Striking the Balance: Strategies for Novel yet Predictive Ligand-Based Drug Design

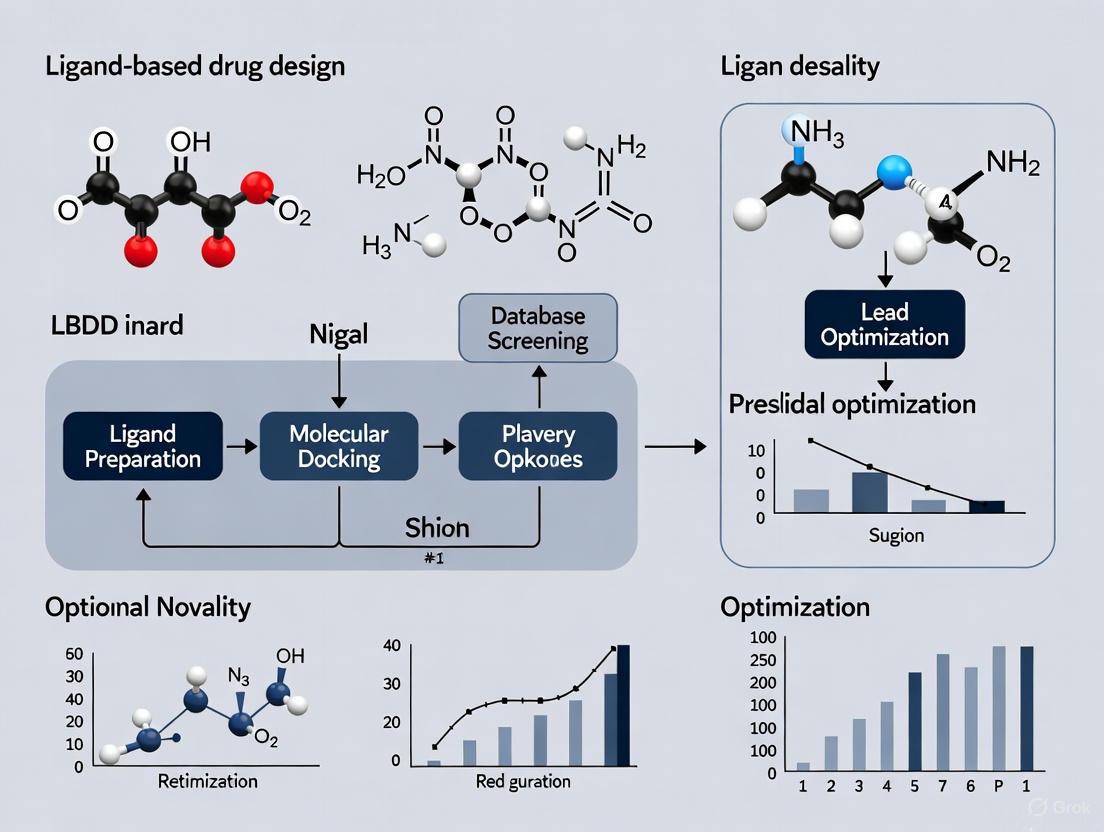

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, particularly when the 3D structure of a biological target is unknown.

Striking the Balance: Strategies for Novel yet Predictive Ligand-Based Drug Design

Abstract

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, particularly when the 3D structure of a biological target is unknown. This article addresses the central challenge in LBDD: navigating the trade-off between generating novel chemical entities and ensuring their predictable biological activity and physicochemical properties. We explore foundational concepts, advanced methodologies including AI and deep learning, and practical optimization strategies to enhance model credibility. By synthesizing insights from recent computational advances and real-world applications, this work provides a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design innovative, synthetically accessible, and highly predictive drug candidates, ultimately accelerating the delivery of new therapies.

The LBDD Foundation: Core Principles and the Novelty-Predictivity Paradox

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental premise of Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)? LBDD is a computational drug discovery approach used when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown. It deduces the essential features of a ligand responsible for its biological activity by analyzing the structural and physicochemical properties of known active molecules. This information is used to build models that predict new compounds with improved activity, affinity, or other desirable properties [1] [2].

Q2: When should I choose LBDD over Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)? LBDD is particularly valuable in the early stages of drug discovery for targets where the 3D protein structure is unavailable, such as many G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels [1]. It serves as a starting point when structural information is sparse, and its speed and scalability make it attractive for initial hit identification [2].

Q3: What are the main categories of LBDD methods? The three major categories are:

- Pharmacophore Modeling: Identifies the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition [1].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): Uses statistical and machine learning methods to relate molecular descriptors to biological activity [1] [2].

- Similarity Searching: Explores compounds with similar structural or physicochemical properties to known active molecules [1] [2].

Q4: How can I ensure my LBDD model generates novel yet predictable compounds? Balancing novelty and predictivity requires rigorous model validation and careful library design. Use external test sets for validation and apply metrics like the retrosynthetic accessibility score (RAScore) to assess synthesizability [3]. Modern approaches, like the DRAGONFLY framework, incorporate desired physicochemical properties during molecule generation to maintain a strong correlation between designed and actual properties, ensuring novelty does not come at the cost of synthetic feasibility or predictable activity [3].

Q5: What are common data challenges in LBDD? A primary challenge is the requirement for sufficient, high-quality data on known active compounds to build reliable models [1] [2]. The "minimum redundancy" filter can help prioritize diverse candidates [3]. For QSAR, a lack of large, homogeneous datasets can limit model accuracy and generalizability [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Predictive Accuracy of QSAR Model

- Symptoms: Poor performance on external test sets; inability to accurately rank new compounds.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Overfitting to the training data.

- Solution: Apply descriptor selection methodologies (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, stepwise regression) to remove highly correlated or redundant descriptors. Use validation techniques like y-randomization [1].

- Cause 2: Inadequate descriptors failing to capture the essential features for activity.

- Solution: Utilize a combination of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors to create a more comprehensive representation of the molecules. Consider exploring "fuzzy" pharmacophore and shape-based descriptors like CATS and USRCAT [3].

- Cause 3: Insufficient or non-homologous training data.

- Solution: Expand the training set with more known actives. If data is limited, consider using advanced 3D QSAR methods that can generalize well from smaller datasets [2].

- Cause 1: Overfitting to the training data.

Problem: Generated Molecules are Not Synthetically Accessible

- Symptoms: Top-ranking virtual hits are chemically complex or have low scores on synthesizability metrics (e.g., RAScore).

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: The generation algorithm prioritizes predicted activity over practical synthesis.

- Solution: Integrate synthesizability as a direct constraint during the de novo design process. Frameworks like DRAGONFLY explicitly consider synthesizability during molecule generation [3].

- Cause 2: The chemical space explored is too narrow or unrealistic.

- Solution: Leverage large, commercially available on-demand libraries (e.g., the REAL database) as a source of synthetically tractable compounds for virtual screening [4].

- Cause 1: The generation algorithm prioritizes predicted activity over practical synthesis.

Problem: Difficulty in Scaffold Hopping to Novel Chemotypes

- Symptoms: Similarity searches keep identifying compounds structurally very similar to the input, lacking chemical diversity.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Over-reliance on 2D structural fingerprints.

- Solution: Employ 3D similarity-based virtual screening that compares molecules based on shape, hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor geometries, and electrostatic properties, which can identify functionally similar molecules with different scaffolds [2].

- Cause 2: The pharmacophore model is too specific.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the pharmacophore hypothesis to ensure it captures only the essential features required for binding. A more minimalist model may enable the identification of a wider range of chemotypes [1].

- Cause 1: Over-reliance on 2D structural fingerprints.

Key Quantitative Metrics for LBDD Model Validation

The following table summarizes essential metrics for evaluating and validating LBDD models, particularly QSAR.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for LBDD Models

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out) | Assesses model robustness by iteratively leaving out parts of the training data and predicting them [1]. | A high cross-validated R² (Q²) suggests good internal predictive ability. |

| Y-randomization | The biological activity data (Y) is randomly shuffled, and new models are built [1]. | Valid models should perform significantly worse after randomization, confirming the model is not based on chance correlation. |

| External Test Set Validation | The model is used to predict the activity of compounds not included in the model development [1]. | The gold standard for evaluating real-world predictive performance. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | The average absolute difference between predicted and experimental activity values [3]. | Lower values indicate higher prediction accuracy. Useful for comparing model performance on the same dataset. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Measures the ability of a model to distinguish between active and inactive compounds [5]. | An AUC of 1 represents a perfect classifier; 0.5 is no better than random. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a 2D-QSAR Model This protocol outlines the steps for creating a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship model using 2D molecular descriptors [1].

- Data Curation: Compile a set of compounds with consistent and reliable biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ). The dataset should be as homogeneous as possible.

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate a wide range of 1D/2D molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices, molecular fingerprints) for all compounds.

- Descriptor Pre-processing and Selection: Normalize descriptor values. Remove highly correlated or constant descriptors. Use selection methods (e.g., Genetic Algorithm, stepwise regression) to identify the most relevant descriptors for the model.

- Model Building: Apply statistical or machine learning methods (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), Support Vector Machine (SVM)) to relate the selected descriptors to the biological activity.

- Model Validation: Rigorously validate the model using the metrics outlined in Table 1, with a strong emphasis on external validation.

- Model Application: Use the validated model to predict the activity of new, untested compounds from a virtual library to prioritize them for synthesis and experimental testing.

Protocol 2: Creating a Pharmacophore Model This protocol describes the generation of a pharmacophore hypothesis from a set of known active ligands [1].

- Ligand Selection and Conformational Analysis: Select a training set of molecules that are structurally diverse but share the same biological activity. For each ligand, generate a set of low-energy conformations that represent its accessible 3D space.

- Molecular Superimposition: Align the multiple conformations of the training set molecules to find the best common fit in 3D space.

- Feature Identification: Analyze the superimposed molecules to identify common steric and electronic features critical for activity. These features typically include hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups.

- Hypothesis Generation: The software algorithm generates one or more pharmacophore hypotheses that consist of the identified features and the spatial relationships between them.

- Hypothesis Validation: Test the generated pharmacophore model by using it to screen a database of molecules containing known actives and inactives. A good model should efficiently retrieve known actives (high enrichment).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for LBDD Research

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in LBDD |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [3] | Bioactivity Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Used to extract known active ligands and their binding affinities for model training. |

| ECFP4 Fingerprints [3] | Molecular Descriptor | A type of circular fingerprint that represents molecular structure. Used for similarity searching and as descriptors in QSAR modeling. |

| USRCAT & CATS Descriptors [3] | Pharmacophore/Shape Descriptor | "Fuzzy" pharmacophore and shape-based descriptors that help identify biologically relevant similarities between molecules beyond pure 2D structure. |

| MACCS Keys [1] | Molecular Descriptor | A 2D structural fingerprint representing the presence or absence of 166 predefined chemical substructures. Used for fast similarity searching. |

| REAL Database [4] | Virtual Compound Library | An ultra-large, commercially available on-demand library of billions of synthesizable compounds. Used for virtual screening to find novel hits. |

| Graph Transformer Neural Network (GTNN) [3] | Deep Learning Model | Used in advanced LBDD frameworks to process molecular graphs (2D for ligands, 3D for binding sites) and translate them into molecular structures. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

LBDD Core Workflow

QSAR Modeling Steps

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my de novo design model generating molecules that are not synthesizable?

This is a common issue where models prioritize predicted bioactivity over practical synthetic pathways. To address this, integrate a retrosynthetic accessibility score (RAScore) into your evaluation pipeline. The RAScore assesses the feasibility of synthesizing a given molecule and should be used as a filter before experimental consideration [6]. Furthermore, ensure your training data includes synthesizable molecules from credible chemical databases to guide the model toward more practical chemical space [6].

Q2: How can I quantitatively measure the novelty of a newly generated molecule?

Novelty can be measured using rule-based algorithms that capture both scaffold and structural novelty [6]. This involves comparing the core structure and overall chemical features of the new molecule against large databases of known compounds, such as ChEMBL or your in-house libraries. A quantitative score is generated based on the degree of structural dissimilarity, ensuring your designs are truly innovative and not minor modifications of existing compounds [6].

Q3: My generated molecules have good predicted activity but poor selectivity. What could be wrong?

Poor selectivity often arises from a model over-optimizing for a single target. Implement a multi-target profiling step in your workflow. Use quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models trained on a diverse set of targets to predict the bioactivity profile of generated molecules across multiple off-targets [6]. This helps identify and eliminate promiscuous binders early in the design process. The DRAGONFLY approach, which leverages a drug-target interactome, is specifically designed to incorporate such multi-target information [6].

Q4: What is the best way to extract molecular structures from published literature for my training set?

Optical chemical structure recognition (OCSR) tools have advanced significantly. For robust recognition of diverse molecular images found in literature, use modern deep learning models like MolNexTR [7] [8]. It employs a hybrid ConvNext-Transformer architecture to handle various drawing styles and can achieve high accuracy (81-97%) [7] [8]. For extracting entire chemical reactions from diagrams, the RxnCaption framework with its visual prompt (BIVP) strategy has shown state-of-the-art performance [9].

Q5: How can I expand the accessible chemical space for my virtual screening campaigns?

Utilize commercially available on-demand virtual libraries, such as the Enamine REAL database [4]. These libraries, which contain billions of make-on-demand compounds, dramatically expand the chemical space you can screen against a target. The REAL database grew from 170 million compounds in 2017 to over 6.7 billion in 2024, offering unparalleled diversity and novelty for hit discovery [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Novelty Scores in De Novo Designs

Problem: Your generated molecules are consistently flagged as having low novelty, indicating they are too similar to known compounds.

Solution Steps:

- Audit Training Data: Review the dataset used to train your generative model. If it's too narrow, the model will simply reproduce known chemical space. Incorporate more diverse data sources.

- Adjust Generation Constraints: Loosen any over-restrictive property constraints (e.g., molecular weight, logP) that might be forcing the model into a well-explored region of chemical space.

- Incorporate Novelty Metrics in Real-Time: Implement novelty assessment as a live criterion during the generation process, not just as a post-filter. This guides the model to explore newer territories [6].

- Explore Different Models: Consider using a model like DRAGONFLY, which is designed for "zero-shot" generation, constructing compound libraries tailored for structural novelty without requiring application-specific fine-tuning [6].

Issue: Poor Generalization of Molecular Image Recognition

Problem: Your OCSR model works well on clean images but fails on noisy or stylistically diverse images from real journals.

Solution Steps:

- Implement Advanced Data Augmentation: Use a framework that includes an image contamination module and rendering augmentations during training. This simulates the noise and varied drawing styles (e.g., different fonts, bond lines) found in real literature, significantly boosting model robustness [7] [8].

- Adopt a Hybrid Architecture: Choose a model that combines the strengths of different neural networks. For example, MolNexTR uses ConvNext for local feature extraction (atoms) and a Vision Transformer for global dependencies (long-range bonds), improving overall accuracy [7] [8].

- Integrate Chemical Rule-Based Post-Processing: Ensure the model uses symbolic chemistry principles to resolve ambiguities in chirality and abbreviated functional groups, which are common failure points in pure deep learning models [7] [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for De Novo Design Evaluation

This table summarizes the core quantitative metrics used to evaluate the success of a de novo drug design campaign, based on the DRAGONFLY framework [6].

| Metric | Description | Target Value | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Novelty | Quantitative uniqueness of a molecule's scaffold and structure. | High (algorithm-dependent score) | Rule-based algorithm comparing to known compound databases [6]. |

| Synthesizability (RAScore) | Feasibility of chemical synthesis. | > Threshold for synthesis | Retrosynthetic accessibility score (RAScore) [6]. |

| Predicted Bioactivity (pIC50) | Negative log of the predicted half-maximal inhibitory concentration. | > 6 (i.e., IC50 < 1 μM) | Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) QSAR models using ECFP4, CATS, and USRCAT descriptors [6]. |

| Selectivity Profile | Activity against a panel of related off-targets. | >10-100x selectivity for primary target | Multi-target KRR models predicting pIC50 for key off-targets [6]. |

Table 2: Molecular Image Recognition (OCSR) Model Performance

A comparison of model accuracy on various benchmarks, demonstrating the generalization capabilities of modern tools [7] [8].

| Model / Dataset | Indigo/ChemDraw | CLEF | JPO | USPTO | ACS Journal Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolNexTR | 97% | 92% | 89% | 85% | 81% |

| Previous Models (e.g., CNN/RNN) | 95% | 85% | 78% | 75% | 70% |

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Novelty and Synthesizability

Purpose: To objectively determine the novelty and synthetic feasibility of molecules generated by a de novo design model.

Procedure:

- Generate Molecular Library: Use your de novo design model (e.g., DRAGONFLY, fine-tuned CLM) to generate a virtual library of candidate molecules.

- Calculate Novelty Scores: For each generated molecule, compute a novelty score using a defined algorithm. This algorithm should quantify dissimilarity by comparing the molecule's scaffold and structural fingerprints against a large reference database like ChEMBL [6].

- Assess Synthesizability: Run each molecule through a RAScore calculator. Establish a threshold score above which molecules are considered synthetically tractable for your organization [6].

- Prioritize Candidates: Rank the generated molecules based on a weighted sum of their novelty, synthesizability, and predicted bioactivity scores for further investigation.

Protocol 2: Robust Molecular Structure Extraction from Literature Images

Purpose: To accurately convert molecular images in PDF articles or patents into machine-readable SMILES strings.

Procedure:

- Image Preprocessing: Isolate the molecular image from the document. Convert to a standard format (e.g., PNG) and resize if necessary.

- Model Selection and Inference: Use a pre-trained OCSR model like MolNexTR. Feed the image into the model, which will output a molecular graph prediction [7] [8].

- Post-Processing and Validation: The model's internal post-processing module will apply chemical rules to resolve chirality and abbreviations, converting the graph into a canonical SMILES string [7] [8].

- Curation: Manually, or via a second algorithm, check the output SMILES against the original image to catch any recognition errors, especially for complex or poorly drawn structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for balancing novelty and predictivity in LBDD.

| Item | Function in Research | Relevance to Novelty/Predictivity |

|---|---|---|

| On-Demand Virtual Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) | Provides access to billions of synthesizable compounds for virtual screening. | Directly expands the explorable chemical space, enabling the discovery of novel scaffolds [4]. |

| Drug-Target Interactome (e.g., in DRAGONFLY) | A graph network linking ligands to their macromolecular targets. | Provides the data foundation for multi-target profiling, improving the predictivity of selectivity [6]. |

| Chemical Language Models (CLMs) | Generates novel molecular structures represented as SMILES strings. | The core engine for de novo design; its training data dictates the novelty of its output [6]. |

| Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score (RAScore) | Computes the feasibility of synthesizing a given molecule. | A critical filter that ensures novel designs are practically realizable, bridging the gap between in silico and in vitro [6]. |

| Optical Chemical Structure Recognition (OCSR) e.g., MolNexTR | Converts images of molecules in documents into machine-readable formats. | Unlocks vast amounts of untapped structural data from literature, enriching training sets and inspiring novel designs [7] [8]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Balancing novelty and predictivity in LBDD.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow Integration

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, and similarity searching, and when should I prioritize one over the others?

A: These three methods form a complementary toolkit for ligand-based drug design (LBDD). Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models establish a mathematical relationship between numerically encoded molecular structures (descriptors) and a biological activity [10]. They are ideal for predicting potency (e.g., IC₅₀ values) and optimizing lead series. Pharmacophore modeling identifies the essential, abstract ensemble of steric and electronic features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, hydrophobic regions) necessary for a molecule to interact with its biological target [11]. It excels in scaffold hopping and identifying novel chemotypes that maintain key interactions. Similarity searching uses molecular "fingerprints" or descriptors to compute the similarity between a query molecule and compounds in a database [10]. It is best for finding close analogs and expanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) around a known hit. Prioritize QSAR for quantitative potency prediction, pharmacophore for discovering new scaffolds, and similarity searching for lead expansion and analog identification.

Q2: How can I assess the reliability of a QSAR model's prediction for a new compound?

A: A reliable prediction depends on the new compound falling within the model's Applicability Domain (AD), the region of chemical space defined by the training data. A model's predictive power is greatest for compounds that are structurally similar to those it was built upon [10]. Techniques to define the AD include calculating the Euclidean distance of the new compound from the training set molecules [12]. If a compound is too distant, its prediction should be treated with caution. Furthermore, always verify model performance using rigorous validation techniques like cross-validation and external test sets, rather than relying solely on fit to the training data [10].

Q3: My pharmacophore model is too rigid and retrieves very few hits, or it's too permissive and retrieves too many false positives. How can I optimize it?

A: This is a common challenge in balancing novelty and predictivity. To address it:

- Refine Feature Definitions: Not all features are equally important. Use your SAR knowledge to mark certain features as "essential" and others as "optional." Incorporate logic operators (AND, OR, NOT) to create more sophisticated queries [11].

- Adjust Tolerance Radii: The spheres representing pharmacophore features have adjustable radii. Systematically tightening (for specificity) or loosening (for sensitivity) these tolerances can significantly refine your results [11].

- Use Exclusion Volumes: If the protein structure is known, define exclusion volumes to represent regions occupied by the target, preventing hits that would sterically clash [11].

- Validate with Known Inactives: Test your pharmacophore model against a set of known inactive compounds. A good model should ideally not match these molecules, helping you tune out false positives [12].

Q4: Can these LBDD methods be integrated to create a more powerful virtual screening workflow?

A: Yes, and this is considered a best practice. A highly effective strategy is to combine methods in a sequential workflow to leverage their respective strengths. For example, you can first use a similarity search or a pharmacophore model to rapidly screen a massive compound library and create a focused subset of plausible hits. This subset can then be evaluated using a more computationally intensive QSAR model to prioritize compounds with the predicted highest potency [13]. This tiered approach efficiently balances broad exploration with precise prediction.

Troubleshooting Guides

QSAR Model Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Predictive Performance (Low Q²) | 1. Data quality issues (noise, outliers).2. Molecular descriptors do not capture relevant properties.3. Model overfitting. | 1. Curate data: Remove outliers and ensure activity data is consistent.2. Feature selection: Use algorithms (e.g., random forest) to identify the most relevant descriptors.3. Regularize: Apply regularization techniques (e.g., LASSO) to prevent overfitting. |

| Model Fails on Novel Chemotypes | The new compounds are outside the model's Applicability Domain (AD). | 1. Define AD: Use Euclidean distance or leverage PCA to visualize chemical space coverage [12].2. Similarity check: Calculate similarity to the nearest training set molecule. Avoid extrapolation. |

| Low Correlation Between Structure & Activity | The chosen molecular representation (e.g., 2D fingerprints) is insufficient for the complex activity. | 1. Use advanced descriptors: Shift to 3D descriptors or AI-learned representations [14].2. Try ensemble models: Combine predictions from multiple QSAR models. |

Pharmacophore Model Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Low Hit Rate in Virtual Screening | 1. Model is overly specific/rigid.2. Feature definitions are too strict.3. Database molecules lack conformational diversity. | 1. Relax constraints: Increase tolerance radii on non-essential features.2. Logic adjustment: Change some "AND" conditions to "OR".3. Confirm conformation generation: Ensure the screening protocol generates adequate, bio-relevant conformers [11]. |

| High False Positive Rate | 1. Model lacks specificity.2. Key exclusion volumes are missing. | 1. Add essential features: Introduce features based on SAR of inactive compounds.2. Define exclusion volumes: Use receptor structure to mark forbidden regions [11].3. Post-screen filtering: Use a second method (e.g., simple QSAR or docking) to filter the initial hits. |

| Failure to Identify Active Compounds | The model does not capture the true pharmacophore. | 1. Re-evaluate training set: Ensure it contains diverse, highly active molecules.2. Use structure-based design: If a protein structure is available, build a receptor-based pharmacophore to guide ligand-based model refinement [13]. |

Similarity Searching Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Misses Potent but Structurally Diverse Compounds (Low Scaffold Hopping) | The fingerprint (e.g., ECFP) is too sensitive to the molecular scaffold. | 1. Use a pharmacophore fingerprint: These encode spatial feature relationships and are less scaffold-dependent [11].2. Try a FEPOPS-like descriptor: Uses 3D pharmacophore points and is designed to identify scaffold hops [10]. |

| Retrieves Too Many Inactive Close Analogs | The fingerprint is biased towards overall structure, not key interaction features. | 1. Use a target-biased fingerprint: Methods like the TS-ensECBS model use machine learning to focus on features important for binding a specific target family [13].2. Apply a potency-scaled method: Techniques like POT-DMC weight fingerprint bits by the activity of the molecules that contain them [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key Computational Tools and Databases for LBDD

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevance to LBDD |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., alvaDesc) | Calculates thousands of numerical values representing molecular physical, chemical, and topological properties. | The fundamental input for building robust QSAR models, translating chemical structure into quantifiable data [14] [12]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, FCFP) | Encodes molecular structure into a bitstring based on the presence of specific substructures or topological patterns. | The core reagent for fast similarity searching and compound clustering. Also used as features in machine learning-based QSAR [11] [14]. |

| Toxicology Databases (e.g., Leadscope, EPA's ACToR) | Curated databases containing chemical structures and associated experimental toxicity endpoint data. | Critical for building predictive computational toxicology (ADMET) models to derisk candidates early and balance efficacy with safety [15] [16]. |

| LigandScout | Software for creating and visualizing both ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore models from data or protein-ligand complexes. | Enables the abstract representation of key molecular interactions, which is crucial for scaffold hopping and virtual screening [12]. |

| Pharmacophore Fingerprints | A type of fingerprint that represents molecules based on the spatial arrangement of their pharmacophoric features. | Enhances the ability of similarity searches to find functionally similar molecules with different scaffolds, directly aiding in exploring novelty [11]. |

| TS-ensECBS Model | A machine learning-based similarity method that measures the probability of compounds binding to identical or related targets based on evolutionary principles. | Moves beyond pure structural similarity to functional (binding) similarity, improving the success rate of virtual screening for novel targets [13]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

LBDD Methodology Integration Pathway

LBDD Methodology Integration Pathway

QSAR Model Development and Validation Workflow

QSAR Model Development and Validation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common points of failure in the drug development pipeline where novelty can be a liability? The drug development pipeline is characterized by high attrition rates, with a lack of clinical efficacy and safety concerns being the primary points of failure for novel compounds [17]. The following table summarizes the major causes of failure:

| Cause of Failure | Approximate Percentage of Failures Attributed to This Cause |

|---|---|

| Lack of Efficacy | 40-50% |

| Unforeseen Human Toxicity / Safety | ~30% |

| Inadequate Drug-like Properties | 10-15% |

| Commercial or Strategic Factors | ~10% |

Novel compounds often fail in Phase II or III trials when promising preclinical data does not translate to efficacy in patients, or when safety problems emerge in larger, more diverse human populations [17].

Q2: How can I operationally distinguish between the novelty of a compound and its associated reward uncertainty in an LBDD campaign? In experimental terms, you can decouple these factors by designing studies that separate sensory novelty (a new molecular structure you have not worked with before) from reward uncertainty (the unknown probability of that molecule being effective and safe) [18]. A practical methodology is to:

- Re-use novel compounds in new, unrelated assays. Even after a compound's properties are known in one context (e.g., its potency against a primary target), its performance in a new therapeutic context or assay system remains highly uncertain. This creates a scenario with low sensory novelty but high reward uncertainty [18].

- Explicitly frame and document hypotheses. For each novel compound, clearly state the assumptions about its efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety. This makes the specific areas of uncertainty explicit and testable.

Q3: Our high-throughput screening has identified a novel lead compound, but its oral bioavailability is poor. What are the key formulation challenges we should anticipate? A novel compound with poor bioavailability presents a significant challenge to predictive accuracy, as in vivo results will likely deviate from in vitro predictions. Key challenges include [19]:

- Stability Failures: Stability problems with the drug substance or formulation, if not detected early during formulation development, can lead to costly stability failures during clinical phases. Resolving these can take months, with over a year required to generate sufficient stability data [19].

- Timeline and Budget Risks: Compressed timelines in early development often force formulators to use suboptimal, simple formulations for initial studies, which can fail to adequately test the compound's true potential [19].

Q4: What experimental strategies can mitigate the risk of novelty-induced failure in preclinical development? To reduce these risks, adopt an integrated, non-linear development strategy [19]:

- Engage a Cross-Functional Team Early: Involve CMC (Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls), toxicology, and regulatory experts during the overall strategy and planning phase, not after. This ensures valuable information is incorporated early [19].

- Initiate CMC Work Early: Start formulation development and analytical method development as early as possible to de-risk budget and timeline issues associated with bioavailability and stability [19].

- Select Experienced Partners: Choose a board-certified toxicologist committed to every step of the IND-enabling animal studies and thoroughly inspect the CRO performing these studies [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Attrition Rate in Late-Stage Discovery Your novel compounds show promising in vitro activity but consistently fail during in vivo efficacy or safety studies.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution and Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Pharmacokinetic (PK) Properties | Conduct intensive PK profiling in relevant animal models. Measure C~max~, T~max~, AUC, half-life (t~1/2~), and volume of distribution (V~d~). | Utilize prodrug strategies or advanced formulation approaches (e.g., nanoformulations, lipid-based systems) to improve solubility and permeability. |

| Poor Target Engagement | Develop a target engagement assay or use Pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers to confirm the compound is reaching and modulating the intended target in vivo. | Re-optimize the lead series for improved potency and binding kinetics, or investigate alternative drug delivery routes to enhance local concentration. |

| Off-Target Toxicity | Perform panel-based secondary pharmacology screening against a range of common off-targets (e.g., GPCRs, ion channels). Follow up with transcriptomic or proteomic profiling. | Use structural biology and medicinal chemistry to refine selectivity. If the off-target activity is linked to the core scaffold, a scaffold hop may be necessary. |

Problem: Irreproducible Results in a Key Biological Assay An assay critical for prioritizing novel compounds is producing high variance, making it impossible to distinguish promising leads from poor ones.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution and Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Technique Variability | Have multiple scientists independently repeat the assay using the same materials and protocol. Compare the inter-operator variability. | Implement rigorous, hands-on training for all team members. Create a detailed, step-by-step visual protocol and use calibrated pipettes. For cell-based assays, pay close attention to consistent aspiration techniques during wash steps to avoid losing cells [20]. |

| Unstable Reagents or Cells | Test the age and lot-to-lot variability of key reagents. For cell-based assays, monitor passage number, cell viability, and mycoplasma contamination. | Establish a strict cell culture and reagent QC system. Use low-passage cell banks and validate new reagent lots against the old ones before full implementation. |

| Poorly Understood Assay Interference | Spike the assay with known controls, including a non-responding negative control compound and a well-characterized positive control. | Systematically deconstruct the assay protocol to identify which component or step is introducing noise. Introduce additional control points to validate each stage of the assay [20]. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Overview of Drug Development Attrition

The following table summarizes the typical attrition rates from initial discovery to market approval, highlighting the high risk associated with novel drug candidates [17].

| Pipeline Stage | Typical Number of Compounds | Attrition Rate | Primary Reason for Failure in Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Screening | 5,000 - 10,000 | N/A | Does not meet basic activity criteria |

| Preclinical Testing | ~250 | ~95% | Poor efficacy in disease models, unacceptable toxicity in animals, poor pharmacokinetics |

| Clinical Phase I | 5 - 10 | ~30% | Human safety/tolerability, pharmacokinetics |

| Clinical Phase II | ~5 | ~60% | Lack of efficacy in targeted patient population, safety |

| Clinical Phase III | ~2 | ~30% | Failure to confirm efficacy in larger trials, safety in broader population |

| Regulatory Approval | ~1 | ~10% | Regulatory review, benefit-risk assessment |

Detailed Protocol: Target Shuffling to Validate Data Mining Results

This protocol is used to test if patterns discovered in high-dimensional data (e.g., from 'omics' screens) are statistically significant or likely to be false positives arising by chance [21].

- Objective: To evaluate the statistical significance of a discovered pattern or model by comparing it to results from datasets where the relationship between input and output has been randomly broken.

- Background: When searching through many variables, it is easy to find seemingly strong but ultimately spurious correlations (e.g., "the 'Redskins Rule'"). Target shuffling is a computer-intensive method to establish a baseline for random chance [21].

- Materials:

- Your dataset with input variables (e.g., compound descriptors) and a target output variable (e.g., efficacy score).

- Data mining or machine learning software.

- Methodology:

- Build Initial Model: Using your original dataset, build your predictive model and record the performance metric of interest (e.g., AUC, correlation coefficient).

- Shuffle the Target: Randomly shuffle the values of the target output variable across the input data. This breaks any true relationship between them while preserving the individual variable distributions.

- Search on Shuffled Data: Run the same data mining algorithm on this shuffled dataset and save the "most interesting" result (the best performance metric achieved by chance).

- Repeat: Repeat steps 2 and 3 many times (e.g., 1,000 times) to build a distribution of bogus "most interesting results."

- Evaluate Significance: Compare your initial model's performance from Step 1 against the distribution of random results from Step 4. The proportion of random results that performed as well or better than your model is your empirical p-value [21].

- Interpretation: If your initial result is stronger than the best result from all your shuffled iterations, you can be confident the finding is not due to chance. If it falls within the distribution, the significance level (p-value) is the percentage of random results that matched or exceeded it [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Context of Novelty vs. Predictivity |

|---|---|

| IND-Enabling Toxicology Studies | Required animal studies to evaluate the safety of a novel compound before human trials; a major hurdle where lack of predictive accuracy can sink a program [19]. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assays | Allows for the rapid testing of thousands of novel compounds against a biological target; the design and quality of these assays directly impact the predictive accuracy of the results. |

| Predictive PK/PD Modeling Software | Uses computational models to simulate a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (PK) and its pharmacological effect (PD); crucial for prioritizing novel compounds with a higher chance of in vivo success. |

| Cross-Functional Team (CMC, Toxicology, Clinical) | An integrated team of experts is vital to run successful drug development programs, as a siloed approach is a common source of missteps and communication failure that exacerbates the risks of novelty [19]. |

| Target Shuffling Algorithm | A statistical method used to validate discoveries in complex datasets by testing them against randomly permuted data, helping to ensure that a "novel" finding is not a false positive [21]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

In ligand-based drug design (LBDD), where the 3D structure of the biological target is often unknown, researchers face a fundamental challenge: balancing the need for novel chemical entities with the requirement for predictable activity and safety profiles [1]. The choice of molecular representation directly impacts this balance. Simpler 1D representations enable rapid screening but may lack the structural fidelity to accurately predict complex biointeractions. Conversely, sophisticated 3D representations offer detailed insights but demand significant computational resources and high-quality input data [22]. This technical support center addresses the specific, practical issues researchers encounter when working across this representation spectrum, providing troubleshooting guides to navigate the trade-offs between novelty and predictivity in LBDD campaigns.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: When should I use 1D/2D representations over 3D representations in my LBDD workflow?

Answer: The choice depends on your project's stage and the biological information available. Use 1D/2D representations for high-throughput tasks in the early discovery phase. Transition to 3D representations when you require detailed insights into binding interactions or stereochemistry.

- Use 1D SMILES or 2D Graphs when:

- Use 3D Conformations when:

- Optimizing lead compounds for specific binding interactions and stereochemistry [24].

- You have reliable structural information about the target, either from experimental methods or AI-based prediction tools like AlphaFold [24] [22].

- Your generated molecules exhibit good predicted affinity but poor selectivity or specificity, indicating potential off-target binding [22].

Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Generated molecules using 2D QSAR are chemically valid but biologically inactive.

- Solution: The model may have learned incorrect correlations from biased 2D descriptors. Re-train your model using a 3D-aware representation or incorporate protein structural information if available to capture essential spatial relationships [22].

- Problem: The 3D generation process produces molecules with distorted, energetically unstable rings.

- Solution: This is a known issue when bonds are assigned post-hoc based on atom coordinates. Implement a model that concurrently generates both atoms and bonds (e.g., via bond diffusion) to ensure structural feasibility [24].

FAQ 2: How can I ensure my AI-generated molecules are both novel and have predictable properties?

Answer: Achieving this balance requires careful design of your generative model's training and output.

- To Enhance Novelty: Train your generative models on large, diverse, multi-modal datasets (like M3-20M) that cover a broad chemical space, preventing the model from simply reproducing known compounds [23].

- To Improve Predictivity: Explicitly guide the generation process using desired molecular properties.

- Technical Protocol: Integrate property guidance during the AI's sampling process. This involves incorporating penalties or rewards for properties like drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and binding affinity (Vina Score) into the loss function [24]. For example, the DiffGui model uses this to generate molecules with high binding affinity and desirable properties [24].

- Technical Protocol: Use scaffold-based novelty metrics to quantitatively assess the uniqueness of generated molecules, ensuring they are not minor variations of existing templates [6].

Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Generated molecules are novel but have poor predicted binding affinity or undesirable properties (e.g., low QED, high LogP).

- Problem: Molecules have excellent predicted properties but are chemically similar to known inhibitors, limiting intellectual property potential.

- Solution: Your training data may be too narrow. Incorporate a "novelty penalty" or use a generative model like DRAGONFLY that is designed for zero-shot construction of novel compound libraries, reducing reliance on application-specific fine-tuning [6].

FAQ 3: My 3D-generated molecule looks correct, but docking scores are poor. What could be wrong?

Answer: This discrepancy often arises from inconsistencies between the generation and validation steps.

- Check the Generation Method: Older generative models produced atoms first and inferred bonds later, where minor coordinate deviations led to incorrect bond types and distorted geometries [24]. Ensure your 3D generator explicitly models bond types and their dependencies on atom positions.

- Validate Structural Feasibility: Before docking, analyze the generated ligand's geometry.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Calculate the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the generated conformation and a force-field optimized version of the same molecule. A high RMSD suggests an unstable conformation [24].

- Check for unrealistic dihedral angles, van der Waals clashes, or strained ring systems that would be energetically unfavorable in a real binding event.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Consider Protein Flexibility: Your docking program might use a rigid protein structure. The generated molecule could represent a conformation that requires minor side-chain adjustments in the protein pocket [22]. Consider using flexible docking or ensemble docking methods if available.

FAQ 4: How do I effectively select and color specific structural elements in a 3D viewer for analysis?

Answer: Effective selection and coloring are critical for analyzing protein-ligand interactions. The following protocols are based on Mol* viewer functionality [25].

- Selection Protocol:

- Enter Selection Mode.

- Set the Picking Level (e.g., residue, atom, chain).

- Make selections by:

- Clicking directly on the structure in the 3D canvas.

- Using the Sequence Panel to click on residue names.

- Applying Set Operations (e.g., "Amino Acid > Histidine" to select all HIS residues).

- Use the operation buttons (Union, Subtract, Intersect) to refine complex selections [25].

- Coloring Protocol:

- Find the component (e.g., Polymer, Ligand) in the Components Panel.

- Click the Options button next to it.

- Navigate to Set Coloring and choose a scheme:

- By Chain ID: To distinguish different protein chains.

- By Residue Property > Hydrophobicity: To visualize polar (red/orange) and hydrophobic (green) patches.

- By Residue Property > Secondary Structure: To color alpha-helices magenta and beta-sheets gold [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Representations in Drug Design

| Representation | Data Format | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations for LBDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D (SMILES) | Text String (e.g., "CCN") | High-throughput screening, Chemical language models (CLMs) | Fast processing, Simple storage, Easy for AI to learn [23] | Lacks stereochemistry; poor at capturing 3D shape and interactions [23] |

| 2D (Graph) | Nodes (atoms) & Edges (bonds) | QSAR, Similarity searching, Pharmacophore modeling [1] | Encodes connectivity and functional groups; good for scaffold hopping | Cannot represent 3D conformation, flexible rings, or binding poses |

| 3D (Conformation) | Atomic Cartesian Coordinates | Structure-based design, Binding pose prediction, De novo generation [24] [22] | Directly models steric fit and molecular interactions with target [22] | Computationally expensive; can generate unrealistic structures [24]; requires a known or predicted target structure |

Table 2: Evaluation Metrics for Generated Molecules in LBDD

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description | Target Value (Ideal Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Validity | RDKit Validity | Percentage of generated molecules that are chemically plausible. | > 95% [24] |

| Molecular Stability | Percentage of molecules where all atoms have the correct valency. | > 90% [24] | |

| Novelty | Scaffold Novelty | Measures the uniqueness of the molecular core structure compared to a reference set. | Project-dependent (typically > 50%) [6] |

| Drug-Likeness | QED (Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness) | Measures overall drug-likeness based on molecular properties. | 0.5 - 1.0 (Higher is better) [24] |

| SA (Synthetic Accessibility) | Estimates how easy a molecule is to synthesize. | 1 - 10 (Lower is better, < 5 is desirable) [24] | |

| Bioactivity Prediction | Vina Score (Estimated) | A physics-based score predicting binding affinity to the target. | Lower (more negative) indicates stronger binding [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Modal Dataset | Provides comprehensive data (1D, 2D, 3D, text) for training and fine-tuning robust AI models that understand multiple facets of chemistry. | M3-20M Dataset [23] |

| 3D Generative Model | Creates novel 3D molecular structures conditioned on a target protein pocket, crucial for SBDD and detailed LBDD. | DiffGui [24] |

| Interactome-Based Model | Enables "zero-shot" generation of bioactive molecules without task-specific fine-tuning, balancing novelty and predictivity by leveraging drug-target interaction networks. | DRAGONFLY [6] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | A software toolkit for manipulating molecules, calculating descriptors, validating structures, and converting between representations. | RDKit [23] |

| 3D Structure Viewer | Interactive visualization of protein-ligand complexes, essential for analyzing generation results and binding interactions. | Mol* [25] |

Experimental Workflows & Logical Diagrams

Diagram: Multi-Modal Molecular Generation Workflow

Diagram: The LBDD Representation Selection Logic

Advanced LBDD Methodologies: AI, Deep Learning, and Chemical Space Navigation

FAQs: Core Concepts and Model Selection

Q1: What are the key differences between Chemical Language Models (CLMs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for LBDD, and how do they impact the novelty of generated molecules?

Chemical Language Models (CLMs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent two different approaches to molecular representation learning. CLMs typically process molecules as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings, using architectures like Transformers or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to learn from sequence data [6] [26]. In contrast, GNNs represent molecules as 2D or 3D graphs, where nodes represent atoms and edges represent chemical bonds, allowing them to natively capture molecular topology and connectivity [27].

The choice of model significantly impacts the structural novelty of generated compounds. Studies evaluating AI-designed active compounds found that structure-based approaches, which often leverage GNNs, tend to produce molecules with higher structural novelty compared to traditional ligand-based models [28]. Specifically, ligand-based models often yield molecules with relatively low novelty (Tcmax > 0.4 in 58.1% of cases), whereas structure-based approaches perform better (17.9% with Tcmax > 0.4) [28]. This is because GNNs can better capture fundamental structural relationships, enabling more effective exploration of novel chemical spaces beyond the training data distribution.

Q2: How can I balance the trade-off between structural novelty and predicted bioactivity when generating compounds with deep learning models?

Balancing novelty and predictivity requires strategic approaches throughout the model pipeline. First, consider using interactome-based deep learning frameworks like DRAGONFLY, which leverage both ligand and target information across multiple nodes without requiring application-specific fine-tuning [6]. This approach enables "zero-shot" construction of compound libraries with tailored bioactivity and structural novelty.

Second, implement systematic novelty assessment that goes beyond simple fingerprint-based similarity metrics. The Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) alone may fail to detect scaffold-level similarities [28]. Supplement quantitative metrics with manual verification to avoid structural homogenization. Recommended strategies include using diverse training datasets, scaffold-hopping aware similarity metrics, and careful consideration of similarity filters in AI-driven drug discovery workflows [28].

Third, optimize your training data quality. The balance between active ("Yang") and inactive ("Yin") compounds in training data significantly impacts model performance [29]. Prioritize data quality despite size, as imbalanced datasets can bias models toward generating compounds similar to existing actives with limited novelty.

Q3: What are the most common reasons for the failure of AI-generated compounds to show activity in experimental validation, and how can this be mitigated?

Failures in experimental validation often stem from several technical issues. Over-reliance on ligand-based similarity without proper structural constraints can generate molecules that are chemically similar to active compounds but lack critical binding features. Additionally, inadequate representation of 3D molecular properties in 2D-based models can lead to generated compounds with poor binding complementarity [27] [26].

Mitigation strategies include:

- Incorporating 3D structural information when available, either through 3D-GNNs or by using methods like MLM-FG that enhance SMILES-based models to better capture structural features [26]

- Implementing robust validation protocols including synthesizability assessment using metrics like RAScore, and multi-descriptor QSAR predictions [6]

- Utilizing structure-based generation methods when possible, as they demonstrate better performance in producing novel bioactive compounds compared to purely ligand-based approaches [28]

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Structural Novelty in Generated Compounds

Problem: AI models consistently generate compounds with high structural similarity to training data molecules (Tcmax > 0.4), indicating limited exploration of novel chemical space.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Step 1: Analyze your training dataset diversity. Calculate similarity metrics within the training set itself. If internal similarity is high, expand your data sources to include more diverse chemical scaffolds [29].

- Step 2: Implement alternative molecular representations. If using SMILES-based CLMs, try switching to graph-based representations (GNNs) which may better capture structural relationships enabling more effective scaffold hopping [27].

- Step 3: Adjust generation constraints. If using reinforcement learning, modify reward functions to explicitly penalize high similarity to known actives while maintaining predicted bioactivity [29].

- Step 4: Employ specialized novelty-enhancing tools such as Scaffold Hopper, which maintains core features of query molecules while proposing novel chemical scaffolds [30].

Table: Troubleshooting Poor Structural Novelty

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Limited training data diversity | Calculate intra-dataset similarity metrics | Expand data sources; include diverse chemotypes [29] |

| Over-optimized similarity constraints | Review similarity threshold settings | Implement scaffold-aware similarity metrics [28] |

| Inadequate molecular representation | Compare outputs across different model types | Switch from CLMs to GNNs or hybrid approaches [27] |

Discrepancy Between Predicted and Experimental Bioactivity

Problem: Compounds with favorable predicted bioactivity (pIC50) consistently show poor experimental results, indicating a predictivity gap.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Step 1: Validate the predictive models. Ensure QSAR models are trained with sufficient, high-quality data. For most targets, mean absolute errors (MAE) for predicted pIC50 values should be ≤ 0.6 [6]. If using kernel ridge regression (KRR) models with ECFP4, CATS, or USRCAT descriptors, verify training set size exceeds ~100 molecules for optimal performance [6].

- Step 2: Assess data quality and balance. Review the ratio of active to inactive compounds in training data. Significant imbalance can bias predictions [29]. Curate datasets with balanced "Yin-Yang" bioactivity data where possible.

- Step 3: Evaluate physicochemical properties. Ensure generated compounds maintain drug-like properties including appropriate molecular weight, lipophilicity, and polar surface area. DRAGONFLY has demonstrated strong correlation (r ≥ 0.95) between desired and actual properties for these parameters [6].

- Step 4: Implement multi-descriptor consensus prediction. Relying on a single molecular representation (e.g., fingerprints only) may miss critical features. Combine structural (ECFP), pharmacophore (CATS), and shape-based (USRCAT) descriptors for more robust bioactivity predictions [6].

Inefficient Exploration of Chemical Space

Problem: The AI model gets stuck in limited regions of chemical space, generating similar compounds with minimal diversity despite attempts to adjust parameters.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Step 1: Implement chemical space navigation platforms like infiniSee, which enable efficient exploration of vast combinatorial molecular spaces containing trillions of compounds [30]. These tools can identify diverse yet synthetically accessible regions.

- Step 2: Utilize multiple generation strategies concurrently. Combine unconstrained generation (for diversity) with constrained generation targeting specific substructures (for maintainance of key features) and ligand-protein-based generation (for bioactivity) [27].

- Step 3: Apply sampling temperature adjustments in generative models. Increasing sampling temperature in probabilistic models can promote diversity, though may require additional filtering for desired properties.

- Step 4: Integrate fragment-based approaches. Tools like Motif Matcher can identify compounds containing specific molecular motifs or substructures, enabling focused exploration of chemical spaces based on functional groups while maintaining diversity at the scaffold level [30].

Table: Chemical Space Exploration Tools

| Tool Name | Approach | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| infiniSee | Chemical Space Navigation | Screens trillion-sized molecule collections for similar compounds [30] | Initial diverse lead identification |

| Scaffold Hopper | Scaffold Switching | Discovers new chemical scaffolds maintaining core query features [30] | Scaffold diversification in lead optimization |

| Motif Matcher | Substructure Search | Identifies compounds containing specific molecular motifs [30] | Structure-activity relationship exploration |

Synthesizability Challenges with AI-Designed Molecules

Problem: Generated compounds show promising predicted bioactivity but present significant synthetic challenges, making them impractical for experimental validation.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Step 1: Integrate synthesizability assessment early in the generation pipeline. Use retrosynthetic accessibility score (RAScore) to evaluate synthetic feasibility during compound generation rather than as a post-filter [6].

- Step 2: Leverage fragment-based growth strategies. Instead of generating complete molecules de novo, consider systems that assemble compounds from synthetically accessible fragments or building blocks.

- Step 3: Utilize command-line versions of chemical space navigation tools for integration into automated workflows, enabling real-time synthesizability assessment during high-throughput generation [30].

- Step 4: Implement property-based constraints during generation. DRAGONFLY demonstrates strong capability (r ≥ 0.95) to control key physicochemical properties like molecular weight, rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, polar surface area, and lipophilicity during generation, which can indirectly improve synthesizability [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for AI-Driven LBDD

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in LBDD | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Generation Platforms | DRAGONFLY [6] | De novo molecule generation using interactome-based deep learning | Combines GTNN and LSTM; supports both ligand- and structure-based design |

| REINVENT 2.0 [29] | Ligand-based de novo design using RNN with reinforcement learning | Open-source; transfer learning capability for property optimization | |

| Chemical Space Navigation | infiniSee [30] | Exploration of vast combinatorial molecular spaces | Screens trillion-sized molecule collections; multiple search modes |

| Scaffold Hopper [30] | Scaffold diversification while maintaining core features | Identifies novel scaffolds with similar properties to query compounds | |

| Molecular Representation | ECFP4 [6] | Structural molecular fingerprints for similarity assessment | Circular fingerprints capturing atomic environments |

| CATS [6] | Pharmacophore-based descriptor for similarity searching | "Fuzzy" descriptor capturing pharmacophore points | |

| USRCAT [6] | Ultrafast shape recognition descriptors | Rapid 3D molecular shape and pharmacophore comparison | |

| Bioactivity Prediction | KRR Models [6] | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship modeling | Kernel Ridge Regression with multiple descriptors for pIC50 prediction |

| Synthesizability Assessment | RAScore [6] | Retrosynthetic accessibility evaluation | Machine learning-based score predicting synthetic feasibility |

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) traditionally relies on known active compounds to guide the discovery of new molecules with similar properties. While effective, this approach can limit chemical novelty. Zero-shot generative artificial intelligence (AI) presents a paradigm shift, enabling the de novo design of bioactive molecules for targets with no known ligands, thereby offering a path to unprecedented chemical space.

The core challenge lies in balancing this novelty with predictivity. A model must generate structures that are not only novel but also adhere to the complex, often implicit, rules of bioactivity and synthesizability. This case study explores this balance through the lens of real-world models, providing a technical troubleshooting guide for researchers implementing these cutting-edge technologies.

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "zero-shot" mean in the context of molecule generation, and how does it differ from traditional methods?

A: Zero-shot learning refers to a model's ability to generate predictions for classes or tasks it never encountered during training. In molecule design, a zero-shot model can propose ligands for a novel protein target without having been trained on any known binders for that specific target [31] [32]. This contrasts with traditional generative models, which are limited to the chemical space and target classes represented in their training data.

Q2: My model generates molecules with good predicted affinity but poor synthetic feasibility. How can I address this?

A: This is a common bottleneck. Solutions include:

- Adopt a "chemistry-first" approach: Use platforms like Makya that build molecules via sequences of feasible reactions on real starting materials, guaranteeing synthetic accessibility from the outset [33].

- Integrate reaction-based generation: Instead of generating molecular strings (e.g., SMILES), use models that perform iterative virtual chemistry, selecting building blocks and applying known reactions [33].

- Apply post-generation filtering: Use synthetic accessibility score (SAS) filters, but note this is a less optimal solution as it may discard molecules after significant computational resources have been spent on their design.

Q3: What is "mode collapse" in generative models, and how can it be mitigated in a zero-shot setting?

A: Mode collapse occurs when a generator produces a limited diversity of outputs, failing to explore the full chemical space. In zero-shot learning, a key reason can be applying an identical adaptation direction for all source-domain images [34].

- Mitigation Strategy: Implement Image-specific Prompt Learning (IPL), which learns specific prompt vectors for each source-domain image. This produces a more precise adaptation direction for every cross-domain image pair, greatly enhancing the diversity of synthesized images and alleviating mode collapse [34].

Q4: How can I guide generation toward a specific 3D molecular shape to mimic a known pharmacophore?

A: Utilize shape-conditioned generative models.

- Method: Models like DiffSMol encapsulate the geometric details of a reference ligand's shape into a pre-trained, expressive shape embedding [35]. A diffusion model then generates new molecules in 3D space under the guidance of this shape embedding.

- Protocol: The process involves calculating a shape similarity kernel and using it to iteratively guide the denoising process of a diffusion model, ensuring the final 3D structure resembles the target shape [36] [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Generated molecules have unrealistic 3D geometries or incorrect bond lengths.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| distorted ring systems | Poor handling of molecular symmetry and geometry by the model. | Use an equivariant diffusion model [35] or an equivariant graph neural network that respects rotational and translational symmetries, much like a physical force field [36]. |

| Long bonds/short bonds | The score function (sr(x,t)) is not accurately capturing quantum-mechanical forces at the final stages of generation [36]. | Analyze the behavior of the learnt score; it should resemble a quantum-mechanical force at the end of the generation process. Ensure training incorporates relevant physical constraints. |

Problem: Model fails to generate molecules with high binding affinity for an unseen target.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low docking scores | The model lacks understanding of the interaction relationship between the target and ligand. | Integrate a contrastive learning mechanism and a cross-attention layer during pre-training. This helps the model align protein and ligand features and understand their potential interactions, even for unseen targets [32]. |

| Ignoring key residues | Inability to focus on critical binding site residues. | Implement an attention mechanism that can be visualized. For instance, ZeroGEN uses cross-attention, and visualizing its attention matrix can confirm if the model focuses on key protein residues during generation [32]. |

Problem: Language Model (LLM) for molecule generation produces invalid SMILES strings.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid syntax | The model's tokenization or training data may not adequately capture SMILES grammar. | Use knowledge-augmented prompting with task-specific instructions and demonstrations to guide the LLM, addressing the distributional shift that leads to invalid outputs [37]. |

| Chemically impossible atoms/valences | The model hallucinates structures outside of chemical rules. | Fine-tune the LLM on a large, curated corpus of SMILES strings. Employ reinforcement learning with chemical rule-based rewards to penalize invalid structures. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: Zero-Shot Generation with a Protein Sequence

This protocol is based on the ZeroGEN framework for generating ligands using only a novel protein's amino acid sequence [32].

1. Model Architecture and Pre-training:

- Protein & Ligand Encoders: Use Transformer-based encoders (e.g., BERT-style) to convert the protein sequence and ligand SMILES into separate sequences of embeddings. A [CLS] token provides an overall representation for each [32].

- Protein-Ligand Contrastive Learning (PLCL): Train the model to minimize the distance between embeddings of known binding pairs (positive pairs) and maximize the distance for non-binding pairs (negative pairs). The loss function is:

L_PLCL = - log [ exp(sim(z_p, z_l)/τ) / Σ_{k=1}^N exp(sim(z_p, z_l_k)/τ) ]wheresimis a similarity function andτis a temperature parameter [32].

- Protein-Ligand Interaction Prediction (PLIP): Use a cross-attention mechanism to allow the protein and ligand features to interact deeply, enhancing the model's ability to discern complex relationships.

- Protein-Grounded Ligand Decoder: A Transformer-based decoder that generates ligand tokens auto-regressively, conditioned on the protein's encoded representation.

2. Zero-Shot Generation and Self-Distillation:

- Initial Generation: Input the novel protein sequence into the pre-trained ZeroGEN model to generate an initial set of candidate ligands.

- Self-Distillation for Data Augmentation: a. Use the pre-trained relationship extraction component (PLCL/PLIP) to assess the relevance of the generated molecules to the target protein. b. Filter out low-scoring, irrelevant molecules. c. The remaining high-affinity molecules form a "pseudo" dataset for the novel target. d. Use this pseudo-dataset to fine-tune the generation module, helping it learn which ligands match the unseen target and refining its output [32].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Benchmarking success rates of shape-conditioned molecule generation (SMG) methods. Success rate is defined as the percentage of generated molecules that closely resemble the ligand shape and have novel graph structures. [35]

| Model / Method | Approach | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|

| DiffSMol (with shape guidance) | Diffusion Model + Shape Embedding | 61.4% |

| DiffSMol (base) | Diffusion Model + Shape Embedding | 28.4% |

| SQUID | Fragment-based VAE | 11.2% |

| Shape2Mol | Fragment-based Encoder-Decoder | < 11.2% |

Table 2: Performance of pocket-conditioned generation (PMG) and zero-shot models in generating high-affinity binders. [32] [35]

| Model / Method | Condition | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| ZeroGEN | Protein Sequence (Zero-Shot) | Generates novel ligands with high affinity for unseen targets; docking confirms interaction with key residues. |

| DiffSMol (Pocket+Shape) | Protein Pocket + Ligand Shape | 17.7% improvement in binding affinities over the best baseline PMG method. |

| ISM001-055 (Insilico Medicine) | AI-designed Inhibitor (Clinical) | Progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in 18 months; positive Phase IIa results in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis [38]. |

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Zero-Shot Molecule Generation Workflow

This diagram illustrates the complete workflow for a protein sequence-based zero-shot generation model, integrating key troubleshooting checkpoints.

Diagram 2: Score vs. Physical Force in Diffusion Models

This diagram clarifies the relationship between the learned score in a diffusion model and physical atomic forces, a key concept for troubleshooting 3D geometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for zero-shot generative modeling in LBDD.

| Item | Function & Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Equivariant Graph Neural Networks | Neural networks whose outputs rotate/translate equivariantly with their inputs. Critical for generating realistic 3D molecular structures as they respect the symmetries of physical space [36]. | Modeling the positional score component (s_r(x,t)) in a 3D diffusion model, ensuring it behaves like a physical force [36]. |

| Cross-Attention Mechanism | A deep learning mechanism that allows one data modality (e.g., protein sequence) to interact with and influence another (e.g., ligand structure). | In ZeroGEN, it enables the protein encoder to guide the ligand decoder, ensuring the generated molecule is relevant to the target [32]. |

| Contrastive Learning | A self-supervised learning technique that teaches the model to pull "positive" pairs (binding protein-ligand pairs) closer in embedding space and push "negative" pairs apart. | Pre-training a model to understand protein-ligand interaction relationships, which is foundational for zero-shot generalization to new targets [32]. |

| Similarity Kernel | A function that measures the similarity between two data points. In molecular generation, it can be based on shape or local atomic environments. | In SiMGen, a time-dependent similarity kernel is used to guide generation towards a desired 3D molecular shape without further training [36]. |

| Positional Embeddings (PEs) | Vectors that encode the position of tokens in a sequence. Crucial for Transformer models to understand order in SMILES strings or protein sequences. | In BERT models for molecular property prediction, different PEs (e.g., absolute, rotary) can significantly impact the model's accuracy and zero-shot learning capability [39]. |

The field of drug discovery is increasingly leveraging ultra-large chemical spaces, which contain billions or even trillions of enumerated compounds, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant computational challenges [40]. Navigating these vast spaces requires specialized tools and methodologies that can efficiently identify promising candidates while balancing the critical trade-off between structural novelty and predictive reliability in structure-based drug design [40]. The sheer size of these databases, often surpassing terabyte limits, exceeds the processing capabilities of standard laboratory hardware, necessitating novel computational approaches for speedy information processing [40].

This technical support guide addresses the practical challenges researchers face when working with ultra-large chemical spaces, focusing on two key strategies: similarity searching to find compounds with analogous properties to known actives, and scaffold hopping to identify novel molecular frameworks with maintained bioactivity [41]. By providing troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks, this resource aims to equip drug development professionals with the methodologies needed to navigate these complex chemical landscapes effectively.

Table 1: Core Software Tools for Chemical Space Navigation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTrees | Similarity Searching | Fuzzy pharmacophore descriptors, tree alignment | High-speed similarity search in billion+molecule spaces [40] |

| SpaceMACS | Scaffold Hopping & Substructure Search | Identity search, substructure search, MCS-based similarity | SAR exploration and compound evolution [40] |

| SpaceLight | Similarity Searching | Topological fingerprints, combinatorial architecture | Discovering close analogs in ultra-large spaces [40] |

| ReCore (BiosolveIT) | Scaffold Hopping | Brute-force enumeration with shape screening | Intellectual property positioning and liability overcome [42] |

| MolCompass | Visualization & Validation | Parametric t-SNE, neural network projection | Visual validation of QSAR/QSPR models and chemical space mapping [43] |

| ChemTreeMap | Visualization & Analysis | Hierarchical tree based on Tanimoto similarity | Interactive exploration of structure-activity relationships [44] |

Table 2: Critical Database Resources

| Resource | Content Type | Scale | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | Compound Database | 90+ million compounds | General reference and compound sourcing [45] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity Data | Curated bioassays | Target-informed searching and model training [44] |