Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Workflow Guide from Concept to Clinical Candidates

This comprehensive review explores pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) as a powerful computational strategy in modern drug discovery.

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Workflow Guide from Concept to Clinical Candidates

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) as a powerful computational strategy in modern drug discovery. Covering both foundational concepts and cutting-edge methodologies, we examine the complete PBVS workflow from initial model generation to experimental validation. The article details structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore approaches, virtual screening implementation, machine learning integration for optimization, and comparative performance against docking-based methods. Through case studies targeting SARS-CoV-2, EGFR, MAO, and FGFR1, we demonstrate how PBVS successfully identifies novel bioactive compounds while addressing challenges like scoring function limitations and conformational sampling. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical insights for implementing PBVS in their discovery pipelines to accelerate lead identification and optimization.

Pharmacophore Fundamentals: From Historical Concepts to Modern Implementation

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, the pharmacophore is a foundational concept that provides an abstract representation of the molecular interactions essential for biological activity. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [2] [3]. This model explains how structurally diverse ligands can bind to a common receptor site by focusing on shared chemical functionalities rather than specific molecular scaffolds [2]. Pharmacophore models have become indispensable tools in virtual screening, de novo design, and lead optimization, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [4] [3].

Core Principles and Feature Definitions

IUPAC Principles

The IUPAC definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a specific molecular structure, but rather a three-dimensional pattern of steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition [1]. This conceptual framework distinguishes pharmacophores from "privileged structures," which are specific molecular frameworks known to provide useful ligands for multiple targets [1]. The pharmacophore concept allows medicinal chemists to transcend specific chemical structures and focus on the essential interaction capabilities necessary for biological activity [1].

Essential Pharmacophore Features

Pharmacophore features represent abstracted chemical functionalities that mediate ligand-receptor interactions. The table below summarizes the core feature types and their characteristics:

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Common Molecular Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | A | An electron-rich atom that can accept a hydrogen bond | Carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, nitrogen in aromatic rings |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | D | A hydrogen atom covalently bound to an electronegative atom, available for donation | Hydroxyl group (-OH), primary and secondary amines (-NH-, -NH₂) |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | P | A group that can carry a positive charge under physiological conditions | Primary, secondary, or tertiary amines |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | N | A group that can carry a negative charge under physiological conditions | Carboxylic acid, phosphate, tetrazole group |

| Hydrophobic (H) | H | A non-polar region that favors hydrophobic interactions | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings, alicyclic systems |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | R | A planar, conjugated ring system that can participate in π-π interactions | Phenyl, pyridine, pyrrole, other heteroaromatic rings |

These features are typically represented in 3D pharmacophore models as geometric objects such as points, vectors, or spheres with tolerance radii [4]. The spatial relationship between these features—defined by distances and angles—is as critical as the features themselves for defining pharmacophore specificity [1].

Pharmacophore Modeling Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [4] [3].

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, correct bond orders, and optimize the structure using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., CHARMM) [5].

- Binding Site Detection: Identify the ligand-binding site using computational tools like GRID or LUDI, which analyze the protein surface for potential interaction sites based on geometric and energetic properties [4].

- Interaction Map Generation: Analyze the binding site to identify potential interaction points complementary to ligand features. This can be done from a protein-ligand complex or the apo structure [4].

- Feature Selection and Model Building: Select the most relevant interaction points essential for bioactivity. The resulting model consists of these selected features and may include exclusion volumes to represent forbidden regions of the binding pocket [4].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based approaches can be employed using a set of known active compounds [4] [2].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

- Training Set Selection: Compile a structurally diverse set of molecules with known biological activities, including both active and inactive compounds if possible [2].

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule in the training set, generate a set of low-energy conformations likely to contain the bioactive conformation [2].

- Molecular Superimposition: Systematically superimpose the low-energy conformations of all training molecules. Identify the set of conformations (one from each active molecule) that provides the best spatial overlap of common functional groups [2].

- Feature Abstraction: Transform the superimposed functional groups into an abstract pharmacophore representation (e.g., aromatic rings become 'aromatic ring' features) [2].

- Model Validation: Validate the model by testing its ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds not included in the training set [2].

Advanced Protocols and Applications

Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening (FragmentScout)

The FragmentScout workflow represents a recent advancement that leverages X-ray crystallographic fragment screening data to enhance pharmacophore modeling [6].

Protocol 3: FragmentScout Workflow for SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 Helicase

- Data Collection: Download multiple XChem fragment screening crystallographic coordinate files from the RCSB PDB (e.g., PDB codes: 5RL6, 5RL7, 5RL8, etc.) [6].

- Structural Alignment: Import the 3D structurally pre-aligned Protein Data Bank (PDB) files into pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., LigandScout) [6].

- Feature Detection and Aggregation: For each fragment structure, automatically detect pharmacophore features and add exclusion volumes. Store each generated pharmacophore query [6].

- Query Merging: Within the alignment perspective, select all queries, align them, and merge them using the "based-on reference points" option. Interpolate all features within a distance tolerance to create a joint pharmacophore query for the binding site [6].

- Virtual Screening: Use the joint pharmacophore query to search large 3D conformational databases (e.g., Enamine REAL) using specialized software (e.g., LigandScout XT) [6].

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR)

QPhAR represents an innovative approach that extends pharmacophore concepts into quantitative modeling, integrating machine learning with traditional pharmacophore methods [7] [8].

Protocol 4: QPhAR Modeling Workflow

- Dataset Preparation: Clean and prepare a dataset of 15-50 ligands with known activity values (e.g., IC₅₀ or Kᵢ). Split the data into training and test sets [7].

- Consensus Pharmacophore Generation: Identify a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples [8].

- Feature Alignment: Align input pharmacophores (or pharmacophores generated from input molecules) to the merged-pharmacophore [8].

- Model Training: Extract information regarding each aligned pharmacophore's position relative to the merged-pharmacophore. Use this information as input to a machine learning algorithm to derive a quantitative relationship between the pharmacophore features and biological activities [8].

- Virtual Screening and Hit Ranking: Use the validated QPhAR model to screen compound databases and rank the obtained hits by their predicted activity values [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of QPhAR Models on Various Targets

| Data Source | Baseline FComposite-Score | QPhAR FComposite-Score | QPhAR R² | QPhAR RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ece et al. | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.41 |

| Garg et al. (hERG) | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| Ma et al. | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| Wang et al. | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.46 |

| Krovat et al. | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.70 |

Case Study: Identification of VEGFR-2/c-Met Dual Inhibitors

A recent study demonstrated the application of pharmacophore modeling in discovering dual-target inhibitors for cancer therapy [5].

Protocol 5: Virtual Screening for Dual-Target Inhibitors

- Target Preparation: Select 10 VEGFR-2 and 8 c-Met co-crystal structures from the PDB based on resolution (<2Å), biological activity (nM level), and structural diversity. Prepare proteins by removing water molecules, completing missing residues, and energy minimization using CHARMM force field in Discovery Studio [5].

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Use the "Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation" protocol in Discovery Studio with maximum features set to 10. Consider six standard pharmacophore features: HBA, HBD, positive/negative ionizable, hydrophobic, and ring aromatic centers [5].

- Model Validation: Validate models using decoy sets with known active and inactive compounds. Calculate Enrichment Factor (EF) and Area Under Curve (AUC) values. Select models with AUC >0.7 and EF >2 for virtual screening [5].

- Compound Library Filtering: Screen >1.28 million compounds from ChemDiv database using Lipinski and Veber rules, followed by ADMET predictions for aqueous solubility, BBB penetration, CYP450 inhibition, and hepatotoxicity [5].

- Virtual Screening and Hit Identification: Screen the filtered compound library against the selected pharmacophore models. Perform molecular docking studies on the resulting hits. Conduct molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) and MM/PBSA calculations to assess binding stability and free energies [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Structure & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening | Feature detection, model building, database screening [6] |

| Discovery Studio | Software Suite | Comprehensive modeling and simulation platform | Pharmacophore generation, docking, ADMET prediction [5] |

| FragmentScout | Workflow | Fragment-based pharmacophore screening | Aggregating features from XChem fragment data [6] |

| QPhAR | Algorithm | Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship | Building predictive models from pharmacophore features [7] [8] |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank | Database | Repository of 3D protein structures | Source of target structures for structure-based modeling [4] [5] |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactivity data for drug-like molecules | Source of training compounds for ligand-based modeling [8] |

| Enamine REAL | Compound Database | Ultra-large collection of synthesizable compounds | Virtual screening library for hit identification [6] |

| DUD-E | Database | Directory of useful decoys for benchmarking | Validation of pharmacophore model enrichment [5] |

The conceptual foundation of modern computer-aided drug design (CADD) was established over a century ago by Paul Ehrlich, who introduced the revolutionary concept of the "magic bullet" (Zauberkugeln) [9] [4] [10]. Ehrlich postulated the existence of compounds that could selectively target disease-causing organisms without harming the host, a principle that has inspired generations of scientists [9]. This seminal idea, for which Ehrlich received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908, proposed that therapeutic agents could be designed to possess inherent selective affinity for specific biological targets [9] [4]. Ehrlich's work on Salvarsan for syphilis treatment provided an early validation of this principle, demonstrating that chemical compounds could be synthesized to selectively combat pathogens [4].

Over the past century, Ehrlich's magic bullet concept has evolved into the fundamental paradigm of modern targeted therapy, finding its ultimate expression in pharmacophore-based virtual screening within CADD [9]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) now defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4] [10]. This definition represents the contemporary realization of Ehrlich's original vision, translating his abstract concept into a precise, computable model that drives rational drug discovery.

Theoretical Foundations: From Concept to Computable Model

The Evolution of Pharmacophore Theory

The transition from Ehrlich's conceptual framework to operational computational models required several theoretical advances. The initial "lock and key" concept proposed by Emil Fisher in 1894 provided the crucial foundation for understanding specific molecular recognition between ligands and their receptors [4]. Schueler later expanded this concept to form the basis of our modern pharmacophore understanding, which abstracts specific atoms and functional groups into generalized stereoelectronic features [4] [10].

Contemporary pharmacophore modeling represents these interactions through key feature types that facilitate binding with biological targets. The most significant features include: hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic rings (AR), and metal coordinating areas [4] [10]. These abstract representations enable the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share essential interaction capabilities, a capability fundamental to scaffold hopping and lead optimization in drug discovery [4].

Computational Implementation Frameworks

The translation of pharmacophore theory into practical computational tools has enabled the precise implementation of Ehrlich's vision. Modern pharmacophore modeling employs two complementary approaches, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This approach derives pharmacophore features directly from the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [4] [10]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, interactions can be extracted directly from the bioactive conformation. In the absence of ligand information, binding site analysis using tools like GRID or LUDI can identify potential interaction points [4]. Structure-based models benefit from the incorporation of exclusion volumes (XVOL) that represent steric restrictions of the binding pocket, significantly enhancing model selectivity [4] [10].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: When three-dimensional protein structures are unavailable, this approach constructs pharmacophore hypotheses by identifying common chemical features shared by multiple known active ligands [4] [10]. The underlying assumption is that compounds exhibiting similar biological activity share a common pharmacophore responsible for their interaction with the target. This method requires careful training set selection with structurally diverse molecules exhibiting high binding affinity, and typically employs algorithms to generate multiple conformations and identify optimal feature alignments [10].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Parameter | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Required Input Data | 3D protein structure (with or without bound ligand) | Multiple active ligands with known biological activities |

| Key Advantages | Does not require known active ligands; Incorporates target constraints directly | Does not require protein structural information; Captures ligand flexibility |

| Common Software Tools | Discovery Studio, LigandScout, Schrödinger Phase | PharmaGist, ZINCPharmer, MOE |

| Feature Selection Basis | Protein-ligand interaction analysis or binding site topology | Common chemical features across active ligand set |

| Exclusion Volumes | Directly derived from binding site geometry | Not typically used or empirically estimated |

| Optimal Application Scenario | Targets with available high-quality structures; Novel target classes with few known actives | Established targets with multiple known active chemotypes; Scaffold hopping |

Modern Computational Workflow: Implementing Ehrlich's Vision

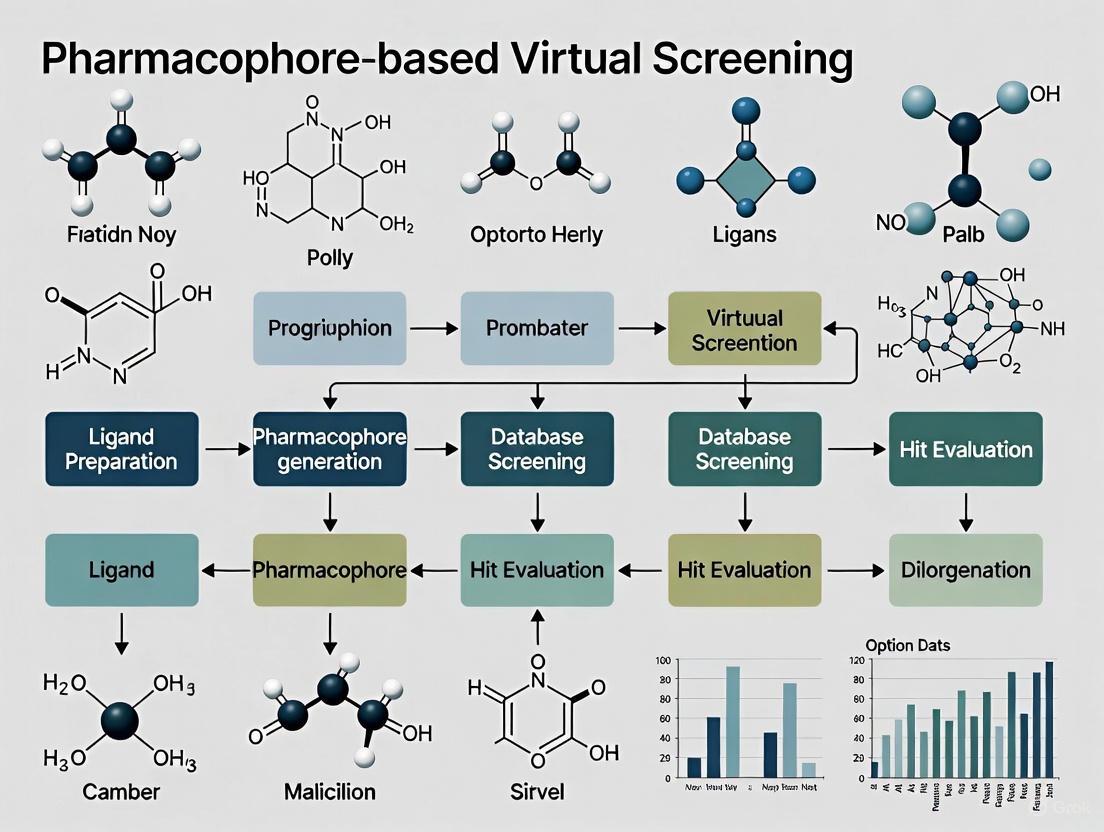

The contemporary realization of Ehrlich's magic bullet concept operates through a sophisticated computational workflow that integrates multiple methodologies to identify and optimize potential therapeutic agents. The following diagram illustrates the complete pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflow:

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Objective: To generate a pharmacophore model using the three-dimensional structure of a target protein.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure (e.g., PDB ID: 6JXT for EGFR) [11]

- Schrödinger Maestro or Discovery Studio Visualizer software [12] [11]

- LigandScout (v4.4 or higher) for advanced pharmacophore feature identification [11]

Methodology:

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the target protein structure from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) [4]

- Preprocess the structure using protein preparation tools to correct bond orders, add hydrogen atoms, create disulfide bonds, and fill missing side chains or loops [12]

- Delete water molecules beyond 5Å from the binding site unless functionally important [12]

- Optimize hydrogen bonding networks and refine the structure using restrained minimization with an OPLS4 force field until reaching an RMSD convergence of 0.30 Å [12]

Binding Site Characterization:

- Identify the ligand-binding site using either:

- Experimental data: Coordinates from co-crystallized ligands

- Computational prediction: Tools like GRID or SiteMap for binding site detection [4]

- Define key interacting residues through analysis of conserved structural motifs or known mutation sites affecting activity [11]

- Identify the ligand-binding site using either:

Pharmacophore Feature Extraction:

- For structures with bound ligands: Extract interaction features directly from the protein-ligand complex, identifying hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged/aromatic features [11] [10]

- For apo-structures: Generate all possible interaction points within the binding cavity and select the most conserved or energetically favorable features [4]

- Add exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket [4] [10]

- Manually refine the model by removing redundant features and optimizing spatial tolerances [10]

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Objective: To develop a pharmacophore model using a set of known active ligands when the protein structure is unavailable.

Materials and Software:

- Known active ligands (15-50 compounds with measured activity values, preferably IC₅₀ or Kᵢ) [7]

- PharmaGist webserver or ZINCPharmer for ligand alignment and feature identification [13]

- HyperChem (v8.0.8) or similar for molecular optimization using semi-empirical methods (e.g., RM1) [13]

Methodology:

Ligand Set Preparation:

- Collect structurally diverse active compounds with validated biological activity from databases like ChEMBL, DrugBank, or OpenPHACTS [10]

- Obtain 2D structures from PubChem and convert to 3D conformations [13]

- Optimize molecular geometry using semi-empirical methods and correct partial charges [13]

- Normalize activity data (e.g., convert IC₅₀ to pIC₅₀) to ensure consistent weighting [12]

Common Pharmacophore Identification:

- Input the prepared ligand set into alignment software (e.g., PharmaGist) with feature weighting parameters: aromatic ring = 3.0; hydrophobic = 3.0; hydrogen bond donor/acceptor = 1.5; charge = 1.0 [13]

- Generate multiple alignment hypotheses and select the model with the highest alignment score and best coverage of active compounds [13]

- Define optional features and allowed omitted features based on SAR analysis [10]

Model Refinement and Validation:

- Validate the model using a carefully curated test set containing both active and inactive molecules or decoys [10]

- Employ the Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E) to generate optimized decoys with similar 1D properties but different 2D topologies compared to active molecules [10]

- Assess model quality using enrichment metrics (EF), yield of actives, specificity, sensitivity, and ROC-AUC analysis [10]

Protocol 3: Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Objective: To identify novel hit compounds by screening large chemical libraries against validated pharmacophore models.

Materials and Software:

- Validated pharmacophore model (from Protocol 1 or 2)

- Compound databases: ZINC, Enamine, MMV Malaria Box, or corporate collections [12] [13]

- Screening tools: ZINCPharmer, MOE, or Schrödinger Phase [13] [14]

Methodology:

Database Preparation:

- Select appropriate compound libraries based on target class and drug-likeness criteria

- Prepare compounds using LigPrep or similar tools to generate 3D conformations, correct ionization states at physiological pH (7.4), and generate tautomers and stereoisomers [12]

- Apply property filters (e.g., molecular weight <400 g/mol, appropriate lipophilicity) to focus on drug-like chemical space [13]

Pharmacophore Screening:

Hit Prioritization and Validation:

- Subject virtual hits to molecular docking to verify binding modes and interaction consistency [12] [11]

- Analyze pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles using ADMET prediction tools [11] [13]

- Select 10-50 compounds for experimental testing based on diverse chemotypes, favorable properties, and commercial availability [10]

Case Studies and Applications

Successful Implementations in Drug Discovery

The practical implementation of pharmacophore-based virtual screening has yielded numerous success stories across various therapeutic areas, demonstrating the real-world impact of Ehrlich's conceptual framework:

Antimalarial Drug Discovery: A structure-based pharmacophore model targeting Plasmodium falciparum Hsp90 (PfHsp90) identified novel inhibitors with antiplasmodial activity. The model (DHHRR) comprised one hydrogen bond donor, two hydrophobic groups, and two aromatic rings. Virtual screening of commercial databases followed by induced fit docking identified 20 potential hits, eight of which displayed moderate to high activity against P. falciparum NF54 (IC₅₀ values: 0.14-6.0 μM) with selectivity indices >10 against human cells [12].

EGFR-Targeted Cancer Therapy: Research teams have employed structure-based pharmacophore modeling using the EGFR crystal structure (PDB ID: 6JXT) to identify novel antagonists capable of overcoming T790M resistance mutations. The virtual screening campaign identified four compounds (ZINC96937394, ZINC14611940, ZINC103239230, and ZINC96933670) with superior binding affinity (-9.9 to -9.2 kcal/mol) compared to gefitinib, lower toxicity profiles, and significant activity in cell-based assays [11].

MAO-B Inhibitors for Parkinson's Disease: A ligand-based pharmacophore model developed from alkaloids and flavonoids enabled the identification of novel MAO-B inhibitors. Virtual screening using ZINCPharmer identified palmatine and genistein as promising natural product-derived inhibitors with potential applications in Parkinson's disease treatment [13].

Table 2: Representative Virtual Screening Performance Metrics Across Studies

| Therapeutic Area | Target | Screening Database Size | Hit Rate | Most Potent Compound Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | PfHsp90 | 2.9 million compounds | 0.0007% (20 hits) | IC₅₀ = 0.14 μM |

| Oncology (EGFR) | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor | Not specified | Not reported | Binding affinity = -9.9 kcal/mol |

| Neurodegeneration | MAO-B | Natural product libraries | Not reported | Docking score superior to reference |

| General Benchmark | Various | Typical HTS: 100,000-1,000,000 | 0.021-0.55% | Varies by target |

| Pharmacophore VS | Various | Typical VS: 1,000,000+ | 5-40% | Typically low micromolar to nanomolar |

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Innovations

The field of pharmacophore-based screening continues to evolve with several significant methodological advances enhancing the implementation of Ehrlich's principles:

Machine Learning-Enhanced Workflows: The integration of QPhAR (Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship) models represents a significant advancement, combining pharmacophore screening with machine learning-based activity prediction. This approach automatically selects features driving pharmacophore model quality using SAR information, enabling fully automated generation of optimized pharmacophores from input datasets [7].

Hybrid Modeling Approaches: Contemporary research increasingly combines structure-based and ligand-based methods to leverage complementary information, enhancing model accuracy and hit rates [4] [10]. Additionally, the incorporation of molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility addresses the static limitations of crystal structure-based models [10].

Application in Selectivity Profiling: Beyond primary activity screening, pharmacophore models are increasingly employed for anti-target screening to identify and eliminate compounds with potential off-target activities, directly addressing the selectivity aspect of Ehrlich's magic bullet concept [10] [14].

Successful implementation of pharmacophore-based virtual screening requires access to specialized computational tools and databases. The following table outlines key resources essential for conducting cutting-edge research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Resources | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ [4] [11] |

| Compound Databases | ZINC, Enamine, PubChem, ChEMBL | Libraries of commercially available or biologically screened compounds | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ [12] [10] [13] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Schrödinger Suite, Discovery Studio, MOE, LigandScout | Comprehensive platforms for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Commercial licenses; Academic discounts available [12] [11] [14] |

| Web-Based Screening Tools | PharmaGist, ZINCPharmer | Server-based pharmacophore creation and screening capabilities | http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PharmaGist/; http://zincpharmer.csb.pitt.edu/ [13] |

| Validation Resources | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced) | Generation of optimized decoy sets for model validation | http://dude.docking.org/ [10] |

| Specialized Databases | MMV Malaria Box, DrugBank | Curated compound sets for specific disease areas or approved drugs | https://www.mmv.org/; https://go.drugbank.com/ [12] [10] |

The historical evolution from Paul Ehrlich's conceptual "magic bullet" to modern computer-aided drug design represents one of the most compelling narratives in pharmaceutical science. Ehrlich's visionary idea that compounds could be designed to selectively target disease mechanisms has found its ultimate expression in contemporary pharmacophore-based virtual screening methodologies. The abstract features comprising modern pharmacophore models directly mirror Ehrlich's conceptual framework of essential recognizing groups, now operationalized through sophisticated computational algorithms.

The continued advancement of pharmacophore methodologies—including machine learning integration, automated workflows, and dynamic modeling—ensures that Ehrlich's century-old concept remains not only relevant but increasingly central to modern drug discovery. As these computational approaches continue to evolve in sophistication and predictive power, they bring us closer to the ultimate realization of Ehrlich's vision: truly selective therapeutic agents that maximize efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. The integration of these advanced computational techniques with experimental validation represents the most promising path forward for addressing the complex therapeutic challenges of the 21st century.

In modern computer-aided drug design, the pharmacophore concept serves as an indispensable abstraction that captures the essential steric and electronic features required for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger or block its biological response [15]. According to the official IUPAC definition, a pharmacophore represents "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [15]. This abstract description enables the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share common interaction patterns, facilitating scaffold hopping in drug discovery projects [15] [16].

The fundamental pharmacophoric features include hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic groups (H), and ionizable groups (positive and negative), each responsible for specific non-bonding interactions with complementary target features [15]. This application note details the characteristics, geometric representation, and experimental considerations for these key features within the context of pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflows, providing researchers with practical protocols for implementing these concepts in their drug discovery pipelines.

Core Pharmacophoric Features: Definitions and Interactions

Feature Specifications and Geometric Representations

Table 1: Core pharmacophoric features and their characteristics

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Complementary Feature Type(s) | Interaction Type(s) | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | HBD | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Carboxylates, Ketones, Alcoholes, Fluorine Substituents |

| Hydrogen-Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | HBA | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Amides, Alcoholes |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | AR, PI | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Any aromatic Ring |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | AR, NI | Ionic, Cation-π | Ammonium Ion, Metal Cations |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | PI | Ionic | Carboxylates |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | H | Hydrophobic Contact | Halogen Substituents, Alkyl Groups, Alicycles, weakly or non-polar arom. Rings |

Vector and plane representations are typically employed for feature types whose interactions are directed and require specific mutual orientation of complementary features, while spheres are used for features with undirected interactions or where orientation cannot be determined [15]. For example, rotatable -OH groups are typically represented as spheres rather than vectors due to their conformational flexibility [15].

Quantitative Analysis of Feature Contributions

Table 2: Quantitative impact of pharmacophoric features on binding interactions

| Feature Combination | Target | Experimental Context | Impact on Binding/Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-bond + Hydrophobic + Electrostatic | CD38 | Covalent Inhibitors QSAR | CoMFA: q²=0.564, r²=0.967; CoMSIA: q²=0.571, r²=0.971 [17] |

| H-bond + Hydrophobic | CD38 | Non-covalent Inhibitors (F12 analogues) | CoMFA: q²=0.469, r²=0.814; CoMSIA: q²=0.454, r²=0.819 [17] |

| HBA, HBD, Aromatic (ADRRR_2) | FGFR1 | Pharmacophore Validation | Optimal model with 5 features; AUC approaching 1.0 indicates high discriminatory power [16] |

Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies demonstrate that specific feature combinations significantly correlate with biological activity. For CD38 inhibitors, the essential interactions include hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions with residues Glu226 and Trp125, electrostatic or hydrogen bond interaction with the positively charged residue Arg127 region, and hydrophobic interaction with residue Trp189 [17]. The quality of these quantitative relationships is evidenced by the high cross-validated correlation coefficients (q²) and non-cross-validated values (r²) obtained in these studies [17].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Model Development

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

Objective: To generate a structure-based pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex that captures essential interactions for virtual screening.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank structure (PDB format)

- Molecular docking software (e.g., PLANTS1.2, Glide)

- Pharmacophore modeling platform (e.g., LigandScout, Schrödinger Maestro)

- Compound library for screening (e.g., NCI library, TargetMol Anticancer Library)

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D protein structure from PDB (e.g., FGFR1 with PDB ID: 4ZSA) [16]

- Import into Maestro Protein Preparation Wizard for pre-processing

- Add hydrogen atoms considering physiological pH conditions

- Detect and rectify errors or incomplete residues

- Retain or remove water molecules based on structural significance

- Assign and validate disulfide bonds

- Minimize protein structure energy using OPLS 3e force field

Ligand Preparation:

- Curate bioactive small molecules with experimentally validated IC50 values

- Generate energetically optimized 3D conformations using LigPrep module

- Perform structural corrections: Lewis structure validation, bond order normalization, stereochemical ambiguity resolution

Interaction Analysis:

- Load the protein-ligand complex into pharmacophore modeling software

- Automatically identify key interactions between ligand and binding site

- Map hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic interactions

- Define feature tolerances based on observed interaction geometries

Exclusion Volume Assignment:

- Generate exclusion volumes representing forbidden regions in the binding pocket

- Define spatial constraints based on protein atom positions

- Adjust volume sizes to account for protein flexibility

Model Validation:

- Screen known active and inactive compounds

- Calculate enrichment factors and ROC curves

- Optimize model sensitivity and specificity through iterative refinement

Expected Outcome: A validated structure-based pharmacophore model containing 4-7 essential features with defined spatial relationships and exclusion volumes, capable of discriminating active from inactive compounds in virtual screening [16].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

Objective: To develop a ligand-based pharmacophore model from a set of known active compounds that share a common mechanism of action.

Materials:

- Set of 3-20 known active compounds with determined IC50/Ki values

- Conformational analysis software (e.g., iConfGen)

- Pharmacophore generation tools (e.g., Schrödinger Phase, HypoGen)

Procedure:

- Compound Selection and Conformational Analysis:

- Select structurally diverse active compounds spanning a range of potencies

- Generate representative 3D conformations using iConfGen with default settings

- Set maximum number of output conformations to 25 per compound

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation:

- Identify common chemical features across the active compound set

- Align molecules based on their pharmacophoric features

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses using algorithms like HypoGen

Model Optimization and Validation:

- Set hypothesis coverage threshold to 15% to optimize model sensitivity while maintaining specificity [16]

- Constrain feature complexity to 4-7 pharmacophoric features

- Validate model using database-searching approach with ROC curve analysis

- Select optimal model based on highest validation score and feature complementarity

Expected Outcome: A validated ligand-based pharmacophore model that represents the essential structural features common to active compounds, enabling the identification of novel scaffolds through virtual screening [16].

Advanced Implementation Workflows

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflow that integrates both structure-based and ligand-based approaches for identifying novel bioactive compounds:

Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening (FragmentScout)

Objective: To identify micromolar hits from millimolar fragments by aggregating pharmacophore feature information from experimental fragment poses.

Materials:

- XChem high-throughput crystallographic fragment screening data

- FragmentScout workflow software

- Inte:ligand LigandScout XT software

- 3D conformational databases

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation:

- Collect structural data from Diamond LightSource XChem fragment screening

- Extract all experimental fragment poses from binding site analyses

Joint Pharmacophore Query Generation:

- Generate a joint pharmacophore query for each binding site

- Aggregate pharmacophore feature information present in each experimental fragment pose

- Define spatial tolerances based on observed fragment binding modes

Virtual Screening:

- Use the joint pharmacophore query to search 3D conformational databases

- Apply Inte:ligand LigandScout XT software for similarity matching

- Rank compounds based on pharmacophore fit score

Hit Validation:

- Select top-ranking compounds for biochemical assays

- Validate hits in cellular antiviral and biophysical ThermoFluor assays

- Confirm micromolar potency in dose-response experiments

Expected Outcome: Identification of novel micromolar potent inhibitors from initially millimolar fragments, as demonstrated by the discovery of 13 novel SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase inhibitors [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and software for pharmacophore-based screening

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | LigandScout | Pharmacophore model generation and virtual screening | SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase inhibitor discovery [18] |

| Schrödinger Maestro | Integrated drug discovery platform | FGFR1 inhibitor pharmacophore modeling [16] | |

| O-LAP | Shape-focused pharmacophore modeling | Docking enrichment improvement [19] | |

| ELIXIR-A | Python-based pharmacophore refinement | Multi-target pharmacophore alignment [20] | |

| Compound Libraries | NCI Database | Small molecule screening library | KHK-C inhibitor discovery (460,000 compounds) [21] |

| TargetMol Anticancer Library | Curated anticancer compounds | FGFR1 inhibitor screening (8,691 compounds) [16] | |

| DUD-E/DUDE-Z | Benchmarking decoy sets | Method validation and benchmarking [19] | |

| Computational Methods | QPHAR | Quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship | Building predictive models from pharmacophores [8] |

| HypoGen Algorithm | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling | Catalyst/Discovery Studio platform [8] | |

| PHASE | Pharmacophore field-based QSAR | 3D-QSAR with pharmacophore fields [8] |

Case Studies and Applications

FGFR1 Inhibitor Discovery

In a recent study targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), researchers developed a multiligand consensus pharmacophore model using Maestro 11.8 [16]. The optimal model (ADRRR_2) contained five critical pharmacophoric features: hydrogen-bond acceptors (A), donors (D), and aromatic rings (R). Virtual screening of 8,691 compounds from the TargetMol Anticancer Library required a minimum of four matched pharmacophoric features for compound retention [16]. This approach identified three hit compounds with superior FGFR1 binding affinity compared to the reference ligand, demonstrating the efficacy of pharmacophore-based screening for targeted cancer therapy.

KHK-C Inhibitor Discovery for Metabolic Disorders

In the search for ketohexokinase C (KHK-C) inhibitors to treat fructose metabolic disorders, researchers employed pharmacophore-based virtual screening of 460,000 compounds from the National Cancer Institute library [21]. Multi-level molecular docking identified ten compounds with docking scores ranging from -7.79 to -9.10 kcal/mol, superior to clinical candidates PF-06835919 (-7.768 kcal/mol) and LY-3522348 (-6.54 kcal/mol) [21]. The calculated binding free energies of these hits ranged from -57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol, further demonstrating their superiority. ADMET profiling refined the selection to five compounds, with molecular dynamics simulations identifying the most stable candidate for further development.

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR)

The QPHAR method represents a novel approach to construct quantitative pharmacophore models, validated on more than 250 diverse datasets [8]. This method first finds a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples, then aligns input pharmacophores to this merged model. The relative position information serves as input to a machine learning algorithm that derives a quantitative relationship between the pharmacophore features and biological activities [8]. Cross-validation studies on datasets with 15-20 training samples demonstrated that robust quantitative pharmacophore models could be obtained with an average RMSE of 0.62 and standard deviation of 0.18, making this approach particularly valuable for lead optimization stages with limited data [8].

Structure-Based vs Ligand-Based Model Generation Approaches

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, serving as an efficient strategy to identify novel bioactive molecules from extensive chemical libraries. This methodology primarily branches into two distinct yet complementary paradigms: structure-based and ligand-based model generation approaches. The fundamental distinction lies in their source of information; structure-based methods derive pharmacophore features directly from the three-dimensional structure of a biological target, typically a protein, while ligand-based methods infer these critical features from a set of known active compounds [22].

The strategic selection between these approaches is often dictated by the availability of experimental data. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) is applicable when a reliable 3D structure of the target exists, obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy, or predicted via computational models such as AlphaFold [22] [23]. In contrast, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) becomes the method of choice when the target's structure is unknown but a collection of confirmed active ligands is available, a common scenario in early-stage drug discovery for targets like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [24] [25]. This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of these methodologies, supported by structured protocols and resource guides to facilitate their application in rational drug design.

Comparative Analysis: Fundamental Principles and Applications

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Approaches

| Feature | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | 3D protein structure (experimental or predicted) [22] | Set of known active ligands [24] |

| Key Prerequisite | Target structure availability | Sufficient known actives for pattern recognition |

| Typical Output | Pharmacophore map of the binding site [26] [27] | Feature set common to active molecules |

| Major Advantage | Rational design without prior ligands; novel scaffold discovery [25] | High speed and scalability; no need for target structure [22] [28] |

| Primary Limitation | Dependency on structure quality and accuracy [22] | Limited by chemical diversity of known actives [22] |

| Ideal Application Context | Novel targets with resolved structures; selective inhibitor design [23] | Targets with no structure but many known binders; scaffold hopping [24] |

The workflow and logical relationship between these approaches, including opportunities for their integration, can be visualized as follows:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Protocols and Workflows

Core Principles and Experimental Evidence

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling leverages the 3D architecture of a protein's binding site to identify essential interaction features a ligand must possess for effective binding. This approach is particularly powerful for targets with no known ligands, enabling de novo ligand discovery [25]. A prominent example is the discovery of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase inhibitors using the FragmentScout workflow. This method aggregated pharmacophore feature information from experimental fragment poses generated by XChem high-throughput crystallographic screening, creating a joint pharmacophore query that successfully identified 13 novel micromolar potent inhibitors from a vast chemical space [18].

Another compelling application targeted the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), a cancer-related target. Researchers generated a structure-based pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW), identifying 14 key chemical features—including hydrophobics, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and a positive ionizable feature. This model was rigorously validated, achieving an excellent Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.98, and subsequently used to screen natural product databases, leading to the identification of stable, low-toxicity candidate inhibitors confirmed by molecular dynamics simulations [26].

Detailed Protocol for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Software for Structure-Based Modeling

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Example Tools/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure | 3D coordinates of the binding site for analysis. | PDB, AlphaFold, SWISS-MODEL [22] [27] |

| Molecular Fragments Library | Small functional groups used to probe interaction potential in the binding site. | MCSS Functional Group Fragments [25] |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Generates pharmacophore features by analyzing protein-ligand interactions or probing the apo binding site. | LigandScout, Pharmit, CMD-GEN [18] [23] [27] |

| Virtual Screening Database | Large collection of compounds for screening against the pharmacophore model. | ZINC, CHEMBL, MCULE, NCI [21] [26] [27] |

The workflow for generating a structure-based pharmacophore model, from data preparation to virtual screening, follows a structured pipeline:

Protocol Steps:

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or via homology modeling (e.g., SWISS-MODEL, AlphaFold). Prepare the structure by removing water molecules (except structurally relevant ones), adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning correct protonation states [27].

- Binding Site Definition: Identify the key cavity where ligands bind. Use computational tools like CASTp or PrankWeb to analyze the protein surface and define the active site residues [26] [27].

- Interaction Feature Mapping: Analyze the binding site to pinpoint crucial chemical features. This can be done by:

- Examining a co-crystallized ligand-protein complex to extract features from their interactions (e.g., using LigandScout) [26].

- Using a fragment-based probing method like Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) to place functional groups (e.g., carbonyl, methyl, alcohol) into the apo binding site and identify energetically favorable interaction points (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas, charged regions) [25].

- Pharmacophore Model Generation & Validation: Convert the mapped interaction points into a pharmacophore model comprising spatially arranged features. Critically validate the model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from decoy molecules. Use metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC). A successful model should have an AUC significantly >0.5 (random selection), with high-performing models often exceeding 0.8 [29] [26].

- Virtual Screening & Hit Selection: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large compound databases (e.g., ZINC, ChemDiv). Select compounds that match the pharmacophore features for further analysis, such as molecular docking and ADMET profiling [21] [27].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Protocols and Workflows

Core Principles and Experimental Evidence

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling deduces the essential structural features for biological activity by finding the common pharmacophore hypothesis among a set of known active molecules. This approach is grounded in the principle that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [24] [22]. Its major strength lies in its applicability when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown.

Advanced ligand-based methods extend beyond simple 2D fingerprint similarity. For instance, the HWZ score-based virtual screening approach combines an effective shape-overlapping procedure with a robust scoring function. When tested across 40 diverse protein targets, this method demonstrated strong and consistent performance, with an average AUC of 0.84 and high early enrichment, successfully identifying active compounds even for challenging targets [24]. For rapid screening, open-source tools like VSFlow leverage RDKit to perform both 2D fingerprint-based similarity searches and 3D shape-based screenings, which align candidate molecules to a query compound based on their molecular volume and pharmacophore features [28].

Detailed Protocol for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software for Ligand-Based Modeling

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Example Tools/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Set of Known Active Ligands | A curated collection of molecules with confirmed activity and potency (IC50, Ki) against the target. | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [24] [28] |

| Chemical Database for Screening | A virtual library of compounds to be searched for novel hits. | ZINC, MCULE, MolPort, In-house Libraries [29] [28] |

| Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Software that identifies common 3D chemical features from aligned active ligands. | VSFlow, ROCS, Phase [22] [28] |

| Conformational Sampling Tool | Generates representative 3D conformations for each molecule to account for flexibility. | RDKit (ETKDGv3), OMEGA [28] |

Protocol Steps:

- Ligand Set Curation and Preparation: Compile a set of known active compounds with diverse structures but a common mechanism of action. Prepare the ligands by generating representative 3D conformations to account for molecular flexibility. Tools like RDKit's ETKDGv3 method are well-suited for this task [28].

- Molecular Alignment and Common Feature Identification: Superimpose the prepared active ligands in 3D space to find their optimal spatial alignment. The goal is to identify a set of chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic groups, aromatic rings) that are common across all or most of the active molecules and are spatially consistent [22].

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation & Validation: Based on the alignment, generate one or more pharmacophore hypotheses. Validate the model's quality by testing its ability to correctly rank active molecules above known inactives or decoys. Use ROC curves and Enrichment Factors at early recovery (e.g., EF1%) to quantify performance. An EF1% value of 10, for example, means the model is 10 times better than random selection at identifying actives in the top 1% of the screened database [24] [26].

- Database Screening and Hit Identification: Use the validated pharmacophore model to search 3D databases of available compounds. Select hits that match the pharmacophore query for further experimental validation or as input for more computationally intensive structure-based methods [22].

Integrated and Advanced Approaches

The integration of structure-based and ligand-based methods creates a powerful synergistic workflow that mitigates the limitations of each individual approach [22]. A common strategy is to use a fast ligand-based screen to narrow down a large chemical library to a more manageable set of candidates, which are then processed by a more computationally demanding structure-based docking simulation [22]. This sequential integration improves overall efficiency.

Cutting-edge research is focused on incorporating Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning. For example, the CMD-GEN framework uses a deep generative model that begins with coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled within a protein pocket. It then hierarchically generates molecules that align with these pharmacophoric constraints, effectively bridging the gap between protein structure and drug-like chemical space. This approach has shown promise in the challenging task of designing selective inhibitors, as validated with PARP1/2 inhibitors [23]. Furthermore, machine learning models can now be trained to predict which structure-based pharmacophore models are likely to achieve high enrichment in virtual screens, aiding in model selection for targets with no known ligands [25].

The Role of Exclusion Volumes and Shape Constraints

In the realm of computer-aided drug design, pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) stands as a powerful technique for identifying novel bioactive compounds. A pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [30] [31]. While the fundamental chemical features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, charged groups, and hydrophobic regions—form the core of any pharmacophore model, the incorporation of three-dimensional shape information significantly enhances their screening accuracy and practical utility.

Exclusion volumes and shape constraints represent critical components for introducing geographic specificity into pharmacophore models. Exclusion volumes (or excluded volumes) sterically define the region occupied by the protein binding site, preventing the selection of compounds that would clash with the receptor [19] [30]. Shape constraints provide a more nuanced approach by defining both minimum and maximum spatial boundaries that potential ligands must occupy [32]. These complementary techniques address a key limitation of traditional feature-based pharmacophores: their inability to adequately represent the spatial constraints imposed by the protein binding pocket.

This application note details the theoretical foundation, practical implementation, and experimental protocols for effectively utilizing exclusion volumes and shape constraints within pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflows, providing researchers with actionable methodologies for enhancing their drug discovery campaigns.

Theoretical Foundation

Exclusion Volumes in Pharmacophore Modeling

Exclusion volumes are implemented as spheres or regions in space that ligands must avoid during the pharmacophore matching process [19] [30]. They represent the physical boundaries of the binding pocket, essentially defining where atoms from a potential ligand cannot be located without causing steric clashes with the receptor. When generating structure-based pharmacophore models, exclusion volumes are typically added automatically by software platforms around the protein atoms bordering the binding site [6] [30].

The strategic application of exclusion volumes significantly enhances the selectivity of virtual screening by filtering out compounds that, while matching the essential chemical features, would sterically conflict with the receptor architecture. This approach mimics the natural selection process where only complementarily shaped molecules can successfully bind to a protein target.

Shape Constraints and Molecular Shape Representation

Shape constraints extend beyond simple exclusion by precisely defining the volumetric space that a ligand should occupy. The Volumetric Aligned Molecular Shapes (VAMS) approach introduces a sophisticated implementation of this concept, utilizing minimum and maximum shape constraints [32]:

- Minimum Shape Constraints: Define the core volume that must be occupied by the ligand, ensuring essential contacts with the receptor are maintained.

- Maximum Shape Constraints: Define the outer boundaries that the ligand must not exceed, preventing clashes with the binding site walls.

In VAMS, molecular shapes are represented as solvent-excluded volumes calculated from heavy atoms using a water probe radius of 1.4Å, which are then discretized onto a 0.5Å resolution grid where each grid point represents a voxel (a three-dimensional pixel) [32]. This volumetric representation faithfully captures molecular shape up to the chosen resolution and enables efficient comparison and constraint application.

Shape constraints can be derived from multiple sources:

- Reference Ligands: By shrinking a known active ligand's shape to create a minimum constraint and growing it to create a maximum constraint [32].

- Protein Binding Sites: By using the receptor's binding cavity shape directly, potentially shrunk by a gap distance to account for minor clashes and binding site plasticity [32].

Quantitative Shape Similarity Assessment

The shape similarity between two molecules or between a molecule and a constraint is quantitatively evaluated using metrics such as the shape Tanimoto coefficient:

δ(A,B) = A∩B / A∪B

where A and B represent the voxelized volumes of two molecular shapes [32]. This coefficient measures spatial overlap normalized by the merged volume, ranging from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (identical shapes).

Table 1: Common Shape Similarity Metrics in Virtual Screening

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape Tanimoto | A∩B / A∪B | 0-1 scale; higher values indicate better overlap | General shape similarity [32] |

| Combo Score | ShapeTanimoto + ColorScore | Combined shape and chemical feature similarity | ROCS-like approaches [19] |

| Volume Overlap | A∩B | Absolute overlapping volume | Constraint satisfaction [32] |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation with Exclusion Volumes

This protocol details the creation of a structure-based pharmacophore model incorporating exclusion volumes using a protein-ligand complex as starting point.

Required Materials and Software:

- Protein-ligand complex structure (PDB format)

- Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, Maestro)

- Pharmacophore modeling platform (e.g., LigandScout, Catalyst, MOE)

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Load the protein-ligand complex structure into your preferred pharmacophore modeling software.

- Add hydrogen atoms to the protein structure using standard protonation states at physiological pH.

- Perform energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while keeping heavy atoms constrained.

Binding Site Analysis:

- Define the binding site around the co-crystallized ligand, typically using a sphere of 5-10Å radius from the ligand centroid.

- Identify key protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions).

Pharmacophore Feature Extraction:

- Automatically generate pharmacophoric features from the protein-ligand interactions.

- Select essential features with direct catalytic or binding importance.

- Remove redundant features to create a minimal but sufficient model.

Exclusion Volume Application:

- Automatically add exclusion volumes around protein atoms within the binding site.

- Adjust exclusion volume radii based on atom van der Waals radii plus a tolerance factor (typically 0.5-1.0Å).

- Manually review and refine exclusion volumes in regions with known protein flexibility.

Model Validation:

- Verify that the original ligand matches all pharmacophore features while avoiding exclusion volumes.

- Test known active and inactive compounds to validate model selectivity.

- Optimize feature tolerances based on validation results.

The workflow below illustrates this structure-based pharmacophore generation process:

Protocol 2: Shape-Focused Pharmacophore Modeling Using O-LAP

The O-LAP algorithm generates shape-focused pharmacophore models through graph clustering of docked ligand poses, offering an alternative to structure-based approaches.

Required Materials and Software:

- Set of active ligands for the target

- Molecular docking software (e.g., PLANTS, Glide)

- O-LAP software (C++/Qt5 based, available under GNU GPL v3.0)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Prepare 3D structures of known active ligands using tools like LIGPREP in Maestro.

- Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each ligand to account for flexibility.

Flexible Molecular Docking:

- Perform flexible docking of active ligands into the target binding site.

- Retain the top 50 poses based on docking scores for model building.

Atomic Clustering:

- Merge the docked ligand structures and remove non-polar hydrogen atoms.

- Apply O-LAP's pairwise distance graph clustering to group overlapping atoms.

- Use atom-type-specific radii for distance measurements during clustering.

Model Generation:

- Generate representative centroids from clustered atoms to form the shape-focused model.

- Define pharmacophoric features based on the chemical characteristics of clustered atoms.

Enrichment Optimization:

- Use training and test sets of active compounds and decoys to validate model performance.

- Apply greedy search optimization to improve enrichment factors if necessary.

- Adjust cluster parameters to balance model specificity and sensitivity.

Table 2: Comparison of Exclusion Volume and Shape Constraint Implementation

| Characteristic | Exclusion Volumes | Shape Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Spheres indicating forbidden regions | Minimum/maximum volumetric boundaries |

| Data Sources | Protein structure alone | Reference ligands or protein cavity [32] |

| Implementation | Automatic addition in structure-based modeling | Requires shape alignment and voxelization [32] |

| Flexibility | Fixed based on static protein structure | Adjustable via gap distance parameter [32] |

| Primary Function | Prevent steric clashes | Ensure optimal shape complementarity |

| Computational Cost | Low (simple distance checks) | Moderate to high (volume comparisons) |

Protocol 3: VAMS-Based Screening with Shape Constraints

The Volumetric Aligned Molecular Shapes (VAMS) method provides a specialized approach for shape-based screening with unique constraint capabilities.

Required Materials and Software:

- Reference ligand or protein binding site structure

- VAMS-compatible shape processing tools

- Compound database in appropriate 3D format

Procedure:

- Molecular Shape Representation:

- Calculate solvent-excluded volumes for all compounds using a water probe radius of 1.4Å.

- Discretize molecular volumes onto a 0.5Å resolution grid, storing as voxelized representations.

- Align all molecules to a canonical coordinate system based on principal axes of inertia.

Shape Constraint Definition:

- For reference ligand-based constraints: shrink the ligand shape by desired gap distance to create minimum constraint; grow the shape to create maximum constraint.

- For receptor-based constraints: use the binding cavity volume as maximum constraint (inverse represents excluded volume).

- Adjust gap distance to control constraint strictness (smaller gap = stricter constraint).

Shape Database Searching:

- Use efficient data structures (GSS-tree) for sub-linear search times [32].

- Perform rapid matching against shape constraints using hierarchical volume comparisons.

- Retrieve compounds that satisfy both minimum and maximum shape constraints.

Hit Analysis and Validation:

- Calculate shape Tanimoto coefficients for top matches.

- Visually inspect alignment of hits with original constraints.

- Progress selected compounds to experimental validation or further computational analysis.

Practical Applications and Case Studies

Application in Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

In a study targeting Akt2 kinase for cancer therapy, researchers developed a structure-based pharmacophore model containing seven pharmacophoric features complemented by exclusion volumes derived from the protein structure (PDB: 3E8D) [33]. The model comprised two hydrogen bond acceptors, one hydrogen bond donor, four hydrophobic groups, and eighteen exclusion volume spheres. Virtual screening of natural product and commercial databases using this model identified novel scaffold hits with predicted high activity and favorable ADMET properties, demonstrating the utility of exclusion volumes in distinguishing viable lead compounds [33].

Shape-Based Screening for SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutics

The VAMS approach has been applied in shape-based virtual screening campaigns targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteins [32]. By creating shape constraints from known active ligands or directly from the viral protein binding sites, researchers could rapidly screen millions of compounds while precisely controlling the desired molecular dimensions. This method proved particularly valuable for targeting conserved binding sites across coronavirus species, where shape complementarity plays a crucial role in inhibitor efficacy.

Performance Benchmarking

A comprehensive benchmark comparison against eight diverse protein targets revealed that pharmacophore-based virtual screening methods generally outperformed docking-based approaches in retrieval of active compounds [34]. The incorporation of exclusion volumes and shape constraints contributed significantly to this enhanced performance by reducing false positives that would sterically clash with the receptor while maintaining sensitivity for true actives.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods

| Target Protein | PBVS EF¹ | DBVS EF¹ | Advantage Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | 45.2 | 28.7 | 1.57× |

| AChE | 51.8 | 32.4 | 1.60× |

| Androgen Receptor | 38.5 | 25.1 | 1.53× |

| DacA | 42.7 | 24.9 | 1.71× |

| DHFR | 55.3 | 31.8 | 1.74× |

| ERα | 47.6 | 29.5 | 1.61× |

| HIV Protease | 53.1 | 33.2 | 1.60× |

| Thymidine Kinase | 44.9 | 27.6 | 1.63× |

¹Enrichment Factor at 2% false positive rate [34]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Shape-Based Pharmacophore Screening

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Pharmacophore model generation and screening | Structure- and ligand-based model creation with exclusion volumes [6] [30] |

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) | Shape-based molecular alignment and screening | Ligand-centric shape similarity screening [32] [19] |

| VAMS Implementation | Volumetric shape alignment and constraint screening | Shape constraint-based screening with minimum/maximum volumes [32] |

| O-LAP Algorithm | Graph clustering for shape-focused pharmacophores | Generation of clustered pharmacophore models from docked poses [19] |

| PLANTS Docking | Flexible molecular docking | Pose generation for structure-based pharmacophore modeling [19] |

| ZINC Database | Source of commercially available compounds | Large-scale compound libraries for virtual screening [35] |

| DUDE-Z Database | Benchmarking sets with decoy compounds | Method validation and performance assessment [19] |

Exclusion volumes and shape constraints represent essential components of modern pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflows, significantly enhancing screening enrichment by incorporating critical spatial constraints derived from the target protein structure. The methodologies presented in this application note—from structure-based pharmacophores with exclusion volumes to advanced shape constraint approaches like VAMS and O-LAP—provide researchers with powerful tools for addressing the challenge of molecular shape complementarity in drug discovery.

As virtual screening continues to evolve, the integration of these geometric constraints with traditional chemical feature-based pharmacophores will remain crucial for identifying novel bioactive compounds with optimal fit to their biological targets. The experimental protocols outlined herein offer practical guidance for implementation, while the performance benchmarks demonstrate the tangible benefits of these approaches across diverse target classes.

Molecular representation serves as a critical foundation for computational chemistry and modern drug discovery, creating a bridge between chemical structures and their biological activity. These representations convert molecules into mathematical or computational formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior and properties. The evolution of representation methods has dramatically transformed early-stage drug discovery, enabling efficient navigation of vast chemical spaces for tasks including virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping [36]. In the specific context of pharmacophore-based virtual screening—a methodology that identifies potential drug candidates by mapping essential interaction features with a biological target—the choice of molecular representation directly influences the success of identifying viable lead compounds. This application note details the transition from traditional abstract representations to sophisticated 3D geometric models, providing structured protocols and resources to facilitate their application in rational drug design campaigns.

Fundamental Concepts and Representation Types

Molecular representations can be broadly categorized into traditional methods, which rely on predefined rules and descriptors, and modern artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches, which learn complex features directly from data.

Traditional Molecular Representations

Traditional methods have formed the backbone of computational chemistry for decades. The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) is a string-based notation that describes a molecule's structure using ASCII strings, representing atoms, bonds, and branching with specific symbols and parentheses. While human-readable and compact, SMILES has inherent limitations in capturing molecular spatial complexity and nuanced structure-activity relationships [36]. Molecular fingerprints, such as Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP), encode substructural information as binary bit strings or numerical vectors, facilitating rapid similarity comparisons and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling [36]. Molecular descriptors quantify physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) to create a numerical profile of a molecule [36].

Modern AI-Driven Representations

AI-driven approaches leverage deep learning to generate continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings:

- Language Model-Based Representations: Models like Transformers process SMILES strings as a chemical "language," learning contextual relationships between tokens (atoms or substructures) to create predictive representations [36].

- Graph-Based Representations: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) natively represent molecules as graphs where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. This effectively captures both local atomic environments and global topological structure [36].

- 3D Geometric Representations: These models incorporate spatial information, representing molecules as 3D point clouds or surfaces. Equivariant neural networks ensure predictions are invariant to rotational and translational transformations, which is crucial for modeling molecular interactions and pharmacophore mapping [37].

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Representation Methods

| Representation Type | Format | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | String | Simple, compact, human-readable | Basic database storage, initial input for AI models |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Binary/Numerical Vector | Computational efficiency, similarity search | QSAR, virtual screening, clustering |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical Vector | Interpretable, based on physicochemical properties | QSAR, property prediction |

| Language Model Embeddings | High-dimensional Vector | Captures contextual structural information | Activity prediction, molecular generation |

| Graph-Based Embeddings | High-dimensional Vector | Captures topological structure natively | Property prediction, lead optimization |

| 3D Geometric Models | 3D Point Cloud/Coordinates | Encodes spatial and stereochemical information | Structure-based design, pharmacophore modeling |

Application Protocols in Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

The following protocols outline how different molecular representations are practically implemented within a pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflow. This process aims to identify novel compounds that match the essential interaction features of a target protein's binding site.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol generates a pharmacophore model directly from a protein-ligand complex structure.

- Input Data Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein with a bound ligand from a reliable database such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [38].

- Interaction Feature Extraction: Use software such as LigandScout or Discovery Studio to automatically analyze the complex and identify key interaction features between the ligand and the protein binding pocket. These features include:

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrophobic (H) regions

- Aromatic (AR) rings

- Positive/Negative Ionizable areas [38]

- Model Generation and Refinement: The software generates an initial 3D pharmacophore hypothesis consisting of the identified features. Manually refine this model by:

- Adjusting feature tolerances (size and location flexibility).

- Adding Exclusion Volumes (XVols), which are steric constraints that mimic the protein's binding pocket geometry and prevent the mapping of compounds that would sterically clash with the protein [38].

- Theoretical Validation: Validate the model's quality before use by screening a dataset containing known active and inactive compounds. Calculate enrichment metrics like the Enrichment Factor and ROC-AUC to ensure the model can successfully prioritize active molecules [38].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol is used when the 3D protein structure is unavailable, but a set of active ligands is known.

- Training Set Curation: Compile a set of 3-7 known active molecules with diverse structures but similar biological activity. Ensure their direct interaction with the target has been experimentally proven [38].