Overcoming Poor Metabolic Stability in Drug Discovery: Strategies, Assays, and Future Directions

Poor metabolic stability remains a major cause of failure in drug development, leading to unfavorable pharmacokinetics, low bioavailability, and rapid clearance.

Overcoming Poor Metabolic Stability in Drug Discovery: Strategies, Assays, and Future Directions

Abstract

Poor metabolic stability remains a major cause of failure in drug development, leading to unfavorable pharmacokinetics, low bioavailability, and rapid clearance. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating these challenges. It covers the foundational principles of drug metabolism, details the core in vitro assays—from liver microsomes to hepatocytes—used to assess metabolic stability, and presents practical strategies for lead optimization through structural modification. Furthermore, it addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls, explores advanced predictive models, including machine learning, and emphasizes the importance of cross-species and in vitro-in vivo correlation for successful candidate selection and translation to human outcomes.

Understanding Metabolic Stability: Why It's a Critical Gatekeeper in Drug Development

Defining Metabolic Stability and Its Impact on Pharmacokinetics

For researchers in drug development, metabolic stability is not just a biochemical concept but a critical determinant of a compound's success. It refers to a drug candidate's susceptibility to biotransformation by the body's metabolic enzymes, primarily in the liver [1] [2]. This property directly impacts key pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters, including half-life ((t_{1/2})), clearance, and oral bioavailability [1] [3]. A compound with poor metabolic stability is rapidly broken down, often failing to achieve and maintain the systemic exposure necessary for therapeutic efficacy [2]. This guide provides troubleshooting support for the in vitro assays that are foundational to optimizing metabolic stability early in the discovery process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is metabolic stability and why is it a primary concern in lead optimization? Metabolic stability measures how resistant a compound is to enzymatic breakdown. It is a primary concern because it dictates the duration and intensity of a drug's pharmacological action [1] [2]. A metabolically unstable compound will have a short half-life and high clearance, leading to low systemic exposure and poor bioavailability [3]. This often necessitates frequent or high dosing, which can inconvenience patients and increase the risk of side effects [2]. Optimizing stability during lead optimization is therefore crucial for selecting candidates with a higher probability of in vivo success.

2. Our lead compound shows high intrinsic clearance in liver microsomes. What are the first investigative steps? High intrinsic clearance indicates rapid metabolic degradation. The first step is to identify the soft spots—the specific parts of the molecule undergoing metabolism. This involves Metabolite Identification (MetID) studies [4]. Incubate your compound with liver microsomes (or hepatocytes) and use LC-MS/MS to identify the structures of the major metabolites. Understanding the chemical transformation (e.g., hydroxylation, dealkylation) provides direct clues for rational structural modification to block these vulnerable sites [4].

3. We observe a significant discrepancy between in vitro metabolic stability and in vivo clearance. What are the common causes? This is a frequent challenge in PK scaling. Common causes include:

- Ignoring Extrahepatic Metabolism: Liver-focused assays may miss metabolism in other organs like the intestine, lung, or kidney [5]. Consider running stability assays with subcellular fractions from these tissues.

- Overlooking Non-Microsomal Enzymes: Liver microsomes are rich in Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes but contain fewer Phase II enzymes. The contribution of cytosolic enzymes like aldehyde oxidase (AO) may be significant for your compound [5]. Confirmatory assays in liver cytosol or S9 fractions are recommended.

- Poor Prediction of Transport: In vitro systems may not fully replicate the complex interplay between drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein), which can greatly influence hepatic uptake and clearance in vivo [1].

4. When should we use hepatocytes over liver microsomes for stability assessment? The choice depends on the metabolic pathway of interest. Liver microsomes are ideal for a focused study on Phase I metabolism, particularly CYP450-mediated reactions [5]. Hepatocytes, being intact cells, contain a full complement of both Phase I and Phase II enzymes (e.g., UGTs, SULTs) and more closely mimic the physiological environment of the liver [5]. Use hepatocytes when you need a comprehensive view of a compound's metabolic fate or when microsomal data does not correlate well with in vivo observations.

5. How can we rapidly screen a large compound library for metabolic stability? Traditional LC-MS/MS methods can be a bottleneck for large libraries. Consider a high-throughput, single time-point substrate depletion assay in 96- or 384-well format, where the percent of parent compound remaining after a short incubation (e.g., 15-30 minutes) is measured [6]. This approach efficiently classifies compounds as stable or unstable for prioritization. Emerging technologies like the Metabolizing Enzyme Stability Assay Plate (MesaPlate) also offer a fluorescence-based method to quantify metabolic stability by tracking NADPH and oxygen depletion, which can offer higher throughput [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly High Compound Remaining | - Loss of enzyme activity due to improper storage/thawing.- Inadequate cofactor concentration. | - Confirm microsomes/hepatocytes are stored at ≤ -70°C and thawed on ice.- Verify fresh preparation of NADPH regenerating system. |

| High Variability Between Replicates | - Inconsistent protein concentration across wells.- Poor solubility of the test compound leading to precipitation. | - Pipette enzymes and cofactors carefully; pre-mix reagents where possible.- Ensure compound is soluble in incubation buffer; consider minimal, uniform DMSO concentration (<0.1-1%). |

| No Depletion in Microsomes, but Rapid Loss in Hepatocytes | - Metabolism is primarily driven by Phase II enzymes or cytosolic enzymes (e.g., AO). | - Follow up with assays in liver cytosol or S9 fractions to identify the involved pathway [5]. |

| Poor Correlation with In Vivo PK | - In vitro system misses key elements (e.g., transporters, extrahepatic metabolism). | - Perform reaction phenotyping to identify specific enzymes involved [4].- Investigate stability in extrahepatic tissue preparations [5]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Standard Liver Microsomal Stability Assay

This is the workhorse assay for initial metabolic stability screening [8] [6].

Detailed Methodology:

- Incubation System: The typical 100 µL incubation mixture contains:

- 0.5 - 1.0 mg/mL liver microsomal protein (rat, dog, human) [8] [6].

- 1.0 µM test compound (final concentration) [6].

- NADPH Regenerating System: 0.650 mM NADP+, 1.65 mM Glucose-6-phosphate, 1.65 mM MgCl₂, and 0.2 unit/mL Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [6].

- 100 mM Potassium Phosphate Buffer, pH 7.4 [6].

- Procedure:

- Pre-incubate the mixture (without NADPH) for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the NADPH regenerating system.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45 minutes), withdraw an aliquot and quench the reaction with a chilled organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) containing an internal standard.

- Centrifuge to precipitate proteins and analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to quantify the remaining parent compound [6].

- Data Analysis: The natural logarithm of the percent remaining is plotted against time. The slope of the linear phase is used to calculate the in vitro half-life ((t{1/2})) and intrinsic clearance ((CL{int})) using the following equations [8]:

- (t_{1/2} = \frac{0.693}{k}) where (k) is the elimination rate constant (-slope).

- (CL{int} = \frac{0.693}{t{1/2}} \times \frac{\text{mL incubation}}{\text{mg microsomal protein}})

Quantitative Comparison of Metabolic Stability Assays

The table below summarizes the applications and components of key in vitro systems.

| Assay System | Key Enzymes Covered | Primary Application | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes [5] | CYP450s, FMO, UGTs | Focused assessment of Phase I oxidative metabolism. | In vitro (t{1/2}), (CL{int}) |

| Liver S9 Fraction [5] | CYP450s, UGTs, SULTs, GSTs | Broader profile of both Phase I and Phase II metabolism. | In vitro (t{1/2}), (CL{int}) |

| Hepatocytes [5] | Full spectrum of Phase I and II enzymes | Most physiologically relevant system for overall hepatic clearance. | In vitro (t{1/2}), (CL{int}) |

| Liver Cytosol [5] | Aldehyde Oxidase (AO), GSTs, etc. | Identification of non-microsomal, cytosolic enzyme metabolism. | In vitro (t{1/2}), (CL{int}) |

Inter-Species Differences in Metabolic Stability

Data from a study on a PDE5 inhibitor candidate (NHPPC) highlights the importance of cross-species assessment [8].

| Species | % Remaining after 60 min | Intrinsic Clearance (mL/min/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | 42.8% | 0.0233 |

| Dog | 0.8% | 0.1204 |

| Human | 42.0% | 0.0214 |

Interpretation: In this case, the dog was a poor predictor of human metabolic stability, as it metabolized the compound much more rapidly. The rat model showed a clearance rate much closer to that of humans [8]. This underscores the need for careful species selection when extrapolating in vitro data to predict human PK.

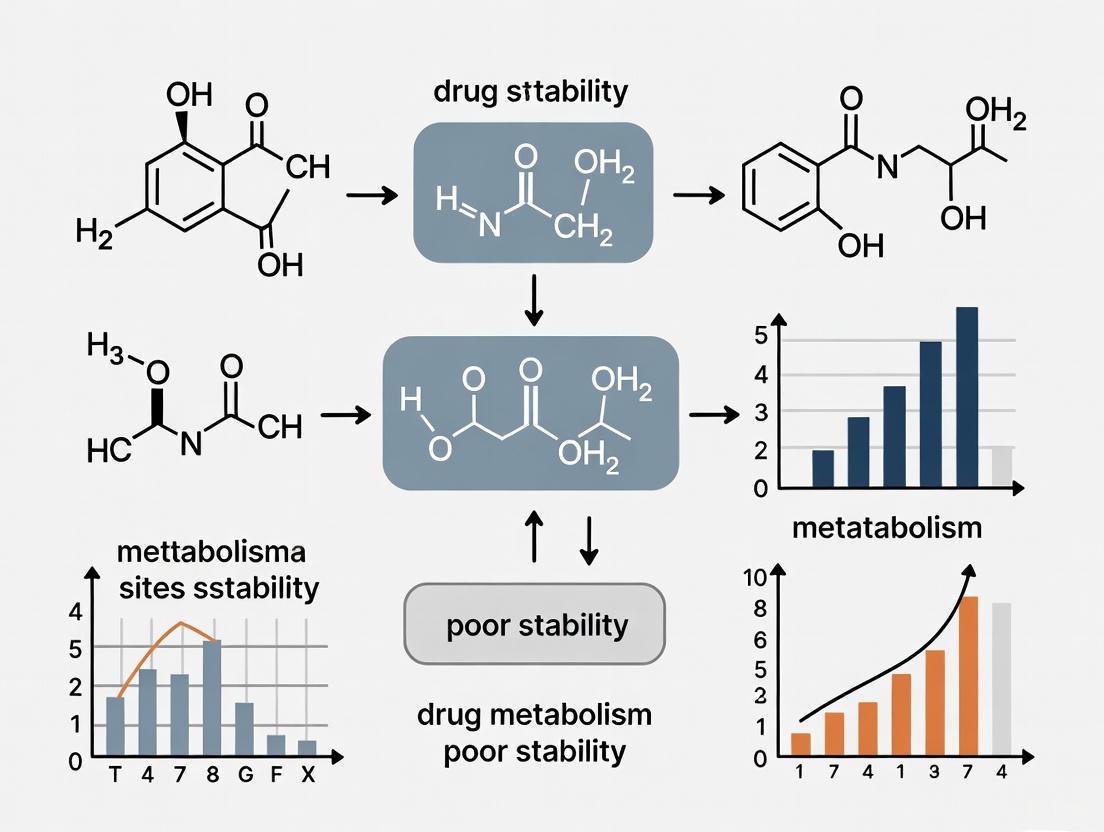

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Metabolic Stability Assay Selection Pathway

This diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting the appropriate metabolic stability assay based on research objectives.

In Vitro to In Vivo Prediction Workflow

This workflow charts the process of generating in vitro metabolic stability data and leveraging it to predict in vivo pharmacokinetic outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Metabolic Stability Assays |

|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes [8] [6] | Subcellular fractions containing membrane-bound enzymes (CYP450s, UGTs) for assessing Phase I metabolism. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes [5] | Intact liver cells containing a full suite of metabolic enzymes, providing the most physiologically relevant in vitro system. |

| NADPH Regenerating System [8] [6] | Provides a continuous supply of NADPH, the essential cofactor for CYP450-mediated oxidative reactions. |

| Potassium Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) [8] [6] | Maintains a physiologically relevant pH for the enzymatic reactions during incubation. |

| LC-MS/MS System [8] [4] | The gold-standard analytical platform for sensitive and specific quantification of parent compound depletion and metabolite identification. |

| Specific Chemical Inhibitors [4] | Used in reaction phenotyping to inhibit specific CYP450 enzymes (e.g., ketoconazole for CYP3A4) to identify metabolic pathways. |

FAQs: Understanding Metabolic Stability

What is metabolic stability and why is it a primary cause of clinical failure?

Metabolic stability refers to a drug candidate's susceptibility to biotransformation (breakdown) by the body's metabolic enzymes [2]. It is a critical determinant of a drug's pharmacokinetic profile, influencing how long a therapeutic remains active and at what concentration it reaches its target site [2] [1].

Poor metabolic stability is a major contributor to the high failure rate in clinical drug development. Analyses show that 40-50% of clinical failures are due to a lack of clinical efficacy, while 30% are due to unmanageable toxicity [9]. Both outcomes are directly linked to inadequate metabolic stability. A drug that is metabolized too quickly may not reach its target in sufficient concentrations to be effective, while a drug that forms reactive or toxic metabolites can cause serious safety issues [9] [2].

What are the key in vitro systems used to assess metabolic stability?

Researchers use several in vitro systems to predict a compound's metabolic fate. The table below summarizes the most common ones and their applications [5].

| In Vitro System | Components | Primary Metabolic Functions Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions rich in membrane-bound enzymes [5] | Phase I metabolism (e.g., Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, FMO) [5] |

| Liver S9 Fraction | Contains both microsomal and cytosolic components [5] | Phase I and some Phase II metabolism (e.g., CYP, UGT, SULT) [5] |

| Hepatocytes | Whole liver cells [5] | Full complement of hepatic oxidative, reductive, and conjugative enzymes; considered the most physiologically relevant system [10] [5] |

| Liver Cytosol | Cytoplasmic fraction of liver cells [5] | Specific Phase II pathways and cytosolic enzymes (e.g., Aldehyde Oxidase) [5] |

Why do compounds with excellent target potency often fail in the clinic due to metabolism?

A primary reason is the historical overemphasis on Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)—optimizing for high potency and specificity against the intended target—while underemphasizing Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) [9]. A molecule can be perfectly designed to hit its target but fail if it is rapidly cleared from the systemic circulation or if it accumulates in vital organs, leading to toxicity [9]. The modern approach, termed Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR), advocates for balancing potency with tissue exposure and selectivity to select candidates with a higher probability of clinical success [9].

What are "low-turnover" drugs and what special challenges do they present?

Low-turnover drugs are compounds that are metabolized very slowly [10]. A significant and growing proportion of drug candidates (up to 30% in some reports) fall into this category [10].

The core challenge is that standard metabolic stability assays have limited incubation times (e.g., ~1 hour for liver microsomes, ~4 hours for hepatocytes) due to the loss of enzyme activity [10]. For a slowly metabolized compound, there may be no detectable substrate depletion within this short window, making it impossible to calculate a reliable intrinsic clearance value [10]. This forces researchers to report a "less-than" value, which is not useful for differentiating between late-stage candidates or for predicting human pharmacokinetics with confidence [10].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Scenarios

Scenario 1: In Vitro to In Vivo Translation - Poor Correlation Between Assays and Animal Models

Problem: Your compound shows favorable metabolic stability in human liver microsomes, but in vivo animal studies reveal rapid clearance and poor bioavailability.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the Model System: Liver microsomes primarily contain phase I oxidative enzymes. If your compound is cleared via non-microsomal pathways (e.g., by Aldehyde Oxidase in the cytosol) or through Phase II conjugation, the microsomal data will be misleading [5]. Action: Move to a more complete system, such as hepatocytes, which contain the full suite of hepatic metabolic enzymes [10] [5].

- Account for Extrahepatic Metabolism: The liver is the primary site of metabolism, but other organs can contribute significantly. Action: Conduct stability assays using subcellular fractions from other tissues, such as the intestine, lung, or kidney, to identify non-hepatic clearance routes [5] [11].

- Challenge the Animal Model: There are known physiological and metabolic differences between animals and humans, leading to weak correlations in bioavailability [11]. Action: Use allometric scaling from animal data with caution. Supplement your data with advanced human-relevant models, such as hepatocyte coculture systems (e.g., HepatoPac) or fluidically-linked multi-organ chips (e.g., gut-liver systems) that better simulate human first-pass metabolism [10] [11].

Scenario 2: The "Low-Turnover" Compound - Unable to Measure Intrinsic Clearance

Problem: Your promising candidate shows negligible depletion in standard human liver microsome and hepatocyte assays, preventing you from ranking it against other compounds or predicting its human half-life.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Extend the Incubation Time: Standard hepatocyte suspension assays are limited to a few hours. Action: Employ specialized, longer-lived model systems:

- Hepatocyte Relay Method: The test compound is sequentially incubated with fresh hepatocytes over multiple days (e.g., 4 hours per day for up to 5 days), maintaining enzyme activity and allowing for measurable depletion of low-turnover drugs [10].

- Hepatocyte Coculture Systems (e.g., HepatoPac): These systems use hepatocytes cocultured with stromal cells to maintain metabolic function and stability for weeks, enabling accurate clearance measurements for even the most stable compounds [10].

- Shift to Metabolite Identification: If parent depletion is too slow to measure, focus on the products. Action: Use the extended incubation systems above to identify and quantify key metabolites. This reveals the primary clearance pathways and provides kinetic data (Vmax, Km) if authentic metabolite standards are available [10].

- Consider Alternative Clearance Pathways: The compound may be cleared predominantly by non-metabolic routes. Action: Investigate biliary and renal excretion pathways in relevant in vitro and in vivo models to build a complete picture of elimination [1].

Scenario 3: High Metabolic Lability - Rapid Clearance in All Systems

Problem: Your lead compound is rapidly degraded in all metabolic stability assays, indicating a very short projected half-life in humans.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify the Metabolic Soft Spot: Action: Incubate the compound with liver microsomes or hepatocytes and use LC-MS/MS to identify the major metabolites. The structure of these metabolites will reveal which part of the molecule is vulnerable (e.g., a specific ester, methyl group, or aromatic ring) [2].

- Employ Structural Modification: Action: Use medicinal chemistry to block the identified soft spot. Common strategies include:

- Introducing metabolically stable moieties (e.g., replacing a hydrogen with a fluorine or deuterium) [2].

- Blocking labile functional groups (e.g., cyclizing a chain, changing a substituent) [2].

- Reducing lipophilicity (cLogP) to potentially make the compound a less favorable substrate for metabolic enzymes [12].

- Explore a Prodrug Strategy: If the rapid metabolism is due to poor solubility or permeability, a prodrug may be the solution. Action: Design a prodrug—an inactive derivative that is rapidly converted to the active parent drug in the body. This can improve oral absorption and bypass first-pass metabolism, effectively enhancing metabolic stability for the active moiety [2].

Quantitative Data on Clinical Failure and Metabolic Stability Assays

Primary Reasons for Clinical Attrition of Drug Candidates

The following data summarizes why drug candidates fail in clinical trials, with issues related to metabolism being a primary contributor to efficacy and toxicity failures [9].

| Reason for Failure | Proportion of Failures |

|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40% - 50% |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | ~30% |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties (e.g., PK, solubility) | 10% - 15% |

| Lack of Commercial Needs / Poor Strategic Planning | ~10% |

Key Parameters and Desired Profiles in Metabolic Stability Assessment

When profiling compounds, researchers measure specific parameters to assess their viability. The table below outlines common metrics and their desired values for a promising oral drug candidate [9].

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter | Description | Preferred Profile for a Lead Candidate |

|---|---|---|

| Microsomal Stability (t₁/₂) | Time for parent drug concentration to reduce by half in liver microsomes | > 45-60 minutes [9] |

| Hepatocyte Stability | Measured intrinsic clearance from hepatocyte incubations | Low clearance value (enables differentiation for low-turnover drugs) [10] |

| Bioavailability (F) | Fraction of administered drug that reaches systemic circulation | > 30% [9] |

| Half-Life (t₁/₂) | Time for drug concentration in plasma to reduce by half | > 4-6 hours (to support once- or twice-daily dosing) [9] |

| Volume of Distribution (V) | Theoretical volume in which a drug is distributed | Context-dependent; influences half-life along with clearance |

Experimental Protocols for Key Metabolic Stability Assays

Protocol 1: Metabolic Stability Assay Using Liver Microsomes

Objective: To determine the in vitro intrinsic clearance of a test compound via Phase I metabolism.

Materials:

- Test compound

- Human or animal liver microsomes

- NADPH (cofactor)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂)

- Acetonitrile (for termination)

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-incubate liver microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL protein concentration) with test compound (e.g., 1 µM) in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) containing MgCl₂ (3 mM) for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Initiation: Start the reaction by adding NADPH (1 mM final concentration).

- Time Points: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes), remove an aliquot of the incubation mixture and quench it with a cold volume of acetonitrile to precipitate proteins and stop the reaction.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched samples, dilute the supernatant, and analyze the concentration of the parent compound remaining using LC-MS/MS.

- Data Calculation: Plot the natural logarithm of the parent compound's peak area versus time. The slope of the linear regression is the depletion rate constant (k). Intrinsic clearance (Cl₍ᵢₙₜ₎) is calculated as: Cl₍ᵢₙₜ₎ = k / (microsomal protein concentration).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Metabolic Stability Screening with Automated Assessment

Objective: To screen a large number of compounds for metabolic stability with high efficiency and automated data quality control [12].

Materials:

- All materials from Protocol 1

- Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer (UPLC/MS/MS)

- Automated liquid handler

- Custom software for data processing (e.g., Visual Basic program)

Method:

- Cassette Grouping: To increase throughput, compounds are pooled (cassetted) for analysis. A smart pooling strategy is used, grouping compounds based on their calculated Log D (c Log D₃.₀) values, as this parameter correlates well with chromatographic retention time. This minimizes the risk of peak co-elution and ion suppression [12].

- Discrete Incubation: Compounds are incubated discretely (individually) with liver microsomes and NADPH, as described in Protocol 1.

- Post-Incubation Pooling: After incubation, samples from different compounds (within the same c Log D group) are pooled into a single cassette for analysis.

- UPLC/MS/MS Analysis: The cassette samples are analyzed using a fast, high-resolution UPLC/MS/MS method.

- Automated QC and Re-analysis: A key feature of this workflow is automated data assessment. If the data for a compound in the cassette does not meet pre-defined quality criteria (e.g., poor peak shape, low signal), the system automatically triggers a re-analysis of the original discrete sample. This ensures data quality is maintained despite the high-throughput nature of the screen [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Metabolic Stability Research |

|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Gold-standard cell-based system containing a full complement of human metabolic enzymes for predicting in vivo clearance [10] [5]. |

| Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions used for high-throughput screening of Phase I metabolic lability, particularly Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism [5]. |

| NADPH | Essential cofactor required for the catalytic cycle of Cytochrome P450 enzymes; used to initiate metabolic reactions in vitro [7]. |

| MesaPlate | A fluorescence-based assay plate that quantifies metabolic stability by measuring NADPH and oxygen depletion rates, offering an alternative to LC-MS/MS [7]. |

| Superoxide Dismutase & Catalase | Antioxidant enzymes added to incubation systems to simplify reaction kinetics by eliminating reactive oxygen species, enabling accurate calculation of substrate depletion [7]. |

| 1-Aminobenzotriazole | A broad-spectrum, mechanism-based inhibitor of Cytochrome P450 enzymes, used in reaction phenotyping to confirm CYP-mediated metabolism [7]. |

Experimental Workflows and Conceptual Frameworks

Workflow for High-Throughput Metabolic Stability Screening

The following diagram illustrates an automated, quality-controlled workflow for efficiently screening large compound libraries.

The STAR Framework for Candidate Selection

This diagram outlines the Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) matrix, a modern approach for classifying drug candidates to improve clinical success rates [9].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary functional difference between Phase I and Phase II metabolism? Phase I reactions (e.g., oxidation, hydrolysis) primarily introduce or expose a functional group (-OH, -NH2, -COOH) to a molecule, often resulting in a modest increase in hydrophilicity and sometimes activating prodrugs or creating toxic intermediates [13] [14] [15]. Phase II reactions (conjugation) attach an endogenous, polar molecule (e.g., glucuronic acid, sulfate) to these groups, which typically significantly increases water solubility, inactivates the drug, and prepares it for excretion [13] [16] [14].

A common misconception is that Phase I must always precede Phase II. Is this accurate? No. While Phase I often provides a functional group for subsequent Phase II conjugation, many drugs bypass Phase I entirely if they already possess a suitable functional group (-OH, -NH2) and undergo direct Phase II metabolism [14] [15].

What does it mean if my compound shows rapid depletion in a human liver microsome (HLM) assay? A short half-life (t1/2) and high intrinsic clearance (CLint) in HLM assays indicate high metabolic instability [17] [18]. This often predicts low oral bioavailability and a short in vivo half-life, as the compound is extensively metabolized by the liver before it can reach its site of action [17].

How can I determine if a metabolite is pharmacologically active or toxic? Metabolites must be synthesized or isolated and then tested in relevant pharmacological and toxicological assays. In vitro studies using recombinant enzymes or specific enzyme inhibitors can help identify which enzyme system is responsible for producing the metabolite of interest [13] [19].

Why is metabolic stability a key parameter in early drug discovery? Compounds with poor metabolic stability are likely to have low bioavailability, short duration of action, and high inter-individual variability. Optimizing metabolic stability helps ensure adequate drug exposure for therapeutic efficacy and reduces the risk of failure in later, more costly development stages [18].

Our lab is new to oligonucleotide therapeutics. How does their metabolism differ from small molecules? Oligonucleotide metabolism differs significantly. They are primarily metabolized by nucleases (exo- and endo-nucleases) that cleave phosphodiester bonds, rather than the CYP450 system. Metabolites are typically chain-shortened sequences. Analysis requires specialized techniques like ion-pairing LC-MS to handle their high polarity and negative charge [20].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Challenge | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly High Metabolic Stability | Lack of Phase II metabolism in microsomal system; Nonspecific binding to labware [18]. | Supplement HLMs with alamethicin and UDPGA for glucuronidation. Use coated plates or include bovine serum albumin (BSA) [18]. |

| In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation Failure | In vitro system lacks extrahepatic metabolism; Ignores transporter effects (Phase III) [14] [19]. | Use hepatocytes over microsomes; Incorporate transporter inhibition studies. |

| Inability to Identify Metabolites | Low metabolite abundance; Poor ionization; Complex matrix interference [17]. | Use high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS); Apply modern data mining software; Compare samples from matrix blanks. |

| High Variability in Replicate Samples | Compound instability in matrix; Inconsistent protein precipitation; Inadequate incubation temperature control [18]. | Ensure immediate sample processing; Validate sample extraction recovery; Use pre-warmed incubators and buffers. |

| Unexpectedly Low Metabolite Formation | Cofactor depletion; Enzyme inhibition by test compound; Incorrect pH of incubation buffer [13]. | Use fresh/replenished cofactors; Test for enzyme inhibition; Verify buffer pH and composition. |

Core Enzyme Systems at a Glance

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Phase I and Phase II Drug Metabolizing Enzymes

| Phase | Enzyme Family | Core Reaction | Primary Site | Key Cofactor(s) | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Cytochrome P450 (CYP) [14] | Oxidation, Reduction | Liver (ER) | NADPH, O2 | Introduces polar groups, can activate prodrugs or create reactive metabolites [13] [14]. |

| Phase I | Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase (FMO) [18] | Oxidation | Liver (ER) | NADPH, O2 | Oxidizes nucleophilic heteroatoms (N, S, P). |

| Phase II | UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) [16] [14] | Glucuronidation | Liver, GI, Kidney | UDPGA | Major conjugation pathway; significantly increases hydrophilicity and targets compounds for biliary or renal excretion [13] [16]. |

| Phase II | Sulfotransferases (SULTs) [16] | Sulfation | Liver, GI, Platelets | PAPS | High-affinity, low-capacity conjugation; can be overwhelmed, leading to shunt to other pathways. |

| Phase II | Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) [13] [16] | Glutathione Conjugation | Liver, Kidney | Glutathione (GSH) | Crucial detoxification of electrophilic compounds; protects against oxidative stress [13]. |

| Phase II | N-Acetyltransferases (NATs) [16] [14] | Acetylation | Liver, RBCs | Acetyl-CoA | Subject to genetic polymorphism (fast vs. slow acetylators), impacting drug toxicity and efficacy [14]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Metabolic Stability Parameters from a Model Study on Violacein [17]

| System | Half-life (t1/2, min) | In Vitro CLint (µL/min/mg) | In Vivo CLint (mL/min/kg) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat Liver Microsomes (RLMs) | 36 | 38.4 | 93.7 | Rapid elimination; low stability in this species. |

| Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLMs) | 81 | 17.0 | 67.0 | Moderate stability. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) | 216 | 6.4 | 6.6 | Slowest elimination; highest stability, favorable for human dosing. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Metabolic Stability Assay in Liver Microsomes

This protocol is used to determine the in vitro half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) of a new chemical entity, assessing its susceptibility to Phase I and combined Phase I/II metabolism [18].

1. Principle The test compound is incubated with liver microsomes (human or animal) in the presence of cofactors. The depletion of the parent compound over time is monitored using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The rate of disappearance is used to calculate metabolic stability parameters [17] [18].

2. Materials and Reagents Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Stability Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pooled Human/Rat/Mouse Liver Microsomes | Source of drug-metabolizing enzymes (CYPs, UGTs). |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Provides a constant supply of NADPH, essential for CYP450-mediated Phase I oxidation [13]. |

| UDPGA (Uridine 5'-diphosphoglucuronic acid) | Cofactor for UGT-mediated glucuronidation (Phase II) [18]. |

| Alamethicin | Pore-forming peptide that permeabilizes microsomal membranes, allowing UDPGA access to the active site of UGT enzymes [18]. |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl2) | Cofactor for various enzymatic reactions. |

| Potassium Phosphate Buffer | Provides a stable physiological pH for the incubation. |

| LC-MS/MS System with Autosampler | For quantitative analysis of parent compound depletion. |

3. Procedure

- Preparation:

- Prepare a 1 mg/mL stock solution of the test compound in an appropriate solvent (e.g., DMSO).

- Thaw microsomes on ice and prepare all cofactor solutions in ice-cold potassium phosphate buffer.

- Incubation Setup (Two Conditions):

- Condition A (Phase I only): Microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) + NADPH Regenerating System + Test Compound (1 µM).

- Condition B (Phase I + II): Microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) + Alamethicin (25 µg/mL) → pre-incubate on ice for 15 minutes. Then add NADPH Regenerating System + UDPGA (2-5 mM) + Test Compound (1 µM) [18].

- Initiation and Time Points:

- Pre-warm the incubation mixtures at 37°C for 5 minutes.

- Start the reaction by adding the NADPH Regenerating System (for Condition A) or the test compound (for Condition B).

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes), withdraw an aliquot and quench the reaction with an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard.

- Sample Analysis:

- Centrifuge the quenched samples to precipitate proteins.

- Analyze the supernatant by LC-MS/MS to measure the peak area of the parent compound at each time point.

4. Data Analysis

- Plot the natural logarithm (ln) of the parent compound's remaining percentage against time.

- The slope of the linear regression (k) is the elimination rate constant.

- Calculate the in vitro half-life: t1/2 = 0.693 / k.

- Calculate intrinsic clearance: CLint, in vitro = k / [microsomal protein concentration].

Experimental Workflow and Metabolic Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of the metabolic pathway and the experimental workflow for the stability assay.

Diagram 1: Drug Metabolism and Excretion Pathway

Diagram 2: Metabolic Stability Assay Workflow

FAQs: Understanding the Fundamentals

What is the first-pass effect, and why is it critical for oral drug development? The first-pass effect (also known as first-pass metabolism or presystemic metabolism) is a phenomenon where a drug undergoes metabolic processing at a specific location in the body, leading to a reduction in the concentration of the active drug before it reaches the systemic circulation or its site of action [21] [22]. This effect is most prominent for orally administered drugs, as the liver is the primary site of this metabolism. After absorption from the digestive system, a drug enters the hepatic portal system and is carried via the portal vein to the liver, where it can be extensively metabolized before it is distributed to the rest of the body [21]. For drugs with high first-pass extraction, this can drastically reduce their oral bioavailability, meaning only a small fraction of the administered dose reaches the bloodstream to exert its therapeutic effect [21].

Which organs and enzymes are primarily responsible for first-pass metabolism? While the liver is the major site of first-pass metabolism due to its high concentration of metabolizing enzymes, extraction can also occur in other locations, including the gut wall, lungs, and vasculature [21] [22]. The four primary systems affecting the first-pass effect are:

- Enzymes of the gastrointestinal lumen

- Gastrointestinal wall enzymes

- Bacterial enzymes

- Hepatic enzymes [21]

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme family, particularly CYP3A4, plays a crucial role in the first-pass metabolism of many drugs, significantly impacting their bioavailability [21] [23]. Importantly, significant levels of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 are also present in the intestinal brush border, contributing to pre-systemic metabolism before the drug even reaches the liver [23].

How do metabolic stability and clearance relate to the first-pass effect? Metabolic stability refers to a compound's susceptibility to biotransformation and is a key determinant of its pharmacokinetic profile, including bioavailability and half-life [1] [2]. A drug with low metabolic stability is rapidly broken down, which often correlates with a high hepatic extraction ratio and significant first-pass effect [2]. Conversely, designing drugs with low clearance (high metabolic stability) is a common goal to prolong half-life and reduce dosing frequency [24]. However, accurately predicting human clearance for low-clearance compounds presents technical challenges, as they may show minimal turnover in standard in vitro assays, leading to overestimation of human clearance and half-life [24].

What is the clinical significance of the first-pass effect for patient dosing? Drugs that undergo considerable first-pass metabolism, such as morphine, propranolol, and nitroglycerin, often require much larger oral doses compared to their intravenous dosages to achieve a similar therapeutic effect [21] [22]. This can lead to complex dosing regimens and high inter-patient variability in drug response, as the extent of first-pass metabolism can be influenced by individual differences in enzyme expression, genetics, age, disease state (particularly liver disease), and concurrent use of other medications that inhibit or induce metabolizing enzymes [21] [23] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Poor Oral Bioavailability Due to High First-Pass Metabolism

Problem: Your drug candidate shows excellent in vitro potency but has unacceptably low oral bioavailability in preclinical models, suspected to be due to extensive first-pass metabolism.

Investigation and Diagnosis:

Confirm the Site of Metabolism: Determine if metabolism occurs in the gut wall, the liver, or both.

- Method: Conduct comparative in vitro assays using human liver microsomes, human intestinal microsomes, and suspended hepatocytes from both liver and intestine [21] [24]. The hepatocyte relay method can be particularly useful for low-clearance compounds [24].

- Interpretation: Significant metabolism in intestinal microsomes points to a gut wall component, while metabolism primarily in liver preparations indicates hepatic first-pass.

Identify the Enzymes Involved:

- Method: Perform reaction phenotyping using specific chemical inhibitors or antibodies against individual CYP enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6) or recombinant human enzymes [23] [24].

- Interpretation: If CYP3A4 is identified as the primary enzyme, you can anticipate potential drug-drug interactions and variability [23].

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies:

Employ a Prodrug Strategy: Design a prodrug that is resistant to first-pass metabolism but converts to the active parent drug in the systemic circulation. This can dramatically improve bioavailability [21] [2].

Modify the Administration Route: Bypass the first-pass effect entirely by using alternative routes of administration.

- Parenteral (IV, IM): Achieves 100% bioavailability [25].

- Sublingual/Buccal: Allows direct absorption into systemic circulation, as used for nitroglycerin [21] [22].

- Rectal: Partially bypasses first-pass metabolism [21].

- Transdermal/Inhalational: Delivers drug directly to the systemic circulation [21].

Utilize Enzyme Inhibition: Co-administer a low dose of a metabolic enzyme inhibitor. A clinical example is the combination of dextromethorphan with quinidine, where quinidine inhibits CYP2D6-mediated metabolism of dextromethorphan, thereby increasing its systemic exposure [22].

Optimize Chemical Structure: Use structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to modify the molecular structure, making it less susceptible to metabolic degradation. This can involve altering functional groups or incorporating metabolically stable moieties [26] [2].

Challenge: Accurately Predicting Low Human Clearance

Problem: Your compound shows minimal turnover in standard metabolic stability assays, making it difficult to predict its human half-life and optimal dosing regimen.

Investigation and Diagnosis:

Use Advanced In Vitro Models: Standard human liver microsomal or hepatocyte assays have a lower limit of detection for intrinsic clearance (CL~int~) [24]. To address this:

- Method: Implement the Hepatocyte Relay Method. This involves transferring the supernatant of a test compound incubation after several hours to freshly thawed hepatocytes, repeating this process to achieve a cumulative incubation time of 20 hours or more [24].

- Interpretation: This method extends the measurable range of CL~int~ and has shown good correlation with in vivo intrinsic clearance in humans and preclinical species [24].

Apply Time-Dependent Modeling: For very low-clearance compounds, data from prolonged incubations can be fitted to biphasic kinetic models to account for potential loss of enzyme activity over time, providing more accurate clearance estimates [24].

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies:

- Increase Assay Sensitivity: Increase hepatocyte density in the incubation (e.g., from 0.5 million cells/mL to 1.0 million cells/mL) to effectively lower the limit of CL~int~ measurement [24].

- Leverage Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: Use in vitro clearance data from sensitive assays to build PBPK models that can simulate and predict human pharmacokinetics, including half-life and bioavailability, even for low-clearance compounds [21] [26].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol: Hepatocyte Relay Assay for Low-Clearance Compounds

Purpose: To accurately determine the intrinsic clearance and identify metabolites for compounds with low metabolic turnover [24].

Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the sequential process of the hepatocyte relay assay.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes: Pooled from multiple donors for consistency [24].

- Incubation Media: Williams' Medium E or similar, supplemented with necessary cofactors.

- NADPH Regenerating System: Provides essential cofactor for CYP450 enzyme activity.

- Stopping Solution: Acetonitrile or methanol with internal standard to terminate the reaction.

- LC-MS/MS System: For quantitative analysis of parent drug and metabolite identification [24].

Procedure:

- Initial Incubation: Thaw hepatocytes and incubate with the test compound (1 µM) at a density of 0.5-1.0 million cells/mL for 4 hours at 37°C.

- First Relay: Centrifuge the incubation mixture. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh vial containing newly thawed, viable hepatocytes. Incubate for another 4 hours.

- Subsequent Relays: Repeat step 2 as needed (typically 3-5 relays) to achieve a cumulative incubation time (e.g., 20 hours).

- Sample Analysis: At each relay time point, collect samples, precipitate protein with stopping solution, and analyze by LC-MS/MS to monitor parent compound depletion and metabolite formation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate intrinsic clearance (CL~int~) from the parent depletion profile over the cumulative incubation time.

Protocol: Reaction Phenotyping using Chemical Inhibitors

Purpose: To identify the specific cytochrome P450 enzyme(s) responsible for metabolizing a drug candidate [23] [24].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) or cDNA-Expressed CYP Enzymes: Source of metabolic enzymes.

- Selective Chemical Inhibitors: e.g., Ketoconazole (CYP3A4), Quinidine (CYP2D6), Furafylline (CYP1A2) [23].

- NADPH Regenerating System.

- LC-MS/MS System.

Procedure:

- Set up Incubations: Incubate the test compound with HLM in the presence and absence of selective CYP inhibitors. Include control incubations without inhibitors and without NADPH.

- Run Parallel Incubations: Use cDNA-expressed individual CYP enzymes to directly confirm which enzyme can metabolize the drug.

- Quantify Metabolite Formation: Measure the rate of formation of the primary metabolite(s) in each incubation.

- Data Analysis: A significant reduction (>80%) in metabolite formation in the presence of a specific inhibitor (or with a specific cDNA-expressed CYP) identifies the major enzyme responsible for the metabolic pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and their applications in studying hepatic first-pass metabolism.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Gold-standard in vitro system for predicting hepatic clearance and metabolite profiling; maintains full complement of hepatic enzymes and transporters [24]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Subcellular fraction containing membrane-bound CYP enzymes; used for high-throughput metabolic stability screening and reaction phenotyping [1] [24]. |

| cDNA-Expressed CYP Enzymes | Recombinantly expressed individual human CYPs; used to definitively identify which specific enzyme metabolizes a drug candidate [24]. |

| Selective Chemical Inhibitors | Compounds that inhibit specific CYP enzymes (e.g., ketoconazole for CYP3A4); essential for reaction phenotyping studies [23] [24]. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Supplies NADPH, the essential cofactor for CYP450-mediated oxidative metabolism, in sustained in vitro incubations [24]. |

Key Data for Common Drugs and Strategies

The following table summarizes the first-pass effect and mitigation strategies for several well-known drugs.

| Drug | Therapeutic Class | First-Pass Effect & Bioavailability (F%) | Clinical Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol [21] [22] | Beta-blocker | Extensive first-pass metabolism; oral dose >> IV dose. | Administer high oral doses; monitor blood concentrations [22]. |

| Nitroglycerin [21] [22] | Anti-anginal | Extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism; very low F% if swallowed. | Administer sublingually to bypass first-pass effect [21] [22]. |

| Morphine [22] | Opioid analgesic | Considerable first-pass metabolism. | Use larger oral doses compared to parenteral routes. |

| Remdesivir [21] | Antiviral | Trapped in liver after oral administration; negligible systemic availability. | Administer via IV infusion to bypass first-pass metabolism entirely [21]. |

| Dextromethorphan [22] | Antitussive / Neurologic | Significant first-pass bioinactivation by CYP2D6. | Co-administer with quinidine (CYP2D6 inhibitor) to boost systemic levels [22]. |

| Saquinavir [23] | Protease Inhibitor | Substrate for CYP3A4 and P-gp; low oral bioavailability. | Co-administer with low-dose ritonavir (CYP3A4 inhibitor) to boost bioavailability. |

Visualizing the First-Pass Effect Journey

The diagram below illustrates the journey of an orally administered drug and the sites where first-pass metabolism can occur, significantly reducing the amount of active drug reaching the systemic circulation.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between Intrinsic Clearance (CLint) and Hepatic Clearance (CLH)?

Answer: CLint and CLH describe different aspects of drug elimination. Intrinsic Clearance (CLint) is a theoretical measure of the innate metabolic capacity of the liver enzymes for a drug, independent of external factors like blood flow or protein binding. It represents the volume of blood (containing a saturating drug concentration) that the liver can completely clear of drug per unit time [27].

In contrast, Hepatic Clearance (CLH) is the actual volume of blood cleared of the drug per unit time as it passes through the liver. It is the clinically observable clearance that determines systemic drug levels. CLH is a function of liver blood flow (QH), the fraction of unbound drug in the blood (fuB), and the intrinsic clearance (CLint), as described by the well-stirred model [28] [29]:

CLH = (QH • fuB • CLint) / (QH + fuB • CLint)

The relationship means that CLH for a drug can never exceed liver blood flow, whereas CLint can be much higher [27].

FAQ 2: Why do my in vitro predictions of human hepatic clearance systematically underpredict the in vivo observed values?

Answer: Systematic underprediction is a well-documented challenge in In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE). Several key factors contribute to this error [30]:

- Clearance-Dependent Error: The error is often not uniform. Studies have found that underprediction tends to be more pronounced for compounds with high in vivo intrinsic clearance. This is attributed to limitations in current in vitro systems, such as the loss of enzymatic activity over long incubations, permeability limitations, and the impact of the unstirred water layer [30].

- Limitations of In Vitro Systems: Simple in vitro systems like microsomes lack the full complement of enzymes and transporters present in intact hepatocytes. Even hepatocytes, which contain both Phase I and Phase II enzymes, may not fully replicate the in vivo liver environment over time [30] [31].

- Experimental Artifacts: Issues such as depletion of endogenous cofactors, non-specific binding to incubation apparatus, and inaccuracies in measuring the fraction of unbound drug can all lead to an underestimation of the true clearance [30] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- For Low Clearance Compounds: If compound disappearance is less than 20% over the assay duration, the result may be unreliable due to analytical variability. Consider using specialized assays with longer incubation times (e.g., co-culture systems with 72-hour incubations) to achieve greater sensitivity [31].

- For High Clearance Compounds: Be aware that predictions for high-extraction-ratio compounds are particularly prone to error, with in vitro models often failing to correctly identify them as such [30].

- Use Pooled Donors: To mitigate problems associated with inter-individual variability in human metabolism, use cryopreserved hepatocytes pooled from a minimum of three different donors [31].

- Adopt a Holistic Approach: Supplement traditional in vitro assays with more advanced models, such as microphysiological systems (organ-on-a-chip) that fluidically link gut and liver models, or use physiological-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to integrate various data sources for a more accurate prediction [11].

FAQ 3: When should I use microsomes versus hepatocytes for metabolic stability assays?

Answer: The choice depends on the stage of your drug discovery project and the metabolic information you need.

- Liver Microsomes: are subcellular fractions containing a high concentration of Phase I enzymes, particularly cytochrome P450s (CYPs). They are ideal for primary, high-throughput screening early in discovery to rapidly rank compounds for metabolic stability and identify CYP-mediated metabolism [30] [5].

- Hepatocytes: are intact liver cells containing the full complement of both Phase I and Phase II enzymes and transporters. They provide a more physiologically relevant model and are best used as a secondary screen on favorable compounds from the primary screen. Hepatocytes are essential for identifying non-CYP metabolism, transporter effects, and comprehensive metabolite profiling [31] [5].

Interpreting Discrepancies: If a compound is more stable in hepatocytes than in microsomes, it may indicate poor cellular permeability or that it is a substrate for efflux transporters. Conversely, if a compound is less stable in hepatocytes, it likely undergoes significant Phase II metabolism (e.g., glucuronidation, sulfation) [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Intrinsic Clearance Using Hepatocyte Stability Assay

This protocol measures the in vitro intrinsic clearance of a test compound by monitoring its disappearance in a suspension of cryopreserved hepatocytes [31].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Species-specific liver cells containing full complement of Phase I and Phase II metabolizing enzymes and transporters. |

| Incubation Buffer | Physiologically compatible medium (e.g., Krebs-Henseleit buffer) to maintain cell viability and function. |

| Test Compound | The drug candidate of interest, typically prepared as a stock solution in DMSO or buffer. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Organic solvent used to terminate the metabolic reaction at each time point and precipitate proteins. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Analytical platform for sensitive and specific quantification of the test compound in the presence of biological matrix. |

2. Methodology

- Thaw and Viability Check: Rapidly thaw cryopreserved hepatocytes (pooled from multiple donors is recommended) and assess cell viability using trypan blue exclusion. Proceed only if viability exceeds a certain threshold (e.g., 80%).

- Incubation Setup: Dilute the hepatocytes to a standard density (e.g., 1 million cells/mL) in incubation buffer pre-warmed to 37°C. Add the test compound to initiate the reaction. A typical final DMSO concentration should be ≤0.1-1%.

- Sample Collection: Immediately remove an aliquot (t=0) and quench it in an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile. Repeat this process at predetermined time points (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched samples to pellet precipitated proteins and cells. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine the peak area ratio of the test compound to an internal standard.

- Data Calculation:

- Plot the natural logarithm (ln) of the peak area ratio versus time.

- The gradient of the linear regression line is the elimination rate constant (k).

- Calculate the in vitro half-life:

t₁/₂ = 0.693 / k - Calculate the intrinsic clearance:

CLint (μL/min/million cells) = (V * 0.693) / t₁/₂where V is the incubation volume per million cells (μL/10⁶ cells) [31].

Protocol 2: In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) of Hepatic Clearance

This protocol describes how to scale the in vitro intrinsic clearance from hepatocytes to a predicted in vivo hepatic clearance using the well-stirred model [31].

1. Methodology

- Obtain In Vitro CLint: Determine the in vitro intrinsic clearance (CLint, vitro) in μL/min/million cells using the hepatocyte stability assay described in Protocol 1.

- Scale to In Vivo CLint: Convert the in vitro value to a predicted in vivo intrinsic clearance using species-specific scaling factors (SF), which are based on hepatocellularity (number of hepatocytes per gram of liver) and liver weight [31].

CLint, vivo (mL/min/kg) = [CLint, vitro (μL/min/million cells) * SF] / 100 - Apply the Well-Stirred Model: Input the scaled CLint, vivo into the well-stirred model equation to predict the in vivo hepatic clearance (CLH) [30] [31] [28]:

CLH = (QH • fuB • CLint, vivo) / (QH + fuB • CLint, vivo)Where:QH= Liver blood flow (species-specific, e.g., ~20.7 mL/min/kg for human [30]).fuB= Fraction of drug unbound in blood.CLint, vivo= Scaled in vivo intrinsic clearance.

2. Data Interpretation and Classification

Predicted clearance values can be categorized based on the hepatic extraction ratio (E = CLH / QH) [31]. The following table provides a generalized classification using physiologically based scaling factors, which often results in a significant underprediction trend as noted in the troubleshooting guide [30].

Table: Hepatic Clearance Classification and Prediction Accuracy

| Hepatic Extraction Ratio (E) | Clearance Category | Typical In Vivo CLH (Human) | % within 2-fold (Human Hepatocytes) [30] | % within 2-fold (Human Microsomes) [30] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E < 0.3 | Low | < ~6 mL/min/kg | 34.6% | Data not specified |

| 0.3 ≤ E ≤ 0.7 | Intermediate | ~6 - 14 mL/min/kg | 35.7% | Data not specified |

| E > 0.7 | High | > ~14 mL/min/kg | 11.1% | Data not specified |

Relationship Between Key Parameters

The parameters Intrinsic Clearance (CLint), Half-life (t₁/₂), and Hepatic Extraction (E) are fundamentally interconnected in determining a drug's pharmacokinetic profile.

Table: Interrelationship of Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Direct Determinants | Impact on Drug Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Clearance (CLint) | Innate ability of liver enzymes to clear drug without flow limitations. | Enzyme affinity (Km) and capacity (Vmax). | Governs potential for metabolism; high CLint suggests susceptibility to enzyme induction/inhibition. |

| Hepatic Extraction Ratio (E) | Fraction of drug removed from blood in a single liver pass. | Liver blood flow (QH), protein binding (fuB), and CLint. | Determines oral bioavailability (F = 1 - E) and sensitivity to changes in blood flow and binding. |

| Half-life (t₁/₂) | Time for drug concentration in plasma to reduce by 50%. | Volume of Distribution (Vd) and Total Clearance (CL). | Dictates dosing frequency and time to reach steady state. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mathematical relationships between these parameters, showing how in vitro data is scaled and used to predict in vivo outcomes.

A Practical Guide to Metabolic Stability Assays: From Microsomes to Hepatocytes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is there a significant difference in metabolic stability between human and mouse liver microsomes for my compound?

Answer: Interspecies differences are common and arise from variations in enzyme expression levels and isoform composition between humans and mice. [32] These enzymatic variations, rather than physicochemical properties like LogD or AlogP, are the primary drivers of differing metabolic rates. [32]

- Troubleshooting Tip: If your compound shows high species-specific variability, use caution when extrapolating animal data to predicted human outcomes. Incorporate metabolic stability assays from multiple species early in the lead optimization phase.

FAQ 2: My negative control shows unexpected substrate depletion. What could be wrong?

Answer: Unexpected activity in negative controls typically points to issues with the assay system.

- Troubleshooting Checklist:

- Verify NADPH Omission: Ensure the NADPH Regenerating System was truly omitted from the negative control reaction. Even trace amounts can cause activity. [33]

- Check Microsome Vitality: Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of microsomes, as this can compromise enzymatic activity. Do not thaw microsomes at room temperature; always thaw slowly on ice. [33]

- Assess Solvent Inhibition: Confirm that the final concentration of organic solvent (e.g., from the test article stock solution) is kept below 1% to avoid inhibiting CYP activities. [33]

FAQ 3: The data from my single-point assay is inconsistent. How can I improve reliability?

Answer: Inconsistency often stems from non-optimized, non-initial rate conditions.

- Solution: Ensure you are measuring the reaction under initial rate conditions, where less than 15% of the substrate is consumed. [33] This may require separate optimization of:

- Microsomal protein concentration

- Test article concentration

- Incubation times [33]

FAQ 4: How can I predict metabolic stability computationally to guide my compound design?

Answer: In silico models have become powerful tools for prediction. You can use publicly available models or build your own.

- Public Resources: The ADME@NCATS portal offers open-source models trained on large internal datasets (e.g., >7,000 compounds for HLM stability), achieving accuracies exceeding 80%. [34]

- Advanced Methods: State-of-the-art models like MetaboGNN use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Graph Contrastive Learning to predict stability directly from molecular structures and can identify key molecular fragments associated with stability, offering valuable insights for chemists during lead optimization. [32]

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standard Protocol for Liver Microsomal Stability Assay

The following table outlines a general procedure for measuring NADPH-dependent metabolic stability in liver microsomes using the substrate depletion method. [33] [34]

| Step | Parameter | Details & Critical Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reaction Setup | Prepare a 190 µL incubation mixture containing: 183 µL of 100 mM Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4), 2 µL of 100X Test Article (in solvent, keep final organic solvent <1%), and 5 µL of 20 mg/mL Liver Microsomes. [33] |

| 2 | Pre-incubation | Pre-incubate the mixture (microsomes, buffer, test article) for 5 minutes in a 37°C water bath with gentle agitation. [33] |

| 3 | Reaction Initiation | Initiate the metabolic reaction by adding 10 µL of 20 mM NADPH Regenerating Solution. For negative controls, omit NADPH or use heat-inactivated microsomes. [33] [34] |

| 4 | Incubation | Incubate at 37°C for a predetermined time (e.g., up to 60 min). Use multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60 min) for multi-point assays to determine half-life (t1/2). [34] |

| 5 | Reaction Termination | Terminate the reaction by adding 200 µL of cold organic solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile or Ethyl Acetate). Vortex thoroughly. [33] |

| 6 | Sample Processing | Centrifuge samples at ~3000 rpm for 5-20 minutes to pellet protein. Transfer the supernatant for analysis. [33] [34] |

| 7 | Analysis | Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to quantify the percentage of the parent compound remaining at each time point. [32] [34] |

Quantitative Data from Key Studies

The table below summarizes metabolic stability data and model performances from recent research, providing benchmarks for your own work.

| Study / Model | Dataset Size | Key Metric | Result / Performance | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetaboGNN (2025) [32] | 3,981 compounds | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | HLM: 27.86, MLM: 27.91 (% parent remaining) | Top-performing model from a recent challenge; incorporates interspecies differences. |

| NCATS HLM Model (2024) [34] | 6,648 compounds | Prediction Accuracy | >80% balanced accuracy | Publicly available model on ADME@NCATS portal; leverages cross-species data. |

| NCATS RLM Model (2020) [6] | ~20,216 compounds | Classification (Stable/Unstable) | t1/2 cutoff: 30 min | High-throughput data used to build robust QSAR models for rat metabolic stability. |

Workflow Visualization

Liver Microsomal Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential materials and reagents required for a standard liver microsomal stability assay. [33] [6] [34]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose in the Assay |

|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes (HLM, MLM, RLM) | Source of metabolic enzymes (CYPs, FMOs, UGTs). The subcellular fraction containing the endoplasmic reticulum where Phase I metabolism occurs. [33] |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Critical cofactor system to provide a continuous supply of NADPH, which is essential for CYP and FMO enzyme activity. [33] [6] |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Provides a physiologically relevant pH environment for the enzymatic reactions. [33] |

| Test Article / Compound | The drug candidate or chemical entity whose metabolic stability is being assessed. |

| Organic Solvent (ACN, MeOH, EtOAc) | Used to prepare compound stock solutions and to terminate the metabolic reaction by denaturing proteins. [33] [6] |

| Alamethicin / MgCl₂ / UDPGA | Required for assessing UGT (Uridine glucuronosyltransferase) activity. Alamethicin is a pore-forming agent that facilitates cofactor access to UGT enzymes inside microsomal vesicles. [33] |

| Control Compounds (e.g., Buspirone, Propranolol) | Compounds with well-characterized metabolic profiles are used as assay controls to ensure system functionality and reliability. [6] [34] |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our metabolic stability results show high variability between replicates. What could be the cause and how can we resolve this?

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent hepatocyte viability or improper handling leading to degraded enzyme activity.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Hepatocyte Quality: Confirm viability is >85% using trypan blue exclusion before starting the assay. Do not use thawed hepatocytes if viability is low [35].

- Check Preparation Consistency: Ensure the cell suspension is homogenous before each aliquot. Use an automated liquid handler to minimize pipetting error [35].

- Review Incubation Conditions: Confirm that the temperature is consistently maintained at 37°C and that the incubation platform provides uniform agitation.

- Solution: Implement a strict quality control checkpoint for cell viability and use automation for all sample preparation steps.

Q2: We are detecting unexpected or novel metabolites in our assay. How should we proceed?

- Potential Cause: This may indicate a previously unknown metabolic pathway, which is a key advantage of using integrated hepatocyte assays [35].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm the Finding: Reproduce the result with a fresh aliquot of test compound and hepatocytes to rule out a preparation error.

- Increase Data Scrutiny: Use high-resolution mass spectrometry to accurately determine the elemental composition of the novel metabolite [35].

- Cross-Check Literature: Investigate if this metabolic pathway has been reported in other species or in published literature for similar compounds.

- Solution: Document the finding thoroughly. This novel information is critical for understanding the complete metabolic profile of your compound and should be factored into lead optimization strategies [2].

Q3: The calculated intrinsic clearance (CLint) from our hepatocyte assay does not correlate well with in vivo data. What are the common pitfalls?

- Potential Cause: The assay conditions may not adequately capture all metabolic processes, or scaling factors may be incorrect [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Review Protein Binding: Check if the in vitro incubation medium contains appropriate protein levels, as unbound fraction differences can significantly impact clearance predictions [1].

- Evaluate Metabolite Stability: Ensure that primary metabolites are not undergoing further biotransformation during the assay, which can skew parent depletion rates.

- Assess Enzyme Kinetics: Verify that the hepatocyte concentration and incubation time are within the linear range for metabolite formation and parent depletion.

- Solution: Incorporate physiological scaling factors that account for protein binding and use retrospective analysis to refine in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models for your chemical series [1].

Q4: The automated data analysis software is misclassifying a metabolite. How can we improve the accuracy?

- Potential Cause: The software's metabolite prediction algorithm may lack specific parameters for your compound's unique chemical structure.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Manual Verification: Manually inspect the chromatographic peaks and mass spectra to confirm the software's assignment.

- Adjust Parameters: Modify the software's settings for expected biotransformations (e.g., add a less common metabolic reaction like dioxygenation) based on your compound's likely metabolic soft spots [35].

- Use Control Compounds: Run a set of control compounds with well-characterized metabolic pathways to validate the software's performance under your specific conditions [35].

- Solution: Do not rely solely on automated data processing. Always include a step for expert manual review and curation of the metabolite profile.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Parameters for a Standardized Integrated Hepatocyte Stability Assay

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatocyte Viability | >85% | Ensures robust enzymatic activity for both Phase I and Phase II metabolism [35]. |

| Cell Density | 0.5 - 1.0 x 10^6 cells/mL | Maintains physiological enzyme ratios and linear reaction kinetics [35]. |

| Test Compound Concentration | 1 µM | Minimizes potential for enzyme saturation and non-physiological kinetics [35] [1]. |

| Incubation Time | 0 - 120 minutes | Allows for accurate measurement of parent depletion and metabolite formation over time [35]. |

| Sample Collection Timepoints | 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min | Enables calculation of half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) [35]. |

Table 2: Example Metabolic Stability Data of Control Compounds in Human Hepatocytes

| Control Compound | Major Metabolic Route(s) | Half-life (t1/2, min) | Intrinsic Clearance (CLint, µL/min/million cells) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil | N-dealkylation (CYP3A4) | Short (< 30) | High (> 50) |

| Diazepam | C3-hydroxylation, N-demethylation (CYP3A4/2C19) | Medium (30 - 90) | Medium (10 - 50) |

| Acetaminophen | Glucuronidation, Sulfation (UGT, SULT) | Long (> 90) | Low (< 10) |

Note: The data above is representative. Actual values should be established internally for validation purposes [35].

Experimental Protocols

Methodology: Integrated Hepatocyte Stability Assay for Metabolic Stability and Metabolite Profiling

This protocol outlines the simultaneous assessment of metabolic stability and metabolite identification using cryopreserved hepatocytes in a 96-well format [35].

Part 1: Automated Sample Preparation and Incubation

- Thaw Hepatocytes: Rapidly thaw cryopreserved hepatocytes in a 37°C water bath. Dilute the cells in pre-warmed incubation media (e.g., Williams' E medium).

- Determine Viability: Mix an aliquot of cells with trypan blue and count using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter. Proceed only if viability exceeds 85%.

- Prepare Incubation Mix: Adjust hepatocyte density to 1 million cells/mL in incubation media. Pre-incubate the cell suspension at 37°C with gentle agitation for 10 minutes.

- Initiate Reaction: Add the test compound (from a 100x stock in DMSO) to the hepatocyte suspension to achieve a final concentration of 1 µM. Use an automated liquid handler for precision and to start multiple timepoints simultaneously [35].

- Terminate Reaction: At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min), transfer an aliquot of the incubation mixture to a stopping solution (e.g., acetonitrile containing an internal standard) to precipitate proteins and halt enzymatic activity.

Part 2: LC-HRMS Analysis for Parent and Metabolite Monitoring

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the stopped reaction samples to remove precipitated protein. Inject the supernatant onto a Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) system.

- Chromatography: Use a reversed-phase C18 column with a gradient elution of water and acetonitrile (both containing 0.1% formic acid) to separate the parent compound and its metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the HRMS in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Use a full-scan MS survey to monitor parent compound depletion, followed by MS/MS scans on the most intense ions to obtain structural information for metabolite identification [35].

Part 3 & 4: Automated Data Analysis and Reporting

- Stability Assessment: Process the parent compound peak area versus time data using automated software to calculate the depletion half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint).

- Metabolite Profiling: Use streamlined batch-processing software to identify metabolites based on accurate mass shifts, isotope patterns, and MS/MS fragmentation patterns compared to the parent compound [35].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Hepatocyte Stability Assays

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Biologically relevant in vitro system containing the full complement of Phase I and Phase II metabolic enzymes, providing a holistic view of drug metabolism [35] [19]. |

| Williams' E Medium | A complex cell culture medium designed to maintain hepatocyte function and viability during the incubation period. |

| Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) | Enables simultaneous quantitative analysis of parent drug depletion and qualitative identification of metabolite structures based on accurate mass measurement [35]. |

| Automated Liquid Handling System | Improves assay precision and throughput by reducing manual pipetting errors and ensuring consistent sample preparation across multiple timepoints and compounds [35]. |

| Control Compounds (e.g., Verapamil, Diazepam) | Used to validate assay performance. These have well-characterized metabolic rates and pathways, serving as benchmarks for system suitability [35]. |

| Data Processing Software | Automated tools for batch-processing HRMS data to calculate metabolic stability parameters and generate metabolite profiles, significantly accelerating data analysis [35]. |

In the pursuit of overcoming poor metabolic stability in drug candidates, understanding specific metabolic pathways is crucial. Liver subcellular fractions, namely S9 and cytosol, are invaluable in vitro tools that provide a focused view of metabolic processes, particularly those mediated by cytosolic enzymes like aldehyde oxidase (AO) and various conjugation pathways [5]. These systems enable researchers to deconstruct the liver's metabolic capacity, offering a high-throughput, cost-effective means to identify soft spots and guide structure-activity relationship (SAR) campaigns early in lead optimization [36] [37].

The liver S9 fraction is the supernatant obtained after the first centrifugation (9,000 x g) of a liver homogenate [36]. It contains both microsomal (endoplasmic reticulum) and cytosolic enzymes, providing a broad spectrum of both Phase I and Phase II metabolic activities [36] [37]. In contrast, the liver cytosol is the soluble fraction obtained after further high-speed centrifugation (typically 105,000 x g) of the S9 fraction, and it contains exclusively soluble cytosolic enzymes, but no microsomal enzymes [38] [5].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Metabolic Stability Systems

| Feature | Liver S9 Fraction | Liver Cytosol | Liver Microsomes | Hepatocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Composition | Both microsomal & cytosolic enzymes [36] [37] | Only cytosolic enzymes [38] [5] | Only microsomal enzymes [36] | Full cellular complement of enzymes & transporters [36] |

| Key Enzymes Present | CYPs, UGTs, AO, SULTs, GSTs [36] [5] | AO, SULTs, GSTs, Xanthine Oxidase [36] [5] | CYPs, UGTs, FMOs [36] | All hepatic Phase I & II enzymes [36] |

| Cofactor Requirements | Requires exogenous cofactors (e.g., NADPH, UDPGA, PAPS) [36] [37] | Requires cofactors for specific reactions (e.g., PAPS for SULT) [38] | Requires exogenous cofactors (e.g., NADPH for CYPs) [36] | Contains endogenous cofactors; more physiologically relevant [36] |

| Primary Use in Stability Screening | Comprehensive Phase I & II metabolism; identifying AO involvement [36] [37] | Specific assessment of cytosolic enzyme metabolism (e.g., AO) [5] | Primary assessment of Phase I, CYP-mediated metabolism [36] | Gold standard for overall hepatic clearance; full metabolic profile [36] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Liver S9 Stability Assay Protocol

This protocol is designed to measure the intrinsic clearance of a test compound using liver S9 fraction.

Incubation Conditions:

- Test System: Human or rat liver S9 fraction (gender-pooled) [36].

- Protein Concentration: Must be optimized; S9 fractions have an inherent dilution of enzymes compared to microsomes [36].

- Incubation Temperature: 37°C [37].

- Substrate Concentration: Typically 1-3 µM [36] [37].

- Cofactors: Supplement with relevant cofactors based on the metabolic pathways under investigation [37]:

- NADPH-regenerating system: For Phase I oxidative metabolism.

- Uridine 5'-diphospho-α-D-glucuronic acid (UDPGA): For glucuronidation.

- 3'-Phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS): For sulfation.

- Reduced Glutathione (GSH): For trapping reactive metabolites or GST-mediated conjugation.

- Reaction Termination: Using ice-cold acetonitrile or methanol at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 45 minutes) [37].

Sample Analysis:

- Following centrifugation, the supernatant is analyzed via Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to monitor the disappearance of the parent compound over time [36] [37].

- Data is quantified by plotting the natural logarithm of the peak area ratio (compound/internal standard) against time.

Data Calculation:

- The elimination rate constant (k) is determined from the slope of the depletion curve.

- In vitro half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) are calculated using the following equations [37]:

- Half-life, t1/2 (min) = ln(2) / k

- Intrinsic Clearance, CLint (µL/min/mg protein) = (Incubation Volume / Protein) × (0.693 / t1/2)