Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Modern Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies, a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry and drug discovery.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Modern Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies, a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles that define how a compound's chemical structure influences its biological activity. The scope extends to contemporary methodological approaches, including quantitative SAR (QSAR), computational tools, and data analysis strategies for multi-parameter optimization. It further addresses common challenges in SAR analysis, offering troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and concludes with a critical evaluation of validation schemes and a comparative analysis with advanced modeling approaches like Proteochemometrics (PCM). This guide synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications to empower efficient and effective compound optimization.

SAR Fundamentals: Understanding the Core Principles of Structure-Activity Relationships

Defining Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) and Its Central Role in Medicinal Chemistry

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) is a fundamental concept in medicinal chemistry that describes the relationship between a molecule's chemical structure and its biological activity [1] [2]. This foundational principle operates on the core premise that specific modifications to a molecule's structure will produce predictable changes in its biological effects, whether beneficial (efficacy) or adverse (toxicity) [1] [3]. SAR analysis enables researchers to move beyond trial-and-error approaches, providing a systematic framework for understanding how drugs interact with their biological targets at a molecular level.

The importance of SAR in drug discovery and development cannot be overstated [1]. It serves as the intellectual framework that guides the optimization of potential drug candidates, helping medicinal chemists design compounds with improved potency, enhanced selectivity, and superior pharmacokinetic properties [2]. By establishing correlations between structural features and biological outcomes, SAR studies allow researchers to make informed decisions about which chemical modifications are most likely to yield successful therapeutic agents, ultimately reducing the time and resources required to bring new medicines to patients [1].

SAR represents the qualitative foundation upon which more advanced quantitative approaches are built. While SAR identifies which structural elements are important for activity, its quantitative counterpart, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), employs mathematical models to describe this relationship numerically, using molecular descriptors and statistical methods to predict the activity of untested compounds [2]. Together, these approaches form the cornerstone of rational drug design, enabling a more efficient and targeted approach to pharmaceutical development.

Foundational Principles of SAR

Core Concepts and Terminology

At the heart of SAR analysis lies the understanding that a compound's biological activity is dictated by its molecular structure. The "activity" refers to the measurable biological effect of a compound, such as its potency against a specific target, its binding affinity, or its ability to produce a therapeutic response [2]. The "structure" encompasses the complete three-dimensional arrangement of atoms, including their electronic properties, steric bulk, and functional groups that facilitate molecular recognition [1].

Several key concepts are essential for understanding SAR. The pharmacophore represents the minimal ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal molecular interactions with a specific biological target to elicit a biological response [4]. It is an abstract description of molecular features rather than a specific chemical structure. Bioisosteres are atoms, functional groups, or fragments that possess similar physical or chemical properties and often produce similar biological effects [4]. The concept of bioisosteric replacement, pioneered by Langmuir over a century ago, remains central to structural optimization in modern drug design, allowing chemists to maintain biological activity while improving drug-like properties [4].

Molecular descriptors quantitatively represent structural features and are crucial for both SAR and QSAR analyses [2]. These include physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), hydrogen bond donor/acceptor count, and polar surface area, as well as topological indices that capture aspects of molecular connectivity, branching patterns, and atom types [2]. Recent advances have introduced the concept of the "informacophore," which extends the traditional pharmacophore by incorporating data-driven insights derived not only from structure-activity relationships but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [4].

The SAR Analysis Workflow

The process of establishing and utilizing SAR follows a systematic, iterative workflow that transforms structural data into design decisions. This workflow can be visualized as follows:

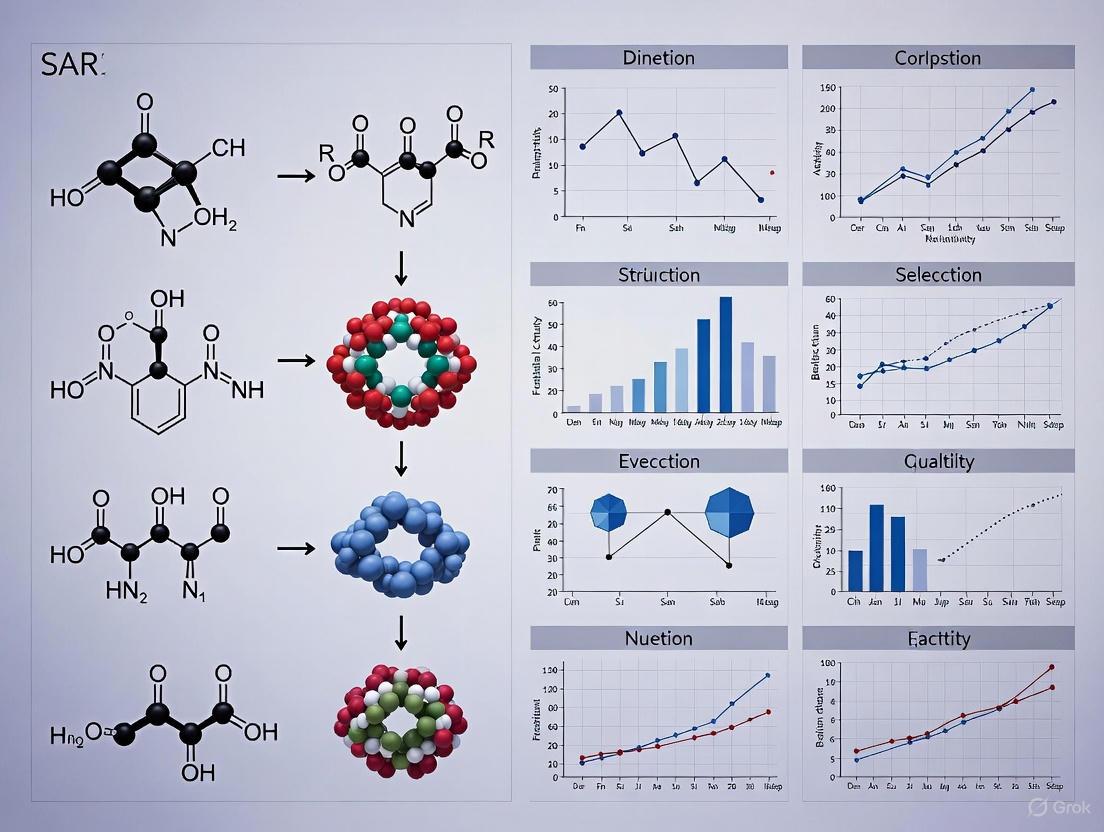

Figure 1: The iterative SAR analysis workflow for lead compound optimization

As illustrated in Figure 1, the SAR process begins with the screening of initial compounds and collection of bioactivity data across multiple parameters [5]. This data is systematically organized into SAR tables, which contain compounds, their physical properties, and activities, allowing experts to review information by sorting, graphing, and scanning structural features to identify potential relationships [3]. The critical analysis phase involves recognizing structural patterns that correlate with biological activity, enabling researchers to generate testable hypotheses about which structural modifications might enhance compound performance [1] [3].

Based on these hypotheses, new analogs are designed and synthesized, then subjected to biological testing to validate or refine the initial assumptions [1]. This iterative cycle continues until a compound meets the predefined optimization criteria for progression as a lead candidate. Modern implementations of this workflow, such as the PULSAR application developed by Discngine and Bayer, leverage advanced algorithms including Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) and Matched Molecular Series (MMS) to enable systematic, data-driven SAR analysis that integrates multiple parameters simultaneously [5].

Computational Approaches in SAR Analysis

From SAR to QSAR: Quantitative Modeling

While traditional SAR provides qualitative insights into structural requirements for biological activity, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a more sophisticated computational approach that establishes mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activities [2]. QSAR enables the prediction of biological properties for untested compounds based on their chemical structures, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [6] [7].

QSAR modeling begins with the calculation of molecular descriptors that numerically encode various aspects of chemical structure, from simple physicochemical properties to complex topological indices [2]. These descriptors serve as independent variables in statistical models where biological activity measurements (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) constitute the dependent variable. Various machine learning algorithms can be employed to establish the correlation between descriptors and activity, with model selection depending on the specific dataset and research objectives [6].

A recent study on Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (PfDHODH) inhibitors exemplifies modern QSAR methodology [6]. Researchers built 12 machine learning models from 12 sets of chemical fingerprints using a final set of 465 inhibitors. The study compared balanced and imbalanced datasets, with the balanced oversampling technique producing the best outcome (MCCtrain values >0.8 and MCCCV/MCCtest values >0.65). The Random Forest (RF) algorithm was selected for its optimal balance of performance and interpretability, achieving >80% accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in internal set, cross-validation, and external sets [6]. The SubstructureCount fingerprint provided the best overall performance, with MCC values of 0.76, 0.78, and 0.97 in the external set, cross-validation, and training internal sets, respectively [6].

Advanced 3D-QSAR Techniques

Beyond traditional 2D-QSAR methods, more advanced three-dimensional approaches account for the spatial orientation of molecular features. Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) is a 3D-QSAR technique that examines the relationship between a series of compounds' molecular fields (steric and electrostatic) and their biological activities [2]. By analyzing differences in these molecular fields, CoMFA identifies regions where structural modifications could enhance or reduce activity, providing visual guidance for molecular design [2].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends CoMFA by considering additional molecular fields, including hydrophobicity, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor properties [2]. This provides a more comprehensive understanding of SAR, allowing for the development of more effective drug candidates through multi-parameter optimization.

Key Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

Table 1: Essential molecular descriptors used in QSAR modeling

| Descriptor Category | Specific Descriptors | Biological/Physicochemical Significance | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Molecular weight, Atom count, Bond count | Molecular size, flexibility | Correlates with absorption and distribution |

| Topological | Molecular connectivity indices, Kier shape indices | Molecular branching, complexity | Predicts binding affinity and selectivity |

| Electronic | Partial atomic charges, HOMO/LUMO energies | Electronic distribution, reactivity | Determines interaction with binding site |

| Geometric | Principal moments of inertia, Molecular volume | 3D shape characteristics | Influences target complementarity |

| Hybrid | Aromatic moiety count, Chirality indicators | Specific structural features | PfDHODH inhibition [6]; TH system disruption [7] |

As shown in Table 1, molecular descriptors span multiple categories that capture different aspects of chemical structure. Recent research on PfDHODH inhibitors demonstrated that inhibitory activity was influenced by nitrogenous, fluorine, and oxygenation features in addition to aromatic moieties and chirality, as determined by the Gini index for feature importance assessment [6]. Similarly, QSAR studies on thyroid hormone (TH) system disruption have identified specific molecular descriptors that correlate with the potential of chemicals to interfere with TH synthesis, distribution, and receptor binding [7].

SAR in Drug Discovery Applications

Practical Implementation in Lead Optimization

The true value of SAR analysis is realized in its application to lead optimization, where initial hit compounds are systematically modified to improve their drug-like properties [2]. This process requires simultaneous optimization of multiple parameters, including potency against the primary target, selectivity over related off-targets, solubility, metabolic stability, and minimal toxicity [5].

In practice, medicinal chemists employ various structural modification strategies based on SAR findings. Functional group modifications involve replacing or altering specific functional groups to enhance interactions with the biological target or improve physicochemical properties [1]. Ring transformations focus on modifying core ring structures through bioisosteric replacement, ring expansion/contraction, or scaffold hopping to discover novel chemotypes with improved profiles [1]. Fragment-based approaches involve breaking down molecules into smaller fragments and analyzing their individual contributions to the overall biological activity, enabling the identification of key structural elements required for activity [2].

A case study from Bayer Crop Science illustrates the challenges and solutions in modern SAR analysis. Researchers faced difficulties in managing complex datasets containing thousands of compounds with multiple biochemical and biological parameters [5]. Using outdated, siloed technology made multi-objective SAR analysis slow and inefficient, with the entire process from analysis to presentation requiring multiple days [5]. The development of the PULSAR application, featuring MMP (Matched Molecular Pairs) and SAR Slides modules, addressed these challenges by enabling systematic, data-driven SAR analysis that integrates multiple parameters simultaneously [5]. This solution reduced analysis time from days to hours while improving visualization and collaboration capabilities [5].

SAR-Driven Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Systematic SAR Exploration

Compound Library Design: Create a focused library of analogs based on the initial hit structure. Include systematic variations at different regions of the molecule (core, side chains, functional groups) to probe SAR [1].

Data Generation and Management:

- Test all compounds in primary target assays (e.g., enzyme inhibition, receptor binding) to determine potency (IC₅₀, Ki values) [4].

- Assess selectivity against related off-targets to identify potential toxicity issues [3].

- Evaluate key ADMET properties (solubility, metabolic stability, membrane permeability) using in vitro assays [4].

- Centralize all data in a structured database with standardized formats to enable cross-assay analysis [5] [3].

SAR Analysis and Visualization:

- Construct SAR tables containing structures, properties, and activity data [3].

- Apply matched molecular pair analysis to identify structural changes that consistently improve specific properties [5].

- Use R-group deconvolution to systematically analyze the contribution of substituents at each position of the core scaffold [5].

- Generate SAR reports and visualizations that highlight key structure-activity trends for team discussions [5].

Hypothesis-Driven Design:

- Based on the SAR analysis, formulate specific hypotheses about which structural modifications will address remaining deficiencies.

- Prioritize synthetic targets that test these hypotheses while maintaining favorable structural features.

- Iterate through design-synthesis-test cycles until optimization goals are achieved [1].

Protocol for QSAR Model Development and Application

Data Curation and Preparation:

- Collect a homogeneous set of compounds with consistent activity measurements (e.g., IC₅₀ values from the same assay protocol) [6].

- Apply rigorous curation procedures to remove duplicates, correct errors, and ensure data quality.

- For unbalanced datasets, apply appropriate sampling techniques (oversampling or undersampling) to balance active and inactive compounds [6].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection:

- Compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors using cheminformatics software.

- Apply feature selection methods to identify the most relevant descriptors and reduce dimensionality.

- For large datasets, use chemical fingerprints (e.g., SubstructureCount fingerprint) to represent molecular structures [6].

Model Building and Validation:

- Split data into training, cross-validation, and external test sets [6].

- Train multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) on the training set [6].

- Evaluate model performance using appropriate metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, MCC values) across all data splits [6].

- Select the best-performing model based on robustness, predictive accuracy, and interpretability [6].

- Define the model's applicability domain to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable [7].

Model Application and Experimental Validation:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for SAR studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function in SAR Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Enamine "make-on-demand" library (65 billion compounds) [4], OTAVA library (55 billion compounds) [4] | Source of diverse compounds for screening and analog design |

| Bioinformatics Databases | ChEMBL database [6] | Repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties |

| Assay Systems | Enzyme inhibition assays, Cell viability assays, Binding affinity assays [4] | Generate quantitative activity data for SAR analysis |

| Cheminformatics Software | Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) algorithms [5], Molecular descriptor calculation tools | Identify structural relationships and compute molecular features |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Random Forest algorithms [6], Deep neural networks | Build predictive QSAR models for activity prediction |

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of SAR analysis is undergoing rapid transformation driven by advances in informatics, machine learning, and the availability of ultra-large chemical libraries [4]. Traditional approaches that relied heavily on medicinal chemists' intuition and experience are being augmented by data-driven methods that can identify complex patterns beyond human perception [4]. The development of ultra-large, "make-on-demand" virtual libraries containing tens of billions of synthesizable compounds has dramatically expanded the accessible chemical space for drug discovery [4].

Machine learning is revolutionizing SAR studies through the development of predictive models that can forecast biological activity based on chemical structure without prior knowledge of the basic principles governing drug function [4]. The concept of the "informacophore" represents a significant evolution from traditional pharmacophore approaches, combining minimal chemical structures with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations essential for biological activity [4]. This approach reduces biased intuitive decisions that may lead to systemic errors while accelerating the drug discovery process [4].

The synergy between computational predictions and experimental validation remains crucial for advancing SAR understanding [4]. As highlighted in several case studies, including the discovery of baricitinib for COVID-19 treatment and halicin as a novel antibiotic, computational predictions must be rigorously confirmed through biological functional assays [4]. These assays provide critical data on compound activity, potency, and mechanism of action, guiding medicinal chemists to design analogues with improved efficacy, selectivity, and safety [4].

Future directions in SAR research will likely focus on improving model interpretability, integrating multi-parameter optimization, and expanding into new therapeutic modalities. As chemical data continues to grow exponentially, SAR analysis will become increasingly predictive and comprehensive, ultimately reducing the time and cost required to bring new medicines to patients [1] [4].

Figure 2: Evolution of SAR methodologies from traditional to AI-driven approaches

Structure-Activity Relationship analysis represents the fundamental bridge between chemical structure and biological function in medicinal chemistry. From its origins as a qualitative framework based on chemical intuition, SAR has evolved into a sophisticated discipline incorporating quantitative modeling, machine learning, and large-scale informatics. The continued advancement of SAR methodologies, particularly through the integration of artificial intelligence and predictive modeling, promises to further accelerate drug discovery and development. As the field progresses, the synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation will remain essential for translating structural insights into therapeutic breakthroughs, ultimately enabling the design of more effective and safer medicines to address unmet medical needs.

In the realm of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies, the systematic analysis of key structural features of a molecule is fundamental to guiding the rational design and optimization of new therapeutic agents. SAR describes the direct relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its biological activity, a concept first presented by Alexander Crum Brown and Thomas Richard Fraser as early as 1868 [8]. The central premise is that the specific arrangement of atoms and functional groups dictates how a molecule interacts with biological systems, meaning even small structural changes can significantly alter its potency, selectivity, and metabolic stability [9] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to analyzing three core structural components—functional groups, pharmacophores, and stereochemistry—within the context of modern drug discovery. By detailing experimental protocols and visualization workflows, this document serves as a resource for researchers and scientists aiming to accelerate the critical pathway from hit identification to viable drug candidate [9].

Functional Group Analysis and Modification Strategies

Functional groups are specific substituents or moieties within a molecule that dictate its chemical reactivity and interactions with biological targets. Systematic modification of these groups is a primary tool in SAR studies for identifying essential features for biological activity and optimizing the drug-like properties of a lead compound [11] [12].

Probing Hydrogen-Bond Interactions

Hydrogen bonding is a critical non-covalent interaction that profoundly influences a ligand's binding affinity to its target. The methodology for probing the role of potential hydrogen-bonding functional groups involves synthesizing analogs where the group's ability to donate or accept hydrogen bonds is disrupted [12].

- Hydroxyl Groups: A phenolic or aliphatic hydroxyl can act as both a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor.

- To test its role as a hydrogen bond donor, the hydroxyl (-OH) is replaced with a methoxy group (-OCH₃) or a hydrogen atom (-H). A significant drop in biological activity suggests the proton of the hydroxyl is essential for binding, likely forming a critical hydrogen bond with the receptor [12]. For instance, in a series of pyrazolopyrimidines, replacing the phenolic OH with a methoxy group led to a complete loss of biological activity [12].

- Testing its role as a hydrogen bond acceptor is less straightforward, as common alterations like methylation or removal do not eliminate the oxygen atom, which can still serve as an acceptor [12].

- Carbonyl Groups: A carbonyl group (C=O) acts primarily as a strong hydrogen bond acceptor.

- Its role is tested by reducing it to an alcohol (CH-OH), which can only act as a donor, or by replacing it with a methylene group (CH₂ or C=CH₂). A substantial decrease in activity upon such modification indicates the carbonyl is likely involved in a key hydrogen bonding interaction with the target protein [12]. This was observed in studies of aminobenzophenones, where the carbonyl was critical for activity [12].

Key Modification Strategies

Beyond probing specific interactions, broader strategies are employed to refine lead compounds.

- Bioisosteric Replacement: This involves replacing a functional group or atom with another that has similar physicochemical properties but potentially improved biological activity or drug-likeness. Bioisosteres can enhance efficacy, reduce toxicity, or improve metabolic stability [11] [10].

- Homologation and Chain Branching: Adding a methylene group (-CH₂-) to an alkyl chain (homologation) or introducing branch points can affect the molecule's steric bulk, conformational flexibility, and overall shape. These changes can enhance potency or selectivity by optimizing the molecule's fit within its target binding site [11].

- Ring Size and Fusion Modifications: Altering the size of a ring system or creating fused rings can dramatically impact molecular rigidity and the spatial orientation of key pharmacophoric elements. This can lead to improved binding affinity and selectivity [11].

Table 1: Summary of Common Functional Group Modifications and Their Interpretations in SAR Studies

| Functional Group | Type of Modification | Objective of Modification | Interpretation of Activity Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl (-OH) | Replace with -OCH₃ or -H | Test role as H-bond donor | ↓ Activity suggests group is critical H-bond donor |

| Carbonyl (C=O) | Reduce to CH-OH; replace with CH₂ | Test role as H-bond acceptor | ↓ Activity suggests group is critical H-bond acceptor |

| Aromatic Ring | Alter substituents (e.g., -Cl, -CH₃, -OH) | Probe electronic, steric, and hydrophobic effects | Identifies optimal substituents for binding and properties |

| Alkyl Chain | Homologation (-CH₂- addition) or branching | Modulate lipophilicity, flexibility, and steric fit | Identifies optimal chain length/branching for potency/ADME |

Pharmacophore Identification and Modeling

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the essential molecular features necessary for a compound to interact with a biological target and elicit a specific response. It is not a specific chemical structure, but a map of hydrophobic regions, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, positively charged groups, and negatively charged groups that a molecule must possess to be biologically active [11]. Identifying the pharmacophore is a critical step in SAR analysis, as it provides a blueprint for designing new compounds with similar or improved activity [11] [12].

The process of pharmacophore identification is ligand-based when the 3D structure of the target is unknown. It involves analyzing the structural commonalities among a set of known active compounds. By superimposing these active molecules, researchers can identify the spatial arrangement of key functional groups that are common to all, thus defining the core pharmacophore [12]. When the 3D structure of the target is available, a structure-based approach can be used, where the pharmacophore model is derived directly from the analysis of the binding site, identifying key residues with which the ligand interacts [9].

The Critical Role of Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry refers to the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in a molecule. In drug discovery, this is paramount because biological systems are inherently chiral; proteins, enzymes, and receptors are composed of L-amino acids and can distinguish between enantiomers—stereoisomers that are non-superimposable mirror images [13].

Stereochemistry in SAR and Lead Optimization

When a pharmacophore contains one or more stereocenters, each stereoisomer must be considered a distinct molecular entity in SAR exploration [13]. A common pattern is for one enantiomer (the eutomer) to possess significantly greater activity and binding affinity than its mirror image (the distomer). The eudismic ratio (the activity ratio of eutomer to distomer) quantifies this enantioselectivity [13]. For example, in early β-blocker development, activity was found to reside predominantly in the (S)-enantiomers [13].

Medicinal chemists employ several strategies to manage stereochemistry:

- Resolution of Racemates: A racemic hit from a screen is separated into its individual enantiomers using techniques like chiral chromatography to identify the active component [13].

- Asymmetric Synthesis: Designing synthetic routes that produce a single, desired enantiomer from the outset, focusing resources on the optimal stereochemical series [13].

- Stereochemical Libraries: For molecules with multiple stereocenters, creating libraries that include key stereoisomers (e.g., cis/trans or different diastereomers) to map the "chiral SAR" and identify the optimal 3D configuration [13].

Regulatory and Practical Considerations

Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA require strict control over the stereochemical composition of drug substances. Sponsors must identify the stereochemistry, develop chiral analytical methods early, and justify the development of a racemate over a single enantiomer [13]. From a practical screening perspective, the choice between screening single enantiomers versus racemates involves a trade-off. Screening single enantiomers provides clear data but doubles the library size and cost. Screening racemates is more efficient initially but requires follow-up "deconvolution" to identify the active enantiomer, with the risk that opposing activities of the two enantiomers could mask a true hit [13].

Table 2: Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing Key Structural Features

| Structural Feature | Primary Experimental Method/s | Key Data Output | Role in SAR Elucidation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Groups / Pharmacophore | Systematic analog synthesis & biological testing (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) [12]; Site-directed mutagenesis (for target) | Potency, efficacy, and selectivity data; Identification of critical groups | Defines essential chemical features for target interaction and biological activity |

| Stereochemistry | Chiral resolution (HPLC, SFC); Asymmetric synthesis; X-ray Crystallography [13] | Activity data for individual stereoisomers; Eudismic ratio | Determines the 3D spatial configuration required for optimal binding and efficacy |

| Target Binding Mode | X-ray Crystallography; Cryo-EM; NMR Spectroscopy; Molecular Docking [9] | High-resolution 3D structure of ligand-target complex | Visualizes atomic-level interactions, rationalizes observed SAR, and guides design |

Integrated Workflow and The Scientist's Toolkit

Modern SAR analysis is an iterative "Design-Make-Test-Analyze" (DMTA) cycle, powered by the integration of experimental and computational methods [14] [9]. The workflow begins with designing analogs based on a hypothesis, synthesizing them, testing their biological activity in relevant assays, and then analyzing the resulting data to inform the next design cycle [9]. Advanced computational tools are used throughout this process to model interactions, predict activities, and prioritize compounds for synthesis [14] [9].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SAR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in SAR Studies |

|---|---|

| Chiral Chromatography Columns | Separation and analytical quantification of individual enantiomers from racemic mixtures [13]. |

| Chiral Solvents & Auxiliaries | Utilization in asymmetric synthesis to produce specific, enantioenriched stereoisomers [13]. |

| Stable Isotope-labeled Compounds | Use as internal standards in mass spectrometry for precise bioanalytical and metabolomic studies [15]. |

| Functional Group-specific Reagents | Reagents for targeted chemical modifications (e.g., acylating, alkylating agents) to probe group importance [12]. |

| High-Purity Building Blocks | Commercially available or synthesized chemical fragments for constructing diverse analog libraries [9]. |

| Crystallography Reagents | Crystallization screens and cryo-protectants for obtaining ligand-target complex structures [9]. |

The meticulous analysis of functional groups, pharmacophores, and stereochemistry forms the bedrock of successful SAR studies in drug discovery. By systematically deconstructing and modifying these key structural features through iterative DMTA cycles, researchers can transform an initial active compound into a optimized lead candidate with enhanced potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties. The integration of robust experimental methodologies—from chiral resolution to hydrogen bond probing—with powerful computational modeling and a clear understanding of regulatory requirements provides a comprehensive framework for navigating the vast chemical space. As exemplified by recent research on natural products like chabrolonaphthoquinone B, this disciplined approach continues to uncover novel mechanisms of action and drive the development of life-saving therapeutics [15].

The Impact of Molecular Modifications on Biological Activity, Efficacy, and Toxicity

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies represent a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and development, providing a systematic framework for understanding how the chemical structure of a compound influences its biological activity [10]. At its core, SAR analysis investigates the correlation between a molecule's chemical structure and its biological effect, enabling researchers to optimize therapeutic effectiveness while minimizing undesirable properties [14]. This fundamental principle underpins the entire drug development process, from initial lead identification to final candidate optimization. The ability to rationally modify molecular structures to enhance efficacy, reduce toxicity, and improve pharmacokinetic properties has revolutionized pharmaceutical development, making SAR an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) extends this concept further by employing mathematical models and molecular descriptors to quantitatively predict biological activity based on chemical structure [16] [10]. Over the past six decades, the QSAR field has undergone significant transformation, evolving from simple linear models based on a few physicochemical parameters to complex machine learning algorithms capable of processing thousands of chemical descriptors [16]. This evolution has expanded the scope and precision of molecular modification strategies, allowing for more sophisticated and predictive approaches to drug design. The development of high-throughput screening technologies and advanced computational methods has further enhanced our ability to explore chemical space efficiently, providing unprecedented insights into the complex relationships between molecular structure and biological function [14].

This technical guide examines the multifaceted impact of molecular modifications on biological activity, efficacy, and toxicity, framing this discussion within the broader context of SAR research. By integrating fundamental principles with advanced methodologies and practical applications, this review aims to provide researchers with a comprehensive understanding of how strategic structural alterations can optimize therapeutic potential while mitigating risks, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective pharmaceutical agents.

Fundamental Principles of Structure-Activity Relationships

Key Concepts and Definitions

The foundation of SAR analysis rests on several key concepts that govern the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity. A Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) is fundamentally defined as the correlation between a molecule's chemical structure and its biological effect [10]. This relationship enables researchers to identify which structural components are essential for biological activity and which modifications may enhance or diminish that activity. When this concept is extended to mathematical models that quantitatively predict biological activity based on molecular descriptors, it becomes Quantitative SAR (QSAR) [16] [10]. QSAR models utilize various computational techniques to establish quantitative relationships between structural parameters and biological responses, allowing for more precise predictions of compound behavior.

The principle of bioisosteric replacement represents a crucial strategy in molecular modification, involving the substitution of atoms or groups with others that have similar physicochemical properties, often leading to improved drug characteristics such as enhanced potency, reduced toxicity, or better bioavailability [10]. This approach allows medicinal chemists to make strategic modifications while preserving desired biological activity. Another critical concept is the activity cliff, which refers to a small structural change that causes a significant, disproportionate shift in biological activity [10]. These cliffs are particularly important in drug optimization as they highlight specific molecular features that dramatically influence compound potency or efficacy.

The domain of applicability (DA) defines the chemical space within which a QSAR model's predictions can be considered reliable [14]. This concept is essential for ensuring the appropriate application of computational models, as predictions for molecules outside this domain may be unreliable or meaningless. Understanding a model's domain of applicability helps researchers determine when a model should be rebuilt or updated based on new chemical data [14].

The Molecular Basis of SAR

The relationship between chemical structure and biological activity ultimately stems from molecular interactions between a compound and its biological target. When a small molecule (ligand) interacts with a protein receptor, enzyme, or nucleic acid, the complementarity of their interaction determines the biological response. Key molecular properties that govern these interactions include hydrophobicity, which influences membrane permeability and target binding; electronic effects, which determine charge distribution and molecular reactivity; and steric factors, which govern the spatial fit between ligand and target [17] [16].

Hydrophobicity is commonly quantified using the partition coefficient (P), measured as the ratio of concentrations of a compound in octanol and water, with log P serving as a numerical scale [17]. The relationship between log P (hydrophobicity) and biologic activity typically follows a parabolic pattern—activity increases with log P until reaching an optimal point (log Po), beyond which further increases in hydrophobicity diminish activity [17]. This parabolic relationship reflects the balance needed for a compound to cross lipid membranes yet remain sufficiently soluble in aqueous compartments to reach its target.

Electronic effects influence reactivity through electron-withdrawing or electron-donating properties of substituents, which can dramatically alter biological activity depending on the mechanism of action [17]. For instance, strong electron withdrawal enhances mutagenicity in cis-platinum ammines but reduces it in triazines, demonstrating that the same substituent can have opposite effects in different chemical classes [17]. Steric factors, including stereochemistry, further modulate biological interactions, as evidenced by dramatic activity differences between stereoisomers that contain identical molecular fragments but in mirror-image arrangements [17].

Methodologies for SAR Exploration

Computational Approaches

Computational methods for SAR exploration have evolved significantly, ranging from simple regression models to complex machine learning algorithms. These approaches can be broadly divided into two groups: those based on statistical or data mining methods (e.g., regression models) and those based on physical approaches (e.g., pharmacophore models) [14].

Traditional QSAR Modeling primarily utilizes statistical techniques that link chemical structures, characterized by numerical descriptors, to biological activities [14]. Early approaches like Hansch analysis employed physicochemical parameters such as lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects to predict biological activity [16]. Modern implementations include various forms of linear regression (ordinary least squares, PLS, ridge regression) and non-linear methods (neural networks, support vector machines) that can capture complex structure-activity relationships [14].

Machine Learning in QSAR has revolutionized the field, with algorithms like Random Forest demonstrating strong performance in classifying active versus inactive compounds [6]. These approaches can process thousands of chemical descriptors and identify complex patterns that may not be apparent through traditional methods. For example, in developing inhibitors for Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (PfDHODH), Random Forest models achieved high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity by identifying key molecular features such as nitrogenous groups, fluorine atoms, oxygenated features, aromatic moieties, and chiral centers [6].

Inverse QSAR represents an alternative approach that identifies structures matching a given activity profile rather than predicting activity from structure [14]. Methods like the signature molecular descriptors [14] and novel descriptors coupled with kernel methods [14] have been developed to address the challenge of generating valid chemical structures from optimized descriptor values.

SAR Landscape Visualization provides an alternative view of SAR data by representing structure and activity simultaneously in a landscape format, with structure in the X-Y plane and activity along the Z-axis [14]. This approach allows researchers to visualize regions where similar structures show similar activities (smooth regions) versus areas where small structural changes cause dramatic activity shifts (jagged regions) [14].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for developing and applying QSAR models in drug discovery:

Experimental Approaches

Experimental methods for SAR exploration provide critical validation for computational predictions and generate essential data for model development.

Functional Group Modification involves systematically altering chemical groups to test their impact on biological activity [10]. This fundamental approach helps identify key functional groups responsible for activity and provides insights into how specific structural elements contribute to binding interactions and efficacy. For example, in thiochromanone derivatives, the presence of a chlorine group at the 6th position and a carboxylate group at the 2nd position significantly enhanced antibacterial activity [18].

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) enables the rapid testing of compound libraries to build comprehensive SAR datasets [10]. Modern HTS can generate data for hundreds of chemical series simultaneously, providing rich information for SAR analysis [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying promising lead compounds from large collections and establishing initial SAR trends.

Structural Activity Landscape Analysis represents an advanced experimental approach that views chemical structure and bioactivity simultaneously in a 3D landscape format [14]. This methodology, stemming from the work of Lajiness, enables researchers to visualize regions of continuous activity changes ("smooth regions") versus areas where small structural modifications cause dramatic activity shifts ("activity cliffs") [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SAR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in SAR Studies | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Quantifies structural features for QSAR modeling | Dragon, PaDEL, RDKit [16] |

| QSAR Modeling Platforms | Develops predictive models from structural data | WEKA, KNIME, Orange [16] |

| Compound Libraries | Provides diverse structures for screening | Commercial libraries, in-house collections [14] [10] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Measures biological activity in physiological context | Enzyme inhibition, cell proliferation, reporter assays [14] |

| Chemical Synthesis Reagents | Enables structural modification of lead compounds | Custom synthesis, bioisosteric replacement [18] [10] |

| Structural Biology Tools | Determines 3D structure of target-ligand complexes | X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, NMR [14] |

Impact of Specific Molecular Modifications

Functional Group Modifications and Electronic Effects

Strategic modification of functional groups represents one of the most powerful approaches for optimizing biological activity. The introduction of electron-withdrawing groups often significantly enhances potency by modifying electron distribution and influencing interactions with biological targets. In thiochromene and thiochromane derivatives, electron-withdrawing substituents have been shown to enhance bioactivity, potency, and target specificity across various therapeutic applications [18]. For antibacterial thiochromanone derivatives containing an acylhydrazone moiety, the presence of a chlorine group at the 6th position and a carboxylate group at the 2nd position significantly enhanced antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae [18].

Sulfur oxidation state changes represent another impactful modification strategy. The oxidation of thioethers to sulfoxides or sulfones can dramatically alter electronic properties, polarity, and molecular geometry, leading to significant changes in biological activity [18]. In sulfur-containing heterocycles like thiochromenes and thiochromanes, these modifications enhance interactions with biological targets through improved hydrogen bonding capacity and altered electron distribution [18].

The following table summarizes the effects of common functional group modifications on biological activity:

Table 2: Impact of Functional Group Modifications on Biological Activity

| Modification Type | Structural Effect | Biological Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron-Withdrawing Group Introduction | Alters electron distribution, enhances polarity | Often increases potency; can improve target binding | -Cl at 6th position of thiochromanone enhances antibacterial activity [18] |

| Sulfur Oxidation | Increases polarity, alters molecular geometry | Modulates target interactions, affects membrane permeability | Oxidation of thiochromenes enhances bioactivity [18] |

| Bioisosteric Replacement | Maintains similar physicochemical properties | Preserves activity while improving ADMET properties | Replacing metabolically labile groups with stable isosteres [10] |

| Ring Substitution | Modifies steric bulk and conformational flexibility | Enhances selectivity, reduces off-target effects | Tailored ring substitutions in thiochromanes improve target specificity [18] |

| Chirality Introduction | Creates stereospecific centers | Dramatically affects potency and selectivity; one enantiomer often more active [17] |

Structural Scaffold Modifications

Modifications to core molecular scaffolds can profoundly influence biological activity by altering overall molecular shape, flexibility, and interaction capabilities. The incorporation of sulfur into heterocyclic frameworks introduces significant modifications to electronic distribution and enhances lipophilicity, often leading to improved membrane permeability and bioavailability [18]. Thiochromenes and thiochromanes, as sulfur-containing heterocycles, demonstrate how scaffold modifications can expand therapeutic potential across various applications, including anticancer, antimicrobial, and other pharmacological activities [18].

Saturation level changes in ring systems represent another important structural modification strategy. Thiochromanes, as saturated derivatives of thiochromenes, offer additional flexibility in terms of stereochemistry which can be exploited to enhance drug-receptor interactions and improve pharmacokinetic properties [18]. The expanded structural diversity provided by saturation enhances biological relevance and provides more opportunities for optimizing therapeutic potential.

Ring fusion and spacer modifications can significantly alter biological activity by constraining molecular conformation or adjusting the distance between key functional groups. In oleanolic acid derivatives, the introduction of heterocyclic rings and conjugation with other bioactive molecules has led to enhanced cytotoxic activity, antiviral effects, and improved pharmacokinetic properties [19]. These structural modifications leverage the inherent bioactivity of natural product scaffolds while addressing limitations such as poor solubility or low potency.

Stereochemical Modifications

Stereochemistry plays a crucial role in biological activity, with enantiomers often exhibiting dramatic differences in potency, efficacy, and toxicity. The principle of "lock-and-key" fit between biologically active compounds and their receptors remains valid, with molecular flexibility adding complexity to these interactions [17]. Even compounds containing identical molecular fragments can show huge differences in activity depending on their spatial arrangement, highlighting the importance of stereospecific recognition in biological systems [17].

Strategic introduction of chiral centers can enhance specificity and reduce off-target effects. In some cases, specific stereoisomers may interact preferentially with the intended biological target while having minimal interaction with off-target receptors, thereby improving therapeutic index. Quantitative SAR work with stereoisomers is possible when the mechanism of action is uniform throughout the compound series, allowing for rational optimization of stereochemical features [17].

SAR in Lead Optimization and Toxicity Assessment

Optimizing Efficacy and Pharmacokinetic Properties

Lead optimization through SAR represents a critical phase in drug discovery where initial hit compounds are systematically modified to improve efficacy, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties. This process involves simultaneous optimization of multiple physicochemical and biological properties, including potency, toxicity reduction, and sufficient bioavailability [14]. SAR analysis guides this multivariate optimization by identifying which structural modifications positively influence desired properties while minimizing negative effects.

Key strategies for enhancing efficacy include potency optimization through targeted modifications that strengthen interactions with the biological target. For example, in thiochromane derivatives, specific molecular modifications have been shown to enhance bioactivity and target specificity, leading to improved therapeutic potential [18]. Selectivity enhancement addresses the challenge of off-target effects by modifying structures to increase specificity for the intended target over related biological structures. This often involves introducing steric hindrance or specific functional groups that discriminate between similar binding sites.

SAR-guided approaches also focus on improving pharmacokinetic properties, including enhanced metabolic stability through the introduction of metabolically resistant groups or bioisosteric replacements [10]. Improved bioavailability can be achieved by modifying hydrophobicity (log P) to fall within the optimal range for membrane permeability while maintaining sufficient aqueous solubility [17]. Additionally, half-life extension strategies include structural modifications that reduce clearance, such as glycosylation to reduce renal clearance or introduction of groups that increase plasma protein binding [20].

Toxicity Mitigation through SAR

SAR analysis plays a crucial role in identifying and mitigating potential toxicity issues in drug candidates. Understanding the relationship between chemical structure and toxicological outcomes enables researchers to proactively design safer compounds while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Structural Alerts Identification involves recognizing molecular fragments associated with toxicity, such as reactive functional groups that can form covalent bonds with biological macromolecules or specific substructures linked to mutagenicity [17]. For example, the hydroxyl (OH) group demonstrates dramatically different toxicity profiles depending on its molecular context—from the minimal toxicity of water (HOH) to the significant toxicity of medium-chain alcohols (ROH with 1-10 carbon atoms) to the decreasing toxicity of longer-chain alcohols [17]. This context-dependent toxicity highlights the importance of evaluating functional groups within their molecular environment rather than assigning fixed toxicity weights.

Mechanism-Based Toxicity Reduction focuses on structural modifications that specifically address identified toxicity mechanisms. For instance, in therapeutic proteins, strategies to reduce immunogenicity include knocking down CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase to prevent the conversion of Neu5Ac to Neu5Gc, which can elicit immune responses [20]. Similarly, engineering protease-resistant mutants by modifying specific amino acid residues can prevent unwanted degradation and generate potentially immunogenic fragments [20].

Selectivity Enhancement reduces off-target toxicity by increasing a compound's specificity for its intended target. This approach includes structural modifications that enhance discrimination between related biological targets, such as introducing specific steric hindrance or functional groups that preferentially interact with the target of interest while minimizing interactions with off-target receptors [10].

The following diagram illustrates the integration of efficacy optimization and toxicity assessment in the lead optimization process:

Quantitative Approaches to Toxicity Prediction

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models have become invaluable tools for predicting potential toxicity of chemical substances during early development stages. These computational approaches are particularly important for addressing endocrine disruption, carcinogenicity, and other complex toxicological endpoints.

For thyroid hormone system disruption, QSAR models have been developed to predict molecular initiating events within the adverse outcome pathway framework [21]. These models support chemical hazard assessment while reducing reliance on animal-based testing methods, aligning with the principles of green chemistry and the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [21].

The development of robust QSAR models for toxicity prediction requires careful consideration of several factors, including endpoint selection based on clear biological mechanisms and high-quality experimental data [21]. Appropriate descriptor selection must capture relevant molecular features associated with toxicity mechanisms while maintaining interpretability [16]. Defining the domain of applicability ensures that predictions are only made for compounds within the chemical space adequately represented in the training data [14]. Proper validation protocols using external test sets and statistical measures provide confidence in model predictions and help avoid overoptimistic performance estimates [16] [6].

Experimental Protocols for Key SAR Methodologies

Protocol for QSAR Model Development and Validation

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for developing and validating QSAR models based on established best practices and recent advances in the field [16] [6].

Step 1: Data Curation and Preparation

- Collect biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) from reliable sources such as ChEMBL or PubChem

- Curate the dataset to remove duplicates, compounds with uncertain activity values, and potential errors

- For classification models, define activity thresholds based on biological and statistical considerations

- Apply chemical standardization to ensure consistent representation of structures

- Separate data into training (~70-80%), validation (~10-15%), and test sets (~10-15%) using rational splitting methods

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Calculate molecular descriptors using software such as Dragon, PaDEL, or RDKit

- Consider diverse descriptor types including 0D (constitutional), 1D (functional groups), 2D (topological), and 3D (geometric) descriptors

- Preprocess descriptors by removing constant or near-constant variables

- Apply feature selection methods (e.g., correlation analysis, genetic algorithms, random forest importance) to reduce dimensionality and minimize overfitting

Step 3: Model Building and Training

- Select appropriate algorithms based on dataset size, descriptor type, and modeling objective

- For linear relationships, consider Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) or Partial Least Squares (PLS)

- For complex nonlinear relationships, apply machine learning methods such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), or Neural Networks

- Optimize model hyperparameters using cross-validation or optimization algorithms

Step 4: Model Validation and Applicability Domain Definition

- Assess model performance using appropriate metrics: R² and RMSE for regression; accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and MCC for classification

- Perform internal validation using cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold)

- Conduct external validation using the held-out test set to evaluate predictive ability

- Define the applicability domain using methods such as leverage, similarity distance, or descriptor range analysis

Step 5: Model Interpretation and Application

- Interpret important descriptors in the context of biological mechanisms

- Visualize SAR trends using methods such as the "glowing molecule" representation [14]

- Apply the model to predict activity of new compounds within the applicability domain

- Document model parameters, validation results, and limitations for regulatory submission if required

Protocol for Functional Group Modification Studies

This protocol provides a framework for systematically evaluating the impact of functional group modifications on biological activity [18] [10].

Step 1: Strategic Design of Analogues

- Identify the core scaffold and potential modification sites based on existing SAR knowledge

- Plan specific modifications targeting key properties: electron-withdrawing/donating groups, hydrophobic/hydrophilic groups, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Include bioisosteric replacements to explore isofunctional alternatives

- Design stereochemical modifications if chiral centers are present or can be introduced

Step 2: Synthesis or Acquisition of Analogues

- Synthesize planned analogues using appropriate organic chemistry methods

- For complex modifications, consider computational guidance for synthetic feasibility

- Alternatively, source commercially available analogues when possible

- Verify compound identity and purity using analytical methods (NMR, LC-MS, HPLC)

Step 3: Biological Evaluation

- Test all analogues in relevant biological assays under consistent conditions

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls in each experiment

- Perform dose-response studies to obtain quantitative activity measures (IC50, EC50, Ki)

- Assess selectivity against related targets or cell types when possible

Step 4: SAR Analysis and Interpretation

- Correlate structural modifications with changes in biological activity

- Identify activity cliffs—small changes causing large activity shifts

- Group compounds by common structural features and analyze trends

- Develop hypotheses about mechanism of action based on modification effects

Step 5: Iterative Optimization

- Use initial SAR findings to design next-generation analogues

- Focus on promising modification sites that showed significant activity improvements

- Address potential toxicity or physicochemical issues identified in initial series

- Continue cycles of modification and testing until optimization goals are met

The strategic implementation of molecular modifications guided by comprehensive SAR analysis remains fundamental to advancing drug discovery and development. Through systematic exploration of chemical space, researchers can optimize biological activity, enhance therapeutic efficacy, and mitigate potential toxicity. The continued evolution of computational methods, including machine learning and advanced visualization techniques, has significantly enhanced our ability to predict and interpret the complex relationships between chemical structure and biological response. As these methodologies advance, integrating multi-parameter optimization and leveraging growing chemical and biological datasets, SAR-driven approaches will continue to play a pivotal role in addressing the challenges of modern drug development and delivering safer, more effective therapeutics.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies represent a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry, providing a systematic framework for understanding how the chemical structure of a molecule influences its biological activity. For decades, SAR has been instrumental in guiding the optimization of lead compounds into safe and effective therapeutics, particularly in the critical fields of oncology and infectious diseases. This whitepaper details key historical success stories where SAR-driven optimization led to breakthrough antibiotics and anticancer agents, highlighting the methodologies, challenges, and transformative outcomes that have shaped contemporary drug discovery paradigms. By tracing the evolution of specific drug classes, this review underscores the enduring value of SAR as a fundamental tool for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to navigate the complex landscape of molecular design.

SAR in Anticancer Drug Development

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: The Imatinib Story

The development of Imatinib (Gleevec) for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) stands as a seminal achievement in precision oncology and SAR-driven drug design. CML is characterized by the BCR-ABL fusion oncoprotein, a constitutively active tyrosine kinase. Initial lead compounds were weak inhibitors of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site [22].

Critical SAR Insights and Optimization:

- Core Scaffold Modification: Researchers systematically modified the 2-phenylaminopyrimidine core to enhance binding affinity and specificity.

- Benzamide Side Chain Addition: Introduction of a methylbenzamide group extended into a deep hydrophobic pocket of the ABL kinase domain, significantly improving potency.

- "Flag Methyl" Group: A single methyl group on the piperazine ring (optimizing log P) improved oral bioavailability and optimized pharmacokinetic properties [22].

This rational, structure-based optimization resulted in Imatinib, a potent and selective BCR-ABL inhibitor that achieved remarkable clinical success and established a new paradigm for targeted cancer therapy [22].

Table 1: SAR-Driven Optimization of Imatinib

| Structural Feature | Initial Lead Compound | Optimized in Imatinib | Impact on Drug Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Scaffold | 2-phenylaminopyrimidine | 2-phenylaminopyrimidine (retained) | Maintains key interactions with kinase hinge region |

| Benzamide Group | Absent | Added (N-methylpiperazine) | Fills hydrophobic pocket II, drastically increasing potency & selectivity |

| "Flag Methyl" Group | Absent | Added on piperazine ring | Optimized log P, improved oral bioavailability |

| Toluenesulfonamide | Present | Replaced with benzamide | Improved metabolic stability and reduced toxicity |

Marine Natural Products and the Case of Ecteinascidin 743

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, Trabectedin), isolated from the marine tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata, was the first marine-derived anticancer drug to gain clinical approval for advanced soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer [23]. Its complex pentacyclic tetrahydroisoquinoline structure posed significant supply challenges, making total synthesis and SAR studies essential for both ensuring supply and exploring analogs [23].

Key SAR Findings from Structural Modifications:

- Tetrahydroisoquinoline Core: The core is essential for DNA minor groove binding and alkylation. The C-ring is critical for intercalation and stabilizing the drug-DNA complex.

- N12 Cation: The positively charged nitrogen at position 12 is crucial for the initial electrostatic attraction to the negatively charged DNA backbone.

- C21 Substituent: Modifications at C21 can profoundly affect cytotoxicity and the therapeutic window. For instance, the analog Phthalascidin (Pt-650) exhibited comparable potency and a similar mechanism of action to ET-743, validating the scaffold's potential for optimization [23].

These SAR insights, gleaned from sophisticated total synthesis campaigns, have provided a roadmap for developing next-generation analogs with improved efficacy or reduced toxicity profiles.

The Rise of Targeted Protein Degradation: PROTACs

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a paradigm shift beyond inhibition, leveraging SAR to design bifunctional molecules that induce targeted protein degradation. A PROTAC molecule consists of three key elements linked in a single chain [22].

SAR Considerations for PROTACs:

- Warhead Selection: The ligand for the target protein (e.g., a kinase inhibitor) must be optimized for binding affinity and selectivity.

- E3 Ligase Ligand: The ligand that recruits a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase (e.g., von Hippel-Lindau or cereblon) is chosen based on efficiency and tissue distribution.

- Linker Chemistry: The length, composition, and atom connectivity of the linker are critical for forming a productive ternary complex. SAR studies focus on optimizing linker flexibility/rigidity to ensure proper spatial orientation for ubiquitin transfer [22].

This innovative approach, heavily reliant on advanced SAR, has opened the door to targeting previously "undruggable" proteins, such as transcription factors and scaffold proteins.

SAR in Antibiotic Drug Development

Overcoming β-Lactam Resistance

β-lactam antibiotics, one of the most successful drug classes, face relentless challenges from bacterial resistance, primarily through β-lactamase enzymes. SAR studies have been pivotal in developing agents that overcome this resistance [24].

SAR of β-Lactamase Inhibitors:

- Shared β-Lactam Core: Inhibitors like clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam retain the fundamental β-lactam ring, which acts as a sacrificial substrate.

- Electrophilic "Warhead": Strategic modifications (e.g., the oxazolidine ring in clavulanic acid) enhance the inhibitor's reactivity with the β-lactamase serine residue, leading to irreversible inactivation.

- Recent Advances: Newer inhibitors such as avibactam feature a non-β-lactam core (diazabicyclooctane) but maintain the ability to acylate the catalytic serine, with the key SAR advantage of being recyclable, providing prolonged inhibition [24].

Table 2: SAR-Driven Evolution of Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors

| Inhibitor Generation | Example Drug | Core Structure | Key SAR Feature | Mechanism of Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Clavulanic Acid | β-Lactam | Oxazolidine ring | Irreversible, suicide inactivation of serine β-lactamases (SBLs) |

| Second Generation | Tazobactam | β-Lactam | Triazolyl group; improved stability | Broader spectrum against SBLs compared to first-gen |

| Third Generation | Avibactam | Non-β-Lactam (Diazabicyclooctane) | Recyclable from its acyl-enzyme complex | Reversible covalent inhibition; effective against Class A, C, and some D SBLs |

Fluoroquinolones: Enhancing Potency and Spectrum

The evolution of quinolones into fluoroquinolones is a classic example of how strategic atom-level substitutions, guided by SAR, can dramatically improve drug performance. The foundational modification was the introduction of a fluorine atom at the C-6 position, which increased DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV binding affinity and cellular penetration [24].

Critical SAR Modifications in Fluoroquinolones:

- C-6 Fluorine: The defining change that gives the class its name; boosts potency and broadens the antimicrobial spectrum.

- C-7 Piperazinyl Group: This substitution significantly improves activity against Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- C-8 Halogen Substitution: Adding a chlorine or fluorine can improve activity against anaerobic bacteria but requires careful assessment as it can also increase phototoxicity risk.

- N-1 Cyclopropyl Group: This modification expands the spectrum of activity and improves the pharmacokinetic profile [24].

These deliberate, SAR-guided changes transformed nalidixic acid (a narrow-spectrum, low-potency quinolone) into broad-spectrum powerhouses like ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.

Essential Experimental Protocols for SAR Studies

A robust SAR workflow integrates multiple experimental techniques to elucidate the relationship between chemical structure and biological effect.

Protocol for In Vitro Cytotoxicity/Potency Assessment (MTT Assay)

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the effect of compound analogs on cell viability (anticancer agents) or bacterial growth (antibiotics).

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Plate target cells (e.g., cancer cell lines) or bacterial cultures in 96-well plates at a standardized density.

- Compound Treatment: Add serial dilutions of the test compounds to the wells. Include a negative control (vehicle only) and a positive control (known cytotoxic agent or antibiotic).

- Incubation: Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 48-72 hours for eukaryotic cells; 16-24 hours for bacteria).

- Viability Readout:

- For eukaryotic cells: Add MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) solution. Metabolically active cells reduce MTT to purple formazan crystals. Solubilize the crystals with DMSO and measure the absorbance at 570 nm.

- For bacteria: Measure optical density (OD) at 600 nm directly.

- Data Analysis: Calculate % cell viability or % growth inhibition. Determine the IC₅₀ (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) or MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) using non-linear regression analysis [23] [24].

Protocol for Structure-Based Drug Design (Molecular Docking)

Objective: To predict the binding orientation and affinity of a small molecule within a protein target's binding site, providing a structural basis for SAR.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target (e.g., from Protein Data Bank, PDB).

- Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands (unless critical).

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign protonation states at physiological pH.

- Minimize the energy of the protein structure to relieve steric clashes.

- Ligand Preparation:

- Draw or obtain the 3D structures of the compound analogs.

- Assign correct bond orders and generate probable tautomers and protonation states.

- Perform energy minimization to obtain a stable conformation.

- Docking Simulation:

- Define the binding site (often based on the location of a co-crystallized native ligand).

- Run the docking algorithm to generate multiple binding poses for each ligand.

- Score each pose using a scoring function to estimate binding affinity.

- Analysis:

- Analyze the top-scoring poses for key interactions: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking, and salt bridges.

- Correlate the computed binding energies with experimental IC₅₀/MIC values to validate the model and guide subsequent structural modifications [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SAR-Driven Drug Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function in SAR Studies | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Cell Line Panels | In vitro assessment of compound potency and selectivity. | NCI-60 human tumor cell lines for profiling anticancer agents [23]. |

| Enzyme-Based Assay Kits | Biochemical evaluation of target engagement and inhibition. | Kinase assay kits to determine IC₅₀ of tyrosine kinase inhibitors [22]. |

| Beta-Lactamase Enzymes | Screening for inhibition potency and spectrum. | Purified TEM-1, SHV-1, and CTX-M enzymes for testing novel β-lactamase inhibitors [24]. |

| Crystallography Reagents | Structure determination of protein-ligand complexes. | Crystallization screens (e.g., Hampton Research) to obtain crystals for X-ray diffraction, revealing binding modes. |

| Synthetic Chemistry Building Blocks | Rapid generation of analog libraries for SAR exploration. | Chiral amino acids, heterocyclic cores, and functionalized scaffolds for synthesizing derivatives (e.g., of ET-743 or quinolones) [23] [24]. |

| Analytical HPLC/MS Systems | Purity assessment and compound characterization. | Confirming the identity and >95% purity of all synthesized analogs before biological testing. |

The fundamental principle underlying all drug discovery efforts is the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), which posits that a compound's biological activity is determined by its molecular structure. For centuries, medicinal chemists have observed that structurally similar compounds often exhibit similar biological effects—a concept known as the principle of similarity [16]. Traditionally, SAR analysis was qualitative, relying on chemists' intuition and two-dimensional molecular graphs to guide compound optimization. This approach was largely subjective and context-dependent, with even experienced medicinal chemists rarely agreeing on what specific chemical characteristics rendered compounds 'drug-like' [25].

The limitations of qualitative SAR became increasingly apparent as compound activity data experienced exponential growth. The advent of large public domain repositories like PubChem and ChEMBL, which now contain millions of active molecules annotated with activities against numerous biological targets, rendered traditional case-by-case analysis impractical [25]. This data deluge, coupled with the inherent complexity of biological systems, necessitated a more systematic, quantitative approach to SAR exploration, leading to the development of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR).

The Historical Transition to Quantitative Approaches

The conceptual foundations of QSAR trace back approximately a century to observations by Meyer and Overton, who recognized that the narcotic properties of gases and organic solvents correlated with their solubility in olive oil [26]. A significant advancement came with the introduction of the Hammett equation in the 1930s, which quantified the effects of substituents on reaction rates in organic molecules through substituent constants (σ) [26].

QSAR formally emerged in the early 1960s through the independent work of Hansch and Fujita and Free and Wilson [16] [26]. Hansch and Fujita extended the Hammett equation by incorporating physicochemical parameters, creating the famous Hansch equation: log(1/C) = b₀ + b₁σ + b₂logP, where C represents molar concentration required for biological response, σ represents electronic substituent constant, and logP represents the lipophilicity parameter [26]. This approach marked a paradigm shift from qualitative observation to mathematical modeling of biological activity.

Concurrently, Free and Wilson developed an additive model that quantified the contribution of specific substituents at molecular positions to overall biological activity [26]. These pioneering works established QSAR as a distinct discipline, transforming drug discovery from an artisanal practice to a quantitative science.

The SAR Paradox and Its Implications

A crucial concept in understanding QSAR's necessity is the SAR paradox, which states that not all similar molecules have similar activities [27]. This paradox highlights the complexity of biological systems, where subtle structural changes can lead to dramatic activity differences. Such phenomena, known as activity cliffs, represent the extreme form of SAR discontinuity and are rich in information for medicinal chemists [25]. The existence of activity cliffs underscores the limitations of qualitative similarity assessments and reinforces the need for quantitative approaches that can detect and rationalize these critical transitions in chemical space.

Fundamental Components of QSAR Modeling

Robust QSAR modeling relies on three fundamental components: high-quality datasets, informative molecular descriptors, and appropriate mathematical algorithms. Each component has evolved significantly since QSAR's inception, dramatically enhancing the predictive power and applicability of modern QSAR models.

Datasets: The Foundation of QSAR Models

QSAR models are fundamentally data-driven, requiring carefully curated compound sets with reliable biological activity measurements. Dataset quality directly influences model performance and generalizability [16]. Key considerations include:

- Data Diversity: Training sets should encompass broad chemical space to ensure model applicability to novel compounds [16]

- Activity Reliability: Biological endpoints (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀) must be measured consistently using standardized protocols [28]

- Data Management: Modern Scientific Data Management Platforms (SDMPs) provide structured, searchable environments essential for AI-ready data [29]

The quality and representativeness of the molecular training set largely determine the predictive and generalization capabilities of the resulting QSAR model [16].

Molecular Descriptors: Quantifying Molecular Characteristics

Molecular descriptors are mathematical representations of molecular structures that convert chemical information into numerical values [16]. Descriptors have evolved from simple physicochemical parameters to complex multidimensional representations:

Table 1: Evolution of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|