Pharmacophore Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a thorough exploration of pharmacophore modeling, a cornerstone concept in modern computer-aided drug design.

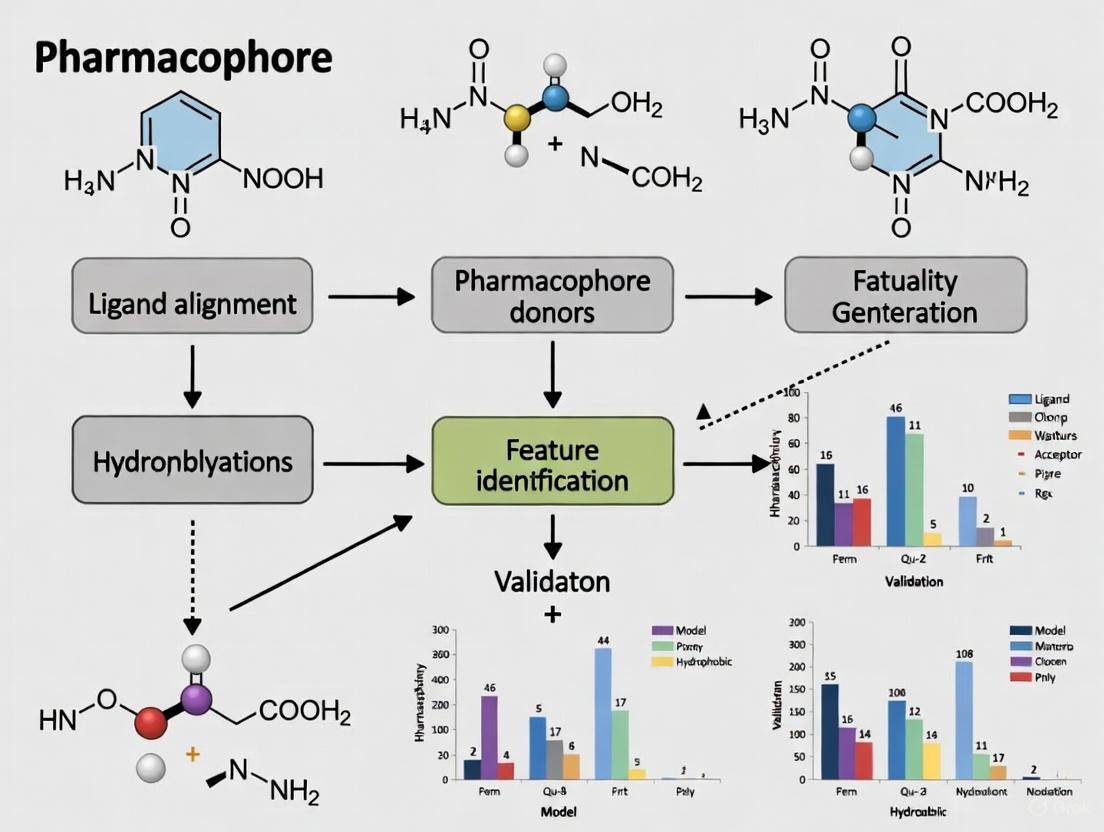

Pharmacophore Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of pharmacophore modeling, a cornerstone concept in modern computer-aided drug design. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of pharmacophores as ensembles of steric and electronic features essential for biological activity. The scope extends from ligand-based and structure-based model generation methods to practical applications in virtual screening and lead optimization. It further addresses critical challenges, validation techniques, and a comparative analysis with other computational methods, offering a complete resource for leveraging pharmacophores to accelerate and rationalize the drug discovery pipeline.

What is a Pharmacophore? Unpacking the Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

The pharmacophore concept stands as a foundational pillar in modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), providing an abstract framework that bridges molecular structure and biological activity. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that define the optimal supermolecular intermolecular interaction of a ligand with a specific biological target structure with the result that it triggers or blocks its biological response" [1]. This definition captures the essential principle that biological activity arises from a specific three-dimensional arrangement of molecular features necessary for target recognition, rather than from a particular chemical scaffold [2]. The conceptual evolution of pharmacophores dates back to the late 19th century with Paul Ehrlich's introduction of "toxophores" as peripheral chemical groups responsible for binding and eliciting biological effects [2]. The term was later refined by Frederick W. Schueler in 1960 to emphasize spatial patterns of abstract molecular features, ultimately evolving into the contemporary understanding through the work of Lemont B. Kier between 1967 and 1971 [2].

In contemporary drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling serves as a crucial tool for understanding ligand-target recognition without requiring detailed atomic structures [2]. By abstracting specific functional groups into generalized chemical features, pharmacophore models enable the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share common biological activity—a process known as scaffold hopping [3] [4]. This abstraction makes pharmacophores particularly valuable in virtual screening, where they filter vast compound libraries to identify potential hits by matching molecular features against predefined models [3] [2]. The versatility of pharmacophore approaches extends beyond virtual screening to include lead optimization, de novo drug design, multitarget drug profiling, and target identification [3].

Core Principles and Feature Definitions

Essential Steric and Electronic Features

At its core, a pharmacophore model represents the three-dimensional arrangement of molecular features necessary for optimal interaction with a biological target. These features are abstract representations of chemical functionalities rather than specific atoms or functional groups [3]. The most fundamental pharmacophore features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic rings (AR), and metal coordinating areas [3]. These features are typically represented as geometric entities such as spheres, planes, and vectors in three-dimensional space, with tolerance ranges that account for molecular flexibility and variations in chemical structure [3] [2].

Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are crucial for mediating specific electrostatic interactions with complementary features in the target binding site [2]. Hydrogen bond acceptors typically involve atoms with lone pairs such as oxygen or nitrogen in carbonyl or ether groups, while donors often include N-H or O-H moieties [2]. Ionizable groups introduce charges that enhance electrostatic interactions through salt bridges or ionic hydrogen bonds, with positive ionizable features (e.g., protonated amines) and negative ionizable features (e.g., carboxylate groups) modeled based on their protonation states at physiological pH [2]. Hydrophobic features, including alkyl chains and pi-systems such as aromatic rings, drive non-polar associations that stabilize binding through van der Waals contacts and pi-stacking interactions with non-polar residues [2]. These features are typically modeled as Gaussian volumes or spheres encompassing 4-6 Å, promoting desolvation and burial in lipophilic environments [2].

Geometric Tolerances and Molecular Flexibility

A critical aspect of pharmacophore modeling involves accounting for molecular flexibility through geometric tolerances [2]. Unlike rigid structural models, pharmacophores incorporate allowable deviations in feature placement to reflect the dynamic nature of molecular interactions. These tolerances typically include distance ranges between features (typically ±1.0–1.5 Å) and angular deviations (e.g., ±30° for directed interactions like hydrogen bonds) [2]. These allowances reflect experimental variability in crystal structures and computational approximations, enabling robust matching during virtual screening without demanding exact overlaps [2]. Without such tolerances, models would be overly stringent, reducing their predictive utility for diverse chemical scaffolds [2].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Moieties | Spatial Representation | Tolerance Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Carbonyl oxygen, Ether oxygen | Vector or sphere | Distance: ±1.0–1.5 Å, Angle: ±30° |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | N-H, O-H groups | Vector or sphere | Distance: ±1.0–1.5 Å, Angle: ±30° |

| Hydrophobic Region | Alkyl chains, Aromatic rings | Sphere or volume | Radius: 4-6 Å |

| Positive Ionizable | Protonated amines | Sphere | pKa range: 7-10 |

| Negative Ionizable | Carboxylates, Phosphates | Sphere | pKa range: 3-5 |

| Aromatic Ring | Phenyl, Heterocycles | Plane or centroid | Planar orientation tolerance |

The principle of superposition forms the cornerstone of pharmacophore modeling, involving the alignment of multiple ligand structures in three-dimensional space to identify overlapping chemical features that correlate with biological activity [2]. This process assumes that active molecules share a common spatial arrangement of interaction points, allowing for the extraction of a representative pharmacophore hypothesis [2]. Conformational flexibility is another critical consideration, as ligands often possess rotatable bonds that enable diverse three-dimensional arrangements, only one of which may represent the bioactive pose [2]. Modeling approaches address this by generating ensembles of low-energy conformers for each ligand using systematic or stochastic conformational searches, ensuring that the pharmacophore captures plausible binding geometries [2].

Methodological Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structural information of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational modeling techniques [3]. The workflow begins with protein preparation, which involves evaluating residue protonation states, positioning hydrogen atoms (often absent in X-ray structures), and addressing missing residues or atoms [3]. The quality of the input protein structure directly influences the resulting pharmacophore model, making critical assessment of the structure an essential first step [3].

The subsequent ligand-binding site detection phase identifies regions of the protein structure where ligand binding occurs [3]. This can be achieved through manual analysis of areas with key residues suggested by experimental data or using bioinformatics tools that inspect the protein surface for potential binding sites based on evolutionary, geometric, energetic, or statistical properties [3]. Programs such as GRID and LUDI are commonly employed for this purpose—GRID uses different molecular probes to sample specific protein regions and identify energetically favorable interaction points, while LUDI predicts potential interaction sites using knowledge from distributions of non-bonded contacts in experimental structures [3].

Once the binding site is characterized, pharmacophore feature generation creates a map of interactions that defines the type and spatial arrangement of chemical features required for ligand binding [3]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, this process is more accurate, as the ligand's bioactive conformation directly guides the identification and spatial disposition of pharmacophore features corresponding to functional groups involved in target interactions [3]. The presence of the receptor also allows for incorporating spatial restrictions through exclusion volumes (XVOL), which represent forbidden areas that account for the shape and size of the binding pocket [3]. In the absence of a bound ligand, the modeling depends solely on the target structure, which is analyzed to detect all possible ligand interaction points, typically resulting in less accurate models that require manual refinement [3].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling derives pharmacophore models exclusively from a set of known active ligands, without requiring structural information about the biological target [3] [2]. This approach assumes that structurally diverse yet biologically active ligands share a common pharmacophoric pattern that can be extracted through computational alignment and feature mapping [2]. The common-hit approach exemplifies a core technique in this domain, involving the superposition of multiple active ligands to identify overlapping chemical features that represent the pharmacophore [2]. Alignment algorithms, such as those based on least-squares fitting of feature distances, position ligand conformers to maximize the coincidence of pharmacophoric points like hydrogen-bond donors, acceptors, and hydrophobic regions [2].

A significant advancement in ligand-based approaches is the development of quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPhAR) methods, which extend traditional qualitative pharmacophore models to quantitative predictions [5] [4]. QPhAR operates directly on pharmacophore features without requiring the underlying molecules, first finding a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples [4]. The input pharmacophores are then aligned to this merged-pharmacophore, and information regarding their relative positions is used as input for machine learning algorithms that derive quantitative relationships between pharmacophore features and biological activities [4]. This approach demonstrates particular value with small datasets of 15-20 training samples, making it viable for medicinal chemists, especially in lead optimization stages [4].

Dynamic and Consensus Approaches

Traditional structure-based methods often face limitations due to their reliance on static protein structures, potentially missing important interactions that occur in dynamic protein-ligand complexes [6]. To address this, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been integrated into pharmacophore modeling workflows to sample possible protein conformations and derive multiple pharmacophore models from initially static structures [6]. The hierarchical graph representation of pharmacophore models (HGPM) was developed to visualize numerous pharmacophore models from long MD trajectories, emphasizing their relationships and feature hierarchy [6]. This representation enables intuitive observation of multiple models in a single graph, facilitating the selection of pharmacophore sets for virtual screening campaigns [6].

Consensus approaches have also been developed to overcome the need to select a single "best" pharmacophore model. The "Common Hits Approach" (CHA) uses multiple 3D pharmacophore models derived from MD simulation, partitioning them according to feature composition for subsequent virtual screening runs [6]. A single final hit-list is obtained using consensus scoring to rank and combine screening results, enabling prioritization of virtual hits based on a set of MD-derived models [6]. More recently, probabilistic approaches for consensus scoring have been developed that are less sensitive to poor-performing models in the pool [6].

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Virtual screening represents one of the most significant applications of pharmacophore models in drug discovery [3]. As filters for screening large compound libraries, pharmacophores significantly reduce the computational resources and time required compared to more exhaustive methods like molecular docking [3]. Tools such as pharmit facilitate this process through web servers that enable users to search for small molecules based on structural and chemical similarity to a query molecule or pharmacophore [7]. Pharmit accepts various inputs, including PDB accession codes, receptor/ligand files, or externally generated pharmacophores from programs like MOE, LigBuilder, or LigandScout [7]. The search can incorporate shape constraints—using the ligand's surface as an inclusive constraint or the receptor's surface as an exclusive constraint—to refine results [7].

The virtual screening process typically incorporates additional hit reduction and feasibility screening options, including constraints on molecular weight, number of rotatable bonds, logP (lipophilicity), polar surface area, number of aromatic groups, and numbers of hydrogen bond acceptors and donors [7]. These filters help prioritize compounds with desirable drug-like properties, increasing the likelihood of identifying viable lead candidates [7]. Following screening, results can be sorted based on RMSD (for pharmacophore searches) or similarity scores (for shape searches), with minimization options available to assess the favorability of binding poses when a receptor structure is provided [7].

Case Study: Application to Human Glucokinase

A comprehensive example of advanced pharmacophore modeling comes from research on human glucokinase (hexokinase IV), where HGPM was applied to visualize and analyze pharmacophore information derived from MD simulations [6]. In this study, two crystal structures of human glucokinase in complex with activators (PDB IDs 1v4s and 4no7) were obtained from the RCSB PDB databank [6]. The protein-ligand complexes underwent preparation through Maestro software, which involved removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, and minimizing the structures [6]. CHARM-GUI was used for solvation and addition of ions [6].

MD simulations were carried out using Amber 16, with parameters for ligands generated by tleap using the general AMBER force field (GAFF) [6]. Each system was simulated for a total of 300 ns composed of 3 replicates of 100 ns with different initial velocities using Langevin dynamics at 303.15 K [6]. Structure-based pharmacophore models were then generated for each frame output from the MD simulations using LigandScout 4.4 Expert, supporting chemical feature types including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and other key pharmacophore elements [6]. The resulting hierarchical graph representation provided an intuitive visualization of all unique models and their relationships observed during the simulations, enabling more informed selection of 3D pharmacophore models for subsequent virtual screening runs [6].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Reagent/Software | Type/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Pharmacophore generation software | Structure-based and ligand-based model creation [6] [4] |

| Amber 16 | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Sampling protein-ligand conformational space [6] |

| GAFF (General AMBER Force Field) | Force field parameters for small molecules | MD simulations of ligands in complex with proteins [6] |

| Charmm-GUI | Web-based interface for simulation setup | Solvation and ion addition for protein complexes [6] |

| PHASE | Pharmacophore perception and QSAR tool | 3D pharmacophore fields and quantitative activity modeling [4] |

| pharmit | Web server for virtual screening | Pharmacophore-based database screening [7] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data | Source of protein-ligand complexes for structure-based modeling [3] [6] |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity database for drug-like molecules | Source of active and inactive compounds for model validation [6] [4] |

Machine Learning and Automated Optimization

Recent advances have introduced machine learning approaches to address the complexity and expert-dependent nature of traditional pharmacophore modeling [5]. Algorithms have been developed for the automated selection of features that drive pharmacophore model quality using structure-activity relationship (SAR) information extracted from validated QPhAR models [5]. When integrated into an end-to-end workflow, this enables a fully automated method that derives high-quality pharmacophores from a given input dataset [5].

In a case study on the hERG K+ channel using a dataset from Garg et al., QPhAR was applied to generate refined pharmacophores and compare them against baseline methods [5]. The baseline models used shared feature pharmacophore generation from the most active compounds in the training set, while QPhAR-based refined pharmacophores were extracted directly from the QPhAR model without additional data requirements [5]. Evaluation metrics specifically designed for virtual screening contexts—Fβ-score, FSpecificity-score, and FComposite-score—were employed, as traditional machine learning metrics like accuracy and precision do not adequately capture virtual screening objectives where the goal is maximizing true positives while reducing false positives [5]. Results demonstrated that QPhAR-based refined pharmacophores outperformed baseline pharmacophores on the FComposite-score, though performance depended on the quality of the underlying QPhAR models [5].

The pharmacophore concept has evolved significantly from its origins in early receptor theory to become an indispensable tool in modern computational drug discovery. The IUPAC definition—emphasizing the ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with biological targets—provides a foundational framework that continues to guide method development and application [1]. As demonstrated throughout this review, pharmacophore modeling offers a unique abstraction that captures essential molecular recognition patterns while accommodating structural diversity through scaffold hopping [3] [2].

Future developments in pharmacophore modeling are likely to focus on several key areas. Integration with machine learning approaches will continue to advance, potentially enabling fully automated workflows that analyze complex data patterns beyond human perception and present optimized solutions to researchers [5]. Enhanced dynamic representations that more accurately capture protein-ligand interaction dynamics through advanced sampling methods and multi-scale modeling will address current limitations of static structure-based approaches [6]. The development of standardized validation metrics specifically designed for pharmacophore model evaluation in virtual screening contexts will help address current challenges in model selection and quality assessment [5]. As these methodologies mature, pharmacophore approaches will remain essential tools for reducing the time and costs of drug discovery while addressing complex challenges in personalized medicine and health emergencies [3].

The concept of the pharmacophore, a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry and computer-aided drug design, represents the culmination of over a century of scientific thought. This whitepaper traces the historical evolution of the pharmacophore concept from its nascent beginnings in Paul Ehrlich's pioneering work on chemoreceptors to its formal definition and computational application by Lemont "Monty" Kier. Framed within a broader thesis on pharmacophore modeling basics, this document elucidates the key historical milestones, conceptual shifts, and methodological advancements that have shaped our current understanding of molecular recognition. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, this journey provides essential context for the sophisticated virtual screening and rational drug design protocols that accelerate contemporary therapeutic discovery.

In contemporary computer-aided drug design (CADD), a pharmacophore is universally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [3] [8]. This abstract model captures the essential three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—required for a molecule to elicit a biological effect [9] [10].

The evolution of this concept from a qualitative idea to a quantitative, computable model reflects broader trends in pharmacology and computational chemistry. Understanding this history is not merely an academic exercise; it provides a critical foundation for effectively applying pharmacophore methods in modern drug discovery projects, enabling scientists to better interpret model results and anticipate their limitations.

The Pioneering Era: Paul Ehrlich's Foundation

Although the term "pharmacophore" was not used in his writings, the conceptual foundation was unequivocally established by the German Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Our research clarifies that Ehrlich's 1898 paper originated the core concept, identifying peripheral chemical groups in molecules as responsible for binding and subsequent biological effects [11].

Ehrlich's revolutionary thinking introduced several key principles that would later become central to pharmacophore modeling:

- Receptor Theory: Ehrlich proposed that drugs exert their effects by binding to specific "chemoreceptors" on cells, conceptualizing this interaction with the famous "lock and key" metaphor [3].

- Molecular Features Dictate Activity: He postulated that specific molecular substructures, which he termed "toxophores" or "haptophores," were responsible for binding to receptors and generating biological responses [11].

- Therapeutic Index: Ehrlich's work on selective toxicity introduced the concept that optimal drugs should have high affinity for pathological targets while minimizing interactions with host tissues—a principle that remains fundamental in drug design today.

Historical analysis indicates that Ehrlich's contemporaries did use the term "pharmacophore" to describe the features of a molecule responsible for its biological activity, even as Ehrlich himself used alternative terminology [11]. This attribution to Ehrlich was later obscured in the literature by an erroneous citation in the 1960s, creating historical confusion that has only recently been resolved [11] [12].

The Conceptual Transition: Schueler's Bridge

The transition from Ehrlich's substance-based concept to the modern feature-based definition occurred through the work of F. W. Schueler in the 1960s. In his 1960 book, Schueler extended the pharmacophore concept beyond specific chemical groups to patterns of abstract features of a molecule that are ultimately responsible for biological effect [11].

This critical reformulation shifted the paradigm from:

- Concrete Chemical Groups → Abstract Molecular Features

- Structural Scaffolds → Spatial Arrangement

- Atom-Centric View → Interaction-Centric View

Schueler's work established the theoretical bridge between Ehrlich's early insights and the computational approaches that would follow, setting the stage for the modern IUPAC definition that guides current research [11].

The Modern Formalization: Monty Kier's Computational Revolution

The period from 1967 to 1971 marked the critical transformation of the pharmacophore from a theoretical concept to a practical tool for drug discovery. Lemont "Monty" Kier is credited with this formalization, developing the first computational methodologies for pharmacophore identification and application [12].

Kier's seminal contributions included:

- Receptor Mapping: Using molecular orbital calculations to determine preferred conformations of biologically active molecules and define their common pharmacophoric patterns [12].

- Spatial Arrangement Emphasis: Focusing on the three-dimensional arrangement of functional groups vital for biological activity, rather than specific chemical structures [12].

- Computational Implementation: Creating the first practical frameworks for using pharmacophores in drug design, moving from theoretical concept to applicable methodology.

Kier's key insight was that pharmacophores represent patterns of interaction necessary for biological activity rather than just structural functionalities, thus refining and operationalizing the concept for practical drug discovery [12]. His work established the pharmacophore as a central principle in the emerging field of computer-aided molecular design, enabling the development of virtual screening methodologies that would lead to significant therapeutic discoveries.

Methodological Evolution: From Theory to Application

The establishment of Kier's computational foundation catalyzed the development of two primary methodological approaches to pharmacophore modeling, each with distinct applications and workflows.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based approaches are employed when the 3D structure of the biological target is unknown but a set of active ligands is available [3] [10]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Compound Selection and Preparation: Curate a diverse set of known active compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ values) [13].

- Conformational Analysis: Generate multiple 3D conformers for each active compound to explore conformational space and identify potential bioactive conformations using techniques such as systematic search, Monte Carlo sampling, or molecular dynamics simulations [9].

- Molecular Alignment and Feature Identification: Superimpose the active compounds using flexible alignment techniques to identify common chemical features and their spatial arrangement [9]. Critical features include hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups [9] [3].

- Model Building and Validation: Construct the pharmacophore hypothesis by combining selected features with spatial constraints (distances, angles, tolerances). Validate model quality using statistical metrics like enrichment factor, ROC curves, and AUC values [9] [14] [13].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based approaches utilize the 3D structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [3] [14]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain and prepare the 3D protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting missing residues, assigning protonation states, and energy minimization [14] [13].

- Binding Site Analysis: Identify the ligand-binding site using computational tools such as GRID or LUDI, which analyze protein surface properties to detect potential interaction pockets [3].

- Interaction Point Mapping: Generate pharmacophoric features based on complementary regions in the binding site, representing potential hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and ionic interactions [3].

- Feature Selection and Model Generation: Select the most relevant interaction points and create the pharmacophore model, potentially including exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints [3] [14].

Quantitative Historical Impact Assessment

Table 1: Evolution of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches and Their Applications

| Time Period | Key Innovators | Conceptual Focus | Primary Methods | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898-1960 | Paul Ehrlich | Chemoreceptor theory, toxophores | Substance specificity analysis, structure-activity observations | Drug selectivity, chemotherapy |

| 1960-1967 | F.W. Schueler | Abstract feature definition | Theoretical framework development | Conceptual clarification |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont Kier | Spatial arrangement of functional groups | Molecular orbital calculations, receptor mapping | Rational drug design, conformational analysis |

| 1970s-1980s | Peter Gund, Yvonne Martin | Computational implementation | Active analog approach, 3D database searching | Virtual screening, lead identification |

| 1990s-Present | Multiple groups | Hybrid approaches, machine learning integration | Structure-based design, QSAR modeling, AI-assisted discovery | Multi-target drug design, polypharmacology |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Modern pharmacophore research relies on specialized software tools and databases that enable the implementation of methodological workflows.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Software | Discovery Studio, MOE, LigandScout | Comprehensive pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, model validation | Structure-based and ligand-based model development, high-throughput screening |

| Open-Source Tools | Pharmer, PharmaGist, ZINCPharmer | Pharmacophore alignment, feature identification, database screening | Academic research, proof-of-concept studies |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem | Source of compound structures and bioactivity data | Virtual screening libraries, training set compilation |

| Protein Data Resources | RCSB PDB, AlphaFold2 | Source of experimental and predicted protein structures | Structure-based pharmacophore generation |

| Validation Tools | DUDe Decoy Sets, ROC-AUC Analysis | Model quality assessment, performance evaluation | Pharmacophore model validation and optimization |

Contemporary Applications and Future Directions

The historical evolution from Ehrlich to Kier has enabled diverse contemporary applications of pharmacophore modeling in drug discovery:

Virtual Screening for Lead Discovery: Pharmacophore models efficiently scan large chemical libraries to identify compounds matching essential features, significantly reducing time and costs compared to high-throughput experimental screening [9] [3]. For example, a recent study identifying FGFR1 inhibitors screened 9,019 compounds using pharmacophore modeling, discovering three hit compounds with superior binding affinity [13].

Lead Optimization and Scaffold Hopping: Pharmacophore models guide structural modifications to enhance potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties while enabling identification of novel chemical scaffolds that maintain critical interactions [9] [13]. The FGFR1 study subsequently performed scaffold hopping to generate 5,355 derivatives with improved bioavailability and reduced toxicity [13].

Multi-Target Drug Design and Drug Repurposing: By identifying common interaction features across different targets, pharmacophore modeling facilitates the design of multi-target therapeutics and the repurposing of existing drugs for new indications [10].

Antibody-Based Biotherapeutic Discovery: Recently, pharmacophore approaches have been adapted for antibody discovery, with a novel method successfully recapitulating 98.6% of parental antibody:antigen complexes in a benchmark study, demonstrating significant potential for accelerating biotherapeutic development [15].

Current research addresses historical limitations including conformational flexibility, protein dynamics, and balancing model specificity with sensitivity [9]. Integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning represents the next frontier, promising enhanced predictive power and accelerated therapeutic discovery [10] [15].

The journey from Ehrlich's receptor theory to Kier's computational formalization represents a paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. What began as a qualitative concept of specific chemical groups essential for biological activity has evolved into a sophisticated, computable model of abstract molecular features and their spatial relationships. This historical evolution has transformed pharmacophore modeling from theoretical construct to indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid identification and optimization of therapeutic candidates across diverse disease areas. For contemporary researchers, understanding this historical context provides not only appreciation for scientific progress but also foundational knowledge essential for innovating the next generation of pharmacophore-based discovery methodologies.

In the realm of computer-aided drug design (CADD), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [16]. This abstract concept represents the essential molecular interaction capabilities shared by a group of active compounds, independent of their specific chemical scaffold [2]. Pharmacophore modeling serves as a foundational tool in rational drug discovery, enabling researchers to identify novel bioactive compounds by focusing on critical molecular recognition elements rather than structural backbone alone [3] [17].

The historical development of the pharmacophore concept traces back to Paul Ehrlich in the late 19th century, who first introduced the idea of "toxophores" as peripheral chemical groups responsible for biological effects [2]. The term was later refined by Frederick W. Schueler in 1960 and further developed by Lemont B. Kier between 1967-1971, evolving into the modern three-dimensional model recognized today [2]. This conceptual evolution has transformed pharmacophores from qualitative chemical analogies to quantitative, computational models essential for contemporary drug discovery pipelines [2].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Concepts and Definitions

| Concept | Definition | Significance in Drug Design |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore | Ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with a biological target [16] | Provides abstract pattern for molecular recognition independent of specific chemical structure |

| Pharmacophore Features | Specific chemical functionalities (HBD, HBA, hydrophobic, ionizable groups) that mediate interactions [3] | Enables scaffold hopping and identification of structurally diverse active compounds |

| 3D Pharmacophore | Spatial arrangement of pharmacophore features in three-dimensional space [2] | Accounts for geometric requirements of molecular recognition beyond mere feature presence |

Core Pharmacophore Features

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) represent crucial polar interaction features in pharmacophore models that facilitate specific directional interactions with biological targets [3] [2]. HBD features typically involve atoms with polar hydrogen atoms (such as O-H or N-H groups) that can donate a hydrogen bond to complementary acceptor sites on the target protein [18]. Conversely, HBA features comprise atoms with lone electron pairs (such as oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur) that can accept hydrogen bonds from donor groups on the protein [18].

The geometric representation of these features in computational models incorporates specific tolerance parameters to account for structural flexibility. Hydrogen bonding interactions at sp² hybridized heavy atoms are typically represented as cones with cutoff apexes, with default angle ranges of approximately 50 degrees [19]. For flexible hydrogen-bond interactions at sp³ hybridized heavy atoms, a torus representation is employed with default angle ranges of precisely 34 degrees [19]. These features are typically modeled with distance tolerances of ±1.0–1.5 Å and angular deviations of approximately ±30° for directed interactions [2]. This geometric flexibility acknowledges the dynamic nature of molecular interactions while maintaining the essential directional character of hydrogen bonding.

Hydrophobic Areas

Hydrophobic features in pharmacophore models represent molecular regions that engage in non-polar van der Waals interactions and desolvation effects with complementary hydrophobic pockets on biological targets [2]. These features typically encompass aliphatic hydrocarbon chains, aromatic ring systems, and other non-polar molecular regions that preferentially interact with lipid environments rather than aqueous solutions [18].

In computational representations, hydrophobic areas are modeled as spherical centroids or volumes with typical radii of 4-6 Å, capturing the spatial extent of non-polar interaction sites [2]. These features promote binding affinity through the hydrophobic effect, where burial of non-polar surfaces from aqueous solvent lowers the overall free energy of binding [2]. The optimal lipophilicity for these features, as quantified by logP values of approximately 2-5, balances hydrophobic driving forces with sufficient aqueous solubility for biological distribution [2]. Pharmacophore models may implement varying handling of hydrophobic features, with lower hydrophobicity thresholds resulting in more restrictive matching criteria during virtual screening [19].

Ionizable Groups

Ionizable groups constitute essential electronic features that introduce charged character into pharmacophore models, enabling strong electrostatic interactions with complementary charged residues on biological targets [3]. These features are categorized as positive ionizable (PI) groups, typically comprising basic functionalities like protonated amines, and negative ionizable (NI) groups, generally comprising acidic functionalities like carboxylates [2].

The modeling of ionizable features incorporates protonation states at physiological pH (approximately 7.4), with basic groups possessing pKa values of 7-10 remaining protonated (positively charged), while acidic groups with pKa values of 3-5 remain deprotonated (negatively charged) [2]. Partial charge distributions, often calculated via quantum mechanical methods with thresholds of |q| > 0.2 e (electron charge units), further refine these features by quantifying electron density for interaction mapping [2]. These charged groups facilitate strong salt bridge formations and ionic hydrogen bonds that significantly contribute to binding affinity and specificity [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Core Pharmacophore Features

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Tolerance Parameters | Electronic Properties | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBD/HBA | Cones (sp²), Torus (sp³) [19] | Distance: ±1.0–1.5 Å, Angles: ±30° [2] | Directional interactions with specific angle ranges: 50° (sp²), 34° (sp³) [19] | ||

| Hydrophobic | Spherical centroids/volumes [2] | Radius: 4-6 Å [2] | Optimal logP: 2-5 for membrane permeability [2] | ||

| Ionizable | Charged spheres with directionality [2] | pKa ranges: 7-10 (PI), 3-5 (NI) [2] | Partial charge thresholds: | q | > 0.2 e [2] |

Additional Features and Volume Constraints

Beyond the core features, comprehensive pharmacophore models may incorporate additional elements to enhance specificity. Aromatic features capture the characteristic planar geometry of aryl rings that enable π-π stacking and cation-π interactions with complementary protein residues [19]. Metal-coordinating groups represent specific atoms with lone electron pairs capable of forming coordination bonds with metal ions in metalloprotein active sites [3].

Critical to structure-based pharmacophore models are exclusion volumes (XVOL), which represent forbidden regions in space that account for steric clashes with the target protein [3]. These volumes are typically represented as spheres that define regions where ligand atoms cannot occupy without incurring significant energetic penalties [2]. The incorporation of exclusion volumes dramatically increases model selectivity by eliminating compounds with inappropriate steric bulk that would clash with binding site residues [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The structure-based approach to pharmacophore modeling leverages three-dimensional structural information of biological targets, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [3] [20]. The fundamental premise of this methodology involves analyzing complementary interaction features within the target's binding site to generate pharmacophore hypotheses that represent optimal interaction patterns for ligand binding [3].

Diagram 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

The protocol for structure-based pharmacophore modeling involves these critical steps:

Protein Structure Preparation: The initial stage involves critical evaluation and preparation of the target structure, including addition of hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures), determination of residue protonation states, correction of missing atoms/residues, and validation of stereochemical and energetic parameters [3]. This ensures the biological and chemical relevance of the input structure.

Ligand-Binding Site Detection: Identification of the binding cavity using computational tools such as GRID (generating molecular interaction fields) or LUDI (using geometric rules and non-bonded contact distributions) [3]. Alternatively, manual identification based on co-crystallized ligands or site-directed mutagenesis data may be employed [3].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation: Analysis of the binding site to identify potential interaction points complementary to ligand functionalities [3]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, features are derived directly from the interaction pattern observed in the bioactive conformation [3].

Feature Selection and Model Assembly: Selection of the most relevant features from the initially generated set based on conservation in multiple structures, energetic contributions to binding, or functional significance from sequence analysis [3]. Exclusion volumes are added to represent steric restrictions from the binding site shape [3].

A representative application of this methodology was demonstrated in the identification of natural XIAP inhibitors for cancer therapy [14]. Researchers generated a structure-based pharmacophore model from the XIAP protein complex (PDB: 5OQW) with a known antagonist, resulting in a model containing 14 chemical features: four hydrophobic regions, one positive ionizable feature, three H-bond acceptors, five H-bond donors, and 15 exclusion volumes [14]. The model was subsequently validated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, achieving an area under curve (AUC) value of 0.98 and an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, demonstrating excellent predictive capability [14].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When three-dimensional structural information of the biological target is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provides a powerful alternative approach. This methodology derives pharmacophore hypotheses solely from a set of known active ligands, operating under the fundamental assumption that structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activities share common molecular interaction features [3] [18].

Diagram 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

The experimental protocol for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling involves:

Compound Selection and Conformational Analysis: Collection of structurally diverse active compounds with confirmed biological activity, followed by comprehensive conformational sampling to generate ensembles of low-energy conformers (typically ~250 conformers per compound) using systematic or stochastic methods [2] [18].

Molecular Superposition and Alignment: Spatial alignment of compound conformations using point-based methods (minimizing Euclidean distances between atoms or chemical features) or property-based techniques (maximizing overlap of molecular interaction fields) [18]. This represents the core "common-hit" approach where molecules are superimposed to identify overlapping chemical features [2].

Pharmacophore Feature Extraction: Identification of conserved molecular features across the aligned compound set, focusing on hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, ionizable groups, and aromatic systems [18]. The algorithm determines the optimal spatial arrangement of these features that is common to active compounds but absent in inactive molecules.

Hypothesis Generation and Refinement: Construction of pharmacophore hypotheses using algorithms such as HipHop (qualitative) or HypoGen (quantitative, incorporating activity data) [18]. Models are refined by eliminating features common to inactive compounds and optimizing predictive capability against experimental activity values [18].

The ligand-based approach must adequately address the critical challenge of conformational flexibility, as ligands typically possess rotatable bonds enabling multiple three-dimensional arrangements, only one of which may represent the bioactive conformation [2]. Advanced software tools implement various strategies to sample conformational space, including systematic rotational searches, molecular dynamics, and random sampling of rotatable bonds, often using reference geometries of rigid active compounds (active analog approach) to limit computational complexity [18].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [16] [14] | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Advanced molecular design; generates pharmacophore features from protein-ligand complexes; virtual screening filters [16] [14] | Complex-based pharmacophore generation; Virtual screening |

| Catalyst/HipHop [18] | Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Identifies common 3D feature arrangements; qualitative activity prediction [18] | Ligand-based hypothesis generation without target structure |

| Catalyst/HypoGen [18] | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling | Incorporates experimental IC50 values and inactive compounds; generates predictive quantitative models [18] | 3D-QSAR studies; Activity prediction |

| Phase [16] [18] | Comprehensive pharmacophore modeling | Ligand- and structure-based approaches; virtual screening; QSAR modeling [16] [18] | Diverse applications including scaffold hopping |

| MOE [16] | Molecular modeling suite | Pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, QSAR analyses [16] | Integrated drug design platform |

| DISCO [18] | Ligand-based pharmacophore generation | Performs molecular alignment and feature extraction [18] | Early-stage pharmacophore development |

| GASP [18] | Pharmacophore generation | Uses genetic algorithm for molecular alignment [18] | Flexible molecule alignment |

Critical to successful pharmacophore modeling initiatives are comprehensive chemical and structural databases that provide essential input data:

Protein Data Bank (PDB): Primary repository for three-dimensional protein structures solved by X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM [3]. Provides structural templates for structure-based pharmacophore modeling.

ZINC Database: Curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds (>230 million compounds) in ready-to-dock 3D format, including specialized subsets like natural compound libraries [14]. Essential for virtual screening phases.

ChEMBL Database: Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties containing compound bioactivity data against molecular targets [14]. Valuable source of active compounds for ligand-based modeling.

DUDe (Database of Useful Decoys): Enhanced decoy sets used for pharmacophore model validation, containing compounds with similar physical properties but dissimilar chemical structures to actives [14]. Critical for rigorous model validation.

Applications in Drug Discovery

Pharmacophore modeling serves as a versatile tool with multiple applications throughout the drug discovery pipeline. In virtual screening, pharmacophore models function as sophisticated queries to efficiently search large chemical databases and identify novel hit compounds with desired bioactivity [3] [19]. Benchmark studies have demonstrated that pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) frequently outperforms docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in enrichment factors, with PBVS achieving higher hit rates across multiple target classes [21].

The technique enables scaffold hopping - identifying structurally diverse compounds sharing common pharmacophore features - by focusing on essential interaction patterns rather than specific molecular frameworks [3] [17]. This application is particularly valuable for intellectual property expansion and overcoming toxicity issues associated with original chemotypes.

In lead optimization, pharmacophore models guide structural modifications to enhance potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties [19] [17]. By highlighting critical interaction features versus auxiliary elements, models provide strategic insights for medicinal chemistry efforts. Additionally, pharmacophores find application in drug repurposing through target fishing, where known drugs are screened against pharmacophore models of new targets to identify novel therapeutic applications [16] [22].

The integration of pharmacophore modeling with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations represents a significant advancement, incorporating protein flexibility and explicit solvent effects into dynamic pharmacophore models [19]. This approach captures the time-dependent evolution of interaction patterns, providing more physiologically relevant models compared to static structures [19] [14].

Validation and Best Practices

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure pharmacophore model reliability and predictive capability. The validation process typically employs statistical metrics including sensitivity (ability to correctly identify active compounds), specificity (ability to correctly identify inactive compounds), and enrichment factors (fold-enrichment of actives in early retrieval ranks) [19].

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis provides a comprehensive validation approach, with the area under curve (AUC) value quantifying overall model performance [14]. AUC values approaching 1.0 indicate excellent discriminatory power, with values above 0.9 generally considered outstanding [14]. The early enrichment factor, particularly at 1% of the screened database (EF1%), is especially relevant for virtual screening applications where early recognition of actives is critical [14].

Best practices in pharmacophore modeling include:

- Using high-quality, critically evaluated input data (either protein structures or biologically confirmed ligand activities)

- Implementing appropriate conformational sampling strategies to account for ligand flexibility

- Applying feature tolerance parameters that balance model specificity with generalizability

- Utilizing decoy sets for rigorous validation before application to virtual screening

- Employing consensus approaches when possible to minimize false positives and false negatives

These methodologies collectively establish pharmacophore modeling as a powerful, versatile approach in modern structure-based drug design, enabling efficient exploration of chemical space while focusing on the essential determinants of molecular recognition.

Pharmacophores represent an abstract description of molecular interactions essential for biological activity, divorcing these features from their underlying chemical structures. This abstraction serves as a powerful foundation for scaffold hopping—the drug discovery strategy aimed at identifying structurally novel compounds with similar biological activity by modifying central core structures. By focusing exclusively on steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition rather than specific atoms or bonds, pharmacophore models enable medicinal chemists to transcend traditional structural similarity constraints. This guide explores the theoretical underpinnings of pharmacophore abstraction, details experimental methodologies for its application in scaffold hopping, and demonstrates how this approach facilitates the discovery of novel chemotypes with improved pharmacological properties, successfully bridging the gap between maintained efficacy and structural innovation.

The Pharmacophore Concept

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [23]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a specific molecule or a single functional group, but rather an abstract representation of the molecular interactions required for biological activity. Typical features included in pharmacophore models are hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, cations, and anions [23].

The power of this abstraction lies in its ability to describe molecular recognition events in terms of essential interaction patterns rather than specific atomic configurations. This allows structurally diverse compounds that share the same spatial arrangement of key features to be recognized as potentially having similar biological activity, even if their molecular backbones differ significantly.

Scaffold Hopping in Drug Discovery

Scaffold hopping, also known as lead hopping, represents a central strategy in modern drug discovery for identifying novel chemotypes with improved properties while maintaining biological activity [24]. The concept was formally introduced in 1999 by Schneider et al. as "a technique to identify isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones" [24]. The primary objective is to transition a known active compound into novel chemical space while preserving its ability to interact with the biological target, effectively balancing the conflicting demands of structural novelty and functional equivalence.

In practice, scaffold hopping has been classified into several categories based on the degree and nature of structural modification [24]:

- Heterocycle replacements: Swapping aromatic or aliphatic rings with different heterocyclic systems

- Ring opening or closure: Modifying ring systems by opening fused rings or closing open chains into rings

- Peptidomimetics: Replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties

- Topology-based hopping: More significant alterations to molecular topology and shape

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches Based on Structural Modification

| Category | Structural Change | Degree of Novelty | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterocycle Replacements | Swapping carbon and heteroatoms in ring systems | Low | Replacing phenyl with thiophene in antihistamines [24] |

| Ring Opening/Closure | Breaking or forming ring bonds | Medium | Morphine to Tramadol transformation [24] |

| Peptidomimetics | Replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties | Medium-High | Various protease inhibitors |

| Topology-Based Hopping | Significant alterations to molecular topology | High | Complete scaffold reorganization |

The abstract nature of pharmacophores makes them particularly well-suited for facilitating scaffold hopping, as they explicitly decouple interaction patterns from their structural implementations—a concept we will explore in detail throughout this guide.

The process of developing a pharmacophore model involves several stages of abstraction that systematically remove structural specifics while preserving interaction essentials [23]:

Training Set Selection: A structurally diverse set of molecules with known biological activities is selected, including both active and inactive compounds to define essential versus incidental features.

Conformational Analysis: Low-energy conformations are generated for each molecule, as the bioactive conformation must be considered rather than the lowest-energy state.

Molecular Superimposition: The low-energy conformations of active molecules are superimposed to identify common spatial arrangements of functional groups.

Feature Abstraction: The superimposed functional groups are transformed into abstract pharmacophore elements (e.g., a hydroxy group becomes a 'hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor' feature).

Model Validation: The pharmacophore hypothesis is validated against known biological activities to ensure it can discriminate between active and inactive compounds.

This abstraction process effectively transforms concrete molecular structures into spatial arrangements of chemical functionalities, creating a template that can be matched by diverse molecular architectures.

Overcoming the Similarity-Property Principle

The similarity-property principle states that structurally similar compounds tend to have similar properties and biological activities [24]. While generally valid, this principle presents a significant constraint for discovering truly novel chemotypes through traditional similarity-based approaches. Pharmacophore abstraction provides a mechanism to transcend this limitation by redefining "similarity" in terms of interaction capabilities rather than structural composition.

The abstraction enables what appears to be a violation of the similarity-property principle—structurally diverse compounds exhibiting similar biological activity—because it focuses on the interaction similarity with the biological target rather than structural similarity between compounds. A well-designed pharmacophore model captures the essential elements that must be present for a molecule to bind to its target, regardless of how those elements are structurally implemented.

Tolerance for Structural Variation

Pharmacophore models incorporate tolerance ranges for the spatial position and orientation of features, acknowledging that protein flexibility and ligand adjustment allow for some variation in exact positioning while maintaining biological activity [4]. This tolerance for spatial variation further enhances the ability to identify scaffold hops, as it allows for structural modifications that might slightly alter the positioning of key features while maintaining their essential spatial relationships.

The abstract representation also accommodates bioisosteric replacements—the substitution of atoms or groups with others that have similar biological properties—by focusing on the type of interaction (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contact) rather than the specific atoms involved. This enables the identification of functionally equivalent but structurally distinct molecular fragments that can implement the required pharmacophore features [25].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standard approach for using pharmacophore models to identify novel scaffolds through virtual screening:

Step 1: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Select a training set of 15-50 compounds with known biological activities, ensuring structural diversity and a range of potency values [5].

- Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each compound using conformational analysis software (e.g., iConfGen [4]).

- Identify common pharmacophore features shared by active compounds using model generation algorithms (e.g., Hypogen [4] or PHASE [4]).

- Validate the model using test set compounds and decoy molecules to ensure discriminatory power.

Step 2: Database Screening

- Prepare a database of compounds for screening, applying appropriate chemical filters for drug-likeness.

- Perform flexible 3D searching against the pharmacophore model using specialized software (e.g., Catalyst [4] or LigandScout [26]).

- Retrieve compounds that match the pharmacophore features within defined tolerance limits.

Step 3: Post-Screening Analysis

- Apply additional filters based on physicochemical properties, potential toxicophores, and synthetic accessibility.

- Perform molecular docking studies with the target protein (if structural information is available) to validate binding mode predictions.

- Select diverse hits representing different scaffold classes for experimental validation.

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Procure or synthesize selected hit compounds.

- Evaluate biological activity using appropriate assays (e.g., radioligand displacement assays for receptor targets [25]).

- Iteratively refine the pharmacophore model based on new activity data.

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR)

Recent advances have enabled the development of quantitative pharmacophore models that predict biological activity levels rather than simple active/inactive classifications. The QPhAR methodology represents a novel approach that operates directly on pharmacophore features without requiring the underlying molecular structures [4] [5]:

QPhAR Protocol:

- Generate a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples.

- Align input pharmacophores to the merged-pharmacophore.

- Extract positional information for each aligned pharmacophore relative to the merged-pharmacophore.

- Use this information as input to machine learning algorithms to derive quantitative relationships between pharmacophore features and biological activities.

- Validate the model using cross-validation techniques, with typical performance metrics of RMSE = 0.62 ± 0.18 across diverse datasets [4].

The QPhAR approach demonstrates particular robustness with small dataset sizes (15-20 training samples), making it especially valuable in early drug discovery stages where data may be limited [4].

Automated Pharmacophore Optimization

Machine learning approaches now enable automated optimization of pharmacophore models for enhanced scaffold-hopping capability [5]:

Diagram 1: Automated Pharmacophore Optimization Workflow

This automated workflow leverages SAR information extracted from validated QPhAR models to select features that drive pharmacophore model quality, outperforming traditional methods that rely on manual expert curation or shared feature pharmacophores from highly active compounds [5].

Case Studies and Experimental Data

Historic Example: Morphine to Tramadol

The transformation from morphine to tramadol represents one of the earliest and most instructive examples of scaffold hopping facilitated by pharmacophore conservation [24]:

Experimental Data:

- Morphine exhibits a rigid 'T'-shaped structure with three fused rings and potent analgesic activity (μ-opioid receptor agonist).

- Tramadol was designed through ring opening of three fused rings in morphine, resulting in a more flexible structure.

- 3D superposition using molecular alignment programs demonstrates conservation of key pharmacophore features: positively charged tertiary amine, aromatic ring, and hydroxyl group attached to phenyl ring (the methoxyl group in tramadol is demethylated by CYP2D6) [24].

Biological Outcomes:

- Tramadol maintains analgesic efficacy through μ-opioid receptor activation.

- Tramadol exhibits reduced potency (approximately one-tenth of morphine) but improved oral bioavailability and duration of action (up to 6 hours).

- The structural changes significantly reduce addictive potential and side effects (nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression) compared to morphine.

This case demonstrates how significant structural simplification through scaffold hopping can yield clinical advantages while maintaining the essential pharmacophore required for therapeutic activity.

Antihistamine Development Series

The evolution of antihistamines provides a compelling case study of progressive scaffold hopping with conserved pharmacophore features [24]:

Table 2: Scaffold Hopping in Antihistamine Development

| Compound | Structural Features | Pharmacological Properties | Scaffold Hop Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pheniramine | Two aromatic rings joined to one carbon atom, one positive charge center | Classical antihistamine for allergic conditions | Reference compound |

| Cyproheptadine | Rigidified structure with locked aromatic rings and introduced piperidine ring | Improved H1-receptor affinity; additional 5-HT2 serotonin receptor antagonism | Ring closure |

| Pizotifen | Isosteric replacement of phenyl ring with thiophene | Enhanced migraine prophylaxis activity | Heterocycle replacement |

| Azatadine | Replacement of phenyl ring with pyrimidine | Improved solubility while maintaining potency | Heterocycle replacement |

Experimental data from 3D superposition studies confirm that despite significant 2D structural differences, these compounds share conserved spatial positioning of the basic nitrogen and two aromatic rings—the essential pharmacophore for H1-receptor antagonism [24].

Novel Histamine H3 Receptor Ligands

A recent study demonstrated the application of scaffold hopping for designing novel histamine H3 receptor ligands [25]:

Methodology:

- Starting point: Previously identified H3R antagonists with submicromolar affinity.

- Scaffold hopping approach: Exhaustive fragmentation along single non-ring bonds followed by bioisosteric replacement using Spark software.

- Selection criteria: Shape matching, pharmacophore similarity, hydrophobicity, and electronic properties.

Results:

- Designed compound d2 exhibited binding affinity (Ki = 2.61 μM) to hH3R in radioligand displacement assays.

- Demethylated d2 derivative showed lower affinity (Ki = 12.53 μM), highlighting the importance of specific pharmacophore features.

- The newly designed compounds provided a novel scaffold for further optimization of H3R antagonists.

This case illustrates how scaffold hopping guided by pharmacophore features can successfully generate novel chemotypes with maintained biological activity, expanding structure-activity relationship (SAR) exploration.

RNA-Targeted Compound Library Design

The design of an RNA-focused compound library demonstrates the application of pharmacophore-based scaffold hopping for challenging targets [26]:

Methodology:

- Analysis of RNA-ligand complex structures (e.g., G-quadruplexes, riboswitches) from PDB.

- Development of pharmacophore models based on interaction patterns observed in crystal structures.

- Virtual screening using molecular docking against multiple RNA targets.

Key Findings:

- For RNA G-quadruplexes (PDB ID 5bjp): Pharmacophore model required two aromatic features for stacking interactions with nucleobases and hydrogen bond interactions with water molecules.

- For riboswitches (PDB ID 3e5e): Pharmacophore model included aromatic features for stacking, occupation of hydrophobic sub-pockets, and multiple hydrogen bond donors/acceptors.

- Library construction: 28,000 compounds targeting RNA splicing, riboswitches, and G-quadruplexes using structure-based pharmacophore approaches.

This application highlights how pharmacophore abstraction enables identification of diverse chemotypes targeting complex biomolecular structures that differ significantly from traditional protein targets.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Essential Software and Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Pharmacophore-Based Scaffold Hopping

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application in Scaffold Hopping | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [4] [26] | Pharmacophore model generation from structural and ligand data | Creation of target-specific pharmacophore models for virtual screening | Commercial |

| Schrödinger PHASE [4] | Pharmacophore perception and 3D-QSAR | Quantitative analysis of pharmacophore features contributing to activity | Commercial |

| BioVia Catalyst [4] | Hypogen algorithm for pharmacophore development | Generation of quantitative pharmacophore models from training compounds | Commercial |

| Spark [25] | Bioisosteric replacement and scaffold hopping | Identification of novel fragments maintaining pharmacophore features | Commercial |

| QPhAR [4] [5] | Quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship | Predicting biological activity of novel scaffolds based on pharmacophore matching | Academic |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [24] | Molecular modeling and alignment | 3D superposition and pharmacophore feature analysis | Commercial |

Experimental Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Pharmacophore-Guided Scaffold Hopping

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application in Validation | Source Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Targeted Compound Library [26] | 28,000 compounds; sub-libraries for splicing, riboswitches, G-quadruplexes | Validation of pharmacophore models for RNA-targeted scaffold hopping | Enamine |

| ChEMBL Datasets [4] | Curated bioactivity data for diverse targets | Training and validation datasets for QPhAR modeling | ChEMBL Database |

| [3H]-Nα-methylhistamine [25] | Radioligand for H3 receptor binding assays | Experimental validation of designed H3R ligands through displacement studies | Commercial Suppliers |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The abstract nature of pharmacophores provides a powerful framework for scaffold hopping by focusing on the essential elements of molecular recognition rather than specific structural implementations. This abstraction enables medicinal chemists to transcend the limitations of the similarity-property principle and explore novel chemical space while maintaining biological activity. The case studies and methodologies presented demonstrate the successful application of this approach across diverse target classes and therapeutic areas.

Future developments in pharmacophore-based scaffold hopping will likely focus on several key areas:

- Increased integration with machine learning for automated pharmacophore optimization and hit prioritization [5]

- Enhanced handling of protein flexibility to create more dynamic pharmacophore models that accommodate induced fit effects

- Tighter coupling with synthetic accessibility predictions to ensure designed scaffold hops are synthetically feasible

- Expansion to challenging target classes such as protein-protein interactions and RNA structures [26]

As these methodologies continue to mature, pharmacophore-based scaffold hopping will remain an essential strategy for overcoming the limitations of existing chemotypes and expanding the accessible chemical universe for drug discovery.

The quantitative frameworks now emerging, such as QPhAR, represent a significant advancement beyond traditional qualitative pharmacophore approaches, enabling not only identification of novel scaffolds but also prediction of their potency ranges [4] [5]. This integration of quantitative prediction with scaffold hopping capability provides a powerful platform for accelerating the discovery of structurally novel therapeutic agents with optimized pharmacological properties.

A pharmacophore is an abstract model defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [3]. This foundational concept in computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) shifts the focus from specific atoms and functional groups to the essential molecular interaction capabilities required for biological activity [19]. By representing these interactions as a set of features—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups—and their three-dimensional arrangement, the pharmacophore serves as a blueprint for molecular recognition [3]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to pharmacophore modeling, detailing its core principles, methodological approaches, and applications in modern drug design, framed within the context of ongoing research to enhance the accuracy and predictive power of these models.

The historical roots of the pharmacophore concept date back to Paul Ehrlich and the "Lock & Key" principle introduced by Emil Fisher in 1894, which proposed that a ligand and its receptor interact with specificity akin to a key fitting its lock [3]. The modern computational interpretation extends this principle by abstracting molecular structures into their fundamental, chemically important components. This abstraction allows researchers to identify novel active compounds that share critical interaction patterns despite having different molecular scaffolds, a process known as "scaffold hopping" [4] [3].

The primary pharmacophore features include [3] [19]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD): Represent the capacity to form directional hydrogen bonds.

- Hydrophobic Areas (H): Represent non-polar regions favoring van der Waals interactions.

- Positively and Negatively Ionizable Groups (PI/NI): Represent moieties that can become charged under physiological conditions.

- Aromatic Rings (AR): Represent regions capable of π-π stacking or cation-π interactions.

These features are represented in 3D space as geometric objects—points, vectors, spheres (to allow for tolerance radii), and planes—that together form a query model used for virtual screening [3] [27].

Methodological Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

The construction of a pharmacophore model generally follows one of two principal methodologies, depending on the available input data: structure-based or ligand-based modeling.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational models like AlphaFold2 [3].

The standard workflow involves:

- Protein Preparation: The 3D structure is prepared by correcting protonation states, adding hydrogen atoms, and ensuring overall structural quality and energetic soundness [3].

- Ligand-Binding Site Detection: The key region on the protein where ligands bind is identified. Tools like GRID or LUDI can programmatically analyze the protein surface to pinpoint potential binding sites based on energetic and geometric properties [3].

- Feature Generation: The binding site is analyzed to map potential interaction points (e.g., where a hydrogen bond donor from a ligand would be accommodated). If a protein-ligand complex is available, the features are derived directly from the observed interactions [3].

- Model Selection and Refinement: Initially, many features may be generated. The final model is refined by selecting only the features that are essential for bioactivity, potentially by removing those that do not contribute significantly to binding energy or are not conserved across multiple ligand complexes [3].

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank | Repository for experimental 3D protein structures [3] | Source of initial protein or protein-ligand complex structure |

| GRID | Generates molecular interaction fields in a binding site [3] | Identifies energetically favorable regions for specific pharmacophore features |

| LUDI | Predicts interaction sites using geometric rules and statistical data [3] | Detects potential ligand-binding sites and interaction points |

| LigandScout | Automatically generates pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes [6] | Feature generation and model creation from a single structure or MD simulation snapshots |

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling offers a powerful alternative. This method deduces the essential pharmacophore features by identifying common patterns among a set of known active ligands, under the assumption that compounds sharing a common biological activity will possess a similar 3D arrangement of key chemical features [3] [19].

The process involves:

- Conformational Analysis: Generating a representative set of low-energy conformations for each active ligand.

- Common Feature Identification: Using algorithms to perceive the 3D arrangement of pharmacophoric features common to all or most active molecules.