Strategic ADME Optimization in Lead Optimization: Accelerating Candidate Selection with Integrated Approaches

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ADME optimization in modern lead optimization, addressing the critical need to reduce late-stage attrition in drug development.

Strategic ADME Optimization in Lead Optimization: Accelerating Candidate Selection with Integrated Approaches

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ADME optimization in modern lead optimization, addressing the critical need to reduce late-stage attrition in drug development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME), details cutting-edge in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methodologies, offers troubleshooting strategies for complex modalities like peptides and PROTACs, and validates integrated approaches that improve human translation. By synthesizing the latest advancements in AI-driven prediction, organ-on-a-chip technology, and strategic model integration, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design more efficient and predictive ADME profiling workflows.

Understanding ADME Fundamentals: The Cornerstone of Successful Lead Optimization

Why ADME Properties are a Major Cause of Drug Attrition

Drug discovery and development is a lengthy, costly, and risky process, with estimates indicating that advancing a single drug candidate to market requires an average of 10-15 years, investments exceeding USD 1 billion, and failure rates exceeding 90% across all clinical phases [1] [2]. Within this high-attrition landscape, undesirable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties constitute a fundamental cause of failure for new molecular entities [3]. Historically, approximately 40% of all drug failures were directly attributable to ADME problems, prompting a paradigm shift toward earlier evaluation of these critical properties [4]. While this shift has reduced pharmacokinetic-related failures, ADME issues remain a significant contributor to candidate attrition, particularly when intertwined with toxicity concerns [3] [5].

The pharmaceutical industry has widely adopted the "fail early, fail cheap" strategy, recognizing that early assessment of ADME parameters during lead selection and optimization is crucial for identifying compounds with sufficient pharmacokinetic profiles to become viable efficacious drugs [6] [4]. This application note examines the quantitative impact of ADME properties on drug attrition, provides structured experimental protocols for key ADME assessments, and introduces advanced computational tools that are reshaping predictive strategies in modern drug development pipelines.

Quantitative Analysis of ADME-Related Attrition

Property Ranges and Attrition Risks

Table 1: Physicochemical Property Ranges Associated with Reduced Attrition Risk

| Property | Optimal Range | Attrition Risk When Suboptimal | Primary Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ≤500 g/mol | Increased permeability issues | Absorption, Distribution |

| logP (lipophilicity) | ≤5 | Poor solubility or excessive metabolism | Absorption, Metabolism |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors | ≤5 | Reduced membrane permeability | Absorption |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors | ≤10 | Reduced membrane permeability | Absorption |

| Polar Surface Area | <140 Ų | Compromised blood-brain barrier penetration | Distribution |

| Rotatable Bonds | ≤10 | Reduced oral bioavailability | Absorption |

General property rules for drugs may poorly reflect the subtle ADME differences required by indication-specific drug classes [1] [2]. For example, central nervous system (CNS) drugs generally exhibit more extreme profiles—being smaller, less polar, and more lipophilic—than non-CNS drugs to achieve adequate blood-brain barrier penetration [1].

Therapeutic Area Variability in ADME Profiles

Table 2: ADME Property Variability Across Major Therapeutic Classes (ATC Classification)

| ATC Class | Representative Drugs | Key ADME Characteristics | Attrition Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (Nervous System) | 452 drugs | Lower MW, reduced PSA, increased lipophilicity | Narrow therapeutic windows, CNS toxicity |

| C (Cardiovascular) | 323 drugs | Moderate MW, balanced lipophilicity | Drug-drug interactions, variable clearance |

| J (Anti-infectives) | 298 drugs | Higher MW, complex structures | Tissue penetration challenges, metabolism issues |

| L (Antineoplastic) | 268 drugs | Wider property ranges | Complex toxicity profiles, narrow therapeutic index |

Analysis of marketed drugs across anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classes reveals significant differences in property value distributions, highlighting the need for indication-specific ADME optimization strategies rather than universal property rules [1] [2].

Experimental Protocols for ADME Assessment

Protocol 1: Metabolic Stability Assessment Using Liver Microsomes

Purpose: To evaluate the metabolic stability of drug candidates using liver microsomes and predict in vivo clearance through in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) [6] [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test compound (10 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- Pooled species-specific liver microsomes (human/rat/mouse)

- NADPH-regenerating system

- Potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Methanol and acetonitrile (LC-MS grade)

- LC-MS/MS system with appropriate analytical column

Procedure:

- Prepare incubation mixture containing 0.5 mg/mL liver microsomes in potassium phosphate buffer

- Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C with gentle shaking

- Initiate reaction by adding NADPH-regenerating system

- Aliquot samples at predetermined time points (0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes)

- Terminate reactions with ice-cold acetonitrile containing internal standard

- Centrifuge at high speed to remove precipitated proteins

- Analyze supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine parent compound concentration

- Calculate half-life (t₁/₂) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) using first-order kinetics

Data Interpretation: Compounds with hepatic clearance >70% of liver blood flow are considered high-clearance, while those <30% are classified as low-clearance [6]. High clearance often correlates with poor oral bioavailability and increased attrition risk.

Protocol 2: Caco-2 Permeability and Efflux Assessment

Purpose: To predict human intestinal absorption and identify substrates for efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein [4] [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Caco-2 cell line (passage 25-45)

- DMEM culture medium with supplements

- Transport buffer (HBSS-HEPES, pH 7.4)

- Test compound (100 μM)

- Lucifer yellow (integrity marker)

- LC-MS/MS system for quantification

Procedure:

- Culture Caco-2 cells on collagen-coated Transwell inserts for 21 days

- Validate monolayer integrity by measuring TEER (>300 Ω·cm²) and lucifer yellow flux

- Add test compound to donor compartment (apical for A→B, basolateral for B→A)

- Sample from receiver compartment at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes

- Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to determine compound concentration

- Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio (ER)

Data Interpretation: Papp (A→B) >10×10⁻⁶ cm/s indicates high permeability, while ER >2 suggests active efflux potentially limiting absorption [4]. High efflux ratios often predict food effects, drug-drug interactions, and variable exposure in humans.

Protocol 3: Plasma Protein Binding Determination

Purpose: To quantify the fraction of drug bound to plasma proteins, which influences volume of distribution, clearance, and free drug concentration [6] [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test compound

- Human or species-specific plasma

- Equilibrium dialysis device

- Dialysis membrane (12-14 kDa MWCO)

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Procedure:

- Add test compound to plasma side at therapeutically relevant concentration

- Assemble dialysis device with buffer on opposite side of membrane

- Incubate at 37°C for 4-6 hours with gentle rotation

- Sample from both plasma and buffer compartments

- Precipitate proteins in plasma samples with acetonitrile

- Analyze both sets of samples using LC-MS/MS

- Calculate fraction unbound (fu) and fraction bound (fb)

Data Interpretation: Compounds with >95% protein binding are considered highly bound, which can lead to variable free drug concentrations, altered pharmacokinetics, and potential drug-drug interactions through protein binding displacement [6].

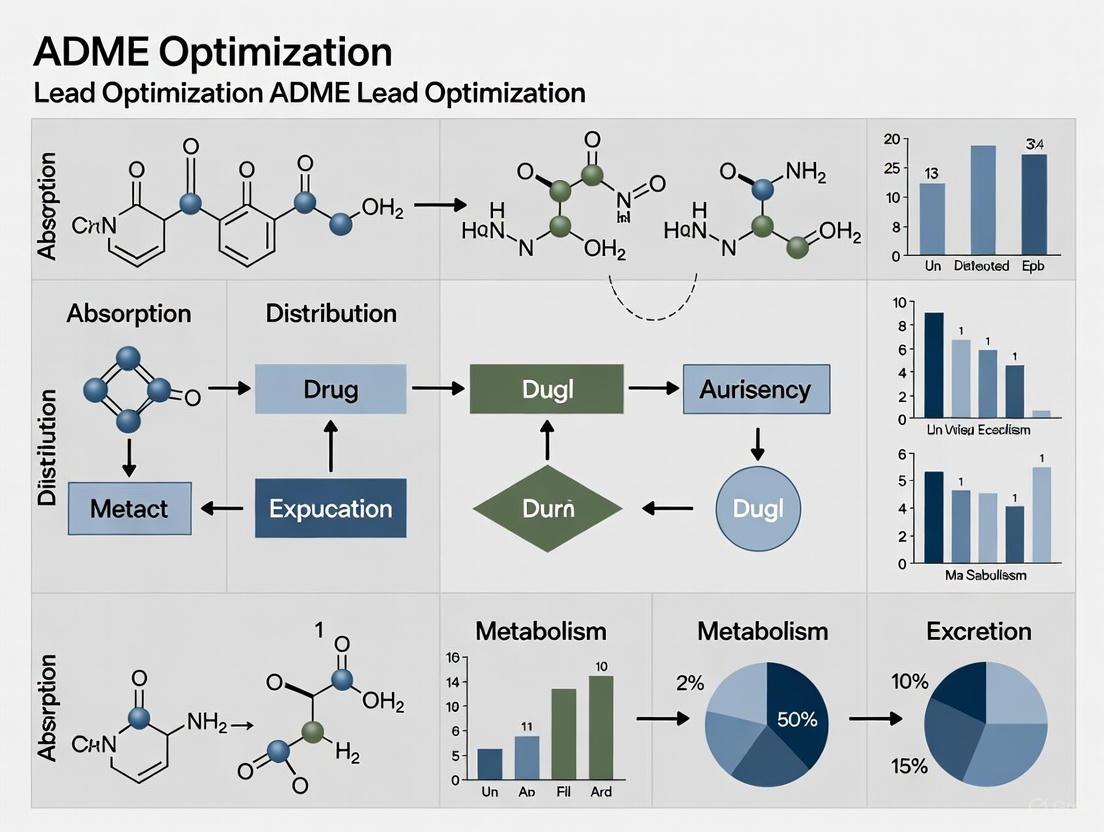

Visualization of ADME Assessment Workflows

Integrated ADME Screening Cascade

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADME Profiling

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in ADME Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Liver Microsomes | Metabolic enzyme source | Intrinsic clearance determination, metabolite identification |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Intestinal epithelium model | Permeability screening, efflux transporter assessment |

| Transfected Cell Lines | Specific transporter expression | Uptake/efflux transporter interaction studies |

| Human Hepatocytes | Integrated hepatic model | Phase I/II metabolism, enzyme induction potential |

| Equilibrium Dialysis Device | Binding measurement apparatus | Plasma protein binding determination |

| Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) | Ultra-sensitive detection | Human radiolabeled ADME studies, microdosing |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Physiological simulation | Human pharmacokinetic prediction, DDI risk assessment |

| SwissADME Web Tool | Free in silico screening | Rapid physicochemical and PK property estimation [8] |

Advanced tools like machine learning platforms and PBPK modeling software are increasingly integrated into ADME assessment workflows. These tools leverage large datasets of historical ADME properties to build predictive models that can guide chemical design and prioritize compounds for experimental testing [5] [9]. The SwissADME web tool provides free access to robust predictive models for physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness, enabling researchers to rapidly evaluate key parameters for compound collections [8].

ADME properties remain a major cause of drug attrition due to their fundamental influence on drug exposure, target engagement, and ultimately therapeutic efficacy. The strategic integration of robust ADME assessment protocols—spanning in silico predictions, high-throughput in vitro assays, and targeted in vivo studies—into early discovery phases enables identification and mitigation of pharmacokinetic liabilities before costly late-stage development. The continuing evolution of computational approaches, particularly machine learning and AI-driven ADMET prediction platforms, promises to further transform this landscape by enhancing predictive accuracy and enabling more informed compound selection [5] [9]. By adopting these comprehensive assessment strategies and leveraging the specialized research tools outlined in this application note, drug development teams can significantly reduce attrition rates and advance candidates with optimized ADME profiles toward clinical success.

The optimization of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) properties represents a critical hurdle in modern drug discovery. The high-throughput screening of these properties has become the norm in the industry, largely to address historical trends where ADME issues contributed to more drug failures than efficacy or safety concerns in clinical trials [10]. At the heart of ADME optimization lie three fundamental physicochemical properties: lipophilicity (commonly measured as Log D), solubility, and permeability. These properties are deeply interconnected and form the basis for understanding a compound's pharmacological and pharmacokinetic fate after administration [11].

These core properties govern the drug's ability to be absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, distribute to target tissues, and be metabolized and eliminated appropriately. With the realization of new techniques and refinement of existing ones, better projections for the pharmacokinetic properties of compounds in humans are now possible, shifting drug failure attributes more toward safety and efficacy properties [10]. The strategic assessment of these properties during lead optimization enables discovery teams to track project progress efficiently and provides a rationale for the types of studies needed at various stages of discovery [10]. This application note provides detailed protocols and benchmarks to guide researchers in the systematic evaluation of these essential properties.

Property Definitions and Strategic Significance

Lipophilicity (Log D) is the distribution coefficient of a compound between octanol and buffer at a specific pH, typically pH 7.4, accounting for both ionized and non-ionized forms [12] [13]. This parameter plays a crucial role in solubility, absorption, membrane penetration, plasma protein binding, distribution, and CYP450 interactions [13]. Aqueous solubility refers to the concentration of a dissolved compound in equilibrium with its solid form, which directly impacts bioavailability and absorption from the gastrointestinal tract [12] [13]. Permeability describes a compound's ability to cross biological membranes, a critical determinant for oral absorption and tissue distribution, often predicted through models like Caco-2, PAMPA, or computational descriptors [14] [15].

The interrelationship between these properties forms what is often described as the "Balance of Properties" in drug design. Lipophilicity directly influences both solubility and permeability—higher lipophilicity generally decreases aqueous solubility while increasing membrane permeability [12]. This inverse relationship creates a fundamental challenge in optimization, as improving one property often comes at the expense of another. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for effective lead optimization, requiring researchers to navigate a multi-parameter optimization space rather than focusing on individual properties in isolation.

Table 1: Optimal Ranges and Critical Benchmarks for Core Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Optimal Range | Strategic Significance | Key Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log D at pH 7.4 | 0-3 [12] | Best balance of solubility and permeability [12] | >5: Poor solubility, promiscuous binding, strong CYP450 interaction [12]; <0: Good solubility but poor permeability [12] |

| Aqueous Solubility | >50 μM (approximate guideline) | Ensures adequate dissolution for absorption [13] | Limits absorption from GI tract; affects reliability of other ADME assays [13] |

| Permeability (Caco-2 Papp) | >5 × 10⁻⁶ cm/s (high) | Indicator of good intestinal absorption [14] | Low permeability limits oral bioavailability; may require active transport [14] |

| Molecular Weight | ≤950 Da (for PROTACs) [15] | Impacts passive diffusion and solubility | Higher MW generally decreases absorption and permeability [15] |

| H-Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤3 (for PROTACs) [15] | Critical for membrane penetration | Increased HBD count typically reduces permeability [15] |

Visualizing the Interconnected Nature of ADME Properties

The following diagram illustrates how the three core physicochemical properties interrelate and collectively influence critical ADME outcomes:

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Lipophilicity (Log D) Measurement via Shake-Flask Method

The shake-flask method remains the gold standard for lipophilicity assessment, providing a direct measurement of distribution between octanol and aqueous phases [13].

Protocol Summary:

- Test Articles: Assayed in triplicate at a single concentration (typically 10 μM) [13]

- Partition Solvent: n-Octanol with buffer (typically phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) in a 1:1 ratio [13]

- Controls: Testosterone (high log D₇.₄ positive control), Tolbutamide (low log D₇.₄ negative control) [13]

- Procedure: Compound is dissolved in a solution with equal amounts of octanol and buffer, shaken for 3 hours, and then measured for the amount of compound in each phase [13]

- Analysis: LC/MS/MS measurement of parent compound in both phases [13]

- Calculation: Log D = log([compound]ₒcₜₐₙₒₗ / [compound]բᵤfғₑᵣ) [13]

- Compound Requirement: 1.0-2.0 mg [13]

Methodological Considerations: Recent advancements have improved the accuracy of Log D determination. A validation study demonstrated excellent correlation between automated and manual methods with the equation: Log DADW = 0.002(±0.008) + 1.011(±0.005)×Log Dmanual (N=179; r²=0.9960; standard error of estimate=0.1022) [12]. For ionizable compounds like propranolol, the use of universal buffer composed of acetic, phosphoric, and boric acids with NaOH helps maintain consistent pH conditions [12].

Thermodynamic Solubility Determination

Solubility assessment must distinguish between kinetic (apparent) and thermodynamic (equilibrium) solubility, with the latter being more predictive for in vivo performance.

Protocol Summary:

- Test Articles: Assayed in duplicate at a single concentration (typically 1 μM) [13]

- Buffer Systems: Phosphate buffered solution across a three-point pH range (5.0, 6.2, 7.4) to simulate gastrointestinal variation [13]

- Controls: Diclofenac (high solubility positive control), Dipyridamole (low solubility negative control) [13]

- Procedure: Compound is dissolved in buffer solutions at indicated pH values and allowed to reach thermodynamic equilibrium by incubating for 18 hours [13]

- Analysis: UV spectrophotometry measurement compared to fully saturated solution in 1-propanol [13]

- Compound Requirement: 1.0-2.0 mg [13]

Critical Considerations: The definition of solubility as "concentration of a dissolved compound in equilibrium with its solid" requires careful attention to multiple factors: the specific solid form (most stable vs. other forms), the solvent system (buffers vs. co-solvents), and equilibrium conditions (time and temperature) [12]. Solid particles are an integral part of the solubility assay and must be present for turbidity-based methods, though they represent artifacts in absorbance/elemental assays [12]. Identification of saturated solutions can be challenging, as visual inspection alone may be insufficient to distinguish between true saturation and suspension [12].

Permeability Assessment Using Caco-2 Transwell Assay

The Caco-2 cell model remains a cornerstone for in vitro permeability assessment, though method adaptations may be necessary for challenging compound classes.

Protocol Summary:

- Cell Culture: Caco-2 cells (TC7 clone) seeded at 125,000 cells per well in 24-well transwell plates and cultured for 14-21 days to form differentiated monolayers [15]

- Experimental Setup: Apparent permeability (Pₐₚₚ) determined from apical-to-basolateral (Pₐₚₚ,ₐբ) and basolateral-to-apical (Pₐₚₚ,բₐ) directions [15]

- Volumes: Apical compartment: 250 μL, basolateral compartment: 750 μL [15]

- Incubation: 2 hours at 37°C in 5% CO₂ and 100% humidity [15]

- Analysis: Samples from both compartments at t=0 and after 2 hours analyzed via UHPLC-MS/MS [15]

- Quality Control: Monolayer tightness controlled using melagatran as tightness marker [15]

Calculation Parameters:

- Apparent Permeability: Pₐₚₚ = (Δcᵣₑc/Δt × Vᵣₑc) / (c𝒹ₒₙ,₀ × A) where Δcᵣₑc/Δt is concentration change in receiver compartment over time, Vᵣₑc is receiver volume, c𝒹ₒₙ,₀ is initial donor concentration, and A is membrane surface area (0.33 cm²) [15]

- Mass Balance: Recovery = (amountᵣₑc,₂ₕ + amount𝒹ₒₙ,₂ₕ) / amount𝒹ₒₙ,₀ [15]

- Efflux Ratio: ER = Pₐₚₚ,բₐ / Pₐₚₚ,ₐբ [15]

- Passive Permeability: Geometric mean of Pₐₚₚ,ₐբ and Pₐₚₚ,բₐ used as Pₐₚₚ,ₚₐₛₛ [15]

Method Adaptation for Challenging Compounds: For problematic chemical classes such as PROTACs, several assay modifications have been explored:

- Serum Addition: HBSS buffer containing 10% FCS on both sides to reduce unspecific binding [15]

- pH Adjustment: Apical compartments adjusted to pH 6.5 instead of pH 7.4 to simulate intestinal conditions [15]

- Biorelevant Media: FaSSIF (Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid) as apical buffer instead of HBSS [15]

- Mucin Layer: Addition of 50 mg/mL mucin on top of Caco-2 cells to simulate mucus barrier [15]

Advanced Applications and Specialized Approaches

Beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) Space Considerations

Emerging modalities like Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) present unique challenges as they reside in the beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) space with high molecular weight and lipophilicity [15]. For these compounds, standard small molecule methodologies may require adaptation, and surrogate permeability descriptors become increasingly valuable [15].

Table 2: Recommended Property Space for Oral PROTACs and Optimization Strategies

| Parameter | Recommended Boundary | Rationale | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ≤950 Da [15] | Impacts passive diffusion and solubility | Higher MW generally decreases absorption; synthesis feasibility |

| H-Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤3 [15] | Critical for membrane penetration | Reduced HBD count typically enhances permeability; shielding exposed HBDs is powerful optimization approach [15] |

| Rotatable Bonds | ≤12 [15] | Affects molecular flexibility | Lower count associated with improved permeability |

| Chromlog D | ≤7 [15] | Balance of solubility and permeability | High lipophilicity increases promiscuous binding and metabolic instability |

| Exposed Polar Surface Area (ePSA) | ≤170 Ų [15] | Surrogate for permeability assessment | Reduction through HBD shielding improves membrane penetration [15] |

Research indicates that for bRo5 compounds, the reduction of exposed polar surface area, particularly through shielding of hydrogen bond donors, represents a powerful approach to optimize permeability [15]. Additionally, standard small molecule-based methods for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) of intrinsic clearance may systematically underpredict for PROTACs when using predicted fraction unbound in incubation (fᵤ,ᵢₙc), highlighting the need for experimentally determined values [15].

In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation and Prediction Tools

The transition from in vitro data to predicted in vivo consequences represents a critical paradigm shift in ADME optimization [16]. Rather than discussing raw assay data, forward-looking approaches focus on potential clinical problems that may surface during development, using suitable variables derived from assay data [16].

Computational Prediction Platforms: Several software platforms provide robust in silico prediction of ADME properties:

- ADMET Predictor PCB Module: Includes models for physicochemical property prediction using artificial neural network ensemble (ANNE) technology, including S+logP (ranked #1 in peer-reviewed comparisons), S+logD, multiprotic pKa, and various solubility predictions [17]

- ACD/ADME Suite: Provides structure-based calculations of pharmacokinetic properties including blood-brain barrier penetration, cytochrome P450 inhibition and substrate specificity, distribution, oral bioavailability, and passive absorption [14]

- BioSolveIT/Optibrium Platforms: Feature calculation of relevant ADME parameters including CYP2C9 pKi, CYP2D6 affinity, blood-brain barrier classification, HIA category, P-gp category, logD, logP, and logS [18]

These tools enable researchers to prioritize synthesis and experimental testing, conserving resources by filtering out compounds with unfavorable predicted parameters early in the design process [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Systems for ADME Profiling

| Tool/Reagent | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol/Buffer Systems | Gold standard for Log D determination via shake-flask method [13] | Use universal buffer for ionizable compounds; maintain strict pH control [12] |

| Caco-2 Cell Line (TC7 clone) | In vitro model of intestinal permeability [15] | Requires 14-21 day differentiation; monitor tightness with reference compounds like melagatran [15] |

| Pooled Human Liver Microsomes | Metabolic stability assessment [13] | Batch-to-batch variability; use same lot for comparable results with bridging studies [13] |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluids (FaSSIF/FeSSIF) | Biorelevant solubility measurement [17] | Better predicts in vivo performance compared to simple aqueous buffers [17] |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Intrinsic clearance determination [15] | Maintain viability >70%; use species relevant to in vivo models [15] |

| Transwell Assay Systems | Permeability assessment with liquid handling automation [15] | Enable high-throughput screening; include mass balance calculations [15] |

Workflow Integration and Strategic Implementation

The following diagram outlines a recommended integrated workflow for the strategic implementation of these assays in lead optimization:

This workflow emphasizes the sequential yet interconnected nature of ADME screening, where compounds progress through a tiered testing cascade. Implementation of such systematic approaches follows the Discovery Assay by Stage (DABS) paradigm, which provides teams with rationale for study types during hit-to-lead, early and late lead optimization stages of discovery [10]. This framework has proven optimal for efficient resource utilization and helps discovery teams track compound and project progress systematically [10].

The systematic assessment of lipophilicity, solubility, and permeability represents a cornerstone of modern ADME optimization in drug discovery. Through the implementation of robust, well-characterized protocols for these fundamental properties—coupled with appropriate data interpretation and strategic decision-making—research teams can significantly de-risk the lead optimization process. The integration of experimental data with predictive computational models creates a powerful framework for compound design and selection, ultimately increasing the probability of identifying development candidates with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles. As the field continues to evolve with new modalities and technologies, these core principles remain essential for efficient navigation of the complex multi-parameter optimization space that defines successful drug discovery.

Within the context of a broader thesis on ADME optimization in lead optimization research, this document details the critical in vitro and in silico methodologies for profiling three fundamental parameters: metabolic stability, plasma protein binding, and clearance. The early and accurate assessment of these properties is crucial for streamlining drug development, as deficiencies in these areas are primary causes of failure in later-stage clinical trials [19] [20]. This guide provides detailed application notes and protocols to enable researchers to effectively integrate these assessments into the lead optimization cycle, supporting the design of candidates with a higher probability of success.

Core ADME Parameters: Significance and Experimental Assessment

The following section outlines the key parameters, their impact on the drug discovery process, and the standard experimental protocols used for their determination.

Metabolic Stability

Significance: Metabolic stability refers to the susceptibility of a compound to enzymatic modification, primarily by hepatic enzymes. It directly impacts a drug's half-life and oral bioavailability. A compound with low metabolic stability is rapidly cleared, which may necessitate frequent dosing to maintain therapeutic exposure [21] [22]. During lead optimization, the goal is to identify metabolically soft spots to guide structural modifications that improve stability without compromising potency.

Experimental Protocol: Intrinsic Clearance (CL~int~) Assay using Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) or Hepatocytes

- Principle: This assay measures the depletion of the test compound over time when incubated with metabolically active systems (HLM or suspended hepatocytes) to estimate its intrinsic metabolic clearance [21].

- Materials:

- Test compound (typically 1 µM final concentration)

- Pooled Human Liver Microsomes (0.5 mg/mL protein) or Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes (0.5-1.0 million cells/mL)

- NADPH-regenerating system (for HLM) or appropriate nutrient medium (for hepatocytes)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4)

- Stop solution (e.g., acetonitrile with internal standard)

- Water bath or incubator shaker (37°C)

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- Procedure:

- Pre-incubation: Prepare the incubation mixture containing the liver microsomes/hepatocytes and test compound in buffer. Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the NADPH-regenerating system (for HLM) or by dispensing the hepatocyte mixture.

- Time-point Sampling: Aliquot the reaction mixture (e.g., 50 µL) at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes) into a plate containing the stop solution to precipitate proteins and terminate the reaction.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the plates to remove precipitated protein. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine the peak area ratio (compound/internal standard) at each time point.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the remaining compound percentage against time. The slope of the linear regression is the disappearance rate constant (k). CL~int~ is calculated as follows:

- For microsomes: ( CL{int} (\mu L/min/mg) = k (min^{-1}) / \text{Microsomal Protein Concentration} (mg/mL) \times 1000 )

- For hepatocytes: ( CL{int} (\mu L/min/10^6 \text{ cells}) = k (min^{-1}) / \text{Cell Concentration} (10^6 \text{ cells}/mL) \times 1000 )

Table 1: Key Assays for Metabolic Stability and Protein Binding

| Parameter | Assay System | Key Output(s) | Data Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Stability [21] | Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Intrinsic Clearance (CL~int~) | Scaling to predict human hepatic clearance. |

| Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes | Intrinsic Clearance (CL~int~) | Provides a more physiologically complete system (including non-CYP enzymes). | |

| Plasma Protein Binding [22] | Equilibrium Dialysis (ED) | Fraction Unbound (f~u~) | Considered the "gold standard" method. |

| Ultrafiltration (UF) | Fraction Unbound (f~u~) | Faster but prone to compound binding to membrane. | |

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Fraction Unbound (f~u~) | Suitable for high molecular weight or unstable compounds. |

Plasma Protein Binding

Significance: Plasma protein binding (PPB) measures the extent to which a drug binds to proteins in the blood, primarily albumin and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein. The unbound fraction (f~u~) is the pharmacologically active moiety, as only unbound drug can diffuse to its site of action or be metabolized [22]. A high degree of binding (>99%) can limit a drug's efficacy, influence its volume of distribution, and potentially lead to drug-drug interactions through protein binding displacement.

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Fraction Unbound (f~u~) by Equilibrium Dialysis

- Principle: Equilibrium dialysis separates a plasma compartment from a buffer compartment using a semi-permeable membrane. At equilibrium, the unbound drug concentration is equal in both chambers, allowing for the calculation of f~u~ [22].

- Materials:

- Test compound

- Human plasma (fresh or frozen)

- Buffer (e.g., 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Equilibrium dialysis device (e.g., 96-well format) with a molecular weight cutoff membrane (e.g., 12-14 kDa)

- Thermostated incubator (37°C)

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Spike the test compound into human plasma to achieve a therapeutic relevant concentration (e.g., 1-5 µM). Add buffer to the opposing chamber.

- Dialysis: Assemble the dialysis device and place it in an incubator at 37°C with gentle agitation for a predetermined time (typically 4-6 hours) to reach equilibrium.

- Post-dialysis Sampling: After dialysis, collect aliquots from both the plasma and buffer chambers.

- Sample Analysis: The buffer sample represents the unbound drug concentration (C~u~). The plasma sample represents the total drug concentration (C~total~). Analyze both sets of samples using LC-MS/MS. Note: For the plasma sample, a "blank" buffer should be used for dilution to match the matrix of the buffer chamber sample.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fraction unbound: ( fu = Cu / C_{total} ). The result is often expressed as a percentage: % Unbound = f~u~ × 100.

Clearance

Significance: Clearance (CL) is the volume of plasma from which a drug is completely removed per unit of time. It is a critical parameter that determines the dosing regimen and steady-state concentrations of a drug. The goal during lead optimization is to identify compounds with a clearance profile that supports the desired dosing frequency, typically low clearance for once-daily oral dosing [21].

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) of Human Hepatic Clearance

- Principle: This is a predictive approach that uses in vitro intrinsic clearance data from HLM or hepatocytes, scaled up to the whole organ level using physiological scaling factors, to predict in vivo human hepatic clearance (CL~H~) [21].

- Materials:

- Experimentally determined CL~int~ from HLM or hepatocytes (from Section 2.1 protocol)

- Scaling factors: Microsomal yield (e.g., 40 mg microsomal protein per gram liver) or Hepatocyte yield (e.g., 120 million cells per gram liver)

- Human liver weight (e.g., 20 g liver per kg body weight)

- Human hepatic blood flow (Q~H~), e.g., 20 mL/min/kg

- Procedure & Data Analysis:

- Scale-up: Convert the in vitro CL~int~ to a value representative of the whole human liver.

- For microsomes: ( CL{int, liver} (mL/min/kg) = CL{int} (\mu L/min/mg) \times \text{Liver Weight} (g \text{ liver}/kg \text{ body weight}) \times \text{Microsomal Yield} (mg \text{ protein}/g \text{ liver}) / 1000 )

- For hepatocytes: ( CL{int, liver} (mL/min/kg) = CL{int} (\mu L/min/10^6 \text{ cells}) \times \text{Liver Weight} (g \text{ liver}/kg \text{ body weight}) \times \text{Hepatocyte Yield} (10^6 \text{ cells}/g \text{ liver}) / 1000 )

- Model Application: Apply the scaled CL~int, liver~ to a physiological model of hepatic clearance, such as the "well-stirred" model, which also incorporates plasma protein binding data (f~u~) and blood-to-plasma ratio (B/P): ( CLH = \frac{ QH \times fu \times CL{int, liver} }{ QH + (fu \times CL_{int, liver}) } ) This predicted CL~H~ can be compared to known clinical values for desirable drugs to assess the viability of the lead compound.

- Scale-up: Convert the in vitro CL~int~ to a value representative of the whole human liver.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADME Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in ADME Testing |

|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) [21] | A subcellular fraction containing cytochrome P450 (CYP) and other drug-metabolizing enzymes; used for high-throughput metabolic stability and metabolite profiling. |

| Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes [21] [7] | Intact liver cells that provide a more physiologically relevant system, containing the full complement of hepatic metabolizing enzymes and transporters. |

| NADPH-Regenerating System | Provides a continuous supply of NADPH, a crucial cofactor for CYP-mediated oxidation reactions in metabolic stability assays. |

| Equilibrium Dialysis Devices [22] | The preferred platform for determining plasma protein binding, allowing for gentle separation of protein-bound and unbound drug fractions at physiological temperature. |

| LC-MS/MS System | The core analytical technology for the sensitive and specific quantification of drugs and their metabolites in complex biological matrices like plasma, buffer, and incubation mixtures. |

Integrated Workflows and Predictive Modeling in Modern ADME Science

The traditional assay-based approach is increasingly being complemented and enhanced by computational models, creating a more efficient and insightful workflow.

The Evolving Role of In Silico ADME Modeling

In silico models for ADME prediction allow for the virtual screening of compound libraries before synthesis, enabling a "fail early, fail cheap" strategy [20]. Early models based on quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) have evolved with the advent of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML). Modern graph neural networks (GNNs) that use multitask learning can simultaneously predict multiple ADME parameters, sharing information across tasks to improve performance even with limited data for any single endpoint [19]. Furthermore, these models can be made explainable, highlighting which structural features in a molecule contribute positively or negatively to a predicted ADME property, thus providing direct feedback to medicinal chemists for structural optimization [19].

Integration with Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

Data from the in vitro assays described above serve as critical inputs for PBPK modeling. PBPK models are mathematical frameworks that simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of a compound in the whole organism based on its physicochemical properties and in vitro data [7] [20]. These models are used to:

- Predict human pharmacokinetics prior to first-in-human studies.

- Assess the risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) by simulating the impact of enzyme inhibitors or inducers.

- Support regulatory submissions, as highlighted by the ICH M12 guideline on drug interaction studies [7].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated cycle of in vitro data generation, in silico modeling, and lead optimization.

Integrated ADME Optimization Workflow

The rigorous assessment of metabolic stability, plasma protein binding, and clearance is non-negotiable in modern lead optimization. By implementing the standardized experimental protocols detailed in this document and leveraging the growing power of in silico and PBPK modeling approaches, research teams can make data-driven decisions. This integrated strategy enables the systematic design of drug candidates with a higher likelihood of possessing desirable pharmacokinetic profiles, thereby reducing late-stage attrition and accelerating the development of new medicines.

The landscape of drug discovery has expanded beyond traditional small molecules to include advanced modalities such as peptides, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), and other large molecules. These modalities offer unique therapeutic advantages, including the ability to target previously "undruggable" pathways, yet they present distinct absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) challenges during lead optimization [23] [24]. Peptides bridge the gap between small molecules and biologics, offering high specificity and affinity but typically suffering from poor permeability and metabolic instability [25] [26]. PROTACs, as heterobifunctional degraders, operate catalytically to eliminate target proteins but reside in the beyond-rule-of-5 (bRo5) chemical space, creating unique optimization hurdles [23] [15]. Successfully advancing these candidates requires tailored ADME strategies that address their specific physicochemical properties and in vivo behaviors. This application note details specialized protocols and considerations for optimizing the ADME properties of peptides and PROTACs within lead optimization research programs.

Peptide Therapeutics: ADME Profiling and Optimization

Core ADME Challenges and Optimization Strategies

Natural peptides typically exhibit poor ADME properties, including rapid clearance, short half-life, low permeability, and sometimes low solubility [25]. Most have less than 1% oral bioavailability due to enzymatic degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and low permeability across cell membranes [25] [26]. Unmodified peptides also tend to have short half-lives (often minutes) resulting from extensive proteolysis and rapid renal clearance, typically limiting them to extracellular targets [25].

Table 1: Peptide ADME Challenges and Corresponding Optimization Strategies

| ADME Challenge | Impact on Pharmacokinetics | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Instability | Short in vivo half-life, requiring frequent dosing or infusion [25] | Cyclization, D-amino acid substitution, PEGylation, lipidation [26] |

| Low Permeability | Poor oral bioavailability, limiting administration routes [25] | Strategic truncation, peptidomimetics, use of permeation enhancers [27] [26] |

| Rapid Renal Clearance | Short circulation time, especially for peptides <25 kDa [26] | PEGylation to increase hydrodynamic radius, albumin binding through lipidation [26] |

| Enzymatic Degradation | Low oral bioavailability, significant first-pass metabolism [26] | N- and C-terminal capping, incorporation of unnatural amino acids [27] |

Structural modification strategies have proven effective in addressing these inherent peptide challenges. Case studies demonstrate that cyclization eliminates free N- and C-termini, protecting against exopeptidase attack as seen with Cyclosporin A [26]. Similarly, D-amino acid substitution disrupts protease recognition, enhancing metabolic stability in drugs like Leuprolide [26]. Pharmacokinetic profiles can be further refined through PEGylation, which increases hydrodynamic radius to reduce renal clearance, and lipidation (e.g., fatty acid modification) that enhances albumin binding for extended half-lives, successfully employed in Liraglutide and Semaglutide [26].

Experimental Protocols for Peptide ADME Profiling

A systematic, tiered framework for in vitro ADME profiling is crucial for guiding rational peptide design. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach used to elucidate structure-ADME relationships [26].

Protocol 1: Tiered In Vitro ADME Profiling for Peptides

Objective: To comprehensively evaluate the key ADME properties of peptide candidates and identify major liabilities during lead optimization.

Materials:

- Test Compounds: Peptide candidates (0.5-2.0 mg required per assay) [13]

- Simulated Biological Fluids: Simulated Gastric Fluid (FaSSGF) and Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FaSSIF) with and without digestive enzymes [26]

- Metabolic Matrices: Plasma (across multiple species), liver S9 fractions, intestinal S9 fractions, kidney microsomes, and lysosomes [26]

- Permeability System: Caco-2 cell monolayers, low-binding tips and plates, transport buffer with/without permeation enhancers (e.g., Sodium Caprate) [25] [26]

- Analytical Instrumentation: UHPLC-MS/MS system for quantification [26]

Procedure:

Solubility and Biorelevant Stability Assessment:

- Determine thermodynamic solubility in phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (and other relevant pH values) [13].

- Incubate peptides (typically at 1-10 µM) in FaSSGF and FaSSIF, both with and without digestive enzymes [26].

- Sample at predetermined time points and analyze by UHPLC-MS/MS to quantify remaining parent peptide.

- Data Analysis: Calculate % of parent peptide remaining over time to determine degradation half-life in each medium.

Metabolic Stability Analysis:

- Incubate peptides with various biological matrices: plasma, liver S9 fractions, intestinal S9 fractions, kidney microsomes, and lysosomes [26].

- Use a liquid handling platform for consistency. For plasma stability, incubate at 37°C and take aliquots at T0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes.

- Quench reactions with acetonitrile containing internal standard, centrifuge, and analyze supernatant via UHPLC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: Determine degradation half-life in each matrix. Note significant interspecies variability in plasma stability is common [26].

Permeability Assessment:

- Culture Caco-2 cells (TC7 clone) on transwell filters for 14-21 days to form confluent monolayers [15].

- Prior to experiment, wash monolayers with transport buffer (e.g., HBSS).

- Add peptide to donor compartment (apical for A→B, basolateral for B→A). To minimize nonspecific binding, use low-binding tips and plates, and consider adding BSA (0.5-1%) to the receiver wells [25].

- For studies with permeation enhancers, add compounds like Sodium Caprate (C10) to the apical compartment [26].

- Sample from both donor and receiver compartments at T0 and after 2 hours of incubation at 37°C [15].

- Analyze samples via UHPLC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio. Most peptides show low permeability, though effects of enhancers are compound-dependent [26].

The following workflow visualizes this multi-tiered profiling approach:

Research Reagent Solutions for Peptide ADME

Table 2: Key Reagents for Peptide ADME Assays

| Research Reagent | Function in ADME Profiling | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastric/Intestinal Fluids (FaSSGF/FaSSIF) | Assess solubility and enzymatic stability in biorelevant conditions [26] | Use both with and without digestive enzymes to differentiate chemical and enzymatic degradation. |

| Multi-Species Plasma | Evaluate metabolic stability and interspecies differences [26] | Human, mouse, rat, and dog plasma are typical. Significant variability is often observed. |

| Tissue S9 Fractions & Microsomes | Characterize extra-hepatic metabolism (e.g., liver, intestine, kidney) [26] | Kidney microsomes can be critical for peptides like GLP-1 analogs that show faster degradation there. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model passive transcellular and paracellular permeability [25] | Expresses human intestinal transporters (e.g., PEPT1); requires 14-21 day culture for differentiation. |

| Low-Binding Tips & Plates | Minimize nonspecific binding during assays [25] | Essential for obtaining accurate recovery and reliable quantitative results. |

| Permeation Enhancers (e.g., C10) | Investigate strategies to improve membrane permeability [26] | Effects are compound-dependent and require careful optimization. |

PROTACs: ADME Profiling and Optimization

Core ADME Challenges and Optimization Strategies

PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules comprising a target protein-binding ligand, an E3 ubiquitin ligase-binding ligand, and a connecting linker [23]. Their large size (often MW >800 Da), high lipophilicity, and excessive hydrogen bonding capacity place them firmly in the bRo5 space, creating predictable ADME challenges [15]. Key issues include low solubility, poor permeability, and a high propensity for nonspecific binding that can confound in vitro assays [15]. Unlike traditional small molecules, PROTACs act catalytically, meaning they are released after degrading their target protein to engage in multiple cycles, which allows them to be effective at lower doses despite suboptimal PK parameters [23].

Table 3: PROTAC ADME Challenges and Corresponding Optimization Strategies

| ADME Challenge | Impact on Pharmacokinetics | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Permeability | Limits oral absorption and cellular uptake [15] | Reduce H-bond donors (≤3), control MW (≤950 Da), reduce rotatable bonds (≤12), shield HBDs [15] |

| Poor Solubility | Limits absorption, causes unreliable assay results [15] | Optimize linker composition and length, incorporate solubilizing groups, salt formation |

| Nonspecific Binding | Leads to low assay recovery, confounds in vitro data [15] | Add serum proteins (e.g., FCS, BSA) to assays, use low-binding labware [15] |

| Variable Clearance | Difficult to extrapolate from in vitro to in vivo [15] | Use experimentally determined fraction unbound (fu,inc) for IVIVE, not predicted values [15] |

Recent research has established preferred physicochemical property spaces for oral PROTACs to guide optimization. These include limiting H-bond donors (HBDs) to ≤3, molecular weight to ≤950 Da, and rotatable bonds to ≤12 [15]. Notably, reducing solvent-exposed HBDs to ≤2 is a particularly powerful strategy for optimizing permeability, sometimes allowing other parameters (MW, Chromlog D) to be pushed slightly higher [15]. The reduction of exposed polar surface area (ePSA), often through strategic shielding of HBDs, also significantly enhances permeability [15].

Experimental Protocols for PROTAC ADME Profiling

Standard small molecule ADME assays often require adaptation for PROTACs due to their bRo5 properties. The following protocol outlines a tailored discovery assay cascade.

Protocol 2: Tailored In Vitro ADME Profiling for PROTACs

Objective: To reliably characterize the ADME properties of PROTAC candidates, accounting for their unique challenges like nonspecific binding and low solubility.

Materials:

- Test Compounds: PROTAC candidates

- Modified Assay Buffers: HBSS with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) or 0.25-0.5% BSA [15]

- Permeability Systems: Caco-2 cell monolayers or surrogate systems for ePSA determination [15]

- Metabolic Systems: Cryopreserved hepatocytes (multiple species) in suspension [15]

- Analytical Instrumentation: UHPLC-MS/MS system for quantification [15]

Procedure:

Solubility and Nonspecific Binding Assessment:

- Perform kinetic solubility assays in physiologically relevant buffers.

- To assess nonspecific binding, compare compound recovery in standard buffer versus buffer supplemented with 10% FCS or BSA [15].

- Data Analysis: Low recovery (<50%) in standard buffer that improves with serum addition indicates significant nonspecific binding.

Permeability Assessment (Modified Caco-2):

- Culture Caco-2 cells as described in Protocol 1.

- Modify the standard transwell assay by adding 10% FCS to both apical and basolateral compartments to reduce nonspecific binding and improve recovery [15].

- Alternative approach: Use surrogate methods like exposed Polar Surface Area (ePSA) determination as a permeability prognosticator [15] [23].

- Data Analysis: Calculate Papp. Note that for PROTACs, the Caco-2 assay may not be predictive for absorption, so focus on molecular descriptors (MW, HBD count) for prioritization [15].

Metabolic Stability in Hepatocytes:

- Use cryopreserved hepatocytes (e.g., mouse, human) in suspension. Ensure viability is >70% via trypan blue staining [15].

- Incubate compounds (1 µM final) with hepatocytes at a density of 0.2 × 10^6 cells/mL in Krebs-Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C [15].

- Take aliquots at time points (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 90 min), quench with ACN containing internal standard, and analyze via UHPLC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: Determine intrinsic clearance (CLint). For IVIVE, use experimentally determined fraction unbound in incubation (fu,inc), as standard prediction methods (e.g., Kilford equation) are unsuitable for PROTACs and lead to systematic under-prediction [15].

The tailored ADME strategy for PROTACs emphasizes early frontloading of in vivo studies and the use of specific surrogate descriptors for permeability, as illustrated below:

Research Reagent Solutions for PROTAC ADME

Table 4: Key Reagents for PROTAC ADME Assays

| Research Reagent | Function in ADME Profiling | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Proteins (FCS, BSA) | Reduce nonspecific binding in in vitro assays (e.g., Caco-2) [15] | Adding 10% FCS or 0.25-0.5% BSA to assay buffers can dramatically improve recovery. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Determine intrinsic metabolic clearance (CLint) [15] | Use multiple species; require experimentally determined fu,inc for accurate IVIVE. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Assess passive permeability potential (with modifications) [15] | Standard assay may not be predictive for absorption; use serum-modified protocols. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Study ternary complex formation and binding kinetics [23] | Critical for confirming target engagement and understanding degradation efficiency. |

| Analytical UHPLC-MS/MS | Quantify parent compound in all in vitro and in vivo matrices [15] | Essential for dealing with complex molecules and potential metabolite interference. |

Integrating modality-specific ADME profiling during lead optimization is critical for advancing peptides and PROTACs through the drug development pipeline. For peptides, this involves a focus on mitigating metabolic instability and low permeability through strategic structural modifications and specialized in vitro assays. For PROTACs, success hinges on navigating the beyond-rule-of5 property space by controlling key molecular descriptors and adapting standard ADME assays to address unique challenges like nonspecific binding. Employing the detailed protocols, property guidelines, and reagent solutions outlined in this application note will enable researchers to de-risk the development of these advanced modalities, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients.

The Impact of Transporters and Enzymes on Drug Disposition

Within the framework of ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) optimization during lead optimization, understanding the intricate roles of drug-metabolizing enzymes and membrane transporters is paramount. These key regulators are closely linked to the pharmacokinetics (PK), efficacy, and safety profile of drug candidates [28]. The interplay between enzymes and transporters significantly influences a compound's disposition, including its inter-organ distribution and clearance in humans [28] [29]. Predicting these influences from in vitro data remains a central challenge in the drug discovery decision-making process [28]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide researchers in the experimental and strategic evaluation of these critical systems.

Core Concepts and Biological Significance

Key Players in Drug Disposition

Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes (DMEs), such as those from the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), catalyze the biochemical modification of drugs, leading to their activation or inactivation [30]. Membrane Transporters, including those from the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily (e.g., P-glycoprotein/P-gp) and the solute carrier (SLC) superfamily (e.g., OATP1B1), actively facilitate the movement of drugs across cellular barriers in tissues like the intestine, liver, kidney, and blood-brain barrier [29]. Their combined action controls virtually all physiological processes related to drug exposure [31].

Enzyme and Transporter Interactions

Interactions often involve a drug acting as an inhibitor, inducer, or substrate for an enzyme or transporter.

- Enzyme/Transporter Inhibition: A drug (inhibitor) decreases the activity of an enzyme or transporter, potentially leading to increased concentrations of a co-administered substrate drug. Inhibition can be reversible (competitive, uncompetitive, non-competitive, mixed) or irreversible (mechanism-based) [30] [32].

- Enzyme/Transporter Induction: A drug (inducer) increases the expression or activity of an enzyme or transporter, potentially leading to decreased concentrations of a co-administered substrate drug [30] [32].

- Pro-drug Activation: Some drugs are administered as inactive pro-drugs that require enzymatic conversion (e.g., by CYP2D6) to their active form. Inhibition of the activating enzyme can nullify the drug's efficacy [30].

The clinical significance of these interactions depends on factors such as the strength of inhibition/induction, the therapeutic index of the substrate drug, and the involvement of major versus minor metabolic pathways [30].

The diagram below illustrates the core concepts of how enzymes and transporters impact drug disposition at key physiological barriers.

Diagram: Role of Enzymes and Transporters in Drug Disposition. CYP enzymes (red) metabolize drugs, reducing bioavailability. P-gp (blue) effluxes drugs, limiting absorption and distribution. Uptake transporters (green) facilitate hepatic entry.

Quantitative Data and Kinetic Parameters

Approximate Half-Lives of Human Hepatic CYP Enzymes

The half-life of an enzyme is a critical parameter for predicting the time course of induction or irreversible inhibition, as recovery depends on the synthesis of new enzyme [30].

| CYP Enzyme | Median Turnover Half-Life (Hours) |

|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | 39 |

| CYP2C8 | 23 |

| CYP2C9 | 104 |

| CYP2C19 | 26 |

| CYP2D6 | 51 |

| CYP3A4 | 72 |

Table: Approximate median turnover half-lives of human hepatic CYP enzymes. Data sourced from [30].

Kinetic Modifications in Enzyme Inhibition

The following table summarizes the changes to Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters under different types of reversible inhibition. [I] represents the free inhibitor concentration, and Kᵢ is the dissociation constant for the inhibitor-enzyme complex [32].

| Inhibition Type | Apparent Kₘ (Kₘ,ₐₚₚ) | Apparent Vₘₐₓ (Vₘₐₓ,ₐₚₚ) |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Kₘ × (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) | Unchanged (Vₘₐₓ) |

| Uncompetitive | Kₘ / (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) | Vₘₐₓ / (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) |

| Non-Competitive* | Kₘ | Vₘₐₓ / (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) |

| Mixed | Kₘ × (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) / (1 + [I]/αKᵢ) | Vₘₐₓ / (1 + [I]/αKᵢ) |

Table: Kinetic parameter changes under reversible inhibition. *Non-competitive inhibition is a special case of mixed inhibition where α=1 [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Enzyme Phenotyping Using Chemical Inhibitors

Objective: To identify the specific CYP enzyme(s) responsible for the metabolism of a new chemical entity (NCE) in human liver microsomes (HLM).

Principle: Selective chemical inhibitors for specific CYP isoforms are co-incubated with the NCE in HLM. A significant reduction in metabolite formation in the presence of a particular inhibitor indicates the involvement of that CYP pathway [28].

Materials:

- Test system: Pooled human liver microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL protein)

- Test compound: NCE at a concentration ≤ Kₘ

- Co-factor: NADPH regenerating system

- Selective CYP inhibitors (see Reagent Solutions table)

- Stop solution: Acetonitrile with internal standard

- Analytical instrument: LC-MS/MS

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dilute HLM in a suitable buffer (e.g., 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). Prepare a master mix containing HLM and the NADPH regenerating system.

- Pre-incubation: Aliquot the master mix into tubes. Add individual selective inhibitors or vehicle control (for uninhibited control) to respective tubes. Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the NCE substrate.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for a linear, predetermined time (e.g., 10-60 minutes).

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding a volume of ice-cold acetonitrile with internal standard.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge samples to precipitate protein. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to quantify the metabolite formation rate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of remaining activity relative to the uninhibited control. A reduction of >80% by a selective inhibitor is considered strong evidence for the involvement of that pathway.

Protocol: Assessment of P-gp Substrate Status (Caco-2 / MDR1-MDCK Assay)

Objective: To determine if an NCE is a substrate for the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux transporter.

Principle: The bidirectional transport of the NCE is measured across a monolayer of cells expressing P-gp (e.g., Caco-2 or MDR1-MDCK). A net efflux ratio (NER) greater than 2 is indicative of active efflux by P-gp [29].

Materials:

- Cell model: Caco-2 or MDR1-MDCK cells grown on permeable filters

- Test compound: NCE (at two concentrations, one low and one high)

- Transport buffer: Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with HEPES, pH 7.4

- Selective P-gp inhibitor (e.g., Zosuquidar, Verapamil)

- Analytical instrument: LC-MS/MS

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Seed cells on permeable transwell inserts and culture for 21 days (Caco-2) or until a tight monolayer is formed (confirmed by TEER measurement).

- Experimental Design: Perform bidirectional transport studies:

- A-to-B (Apical to Basolateral): Add NCE to the apical chamber, measure appearance in basolateral chamber.

- B-to-A (Basolateral to Apical): Add NCE to the basolateral chamber, measure appearance in apical chamber.

- Conduct both directions in the absence and presence of a selective P-gp inhibitor.

- Incubation: Add transport buffer containing the NCE to the donor compartment and blank buffer to the receiver compartment. Incubate at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- Sampling: Take samples from the receiver compartment at multiple time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 min) and replace with fresh buffer.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to determine the concentration of the NCE.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the apparent permeability (Pₐₚₚ) in both directions.

- Determine the Efflux Ratio (ER) = Pₐₚₚ (B-to-A) / Pₐₚₚ (A-to-B).

- Determine the Net Efflux Ratio (NER) = ER (without inhibitor) / ER (with inhibitor).

- An ER ≥ 2 and a NER ≥ 2 suggests the NCE is a P-gp substrate.

The workflow for conducting these key in vitro assays is summarized below.

Diagram: Key In Vitro Assay Workflow. Parallel experimental pathways for enzyme phenotyping and transporter substrate identification to inform PBPK modeling and DDI risk assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pooled Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | A mixed-gender pool of human liver microsomes containing a full complement of CYP and UGT enzymes for in vitro metabolic stability and phenotyping studies. |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes (rCYP) | Individual CYP isoforms (e.g., rCYP3A4, rCYP2D6) expressed in a standardized system. Used to confirm the specific enzyme responsible for metabolizing a candidate drug. |

| Selective Chemical Inhibitors | Tool compounds that selectively inhibit specific CYP enzymes (e.g., Ketoconazole for CYP3A4, Quinidine for CYP2D6) to identify metabolic pathways in phenotyping studies [30]. |

| MDR1-MDCK II Cells | Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cells transfected with the human MDR1 gene, which encodes for P-gp. This model provides a robust system for assessing P-gp-mediated transport. |

| Caco-2 Cells | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, expresses a range of transporters, including P-gp. Commonly used for permeability and transporter studies. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | A biochemical system (e.g., NADP+, Glucose-6-Phosphate, G6PDH) that supplies the reducing equivalents (NADPH) required for CYP-mediated oxidative reactions. |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Integration with Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

In vitro data on enzyme inhibition/induction and transporter interactions are crucial for building PBPK models. These models integrate physicochemical properties of the drug, in vitro data, and human physiology to simulate and predict complex drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in vivo [33]. For instance, a PBPK model for encorafenib, which is metabolized by CYP3A4 and is a P-gp substrate, successfully predicted its DDIs with CYP3A4 inhibitors like posaconazole, thereby prospectively de-risking its clinical development [33]. The mathematical implementation of enzyme turnover and inhibition in such software is critical for accurate DDI prediction, particularly for time-dependent inactivation [32].

Emerging Technologies: Quantum Machine Learning for QSAR

The field of ADME science is beginning to explore advanced computational methods. Quantum Machine Learning (QML) is being investigated for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) prediction, which relates molecular structures to biological activity. Early research suggests that quantum-classical hybrid models can demonstrate superior generalization power, especially when data availability is limited or when working with a reduced number of molecular features [34]. This could potentially enhance the prediction of whether a new compound is likely to be a substrate or inhibitor of enzymes and transporters, thereby guiding more efficient lead optimization.

Modern ADME Toolbox: From High-Throughput Screening to AI-Driven Prediction

Within modern drug discovery, the optimization of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties is critical for reducing late-stage attrition due to unfavorable pharmacokinetics [35]. A tiered in vitro assay strategy provides a framework for efficiently balancing speed, resource allocation, and data quality during lead optimization. This approach enables research teams to make earlier, more informed decisions by initially employing rapid, lower-cost assays to prioritize compounds, followed by more definitive, resource-intensive studies on the most promising candidates [13] [36]. This application note details the implementation of a two-tiered ADME screening strategy, providing structured protocols, benchmarks, and visualization tools to integrate this efficient screening paradigm into the drug discovery workflow.

The Rationale for a Two-Tiered Screening Strategy

The fundamental principle of a two-tiered strategy is to align the experimental design with the specific decision-making needs at each stage of the research process [36]. In the early phases of lead optimization, the primary goal is to quickly eliminate compounds with suboptimal ADME properties, for which high-quality, rapid data is more valuable than exhaustive, submission-ready datasets. This strategy manages program risk and cost by front-loading efficient screening to focus resources on candidates with the highest probability of success.

- Tier 1 (Early Screening): Designed for high-throughput and rapid turnaround, Tier 1 assays provide preliminary data to guide chemistry efforts and select leads for advanced profiling. The objective is to identify critical ADME liabilities early, enabling prompt corrective action in the design cycle [13].

- Tier 2 (Definitive Profiling): This tier involves more comprehensive and rigorous assays that often adhere to higher quality standards, such as Good Laboratory Practice (GLP). The data generated is suitable for regulatory submissions, such as Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, and provides a robust dataset for candidate selection [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Tiered Study Objectives

| Parameter | Tier 1 (Basic Program) | Tier 2 (IND-Enabling Program) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Early decision-making, inform definitive study design [36] | Generate IND submission-ready data [36] |

| Throughput | High | Medium to Low |

| Resource Level | Low cost, minimal compound use [13] | Higher cost, comprehensive |

| Data Output | Trends and rankings | High-quality, definitive endpoints |

| Report Format | Standard internal report | Comprehensive standard report or eCTD-ready format [36] |

Core Components of a Two-Tiered ADME Assay Panel

A well-designed tiered strategy focuses on key in vitro assays that predict critical in vivo pharmacokinetic outcomes. The following core assays form the foundation of this approach.

Metabolic Stability

Pharmacological Question Addressed: “How long will my parent compound remain circulating in plasma within the body?” [13]

This assay uses hepatic microsomes to provide an initial estimate of a compound's metabolic clearance.

- Tier 1 Protocol (Single Time Point): Metabolic stability is assessed at a single concentration (typically 10 µM) in human liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) over a 60-minute incubation. The result is reported as the percentage of parent compound metabolized at the final time point, allowing for rapid ranking of compounds [13].

- Tier 2 Protocol (Multi-Time Point): A more definitive assay incorporates multiple time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes) to determine the half-life (T½) and intrinsic clearance (CLint), providing superior data for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) [13].

Permeability

Pharmacological Question Addressed: “Will my compound be absorbed?”

Cell-based models like Caco-2 or PAMPA (Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay) are used to predict intestinal absorption.

- Tier 1 Protocol (PAMPA): This non-cell-based assay offers high throughput and is ideal for early screening. It measures the apparent permeability (Papp) of a compound across an artificial membrane, providing a cost-effective initial assessment of passive permeability [6].

- Tier 2 Protocol (Caco-2): This cell-based model provides a more physiologically relevant assessment, as it can identify compounds that are substrates for efflux transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein) in addition to measuring passive permeability, offering a more complete absorption profile [35].

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Inhibition

Pharmacological Question Addressed: “What is the potential for my compound to cause drug-drug interactions (DDI)?”

This assay evaluates the ability of a new chemical entity to inhibit major CYP enzymes, a common cause of clinically significant DDIs.

- Tier 1 Protocol (Single Concentration): Compounds are screened at a single concentration (e.g., 10 µM) against key CYP enzymes (e.g., 3A4, 2D6). The result is reported as percent inhibition, allowing for the rapid flagging of potent inhibitors [36] [35].

- Tier 2 Protocol (IC50 Determination): For compounds showing significant inhibition in Tier 1, a multi-concentration assay is performed to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), which is used for a more quantitative DDI risk assessment [36].

Table 2: Tiered Assay Benchmarks and Rules of Thumb

| Assay | Tier | Key Endpoint | Benchmark for Low Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Stability [13] | 1 | % Metabolized (60 min) | < 30% |

| 2 | In Vitro T½ (min) | > 60 min | |

| Permeability (Caco-2) [35] | 2 | Apparent Permeability (Papp, x 10⁻⁶ cm/s) | > 10 |

| CYP Inhibition [36] | 1 | % Inhibition (@ 10 µM) | < 50% |

| 2 | IC50 (µM) | > 10 µM | |

| Solubility [13] | 1 | Amount Dissolved (µM) | > 100 µM |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tier 1 Metabolic Stability

The following is a standardized protocol for a Tier 1 metabolic stability assay using liver microsomes, a cornerstone of early ADME screening [13].

Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Stability

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) [13] | Subcellular fraction containing drug-metabolizing enzymes (CYPs, UGTs). |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Supplies NADPH, a crucial cofactor for cytochrome P450 enzyme activity. |

| Compounds for Testing | New chemical entities whose metabolic stability is being evaluated. |

| Positive Control (e.g., Testosterone) [13] | A compound with known metabolic activity to verify system functionality. |

| Potassium Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Provides a physiologically relevant pH environment for the incubation. |

| Methanol or Acetonitrile | Used to terminate the metabolic reaction and precipitate proteins. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Preparation of Reaction Cocktail: In a pre-warmed (37°C) tube, prepare the master reaction cocktail to achieve final incubation concentrations of 0.5 mg/mL HLM and test article at 10 µM in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) [13].

- Pre-incubation: Aliquot the reaction cocktail (e.g., 98 µL) into a 96-well plate. Pre-incubate the plate for 5-10 minutes in a shaking incubator at 37°C.

- Initiation of Reaction: Start the reaction by adding a pre-warmed NADPH regenerating system (e.g., 2 µL). For the T=0 control, add the NADPH solution to the negative control well after adding the quenching solvent (Step 4).

- Termination of Reaction: At the predetermined time point (T=60 minutes), quench the reaction by adding a volume of ice-cold acetonitrile containing internal standard that is at least equal to the reaction volume.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched plate at high speed (e.g., 4000 rpm for 15 minutes) to pellet precipitated protein. Transfer the supernatant to a new plate for analysis by LC-MS/MS.

- Data Calculation: Quantify the peak area of the parent compound in the T=60 min sample relative to the T=0 min control. Calculate the percentage of parent compound remaining:

(Peak Area T=60 / Peak Area T=0) * 100.

Implementing a Tiered Strategy: A Practical Scenario

The following scenario illustrates how a tiered approach can be applied to a real-world drug discovery program.

- Scenario A: A client is planning an IND submission and needs to design a Cytochrome P450 induction study. Being budget-sensitive, they want to ensure the study design is correct from the outset [36].

- Tier 1 Application: A Tier 1 induction study using a single, sensitive donor for CYP1A2, 2B6, and 3A4 is recommended. The mRNA data can help inform the full study design. If up-regulation is observed, it would be beneficial to include the CYP2Cs from the beginning, potentially saving weeks compared to a stepwise approach [36].

- Tier 2 Follow-up: Once the Tier 1 study confirms the induction pathway, a Tier 2 CYP induction study is initiated to provide the standard EC50/Emax endpoints required for the IND submission [36].

The adoption of a tiered in vitro assay strategy is a hallmark of an efficient and modern drug discovery organization. By implementing the structured two-tier approach outlined in this application note—utilizing rapid, high-throughput Tier 1 screens to triage compounds and conserve resources, followed by definitive Tier 2 studies to generate robust, submission-ready data—research teams can significantly accelerate lead optimization timelines. This paradigm ensures that critical ADME properties are characterized early, derisking the development pipeline and increasing the likelihood of advancing high-quality drug candidates into clinical development.

The optimization of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) properties is a critical determinant of success in drug discovery, particularly during the lead optimization phase. Poor ADME profiles remain a major cause of compound attrition in later development stages [37]. Traditional in vivo and in vitro ADME screening methods, while valuable, are often resource-intensive, time-consuming, and expensive [38] [27]. Consequently, the application of in silico prediction methods has become indispensable for prioritizing compound synthesis and guiding molecular design.

The field of in silico ADME prediction has evolved significantly, transitioning from simplified relationships based on physicochemical properties to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models [37]. Recent advances leverage techniques such as graph neural networks (GNNs), multitask learning, and explainable AI (XAI) to enhance predictive accuracy and provide insights into the structural features influencing ADME parameters [38] [19]. These approaches are increasingly used to bias medicinal chemistry toward more ideal regions of property space, thereby streamlining the optimization of lead compounds [39].

This application note details the latest methodologies and protocols in in silico ADME prediction, with a specific focus on AI- and GNN-based approaches. It provides a structured framework for their application within lead optimization research, supported by comparative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of key workflows.

Computational Approaches in ADME Prediction

A variety of computational modeling approaches are employed for predicting ADME properties, broadly categorized into descriptor-based models and graph-based models [40].

Descriptor-Based Models

Descriptor-based models rely on hand-crafted molecular representations, such as molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity, polar surface area) and fingerprints (e.g., Extended Connectivity Fingerprints, ECFP), as input features for machine learning algorithms [40]. These representations are used to establish Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models.

- Common Algorithms: Traditional machine learning algorithms used with these descriptors include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [40].

- Utility: These models are highly effective, with studies showing that descriptor-based models can often match or even surpass the predictive accuracy of more complex graph-based models, especially when using comprehensive sets of molecular descriptors and fingerprints [40]. They are also computationally efficient and highly interpretable using methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [40].

Graph-Based Models