Target Identification and Validation in Drug Discovery: Foundational Concepts, Advanced Methods, and Future Trends

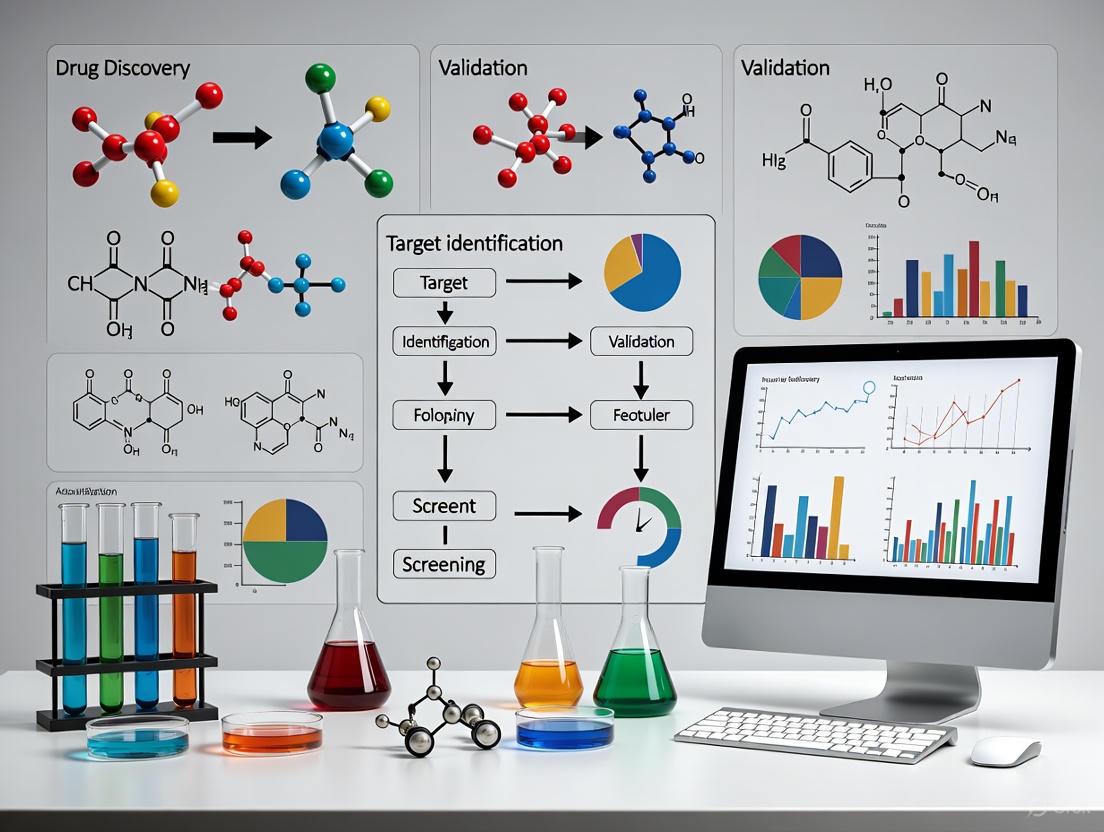

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical processes of target identification and validation in modern drug discovery.

Target Identification and Validation in Drug Discovery: Foundational Concepts, Advanced Methods, and Future Trends

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical processes of target identification and validation in modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of druggable targets, details established and emerging methodological approaches—including AI-driven platforms, affinity-based proteomics, and cellular validation techniques—and addresses common challenges and optimization strategies. By synthesizing current trends and validation frameworks, the content offers a practical guide for enhancing success rates in the early, high-stakes stages of therapeutic development.

The Bedrock of Therapy: Defining Druggable Targets and Discovery Paradigms

What Makes a Target 'Druggable'? Key Properties for Success

In the modern drug discovery pipeline, the identification and validation of druggable targets represent the critical first step upon which all subsequent efforts are built. A druggable protein is defined as one that can bind to small drug-like molecules with high affinity and produce desirable therapeutic effects [1]. The significance of target druggability cannot be overstated—approximately 60% of failures in drug discovery projects can be attributed to targets ultimately proving to be undruggable [1]. This high failure rate underscores the necessity of accurately assessing druggability early in the research process, potentially saving billions of dollars and years of development time.

The traditional drug development pipeline, from target identification to regulatory approval, typically spans 10-17 years, incurs costs ranging from $2 to $3 billion, and yields a success rate of less than 10% [2]. Within this challenging landscape, the precise identification of viable drug targets has emerged as a fundamental discipline that bridges basic biological research and clinical application. This technical guide examines the key properties that confer druggability upon potential targets, the experimental and computational approaches for their identification, and the emerging trends reshaping this crucial field.

Fundamental Properties of Druggable Targets

Structural and Physicochemical Characteristics

Druggable targets possess distinct structural and physicochemical properties that enable specific, high-affinity binding to small molecules. Analysis of known drug targets reveals several consistent patterns:

Binding Site Architecture: Druggable targets typically contain well-defined binding pockets with appropriate geometry and physicochemical complementarity to drug-like molecules. These binding sites often range from 600-1000 ų in volume and display characteristic patterns of hydrophobicity, hydrogen bonding potential, and surface topology [3].

Amino Acid Composition: Statistical analyses indicate that druggable proteins exhibit distinct sequence patterns, with hydrophobic residues (Phe, Ile, Trp, Val) and specific polar residues (Glu, Gln) serving as particularly discriminative features [4]. These compositional biases influence binding site properties and overall protein flexibility.

Structural Classification: The majority of successful drug targets fall into specific protein families. Enzymes constitute approximately 70% of targets in structure-based virtual screening campaigns, with kinases (57 unique targets), proteases (24 unique targets), and phosphatases (16 unique targets) being particularly well-represented [3]. Membrane receptors (32 unique targets) and nuclear receptors (11 unique targets) comprise most of the remaining druggable targets.

Table 1: Distribution of Protein Targets in Structure-Based Virtual Screening Studies

| Target Classification | Percentage of Studies | Unique Targets Represented |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | 70% | 190 |

| - Kinases | 17.4% | 57 |

| - Proteases | 9.3% | 24 |

| - Phosphatases | 4.8% | 16 |

| - Other Enzymes | 38.7% | 135 |

| Membrane Receptors | 10.0% | 32 |

| Nuclear Receptors | 6.0% | 11 |

| Transcription Factors | 2.9% | 10 |

Functional and Biological Properties

Beyond structural features, druggable targets share common biological characteristics that influence their therapeutic utility:

Modulation Capability: Successful targets can be effectively modulated (inhibited, activated, or allosterically regulated) by small molecules to produce a measurable physiological effect. This requires that the target's function is pharmacologically tractable—meaning that small molecule binding translates to meaningful functional consequences.

Therapeutic Relevance: The target must play a verifiable role in disease pathology, with evidence that modulation will produce therapeutic benefits without unacceptable toxicity. Genetic validation (e.g., through knockout studies or human genetic associations) provides particularly compelling evidence for therapeutic relevance.

Tissue Distribution and Expression: Ideal targets exhibit appropriate tissue distribution and expression patterns that enable therapeutic intervention while minimizing off-target effects. Targets with restricted expression in disease-relevant tissues often present more favorable therapeutic indices.

Computational Approaches for Druggability Assessment

Structure-Based Prediction Methods

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS), also known as molecular docking, has become an established computational approach for identifying potential drug candidates based on target structures [3]. The fundamental premise of SBVS involves computationally simulating the binding of small molecules to a target protein and scoring these interactions to identify high-affinity binders.

The SBVS workflow typically involves:

- Target Preparation: Obtaining and refining the three-dimensional protein structure

- Binding Site Identification: Locating and characterizing potential binding pockets

- Library Screening: Docking large chemical libraries (often millions of compounds)

- Scoring and Ranking: Prioritizing compounds based on predicted binding affinity

- Visual Inspection: Manually examining top-ranking compounds before experimental testing

A comprehensive survey of prospective SBVS applications revealed that GLIDE is the most popular molecular docking software, while the DOCK 3 series demonstrates strong capacity for large-scale virtual screening [3]. The same analysis found that approximately one-quarter of identified hits showed better potency than 1 μM, demonstrating the method's effectiveness at identifying active compounds.

Sequence-Based Machine Learning Approaches

For targets without experimentally determined structures, sequence-based machine learning methods offer powerful alternatives for druggability prediction. These approaches leverage various feature descriptors derived from protein sequences, including:

- Amino Acid Composition (AAC): The relative frequencies of each amino acid

- Pseudo-Amino Acid Composition (PAAC): A set of discrete modes that incorporate sequence-order information

- Composition-Transition-Distribution (CTD): Features that describe composition, transition, and distribution of specific attributes

- Dipeptide Composition (DPC): Frequencies of dipeptide combinations

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Druggability Prediction Tools

| Method | Classifier | Features | Accuracy | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPIDER [1] | Stacked Ensemble | AAC, APAAC, DPC, CTD, PAAC, RC | 95.52% | Web server |

| optSAE+HSAPSO [2] | Stacked Autoencoder + Optimization | Learned representations | 95.5% | Code only |

| XGB-DrugPred [1] | XGBoost | GDPC, S-PseAAC, RAAA | 94.86% | No |

| GA-Bagging-SVM [1] | SVM Ensemble | DPC, RC, PAAC | 93.78% | No |

| DrugMiner [1] | Neural Network | AAC, DPC, PCP | 89.98% | Yes |

Recent advances in deep learning have significantly enhanced prediction capabilities. The SPIDER tool represents the first stacked ensemble learning approach for druggable protein prediction, integrating multiple machine learning classifiers to achieve robust performance [1]. Similarly, the optSAE+HSAPSO framework combines a stacked autoencoder for feature extraction with hierarchically self-adaptive particle swarm optimization, achieving 95.5% accuracy on curated pharmaceutical datasets [2].

Experimental Validation of Target Druggability

Structure-Based Experimental Protocols

Experimental validation of target druggability typically begins with structural characterization, followed by binding assays and functional studies:

Protein Production and Structural Determination

- Target Selection: Prioritize targets with genetic or functional validation for disease relevance

- Protein Expression: Express recombinant protein in suitable systems (e.g., E. coli, insect cells, mammalian cells)

- Purification: Purify protein to homogeneity using affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography

- Structural Determination: Determine 3D structure using X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM

- Binding Site Analysis: Characterize potential binding pockets using computational tools and mutagenesis

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Protocol [3]

- Structure Preparation: Remove water molecules and cofactors not essential for binding; add hydrogen atoms; optimize side-chain conformations

- Binding Site Definition: Define the search space for docking based on known ligand positions or predicted binding sites

- Compound Library Preparation: Curate screening library (often 1,000-10,000 compounds) with drug-like properties; generate 3D conformations

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking simulations using programs like GLIDE, AutoDock, or GOLD

- Hit Selection: Select top-ranking compounds (typically 20-100) based on docking scores and visual inspection

- Experimental Testing: Procure selected compounds and test in biochemical assays

Functional Validation Methods

Following initial hit identification, comprehensive functional validation is essential:

Biochemical and Biophysical Assays

- Binding Affinity Measurements: Determine Kd values using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), or microscale thermophoresis (MST)

- * enzymatic Activity Assays*: Measure compound effects on target function using fluorogenic or colorimetric substrates

- Cellular Target Engagement: Confirm target binding in physiological contexts using cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)

Phenotypic Characterization

- Cellular Functional Assays: Evaluate compound effects on downstream signaling pathways, gene expression, or phenotypic readouts

- Animal Models: Assess efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity in disease-relevant animal models

- Counter-Screening: Test compounds against related targets to establish selectivity profiles

A survey of SBVS case studies revealed that while most virtual screenings were carried out on widely studied targets, approximately 22% focused on less-explored new targets [3]. Furthermore, the majority of identified hits demonstrated promising structural novelty, supporting the premise that a primary advantage of SBVS is discovering new chemotypes rather than highly potent compounds.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Druggability Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology | X-ray Crystallography, Cryo-EM, NMR | Determine 3D protein structure for binding site analysis |

| Virtual Screening | GLIDE, AutoDock Vina, GOLD | Computational docking of compound libraries to target structures |

| Binding Assays | Surface Plasmon Resonance, ITC, MST | Quantify binding affinity and thermodynamics of compound-target interactions |

| Functional Assays | Fluorogenic substrates, Reporter gene systems | Measure functional consequences of target modulation |

| Cellular Validation | CETSA, BRET, CRISPR-Cas9 | Confirm target engagement and functional effects in cellular contexts |

| Compound Libraries | Diversity sets, Fragment libraries, Targeted libraries | Source of chemical matter for experimental screening |

Case Studies and Emerging Trends

Successful Applications in Novel Target Space

Recent years have witnessed successful applications of druggability assessment to challenging target classes:

Targeting Viral Sugars with Synthetic Carbohydrate Receptors Researchers recently developed broad-spectrum antivirals that work against several virus families by blocking N-glycans—targets previously considered undruggable [5]. The approach utilized flexible synthetic carbohydrate receptors (SCRs) with extended arms that rotate and interact with hydroxyl and hydrogen groups on viral sugars. This strategy departed from traditional rigid inhibitors, with the lead compound SCR007 demonstrating efficacy in reducing mortality and disease severity in SARS-CoV-2-infected mice [5].

Druggability Assessment of Underexplored Human Proteins Several SBVS studies have focused on validating the druggability of previously unexplored human targets. For example, researchers applied SBVS to identify novel inhibitors of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase σ, potentially enabling new therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases [3]. Similarly, SBVS was used to discover potent inhibitors against peroxiredoxin 1, validating its druggability in leukemia-cell differentiation [3].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of druggability assessment is rapidly evolving, with several notable trends shaping its future:

Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Optimization Modern frameworks like optSAE+HSAPSO combine stacked autoencoders for robust feature extraction with hierarchically self-adaptive particle swarm optimization for parameter tuning [2]. This approach delivers superior performance across various classification metrics while significantly reducing computational complexity (0.010 s per sample) and demonstrating exceptional stability (± 0.003) [2].

Expansion to Challenging Target Classes While traditional drug targets have predominantly been enzymes and receptors, emerging approaches are tackling previously "undruggable" targets, including:

- Protein-protein interactions: Targeting large, shallow interfaces

- Transcriptional regulators: Modulating gene expression directly

- RNA structures: Developing small molecules that bind structured RNA elements

- Cellular pathways: Employing polypharmacology to modulate multiple targets

Structural Coverage through Predictive Methods The advent of highly accurate protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold 2 is dramatically expanding structural coverage of the proteome [3]. This advancement enables structure-based assessment of druggability for targets without experimentally determined structures, potentially opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The systematic assessment of target druggability represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, integrating computational prediction, structural analysis, and experimental validation. Key properties including defined binding pockets, appropriate physicochemical characteristics, and therapeutic relevance collectively determine a target's druggability potential. Advances in machine learning, particularly ensemble methods and deep learning architectures, have dramatically improved our ability to identify druggable targets from sequence and structural information. Meanwhile, structure-based approaches continue to evolve, enabling the targeting of previously intractable target classes.

As the field progresses, the integration of artificial intelligence with experimental validation promises to accelerate the identification of novel drug targets while reducing late-stage attrition. The systematic framework outlined in this guide provides researchers with a comprehensive approach for assessing target druggability, ultimately supporting more efficient and successful drug discovery campaigns.

In the disciplined landscape of modern drug discovery, the pathways to identifying a therapeutic target are predominantly structured into two distinct paradigms: target discovery and target deconvolution. Target discovery operates as a forward, hypothesis-driven process, commencing with a defined biological entity believed to play a critical role in a disease pathway. In contrast, target deconvolution is a retrospective, investigative process that begins with a compound eliciting a desirable phenotypic effect and works backward to uncover its molecular mechanism of action [6] [7]. While both strategies aim to pinpoint druggable targets, their philosophical underpinnings, experimental workflows, and applications are fundamentally different. This whitepaper delineates these two core strategies, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists on their principles, methodologies, and integration within a comprehensive target identification and validation framework.

Target identification and validation represent the foundational stage of the drug discovery pipeline, crucial for confirming the functional role of a biological target in a disease phenotype and for establishing its "druggability" [6] [8]. A "druggable" target is defined as a biological entity whose activity can be modulated by a therapeutic agent, such as a small molecule or biologic, to produce a beneficial therapeutic effect [6]. The ultimate validation of a target occurs when a drug modulating it proves to be safe and efficacious in patients [6].

The choice between target discovery and target deconvolution often hinges on the available starting points—a validated hypothesis about a specific target versus a promising compound with an observed phenotypic effect but an unknown mechanism. This decision is critical, as the success of subsequent lead optimization and clinical development depends heavily on a deep understanding of the target and its relationship to the disease [6] [9].

Target Discovery: A Forward-Looking Approach

Core Principles and Workflow

Target discovery is characterized as a target-based or reverse chemical genetics approach [10]. This strategy is predicated on the axiom that to develop a new drug, one must first discover a new target. The process begins with the hypothesis that a specific protein, gene, or nucleic acid plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of a disease. Once such a target is identified and its role established, vast compound libraries are screened to find a drug that binds to the target and elicits the desired therapeutic effect [6].

This approach requires a substantial initial investment in understanding disease biology to select a promising target. The properties of an attractive drug target include a confirmed role in the disease, uneven distribution in the body, an available 3D structure to assess druggability, and a promising toxicity profile [6].

Key Methodologies and Techniques

Target discovery leverages a wide array of modern tools to identify and prioritize potential targets.

- Data Mining and Literature Review: Many targets are initially identified through scientific literature and public databases such as DrugBank or TTD (Therapeutic Target Database) [6]. This method, while common, can lead to intense competition among drug developers.

- Genomic and Proteomic Analyses: Techniques like DNA microarrays and serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) allow for rapid identification of lead targets by analyzing gene expression profiles in diseased versus healthy tissues [11].

- Genetic Associations: Examining genetic polymorphisms linked to disease risk or progression provides powerful validation for a target's role in disease [8]. For instance, mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene in familial Alzheimer's disease strongly implicated the Aβ peptide pathway as a therapeutic target.

- In Silico Discovery: With the completion of several genomes, bioinformatics tools allow for the in silico discovery of therapeutic targets by leveraging growing gene expression databases [11].

The workflow for target discovery, from initial hypothesis to assay development, is illustrated below.

Target Deconvolution: A Retrospective Approach

Core Principles and Workflow

Target deconvolution is a cornerstone of phenotypic drug discovery and forward chemical genetics [10]. This strategy initiates with a small molecule that produces a desirable phenotypic change in a complex biological system—such as a cell-based assay or an animal model—without prior knowledge of its molecular target [7]. The objective is to retrospectively identify the specific biological targets responsible for the observed phenotypic response [6] [7].

This approach has gained renewed momentum due to the perceived limitations and high attrition rates of purely target-based discovery, as it identifies compounds with therapeutic effects in a more physiologically relevant context [7] [9]. A significant advantage is its ability to identify polypharmacologic compounds that act on multiple cellular targets, which may better match the polygenic nature of many complex diseases [9].

Key Methodologies and Techniques

Target deconvolution employs a diverse set of experimental techniques, often categorized into those that require chemical modification of the compound and those that do not.

Direct Affinity-Based Methods

These methods directly exploit the physical affinity between the small molecule and its target protein(s).

- Affinity Chromatography: This classical method involves immobilizing the small molecule (ligand) on a solid support and incubating it with protein extracts. Proteins with a strong enough affinity to the ligand are captured, then eluted and identified, typically via mass spectrometry [12] [7].

- Protein Microarrays: This high-throughput method involves immobilizing thousands of purified proteins on a glass slide. The array is incubated with a labeled version of the drug candidate. After washing, the positions where the label remains indicate successful drug-protein binding, identifying the target [12] [7].

- Expression Cloning Technologies: This group of techniques includes:

- Phage Display: A phage library displaying various proteins on its surface is exposed to the immobilized small molecule. Phage bound to the molecule are captured, eluted, and amplified, and the target protein is identified via DNA sequencing [12].

- mRNA Display: An in vitro approach where a library of mRNA-protein fusion molecules is incubated with the drug candidate. The bound complexes are isolated, and the cDNA is amplified and sequenced to identify the binding protein [12].

- Three-Hybrid Systems: This yeast or mammalian cell-based system uses a trimeric complex. The interaction between the drug and its target protein reconstitutes a functional transcription factor that drives the expression of a reporter gene, signaling the interaction [12] [7].

Functional and Genetic Methods

- Biochemical Suppression: This technique does not rely on affinity. Instead, it involves adding a small molecule to protein extracts to inhibit an activity of interest. An uninhibited protein extract is then fractionated and introduced to the inhibited extract to identify fractions that can suppress the inhibition, thus identifying the suppressor protein [12].

- Chemoproteomics: A broad and powerful field that uses chemical probes to enrich for and profile direct cellular targets of small molecules, often coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry for identification [10].

- Genetic Tools: Methods like RNA interference (RNAi) and CRISPR are used to mimic the effect of a drug by knocking down gene expression. If the knockdown replicates the drug's phenotypic effect, it provides strong evidence for that gene's product being the relevant target [6] [7].

The following diagram outlines the general workflow for phenotypic screening and subsequent target deconvolution.

Comparative Analysis: Strategy Selection

The choice between target discovery and target deconvolution is strategic, with each approach offering distinct advantages and facing specific challenges. The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate strategy for their project.

Table 1: Strategic comparison of target discovery and target deconvolution

| Feature | Target Discovery | Target Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Defined biological target (e.g., protein, gene) [6] | Bioactive small molecule with observed phenotypic effect [7] |

| Philosophy | "If you want a new drug you must find a new target." [6] | "Corpora non agunt nisi fixata" (Drugs will not work unless they are bound) [6] |

| Primary Screening Method | Target-based screening [6] | Phenotypic screening [6] [9] |

| Knowledge of Mechanism of Action (MoA) | Known from the outset [6] | Identified retrospectively [7] |

| Throughput & Cost | Generally faster and less expensive to develop and run [6] | Can be more costly and complex due to cellular assays [6] |

| Physiological Relevance | Can be lower; target is studied in isolation [6] | Higher; target is modulated in its native cellular environment [6] |

| Key Challenge | Target may not translate to a therapeutic effect in vivo [9] | Target identification can be time-consuming and technically challenging [7] [9] |

| Ability to Find Novel Targets | Lower; confined to pre-selected, known biology | Higher; unbiased, can reveal entirely new biology [10] [9] |

| Intellectual Property (IP) Landscape | Can be highly competitive for established targets [6] | Potential for novel IP if a new target is discovered [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Affinity Chromatography (Target Deconvolution)

This is a widely used method for direct identification of small molecule targets [12] [7].

- Ligand Immobilization: A "linker" molecule is chemically introduced to the small molecule (ligand) of interest. This linker allows for the covalent immobilization of the ligand onto a solid chromatographic resin (e.g., sepharose beads) without disrupting its biological activity. A control resin with only the linker is also prepared.

- Sample Preparation and Incubation: Protein extracts are prepared from relevant cells or tissues. The immobilized ligand is incubated with the protein extract for a sufficient time to allow target binding.

- Washing: The resin is thoroughly washed with an appropriate buffer to remove all unbound and non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Specifically bound proteins are eluted from the resin. This can be achieved using several methods:

- Specific Elution: Using a high concentration of the free (non-immobilized) ligand to compete for binding.

- Non-specific Elution: Using denaturing conditions (e.g., low pH, high salt, SDS) to disrupt the protein-ligand interaction.

- Target Identification: The eluted proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE, and specific bands present in the experimental sample but absent in the control are excised and identified using mass spectrometry.

Protocol for a Phenotypic Screen (Starting Point for Deconvolution)

This protocol outlines a cell-based phenotypic screen to identify compounds that rescue a disease-relevant phenotype [9].

- Cell Model Engineering: Develop a stable, disease-relevant cell line. For example, a human cell line (e.g., HEK293) engineered to express a mutated gene associated with a neurodegenerative disease under the control of an inducible promoter. The system may also include a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase) to measure a specific pathway output.

- Compound Library Screening: Plate the engineered cells in multi-well plates. Induce the disease phenotype and simultaneously treat the cells with a diverse library of small molecules at a single concentration. Incubate for a defined period.

- Phenotypic Readout: Measure the phenotypic endpoints. This could include:

- Reporter Gene Activity: Quantify luminescence or fluorescence to assess pathway modulation.

- Cell Viability: Use a toxicity assay (e.g., MTT, ATP-based) to measure cell death or survival.

- High-Content Imaging: Analyze morphological changes using automated microscopy.

- Hit Confirmation: Identify "hit" compounds that significantly rescue the disease phenotype. Re-test these hits in dose-response experiments to confirm activity and determine potency (IC50/EC50).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of target discovery and deconvolution relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for target identification

| Research Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Chromatography Resins | Provides a solid support for covalent attachment of small molecule ligands for affinity purification. | Affinity Chromatography [12] |

| cDNA Phage/MRNA Display Libraries | A diverse collection of phage or mRNA-fusion molecules displaying a vast repertoire of peptides or protein fragments for interaction screening. | Expression Cloning [12] [7] |

| Protein Microarrays | A slide printed with thousands of individually purified proteins, enabling high-throughput analysis of protein-ligand interactions. | Protein Microarray Screening [12] [7] |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Collections of synthetic siRNAs or plasmid-based shRNAs designed to knock down the expression of specific target genes. | Target Validation & Functional Genetics [6] [8] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Small molecules that covalently bind to the active site of enzymes, featuring a tag for detection/enrichment. They report on enzymatic activity, not just abundance. | Chemoproteomics; Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) [10] |

| Label-Free Detection Reagents | Reagents and kits for techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) that detect biomolecular interactions without the need for labels, providing kinetic data. | Biophysical Validation of Target Engagement |

Within the rigorous framework of drug discovery, target discovery and target deconvolution are not opposing but rather complementary strategies. Target discovery provides a focused, rational path forward when the disease biology is sufficiently understood. In contrast, target deconvolution offers an unbiased, systems-level entry point to uncover novel biology and therapeutics, which is particularly valuable for complex or poorly understood diseases [6] [9].

The integration of both approaches—using phenotypic screening to identify compelling chemical starting points and subsequent target deconvolution to illuminate their mechanism of action—creates a powerful, iterative cycle for innovation. This combined strategy leverages the strengths of each method, increasing the likelihood of identifying truly novel and efficacious therapeutic targets and ultimately bringing safer and more effective medicines to patients.

The Critical Role of Target Validation in Reducing Clinical Attrition

The process of developing a new therapeutic is a high-stakes endeavor marked by substantial financial investment and a dishearteningly high rate of failure. Clinical attrition—the failure of drug candidates during clinical testing—remains the most significant bottleneck in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D). Recent analyses of the industry reveal a stark reality: the overall likelihood of approval (LOA) for a drug candidate entering Phase I trials has fallen to approximately 6–7%, a decline from about 10% in 2014 [13]. This means that more than 9 out of 10 investigational therapies that enter human testing will never reach the market. This attrition is not distributed evenly; Phase II trials consistently emerge as the single greatest hurdle, with only about 28% of all programs successfully advancing beyond this point. The root cause of a majority of these failures is a lack of efficacy or unanticipated safety issues, both of which are fundamentally linked to inadequate understanding and validation of the drug target itself [13]. Therefore, within the broader drug discovery pipeline—which encompasses target identification, target validation, hit discovery, lead optimization, and clinical testing—the phase of target validation serves as the critical foundation. Robust target validation is the key to derisking subsequent R&D stages, enhancing productivity, and improving the return on investment for the entire pharmaceutical industry.

Quantitative Landscape of Clinical Attrition Across Modalities

An examination of attrition rates across different drug modalities provides a clear, data-driven illustration of the problem and highlights opportunities for improvement. The following tables summarize phase transition success rates and the overall likelihood of approval for major therapeutic modalities, based on recent industry data [13].

Table 1: Phase Transition Success Rates by Modality (%) [13]

| Modality | Phase I → II | Phase II → III | Phase III → Submission | Regulatory Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules | 52.6 | 28.0 | 57.0 | 89.5 |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | 54.7 | 51.9 | 68.1 | ~95.0 |

| Protein Biologics (non-mAbs) | 51.6 | 50.0 | 69.0 | 89.7 |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | ~41.5 | ~42.5 | 66.7 | ~100.0 |

| Peptides | 52.3 | 41.9 | 60.0 | 90.0 |

| Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs) | ~50.0 | 46.2 | 65.0 | ~100.0 |

Table 2: Overall Likelihood of Approval (LOA) from Phase I [13]

| Modality | Overall LOA (%) |

|---|---|

| Small Molecules | ~6.0 |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | 12.1 |

| Protein Biologics (non-mAbs) | 9.4 |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | ~7.5 (Very high regulatory success) |

| Peptides | 8.0 |

| Oligonucleotides (RNAi) | 13.5 |

| Cell and Gene Therapies (CAR-T) | 17.3 |

The data reveals several critical insights. First, Phase II is the primary attrition point for nearly all modalities, underscoring a widespread failure in accurately predicting efficacy in patient populations based on preclinical and early clinical data. Second, monoclonal antibodies and other biologics generally enjoy a higher probability of success than small molecules, likely due to their inherent target specificity. Finally, novel modalities like cell and gene therapies, while complex, can achieve remarkably high LOAs for specific indications, demonstrating that overcoming biological complexity with rigorous science is possible [13]. The high failure rates, particularly in Phase II, are frequently attributed to insufficient evidence linking the target to the human disease pathology—a gap that stringent target validation aims to fill.

The Foundation: Target Identification and Validation

Integrating Target Identification with Validation

In modern drug discovery, the lines between target identification and validation are increasingly blurred, with computational biology playing a pivotal role. Target identification involves pinpointing a biological molecule (typically a protein) that is causally involved in a disease process and is amenable to therapeutic modulation. Validation is the rigorous process of establishing that modulating this target will produce a desired therapeutic effect with an acceptable safety margin [14].

A powerful methodology for target identification is subtractive proteomics, a bioinformatics-driven approach that systematically filters a pathogen's or human's entire proteome to find ideal targets. As demonstrated in research for novel MRSA therapeutics, this workflow involves [15]:

- Paralogous Protein Removal: Using tools like CD-HIT to remove duplicate protein sequences, ensuring a non-redundant dataset [15].

- Non-Homology Analysis: Performing BLASTp against the human proteome to filter out proteins with significant homology, minimizing the risk of off-target toxicity [15].

- Physicochemical Characterization: Using tools like the Expasy ProtParam server to analyze properties like molecular weight and instability index, selecting only stable proteins for further consideration [15].

- Subcellular Localization: Employing predictors like PSORTb to identify cytoplasmic proteins, which are often essential for pathogen survival and thus excellent targets [15].

- Druggability and Essentiality Analysis: Screening against databases like DrugBank and the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) to assess whether the protein is known or predicted to bind drug-like molecules. This is combined with virulence factor analysis to ensure the target is critical to the disease mechanism [15].

This integrated computational pipeline efficiently narrows thousands of potential proteins down to a handful of high-confidence candidate targets for experimental validation.

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Following computational identification, experimental validation is essential to confirm the target's biological role. Key protocols include:

- Gene Knockdown/Knockout (in vitro): Utilizing siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR-Cas9 to deplete or knockout the target gene in relevant cell-based disease models (e.g., cancer cell lines, primary cells). A significant change in phenotype (e.g., reduced cell proliferation, altered cytokine secretion) upon target knockdown confirms its functional role. Validation requires measuring mRNA (qRT-PCR) and protein (Western blot) levels to confirm knockdown and assess downstream pathway effects [15].

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis: Mapping the candidate target within a larger PPI network to identify central "hub" proteins critical to disease pathways. This can be achieved through co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by mass spectrometry. The network is analyzed using clustering algorithms to identify functional modules, and targets are prioritized based on their connectivity and centrality within the disease-associated network [14].

- Binding Affinity and Functional Assays: For targets where a lead molecule exists, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can be used to determine the binding affinity (KD). This is coupled with functional assays (e.g., enzyme activity assays, cell-based reporter assays) to confirm that binding translates to functional modulation of the target [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental path from initial proteome to a validated target.

A Framework for AI-Driven Target Validation

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing target validation by providing deeper insights from complex biological data. A proposed AI-driven framework leverages multiple advanced computational techniques to create a more predictive and efficient validation pipeline [14].

- Target Identification with Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs): GCNs are exceptionally suited for analyzing Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks. They learn from the graph structure to generate embeddings for each protein node, capturing its functional context. In this model, protein features are extracted using methods like DL2Vec and processed through a GCN, while drug features are obtained from SMILES strings and processed by a Deep Neural Network (DNN). The model then calculates a similarity score between the drug and protein embeddings to predict the strength and likelihood of their interaction, thereby identifying and prioritizing the most promising targets within a complex biological network [14].

- Hit Identification with 3D-Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs): Once a target is identified, 3D-CNNs can predict the binding affinity of small molecules by analyzing their 3D structural data and the target's binding site. These models assess molecular shape, flexibility, and electrostatic interactions, providing a high-resolution view of potential ligand-receptor interactions and enabling virtual screening of compound libraries with high accuracy [14].

- Lead Optimization with Reinforcement Learning (RL): After identifying hit compounds, Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms can be employed to optimize their chemical structures. The RL agent iteratively modifies molecular structures, rewarding improvements in desired properties such as potency, solubility, and safety (ADMET profiles), thereby efficiently navigating the vast chemical space to generate superior lead candidates [14].

The following diagram outlines the architecture of this integrated AI-driven framework for drug discovery and target validation.

Successful target validation relies on a suite of specific reagents and computational tools. The following table details key resources essential for the experiments and analyses described in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Target Validation |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Used for precise gene knockout in cell lines to confirm the target's essential role in a disease phenotype through functional loss-of-function studies. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Enable transient or stable gene knockdown for initial, high-throughput functional screening of multiple candidate targets. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Critical reagents for techniques like Western Blot (to confirm protein expression/knockdown), Immunofluorescence (for subcellular localization), and Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) (to identify interacting protein partners). |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | A computational tool (e.g., using PyTorch Geometric) for analyzing PPI networks to identify and prioritize critical hub proteins as high-value targets. |

| 3D-Convolutional Neural Network (3D-CNN) | A deep learning model used for predicting the 3D binding affinity of small molecules to a target protein of known structure, accelerating virtual screening. |

| ADMET Prediction Models | Computational models (e.g., using RNNs on sequential data or other ML algorithms) that predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity profiles of lead compounds early in the process, reducing late-stage attrition [14]. |

The crisis of clinical attrition, particularly the high rate of failure in Phase II trials, is a direct reflection of the challenges in target validation. As the data shows, even the most promising modalities face significant hurdles, underscoring the non-negotiable need for a robust foundational understanding of drug targets. The path forward requires a disciplined, integrated approach that leverages computational power—from subtractive proteomics and AI-driven PPI analysis to predictive ADMET modeling—alongside rigorous experimental biology. By committing to deeper, more causative target validation, the drug discovery industry can transform the existing paradigm. This will enable the consistent selection of targets with a strong scientific rationale, ultimately leading to a higher probability of clinical success, reduced R&D costs, and the accelerated delivery of effective new therapies to patients.

The identification and validation of novel biological targets is a critical, foundational step in the drug discovery pipeline. With the exponential growth of scientific literature and biological data, systematic computational approaches have become indispensable for navigating this complex information landscape. Literature and database mining represent a suite of methodologies that leverage natural language processing (NLP), data integration, and statistical analysis to extract biologically meaningful patterns and relationships from vast public repositories. For researchers and drug development professionals, these techniques transform unstructured text and disparate data points into actionable biological insights, facilitating the transition from purely academic exploration to the initiation of targeted drug development programs. The application of these methods is particularly crucial for understanding target biology, establishing links between targets and disease states, and anticipating potential challenges such as safety issues and druggability [16] [17].

The volume of molecular biological information has expanded dramatically in the post-genomic era, creating a significant challenge for researchers aiming to maintain comprehensive knowledge in their domains [18] [19]. This data deluge coincides with a shift in biological research from studying individual genes and proteins to analyzing entire systems, necessitating tools that can handle this complexity [16]. While information retrieval tools like PubMed are the most commonly used literature-mining methods among biologists, the field has advanced considerably to include sophisticated techniques for entity recognition, relationship extraction, and integration with high-throughput experimental data [16]. These advancements enable not only the annotation of large-scale data sets but also the generation of novel hypotheses based on existing knowledge, positioning literature and database mining as a powerful discovery engine in modern biomedical research [16].

Core Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Information Retrieval and Entity Recognition

The foundation of any literature mining workflow begins with effective information retrieval (IR) and entity recognition (ER). While ad-hoc IR methods, such as keyword searches in PubMed, offer flexibility, more advanced text categorization systems using machine learning can provide superior accuracy by training on pre-classified document sets [20]. A critical enhancement to basic retrieval is automatic query expansion, which incorporates stemming (e.g., "yeast" and "yeasts"), synonyms, and abbreviations (e.g., "S. cerevisiae" for "yeast") to improve recall, with ontologies now being used to make complex inferences [20].

Following retrieval, entity recognition focuses on identifying and classifying relevant biological concepts within the text. This process involves two distinct challenges: name recognition (finding the words that are names) and entity identification (determining the specific biological entities to which they refer) [20]. Advanced systems employ curated synonym lists that account for orthographic variations (e.g., "CDC28", "Cdc28", "cdc28") and leverage contextual clues to resolve ambiguities where the same term may refer to different entities across species or to common English words [20]. Modern implementations like GPDMiner (Gene, Protein, and Disease Miner) utilize deep learning architectures, including Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), to achieve state-of-the-art performance in recognizing complex biomedical entities from text [21].

Relationship Extraction and Semantic Analysis

Once entities are identified, the next critical step is extracting the relationships between them. Several methodological approaches exist, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Co-occurrence analysis, a statistical approach, identifies relationships based on the frequency with which entities appear together in the same documents or sentences. While this method offers good recall, it produces symmetric relationships and does not specify the nature of the interaction [20]. For example, a sentence mentioning "Clb2-bound Cdc28 phosphorylated Swe1" would generate pairwise associations (Clb2-Cdc28, Clb2-Swe1, Cdc28-Swe1) without capturing directionality or mechanism [20].

More sophisticated Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques parse and interpret full sentences to extract specific, directed relationships. A typical NLP pipeline includes tokenization, entity recognition with synonyms, part-of-speech tagging, and semantic labeling using dictionaries of regular expressions [20]. This approach enables the extraction of complex, directed interactions, such as "Cdc28 phosphorylates Swe1," offering superior precision though often with more limited recall [20]. Tools like GPDMiner integrate these advanced NLP capabilities with statistical methods to provide comprehensive relationship extraction, subsequently visualizing the results as interconnected networks that researchers can explore and analyze [21].

Integration with Experimental Data and Network Analysis

The full potential of literature mining is realized when integrated with other data types, particularly large-scale experimental datasets. This integrative approach enables the annotation of high-throughput data and facilitates true biological discovery by connecting textual knowledge with empirical findings [16]. Protein-protein interaction networks serve as particularly effective frameworks for unifying diverse experimental data with knowledge extracted from the biomedical literature [16].

Methodologies for data integration have been successfully applied to several challenging biological problems. For ranking candidate genes associated with inherited diseases, literature-derived information can be combined with genomic mapping data to prioritize genes within a chromosomal region linked to a disease [16] [20]. Similarly, associating genes with phenotypic characteristics can be achieved by linking entities through shared contextual patterns in the literature [16]. The GOT-IT recommendations emphasize that such computational assessments, including analysis of target-related safety issues and druggability, are crucial for robust target validation and facilitating academia-industry collaboration in drug development [17].

Effective literature and database mining requires leveraging a diverse ecosystem of specialized databases and resources. The tables below categorize essential databases for drug-target and adverse event information, as well as text mining and analysis tools.

Table 1: Key Databases for Drug-Target and Adverse Event Information

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Use Case in Target Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-ARDIS [22] | Target-Adverse Reaction associations | Statistically validated protein-ADR relationships; Over 3000 ADRs & 248 targets | Identifying potential safety liabilities early in development |

| Drug-Target Commons [22] | Drug-target interactions | Crowdsourced binding data | Assessing target engagement and polypharmacology |

| STITCH [22] | Chemical-protein interactions | Integration of experimental and predicted interactions | Understanding a compound's potential protein targets |

| SIDER4.1 [22] | Drug-ADR relationships | Mined from FDA drug labels | Complementing target safety profiles |

| OFFSIDES [22] | Drug-side effect associations | Manually curated database | Identifying off-target effects |

| Radiation Genes [23] | Radiation-responsive genes | Transcriptome alterations from microarray data | Target identification for radioprotection |

Table 2: Text Mining and Analysis Tools

| Tool/Platform | Methodology | Unique Features | Output/Visualization |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPDMiner [21] | BERT-based NER & RE, Dictionary/statistical analysis | Integrates PubMed and US Patent databases; Relationship analysis based on influence index | Excel, images, network visualizations of gene-protein-disease relationships |

| PubNet [24] | Network analysis | Extracts relationships from PubMed queries | Graphical visualization and topological analysis of publication networks |

| Semantic Medline [24] | Natural language processing | Extracts semantic predications from PubMed searches | Network of interrelated concepts |

| Coremine [24] | Text-mining | Provides overview of topic by clustering important terms | Navigable relationship network for concept exploration |

| Cytoscape [23] | Network visualization and integration | Plugin architecture (e.g., ClueGO, Agilent Literature Search) | Customizable biological network graphs |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Establishing Statistically Validated Target-ADR Associations

The T-ARDIS database provides a robust methodology for identifying significant associations between protein targets and adverse drug reactions (ADRs), a critical consideration in early target assessment [22].

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Resources: Server with sufficient processing power and memory for statistical analysis and database management.

- Data Sources: Drug-target interaction data (from Drug-Target Commons, STITCH); Drug-ADR data (from FAERS, MEDEFFECT, SIDER, OFFSIDES).

- Standardization Vocabularies: MedDRA terminology for ADRs (PT level); RxNorm for drug standardization; UNIPROT for target identification.

- Software: Statistical computing environment (e.g., R, Python with scientific libraries).

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Drug-Target Data: Compile drug-protein interactions from Drug-Target Commons and STITCH. Resolve protein identifiers to UNIPROT IDs.

- Drug-ADR Data: Extract drug-ADR associations from FAERS, MEDEFFECT, SIDER, and OFFSIDES. Standardize drug names to RxNorm concepts and ADR terms to MedDRA Preferred Terms (PT).

- FAERS/MEDEFFECT Curation: Implement a standardization pipeline for FAERS and MEDEFFECT to address data heterogeneity, including removal of duplicates and correction of misspelled drug names [22].

Data Filtering:

- Filter out non-specific ADRs by excluding those belonging to the following MedDRA System Organ Classes (SOCs): "General disorders and administration site conditions" and "Injury, poisoning and procedural complications" [22].

Statistical Validation:

- Apply the method described by Kuhn et al. to identify statistically significant protein-ADR associations [22].

- Use contingency tables and statistical tests (e.g., Fisher's exact test) to calculate p-values for each target-ADR pair, correcting for multiple testing (e.g., using q-values).

- Retain only associations that meet a predefined significance threshold (e.g., q-value < 0.05).

Database Integration and Querying:

- Store validated associations in a structured database (e.g., T-ARDIS).

- Implement search functionality allowing queries by drug name, target UNIPROT ID, gene name, or ADR (MedDRA term).

Interpretation and Analysis: The output is a statistically validated association between a protein target and an adverse reaction. This association suggests that modulation of the target may lead to the observed effect. These results should be considered as hypotheses generating potential safety liabilities, requiring further experimental validation in relevant biological systems.

Protocol: Knowledge-Driven Target Discovery for Radioprotection

This protocol, adapted from a study on radioprotectants, outlines a text-mining and network-based approach to identify novel drug targets or repurposing opportunities [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Cytoscape with plugins (Agilent Literature Search, ClueGO).

- Databases: PubMed, Radiation Genes database, Drug Gene Interaction database (DGIdb).

Procedure:

- Target Identification from Literature:

- Use the Agilent Literature Search plugin in Cytoscape.

- Execute a search query for known radioprotectors (e.g., "Amifostine radioprotection").

- Extract gene and protein targets mentioned in the resulting abstracts to create a preliminary target list.

Validation against Radiation-Specific Database:

- Cross-reference the extracted gene list with the Radiation Genes database to identify genes with established roles in radiation response.

Linking Targets to Drugs:

- Query the Drug Gene Interaction database (DGIdb) with the refined gene list.

- Identify existing drugs or molecules in clinical trials that interact with these candidate targets.

Functional and Pathway Analysis:

- Use the ClueGO Cytoscape plugin to perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, pathway mapping) on the final target set.

- Identify overrepresented biological processes (e.g., apoptosis, DNA repair, proliferative pathways) to understand mechanistic context.

Interpretation and Analysis: This workflow generates a list of candidate targets with prior evidence of involvement in radiation response and known pharmacological modulators. The functional analysis provides insight into the biological processes these targets regulate, helping to prioritize candidates based on their role in critical pathways relevant to the disease pathology.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting the complex relationships and high-dimensional data generated through literature and database mining. Information visualization techniques leverage the high bandwidth of human vision to manage large amounts of information and facilitate the recognition of patterns and trends that might otherwise remain hidden [18]. Below are pathway diagrams illustrating core workflows in the field.

Diagram 1: Literature Mining Core Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential process from information retrieval to knowledge discovery, highlighting key stages including entity recognition, relationship extraction, and statistical validation.

Diagram 2: Integrative Analysis for Target Safety. This data flow diagram illustrates how disparate data sources are integrated and statistically analyzed to generate validated target-safety associations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Literature Mining

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Target ID | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/Medline | Literature Database | Primary repository for biomedical literature searches | >30 million citations; Keyword/MESH search; Entrez Programming Utilities (E-utilities) for API access |

| GPDMiner | Text-Mining Platform | Extracts and relates genes, proteins, and diseases from text | BERT-based NER; Relation Extraction; Integration of statistical and dictionary methods |

| Cytoscape | Network Visualization | Visualizes and analyzes molecular interaction networks | Plugin architecture; Integration with literature search plugins; Functional enrichment analysis |

| T-ARDIS | Specialized Knowledgebase | Identifies statistically validated target-adverse reaction associations | Pre-computed safety liability associations; Links to source databases |

| MedDRA | Controlled Terminology | Standardizes adverse event reporting | Hierarchical medical terminology; 5 levels from SOC to LLT; Essential for data normalization |

| RxNorm | Standardized Nomenclature | Normalizes drug names across databases | Provides normalized names for clinical drugs; Links to many drug vocabularies |

Literature and database mining has evolved from a supplementary information retrieval tool to a fundamental component of modern target identification and validation strategies. By systematically extracting knowledge from vast public resources, these approaches enable researchers to build robust biological narratives around potential drug targets, incorporating critical aspects such as disease linkage, functional pathways, and potential safety concerns. The integration of advanced computational linguistics with statistical and network analysis methods provides a powerful framework for transforming unstructured text into structured, actionable knowledge.

As the field continues to mature, the most promising applications lie in the seamless integration of text-derived knowledge with experimental data types. This synergy, essential for hypothesis generation and validation, is a key theme in contemporary drug discovery, as emphasized by initiatives like the GOT-IT recommendations which aim to strengthen the translational path [17]. For drug development professionals, mastering these resources and methodologies is no longer optional but necessary for navigating the complexity of biological systems and improving the efficiency and success rate of bringing new therapeutics to patients.

From Concept to Candidate: A Toolkit of Identification and Validation Methods

Target identification is a crucial foundational stage in the discovery and development of new therapeutic agents, enabling researchers to understand the precise mode of action of drug candidates [25] [26]. By discovering the exact molecular target of a biologically active compound—whether it be an enzyme, cellular receptor, ion channel, or transcription factor—researchers can better optimize drug selectivity, reduce potential side effects, and enhance therapeutic efficacy for specific disease conditions [25] [6]. The success of any given therapy depends heavily on the efficacy of target identification, and much of the progress in drug development over past decades can be attributed to advances in these technologies [25] [26].

Within the framework of experimental biological assays, target identification strategies can be broadly classified into two main categories: affinity-based pull-down methods and label-free techniques [25] [26]. Affinity-based approaches rely on chemically modifying small molecules with tags to selectively isolate their binding partners, while label-free methods utilize small molecules in their native state to identify targets through biophysical or functional changes [25] [27]. The strategic selection between these approaches is essential to the success of any drug discovery program and must be carefully considered based on the specific project requirements, compound characteristics, and available resources [25] [26]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of these core methodologies, their experimental protocols, applications, and integration within modern drug discovery workflows.

Affinity-Based Pull-Down Methods

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Affinity purification represents a cornerstone method for identifying the protein targets of small molecules. This technique involves conjugating the tested compound to an affinity tag (such as biotin) or immobilizing it on a solid support (such as agarose beads) to create a probe molecule that can be incubated with cells or cell lysates [25] [26]. After incubation, the bound proteins are purified using the affinity tag, then separated and identified using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and mass spectrometry [25] [26]. This approach provides a powerful and specific tool for studying interactions between small molecules and proteins, with particular utility for compounds with complex structures or tight structure-activity relationships [25].

The general workflow for affinity-based pull-down assays involves multiple critical steps that ensure specific target capture and identification. As illustrated below, the process begins with probe preparation and proceeds through incubation, washing, elution, and final analysis:

Figure 1: General workflow for affinity-based pull-down assays

Key Affinity-Based Techniques

On-Bead Affinity Matrix Approach

The on-bead affinity matrix approach identifies target proteins of biologically active small molecules using a solid support system [25] [26]. In this method, a linker such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) covalently attaches a small molecule to a solid support (e.g., agarose beads) at a specific site designed to preserve the molecule's original biological activity [25]. The small molecule affinity matrix is then exposed to a cell lysate containing potential target proteins. Any protein that binds to the matrix is subsequently eluted and collected for identification, typically via mass spectrometry [25]. This approach has been successfully adopted for numerous compounds including KL001 (targeting cryptochrome), Aminopurvalanol (targeting CDK1), and BRD0476 (targeting USP9X) [25].

Biotin-Tagged Approach

Biotin, a small molecule with strong binding affinity for the proteins avidin and streptavidin, is commonly used in affinity-based techniques due to its favorable biochemical properties [25] [26]. In this method, a biotin molecule is attached to the small molecule of interest through a chemical linkage, and the biotin-tagged small molecule is incubated with a cell lysate or living cells containing the target proteins [26]. The target proteins are captured on a streptavidin-coated solid support, then analyzed using SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry after appropriate washing steps [25] [26]. The biotin-tagged approach was used successfully to identify activator protein 1 (AP-1) as the target protein of PNRI-299 and vimentin as the target of withaferin [25].

While this approach offers advantages of low cost and simple purification, it has notable limitations. The high affinity of the biotin-streptavidin interaction requires harsh denaturing conditions (such as SDS buffer at 95-100°C) to release bound proteins, which may alter protein structure or activity [26]. Additionally, attaching biotin to a small molecule can affect cellular permeability and may confound phenotypic results in living cells [26].

Photoaffinity Tagged Approach

Photoaffinity labelling (PAL) represents an advanced affinity-based technique where a chemical probe covalently binds to its target upon exposure to light of specific wavelengths [26]. The probe design incorporates three key elements: a photoreactive group, a linker connecting this group to the small molecule, and an affinity tag [26]. When activated by light, the photoreactive moiety generates a highly reactive intermediate that forms a permanent covalent bond with the target molecule, enabling subsequent isolation and characterization [26].

Common photoreactive groups used in PAL include:

- Phenylazides: Form nitrene upon irradiation

- Phenyldiazirines: Form carbene upon irradiation, with trifluoromethyl derivatives offering superior stability

- Benzophenones: Form diradical upon irradiation

Aryldiazirines, particularly trifluoromethylphenyl-diazirines, have become the most widely used photoreactive groups due to their excellent chemical stability and ability to generate highly reactive carbene intermediates [26]. The PAL approach offers high specificity, sensitivity, and compatibility with diverse experimental designs, and has been successfully employed to identify targets for compounds including pladienolide (SF3b), kartogenin (filamin A), and venetoclax (multiple targets including VDAC2) [25].

Research Reagent Solutions for Affinity-Based Methods

Table 1: Essential research reagents for affinity-based pull-down assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Supports | Agarose beads, Magnetic beads, Sepharose resin | Provide matrix for immobilizing bait molecules or antibodies |

| Affinity Tags | Biotin, Polyhistidine (His-tag), GST-tag | Enable specific capture and purification of target complexes |

| Binding Partners | Streptavidin/avidin, Anti-His antibodies, Glutathione | High-affinity recognition of tags for complex isolation |

| Linkers | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Photoactivatable linkers | Spacer molecules connecting small molecules to tags or solid supports |

| Elution Agents | SDS buffer, Free biotin, Imidazole, Competitive analytes | Disrupt specific interactions to release captured targets |

| Detection Methods | SDS-PAGE, Mass spectrometry, Western blotting | Identify and characterize isolated proteins |

Label-Free Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Label-free methodologies have emerged as powerful alternatives to affinity-based approaches, enabling target identification without requiring chemical modification of the small molecule [25] [27]. These techniques exploit the energetic and biophysical features that accompany the association of macromolecules with drugs in their native forms, preserving the natural structure and function of both compound and target [27]. By eliminating the need for tags or labels, these methods avoid potential artifacts introduced by molecular modifications that might alter bioactivity, cellular permeability, or binding characteristics [25] [26].

Label-free approaches are particularly valuable for studying natural products and other complex molecules that are difficult to modify chemically without compromising their biological activity [27]. The conceptual workflow for label-free target identification involves monitoring functional or stability changes in the proteome upon compound treatment, followed by target validation through orthogonal methods:

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for label-free target identification

Key Label-Free Techniques

Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS)

The Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) method exploits the principle that a protein's susceptibility to proteolysis is often reduced when bound to a small molecule [25]. In this technique, cell lysates are incubated with the drug candidate or vehicle control, followed by exposure to a nonspecific protease [25]. Proteins that are stabilized by drug binding show reduced proteolytic degradation compared to untreated controls. These stabilized proteins can be separated by electrophoresis and identified through mass spectrometry [25]. DARTS has been successfully applied to identify targets for numerous compounds, including resveratrol (eIF4A), rapamycin (mTOR and FKBP12), and syrosingopine (α-enolase) [25]. A significant advantage of DARTS is its minimal requirement for compound quantity and the fact that it uses unmodified compounds, preserving their native structure and function [25].

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) measures the thermal stabilization of target proteins upon ligand binding in a cellular context [25]. Based on the principle that small molecule binding often increases a protein's thermal stability, CETSA involves heating compound-treated cells to different temperatures, followed by cell lysis and separation of soluble proteins from precipitated aggregates [25]. The stabilized target proteins remain in the soluble fraction at temperatures where they would normally denature and precipitate in untreated cells. These stabilized proteins can be detected and quantified using immunoblotting or mass spectrometry-based proteomics [25]. CETSA has been effectively used to identify targets for compounds including an aurone derivative (Class III PI3K/Vps34), ferulin C (tubulin), and 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (STAT3) [25].

Stability of Proteins from Rates of Oxidation (SPROX)

Stability of Proteins from Rates of Oxidation (SPROX) utilizes chemical denaturation and oxidation kinetics to detect protein-ligand interactions [25]. This method measures the rate of methionine oxidation by hydrogen peroxide in increasing concentrations of a chemical denaturant such as urea or guanidine hydrochloride [25]. Protein-drug interactions alter the thermodynamic stability of the target protein, resulting in shifted denaturation curves that can be detected through quantitative mass spectrometry [25]. SPROX has been successfully employed to identify YBX-1 as the target of tamoxifen and filamin A as a target of manassantin A [25].

Label-Free Quantification Mass Spectrometry

Label-free quantification (LFQ) mass spectrometry has become a cornerstone of modern proteomics for comparing protein abundance across multiple biological samples without isotopic or chemical labels [28] [29]. This approach quantifies proteins based on either spectral counting (number of MS/MS spectra per peptide) or chromatographic peak intensity (area under the curve in extracted ion chromatograms) [28]. Advanced computational algorithms then identify peptides via database matching and quantify abundance changes between samples [28] [29].

Key mass spectrometry acquisition methods for LFQ include:

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): Selects the most intense ions for fragmentation, ideal for exploratory proteome discovery and building spectral libraries [28]

- Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA): Fragments all ions in preset m/z windows, offering greater reproducibility and comprehensive datasets suitable for large sample cohorts [28]

- Four-Dimensional DIA (4D-DIA): Incorporates ion mobility separation for enhanced depth, selectivity, and quantification, particularly beneficial for highly complex or limited samples [28]

Research Reagent Solutions for Label-Free Methods

Table 2: Essential research reagents for label-free target identification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolysis Reagents | Thermolysin, Pronase, Proteinase K | Nonspecific proteases for DARTS experiments |

| Thermal Stability Reagents | Lysis buffers, Protease inhibitors | Maintain protein integrity during CETSA thermal challenges |

| Oxidation Reagents | Hydrogen peroxide, Methionine | Chemical modifiers for SPROX methodology |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Trypsin, Urea, Iodoacetamide | Protein digestion, denaturation, and alkylation for LFQ |

| Chromatography Materials | C18 columns, LC solvents | Peptide separation prior to mass spectrometry |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PEAKS Q, MaxQuant, Spectral libraries | Data processing, quantification, and statistical analysis |

Comparative Analysis and Technical Protocols

Strategic Comparison of Methodologies

The selection between affinity-based and label-free approaches requires careful consideration of their respective advantages, limitations, and appropriate application contexts. Both methodological families offer distinct strengths that make them suitable for different stages of the target identification process or for compounds with specific characteristics.

Table 3: Comparative analysis of affinity-based and label-free approaches

| Parameter | Affinity-Based Pull-Down | Label-Free Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Modification | Requires chemical modification with tags | Uses native, unmodified compounds |

| Throughput Capacity | Moderate, limited by conjugation steps | Generally higher, especially for CETSA and DARTS |

| Sensitivity | High for strong binders | Varies; can detect weak or transient interactions |

| Specificity | Potential for false positives from nonspecific binding | Context-dependent; functional consequences measured |

| Technical Complexity | High, requires chemical expertise | Moderate to high, depending on method |

| Physiological Relevance | Limited for in vitro applications using cell lysates | Higher for cellular methods like CETSA |

| Key Applications | Target identification for modified compounds, proof of direct binding | Natural products, fragile compounds, early screening |

| Resource Requirements | Significant for probe synthesis and validation | Advanced instrumentation for proteomics or biophysics |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Biotin-Tagged Pull-Down Assay

- Probe Preparation: Conjugate the small molecule of interest to biotin using appropriate chemistry, ensuring the modification site does not interfere with biological activity [25] [26]

- Cell Lysis: Prepare cell lysate in appropriate lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors to maintain protein integrity [26]

- Pre-clearing: Incubate lysate with streptavidin beads alone to reduce nonspecific binding, then collect supernatant [26]

- Binding Reaction: Incubate biotinylated probe with pre-cleared lysate for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation [25]

- Capture: Add streptavidin-coated magnetic or agarose beads to the mixture and incubate for an additional 1 hour at 4°C [26]

- Washing: Pellet beads by gentle centrifugation and wash 3-5 times with lysis buffer to remove unbound proteins [26] [30]

- Elution: Elute bound proteins by boiling in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer or competitive elution with excess free biotin [26]

- Analysis: Separate eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining or Western blotting, or process for identification by mass spectrometry [25] [26]

Standard Protocol for Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

- Compound Treatment: Incubate living cells with compound of interest or vehicle control for appropriate time period [25]

- Heat Challenge: Aliquot cell suspensions and heat to different temperatures (e.g., 37-65°C) for 3-5 minutes [25]

- Cell Lysis: Freeze-thaw cycles or mechanical disruption to release soluble proteins [25]

- Separation: Centrifuge at high speed to separate soluble proteins (supernatant) from aggregated proteins (pellet) [25]

- Detection: Analyze soluble fractions by Western blotting for specific proteins or by quantitative mass spectrometry for proteome-wide screening [25]

- Data Analysis: Calculate melting curves and determine ΔTm values (temperature shift) for stabilized proteins [25]

Standard Protocol for Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS)

- Lysate Preparation: Generate cell lysate in nondenaturing buffer without protease inhibitors [25]

- Compound Treatment: Divide lysate and incubate with compound or vehicle control for 1 hour at room temperature [25]

- Proteolysis: Add pronase or thermolysin at various dilutions and incubate briefly (typically 10-30 minutes) [25]

- Reaction Termination: Add protease inhibitors or SDS-PAGE sample buffer to stop proteolysis [25]

- Analysis: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and visualize by silver staining or Western blotting, or process for mass spectrometry analysis [25]

- Identification: Compare proteolysis patterns between treated and untreated samples to identify stabilized proteins [25]

Integration in Drug Discovery Workflows

Complementary Approaches in Target Identification