QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling: Advanced Techniques for Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and pharmacophore modeling, two indispensable pillars of computer-aided drug design.

QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling: Advanced Techniques for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and pharmacophore modeling, two indispensable pillars of computer-aided drug design. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts defining these fields, details the methodologies for building robust models (including structure-based and ligand-based approaches), and addresses critical challenges in data quality and model overfitting. Further, it delves into rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of different techniques. By synthesizing the latest advancements and practical applications—from virtual screening to ADME-tox prediction—this resource aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to effectively leverage these computational tools for accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents.

The Essential Guide to QSAR and Pharmacophore Concepts in Drug Design

The pharmacophore concept stands as a fundamental pillar in modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), providing an abstract representation of the molecular interactions essential for biological activity. This concept has evolved significantly from its early formulations to its current rigorous definition by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). In contemporary drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling serves as a powerful tool for bridging the gap between structural information and biological response, enabling researchers to identify novel bioactive compounds through virtual screening and rational drug design approaches. The pharmacophore's utility extends across the entire drug discovery pipeline, from initial lead identification to ADME-tox prediction and optimization of drug candidates [1].

The evolution of the pharmacophore mirrors advances in both medicinal chemistry and computational methods. Initially a qualitative concept describing common functional groups among active compounds, it has matured into a quantitative, three-dimensional model that captures the essential steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition. This transformation has positioned pharmacophore modeling as an indispensable component in the toolkit of drug development professionals, particularly valuable for its ability to facilitate "scaffold hopping" – identifying structurally diverse compounds that share key pharmacological properties through common interaction patterns with biological targets [2].

Historical Foundations: From Ehrlich to IUPAC

The conceptual foundation of the pharmacophore dates back to the late 19th century when Paul Ehrlich proposed that specific chemical groups within molecules are responsible for their biological effects [3]. Although historical analysis reveals that Ehrlich himself never used the term "pharmacophore," his work established the fundamental idea that molecular components could be correlated with biological activity [4]. The term "pharmacophore" was eventually coined by Schueler in his 1960 book Chemobiodynamics and Drug Design, where he defined it as "a molecular framework that carries (phoros) the essential features responsible for a drug's (pharmacon) biological activity" [1]. This definition marked a critical shift from thinking about specific "chemical groups" to more abstract "patterns of features" responsible for biological activity.

The modern conceptualization was popularized by Lemont Kier, who mentioned the concept in 1967 and used the term explicitly in a 1971 publication [4]. Throughout the late 20th century, as computational methods gained prominence in drug discovery, the need for a standardized definition became apparent. This culminated in the 1998 IUPAC formalization, which defined a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4] [5]. This definition established the pharmacophore as an abstract description of molecular interactions rather than a specific chemical structure, emphasizing the essential features required for biological recognition and activity [2].

The IUPAC Definition and Core Components

The IUPAC definition represents the current gold standard for understanding pharmacophores in both academic and industrial drug discovery settings. According to this definition, a pharmacophore does not represent a real molecule or specific chemical groups, but rather the largest common denominator of molecular interaction features shared by active molecules [1]. This abstract nature allows pharmacophores to transcend specific chemical scaffolds and facilitate the identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activities.

Essential Pharmacophore Features

Pharmacophore models are composed of distinct chemical features that represent key interaction points between a ligand and its biological target. These features include:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA): Atoms or groups that can accept hydrogen bonds, typically represented as vectors or spheres [2]

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD): Atoms or groups that can donate hydrogen bonds, represented as vectors or spheres [2]

- Hydrophobic regions (H): Non-polar areas that participate in hydrophobic interactions, represented as spheres [4] [2]

- Aromatic rings (AR): Planar ring systems that enable π-π stacking or cation-π interactions, represented as planes or spheres [2]

- Positive ionizable groups (PI): Features that can carry positive charges, facilitating ionic interactions [2]

- Negative ionizable groups (NI): Features that can carry negative charges, enabling ionic interactions [2]

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Properties

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Interaction Type | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Amines, Carboxylates, Ketones, Alcoholes |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Amines, Amides, Alcoholes |

| Hydrophobic | Sphere | Hydrophobic Contact | Alkyl Groups, Alicycles, non-polar aromatic rings |

| Aromatic | Plane or Sphere | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Any aromatic ring |

| Positive Ionizable | Sphere | Ionic, Cation-π | Ammonium Ions |

| Negative Ionizable | Sphere | Ionic | Carboxylates, Phosphates |

Exclusion Volumes and Shape Constraints

Beyond the chemical features, pharmacophore models often incorporate exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints imposed by the binding site geometry [2]. These volumes define regions in space where ligand atoms cannot be positioned without encountering steric clashes with the target protein. Exclusion volumes are particularly important for structure-based pharmacophore models derived from protein-ligand complexes, as they accurately capture the spatial restrictions of the binding pocket [3]. The inclusion of shape constraints significantly enhances the selectivity of pharmacophore models by eliminating compounds that satisfy the chemical feature requirements but would be sterically incompatible with the target.

Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches: Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Methods

The generation of pharmacophore models follows two principal methodologies, each with distinct requirements and applications. The choice between these approaches depends primarily on the available structural and biological data.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives features directly from the three-dimensional structure of a target protein in complex with a ligand. This approach requires experimentally determined structures from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or in some cases, computationally generated homology models [3] [2]. The process involves analyzing the interaction pattern between the ligand and the binding site to identify key molecular features responsible for binding affinity and specificity.

Software tools such as LigandScout [3] [6] and Discovery Studio [3] automate the extraction of pharmacophore features from protein-ligand complexes. These programs identify potential hydrogen bonding interactions, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions, and other binding features, converting them into corresponding pharmacophore elements. When only the apo structure (unbound form) of the target is available, some programs can generate pharmacophore models based solely on the binding site topology, though these models typically require more extensive validation and refinement [3].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When three-dimensional structural information of the target is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling offers a powerful alternative. This approach derives common pharmacophore features from a set of known active ligands that bind to the same biological target at the same site [5] [2]. The fundamental assumption is that these compounds share a common binding mode and therefore common interaction features with the target.

The ligand-based pharmacophore development process typically involves:

- Training set selection: Curating a structurally diverse set of molecules with confirmed biological activity and, ideally, including inactive compounds to define activity boundaries [4] [3]

- Conformational analysis: Generating a set of low-energy conformations for each compound that likely contains the bioactive conformation [4]

- Molecular alignment: Superimposing the compounds to identify common spatial arrangements of chemical features [4]

- Feature abstraction: Transforming the aligned functional groups into abstract pharmacophore elements [4]

- Model validation: Testing the model's ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds [4]

Table 2: Comparison of Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Required Data | 3D Structure of protein-ligand complex | Set of known active ligands |

| Key Advantage | Direct incorporation of binding site constraints | No need for target structure |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality and relevance of the structure | Assumes common binding mode for all ligands |

| Exclusion Volumes | Directly derived from binding site | Estimated from molecular shapes of aligned ligands |

| Common Software | LigandScout, Discovery Studio | PHASE, Catalyst, PharmaGist |

| Best Application | Targets with well-characterized binding sites | Targets with multiple known ligands but no structure |

Experimental Protocols in Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation using LigandScout

Purpose: To create a structure-based pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex for virtual screening applications.

Materials and Methods:

- Software Requirement: LigandScout v4.4 or higher [7]

- Input Data: Protein-ligand complex structure in PDB format [3]

- Processing Steps:

- Load the protein-ligand complex structure into LigandScout

- Automatically detect interaction patterns between the ligand and binding site residues

- Convert identified interactions into pharmacophore features:

- Hydrogen bonds → HBA/HBD features with directionality vectors

- Hydrophobic contacts → Hydrophobic features

- Aromatic interactions → Aromatic ring features

- Ionic interactions → Positive/Negative ionizable features

- Generate exclusion volumes based on the protein's binding site geometry

- Optimize feature tolerances and weights based on interaction strength and conservation

- Validate the model using known active and inactive compounds [3]

Validation Metrics:

- Enrichment factor (EF) - measure of active compound enrichment in virtual screening [3]

- Yield of actives - percentage of active compounds in virtual hit list [3]

- Sensitivity and specificity - ability to identify actives and exclude inactives [7]

- ROC-AUC - overall model performance [3]

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Development for Flavonoid Analysis

Purpose: To develop a ligand-based pharmacophore model for identifying anti-HBV flavonols using a set of known active compounds.

Materials and Methods:

- Training Set: Nine flavonols with experimentally confirmed anti-HBV activity (Kaempferol, Isorhamnetin, Icaritin, etc.) [7]

- Software: LigandScout v4.4 for model generation [7]

- Conformational Analysis:

- Generate up to 200 low-energy conformers per molecule

- Set energy window of 20.0 kcal/mol

- Maximum pool size of 4000 conformers [7]

- Model Generation:

- Align molecules based on common chemical features

- Use pharmacophore fit and atom overlap scoring function

- Apply merged feature pharmacophore type to ensure features match all input molecules [7]

- Virtual Screening:

- Screen using PharmIt server against natural product databases

- Apply high-throughput screening protocols [7]

Validation Approach:

- Test model with external compound sets including flavones, flavanones, and other polyphenols [7]

- Evaluate sensitivity and specificity using FDA-approved chemicals [7]

- Apply QSAR analysis with predictors (x4a and qed) to validate bioactivity predictions [7]

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Virtual Screening and Lead Identification

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents one of the most successful applications of the pharmacophore concept in drug discovery. By screening large compound databases against a well-validated pharmacophore model, researchers can significantly enrich hit rates compared to random screening approaches. Reported hit rates from prospective pharmacophore-based virtual screening typically range from 5% to 40%, substantially higher than the <1% hit rates often observed in traditional high-throughput screening [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying novel scaffold hops – compounds with structurally distinct backbones that maintain the essential features required for binding – thereby expanding intellectual property opportunities and providing starting points for medicinal chemistry optimization.

The virtual screening process typically involves:

- Preparing a database of compounds with generated low-energy conformations

- Screening each compound against the pharmacophore query

- Identifying molecules that match the essential features within spatial tolerances

- Ranking hits based on fit quality and additional criteria such as drug-likeness

- Experimental validation of top-ranking hits [5]

Integration with Other CADD Methods

Pharmacophore modeling rarely operates in isolation within modern drug discovery workflows. Instead, it frequently integrates with other computational approaches to enhance success rates:

- Pharmacophore-Docking Hybrid Approaches: Combining pharmacophore screening with molecular docking can improve virtual screening efficiency by using pharmacophores as a pre-filter to reduce the number of compounds subjected to more computationally intensive docking simulations [1].

- QSAR Integration: Pharmacophore features can serve as descriptors in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, helping to correlate spatial arrangement of chemical features with biological activity levels [7] [1].

- ADME-tox Prediction: Pharmacophore models have been successfully applied to predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME-tox) properties, enabling early elimination of compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic profiles [1].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software Suite | Structure & ligand-based modeling | Advanced pharmacophore feature detection, virtual screening [7] [3] |

| PharmIt | Online Platform | Virtual screening | High-throughput screening, public compound databases [7] [6] |

| PHASE | Software Module | Ligand-based modeling | Comprehensive pharmacophore perception, QSAR integration [6] |

| DruGUI | Computational Tool | Druggability assessment | MD simulation analysis, binding site characterization [6] |

| Pharmmaker | Online Tool | Target-based discovery | Automated PM construction from druggability simulations [6] |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Pharmacophore fingerprinting | Molecular descriptor calculation, similarity screening [5] |

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

Pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve with advancements in computational power and algorithmic sophistication. Several emerging trends are shaping the future of this field:

- Dynamic Pharmacophores: Incorporation of protein flexibility and binding site dynamics through molecular dynamics simulations, providing more realistic representations of molecular recognition events [6].

- Machine Learning Integration: Combining traditional pharmacophore approaches with machine learning algorithms to enhance model accuracy and predictive power [1].

- Application to Challenging Targets: Expansion of pharmacophore methods to difficult target classes such as protein-protein interactions, ion channels, and allosteric modulators [6] [1].

- Natural Product Exploration: Increased application of pharmacophore models to explore the diverse chemical space of natural products, facilitating the identification of novel bioactive scaffolds [2].

The integration of pharmacophore modeling with structural biology, cheminformatics, and experimental screening continues to solidify its position as a cornerstone technique in rational drug design. As these methods become more sophisticated and accessible, their impact on accelerating drug discovery and optimizing therapeutic agents is expected to grow substantially.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) is a computational methodology that establishes mathematical relationships between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activity [8]. These models are built on the fundamental principle that the biological activity of a compound is a function of its physicochemical properties and structural features [9]. The general QSAR equation is expressed as:

Biological Activity = f(physicochemical properties, structural properties) + error [8]

QSAR finds extensive application in drug discovery and development, enabling researchers to predict the biological activity, toxicity, and physicochemical properties of novel compounds before synthesis, thereby reducing reliance on expensive and time-consuming experimental procedures [9]. The core assumption is that similar molecules exhibit similar activities, though this leads to the "SAR paradox" where minor structural changes can sometimes result in significant activity differences [8].

Molecular Descriptors and Their Significance

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of a molecule's structural and physicochemical features that serve as the independent variables in QSAR models. The table below summarizes the major categories of molecular descriptors and their roles in biological interactions.

Table 1: Fundamental Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Studies

| Molecular Property | Corresponding Interaction Type | Common Parameters/Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity | Hydrophobic interactions | log P, π (pi), f (hydrophobic fragmental constant), RM [10] |

| Polarizability | van der Waals interactions | Molar Refractivity (MR), parachor, Molar Volume (MV) [10] |

| Electron Density | Ionic bonds, dipole-dipole interactions, hydrogen bonds | σ (Hammett constant), R, F, κ, quantum chemical indices [10] |

| Topology | Steric hindrance, geometric fit | Es (Taft's steric constant), rv, L, B, distances, volumes [10] |

Key Descriptor Categories

- Lipophilicity and the Partition Coefficient (log P): Lipophilicity, often quantified by log P (the partition coefficient in an n-octanol/water system), measures a compound's tendency to dissolve in non-polar versus polar solvents [10]. It is a critical parameter in the Hansch model, one of the most established QSAR approaches, which relates biological activity to a combination of log P, electronic, and steric parameters [10] [8]. The hydrophobic fragmental constant (f) allows for the calculation of log P based on additive molecular fragments [10].

- Electronic Parameters: The Hammett constant (σ) quantifies the electron-withdrawing or donating effect of a substituent, influencing ionization and reactivity [10].

- Steric Parameters: Parameters like Taft's steric constant (Es) and Molar Refractivity (MR) describe the spatial occupancy and bulkiness of atoms or groups, which affects a molecule's ability to fit into a binding site [10].

- Quantum Mechanical Descriptors: These include atom partial charges, dipole moments, and frontier orbital energies (HOMO/LUMO), providing detailed insight into a molecule's electronic structure and reactivity [10].

Experimental Protocols in QSAR Modeling

The development of a robust and predictive QSAR model follows a systematic workflow involving distinct stages.

General QSAR Workflow

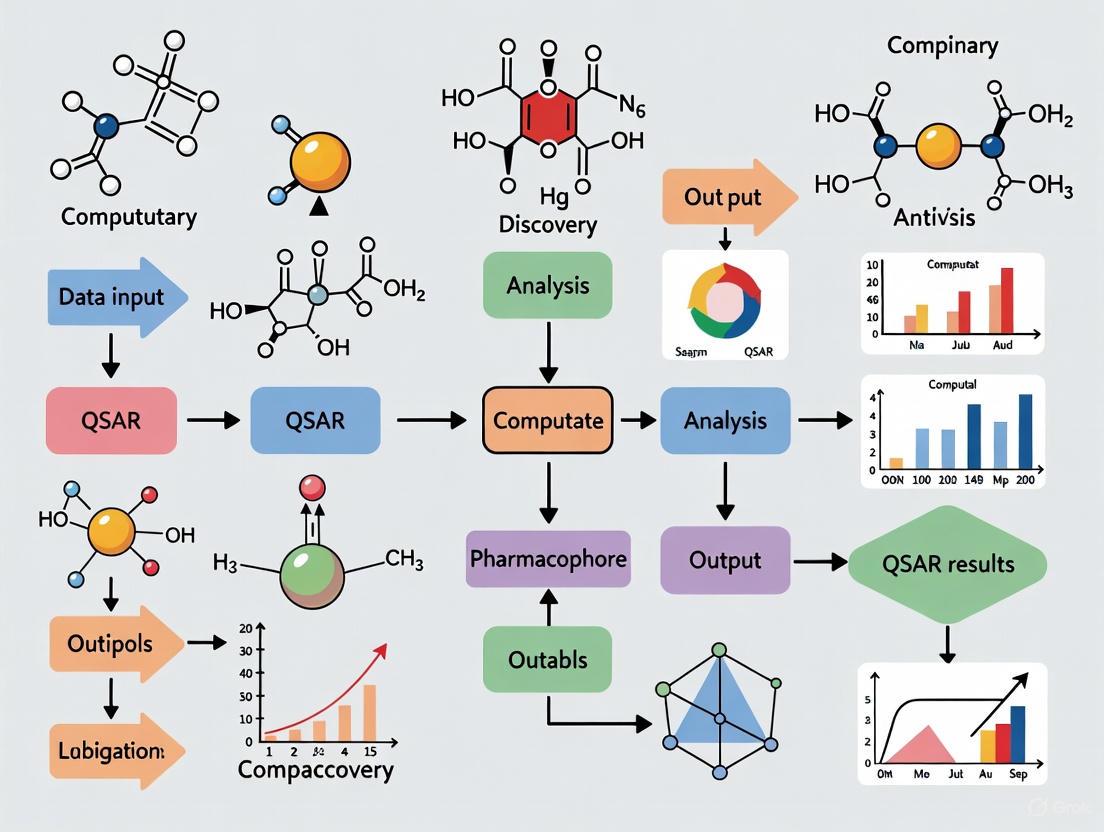

The following diagram outlines the standard protocol for developing a QSAR model.

Protocol 1: Developing a 2D-QSAR Model Using the Hansch Approach

This protocol is ideal for a congeneric series of compounds where the core scaffold remains constant and substituents vary.

1. Data Set Curation

- Select a series of compounds (typically 20-50) with a common molecular scaffold and known biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) [11] [9].

- Ensure all compounds act via the same mechanism of action [10].

- Convert biological activity values to a logarithmic scale (e.g., log(1/C), where C is the molar concentration producing the effect) to linearize the relationship.

- Divide the data set into a training set (~70-80%) for model building and a test set (~20-30%) for external validation [8].

2. Descriptor Calculation

- For each compound, calculate relevant physicochemical parameters.

- Lipophilicity: Calculate the substituent constant π for each substituent, where πₓ = log P₍R−X₎ - log P₍R−H₎, or use the overall log P of the molecule [10].

- Electronic Effects: Calculate the Hammett constant (σ) for each substituent [10].

- Steric Effects: Calculate molar refractivity (MR) or Taft's steric constant (Es) for substituents [10].

3. Model Construction using Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

- Use statistical software to perform MLR, correlating the biological activity (log(1/C)) with the calculated descriptors.

- A general linear Hansch equation takes the form: log(1/C) = a(log P) + b(σ) + c(MR) + k [10] where a, b, c are coefficients, and k is a constant.

4. Model Validation

- Internal Validation: Perform cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out) to check robustness. The cross-validated R² (q²) should be > 0.5 [8] [11].

- External Validation: Use the test set to assess predictive power. The predicted R² for the test set should be high [8].

- Y-Scrambling: Randomize the response variable to ensure the model is not a result of chance correlation [8].

Protocol 2: 3D-QSAR using Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

3D-QSAR techniques like CoMFA consider the three-dimensional properties of molecules and are applicable to non-congeneric series.

1. Preparation and Alignment

- Obtain or generate the 3D structures of all molecules.

- Identify the bioactive conformation and a common pharmacophore for molecular superposition.

- Align all molecules according to the pharmacophore hypothesis [10].

2. Field Calculation

- Place the aligned molecules in a 3D grid with a typical spacing of 2.0 Å.

- Use a probe atom (e.g., sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at each grid point [10] [8].

3. Data Analysis with Partial Least Squares (PLS)

- The calculated interaction energies form a large data table, which is analyzed using PLS regression to correlate the field values with biological activity [10].

- The output is a 3D contour map visualizing regions where specific steric or electrostatic features enhance or diminish biological activity.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Item/Tool | Function in QSAR Protocol |

|---|---|

| Congeneric Compound Series | A set of molecules with a common scaffold and varying substituents; the foundational requirement for classical 2D-QSAR [10]. |

| n-Octanol/Water System | Standard solvent system for experimentally determining the partition coefficient (log P), a key descriptor of lipophilicity [10]. |

| Molecular Modeling Software | Software capable of energy minimization, conformational analysis, and 3D structure generation for 3D-QSAR studies. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Tools (e.g., GUSAR software) for computing 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [11]. |

| Statistical Analysis Package | Software with MLR, PLS, and PCA capabilities for constructing and validating the mathematical QSAR model [10] [9]. |

Applications of QSAR in Drug Discovery and Toxicology

QSAR models have become indispensable tools across various scientific disciplines.

- Lead Optimization: QSAR guides medicinal chemists by identifying which structural features and physicochemical properties contribute positively to biological activity, enabling the rational design of more potent analogs [9].

- Toxicity and Environmental Risk Assessment: Quantitative Structure-Toxicity Relationship (QSTR) models predict the toxicological profiles of chemicals, including their carcinogenicity and ecotoxicity, which is vital for regulatory decisions and environmental health [8] [12] [9].

- Prediction of Antitarget Interactions: QSAR models can predict unintended interactions of drug candidates with "antitargets" (e.g., hERG channel, specific metabolizing enzymes), helping to avoid adverse drug reactions (ADRs) early in development [11].

- Property Prediction: Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships (QSPR) are used to predict physicochemical properties such as boiling points, solubility, and absorption, which are critical for drug-likeness [8].

Integration with Modern Computational Approaches

The field of QSAR is evolving through integration with advanced computational techniques.

Pharmacophore Modeling is closely related to QSAR. While QSAR correlates descriptors with activity, a pharmacophore represents the essential spatial arrangement of molecular features necessary for biological activity [13]. Modern methods like PharmacoForge use diffusion models to generate 3D pharmacophores conditioned on a protein pocket, which can then be used for ultra-fast virtual screening of commercially available compounds [14].

Machine Learning and AI are now widely employed in QSAR. Instead of traditional regression, methods like Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, and Neural Networks are used to handle large descriptor sets and uncover complex, non-linear relationships [8].

The integration of QSAR with read-across techniques has led to the development of hybrid methods like q-RASAR, which can offer improved predictive performance [8].

The Synergy of QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling in CADD

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has become an indispensable component of modern pharmaceutical research, significantly reducing the time and costs associated with drug discovery [15]. Within the CADD toolkit, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and pharmacophore modeling represent two powerful techniques that, when used synergistically, enhance the efficiency of hit identification and lead optimization processes [16]. QSAR models mathematically correlate structural descriptors of compounds with their biological activity, while pharmacophore models abstractly represent the steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition [1] [17]. This application note explores the integrated application of these methodologies, providing detailed protocols and case studies within the context of advanced drug discovery research.

Theoretical Foundation and Synergistic Benefits

Fundamental Concepts

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. It is not a specific molecular structure, but rather an abstract pattern of features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors (HBD/HBA), hydrophobic areas (H), positively/negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR) [16].

QSAR establishes a mathematical relationship between chemical structure descriptors and biological activity using various machine learning techniques [18] [15]. The core principle is that biological activity can be quantitatively predicted from molecular structure, reducing the need for extensive experimental screening.

Synergistic Advantages

The integration of pharmacophore and QSAR methodologies creates a powerful workflow that leverages the strengths of both approaches:

- Enhanced Interpretability: Pharmacophore models provide visual and intuitive understanding of key molecular interactions, while QSAR adds quantitative predictive power [19] [17].

- Scaffold Hopping Capability: The abstract nature of pharmacophore features enables identification of structurally diverse compounds sharing essential interaction capabilities, which QSAR can then quantitatively prioritize [17].

- Improved Model Robustness: Combining these approaches helps overcome limitations of individual methods, particularly regarding activity prediction for novel chemotypes [17].

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic workflow between these approaches:

Integrated Methodologies and Protocols

Structure-Based Protocol

When the target protein structure is available, a structure-based approach can be employed:

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation and QSAR Modeling

Protein Preparation

- Retrieve 3D structure from PDB (www.rcsb.org) [16]

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign proper protonation states, and remove structural artifacts

- Energy minimization using appropriate force fields (CHARMM, AMBER)

Binding Site Analysis

- Identify binding pocket using tools like GRID or LUDI [16]

- Analyze key interacting residues and map potential interaction points

Pharmacophore Generation

Conformation Generation and Alignment

- Generate low-energy conformers for training set compounds

- Align compounds to pharmacophore model

3D-QSAR Model Development

- Calculate molecular interaction fields (steric, electrostatic)

- Apply Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build CoMFA/CoMSIA models [19]

- Validate using cross-validation and external test sets

Ligand-Based Protocol

When structural information of the target is unavailable, ligand-based approaches are employed:

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore and QSAR Modeling

Data Set Curation

- Collect compounds with known biological activities spanning a wide potency range

- Categorize into highly active, active, moderately active, and inactive [20]

- Divide into training and test sets maintaining activity distribution

Pharmacophore Model Generation

Pharmacophore-Based Alignment

- Use best pharmacophore model as template for molecular alignment

- Ensure consistent orientation of key functional groups

QSAR Model Construction

- Calculate 3D molecular descriptors and fields

- Develop predictive model using PLS or other machine learning algorithms

- Validate model using test set compounds and applicability domain assessment [18]

Case Studies and Applications

Aurora Kinase B Inhibitors

A recent study demonstrated the successful application of integrated QSAR-pharmacophore modeling for Aurora Kinase B (AKB) inhibitors, a promising cancer therapeutic target [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Set: 561 structurally diverse AKB inhibitors

- QSAR Model: 7-variable GA-MLR model following OECD guidelines

- Key Descriptors: fringNplaN4B, fsp3Csp2N5B, NH2B, fsp2Osp2C5B, dalipo5B, fOringC6B, fringNC6B

- Validation: R²tr = 0.815, Q²LMO = 0.808, R²ex = 0.814, CCCex = 0.899

Key Findings:

- Model identified critical pharmacophoric features including lipophilic and polar groups at specific distances

- Ring nitrogen and carbon atoms play crucial roles in determining inhibitory activity

- The balanced model demonstrated high predictive ability and mechanistic interpretability [18]

UPPS Inhibitors for Antibacterial Development

Another study targeted Undecaprenyl Pyrophosphate Synthase (UPPS) for treating Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Set: 34 UPPS inhibitors with IC₅₀ values from 0.04 to 58 μM

- Pharmacophore Generation: HypoGen algorithm with one HBA, two hydrophobic, and one aromatic feature

- Validation: Correlation coefficient of 0.86 for training set, Fisher's randomization at 95% confidence level

- Virtual Screening: Applied to ZINC15, Drug-Like Diverse, and Mini Maybridge databases

Key Findings:

- Identified 70 hits with superior docking affinities than reference compound

- Discovered five promising novel UPPS inhibitors through molecular dynamics simulations [20]

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR)

The novel QPHAR method represents a direct integration of pharmacophore and QSAR approaches, operating directly on pharmacophore features rather than molecular structures [17].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Sets: 250+ diverse datasets from ChEMBL

- Method: Aligns input pharmacophores to a consensus (merged) pharmacophore

- Machine Learning: Uses relative position information to build quantitative models

- Validation: Fivefold cross-validation with average RMSE of 0.62

Key Findings:

- Robust models obtained with small datasets (15-20 training samples)

- Abstract pharmacophore representation reduces bias toward overrepresented functional groups

- Enables scaffold hopping by focusing on interaction patterns rather than specific structural motifs [17]

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Integrated QSAR-Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software | Type | Key Features | Application in Integrated Workflows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dockamon [21] | Commercial | Pharmacophore modeling, 3D/4D-QSAR, molecular docking | Integrated structure-based and ligand-based design in unified platform |

| PHASE [17] | Commercial | Pharmacophore field-based QSAR, PLS regression | Creates predictive models from pharmacophore fields derived from aligned ligands |

| Discovery Studio [20] | Commercial | HypoGen algorithm, 3D QSAR pharmacophore, molecular docking | Ligand-based pharmacophore generation and validation |

| GALAHAD [19] | Commercial | Pharmacophore generation from ligand sets, Pareto ranking | Creates models with multiple tradeoffs between steric and energy constraints |

| LigandScout [7] | Commercial | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Advanced pharmacophore model creation with high-throughput screening capabilities |

Table 2: Summary of Key Performance Metrics from Case Studies

| Case Study | Target | Dataset Size | Model Type | Key Statistical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurora Kinase B [18] | AKB | 561 compounds | 7-descriptor GA-MLR QSAR | R²tr=0.815, Q²LMO=0.808, R²ex=0.814, CCCex=0.899 |

| UPPS Inhibitors [20] | UPPS | 34 compounds | 4-feature 3D QSAR Pharmacophore | Correlation=0.86, Null cost difference=191.39 |

| B-Raf Inhibitors [19] | B-Raf kinase | 39 compounds | CoMSIA with pharmacophore alignment | q²=0.621, r²pred=0.885 |

| QPHAR Validation [17] | Multiple targets | 250+ datasets | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling | Average RMSE=0.62 (±0.18) |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integrated Workflows

| Reagent/Software | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases (ZINC15, ChEMBL, PubChem) [7] [20] | Source of compounds for virtual screening and model building | Provides structural and activity data for training and test sets |

| Conformation Generation Tools (iConfGen, DS Conformers) [7] [20] | Generate bioactive conformations for pharmacophore modeling | Creates low-energy 3D conformers representing potential binding states |

| Molecular Descriptors (PyDescriptor) [18] | Calculate structural descriptors for QSAR analysis | Quantifies structural features correlated with biological activity |

| Validation Tools (Applicability Domain, Y-scrambling) [18] | Assess model robustness and predictive reliability | Ensures models are not overfitted and have true predictive power |

| Docking Software (AutoDock Vina, CDOCKER) [20] [21] | Structure-based validation of pharmacophore hits | Confirms binding mode and interactions predicted by pharmacophore models |

The synergistic integration of QSAR and pharmacophore modeling represents a powerful paradigm in modern computer-aided drug design. This approach leverages the complementary strengths of both methodologies: the abstract, feature-based pattern recognition of pharmacophore modeling combined with the quantitative predictive power of QSAR analysis. As demonstrated through the case studies and protocols presented herein, this integrated framework enhances the efficiency of virtual screening, enables scaffold hopping to novel chemical series, and provides deeper mechanistic insights into structure-activity relationships. The continued development of methods like QPHAR that directly operate on pharmacophore features further strengthens this synergy, promising enhanced efficiency in future drug discovery campaigns.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, establishing mathematical relationships between the chemical structures of compounds and their biological activities [8]. These models are regression or classification systems that use predictor variables consisting of physico-chemical properties or theoretical molecular descriptors to forecast the potency of a biological response [8]. The fundamental hypothesis underlying all QSAR approaches is that similar molecules exhibit similar activities, a principle known as the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), though this comes with the recognized SAR paradox where not all similar molecules share similar activities [8]. The evolution of QSAR methodologies has progressed from simple 2D descriptor-based approaches to sophisticated 3D-dimensional analyses and fragment-based decomposition strategies, enabling more accurate predictions of biological activity and molecular properties critical for drug development [22] [8].

In contemporary drug discovery, QSAR techniques have become indispensable tools for predicting biological activity, optimizing lead compounds, and reducing experimental costs [23] [24]. The ability to predict activities in silico before synthesis allows researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates from vast chemical spaces, significantly accelerating the drug discovery pipeline [25]. This article explores three advanced QSAR methodologies—3D-QSAR, GQSAR, and Fragment-Based QSAR—detailing their theoretical foundations, practical applications, and implementation protocols to provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for rational drug design.

3D-QSAR: Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Principles

3D-QSAR represents a significant advancement over traditional 2D-QSAR methods by incorporating the three-dimensional structural properties of molecules and their spatial orientations [26] [8]. Unlike descriptor-based approaches that compute properties from scalar quantities, 3D-QSAR methodologies utilize force field calculations requiring three-dimensional structures of small molecules with known activities [8]. The fundamental premise of 3D-QSAR is that biological activity correlates not just with chemical composition but with steric and electrostatic fields distributed around the molecules in three-dimensional space [26] [27]. This approach examines the overall molecule rather than single substituents, capturing conformational aspects critical for molecular recognition and biological activity [26].

The first and most established 3D-QSAR technique is Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), which systematically analyzes steric (shape) and electrostatic fields around a set of aligned molecules and correlates these fields with biological activity using partial least squares (PLS) regression [26] [8]. The CoMFA methodology operates on the principle that the biological activity of a compound is dependent on its intermolecular interactions with the receptor, which are governed by the shape of the molecule and the distribution of electrostatic potentials on its surface [26]. Another popular 3D-QSAR approach is Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (COMSIA), which extends beyond steric and electrostatic fields to include additional similarity descriptors such as hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding properties [23]. Modern implementations often combine multiple models with different similarity descriptors and machine learning techniques, with final predictions generated as a consensus of individual model predictions to enhance robustness and accuracy [27].

Applications and Case Studies in Drug Discovery

3D-QSAR has demonstrated significant utility across various stages of drug discovery, particularly in lead optimization where understanding the three-dimensional structural requirements for activity is crucial. A recent application involved the development of novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as potent and selective monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases [23]. In this study, researchers constructed a 3D-QSAR model using the COMSIA method, which exhibited excellent predictive capability with a q² value of 0.569 and r² value of 0.915 [23]. The model successfully guided the design of new derivatives with predicted IC₅₀ values, with compound 31.j3 emerging as the most promising candidate based on both QSAR predictions and subsequent molecular docking studies [23].

Another significant application of 3D-QSAR appears in safety pharmacology screening, where it has been used to identify off-target interactions against the adenosine receptor A2A [24]. In this case study, researchers developed 3D-QSAR models based on in vitro antagonistic activity data and applied them to screen 1,897 chemically distinct drugs, successfully identifying compounds with potential A2A antagonistic activity even from chemotypes drastically different from the training compounds [24]. This demonstrates the value of 3D-QSAR in safety profiling, where it can prioritize compounds for experimental testing and provide mechanistic insights into distinguishing between agonists and antagonists [24]. The interpretability of 3D-QSAR models also provides visual guidance for medicinal chemists, indicating favorable regions for specific functional groups within the active site, thereby inspiring new design ideas in a generative design cycle [27].

Table 1: Key 3D-QSAR Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique | Descriptors Analyzed | Statistical Method | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) | Steric and electrostatic fields | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Lead optimization, Activity prediction [26] [8] |

| COMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen-bonding | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Scaffold hopping, Multi-parameter optimization [23] |

| Consensus 3D-QSAR | Multiple shape and electrostatic similarity descriptors | Machine learning consensus | Binding affinity prediction, Virtual screening [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing 3D-QSAR with COMSIA

Protocol Title: 3D-QSAR Model Development Using COMSIA Methodology

Objective: To develop a predictive 3D-QSAR model for a series of novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors.

Materials and Software:

- Chemical Modeling Software: Sybyl-X or similar molecular modeling suite

- Structure Drawing: ChemDraw for compound construction and optimization

- Computational Resources: Workstation with sufficient processing power for conformational analysis

Procedure:

Compound Selection and Preparation:

- Select a training set of compounds with known biological activities (IC₅₀ values)

- Construct and optimize 2D structures of all compounds using ChemDraw

- Convert 2D structures to 3D conformers using molecular modeling software

- Perform geometry optimization using appropriate force fields [23]

Molecular Alignment:

- Identify a common scaffold or pharmacophore for structural alignment

- Align all molecules to a reference compound using atom-based or field-based methods

- Verify alignment quality through visual inspection and statistical measures

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building:

- Calculate COMSIA descriptors (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor)

- Set the attenuation factor to 0.3 for the Gaussian distance function

- Use partial least squares (PLS) regression to build the QSAR model

- Apply region focusing to improve model quality if necessary [23]

Model Validation:

- Perform leave-one-out cross-validation to determine q² value

- Calculate non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r²)

- Determine standard error of estimate (SEE) and F-value

- Validate model with an external test set not used in model building [23]

Model Application and Interpretation:

- Use the model to predict activities of new designed compounds

- Interpret coefficient contour maps to identify favorable/unfavorable regions

- Guide structural modifications based on model insights [23]

GQSAR: Group-Based Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships

Fundamental Concepts and Advantages

Group-Based QSAR (GQSAR) represents a novel approach that focuses on the contributions of molecular fragments or substituents at specific sites rather than considering the molecule as a whole [8]. This methodology offers significant advantages in drug discovery, particularly when dealing with structurally diverse compounds or when seeking to understand the specific contributions of substituent modifications to biological activity [8]. Unlike traditional QSAR that utilizes global molecular descriptors, GQSAR allows researchers to study various molecular fragments of interest in relation to the variation in biological response, providing more targeted insights for structural optimization [8].

The GQSAR approach is particularly valuable in fragment-based drug design (FBDD), where it accelerates lead optimization and plays a crucial role in diminishing high attrition rates in drug development [22]. By quantifying the contributions of individual fragments, GQSAR enables a more systematic approach to molecular optimization, allowing medicinal chemists to make informed decisions about which fragments to retain, modify, or replace [8]. Additionally, GQSAR considers cross-terms fragment descriptors, which help identify key fragment interactions that determine activity variation—a feature particularly useful when optimizing complex molecules with multiple substituents [8]. This fragment-centric approach also aligns well with modern drug discovery paradigms that emphasize molecular efficiency and the assembly of optimal fragments into lead compounds with desired properties [22].

Implementation and Practical Applications

The implementation of GQSAR begins with the decomposition of molecules into relevant fragments, which could be substituents at various substitution sites in congeneric series of molecules or predefined chemical rules in non-congeneric sets [8]. These fragments are then encoded using appropriate descriptors, and their relationships with biological activity are modeled using statistical or machine learning techniques [22]. An advanced extension of this approach is the Pharmacophore-Similarity-based QSAR (PS-QSAR), which uses topological pharmacophoric descriptors to develop QSAR models and assesses the contribution of certain pharmacophore features encoded by respective fragments toward activity improvement or detrimental effects [8].

GQSAR has found particular utility in multi-target inhibitor design and scaffold hopping applications, where researchers need to understand how specific fragment modifications affect activity profiles across different biological targets [22]. The methodology enables the virtual generation of target inhibitors from fragment databases and supports multi-scale modeling that integrates diverse chemical and biological data [22]. By focusing on fragment contributions rather than whole-molecule properties, GQSAR facilitates a more modular approach to drug design, allowing researchers to mix and match fragments with known activity contributions to optimize multiple properties simultaneously [8]. This approach is especially valuable in the context of polypharmacology, where drugs need to interact with multiple targets with specific activity ratios, and fragment contributions can be tuned to achieve the desired selectivity profile [22].

Table 2: GQSAR Fragment Descriptors and Their Significance

| Descriptor Type | Description | Structural Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substituent Parameters | Electronic, steric, and hydrophobic parameters of substituents | Quantifies fragment contributions to molecular properties | Congeneric series optimization [8] |

| Fragment Fingerprints | Binary representation of fragment presence/absence | Identifies key fragments associated with activity | Scaffold hopping, virtual screening [8] |

| Cross-Term Fragments | Descriptors capturing interactions between fragments | Reveals synergistic or antagonistic fragment effects | Multi-parameter optimization [8] |

| Pharmacophore Fragments | Topological pharmacophoric features | Relates fragments to molecular recognition patterns | Activity cliff analysis, lead optimization [8] |

Experimental Protocol: GQSAR Model Development

Protocol Title: Group-Based QSAR Analysis for Lead Optimization

Objective: To develop a GQSAR model that quantifies the contributions of molecular fragments to biological activity for a series of congeneric compounds.

Materials and Software:

- Cheminformatics Toolkit: Python/R with appropriate chemical libraries (RDKit, ChemPy)

- Molecular Descriptor Software: Tools for calculating fragment-based descriptors

- Statistical Analysis Package: Software for regression analysis and model validation

Procedure:

Dataset Curation and Fragment Definition:

- Compile a dataset of compounds with measured biological activities

- Define the molecular scaffold common to all compounds

- Identify variable substitution sites and their corresponding fragments

- Classify fragments based on chemical characteristics and properties [8]

Fragment Descriptor Calculation:

- Calculate physicochemical properties for each fragment (hydrophobicity, steric bulk, electronic effects)

- Generate binary fingerprint descriptors for fragment presence

- Compute cross-term descriptors for fragment interactions where applicable

- Apply dimensionality reduction if needed to address multicollinearity [8]

Model Building and Validation:

- Split dataset into training and test sets (typically 70-80% for training)

- Use multiple linear regression or machine learning algorithms to build models

- Apply variable selection techniques to identify significant fragment descriptors

- Validate models using internal (cross-validation) and external validation methods [8]

Model Interpretation and Application:

- Analyze regression coefficients to quantify fragment contributions

- Identify favorable and unfavorable fragment properties for activity

- Design new compounds by combining fragments with positive contributions

- Predict activities of proposed compounds using the developed model [8]

Fragment-Based QSAR Methods

Theoretical Framework and Methodological Approaches

Fragment-Based QSAR methods represent a specialized category of QSAR modeling that focuses on the contributions of individual molecular fragments to biological activity, typically using group contribution methods or fragment descriptors [8]. The fundamental premise of these approaches is that the biological activity and physicochemical properties of a compound can be determined by the sum of the contributions of its constituent fragments, with each fragment making additive and consistent contributions regardless of the overall molecular scaffold [8]. This paradigm has established itself as a promising approach in modern drug discovery, playing a crucial role in accelerating lead optimization and reducing attrition rates in the drug development process [22].

The most established fragment-based QSAR approach is the group contribution method, where fragmentary values are determined statistically based on empirical data for known molecular properties [8]. For example, the prediction of partition coefficients (logP) can be accomplished through fragment methods (known as "CLogP" and variations), which are generally accepted as better predictors than atomic-based methods [8]. More advanced implementations include the FragOPT workflow, which uses machine learning to identify advantageous and disadvantageous fragments of molecules to be optimized by combining classification models for bioactive molecules with model interpretability methods like SHAP [25]. These fragments are then sampled within the 3D pocket of the target protein, and disadvantageous fragments are redesigned using deep learning models, followed by recombination with advantageous fragments to generate new molecules with enhanced binding affinity [25].

Applications in Contemporary Drug Discovery

Fragment-Based QSAR methods have demonstrated significant utility in various aspects of drug discovery, particularly in the early stages of lead identification and optimization. The FragOPT approach, for instance, has been successfully validated on protein targets associated with solid tumors and the SARS-CoV-2 virus, generating molecules with superior synthesizability and enhanced binding affinity compared to other fragment-based drug discovery methods [25]. This ML-driven workflow exemplifies how fragment-based approaches can optimize the initial drug discovery process, providing a more precise and efficient pathway for developing new therapeutics [25].

Another significant application of Fragment-Based QSAR is in the realm of multi-scale modeling, where different datasets based on target inhibition can be simultaneously integrated and predicted alongside other relevant endpoints such as biological activity against non-biomolecular targets, as well as in vitro and in vivo toxicity and pharmacokinetic properties [22]. This holistic approach acknowledges that drug discovery must be viewed as a multi-scale optimization process, integrating diverse chemical and biological data to serve as a knowledge generator that enables the design of potentially optimal therapeutic agents [22]. Fragment-based methods are particularly amenable to this integrated approach because their modular nature allows for the systematic optimization of multiple properties through rational fragment selection and combination [8] [25].

Comparative Analysis and Integration of QSAR Methodologies

Strategic Selection of QSAR Approaches

Each QSAR methodology offers distinct advantages and is suited to specific scenarios in the drug discovery pipeline. 3D-QSAR approaches like CoMFA and COMSIA are particularly valuable when the three-dimensional alignment of molecules is known or can be reliably predicted, and when researchers need visual guidance for structural modifications [26] [27]. These methods excel in lead optimization stages where understanding the spatial requirements for activity is crucial. GQSAR methods shine when working with structurally diverse compounds or when researchers need to understand the specific contributions of substituents at multiple sites [8]. This approach is particularly useful in library design and scaffold hopping applications. Fragment-Based QSAR methods are most appropriate for early discovery stages when exploring large chemical spaces or when applying multi-parameter optimization across diverse endpoints [22] [25].

The integration of these methodologies often yields superior results compared to relying on any single approach. For instance, 3D-QSAR models can inform fragment selection in FBDD by identifying favorable chemical features in specific spatial regions, while GQSAR can optimize substituents on scaffolds identified through fragment screening [8] [27]. Recent advances also demonstrate the value of combining these traditional QSAR approaches with modern machine learning techniques and molecular dynamics simulations to enhance predictive accuracy and account for protein flexibility [23] [25]. This integrated perspective acknowledges that drug discovery is inherently a multi-scale problem requiring insights from multiple computational approaches tailored to specific decision points in the pipeline.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of QSAR Methodologies

| Feature | 3D-QSAR | GQSAR | Fragment-Based QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Captures 3D steric and electrostatic effects | Quantifies substituent contributions | Explores large chemical spaces efficiently |

| Data Requirements | 3D structures and molecular alignment | Congeneric series with defined substituents | Diverse compounds with fragment mappings |

| Interpretability | Visual contour maps | Fragment contribution coefficients | Fragment activity rankings |

| Optimal Application Stage | Lead optimization | SAR exploration | Hit identification and early optimization |

| Complementary Techniques | Molecular docking, MD simulations | Matched molecular pair analysis | Machine learning, Free energy calculations |

Table 4: Essential Resources for QSAR Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Sybyl-X, ChemDraw | Compound construction and optimization | 3D-QSAR model development [23] |

| Cheminformatics | Schrödinger Canvas, RDKit | Molecular descriptor calculation | Chemical similarity analysis [24] |

| 3D-QSAR Specialized | OpenEye's 3D-QSAR | Binding affinity prediction using shape/electrostatics | Consensus 3D-QSAR modeling [27] |

| Fragment-Based Design | FragOPT | Fragment identification and optimization | Machine learning-driven fragment optimization [25] |

| Statistical Analysis | R, Python with scikit-learn | Model building and validation | Statistical QSAR model development [8] |

Workflow Visualization: Integrated QSAR Implementation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for implementing an integrated QSAR strategy in drug discovery:

Integrated QSAR Implementation Workflow

The exploration of 3D-QSAR, GQSAR, and Fragment-Based QSAR methodologies reveals a rich landscape of computational tools for modern drug discovery. Each approach offers unique strengths—3D-QSAR provides spatial understanding of steric and electrostatic requirements, GQSAR quantifies substituent contributions, and Fragment-Based methods enable efficient exploration of chemical space. The integration of these methodologies, complemented by advances in machine learning and molecular dynamics simulations, creates a powerful framework for rational drug design. As these computational approaches continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly vital role in addressing the challenges of efficiency, cost, and predictive accuracy in pharmaceutical development, ultimately contributing to the discovery of novel therapeutic agents for unmet medical needs.

Building and Applying Predictive Models: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is a fundamental technique in computer-aided drug design (CADD) that derives interaction features directly from the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target or a protein-ligand complex. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [28]. This approach contrasts with ligand-based methods, as it utilizes structural insights from the target protein itself to identify complementary chemical features that a ligand must possess for effective binding and biological activity [16]. The primary advantage of structure-based pharmacophore modeling lies in its ability to identify novel chemotypes without dependence on known active ligands, making it particularly valuable for targets with limited ligand information [28].

The historical development of the pharmacophore concept dates back to Paul Ehrlich in 1909, who first introduced the idea as "a molecular framework that carries the essential features responsible for a drug's biological activity" [28]. Over a century of development has expanded its meaning and applications considerably, with structure-based approaches emerging as powerful tools for rational drug design. These models abstract specific atomic arrangements into generalized chemical features, providing a template for virtual screening and ligand optimization that focuses on the essential recognition elements between a ligand and its target [1] [16].

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Core Pharmacophore Features

Structure-based pharmacophore models represent key protein-ligand interaction patterns as a collection of abstract chemical features with defined spatial relationships. The most commonly recognized pharmacophore feature types include [16] [29]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): Represents regions where a ligand can accept hydrogen bonds from protein donors.

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): Represents regions where a ligand can donate hydrogen bonds to protein acceptors.

- Hydrophobic (H): Represents aliphatic or aromatic carbon chains that participate in hydrophobic interactions.

- Positively Ionizable (PI) / Negatively Ionizable (NI): Represent groups that can become charged under physiological conditions, facilitating electrostatic interactions.

- Aromatic (AR): Represent aromatic rings capable of π-π or cation-π interactions.

- Metal Coordinating (MB): Represent atoms that can coordinate with metal ions in the binding site.

Additional feature types identified in recent advanced implementations include covalent bond (CV), cation-π interaction (CR), and halogen bond (XB) features [29]. These features are typically represented as spheres in 3D space with tolerances, and for directional features like HBA and HBD, vectors indicating the optimal interaction geometry may also be included [1].

General Workflow

The structure-based pharmacophore modeling process follows a systematic workflow that transforms protein structural information into a query for virtual screening. The key steps are illustrated below and detailed in the subsequent sections:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Model Development from a Protein-Ligand Complex

This protocol details the generation of a pharmacophore model when an experimental structure of the target protein in complex with a ligand is available, which represents the ideal scenario for obtaining highly accurate models [16].

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Source: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational methods like homology modeling [16]. The quality of the input structure directly influences the quality of the resulting pharmacophore model [16].

- Preparation Tasks:

- Add hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH.

- Assign correct protonation states to residues, especially those in the binding site.

- Repair missing side chains or loops if necessary.

- Optimize the structure using energy minimization to relieve steric clashes.

- Software Tools: Molecular operating environment (MOE), Discovery Studio, Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard.

Step 2: Binding Site Analysis

- Definition: The binding site is typically defined by the spatial coordinates of the co-crystallized ligand.

- Characterization: Analyze the chemical environment of the binding pocket, identifying key residues involved in:

- Hydrogen bonding networks

- Hydrophobic patches

- Charged or polar regions

- Metal coordination sites

- Software Tools: Tools like GRID [16] can be used to generate molecular interaction fields (MIFs) that map favorable interaction sites for different probe types.

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Ligand-Based Guidance: The bioactive conformation of the co-crystallized ligand provides direct spatial reference for positioning pharmacophore features [16].

- Feature Mapping: Convert observed protein-ligand interactions into corresponding pharmacophore features:

- Hydrogen bonds → HBA or HBD features

- Hydrophobic contacts → Hydrophobic features

- Ionic interactions → PI or NI features

- Aromatic stacking → Aromatic features

- Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion spheres (XVOL) to represent regions occupied by protein atoms where ligand atoms cannot penetrate [16]. These are crucial for representing the shape complementarity of the binding pocket.

Step 4: Feature Selection and Model Assembly

- Selection Criteria: From the initially generated features, select those that are:

- Evolutionarily conserved across related proteins

- Critical for binding energy based on mutagenesis studies

- Consistently observed in multiple complex structures if available

- Spatial Constraints: Define distance and angle tolerances between features based on the observed interactions.

Step 5: Model Validation

- Internal Validation: Ensure the model can recognize the native ligand from which it was derived.

- External Validation: Screen a small database of known actives and inactives to determine the model's enrichment factor.

- Refinement: Adjust feature definitions and tolerances based on validation results to optimize selectivity and sensitivity.

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Model Development from an Apo Protein Structure

This protocol applies when only the structure of the unliganded protein (apo form) is available, requiring prediction of potential interaction sites [16].

Step 1: Protein Preparation

- Follow the same preparation steps as in Protocol 1, with particular attention to:

- Modeling flexible side chains in the putative binding site

- Considering multiple rotameric states for binding site residues

Step 2: Binding Site Prediction

- Identification: Use computational tools to identify potential binding pockets based on:

- Geometric criteria (pocket size, depth, etc.)

- Energetic considerations (favorable interaction energy)

- Evolutionary conservation

- Software Tools: Use programs like GRID [16], LUDI [16], or other binding site detection algorithms.

Step 3: Interaction Site Analysis

- Probe Mapping: Use small molecular fragments or functional groups as probes to sample the binding pocket and identify favorable interaction sites [16].

- Feature Generation: Translate favorable interaction points into pharmacophore features:

- Hydrogen bond acceptor sites → HBD features (complementary)

- Hydrogen bond donor sites → HBA features (complementary)

- Hydrophobic regions → Hydrophobic features

- Charged regions → Opposite charge features

Step 4: Model Assembly and Refinement

- Spatial Organization: Arrange features based on their relative positions in the binding site.

- Selectivity Optimization: Compare with binding sites of anti-targets (e.g., related proteins with undesired activity) to incorporate discriminatory features.

- Consensus Modeling: If multiple binding site conformations are available, generate separate models or create a merged consensus model.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of structure-based pharmacophore modeling requires access to specialized software tools and databases. The table below summarizes essential resources for conducting these studies:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Type | Examples | Key Functionality | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [16] | Repository of experimental 3D structures of proteins and complexes | Public |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Catalyst [30], LigandScout [30], PHASE [28], MOE | Model generation, visualization, and virtual screening | Commercial |

| Binding Site Detection Tools | GRID [16], LUDI [16] | Identification and characterization of ligand binding sites | Commercial/Academic |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | ZINCPharmer [30], Pharmer [30] | Large-scale screening of compound libraries using pharmacophore queries | Public/Commercial |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC [31] [29] | Curated databases of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Public |

Recent Advances and Integration with Artificial Intelligence

The field of structure-based pharmacophore modeling has evolved significantly with the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques, addressing traditional limitations and expanding applications.

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Recent approaches have leveraged deep learning to create more sophisticated pharmacophore models that account for protein flexibility and complex interaction patterns:

- DiffPhore Framework: A knowledge-guided diffusion model for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping that utilizes ligand-pharmacophore matching knowledge to guide ligand conformation generation. This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in predicting ligand binding conformations, surpassing traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods [29].

- dyphAI: An innovative approach integrating machine learning models with ligand-based and complex-based pharmacophore models into a pharmacophore model ensemble. This method captures key protein-ligand interactions and has been successfully applied to identify novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitors with experimental validation [31].

- BCL Toolkit Enhancements: The BioChemical Library has incorporated structure-based scoring functions that can be decomposed into human-interpretable pharmacophore maps, bridging the gap between complex machine learning predictions and medicinal chemistry intuition [32].

Addressing Protein Flexibility

Traditional structure-based pharmacophore models often neglected the dynamic nature of protein structures. Recent advances address this limitation through:

- Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling: Generating multiple pharmacophore models from different conformational states of the target protein obtained through molecular dynamics simulations [31].

- Dynamic Pharmacophores: Incorporating protein flexibility by tracing the evolution of pharmacophore features during molecular dynamics simulations, creating time-dependent pharmacophore models [28].

The integration of these advanced computational approaches has significantly expanded the applications of structure-based pharmacophore modeling in modern drug discovery, particularly for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions and allosteric sites [1].

Applications in Drug Discovery

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling serves as a versatile tool with multiple applications throughout the drug discovery pipeline, significantly enhancing the efficiency of lead identification and optimization processes.

Table 2: Key Applications of Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling in Drug Discovery

| Application | Description | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening | Using pharmacophore queries to search large chemical databases and identify potential hit compounds [1] [16] [28] | Reduces chemical space to be screened experimentally; identifies diverse chemotypes |

| Lead Optimization | Analyzing structure-activity relationships to guide chemical modifications [1] [28] | Rationalizes potency and selectivity changes; suggests favorable modifications |

| Scaffold Hopping | Identifying novel molecular frameworks that maintain key interactions [16] | Expands intellectual property space; overcomes toxicity or bioavailability issues |

| De Novo Design | Generating completely novel chemical structures that match the pharmacophore [28] | Creates patentable novel chemotypes with optimized properties |

| Multi-Target Drug Design | Designing compounds that match pharmacophores of multiple targets [28] | Enables polypharmacology; designs drugs for complex diseases |

Application Workflow in Virtual Screening

The typical workflow for applying structure-based pharmacophore models in virtual screening involves multiple steps that integrate various computational approaches, as illustrated below:

Success Stories

Recent studies demonstrate the successful application of structure-based pharmacophore modeling in various drug discovery campaigns:

- Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: The dyphAI approach identified 18 novel AChE inhibitor candidates from the ZINC database. Experimental validation confirmed that several compounds exhibited IC₅₀ values lower than or equal to the control drug galantamine, demonstrating the power of integrated pharmacophore approaches for target-specific inhibitor discovery [31].

- Kinase Inhibitors: Structure-based pharmacophore models have been successfully developed for various kinase targets, including spleen tyrosine kinase and transforming growth factor-β type I receptor (ALK5), leading to the identification of novel inhibitor chemotypes with confirmed activity [28].

- GPCR Targets: Advanced pharmacophore modeling techniques have been applied to G-protein coupled receptors, successfully identifying allosteric modulators despite the challenges of structural flexibility and limited structural information [32].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, structure-based pharmacophore modeling faces several challenges that represent opportunities for future methodological development. A primary limitation is the accurate representation of protein flexibility and the induced-fit effects that occur upon ligand binding [28]. While molecular dynamics simulations can generate multiple receptor conformations, this approach remains computationally demanding and may not capture all relevant conformational states. Additionally, the abstraction of specific atomic interactions into generalized features inevitably results in some loss of chemical information, which can affect model precision [1].

Future advancements are likely to focus on several key areas. The integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning will continue to enhance model generation and validation, with techniques like the DiffPhore framework representing the vanguard of this trend [29]. Improved handling of solvation effects and explicit water molecules in pharmacophore models will increase their accuracy, as water-mediated interactions play crucial roles in molecular recognition. Furthermore, the development of standardized validation metrics and benchmarks will facilitate more rigorous comparison between different pharmacophore modeling approaches and their integration with other structure-based drug design methods [28] [32].

As these computational techniques mature, structure-based pharmacophore modeling is poised to become increasingly central to drug discovery efforts, particularly for challenging target classes where traditional methods have shown limited success. The continued synergy between computational predictions and experimental validation will ensure the ongoing refinement and application of these powerful tools in rational drug design [31].