Principles of Rational Drug Design: A Modern Framework for Targeted Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and practices of Rational Drug Design (RDD), a systematic approach that leverages knowledge of biological targets to develop new medications.

Principles of Rational Drug Design: A Modern Framework for Targeted Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and practices of Rational Drug Design (RDD), a systematic approach that leverages knowledge of biological targets to develop new medications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational concepts and target identification to advanced computational methodologies like Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Drug Design. It further addresses critical challenges in optimization, the rigorous process of preclinical and clinical validation, and a comparative analysis with traditional discovery methods. By synthesizing current literature and recent technological advances, this guide serves as a resource for streamlining the drug discovery pipeline and developing safer, more effective therapeutics.

What is Rational Drug Design? Foundations and Core Concepts

Rational Drug Design (RDD) represents a fundamental shift from traditional, empirical drug discovery methods to a targeted, knowledge-driven approach. This methodology uses three-dimensional structural information about biological targets and computational technologies to design therapeutic agents with specific desired properties, moving beyond the trial-and-error paradigm that has long dominated pharmaceutical development [1]. The core principle of RDD is the strategic modification of functional chemical groups based on considerations of structure-activity relationships (SARs) to improve drug candidate effectiveness [1]. This approach has evolved significantly since its initial formalization in the 1950s, with landmark successes in the 1970s and 1980s including cholesterol-lowering lovastatin and antihypertensive captopril, which remain in clinical use today [1].

The contemporary landscape of drug discovery has been transformed by recent advancements in bioinformatics and cheminformatics, creating unprecedented opportunities for RDD [2]. Key techniques including structure- and ligand-based virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulations, and artificial intelligence-driven models now allow researchers to explore vast chemical spaces, investigate molecular interactions, predict binding affinity, and optimize drug candidates with remarkable accuracy and efficiency [2]. These computational methods complement experimental techniques by accelerating the identification of viable drug candidates and refining lead compounds, ultimately reducing the resource-intensive nature of drug discovery, which traditionally costs approximately USD 2.6 billion and takes over 12 years to bring a new therapeutic agent to market [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies of Rational Drug Design

The Conceptual Framework of RDD

Rational Drug Design operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from traditional approaches. At its core, RDD relies on the concept that understanding the molecular basis of disease enables the deliberate design of interventions that specifically modulate pathological processes. This approach begins with identifying a biological target—such as DNA, RNA, or a specific protein—that plays a particular role in disease development [1]. The process then proceeds to identify hit compounds that can interact with the chosen biological target, followed by optimization of their chemical structures and drug properties to develop lead compounds [1].

The methodological ideal of RDD involves continuous reinforcement between theoretical insights into drug-receptor interactions and hands-on drug testing [1]. This iterative process depends heavily on molecular modeling used in conjunction with optimization cycles that rely on structure-activity relationships (SARs) to strategically modify functional chemical groups with the aim of improving drug candidate effectiveness [1]. The well-established method of bioisosteric replacement exemplifies this approach, involving finding the balance between maintaining desired biological activity and optimizing drug-related properties that influence efficacy, such as solubility, lipophilicity, stability, selectivity, non-toxicity, and absorption [1].

Key Computational Methods in Modern RDD

Modern RDD employs a sophisticated array of computational methods that have revolutionized early-stage drug discovery:

- Structure-Based Virtual Screening: This method uses three-dimensional structural information about biological targets to computationally screen large libraries of compounds for potential binding affinity and biological activity [2].

- Ligand-Based Virtual Screening: When structural information about the target is limited, this approach uses known active compounds to identify new candidates with similar properties [2].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: These simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into molecular interactions, binding mechanisms, and conformational changes [2].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: This technique identifies the essential spatial arrangement of molecular features necessary for biological activity, serving as a template for identifying or designing new active compounds [1].

- Artificial Intelligence-Driven Models: AI and machine learning algorithms now play an important role in predicting key properties such as binding affinity and toxicity, contributing to more informed decision-making early in the drug discovery process [2].

The Emergence of Informatics-Driven Approaches

A significant advancement in modern RDD is the concept of the "informacophore," which extends traditional pharmacophore models by incorporating data-driven insights derived not only from SARs but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [1]. This fusion of structural chemistry with informatics enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization. Unlike traditional pharmacophore models rooted in human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition, informacophores leverage the ability of machine learning algorithms to process vast amounts of information rapidly and accurately, identifying hidden patterns beyond human capacity [1].

The development of ultra-large, "make-on-demand" or "tangible" virtual libraries has significantly expanded the range of accessible drug candidate molecules, with suppliers like Enamine and OTAVA offering 65 and 55 billion novel make-on-demand molecules respectively [1]. To screen such vast chemical spaces, ultra-large-scale virtual screening for hit identification becomes essential, as direct empirical screening of billions of molecules is not feasible [1].

Table 1: Key Computational Methods in Rational Drug Design

| Method | Primary Function | Data Requirements | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening | Identify compounds with binding affinity to target | 3D structure of biological target | Hit identification, lead optimization |

| Ligand-Based Virtual Screening | Identify compounds similar to known actives | Chemical structures of known active compounds | Hit expansion, scaffold hopping |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Model molecular interactions over time | Atomic coordinates, force field parameters | Binding mechanism analysis, conformational sampling |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Define essential features for biological activity | Active compounds, optionally target structure | Virtual screening, de novo design |

| AI/ML Models | Predict compound properties and activity | Large datasets of compounds with annotated properties | Property prediction, chemical space exploration |

Experimental Validation: Bridging In Silico Predictions and Therapeutic Reality

While computational tools and AI have revolutionized early-stage drug discovery, these in silico approaches represent only the starting point of a much broader experimental validation pipeline [1]. Theoretical predictions—including target binding affinities, selectivity, and potential off-target effects—must be rigorously confirmed through biological functional assays to establish real-world pharmacological relevance [1]. These assays, which include enzyme inhibition, cell viability, reporter gene expression, or pathway-specific readouts conducted in vitro or in vivo, offer quantitative, empirical insights into compound behavior within biological systems [1].

The critical data provided by biological functional assays validate or challenge AI-generated predictions and provide feedback into SAR studies, guiding medicinal chemists to design analogues with improved efficacy, selectivity, and safety [1]. This iterative feedback loop—spanning prediction, validation, and optimization—is central to the modern drug discovery process [1]. Advances in assay technologies, including high-content screening, phenotypic assays, and organoid or 3D culture systems, offer more physiologically relevant models that enhance translational relevance and better predict clinical success [1].

Several notable drug discovery case studies exemplify this synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation:

- Baricitinib: A repurposed JAK inhibitor identified by BenevolentAI's machine learning algorithm as a candidate for COVID-19, which required extensive in vitro and clinical validation to confirm its antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects, ultimately supporting its emergency use authorization [1].

- Halicin: A novel antibiotic discovered using a neural network trained on a dataset of molecules with known antibacterial properties; biological assays were crucial to confirming its broad-spectrum efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens in both in vitro and in vivo models [1].

- Vemurafenib: A BRAF inhibitor for melanoma initially identified via high-throughput in silico screening targeting the BRAF (V600E)-mutant kinase, with computational promise validated through cellular assays measuring ERK phosphorylation and tumor cell proliferation [1].

These cases underscore a fundamental principle in modern drug development: without biological functional assays, even the most promising computational leads remain hypothetical. Only through experimental validation is therapeutic potential confirmed, enabling medicinal chemists to make informed decisions in the iterative process of drug optimization [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for RDD Experimental Protocols

The experimental validation of computationally designed drug candidates requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in rational drug design workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Rational Drug Design Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in RDD | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Large Virtual Compound Libraries | Provide vast chemical space for virtual screening | Enamine (65 billion compounds), OTAVA (55 billion compounds) for hit identification [1] |

| Biological Functional Assays | Validate computational predictions empirically | Enzyme inhibition, cell viability, reporter gene expression assays [1] |

| High-Content Screening Systems | Enable multiparametric analysis of compound effects | Phenotypic screening, mechanism of action studies [1] |

| Organoid/3D Culture Systems | Provide physiologically relevant disease models | Enhanced translational prediction during preclinical validation [1] |

| ADMET Profiling Assays | Evaluate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity | In vitro and in vivo assessment of drug candidate properties [1] |

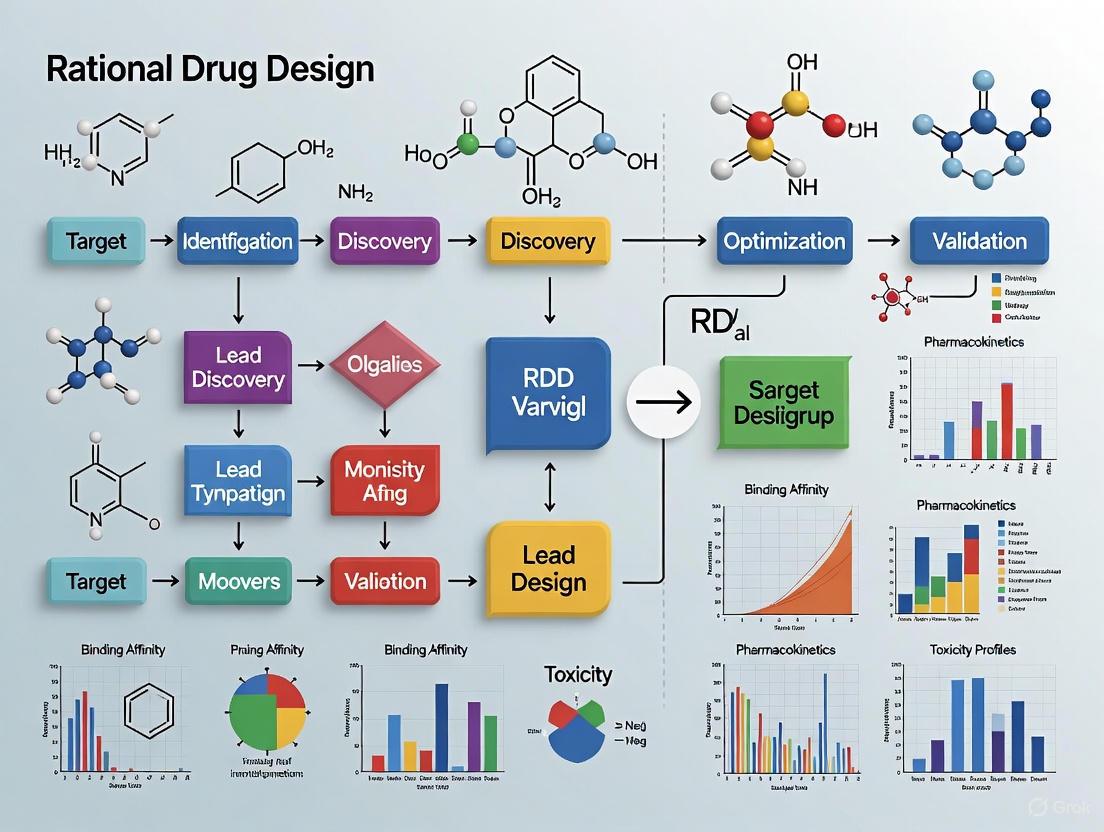

Visualization of RDD Workflows and Conceptual Frameworks

Rational Drug Design Methodology Workflow

Informatics-Driven Drug Discovery Paradigm

Rational Drug Design has evolved from its origins in theoretical drug-receptor interactions to become an informatics-driven discipline that systematically addresses the complexities of drug discovery. The integration of computational prediction with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for identifying and optimizing therapeutic agents, significantly advancing beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in terms of accuracy, interpretability, and computational power requirements for current RDD methodologies [2].

The future of RDD lies in enhancing the synergy between computational and experimental approaches, with emerging technologies such as AI-driven models, structural bioinformatics, and advanced simulation techniques playing increasingly important roles [2]. As these methods continue to evolve, rational drug design is poised to further accelerate the drug development pipeline, reduce costs, and improve the success rate of bringing new therapeutics to market. The continued refinement of informacophore approaches and the expansion of accessible chemical spaces will likely drive innovations in targeted therapeutic development, ultimately enabling more precise and effective treatments for complex diseases.

In the field of modern pharmaceutical sciences, biological targets represent the foundational cornerstone upon which rational drug design (RDD) is built. These targets, predominantly proteins, enzymes, and receptors, are biomolecules within the body that specifically interact with drugs to regulate disease-related biological processes [3]. The identification and characterization of these targets form the most crucial and foundational step in drug discovery and development, largely determining the efficiency and success of pharmaceutical research [3] [4]. Rational drug design strategically exploits the detailed recognition and discrimination features associated with the specific arrangement of chemical groups in the active site of target macromolecules, enabling researchers to conceive new molecules that can optimally interact with these proteins to block or trigger specific biological actions [5].

Biological targets can be categorized based on their functions and mechanisms of action into several classes, including enzymes, receptors, ion channels, transport proteins, and nucleic acids [3]. The critical role these targets play in cellular signal transduction, metabolic pathways, and gene expression establishes their central position in drug discovery. The lock-and-key model, initially proposed by Emil Fischer in 1890, and its extension to the induced-fit theory by Daniel Koshland in 1958, provide conceptual frameworks for understanding how biological 'locks' (targets) possess unique stereochemical features that allow precise interaction with 'keys' (drug molecules) [5]. This molecular recognition process forms the fundamental basis of rational drug design, wherein both ligand and target may mutually adapt through conformational changes to achieve an optimal fit [5].

Table 1: Major Classes of Biological Targets in Drug Discovery

| Target Class | Key Characteristics | Therapeutic Significance | Example Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Catalyze biochemical reactions; often have well-defined active sites | Inhibition or activation modulates metabolic pathways | Kinases, Proteases, Polymerases |

| Receptors | Transmembrane or intracellular proteins that bind signaling molecules | Regulate cellular responses to hormones, neurotransmitters | GPCRs, Nuclear Receptors |

| Ion Channels | Gate flow of ions across cell membranes | Control electrical signaling and cellular homeostasis | Voltage-gated Na+ channels, GABA receptors |

| Transport Proteins | Facilitate movement of molecules across biological barriers | Affect drug distribution and nutrient uptake | Transporters for neurotransmitters, nutrients |

Principles of Rational Drug Design Approaches

Rational drug design represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to a methodical process grounded in structural and mechanistic understanding of target molecules. This approach proceeds through three fundamental steps: design of compounds that conform to specific structural requirements, synthesis of these molecules, and rigorous biological testing, with further rounds of refinement and optimization based on results [5]. The overarching goal of RDD is to lessen drug discovery duration and expenses through strategic narrowing of drug-like compounds in the discovery pipeline, addressing the prohibitive costs (2-3 billion dollars) and extended timelines (12-15 years) associated with traditional drug development [4].

Two primary methodologies dominate rational drug design: structure-based (receptor-based) and pharmacophore-based (ligand-based) approaches. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) directly exploits the three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or NMR, or through computational approaches like homology modeling [4] [5]. This "direct" design approach allows researchers to visualize and utilize detailed 3D features of the active site, introducing appropriate functionalities in designed ligands to create favorable interactions [5]. The key steps in SBDD include preparation of the protein structure, identification of binding sites, ligand preparation, and docking with scoring functions to evaluate potential interactions [4].

In contrast, pharmacophore-based drug design serves as an indirect approach employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable [5]. This method extracts critical information from the stereochemical and physicochemical features of known active molecules, generating hypotheses about ligand-receptor interactions through analysis of structural variations across compound series [5]. The strategy of "molecular mimicry" enables researchers to position the 3D relative location of structural elements recognized as necessary in active molecules into new chemical entities, facilitating the design of compounds that mimic natural substrates, hormones, or cofactors like ATP, dopamine, histamine, and estradiol [5]. When applied to peptides, this approach extends to "peptidomimetics," designing non-peptide molecules that mimic peptide functionality while overcoming developmental challenges associated with peptide-based drugs [5].

The ideal scenario in rational drug design involves synergistic integration of both structure-based and ligand-based approaches, where promising docked molecules designed through favorable interactions with the target protein are compared to active structures, and interesting mimics of active compounds are docked into the protein to assess convergent conclusions [5]. This synergy substantially accelerates the discovery process but depends critically on establishing correct binding modes of ligands within the target's active site [5].

Target Identification and Validation Strategies

The initial stages of drug discovery involve the precise identification and validation of disease-modifying biological targets, a process that has been revolutionized by advanced technologies and methodologies. Drug targets typically refer to biomolecules within the body that can specifically bind with drugs to regulate disease-related biological processes, while novel targets encompass biomolecules related to disease but not yet successfully targeted in clinical settings [3]. These novel targets include newly discovered unverified biomolecules, proteins recently associated with disease mechanisms, targets with mechanistic support but lacking known modulators, known targets repurposed for new indications, and synergistic or combinatorial targets with at least one unverified component [3]. Additionally, "undruggable" proteins—those characterized by flat functional interfaces lacking defined pockets for ligand interaction—represent a significant category of challenging targets [6].

Target identification has entered a new era with the integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics technologies. AI-based approaches can be trained on large-scale biomedical datasets to perform data-driven, high-throughput analyses, integrating multimodal data such as gene expression profiles, protein-protein interaction networks, chemical structures, and biological pathways to perform comprehensive inference [3]. Genomics approaches leverage AI methods to mine multi-layered information including genome-wide variant effects, functional annotations, gene interactions, expression and regulation, epigenetic modifications, protein-DNA interactions, and gene-disease associations [3]. Single-cell omics technologies represent a cutting-edge advancement that enables resolution of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles at the single-cell level, systematically characterizing cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell subsets, and dissecting dynamic cellular processes and spatial distributions [3].

Perturbation omics provides a critical causal reasoning foundation for target identification by introducing systematic perturbations and measuring global molecular responses [3]. This framework includes genetic-level perturbations (single-gene and multi-gene perturbations) and chemical-level perturbations (small molecules and diverse compound libraries), with AI techniques such as neural networks, graph neural networks, causal inference models, and generative models significantly enhancing analytical power to simulate interventions and reveal functional targets [3]. Structural biology AI models, including tools like AlphaFold for protein structure prediction, complement these approaches by providing atomic-level structural insights and dynamic conformational analyses essential for target identification [3].

Despite these technological advancements, target discovery still faces substantial challenges, including complex disease mechanisms involving multiple signaling pathways and gene networks, data complexity and integration challenges with heterogeneous and noisy omics data, target validation difficulties requiring substantial experimental efforts, and challenges in clinical translation where promising targets in vitro or in animal models may not translate into clinical efficacy [3].

Table 2: Key Databases and Tool Platforms for Target Identification

| Database Category | Primary Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Omics Databases | Provide large-scale cross-omics and cross-species data | Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics databases [3] |

| Structure Databases | Archive 3D structural information of biological macromolecules | Protein Data Bank (PDB), structural classification databases [3] |

| Knowledge Bases | Construct multi-dimensional association networks of genes, diseases, and drugs | Disease-gene association databases, drug-target interaction databases [3] |

"Undruggable" Targets: Challenges and Innovative Solutions

A significant frontier in rational drug design involves tackling "undruggable" targets—proteins characterized by large, complex structures or functions that are difficult to interfere with using conventional drug design strategies [6]. These challenging targets typically lack defined hydrophobic pockets for ligand binding, instead featuring shallow, polar surfaces that resist traditional small-molecule interaction [6]. The term "undruggable" particularly applies to several protein classes: Small GTPases (including KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS), Phosphatases (both protein tyrosine phosphatases and protein serine/threonine phosphatases), Transcription factors (such as p53, Myc, estrogen receptor, and androgen receptor), specific Epigenetic targets, and certain Protein-Protein Interaction interfaces with flat interaction surfaces [6].

Among these, KRAS represents a paradigmatic example of historical "undruggability." As the most frequently mutated oncogene protein with varying mutation rates in different solid tumors, KRAS experienced prolonged clinical drug vacancy due to its shallow surface pocket with undesired polarity [6]. The protein alternates between inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound states, regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors and GTPase activating proteins [6]. The breakthrough came in 2021 with the FDA approval of sotorasib, a covalent KRASG12C inhibitor for non-small cell lung cancer, validating that targeting "undruggable" proteins is achievable through innovative approaches [6].

Several strategic frameworks have emerged to address these challenging targets:

Covalent Regulation: Covalent inhibitors bind to amino acid residues of target proteins through covalent bonds formed by mildly reactive functional groups, conferring additional affinity compared to non-covalent inhibitors [6]. These inhibitors offer advantages of sustained inhibition and longer residence time, as the covalently bound target remains continuously inhibited until protein degradation and regeneration [6]. This approach reduces dosage requirements, improves patient compliance, and can overcome some resistance mechanisms.

Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD): This groundbreaking advancement employs small molecules to tag undruggable proteins for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system or autophagic-lysosomal system [7]. Unlike traditional inhibitors that aim to block protein activity, TPD technologies completely remove disease-associated proteins from the cellular environment, providing a novel therapeutic paradigm for conditions where conventional small molecules have fallen short [7]. Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras represent a prominent example of this approach.

Allosteric Inhibition: Rather than targeting traditional active sites, allosteric inhibitors bind to alternative, often less conserved sites on protein surfaces, inducing conformational changes that disrupt protein function [6]. This approach offers enhanced selectivity and the potential to overcome resistance mutations that affect active-site binding.

DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs): This technology allows for high-throughput screening of vast chemical libraries by utilizing DNA as a unique identifier for each compound, facilitating simultaneous testing of millions of small molecules against biological targets [7]. DELs enable efficient exploration of chemical diversity and streamline identification of potential drug candidates for challenging targets.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

The drug discovery pipeline employs a diverse array of experimental and computational methodologies to identify and validate biological targets and their modulators. Structure-based drug design relies heavily on techniques such as X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance to elucidate the three-dimensional structures of target proteins [4]. These structural insights provide the foundation for molecular docking simulations, which computationally predict the binding orientation and affinity of small molecules within target binding sites [4]. Molecular dynamics simulations further extend these static pictures by modeling the dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes under physiological conditions, providing critical information about binding stability and conformational changes [3].

Advanced computational approaches have revolutionized target identification and validation. Computer-Aided Drug Design employs computational methods to predict the binding affinity of small molecules to specific targets, significantly reducing the time and resources required for experimental screening [7]. With advancements in artificial intelligence, CADD has become increasingly sophisticated, enabling researchers to simulate complex biological interactions and refine drug design more effectively [7]. AI-driven structure prediction tools, such as AlphaFold, generate static structural models that provide the basis for systematically annotating potential binding sites across proteomes [3]. These models serve as initial conformations for AI-enhanced molecular dynamics simulations, which extend simulation timescales while maintaining atomic resolution, enabling identification of cryptic binding pockets and characterization of allosteric regulation mechanisms [3].

Fragment-based drug discovery represents another powerful approach that leverages stochastic screening and structure-based design to identify small molecular fragments that bind weakly to target proteins, which are then optimized into high-affinity ligands [6]. Virtual screening complements this approach through in silico screening techniques premised on the lock-and-key model of drug-target compatibility, rapidly evaluating enormous chemical libraries against target structures [6]. Click chemistry has emerged as a transformative experimental methodology that streamlines the synthesis of diverse compound libraries through highly efficient and selective reactions, particularly the Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition that selectively produces 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles under mild conditions [7]. This modular approach allows straightforward incorporation of various functional groups, facilitating optimization of lead compounds and enabling creation of complex structures from simple precursors [7].

The emerging paradigm of retro drug design represents a fundamental shift in computational approach. Unlike traditional forward approaches, RDD begins from multiple desired target properties and works backward to generate "qualified" compound structures [8]. This AI strategy utilizes traditional predictive models trained on experimental data for target properties, employing an atom typing-based molecular descriptor system, followed by Monte Carlo sampling to find solutions in the chemical space defined by the target properties, with deep learning models employed to decode molecular structures from these solutions [8].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, Cryo-EM | Protein structure determination, ligand binding analysis [4] |

| Computational Modeling | Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics simulations, AI-based structure prediction | Binding pose prediction, protein dynamics, binding affinity calculations [3] [4] |

| Compound Screening | DNA-encoded libraries (DELs), Fragment-based screening, High-throughput screening | Hit identification, lead compound discovery [7] [6] |

| Chemical Synthesis | Click chemistry, Combinatorial chemistry, Medicinal chemistry optimization | Compound library synthesis, lead optimization [7] |

| Omics Technologies | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Single-cell omics | Target identification, biomarker discovery, mechanism of action studies [3] |

| AI and Data Science | Machine learning models, Deep neural networks, Multi-modal AI integration | Predictive modeling, chemical space exploration, drug property optimization [3] [8] |

Biological targets—proteins, enzymes, and receptors—maintain their critical role as the foundation of rational drug design, with their identification and validation remaining the most crucial step in the drug discovery process. The field has witnessed remarkable progress in methodologies to approach these targets, from structure-based and ligand-based design to innovative strategies for previously "undruggable" targets. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning across all stages of target identification and validation represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to navigate the complex landscape of disease mechanisms with unprecedented precision and efficiency [3].

The future of biological target exploration in rational drug design will likely focus on several key areas. Multimodal AI approaches that integrate structural biology and systems biology will become increasingly important, combining atomic-resolution insights into target conformations with dynamic cellular data to reveal physiological relevance [3]. The convergence of advanced technologies such as targeted protein degradation, covalent inhibition strategies, and DNA-encoded libraries with traditional approaches will expand the druggable genome, potentially bringing challenging target classes like transcription factors and phosphatases into therapeutic reach [7] [6]. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on patient-specific variations and personalized medicine will drive need for better understanding of how individual genetic differences affect target vulnerability and drug response.

As these advancements continue to mature, the drug discovery pipeline is poised to become more efficient, predictive, and successful. The integration of large-scale omics data, real-world evidence, and sophisticated computational models will enable more informed decisions in target selection and validation, potentially reducing the high attrition rates that have long plagued pharmaceutical development. Through continued innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration, the field of rational drug design will strengthen its foundational principle: that a deep understanding of biological targets remains the most direct path to transformative therapies.

Rational Drug Design (RDD) represents a foundational shift in pharmaceutical development, moving from traditional trial-and-error approaches to a precise, scientific methodology based on the knowledge of a biological target and its role in disease [9]. This inventive process focuses on the design of molecules that are complementary in shape and charge to their biomolecular target, typically a protein or nucleic acid, to modulate its function and provide a therapeutic benefit [5] [9]. The core principle of RDD is the exploitation of the detailed recognition features associated with the specific arrangement of chemical groups in the active site of a target macromolecule, allowing researchers to conceive new molecules that can optimally interact with the protein to block or trigger a specific biological action [5].

The paradigm of rational drug design is often described as reverse pharmacology because it starts with the hypothesis that modulating a specific biological target will have therapeutic value, in contrast to phenotypic drug discovery which begins with observing a therapeutic effect and later identifying the target [9]. RDD integrates a vast array of scientific disciplines including molecular biology, bioinformatics, structural biology, and medicinal chemistry, aiming to make drug development more accurate, efficient, cost-effective, and time-saving [10]. This meticulous approach makes it possible to develop drugs with optimal safety and effectiveness, thereby transforming therapeutic strategies for combating diseases [10].

Core Principles of Rational Drug Design

Molecular Recognition and Binding Models

The theoretical foundation of rational drug design rests on the principles of molecular recognition—the specific interaction between two or more molecules through non-covalent bonding [5]. These precise recognition and discrimination processes form the basis of all biological organization and regulation.

Two fundamental models describe these interactions:

- Lock-and-Key Model: Proposed by Emil Fischer in 1890, this model suggests that a substrate (key) fits precisely into the active site of a macromolecule (lock), with the biological 'locks' possessing unique stereochemical features necessary for their function [5].

- Induced-Fit Model: Daniel Koshland's 1958 extension of Fischer's model accounts for the conformational changes that occur in both the ligand and target macromolecule during recognition, proposing that both parties mutually adapt through small structural adjustments until an optimal fit is achieved [5].

Approaches to Rational Drug Design

Rational drug design implementation follows two primary methodological approaches, often used synergistically:

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): Also called receptor-based or direct drug design, this approach relies on knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the biological target obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), or NMR spectroscopy [5] [9] [11]. When an experimental structure is unavailable, researchers may create a homology model of the target based on the experimental structure of a related protein [9]. This approach allows medicinal chemists to design candidate drugs that are predicted to bind with high affinity and selectivity to the target using interactive graphics and computational analysis [9].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD): When the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is not available, researchers employ this indirect approach, which relies on knowledge of other molecules (ligands) that bind to the biological target of interest [5] [9]. These known active molecules are used to derive either a pharmacophore model (defining the minimum necessary structural characteristics a molecule must possess to bind to the target) or a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model, which correlates calculated properties of molecules with their experimentally determined biological activity [9].

The most effective drug discovery projects typically exploit both approaches synergistically, using the structural knowledge from SBDD to guide modifications while leveraging the activity data from LBDD to validate design decisions [5].

Step-by-Step Rational Drug Design Process

Target Identification and Validation

The rational drug design process begins with the critical initial phase of identifying and validating a suitable biological target.

Target Identification involves pinpointing a specific biomolecule (typically a protein or nucleic acid) that plays a key role in the disease process [10] [12]. A "druggable" target must be accessible to the putative drug molecule and, upon binding, elicit a measurable biological response [12]. Various methods are employed for target identification:

- Genomics and Data Mining: Using bioinformatics approaches to analyze available biomedical data, including publications, patent information, gene expression data, and genetic associations to identify and prioritize potential disease targets [10] [12].

- Proteomics: Examining protein profiles in diseased cells to discover potential target molecules [10].

- Phenotypic Screening: Identifying disease-relevant targets through observation of phenotypic changes in cellular or animal models [12].

Target Validation establishes the relevance of the identified biological target in the disease context and confirms that its modulation will produce the desired therapeutic effect [10] [12]. Well-validated targets decrease the risks associated with subsequent drug discovery stages [10]. Key validation techniques include:

- Genetic Techniques: Gene knockout, knock-in, or RNA interference (RNAi) to modulate target expression and observe phenotypic consequences [10] [12].

- Antisense Technology: Using chemically modified oligonucleotides complementary to target mRNA to block synthesis of the encoded protein [12].

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Employing highly specific antibodies to neutralize target function, particularly for cell surface and secreted proteins [12].

- Chemical Genomics: Applying small tool molecules to functionally modulate potential targets in a systematic manner [12].

Table 1: Primary Methods for Target Identification and Validation

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Approaches | Data mining, genetic association studies, mRNA expression analysis | Identifying targets linked to disease through genetic evidence | Provides correlation but not always functional validation |

| Proteomic Methods | Protein profiling, mass spectroscopy, phage-display antibodies | Discovering proteins highly expressed in disease states | Directly identifies protein targets |

| Genetic Manipulation | Gene knockout, knock-in, RNAi, siRNA | Establishing causal relationship between target and disease | Can produce compensatory mechanisms; expensive and time-consuming |

| Biochemical Tools | Monoclonal antibodies, antisense oligonucleotides | Highly specific target modulation in physiological contexts | Antibodies limited to extracellular targets; oligonucleotides have delivery challenges |

Lead Discovery

Once a target is validated, the lead discovery phase focuses on identifying initial 'hit' compounds with promising characteristics that can potentially be developed into drug candidates [10]. These hit compounds are small molecules that demonstrate both the capacity to interact effectively with the validated drug target and the potential for structural modification to optimize efficacy, safety, and metabolic stability [10].

Multiple strategies are employed for lead discovery:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): This traditional method involves experimentally testing large libraries of compounds (often hundreds of thousands) for activity against the target using automated assays [10] [12].

- Virtual Screening: Using computational methods to discover new drug candidates by screening large compound libraries in silico [10] [9]. Molecular docking programs predict how small molecules in a library might bind to the target structure [9] [11].

- Fragment-Based Lead Discovery: Identifying smaller, less complex molecules that bind weakly to the drug target and then combining or growing them to produce a lead compound with higher affinity [10].

- Structure-Based Design: Using the three-dimensional structure of the biological target to find or design compounds that will interact with it [10].

Contemporary approaches are increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning to accelerate this process. Recent work demonstrates that integrating pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data can boost hit enrichment rates by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods [13].

Diagram 1: Lead Discovery Workflow in Rational Drug Design. This flowchart illustrates the primary pathways for identifying hit compounds depending on the availability of structural information for the biological target.

Lead Optimization

Lead optimization is a crucial phase where initial hit compounds are refined and enhanced to improve their drug-like properties while reducing undesirable characteristics [10]. This process aims to enhance the therapeutic index of potential drug candidates by improving attributes such as potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and pharmacokinetic profiles while diminishing potential off-target effects and toxicity [10].

Key methods employed in lead optimization include:

- Molecular Modeling: Enables visual analysis and manipulation of lead compounds to understand their three-dimensional properties and interactions with the target [10].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Studies: Uses statistical methods to correlate structural features of compounds with their biological activity, enabling prediction of properties for new analogs [10] [14] [15]. Modern QSAR incorporates machine learning algorithms and advanced molecular descriptors to improve predictive accuracy [14] [1].

- Bioisosteric Replacement: A method for strategically replacing certain functional groups in the lead compound with alternatives that have similar physicochemical properties, often without significantly altering the drug's biological activity [10] [1]. This approach helps maintain desired activity while optimizing other drug properties.

- Structure-Based Optimization: Using the three-dimensional structure of the target to guide specific modifications that enhance binding affinity and selectivity [9] [11].

The lead optimization process typically involves multiple iterative Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycles, where compounds are designed, synthesized, tested, and analyzed with each iteration informing the next design phase [13]. Advanced approaches are now compressing these traditionally lengthy cycles from months to weeks through AI-guided retrosynthesis and high-throughput experimentation [13].

Table 2: Key Methodologies in Lead Optimization

| Methodology | Primary Function | Technical Approaches | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | Elucidate how structural changes affect biological activity | Systematic analog synthesis, biological testing, pattern recognition | Identification of critical functional groups and structural elements |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Quantitatively predict biological activity from molecular structure | Statistical modeling, machine learning, molecular descriptor calculation | Predictive models for activity, selectivity, and ADMET properties |

| Molecular Docking | Predict binding orientation and affinity of ligands | High-throughput virtual screening, high-precision docking, ensemble docking | Binding poses, estimated binding energies, interaction patterns |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Study ligand-receptor interactions under dynamic conditions | Unbiased MD, steered MD, umbrella sampling | Binding stability, conformational changes, transient interactions |

Experimental Validation and Preclinical Development

Before a candidate drug can progress to human trials, it must undergo rigorous experimental validation and preclinical assessment to establish both efficacy and safety [10].

Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Studies evaluate how the body processes the drug candidate and its potential adverse effects [10]. Key aspects include:

- ADME Profiling: Assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion characteristics using a combination of in vitro, in vivo, and in silico methods [10] [9] [1].

- Toxicity Studies: Investigation of potential adverse effects through in vitro assays and animal studies [10].

Modern approaches increasingly employ physiologically relevant models such as high-content screening, phenotypic assays, and organoid or 3D culture systems to enhance translational relevance and better predict clinical success [1]. Techniques like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) have emerged as leading approaches for validating direct target engagement in intact cells and tissues, helping to close the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [13].

Preclinical Trials are conducted in controlled laboratory settings using in vitro methods (test tubes, cell cultures) and in vivo models (laboratory animals) [10]. These studies focus on two major aspects:

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): Studies the biological effects the drug has on the body [10].

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): Examines how the body processes the drug, covering absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [10].

The data collected throughout these validation stages helps optimize final drug formulation, dosage, and administration route before progressing to clinical trials [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of rational drug design requires a comprehensive suite of specialized reagents, tools, and platforms. The following table details key resources essential for conducting RDD research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Rational Drug Design

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Tools | X-ray crystallography platforms, Cryo-EM, NMR spectroscopy | Determine 3D atomic structures of target proteins and protein-ligand complexes | Structure-based drug design, binding site identification, binding mode analysis |

| Virtual Screening Resources | Compound libraries (ZINC, ChEMBL), Commercial "make-on-demand" libraries (Enamine, OTAVA) | Provide vast chemical space for computational screening | Hit identification, lead discovery through virtual screening |

| Computational Software | Molecular docking programs (AutoDock, GOLD); MD software (AMBER, GROMACS); QSAR tools | Predict ligand-receptor interactions, binding affinity, and dynamic behavior | Structure-based design, binding mode prediction, ADMET property estimation |

| Target Engagement Assays | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) | Confirm direct binding of compounds to targets in physiologically relevant environments | Validation of target engagement, mechanism of action studies |

| Bioinformatics Databases | Genomic databases (GenBank), protein databases (PDB), gene expression databases | Provide essential biological data for target identification and validation | Target selection, pathway analysis, understanding disease biology |

| ADMET Screening Tools | Caco-2 cell models, liver microsomes, cytochrome P450 assays, hERG channel assays | Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties | Lead optimization, safety profiling, candidate selection |

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of rational drug design continues to evolve rapidly, with several transformative trends shaping its future direction:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning have evolved from disruptive concepts to foundational capabilities in modern drug R&D [13]. Machine learning models now routinely inform target prediction, compound prioritization, pharmacokinetic property estimation, and virtual screening strategies [13]. The emerging concept of the "informacophore" represents a paradigm shift, combining minimal chemical structures with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations to identify features essential for biological activity [1]. This approach reduces biased intuitive decisions and may accelerate discovery processes [1].

In Silico Screening has become a frontline tool in modern drug discovery [13]. Computational approaches like molecular docking, QSAR modeling, and ADMET prediction are now indispensable for triaging large compound libraries early in the pipeline, enabling prioritization of candidates based on predicted efficacy and developability [13]. These tools have become central to rational screening and decision support [13].

Hit-to-Lead Acceleration through AI and miniaturized chemistry is rapidly compressing traditional discovery timelines [13]. The integration of AI-guided retrosynthesis, scaffold enumeration, and high-throughput experimentation (HTE) enables rapid design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles, reducing discovery timelines from months to weeks [13]. For example, deep graph networks were recently used to generate over 26,000 virtual analogs, resulting in sub-nanomolar inhibitors with a 4,500-fold potency improvement over initial hits [13].

Functional Target Engagement methodologies are addressing the critical need for physiologically relevant confirmation of drug-target interactions [13]. As molecular modalities diversify to include protein degraders, RNA-targeting agents, and covalent inhibitors, technologies like CETSA provide quantitative, system-level validation of direct binding in intact cells and tissues [13].

Integrated Cross-Disciplinary Pipelines are becoming standard in leading drug discovery organizations [13]. The convergence of expertise from computational chemistry, structural biology, pharmacology, and data science enables the development of predictive frameworks that combine molecular modeling, mechanistic assays, and translational insight [13]. This integration supports earlier, more confident decision-making and reduces late-stage surprises [13].

As these trends continue to mature, rational drug design is poised to become increasingly precise, efficient, and successful in delivering novel therapeutics to address unmet medical needs across a broad spectrum of diseases.

Diagram 2: Overview of the Rational Drug Design Pipeline from target identification to clinical trials, highlighting the sequential stages of the drug discovery and development process.

Contrasting Rational Design with Phenotypic Screening (Forward vs. Reverse Pharmacology)

The process of drug discovery has historically been dominated by two contrasting philosophical approaches: rational drug design and phenotypic screening. These methodologies represent fundamentally different paths to identifying and optimizing therapeutic compounds. Rational drug design, also known as reverse pharmacology or target-based drug discovery, begins with a hypothesis about a specific molecular target's role in disease [16] [17]. This approach leverages detailed knowledge of biological structures and mechanisms to deliberately design compounds that interact with predefined targets. In contrast, phenotypic screening, often termed forward pharmacology, employs a more empirical approach by observing compound effects on whole cells, tissues, or organisms without requiring prior understanding of specific molecular targets [18] [19]. The strategic choice between these paradigms has profound implications for research direction, resource allocation, and the nature of resulting therapeutics, forming a core consideration in pharmaceutical research and development.

The resurgence of phenotypic screening over the past decade, after being largely supplanted by target-based methods during the molecular biology revolution, highlights how these approaches exist in a dynamic balance [18]. Modern drug discovery recognizes that both strategies have distinct strengths and applications, with the most effective research portfolios often incorporating elements of both. This technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and applications of both rational design and phenotypic screening, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and implementing these approaches within contemporary drug discovery programs.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Rational Drug Design (Reverse Pharmacology)

Rational drug design constitutes a target-centric approach where drug discovery begins with the identification and validation of a specific biological macromolecule (typically a protein) understood to play a critical role in a disease pathway [5]. The fundamental premise is that modulation of this target's activity will yield therapeutic benefits. This approach requires detailed structural knowledge of the target, often obtained through X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [20] [5]. The design process exploits the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in the target's binding site to conceive molecules that fit complementarily, similar to a key fitting into a lock, though modern interpretations account for mutual adaptability as described by the induced-fit theory [5].

Rational drug design encompasses two primary methodologies: receptor-based design (direct design) when the target structure is known, and pharmacophore-based design (indirect design) when structural information is limited to known active compounds [5]. The power of this approach lies in its systematic nature, allowing researchers to optimize compounds for specific parameters including binding affinity, selectivity, and drug-like properties through iterative design cycles. Rational design has been particularly successful for target classes with well-characterized binding sites and established structure-activity relationships, such as protein kinases and G-protein coupled receptors [20].

Phenotypic Screening (Forward Pharmacology)

Phenotypic screening represents a biology-first approach where compounds are evaluated based on their effects on disease-relevant phenotypes without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [18] [19]. This strategy acknowledges the incompletely understood complexity of biological systems and disease pathologies, allowing for the discovery of therapeutic effects that might be missed by more reductionist approaches. The philosophical foundation of phenotypic screening is that observing compound effects in realistic disease models can identify beneficial bioactivity regardless of the specific mechanism involved, with target identification (deconvolution) typically following initial compound discovery [19].

Modern phenotypic screening has evolved significantly from earlier observational approaches, now incorporating sophisticated cell-based models, high-content imaging, and transcriptomic profiling to quantify complex phenotypic changes [18] [19]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing biological processes that involve multiple pathways or complex cellular interactions, where modulating a single target may be insufficient for therapeutic effect. Phenotypic screening has proven especially productive for identifying first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action, expanding the druggable target space beyond what would be predicted from current biological understanding [18].

Historical Context and Evolution

The historical development of these approaches reveals a pendulum swing in pharmaceutical preferences. Traditional medicine and early drug discovery were inherently phenotypic, with remedies developed through observation of their effects on disease states [18] [21]. The isolation of morphine from opium in 1817 by Friedrich Sertürner marked the beginning of systematic compound isolation from natural sources, but still within a phenotypic framework [21]. The molecular biology revolution of the 1980s and the sequencing of the human genome in 2001 catalyzed a major shift toward target-based approaches, promising more efficient and predictable drug discovery [18].

A seminal analysis published in 2011 demonstrated that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class drugs were discovered through phenotypic approaches rather than target-based methods [18] [19]. This surprising observation, coupled with declining productivity in pharmaceutical research, spurred a resurgence of interest in phenotypic screening, now augmented with modern tools and strategies [18]. Contemporary drug discovery recognizes both approaches as valuable, with the strategic choice depending on disease understanding, available tools, and program objectives.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Rational Design and Phenotypic Screening

| Feature | Rational Drug Design | Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Defined molecular target | Disease-relevant phenotype |

| Knowledge Requirement | Target structure and function | Disease biology |

| Primary Screening Output | Target binding or inhibition | Phenotypic modification |

| Target Identification Timing | Before compound discovery | After compound discovery |

| Throughput Potential | High (with automated assays) | Variable (often medium) |

| Chemical Space Exploration | Focused on target-compatible compounds | Unrestricted |

| Success Rate for First-in-Class | Lower | Higher historically |

| Major Challenge | Target validation | Target deconvolution |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Rational Drug Design Methodologies

Structure-Based Drug Design

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) relies on three-dimensional structural information about the biological target, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [20] [5]. The process begins with target selection and validation, establishing that modulation of the target will produce therapeutic effects. Once a structure is available, researchers identify potential binding sites and characterize their chemical and steric properties.

The core SBDD workflow involves:

- Binding site characterization - Identifying pockets and clefts on the target surface capable of binding small molecules

- Molecular docking - Computational screening of compound libraries to predict binding poses and affinities

- De novo ligand design - Creating novel molecular structures complementary to the binding site

- Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis - Iterative compound optimization based on structural data

Advanced SBDD incorporates molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility and solvation effects, providing more accurate predictions of binding thermodynamics [20] [2]. Fragment-based drug design (FBDD) represents a specialized SBDD approach that screens low molecular weight fragments (<250 Da) then elaborates or links them into higher-affinity compounds, reversing the traditional probability paradigm of high-throughput screening [20].

Ligand-Based Drug Design

When three-dimensional target structure is unavailable, ligand-based methods provide an alternative rational approach. These techniques utilize known active compounds to infer pharmacophore models - abstract representations of steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition [5]. The key methodologies include:

- Pharmacophore modeling - Identifying essential structural features and their spatial relationships

- Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) analysis - Establishing mathematical relationships between chemical descriptors and biological activity

- Molecular similarity analysis - Identifying novel compounds with structural similarity to known actives

- Scaffold hopping - Discovering novel chemotypes that maintain critical interaction capabilities

These approaches rely on the principle of molecular mimicry, where chemically distinct compounds produce similar biological effects through interaction with the same target [5]. Successful examples include ATP competitive kinase inhibitors that replicate hydrogen-bonding interactions of the natural substrate while improving drug-like properties.

Phenotypic Screening Methodologies

Cell-Based Phenotypic Assays

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated cell-based models that recapitulate key aspects of disease biology. The development of these assays begins with careful model selection to ensure biological relevance and translational potential [19]. Key considerations include:

- Disease relevance - The model should capture critical aspects of the human disease pathology

- Assay robustness - Sufficient reproducibility for screening applications

- Scalability - Compatibility with medium- to high-throughput formats

- Readout relevance - Measured parameters should connect to clinical endpoints

Advanced phenotypic models include patient-derived cells, co-culture systems, 3D organoids, and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cell types [19]. These systems better capture the cellular context and disease complexity than traditional immortalized cell lines. Readouts extend beyond simple viability to include high-content imaging of morphological changes, transcriptomic profiling, and functional measures such as contractility or electrical activity.

Phenotypic Screening Workflow

A comprehensive phenotypic screening campaign follows a structured workflow:

- Model development and validation - Establishing biologically relevant screening systems

- Primary screening - Testing compound libraries for phenotypic effects

- Hit validation - Confirming activity in secondary assays and counter-screens

- Lead optimization - Improving compound properties through medicinal chemistry

- Target deconvolution - Identifying mechanism of action and molecular targets

- Preclinical development - Advancing optimized leads toward clinical trials

The "rule of 3" for phenotypic screening suggests using at least three different assay systems with orthogonal readouts to triage hits and minimize artifacts [19]. This multi-faceted approach increases confidence that observed activities represent genuine therapeutic potential rather than assay-specific artifacts.

Target Deconvolution in Phenotypic Screening

Target deconvolution - identifying the molecular mechanism of action for phenotypically active compounds - represents one of the most significant challenges in phenotypic screening [18] [19]. Several experimental approaches have been developed for this purpose:

- Affinity purification - Using modified compound versions to capture interacting proteins

- Genetic approaches - CRISPR-based screens to identify genes that modify compound sensitivity

- Proteomic profiling - Assessing global protein expression or phosphorylation changes

- Transcriptomic profiling - Comparing gene expression signatures to reference databases

- Resistance generation - Selecting and characterizing resistant clones to identify targets

Each method has strengths and limitations, making a combination of approaches most effective for confident target identification. For some therapeutic applications, particularly when diseases are poorly understood, detailed mechanism of action may not be essential for initial development, allowing progression with partial mechanistic understanding [17].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Rational Design and Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Target Proteins | Recombinant purified proteins, membrane preparations | Enable binding assays and structural studies in rational design |

| Cell-Based Models | Immortalized cell lines, primary cells, iPSC-derived cells, co-culture systems | Provide biologically relevant screening platforms for phenotypic approaches |

| Compound Libraries | Diverse small molecules, targeted libraries, fragment collections, natural product extracts | Source of chemical starting points for both approaches |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorescent probes, antibodies, labeled substrates, biosensors | Enable quantification of binding, activity, or phenotypic changes |

| Genomic Tools | CRISPR libraries, RNAi collections, cDNA expression clones | Facilitate target validation and deconvolution |

| Animal Models | Genetically engineered mice, patient-derived xenografts, disease models | Provide in vivo validation of compound activity and mechanism |

Applications, Case Studies, and Clinical Impact

Success Stories from Rational Drug Design

Rational design approaches have produced numerous clinically important drugs, particularly for well-characterized target classes. Protein kinase inhibitors represent a standout success, with imatinib (Gleevec) for chronic myeloid leukemia serving as a paradigmatic example [20] [17]. Imatinib was designed to target the BCR-ABL fusion protein resulting from the Philadelphia chromosome, with co-crystal structures guiding optimization of binding affinity and selectivity [17]. Although initially regarded as selective for BCR-ABL, subsequent profiling revealed activity against other kinases including c-KIT and PDGFR, contributing to its efficacy in additional indications [18].

HIV antiretroviral therapies provide another compelling case for target-based approaches [17]. Early identification of key viral enzymes including reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease enabled development of targeted inhibitors that form the backbone of combination antiretroviral therapy. The precision of this approach transformed HIV from a fatal diagnosis to a manageable chronic condition, demonstrating the power of targeting well-validated molecular mechanisms [17].

Structure-based design has been particularly impactful for optimizing drug properties beyond simple potency. Examples include enhancing selectivity to reduce off-target effects, improving metabolic stability to extend half-life, and reducing potential for drug-drug interactions. These applications highlight how rational approaches excel at refining compound profiles once initial activity has been established.

Success Stories from Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening has demonstrated remarkable productivity for discovering first-in-class medicines, with analyses showing it has been the source of more first-in-class small molecules than target-based approaches [18] [19]. Notable examples include:

- Ivacaftor and correctors for cystic fibrosis - Discovered through screening for compounds that improve CFTR channel function in patient-derived cells, these agents work through novel mechanisms that would have been difficult to predict from target-based approaches [18].

- Risdiplam and branaplam for spinal muscular atrophy - Identified through phenotypic screens for compounds that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing, representing an unprecedented mechanism targeting the U1 snRNP complex [18].

- Artemisinin for malaria - Derived from traditional medicine and validated through phenotypic screening against Plasmodium parasites, demonstrating the value of phenotype-first approaches when molecular targets are poorly understood [21] [17].

- Lenalidomide and related immunomodulatory drugs - Although clinical effects were observed before mechanism understanding, these agents were later found to function through novel mechanisms involving Cereblon and targeted protein degradation [18].

These successes highlight how phenotypic approaches can expand the "druggable target space" to include unexpected cellular processes and novel mechanisms of action [18]. They demonstrate particular value when no attractive target is known or when project goals include discovering first-in-class medicines with differentiated mechanisms.

Strategic Integration in Drug Discovery Portfolios

The most productive drug discovery organizations strategically deploy both rational and phenotypic approaches based on project requirements and stage of development [19] [5]. Key considerations for approach selection include:

- Level of biological understanding - Well-understood pathways favor rational design; complex or poorly understood biology favors phenotypic screening

- Project goals - First-in-class discovery often benefits from phenotypic approaches; best-in-class optimization typically employs rational design

- Available tools and expertise - Model systems for phenotypic screening and structural tools for rational design

- Therapeutic area conventions - Established target classes versus novel biological space

- Resource constraints - Phenotypic screening often requires more specialized models; rational design demands structural biology capabilities

The concept of a "chain of translatability" emphasizes using disease-relevant models throughout discovery to enhance clinical success rates [19]. This framework encourages selection of approaches and models based on their ability to predict human therapeutic effects rather than purely technical considerations.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Persistent Challenges in Rational Drug Design

Despite significant advances, rational drug design faces several persistent challenges. The accuracy of binding affinity predictions remains limited by difficulties in modeling solvation effects, entropy contributions, and protein flexibility [20] [2]. While structure-based methods can often predict binding modes correctly, reliable free energy calculations remain elusive, necessitating experimental confirmation of theoretical predictions.

Target validation represents another major challenge, as compounds designed against hypothesized targets may fail in clinical development if biological understanding is incomplete [17]. This has been particularly problematic in complex diseases like Alzheimer's, where numerous target-based approaches have failed despite strong scientific rationale [17]. The reductionist nature of target-based approaches may overlook compensatory mechanisms or systems-level properties that limit efficacy in intact organisms.

Additionally, rational design approaches can be constrained by limited chemical space exploration, as design efforts often focus on regions of chemical space perceived as compatible with the target binding site. This can potentially miss novel chemotypes or mechanisms that would not be predicted from current understanding.

Persistent Challenges in Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening faces its own distinct set of challenges, with target deconvolution remaining particularly difficult [18] [19]. Even with modern tools like CRISPR screening and chemical proteomics, identifying the precise molecular targets responsible for phenotypic effects can be time-consuming and sometimes inconclusive. For some compounds with complex polypharmacology, the therapeutic effect may emerge from combined actions on multiple targets rather than a single entity [18].

Assay development for phenotypic screening requires careful balance between physiological relevance and practical screening considerations. Overly complex models may better capture disease biology but prove difficult to implement robustly, while simplified systems may miss critical aspects of pathology [19]. The validation of phenotypic models requires significant investment before screening can begin.

Additionally, hit optimization from phenotypic screens can be challenging without understanding the molecular target, as traditional structure-activity relationships may not apply when the mechanism is unknown. This can lead to empirical optimization cycles that prolong discovery timelines.

Technological Advances and Future Outlook

Both rational and phenotypic approaches are being transformed by new technologies that enhance their capabilities and address existing limitations. In rational design, artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing target identification, compound design, and property prediction [2]. These methods can integrate diverse data types to generate novel hypotheses and accelerate optimization cycles. Advances in structural biology, particularly cryo-electron microscopy, are providing high-resolution structures for previously intractable targets like membrane proteins and large complexes [20].

For phenotypic screening, innovations in stem cell biology, organ-on-a-chip technology, and high-content imaging are creating more physiologically relevant and information-rich screening platforms [19]. These systems better capture human disease biology, potentially improving translational success. Functional genomics tools like CRISPR screening enable systematic exploration of gene function alongside compound screening, potentially streamlining target deconvolution [18].

The future of drug discovery likely involves increased integration of approaches rather than exclusive commitment to one paradigm [5]. Strategies that combine phenotypic discovery with subsequent mechanistic elucidation, or that use structural information to guide optimization of phenotypically discovered hits, leverage the complementary strengths of both philosophies. As these methodologies continue to evolve and converge, they promise to enhance the efficiency and productivity of drug discovery, delivering innovative medicines for patients with diverse conditions.

Key Historical Milestones and Success Stories in Rational Drug Design

Rational Drug Design (RDD) represents a fundamental shift in pharmaceutical science from traditional empirical methods to a targeted approach based on understanding molecular interactions and disease mechanisms. Unlike earlier trial-and-error approaches, RDD utilizes detailed knowledge of biological targets and their three-dimensional structures to consciously engineer therapeutic compounds [22] [23]. This methodology has become the most advanced approach for drug discovery, employing a sophisticated arsenal of computational and experimental techniques to achieve its main goal: discovering effective, specific, non-toxic, and safe drugs [22]. The progression of RDD has been marked by significant theoretical advances and technological innovations that have systematically transformed how researchers identify and optimize lead compounds.

The foundation of rational drug design rests on the principle of molecular recognition—the precise interaction between a drug molecule and its biological target [5]. Early conceptual models have evolved from Emil Fischer's 1890 "lock-and-key" hypothesis, which viewed drug-receptor interactions as rigid complementarity, to Daniel Koshland's 1958 "induced-fit" theory, which recognized that both ligand and target undergo mutual conformational adaptations to achieve optimal binding [22] [5]. These fundamental principles underpin all modern rational drug design strategies and continue to guide the development of therapeutic interventions with increasing sophistication.

Historical Evolution of Rational Drug Design

The development of rational drug design has followed a trajectory marked by paradigm-shifting discoveries and methodological innovations. The table below chronicles the key historical milestones that have defined this evolving field.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Rational Drug Design

| Time Period | Key Development | Theoretical/Methodological Advancement | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 19th Century | Lock-and-Key Model (Emil Fischer) | Conceptualization of specific drug-receptor complementarity | Established foundation for understanding molecular recognition |

| 1950s | Induced-Fit Theory (Daniel Koshland) | Recognition of conformational flexibility in drug-receptor interactions | Provided more accurate model of binding dynamics |

| 1960s-1970s | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) | Systematic correlation of physicochemical properties with biological activity [24] | Introduced quantitative approaches to lead optimization |

| 1972 | Topliss Decision Tree | Non-mathematical scheme for aromatic substituent selection [24] | Streamlined analog synthesis through stepwise decision framework |

| 1970s-1980s | Structure-Based Drug Design | Direct utilization of 3D protein structures for ligand design [5] | Enabled targeted design complementary to binding sites |