TPPs for comment and revising based on feedback

- Cross-functional alignment: Ensuring internal agreement on TPP targets across R&D, commercial, and regulatory functions

This methodology directly addresses the documented disconnect between R&D and commercial functions, which 53% of biopharmaceutical executives cite as the main reason for poor productivity or lack of R&D success [1].

Target Product Profile Visualization: Strategic Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous, iterative nature of TPP development and its integration throughout the product lifecycle:

Diagram 1: TPP Strategic Development Workflow (65 characters)

This workflow highlights the dynamic nature of TPPs as living documents that evolve throughout the development process, incorporating new data and insights while maintaining alignment with strategic goals.

Developing a robust TPP requires leveraging specific analytical tools and data resources to inform target setting and decision-making. The following table outlines key resources employed in effective TPP development:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for TPP Development

| Tool/Resource | Function in TPP Development | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Real-World Data (RWD) | Provides evidence on current treatment patterns, outcomes, and unmet needs | Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and claims databases to define target population and benchmark outcomes [7] |

| Competitive Intelligence Platforms | Tracks approved and pipeline competitive products | Drug patent databases and clinical trial registries to inform differentiation strategy [7] |

| Stakeholder Engagement Frameworks | Structures input from patients, clinicians, payers | Advisory boards and structured interviews to validate target product attributes [6] |

| Regulatory Guidance Documents | Informs acceptable endpoints and study designs | FDA guidance on TPPs and disease-specific clinical trial endpoints [5] [1] |

| Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Requirements | Identifies evidence needs for reimbursement | NICE, ICER, and other HTA body methodologies to shape value proposition [6] |

| Quality by Design (QbD) Frameworks | Links critical quality attributes to clinical performance | ICH Q8(R2) guidelines to define product quality targets [8] |

These resources enable evidence-based TPP development, ensuring that target characteristics reflect realistic market expectations, regulatory requirements, and stakeholder needs. The integration of real-world evidence is particularly valuable, as it provides insights beyond the controlled clinical trial environment and helps shape development programs to address real-world clinical practice [7].

The strategic purpose of a Target Product Profile extends far beyond document creation—it represents a fundamental shift in how medical products are developed, from reactive problem-solving to proactive goal-oriented development. When effectively implemented as a living strategic framework, TPPs align R&D and commercial functions, facilitate regulatory dialogue, and ultimately increase the likelihood of developing successful products that address meaningful patient needs [5] [1].

The quantitative evidence demonstrates clear benefits: 30-day faster regulatory reviews, elimination of refuse-to-file notifications, and enhanced commercial performance [1]. These advantages are particularly critical in the context of the evolving pharmaceutical landscape, characterized by unprecedented patent cliffs putting approximately $300 billion in annual global revenue at risk and shifting development focus from mass-market blockbusters to targeted specialty therapies [7].

As drug development grows increasingly complex, with emerging modalities, digital health technologies, and AI-driven approaches, the disciplined use of TPPs becomes even more valuable [6] [9]. By beginning with the goal in mind and maintaining strategic focus throughout the development journey, TPPs serve as indispensable tools for navigating the challenges of modern medical product development and delivering meaningful innovations to patients in need.

A Target Product Profile (TPP) serves as a strategic development tool that embodies the concept of "beginning with the goal in mind" [1]. It is a document that summarizes a drug development program in terms of drug labeling concepts and goals, with the commercial success of the product held in the forefront [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the TPP represents more than a regulatory requirement; it is a dynamic strategic framework that aligns scientific development with commercial objectives. By defining the desired characteristics of a product early in development, the TPP creates a shared vision across R&D, commercial, and regulatory functions, ultimately increasing the probability of both regulatory approval and market success [1]. This guide examines the core components of a robust TPP, with particular focus on how labeling concepts and commercial goals must be integrated to bridge the gap between target aspirations and actual product profiles.

Analytical Framework: TPP Structure and Scenarios

The Three-Scenario Approach to TPP Development

A robust TPP typically outlines three distinct scenarios for product development, creating a structured framework for strategic decision-making and risk management [10] [11]. This approach allows development teams to establish clear boundaries for success while maintaining flexibility throughout the development process.

Table 1: TPP Development Scenarios

| Scenario Type | Strategic Purpose | Development Impact | Commercial Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal (Best-case) | Defines ideal product attributes to guide development ambition | Directs design of clinical trials to support maximum claims | Represents product potential for market leadership and premium pricing |

| Target (Likely-case) | Reflects expected product profile based on current data | Serves as primary development target for resource planning | Guides commercial planning and forecast modeling for most probable outcome |

| Minimal (Worst-case) | Establishes viability threshold for continued development | Identifies absolute minimum requirements for regulatory approval | Defines baseline commercial viability and competitive entry point |

Quantitative Evidence for TPP Utility

Research demonstrates significant advantages for development programs that employ structured TPPs. Analysis of regulatory outcomes reveals that New Drug Applications (NDAs) referencing a formal TPP underwent a median review time that was 30 days shorter than those without TPPs [1]. Furthermore, nearly 5% of NDAs approved between 2008-2015 that did not reference a formal TPP received an initial refuse-to-file notification, whereas none that referenced a formal TPP received such notifications [1]. This quantitative evidence underscores the tangible regulatory benefits of a well-constructed TPP.

On the commercial side, surveys indicate that while a record number of products have received FDA approval in recent years, nearly two-thirds of recent drug launches failed to meet their first-year sales forecasts [1]. Of those that did meet first-year forecasts, only 50% continued to meet forecasts in Year 3 [1]. These findings highlight the critical importance of aligning TPP development with authentic market needs rather than internal organizational perspectives alone.

Core Components: Labeling Concepts in TPP Development

Foundational Labeling Elements

The TPP structure directly mirrors the key sections of eventual drug labeling, creating a direct pathway from development targets to approved product information. This alignment ensures that development activities generate evidence specifically tailored to support desired labeling claims.

Table 2: Essential Labeling Components in a TPP

| Labeling Section | TPP Development Considerations | Evidence Requirements | Strategic Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indications and Usage | Precise patient population definition; first-line vs. second-line positioning | Pivotal trial design; comparator selection; subgroup analyses | Defines market size and competitive landscape |

| Dosage and Administration | Formulation, route, frequency, and duration optimization | Bioequivalence studies; pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling | Impacts patient convenience, adherence, and competitive differentiation |

| Contraindications | Identification of specific patient subgroups for exclusion | Preclinical data; early clinical trial safety observations | Defines product liability and risk management strategy |

| Warnings and Precautions | Characterization and quantification of significant risks | Integrated safety database; special population studies | Directs risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) development |

| Adverse Reactions | Comprehensive documentation of reaction frequency and severity | Systematic adverse event collection; laboratory monitoring | Influences benefit-risk assessment and patient/physician acceptance |

| Clinical Pharmacology | Mechanism of action; exposure-response relationships | Phase 1 and 2 studies; drug interaction assessments | Supports dosing rationale and combination use potential |

Strategic Implementation of Labeling Concepts

The process of defining labeling targets in the TPP requires both scientific rigor and strategic foresight. As noted in industry analysis, "The TPP should be developed with the commercial goals of the product in the forefront. These goals should be balanced against the pharmacology of the drug and the practicalities of the clinical development program" [10]. This balance is particularly critical when determining the hierarchical structure of claims within the indications section and establishing clinically meaningful endpoints that will support the desired usage language.

The dynamic nature of the TPP requires regular revisions as clinical data emerges. However, industry analysis cautions against reactive revisions that dilute the product's value proposition, noting that "frequent revisions made to the TPP to account for missed targets further demonstrate that it is not a genuine target" [12]. This highlights the importance of establishing evidence-based ranges for key labeling attributes during early TPP development that accommodate reasonable clinical variability while maintaining commercial viability.

Figure 1: TPP Labeling Development and Alignment Process. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of defining labeling goals, generating supporting evidence, and refining targets based on clinical data and commercial assessment.

Commercial Integration: Beyond Regulatory Approval

Market-Focused TPP Components

While regulatory approval represents a critical milestone, commercial success requires additional considerations beyond the drug label itself. A comprehensive TPP should incorporate explicit commercial objectives that will guide development decisions and resource allocation.

Table 3: Commercial Strategy Components in TPP Development

| Commercial Element | TPP Implementation | Development Linkage | Market Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Differentiation | Defines superiority claims vs. standard of care | Guides comparator selection in clinical trials | Determines positioning and market share potential |

| Target Product Pricing | Establishes value-based pricing targets | Informs endpoint selection to demonstrate superior value | Directly impacts revenue projections and reimbursement strategy |

| Market Access Strategy | Identifies key payer evidence requirements | Shapes health economic and outcomes research (HEOR) plan | Determines formulary placement and patient access |

| Lifecycle Management | Plans for additional indications and formulations | Guides early development of combination therapies | Extends product revenue and competitive positioning |

Quantitative TPP Testing for Commercial Validation

To mitigate commercial risk, leading organizations employ TPP testing methodologies that quantitatively assess the market potential of development candidates [13]. This process involves "formatting the TPP information into a short and optimized summary detailing key drug characteristics" and presenting it to healthcare professionals and other stakeholders to gather feedback on "understandability, credibility, and prescription potential" [13].

This methodology is particularly valuable during three critical decision points: (1) Market opportunity confirmation for business development and licensing activities; (2) New drug development or early drug testing to inform portfolio prioritization; and (3) Launch and commercial strategy preparation for late-stage drugs [13]. By quantifying market response to different TPP scenarios (worst-case vs. base-case vs. best-case), organizations can make evidence-based decisions about which development paths to pursue and how to allocate resources most effectively.

Experimental & Methodological Approaches

Modeling and Simulation in TPP Development

Mathematical modeling represents a sophisticated methodological approach to informing TPP development, particularly for establishing targets for key product attributes. A scoping review of modeling in TPP development identified a structured three-step process: (1) scoping to identify suitable model structures; (2) model development and validation; and (3) analysis with recommendations to set TPP targets [14].

The review found that modeling was most commonly applied to establish targets for clinical efficacy, economic value, and dosage optimization [14]. For device innovations, modeling frequently informed health impact and efficacy attributes [14]. These approaches allow development teams to simulate how different attribute levels might impact clinical outcomes and commercial potential before committing to costly clinical trials.

Research Reagent Solutions for TPP Development

Table 4: Essential Methodologies and Tools for TPP Development

| Methodology/Tool | Primary Application | Strategic Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Preference Elicitation | Quantifying value of product attributes to prescribers and patients | Informs trade-offs between efficacy, safety, and convenience | Requires careful sampling of relevant decision-makers across prescriber segments |

| Health Economic Modeling | Projecting cost-effectiveness and budget impact | Supports pricing strategy and market access planning | Dependent on accurate epidemiological data and appropriate comparator selection |

| Competitive Landscape Analysis | Positioning relative to current and future alternatives | Identifies differentiation requirements and market opportunities | Must account for both approved products and pipeline candidates with overlapping mechanisms |

| Regulatory Precedent Analysis | Informing acceptable claim structure and evidence requirements | Guides clinical trial design and endpoint selection | Requires systematic review of relevant FDA advisory committee materials and product labels |

| Portfolio Optimization Modeling | Allocating resources across development candidates | Maximizes portfolio value through strategic sequencing | Must balance scientific opportunity, commercial potential, and development risk |

Critical Analysis: TPP Limitations and Alternative Approaches

Identified Limitations of Traditional TPP Approaches

While TPPs offer significant strategic value, critical analysis reveals several potential limitations that can undermine their effectiveness. Industry thought leadership has identified that TPPs can stifle innovation by limiting options and encouraging adherence to previously approved product profiles [12]. Specific flaws include:

- Organizational Focus: TPPs are frequently designed from the organization's perspective rather than from the market inward, failing to describe the target needed for commercial success [12].

- Lack of Fixed Target: Frequent updates create shifting goalposts, potentially allowing the TPP to devolve into a description of the drug's current state rather than a genuine target [12].

- Constrained by Past Approvals: Heavy reliance on profiles of previously approved products limits potential for truly innovative approaches as companies anticipate what regulators have previously approved [12].

- Single Indication Focus: Narrow focus on a single indication may prevent exploration of a drug's full potential across multiple therapeutic areas [12].

Emerging Alternatives and Enhancements

To address these limitations, thought leaders advocate for several alternative approaches that maintain the structure of TPPs while enhancing their strategic flexibility:

- Multiple TPP Development: Creating several TPPs representing different development paths allows for broader exploration of a drug's potential and facilitates comparative analysis of different development strategies [12].

- Draft Label Focus: Shifting emphasis from TPP to "draft labels" encourages claim-driven development and creates a more concrete contract between departments [12].

- Early Customer Engagement: Involving customers early and often ensures development remains market-driven and creates opportunities for discovering alternative applications [12].

- Iterative Approach: Embracing uncertainty and continuously refining the product profile based on new data and insights [12].

These enhancements acknowledge that "the TPP is a dynamic document which can be updated as the drug development program progresses and knowledge of the drug increases" [10], while maintaining strategic discipline against core commercial objectives.

A robust Target Product Profile represents far more than a regulatory exercise; it is the fundamental bridge between scientific development and commercial success. By systematically addressing both labeling concepts and commercial goals through structured scenarios, quantitative testing, and market-focused attributes, development teams can significantly enhance both regulatory outcomes and market adoption. The most successful TPPs maintain strategic flexibility while preserving core commercial objectives, incorporating continuous stakeholder feedback, and balancing ambitious targets with development practicality. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering TPP development is not merely an administrative requirement but a critical competency for navigating the complex journey from concept to commercially successful therapeutic product.

In the high-stakes environment of pharmaceutical development, the Target Product Profile (TPP) has traditionally been viewed as a static blueprint—a fixed set of target criteria for a new drug. However, a paradigm shift is underway, recasting the TPP as a dynamic, living document that evolves in response to new data, market feedback, and changing regulatory landscapes. This evolution mirrors the broader concept of "living documents" in business, which are electronic documents that organizations continually revise and update to reflect the current state of a project or strategy, standing in stark contrast to traditional static documents [15].

Framed within the critical context of target product profile versus actual profile research, this dynamic approach provides a robust framework for navigating the inherent uncertainties of drug development. It enables development teams to systematically compare projected goals with emerging real-world data, creating a feedback loop that informs both clinical strategy and commercial planning. This article explores how embracing the TPP's dynamic nature, supported by structured experimental data and comparative analysis, can lead to more informed decision-making and increased probability of launch success.

The Living Document Framework: Core Principles and Business Rationale

What Makes a Document "Living"?

A living document is characterized by its capacity for continuous, collaborative revision and updating. Its core attributes directly contrast with those of static documents [15]:

- Dynamic Nature: It is never truly 'final' and is designed for constant evolution and adaptation.

- Collaborative Editing: Authorized stakeholders can make inputs, suggest changes, and update content in real-time, often within a cloud-based environment.

- Version Control: The system automatically saves new versions, allowing teams to track changes over time and revert if necessary.

- Regular Review: The document undergoes routine examination to ensure its relevancy, accuracy, and compliance, with reviews triggered by specific events or scheduled periodically.

This framework, when applied to a TPP, transforms it from a rigid set of aspirations into a functional, strategic tool that guides a drug from development through to commercialization.

The Business Imperative for Dynamic TPPs

Adopting a living document approach for TPPs addresses several critical challenges in modern drug development:

- Strategic Clarity in Uncertainty: A dynamic TPP acts as a "North Star," providing clarity and direction in an environment of funding constraints and high investor scrutiny. It helps align internal efforts across clinical, regulatory, and commercial functions from the outset [16].

- Foundational Planning: TPP optimization is typically conducted 2-3 years before market entry, allowing insights to shape clinical trial design, regulatory strategy, and promotional planning. This creates an essential anchor for positioning and messaging despite the absence of final clinical data [17].

- Risk Mitigation: The dynamic nature facilitates contingency and scenario planning based on evolving standards of care and regulatory expectations, allowing for strategic pivots without losing sight of core objectives [16].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Dynamic TPPs

A comparison of the traditional static TPP model versus the modern dynamic approach reveals significant differences in philosophy, process, and outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Static TPPs vs. Dynamic Living TPPs

| Feature | Traditional TPP (Static Document) | Dynamic TPP (Living Document) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Fixed blueprint; one-time definition | Strategic compass; evolving hypothesis |

| Update Frequency | Infrequent, major revisions only | Continuous, iterative updates |

| Collaboration | Limited, siloed input | Cross-functional, real-time collaboration |

| Data Integration | Lags behind new data | Integrates new data and insights as they emerge |

| Primary Risk | Becoming obsolete and misaligned | Implementation complexity; requires discipline |

| Decision-Making | Based on initial assumptions | Informed by latest data and market feedback |

| Regulatory Strategy | Fixed early in development | Adaptable to evolving regulatory feedback |

Quantitative Evidence of Dynamic TPP Impact

Industry research underscores the tangible value of investing in a dynamic, research-driven TPP process. Approximately 85% of pharmaceutical launches include TPP evaluation research, with investments typically ranging from $175,000-$375,000, reflecting its foundational importance to launch success [17]. This investment is allocated towards sophisticated research, including conjoint analysis and interactive simulation tools, which quantify how clinical endpoints influence physician prescribing decisions.

Experimental Protocols for TPP Optimization

To effectively manage a TPP as a living document, researchers employ specific experimental protocols designed to generate the data needed for iterative refinement. These methodologies bridge the gap between clinical development and commercial strategy.

TPP Optimization Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, multi-phase workflow for optimizing a Target Product Profile through market research.

Core Methodologies and Their Applications

Table 2: Key Experimental Methodologies for TPP Refinement

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Outputs | Integration Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Exploration (IDIs) | Explore decision drivers, refine TPP presentation | Deep understanding of key attributes, barriers, and language | Precedes quantitative phase; informs stimulus design |

| Conjoint Analysis (Discrete Choice Modeling) | Quantify trade-offs physicians make between attributes | Relative importance of attributes, market share simulation | Core of quantitative phase; inputs scenario modeling |

| Interactive Simulation Tools | Model market impact as clinical data evolves | Dynamic forecasts, sensitivity analysis | Follows quantitative data collection; enables scenario testing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TPP Research

To execute the experimental protocols outlined above, researchers rely on a suite of specialized "reagent" solutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TPP Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Example Solutions | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Design Platforms | Professional slide software (e.g., PowerPoint), specialized survey platforms (e.g., Qualtrics) | Create visually accessible, consistently structured TPP scenarios for physician evaluation |

| Data Collection & Analysis Engines | Conjoint analysis software (e.g., Sawtooth Software), statistical packages (e.g., R, Python) | Execute complex choice tasks, calculate utility scores, and perform sensitivity analyses |

| Forecasting & Simulation Models | Custom Excel-based models, specialized forecasting software (e.g., Treeage) | Translate conjoint results into volume and share projections under different clinical outcomes |

| AI-Enhanced Insight Tools | Literature analysis AI, regulatory document scanners | Extract insights from vast scientific and regulatory literature to inform TPP assumptions [16] |

Navigating the Challenges: From Theory to Practice

While the benefits are significant, implementing a dynamic TPP process is not without its challenges. Recognizing and mitigating these pitfalls is crucial for success.

Common TPP Research Pitfalls and Mitigation Strategies

- Information Overload: TPPs often contain excessive clinical detail, overwhelming physicians and obscuring key decision factors. Mitigation: Design TPPs to be comprehensive yet concise, using a clear visual hierarchy to highlight key information [17].

- Unrealistic Scenarios: Testing overly optimistic clinical outcomes skews analysis and produces inflated projections. Mitigation: Partner closely with clinical development teams to identify realistic trial outcomes based on current data [17].

- Marginal Differentiation: Presenting clinically insignificant differences wastes research investment on distinctions that don't influence real-world prescribing. Mitigation: Focus variation on attributes that exceed physicians' minimum threshold for clinical meaningfulness [17].

- AI Implementation Gaps: While AI can streamline TPP creation by extracting insights from scientific literature, it often relies on publicly available data that skews toward successful trials, potentially omitting valuable insights from failed studies [16].

Adopting a living document approach for the Target Product Profile is no longer a theoretical advantage but a practical necessity in modern drug development. This dynamic framework transforms the TPP from a static checklist into a central, strategic hub that actively guides a product through its lifecycle. By continuously aligning the target profile with the emerging actual profile, organizations can navigate pre-launch uncertainty with greater confidence, making informed decisions about clinical development, regulatory strategy, and commercial investment.

The most successful organizations will be those that fully integrate TPP optimization insights across their operations: prioritizing clinical endpoints that drive prescribing decisions, creating dynamic forecasts that reflect a range of potential outcomes, and shaping promotional messages to highlight the most meaningful areas of differentiation. In an era of disruption, the dynamic TPP offers the stability and strategic clarity needed to bring transformative treatments to patients efficiently and successfully.

In the high-cost, high-failure world of drug development, the Target Product Profile (TPP) serves as a critical strategic blueprint. A TPP is a living document that defines the intended attributes of a future therapeutic product, including its indication, patient population, efficacy expectations, safety targets, and dosing [18]. When utilized effectively, it aligns every function—from R&D and regulatory to commercial and manufacturing—around a single vision of success, thereby preventing costly late-stage failures [18]. This guide examines how a disciplined TPP process acts as a risk mitigation tool, comparing successful and failed development pathways to provide actionable insights for researchers and developers.

The Cost of Strategic Misalignment in Drug Development

Without a clear and shared TPP, drug development projects are vulnerable to several critical failure modes. Different departments may pursue conflicting goals, with clinical teams chasing endpoints that payers do not value, and manufacturing scaling a product design that is later revised [18]. This misalignment often leads to a late realization of commercial gaps.

A stark example is Zynteglo, Bluebird Bio's gene therapy for β-thalassemia. While it achieved high clinical efficacy and gained EMA approval in 2019, payer bodies like NICE rejected it due to its high price and limited long-term data [18]. The therapy succeeded clinically but failed commercially because the value proposition and reimbursement strategy were not built into the development process from the beginning—a core function of a robust TPP.

Table: Contrasting Outcomes with and without a Strategic TPP

| Development Factor | Project with a Weak/No TPP | Project with a Strategic TPP |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Alignment | Siloed functions with different definitions of success; high risk of late-stage failure [18]. | Cross-functional team aligned on a single "north star"; decisions trace back to a shared goal [18]. |

| Market Access | Value proposition and payer requirements are afterthoughts, risking rejection post-approval (e.g., Zynteglo) [18]. | Payer perspectives and reimbursement cases are integrated early, de-risking commercial launch [18] [13]. |

| Development Efficiency | Unclear goals lead to wasted resources on developing attributes that are not valued by the market or regulators [6]. | Serves as a decision-making tool for go/no-go decisions, prioritization, and efficient resource allocation [18] [13]. |

| Commercial Potential | High risk of creating "me-too" molecules that are clinically valid but commercially invisible [18]. | Clearly defines competitive differentiation early, guiding development toward a commercially viable product [18]. |

Experimental Protocols: TPP Testing and Validation

A TPP is not a static document; its hypotheses must be rigorously tested and validated throughout the development lifecycle. Quantitative TPP testing with key stakeholders provides unbiased feedback on a drug's value proposition and commercial potential [13].

Protocol 1: Quantitative TPP Testing for Market Validation

This methodology is used to gauge prescription potential, understandability, and credibility of a drug's profile with an audience of interest, typically healthcare professionals (HCPs) [13].

- Objective: To validate the drug's value proposition, estimate market potential, and inform product strategy and pricing [13].

- TPP Formatting: The first step involves formatting the TPP information into a concise, one-page summary that groups key clinical elements (e.g., safety, efficacy, dosing) to facilitate HCP understanding and absorption of information [13].

- Audience Identification: The most relevant expert population must be identified. This can include specialist physicians, nurses, payers, patient advocacy group members, and former industry executives to gain diverse perspectives on clinical utility, pricing, and commercial potential [13].

- Data Collection: A series of streamlined and semi-standardized questions are presented to the target audience to gather clear, unaided feedback on the TPP [13].

- Application in Drug Lifecycle: This testing can be applied at various stages:

- Business Development & Licensing (BD&L): To evaluate external assets for acquisition and fact-check selling claims [13].

- Early Drug Development: To test worst-case, base-case, and best-case clinical trial scenarios to inform prioritization and quantify risks/benefits [13].

- Launch Preparation: To confirm and refine prescription assumptions for key population segments, informing sales forecasts and marketing budgets [13].

Protocol 2: Developing a Public Health-Oriented TPP

For products aimed at addressing public health priorities, organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) employ a structured TPP process.

- Objective: To inform product developers, regulators, and funders about R&D and public health priorities, ensuring that products meet the needs of health systems, with a focus on access, equity, and affordability [3].

- Profile Tiers: WHO TPPs describe two distinct profiles:

- Minimally Acceptable Profile: The minimum criteria a product must meet to be considered.

- Preferred Profile: The desired characteristics of an ideal product [3].

- Stakeholder Alignment: The process is designed to "demand signal" to innovators, aligning R&D with the complex requirements of health systems, which can range from clinical utility to cybersecurity and environmental sustainability [6].

- Alternative for Early-Stage Products: For priority needs where development is early, WHO may issue "Preferred Product Characteristics" (PPCs), which outline desires without specifying minimally acceptable criteria [3].

Visualizing the TPP as a Strategic Framework

The following diagram illustrates how a dynamic TPP functions as a central compass, guiding a drug development program through key questions and stakeholder alignment to reach a successful outcome.

The Scientist's TPP Implementation Toolkit

Successfully implementing a TPP requires more than a document; it requires a set of strategic tools and practices. The following table details key components for building and leveraging a strong TPP.

Table: Essential Tools for TPP-Driven Development

| Tool / Practice | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Cross-Functional Team | Ensures shared ownership across R&D, regulatory, commercial, market access, and CMC (Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls). This transforms the TPP from a file into a strategic alignment mechanism [18]. |

| Stratified Target Definitions | Defines both "Minimum" (essential for approval and commercial viability) and "Ideal" (aspirational) targets. This clarifies the development priorities and provides a framework for negotiation and decision-making [18] [3]. |

| Integrated Market Access | Incorporates payers' perspectives early in the process, making their requirements as critical as those from regulators. This prevents commercial failure due to pricing and reimbursement issues post-approval [18] [13]. |

| Dynamic Dashboard | Embeds TPP metrics into live dashboards for regular tracking. This allows teams to monitor progress against key attributes and quickly identify when the project is diverging from its strategic goals [18]. |

| Linked Decision Gates | Formally connects the TPP to stage-gate milestones and go/no-go decisions. It is used not just for reporting, but to actively drive the portfolio strategy and resource allocation [18] [13]. |

| Quantitative TPP Testing | A market research method to test the drug's profile with HCPs and payers. It provides an unbiased assessment of the value proposition, helping to size market opportunity and refine launch assumptions [13]. |

In the high-stakes environment of drug development, the Target Product Profile is a powerful antidote to strategic misalignment and costly late-stage failures. It transforms a promising molecule from a scientific hypothesis into a viable product by continuously connecting vision with execution. By serving as a dynamic strategic compass—rather than a static document—a well-crafted TPP ensures that every dollar, data point, and development decision moves the organization toward a shared and well-defined goal: delivering a therapy that meets the needs of patients, regulators, and the market.

Building and Applying a Dynamic TPP in the Development Lifecycle

A Target Product Profile (TPP) serves as a strategic blueprint in drug development, outlining the key objectives a drug must meet to gain regulatory approval and reach patients. This document typically specifies minimum viable criteria for approval, base case expectations for performance, and aspirational goals that define true commercial and therapeutic success [16]. In the contemporary pharmaceutical landscape, characterized by funding constraints, regulatory shifts, and evolving therapeutic priorities, TPPs provide essential clarity and direction. They act as a company's North Star, aligning scientific, regulatory, and commercial functions from the outset of development [16]. This framework is designed to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals through a systematic, three-phase process for creating robust TPPs, ultimately enabling more efficient navigation of the complex journey from concept to marketed therapy.

The utility of a TPP evolves significantly across the drug lifecycle. In early-stage development, TPPs help navigate high uncertainty and establish foundational goals. As a program advances, they become more refined, integrating robust data and commercial projections during late-stage development [16]. Furthermore, TPPs are invaluable for contingency planning, encouraging holistic thinking about long-term regulatory and commercial goals and facilitating strategic pivots without losing sight of core objectives [16]. This article presents a stepwise framework for TPP development—encompassing scoping, drafting, and consensus-building—within the broader research context of comparing the target profile with the actual product profile achieved.

A Three-Phase Framework for TPP Development

The development of a comprehensive and actionable TPP can be broken down into three sequential, yet iterative, phases. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points within this framework.

Phase 1: Scoping

The objective of this initial phase is to establish a comprehensive foundational understanding of the clinical, regulatory, and competitive environment.

- Define the Disease Landscape: Conduct a thorough analysis of the unmet medical need, target patient population, natural history of the disease, and current standard of care. This requires a deep understanding of the disease area from both a clinical and patient perspective [16].

- Analyze the Competitive and Regulatory Environment: Systematically review existing therapies and those in development. Critically assess regulatory precedents and guidance from agencies like the FDA and EMA to understand the evidentiary requirements for approval [16] [19]. This includes becoming well-versed in existing FDA resources and guidance documents specific to the therapeutic area.

- Identify Key Stakeholders: Map the internal and external experts whose input is critical. This typically includes clinical scientists, regulatory affairs professionals, commercial strategists, and potentially external key opinion leaders (KOLs) and patient representatives.

Phase 2: Drafting

In this phase, the structured TPP document is created, moving from a conceptual plan to a detailed written profile.

- Establish the TPP Structure: Adopt a standardized structure for the TPP document. The World Health Organization (WHO) often structures its TPPs with broad sections including an overview, methods, and the profile itself, which details both minimal and optimal characteristics for the product [20].

- Populate Key Attributes: Define the specific, measurable targets for each critical attribute. These generally include indication and usage, dosage form and route of administration, dosing regimen, efficacy endpoints, safety/tolerability profile, and pharmacokinetic properties [14] [20].

- Apply Modelling to Inform Targets: Utilize mathematical modelling to provide a quantitative basis for setting targets. As identified in a scoping review, modelling is commonly applied to establish targets relating to clinical efficacy, health impact, economic value, and optimal dosage [14]. The modelling process typically involves scoping, model development and validation, and finally, analysis with recommendations [14].

Phase 3: Consensus-Building

The final phase focuses on socializing the draft TPP, incorporating feedback, and securing formal alignment across the organization and with partners.

- Circulate Draft for Internal Review: Share the drafted TPP with all relevant internal functions (e.g., R&D, clinical development, regulatory, commercial, market access) to identify areas of misalignment and resolve conflicting priorities.

- Incorporate External Expert Feedback: Present the TPP to external advisors, KOLs, and potentially regulators through formal meetings (e.g., FDA advice meetings) to pressure-test assumptions and ensure the profile is aligned with clinical practice and regulatory expectations [16]. Engaging early and strategically with regulators is particularly important for complex or orphan indications [16].

- Finalize and Secure Formal Endorsement: Incorporate feedback to create a final version of the TPP. This document should then receive formal sign-off from senior leadership, cementing its role as the strategic guide for all subsequent development activities.

Experimental Protocols for TPP Data Generation and Comparison

Validating the targets within a TPP requires robust experimental data. The following section outlines standard methodologies for generating key efficacy and safety data, which are crucial for comparing the product's performance against alternatives and for the subsequent comparison of the target versus actual profile.

Protocol for Clinical Efficacy Trials in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The following workflow details the major steps in a UC clinical trial, as per FDA and EMA guidelines, which serve as a model for rigorous efficacy evaluation.

1. Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of an investigational drug for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC), as per contemporary regulatory standards [19].

2. Trial Design:

- Design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. For maintenance studies, both induction followed by randomized withdrawal and "treat-through" designs are acceptable [19].

- Duration: Induction phase typically lasts 8-14 weeks. The maintenance phase should be at least one year to support claims of sustained therapeutic benefit [19].

- Comparator: Placebo is standard. The FDA encourages active comparator trials to demonstrate superiority over approved therapies, though non-inferiority designs may also be acceptable [19].

3. Patient Population:

- Diagnosis: Confirmed diagnosis of UC based on endoscopy and histopathology [19].

- Disease Activity: Participants must have moderately to severely active UC, defined by a modified Mayo Score (mMS) of 5 to 9. The mMS is a composite score comprising stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and endoscopic findings [19].

- Key Criterion: A minimum endoscopic subscore of ≥2, as determined by a blinded central reader, is required [19]. The study population should reflect clinically relevant diversity and include a balance of patients naive to and those who have failed prior advanced therapies.

4. Endpoints:

- Primary Endpoint (Induction): The proportion of participants achieving clinical remission at the end of the induction phase. Per FDA 2022 guidance, this is strictly defined as an mMS of 0 to 2, with all of the following components:

- Stool frequency subscore of 0 or 1 (and no higher than baseline)

- Rectal bleeding subscore of 0

- Centrally read endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1 (excluding friability) [19].

- Key Secondary Endpoints:

- Clinical Response: Defined as a decrease from baseline in the mMS of ≥2 points and ≥30% reduction, plus a decrease in rectal bleeding subscore of ≥1 or an absolute rectal bleeding subscore of 0 or 1 [19].

- Corticosteroid-Free Remission: The proportion of participants in clinical remission at the end of the maintenance phase who have had no corticosteroid exposure for a prespecified period (e.g., 8-12 weeks) prior to the assessment, among those using corticosteroids at baseline [19].

- Endoscopic Improvement: Proportion of participants achieving an endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1.

5. Assessments and Procedures:

- Endoscopy: Full colonoscopy to assess all colonic segments is explicitly recommended by the FDA. Endoscopic severity must be assessed using high-definition video recordings reviewed by blinded central readers. The protocol must specify how discrepancies between site and central readers will be resolved [19].

- Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs): Stool frequency and rectal bleeding subscores are derived from a daily patient electronic diary. A 7-day assessment period is recommended, excluding days of bowel preparation and endoscopy, with averages calculated from at least 3 consecutive or 4 nonconsecutive diary days [19].

Protocol for Integrating Real-World Evidence (RWE) into TPP Refinement

1. Objective: To utilize Real-World Data (RWD) to generate Real-World Evidence (RWE) that can supplement clinical trial data, inform TPP attributes (e.g., comparative effectiveness, safety in broader populations), and support regulatory and reimbursement decisions [21].

2. Data Source Identification and Evaluation:

- Potential Sources: Identify relevant RWD sources such as electronic health records (EHRs), claims databases, disease registries, and data from wearables or mobile apps [21].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate data quality based on dimensions outlined in regulatory frameworks. Per the FDA, this includes relevance (availability of key data elements, representative patients) and reliability (accuracy, completeness, provenance). The EMA framework adds dimensions of extensiveness, coherence, and timeliness [21].

3. Study Design and Analysis:

- Design Selection: Choose an appropriate observational study design (e.g., cohort study, case-control study) that minimizes confounding and bias to address the specific research question.

- Linking Data: To create a richer data ecosystem, consider linking different RWD sources (e.g., linking EHR data with claims data) or linking clinical trial data with RWD. Tokenization can be used to enable linking while preserving patient anonymity [21].

- Analytical Techniques: Employ advanced statistical methods to account for confounding. Machine Learning (ML) can be used as a powerful tool for analyzing large sets of unstructured data (e.g., from physicians' notes in EHRs), primarily for predictive modeling and variable selection [21].

4. Evidence Generation and Application:

- Outputs: Generate evidence on clinical outcomes in real-world populations, comparative effectiveness, treatment patterns, and long-term safety.

- Application to TPP: Use this RWE to validate or refine assumptions in the TPP regarding drug performance in heterogeneous populations, potential market share, and real-world value proposition. This evidence is critical for bridging the gap between the controlled trial environment and actual clinical practice.

Comparative Analysis: Regulatory Standards and TPP Alignment

A critical function of the TPP is to ensure that development plans meet regulatory requirements across key markets. The following table provides a comparative overview of FDA and EMA guidelines for UC trial design, which should directly inform the "Regulatory" and "Efficacy" sections of a TPP for a gastrointestinal product.

Table 1: Comparison of FDA (2022) and EMA (2018) Guidelines for Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Trials

| Aspect | FDA (2022 Guidance) | EMA (2018 Guidance) |

|---|---|---|

| Trial Population | mMS of 5-9 for moderate-severe disease; balanced representation across disease severity and prior treatment experience. [19] | Full Mayo score of 6-12 for moderate-severe disease; minimum symptom duration of 3 months. [19] |

| Key Efficacy Endpoint | Clinical remission: mMS 0-2, with SFS 0/1, RBS 0, and endoscopic subscore 0/1 (no friability). [19] | Aligned on components, but defines symptomatic remission as a clinical Mayo score of 0 or 1. [19] |

| Endoscopic Assessment | Explicitly recommends full colonoscopy; central reading required with protocol for resolving discrepancies. [19] | Supports standardized central reading; does not specify sigmoidoscopy vs. colonoscopy. [19] |

| Maintenance Trial Design | Accepts both induction/withdrawal and treat-through designs; duration of at least 1 year. [19] | Aligned on design and duration; provides additional guidance on limiting placebo use to 6 months. [19] |

| Additional Guidance | Encourages active comparator trials; emphasizes diversity in study populations. [19] | Provides specific guidance on pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and dose-finding studies. [19] |

Abbreviations: mMS, modified Mayo Score; SFS, Stool Frequency Subscore; RBS, Rectal Bleeding Subscore.

The following table details key research reagents and solutions critical for conducting the experiments necessary to populate and validate a TPP, particularly for a biologic drug candidate.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biologics Development

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Application in TPP Validation |

|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Used for mechanism of action (MoA) studies and potency assays. Critical for establishing the biological activity of the drug product, a key quality attribute in the TPP. |

| Validated Animal Models | Provide in vivo proof-of-concept data on efficacy and pharmacodynamics. Data from relevant disease models is essential for justifying the proposed indication and dosing regimen in the early TPP. |

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized biological substances used to calibrate assays and ensure consistency across experiments. Vital for demonstrating manufacturing consistency and product stability. |

| Anti-Drug Antibody (ADA) Assay Kits | Used to assess immunogenicity in pre-clinical and clinical studies. Results directly inform the "Safety" section of the TPP, predicting potential for reduced efficacy or adverse events. |

| GMP-Grade Cytokines & Growth Factors | Essential for the manufacturing process of cell-based therapies or certain biologics. Their quality and consistency are directly linked to critical quality attributes specified in the TPP. |

Leveraging Real-World Data for TPP Assumptions and Economic Modeling

A Target Product Profile (TPP) is a strategic planning tool that outlines the desired characteristics of a medical product, ensuring that research and development efforts align with specific clinical needs and regulatory requirements [5]. Traditionally serving as a "North Star" for cross-functional teams, the TPP articulates ideal attributes such as intended indication, target population, efficacy goals, and safety thresholds [22]. However, in today's evolving healthcare landscape, securing regulatory approval alone is no longer sufficient for commercial success. Pharmaceutical companies now face increasing pressure from health technology assessment (HTA) bodies and payers who demand robust evidence of value, creating an urgent need to enhance traditional TPP approaches with real-world data (RWD) throughout the development lifecycle [23] [22].

This guide examines how the integration of RWD into TPP development and economic modeling creates a more evidence-based approach to drug development. By comparing traditional TPP processes with RWD-enhanced methods across key performance dimensions, we provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical frameworks for bridging the gap between clinical development and market access requirements. The analysis reveals how RWD strengthens TPP assumptions, informs economic models, and ultimately supports the development of products that not only gain regulatory approval but also achieve commercial success and patient access.

Traditional TPP Limitations Versus RWD-Enhanced Approaches

Critical Deficiencies in Traditional TPP Development

The conventional predicted TPP approach contains fundamental flaws that undermine its effectiveness in contemporary drug development. First, TPP prediction often defaults to expertise or becomes a negotiation between aspirational and pragmatic thinking, especially as companies push for commercial perspectives earlier in development with less in-human data [23]. Second, this approach focuses internal dialogue on the asset rather than the disease and unmet needs, becoming disconnected from what multiple market stakeholders actually require [23]. Third, an inherent flaw exists in business cases based on predicted TPPs, where forecasts based on optimistic clinical outcomes are risk-adjusted on the probability of achieving different (often lower) approvability thresholds [23].

These deficiencies manifest in several problematic outcomes. Organizations struggle with investment decisions when clinical data miss TPP predictions, causing material delays in development timelines [23]. The lack of transparency around these decisions can negatively affect organizational culture. Furthermore, traditional TPPs often fail to adequately address the divergent requirements of regulators, HTAs/payers, and physicians, leading to situations where approved products face reimbursement challenges or poor market uptake [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional versus RWD-Enhanced TPP Approaches

| Development Aspect | Traditional TPP Approach | RWD-Enhanced TPP Approach | Impact of Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence Foundation | Primarily based on preclinical data, limited early clinical data, and expert opinion | Incorporates longitudinal patient data, comparative treatment patterns, and outcomes from real-world settings | More realistic assessment of therapeutic potential and competitive positioning |

| Stakeholder Alignment | Focused on regulatory requirements and internal alignment | Explicitly addresses HTA/payer evidence needs, physician decision drivers, and patient preferences | Reduces late-stage surprises in market access and adoption |

| Economic Modeling | Based on theoretical assumptions about treatment pathways, resource use, and outcomes | Grounded in actual healthcare utilization patterns, costs, and patient outcomes | More accurate value demonstration and budget impact forecasting |

| Risk Assessment | Single-point probability of regulatory approval | Multi-dimensional risk assessment across regulatory, reimbursement, and commercial domains | Better capital allocation decisions and portfolio strategy |

The ARCH Model: A Structured Framework for RWD Integration

The ARCH model presents a compelling alternative to traditional TPPs by explicitly acknowledging the different evidence requirements for approval, reimbursement, commercial viability, and hope (scientific vision) [23]. This framework offers a natural structure for integrating RWD throughout the development process:

- Approval Requirements: RWD can inform regulatory strategy by providing context on natural history, standard of care outcomes, and external control arms for difficult-to-study populations.

- Reimbursement Requirements: RWD elucidates HTA and payer evidence expectations, including comparative effectiveness, quality of life measures, and economic endpoints.