Optimizing Binding Affinity and Selectivity: A Strategic Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

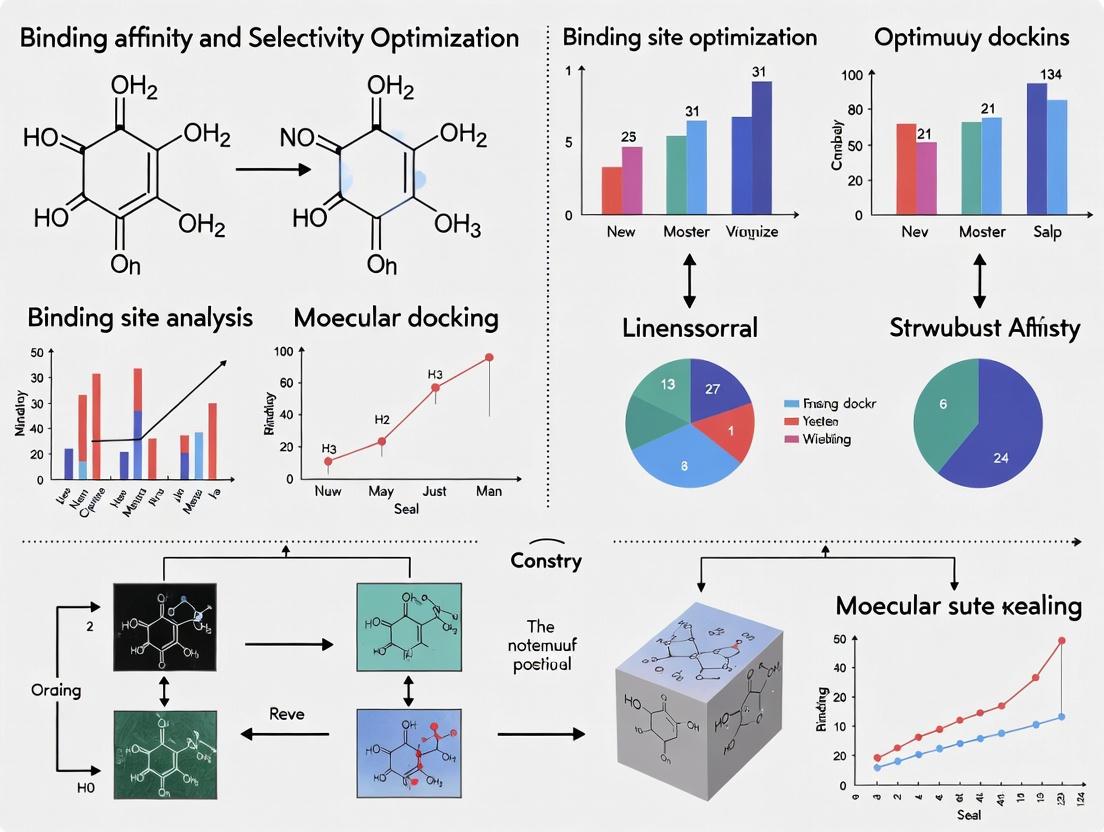

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize the critical parameters of binding affinity and selectivity in lead compounds.

Optimizing Binding Affinity and Selectivity: A Strategic Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize the critical parameters of binding affinity and selectivity in lead compounds. It covers the foundational biophysical principles, advanced methodological approaches including computational and experimental strategies, practical troubleshooting for common challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application, enabling the design of more effective and specific therapeutic agents with improved clinical potential.

The Biophysical Foundations of Molecular Recognition: Affinity, Selectivity, and Kinetics

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. My drug candidate has high affinity for its target (low nM Kd), but it causes severe off-target effects in animal studies. What could be the issue and how can I investigate it?

A high-affinity drug can still bind promiscuously to off-target proteins, leading to adverse effects. The issue is likely a lack of selectivity, not affinity.

- How to Troubleshoot:

- Profile Against Related Targets: Test your compound in binding or functional assays against a panel of closely related proteins (e.g., other kinases in the same family, or other HER receptors if targeting HER2) [1]. A selective compound will show a strong signal for the target and minimal to no signal for the off-targets at the same concentration.

- Check Thermodynamic Signature: Analyze the binding thermodynamics using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). Compounds with binding driven largely by entropy (often from hydrophobic interactions) tend to be more promiscuous. In contrast, enthalpy-driven binding (often from well-oriented hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions) is frequently associated with higher selectivity because these specific interactions are less likely to be perfectly replicated in off-target proteins [2] [3].

- Use Chemical Proteomics: Employ techniques like affinity chromatography with an immobilized version of your drug candidate to pull down interacting proteins from a complex lysate. Identify the bound proteins with mass spectrometry to reveal off-target interactions directly from a biological system [4].

2. My antibody works perfectly in a Western blot using a recombinant protein, but gives a smeared or multi-band result in cell lysates. How can I validate its true specificity?

A signal on a recombinant protein only confirms that the antibody can bind to the target. The smeared pattern in lysates indicates potential cross-reactivity with other proteins, meaning the antibody lacks specificity for the intended target in a complex biological context [1].

- How to Troubleshoot:

- Use Genetically Validated Controls: The most robust method is to compare signals from biological material with high expression, low expression, and a complete knockout (KO) of your target protein (e.g., using CRISPR/Cas9). The antibody signal should be strong, weak, and absent, respectively, in these samples [1].

- Test Specificity by Competition: Pre-incubate the antibody with the immunizing peptide or the purified target protein. If the signal on the Western blot is significantly reduced or abolished, it confirms that the binding is specific to that epitope/target.

- Verify Antibody Integrity: Check the antibody's molecular integrity via SDS-PAGE. Exposure to repeated freeze-thaw cycles, high temperatures, or detergents can compromise the antibody, leading to loss of specificity and selectivity [1].

3. I am optimizing a lead compound for a protein target with many close homologs. How can I rationally improve its selectivity without sacrificing binding affinity?

Achieving selectivity within a protein family is a central challenge in drug discovery. The goal is to exploit subtle differences between the target and off-target proteins.

- How to Troubleshoot:

- Target Structural Differences: Obtain or use available crystal structures of your target and its closest homologs. Look for differences in shape and amino acid composition within the binding pocket. A rational strategy is to add a chemical group to your lead compound that fits into a specific cavity in your target but clashes sterically or electrostatically with the corresponding region in the off-targets [5]. For example, a single amino acid difference (valine vs. isoleucine) between COX-1 and COX-2 was exploited to design highly selective COX-2 inhibitors [5].

- Leverage Enthalpic Interactions: Focus on introducing strong, well-oriented hydrogen bonds or salt bridges with unique residues in your target. The high directionality of these interactions means they are less likely to be satisfied in off-target proteins, thereby improving selectivity. This often results in a more favorable binding enthalpy [2] [3].

- Employ Conformational Constraints: Reduce the flexibility of your lead compound by introducing ring structures or other constraints. A more rigid molecule is less able to adopt the conformations required to bind to multiple different off-target proteins, thereby enhancing selectivity [2].

Core Definitions and Relationships

To effectively troubleshoot, a clear understanding of the fundamental concepts is essential. The table below defines the key terms.

Table 1: Core Concepts in Molecular Recognition

| Term | Definition | Key Question | Common Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | The strength of the interaction between a single ligand and a single binding site. | How tightly does it bind? | Dissociation Constant (Kd), Inhibition Constant (Ki), IC50 |

| Selectivity | The ability of a ligand to preferentially bind to one target over another. | How much does it prefer target A over target B? | Selectivity Coefficient (e.g., Kd, off-target / Kd, target), Fold-Selectivity |

| Specificity | The narrowness of a drug's action, often referring to the number of targets it interacts with or the number of downstream effects it produces. | How many different targets or effects does it have? | Qualitative description (e.g., "highly specific," "promiscuous"), Number of off-targets in a broad panel screen |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these concepts in the context of experiment optimization.

Thermodynamic Profiles and Selectivity

The thermodynamic signature of binding (the balance of enthalpy, ΔH, and entropy, ΔS) provides deep insight into the forces driving the interaction and is a powerful tool for troubleshooting selectivity issues.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Signatures and Their Implications for Selectivity

| Binding Driver | Molecular Origin | Typical Impact on Selectivity | Design Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enthalpy-Driven (Favorable ΔH) | Strong, well-oriented interactions like hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. | Higher Selectivity. The precise geometry required for these interactions is less likely to be matched by off-target proteins [3]. | Optimize polar interactions; target unique hydrogen bond donors/acceptors in the binding site. |

| Entropy-Driven (Favorable ΔS) | Hydrophobic effects, desolvation, and release of ordered water molecules. | Lower Selectivity (more promiscuous). Hydrophobic interactions are less sensitive to the precise geometry of the binding pocket, increasing the risk of off-target binding [2] [3]. | Fill hydrophobic cavities; introduce conformational constraints to limit promiscuity. |

The pathway from lead compound to optimized drug can be visualized as a thermodynamic optimization process, as shown in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Determining Binding Selectivity Coefficient

This protocol is used to quantify how preferentially a ligand binds to a primary target over a secondary, related target.

- Determine Affinity for Primary Target: Using a method like ITC, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), or a radioligand binding assay, measure the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd1) for the ligand binding to its primary target.

- Determine Affinity for Off-Target: Under identical experimental conditions (buffer, temperature, etc.), measure the dissociation constant (Kd2) for the ligand binding to the off-target protein.

- Calculate Selectivity Coefficient: The selectivity coefficient is defined as the ratio of the two dissociation constants [6]:

- Selectivity Coefficient = Kd2 / Kd1 A value greater than 1 indicates selectivity for the primary target. The larger the value, the greater the selectivity.

Protocol 2: Validating Antibody Specificity and Selectivity in Western Blot

This protocol outlines the best practices for confirming that an antibody is both specific (binds only to the intended target) and selective (binds to a unique epitope on that target) in complex lysates [1].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare three key samples:

- Wild-Type Lysate: Lysate from cells or tissue expressing the target protein.

- Knock-Out Lysate: Lysate from cells or tissue where the target gene has been genetically ablated (e.g., via CRISPR/Cas9).

- Overexpression Lysate: Lysate from cells transfected to overexpress the target protein.

- Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer: Run the samples on an SDS-PAGE gel and transfer to a membrane.

- Immunoblotting: Probe the membrane with the antibody of interest at its optimal dilution.

- Analysis:

- Specificity Check: The antibody signal should be present in the wild-type and overexpression lysates but absent in the knock-out lysate. This confirms that the signal is specific to the target protein and not due to cross-reactivity.

- Selectivity Check: The antibody should produce a single band at the expected molecular weight. Multiple bands suggest cross-reactivity with other proteins, indicating low selectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Binding and Selectivity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Gold-standard technique for directly measuring the thermodynamics of binding (Kd, ΔH, ΔS) in solution without labeling. |

| Recombinant Proteins (Target & Off-Targets) | Purified proteins are essential for in vitro binding assays to determine affinity and selectivity coefficients. |

| Genetically Engineered Cell Lines (e.g., Knock-Outs) | Provide biologically relevant negative controls to validate the specificity of antibodies or compounds in a complex cellular environment. |

| Selective Radioligands or Fluorescent Probes | Used in competitive binding assays to measure the affinity of unlabeled test compounds for the target and off-target proteins. |

| Affinity Resin / Beads | Used to immobilize a drug candidate for chemical proteomics (pulldown) experiments to identify off-targets from cell lysates. |

| Broad-Panel Screening Services | Commercial panels (e.g., kinase, GPCR) can profile compound activity across dozens to hundreds of targets to rapidly assess promiscuity. |

FAQs: Understanding Residence Time and Its Impact

Q1: What is drug-target residence time and why has it become a critical parameter in drug discovery?

A1: Drug-target residence time (RT) is defined as the lifetime of the drug-target binary complex, quantified as the reciprocal of the dissociation rate constant (RT = 1/koff) [7] [8]. While early drug discovery focused primarily on thermodynamic affinity (KD, IC50), research has shown that insufficient efficacy accounts for a significant proportion of drug failures in late-stage clinical trials [7]. The temporal stability of the ligand-receptor complex is now acknowledged as a critical factor influencing both drug efficacy and pharmacodynamics [7]. In vivo, where drug concentrations fluctuate due to ADME processes, a long residence time can ensure sustained pharmacological effect even after free drug concentrations have declined below the equilibrium dissociation constant [7] [8].

Q2: How does the "open system" of the body make residence time more relevant than classic equilibrium measurements?

A2: In a closed, in vitro system, drug concentration is constant, allowing equilibrium measurements like IC50 and KD to be highly informative. However, the body is an open system where a drug must navigate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, causing its concentration at the target site to be in constant flux [8]. In this environment, the rate of drug association with its target is often limited by these pharmacokinetic processes rather than the microscopic association rate constant (kon) [8]. Conversely, the dissociation rate (koff) is a first-order process, independent of drug concentration. Therefore, a complex with a slow koff (long residence time) remains intact despite falling systemic drug levels, providing more durable target coverage and pharmacologic effect [8].

Q3: What are the key binding models that help explain the molecular basis of residence time?

A3: There are three primary models for conceptualizing ligand binding, each with implications for RT [7]:

- Lock-and-Key Model: This simple model views binding as a single-step process governed by steric and electronic complementarity. Here, RT is simply the inverse of koff [7].

- Induced-Fit Model: This model proposes that initial ligand binding induces a conformational change in the receptor, leading to an active complex (LR*). This multi-step process introduces additional kinetic steps that can prolong the overall residence time [7].

- Conformational Selection Model: This model posits that the receptor exists in an equilibrium of conformations before the ligand binds. The ligand selectively stabilizes either the active (R*) or inactive (R) state. The RT in this case is defined by the dissociation from the final selected complex [7]. In practice, induced-fit and conformational selection are now viewed as interconnected concepts [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Binding Assays for Kinetic Parameters

| Problem Scenario | Expert Recommendations | Underlying Principle & Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No assay window in TR-FRET | Verify instrument setup, particularly that the correct emission filters are installed. The excitation filter primarily impacts the window, but emission filters are critical for TR-FRET success [9]. | TR-FRET is a distance-dependent phenomenon. Incorrect filters will fail to capture the specific signal. Test your reader setup with validated reagents before running assays [9]. | ||

| High variability in IC50 values between labs | Investigate differences in stock solution preparation. This is a primary reason for EC50/IC50 discrepancies when the same protocol is used in different locations [9]. | Minor differences in compound solubility, solvent evaporation, or stability in DMSO stocks can lead to significant concentration inaccuracies, directly affecting results [9]. | ||

| Poor Z'-factor despite a large assay window | The Z'-factor incorporates both the assay window and the data variability (standard deviation). A large window with high noise can yield a poor Z'-factor. Focus on reducing pipetting errors and ensuring reagent homogeneity to lower standard deviations [9]. | Z'-factor = 1 - [ (3SD_high + 3SD_low) / | Meanhigh - Meanlow | ]. An assay with a Z'-factor > 0.5 is considered excellent for screening [9]. |

| No assay window in a Z'-LYTE assay | Systematically determine if the issue is with the development reaction or instrument setup. Create a 100% phosphopeptide control (no development reagents) and a 0% phosphopeptide control (with excess development reagent). If the ratio difference is not ~10-fold, troubleshoot the development reagent dilution. If the ratio difference is present, the issue is likely instrument setup [9]. | The Z'-LYTE assay relies on a differential cleavage rate between phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated peptides by a development protease. Over- or under-development nullifies this differential [9]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Biophysical Characterization

| Problem Scenario | Expert Recommendations | Underlying Principle & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Low signal in SEC-DLS | For size-exclusion chromatography coupled with dynamic light scattering (SEC-DLS), a higher sample concentration is typically required (e.g., 2-5 mg/mL for a 100 µL injection) compared to batch-mode DLS. This is because the measurement correlation time per data point is shorter in a flowing system [10]. | Batch DLS can run correlations for longer, allowing measurements at concentrations <1 mg/mL. The higher concentration in SEC-DLS compensates for the shorter data collection time per slice [10]. |

| Inaccurate molecular weight from DLS | Use DLS for hydrodynamic size (Rh) and estimate MW with caution. For accurate MW, use Static Light Scattering (SLS). SLS can measure MW accurately to within 2-5% if the dn/dc (refractive index increment) is known, which is typical for proteins [10]. | DLS estimates MW based on size and a assumed shape model, which can be unreliable. SLS measures MW directly from the scattered light intensity without relying on shape [10]. |

| Aggregation interfering with analysis | Utilize a combination of techniques. SEC-MALS is excellent for soluble aggregates up to ~50 nm. For larger aggregates, Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4) is more suitable as it lacks the size exclusion limit of SEC columns [10]. | Each technique has its own size range and resolution limitations. SEC-MALS provides high resolution for monomers and small oligomers, while AF4 can handle very large aggregates without column retention [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Residence Time and Binding Studies

| Item / Technique | Function in Research | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TR-FRET Assays (e.g., LanthaScreen) | A homogeneous, non-radioligand method to study ligand binding and competition in real-time, suitable for measuring binding kinetics [9]. | Uses lanthanide donors (Tb, Eu) and acceptor dyes. Ratiometric data analysis (acceptor/donor) corrects for pipetting variance and reagent lot-to-lot variability, improving data robustness [9]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures the thermal denaturation profile of a protein, providing the melting temperature (Tm). Used to assess target stability and the effect of ligands on structural stability [11]. | A higher Tm indicates a more stable protein. Useful for formulation development and for assessing if a compound stabilizes the target, which can correlate with longer residence time [11]. |

| Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) | A first-principle method for analyzing solution homogeneity, aggregation, and molecular weight without a solid phase. Particularly useful for quantifying low levels of aggregates [11]. | Sedimentation Velocity (SV-AUC) can detect and quantify different species in a sample, providing information on size, shape, and approximate molecular weight under native conditions [11]. |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) / MALS | Directly determines the absolute molecular weight of macromolecules in solution, either in batch mode or coupled with SEC (SEC-MALS) [10] [11]. | Unlike DLS, it does not rely on molecular shape or hydrodynamic models. SEC-MALS is a key technique for characterizing protein aggregates and oligomeric state [10]. |

| Intrinsic Fluorescence | Monitors changes in the local environment of tryptophan and other aromatic residues, providing insights into the tertiary structure of a protein [11]. | Sensitive to conformational changes induced by ligand binding, which can be used to monitor binding events and stability during formulation or comparability studies [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Workflow 1: Assessing Residence Time via a Kinetic TR-FRET Assay

Aim: To determine the dissociation rate constant (koff) and residence time (1/koff) for a small molecule inhibitor binding to a kinase.

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Reagents: Dilute the Tb-labeled anti-His antibody (donor) and fluorescently-labeled tracer (acceptor) in assay buffer. Prepare a solution of the His-tagged kinase target.

- Form Pre-complex: Incubate the kinase with the tracer and the Tb-donor antibody to form the equilibrium complex in a microplate. Include a control well without inhibitor to define the 100% signal.

- Initiate Dissociation: To measure koff, add a high concentration of an unlabeled competitive inhibitor (e.g., 100x its KD) to all wells. This prevents any dissociated tracer from rebinding to the target.

- Time-Resolved Measurement: Immediately place the plate in a compatible TR-FRET reader. Set the instrument to excite the donor and measure the acceptor and donor emission signals at defined intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) over a period of 1-3 hours or until the signal stabilizes.

- Ratiometric Data Analysis:

- For each time point, calculate the emission ratio: Acceptor Signal / Donor Signal (e.g., 520 nm/495 nm for Tb) [9].

- Normalize the data to a response ratio if desired, where the starting ratio is defined as 1.0.

- Fit the decay of the ratio over time to a one-phase exponential decay model:

Y = (Y0 - Plateau) * exp(-K * X) + Plateau, where K is koff. - Calculate the residence time as 1/koff.

The diagram below illustrates this workflow and the underlying kinetic process:

Workflow 2: Biophysical Workflow for Higher-Order Structure and Stability

Aim: To characterize the higher-order structure and stability of a biologic drug candidate, which can inform on its potential for prolonged target engagement.

Detailed Protocol:

- Secondary Structure Analysis:

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Perform far-UV CD (190-250 nm) to estimate the composition of α-helix, β-sheet, and random coil. Compare spectra of the protein alone and in complex with its ligand to detect binding-induced structural changes [11].

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Analyze the Amide I and Amide II bands to quantify secondary structure, a technique particularly sensitive to β-sheet content and thus valuable for monoclonal antibodies [11].

- Tertiary Structure and Stability Analysis:

- Intrinsic Fluorescence: Measure the fluorescence emission spectrum of tryptophan residues (e.g., excite at 280 nm, emit from 300-400 nm). A shift in the wavelength maximum indicates a change in the local tertiary environment [11].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Heat the protein sample (e.g., from 20°C to 100°C) and measure the heat absorption. Identify the melting temperature (Tm). A higher Tm indicates greater conformational stability, which can be influenced by ligand binding [11].

- Solution Behavior and Aggregation State:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Perform in batch mode to measure the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) and detect the presence of large aggregates or oligomers in the native formulation [10] [11].

- SEC-MALS: Inject the sample onto a size-exclusion column coupled to a Multi-Angle Light Scattering detector. This provides an absolute molecular weight for the main peak and any aggregates, independent of elution volume [10] [11].

The logical relationship between these techniques is shown below:

FAQs: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the Lock-and-Key, Induced Fit, and Conformational Selection models?

These models describe different mechanisms of molecular recognition between a protein and its ligand (e.g., a drug molecule). The core difference lies in the timing and nature of the conformational changes that enable a perfect fit.

- Lock-and-Key: Proposes that the protein (lock) and ligand (key) are pre-complementary and rigid. They bind without any significant structural changes [12] [13].

- Induced Fit: Suggests the ligand is not perfectly complementary. The initial binding induces a conformational change in the protein's structure to achieve a better fit, like a hand putting on a glove [12] [14].

- Conformational Selection: Proposes that the protein already exists in an ensemble of multiple conformations in solution. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes the pre-existing conformation that is most complementary to it, shifting the population equilibrium toward that bound state [12] [14] [13].

Q2: Why is understanding the correct binding mechanism critical for optimizing drug affinity and selectivity?

The binding mechanism directly determines the kinetics and thermodynamics of the interaction, which are crucial for drug efficacy.

- Impact on Affinity: Binding affinity (Kd or Ki) is a ratio of the dissociation rate (koff) and the association rate (kon). The conformational selection model, for instance, can explain scenarios where a drug has a slow off-rate, leading to prolonged target engagement and higher efficacy, because the protein must transition back to a rare, unbound conformation to release the drug [12] [15].

- Impact on Selectivity: A drug that operates via conformational selection can achieve high selectivity by specifically targeting a protein conformation that is unique to a specific tissue or disease state, minimizing off-target effects [14] [16]. Ignoring mechanisms like ligand trapping, which dramatically increases affinity by slowing dissociation, can lead to inaccurate predictions in computer-aided drug design [12].

Q3: My kinetic data shows a complex, multi-phase binding curve. Which model does this suggest?

Multi-phase kinetics often indicate a binding process more complex than a simple one-step Lock-and-Key mechanism. This is characteristic of a mixed mechanism or extended conformational selection model [14] [16]. In this scenario, an initial, rapid conformational selection step is often followed by a slower induced fit adjustment after the initial binding event, leading to a final, stabilized complex with very high affinity.

Q4: How do Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) challenge traditional binding models, and what are the implications for drug discovery?

IDPs or regions lack a stable 3D structure yet perform critical functions. They do not fit the Lock-and-Key model and are best described by a conformational selection/folding mechanism, sometimes involving "fly-casting" where the disordered region can reach out and bind a partner before folding [15] [13]. For drug discovery:

- Faster On-Rates: IDPs can have very fast association rates (on-rates), often at or even exceeding the diffusion limit, which can be beneficial for signaling molecules [15].

- Weak Affinity: The energy cost of folding upon binding often results in weaker overall binding affinity (Kd) compared to folded proteins, but this can be optimized for transient interactions that require rapid dissociation [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Binding Affinity Measurements

Problem: Measured binding affinities (Kd/Ki) vary significantly between direct (e.g., ITC) and indirect (e.g., enzymatic inhibition) assays.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Assay conditions not at equilibrium for slow-binding inhibitors. | Perform a time-course experiment to determine if signal stabilizes. | Increase incubation time before measurement. |

| Mixed binding mechanism present, where the dominant pathway depends on ligand concentration [14]. | Use stop-flow kinetics to measure rate constants (kon, koff) across a range of ligand concentrations [13]. | Analyze data using a two-step binding model that incorporates both conformational selection and induced fit. |

| Ligand Trapping, a process not captured by standard models, is occurring, leading to an artificially slow k_off [12]. | Use surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to directly measure the dissociation rate under different conditions. | Develop computational tools that can model the dissociation (off-rate) pathway, not just the binding step. |

Issue 2: Failure to Improve Selectivity Despite Extensive Optimization

Problem: A lead compound shows potent activity against the intended target but also has high activity against closely related off-target proteins, leading to side effects.

Solution Strategy: Shift the design strategy from an "induced fit" mindset to a "conformational selection" approach.

- Identify Unique Conformations: Use structural biology (X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify conformations of your target protein that are not populated by the off-target proteins [16]. The unliganded protein's ensemble may contain rare but key conformations.

- Design Selective Binders: Design ligands that specifically recognize and stabilize these unique, pre-existing conformations. This leverages the inherent dynamic differences between proteins for selectivity.

- Validate Mechanism: Use NMR spectroscopy or single-molecule FRET to confirm that your optimized ligand binds by shifting the population toward the selected conformation, rather than inducing a common conformation shared with off-targets [14].

Issue 3: Computational Docking Poses Do Not Match Experimental Complex Structures

Problem: The predicted binding pose from molecular docking software shows poor agreement with the pose determined by X-ray crystallography.

Solution Workflow:

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 1: Typical Kinetic and Affinity Ranges for Protein-Ligand Interactions

| Interaction Type | Typical Kd Range | Typical k_on (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Typical k_off (s⁻¹) | Functional Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong, Long-lived (e.g., Streptavidin-Biotin) | nM - pM | 10^5 - 10^7 | 10^-5 - 10^-3 | Irreversible signaling; structural complexes. |

| Transient Signaling (e.g., Hormone-Receptor) | nM - μM | 10^6 - 10^7 | 10^-2 - 10^1 | Allows for rapid signal termination and response modulation [15]. |

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | ~0.1 μM | 10^9 - 10^10 | 10^2 - 10^4 | Optimized for speed of association in regulatory processes [15]. |

| Enzyme-Substrate | μM - mM | 10^6 - 10^8 | 10^2 - 10^4 | Fast turnover often limited by product dissociation rate [15]. |

Table 2: Computational Methods for Studying Binding Mechanisms

| Method | Principle | Application to Binding Models | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Predicts binding pose and affinity using a scoring function. | Good for Lock-and-Key; often fails for Induced Fit/Conformational Selection [12]. | Treats protein as largely rigid; poor correlation with experimental affinity [12]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates physical movements of atoms over time. | Can capture full pathway of Induced Fit and Conformational Selection [16]. | Computationally expensive; limited timescales. |

| MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA | End-state method to calculate free energy from MD trajectories. | Used to compare stability of different complexes and conformers [12] [16]. | Can be inaccurate due to simplifications in solvation and entropy. |

| Meta-Dynamics | Accelerates exploration of free energy landscape. | Ideal for identifying rare conformations relevant to Conformational Selection. | High computational cost and complex setup. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Mechanism Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Protein (Wild-type & Mutants) | The core target for binding studies. | Generating a conformationaly "rigid" mutant (e.g., by introducing disulfide bonds) to test the Conformational Selection model. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free technique to measure binding kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (Kd) in real-time. | Directly observing a slow k_off, which is a hallmark of conformational selection or ligand trapping mechanisms [12]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Probes protein dynamics and structural changes at atomic resolution in solution. | Identifying the existence of multiple pre-existing conformations in the free protein ensemble [14]. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Measures very fast reaction kinetics (milliseconds). | Distinguishing between induced fit and conformational selection by analyzing the ligand concentration dependence of fast and slow kinetic phases [13]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) | Simulates the detailed trajectory of a binding event at the atomic level. | Visualizing the "protein dance" of mutual selection and adjustment in an extended conformational selection model [14] [16]. |

| PROTAC Molecules | Bifunctional molecules that recruit a protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase for degradation. | Degrading a specific protein conformation to study the functional impact of its removal, validating its biological role [17]. |

Visualizing the Evolution of Binding Models

The understanding of molecular recognition has evolved from simple, rigid concepts to a dynamic and integrated view.

Core Concepts: The Language of Molecular Binding

Molecular binding is a dynamic process governed by the precise interplay of thermodynamic and kinetic parameters. A firm grasp of these concepts is fundamental for optimizing binding affinity and selectivity in drug design.

FAQ: What is the difference between binding affinity and binding kinetics? Binding affinity describes the overall strength of the interaction at equilibrium, quantified by the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd). In contrast, binding kinetics describe the speeds of the processes that lead to that equilibrium, namely the association rate (kon) and dissociation rate (koff) [18] [19].

FAQ: Why is the dissociation rate constant (koff) gaining attention in drug discovery? While affinity (Kd) has long been the primary focus, the dissociation rate constant (koff) directly determines the drug-target residence time (τ = 1/koff) [20] [18]. A longer residence time can lead to a more sustained pharmacological effect and improved selectivity, which is a crucial factor for clinical success [20].

The table below summarizes the key parameters that form the foundation of this analysis.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Molecular Binding Interactions

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Significance in Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔG | The overall energy change during binding; indicates spontaneity. | A negative ΔG signifies a favorable, spontaneous binding reaction. It is the ultimate measure of binding affinity [21]. |

| Enthalpy Change | ΔH | The heat exchange during binding; represents energy from molecular bonds. | A favorable negative ΔH indicates the formation of strong non-covalent bonds (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces) [21]. |

| Entropy Change | ΔS | The change in molecular disorder. | Binding often incurs an entropic penalty due to reduced freedom; however, release of ordered water molecules can provide an entropic gain [21]. |

| Association Rate Constant | k_on | The rate at which the ligand and target form a complex. | Governs how quickly a drug finds its target. Influenced by molecular diffusion and recognition [18] [21]. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | k_off | The rate at which the ligand-target complex breaks apart. | Determines the stability and duration of the complex. Directly linked to drug-target residence time [20] [18]. |

| Dissociation Constant | K_d | The equilibrium constant (Kd = koff / k_on). | A measure of binding affinity; a lower K_d indicates a tighter interaction [18] [21]. |

These parameters are interconnected. The relationship between the thermodynamic (Kd, ΔG) and kinetic (kon, koff) constants is described by the following equations, which are central to interpreting experimental data:

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Experimental Challenges

This section addresses common experimental problems related to binding studies, providing solutions grounded in thermodynamic and kinetic principles.

FAQ: During binding assays, I consistently get a high background signal. What thermodynamic or kinetic factors should I investigate? A high background is frequently a symptom of non-specific binding driven by weak, low-affinity interactions. Thermodynamically, these are characterized by a Gibbs free energy (ΔG) close to zero, representing a shallow energy well, unlike the deep energy well of specific, high-affinity binding [21]. To troubleshoot:

- Optimize Your Wash Buffers: Increase the stringency of wash buffers. Incorporate mild detergents or competitive agents to disrupt weak, non-specific interactions without affecting the specific complex.

- Review Antibody Selection: Ensure your primary antibody has a highly negative ΔG for the target antigen. A low dissociation constant (K_d) indicates high specificity and affinity, which helps minimize off-target binding [21].

FAQ: My binding data shows a good affinity (Kd), but the compound has poor efficacy in functional assays. What kinetic parameter might be the culprit? This disconnect can often be traced to a fast dissociation rate (koff). A compound may have a favorable Kd due to a very fast association rate (kon), but if it dissociates too quickly (high k_off), it cannot maintain target engagement long enough to elicit a robust biological effect [20] [19]. You should:

- Measure the Residence Time: Determine the dissociation rate constant (koff) and calculate the residence time (τ = 1/koff). A short residence time may explain the poor efficacy [18].

- Investigate Binding Site Conformation: Use techniques like molecular dynamics simulations to see if the ligand is inducing a protein conformation that is not therapeutically relevant or is unstable [20].

FAQ: Why does modifying a ligand to form more hydrogen bonds sometimes result in worse affinity, despite a favorable enthalpy (ΔH) change? This paradox highlights the critical balance between enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) in the Gibbs free energy equation (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS). While adding hydrogen bonds can make ΔH more favorable, it can also:

- Introduce Rigidity: Over-engineering a ligand can over-constrain it, leading to a large entropic penalty (unfavorable -TΔS) upon binding as it loses conformational freedom.

- Displace Ordered Water: If the new hydrogen bonds displace water molecules that were already favorably bonded to the protein, the net energetic gain may be minimal or even negative. The key is to target water molecules that are not optimally coordinated [22].

FAQ: How can I experimentally determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants for my ligand? The gold standard is a real-time, label-free method like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [18] [23]. The general protocol is:

- Association Phase: Immobilize the target protein and flow the ligand over it. Monitor the formation of the complex in real-time at several ligand concentrations.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch to a ligand-free buffer and monitor the decrease in the complex signal as the ligand dissociates.

- Global Fitting: The resulting sensoryrams (binding curves over time) are fitted globally to a binding model to extract the kinetic rate constants, kon and koff [18]. The affinity (Kd) can then be calculated as koff/k_on.

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Determining Kinetic Rate Constants via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

This protocol outlines the key steps for determining binding kinetics, a critical process for understanding drug-target residence time [18].

Materials & Reagents:

- Research-Grade SPR Instrument: (e.g., Biacore series) capable of real-time, label-free detection.

- Carboxymethylated Dextran Sensor Chip: (e.g., CM5 chip) for protein immobilization.

- Purified Target Protein: ≥90% purity, in a suitable immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5-5.5).

- Ligand Solutions: Serially diluted in running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP). Concentrations should span a range above and below the expected K_d.

- Amine-Coupling Kit: Contains N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N-ethyl-N'-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) for covalent immobilization.

- Regeneration Solution: (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0) to remove bound ligand without damaging the immobilized protein.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Protein Immobilization: Activate the sensor chip surface using the NHS/EDC mixture. Inject the purified target protein over the activated surface to achieve a covalently immobilized layer. Deactivate any remaining active esters.

- Association Phase: Inject a series of ligand concentrations over the immobilized protein surface one by one. Monitor the increase in Resonance Units (RU) over time for each concentration.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch back to running buffer and monitor the decrease in RU as the ligand dissociates.

- Surface Regeneration: Apply a short pulse of regeneration solution to completely remove any remaining bound ligand, readying the surface for the next sample.

- Data Analysis: Double-reference the data (subtract signals from a reference flow cell and a blank buffer injection). Fit the resulting sensoryrams globally to a 1:1 binding model using the instrument's software to obtain kon and koff.

Quantitative Structure-Kinetics Relationship (QSKR) Modeling

For projects involving many ligands, machine learning models can predict kinetics, enabling large-scale virtual screening [20].

Methodology:

- Data Set Curation: Compile a data set of known inhibitors with experimentally measured k_off values (e.g., from SPR). The example from the search results used 132 inhibitors of HSP90α [20].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors for each compound, which are numerical representations of structural and chemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, hydrogen bond capacity).

- Model Training & Validation: Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest) to build a model that correlates the molecular descriptors with the k_off values. The model's performance is then validated on a test set of compounds not used in training [20].

Table 2: Representative Kinetic and Affinity Data for HSP90α Inhibitors (as cited in PMC11040708)

| Scaffold Type | Number of Compounds | Reported k_off Range (s⁻¹) | Reported K_d Range (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxy-indazole | 55 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Resorcinol | 48 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Amino-quinazoline | 13 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Model Performance | Metric | Value | |

| QSKR Model (Test Set) | R² (Determination Coefficient) | 0.93 | |

| QSKR Model (Test Set) | MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | 0.18 (log units) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and computational tools used in advanced binding studies, as identified in the search results.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Computational Solutions for Binding Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Instrumentation | Label-free, real-time measurement of binding kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (K_d). | High-throughput SPR (HT-SPR) [19] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Instrumentation | Directly measures the enthalpy change (ΔH), stoichiometry (N), and K_d of a binding interaction. | [23] |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Instrumentation | Provides high-resolution 3D structures of protein-ligand complexes without crystallization. | Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries [19] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computational | Models the dynamic process of ligand association/dissociation and conformational changes at atomic resolution. | [20] [23] |

| Protein-Ligand Docking Software | Computational | Predicts the binding pose and estimates the affinity of a ligand within a target binding site. | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD [22] |

| AlphaFold 3 / RosettaFold All-Atom | Computational (AI) | Deep learning models that predict the 3D structure of protein-ligand complexes from primary sequences. | [19] |

| Quantitative Structure-Kinetics Relationship (QSKR) | Computational (ML) | Machine learning models that predict kinetic parameters (e.g., k_off) from ligand structures. | [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my assay showing high background noise in the positive control? High background noise is often due to non-specific binding or insufficient blocking. Ensure your blocking buffer is fresh and that you are using a highly specific primary antibody. Re-optimize the antibody concentration and increase the number of wash steps to reduce non-specific signals.

Q2: How can I confirm that my lead compound is binding to the intended target and not a common off-target? Employ a orthogonal binding assay, such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) alongside the primary biochemical assay. SPR can provide real-time kinetic data (ka, kd) to confirm binding to the primary target and can be used to screen against a panel of known homologous off-targets.

Q3: My compound has excellent binding affinity but poor cellular efficacy. What could be the cause? This discrepancy often indicates poor cell permeability or efflux by membrane transporters. To troubleshoot, check the compound's logP to estimate permeability and run an assay in the presence of a transporter inhibitor like Verapamil. Also, confirm target engagement in the cellular context using a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA).

Q4: What is the best way to visualize the selectivity profile of a compound across multiple related targets? The most effective method is to generate a selectivity wheel or a heatmap. Plot the percentage inhibition or binding affinity (Ki/IC50) of your compound against a panel of critical off-targets. This provides an immediate, visual representation of the compound's selectivity landscape.

Q5: How many off-targets should be included in a standard selectivity panel? A robust early-stage panel should include at least 20-50 targets that are highly homologous to your primary target or are known for mediating adverse effects. This often includes GPCRs, kinases, ion channels, and nuclear receptors relevant to your therapeutic area.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Kinetic Binding Analysis via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Objective: To determine the association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rates of a lead compound for the primary target and critical off-targets.

- Immobilization: Dilute the purified target protein to 10 µg/mL in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Inject over a CMS sensor chip to achieve a immobilization level of 5-10 kRU using standard amine-coupling chemistry.

- Ligand Injection: Prepare a 3-fold serial dilution of the compound in running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP+). Inject each concentration over the target and reference surfaces for 2 minutes at a flow rate of 30 µL/min.

- Dissociation Phase: Monitor the dissociation of the compound in running buffer for 5 minutes.

- Regeneration: Regenerate the chip surface with a 30-second pulse of 10 mM Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0).

- Data Analysis: Double-reference the sensorgrams (reference surface and buffer blank). Fit the data to a 1:1 binding model using the SPR evaluation software to calculate ka and kd. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated as kd/ka.

Protocol 2: Cellular Target Engagement via Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

Objective: To confirm that the compound binds to its intended target in a live-cell environment.

- Cell Treatment: Seed cells expressing the target protein in T75 flasks. At 80% confluency, treat cells with 10 µM of the test compound or DMSO vehicle control for 2 hours.

- Heat Challenge: Harvest cells, wash with PBS, and aliquot into PCR tubes. Heat each aliquot at a range of temperatures (e.g., 37°C to 65°C) for 3 minutes in a thermal cycler.

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells and solubilize proteins with a freeze-thaw cycle using liquid nitrogen.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the lysates to separate soluble protein. Analyze the soluble fraction for the target protein levels via Western Blotting. Quantify band intensity; a leftward shift in the protein melting curve for the compound-treated sample indicates successful target engagement and thermal stabilization.

Table 1: Lead Compound Binding Affinity and Selectivity Profile

| Target / Off-Target | Protein Class | Binding Affinity (KD in nM) | Selectivity Fold (vs. Primary) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Target (PT) | Kinase | 5.2 | 1 |

| Off-Target Kinase A | Kinase | 18.1 | 3.5 |

| Off-Target Kinase B | Kinase | 510.0 | 98.1 |

| Critical Off-Target C | GPCR | >10,000 | >1,900 |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Selectivity Assays

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| HEK293T Cell Line | A mammalian cell line engineered to overexpress the human primary target protein, used for cellular and binding assays. |

| Anti-His Tag HRP Antibody | A conjugated antibody that binds to polyhistidine tags on recombinant proteins, enabling detection in ELISA and Western Blot. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | A transfection reagent used to introduce plasmid DNA encoding the target protein into mammalian cells for transient expression. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | A solution of various inhibitors added to cell lysis buffers to prevent the degradation of proteins during extraction. |

| AlphaScreen Detection Kit | A bead-based chemiluminescent assay technology used for studying biomolecular interactions in a high-throughput format. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

On-Target Verification Workflow

Off-Target Signaling Pathway

Strategic Methodologies for Optimizing Binding Parameters

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when applying COMBINE (COMparative BINding Energy) analysis to predict drug-target residence times and develop Quantitative Structure-Kinetics Relationship (QSKR) models.

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using COMBINE analysis for predicting residence time over traditional QSAR approaches?

Traditional QSAR models often focus solely on predicting binding affinity (KD), which is an equilibrium property. However, drug efficacy and duration of action are increasingly recognized to correlate better with target residence time [24]. COMBINE analysis extends beyond traditional approaches by deconstructing the interaction energies between a ligand and its target, allowing researchers to identify which specific residue interactions are most critical for dissociation rates (koff). This provides a mechanistic understanding of binding kinetics, which is essential for optimizing drug residence time and selectivity [25] [26].

FAQ 2: My COMBINE model shows good predictive ability for a congeneric series but fails for diverse compounds. What could be the cause?

This is a common limitation. COMBINE analysis was originally developed for congeneric series where ligands share a common scaffold [26]. The model's performance can degrade with highly diverse data sets because it primarily analyzes the bound state of the protein-ligand complex. Variations in the unbound state or fundamentally different dissociation pathways among diverse scaffolds introduce complexity that the standard model may not capture. For diverse compound sets, consider integrating descriptors from dissociation trajectories or using machine learning on interaction fingerprints to improve robustness [26].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the predictive robustness of my residence time estimates when using computational methods?

Integrating multiple sources of information and methodologies can significantly enhance robustness. Key strategies include:

- Combine with Machine Learning: Use protein-ligand interaction fingerprints from molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories as features for machine learning models. This can help overcome inaccuracies from force fields or docking poses [26].

- Multi-Method Approach: Augment COMBINE with other analyses, such as Protein Interaction Property Similarity Analysis (PIPSA), to evaluate and predict target selectivity [25].

- Leverage Enhanced Sampling: For absolute residence time prediction, combine COMBINE with enhanced sampling MD techniques, like τRAMD or metadynamics, to gain insights into dissociation pathways and energy barriers [26].

FAQ 4: What are the common pitfalls in docking that can adversely affect a subsequent COMBINE analysis for kinetics?

A primary pitifact is the inaccuracy of docking solutions. COMBINE models are built on the structures of protein-ligand complexes. If the docked pose is incorrect or does not represent the true binding mode, the interaction energy decomposition will be flawed, leading to poor prediction of residence time and selectivity [25]. Always validate docking protocols with known crystallographic structures where possible.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Computational Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor correlation between computed interaction energies and experimental residence times. | The computed model is based on an inaccurate protein-ligand complex structure. | Verify the docking pose with experimental data (e.g., X-ray crystal structure). Consider using an ensemble of protein conformations for docking [25]. |

| Model fails to predict target selectivity. | The model may not adequately capture key residue interactions unique to each target. | Perform a comparative COMBINE analysis on complexes with all relevant targets (e.g., thrombin, trypsin, uPA) to identify specificity-determining residues [25]. |

| Inaccurate relative residence times from τRAMD simulations. | Underlying force field inaccuracies or insufficient sampling of dissociation pathways. | Implement a machine learning regression model on the protein-ligand interaction fingerprints from the τRAMD trajectories to correct the estimates [26]. |

| Difficulty in predicting residence time for new scaffolds. | The QSKR model is over-fitted to the chemical space of the training set. | Incorporate features that describe the dissociation pathway, such as interaction fingerprints from the first half of steered MD trajectories, which are crucial for kinetics [26]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Methodology: COMBINE Analysis for Residence Time Prediction

The following protocol outlines the steps for developing a COMBINE model to predict drug-target residence time, based on established approaches in the literature [25] [26].

1. Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Ligand Selection: Compile a set of ligands with experimentally measured kinetic parameters (e.g., koff, residence time τ). For initial method development, a congeneric series is recommended.

- Protein-Ligand Complexes: Obtain or generate high-quality 3D structures of the protein-ligand complexes. These can come from X-ray crystallography or from molecular docking followed by careful validation.

2. Interaction Energy Decomposition

- Energy Calculation: For each minimized protein-ligand complex, calculate the intermolecular interaction energy using a molecular mechanics force field.

- Decomposition: Break down the total interaction energy into contributions from individual protein residues and, optionally, ligand atoms. This creates a vector of energy descriptors for each complex.

3. Model Building with Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression

- Descriptor Matrix (X): The decomposed residue-ligand interaction energies for all complexes form the X-matrix.

- Response Vector (Y): The experimental logarithmic values of residence time (log τ) or dissociation rate (log koff) form the Y-vector.

- PLS Regression: Apply PLS regression to the X and Y data to build the COMBINE model. PLS is effective for handling the collinearity present in the energy descriptors. The model identifies which residue interaction energies are most weighted for predicting the kinetic parameter.

4. Model Validation

- Internal Validation: Use cross-validation techniques (e.g., leave-one-out, bootstrapping) to assess the model's robustness and prevent overfitting.

- External Validation: Test the model's predictive power on a set of compounds that were not used in the training phase.

Enhanced Workflow: Integrating Machine Learning with Dissociation Trajectories

For more robust predictions, especially with diverse ligands, the following enhanced protocol is recommended [26].

1. Generate Dissociation Trajectories

- Use an enhanced sampling method, such as τRAMD (random acceleration molecular dynamics), to simulate multiple ligand dissociation pathways for each compound. This method applies a small, randomly oriented force to the ligand to accelerate egress.

2. Extract Interaction Fingerprints

- From the hundreds of snapshots in each τRAMD trajectory, compute an interaction fingerprint for each snapshot. This fingerprint is a binary or quantitative representation of the contacts (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) between the ligand and key protein residues.

3. Build a Machine Learning Model

- Use the interaction fingerprints from the trajectories as features.

- Train a regression model (e.g., Support Vector Regression) to predict the experimental residence time. The model learns which interaction patterns along the dissociation path correlate with longer or shorter residence times.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and resources used in the development of QSKR models for residence time prediction.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| COMBINE Analysis | A computational method that decomposes protein-ligand interaction energies into residue-based contributions to create predictive models for binding affinity and kinetics [25]. |

| τRAMD (random acceleration MD) | An enhanced molecular dynamics simulation method used to estimate relative residence times and explore ligand egress pathways by applying a random accelerating force [26]. |

| Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints | A numerical representation of the interactions between a ligand and a protein binding site, used as features in machine learning models to predict residence time [26]. |

| GOLD / Other Docking Software | Molecular docking programs used to generate predicted structures of protein-ligand complexes, which serve as input structures for COMBINE analysis and other structure-based methods [25]. |

| PLS Regression | A statistical projection method used in COMBINE and other QSAR/QSKR models to correlate a large number of collinear descriptors (e.g., interaction energies) with a biological activity [25] [26]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

COMBINE QSKR Workflow

Residence Time Optimization Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My protein-ligand complex crystallizes poorly, making it difficult to obtain high-resolution X-ray structures. What are my alternatives? A: Solution-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a powerful alternative that does not require crystallization [27]. NMR-SBDD provides reliable structural information in solution, closely resembling the native state of protein-ligand complexes. This is particularly useful for proteins with inherent flexibility, flexible linkers, or post-translational modifications that hinder crystallization [27]. Advanced computational workflows can then generate accurate protein-ligand ensembles from the NMR data.

Q2: How can I visualize hydrogen bonding and other key interactions that X-ray crystallography might miss? A: X-ray crystallography is "blind" to hydrogen atoms, making it difficult to infer key interactions like hydrogen bonds [27]. NMR spectroscopy provides direct access to this information. The 1H chemical shift in NMR directly reports on the nature of hydrogen-bonding, allowing you to identify hydrogen bond donors and characterize interactions with aromatic ring systems (e.g., CH-π interactions) [27]. This provides a more complete picture of the binding interactions.

Q3: My experimental structure has ambiguous electron density for my ligand. How can I generate a reliable binding pose? A: Computational tools can resolve this uncertainty. You can dock ligands into ambiguous density, such as in cryo-EM structures, using physics-based force fields to determine the most likely pose [28]. Furthermore, computational refinement can be used to generate improved protein structures with better quality and statistics without the need for explicit ligand restraint files [28].

Q4: How can I account for protein dynamics and conformational ensembles in my structure-based design? A: Unlike X-ray crystallography, which provides a static snapshot, NMR spectroscopy can elucidate the dynamic behavior of ligand-protein complexes [27]. For larger systems, advanced computational workflows combine cryo-EM data with weighted ensemble molecular dynamics (WEMD) simulations. These simulations explore conformational landscapes to identify the best-fit protein conformers, creating ensembles that represent the protein's dynamic state [29].

Q5: A significant number of bound water molecules are not visible in my crystal structure. How does this impact my design? A: Approximately 20% of protein-bound waters are not X-ray observable [27]. These hidden water molecules can be crucial for understanding the thermodynamics of binding and hydration networks. Computational structure preparation tools can help address this by rationally placing cofactors and solvent molecules to convert low-resolution models into complete, all-atom representations, providing a more accurate model for design [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Protein-Ligand Structure Determination via NMR-SBDD

This protocol outlines the use of solution-state NMR spectroscopy for determining protein-ligand complex structures, a method that bypasses the need for crystallization [27].

Protein Expression and Labeling:

- Express the target protein in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli).

- Incorporate stable isotopes using selective 13C-labeled amino acid precursors. This selective side-chain labeling simplifies NMR spectra and provides specific probes for detecting ligand interactions [27].

Sample Preparation:

- Purify the protein using standard chromatography techniques (e.g., affinity, size exclusion).

- Prepare an NMR sample containing the protein in a suitable buffer. A separate sample with the protein and ligand is also prepared.

- The sample is placed in a high-field NMR spectrometer for data collection.

NMR Data Collection:

- Perform a suite of NMR experiments to obtain atomistic information. Key experiments include Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP) to identify the ligand binding site.

- Collect Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) data between the protein and ligand to determine distances between atoms, which are critical for defining the binding pose.

Structure Calculation and Validation:

- Use the NMR-derived constraints (e.g., chemical shifts, NOEs) in computational workflows to generate an ensemble of protein-ligand structures.

- Validate the final structural ensemble using standard geometric checks and by ensuring it is consistent with the original experimental data.

Protocol 2: Computational Refinement and Ligand Placement into Cryo-EM Maps

This protocol describes a computational approach for building and refining protein-ligand models into cryo-EM density maps [28] [29].

Data and Model Preparation:

- Obtain the cryo-EM density map (e.g., from homogeneous refinement) and an initial protein structure (experimental or AI-derived).

- Prepare the ligand structure, ensuring correct protonation states and stereochemistry.

Docking and Pose Generation:

- Use molecular docking tools within a structural biology platform to generate multiple potential ligand binding poses within the cryo-EM density.

- The physics-based force field will score these poses, helping to resolve ambiguity in the electron density [28].

Structure Refinement:

- Apply energy minimization and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to refine the protein-ligand complex. This step improves stereochemistry and the fit of the model within the cryo-EM density.

- Tools can be used to automatically build unresolved side-chain atoms and place missing solvent molecules during this process [28].

Ensemble Generation (Optional):

- For advanced analysis, use Weighted Ensemble MD (WEMD) simulations guided by the cryo-EM map. This explores the conformational landscape to generate an ensemble of protein conformers consistent with the experimental data [29].

Model Validation:

- Use built-in validation tools to check the geometry of the final model and its correlation with the cryo-EM density map.

Research Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for structure-based drug design, highlighting the complementary roles of NMR and computational refinement.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and materials used in the experimental protocols for structure-based design.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Selectively 13C-Labeled Amino Acids | Simplifies NMR spectra by providing specific probes in the protein, enabling precise detection of ligand-binding interactions and structural changes [27]. |

| NMR Buffer Components (e.g., D2O, Salts) | Maintains protein stability and function in solution during NMR data collection; D2O enables lock signal for the NMR spectrometer. |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Act as a support for vitrified, hydrated protein samples during data collection in the electron microscope. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Computationally predicts the orientation and pose of a small molecule (ligand) within a target protein's binding site [28]. |

| Weighted Ensemble MD (WEMD) Simulation Platform | Efficiently explores a wide range of protein conformations and identifies structures consistent with experimental data like cryo-EM maps, capturing rare events critical for drug discovery [29]. |

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in leveraging DNA-Encoded Libraries (DEL) and Click Chemistry to accelerate hit identification and optimization in drug discovery. These technologies are powerful tools for probing vast chemical spaces and engineering specific molecular interactions, directly supporting a research thesis focused on optimizing binding affinity and selectivity [30] [5]. DEL technology allows for the affinity-based screening of libraries containing billions of small molecules in a single experiment, while click chemistry provides efficient and reliable reactions to construct these libraries and conjugate molecular fragments [30] [31]. The following guides and FAQs address common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

DNA-Encoded Libraries (DEL)

Q1: Our DEL selections yield a high number of hits, but many prove to be non-specific binders or false positives. How can we improve the specificity of our selections?

- A: Non-specific binding is a common challenge. Implement these strategies to enhance specificity:

- Pre-blocking: Pre-incubate the library with the solid support (e.g., streptavidin beads) and any non-immobilized tag (e.g., biotin) to deplete beads-binding and tag-binding species [30].

- Counter-Selections: Perform a pre-clearing step by incubating the DEL with a non-target protein or a protein with a similar binding site but where selectivity is desired. This depletes library members that bind non-specifically or to unwanted epitopes [5].

- Stringent Washing: Optimize wash conditions. Include mild denaturants (e.g., low concentrations of urea), detergents (e.g., Tween-20), and high salt concentrations to disrupt weak, non-specific interactions without eluting high-affinity binders [30] [32].

- Competitive Elution: Elute binders using a known high-affinity ligand for the target. This competitively displaces specific binders, enriching for ligands that bind to the desired active site [5].

Q2: What are the primary strategies for constructing a DEL, and how do we choose? [30] [33]

- A: The two main encoding strategies are DNA-Recorded and DNA-Templated synthesis. The choice depends on your library design goals and synthetic capabilities.

Table: Key DEL Encoding Strategies

Strategy Description Key Feature DNA-Recorded (Split & Pool) Chemical building blocks are attached in iterative cycles; a DNA barcode is ligated after each step to record the reaction history [30] [33]. Ideal for creating large, diverse single-pharmacophore libraries (billions of compounds). DNA-Templated DNA hybridization brings reactant molecules into proximity to direct chemical reactions between them [30]. Useful for synthesizing more complex macrocyclic or threaded structures. Dual-Pharmacophore Two different chemical moieties are attached to the extremities of complementary DNA strands, enabling fragment-based discovery approaches [30] [32]. Allows screening of fragment pairs that bind synergistically.

Q3: Why is our DEL synthesis yield low, and how can we improve it?

- A: Low yield often stems from incomplete chemical reactions or DNA damage.

- DNA-Compatible Chemistry: Ensure all synthetic steps use conditions that do not degrade DNA (e.g., avoid strong acids, heavy metals, and nucleophiles at high temperatures) [30]. A growing toolkit of DNA-compatible reactions is available.

- Reagent Excess: Use a large excess of reagents and building blocks to drive reactions to completion, minimizing truncated sequences [30].

- Purification: After each synthesis step, implement robust purification (e.g., HPLC, size-exclusion chromatography) to remove excess reagents and byproducts before proceeding to the next step [33].

Click Chemistry

Q4: Our copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction with a biomolecule is inefficient and leads to protein degradation. How can we optimize it? [34]

- A: This is typically caused by copper-induced oxidative damage. Optimization requires controlling the copper catalytic cycle.

- Use a Ligand: Employ a stabilizing ligand like THPTA (tris(3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl)amine). The ligand accelerates the reaction and acts as a sacrificial reductant, protecting biomolecules from reactive oxygen species generated in situ [34]. A 5:1 molar ratio of ligand to copper is often optimal.

- Fresh Reducing Agent: Always prepare a fresh sodium ascorbate solution immediately before use to ensure a strong reducing environment that maintains copper in the active +1 oxidation state [34].

- Consider Additives: Adding aminoguanidine (5 mM) can suppress side reactions between ascorbate byproducts and protein arginine residues [34].

- Metal-Free Alternatives: For highly sensitive systems, use strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) with cyclooctyne reagents. This eliminates copper entirely, though reaction kinetics are generally slower [35].

Q5: How do we quantify the efficiency of a click chemistry bioconjugation reaction? [34]

- A: For troubleshooting, use a fluorogenic assay to monitor reaction progress.

- Use a model small-molecule alkyne (e.g., propargyl alcohol) and the coumarin azide 3 under your standard reaction conditions to establish a 100% conversion fluorescence baseline [34].

- Run the same reaction with your biomolecule-alkyne under identical conditions.

- Compare the fluorescence intensity of the test reaction to the baseline to estimate the reaction efficiency. This pre-testing helps optimize conditions before using valuable biological reagents [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their roles in DEL and Click Chemistry workflows.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for DEL and Click Chemistry

| Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| DNA Oligonucleotides | Serves as the amplifiable barcode in DEL; provides the scaffold for DNA-templated synthesis [30] [33]. |

| Building Blocks (BBs) | The chemical units (e.g., carboxylic acids, amines, aldehydes) used to construct the diverse small molecules in a DEL [30]. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Beads | A common solid support for immobilizing biotinylated protein targets during DEL affinity selections [30] [32]. |

| Sodium Ascorbate | The most common reducing agent in CuAAC, maintaining catalytic copper in the Cu(I) state [34]. |

| THPTA Ligand | A key accelerating and protective ligand for CuAAC, crucial for maintaining biomolecule integrity [34]. |

| Azide & Alkyne Building Blocks | Functional groups for Click Chemistry; used in library synthesis (DEL) and bioconjugation (e.g., attaching fluorophores) [35] [31]. |

| DBCO / Cyclooctyne Reagents | Reagents for copper-free, strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC), used when copper cytotoxicity is a concern [35]. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

▷ DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Selection Workflow

▷ Click Chemistry for Bioconjugation

Quantitative Data and Protocols

This protocol is optimized for conjugating an azide-modified cargo to an alkyne-modified biomolecule.

Final Reaction Conditions:

- Biomolecule-Alkyne: 50 µM (concentration can be adjusted)

- Cargo-Azide: 2-fold excess (e.g., 100 µM)

- CuSO₄: 0.10 mM

- THPTA Ligand: 0.50 mM (5:1 ligand:copper ratio)

- Sodium Ascorbate: 5 mM (freshly prepared)

- Aminoguanidine: 5 mM (optional, to protect protein)

- Buffer: 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0

Procedure:

- In a 2 mL tube, combine the biomolecule-alkyne and buffer to a final volume of 432.5 µL.

- Add 10 µL of the cargo-azide stock solution.

- Add a pre-mixed solution of 2.5 µL of 20 mM CuSO₄ and 5.0 µL of 50 mM THPTA.

- Add 25 µL of 100 mM aminoguanidine.

- Initiate the reaction by adding 25 µL of 100 mM sodium ascorbate.

- Close the tube, mix thoroughly, and allow the reaction to proceed for 1 hour with gentle mixing.

- Stop the reaction and remove copper ions by dialysis or buffer exchange into a solution containing EDTA.

DEL Performance Metrics

Table: Characterizing DEL Size and Selection Outcomes

| Metric | Description | Typical Range / Value |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | Total number of unique compounds in the library. | Thousands to hundreds of billions [30] [32]. |

| Building Blocks per Cycle | Number of distinct chemical inputs at each synthesis step. | n (1st cycle), m (2nd cycle), etc. [30]. |

| Sequencing Depth | Number of DNA sequence reads required to reliably identify enriched compounds. | Millions to billions of reads [30]. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | Fold-increase in frequency of a library member after selection compared to its frequency in the original library. | >10-100x for high-affinity binders [32]. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource is designed to help researchers navigate the experimental complexities of developing multivalent binders. The following guides and FAQs address common challenges, providing troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to optimize the binding affinity and selectivity of your constructs.

Core Concepts of Avidity and Multivalency

What is the difference between affinity and avidity?

- Affinity refers to the binding strength of a single, monovalent interaction between a ligand and its receptor, quantified by the dissociation constant (Kd) [36].

- Avidity is the accumulated, overall binding strength resulting from multiple simultaneous interactions between multivalent molecules. It is a phenomenological macroscopic parameter that can be several orders of magnitude stronger than the sum of the individual affinities [36].

How does multivalency enhance selectivity? Multivalency enables binders to sense both antigen identity and density on cell surfaces [37].

- A multivalent construct (e.g., a bivalent binder targeting antigens A and B) can be designed to bind strongly only when both targets are present, creating an AND-gate effect [37].

- It can also distinguish between cells expressing high versus low densities of the same antigen, a principle crucial for targeting overexpressed disease markers while sparing healthy tissues [37] [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My multivalent binder shows irreversible binding in BLI/SPR experiments. What is the cause and how can I resolve it?

- Cause: This is a common artifact in surface-based techniques like BLI and SPR. At high protein immobilization densities, multivalent binders (especially higher-order architectures like tetramers and octamers) can become irreversibly entangled or cross-linked between adjacent immobilized proteins. This leads to avidity effects that prevent accurate measurement of the dissociation rate (koff) [39] [40].

- Solution:

- Reduce Immobilization Density: Lower the density of the target protein on the biosensor surface. However, this can sometimes lead to a poor signal-to-noise ratio [39].