Structure-Based Drug Design: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

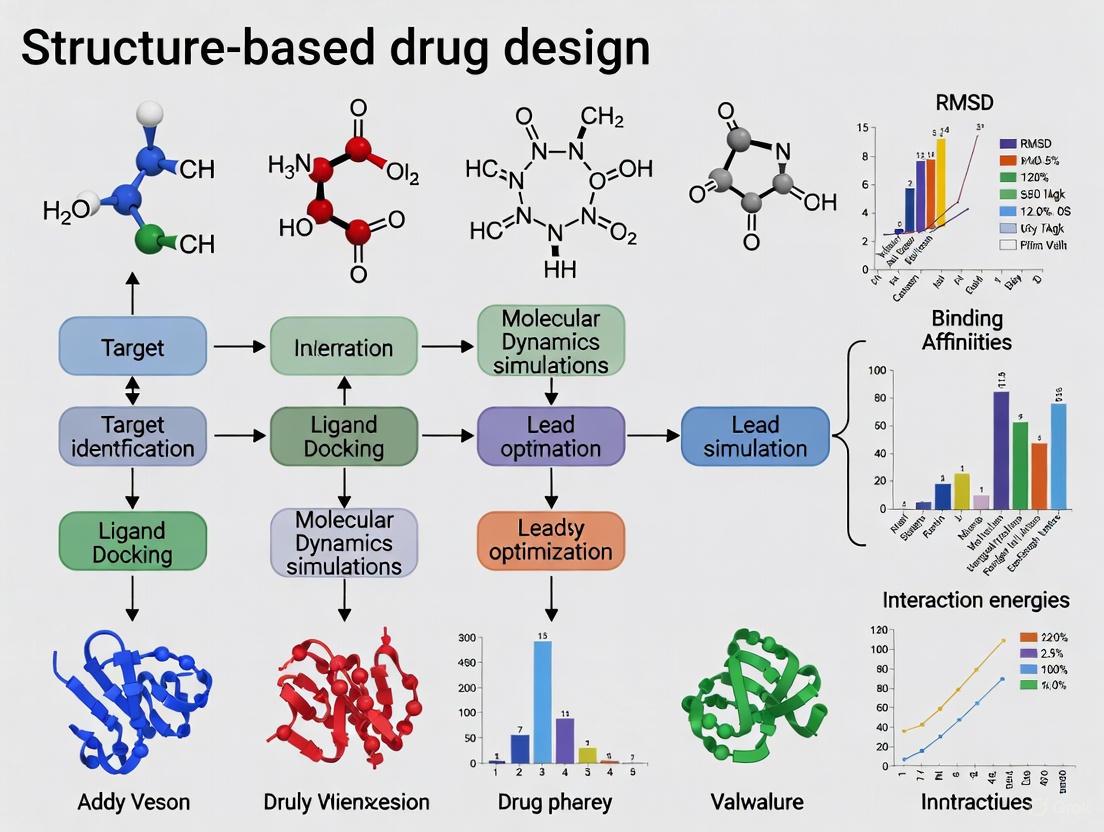

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD), a cornerstone of modern rational drug discovery.

Structure-Based Drug Design: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD), a cornerstone of modern rational drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of SBDD, from obtaining 3D protein structures via X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, and computational prediction. It delves into core methodological applications like molecular docking and virtual screening, and examines cutting-edge advances, including equivariant diffusion and multi-modal AI models that generate novel drug candidates. The content also addresses persistent challenges such as scoring function accuracy and protein flexibility, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it evaluates validation frameworks and comparative performance of various SBDD approaches, synthesizing key takeaways to illuminate future directions for accelerating therapeutic development.

The Bedrock of SBDD: Core Principles and Structural Techniques

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development, utilizing the three-dimensional structural information of biological targets to guide the discovery and optimization of novel therapeutics. This approach has evolved from a largely experimental technique to a sophisticated computational discipline, fundamentally transforming the drug discovery workflow [1]. By leveraging detailed insights into atomic-level interactions between a drug candidate and its target, SBDD facilitates a more rational and efficient path to identifying lead compounds, optimizing their potency and selectivity, and overcoming challenges such as drug resistance [2]. This article delineates the core principles of SBDD, provides a detailed protocol for a key experimental process, and synthesizes current computational advances that are propelling the field forward, including the integration of machine learning and high-throughput molecular simulations.

At its core, SBDD is an approach to drug discovery that relies on the knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of a biological target, typically a protein or nucleic acid, to design molecules that can interact with it in a specific and therapeutically beneficial manner [1]. This methodology stands in contrast to traditional empirical methods, offering a rational framework that reduces reliance on serendipity and high-volume screening alone.

The strategic value of SBDD is profoundly amplified by treating the underlying structural and chemical data as a high-value product in its own right. High-quality SBDD data products are characterized by rigorous validation, standardized formats, comprehensive metadata, and intuitive interfaces that democratize access across multidisciplinary teams, from structural biologists to medicinal chemists [1]. The process generally follows a cyclical workflow: Target Selection and Validation → Structure Determination → Ligand Docking and Design → Compound Synthesis → Experimental Assay → Lead Optimization, with insights from each stage feeding back into the next design cycle. The subsequent sections will unpack the specific methodologies and tools that make this cycle possible.

Core Methodologies and Data

SBDD integrates a suite of computational and experimental techniques. The table below summarizes the primary computational methods used for identifying and optimizing lead compounds.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods in Structure-Based Drug Design

| Method | Primary Function | Common Tools/Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | Constructs a 3D model of a target protein when an experimental structure is unavailable, using a related protein with a known structure as a template [2]. | MODELLER [2] |

| Molecular Docking | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein [2]. | AutoDock Vina, InstaDock [2] |

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) | Automatically evaluates large libraries of compounds (e.g., 89,399 in a recent study) through docking to identify potential hits for further experimental testing [2]. | AutoDock Vina [2] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Models the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into protein-ligand complex stability, conformational changes, and binding dynamics [1] [2]. | GROMACS [1] |

| Machine Learning (ML) Classification | Employs algorithms to distinguish between active and inactive compounds based on chemical descriptor properties, refining hit lists from virtual screening [2]. | PaDEL-Descriptor for feature generation [2] |

The integration of these methods was exemplified in a recent study aiming to identify natural inhibitors of the human αβIII tubulin isotype, a cancer-relevant target. The workflow, summarized in the diagram below, involved homology modeling, virtual screening of a 89,399-compound library, machine learning to narrow 1,000 hits to 20 active compounds, and finally, molecular dynamics simulations to validate the stability of the top four candidates [2].

Diagram 1: SBDD workflow for identifying tubulin inhibitors.

Experimental Protocol: Protein Production for SBDD

A critical bottleneck in SBDD is the production of sufficient quantities of high-quality, pure protein for structural studies. The following protocol details the manufacture and setup of a cost-effective, single-use bubble column reactor (suBCR) array for litre-scale expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli, designed to overcome the limitations of traditional shake-flasks [3].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for suBCR Setup

| Item | Specification/Example | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Layflat Tubing (LFT) | Heavy-duty (125-250 micron) Polyethylene (PE) or autoclaveable Polypropylene (PP) [3]. | Forms the single-use bioreactor bag. |

| Air Pump | Aquarium diaphragm air pump (e.g., Tetra brand) [3]. | Supplies oxygen to the bacterial culture. |

| Airline | Semi-rigid food/lab grade tubing, 4-4.5mm internal diameter (e.g., Legris PUR pipe) [3]. | Transports air from the pump to the bioreactor. |

| Airstones | Cylindrical, 25-30mm (e.g., Tetra air stones) [3]. | Diffuses air into fine bubbles for efficient oxygen transfer. |

| Foam Stopper | Indenti-Plug L800-E, for 46-65mm openings [3]. | Seals the bag while holding the airline; allows gas exchange. |

| Temperature Control | Submersible aquarium heater (200-300W) and/or recirculating lab water chiller [3]. | Maintains optimal culture temperature. |

| Injection Ports | Self-healing, adhesive ports (e.g., 3M) [3]. | Allows for sterile inoculation and sampling. |

| Impulse Sealer | Standard commercial heat sealer. | Creates airtight seals at the ends of the LFT bags. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparing the Airline Assembly:

- Cut a 1.5-1.6m length of airline tubing.

- Insert an airstone into one end.

- Thread the opposite end through a foam stopper, sliding the stopper to approximately 70cm above the airstone. The foam should grip the tubing to hold it in place [3].

Manufacturing the Single-Use Bioreactor (Bag):

- Measure and cut a ~2.8m length of layflat tubing for a 1.2m tall rail system.

- Use an impulse sealer to create a heat seal at one end of the tubing, allowing a 20-30mm seam allowance.

- On the outer face of the bag, below the point where it will hang freely, make a ~100mm vertical slit. This provides access for the airline and for filling the bag [3].

- Affix a self-healing injection port above the intended liquid fill line.

System Setup and Operation:

- Suspend the manufactured bags from a rail system over a water bath.

- Fill the water bath and activate the temperature control system (heater and recirculating pump).

- Connect the airline from the pump to the top of the airline assembly using a flow control valve.

- Fill the bags with sterile culture media through the slit or injection port.

- Insert the airline assembly into the bag through the slit, ensuring the airstone is at the bottom. The foam stopper should form a seal inside the neck of the bag.

- Inoculate the culture through the self-healing injection port.

- Turn on the air supply and adjust the flow rate to achieve adequate aeration and mixing via bubble formation [3].

Current Advances and Future Outlook

The field of SBDD is being rapidly transformed by new computational technologies. A prominent trend is the deep integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning. The quality and organization of training data are now recognized as paramount, with organizations that maintain pristine structural data products gaining a competitive edge in developing next-generation AI tools for predicting protein-ligand interactions [1] [2].

Furthermore, federated data ecosystems are emerging, allowing organizations to collaboratively share structural information while preserving proprietary interests, thus accelerating discovery across the entire industry [1]. Conferences like the SBDD 2025 Congress highlight cutting-edge research in AI-driven approaches, molecular modeling, and advanced simulations, underscoring the dynamic evolution of the field [4]. The industry is also moving towards more integrated enterprise software solutions, such as the Proasis platform, which are designed to translate 3D structural data into a powerful, actionable strategic asset for drug discovery teams [1].

Structure-Based Drug Design has firmly established itself as a rational and indispensable approach in modern drug discovery. By moving beyond pure empiricism to a detailed, structure-guided process, SBDD significantly increases the efficiency and success rate of developing new therapeutics. The continued advancement of the field—through improvements in high-throughput protein production, more sophisticated and integrated computational workflows, and the powerful application of AI—promises to further accelerate the delivery of novel treatments for diseases ranging from cancer to antibiotic resistance. As these tools become more accessible and data ecosystems more collaborative, SBDD will continue to be a cornerstone of innovative drug development.

The Critical Role of 3D Protein Structures

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) is a foundational paradigm in modern drug discovery, focused on the development and interpretation of three-dimensional (3D) models of protein-ligand interactions [5]. This rational approach uses the 3D structure of a biological target, typically a protein, to design and optimize novel drug candidates, thereby streamlining the discovery process [6]. The central premise of SBDD is that knowledge of the target's atomic structure enables researchers to rationally design molecules that bind with high affinity and selectivity, which has become an integral part of most industrial drug discovery programs [5]. The value of SBDD is significantly enhanced by treating the underlying structural and experimental data not as a mere byproduct of research, but as a high-value product in its own right, characterized by rigorous validation, standardized formats, and comprehensive metadata [1].

The Centrality of Accurate 3D Protein Structures

The accuracy of the initial 3D structural model is a critical determinant of success in any SBDD campaign. Inaccurate structures can misdirect design efforts, leading to costly delays and failures. The field relies on both experimental and computational techniques to obtain these essential models, each with distinct advantages and limitations [5].

Experimental Structure Determination Methods

- X-ray Crystallography: This traditional workhorse of structural biology involves crystallizing the target protein, often with a bound ligand, and determining its structure by analyzing the diffraction pattern of X-rays passed through the crystal. While powerful, it can be challenging for certain protein classes (e.g., membrane proteins), is time-consuming, and requires high-resolution data for accurate SBDD, as minute differences in side-chain conformation can be crucial for analyzing binding interactions [5].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): This emerging alternative to crystallography addresses many of its challenges, particularly for large protein complexes that are difficult to crystallize. Although access to cryo-EM facilities can be limited, its use is expected to grow significantly in the coming decades [5].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): NMR spectroscopy can be used to determine protein structures in solution, providing insights into dynamic behavior. However, it is generally limited to smaller proteins [5].

Computational Structure Prediction Methods

Computational methods have emerged as powerful alternatives or complements to experimental techniques.

- Machine Learning-Based Prediction: Advances in machine learning, exemplified by models like AlphaFold2, have revolutionized the field by enabling accurate protein structure prediction from amino acid sequence data alone [5]. These models have dramatically expanded the structural coverage of the proteome.

- Docking and Co-folding Algorithms: Docking algorithms (e.g., AutoDock Vina) can predict how a small molecule binds to a protein target. A newer generation of models, including AlphaFold3 and HelixFold3, perform protein-ligand co-folding, simultaneously predicting the protein structure and its binding mode with a ligand [5]. While their accuracy may be lower than high-resolution crystallography, their speed promises to accelerate SBDD, especially for intractable targets.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Structure Determination and Modeling Techniques

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Resolution/Accuracy | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | X-ray diffraction from protein crystals | Atomic resolution (dependent on crystal quality) | High accuracy for well-diffracting crystals; direct experimental data | Difficult for membrane proteins; time-consuming crystallization |

| Cryo-EM | Electron microscopy of frozen-hydrated samples | Near-atomic to atomic resolution | Suitable for large complexes; no crystallization needed | Limited access to facilities; can be resource-intensive |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Deep learning on evolutionary data | High accuracy (varies by protein) [7] | Fast; based on sequence alone; covers many proteins | Can underestimate binding pocket volumes [7] |

| DeepSCFold | Deep learning on sequence-derived complementarity | 11.6% higher TM-score than AlphaFold-Multimer [8] | Excels in protein complex & antibody-antigen modeling [8] | Newer method; requires further community adoption |

A critical evaluation of computational models against experimental structures is essential. For instance, a 2025 comprehensive analysis of nuclear receptor structures revealed that while AlphaFold2 achieves high accuracy in predicting stable conformations with proper stereochemistry, it systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and captures only single conformational states, missing functionally important asymmetry observed in experimental structures [7]. This highlights the importance of understanding the limitations of predictive models in SBDD.

Application Notes: SBDD in Action

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) for Hit Identification

This protocol details the use of a target protein's 3D structure to computationally screen large libraries of small molecules for potential hits.

1. Target Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the PDB, or via prediction tools like AlphaFold or DeepSCFold for complexes [8].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and optimizing side-chain orientations for residues in the binding site using molecular modeling software.

- Define the binding site coordinates, typically centered on a known ligand or a key residue in the active site.

2. Ligand Library Preparation

- Select a compound library (e.g., ZINC natural compounds, in-house corporate library) [2].

- Prepare ligands by generating 3D structures, enumerating plausible tautomers and protonation states at biological pH, and minimizing their energy to achieve a low-energy conformation.

3. Molecular Docking

- Perform high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) using docking software such as AutoDock Vina or a platform like InstaDock [2].

- Key Parameters: The docking search space should be defined by a grid box centered on the binding site. The exhaustiveness of the global search should be set sufficiently high (e.g., 32-128) to ensure adequate sampling of ligand poses. Each compound is typically docked in multiple flexible conformations.

- The output is a ranked list of compounds based on the computed binding affinity (e.g., Vina score) [2].

4. Post-Docking Analysis

- Visually inspect the top-ranking poses to confirm they form sensible interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) with the protein target.

- Cluster results based on chemical structure and binding mode to prioritize diverse chemotypes for further experimental testing.

Diagram Title: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

Protocol 2: Hit-to-Lead Optimization Using Molecular Dynamics

After confirming hits, this protocol uses molecular dynamics (MD) to understand and optimize the binding interaction, moving from a static view to a dynamic one.

1. System Setup

- Build the simulation system by placing the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box (e.g., a cubic or rhombic dodecahedron box) filled with water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model).

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and mimic a physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

2. Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove any steric clashes introduced during system setup.

- Equilibration: Perform a two-step equilibration in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles to stabilize the temperature and pressure of the system. This is typically done for 100-500 ps.

3. Production MD Simulation

- Run an unbiased MD simulation for a timescale relevant to the biological process (typically 100 ns to 1 µs). Use a integration time step of 2 fs.

- Key Analyses:

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD): Measure the stability of the protein and ligand backbone over time.

- Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF): Identify flexible regions of the protein, particularly in the binding site.

- Ligand-protein interactions: Calculate the occupancy of specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges) throughout the simulation to identify key binding motifs.

- Binding pocket analysis: Use tools like WaterMap to analyze solvation effects and identify displaceable water molecules for potential affinity gains [9].

4. Insight-Driven Design

- Use the dynamic interaction fingerprints from the MD simulation to guide rational compound design. For example, adding an electron-withdrawing group to a phenol can improve its hydrogen-bond donor capacity, while strategic conformational restriction (e.g., macrocyclization) can minimize the energetic penalty paid upon binding [5].

Table 2: Key Analyses in Molecular Dynamics Simulations for SBDD

| Analysis Metric | Description | Application in SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Root-Mean-Square Deviation) | Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures over time. | Assesses the overall stability of the protein-ligand complex during simulation. |

| RMSF (Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation) | Measures the deviation of a particle/atom from its average position. | Identifies flexible regions in the protein, especially in binding sites and loops. |

| H-Bond Occupancy | The percentage of simulation time a specific hydrogen bond exists. | Quantifies the strength and persistence of critical polar interactions. |

| Rg (Radius of Gyration) | Measures the compactness of the protein structure. | Monitors large-scale conformational changes or folding/unfolding events. |

| SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area) | Measures the surface area of a molecule accessible to a solvent. | Evaluates changes in protein folding and ligand burial upon binding. |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

Generative AI for 3D Molecular Design

A frontier in SBDD is the use of generative artificial intelligence to create novel drug molecules directly within the context of a 3D protein binding pocket. These models aim to generate molecules with high binding affinity, but the field is evolving to incorporate other critical drug-like properties, such as synthetic feasibility and selectivity, which are essential for practical drug discovery [10]. New frameworks like CByG (Controllable Bayesian Flow Network with Integrated Guidance) extend beyond conventional diffusion models to more robustly integrate property-specific guidance during the generation process, addressing limitations in handling the hybrid nature of 3D molecular data (continuous coordinates and categorical atom types) [10]. This highlights a shift from mere generation to controllable generation of viable drug candidates.

The Critical Role of Selectivity and Specificity

Beyond simple binding affinity, a successful drug must be selective for its intended target to minimize off-target side effects. This necessitates evaluating generated or designed molecules against off-target proteins. However, widely used public datasets like CrossDocked2020 were not originally designed for rigorous selectivity assessment, creating a need for new, biologically relevant benchmarks and guidance strategies specifically for selectivity [10]. SBDD protocols must therefore evolve to include multi-target docking and simulation studies to proactively address potential selectivity issues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SBDD

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | Primary archive for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Data Repository | Provides access to millions of predicted protein structures generated by the AlphaFold AI system. |

| AutoDock Vina | Software | Widely used open-source molecular docking tool for predicting small molecule binding modes and affinities. |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | A curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds for virtual screening. |

| DesertSci Proasis / Rowan Platform | Enterprise Software | Integrated platforms that manage 3D structural data, streamline SBDD workflows, and facilitate collaboration. [5] [1] |

| GROMACS | Software | A package for performing molecular dynamics simulations, used to study protein-ligand interactions over time. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Software Suite | A comprehensive commercial software platform for drug discovery, including tools for molecular modeling, simulation, and design. |

Diagram Title: The SBDD Ecosystem Data Flow

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) has become a cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical research, offering a rational framework for transforming initial hits into optimized drug candidates [11]. By leveraging detailed three-dimensional structural information, SBDD enables the design of compounds with enhanced potency, selectivity, and improved pharmacological profiles [12]. The success of SBDD relies heavily on high-resolution structural data of biological targets, primarily obtained through three principal experimental techniques: X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [12] [13]. This article provides a detailed comparison of these techniques, their specific applications in drug discovery, and standardized protocols for their implementation in SBDD workflows.

Technique Comparison and Applications

The selection of an appropriate structure determination technique depends on the target biomolecule's properties, the required resolution, and the specific stage of the drug discovery process. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Structural Biology Techniques in Drug Discovery

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Routinely < 2.5 Å, often sub-1 Å possible [14] | Typically 2.5-4.0 Å, with <2 Å possible [13] [14] | Atomic-level for proteins < 30 kDa [15] |

| Optimal Target Size | Best for proteins < 100 kDa [14] | Ideal for complexes > 100 kDa [14] | Suitable for proteins up to ~50 kDa [11] [16] |

| Sample State | Crystalline solid state | Vitrified solution (near-native) [14] | Solution state (physiological conditions) [11] |

| Key Advantage | Atomic precision; well-established pipelines [14] | No crystallization needed; captures conformational states [16] [14] | Studies dynamics & weak interactions; no crystallization [11] [15] |

| Primary Limitation | Requires high-quality crystals; static snapshot [11] [5] | High equipment cost; intensive computation [16] [14] | Low sensitivity; molecular weight constraints [11] |

| Throughput | Medium to High (after crystal optimization) [11] | Medium (data collection: hours to days) [14] | Low to Medium (data acquisition can be time-consuming) |

| Ideal for SBDD | High-throughput ligand screening, fragment growing [11] [14] | Membrane proteins, large complexes, flexible systems [13] [14] | Fragment-based discovery, studying protein dynamics & weak binding [11] [15] |

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide for SBDD

| SBDD Application | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Fragment Screening | X-ray Crystallography (if crystals available) [14] | Established soaking pipelines provide rapid structural data for many compounds. |

| Membrane Protein Target (e.g., GPCR) | Cryo-EM [13] [14] | Eliminates crystallization hurdle and preserves near-native lipid environment. |

| Target with Inherent Flexibility/Disorder | NMR or Cryo-EM [11] [16] | NMR probes dynamics in solution; Cryo-EM can capture multiple conformations. |

| Optimizing Weak Fragment Binders | NMR [11] [15] | Detects and characterizes weak, transient interactions critical for early FBDD. |

| Structure of a Large Viral Complex | Cryo-EM [16] [14] | No size limitations; can resolve large assemblies without crystal packing constraints. |

| Characterizing H-bonding & Protonation States | NMR [11] | Directly probes hydrogen atoms and their interactions, invisible to X-rays. |

Experimental Protocols

Protein Crystallography for Ligand Binding Studies

Objective: To determine the high-resolution structure of a target protein in complex with a small-molecule ligand to guide rational drug design [5].

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Details:

Protein Production and Crystallization:

- Express and purify the target protein to high homogeneity (>95% purity) [14]. Typical yields of >2 mg are required [14].

- Use high-throughput vapor diffusion screens to identify initial crystallization conditions.

- Optimize conditions to grow large, single, and well-ordered crystals. This process can take weeks to months [5] [14].

Ligand Soaking and Harvesting:

- For pre-formed crystals, soak the crystal in a cryoprotectant solution containing the ligand of interest. Ligand concentration should be high enough to ensure saturation, but mindful of DMSO tolerance [11].

- Alternatively, co-crystallize the protein with the ligand.

- Flash-cool the crystal in liquid nitrogen for data collection [14].

Data Collection and Processing:

- Collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron source. Data collection typically takes minutes to hours [14].

- Index, integrate, and scale the diffraction data using established software (e.g., XDS, HKL-3000) [14].

- Solve the phase problem, often by molecular replacement using a known related structure as a search model.

Model Building and Refinement:

- Fit the protein sequence into the electron density map and build the atomic model.

- Identify positive difference density (F~o~ - F~c~) in the binding pocket to place and refine the ligand geometry.

- Iteratively refine the model (coordinates and B-factors) against the diffraction data to achieve the best agreement (low R~work~/R~free~).

Key Reagents: Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Protein Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Pure Protein | The target for crystallization. | Requires high homogeneity; typical concentration 5-20 mg/mL. |

| Crystallization Screen Kits | To identify initial crystallization conditions. | Commercial sparse matrix screens (e.g., from Hampton Research). |

| Ligand Compound | The small molecule for binding studies. | Dissolved in DMSO; final DMSO concentration in soak should be <5%. |

| Cryoprotectant | Prevents ice crystal formation during vitrification. | e.g., Glycerol, ethylene glycol, or various cryoprotectant cocktails. |

Single-Particle Cryo-EM for Complex Structures

Objective: To determine the structure of a large protein or complex, particularly targets resistant to crystallization, in complex with a drug candidate [13].

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Details:

Sample Preparation and Vitrification:

- Prepare a purified sample of the protein-ligand complex. Sample amount required is minimal (0.1-0.2 mg) compared to crystallography [14].

- Incubate the protein with the ligand to form the complex prior to grid preparation.

- Apply 3-4 µL of sample to a freshly plasma-cleaned EM grid. Blot away excess liquid and rapidly plunge-freeze the grid in liquid ethane. Optimize blotting time and humidity to achieve a thin layer of vitreous ice [14].

Data Collection:

- Load the grid into a high-end cryo-electron microscope equipped with a direct electron detector.

- Collect thousands of micrograph movies at a calibrated defocus under low-electron-dose conditions to minimize beam-induced damage. Data collection can take hours to days [14].

Image Processing and 3D Reconstruction:

- Perform motion correction and estimate the contrast transfer function (CTF) for each micrograph [14].

- Autopick or manually pick particles from the micrographs.

- Perform multiple rounds of 2D classification to select a homogeneous set of particles.

- Generate an initial 3D model ab initio or by using a low-resolution structure as a reference, followed by high-resolution 3D refinement. This step is computationally intensive and requires high-performance computing [14].

Model Building and Validation:

- Fit an existing atomic model or de novo build a model into the reconstructed EM density map using software like Coot or Phenix.

- Refine the model against the map and validate using metrics such as Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC).

Key Reagents: Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Single-Particle Cryo-EM

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Macromolecular Complex | The target for structure determination. | Tolerates some heterogeneity; ideal for complexes >100 kDa. |

| EM Grids | Support for the vitrified sample. | e.g., Quantifoil or C-flat grids with holy carbon film. |

| Ligand Compound | The drug candidate for complex formation. | Pre-incubate with protein to ensure binding. |

| Plasma Cleaner | Makes the grid hydrophilic for even ice distribution. | Critical for achieving thin, homogenous vitreous ice. |

NMR Spectroscopy for Fragment-Based Drug Design

Objective: To identify and characterize the binding of small molecule fragments to a target protein and determine the structure of the complex in solution [11] [15].

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Details:

Sample Preparation:

- Produce uniformly ^15^N- and/or ^13^C-labeled protein by expressing it in bacterial culture media containing these isotopes as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources [11]. For larger proteins, selective labeling strategies can be employed [11].

- The protein must be soluble and stable at concentrations of 20-200 µM for protein-observed experiments [15].

Ligand Binding Experiments:

- Ligand-Observed NMR: Techniques like Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) NMR or WaterLOGSY are used to screen libraries of fragments (at ~100 µM concentration) against unlabeled protein (at ~5-50 µM) to identify binders [15].

- Protein-Observed NMR: For validated hits, record 2D ^1^H-^15^N Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) spectra of the labeled protein in the absence and presence of the ligand. Chemical Shift Perturbations (CSPs) of backbone amide resonances indicate binding and map the interaction site [11] [15].

Structure Calculation:

- Assign the protein's NMR resonances (backbone and side-chain) using triple-resonance experiments.

- Collect structural restraints: distance restraints from Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) spectroscopy, dihedral angle restraints from chemical shifts, and orientational restraints from Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs).

- Use computational tools and simulated annealing to calculate an ensemble of structures that satisfy all experimental restraints.

Key Reagents: Table 5: Key Research Reagents for NMR in SBDD

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Protein | Enables detection of protein signals in NMR. | ¹⁵N-labeled for HSQC; ¹³C/¹⁵N-labeled for full structure. |

| NMR Screening Library | A collection of low MW fragments for FBDD. | Typically 500-1000 compounds; solubility is critical. |

| Deuterated Solvent | Reduces background signal from solvent protons. | D₂O or deuterated buffers (e.g., in d³-DMSO for ligands). |

| NMR Tubes | Holds the sample within the NMR magnet. | High-quality Shigemi tubes are used for precious samples. |

X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, and NMR spectroscopy provide a powerful, complementary toolkit for structure-based drug design. The choice of technique is strategic, depending on the target's properties, the desired information, and the project stage. An integrative approach, combining data from multiple techniques, is increasingly becoming the gold standard for tackling challenging drug targets and accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics.

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) relies on detailed three-dimensional structural information of biological targets to guide the discovery and optimization of therapeutic compounds [17]. The central challenge has historically been obtaining accurate protein structures, which through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography can take years and considerable resources for a single structure [18]. The emergence of advanced computational predictors, most notably AlphaFold, has fundamentally transformed this landscape by providing rapid, accurate protein structure predictions at an unprecedented scale.

AlphaFold, developed by Google DeepMind, represents a revolutionary artificial intelligence (AI) system that can predict protein structures with atomic accuracy from amino acid sequences alone [19]. Its performance in the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental structures in most cases, marking a solution to the 50-year-old protein folding problem [20] [19]. This breakthrough has created new paradigms for SBDD, enabling researchers to access structural information for targets previously considered intractable due to lack of experimental data.

The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, developed in partnership with EMBL-EBI, now provides open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions, dramatically expanding the structural coverage of the proteome [21]. This vast resource offers particular promise for expanding the pool of druggable targets beyond the approximately 3,500 targets currently pursued in drug discovery to potentially include more of the estimated 50,000 unique proteins in the human proteome [17].

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

AlphaFold Architecture and Methodological Innovations

The exceptional performance of AlphaFold stems from its novel neural network architecture that integrates evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints of protein structures [19]. Unlike conventional approaches, AlphaFold employs an end-to-end deep learning model that directly predicts the 3D coordinates of all heavy atoms for a given protein using primary amino acid sequence and aligned sequences of homologs as inputs.

The network architecture consists of two primary components: the Evoformer module and the structure module. The Evoformer, a novel neural network block, processes inputs through repeated layers that operate on both a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) representation and a pair representation [19]. This design enables continuous information exchange between evolving MSA representations and residue-pair relationships, allowing the network to reason about spatial and evolutionary constraints simultaneously. The structure module then generates an explicit 3D structure through a series of rotations and translations for each residue, with key innovations including breaking chain structure to allow simultaneous local refinement and using an equivariant transformer to implicitly reason about side-chain atoms [19].

A critical feature of AlphaFold is its iterative refinement process, where the network repeatedly applies the final loss to outputs and feeds them recursively into the same modules. This recycling process significantly enhances accuracy with minimal extra computational cost during training [19]. The system also provides per-residue confidence estimates through predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) scores, enabling researchers to assess the reliability of different regions within a predicted structure [17] [19].

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

AlphaFold's remarkable accuracy has been rigorously validated through independent assessments. In CASP14, AlphaFold demonstrated median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (Cα root-mean-square deviation at 95% residue coverage), dramatically outperforming other methods which achieved median backbone accuracy of 2.8 Å [19]. For context, the width of a carbon atom is approximately 1.4 Å, highlighting the atomic-level precision achieved.

Table 1: AlphaFold Accuracy Metrics from CASP14 Assessment

| Metric | AlphaFold Performance | Next Best Method Performance | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone Accuracy | 0.96 Å RMSD95 | 2.8 Å RMSD95 | Cα atoms at 95% residue coverage |

| All-Atom Accuracy | 1.5 Å RMSD95 | 3.5 Å RMSD95 | All heavy atoms at 95% residue coverage |

| Side-Chain Accuracy | High accuracy when backbone is correct | Substantially less accurate | Precise side-chain positioning |

For drug discovery applications, side-chain positioning is particularly critical for defining binding pockets and modeling ligand interactions [17]. While AlphaFold achieves high overall accuracy, assessment of its all-atom accuracy (including side chains) reveals that for proteins without good templates in the Protein Data Bank, it achieves within 2 Å and 1 Å in 52% and 17% of cases, respectively [17]. This level of precision enables many SBDD applications, though particularly challenging targets may require additional refinement.

Table 2: AlphaFold Performance in Structure-Based Drug Design Context

| Application Parameter | Performance Metric | Implications for SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone Accuracy (template-free) | Median RMSD95 of 1.46 Å | Suitable for binding site identification |

| First Quartile Backbone Accuracy | RMSD95 of 0.79 Å | High accuracy for many targets |

| All-Atom Accuracy (<2Å) | 52% of template-free cases | Enables many virtual screening applications |

| All-Atom Accuracy (<1Å) | 17% of template-free cases | Suitable for precise binding pocket definition |

| Confidence Estimation | Strong correlation with actual accuracy | Guides appropriate use in SBDD pipelines |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Utilizing AlphaFold Predictions for Druggability Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate the potential of a novel protein target for small-molecule drug development using AlphaFold-predicted structures.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target protein sequence in FASTA format

- AlphaFold Protein Structure Database access or AlphaFold Server for custom predictions

- Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, ChimeraX)

- Binding site detection tools (e.g., FPOCKET, DeepSite)

- Structural alignment software (if known binding sites from homologs are available)

Procedure:

- Structure Acquisition: Query the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database using the target protein's UniProt identifier. If no prediction exists, submit the amino acid sequence to the AlphaFold Server for prediction [21].

- Quality Assessment: Examine the per-residue pLDDT scores throughout the structure. Regions with scores >90 are considered high confidence, 70-90 as confident, 50-70 as low confidence, and <50 as very low confidence [19].

- Binding Pocket Identification: Use computational tools to detect and characterize potential binding pockets, prioritizing cavities in high-confidence regions with appropriate physicochemical properties for ligand binding [17].

- Conservation Analysis: If multiple sequence alignments are available, assess evolutionary conservation of residues lining the potential binding pocket.

- Structural Comparison: If structures of homologous proteins with known ligands exist, perform structural alignment to assess similarity in binding site architecture.

- Druggability Scoring: Apply quantitative druggability assessment algorithms (e.g., DrugScore, PocketDepth) to estimate the likelihood of successful small-molecule targeting.

Interpretation: Targets with well-defined, conserved binding pockets in high-confidence regions of the AlphaFold model represent promising candidates for further SBDD efforts. Targets with poorly defined or shallow binding surfaces may require experimental structure determination or be less suitable for small-molecule approaches.

Protocol: Integration of AlphaFold Structures with Molecular Dynamics for Binding Site Refinement

Purpose: To improve the accuracy of AlphaFold-predicted binding sites for ligand docking through molecular dynamics simulations.

Materials and Reagents:

- AlphaFold-predicted structure in PDB format

- Molecular dynamics software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER)

- Force field parameters (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB)

- High-performance computing resources

- Solvation box (e.g., TIP3P water model)

- Ion parameters for physiological concentration

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Import the AlphaFold-predicted structure into the molecular dynamics environment. Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states for ionizable residues based on physiological pH.

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the protein in an appropriate water box, ensuring sufficient margin (typically ≥10 Å) from protein atoms to box edges. Add ions to achieve physiological concentration and neutralize system charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes and optimize the initial structure.

- Equilibration: Conduct gradual heating from 0K to 310K over 100ps with position restraints on protein heavy atoms, followed by equilibrium runs without restraints to stabilize system density and temperature.

- Production Simulation: Run unrestrained molecular dynamics for a time scale sufficient to capture binding site flexibility (typically 100ns-1μs depending on system size and complexity).

- Cluster Analysis: Identify representative conformations of the binding site through cluster analysis of trajectory frames based on binding site residue root-mean-square deviation.

- Ensemble Selection: Select dominant cluster centroids as representative structures for docking studies.

Interpretation: Molecular dynamics simulations can address limitations in static AlphaFold models by sampling flexible regions and providing conformational ensembles that more accurately represent the dynamic nature of binding sites [22]. This is particularly valuable for regions with moderate pLDDT scores (70-90) where some flexibility is expected.

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational SBDD

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for AlphaFold-Enabled SBDD

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides pre-computed structures for over 200 million proteins | Public access via web interface [21] |

| AlphaFold Server | Prediction tool | Generates protein structure predictions from amino acid sequences | Web interface with submission queue [18] |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics software | Performs high-performance molecular dynamics simulations for structure refinement | Open-source download [22] |

| PyMOL/ChimeraX | Visualization software | Enables 3D visualization and analysis of predicted structures | Open-source or commercial licenses |

| FPOCKET | Binding site detection | Identifies and characterizes potential small-molecule binding pockets | Open-source download |

| OpenFold | Training framework | Enables retraining of AlphaFold-like models on custom datasets | Open-source implementation [23] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Beyond Monomeric Proteins: Complex Prediction and State-Specific Modeling

While initial AlphaFold implementations focused on single-chain proteins, recent advancements have expanded capabilities to model protein-protein complexes and conformational states highly relevant to drug discovery. RoseTTAFold, developed by David Baker's laboratory, incorporates approaches similar to AlphaFold while supporting protein-protein complexes [17]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding signaling complexes and allosteric regulatory mechanisms.

For G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) - a prominent class of drug targets - specialized implementations like AlphaFold-MultiState have been developed to generate state-specific models [23]. By using activation state-annotated template databases, this approach can produce models representative of active, inactive, or intermediate states critical for understanding ligand efficacy and designing selective compounds [23].

The accurate prediction of GPCR-ligand complex geometries remains challenging. Benchmark studies demonstrate that despite improved binding pocket accuracy with AlphaFold, successful prediction of ligand binding poses (defined as ≤2.0 Å RMSD from experimental structures) does not automatically follow [23]. Integration with molecular dynamics and advanced docking protocols that account for pocket flexibility remains essential for reliable complex prediction.

Protocol: Generation of State-Specific GPCR Models for SBDD

Purpose: To create conformational state-specific models of GPCR targets for structure-based discovery of selective modulators.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target GPCR sequence in FASTA format

- State-annotated GPCR structure database (e.g., GPCRdb)

- AlphaFold-MultiState implementation or template-guided sampling

- Molecular dynamics simulation package

Procedure:

- Template Curation: Collect experimental GPCR structures annotated by activation state (active, inactive, intermediate) and transducer coupling (G-protein, arrestin).

- Sequence Alignment: Generate accurate sequence alignment between target GPCR and state-annotated templates.

- State-Specific Prediction: Utilize AlphaFold-MultiState or modify AlphaFold input to bias toward specific conformational states through template selection and weighting.

- Model Validation: Assess conserved activation motifs (e.g., TXP, DRY, NPxxY) for conformation consistent with target state.

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: Run limited molecular dynamics simulations (50-100ns) to assess model stability and state-specific features.

- Ensemble Generation: If targeting multiple states, repeat process for each relevant conformational state.

Interpretation: State-specific models enable structure-based design of biased agonists or selective antagonists by revealing structural features unique to particular functional states. This approach is particularly valuable for GPCRs with no experimental structures in desired conformational states.

The rise of computational predictors, particularly AlphaFold, represents a paradigm shift in structure-based drug design. By providing rapid access to accurate protein structures at proteome scale, these tools have dramatically expanded the universe of druggable targets and accelerated early drug discovery workflows. The integration of AI-predicted structures with traditional experimental methods and computational techniques like molecular dynamics creates a powerful framework for rational drug design.

While limitations remain - particularly regarding modeling of protein complexes, flexible regions, and specific conformational states - ongoing advancements in algorithms and specialized implementations continue to address these challenges. The research community's ability to leverage these tools through standardized protocols and critical assessment of model quality will determine the full impact on therapeutic development.

As computational predictors evolve beyond single-state, single-chain predictions to model complex biological assemblies and dynamics, their utility in drug discovery will further expand. This progress, combined with growing databases and user-friendly interfaces, promises to make computational structure prediction an increasingly central component of the drug discovery pipeline, potentially reducing development timelines and costs while increasing success rates for novel therapeutic modalities.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the single global archive for three-dimensional structural data of large biological molecules, including proteins and nucleic acids [24]. Overseen by the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB), this database is a foundational resource for structural biology and structure-based drug design (SBDD) [24]. By providing free access to experimentally determined structures of biological macromolecules and their complexes with small molecule ligands (e.g., inhibitors and drugs), the PDB enables researchers to understand molecular interactions at the atomic level [25]. For drug development professionals, this structural information is crucial for rational drug design, allowing for the identification of binding sites, analysis of molecular mechanisms, and structure-based optimization of lead compounds.

The PDB archive has experienced exponential growth since its establishment in 1971, surpassing 200,000 structures by January 2023 [24]. This vast repository includes structures determined through various experimental methods, with the majority solved by X-ray crystallography, followed by electron microscopy (3DEM) and NMR spectroscopy [24]. Each entry contains detailed experimental procedures and constraints used in solving the structure, providing essential context for evaluating the reliability and applicability of the structural data for SBDD projects [25]. The ongoing curation and validation by wwPDB experts ensure the data quality and consistency necessary for rigorous scientific research [24].

Distribution of Structures by Experimental Method

The PDB archive contains a diverse collection of structures determined through various experimental methodologies. The following table summarizes the current distribution of released structures by experimental method and molecular type as of November 2025 [24].

Table 1: PDB Holdings by Experimental Method and Molecular Type (as of November 2025)

| Experimental Method | Proteins Only | Proteins with Oligosaccharides | Protein/Nucleic Acid Complexes | Nucleic Acids Only | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray diffraction | 176,378 | 10,284 | 9,007 | 3,077 | 185 | 198,931 |

| Electron microscopy | 20,438 | 3,396 | 5,931 | 200 | 13 | 29,978 |

| NMR | 12,709 | 34 | 287 | 1,554 | 39 | 14,623 |

| Integrative | 342 | 8 | 24 | 2 | 3 | 379 |

| Multiple methods | 221 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 1 | 255 |

| Neutron | 83 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 87 |

| Other | 32 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 37 |

| Total | 210,203 | 13,734 | 15,256 | 4,852 | 245 | 244,290 |

Additional Data Holdings

Beyond the primary coordinate data, the PDB provides access to supplementary experimental data files that are essential for structural validation and advanced analysis in SBDD workflows [24].

Table 2: Supplementary Data Files in the PDB Archive

| Data File Type | Number of Structures | Primary Use in SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| Structure factor files | 162,041 | Electron density map visualization and model validation for X-ray structures |

| NMR restraint files | 11,242 | Analysis of structural constraints and dynamics for NMR-determined structures |

| Chemical shifts files | 5,774 | Assessment of protein folding and binding interactions in solution |

| 3DEM map files | 13,388 | Validation and interpretation of cryo-EM structures, particularly large complexes |

Accessing and Retrieving PDB Data for SBDD

Data Retrieval Protocols

Protocol 1: Accessing Structure Data via RCSB PDB Web Portal

- Navigation: Access the RCSB PDB homepage at https://www.rcsb.org/ [26].

- Search: Utilize the search functionality with specific queries (protein name, PDB ID, gene symbol, or ligand identifier).

- Filter: Apply filters for experimental method, resolution (for X-ray structures), organism, or release date to refine results.

- Selection: Identify and select the relevant structure from the search results.

- Download: Choose the appropriate file format (PDB, mmCIF, or PDBML) based on your computational requirements and analysis tools [24].

- Visualization: Use integrated web-based viewers or external molecular graphics software for initial structure assessment.

Protocol 2: Programmatic Access via PDB Web Services

- API Endpoints: Utilize RESTful Web Services provided by RCSB PDB for programmatic access.

- Query Construction: Formulate specific queries using the search schema to retrieve targeted structural data.

- Data Retrieval: Execute queries and parse returned data in JSON or XML format.

- Batch Download: Implement scripting (Python, Perl) for automated download of multiple structures using their PDB IDs.

- Integration: Incorporate retrieved data directly into custom SBDD pipelines and analysis workflows.

Data Formats and Visualization Tools

The PDB provides structural data in multiple formats to accommodate various research applications [24]. The legacy PDB format, restricted to 80 characters per line, is being progressively replaced by the more robust mmCIF format, which became the standard for the PDB archive in 2014 [24]. For applications requiring structured data exchange, PDBML (an XML version) provides comprehensive metadata alongside coordinate data [24].

For visualization in SBDD, numerous molecular graphics programs are available. Open-source options include PyMOL, ChimeraX, Jmol, and UCSF Chimera, while commercial packages such as Schrödinger's Maestro and CCG's Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) offer integrated drug design capabilities. The RCSB PDB website maintains an extensive list of visualization tools with direct links for convenient access [24].

Experimental Methodologies in PDB Structures

Understanding the experimental methodologies behind PDB structures is essential for proper interpretation in SBDD contexts. Each method has specific strengths, limitations, and quality metrics that influence how the structural data should be utilized in drug design projects [25].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for Structure Determination in the PDB

| Method | Key Technical Parameters | Strengths for SBDD | Limitations for SBDD | Quality Assessment Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Resolution (Å), R-factor, R-free, Space group, Unit cell dimensions | High resolution; Clear electron density for small molecules; Direct observation of binding interactions | Requires crystallization; Crystal packing artifacts; Static snapshot of conformation | Resolution ≤2.0Å preferred; R-free value; Electron density fit; Ramachandran outliers |

| Electron Microscopy (3DEM) | Resolution (Å), Map resolution, Model-map correlation (Q-score) | Suitable for large complexes; Native-like environments; Multiple conformational states | Typically lower resolution than X-ray; Limited small molecule density | Overall resolution; Local resolution variation; Model-map fit; Q-score percentiles |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Number of restraints, RMSD bundle, Energy minimization state | Solution state dynamics; Conformational flexibility; Binding kinetics | Size limitations (~50 kDa); Model ensemble rather than single structure | Restraint violations; RMSD of bundle; Ramachandran statistics; PROCHECK NMR |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3: Evaluating X-ray Crystallography Structures for SBDD

- Assess Experimental Details: Navigate to the "Experiment" tab on the RCSB PDB structure summary page to review crystallization conditions, data collection statistics, and refinement parameters [25].

- Evaluate Resolution: Check the resolution value (preferably ≤2.0Å for reliable ligand positioning).

- Analyze Electron Density: Access the structure factor file to visualize the electron density map around the binding site and ligand.

- Validate Geometry: Use validation reports to identify steric clashes, rotamer outliers, and Ramachandran outliers.

- Check for Bias: Review if molecular replacement was used (potential for model bias) and examine the R-free value for independent validation.

- Examine Ligand Density: Ensure the ligand has clear, contiguous electron density supporting its placement and conformation.

Protocol 4: Utilizing NMR Structures for SBDD

- Review Restraint Data: Access NMR restraint files to understand the experimental constraints used in structure calculation [25].

- Analyze Ensemble: Examine the conformational diversity presented in the ensemble of models.

- Identify Core Regions: Distinguish between well-defined regions (low RMSD) and flexible loops (high RMSD).

- Check Binding Interface: Determine if the binding site is well-defined across the ensemble or exhibits flexibility.

- Review NMR Experiments: Identify the types of NMR experiments performed (e.g., NOESY, HSQC) to assess data quality and completeness [25].

Protocol 5: Working with Cryo-EM Structures for SBDD

- Access EMDB Map: Retrieve the associated 3D EM map from the Electron Microscopy Data Bank using the provided EMDB ID [24].

- Evaluate Resolution: Check global and local resolution estimates, particularly in the binding region of interest.

- Validate Model-Map Fit: Use the Q-score percentile slider in the validation report to assess the model-map correlation [26].

- Analyze Density: Examine the map density for ligands, cofactors, and key binding residues.

- Check for Flexibility: Identify regions with weaker density that may indicate structural flexibility or mobility.

Application in Structure-Based Drug Design Workflows

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

Protocol 6: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Using PDB Structures

- Target Selection: Identify and retrieve a protein target structure from the PDB with a relevant bound ligand or in apo form.

- Binding Site Definition: Define the binding pocket using the coordinates of a native ligand or through binding site detection algorithms.

- Structure Preparation: Process the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks.

- Ligand Library Preparation: Curate a database of small molecule compounds for screening with appropriate tautomer and stereoisomer representation.

- Molecular Docking: Perform high-throughput docking of compound libraries into the defined binding site.

- Pose Scoring and Ranking: Evaluate and rank ligand poses based on complementary scoring functions.

- Hit Selection: Select top-ranking compounds for experimental validation based on docking scores, interaction patterns, and chemical diversity.

- Validation: Test selected compounds using biochemical or biophysical assays to confirm binding and functional activity.

Lead Optimization Workflow

Diagram 1: SBDD Lead Optimization Workflow

Binding Site Analysis and Comparison

Protocol 7: Comparative Binding Site Analysis Across Orthosteric Structures

- Structure Retrieval: Collect multiple PDB structures of the target protein with different bound ligands.

- Structure Alignment: Superimpose structures using conserved structural elements outside the binding site.

- Binding Site Comparison: Analyze conformational differences in binding site residues, side chain rotamers, and backbone movements.

- Pocket Volume Calculation: Compute and compare binding pocket volumes and shapes across different structures.

- Conserved Interaction Mapping: Identify conserved protein-ligand interactions critical for binding.

- Water Structure Analysis: Compare conserved water molecules in the binding site that may mediate ligand interactions.

- Allosteric Effects: Identify conformational changes that may indicate allosteric mechanisms or induced fit binding.

- Selectivity Assessment: Compare with structures of related proteins (e.g., kinase family members) to identify selectivity determinants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Structure-Based Drug Design

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in SBDD | Access Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure Databases | PDB archive, AlphaFold DB, ModelArchive | Source of experimental and predicted protein structures for target identification and characterization | RCSB PDB [26] |

| Specialized Analysis Tools | PDBePISA, PDBeFold, PDBeMotif | Analysis of protein interfaces, structure comparison, and motif identification | PDBe [27] |

| Validation Resources | wwPDB Validation Reports, MolProbity | Assessment of structure quality and identification of potential issues in experimental data | wwPDB [24] |

| NMR Data Resources | Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) | Access to NMR chemical shifts, coupling constants, and relaxation parameters for structural validation | BMRB [27] |

| Electron Microscopy Data | Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) | Repository for 3D EM maps and associated data for large complexes and cellular structures | EMDB [27] |

| Ligand Chemistry Resources | Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD), PDB ligand data | Chemical information about small molecules, ions, and modified residues found in PDB structures | RCSB PDB [26] |

| Structure Visualization | Mol*, 3D-proton, JSmol | Interactive visualization of structures, electron density, and validation data | RCSB PDB, PDBe, PDBj [24] |

| Sequence-Structure Analysis | SESAW, Conserved Domain Database | Identification of functionally conserved motifs and domain annotations | wwPDB [27] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Integrative/Hybrid Methods in Structural Biology

The PDB archive now includes structures determined using integrative/hybrid methods that combine data from multiple experimental techniques [26]. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying large, flexible macromolecular complexes that are challenging to characterize with single methods. For SBDD, integrative structures provide insights into molecular machines and signaling complexes that represent emerging drug targets.

Protocol 8: Utilizing Integrative Structures for Complex Target Characterization

- Identify Multi-domain Systems: Select targets that involve multiple domains or subunits with conformational flexibility.

- Retrieve Integrative Models: Access structures determined through hybrid methods (e.g., X-ray with SAXS, EM with NMR).

- Analyze Interface Regions: Focus on protein-protein or protein-nucleic acid interfaces that could be targeted with stabilizers or disruptors.

- Evaluate Confidence Metrics: Review uncertainty estimates and resolution indicators for different regions of the model.

- Map Allosteric Networks: Identify potential allosteric communication pathways that could be modulated by small molecules.

- Design Interface-targeted Compounds: Develop strategies to target protein-protein interactions rather than traditional active sites.

Computed Structure Models in SBDD

The RCSB PDB now provides access to Computed Structure Models (CSMs) from AlphaFold DB and ModelArchive alongside experimentally determined structures [26]. These high-accuracy predictions significantly expand structural coverage of the proteome, particularly for targets without experimental structures.

Diagram 2: Structure Selection Strategy for SBDD

Metalloprotein Remediation and Annotation

The wwPDB has announced a comprehensive remediation initiative for metalloprotein-containing PDB entries to improve the chemical description and metal coordination annotations [26]. This enhancement is particularly relevant for SBDD targeting metalloenzymes, which represent important drug targets in various therapeutic areas including oncology, infectious diseases, and neuroscience.

Protocol 9: Working with Metalloprotein Structures in SBDD

- Identify Metal Coordination: Review updated metalloprotein entries for complete metal coordination geometry.

- Validate Metal-Ligand Interactions: Check metal-ligand bond lengths and angles against expected values.

- Assess Catalytic Mechanisms: Analyze the role of metals in catalytic mechanisms for inhibitor design.

- Design Metal-Chelating Compounds: Develop inhibitors that directly coordinate with active site metals.

- Evaluate Selectivity: Compare metal coordination environments across related metalloenzymes to design selective inhibitors.

- Consider Metal Replacement: Explore strategies for isostructural metal replacement in inhibitor design.

SBDD in Action: Computational Methods and Workflow Applications

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) represents a pivotal methodology in modern pharmaceutical research, enabling the rational design and optimization of therapeutic compounds by leveraging three-dimensional structural information of biological targets [28]. Within this framework, molecular docking has emerged as an indispensable computational technique for predicting how small molecule ligands interact with their protein targets at an atomic level [29]. By simulating the binding conformation and orientation of a ligand within a receptor's binding site, docking methodologies provide critical insights into molecular recognition processes that underpin drug action [30]. The primary objectives of molecular docking encompass pose prediction (determining the correct binding geometry), virtual screening (identifying potential hits from large compound libraries), and binding affinity estimation [30]. As the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to reduce the time and costs associated with drug development—a process that typically spans 12-15 years and exceeds $1 billion USD—the integration of efficient and accurate docking protocols has become increasingly valuable for accelerating early-stage discovery [31].

The fundamental principles of molecular docking revolve around exploring the ligand-receptor conformational space and evaluating interaction energetics through scoring functions [30]. Docking algorithms must navigate the complex energy landscape of intermolecular interactions, balancing computational efficiency with predictive accuracy. While early docking methods treated proteins as rigid bodies, contemporary approaches increasingly incorporate flexible docking strategies to account for induced fit effects and conformational changes that occur upon ligand binding [31] [30]. The remarkable success of molecular docking is exemplified by several FDA-approved drugs, including HIV-1 protease inhibitors such as amprenavir, thymidylate synthase inhibitor raltitrexed, and the antibiotic norfloxacin, all of which were developed using SBDD principles [32].

Current State of Molecular Docking Methods

Traditional Docking Approaches and Limitations

Traditional molecular docking methodologies, first introduced in the 1980s, primarily operate on a search-and-score framework that explores possible ligand conformations within the binding site and ranks them using empirical scoring functions [31] [30]. These methods face the significant challenge of navigating a high-dimensional conformational space while maintaining computational tractability. Early approaches addressed this complexity by treating both ligand and protein as rigid bodies, reducing the degrees of freedom to just six (three translational and three rotational) [31]. While computationally efficient, this simplification often resulted in poor predictive accuracy, as it failed to capture the induced fit effects that frequently accompany ligand binding [31].

To balance efficiency with accuracy, most modern conventional docking programs now allow ligand flexibility while maintaining protein rigidity [31]. These algorithms employ various conformational search strategies, including systematic, stochastic, and deterministic methods [30]. Despite these advances, modeling receptor flexibility remains a significant challenge for traditional docking approaches due to the exponential growth of the search space and limitations of conventional scoring algorithms [31]. This limitation is particularly problematic for cross-docking (docking to alternative receptor conformations) and apo-docking (using unbound receptor structures), where protein flexibility plays a crucial role in ligand binding [31].

Deep Learning Revolution in Molecular Docking

The groundbreaking success of AlphaFold2 in protein structure prediction has sparked a surge of interest in developing deep learning (DL) approaches for molecular docking [31]. These methods offer accuracy that rivals or even surpasses traditional approaches while significantly reducing computational costs [31]. Early DL-based docking models such as EquiBind (an equivariant graph neural network) and TankBind (which uses a trigonometry-aware GNN to predict distance matrices) demonstrated the potential of these approaches but often produced physically implausible complexes with improper bond angles and lengths [31].

The introduction of diffusion models, exemplified by DiffDock, represents a significant advancement in DL docking [31]. DiffDock employs an SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network to learn a denoising score function that iteratively refines the ligand's pose back to a plausible binding configuration [31]. This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy on benchmark datasets while operating at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional methods [31]. Nevertheless, DL-based docking still faces challenges in generalizing beyond training data and accurately predicting key molecular properties such as stereochemistry and steric interactions [31].

Performance Comparison of Docking Software

Table 1: Performance evaluation of molecular docking programs in reproducing experimental binding poses of COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors [33]

| Docking Program | Sampling Algorithm | Scoring Function | Performance (RMSD < 2Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | Systematic search | Empirical | 100% |

| GOLD | Genetic algorithm | Empirical | 82% |

| AutoDock | Genetic algorithm | Force field | 76% |

| FlexX | Incremental construction | Empirical | 73% |

| Molegro Virtual Docker | Differential evolution | Force field | 59% |

Table 2: Virtual screening performance of docking programs for COX targets [33]

| Docking Program | AUC Value Range | Enrichment Factor Range |

|---|---|---|

| Glide | 0.78-0.92 | 25-40x |

| GOLD | 0.71-0.85 | 15-30x |

| AutoDock | 0.65-0.79 | 10-25x |

| FlexX | 0.61-0.75 | 8-20x |

Evaluation studies comparing docking programs provide valuable insights for method selection. As shown in Table 1, a comprehensive assessment of five popular docking programs for predicting binding modes of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors revealed that Glide achieved the highest performance (100%) in reproducing experimental binding poses, defined by a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of less than 2Å between predicted and crystallized poses [33]. In virtual screening applications (Table 2), all tested methods demonstrated utility in classifying and enriching active molecules, with Glide again showing superior performance with area under the curve (AUC) values ranging from 0.78-0.92 and enrichment factors of 25-40 [33].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Molecular Docking Workflow

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for molecular docking and structure-based virtual screening, highlighting the integration of computational predictions with experimental validation.

Protein and Ligand Preparation Protocol

Protein Structure Preparation

- Source Selection: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, NMR, cryo-EM) or computational predictions (AlphaFold2, homology modeling) [32] [34]. For crystal structures, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the primary resource.

- Structure Processing: Remove redundant chains, crystallographic water molecules, and heteroatoms not involved in binding [33]. Add missing side chains or loops using modeling tools if necessary.

- Protonation and Optimization: Add hydrogen atoms, assign appropriate protonation states for ionizable residues (e.g., histidine tautomers), and optimize hydrogen bonding networks using tools like MolProbity [35].

- Energy Minimization: Perform limited energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while maintaining the overall protein fold.

Ligand Preparation

- Initial Structure Generation: Obtain 2D structures of small molecules from chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) and convert to 3D representations [36].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate multiple low-energy conformations using tools like BioChemicalLibrary (BCL), OpenEye MOE, or Frog 2.1 to account for ligand flexibility [35].

- Parameterization: Create force field parameters for novel ligands, including partial atomic charges, atom types, and rotatable bond definitions [35]. For Rosetta docking, generate .params files using the molfiletoparams.py script [35].

- Library Design: For virtual screening, prepare diverse compound libraries representing drug-like chemical space, typically ranging from thousands to billions of molecules [36].

Docking Execution and Analysis Protocol

Binding Site Identification

- Experimental Knowledge: Utilize information from co-crystallized ligands in analogous structures to define the binding site [32].

- Computational Prediction: Employ binding site detection algorithms like Q-SiteFinder, which calculates van der Waals interaction energies with a methyl probe to identify energetically favorable regions [32].

- Cryptic Pocket Detection: For proteins with transient binding sites, use methods like DynamicBind that employ equivariant geometric diffusion networks to model protein flexibility and reveal cryptic pockets [31].

Conformational Sampling and Pose Generation

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate search algorithms based on ligand flexibility and computational resources (see Section 4.1) [37] [30].

- Sampling Intensity: For rigid ligands, 10-20 independent docking runs may suffice, while highly flexible ligands may require 50-100 runs to adequately explore conformational space [36].

- Ensemble Docking: When available, use multiple protein conformations from molecular dynamics simulations or experimental structures to account for receptor flexibility [34].

Pose Scoring and Validation

- Multi-Method Scoring: Employ consensus scoring by combining results from multiple scoring functions to improve hit rates [33].

- Cluster Analysis: Group similar poses based on heavy atom RMSD (typically <2Å) and select representative poses from the largest clusters [33].

- Interaction Analysis: Manually inspect top-ranked poses for key molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking) and compare with known structure-activity relationships [29].

- Experimental Validation: Prioritize compounds for synthesis and experimental testing using biochemical or biophysical assays [32].

Application Notes for Specific Scenarios

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Targeting