Scaffold Hopping in Drug Discovery: AI-Driven Strategies for Novel Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold hopping, a pivotal strategy in medicinal chemistry for generating novel, patentable drug candidates by modifying core molecular structures while preserving biological activity.

Scaffold Hopping in Drug Discovery: AI-Driven Strategies for Novel Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold hopping, a pivotal strategy in medicinal chemistry for generating novel, patentable drug candidates by modifying core molecular structures while preserving biological activity. It explores the foundational principles of scaffold hopping, examines traditional and cutting-edge computational methodologies including AI and generative deep learning, and addresses common challenges and optimization techniques. Through case studies and comparative analyses of tools like ChemBounce and RuSH, the article validates scaffold hopping's success in producing clinical candidates with improved pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current trends and future directions, highlighting how scaffold hopping accelerates the discovery of innovative therapeutic agents.

What is Scaffold Hopping? Core Principles and Strategic Importance in Medicinal Chemistry

Scaffold hopping, a cornerstone strategy in modern medicinal chemistry, involves the deliberate modification of a bioactive compound's core structure to generate novel molecular entities with preserved or improved biological activity. Originally conceptualized by Gisbert Schneider in 1999, this approach has evolved from simple heterocyclic replacements to sophisticated computational design, enabling researchers to navigate chemical space systematically. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, methodological evolution, and practical applications of scaffold hopping within contemporary drug discovery paradigms. By integrating advances in artificial intelligence, multi-component reactions, and computational modeling, scaffold hopping continues to address critical challenges in lead optimization, including intellectual property expansion, pharmacokinetic enhancement, and the exploration of underexplored chemical territories. The following sections provide a comprehensive framework for implementing scaffold hopping strategies, complete with experimental protocols, computational workflows, and analytical tools essential for today's medicinal chemistry research.

The formal term "scaffold hopping" was coined by Gisbert Schneider in 1999 to describe the process of "identifying isofunctional structures with different molecular backbones" [1]. This concept emerged from the recognition that biological activity often depends on specific pharmacophoric arrangements rather than entire molecular skeletons. The strategy draws inspiration from natural product evolution, where diverse scaffolds can produce similar biological effects through convergent molecular recognition.

Scaffold hopping serves multiple critical functions in drug discovery. First, it enables intellectual property expansion by creating novel chemical space around existing pharmacophores, potentially circumventing existing patents while maintaining biological activity [2] [1]. Second, it addresses molecular deficiencies in lead compounds, such as poor pharmacokinetics, toxicity, or metabolic instability, through strategic structural modifications [2] [3]. Third, it facilitates exploration of structure-activity relationships (SAR) by probing how different frameworks position key functional groups for optimal target interaction [1].

The theoretical basis for scaffold hopping rests on the principle of bioisosterism, where functionally equivalent molecular features can substitute for one another while preserving biological activity. This extends beyond traditional atom-for-atom replacement to include topological and shape-based similarities that maintain essential pharmacophoric elements. The effectiveness of scaffold hopping ultimately depends on accurately distinguishing between structural features critical for biological activity and those amenable to modification.

Scaffold Hopping Variants: A Methodological Taxonomy

Scaffold hopping strategies exist along a spectrum of structural complexity, from simple atom-level substitutions to complete molecular topology alterations. These approaches have been systematically categorized into distinct variants based on the nature and extent of structural modification [1].

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Variants

| Variant | Structural Change | Complexity | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° Scaffold Hopping (Heterocycle Replacement) | Substitution or swapping of carbon and heteroatoms in backbone rings | Low | Lead optimization, patent expansion |

| 2° Scaffold Hopping (Ring Closure or Opening) | Cyclization of open chains or ring opening to linear structures | Medium | Solubility improvement, conformational restriction |

| 3° Scaffold Hopping (Peptidomimetics) | Replacement of peptide backbones with non-peptide structures | Medium-High | Enhancing metabolic stability, oral bioavailability |

| 4° Scaffold Hopping (Topology-Based) | Alteration of molecular topology while preserving pharmacophore geometry | High | Exploring novel chemical space, addressing multi-resistance |

First-Degree Scaffold Hopping: Heterocycle Replacement

The simplest form of scaffold hopping involves substituting or swapping carbon and heteroatoms in the backbone ring of a heterocyclic or carbocyclic core, while maintaining connected substituents [1]. This approach was successfully employed in developing TTK inhibitors, where iterative heterocycle replacement transformed an imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine motif to pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine, ultimately yielding CFI-402257 with improved dissolution properties and maintained potency (IC₅₀ = 1.4 nM) [1].

Second-Degree Scaffold Hopping: Ring Closure and Opening

This strategy involves either cyclizing open-chain structures or opening cyclic systems to create linear analogs. A notable application emerged from Sorafenib optimization, where researchers implemented a ring-opening strategy to create quinazoline-2-carboxylate and quinazoline-2-carboxamide-based compounds with maintained VEGFR2 inhibition but altered physicochemical profiles [1].

Third-Degree Scaffold Hopping: Peptidomimetics

Peptidomimetic scaffold hopping replaces peptide backbones with non-peptide structures that mimic the spatial arrangement of key pharmacophoric elements. This approach addresses inherent limitations of peptide therapeutics, including poor metabolic stability and limited oral bioavailability, while preserving biological activity through maintenance of critical interaction motifs [2].

Fourth-Degree Scaffold Hopping: Topology-Based Approaches

The most complex variant involves altering molecular topology while preserving the essential three-dimensional arrangement of pharmacophoric elements. This strategy enables exploration of structurally diverse chemical space while maintaining biological functionality. As Sun et al. categorized in 2012, topology-based hops represent the highest degree of scaffold hopping, often requiring sophisticated computational design [2].

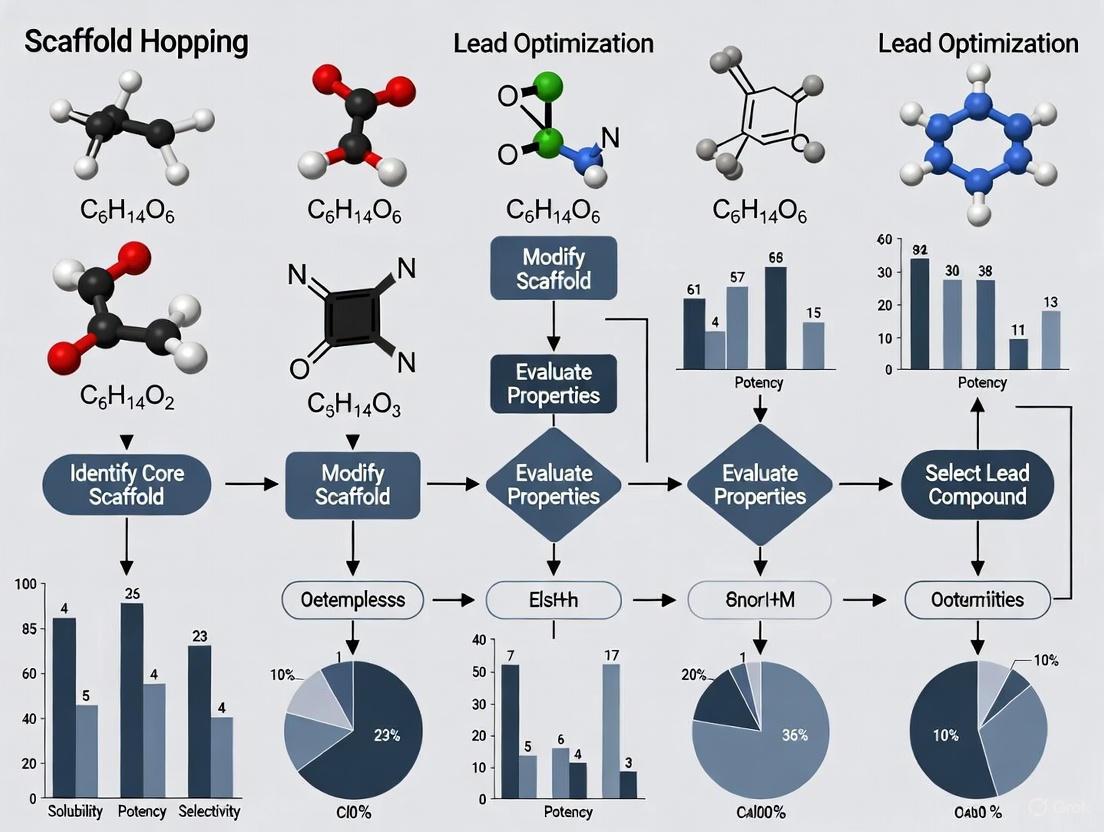

Diagram 1: Scaffold Hopping Variants and Applications. The diagram illustrates the four primary scaffold hopping variants categorized by structural complexity, with connecting pathways to their primary applications in drug discovery.

Modern Computational Approaches and AI-Driven Innovations

The field of scaffold hopping has been transformed by computational methodologies that enable systematic exploration of chemical space beyond human intuition capabilities. Modern approaches leverage artificial intelligence, molecular representation advances, and sophisticated similarity metrics to propose novel scaffolds with high potential for maintaining biological activity.

Molecular Representation Methods

Effective scaffold hopping relies on accurate molecular representations that capture essential features for biological activity. Traditional methods included:

- String-based representations: SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) and InChI provide compact, human-readable molecular encoding but struggle to capture complex structural relationships [2].

- Molecular fingerprints: Extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) encode substructural information as binary strings, enabling similarity calculations and machine learning applications [2].

- Molecular descriptors: Quantitative parameters capturing physicochemical properties, topological features, and electronic characteristics [2].

Modern AI-driven approaches employ more sophisticated representations:

- Graph-based representations: Graph neural networks (GNNs) natively model molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, capturing both local and global structural features [2].

- Language model-based representations: Transformer architectures process SMILES strings as chemical language, learning contextual relationships between molecular substructures [2].

- 3D shape and electrostatic representations: Methods like Electroshape incorporate molecular shape, chirality, and electrostatics for similarity calculations beyond 2D structural features [4].

AI-Driven Scaffold Hopping Platforms

Several computational platforms have emerged specifically for scaffold hopping applications:

AnchorQuery utilizes pharmacophore-based screening of approximately 31 million synthesizable compounds through one-step multi-component reaction chemistry. The platform requires a ligand-bound crystal structure as input and identifies novel scaffolds maintaining critical interaction motifs. In developing molecular glues for the 14-3-3σ/ERα complex, researchers used AnchorQuery to perform pharmacophore-based searches, identifying Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé (GBB) three-component reaction products as promising scaffolds [3].

ChemBounce represents another specialized framework that identifies core scaffolds in user-supplied molecules and replaces them using a curated library of over 3 million fragments derived from the ChEMBL database. Generated compounds are evaluated based on Tanimoto and electron shape similarities to ensure retention of pharmacophores and potential biological activity [4].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Scaffold Hopping

| Tool/Platform | Methodology | Chemical Space | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AnchorQuery | Pharmacophore-based screening | ~31 million synthesizable compounds | Integration with MCR chemistry, structure-based design |

| ChemBounce | Fragment replacement | 3+ million fragments from ChEMBL | Tanimoto and shape similarity evaluation, cloud implementation |

| MORPH | Systematic aromatic ring modification | Customizable | 3D molecular similarity, whole-ligand topology analysis |

| AI-based Molecular Representation | Graph neural networks, transformers | Virtually unlimited | Data-driven feature learning, latent space exploration |

Quantum Chemical Calculations in Scaffold Validation

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide critical insights into electronic properties of scaffold-hopped compounds. In a study targeting tankyrase inhibitors for colorectal cancer, researchers performed DFT calculations using the PySCF quantum chemistry library to investigate frontier molecular orbitals of candidate molecules [5]. The HOMO-LUMO gap served as an indicator of electronic stability, with values around 4.5-5.0 eV representing an optimal balance of stability and reactivity for drug-like molecules [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Successful scaffold hopping requires integration of computational design with experimental validation. This section outlines key methodological frameworks for implementing scaffold hopping strategies in medicinal chemistry research.

Structure-Based Scaffold Hopping Protocol

The following protocol was successfully applied in developing molecular glues for the 14-3-3σ/ERα complex [3]:

Template Selection: Identify a reference compound with confirmed binding mode and biological activity. For the 14-3-3σ/ERα project, researchers used compound 127 (PDB 8ALW) with a covalent bond to C38 of 14-3-3σ as the template.

Pharmacophore Definition: Define critical interaction features from the template's binding mode:

- Anchor motif (e.g., p-chloro-phenyl ring forming halogen bond with K122)

- Hydrophobic interactions (e.g., with L218, I219 of 14-3-3 and Val595 of ERα)

- Hydrogen-bonding patterns (e.g., water-mediated bonds to Val595 carboxylic acid)

Computational Screening: Utilize platforms like AnchorQuery to screen virtual libraries using the defined pharmacophore. Apply molecular weight filters (e.g., <400 Da) and similarity metrics to prioritize hits.

Synthetic Implementation: Employ multi-component reactions (e.g., Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé reaction) for rapid synthesis of diverse analogs. The GBB-3CR combines aldehydes, 2-aminopyridines, and isocyanides to generate imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines.

Biophysical Validation: Assess binding through orthogonal assays:

- Intact mass spectrometry to detect complex formation

- TR-FRET (Time-Resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer) for affinity quantification

- SPR (Surface Plasmon Resonance) for kinetic parameter determination

- X-ray crystallography for structural confirmation

Cellular Activity Assessment: Evaluate functional effects in physiological contexts using assays such as NanoBRET with full-length proteins in live cells.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

For targets without structural information, ligand-based approaches provide an alternative scaffold hopping strategy [5]:

Reference Compound Selection: Choose a compound with confirmed activity against the target. In tankyrase inhibitor development, RK-582 served as the reference.

Similarity Searching: Conduct structural similarity searches in databases like PubChem using appropriate cutoffs (typically 70-80% similarity). This identified 533 structurally similar compounds in the tankyrase study.

Virtual Screening: Apply drug-likeness filters (Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules) to prioritize candidates.

Molecular Docking: Perform docking studies with target structures (e.g., Tankyrase PDB ID: 6KRO) using AutoDock Vina or similar tools.

Dynamics Assessment: Conduct molecular dynamics simulations (500 ns) to evaluate complex stability through RMSD and RMSF fluctuations.

Activity Prediction: Implement machine learning models trained on known inhibitors (236 compounds in the tankyrase study) to predict pIC₅₀ values.

Diagram 2: Integrated Scaffold Hopping Workflow. The diagram outlines key phases in scaffold hopping implementation, from computational design to experimental validation, highlighting the iterative nature of the process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of scaffold hopping strategies requires specialized computational tools, chemical libraries, and experimental resources. The following table details essential components of the scaffold hopping research toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold Hopping Implementation

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | AnchorQuery | Pharmacophore-based screening of synthesizable compounds | Identifying MCR scaffolds for molecular glues [3] |

| ChemBounce | Fragment-based scaffold replacement with similarity evaluation | Generating diverse analogs from ChEMBL fragments [4] | |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking and binding pose prediction | Virtual screening of tankyrase inhibitors [5] | |

| PySCF | Density Functional Theory calculations | Quantum chemical analysis of electronic properties [5] | |

| Chemical Libraries | Multi-component Reaction Libraries | Diverse, synthesizable compound collections | GBB-3CR for imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine synthesis [3] |

| Fragment Libraries | Curated collections for core replacement | ChemBounce's 3M+ fragment library [4] | |

| PubChem Database | Public repository of chemical structures | Similarity searching for tankyrase inhibitors [5] | |

| Experimental Assays | TR-FRET | Biophysical binding affinity measurement | Molecular glue characterization [3] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Kinetic parameter determination | Binding kinetics for optimized scaffolds [3] | |

| Intact Mass Spectrometry | Detection of complex formation | Protein-ligand interaction confirmation [3] | |

| NanoBRET | Cellular target engagement | Functional assessment in live cells [3] |

Case Studies: Successful Scaffold Hopping Applications

Molecular Glues for 14-3-3σ/ERα Stabilization

A recent breakthrough demonstrated scaffold hopping from covalent molecular glues to non-covalent analogs using multi-component reaction chemistry. Researchers began with compound 127, containing a chloroacetamide warhead forming a covalent bond with C38 of 14-3-3σ. Through AnchorQuery screening with a defined pharmacophore (phenylalanine anchor and three additional interaction points), they identified imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine scaffolds via the Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé reaction [3]. The optimized analogs maintained key interactions: halogen bonding with K122, hydrophobic contacts with L218/I219, and water-mediated hydrogen bonds with Val595 of ERα. This scaffold hopping success yielded non-covalent molecular glues with low micromolar cellular activity, demonstrating the power of computational design coupled with divergent synthesis.

Tankyrase Inhibitors for Colorectal Cancer

A comprehensive computational approach identified novel tankyrase inhibitors through structural stability-guided scaffold hopping. Beginning with reference compound RK-582, researchers conducted similarity searching in PubChem (80% cutoff) yielding 533 structurally similar compounds [5]. After virtual screening and DFT calculations, top candidates exhibited favorable HOMO-LUMO gaps (4.473-4.979 eV), indicating optimal electronic stability. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed conformational stability, with selected compounds showing low RMSD/RMSF fluctuations over 500 ns simulations. Machine learning predictions indicated strong tankyrase inhibition (pIC₅₀ = 7.70 for top candidate versus 7.71 for reference). This integrated computational approach demonstrates how scaffold hopping can identify promising candidates with balanced stability and reactivity profiles.

Enzyme-Enabled Terpenoid Scaffold Hopping

An innovative bio-inspired approach demonstrated enzyme-enabled scaffold hopping in terpenoid synthesis. Researchers used engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes to selectively oxidize the commercially available sesquiterpene lactone sclareolide at previously inaccessible positions [6]. The resulting oxygenated intermediate served as a versatile platform for chemical diversification into four distinct terpenoid natural products: merosterolic acid B, cochlioquinone B, (+)-daucene, and dolasta-1(15),8-diene. This strategy challenged traditional retrosynthetic analysis by demonstrating how a single enzymatic transformation could unlock diverse molecular architectures from a common precursor, significantly enhancing synthetic efficiency for complex natural product synthesis.

Scaffold hopping has evolved from Gisbert Schneider's original concept into a sophisticated cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry. The integration of computational prediction, AI-driven molecular representation, and innovative synthetic methodologies has transformed this approach from simple bioisosteric replacement to systematic navigation of chemical space. As the case studies illustrate, successful implementation requires multidisciplinary expertise spanning computational chemistry, synthetic methodology, and biological evaluation.

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas. AI-driven generative models will expand beyond similarity-based approaches to create genuinely novel scaffolds optimized for specific target interfaces. Reaction-aware design platforms will increasingly integrate synthetic feasibility directly into the scoring functions, accelerating the transition from in silico prediction to synthesized compound. Structural biology advances in characterizing challenging targets, including membrane proteins and disordered regions, will provide new templates for scaffold hopping applications.

The continued refinement of scaffold hopping methodologies promises to address persistent challenges in drug discovery, particularly for difficult targets where traditional approaches have struggled. By enabling systematic exploration of chemical space while maintaining critical pharmacological features, scaffold hopping represents a powerful strategy for expanding the druggable genome and delivering innovative therapeutics to address unmet medical needs.

In the intensely competitive landscape of pharmaceutical research and development, the ability to innovate while mitigating risks is paramount. Scaffold hopping, a medicinal chemistry strategy that modifies the core molecular structure of a known bioactive compound, has emerged as a powerful approach to address three critical challenges in drug discovery: expanding intellectual property (IP) space, overcoming toxicity issues, and optimizing suboptimal absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties [1]. This strategy is predicated on the fundamental principle that structurally distinct compounds can maintain biological activity against the same target if they conserve key ligand-target interactions [7]. The strategic importance of scaffold hopping has grown significantly in recent years, with many pharmaceutical companies reducing R&D investments due to risk and low return on investment, instead focusing more on developing generic formulations and manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients [1]. In this context, scaffold hopping represents a calculated approach to de-risk drug discovery by starting from validated molecular templates while creating significantly novel chemical entities that overcome the limitations of existing compounds.

The concept of scaffold hopping was formally introduced by Schneider in 1999 as a technique to identify isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones [8] [2]. However, the strategy itself has been applied since the dawn of drug discovery, with many marketed drugs derived from natural products, natural hormones, and other drugs through scaffold modification [8]. The contemporary definition emphasizes two key components: different core structures and similar biological activities of the new compounds relative to the parent compounds [8]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of how scaffold hopping methodologies are being leveraged to overcome the critical obstacles of IP constraints, toxicity, and poor ADMET properties, thereby accelerating the development of safer, more effective therapeutic agents.

Scaffold Hopping Classification and Methodological Framework

Degrees of Structural Modification

The structural modifications in scaffold hopping exist on a spectrum from minor alterations to complete molecular overhauls. Sun et al. (2012) established a practical framework for classifying scaffold hopping into four distinct degrees based on the type of structural core change relative to the parent molecule [8] [7] [2]. This classification system provides medicinal chemists with a systematic approach to planning and executing scaffold hopping campaigns.

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches by Degree of Structural Modification

| Degree | Type of Change | Structural Novelty | Success Rate | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° (Heterocyclic Replacement) | Substitution, addition, or removal of heteroatoms; replacement of one heterocycle with similar heterocycle | Low | Relatively high | SAR studies, tuning physicochemical properties, optimizing PK profile [7] |

| 2° (Ring Opening/Closure) | Breaking or forming rings to alter ring systems | Medium | Medium | Reducing molecular flexibility, improving absorption, modifying metabolic pathways [8] |

| 3° (Peptidomimetics) | Replacement of peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties | High | Variable | Converting peptides to orally available drugs, improving metabolic stability [8] |

| 4° (Topology-Based Hopping) | Comprehensive changes to molecular topology and scaffold architecture | Very High | Lower | Creating backup series, establishing strong IP position, addressing multi-parameter optimization [8] |

Experimental Workflow for Scaffold Hopping

The implementation of a scaffold hopping campaign follows a logical, iterative process that integrates computational design with experimental validation. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow:

Overcoming Intellectual Property Constraints

Strategic Expansion of IP Space

In the pharmaceutical industry, where patent protection is crucial for securing return on investment, scaffold hopping provides a strategic pathway to create novel patentable chemical entities while working from validated starting points [1]. The fundamental premise is that by generating compounds with significantly different molecular backbones from existing drugs, companies can establish their own proprietary IP position even when targeting well-established biological pathways [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting "non-new" therapeutically interesting targets, where exploration of novel chemistries can be based on known ligands or ligand-protein complex structures [8].

The legal foundation for IP protection of scaffold-hopped compounds rests on the requirement of non-obviousness and novelty in patent law. Even minor structural modifications can be sufficient for patent protection if they require different synthetic routes, as noted by Boehm et al., who classified two scaffolds as different if they were synthesized using different synthetic routines, regardless of how small the change might be [8]. This principle is exemplified by the phosphodiesterase enzyme type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors Sildenafil and Vardenafil, where the primary structural variation is the swap of a carbon atom and a nitrogen atom in a 5-6 fused ring system—a change sufficient for the two molecules to be covered by different patents [8]. Similarly, the two cyclooxygenase II (COX-2) inhibitors Rofecoxib (Vioxx) and Valdecoxib (Bextra) differ primarily in the 5-member hetero rings connecting two phenyl rings, yet they were marketed by different pharmaceutical companies under separate patent protection [8].

Computational Approaches for IP-Driven Scaffold Hopping

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for IP-driven scaffold hopping [7]. This approach utilizes 3D structural data from sources such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to model receptor-ligand interactions [7]. Molecular docking, the core technique of SBVS, predicts binding modes and estimates interaction strength between a small molecule (typically obtained from commercially available libraries such as PubChem, ChEMBL, or ZINC) and the protein target [7]. By identifying alternative scaffolds that maintain key interactions with the target protein but differ sufficiently in their core structure, researchers can systematically design around existing patent claims.

Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) represents another important computational approach, particularly when 3D structural information about the target is limited [7]. LBVS identifies candidate scaffolds with key similar chemical features critical for protein binding using molecular fingerprints and similarity assessment metrics such as the Tanimoto score [7]. Advanced implementations combine multiple similarity metrics to identify promising scaffold hopping candidates. For instance, one study identified new topoisomerase II poison scaffolds by combining 3D shape similarity and biological activity similarity while requiring 2D fingerprint dissimilarity, successfully discovering new chemotypes with Top2 inhibitory activity [9].

Addressing Toxicity and ADMET Limitations

Systematic ADMET Optimization

The optimization of ADMET properties has become a critical focus in modern drug discovery, as these factors account for a significant proportion of clinical phase failures [10]. Scaffold hopping provides a powerful strategy to address ADMET limitations that cannot be remedied through simple peripheral modifications of a problematic scaffold [1]. The advent of computational ADMET prediction tools has significantly accelerated this optimization process, allowing researchers to prioritize scaffolds with favorable predicted properties before embarking on resource-intensive synthetic efforts.

ADMETopt2 is a specialized web server that exemplifies this approach, applying scaffold hopping and transformation rules specifically for ADMET optimization in drug design [11] [10]. This server leverages more than 50,000 unique scaffolds extracted by fragmenting chemical libraries, including ChEMBL and Enamine, and up to 105,780 transformation rules derived from matched molecular pair analysis on various ADMET property datasets [11]. The system can predict and optimize numerous ADMET properties, including blood-brain barrier permeability, human intestinal absorption, P-glycoprotein inhibition, CYP450 inhibitory promiscuity, Ames mutagenicity, hepatotoxicity, and various other toxicity endpoints [11].

Table 2: Key ADMET Properties Addressable via Scaffold Hopping and Corresponding Optimization Strategies

| ADMET Property | Scaffold Hopping Approach | Impact on Drug Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Human Intestinal Absorption | Ring opening to reduce molecular rigidity; heterocycle replacement to modify hydrogen bonding capacity | Improved oral bioavailability [8] [11] |

| Metabolic Stability | Replacement of metabolically labile heterocycles; ring closure to block metabolic soft spots | Reduced clearance, longer half-life [1] |

| Hepatotoxicity | Structural modification to eliminate reactive metabolic intermediates; reduction of lipophilicity | Improved safety profile, reduced liver enzyme elevations [11] |

| hERG Inhibition | Reduction of basic nitrogen atoms; introduction of steric hindrance near cationic centers | Reduced cardiac toxicity risk [11] |

| Solubility | Introduction of ionizable groups; modification of crystal packing through asymmetric scaffolds | Improved formulation, higher exposure [7] |

| CYP450 Inhibition | Reduction of lipophilic surface area; modification of iron-coordinating groups | Reduced drug-drug interaction potential [11] |

Case Study: Aurone Optimization Through Scaffold Hopping

Natural aurones (2-benzylidenebenzofuran-3(2H)-ones) represent an intriguing class of minor flavonoids with diverse biological activities, but their development as drugs has been hampered by several P3 (physicochemical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic) issues common to natural polyphenols, including limited solubility, cellular permeability, suboptimal bioavailability, and metabolic instability [12]. Scaffold hopping has been employed to address these limitations through systematic O-to-N and O-to-S bioisosteric replacements, generating nitrogen (azaaurones) and sulfur (thioaurones) analogues with improved properties [12].

The synthetic approaches to azaaurones (indolin-3-one derivatives) demonstrate how scaffold hopping can generate novel chemotypes with improved synthetic accessibility and drug-like properties [12]. Traditional synthetic methods involve Knoevenagel-aldol condensation of indolin-3-one or 1H-indol-3-yl-acetate intermediates with aromatic aldehydes, while more recent one-pot methods employ organocatalyzed cross-coupling reactions, such as Sonogashira reactions or gold-catalyzed protocols, to streamline synthesis and improve yields [12]. These synthetic advancements are crucial for enabling extensive structure-activity relationship studies and producing analogues with optimized ADMET profiles.

The biological evaluation of these scaffold-hopped aurone analogues has demonstrated maintained or improved target engagement while addressing specific ADMET limitations. For instance, certain azaaurone derivatives have shown enhanced metabolic stability compared to their natural counterparts, addressing the ease of oxidation of the polyphenolic framework that plagues many natural products [12]. Similarly, specific synthetic approaches enable the introduction of solubilizing groups or modification of electronic properties that improve aqueous solubility without compromising target binding [12].

Computational and AI-Driven Advancements in Scaffold Hopping

Traditional vs. Modern Molecular Representation Methods

The effectiveness of scaffold hopping campaigns is heavily dependent on how molecular structures are represented and compared. Traditional molecular representation methods include molecular descriptors (quantifying physical/chemical properties) and molecular fingerprints (encoding substructural information as binary strings or numerical values) [2]. The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) provides a compact string-based representation that has been widely adopted [2]. While these traditional representations are computationally efficient and useful for similarity searching and QSAR modeling, they often struggle to capture the subtle and intricate relationships between molecular structure and function, particularly for scaffold hopping applications that require navigating vast chemical spaces [2].

Modern AI-driven molecular representation methods have emerged to address these limitations, employing deep learning techniques to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large and complex datasets [2]. Models such as graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformers enable these approaches to move beyond predefined rules, capturing both local and global molecular features [2] [13]. These representations better reflect the subtle structural and functional relationships underlying molecular behavior, thereby providing more powerful tools for scaffold hopping and lead optimization [2].

Table 3: Computational Tools for Scaffold Hopping Implementation

| Tool/Software | Methodology | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMETopt2 | Scaffold hopping with transformation rules | ADMET optimization | >50k unique scaffolds; >105k transformation rules; predicts 15+ ADMET properties [11] |

| Molecular Docking | Structure-based virtual screening | Target-informed hopping | Uses 3D protein structure; predicts binding modes; free energy calculations [7] |

| ROCS | 3D shape similarity | Shape-based hopping | Maximizes molecular overlap; identifies shape-similar but structurally diverse compounds [9] |

| FP-ADMET/MolMapNet | AI-based descriptor analysis | Property prediction | Transforms descriptors to 2D feature maps; uses CNNs for ADMET prediction [2] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Learned molecular representations | Chemical space exploration | Captures non-linear structure-property relationships; enables generative design [2] |

Integrated Computational Workflow

The most effective scaffold hopping campaigns combine multiple computational approaches in an integrated workflow. The following diagram illustrates how these methods synergize to identify novel scaffolds with optimized properties:

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Hopping Validation

The successful implementation of scaffold hopping requires rigorous experimental validation to confirm that the novel scaffolds maintain target engagement while exhibiting improved properties. Below are detailed methodologies for key validation experiments frequently cited in scaffold hopping research:

Molecular Docking Protocol for Binding Mode Assessment

- Preparation of Protein Structure: Obtain 3D structure from Protein Data Bank (PDB). Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms and optimize hydrogen bonding networks using tools like MOE or Maestro [7] [9].

- Ligand Preparation: Draw candidate structures in ChemDraw or similar software. Convert to 3D structures and perform energy minimization using MMFF94 or similar force field. Generate possible tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH [9].

- Docking Procedure: Define binding site based on known ligand coordinates. Use docking software such as AutoDock Vina or GOLD. Set exhaustiveness parameter to at least 8 for Vina to ensure comprehensive sampling. Perform blind docking if binding site is unknown [9].

- Analysis: Cluster results by root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Examine key interactions (hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking, hydrophobic contacts). Compare binding modes of novel scaffolds with original compound [9].

In Vitro Topoisomerase II Decatenation Assay

- Principle: Measures compound ability to inhibit Topoisomerase II-mediated decatenation of kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) [9].

- Reagents: Topoisomerase II enzyme, kinetoplast DNA (kDNA), assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT), test compounds dissolved in DMSO, agarose gel electrophoresis supplies [9].

- Procedure: Pre-incubate Topoisomerase II (2-4 units) with test compounds (0.1-100 μM range) for 5 minutes at 37°C. Add kDNA (0.2-0.5 μg) and incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C. Stop reaction with stop buffer (5% Sarkosyl, 0.0025% bromophenol blue, 25% glycerol). Run samples on 1% agarose gel in TBE buffer at 4°C for 2-3 hours at 4V/cm. Visualize with ethidium bromide staining [9].

- Analysis: Quantify remaining catenated DNA versus decatenated DNA using densitometry. Calculate IC50 values using non-linear regression of inhibition curves [9].

Cytotoxicity Profiling Using NCI60 Panel

- Cell Culture: Maintain 60 human tumor cell lines in RPMI-1640 medium with 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM L-glutamine [9].

- Compound Treatment: Prepare 5-10 concentration dilutions of test compounds. Treat cells for 48 hours [9].

- Viability Assessment: Use sulfothodamine B (SRB) assay to measure cellular protein content as surrogate for cell mass. Fix cells with trichloroacetic acid, stain with SRB, and dissolve bound dye with Tris buffer [9].

- Data Analysis: Calculate pGI50 values (-log10 of molar concentration causing 50% growth inhibition). Generate mean graphs and compare patterns of sensitivity across cell lines [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold Hopping Implementation and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, Enamine, PubChem | Source of diverse scaffolds for virtual screening | Size, diversity, drug-like filters, availability [11] [2] |

| Target Proteins | Recombinant enzymes (Topoisomerase II, Kinases, etc.) | In vitro activity and binding assays | Purity, activity, storage conditions [9] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | NCI60 panel, primary cells, engineered cell lines | Cytotoxicity profiling, mechanism validation | Relevance to disease model, growth characteristics [9] |

| Computational Software | MOE, Schrodinger Suite, OpenEye ROCS, RDKit | Structure-based design, molecular modeling, similarity searching | Accuracy of scoring functions, conformational sampling [8] [9] |

| AI/ML Platforms | Graph neural networks, Transformers, VAEs | Chemical space exploration, molecular generation | Training data quality, representation learning capability [13] [2] |

Scaffold hopping represents a sophisticated strategic approach that directly addresses three critical challenges in modern drug discovery: intellectual property constraints, toxicity issues, and suboptimal ADMET properties. Through systematic modification of molecular backbones—ranging from simple heterocycle replacements to comprehensive topology-based overhauls—medicinal chemists can generate novel chemical entities with improved patent positions, enhanced safety profiles, and optimized pharmacokinetic characteristics. The integration of advanced computational methods, including structure-based design, AI-driven molecular representation, and predictive ADMET modeling, has transformed scaffold hopping from an artisanal practice to a systematic discipline capable of navigating the complex multi-parameter optimization required for successful drug development. As pharmaceutical R&D continues to face pressures related to efficiency, cost, and success rates, scaffold hopping stands as a powerful methodology for de-risking the drug discovery process while fostering innovation through the rational transformation of validated molecular templates into novel therapeutic agents with superior clinical potential.

In the intensely competitive landscape of pharmaceutical research, the ability to efficiently generate novel chemical entities with improved properties constitutes a critical strategic advantage. Scaffold hopping, a term first coined by Schneider and colleagues in 1999, has emerged as an indispensable strategy for achieving this objective [8] [2]. This approach is formally defined as the identification of isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones, aiming to discover novel core structures (scaffolds) while retaining similar biological activity or target interaction as the original molecule [8] [2]. The central premise of scaffold hopping challenges, yet operates within, the boundaries of the similarity property principle, which states that structurally similar compounds typically possess similar biological activities. The successful application of scaffold hopping demonstrates that while ligands binding the same pocket must share certain complementary features—such as shape and electropotential surface—they can indeed belong to strikingly different chemotypes [8] [14].

The therapeutic and commercial motivations for scaffold hopping are substantial. First, existing lead compounds often suffer from undesirable properties such as toxicity, metabolic instability, poor solubility, or inadequate pharmacokinetic profiles [8] [2]. Second, by creating compounds with structurally distinct cores, researchers can establish robust intellectual property positions and develop patentable chemical space beyond existing compounds [2] [1]. The strategic importance of scaffold hopping is evidenced by its role in developing marketed drugs including Vadadustat, Bosutinib, Sorafenib, and Nirmatrelvir [15]. As drug discovery faces increasing challenges with target validation, chemical space exploration, and development timelines, scaffold hopping provides a systematic methodology for accelerating the identification of viable drug candidates with optimized molecular medicinal properties encompassing pharmacodynamics, physicochemical characteristics, and pharmacokinetics (P3 properties) [1].

A Four-Tiered Classification System for Scaffold Hopping

The taxonomy of scaffold hopping approaches has been systematically categorized into a four-tiered classification system that reflects increasing degrees of structural modification and novelty [8] [2] [14]. This hierarchical framework—encompassing heterocyclic replacements, ring opening/closure, peptidomimetics, and topology-based hopping—enables medicinal chemists to conceptualize and plan scaffold modification strategies with varying levels of ambition and risk. The following sections provide detailed technical examinations of each category, including their underlying principles, methodological approaches, experimental protocols, and illustrative case studies from drug discovery campaigns.

Table 1: Four-Tiered Classification System for Scaffold Hopping

| Hop Category | Degree of Structural Change | Key Objective | Typical Structural Novelty | Success Rate Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1°: Heterocycle Replacements | Low | Bioisosteric replacement while maintaining vector geometry | Low to moderate | High success rate due to conservative nature |

| 2°: Ring Opening/Closure | Medium | Modulation of molecular flexibility and conformational entropy | Moderate | Medium success rate |

| 3°: Peptidomimetics | Medium to High | Transformation of peptides into drug-like small molecules | Moderate to high | Variable, depends on complexity of peptide target |

| 4°: Topology-Based Hopping | High | Identification of fundamentally different core architectures | High | Lower success rate but high impact |

1° Hop: Heterocycle Replacements

Heterocyclic replacements represent the most fundamental category of scaffold hopping, involving the substitution or swapping of carbon and heteroatoms (e.g., nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur) within a heterocyclic or carbocyclic ring system that serves as the molecular core [8] [14] [1]. This approach maintains the outgoing vectors of the original scaffold while modifying the electronic properties, hydrogen bonding capacity, solubility, or metabolic stability of the core structure. The strategic value of heterocycle replacements lies in their ability to generate patentably distinct scaffolds through relatively conservative chemical modifications that preserve the essential pharmacophoric elements and overall molecular geometry.

A seminal example demonstrating the commercial significance of heterocycle replacements can be observed in the development of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors. The structural variation between Sildenafil and Vardenafil primarily involves the swap of a carbon atom and a nitrogen atom in the 5-6 fused ring system (Figure 3a and 3b), yet this subtle modification was sufficient to secure distinct patent protection for each compound [8]. Similarly, in the cyclooxygenase-II (COX-2) inhibitor class, Rofecoxib (Vioxx) and Valdecoxib (Bextra) differ principally in their 5-membered heterocyclic rings connecting two phenyl rings (Figure 3c and 3d), leading to separate commercial development by Merck and Pharmacia/Pfizer, respectively [8]. These examples underscore the principle that even minimal heterocyclic alterations can establish novel chemical entities with distinct intellectual property positions.

Table 2: Representative Heterocyclic Bioisosteres in Scaffold Hopping

| Original Heterocycle | Common Bioisosteric Replacements | Key Property Modifications | Therapeutic Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenyl ring | Pyridine, Pyrimidine, Thiophene | Enhanced solubility, altered electronic distribution | Antihistamines (e.g., Azatadine) [8] |

| Imidazole | Pyrazole, Triazole, Tetrazole | Modified metall binding, reduced basicity | Antifungal agents, COX-2 inhibitors |

| Pyridine | Pyridone, Pyrimidine, Pyrazine | Altered hydrogen bonding capacity | Kinase inhibitors |

| Piperidine | Tetrahydropyran, Morpholine | Reduced basicity, metabolic stability | CNS agents |

The experimental workflow for heterocycle replacement typically initiates with a comprehensive analysis of the original scaffold's role in target binding and molecular properties. Critical considerations include: (1) identifying key atoms involved in direct target interactions that must be preserved; (2) mapping the vector geometry of substituent attachment points; (3) analyzing the electronic distribution and aromaticity of the ring system; and (4) evaluating potential metabolic soft spots. Computational approaches significantly enhance this process through molecular docking studies to validate proposed bioisosteres, electrostatic potential mapping to compare charge distributions, and molecular dynamics simulations to assess conformational stability. The synthesis of candidate compounds typically employs parallel synthesis methodologies to efficiently generate arrays of analogous heterocycles for systematic structure-activity relationship (SAR) evaluation.

2° Hop: Ring Opening and Closure

Ring opening and ring closure strategies constitute the second category of scaffold hopping, involving more substantial modifications to molecular architecture through the strategic cleavage or formation of cyclic systems [8] [14]. These approaches directly manipulate molecular flexibility, which profoundly influences both the entropic component of binding free energy and key drug-like properties including membrane penetration, absorption, and metabolic stability [8] [14]. Ring opening typically increases conformational freedom and may enhance solubility, while ring closure reduces flexibility, potentially improving potency by pre-organizing the molecule into its bioactive conformation and reducing the entropy penalty upon target binding.

The classical transformation of morphine to tramadol provides a historically significant illustration of ring opening as a scaffold hopping strategy (Figure 1) [8] [14]. Morphine possesses a rigid 'T'-shaped structure with multiple fused rings that confers potent analgesic activity but also significant addictive potential and adverse effects including respiratory depression. Through strategic bond cleavage and opening of three fused rings, tramadol emerges as a more flexible molecule with reduced potency but substantially improved safety profile and oral bioavailability [8]. Despite their dramatically different two-dimensional structures, three-dimensional superposition reveals conservation of key pharmacophore features: a positively charged tertiary amine, an aromatic ring, and a hydroxyl group (with tramadol's methoxyl group undergoing metabolic demethylation to yield the active hydroxyl form) [8]. This conservation of essential pharmacophoric elements in three-dimensional space exemplifies the fundamental principle of scaffold hopping.

Conversely, ring closure strategies can transform flexible molecules into constrained analogs with enhanced properties. The evolution of antihistamines provides a compelling case study (Figure 2) [8] [14]. Pheniramine, a classical antihistamine featuring two aromatic rings joined to a central atom with a positive charge center, served as the starting point. Through ring closure, both aromatic rings of pheniramine were locked into their active conformation via incorporation into a tricyclic system, producing cyproheptadine with significantly improved binding affinity against the H1-receptor [8]. Additional rigidification through introduction of a piperidine ring further reduced molecular flexibility, enhancing both potency and absorption. This structural evolution continued with isosteric replacement of one phenyl ring in cyproheptadine with thiophene to yield pizotifen, which demonstrated improved therapeutic utility for migraine prophylaxis [8] [14]. Subsequent replacement of a phenyl ring with pyrimidine in azatadine further enhanced solubility while maintaining the essential pharmacophore orientation [8].

The methodological approach to ring opening/closure strategies requires meticulous conformational analysis to identify flexible bonds suitable for cleavage or sites for cyclization. Computational techniques include: (1) molecular dynamics simulations to identify preferred conformations and torsion angle distributions; (2) conformational entropy calculations to quantify the flexibility penalty; (3) pharmacophore mapping to ensure conservation of critical features; and (4) strain energy calculations for proposed ring systems. Synthetic implementation typically employs strategic disconnection/reconnection approaches, often leveraging ring-closing metathesis, lactamization, or cycloaddition chemistry for ring formation, or selective oxidative cleavage, hydrolysis, or retro-synthetic fragmentation for ring opening.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ring opening and closure strategies in scaffold hopping

3° Hop: Peptidomimetics and Pseudopeptides

The third category of scaffold hopping addresses the significant challenge of developing drug-like molecules from biologically active peptides, which play vital physiological roles as hormones, growth factors, and neuropeptides [8] [14]. Native peptides typically exhibit poor metabolic stability, limited oral bioavailability, and unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties, severely restricting their therapeutic application. Peptidomimetics and pseudopeptides represent sophisticated scaffold hopping approaches that transform peptide structures into non-peptide small molecules while preserving key pharmacophoric elements and biological activity [8] [14]. This category encompasses diverse strategies including modification of peptide backbones through isosteric replacement, conformational constraint, and topographical stabilization.

The fundamental objective of peptidomimetic design is to retain the critical residues and spatial orientation necessary for biological activity while replacing the inherently flexible and metabolically vulnerable peptide backbone with robust, drug-like scaffolds. Successful implementation requires meticulous analysis of the peptide-protein interaction to identify: (1) key side chain functionalities that mediate binding; (2) essential backbone conformations (e.g., β-turns, α-helices, γ-turns); (3) hydrogen bonding patterns; and (4) topological constraints. Computational approaches include molecular dynamics simulations of peptide-receptor complexes, pharmacophore modeling of key interaction features, and de novo design of constrained scaffolds that mimic peptide topography.

Advanced peptidomimetic strategies have been successfully applied to numerous therapeutic targets. Representative approaches include: (1) replacement of amide bonds with bioisosteres such as olefins, heterocycles, or sulfonamides to enhance metabolic stability; (2) incorporation of rigid scaffolds (e.g., benzodiazepines, terphenyls, spirocycles) to pre-organize side chain functionalities; (3) use of β-turn mimetics to stabilize specific peptide conformations; and (4) development of proteomimetics that replicate protein secondary structures. These strategies have yielded clinical candidates and marketed drugs across diverse therapeutic areas including oncology, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular disease.

The experimental protocol for peptidomimetic development typically initiates with alanine scanning or analogous mutagenesis studies to identify critical residues, followed by structural biology approaches (X-ray crystallography, NMR) to determine the bioactive conformation. Design iterations employ computational chemistry to propose and evaluate mimetic scaffolds, followed by synthetic implementation often utilizing solid-phase synthesis, combinatorial chemistry, or diversity-oriented synthesis. Biological evaluation must assess not only potency but also key drug-like properties including metabolic stability in liver microsomes, membrane permeability in Caco-2 or MDCK models, and oral bioavailability in preclinical species.

4° Hop: Topology-Based Scaffold Hopping

Topology-based scaffold hopping represents the most ambitious category, aiming to identify fundamentally different molecular architectures that maintain similar spatial arrangements of critical pharmacophoric features [8] [14]. This approach seeks high degrees of structural novelty through modifications that alter the overall molecular graph or connectivity while preserving the three-dimensional topography essential for biological activity. The conceptual foundation of topology-based hopping rests on the observation that proteins typically recognize ligands through complementary surfaces and specific interaction points rather than particular atomic connectivities, creating opportunity for diverse molecular skeletons to fulfill similar recognition roles.

The implementation of topology-based hopping presents significant technical challenges, requiring sophisticated computational methods capable of navigating vast chemical spaces to identify divergent scaffolds with similar three-dimensional pharmacophore presentation. Successful applications typically employ: (1) 3D pharmacophore screening against large chemical databases; (2) shape-based similarity searching using molecular shape descriptors; (3) graph theory approaches to identify structurally distinct scaffolds with similar pharmacophore placement; and (4) machine learning models trained on structural and bioactivity data to predict novel scaffolds with conserved bioactivity.

A contemporary example demonstrating the power of topology-based scaffold hopping emerges from the development of molecular glues targeting the 14-3-3σ/ERα protein-protein interaction (PPI) [3]. Researchers employed the computational tool AnchorQuery to perform pharmacophore-based screening of approximately 31 million synthetically accessible compounds derived from multi-component reactions (MCRs) [3]. The screening protocol used a known molecular glue (compound 127) as a template, preserving a deeply buried p-chloro-phenyl "anchor" motif while allowing significant variation in other structural elements. This topology-based approach successfully identified novel imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine scaffolds through the Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé multi-component reaction that maintained complementary shape and interaction capabilities at the composite 14-3-3σ/ERα interface [3]. The resulting compounds demonstrated stabilization of the 14-3-3σ/ERα complex in biophysical assays and cellular models, validating the topology-based hopping approach for this challenging PPI target.

Table 3: Computational Methods for Topology-Based Scaffold Hopping

| Methodology | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Representative Software/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Pharmacophore Screening | Identifies compounds matching spatial arrangement of chemical features | Target-agnostic, handles scaffold diversity | LigandScout, Phase |

| Shape-Based Similarity | Compares molecular volume and shape complementarity | Alignment-independent, captures steric requirements | ROCS, ElectroShape [15] |

| Graph-Based Methods | Analyzes molecular connectivity and subgraph isomorphism | Explicitly models structural relationships, scaffold networks | SHOP, ReCore [16] |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Learns structure-activity relationships from data | Can extrapolate to novel chemotypes, handles complexity | Deep generative models, Transformer-based models [2] |

The experimental workflow for topology-based scaffold hopping typically involves generation of a 3D pharmacophore hypothesis from a known active structure, followed by database screening using both shape-based and pharmacophore-based similarity metrics. The ChemBounce framework exemplifies a modern implementation, utilizing a curated library of over 3 million synthesis-validated scaffolds from the ChEMBL database [15]. This approach combines Tanimoto similarity based on molecular fingerprints with electron shape similarity calculations using the ElectroShape method to ensure conservation of both charge distribution and three-dimensional shape properties [15]. Advanced implementations may incorporate synthetic accessibility scoring, property-based filtering, and interactive visualization to facilitate rapid triaging of proposed scaffold hops.

Diagram 2: Topology-based scaffold hopping workflow integrating multiple similarity metrics and synthetic accessibility assessment

Computational Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

The implementation of scaffold hopping strategies has been significantly accelerated by the development of specialized computational frameworks that integrate molecular representation, similarity assessment, and synthetic planning. Modern approaches have evolved from traditional descriptor-based methods to artificial intelligence-driven platforms that leverage deep learning architectures including graph neural networks (GNNs), transformers, and variational autoencoders (VAEs) [2]. These AI-driven molecular representation methods employ deep learning techniques to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large and complex datasets, enabling more effective navigation of chemical space for scaffold hopping applications [2].

The ChemBounce framework exemplifies a contemporary open-source tool for scaffold hopping that operationalizes many of these computational advances [15]. This platform implements a systematic workflow beginning with input structure processing in SMILES format, followed by molecular fragmentation using the HierS algorithm to identify diverse scaffold structures within the input molecule [15]. The HierS methodology decomposes molecules into ring systems, side chains, and linkers, preserving atoms external to rings with bond orders >1 and double-bonded linker atoms within their respective structural components [15]. Basis scaffolds are generated by removing all linkers and side chains, while superscaffolds retain linker connectivity, with the recursive process systematically removing each ring system to generate all possible combinations until no smaller scaffolds exist [15].

For database searching, ChemBounce leverages a curated library of over 3 million unique scaffolds derived from the ChEMBL database, with Tanimoto similarity calculations based on molecular fingerprints used to identify candidate replacement scaffolds [15]. Critical to maintaining biological activity, the framework incorporates ElectroShape-based molecular similarity calculations that consider both charge distribution and 3D shape properties, ensuring that scaffold-hopped compounds maintain structural compatibility with query molecules [15]. This integrated assessment of multiple similarity metrics enhances the probability of conserving pharmacophoric elements while exploring significant structural diversity.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold Hopping Implementation

| Reagent/Chemical Tool | Function in Scaffold Hopping | Application Context | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database Extracts | Source of synthesis-validated scaffolds | Building diverse replacement libraries | Curate for lead-likeness, exclude problematic motifs |

| Multi-Component Reaction (MCR) Building Blocks | Rapid generation of complex scaffolds | Diversity-oriented synthesis of hop candidates | Prioritify isocyanides, aminoazoles, carbonyl compounds |

| Molecular Fingerprinting Algorithms (ECFP, FCFP) | Computational similarity assessment | Virtual screening of candidate scaffolds | Optimize radius and bit length for specific application |

| Shape-Based Similarity Tools (ROCS, ElectroShape) | 3D molecular similarity evaluation | Conservation of pharmacophore geometry | Requires conformation generation, computationally intensive |

| Synthetic Accessibility Scoring (SAscore, PReal) | Prioritization of synthetically feasible hops | Triaging virtual screening hits | Balance complexity with synthetic tractability |

Advanced computational methods for scaffold hopping continue to emerge, including transformer-based models that treat molecular representations (e.g., SMILES) as sequences and learn contextual relationships between molecular substructures [2]. Graph neural networks capture both local atom environments and global molecular topology, enabling more nuanced similarity assessments that transcend traditional fingerprint-based approaches [2]. These AI-driven methodologies demonstrate particular utility for challenging hopping scenarios such as topology-based hops where traditional similarity metrics may fail to identify structurally divergent but functionally equivalent scaffolds.

The experimental validation of computational scaffold hopping proposals follows a rigorous protocol encompassing synthetic feasibility assessment, compound synthesis, and multidimensional biological evaluation. Initial triaging employs synthetic accessibility scores (e.g., SAscore) and synthetic realism metrics (e.g., PReal from AnoChem) to prioritize candidates with practical synthetic routes [15]. Following synthesis, comprehensive characterization includes: (1) determination of binding affinity through biophysical assays (SPR, ITC); (2) functional activity assessment in cell-based assays; (3) structural validation through X-ray crystallography or NMR when possible; (4) evaluation of key drug-like properties (solubility, metabolic stability, permeability); and (5) selectivity profiling against related targets. This rigorous validation framework ensures that scaffold-hopped compounds not only maintain target engagement but also exhibit favorable molecular medicinal properties for further development.

The systematic classification of scaffold hopping approaches into heterocycle replacements, ring opening/closure, peptidomimetics, and topology-based modifications provides a strategic framework for navigating chemical space in contemporary drug discovery. This four-tiered taxonomy encompasses a spectrum of structural modification ranging from conservative bioisosteric replacements to transformative topology-based redesign, offering medicinal chemists a structured methodology for pursuing varying degrees of structural novelty. The hierarchical nature of this classification system reflects the inherent trade-off between structural novelty and success probability, with heterocycle replacements offering higher probabilities of maintained activity but lower degrees of novelty, while topology-based hops promise greater structural innovation with correspondingly higher risk.

The strategic implementation of scaffold hopping continues to evolve through integration with advanced computational methodologies including artificial intelligence, graph-based representations, and multi-parameter optimization algorithms [2]. These technological advances enable more effective navigation of vast chemical spaces, identification of non-obvious scaffold relationships, and prediction of synthetic accessibility—collectively enhancing the efficiency and success of scaffold hopping campaigns. Furthermore, the emergence of open-source platforms such as ChemBounce increases accessibility to sophisticated scaffold hopping capabilities for the broader research community [15].

As drug discovery faces increasingly challenging targets, including protein-protein interactions, allosteric sites, and undrugged target classes, the strategic application of scaffold hopping will continue to provide critical pathways to viable chemical matter. By systematically exploring structural diversity while conserving essential pharmacophoric elements, scaffold hopping represents a powerful approach for expanding druggable chemical space, overcoming developmental liabilities, and establishing robust intellectual property positions. The continued refinement and application of scaffold hopping methodologies will undoubtedly contribute to the future discovery and development of therapeutic agents addressing unmet medical needs.

Scaffold hopping, a strategy first coined by Gisbert Schneider in 1999, has become an integral approach in medicinal chemistry for generating novel, patentable drug candidates with potentially improved properties [15]. This innovative methodology involves modifications to the core structure of an existing bioactive molecule while preserving essential pharmacophoric elements, thereby creating new molecular entities with enhanced pharmacodynamic (PD), physiochemical, and pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles (P3 properties) [1]. The fundamental principle, as articulated by Nobel Laureate Sir James Whyte Black, states that "the most fruitful basis of the discovery of a new drug is to start with an old drug" [1]. This review demonstrates how systematic scaffold hopping has successfully led to the development of three clinically important drugs: Vadadustat, Bosutinib, and Sorafenib, while analyzing the molecular modulations that enabled their therapeutic success.

The strategic importance of scaffold hopping extends beyond mere chemical novelty. This approach addresses critical challenges in drug discovery, including intellectual property constraints, suboptimal physicochemical properties, metabolic instability, toxicity issues, and insufficient efficacy [1] [15]. By enabling systematic exploration of unexplored chemical space while maintaining biological activity through conserved pharmacophores, scaffold hopping represents a powerful tool for hit expansion and lead optimization in modern pharmaceutical research [15]. The case studies presented herein exemplify how calculated structural variations of known molecular templates can yield differentiated therapeutic agents with distinct clinical advantages.

Case Study 1: Vadadustat

Drug Profile and Therapeutic Indication

Vadadustat (marketed as Vafseo) is an oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PH) inhibitor approved for the treatment of anemia due to chronic kidney disease (CKD) in adults who have been receiving dialysis for at least three months [17] [18]. This innovative therapeutic activates the physiological response to hypoxia, stimulating endogenous production of erythropoietin and consequently increasing hemoglobin and red blood cell production to manage renal anemia [19]. Vadadustat received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in March 2024 and is currently approved in 37 countries, representing a significant advancement in the management of CKD-associated anemia [17] [18] [19].

Scaffold Hopping Strategy and Molecular Design

Vadadustat originated from scaffold hopping of Roxadustat (IIIa), another HIF-PH inhibitor developed by FibroGen in collaboration with AstraZeneca and Astellas [1]. The key molecular modification involved replacing the isoquinoline core of Roxadustat with an imidazolopyrazine scaffold while strategically retaining the critical 3-hydroxylpicolinoylglycine pharmacophore essential for binding to the catalytic site of PHD2 [1]. This pharmacophore facilitates bidentate coordination bonding with ferrous ions and ionic bonding between the glycine carboxylate and the active site residues of PHD2 [1]. The scaffold transition significantly altered the molecular framework while preserving these essential interactions, demonstrating a sophisticated application of heterocycle replacement (1°-scaffold hopping) strategy to generate novel intellectual property space with maintained biological activity.

Experimental Data and Clinical Evaluation

Recent clinical investigations have focused on optimizing vadadustat dosing regimens in target populations. The FO2CUS trial, an open-label, active-controlled study published in the American Journal of Kidney Disease, evaluated 456 hemodialysis patients randomized to vadadustat 600mg, vadadustat 900mg, or a long-acting erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (Mircera) [19]. The primary efficacy endpoint was mean change in hemoglobin between baseline and the primary evaluation period (weeks 20-26), with secondary endpoints assessing longer-term efficacy (weeks 46-52) [19].

Table 1: Key Clinical Findings from Vadadustat Trials

| Trial Name | Patient Population | Primary Endpoint | Key Findings | Safety Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FO2CUS [19] | 456 hemodialysis patients | Mean Hb change (weeks 20-26) | Non-inferiority to ESA demonstrated | Most common adverse reactions: hypertension (≥10%) and diarrhea (≥10%) |

| VOCAL [17] [18] | ~350 patients (planned) | Change in hemoglobin | Ongoing post-marketing study | Boxed warning for thrombotic vascular events including MACE |

Akebia has further initiated the VOCAL post-marketing study in conjunction with DaVita dialysis clinics to evaluate potential benefits of three-times-weekly dosing of vadadustat compared to standard erythropoiesis-stimulating agents [17] [18]. This open-label, active-controlled trial employing 1:1 randomization aims to enroll approximately 350 patients across 18 hemodialysis clinics, with participation lasting up to 33 weeks including screening, treatment, and safety follow-up [17]. The study includes a specialized sub-study investigating red blood cell phenotypes to better understand vadadustat's impact on RBC quality parameters such as deformability, resistance to oxidative stress, and metabolomics compared to ESA treatment [17] [18].

Case Study 2: Bosutinib

Drug Profile and Therapeutic Indication

Bosutinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) targeting the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [20]. Approved by the European Medicines Agency in March 2013, bosutinib is indicated for adult patients in all phases of Ph+ CML previously treated with one or more TKIs where imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate treatment options [20]. The drug has subsequently received approval as first-line therapy in 2018, expanding its clinical utility [20].

Scaffold Hopping Strategy and Molecular Design

Bosutinib exemplifies the sequential scaffold hopping approach applied across multiple generations of TKIs. As a second-generation TKI, it was developed through structural modifications of the imatinib scaffold, specifically designed to overcome resistance mechanisms that emerged with first-generation inhibitors [20]. The molecular design incorporates strategic alterations to the heterocyclic core system while preserving key elements necessary for ATP-competitive binding to the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain. This scaffold optimization enhanced target specificity and improved the resistance profile, particularly against common mutations that confer resistance to imatinib [20].

Experimental Data and Clinical Evaluation

A multi-center, retrospective, non-interventional chart review study conducted across 10 hospitals in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands evaluated the real-world effectiveness and safety of bosutinib in 87 heavily pretreated CML patients [20]. The patient population had median disease duration of 7.1 years and predominantly required bosutinib as third-line (38%) or fourth-line (51%) TKI therapy due to resistance or intolerance to prior treatments [20].

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes of Bosutinib in Chronic Phase CML Patients [20]

| Response Parameter | Response Rate (%) | Additional Context |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Cytogenetic Response (CCyR) | 67% | Cumulative rate in chronic phase patients |

| Major Molecular Response (MMR) | 55% | Cumulative rate in chronic phase patients |

| Overall Survival (1 year) | 95% | Median follow-up of 21.5 months |

| Overall Survival (2 years) | 91% | Median follow-up of 21.5 months |

| Treatment Discontinuation | 38% | Due to lack of efficacy (17%), adverse events (14%), death (2%), other (5%) |

The study demonstrated that bosutinib achieved substantial response rates despite the heavily pretreated population, with a median treatment duration of 15.6 months [20]. Safety analysis revealed that 94% of patients experienced at least one adverse event, most commonly diarrhea (52%), though the treatment was generally tolerable with appropriate management [20]. This real-world evidence confirms that bosutinib serves as an effective treatment option for CML patients in chronic phase who have developed resistance or intolerance to prior TKI therapies.

Case Study 3: Sorafenib

Drug Profile and Therapeutic Indication

Sorafenib (marketed as Nexavar) represents a milestone in molecularly targeted therapy as the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and the first systemic therapy demonstrating significant overall survival benefit in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [21] [22] [23]. This orally active multikinase inhibitor blocks multiple kinase targets including VEGF receptor 2 and 3 kinases, PDGF receptor β kinase, Raf kinase (RAF-1), FLT-3, c-Kit, and RET receptor tyrosine kinases [21] [22]. Sorafenib received FDA approval in 2005 for RCC and in 2007 for HCC, establishing a new standard of care for these advanced malignancies [22] [23].

Scaffold Hopping Strategy and Molecular Design

Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) was discovered through a targeted RAF kinase discovery strategy employing high-throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry [23]. Bayer Pharmaceuticals, in collaboration with Onyx Pharmaceuticals, screened 200,000 compounds from medicinal chemistry libraries using a RAF kinase biochemical assay to identify molecules with activity against recombinant activated RAF kinase [23]. The lead optimization process involved structure-activity relationship evaluation and rapid parallel synthesis techniques, ultimately yielding the final compound featuring a diphenylurea moiety, a 4-pyridyl ring occupying the ATP binding pocket, and a lipophilic trifluoromethyl phenyl ring inserting into a hydrophobic pocket within the RAF-1 catalytic domain [23]. This strategic molecular architecture enables potent inhibition of both the tumor cell proliferation (via RAF kinase inhibition) and tumor angiogenesis (via VEGFR and PDGFR inhibition) [22].

Experimental Data and Clinical Evaluation

The efficacy and safety profile of sorafenib has been established through multiple pivotal clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance studies. The Phase III SHARP (Sorafenib HCC Assessment Randomized Protocol) trial demonstrated that sorafenib significantly improved overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, with median survival of 10.7 months compared to 7.9 months with placebo, representing a 44% improvement [22]. The median time to progression was also significantly longer in sorafenib-treated patients (5.5 months versus 2.8 months) [22].