Quantum Mechanics in Metabolic Stability Prediction: From Fundamental Principles to Quantum Computing

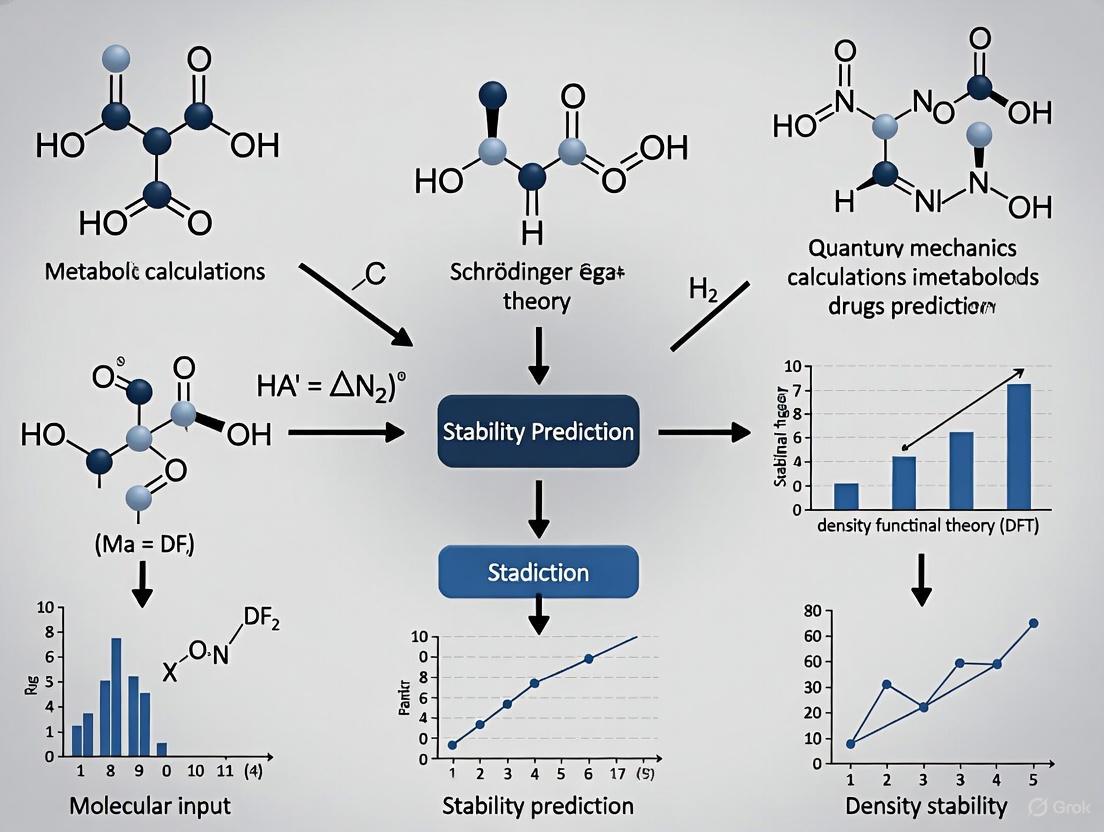

This article provides a comprehensive examination of quantum mechanical (QM) applications in predicting metabolic stability, a critical parameter in drug discovery.

Quantum Mechanics in Metabolic Stability Prediction: From Fundamental Principles to Quantum Computing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of quantum mechanical (QM) applications in predicting metabolic stability, a critical parameter in drug discovery. It explores foundational QM methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and QM/MM, detailing their use in modeling hydrolysis reactions and enzyme-substrate interactions. The content covers practical implementation, troubleshooting for computational challenges, and validation through case studies and performance benchmarks. It also highlights the emerging role of quantum computing and machine learning integration, offering researchers and drug development professionals a roadmap for leveraging QM to accelerate lead optimization and address interspecies metabolic variations.

The Quantum Mechanical Basis of Drug Metabolism

Why Classical Methods Fall Short in Metabolic Prediction

Accurate prediction of metabolic stability—how quickly a compound is broken down in the body—is a critical determinant of success in drug discovery. Unexpected metabolism accounts for a significant proportion of late-stage drug candidate failures and even withdrawal of approved drugs [1]. For decades, classical computational methods have served as the primary tools for predicting these outcomes, yet they consistently fall short of the accuracy and reliability required for confident decision-making. These classical approaches, predominantly based on quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and classical molecular dynamics, operate under linear assumptions that fundamentally misrepresent the underlying non-linear biochemistry of metabolic processes [2]. The limitations are not merely incremental but foundational, creating bottlenecks in the development of new therapeutics.

The emergence of quantum mechanical (QM) methods presents a paradigm shift in metabolic stability prediction. By modeling electrons and their interactions explicitly, QM calculations provide access to the electronic structure properties and reaction energetics that dictate metabolic transformations. This review examines the fundamental limitations of classical approaches and demonstrates how quantum mechanical methods, both alone and integrated with machine learning, are providing unprecedented accuracy in predicting metabolic fate, thereby opening new avenues for rational drug design.

Fundamental Limitations of Classical Prediction Methods

Classical prediction methods face insurmountable hurdles rooted in their simplified representation of molecular systems and their inability to accurately model reaction mechanisms.

The Oversimplification of Biochemical Reality

Classical methods, including classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and many machine learning models, rely on pre-parameterized force fields and statistical correlations that ignore the quantum nature of chemical reactivity.

- Ignoring Electronic Effects: Classical force fields cannot accurately represent the formation and breaking of chemical bonds, transition states, or reaction pathways because they do not model electron behavior. Metabolic reactions are fundamentally electronic processes.

- Linear Assumptions in a Non-linear System: Statistical models like polygenic scores (PGS) operate as black boxes, using linear associations to predict phenotypes generated by underlying non-linear biochemistry [2]. This limits their interpretability and generalizability.

- Data Dependency and Reproducibility Issues: Machine learning models are highly dependent on the quality and scope of their training data. Models trained on data from different laboratories with varying experimental conditions often suffer from reproducibility problems and limited predictive power for novel chemical structures [3].

The Energetic Implausibility of Classical Cellular Computation

A profound theoretical limitation challenges the very foundation of classical information processing in biology. Cellular energy budgets of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes fall orders of magnitude short of the power required to maintain classical states of protein conformation and localization at the atomic (Å) and femtosecond (fs) scales [4]. This suggests that the assumption that cellular biochemistry implements classical information processing is energetically implausible. Instead, it has been proposed that decoherence is limited, and bulk cellular biochemistry may implement quantum information processing [4]. This insight fundamentally undermines the premise of purely classical models of cellular metabolism.

Table 1: Core Limitations of Classical Metabolic Prediction Paradigms

| Classical Paradigm | Core Limitation | Impact on Predictive Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Molecular Dynamics | Pre-parameterized force fields cannot model bond breaking/formation or transition states. | Inability to accurately predict reaction pathways or activation energies for novel compounds. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Relies on linear correlations and cannot capture the quantum mechanical nature of reactivity. | Limited extrapolation capability and poor performance for structures outside training set. |

| Classical Machine Learning | Treats metabolism as a black box, ignoring underlying mechanistic principles and enzyme specificity. | Models lack interpretability; predictions can be unreliable without large, high-quality datasets. |

The Quantum Mechanical Paradigm: A Mechanistic Foundation

In stark contrast to classical methods, quantum mechanical (QM) approaches calculate the properties of molecules from first principles by solving approximations of the Schrödinger equation, explicitly dealing with electrons and nuclei.

Unprecedented Accuracy for Reaction Thermodynamics

QM methods, particularly those based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting the thermodynamic parameters of biochemical reactions. An extensive benchmark study calculated the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔGᵣ'°) for 300 diverse biological reactions using multiple DFT exchange-correlation functionals [5]. The results were groundbreaking, achieving a mean absolute error of 1.60–2.27 kcal/mol after calibration, which is near the benchmark "chemical accuracy" of 1 kcal/mol and comparable to errors in experimental measurements themselves [5]. This level of accuracy is unprecedented for a computational method applied across a wide range of metabolic reactions.

Direct Modeling of Reactivity and Metabolism

QM methods directly compute the properties that govern metabolic stability, moving beyond correlation to causation.

- Predicting Sites of Metabolism: By calculating electronic properties like partial charges, frontier molecular orbital energies, and hydrogen abstraction energies, QM can identify the atoms within a molecule most susceptible to enzymatic attack.

- Modeling Reaction Pathways: QM can simulate the entire hydrolysis reaction coordinate for esters, providing energy barriers that correlate directly with experimental half-lives [3]. This allows for the discrimination of relative metabolic stability between similar compounds.

- Incorporating Solvation and pH: Modern implicit solvation models (e.g., SMD) and the ability to calculate the major microspecies at a given pH allow QM calculations to closely mimic physiological conditions [5].

Quantitative Comparison: Classical vs. Quantum Performance

The theoretical advantages of QM methods are borne out in direct, quantitative comparisons with classical machine learning (ML) approaches.

Table 2: Performance Benchmark: Machine Learning vs. Quantum Mechanics for Metabolic Stability

| Method | Dataset | Key Metric | Performance Result | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML (Consensus Model) [3] | 656 ester-containing molecules | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | 0.695 (External Validation) | High throughput; rapid screening of large libraries. |

| Quantum Mechanics [3] | Ester hydrolysis | Energy Gap Calculation | Successfully discriminated relative metabolic stability ranks. | Mechanistic insight; no training data required. |

| Quantum-Enhanced ML (Quantum Metabolic Avatar) [6] | Personal metabolic time-series | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | ~30% reduction in RMSE vs. classical model; ~76% lower RMSE with outliers. | Superior with limited data and resilience to outliers. |

| QM/ML Hybrid (Optibrium) [1] | Drug-like compounds | Sensitivity & Precision in Metabolite ID | Higher precision than other methods for predicting in vivo metabolite profiles. | Combines accuracy and practicality for drug discovery. |

The data reveals a clear pattern: while classical ML can achieve good performance with sufficient, high-quality data, QM-based approaches provide a fundamental mechanistic advantage. The hybrid approach, which leverages the strengths of both, represents the state of the art.

Protocols for Quantum-Enhanced Metabolic Stability Prediction

Protocol 1: Predicting Ester Metabolic Stability via QM Energy Gap

This protocol details the use of quantum mechanical cluster approaches to predict the metabolic stability of ester-containing compounds through hydrolysis energy calculations [3].

Principle: The rate-limiting step for esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis is the nucleophilic attack or the breaking of the carbonyl bond. The energy gap between the reactant and the transition state (activation energy) correlates with the experimental half-life.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Quantum chemistry package (e.g., NWChem, Gaussian, ORCA).

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster.

- Initial Structure: 3D molecular structure of the ester compound in SDF or MOL2 format.

Procedure:

- Generate 3D Geometry: If starting from a SMILES string, use a tool like RDKit or Open Babel to generate an initial 3D molecular structure.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the reactant ester molecule using a DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP) and a basis set (e.g., 6-31G*). Employ an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD) to simulate aqueous solution.

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized geometry to confirm it is a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain thermal corrections to Gibbs free energy.

- Transition State Optimization: Locate and optimize the geometry of the transition state for the ester hydrolysis reaction. This often requires advanced techniques like QM/MM or a cluster model of the enzyme active site. Validate the transition state with a frequency calculation (one imaginary frequency).

- Energy Gap Calculation: Calculate the Gibbs free activation energy (ΔG‡) as the energy difference between the transition state and the reactant.

- Stability Ranking: Rank the metabolic stability of a series of compounds based on their calculated ΔG‡ values, with higher barriers indicating greater stability.

Protocol 2: QM/ML Hybrid for Comprehensive Metabolism Prediction

This protocol, based on industry practice (e.g., Optibrium's WhichEnzyme), combines QM-derived reactivity with ML-predicted enzyme accessibility for a holistic prediction [1].

Principle: The likelihood of a metabolite forming is a function of both the intrinsic chemical reactivity of a site (governed by QM) and the accessibility of that site to a specific enzyme (predicted by ML).

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: QM software (as in Protocol 1) and ML models (commercial like StarDrop or open-source).

- Databases: Curated datasets of metabolic reactions and associated enzyme substrates for model training.

Procedure:

- Quantum Mechanical Reactivity Modeling:

- For the drug candidate, perform a QM calculation (as in Protocol 1, steps 1-3) to obtain its electronic structure.

- Calculate reactivity descriptors (e.g., Fukui indices, partial charges, local softness) for every atom in the molecule to identify sites susceptible to oxidation, reduction, or conjugation.

- Generate a ranked list of potential Sites of Metabolism (SOMs) based on reactivity.

Machine Learning Accessibility Modeling:

- Input the molecular structure (e.g., as a fingerprint or graph) into trained ML models that predict which enzyme families (e.g., CYPs, UGTs) and specific isoforms are most likely to metabolize the compound.

- These models are trained on structural and physicochemical data to learn the substrate specificity of different enzymes.

Integration and Metabolite Prediction:

- Combine the QM-derived reactivity profile with the ML-predicted enzyme likelihoods.

- A "model of models" integrates these outputs to prioritize the most likely routes of metabolism. For example, a highly reactive site (from QM) on a molecule that is a predicted substrate for a high-activity enzyme (from ML) will be flagged as a major metabolic pathway.

- The output is a comprehensive and ranked prediction of the most probable metabolites, providing higher sensitivity and precision than either method alone [1].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Quantum-Enhanced Metabolic Prediction

| Item Name | Specifications / Examples | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | NWChem, Gaussian, ORCA, PySCF | Performs core quantum mechanical calculations, including geometry optimization, frequency analysis, and energy computation. |

| Implicit Solvation Model | SMD (Solvation Model based on Density), COSMO | Mimics the aqueous biological environment in calculations, critical for obtaining physiologically relevant energies. |

| Density Functional (Functional/Basis Set) | B3LYP/6-31G, PBE0/6-311++G*, ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP | The exchange-correlation functional and basis set combination that determines the accuracy and computational cost of DFT. |

| Metabolic Stability Dataset | Human Plasma/Blood half-lives (e.g., 656 ester molecules [3]); HLM/MLM % remaining [7] | Provides experimental data for validating computational predictions and training machine learning models. |

| Metabolism Prediction Platform | StarDrop Metabolism Module, GLORYx, SMARTCyp | Integrated software that often combines QM and ML methods to provide user-friendly predictions of metabolic sites and metabolites. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Multi-core nodes with significant RAM and fast interconnects. | Provides the necessary computational power to run QM calculations, which are resource-intensive and cannot be performed on standard desktop computers. |

The failure of classical methods to accurately predict metabolic stability is a consequence of their inherent limitations in modeling the quantum mechanical reality of chemical reactivity. As demonstrated, QM methods provide a foundational, mechanistic approach that achieves accuracy comparable to experimental measurement. The emerging hybrid paradigm, which synergizes the principled power of QM with the scalable pattern recognition of ML, represents the future of metabolic prediction. This powerful combination finally provides researchers with the tools to design drugs with optimal metabolic stability intentionally, thereby reducing late-stage attrition and accelerating the delivery of new therapeutics.

Core Quantum Mechanics Principles for Drug Discovery

Quantum mechanics (QM) revolutionizes drug discovery by providing precise molecular insights unattainable with classical methods. Unlike classical mechanics, which treats atoms as point masses with empirical potentials, QM explicitly models electronic structure, enabling accurate prediction of chemical properties, binding affinities, and reaction mechanisms critical for pharmaceutical development. The fundamental framework for QM is defined by the Schrödinger equation, which describes the behavior of matter and energy at atomic and subatomic levels, incorporating essential phenomena such as wave-particle duality, quantized energy states, and probabilistic outcomes. For a single particle in one dimension, the time-independent Schrödinger equation is expressed as:

Ĥψ = Eψ

where Ĥ is the Hamiltonian operator (total energy operator), ψ(x) is the wave function (probability amplitude distribution), and E is the energy eigenvalue [8].

In computational drug design, QM methods have become indispensable for modeling electronic interactions where classical approaches lack precision, particularly for simulating protein-ligand interactions, predicting metabolic stability, and calculating reaction energies for metabolic processes [8] [9] [10]. The ability to accurately predict these properties at the quantum level enables researchers to optimize drug candidates for improved efficacy, stability, and safety profiles before synthesizing compounds, significantly accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Quantum Principles

The Quantum Mechanical Framework

Quantum chemistry applies the principles of quantum mechanics to chemical systems, focusing particularly on solving the electronic Schrödinger equation for molecules. The fundamental challenge arises from electron correlation effects and the computational complexity of exactly solving for many-electron systems [8] [11]. The Hamiltonian operator includes kinetic and potential energy terms:

Ĥ = -ℏ²/2m∇² + V(x)

where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, m is the particle mass, ∇² is the Laplacian operator, and V(x) is the potential energy function [8].

For practical application to molecular systems, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation is essential, which assumes stationary nuclei and separates electronic and nuclear motions:

Ĥₑψₑ(r;R) = Eₑ(R)ψₑ(r;R)

where Ĥₑ is the electronic Hamiltonian, ψₑ is the electronic wave function, r and R are electron and nuclear coordinates, and Eₑ(R) is the electronic energy as a function of nuclear positions [8]. This separation makes computational quantum chemistry feasible by focusing on electronic structure for fixed nuclear arrangements.

Key Quantum Chemical Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Major Quantum Mechanical Methods in Drug Discovery

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Applications in Drug Discovery | Computational Scaling | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Models electron density ρ(r) via Kohn-Sham equations [8] | Binding energy calculations, reaction mechanism studies, spectroscopic property prediction [8] [5] | O(N³) | Accuracy depends on exchange-correlation functional; struggles with dispersion forces [8] |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wavefunction approach using single Slater determinant [8] | Baseline electronic structures, molecular geometries, dipole moments [8] | O(N⁴) | Neglects electron correlation; underestimates binding energies [8] |

| Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) | Combines QM region with MM environment [8] [9] | Enzymatic reaction modeling, metabolic pathway analysis [9] | Depends on QM region size | Boundary artifacts; computational cost depends on QM region size [9] |

| Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) | Divides system into fragments; calculates interactions [8] | Large biomolecular systems, protein-ligand binding [8] | O(N²) to O(N³) | Fragment division challenges; lower accuracy for strongly interacting fragments [8] |

Quantum Protocols for Metabolic Stability Prediction

Protocol 1: DFT Approach for Ester Hydrolysis Prediction

Application Note: This protocol details the use of Density Functional Theory (DFT) to predict the metabolic stability of ester-containing compounds via hydrolysis energy calculations, particularly relevant for prodrug and soft-drug design [9].

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Computational Resources for QM Metabolic Stability Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Application/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, NWChem [8] [10] [5] | Performing DFT and other QM calculations |

| Molecular Modeling | RDKit, Chemaxon [5] | Generating 3D molecular geometries from SMILES strings |

| Solvation Models | SMD, COSMO [10] [5] | Modeling aqueous solution environments for metabolic reactions |

| Basis Sets | 6-31G, 6-311++G* [10] [5] | Describing molecular orbitals in QM calculations |

| Computational Hardware | High-performance computing clusters [5] | Handling computationally intensive QM simulations |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

System Preparation:

Conformational Sampling:

- Perform conformational analysis to identify low-energy conformers for each compound.

- Select representative conformers for QM calculations to ensure comprehensive coverage of the conformational space.

Quantum Chemical Calculations:

- Employ density functional theory with appropriate functionals (e.g., B3LYP-D3) and basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) for geometry optimization [9] [5].

- Include implicit solvation models (e.g., SMD) to represent aqueous physiological environment [5].

- Conduct frequency calculations to confirm stationary points and obtain thermodynamic corrections.

Transition State Modeling:

- Locate transition states for the ester hydrolysis reaction using appropriate algorithms (e.g., QST2, QST3).

- Verify transition states with exactly one imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

Energy Calculation:

- Calculate activation energies (ΔG‡) and reaction energies (ΔGᵣ) for the hydrolysis process.

- Compare energy barriers with experimental half-life data to establish correlation models.

Validation:

- Validate computational protocol against experimental metabolic stability data for known compounds.

- Refine computational parameters based on validation results to improve predictive accuracy.

The workflow for this protocol can be visualized as follows:

DFT Metabolic Stability Prediction Workflow

Protocol 2: QM/MM for Enzymatic Metabolism Prediction

Application Note: This protocol describes a QM/MM approach to model drug metabolism by enzymes such as carboxylesterases, providing atomistic insight into metabolic transformations and enabling prediction of metabolic stability ranks [9].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Obtain crystal structure of the metabolic enzyme (e.g., carboxylesterase) from Protein Data Bank or generate via homology modeling.

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and ensuring proper charge states.

System Partitioning:

- Define QM region to include substrate (drug molecule) and key catalytic residues (typically 50-200 atoms).

- Treat the remaining protein and solvent environment with molecular mechanics using force fields like AMBER or CHARMM.

Equilibration:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulation of the entire system to equilibrate the structure.

- Confirm stability of the enzyme-substrate complex before QM/MM calculations.

Reaction Pathway Mapping:

- Use string method or nudged elastic band approaches to identify minimum energy path for the metabolic reaction.

- Optimize reactants, products, and transition states along the reaction coordinate.

Energy Calculation:

- Calculate reaction energy profiles using high-level QM methods (e.g., DFT) for the QM region.

- Perform vibrational analysis to obtain thermodynamic contributions.

Metabolic Stability Ranking:

- Correlate calculated energy barriers with experimental metabolic half-lives.

- Use established correlations to predict metabolic stability of novel compounds.

The QM/MM partitioning strategy is illustrated below:

QM/MM System Partitioning Strategy

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Performance of QM Methods

Table 3: Accuracy of Quantum Mechanical Methods for Metabolic Reaction Energy Prediction

| QM Method | Functional/Basis Set | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Reaction Types Tested | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT | B3LYP/6-31G* with SMD solvation | 1.60-2.27 | Diverse metabolic reactions | [5] |

| DFT | Various functionals with calibration | ~1.50 | Central carbon metabolism | [5] |

| DFT | B3LYP/6-31G* with COSMO | 1.0 (hydration reactions) | Isomerization, hydration, C-C cleavage | [10] |

| DFT | B3LYP/6-31G* with 10 explicit waters + COSMO | 2.5 (isomerization reactions) | Isomerization, hydration, C-C cleavage | [10] |

Correlation with Experimental Data

Quantum mechanical methods show remarkable accuracy in predicting thermodynamic parameters of metabolic reactions, with mean absolute errors often approaching the benchmark chemical accuracy of 1 kcal/mol [5]. This high accuracy enables reliable prediction of metabolic stability trends and reaction energies directly from first principles. The performance varies by reaction type, with isomerization and group transfer reactions typically showing higher accuracy than reactions involving multiply charged anions [10].

When applied to ester-containing compounds, QM calculations of hydrolysis energy barriers successfully discriminate relative metabolic stability ranks, complementing machine learning approaches [9]. The energy gaps calculated for esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions provide direct insight into the structural features governing metabolic stability, enabling rational design of compounds with optimized pharmacokinetic profiles.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Quantum Computing in Metabolic Modeling

Emerging quantum algorithms show potential for accelerating metabolic network simulations, with recent demonstrations applying quantum interior-point methods to flux balance analysis of core metabolic pathways like glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [12]. These approaches leverage quantum singular value transformation for matrix inversion, a computationally demanding step in metabolic modeling, suggesting a pathway for quantum advantage in analyzing large-scale biological networks as quantum hardware matures [12].

Integration with Machine Learning

Hybrid approaches that combine quantum mechanics with machine learning are emerging as powerful strategies for metabolic stability prediction. While QM provides accurate physics-based parameters, machine learning models can leverage these parameters along with structural descriptors to build predictive models with enhanced accuracy and coverage [9]. This synergistic approach combines the fundamental insights from QM with the pattern recognition capabilities of machine learning, potentially offering the best of both paradigms for drug discovery applications.

The integration of these methodologies is particularly valuable for high-throughput screening in early drug development, where rapid assessment of metabolic stability can prioritize compounds for synthesis and experimental testing. As both quantum mechanical methods and machine learning algorithms continue to advance, their convergence is expected to play an increasingly important role in accelerating and improving the drug discovery process.

In the field of drug discovery, predicting metabolic stability is a critical challenge, as it directly influences a compound's pharmacokinetic profile, including its half-life, clearance, and oral bioavailability [7] [13]. The extreme complexity of metabolic pathways, primarily mediated by enzymes such as cytochrome P450, has made accurate in silico evaluation a long-standing goal [13]. While traditional machine learning models have shown utility, they often operate as "black boxes" and can struggle with generalizability across diverse chemical spaces [13].

Quantum mechanics (QM) offers a foundational approach to this problem by modeling the electronic structures and energy barriers that govern chemical reactivity, thereby providing a more mechanistic understanding of metabolic reactions [14]. This application note details how QM calculations, particularly for ester hydrolysis, are being integrated with modern machine learning frameworks to create more predictive, transparent, and reliable models for metabolic stability prediction, ultimately supporting more efficient lead optimization [15] [14].

QM Applications in Ester Hydrolysis Modeling

Ester hydrolysis is a ubiquitous metabolic reaction for esters and polyesters, significantly impacting the stability and environmental fate of numerous compounds [14]. The base-catalyzed hydrolysis of esters is a stepwise addition-elimination mechanism where the rate-limiting step is typically the nucleophilic attack of a hydroxide ion on the carbonyl carbon of the ester, leading to the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate [14].

QM Protocols for Reaction Profiling

QM calculations enable researchers to profile this reaction pathway and calculate the activation energy ((Ea)), a key determinant of the hydrolysis rate constant ((kb)).

Protocol: Calculating Activation Energy for Ester Hydrolysis

- System Preparation: Construct molecular structures of the reactant (ester and hydroxide ion) and the tetrahedral intermediate.

- Geometry Optimization: Use density functional theory (DFT), such as the Dmol3 module in Materials Studio, to perform geometry optimization for both the reactant (R) and the intermediate [14].

- Transition State Search: Locate the transition state (TS), which represents the saddle point on the potential energy surface between the reactant and the intermediate.

- Energy Calculation: The activation energy ((Ea)) is calculated as the energy difference between the transition state and the reactant [14]. According to the Arrhenius equation, this (Ea) is directly related to the hydrolysis rate constant.

Studies have established a linear correlation between DFT-calculated (Ea) and experimental logarithmic rate constants ((\log k{b,EXP})), validating the QM approach for predicting hydrolysis rates [14].

Visualizing the Hydrolysis Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the concerted, cyclic transition state for neutral ester hydrolysis involving multiple water molecules, a mechanism supported by QM calculations [16].

Diagram 1: QM energy profile for ester hydrolysis.

Recent single-molecule force spectroscopy studies have revealed that ester hydrolysis is chemically labile yet mechanically stable, with its rate being surprisingly insensitive to applied forces in the 80-200 pN range. QM calculations attribute this to the force-insensitive nature of both the tetrahedral intermediate rupture and its formation, which is the rate-limiting step [17].

Integration of QM with Machine Learning Frameworks

The integration of QM-derived features into machine learning models is a powerful strategy for enhancing metabolic stability prediction. The high computational cost of pure QM methods can be a bottleneck for large virtual libraries. To address this, deep learning models are being trained to learn the relationship between molecular structure and QM-calculated properties.

Deep Learning for Hydrolysis Rate Prediction

Protocol: Autoencoder Model for Ester Hydrolysis Prediction

- Data Representation: Input the Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings of esters and their partial charges [14].

- Data Augmentation: Use SMILES enumeration to artificially expand the training dataset, improving model robustness [14].

- Model Training: Train an autoencoder (AE) model with an attention mechanism. The model learns to compress the input into a latent code that can accurately predict the hydrolysis rate constant.

- Model Validation: Compare the model's predictions against experimental data and established computational tools like SPARC. The AE model has been shown to outperform SPARC on the basis of root mean square error (RMSE) [14].

This approach allows for the rapid prediction of hydrolysis rates directly from molecular structure, bridging the gap between high-accuracy QM and high-throughput screening.

Advanced Metabolic Stability Prediction with GNNs

For broader metabolic stability prediction in liver microsomes, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent the state of the art. Models like MetaboGNN and TrustworthyMS leverage graph contrastive learning to learn robust molecular representations [15] [7].

Protocol: MetaboGNN for Liver Metabolic Stability

- Data Preparation: Use a high-quality dataset (e.g., from the 2023 South Korea Data Challenge for Drug Discovery) containing SMILES strings and corresponding human (HLM) and mouse (MLM) liver microsomal stability data (% parent compound remaining) [7].

- Graph Representation: Represent each molecule as a graph, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Pretraining: Employ graph contrastive learning (GCL) as a pretraining step. This self-supervised technique enhances model generalizability by learning to produce similar embeddings for different structural views of the same molecule [7].

- Multi-Task Training: Train the model to simultaneously predict HLM and MLM stability values. Explicitly incorporating the interspecies difference (HLM-MLM) as a learning target has been shown to boost predictive accuracy and provide insights into species-specific metabolic variations [7].

The recently proposed TrustworthyMS framework further addresses model trustworthiness by incorporating a molecular graph topology remapping mechanism to synchronize atom-bond interactions and employing Beta-Binomial uncertainty quantification to provide confidence estimates for its predictions [15].

The workflow below illustrates the integration of QM insights and experimental data into a predictive GNN model.

Diagram 2: Integrated QM-GNN workflow for metabolic stability prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 1: Key computational tools and resources for modeling metabolic reactions and stability.

| Tool/Resource Name | Function/Role in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dmol3 (Materials Studio) | A density functional theory (DFT) software package for calculating electronic properties and activation energies ((E_a)) of molecules [14]. | Predicting activation energies for ester hydrolysis and other metabolic reactions [14]. |

| Autoencoder (AE) Models | A deep learning architecture used to predict hydrolysis rates from SMILES strings and partial charges, enabling conditional molecular design [14]. | Predicting ester hydrolysis rate constants and generating structures with desired stability [14]. |

| MetaboGNN | A Graph Neural Network model incorporating graph contrastive learning and interspecies differences for liver microsomal stability prediction [7]. | Predicting metabolic stability in human and mouse liver microsomes with high accuracy (RMSE ~27.9) [7]. |

| TrustworthyMS | A GNN framework with dual-view contrastive learning and uncertainty quantification for reliable metabolic stability prediction [15]. | Providing predictions with confidence bounds, enhancing decision-making in lead optimization [15]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A method for interpreting machine learning model predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature [13]. | Identifying key molecular substructures (e.g., from MACCS or Klekota & Roth fingerprints) that positively or negatively influence predicted metabolic stability [13]. |

| MetStabOn Online Platform | A web service using machine learning to qualitatively evaluate metabolic stability (half-lifetime, clearance) for human, rat, and mouse data [18]. | Rapid, online classification of compound stability (low, medium, high) based on experimental data from ChEMBL [18]. |

The integration of quantum mechanics with advanced machine learning represents a paradigm shift in metabolic stability prediction. By providing a fundamental understanding of key reactions like ester hydrolysis, QM calculations ground computational models in physicochemical reality. This synergy is embodied in next-generation tools like MetaboGNN and TrustworthyMS, which leverage QM-inspired features, graph-based learning, and uncertainty quantification to deliver accurate, interpretable, and trustworthy predictions. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will become indispensable in accelerating the design of compounds with optimal metabolic profiles, thereby de-risking and streamlining the drug development pipeline.

Quantum mechanical (QM) methods provide a physics-based approach to computational chemistry, enabling researchers to model the electronic structures of molecules and molecular systems with high accuracy. Unlike classical molecular mechanics (MM), which treats atoms as point masses with empirical potentials, QM methods describe electrons explicitly, allowing for the modeling of electronic phenomena crucial for understanding chemical reactivity, binding, and metabolism [19] [20]. In the specific context of metabolic stability prediction, the electronic state of a molecule is a key determinant of its interaction with metabolic enzymes such as Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) [21]. This document details the application of four essential QM methods—Density Functional Theory (DFT), Hartree-Fock (HF), Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM), and the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method—within research workflows aimed at understanding and predicting drug metabolism.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of these four core QM methods, providing a guide for selecting the appropriate technique for a given application in metabolic research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Essential Quantum Mechanics Methods in Drug Discovery

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Typical System Size | Computational Scaling | Best Applications in Metabolic Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Models electron density; solves Kohn-Sham equations to find ground-state energy [19] [22]. | High accuracy for ground states; handles electron correlation; wide applicability for reactivity and spectra [19]. | Functional dependence; expensive for large systems; struggles with dispersion forces and excited states [19]. | ~100-500 atoms [19] | O(N³) [19] | Site of Metabolism (SOM) identification via Fukui functions; reactivity descriptor calculation [21] [22]. |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Approximates many-electron wavefunction as a single Slater determinant; uses self-consistent field (SCF) method [19] [20]. | Fundamental wavefunction theory; fast convergence; reliable baseline [19]. | Neglects electron correlation; poor for weak interactions (e.g., van der Waals); underestimates binding energies [19]. | ~100 atoms [19] | O(N⁴) [19] | Initial geometry optimization; molecular orbital analysis; starting point for higher-level methods [19]. |

| QM/MM | Hybrid approach combining QM for reactive region with MM for surroundings [19]. | Balances QM accuracy with MM efficiency; handles large biomolecular systems like enzyme active sites [19] [23]. | Complex setup; boundary artifacts; method-dependent accuracy [19]. | ~10,000 atoms (MM) + ~50-100 atoms (QM) [19] | O(N³) for QM region [19] | Modeling metabolic reactions in CYP450 active sites; detailed enzyme mechanism studies [19] [23]. |

| Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) | Divides large system into fragments; performs QM calculations on fragments and pairs [24] [25]. | Scalable to very large systems (proteins, DNA); provides detailed residue interaction energies (IFIEs) [24]. | Fragmentation complexity; approximates long-range effects [19] [24]. | Thousands of atoms [19] | O(N²) [19] | Protein-ligand binding affinity decomposition; identifying key "hot spot" residues in drug-enzyme complexes [24] [25]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Application Protocols

Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Reactivity Descriptor Calculation

DFT has become one of the most widely used QM methods due to its favorable balance of accuracy and computational cost. It determines molecular properties by solving the Kohn-Sham equations for the electron density, rather than the many-electron wavefunction [19] [22].

Protocol: Calculating Fukui Functions for Site of Metabolism (SOM) Prediction

System Preparation

- Obtain the 3D molecular structure of the compound of interest.

- Perform a preliminary conformational search using molecular mechanics (e.g., with MMFF94 or GAFF force fields) to identify low-energy conformers.

- Select the lowest-energy conformer for DFT analysis.

Geometry Optimization

- Use a quantum chemistry software package (e.g., Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA).

- Employ a hybrid functional such as B3LYP and a double-zeta basis set with polarization functions, such as 6-31G [26] [27].

- Run a geometry optimization calculation to converge the structure to a local energy minimum, confirming the absence of imaginary frequencies in a subsequent frequency calculation.

Single-Point Energy and Electron Density Calculation

- Using the optimized geometry, perform a single-point energy calculation with an augmented basis set (e.g., 6-311++G(d,p)) for higher accuracy [26].

- The output must include the electron density for the neutral (N), cationic (N-1), and anionic (N+1) species. This typically requires three separate calculations.

Fukui Function Analysis

- Analyze the output to calculate the Fukui indices. The condensed Fukui function for an atom k can be approximated using the electron population (e.g., from Natural Population Analysis, NPA):

- For electrophilic attack: ( fk^- = qk(N) - qk(N-1) )

- For nucleophilic attack: ( fk^+ = qk(N+1) - qk(N) )

- For radical attack: ( fk^0 = \frac{[qk(N+1) - q_k(N-1)]}{2} )

- Atoms with high Fukui function values are considered soft nucleophilic or electrophilic sites and are potential targets for CYP450-mediated oxidation [22].

- Analyze the output to calculate the Fukui indices. The condensed Fukui function for an atom k can be approximated using the electron population (e.g., from Natural Population Analysis, NPA):

Validation

- Compare predicted reactive sites with known experimental metabolite data for similar compounds.

- For further insight, generate an Electrostatic Potential (ESP) map to visualize electron-rich and electron-deficient regions on the molecular surface [26].

Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) Method for Protein-Ligand Interaction Analysis

The FMO method allows for ab initio quantum mechanical calculations on very large systems like proteins by dividing the system into smaller fragments and solving the quantum equations for each fragment and its pairs [24] [25].

Protocol: Decomposing Drug-CYP450 Interaction Energies with FMO-PIEDA

System Preparation and Fragmentation

- Obtain a crystal structure or a validated homology model of the CYP450 isoform complexed with your drug molecule (from PDB).

- Prepare the protein-ligand complex by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks.

- Fragment the system. A standard approach is to define each amino acid residue and the ligand as individual fragments.

FMO Calculation Setup

- Use software capable of FMO calculations, such as GAMESS or ABINIT-MP [24].

- Select a quantum mechanical method and basis set. A common choice is MP2/6-31G* , which provides a good description of electron correlation and is widely used for biomolecules [24].

- Execute the FMO calculation. The software will perform SCF calculations for all monomers and pairs.

Inter-Fragment Interaction Energy (IFIE) Analysis

- Analyze the output IFIEs, which represent the interaction energy between each fragment pair. Focus on the interaction energies between the ligand fragment and the surrounding protein residue fragments.

- High negative IFIE values indicate strong stabilizing interactions.

Pair Interaction Energy Decomposition Analysis (PIEDA)

- Perform PIEDA to decompose the IFIE into physically meaningful components [24]:

- ES (Electrostatic): Classical Coulomb interaction.

- EX (Exchange Repulsion): Pauli exclusion principle-based repulsion.

- CT+mix (Charge Transfer + Higher-Order Mixing): Orbital mixing and charge transfer effects.

- DI (Dispersion Interaction): van der Waals attraction.

- This decomposition helps identify the nature of key interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds are characterized by strong ES and CT+mix components).

- Perform PIEDA to decompose the IFIE into physically meaningful components [24]:

Identification of "Hot Spot" Residues

- Residues with the largest total IFIE (most negative) and significant energy components are identified as "hot spots" critical for binding. Mutating or designing ligands to target these residues can modulate binding affinity and potentially metabolic stability [25].

Integrated Workflow for Metabolism Prediction

The following diagram illustrates a proposed integrated research workflow that incorporates these QM methods into a comprehensive strategy for metabolic stability prediction.

Diagram: QM-AI Integrated Workflow for Metabolic Stability Prediction.

This workflow demonstrates how the methods can be chained: HF provides an optimized structure for DFT, which identifies reactive sites. These insights inform the setup of FMO calculations on drug-enzyme complexes, whose outputs can guide more detailed QM/MM simulations of the metabolic reaction itself. Finally, all quantum-derived descriptors can be fed into a machine-learning model for robust predictive modeling [28] [21].

Successful implementation of the protocols above requires a suite of software tools and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Category | Item | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | Quantum Chemistry Suites | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, Q-Chem [19] | Performs core QM calculations (DFT, HF, MP2). |

| FMO-Capable Software | ABINIT-MP, GAMESS [24] [25] | Enables FMO and PIEDA calculations on proteins. | |

| QM/MM Software | Amber, CHARMM, GROMACS with QM/MM plugins [19] [23] | Runs hybrid quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical simulations. | |

| Molecular Visualization & Analysis | PyMOL, VMD, GaussView [26] [27] | Prepares structures, visualizes results, and analyzes geometries. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Local clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, Google Cloud) [23] | Provides the computational power for expensive QM calculations. |

| Data Resources | Protein Structure Database | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [24] [23] | Source for experimental structures of metabolic enzymes (e.g., CYPs). |

| Quantum Chemical Datasets | FMODB, QM9, SCOP2-based FMO datasets [24] | Provides reference data for validation and machine learning. | |

| Specialized AI Tools | Metabolism Prediction Platforms | DeepMetab [21], BioTransformer [21], MetaPredictor [21] | AI/ML platforms that can utilize QM descriptors for end-to-end prediction. |

Linking Electronic Structure to Metabolic Stability Outcomes

Predicting the metabolic stability of small molecules is a critical challenge in drug discovery, as it directly influences a compound's pharmacokinetic profile, including its half-life, clearance, and oral bioavailability [7]. Metabolic stability refers to the susceptibility of a drug molecule to enzymatic modification, primarily in the liver, which often leads to its deactivation and excretion [7] [29]. While traditional predictive models rely on quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) or machine learning based on molecular structure alone, a more fundamental approach links metabolic outcomes to the molecule's underlying electronic structure. The thesis of this application note is that quantum mechanical (QM) calculations provide a non-empirical method to uncover the electronic determinants of metabolic reactions, thereby enabling more accurate and interpretable predictions of metabolic stability [30] [29]. By quantifying properties such as orbital energies, partial charges, and hydrogen abstraction energies, researchers can gain deep insights into the physicochemical drivers of metabolic liability.

Theoretical Foundation: Electronic Properties in Metabolism

A molecule's electronic state dictates its reactivity and its interactions with enzymatic active sites. Key electronic properties calculable through quantum chemistry include:

- Frontier Molecular Orbital Energies: The energies of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) indicate a molecule's propensity to participate in nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks, which are common in Phase I metabolism [29].

- Partial Atomic Charges: Electrostatic potential-derived charges help identify atoms susceptible to oxidation or nucleophilic addition.

- Bond Dissociation Energies (BDE): The energy required to cleave a specific bond, such as C-H or O-H, can be calculated to predict sites of hydroxylation or dealkylation [29].

- Hydrogen Abstraction Energy: A key descriptor for predicting sites of metabolism (SOMs) for reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, as a lower abstraction energy often correlates with higher metabolic lability [29].

Methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method enable these calculations for drug-sized molecules and their complexes with biological macromolecules [24] [30]. The FMO method, in particular, allows for quantum mechanical treatment of large systems like enzymes by dividing them into fragments and calculating inter-fragment interaction energies (IFIEs) [24]. Pair interaction energy decomposition analysis (PIEDA) can further dissect these interactions into electrostatic, exchange-repulsion, charge-transfer, and dispersion components, providing a detailed picture of how a drug molecule interacts with its metabolic enzyme [24].

Table 1: Key Electronic Properties and Their Role in Metabolic Stability

| Electronic Property | Computational Method | Relevance to Metabolic Stability |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO/LUMO Energy | DFT, HF | Predicts susceptibility to oxidation/reduction; high HOMO energy often indicates ease of oxidation. |

| Partial Atomic Charge | DFT, MP2 | Identifies electron-rich or electron-deficient atoms targeted by enzymes. |

| Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) | DFT | Low BDE for C-H or O-H bonds predicts potential sites of hydroxylation. |

| Hydrogen Abstraction Energy | DFT (e.g., SMARTCyp) | Primary descriptor for aliphatic and aromatic hydroxylation by CYP450s [29]. |

| Inter-Fragment Interaction Energy (IFIE) | FMO Method | Quantifies interaction energy between a drug molecule and specific enzyme residues [24]. |

Application Note: From Quantum Descriptors to Metabolic Stability Prediction

Integrated Workflow

The following diagram outlines a prototypical workflow for integrating quantum chemical calculations into metabolic stability prediction, illustrating the pathway from initial computational setup to final prediction output.

Case Study: MetaboGNN and the Role of Quantum Descriptors

Advanced machine learning models are beginning to leverage these foundational electronic principles. The MetaboGNN model, a state-of-the-art graph neural network for predicting liver metabolic stability, demonstrates how integrating structural and implicit electronic information can yield high predictive accuracy [7]. While it uses molecular graphs as direct input, the atomic and bond features within these graphs can be informed or supplemented by quantum chemical descriptors.

MetaboGNN was trained on a high-quality dataset from the 2023 South Korea Data Challenge for Drug Discovery, comprising 3,498 training molecules with measured stability in human and mouse liver microsomes (expressed as the percentage of the parent compound remaining after 30 minutes) [7]. The model achieved a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 27.91 for human liver microsomes (HLM) and 27.86 for mouse liver microsomes (MLM) [7]. A key innovation was the explicit incorporation of interspecies differences (HLM-MLM) as a learning target, which improved predictive accuracy. An attention-based analysis within the model can identify key molecular fragments associated with metabolic stability, which can be further rationalized and validated through quantum chemical analysis of those fragments' electronic properties [7].

Table 2: Representative Computational Approaches for Metabolism Prediction

| Tool/Method | Category | Brief Description | Use of Electronic Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMARTCyp | Combined Approach | Predicts CYP-mediated SOMs by combining precalculated DFT activation energies with accessibility descriptors [29]. | Uses DFT-derived hydrogen abstraction energy as a primary reactivity descriptor. |

| RS-Predictor | Combined Approach | Uses quantum chemical and topological descriptors with a support vector machine (SVM) to identify SOMs [29]. | Employs 392 quantum chemical atom-specific descriptors. |

| MetaSite | Combined Approach | Uses protein structural information, molecular interaction fields, and molecular orbital calculations [29]. | Incorporates molecular orbital calculations to estimate metabolic reactivity. |

| FMO-PIEDA | Quantum Chemical Method | Calculates inter-fragment interaction energies and decomposes them into components (electrostatics, dispersion, etc.) [24]. | Provides quantum mechanical insight into drug-enzyme binding interactions. |

| MetaboGNN | Machine Learning (GNN) | Predicts microsomal stability from molecular graphs; attention mechanisms highlight important substructures [7]. | Can be informed by quantum descriptors; outputs are interpretable in electronic terms. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Electronic Descriptors for a Small Molecule

This protocol details the steps to compute key electronic descriptors for a drug molecule using quantum chemical calculations.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum Chemistry Calculations

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software like GAMESS [24], Gaussian, or ORCA to perform the core electronic structure calculations. |

| Molecular Visualization/Editing Tool | Tools like Avogadro, GaussView, or PyMOL for building, visualizing, and preparing initial molecular geometries. |

| Computer Cluster/Cloud Resource | High-performance computing (HPC) resources are typically required due to the computational cost of QM methods. |

| Basis Set | A set of mathematical functions representing atomic orbitals (e.g., 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ). The choice affects accuracy and cost [24]. |

| Computational Method | The level of theory, such as Hartree-Fock (HF), Density Functional Theory (DFT), or Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) [24]. |

Procedure

- Geometry Preparation: Draw the 3D structure of the molecule of interest using a molecular editing tool. Perform an initial geometry optimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MMFF94) to obtain a reasonable starting conformation.

- Initial Quantum Optimization: At a low level of theory (e.g., HF/3-21G), optimize the molecular geometry to a local energy minimum. Confirm the absence of imaginary frequencies in a frequency calculation to ensure a true minimum.

- High-Level Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the optimized geometry, perform a more accurate single-point energy calculation at a higher level of theory, such as MP2/6-31G* [24] or a hybrid DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP) with a larger basis set (e.g., cc-pVDZ) [24].

- Descriptor Extraction: From the output of the high-level calculation, extract the following properties:

- Frontier Orbital Energies: Record the energy of the HOMO and LUMO.

- Atomic Charges: Calculate and record electrostatic potential-derived (ESP) charges for each atom.

- Bond Dissociation Energies (BDE): For a specific bond (e.g., C-H), calculate the energy difference between the parent molecule and the radicals formed upon homolytic bond cleavage.

- Data Analysis: Correlate the computed descriptors with experimental metabolic data. For instance, atoms with high HOMO energy or low C-H BDE are potential sites of metabolism.

Protocol 2: FMO Calculation for a Protein-Ligand Complex

This protocol outlines the process for applying the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method to study the interaction between a metabolic enzyme (e.g., a CYP450) and a drug molecule.

Procedure

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or via homology modeling. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms and assigning protonation states of amino acids appropriate for the physiological pH.

- Fragmentation: Fragment the protein-ligand system. A common scheme is to treat each amino acid residue and the ligand as individual fragments [24].

- FMO Calculation Setup: In quantum chemistry software like GAMESS or ABINIT-MP, configure the FMO calculation. Specify the method (e.g., FMO-MP2) and basis set (e.g., 6-31G*) [24]. Request the calculation of inter-fragment interaction energies (IFIEs) and, if available, a Pair Interaction Energy Decomposition Analysis (PIEDA).

- Execution and Analysis: Run the calculation on an HPC cluster. Upon completion, analyze the results:

- Identify the strongest interactions between the ligand and protein residues.

- Use PIEDA to determine the physical nature of the interaction (e.g., electrostatic, dispersion, charge-transfer) [24]. A strong electrostatic and charge-transfer component with a key catalytic residue (e.g., the heme in CYP450) can indicate a productive binding mode for metabolism.

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the FMO-based analysis, from system preparation to the final energy decomposition.

Implementing QM Methods for Metabolic Stability Assessment

Building QM Models for Esterase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis Reactions

Within drug discovery, the carboxylic ester functional group is a critical component in the design of pro-drugs and soft-drugs, making the understanding of their metabolic stability paramount [9]. Esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis is a primary metabolic pathway for these compounds, and the ability to predict its kinetics can significantly accelerate early-stage development [9]. While machine learning models offer high-throughput screening capabilities, quantum mechanical (QM) models provide a mechanistic, ab initio alternative that is not constrained by training data limitations and can deliver deeper insights into the reaction energetics and regioselectivity [9] [21]. This Application Note details the protocol for building QM models to predict the metabolic stability of ester-containing molecules via hydrolysis, contextualized within a broader research framework for metabolic stability prediction.

Theoretical Background and Rationale

The Role of Ester Hydrolysis in Drug Metabolism

Carboxylic ester hydrolysis, catalyzed by carboxylesterases, is a major metabolic pathway for numerous compounds [9]. Unlike cytochrome P450 enzymes, carboxylesterases are less prone to saturation and drug-drug interactions, making them attractive targets for predictable drug design [9]. The metabolic half-life of an ester-containing drug in human plasma or blood is a key experimental indicator of its metabolic stability, reflecting its systemic clearance rate [9].

Fundamental Quantum Mechanical Concepts

QM models for enzymatic reactions, such as ester hydrolysis, are built upon the principle of calculating the energy changes along the reaction pathway. The catalytic efficiency is often rationalized by the Transition State Theory (TST), which posits that enzyme catalysis primarily results from the stabilization of the transition state (TS) relative to the reactant state (RS) [31]. A core objective of QM modeling is therefore to calculate the energy barrier—the difference in energy between the RS and TS—which correlates with the reaction rate [9] [31]. For complex enzymatic systems, a full QM/MM (Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical) approach is often employed, where the quantum region, containing the reacting atoms, is embedded within a classical mechanical description of the enzyme and solvent [31].

Computational Methodology

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for building and applying a QM model for esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis.

System Preparation and Model Setup

Step 1: Active Site Model Definition The full enzyme-substrate system is typically too large for a pure QM treatment. A common and efficient strategy is to use a cluster approach [9]. This involves extracting a critical fragment of the enzyme's active site, including the catalytic residues (e.g., a catalytic triad), key hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors, and the substrate. This cluster model is then used for all subsequent QM calculations. The model should be large enough to capture essential interactions like electrostatic stabilization and proton transfer networks.

Step 2: Reaction Coordinate Identification Based on the established mechanism for esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis (which often involves a nucleophilic attack and general acid/base catalysis), identify the key internal coordinates that define the reaction path. These typically include the forming and breaking bonds. For the acylation step of a serine esterase, this would involve:

- The distance between the catalytic serine oxygen and the substrate's carbonyl carbon.

- The distance between the carbonyl carbon and the scissile bond's oxygen.

- The distance between a proton-donating residue (e.g., histidine) and the leaving group oxygen.

Step 3: Geometry Optimizations Using the defined cluster model, perform geometry optimizations to locate the stable Reactant State (RS), Products, and most critically, the Transition State (TS). The TS structure should be verified by a frequency calculation, which must yield exactly one imaginary frequency corresponding to the motion along the intended reaction coordinate.

Energy Calculation and Analysis

Step 4: Energy Gap Calculation For each stationary point (RS, TS), perform a single-point energy calculation at a higher level of theory to obtain accurate electronic energies. The primary quantitative output is the energy gap between the TS and the RS. This energy barrier can be used to derive relative metabolic stability ranks for a series of analogous compounds [9]. A lower energy gap implies a more stable TS and a faster reaction rate, correlating with lower metabolic stability.

Step 5 (Advanced): Free Energy Profile For a more rigorous and accurate prediction, one can compute the Potential of Mean Force (PMF) along the reaction coordinate using QM/MM methods. This involves running molecular dynamics simulations at constrained values of the reaction coordinate to obtain the free energy profile, which includes entropic effects and is directly related to the experimental reaction rate [31].

Data Integration and Validation

- Step 6: Correlation with Experimental Data Validate the computational model by correlating the calculated energy barriers (or relative stabilities) with experimentally determined metabolic half-lives for a set of known compounds [9]. A strong correlation justifies the use of the model for predicting the stability of novel ester-containing molecules.

Table 1: Key Calculated and Experimental Parameters for Model Validation

| Compound | Calculated Energy Barrier (a.u.) | Predicted Stability Rank | Experimental Half-life (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound A | 0.125 | High | 120 |

| Compound B | 0.098 | Medium | 60 |

| Compound C | 0.075 | Low | 15 |

| Compound D | 0.132 | High | 150 |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for building and applying a QM model for ester hydrolysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QM Modeling

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Ester Hydrolysis Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS) | Software suite to perform QM calculations, including geometry optimizations, frequency, and single-point energy calculations. | Essential for executing the core protocol: optimizing RS/TS structures and calculating the crucial energy gaps that predict metabolic stability [9]. |

| QM/MM Software (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS with QM/MM plugins) | Enables hybrid simulations where the reacting core is treated with QM and the enzyme environment with molecular mechanics. | Provides a more realistic and accurate model of the enzyme-inhibitor complex, capturing environmental effects on the reaction energetics [31]. |

| Active Site Cluster Model | A curated set of atoms representing the enzyme's catalytic site, including the substrate, catalytic residues, and key water molecules. | Serves as the fundamental computational model on which QM calculations are performed. Its accurate definition is critical for predictive success [9]. |

| Reaction Coordinate | A set of internal coordinates (e.g., bond lengths, angles) that uniquely define the progression of the chemical reaction. | Guides the search for the transition state and is the variable along which the free energy profile is computed for the hydrolysis reaction [31]. |

| Experimental Half-life Dataset | A collection of compounds with known in vitro metabolic half-lives in human plasma or liver microsomes. | Used for critical validation of the QM model. The correlation between calculated energy gaps and experimental half-lives establishes model credibility [9] [7]. |

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

- Handling Large Systems: For very large or flexible substrates, a full QM treatment of the entire molecule may be prohibitive. Consider focusing the high-level QM calculation on the reacting ester group and its immediate surroundings, treating the rest of the molecule with a lower-level method or molecular mechanics.

- TS Convergence: Locating a valid transition state can be challenging. Using a good initial guess derived from a similar system or performing a relaxed potential energy surface scan along the reaction coordinate can provide a starting point for TS optimization.

- Solvation and Environmental Effects: The cluster model approximates the enzyme environment. For critical applications, a QM/MM calculation is recommended to explicitly include the electrostatic and steric effects of the full protein and solvent, which can significantly alter reaction barriers [31].

- Interpretation of Results: The primary output is a relative ranking of metabolic stability based on energy gaps. This model excels at discriminating between compounds (e.g., identifying which of two esters is hydrolyzed faster) rather than predicting absolute half-life values, a task where data-driven machine learning models may have an advantage [9].

The construction of QM models for esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis provides a powerful, mechanism-driven approach to predict metabolic stability. By calculating the energy gaps along the hydrolysis pathway, this protocol enables researchers to rank compounds and gain atom-level insight into the determinants of their metabolic fate. When integrated with experimental validation, this QM-based protocol serves as a valuable in silico tool for guiding the rational design of ester-based pro-drugs and soft-drugs with optimized pharmacokinetic profiles.

Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) for Enzyme Simulations

Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) methodologies have emerged as indispensable tools for computational modeling of enzyme structure and reaction mechanisms, particularly within the context of metabolic stability prediction research. These hybrid approaches balance computational accuracy with feasibility by treating the enzymatically active region where chemical transformations occur with quantum mechanical precision, while modeling the surrounding protein environment with molecular mechanical force fields. The foundational work by Warshel and Levitt in 1976 first established the theoretical basis for these methods, enabling researchers to study enzymatic reactions with unprecedented detail [32]. For researchers investigating metabolic stability, QM/MM provides the unique capability to accurately predict thermodynamic parameters and reaction pathways of metabolic transformations, essential for understanding drug metabolism and toxicity profiles.

The fundamental challenge in employing QM/MM for enzyme simulations lies in the appropriate partitioning of the system into QM and MM regions and the numerous practical choices required throughout the modeling procedure [32]. This protocol article addresses these challenges by providing detailed methodologies for preparing protein structures, selecting QM regions, choosing electronic structure methods, and implementing advanced sampling techniques specifically tailored for enzyme simulations in metabolic research.

Theoretical Background and Significance

QM/MM Methodology Fundamentals

In QM/MM approaches, the system is partitioned into two distinct regions: a QM region encompassing the active site where bond breaking/forming occurs, and an MM region comprising the remaining protein structure and solvent environment. The total energy of the system is calculated as:

[ E{total} = E{QM} + E{MM} + E{QM/MM} ]

where ( E{QM} ) represents the quantum mechanical energy of the active region, ( E{MM} ) is the molecular mechanical energy of the environment, and ( E_{QM/MM} ) describes the interactions between these regions [32] [33]. The electrostatic embedding scheme, which explicitly includes the electrostatic interactions between QM electrons and MM point charges in the QM Hamiltonian, has proven particularly effective for enzyme simulations:

[ H^{QM/MM} = H^{QM}e - \sumi^n \sumJ^M \frac{e^2 QJ}{4 \pi \epsilon0 r{iJ}} + \sumA^N \sumJ^M \frac{e^2 ZA QJ}{4 \pi \epsilon0 R{AJ}} ]

where the first term represents the electronic Hamiltonian of the isolated QM system, the second term describes electron-MM charge interactions, and the third term accounts for nucleus-MM charge interactions [33].

Relevance to Metabolic Stability Prediction

Accurate determination of thermodynamic parameters is crucial for predicting metabolic stability, as thermodynamics plays a fundamental role in regulating metabolic processes [5]. QM/MM methods enable first-principles prediction of reaction-free energies (( \Delta G_r )) for enzymatic transformations with mean absolute errors of 1.60-2.27 kcal/mol, approaching the desired benchmark chemical accuracy of 1 kcal/mol [5]. This unprecedented accuracy across diverse metabolic reactions provides researchers with reliable computational tools for predicting metabolic pathways and stability without sole reliance on experimental data, filling critical knowledge gaps for secondary metabolites and cofactors where empirical group-contribution methods often fail [5].

Computational Protocols

System Preparation and QM Region Selection

Table 1: QM Region Selection Guidelines for Enzyme Simulations

| Consideration | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Size of QM Region | Typically 50-150 atoms | Balances computational cost with chemical accuracy [34] |

| Content | Substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors, key water molecules | Ensumes complete representation of reacting species [32] |

| Covalent Boundaries | Use hydrogen link atoms or similar capping schemes | Maintains valence completeness when cutting bonds between QM/MM regions [33] |

| Charge & Multiplicity | Specify total charge and spin state appropriate for reaction mechanism | Ensures proper electronic state description [33] |

The initial step involves preparing the protein structure through standard molecular dynamics protocols, including protonation state assignment at physiological pH, solvation in explicit water, and ion addition for electrostatic neutrality. The QM region should encompass the substrate, catalytic residues directly involved in the reaction, essential cofactors (e.g., flavins, NADH), and structurally important water molecules [32]. For metabolic stability studies, particular attention should be paid to the chemical transformation being investigated, ensuring the QM region includes all atoms involved in bond cleavage/formation and electronic reorganization.

Electronic Structure Method Selection

Table 2: Performance of DFT Functionals for Biochemical Reaction Free Energies

| Functional | Type | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP-D3 | Hybrid GGA | 1.60-2.27 | General metabolic reactions [5] |

| PBE0 | Hybrid GGA | 1.60-2.27 | Redox reactions [5] |

| SCAN | meta-GGA | 1.60-2.27 | Diverse properties [5] |

| LC-ωPBE | Range-separated | 1.60-2.27 | Charge-transfer reactions [5] |

| B2PLYP | Double-hybrid | 1.60-2.27 | High-accuracy benchmarks [5] |

Density functional theory (DFT) remains the most widely used QM method for enzyme simulations due to its favorable balance between accuracy and computational cost. As demonstrated in extensive benchmarking studies, various exchange-correlation functionals when combined with calibration can achieve chemical accuracy for biochemical reaction free energies [5]. The 6-31G* basis set provides a good starting point for geometry optimization, while larger basis sets (e.g., 6-311++G) can be employed for single-point energy calculations to improve accuracy [5]. Solvation effects must be incorporated through implicit solvation models such as SMD (Solvation Model based on Density), with particular attention to pH effects when computing reaction free energies at physiological pH [5].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Advanced sampling methods are essential for obtaining statistically meaningful free energy landscapes of enzymatic reactions. The recent integration of QM/MM with enhanced sampling algorithms in packages like GENESIS has enabled the calculation of potential of mean force (PMF) for enzyme-catalyzed reactions [35]. Key methodologies include:

- Replica-Exchange Umbrella Sampling (REUS): Multiple simulations with biasing potentials are run in parallel at different temperatures or Hamiltonian parameters, enabling efficient sampling of high-energy states [35].

- Generalized Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (gREST): Enhances conformational sampling by elevating temperature specifically in the solute region while maintaining the solvent at normal temperature [35].

- Path Sampling with String Method: Determines minimum free energy paths for complex reaction coordinates in high-dimensional space [35].

These advanced sampling techniques, combined with high-performance QM/MM implementations, now enable simulations on the nanosecond timescale for QM regions of approximately 100 atoms embedded in MM systems of ~100,000 atoms [35].

Diagram 1: QM/MM Simulation Workflow for Enzyme Studies. This flowchart illustrates the sequential steps for implementing QM/MM simulations of enzymatic systems, from initial preparation through free energy analysis.

Implementation and Troubleshooting

Software Integration and Performance Optimization

Modern QM/MM implementations leverage interfaces between molecular dynamics packages and quantum chemistry codes. Popular combinations include:

- GENESIS with QSimulate-QM: Provides highly parallelized algorithms enabling MD simulations at the DFTB level with QM regions of ~100 atoms and MM regions of ~100,000 atoms with performance exceeding 1 ns/day using one computer node [35].

- GROMACS with CP2K: Implements the GEEP (Gaussian-Expanded Electrostatic Potential) approach for electrostatic embedding with periodic boundary conditions [33].

- Amber/GROMACS with external QM codes: Supports interfaces to various quantum packages for specialized applications [34].

Performance optimization requires careful attention to the treatment of periodic boundary conditions, which can be addressed through real-space QM calculations with duplicated MM charges and Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) treatment of long-range electrostatics [35]. The computational expense remains dominated by the QM portion, making method selection and system size critical considerations [34].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- System Size Limitations: For large QM regions (>150 atoms), consider semi-empirical methods (DFTB) or multiple-time step integrators to improve performance [35] [33].

- Boundary Artifacts: Implement improved coupling schemes using "filler" material to eliminate vacuum surfaces in the QM calculation, particularly for systems with structural defects or complex interfaces [36].

- Convergence Problems: Employ adaptive sampling techniques or extended simulation timescales enabled by GPU-accelerated QM programs such as TeraChem and QUICK [35].

- Electronic Structure Failures: Perform stability analysis on calculated frequencies to confirm ground state identification, particularly for metallic systems or complexes with open-shell character [5].

Application to Metabolic Stability Prediction