Strategic Prodrug Design and Formulation: Enhancing Solubility, Permeability, and Targeted Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern prodrug strategies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategic Prodrug Design and Formulation: Enhancing Solubility, Permeability, and Targeted Delivery

Abstract

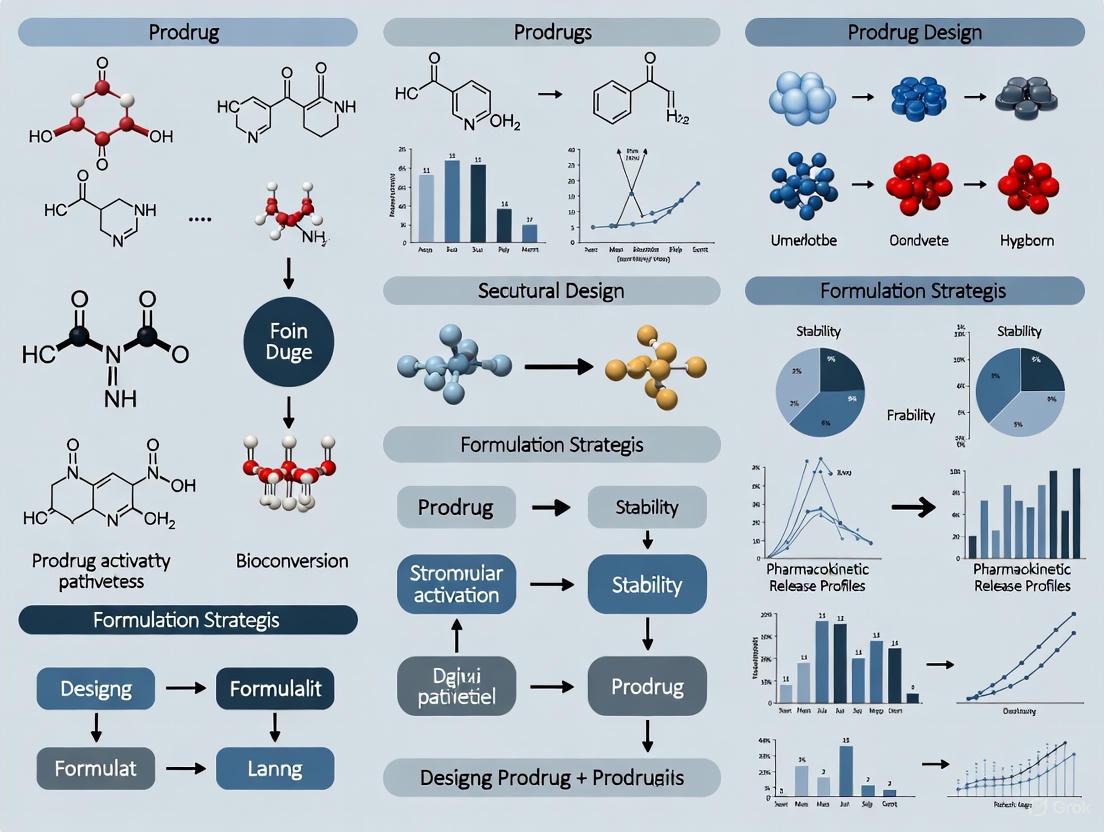

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern prodrug strategies for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of prodrug design, detailing how chemical modifications transform inactive compounds into active drugs to overcome key development challenges. The scope includes methodological approaches for enhancing solubility and permeability, practical troubleshooting for common formulation hurdles, and current validation techniques. By synthesizing recent advancements and real-world applications, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage prodrug technology for optimizing pharmacokinetic properties and achieving targeted therapeutic delivery.

Prodrug Fundamentals: Principles, Classifications, and Key Objectives in Modern Drug Development

A prodrug is a pharmacologically inactive compound that is metabolized within the body to release an active drug substance [1] [2]. This strategic approach is employed to overcome various barriers in drug delivery, such as poor solubility, low permeability, rapid metabolism, or significant side effects [3] [4]. The design of prodrugs allows for the optimization of a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties, ultimately enhancing its therapeutic efficacy and safety profile [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main types of prodrugs? Prodrugs are primarily classified into two major types based on their site of activation [1]:

- Type I Prodrugs are bioactivated inside cells (intracellularly). Examples include anti-viral nucleoside analogs and lipid-lowering statins.

- Type II Prodrugs are bioactivated outside cells (extracellularly), such as in digestive fluids or the circulatory system. Salicin and certain antibody-directed enzyme prodrugs (ADEPT) used in chemotherapy are examples. Some prodrugs can belong to multiple subtypes, known as "Mixed-Type" prodrugs, which are bioactivated at multiple sites in parallel or sequential steps [1].

2. Why use a prodrug instead of the active drug? The prodrug strategy offers several key advantages [3] [4]:

- Improve Bioavailability: Enhancing the drug's absorption and the amount that reaches the systemic circulation.

- Enhance Solubility: Making a poorly water-soluble drug more soluble for better formulation and absorption.

- Increase Site-Specificity: Targeting the drug to a specific organ, tissue, or cell type to reduce off-target effects.

- Minimize Side Effects: Reducing toxicity, irritation, or unpleasant taste/orodor of the parent drug.

- Overcome Rapid Metabolism: Protecting the drug from being deactivated too quickly before it can exert its effect.

3. What are common functional groups used in prodrug design? Common bioreversible functional groups and their activating mechanisms include [4]:

- Esters and Carbonates: Activated by ubiquitous enzymes called esterases and carboxylesterases.

- Phosphates and Phosphonates: Cleaved by phosphatases to improve water solubility.

- Carbamates and Amides: Cleaved by esterases or peptidases.

- Oximes and Imines: Susceptible to chemical hydrolysis.

4. What challenges are associated with prodrug development? Despite their benefits, prodrug development faces several challenges [5] [4]:

- Variable Activation: Inefficient or inconsistent activation due to inter-individual variability in enzyme expression or activity.

- Formulation Stability: Potential for chemical instability of the prodrug or its degradation products.

- Toxic Metabolites: The promoiety (carrier group) released during activation could be toxic.

- Premature Activation: The prodrug might convert to the active drug before reaching its target site.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Inefficient Prodrug Activation

Potential Cause: Inter-individual variability in the expression or activity of the enzyme responsible for prodrug activation (e.g., due to genetic polymorphisms) [4]. Solution Strategies:

- Enzyme Activity Profiling: Characterize the specific enzyme(s) responsible for activation (e.g., carboxylesterases, phosphatases, cytochrome P450 enzymes) using in vitro assays with human liver microsomes, recombinant enzymes, or target cell lysates [3].

- Linker Optimization: If the prodrug is carrier-linked, explore different linker chemistries that are substrates for enzymes with less variable expression [6] [7].

- Consider Bioprecursor Prodrugs: Design bioprecursor prodrugs that are activated by multiple or more ubiquitous metabolic pathways to reduce reliance on a single enzyme [4].

Problem 2: Poor Aqueous Solubility of the Prodrug

Potential Cause: The prodrug itself, despite design intentions, may have inadequate solubility for in vitro testing or formulation [5] [8]. Solution Strategies:

- Ionizable Promoieties: Incorporate highly ionizable groups, such as phosphate or amino acids, which can increase aqueous solubility by orders of magnitude [8] [4]. For example, phosphate ester prodrugs like fosphenytoin show dramatically improved solubility over their parent drugs [8].

- Formulation Aids: Employ advanced formulation techniques such as the creation of nano-suspensions or the use of lipid-based delivery systems to enhance solubility [9].

- Solid Dispersions: Develop solid dispersions where the prodrug is dispersed within a hydrophilic polymer matrix to improve dissolution rate [9].

Problem 3: Chemical Instability of the Prodrug in Formulation

Potential Cause: The linker between the drug and the promoiety may be chemically unstable under storage conditions (e.g., susceptible to hydrolysis or oxidation) [5]. Solution Strategies:

- Linker Modification: Synthesize prodrug analogs with altered linkers that provide better chemical stability while maintaining efficient enzymatic cleavage [7]. For instance, a more sterically hindered ester may hydrolyze slower.

- Control Microenvironment: Use lyophilization (freeze-drying), adjust the pH of liquid formulations, or incorporate stabilizers like antioxidants to improve shelf-life [5] [9].

- Packaging Innovations: Utilize specialized packaging materials that provide barriers to moisture and oxygen [9].

Problem 4: Unexpected Toxicity or Off-Target Effects

Potential Cause: Premature release of the active drug in non-target tissues, or toxicity from the promoiety released upon activation [4]. Solution Strategies:

- Tissue-Targeted Design: Develop prodrugs that are activated by enzymes specifically overexpressed at the target site (e.g., tumor-specific enzymes for chemotherapy prodrugs) [3] [4].

- Stimuli-Responsive Linkers: Design linkers that are cleaved by unique stimuli in the target microenvironment, such as low pH (tumors, lysosomes) or high reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [7] [4].

- Promoiety Selection: Evaluate the safety profile of different promoieties during the early design phase to select one with minimal toxicity [4].

Experimental Protocols for Prodrug Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Enzymatic Activation Kinetics

Objective: To determine the rate of conversion of a prodrug to its active metabolite by specific enzymes. Materials:

- Purified prodrug compound

- Source of enzyme (e.g., recombinant enzyme, liver microsomes, plasma, target cell lysate)

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4)

- Water bath or incubator

- HPLC or LC-MS system for analysis

Methodology:

- Incubation Preparation: Prepare a solution of the prodrug in a suitable buffer. Pre-warm the solution in a water bath at 37°C.

- Initiate Reaction: Add the enzyme preparation to the pre-warmed prodrug solution to start the reaction. Include a negative control without the enzyme.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), withdraw an aliquot from the incubation mixture.

- Reaction Termination: Immediately mix the aliquot with an equal volume of an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to denature the proteins and stop the reaction.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the samples to remove precipitated proteins. Analyze the supernatant using HPLC or LC-MS to quantify the remaining prodrug and the appearance of the active drug.

- Data Analysis: Plot the concentration of the active drug over time. Calculate the activation rate constant (k) or the half-life of conversion.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Solubility and Permeability

Objective: To measure the improvements in aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability afforded by the prodrug design. Materials:

- Prodrug and parent drug compounds

- Shaking water bath

- Caco-2 cell line (for permeability studies)

- Transwell plates

- HPLC system

Methodology:

- Aqueous Solubility:

- Add an excess amount of the prodrug to a vial containing a suitable aqueous buffer (e.g., pH 6.8 phosphate buffer to simulate intestinal fluid).

- Shake the vial in a water bath at 37°C for 24-48 hours to reach equilibrium.

- Filter or centrifuge the solution to remove undissolved material.

- Dilute the supernatant and analyze the drug concentration using HPLC. Compare with the solubility of the parent drug.

- Permeability (Caco-2 Model):

- Culture Caco-2 cells on semi-permeable membranes in Transwell plates until they form a confluent monolayer.

- Add the prodrug dissolved in buffer to the donor compartment (apical side for oral absorption studies).

- Incubate at 37°C. Sample from the receiver compartment (basolateral side) at regular intervals.

- Analyze samples by HPLC to determine the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp). A higher Papp value indicates better permeability.

Quantitative Data on Prodrug Performance

The following table summarizes how prodrug strategies have successfully improved the solubility of various parent drugs [8].

Table 1: Examples of Solubility Enhancement via Prodrug Design

| Parent Drug | Prodrug | Solubility of Parent Drug (mg/mL) | Solubility of Prodrug (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin | Phenytoin Phosphate | 0.02 | 142 |

| Clindamycin | Clindamycin-2-PO4 | 0.2 | 150 |

| Chloramphenicol | Chloramphenicol Succinate Sodium | 2.5 | 500 |

| Paclitaxel | PEG-Paclitaxel | 0.025 | 666 |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and materials essential for prodrug research and development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Prodrug Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Prodrug Research |

|---|---|

| Carboxylesterases | Key enzymes for hydrolyzing ester-based prodrugs; used in in vitro activation studies [4]. |

| Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions containing cytochrome P450 enzymes and other metabolizing enzymes; used to study oxidative activation and metabolic stability [4]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A model of the human intestinal epithelium; critical for assessing prodrug permeability and absorption potential [4]. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Enzyme used to study the activation of phosphate-containing prodrugs [8]. |

| HPMA Copolymer | A polymer used in the synthesis of polymer-drug conjugates and in Polymer-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy (PDEPT) [8]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Linkers | Linkers designed to break under specific conditions (e.g., low pH, high ROS); used to create targeted prodrugs [7]. |

Prodrug Activation and Pharmacokinetics

The diagram below illustrates the basic pharmacokinetic pathway of a prodrug after administration, leading to the release of the active drug and its subsequent elimination [10].

Rational Prodrug Design Workflow

This flowchart outlines a logical workflow for the rational design and evaluation of a prodrug, from identifying the problem to selecting an optimal candidate [3] [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a prodrug and what is its primary purpose in drug development? A prodrug is a biologically inactive or minimally active compound that undergoes enzymatic or chemical transformation within the body to release the active parent drug [11] [3]. The primary purpose is to optimize the physicochemical, biopharmaceutical, and pharmacokinetic properties of drugs, thereby overcoming challenges related to poor solubility, low permeability, high toxicity, and inadequate site-specificity [11] [12] [3]. It is a versatile strategy to improve drug delivery and therapeutic outcomes.

2. When should a researcher consider the prodrug approach for a lead compound? The prodrug approach should be considered when a pharmacologically active lead compound exhibits undesirable properties that hinder its clinical or commercial development. Key indicators include:

- Poor aqueous solubility, leading to formulation challenges and low bioavailability [11] [13].

- Low permeability, resulting in insufficient absorption and failure to reach intracellular targets [12] [13].

- Systemic toxicity or lack of target selectivity, particularly for chemotherapeutic agents [14] [15].

- Rapid pre-systemic metabolism, which shortens the drug's half-life and reduces exposure [3] [16].

3. What are the common functional groups and enzymes involved in prodrug activation? Common bioreversible functional groups used to link a drug to a carrier include esters, amides, carbonates, carbamates, and phosphates [11] [16]. These are typically activated by hydrolytic enzymes such as:

- Esterases: Found in plasma, liver, and other tissues, they are frequently targeted for hydrolyzing ester-based prodrugs [16].

- Phosphatases: Activate phosphate prodrugs [3].

- Peptidases and Proteases: Activate prodrugs designed with amino acid or peptide linkers, such as Valacyclovir, which is activated by human valacyclovirase [11] [3].

- Nitroreductases: Can activate nitroaromatic prodrugs, as seen in hypoxia-activated prodrugs [17].

- Cytochrome P450 enzymes: Often involved in the activation of bioprecursor prodrugs via oxidation or reduction reactions [16].

4. What are the major formulation challenges associated with prodrug development? Formulating prodrugs presents unique challenges, including:

- Chemical Instability: The drug-promoiety linker may be unstable, leading to premature degradation during storage or before reaching the target site [5].

- Reactive Degradation By-products: Degradation can generate reactive intermediates that may cause secondary degradation pathways or pose toxicity risks [5].

- Altered Solid-State Properties: The prodrug may exhibit different crystallinity, polymorphism, or hygroscopicity compared to the parent drug, complicating solid dosage form development [5].

- Solubility of Degradants: The aqueous solubility of the prodrug's degradation products must be considered to avoid precipitation in formulations [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Aqueous Solubility of Lead Compound

Problem: Your active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) has unacceptably low aqueous solubility, leading to poor dissolution and low oral bioavailability.

Solution: Design a water-soluble prodrug by attaching a hydrophilic promotety.

- Recommended Strategy: Synthesize phosphate ester or amino acid ester prodrugs. These groups significantly enhance aqueous solubility [11].

- Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Synthesis: Conjugate a phosphate group or an amino acid (e.g., valine, glycine) to the API via a biodegradable ester or other suitable linker [11].

- Solubility Measurement:

- Prepare a saturated solution of the prodrug in a suitable aqueous buffer (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate buffer).

- Shake the mixture for a predetermined time (e.g., 24 hours) at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Filter the solution through a 0.45 μm membrane filter.

- Analyze the concentration of the dissolved prodrug in the filtrate using a validated UV-Vis spectrophotometric or HPLC method [11].

- Chemical Stability Assessment:

Table 1: Examples of Prodrugs for Solubility Enhancement

| Parent Drug (Issue) | Prodrug Strategy | Resulting Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palmarumycin CP1 (High lipophilicity) | Glycyl ester derivative | >7-fold increase in water solubility | [11] |

| Oleanolic Acid (Solubility: 0.0012 μg/mL) | l-Valine ethylene-glycol-linked diester | Solubility >25 μg/mL; Increased oral bioavailability in rats | [11] |

| MSX-2 (A2A antagonist, low solubility) | Phosphate prodrug | Water solubility of 9.0 mg/mL | [11] |

| Antiviral Cf1743 (Low solubility) | Dipeptide prodrug (Val, Asn, Lys, Asp) | 4000-fold greater solubility; 7-15-fold greater bioavailability | [11] |

Issue 2: Low Permeability and Oral Absorption

Problem: Your API is sufficiently soluble but fails to cross biological membranes effectively, resulting in low oral absorption.

Solution: Design a prodrug to increase lipophilicity or to be recognized by active influx transporters.

- Recommended Strategy:

- Esterification: For drugs with carboxylic acid groups, create simple alkyl esters (e.g., ethyl ester) to enhance passive permeability [13].

- Transporter Targeting: For drugs with suitable handles, design prodrugs that are substrates for intestinal uptake transporters, such as the human peptide transporter 1 (hPEPT1), using amino acid or dipeptide promoieties [12] [3] [13].

- Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Lipophilicity Assessment:

- Determine the apparent partition coefficient (Log P) or distribution coefficient (Log D) at pH 7.4 for the prodrug and parent drug using the shake-flask method and n-octanol/water buffer systems.

- Analyze the samples by HPLC-UV to calculate the concentration in each phase. An increase in Log P/Log D indicates enhanced lipophilicity [12].

- Permeability Screening (In Vitro):

- Use Caco-2 or MDCK cell monolayers grown on permeable transwell supports.

- Add the prodrug to the donor compartment (e.g., apical side for oral absorption studies) and measure its appearance in the receiver compartment over time.

- Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp). A higher Papp for the prodrug compared to the parent API indicates improved permeability [12] [13].

- Transporter Interaction Studies:

- Perform the Caco-2 permeability assay in the presence and absence of a specific transporter inhibitor (e.g., glycylsarcosine for hPEPT1).

- A significant reduction in the Papp of the prodrug in the presence of the inhibitor confirms transporter-mediated uptake [13].

- Lipophilicity Assessment:

Table 2: Prodrug Strategies to Overcome Poor Permeability

| Parent Drug (BCS Class) | Prodrug Strategy | Mechanism of Improvement | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir (Class III/IV) | Valacyclovir | hPEPT1 transporter-mediated absorption | 3-5 fold increase in bioavailability [3] |

| SNX-2112 (Low solubility/permeability) | SNX-5422 (Glycine derivative) | Increased solubility and lipophilicity (pKa tuning) | Bioavailability increased from ~40% to ~80% in mice [13] |

| Melagatran (Low permeability) | Ximelagatran (N-hydroxyamidine) | Reduced basicity (pKa ~5) enhancing passive diffusion | Bioavailability increased from 6% to 20% in humans [13] |

| Tricin (Flavonoid) | Alanine-Glutamic acid dipeptide prodrug | Targeting hPEPT1 transporter | 45-fold greater exposure in rats [13] |

Issue 3: Off-Target Toxicity and Lack of Selectivity

Problem: Your API is potent but causes systemic side effects due to a lack of specificity for its intended target, such as in cancer therapy.

Solution: Design a prodrug that remains inactive until it reaches the target site, where a unique trigger (e.g., enzyme, pH, light) catalyzes its activation.

- Recommended Strategies:

- Enzyme-Activated Prodrugs: Leverage enzymes overexpressed in target tissues (e.g., glutathione S-transferases, β-lyases, or nitroreductases in some tumors) [14] [17].

- Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs (HAPs): Utilize the hypoxic environment of solid tumors for selective activation via nitroreduction [17].

- Bioorthogonal Activation: Use external triggers like near-infrared (NIR) light to activate prodrugs containing photolabile linkers (e.g., thioketal) [15].

- Experimental Validation Protocol:

- In Vitro Selectivity and Potency:

- Activation Kinetics:

- In Vivo Efficacy and Toxicity:

- Administer the prodrug and the parent API to animal models (e.g., tumor-bearing mice) at equimolar doses.

- Evaluate efficacy by measuring tumor growth inhibition.

- Assess toxicity by monitoring body weight, organ histology, and biomarkers (e.g., gastrointestinal toxicity). A successful prodrug will show similar or better efficacy with significantly reduced toxicity [14] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Determining Apparent Permeability (Papp) in Caco-2 Cells

Objective: To evaluate the ability of a prodrug to cross intestinal epithelial cell barriers and assess the involvement of active transporters.

Materials:

- Caco-2 cell line

- Transwell plates (e.g., 12-well, 0.4 μm pore size)

- Transport buffer (e.g., HBSS with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4)

- Test compounds (Prodrug and parent drug)

- Transporter inhibitors (e.g., Glycylsarcosine for hPEPT1)

- HPLC system with UV or MS detection

Method:

- Cell Culture: Seed Caco-2 cells on transwell inserts at a high density and culture for 21 days to allow full differentiation and expression of transport proteins. Confirm monolayer integrity by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER > 300 Ω×cm²).

- Experiment Setup: Pre-wash the monolayers with transport buffer. Add the test compound to the donor compartment (e.g., apical for A-to-B transport). Add fresh buffer to the receiver compartment (basolateral).

- Sampling: Incubate at 37°C with gentle shaking. Collect samples from the receiver compartment at regular intervals (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 min) and replace with fresh buffer.

- Analysis: Quantify the compound concentration in all samples using HPLC.

- Calculation: Calculate the Papp (cm/s) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the flux rate (mol/s), A is the membrane surface area (cm²), and C₀ is the initial donor concentration (mol/mL) [12] [13].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Enzymatic Prodrug Activation

Objective: To demonstrate and quantify the conversion of a prodrug to its active parent drug by a specific enzyme.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., esterase, phosphatase, nitroreductase) or target cell/tissue lysate

- Prodrug solution

- Appropriate incubation buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Co-factors (e.g., NADPH for nitroreductases)

- Water bath or incubator shaker (37°C)

- HPLC or LC-MS system

Method:

- Incubation: Prepare a solution of the prodrug in the incubation buffer. Add the enzyme or lysate to initiate the reaction. Include a control without the enzyme.

- Time Course: Incubate the mixture at 37°C. Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) and immediately quench the reaction (e.g., by adding ice-cold acetonitrile or acid).

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the quenched samples to precipitate proteins. Collect the supernatant for analysis.

- Analysis: Inject the supernatants into the HPLC/LC-MS system to separate and quantify the remaining prodrug and the generated parent drug.

- Data Analysis: Plot the concentration of the parent drug versus time. Calculate the activation half-life and the Michaelis-Menten parameters (Km and Vmax) if using a purified enzyme system [14] [16] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Prodrug Research and Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Prodrug Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An in vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium to assess permeability and transporter involvement. | Screening prodrug permeability and confirming hPEPT1-mediated uptake [12] [13]. |

| Esterases (e.g., from porcine liver) | Hydrolytic enzymes used to study the activation kinetics of ester-based prodrugs. | Evaluating the conversion of valine-ester prodrugs to their parent drugs [11] [16]. |

| Diboron Reagents (e.g., B2(OH)4) | Bioorthogonal reducing agents used in conjunction with organocatalysts for controlled prodrug activation. | Activating nitroaromatic prodrugs in cellular and animal models [17]. |

| 4,4'-Bipyridine | An organocatalyst that mediates bioorthogonal nitro-reduction with diboron reagents. | Enabling metal-free, controlled activation of prodrugs in biological systems [17]. |

| Specific Transporter Inhibitors | Pharmacological tools to confirm the role of specific influx transporters in prodrug uptake. | Using glycylsarcosine to inhibit hPEPT1 and validate transporter-targeted design [13]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Prodrug Optimization Workflow

Prodrug Activation Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between carrier-linked prodrugs and bioprecursors?

Carrier-linked prodrugs consist of an active parent drug covalently linked to a carrier group (or promoiety) through a biodegradable linkage such as an ester or amide bond [18] [11]. The carrier is typically chosen to modify the drug's physicochemical properties. In contrast, bioprecursor prodrugs do not contain a carrier group but are inactive molecules that undergo molecular modification via metabolic reactions (often redox or conjugation reactions) to generate the active drug [18] [11]. They are essentially substrates for metabolic enzymes.

Q2: How does the Type I/II classification system relate to these structural classifications?

The Type I/II system classifies prodrugs based on their site of activation, whereas carrier-linked and bioprecursor are structural classifications. A single structural class can often fall into either activation type, as shown in the table below [19].

Table 1: Interrelationship Between Prodrug Classification Systems

| Activation Site / Structural Type | Carrier-Linked Prodrug | Bioprecursor Prodrug |

|---|---|---|

| Type I: Intracellular Activation | Levodopa (L-DOPA) [4] | Codeine (converted to morphine by CYP2D6) [19] [20] |

| Type II: Extracellular Activation | Valacyclovir (activated in intestine/liver) [3] [19] | Sulfasalazine (activated by gut bacteria) [20] |

Q3: What are the most common functional groups used in designing carrier-linked prodrugs?

Ester bonds are the most prevalent, accounting for over 50% of marketed prodrugs [18]. Other common functional groups include carbonates, carbamates, amides, and phosphates. The choice of group depends on the desired hydrolysis rate, stability, and the enzyme responsible for activation [18] [4].

Table 2: Common Functional Groups in Carrier-Linked Prodrugs

| Functional Group | Key Feature | Example Prodrug (Active Drug) |

|---|---|---|

| Ester | Hydrolyzed by ubiquitous esterases; most common approach [18]. | Oseltamivir (Oseltamivir carboxylate) [18] [4] |

| Phosphate/Ester | Greatly enhances water solubility; activated by phosphatases [18] [4]. | Fosphenytoin (Phenytoin) [18] |

| Amide | More stable than esters; can be designed for transporter targeting [18]. | LY544344 (LY35470) [18] |

| Carbamate | Stable against hydrolysis; often used for sustained release [4]. | Irinotecan (SN-38) [19] [4] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent or Incomplete Prodrug Activation

Potential Cause: Variability in enzyme expression or activity. Enzymes like carboxylesterases, phosphatases, and cytochrome P450 isoforms can have significant inter-individual variability due to genetics, drug interactions, or disease states [4].

Solution:

- Characterize Enzyme Kinetics: Determine the Michaelis-Menten constants (Km and Vmax) for the enzymatic conversion of your prodrug using in vitro systems (e.g., liver microsomes, human plasma, or specific recombinant enzymes) [18].

- Use Genotyped Tissues/Enzymes: If a polymorphic enzyme (e.g., CYP2D6 or CYP2C19) is involved, use characterized enzyme sources to understand the impact of genetics on activation rate [19].

- Validate In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC): Ensure your chosen in vitro activation system reliably predicts in vivo behavior.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Metabolic Stability and Activation in Plasma

Objective: To evaluate the in vitro stability and conversion rate of a prodrug in plasma, which contains various hydrolytic enzymes.

Materials:

- Prodrug compound

- Blank plasma (from relevant species, e.g., rat, human)

- Incubation buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, PBS)

- Precipitation agent (e.g., acetonitrile with internal standard)

- Water bath or incubator (maintained at 37°C)

- Centrifuge

- Analytical instrument (e.g., LC-MS/MS)

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-warm plasma in a water bath at 37°C for 10 minutes. Prepare a stock solution of the prodrug in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO), then dilute in pre-warmed buffer.

- Incubation: Initiate the reaction by mixing the prodrug solution with plasma to achieve a final concentration relevant to your study (e.g., 1 µM). Vortex immediately.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), withdraw an aliquot (e.g., 50 µL) and immediately mix with a cold precipitation agent (e.g., 150 µL acetonitrile) to stop the reaction.

- Processing: Centrifuge the samples (e.g., 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to precipitate proteins. Transfer the clear supernatant to vials for analysis.

- Analysis: Quantify the concentrations of the remaining prodrug and the formed active drug using a validated analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

Interpretation: Plot the decline of prodrug and the appearance of the active drug over time. Calculate the half-life (t~1/2~) of the prodrug and the conversion rate.

Challenge 2: Poor Aqueous Solubility of the Parent Drug Leading to Formulation Difficulties

Solution: Implement a water-solubilizing promoiety strategy. Common groups include phosphate esters, amino acids, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains [18] [11].

Experimental Protocol: Kinetic Aqueous Solubility Assay

Objective: To compare the aqueous solubility of a parent drug and its prodrug derivative.

Materials:

- Test compounds (Parent drug and prodrug)

- Aqueous buffer (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4)

- Thermostated shaker or bath (37°C)

- Centrifuge and filter plates (e.g., 0.45 µm pore size)

- Analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC-UV)

Method:

- Saturation: Add an excess of solid compound to a known volume of buffer in a vial. Shake vigorously for 24 hours at 37°C to achieve equilibrium.

- Separation: Centrifuge the samples or pass them through a pre-warmed filter plate to separate the undissolved solid from the saturated solution.

- Quantification: Dilute the clear supernatant appropriately and analyze the concentration of the dissolved compound using a validated HPLC-UV method. A standard curve of the compound in a known solvent is required for quantification.

Interpretation: The concentration measured in the saturated solution is the kinetic solubility. A successful solubilizing prodrug will show a significant (e.g., 10 to 1000-fold) increase in solubility compared to the parent drug [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Prodrug Metabolism and Analysis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Prodrug Research |

|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes (Human/Rat) | Contains cytochrome P450 enzymes and other Phase I metabolizing enzymes; used to study oxidative activation of bioprecursors [4]. |

| Recombinant Enzymes (e.g., hCE1, hCE2) | Specific carboxylesterases for characterizing ester-based prodrug activation kinetics and enzyme specificity [18]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A model of human intestinal permeability; used to assess carrier-linked prodrug absorption and transporter involvement [3]. |

| Plasma (Various Species) | Source of hydrolytic enzymes (esterases, phosphatases) for evaluating the stability and activation of prodrugs in systemic circulation [18]. |

| Specific Chemical Inhibitors | Inhibitors for enzymes like CYP450s or esterases to confirm the metabolic pathway responsible for prodrug activation [4]. |

Prodrugs, defined as biologically inactive compounds that undergo conversion into active pharmaceuticals within the body, have evolved from a serendipitous discovery to a cornerstone of rational drug design [3] [21]. This strategy is instrumental in overcoming common drug development hurdles, such as poor solubility, inadequate permeability, and suboptimal pharmacokinetics [22] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the prevalence and impact of prodrugs is crucial for guiding molecular optimization processes. This technical resource provides a data-driven analysis of the prodrug market, supported by experimental insights and troubleshooting guides relevant to prodrug design and formulation research.

Quantitative Analysis of Prodrug Approvals

The prodrug approach represents a significant and growing segment of the pharmaceutical market. The quantitative data below underscores its substantial impact.

Table 1: Prevalence of Prodrugs in FDA-Approved New Molecular Entities [22] [23] [24]

| Time Period | Total FDA-Approved Small Molecule NMEs | Number of Prodrugs | Percentage of Prodrugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 - 2018 | ~249 | At least 30 | ~12% |

| 2012 - 2022 | Information Missing | Information Missing | ~13% |

| 2015 | 32 | 7 | ~20% |

| 2010 - 2014 | 127 | 13 | ~10.2% |

Table 2: Global Prodrug Research Activity (2014-2024) [22] [25]

| Research Activity Metric | Annual Average (Last Decade) | Recent Peak (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Global Patent Applications | > 4,800 | 5,730 |

| Scientific Publications | ~ 1,261 | Information Missing |

Overall, it is estimated that approximately 10% of all commercially available medicines worldwide are prodrugs [3] [21] [24]. The therapeutic areas dominating recent clinical trials for prodrugs include cancer (35%), central nervous system disorders (16%), and antiviral therapies (14%) [22] [25].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides for Prodrug Research

FAQ 1: What are the primary strategic goals when designing a prodrug?

The prodrug strategy is employed to achieve several key objectives [12] [3]:

- Enhancing Bioavailability: This is the most common goal, primarily achieved by improving a drug's solubility and membrane permeability. A review of prodrug design goals found that 59% were aimed at enhancing bioavailability, with 35% targeting permeability and 15% targeting solubility improvements [12].

- Achieving Site-Specific Targeting: Modern prodrugs can be designed to exploit specific enzymes or transporters that are overexpressed in target tissues, such as tumors or sites of inflammation, thereby reducing systemic toxicity [3].

- Overcoming Rapid Metabolism: Chemical moieties like carbamates and amides can be used to shield a drug from extensive first-pass metabolism, thereby increasing its systemic exposure [22].

- Reducing Toxicity and Side Effects: By masking the active drug until it reaches the site of action, prodrugs can minimize off-target effects and improve patient tolerability [3] [21].

FAQ 2: Which functional groups are most commonly used in prodrug clinical trials and why?

The selection of a promoiety is guided by the desired pharmacokinetic profile, particularly the kinetics of enzymatic hydrolysis.

Table 3: Common Promoieties in Prodrugs (2014-2024 Clinical Trials) [22]

| Promoiety | Prevalence in Clinical Trials | Hydrolysis Kinetics & Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ester | 27% | Rapid hydrolysis; widely used to improve lipophilicity and absorption. |

| Phosphate | 27% | Rapid hydrolysis; primarily used to enhance aqueous solubility. |

| Amide | 12% | Slower, more stable hydrolysis; useful for moderating rapid metabolism. |

| Carbamate | 6% | Slower, more stable hydrolysis; useful for moderating rapid metabolism. |

| Salts | 8% | Not a promoiety per se, but used with prodrugs to improve solubility and crystallinity. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Inconsistent Activation of Ester-Based Prodrugs

Problem: An ester prodrug demonstrates excellent in vitro permeability but shows variable and low efficacy in in vivo models, suggesting inconsistent activation.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Potential Cause 1: Enzyme Polymorphism. The activating enzyme (e.g., carboxylesterase) may have genetic polymorphisms leading to variable expression or activity across a population [23] [21].

- Solution: Conduct in vitro metabolism studies using human hepatocytes from multiple donors. During early development, perform pharmacogenomic screening to identify susceptible populations.

- Potential Cause 2: Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs). Coadministered drugs may inhibit the enzymes required for prodrug activation.

- Solution: A classic example is the interaction between clopidogrel (prodrug) and omeprazole, which inhibits the CYP2C19 enzyme required for activation [21]. During preclinical development, screen for DDIs using recombinant enzymes and human liver microsomes.

- Potential Cause 3: Saturation of Activation Pathway. The enzymatic conversion may be saturable at higher doses, leading to non-linear pharmacokinetics.

- Solution: Perform dose-ranging studies in animal models to characterize the saturation kinetics and adjust the dosing regimen accordingly.

FAQ 3: How is permeability assessed during prodrug development?

Permeability is a critical parameter for prodrug success. Researchers use a combination of methods to evaluate it [12]:

- In Silico Methods: Computational models use filters like the "Rule of Five" and calculate parameters like logP (partition coefficient) to predict permeability during early-stage design [12].

- In Vitro Models: Cell-based assays, particularly Caco-2 cell monolayers, are the gold standard for determining the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) of a prodrug candidate.

- Ex Vivo and In Situ Methods: Techniques like gut sacs and intestinal perfusion provide more physiologically relevant data on effective permeation (Peff).

Diagram: Workflow for Evaluating Prodrug Permeability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Prodrug Research and Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Prodrug R&D |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An immortalized cell line from human colon adenocarcinoma used as an in vitro model of the human intestinal mucosa to assess permeability and transport mechanisms [12]. |

| Human Hepatocytes | Primary liver cells used to study first-pass metabolism and enzymatic activation (or deactivation) of prodrug candidates, crucial for predicting in vivo performance [23]. |

| Recombinant Metabolic Enzymes (e.g., CYP450 isoforms, CES1/2) | Used to identify the specific enzymes responsible for prodrug activation, enabling screening for polymorphisms and potential drug-drug interactions [21]. |

| Specific Transporter-Expressing Cell Lines (e.g., hPEPT1, OATP) | Engineered cell lines that overexpress specific uptake transporters. They are vital for developing targeted prodrugs that utilize carrier-mediated transport, like valacyclovir [3]. |

| Simulated Biological Fluids (e.g., SGF, SIF) | Used in dissolution testing to evaluate the chemical stability and release profile of the prodrug in various regions of the gastrointestinal tract. |

Case Study: Mechanism of Valacyclovir Activation

Valacyclovir is a successful prodrug of acyclovir, designed to overcome poor oral bioavailability.

Diagram: Mechanism of Valacyclovir Activation and Targeting

Experimental Insight: The high bioavailability of valacyclovir is achieved through a "double-targeted" approach [3]:

- Transporter-Mediated Absorption: The prodrug is efficiently absorbed across the intestinal epithelium by the human peptide transporter 1 (hPEPT1).

- Enzyme-Mediated Activation: Once inside the cell, it is rapidly hydrolyzed by the enzyme human valacyclovirase to release acyclovir.

This case highlights the importance of considering both transport and enzymatic activation pathways in the rational design of modern prodrugs.

Design and Application: Chemical Strategies and Real-World Case Studies

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Fischer Esterification

Q: My Fischer esterification reaction is yielding very little product. What could be the cause and how can I improve the yield?

A: The Fischer esterification is an equilibrium reaction, and low yields are often due to the equilibrium favoring the starting materials. To drive the reaction toward ester formation:

- Use a large excess of your alcohol reactant. One study showed that increasing the ethanol to acetic acid ratio from 1:1 to 10:1 improved the ester yield from 65% to 97% [26].

- Remove water from the reaction mixture as it forms. Employ a Dean-Stark trap, which allows for the continuous azeotropic removal of water, preventing the reverse hydrolysis reaction and shifting the equilibrium [26] [27].

- Ensure you are using a strong acid catalyst like concentrated sulfuric acid or toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH) [26] [27].

Q: Can I use phenolic alcohols or tertiary alcohols in a Fischer esterification?

A: This is a significant limitation of the method.

- Phenol esters are difficult to form because phenol is a weaker nucleophile compared to typical alcohols, a problem exacerbated in acidic conditions [27].

- Tertiary alcohols are generally not suitable because they readily undergo dehydration to alkenes under the strong acidic conditions required for the reaction [27]. For both scenarios, alternative strategies such as using more reactive acid chlorides or carboxylate salts with alkyl halides are recommended [27].

Phosphorylation

Q: I am performing an enzymatic phosphorylation of an oligonucleotide using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) and getting few or no transformants. What should I troubleshoot?

A: This is a common issue in molecular biology workflows. The causes and solutions are summarized in the table below [28].

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Phosphorylation | Impurities in DNA substrate (salt, phosphate, ammonium ions) inhibiting the kinase. | Purify the DNA substrate prior to the phosphorylation reaction. |

| Blunt or 5' recessed DNA ends. | Heat the DNA substrate with buffer for 10 minutes at 70°C, then rapidly chill on ice before adding ATP and enzyme. | |

| Missing ATP. | Add ATP to a final concentration of 1 mM. Alternatively, use T4 DNA Ligase Buffer which contains ATP. |

Q: When mapping protein phosphorylation sites with mass spectrometry (MS), I have low coverage and can't locate the precise modified residue. How can I improve my results?

A: Phosphorylation site mapping by MS has several inherent challenges. Key strategies to overcome them include [29]:

- Use Multiple Proteases: Trypsin is the most common protease, but it may not generate ideal peptides from all protein regions. Using a second enzyme like GluC or chymotrypsin can dramatically improve sequence coverage.

- Account for Low Stoichiometry: The detected phosphorylation may be at a very low level and not biologically relevant. Employ quantitative MS methods (e.g., SILAC, isobaric tags) to measure phosphorylation stoichiometry and focus on sites that change under relevant conditions.

- Address Ambiguous Site Localization: When phosphorylation sites are close together, MS/MS spectra may not have enough information to pinpoint the exact residue. Use scoring algorithms like the Ascore to statistically evaluate site-assignment confidence.

Carrier-Linkage for Prodrugs

Q: What are the key considerations when designing a water-soluble carrier-linked prodrug?

A: An ideal prodrug should balance stability and activation [11]:

- Promoter Stability: The prodrug must be stable enough to survive absorption but must efficiently release the active drug at the target site.

- Aqueous Solubility: The carrier (e.g., phosphate group, amino acid) should significantly improve the parent drug's water solubility.

- Targeted Activation: The linker should be designed for enzymatic cleavage at the site of action. For example, using a dipeptide carrier that is a substrate for dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (DPPIV) can facilitate activation in specific tissues [11].

Q: Which chemical carriers are most effective for improving water solubility?

A: Ester-linked carriers, particularly phosphate groups and amino acids, are highly effective. The table below summarizes successful examples from recent research.

| Parent Drug (Issue) | Prodrug Carrier | Solubility Improvement & Key Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSX-2 (Low solubility) | L-Valine ester | Solubility: 7.3 mg/mL (vs. less soluble parent). Stable in solution, rapid enzyme-triggered release. | [11] |

| Cf1743 (Low solubility & bioavailability) | Dipeptide ester (Valine-based) | Solubility: >4000-fold increase. Bioavailability: 7-15 fold higher than parent drug. | [11] |

| Oleanolic Acid (Low solubility & bioavailability) | L-Valine-ethylene glycol diester | Solubility: Increased from 0.0012 µg/mL to >25 µg/mL. Enhanced oral bioavailability in rats. | [11] |

| Palmarumycin CP1 (High lipophilicity) | Glycine ester | Solubility: >7 times more soluble in water than parent drug. | [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Standard Fischer Esterification

This protocol describes the synthesis of an ester from a carboxylic acid and a primary or secondary alcohol using an acid catalyst [26] [27].

Reagent Solutions:

- Carboxylic Acid Substrate

- Alcohol (e.g., ethanol, methanol) - used in excess as solvent

- Acid Catalyst - concentrated sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) or p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH)

- Saturated Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) solution

- Anhydrous Salt - e.g., magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) or sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄)

- Extraction Solvents - Diethyl ether or ethyl acetate, and brine

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: In a round-bottom flask, combine the carboxylic acid (1.0 equivalent) with a large excess of the alcohol (e.g., 10-100 equivalents). Slowly add a catalytic amount of concentrated sulfuric acid (e.g., 0.1 equivalents) while stirring.

- Reflux: Attach a reflux condenser and heat the mixture to reflux for 1-8 hours. For higher yields: Use a Dean-Stark trap in place of the condenser to remove water azeotropically.

- Reaction Work-up: After cooling, carefully neutralize the mixture by adding a saturated sodium bicarbonate solution slowly until CO₂ evolution ceases and the aqueous layer is basic.

- Extraction: Transfer the mixture to a separatory funnel. Extract the ester from the aqueous layer with an organic solvent (e.g., diethyl ether, 3 x 15 mL). Wash the combined organic layers with brine to remove residual water.

- Drying and Concentration: Dry the organic layer over an anhydrous salt like MgSO₄. Filter off the solid and concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator to obtain the crude ester.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by distillation or column chromatography as needed.

Detailed Protocol: Mapping Phosphorylation Sites by Mass Spectrometry

This workflow outlines the key steps for identifying serine, threonine, or tyrosine phosphorylation on a protein of interest [29].

Reagent Solutions:

- Purified Protein of Interest

- Protease - Trypsin (most common), Lys-C, GluC, or Chymotrypsin

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS/MS)

- Phosphopeptide Enrichment Resins - e.g., TiO₂, IMAC, Phos-Tag

- Lysis/Wash Buffers - Suitable for the protein and protease

- Stable Isotope Labels (for quantification) - SILAC amino acids or chemical tags (e.g., iTRAQ, TMT)

Methodology:

- Protein Digestion: Denature and digest the purified protein with a sequence-specific protease (e.g., trypsin) to generate a mixture of peptides.

- Phosphopeptide Enrichment (Optional but Recommended): To reduce sample complexity and increase sensitivity, enrich the peptide mixture for phosphopeptides using affinity resins like titanium dioxide (TiO₂) or immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC).

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate the peptides using nano-liquid chromatography and analyze them by tandem mass spectrometry. The instrument will measure the mass of intact peptides (MS1) and then fragment selected ions to obtain sequence data (MS2).

- Database Search and Site Localization: Use search algorithms (e.g., MaxQuant, SEQUEST) to match the experimental MS/MS spectra against theoretical spectra from a protein database, accounting for potential phosphorylation. Apply localization scoring algorithms (e.g., Ascore) to assign the specific modified residue with a confidence score.

- Validation (Crucial): Confirm the functional relevance of identified sites by mutating the phosphorylated residue (e.g., to alanine) and assessing the functional or phenotypic consequences in a biological assay.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Prodrug Activation via Enzyme-Triggered Hydrolysis

This diagram illustrates the general mechanism for a carrier-linked bipartite prodrug, where an enzyme cleaves the carrier group to release the active drug.

Phosphorylation Site Mapping Workflow

This flowchart outlines the core steps for identifying protein phosphorylation sites using mass spectrometry.

Fischer Esterification Mechanism

This diagram details the step-by-step mechanism (PADPED) for the acid-catalyzed esterification of a carboxylic acid.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents used in the featured chemical techniques and their primary functions in a research setting.

| Reagent / Enzyme | Primary Function in Research | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) | Catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to the 5' terminus of DNA/RNA. | Phosphorylation of oligonucleotides for molecular biology techniques like ligation and labeling [28]. |

| Trypsin / Lys-C | Proteases that cleave proteins at specific amino acid residues (C-terminal to Lys/Arg) to generate peptides for MS analysis. | Protein digestion for bottom-up proteomics and phosphorylation site mapping [29]. |

| Acid Catalysts (H₂SO₄, TsOH) | Protonate the carbonyl oxygen of a carboxylic acid, making it more electrophilic and catalyzing the reaction with an alcohol. | Fischer esterification reaction to form ester bonds [26] [27]. |

| Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (DPPIV) | A cell-surface enzyme that cleaves dipeptides from the N-terminus of proteins. Used as a target for activation. | Designed cleavage of dipeptide-linked prodrugs for targeted drug release, e.g., in leukocytes [11]. |

| Dean-Stark Apparatus | A laboratory technique for the continuous removal of water from a reaction mixture via azeotropic distillation. | Driving equilibrium in reversible reactions like Fischer esterification toward product formation [26]. |

| Stable Isotope Tags (SILAC, iTRAQ) | Allow for accurate relative quantification of peptides/proteins between different samples by mass spectrometry. | Determining phosphorylation stoichiometry and identifying dynamically regulated phosphorylation sites [29]. |

Enhancing Membrane Permeability and Oral Bioavailability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary biological barriers that limit oral drug bioavailability? Oral drug bioavailability is primarily limited by a series of physiological barriers within the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). These can be categorized as follows [30]:

- Anatomical Factors: The GIT has varying environments from the stomach to the colon. The stomach's strong acidic environment (pH 1.0–2.5) can degrade acid-labile drugs, while the small intestine, despite its large surface area, contains pancreatic enzymes and bile salts that can inactivate certain compounds. The colon has a complex microbiome that can metabolize drugs [30].

- Biochemical Barriers: This includes the pH gradient throughout the GIT and the presence of digestive enzymes that can break down drugs, particularly proteins and peptides [30].

- Physiological Barriers: The intestinal epithelium is a phospholipid bilayer that favors the absorption of lipophilic molecules and restricts hydrophilic and large molecules. Furthermore, a dynamic mucus layer covers the epithelium, which can trap foreign particles and prevent direct contact with the absorptive surface [30].

FAQ 2: How does the prodrug strategy improve oral bioavailability? The prodrug strategy involves the chemical modification of an active drug into an inactive derivative that undergoes conversion to the active parent compound within the body. This approach is used to overcome a range of limitations [3] [31] [32]:

- Improving Solubility and Permeability: By attaching promoieties, a prodrug can enhance the drug's water solubility or its lipophilicity, thereby improving dissolution or passive diffusion across the intestinal membrane.

- Overcoming First-Pass Metabolism: Prodrugs can be designed to be resistant to metabolic enzymes in the gut and liver, ensuring more intact drug reaches the systemic circulation.

- Enabling Targeted Delivery: Modern prodrugs can be engineered to target specific enzymes or transporters in the intestinal membrane (e.g., the hPEPT1 transporter for valacyclovir), which can enhance absorption and enable site-specific release [3].

FAQ 3: What formulation strategies can enhance the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs? For compounds with poor aqueous solubility, which is a common challenge in drug discovery, several formulation strategies can be employed [33] [30] [34]:

- Lipid and Surfactant-Based Systems: Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) and liposomes can enhance solubility and absorption by facilitating drug transport via the lymphatic system, bypassing first-pass metabolism.

- Nanoparticulate Formulations: Drug nanoparticles, nanoemulsions, and other nanocarriers can dramatically increase the surface area for dissolution, protect the drug from the harsh GIT environment, and improve absorption.

- Solid Dispersions: Dispersing a poorly soluble drug in a hydrophilic polymer carrier can create a supersaturated solution in the GIT, significantly driving absorption.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Absorption Due to Low Permeability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution | Key Reagents/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inherently low passive diffusion | - Caco-2 assay: Measures transport of the compound across a model of the intestinal epithelium. [34]- PAMPA (Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay): A high-throughput screen for passive permeability. [34] [35] | - Prodrug design: Incorporate lipophilic promoieties (e.g., ester chains) to increase log P. [3] [32]- Permeation enhancers: Use excipients like surfactants, fatty acids, or glycerides (use with caution due to potential for epithelial damage). [33] [32] | - Caco-2 cell lines- PAMPA plates & artificial membranes- Prodrug synthesis reagents (e.g., acyl chlorides for esterification) |

| Substrate for efflux transporters (e.g., P-gp) | - Bidirectional Caco-2 assay: Asymmetric transport indicates efflux activity. [34] | - Chemical modification: Alter the drug structure to avoid recognition by efflux transporters.- Co-administration with efflux inhibitors (though this has clinical safety implications). | - Known efflux transporter substrates/inhibitors (e.g., Verapamil for P-gp) |

| Metabolic instability in the gut wall | - Incubation with intestinal homogenates or specific enzymes (e.g., esterases) and measure parent compound loss over time. [34] | - Prodrug approach: Design a prodrug that is resistant to gut enzymes but cleaved in systemic circulation or the target tissue (e.g., tenofovir alafenamide). [3] | - Intestinal S9 fractions or specific purified enzymes (e.g., carboxylesterases) |

Problem: Poor Bioavailability Due to Low Solubility/Dissolution Rate

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution | Key Reagents/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| High crystallinity & low aqueous solubility | - Equilibrium solubility measurement in biorelevant media (e.g., FaSSIF, FeSSIF). [34] | - Particle size reduction (e.g., nanomilling) to increase surface area. [34]- Solid dispersions with polymers like HPMC or PVP to create amorphous drug. [34]- Lipid-based formulations (e.g., SEDDS) to maintain drug in a solubilized state. [33] [34] | - Biorelevant media powders (FaSSIF/FeSSIF)- Polymers for dispersion (HPMC, PVP, Soluplus)- Lipids & surfactants (e.g., Gelucire, Labrasol) |

| Poor dissolution in GI pH range | - Dissolution testing across a pH gradient (1.2 to 7.4). [30] | - Salt formation to improve dissolution at specific pH.- Prodrug approach: Attach a hydrophilic ionizable group (e.g., phosphate) to enhance water solubility. [3] [31] | - USP dissolution apparatus- pH adjustment solutions |

Problem: Extensive Presystemic (First-Pass) Metabolism

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution | Key Reagents/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) metabolism in the liver | - Metabolic stability assay in liver microsomes or hepatocytes. [34] | - Prodrug design: Create a structure that is not a substrate for the metabolizing enzyme but releases the active drug after absorption.- Chemical modification: Block or substitute the metabolic soft spot on the molecule. | - Liver microsomes (human/rat)- NADPH regenerating system |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis in the gut lumen | - Stability assessment in simulated intestinal fluid or with pancreatic enzymes. [30] | - Enteric coating: A formulation strategy to protect the drug from stomach acid and intestinal enzymes until it reaches the absorption site.- Prodrug: Mask susceptible functional groups (e.g., esters) to prevent enzymatic recognition. [3] | - Simulated intestinal fluids- Pancreatin |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing Passive Membrane Permeability using PAMPA

Principle: The Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay (PAMPA) is a high-throughput, non-cell-based model used to predict passive transcellular permeability by measuring the rate of drug diffusion across a lipid-infused artificial membrane [34] [35].

Procedure:

- Membrane Preparation: A hydrophobic filter membrane is coated with a solution of phospholipids (e.g., phosphatidylcholine) in an organic solvent to form an artificial lipid layer. The solvent is allowed to evaporate completely.

- Plate Assembly: The donor plate (containing the compound solution) is placed over the acceptor plate, which contains a blank buffer solution (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4), so that the artificial membrane is between them.

- Dosing and Incubation: A solution of the test compound (typically 50-100 µM) in a physiologically relevant buffer (e.g., pH 6.5 for small intestine) is added to the donor well. The assembly is incubated for a set period (e.g., 2-16 hours) at room temperature without agitation.

- Sample Analysis: After incubation, the concentration of the compound in both the donor and acceptor compartments is quantified using a suitable analytical method (e.g., UV spectroscopy, HPLC).

- Data Calculation: The permeability coefficient (Pe) is calculated using the following formula, where CA(t) is the concentration in the acceptor well at time t, CD is the concentration in the donor well at time zero, VD and VA are the volumes of the donor and acceptor wells, A is the filter area, and t is the incubation time.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Metabolic Stability in Liver Microsomes

Principle: This assay determines the intrinsic metabolic stability of a drug candidate by incubating it with liver microsomes, which contain cytochrome P450 enzymes, and measuring the disappearance of the parent compound over time [34].

Procedure:

- Incubation Preparation: Prepare a reaction mixture containing:

- 0.1 M Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4)

- Liver Microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL protein concentration)

- Test Compound (typically 1 µM)

- Pre-Incubation: Allow the mixture to equilibrate for 5 minutes in a water bath at 37°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding an NADPH regenerating system (provides the cofactors essential for CYP enzyme activity).

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes), withdraw an aliquot of the incubation mixture and quench it with an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard to stop the reaction.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched samples to precipitate proteins. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to quantify the remaining parent drug.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the percent parent remaining versus time. The slope of the linear regression is the apparent first-order elimination rate constant (k), from which the in vitro half-life (t1/2 = 0.693/k) and intrinsic clearance (CLint = k / microsomal protein concentration) can be calculated.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Diagram 1: Pathways for Oral Drug Absorption and Key Barriers

Title: Oral drug absorption pathway and key barriers limiting bioavailability.

Diagram 2: Strategic Solutions to Overcome Bioavailability Barriers

Title: Formulation and prodrug strategies to overcome bioavailability barriers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability Assessment | Caco-2 Cell Lines | In vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium for predicting drug absorption and efflux. [34] | Requires long culture time (21 days) to fully differentiate. |

| PAMPA Plates & Lipid Membranes | High-throughput tool for screening passive permeability potential. [34] [35] | Does not account for active transport or efflux mechanisms. | |

| Solubility & Dissolution | Biorelevant Media (FaSSIF/FeSSIF) | Simulates the composition and surface activity of fasted and fed state intestinal fluids for realistic solubility measurements. [34] | More predictive than simple aqueous buffers. |

| USP Dissolution Apparatus | Standardized equipment for measuring the rate and extent of drug release from a dosage form. [30] | Critical for quality control and formulation development. | |

| Metabolic Stability | Liver Microsomes & Hepatocytes | Subcellular fraction or whole cells containing metabolic enzymes (CYPs, UGTs) for in vitro stability and clearance studies. [34] | Cryopreserved hepatocytes offer a more complete metabolic profile than microsomes. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Provides essential cofactors for Cytochrome P450 enzyme activity in microsomal incubations. [34] | Essential for initiating and maintaining metabolic reactions. | |

| Prodrug Synthesis | Activated Promoieties (e.g., acyl chlorides, phosphorochloridates) | Chemically reactive compounds used to attach lipophilic or hydrophilic groups to a parent drug molecule. [3] [32] | Requires careful selection to ensure efficient in vivo cleavage. |

| Formulation Enablers | Lipid Excipients (e.g., Medium Chain Triglycerides) | Key components of lipid-based drug delivery systems that enhance solubilization and lymphatic transport. [33] [34] | Compatibility with capsules (e.g., gelatin) must be checked. |

| Polymers for Amorphous Solid Dispersions (e.g., HPMC, PVP) | Inhibit drug recrystallization and maintain supersaturation in the GI tract to drive absorption. [34] | Drug-polymer miscibility is critical for physical stability. |

A critical challenge in modern drug development is overcoming poor cellular permeability, which can render otherwise potent therapeutic compounds ineffective. For drugs targeting intracellular pathways, such as those used against viruses and cancers, the ability to cross cell membranes is non-negotiable. The prodrug strategy has emerged as a powerful solution to this problem, wherein a biologically inactive derivative of a drug undergoes enzymatic or chemical transformation within the body to release the active parent compound [12] [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for optimizing biopharmaceutical and pharmacokinetic parameters while mitigating adverse effects [12].

Statistical evidence underscores the importance of this strategy: approximately 13% of drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2012 and 2022 were prodrugs [12]. A recent analysis identified around 95 distinct design goals for prodrugs, with approximately 59% aimed at enhancing bioavailability, primarily through improvements in permeability (35%) and solubility (15%) [12]. This case study examines how permeability-driven design principles are applied to develop effective antiviral and anticancer prodrugs, providing a technical framework for researchers in the field.

Theoretical Foundations: Membrane Permeability and the Prodrug Approach

Mechanisms of Membrane Permeability

For small molecule drugs to reach intracellular targets, they must traverse biological membranes through one of two primary mechanisms:

Passive Transport: This energy-independent process occurs through diffusion, driven by a concentration gradient. Key molecular properties influencing passive diffusion include [12]:

- Polarity: Lower polarity generally enhances permeability.

- Molecular Weight: Smaller molecules diffuse more readily.

- Lipophilicity: Higher lipophilicity (within optimal limits) improves membrane partitioning.

Active Transport: This energy-dependent process is facilitated by specific transporter proteins (e.g., ATP-binding cassette transporters) that utilize energy (such as ATP hydrolysis) to move compounds across membranes [12]. Unlike passive diffusion, active transport can exhibit saturation kinetics due to the finite number of available transporter proteins [12].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS)

The BCS provides a valuable framework for categorizing drugs based on their solubility and permeability characteristics [12]. Understanding a drug's BCS class is fundamental to identifying the need for a prodrug strategy.

Table 1: Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) and Drug Examples

| Class | Solubility | Permeability | Examples of Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | High | High | Acyclovir, Captopril, Abacavir |

| II | Low | High | Atorvastatin, Diclofenac, Ciprofloxacin |

| III | High | Low | Cimetidine, Atenolol, Amoxicillin |

| IV | Low | Low | Furosemide, Chlorthalidone, Methotrexate |

Adapted from [12]

Prodrug strategies are particularly beneficial for BCS Class III (high solubility, low permeability) and Class IV (low solubility, low permeability) compounds, aiming to transition them toward a more favorable Class I profile.

The Role of Efflux Transporters

A significant barrier to drug permeability, especially in specialized tissues like the blood-brain barrier and in cancer cells, is the overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporters. Key players include [36] [37] [38]:

- P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1): A broad-spectrum efflux pump that significantly limits the intracellular accumulation and tissue penetration of many anticancer and antiviral drugs [37] [39].

- Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2): Another major efflux transporter with overlapping substrate specificity to P-gp, contributing to multidrug resistance [36] [40].

- Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1): Transports a range of conjugated anions and chemotherapeutic agents [36].

Prodrug design can incorporate structural features that avoid recognition by these efflux pumps, thereby improving intracellular drug concentrations.

Figure 1: Logic Flow of Permeability-Driven Prodrug Design. This diagram outlines the strategic approach to overcoming poor drug permeability through prodrug engineering.

Antiviral Prodrug Case Studies

Remdesivir: A Multi-Stage Prodrug for Enhanced Cellular Uptake

Remdesivir is a broad-spectrum antiviral nucleotide analog that exemplifies sophisticated prodrug design to overcome the significant permeability challenges associated with charged nucleotide analogs [41].

- Mechanism of Action: The active form of Remdesivir, a triphosphate nucleoside analog, inhibits viral RNA polymerase. However, the polar phosphate groups prevent efficient cellular uptake.

- Prodrug Strategy: Remdesivir is administered as a phosphoramidate prodrug. This design masks the charged phosphate groups with lipophilic aromatic substituents and amino acid esters, dramatically increasing its lipophilicity and membrane permeability [41].

- Activation Pathway: Intracellular activation is a multi-step process involving ester cleavage followed by spontaneous cyclization and hydrolysis to release the nucleoside monophosphate, which is subsequently phosphorylated to the active triphosphate form.

Table 2: Key Properties and Design Features of Antiviral Prodrugs

| Prodrug Name | Active Drug | Primary Permeability Challenge | Prodrug Strategy | Enzymes Involved in Activation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remdesivir | Nucleoside Triphosphate | High polarity of phosphate groups | Phosphoramidate derivatization | Esterases, Carboxylesterases (CES) [41] |

| Favipiravir | Ribofuranosyltriphosphate | Low membrane permeability | Administered as a ribonucleoside prodrug | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) [41] |

| Valacyclovir | Acyclovir | Low oral bioavailability (20%) | L-valyl esterification | Enzyme: Valacyclovirase (Branched-chain amino acid transferase) [12] |

| AZT (Zidovudine) | AZT-monophosphate | Efflux by P-gp and ABCG2 | Dimerization to create transporter inhibitors [40] | N/A (Used to inhibit efflux, not as a prodrug) |

AZT Dimer Inhibitors: Blocking Efflux to Enhance Permeability

While not a prodrug itself, the modification of Azidothymidine (AZT) illustrates a creative approach to overcoming transporter-mediated permeability barriers. AZT, an antiretroviral, is a substrate for both P-gp and ABCG2 efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier, limiting its CNS penetration [40].

- Design Strategy: Researchers synthesized a series of AZT homodimers linked by methylene chains of varying lengths [40].

- Mechanism: These dimers do not function as conventional prodrugs. Instead, they act as dual inhibitors of P-gp and ABCG2. By simultaneously blocking both major efflux transporters, they increase the brain penetration of co-administered AZT and other antiretroviral therapeutics [40].

- Key Finding: Dimer potency was found to be dependent on the tether length, with longer linkers (e.g., AZT-C12) showing superior inhibitory activity against both transporters [40].

Anticancer Prodrug Case Studies

Capecitabine: Tumor-Selective Activation and Permeability

Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate prodrug that showcases the application of permeability design for both enhanced absorption and targeted activation [16].

- Mechanism of Action: The active drug, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), is a pyrimidine analog with antineoplastic activity. However, 5-FU itself has variable oral absorption and significant toxicity.

- Prodrug Strategy: Capecitabine is designed with high oral bioavailability. Its lipophilic nature allows for efficient passive absorption from the gastrointestinal tract [16].

- Activation Pathway: Activation is a three-enzyme, tumor-selective process:

- Liver: Carboxylesterase (CES) hydrolyzes capecitabine to 5'-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine (5'-DFCR).

- Liver and Tumors: Cytidine deaminase converts 5'-DFCR to 5'-deoxy-5-fluorouridine (5'-DFUR).

- Tumors: Thymidine phosphorylase (dThdPase), an enzyme often highly concentrated in tumor tissues, converts 5'-DFUR to the active 5-FU. This selective activation maximizes efficacy in the tumor while minimizing systemic exposure [16].

Taxanes and Overcoming ABCB1-Mediated Resistance

Taxanes like docetaxel (DTX) and cabazitaxel (CBZ) are cornerstone treatments for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). A major mechanism of resistance is the overexpression of the ABCB1 (P-gp) efflux transporter, which actively pumps taxanes out of cancer cells [39].

- The Problem: Acquired resistance in CRPC cell lines (e.g., RC4-2B) is strongly linked to increased ABCB1 expression, conferring cross-resistance to both DTX and CBZ [39].

- Experimental Solution: Research demonstrates that this resistance can be overcome by:

- Using Specific ABCB1 Inhibitors: Elacridar, a potent ABCB1 inhibitor, can reverse taxane resistance in vitro, confirming the transporter's role [39].

- Switching to Non-Substrate Chemotherapeutics: DNA-damaging agents like Camptothecin (CPT) and Cytarabine (Ara-C) were found to be equally cytotoxic against both parental and ABCB1-overexpressing resistant cells, as they are not effluxed by ABCB1 [39]. This provides a viable treatment strategy for taxane-resistant CRPC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Prodrug Permeability Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Purpose | Key Application in Prodrug Research |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Model | In vitro model of human intestinal permeability | Predicts oral absorption potential of prodrug candidates [12]. |

| MDCK or MDCK-II Cells | Canine kidney epithelial cells; often transfected with human transporters (e.g., MDR1-MDCKII) | Specifically assesses interaction with and efflux by P-gp and other ABC transporters [12]. |

| P-gp/ABCB1 Inhibitors(e.g., Elacridar, Verapamil, Zosuquidar) | Pharmacologically block P-gp efflux activity | Used to confirm P-gp-mediated efflux of a parent drug and to validate that a prodrug evades this transporter [39]. |

| Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA) | High-throughput measure of passive transmembrane diffusion | Screens prodrug libraries for improved passive permeability independent of active transporters [12]. |

| Carboxylesterases (CES)(e.g., from porcine liver) | Hydrolyze ester and amide-based prodrugs | In vitro evaluation of enzymatic conversion rates for ester-based prodrugs like capecitabine [16]. |

| ATPase Assay | Measures ATP hydrolysis by ABC transporters | Determines if a prodrug candidate is a substrate or inhibitor of transporters like P-gp [38]. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Permeability in MDR1-MDCKII Cell Monolayers

Purpose: To evaluate whether a prodrug is a substrate for the human P-gp efflux transporter [12].

Method:

- Cell Culture: Grow MDR1-MDCKII cells on transparent filter supports until they form a confluent, polarized monolayer with tight junctions.

- Transport Experiment: Add the prodrug candidate to either the apical (A) or basolateral (B) compartment in a suitable buffer (e.g., HBSS).

- Perform bidirectional transport: A→B and B→A.

- Include a control group with a known P-gp inhibitor (e.g., 10 µM Elacridar).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate at 37°C with gentle shaking. Collect samples from the receiver compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 min) and analyze drug concentration using HPLC or LC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Apparent Permeability Coefficient (Papp) for each direction.

- Determine the Efflux Ratio: ER = Papp (B→A) / Papp (A→B).

- Interpretation: An ER ≥ 2 that is significantly reduced (e.g., by ≥50%) in the presence of a P-gp inhibitor suggests the compound is a P-gp substrate.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Prodrug Activation Kinetics

Purpose: To quantify the rate of conversion of a prodrug to its active parent molecule by specific enzymes [16].

Method:

- Incubation Setup: Prepare incubation mixtures containing the prodrug, appropriate enzyme source (e.g., liver microsomes, recombinant esterases, or target cell lysates), and buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4).

- Time Course Experiment: Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme source and incubate at 37°C. Aliquot samples at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min).

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction immediately by adding an equal volume of an organic solvent like acetonitrile (which also precipitates proteins).

- Analysis: Centrifuge the samples and analyze the supernatant using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV) to quantify the disappearance of the prodrug and the appearance of the active drug.

- Data Analysis: Plot the concentration of the active drug over time and calculate the activation velocity (e.g., pmol/min/mg protein) and half-life of conversion.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs