Open Access In Silico Tools for ADMET Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of open-access in silico tools for ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling, a critical component in modern drug...

Open Access In Silico Tools for ADMET Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Developers

Abstract

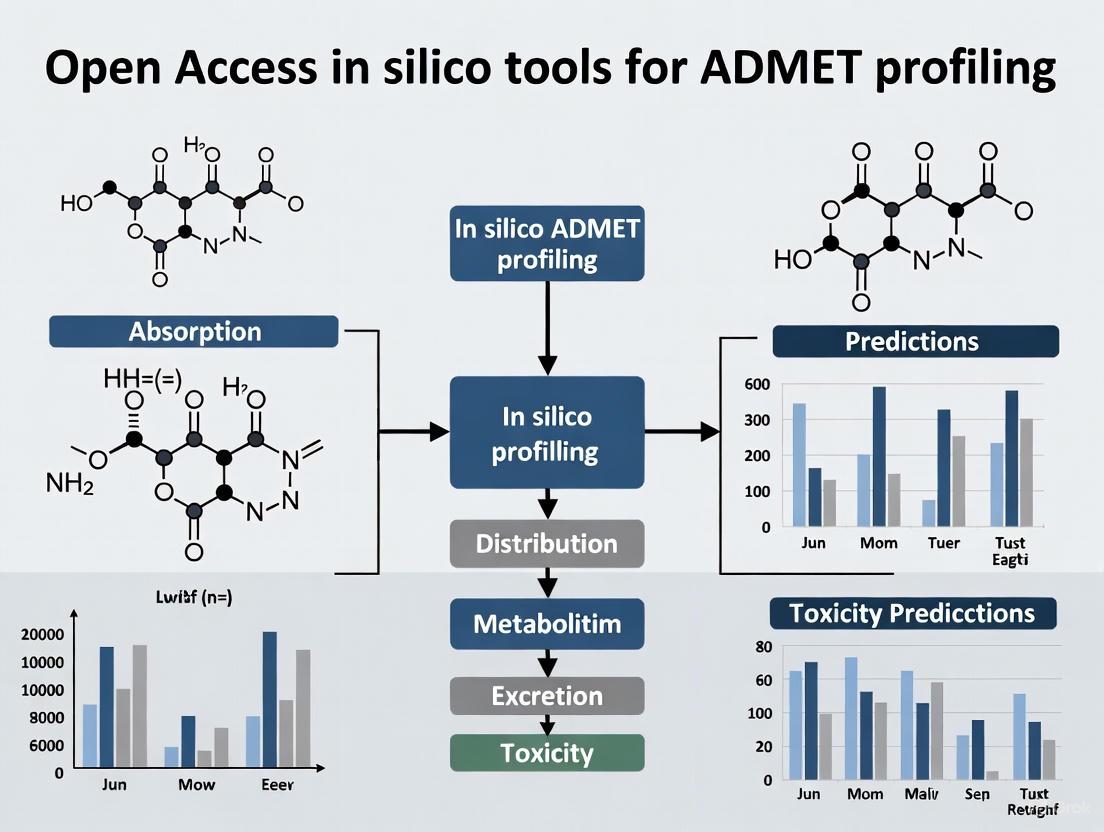

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of open-access in silico tools for ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling, a critical component in modern drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of ADMET prediction, explores the methodology behind key computational platforms like ChemMORT and PharmaBench, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging compounds. Furthermore, it delivers a critical validation and comparative analysis of available tools based on recent benchmarking studies, empowering scientists to make informed decisions to accelerate the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

Understanding ADMET and the Rise of Open Access Predictive Tools

Why ADMET Properties are Crucial for Drug Development Success and Failure

The journey of a drug candidate from discovery to market is a complex, costly, and high-risk endeavor. A critical determinant of clinical success lies in a compound's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Despite technological advancements, drug development continues to be plagued by substantial attrition rates, with suboptimal pharmacokinetics and unforeseen toxicity accounting for a significant proportion of late-stage failures [1] [2]. Historically, ADMET assessment relied heavily on labor-intensive and low-throughput experimental assays, which are difficult to scale alongside modern compound libraries [3]. The emergence of open-access in silico tools and advanced machine learning (ML) models has revolutionized this landscape, offering rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives for early risk assessment [1] [4]. This whitepaper examines the pivotal role of ADMET properties in drug development success and failure, framed within the context of computational profiling and open science initiatives that are enhancing predictive accuracy and regulatory acceptance.

The Critical Role of ADMET in Drug Attrition

Late-stage failure of drug candidates represents one of the most significant financial and temporal sinks in pharmaceutical research. Analyses indicate that approximately 40–45% of clinical attrition is directly attributable to ADMET liabilities, particularly poor human pharmacokinetics and safety concerns [2] [5]. These failures often occur after hundreds of millions of dollars have already been invested in discovery and early development, underscoring the economic imperative for earlier and more accurate prediction.

Table 1: Primary Causes of Drug Candidate Attrition in Clinical Development

| Attrition Cause | Approximate Contribution | Primary Phase of Failure |

|---|---|---|

| ADMET Liabilities (Poor PK/Toxicity) | 40-45% | Preclinical to Phase II |

| Lack of Efficacy | ~30% | Phase II to Phase III |

| Strategic Commercial Reasons | ~15% | Phase III to Registration |

| Other (e.g., Formulation) | ~10-15% | Various |

Balancing ideal ADMET characteristics is a fundamental challenge in molecular design. Key properties include:

- Absorption: Governs the rate and extent of drug entry into systemic circulation, influenced by permeability, solubility, and interactions with efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein [2].

- Distribution: Determines drug dissemination to tissues and organs, affecting both therapeutic targeting and off-target effects [2].

- Metabolism: Describes biotransformation processes, primarily by hepatic enzymes, which influence drug half-life, clearance, and potential for drug-drug interactions [3] [2].

- Excretion: Facilitates the clearance of the drug and its metabolites, impacting the duration of action and potential accumulation [2].

- Toxicity: Encompasses a range of adverse effects, with cardiotoxicity (e.g., hERG inhibition) and hepatotoxicity being major causes of candidate failure and post-market withdrawal [3].

Traditional ADMET assessment, which depends on in vitro assays and in vivo animal models, struggles to accurately predict human in vivo outcomes due to issues of species-specific metabolic differences, assay variability, and low throughput [3] [2]. This predictive gap has driven the urgent need for more robust, scalable, and human-relevant computational methodologies.

The Rise of In Silico ADMET Prediction

Computational, or in silico, ADMET prediction has emerged as an indispensable tool in early drug discovery. These approaches leverage quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and, more recently, sophisticated machine learning (ML) algorithms to decipher complex relationships between a compound's chemical structure and its biological properties [1] [2]. The primary advantage is the ability to perform high-throughput screening of virtual compound libraries, prioritizing molecules with a higher probability of clinical success and reducing the experimental burden [1].

Key Machine Learning Methodologies

The field has evolved from using simple molecular descriptors to employing advanced deep learning architectures:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These models directly operate on the molecular graph structure, inherently capturing atomic connectivity and bonding patterns to learn complex features relevant to biological activity [2] [6]. Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs), as implemented in tools like Chemprop, are a prominent example [7].

- Multitask Learning (MTL): This framework trains a single model to predict multiple ADMET endpoints simultaneously. By learning from correlated tasks, MTL models often demonstrate improved generalization and data efficiency compared to single-task models [3] [2].

- Ensemble Learning: Methods like Random Forest and gradient-boosting frameworks (e.g., LightGBM, CatBoost) combine predictions from multiple base models to enhance overall accuracy and robustness [7] [2].

- Federated Learning: This emerging paradigm allows for collaborative model training across distributed, proprietary datasets from multiple pharmaceutical organizations without sharing confidential data. This significantly expands the chemical space a model can learn from, leading to superior performance and generalizability [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Common ML Models and Representations in ADMET Prediction

| Model Type | Example Algorithms | Typical Molecular Representations | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical ML | Random Forest, SVM, LightGBM | Molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan), RDKit 2D descriptors | High interpretability, computationally efficient, performs well on small datasets |

| Deep Learning (Graph-based) | MPNN (Chemprop), GNN | Molecular graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) | Learns features automatically, no need for manual feature engineering |

| Deep Learning (Other) | Multitask DNN, Transformer | SMILES strings, learned embeddings (e.g., Mol2Vec) | Can handle massive datasets, suitable for transfer learning |

| Ensemble/Hybrid | Stacking, Receptor.AI's approach | Combined fingerprints, descriptors, and graph features | Often achieves state-of-the-art performance, robust to overfitting |

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for developing and applying a machine learning model for ADMET prediction, highlighting the critical steps from data collection to prospective validation.

ML Model Development Workflow

The Centrality of Data Quality and Curation

A critical insight from recent research is that model performance is often limited more by data quality and diversity than by the choice of algorithm [7] [8]. Key data challenges include:

- Inconsistent Measurements: Experimental results for the same compound can vary significantly between labs due to differences in assay protocols, buffers, and pH levels [9].

- Data Cleanliness: Public datasets often suffer from inconsistent SMILES representations, duplicate entries with conflicting values, and the presence of inorganic salts or organometallic compounds that need filtering [7].

- Limited Chemical Space: Many public benchmarks contain compounds that are not representative of the chemical space explored in industrial drug discovery (e.g., lower molecular weight) [9].

Initiatives like OpenADMET and PharmaBench are addressing these issues by generating high-quality, consistent experimental data specifically for model development and by creating more relevant, large-scale benchmarks using advanced data-mining techniques, including multi-agent Large Language Model (LLM) systems to extract experimental conditions from scientific literature [8] [9].

Essential Methodologies: Protocols for Robust ADMET Modeling

This section details the experimental and computational protocols that underpin reliable ADMET prediction, providing a guide for researchers.

Data Preprocessing and Cleaning Protocol

A rigorous data cleaning pipeline is a prerequisite for building trustworthy models. A recommended protocol, as detailed in benchmarking studies, involves the following steps [7]:

- SMILES Standardization: Use tools like the standardisation tool by Atkinson et al. to generate consistent SMILES representations, adjust tautomers, and extract the organic parent compound from salt forms [7].

- Removal of Inorganics and Organometallics: Filter out compounds containing non-organic elements or metal atoms that are not relevant for small-molecule drug discovery.

- Deduplication: Identify duplicate compounds and keep the first entry if target values are consistent. If values are inconsistent (e.g., different binary labels for the same SMILES), remove the entire group to avoid noise.

- Visual Inspection: For smaller datasets, use tools like DataWarrior to visually inspect the resultant clean datasets and identify any remaining anomalies [7].

Model Training and Evaluation Protocol

To ensure model robustness and generalizability, a structured evaluation strategy is crucial.

- Data Splitting: Implement scaffold-based splitting (e.g., using the DeepChem library) to separate training and test sets based on molecular Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This tests the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes, simulating a real-world scenario [7].

- Feature Selection: Systematically evaluate different molecular representations (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, RDKit descriptors, Mordred descriptors, graph embeddings) and their combinations. Avoid simply concatenating all features without statistical justification [7].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Tune model hyperparameters in a dataset-specific manner using cross-validation on the training set.

- Statistical Validation: Enhance evaluation by integrating cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., paired t-tests) to determine if performance differences between models are statistically significant, rather than relying on a single hold-out test score [7].

- External Validation: Evaluate the final model's performance on a hold-out test set from a different data source to assess its practical utility and generalizability [7].

The following diagram maps this structured approach, showing the logical progression from raw data to a validated model ready for prospective use.

Model Validation Strategy

Table 3: Essential In Silico Tools and Resources for ADMET Profiling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Generation of molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and basic molecular operations | Open Source |

| admetSAR | Web Server / Predictive Model | Predicts a wide array of ADMET endpoints from chemical structure | Open Access |

| ADMETlab | Web Server / Predictive Model | Integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive ADMET predictions (e.g., ADMETlab 2.0) | Open Access |

| Chemprop | Machine Learning Framework | Message Passing Neural Network for molecular property prediction, excels in multitask settings | Open Source |

| ProTox | Web Server / Predictive Model | Predicts various forms of toxicity (e.g., hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity) | Open Access |

| PharmaBench | Benchmark Dataset | A comprehensive, large-scale benchmark for ADMET model development and evaluation | Open Access |

| TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons) | Benchmark Dataset / Leaderboard | A collection of curated datasets and a leaderboard for benchmarking ADMET models | Open Access |

| Swiss Target Prediction | Web Server | Predicts the most probable protein targets of a small molecule | Open Access |

Case Study: Integrated In Silico Profiling of a Natural Product

A 2025 study on Karanjin, a natural furanoflavonoid, exemplifies the power of integrated in silico workflows for evaluating drug potential [10]. The research aimed to explore Karanjin's anti-obesity potential through a multi-stage computational protocol:

- ADMET Profiling: The canonical SMILES of Karanjin was retrieved from PubChem and used as input for multiple open-access prediction tools, including admetSAR, vNN-ADMET, and ProTox. The results indicated favorable absorption, distribution, and toxicity profiles, suggesting drug-like properties [10].

- Network Pharmacology: Targets of Karanjin were predicted using Swiss Target Prediction and SuperPred databases. Obesity-related genes were gathered from GeneCards, OMIM, and DisGeNet. A Venn diagram analysis identified 145 overlapping targets, which were then subjected to protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis. Enrichment analysis revealed significant pathways, including the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications [10].

- Molecular Docking: Karanjin was docked against eight hub proteins central to the obesity-related network (e.g., PIK3CA, STAT1, SRC). The results showed strong binding affinities, with Karanjin outperforming reference drugs in several cases. The PIK3CA-Karanjin complex demonstrated the most favorable interaction [10].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MDS): The stability of the PIK3CA-Karanjin complex was validated through 100 ns MDS. Metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radius of Gyration (Rg), and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) confirmed the complex's structural stability, and binding free energy calculations using the MM/PBSA method thermodynamically validated the interaction [10].

This end-to-end in silico pipeline provided a strong computational foundation for Karanjin as a multi-target anti-obesity candidate, showcasing how open-access tools can be systematically applied to de-risk and prioritize candidates for expensive experimental follow-up [10].

Regulatory Perspectives and Future Directions

Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA recognize the potential of AI/ML in ADMET prediction but require models to be transparent, well-validated, and built on high-quality data [3]. A significant step was taken in April 2025 when the FDA outlined a plan to phase out animal testing requirements in certain cases, formally including AI-based toxicity models under its New Approach Methodologies (NAM) framework [3]. This creates a pathway for using validated computational models in regulatory submissions.

Future progress in the field hinges on several key frontiers:

- Interpretability and Explainable AI (XAI): Overcoming the "black-box" nature of complex models is essential for building scientific and regulatory trust. Methods that provide clear attribution of predictions to specific molecular substructures are critical [3] [2].

- Federated Learning: Cross-pharma collaborative efforts, such as the MELLODDY project, have demonstrated that federation systematically expands a model's applicability domain and improves performance without compromising data privacy, representing a paradigm shift in how robust models are built [5].

- Integration of Multimodal Data: Enhancing models by integrating not just molecular structure but also pharmacological profiles, gene expression data, and even structural biology insights (e.g., from protein-ligand co-crystals) will increase clinical relevance [2] [8].

- Prospective Validation and Blind Challenges: Initiatives like the Polaris ADMET Challenge and OpenADMET are promoting rigorous, prospective evaluation of models through blind predictions, which is the ultimate test of real-world utility [5] [8].

ADMET properties are undeniably crucial gatekeepers in the drug development process. Failures related to pharmacokinetics and toxicity remain a primary cause of costly late-stage attrition. The integration of in silico tools, particularly those driven by advanced machine learning and open-science principles, is fundamentally transforming the assessment of these properties. By enabling early, rapid, and cost-effective profiling, these computational approaches empower researchers to prioritize lead compounds with a higher probability of clinical success. While challenges surrounding data quality, model interpretability, and regulatory acceptance persist, the ongoing advancements in algorithms, collaborative data generation, and rigorous benchmarking are steadily building a future where ADMET-related failures are significantly reduced, accelerating the delivery of safer and more effective therapeutics to patients.

The Role of QSAR Models in Predicting Physicochemical and Toxicokinetic Properties

In the contemporary landscape of drug discovery and chemical risk assessment, the evaluation of physicochemical (PC) and toxicokinetic (TK) properties is paramount. These properties directly influence a chemical's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profile. With increasing regulatory pressure to reduce animal testing, particularly in sectors like the cosmetics industry, and the constant drive to reduce attrition rates in drug development, in silico predictive tools have become indispensable [11] [12]. Among these, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models stand out as a powerful and widely adopted approach for predicting PC and TK properties based solely on the molecular structure of a compound. This whitepaper, framed within the context of open-access in silico tools for ADMET profiling research, provides an in-depth technical guide on the critical role of QSAR models in this field. It covers fundamental principles, benchmarked tools, detailed protocols, and practical applications, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of QSAR in PC and TK Prediction

QSAR models are founded on the principle that a quantifiable relationship exists between the chemical structure of a compound and its biological activity or physicochemical properties. For PC and TK prediction, this involves translating a molecular structure into numerical descriptors, which are then used as input variables in a mathematical model to predict specific endpoints.

The predictive accuracy of a QSAR model is not universal and is highly dependent on the Applicability Domain (AD). The AD defines the chemical space on which the model was trained and for which its predictions are considered reliable. Predictions for compounds falling outside the AD should be treated with caution. A comprehensive benchmarking study confirmed that models generally perform better inside their applicability domain and that qualitative predictions (e.g., classifying a compound as biodegradable or not) are often more reliable than quantitative ones when assessed against regulatory criteria [11] [13].

The reliability of a QSAR prediction hinges on multiple factors, including the quality and diversity of the training dataset, the algorithm used, and the molecular descriptors selected. As such, the scientific consensus is to use multiple in silico tools for predictions and compare the results to identify the most probable outcome [12].

Benchmarking of Computational Tools and Performance

The selection of appropriate software is critical for accurate ADMET prediction. A recent comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated twelve software tools implementing QSAR models for predicting 17 relevant PC and TK properties [13]. The study used 41 curated external validation datasets to assess the models' external predictivity, with an emphasis on performance within the applicability domain.

Table 1: Summary of Software Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Software Tool | Key Features | Representative Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| VEGA | Platform hosting multiple models for PC, TK, and environmental fate parameters; includes AD assessment [11]. | Ready Biodegradability IRFMN model for persistence; ALogP for Log Kow; Arnot-Gobas for BCF [11]. |

| EPI Suite | Comprehensive suite of PC and environmental fate prediction models [11]. | BIOWIN model for biodegradation; KOWWIN for Log Kow prediction [11]. |

| OPERA | Open-source QSAR model battery for PC properties, environmental fate, and toxicity; includes AD assessment [13]. | Relevant for predicting mobility (Log Koc) of cosmetic ingredients [11]. |

| ADMETLab 3.0 | Webserver for predicting ADMET properties; includes a wide array of endpoints [12]. | Found appropriate for Log Kow prediction in bioaccumulation assessment [11]. |

| Danish QSAR Model | Provides models like the Leadscope model for biodegradation prediction [11]. | High performance in predicting persistence of cosmetic ingredients [11]. |

| CORAL | Software using Monte Carlo optimization to build QSAR models from SMILES notation and graph-based descriptors [14]. | Used to develop models predicting anti-breast cancer activity of naphthoquinone derivatives [14]. |

The overall results confirmed the adequate predictive performance of the majority of selected tools. Notably, models for PC properties (average R² = 0.717) generally outperformed those for TK properties (average R² = 0.639 for regression, average balanced accuracy = 0.780 for classification) [13]. The following table summarizes the best-performing models for key properties as identified in recent comparative studies.

Table 2: High-Performing QSAR Models for Key PC and TK Properties

| Property Category | Specific Endpoint | Recommended QSAR Tools/Models |

|---|---|---|

| Persistence | Ready Biodegradability | Ready Biodegradability IRFMN (VEGA), Leadscope model (Danish QSAR Model), BIOWIN (EPISUITE) [11]. |

| Bioaccumulation | Log Kow (Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient) | ALogP (VEGA), ADMETLab 3.0, KOWWIN (EPISUITE) [11]. |

| Bioaccumulation | BCF (Bioconcentration Factor) | Arnot-Gobas (VEGA), KNN-Read Across (VEGA) [11]. |

| Mobility | Log Koc (Soil Adsorption Coefficient) | OPERA, KOCWIN-Log Kow estimation models (VEGA) [11]. |

Detailed Experimental and Modeling Protocols

Workflow for an Integrated QSAR and Computational ADMET Study

A typical workflow for using QSAR models in drug discovery or chemical safety assessment involves multiple, integrated steps, from data collection to final candidate selection. The following diagram illustrates this process, incorporating elements from several recent studies [14] [15].

Key Steps and Methodologies

Dataset Curation and Molecular Structure Input: The process begins with assembling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀) or property values. The inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) is often converted to pIC₅₀ (-log IC₅₀) for modeling [15]. Structures are typically represented as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) notations or 2D/3D structures. A critical curation step involves removing duplicates, neutralizing salts, and standardizing structures using toolkits like RDKit [13].

Descriptor Calculation: Molecular structures are translated into numerical descriptors that encode structural information. These can include:

- Electronic Descriptors: Calculated using quantum chemical methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory with B3LYP functional and 6-31G basis set). Examples include energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), dipole moment (μ), absolute electronegativity (χ), and absolute hardness (η) [15].

- Topological Descriptors: Calculated from the 2D molecular graph using software like ChemOffice. Examples include molecular weight (MW), octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP), water solubility (LogS), polar surface area (PSA), and Balaban Index (J) [15].

- Hybrid Descriptors: Advanced approaches use hybrid descriptors derived from both SMILES and hydrogen-suppressed graphs (HSG), which can improve prediction accuracy [14].

QSAR Model Development and Validation: The calculated descriptors serve as independent variables to build a model predicting the biological activity (dependent variable). Multiple algorithms are employed:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): A common technique used with descriptor selection methods like stepwise regression [15].

- Monte Carlo Optimization: Used in software like CORAL to correlate descriptors with endpoints, often improved by incorporating the Index of Ideality of Correlation (IIC) and Correlation Intensity Index (CII) [14].

- Machine Learning Algorithms: Modern pipelines utilize up to 20 different machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) to automatically generate robust models [16].

- Model Validation: This is a critical step to ensure model robustness and predictive power. It involves:

- Internal Validation: Using techniques like cross-validation.

- External Validation: Testing the model on a completely separate set of compounds not used in training. Standard statistical metrics are used, including the coefficient of determination (R²), mean squared error (MSE), and Fisher's criteria (F) [15]. A rigorous validation should always assess performance relative to the model's Applicability Domain (AD) [11] [13].

ADMET In Silico Screening: Promising compounds identified by the QSAR model are virtually screened for their ADMET properties. This involves using specialized QSAR models to predict key endpoints such as human intestinal absorption, plasma protein binding, CYP enzyme inhibition, and cardiac toxicity. This step filters out compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicological profiles early in the process [14]. For example, in a study on naphthoquinone derivatives, 67 compounds with high predicted pIC₅₀ were reduced to 16 promising candidates after ADMET filtering [14].

Advanced Validation: Molecular Docking and Dynamics

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Validation

| Reagent / Software Solution | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Gaussian 09W | Software for quantum chemical calculations to optimize molecular geometry and compute electronic descriptors [15]. |

| ChemOffice Software | Suite for calculating topological descriptors (e.g., LogP, LogS, PSA) from molecular structure [15]. |

| CORAL Software | Tool for developing QSAR models using Monte Carlo optimization and SMILES-based descriptors [14]. |

| AutoDock Vina / GOLD | Molecular docking software to predict the binding orientation and affinity of a ligand to a protein target [14]. |

| GROMACS / AMBER | Software for performing Molecular Dynamics simulations to study the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand complexes over time [14]. |

| PDB ID: 1ZXM | Protein Data Bank structure of Topoisomerase IIα, used as a target for docking naphthoquinone derivatives [14]. |

| Tubulin-Colchicine Site | A key binding site on the Tubulin protein, targeted by 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives in cancer therapy [15]. |

For compounds intended as therapeutic agents, computational validation often goes beyond QSAR. Molecular docking is used to predict the binding mode and affinity of a candidate compound to its biological target (e.g., Tubulin or Topoisomerase IIα). The candidate with the highest binding affinity is then subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., for 100-300 ns) to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex under physiological conditions. Key metrics include the root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) [14] [15]. For instance, a study on triazine derivatives identified Pred28, which showed a docking score of -9.6 kcal/mol and a stable RMSD of 0.29 nm over 100 ns, confirming its potential as a stable binder [15]. The relationship between these advanced techniques is shown below.

The field of QSAR modeling is continuously evolving. Future directions include the increased integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, the development of more sophisticated read-across platforms like OrbiTox that combine similarity searching, QSAR models, and metabolism prediction, and the creation of automated, standardized pipelines for generating regulatory-compliant models [16]. Collaborative projects like ONTOX aim to use AI to integrate PC, TK, and other data for a more holistic risk assessment [13].

In conclusion, QSAR models play a critical and expanding role in predicting the physicochemical and toxicokinetic properties of chemicals. They are central to the paradigm of open-access in silico tools for ADMET profiling, enabling the rapid, cost-effective, and ethical screening of chemical libraries. The reliability of these models is well-documented through rigorous benchmarking, and their power is maximized when integrated into a comprehensive workflow that includes robust validation, ADMET filtering, and advanced structural modeling techniques like docking and dynamics. As computational power and methodologies advance, QSAR will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of computational toxicology and drug discovery.

The adoption of open-access in silico tools has revolutionized disease management by enabling the early prediction of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles of next-generation drug candidates [4] [12]. In modern drug discovery, accurately predicting these properties is essential for selecting compounds with optimal pharmacokinetics and minimal toxicity, thereby reducing late-stage attrition rates [9] [17]. The field is transitioning from single-endpoint predictions to multi-endpoint joint modeling, incorporating multimodal features to improve predictive accuracy [17]. The choice of in silico tools is critically important, as the accuracy of ADMET prediction largely depends on the types of datasets, the algorithms used, the quality of the model, the available endpoints for prediction, and user requirements [4] [12]. A key best practice is to use multiple in silico tools for predictions and compare the results, followed by the identification of the most probable prediction [12]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of key platforms, focusing on their methodologies, applications, and experimental protocols.

PharmaBench: A Large-Scale Benchmark for ADMET Properties

PharmaBench represents a significant advancement in ADMET benchmarking, created to address the limitations of existing benchmark sets, which were often limited in utility due to their small dataset sizes and lack of representation of compounds used in actual drug discovery projects [9]. This comprehensive benchmark set for ADMET properties comprises eleven ADMET datasets and 52,482 entries, serving as an open-source dataset for developing AI models relevant to drug discovery projects [9].

Key Innovation and Methodology: A primary innovation behind PharmaBench is its use of a multi-agent data mining system based on Large Language Models (LLMs) that effectively identifies experimental conditions within 14,401 bioassays [9]. This system facilitates merging entries from different sources, overcoming a major challenge in data curation. The data processing workflow integrates data from various sources, starting with 156,618 raw entries, which are then standardized and filtered to construct the final benchmark [9]. The multi-agent LLM system consists of three specialized agents, as detailed in the experimental protocols section.

Table: Key Features of PharmaBench

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Total Raw Entries Processed | 156,618 [9] |

| Final Curated Entries | 52,482 [9] |

| Number of ADMET Datasets | 11 [9] |

| Number of Bioassays Analyzed | 14,401 [9] |

| Core Innovation | Multi-agent LLM system for experimental condition extraction [9] |

| Primary Data Source | ChEMBL database, augmented with other public datasets [9] |

Other Notable Platforms and Community Efforts

Beyond dedicated benchmarking platforms like PharmaBench, the field is supported by various open-science initiatives and models.

- OpenADMET Initiative: This is an open-science initiative that aims to tackle ADMET prediction challenges by integrating structural biology, high-throughput experimentation, and computational modeling [18]. A key part of its efforts is organizing blind challenges to benchmark the current state of predictive modeling on real, high-quality datasets. A recent collaboration with ExpansionRx has made over 7,000 small molecules measured across multiple ADMET assays available as a public benchmark [18] [19].

- MSformer-ADMET: This is a novel molecular representation architecture specifically optimized for ADMET property prediction [20]. Unlike traditional language models, it adopts interpretable fragments as its fundamental modeling units, introducing chemically meaningful structural representations. The model is fine-tuned on 22 tasks from the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) and has demonstrated superior performance across a wide range of ADMET endpoints compared to conventional SMILES-based and graph-based models [20].

- Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC): While not a prediction platform itself, TDC is a crucial community resource that includes 28 ADMET-related datasets with over 100,000 entries by integrating multiple curated datasets from previous work [9]. It provides a standardized framework for accessing and benchmarking models on ADMET-related tasks.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Multi-Agent LLM Workflow in PharmaBench

The construction of PharmaBench involves a sophisticated data processing workflow designed to merge entries from different sources and standardize experimental data. The protocol can be divided into several key stages, with the multi-agent LLM system at its core [9].

1. Data Collection: The primary data originates from the ChEMBL database, a manually curated collection of SAR and physicochemical property data from peer-reviewed articles. Initially, 97,609 raw entries from 14,401 bioassays in ChEMBL were analyzed. This was augmented with 59,009 entries from other public datasets, resulting in over 150,000 entries used for construction [9].

2. Multi-Agent LLM Data Mining: This stage addresses the challenge of unstructured experimental conditions (e.g., buffer type, pH) within assay descriptions. A system with three specialized agents is employed, with GPT-4 as the core LLM [9].

- Keyword Extraction Agent (KEA): Summarizes key experimental conditions from various ADMET experiments. It processes assay descriptions to identify and rank the most frequent and critical conditions [9].

- Example Forming Agent (EFA): Generates few-shot learning examples based on the experimental conditions summarized by the KEA. These examples are manually validated to ensure quality [9].

- Data Mining Agent (DMA): Uses the prompts created by the KEA and EFA to mine through all assay descriptions and identify all relevant experimental conditions [9].

3. Data Standardization and Filtering: After identifying experimental conditions, results from various sources are merged. The data is then standardized and filtered based on drug-likeness, experimental values, and conditions to ensure consistency [9].

4. Post-Processing: The final stage involves removing duplicate test results and dividing the dataset using Random and Scaffold splitting methods for AI modeling. This results in a final benchmark set with experimental results in consistent units under standardized conditions [9].

Model Training and Validation with MSformer-ADMET

The MSformer-ADMET pipeline provides a state-of-the-art protocol for molecular representation and property prediction, emphasizing fragment-based interpretability [20].

1. Meta-Structure Fragmentation: The query molecule is first converted into a set of meta-structures. These fragments are treated as representatives of local structural motifs, and their combinations capture the global conformational characteristics of the molecule [20].

2. Molecular Encoding: The fragments are encoded into fixed-length embeddings using a pretrained encoder. This enables molecular-level structural alignment, allowing the model to represent diverse molecules in a shared vector space [20].

3. Feature Extraction and Multi-Task Prediction: The structural embeddings are passed into a feature extraction module, which refines task-specific semantic information. Global Average Pooling (GAP) is applied to aggregate fragment-level features into molecule-level representations. Finally, a multi-head parallel MLP structure supports simultaneous modeling of multiple ADMET endpoints [20].

4. Pretraining and Fine-Tuning: MSformer-ADMET leverages a pretraining-finetuning strategy. The model is first pretrained on a large corpus of 234 million representative original structure data. For ADMET prediction, it is then fine-tuned on 22 specific datasets from the TDC, with shared encoder weights supporting efficient cross-task transfer learning [20].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational ADMET Profiling

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Source/Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Data Resource | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties used for model training and validation. | [9] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Resource | A collection of 28 ADMET-related datasets providing standardized benchmarks for model development and evaluation. | [9] [20] |

| RDKit | Software Library | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating fundamental physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, log P). | [17] |

| GPT-4 / LLMs | Computational Tool | Large Language Models used as core engines for extracting unstructured experimental conditions from biomedical literature and assay descriptions. | [9] |

| ExpansionRx Dataset | Experimental Data | A high-quality, open-sourced dataset of over 7,000 small molecules with measured ADMET endpoints, used for blind challenge benchmarking. | [18] |

Open-access platforms like PharmaBench, MSformer-ADMET, and community-driven initiatives like the OpenADMET challenges are fundamentally advancing the field of in silico ADMET profiling [9] [18] [20]. By providing large-scale, high-quality, and standardized datasets, these resources address critical limitations of earlier benchmarks and enable the development of more robust and generalizable AI models. The integration of advanced techniques, such as multi-agent LLM systems for data curation and fragment-based Transformer architectures for model interpretability, is setting new standards for accuracy and transparency in predictive toxicology and pharmacokinetics. As these tools continue to evolve, their deep integration into drug discovery workflows promises to significantly reduce development costs and timelines by enabling earlier and more reliable identification of compounds with optimal ADMET properties.

The failure of drug candidates due to unfavorable pharmacokinetics and toxicity remains a primary cause of attrition in drug development, accounting for approximately 50% of failures [21]. Early evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has become crucial for identifying viable candidates before substantial resources are invested [21]. Open access in silico tools have emerged as powerful resources for predicting these properties, providing researchers with cost-effective, rapid methods for initial ADMET profiling [22]. These computational approaches are particularly valuable for evaluating natural compounds, which often present unique challenges including structural complexity, limited availability, and instability [22]. This guide focuses on four critical ADMET endpoints—LogP, solubility, permeability, and toxicity—that are essential for early-stage drug candidate evaluation.

Core ADMET Endpoints: Definition and Significance

Lipophilicity (LogP)

LogP, defined as the logarithm of the n-octanol/water partition coefficient, represents a compound's lipophilicity and significantly influences both membrane permeability and hydrophobic binding to macromolecules, including target receptors, plasma proteins, transporters, and metabolizing enzymes [23]. This endpoint possesses a leading position in ADMET evaluation due to its considerable impact on drug behavior in vivo. The optimal range for LogP in drug candidates is typically between 0 and 3 log mol/L [23]. Related to LogP is LogD7.4, which represents the n-octanol/water distribution coefficient at physiological pH (7.4) and provides a more relevant measure under biological conditions. A suitable LogD7.4 value generally falls between 1 and 3 log mol/L, helping maintain the crucial balance between lipophilicity and hydrophilicity necessary for dissolving in body fluids while effectively penetrating biomembranes [23].

Aqueous Solubility (LogS)

Aqueous solubility, expressed as LogS (the logarithm of molar solubility in mol/L), critically determines the initial absorption phase after administration [23]. The dissolution process is the first step in drug absorption, following tablet disintegration or capsule dissolution. Poor solubility often detrimentally impacts oral absorption completeness and efficiency, making early measurement vital in drug discovery pipelines [23]. Compounds demonstrating LogS values between -4 and 0.5 log mol/L are generally considered to possess adequate solubility properties for further development [23].

Permeability

Permeability refers to a compound's ability to cross biological membranes, a fundamental requirement for reaching systemic circulation and ultimately its site of action. In silico models frequently predict permeability using cell-based models like Caco-2 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells), which serve as indicators of intestinal absorption [21]. Additionally, P-glycoprotein (Pgp) interactions are often evaluated, as this transporter protein can actively efflux compounds back into the intestinal lumen, significantly reducing their bioavailability [21]. Permeability predictions help researchers identify compounds with favorable absorption characteristics while flagging those likely to suffer from poor bioavailability.

Toxicity Endpoints

Toxicity profiling encompasses multiple endpoints that identify potentially harmful off-target effects. Common toxicity predictions include:

- hERG inhibition: Assessing blockage of the human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene potassium channel, associated with lethal cardiac arrhythmias [21]

- Hepatotoxicity: Predicting drug-induced liver injury [21]

- Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS): Identifying substructures that cause false positives in high-throughput screening assays [23]

- AMES mutagenicity: Detecting potential genotoxicants [21]

- Structural alerts: Recognizing undesirable, reactive substructures like BMS alerts, ALARM NMR, and chelators [23]

Table 1: Optimal Range for Key Physicochemical and ADMET Properties

| Property | Description | Optimal Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogP | n-octanol/water partition coefficient | 0 - 3 | Balanced lipophilicity |

| LogD7.4 | Distribution coefficient at pH 7.4 | 1 - 3 | Relevant to physiological conditions |

| LogS | Aqueous solubility | -4 - 0.5 log mol/L | Proper dissolution |

| Molecular Weight | Molecular mass | 100 - 600 | Based on Drug-Like Soft rule |

| nHA | Hydrogen bond acceptors | 0 - 12 | Based on Drug-Like Soft rule |

| nHD | Hydrogen bond donors | 0 - 7 | Based on Drug-Like Soft rule |

| nRot | Rotatable bonds | 0 - 11 | Based on Drug-Like Soft rule |

| TPSA | Topological polar surface area | 0 - 140 Ų | Based on Veber rule |

In Silico Methodologies for ADMET Prediction

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Modeling

QSPR models correlate molecular descriptors or structural features with biological properties or activities, forming the foundation of many ADMET prediction tools [21]. These models utilize computed molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, polar surface area, charge distribution) or structural fingerprints to establish mathematical relationships that predict endpoint values [21]. The robustness of QSPR models depends heavily on the quality and diversity of the training data, with more diverse datasets generally yielding better predictive coverage across chemical space [21].

Graph Neural Networks and Multi-Task Learning

Advanced machine learning approaches, particularly multi-task graph learning frameworks, have recently demonstrated superior performance in ADMET prediction [24]. These methods represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, applying graph attention networks to capture complex structural relationships [21]. The "one primary, multiple auxiliaries" paradigm in multi-task learning enables models to leverage information across related endpoints, improving prediction accuracy, especially for endpoints with limited training data [24]. These approaches also provide interpretability by identifying key molecular substructures relevant to specific ADMET tasks [24].

Molecular Dynamics and Quantum Mechanics

For specific applications, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and quantum mechanics (QM) calculations provide detailed insights into molecular interactions affecting ADMET properties [10]. MD simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, revealing conformational changes and binding stability in physiological conditions [10]. QM methods, particularly when combined with molecular mechanics in QM/MM approaches, help understand metabolic reactions and regioselectivity in cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism [22]. These computationally intensive methods offer atomic-level insights but require significant resources, making them more suitable for focused investigations rather than high-throughput screening.

Experimental Protocols for In Silico ADMET Profiling

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Single-Compound Evaluation Using ADMETlab 2.0

Objective: To obtain a complete ADMET profile for a single chemical compound using the open-access ADMETlab 2.0 platform.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Compound Input: Navigate to the ADMETlab 2.0 Evaluation module. Input the compound structure by either:

- Pasting the canonical SMILES string into the input field, or

- Drawing the chemical structure directly using the integrated JMSE molecule editor [21]

Structure Standardization: The webserver automatically standardizes input SMILES strings to ensure consistent representation before computation [21]

Endpoint Calculation: The system computes all 88 supported ADMET-related endpoints, including:

- 17 physicochemical properties

- 13 medicinal chemistry properties

- 23 ADME properties

- 27 toxicity endpoints

- 8 toxicophore rules (covering 751 substructures) [21]

Results Interpretation:

- For regression model endpoints (e.g., Caco-2 permeability, plasma protein binding), examine the concrete predicted numerical values [21]

- For classification model endpoints (e.g., Pgp-inhibitor, hERG Blocker), interpret the transformed probability values using the six symbolic categories:

- 0-0.1: (−−−) - Nontoxic or appropriate

- 0.1-0.3: (−−) - Nontoxic or appropriate

- 0.3-0.5: (−) - Requires further assessment

- 0.5-0.7: (+) - Requires further assessment

- 0.7-0.9: (++) - More likely toxic or defective

- 0.9-1.0: (+++) - More likely toxic or defective [21]

- For substructural alerts (e.g., PAINS, SureChEMBL), click the DETAIL button to identify undesirable substructures if the number of alerts is not zero [21]

Result Export: Download the complete result file in either CSV or PDF format for documentation and further analysis [21]

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Compound Screening Using ADMETlab 2.0

Objective: To efficiently screen compound libraries for ADMET properties to prioritize candidates for further development.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation: Prepare a compound list in one of these formats:

- A list of SMILES strings without column headers or molecular indexes

- An uploaded SDF file

- An uploaded TXT file [21]

Batch Submission: Access the Screening pattern in ADMETlab 2.0 and submit the compound file. The system processes multiple compounds sequentially without requiring user intervention [21]

Results Collection: After job completion (approximately 84 seconds for 1000 molecules, depending on molecular complexity):

Data Analysis:

- Download the complete CSV-formatted result file containing probability values for all classification endpoints

- Apply custom thresholds to filter out deficient compounds according to project-specific reliability requirements [21]

- Cross-reference results with applicability domain assessments to identify predictions outside the model's reliable coverage [25]

Hit Prioritization: Rank compounds based on favorable ADMET profiles, considering both individual endpoint scores and overall patterns across multiple properties.

Table 2: Key Open Access Tools for ADMET Prediction

| Tool Name | Key Features | Endpoints Covered | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMETlab 2.0 | Multi-task graph attention framework; batch computation; 88 endpoints | Physicochemical, medicinal chemistry, ADME, toxicity, toxicophore rules | https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/ [21] |

| admetSAR 3.0 | Applicability domain assessment; large database | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity | http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar3/ [25] |

| ProTox | Toxicity prediction | Acute toxicity, hepatotoxicity, cytotoxicity, mutagenicity | https://tox.charite.de/protox3/ [10] |

| vNN-ADMET | Neural network-based predictions | Various ADMET endpoints | https://vnnadmet.bhsai.org/vnnadmet/home.xhtml [10] |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for ADMET Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Access/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Access Prediction Platforms | ADMETlab 2.0 | Comprehensive ADMET profiling for single compounds and libraries | Web server (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) [21] |

| admetSAR 3.0 | ADMET prediction with applicability domain assessment | Web server (http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar3/) [25] | |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem | Canonical SMILES retrieval and compound information | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [10] |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit | Molecular standardization, descriptor calculation, SMARTS pattern recognition | Python library [21] |

| Structural Visualization | PyMOL | Analysis of molecular docking poses and interactions | https://pymol.org/ [10] |

| Molecular Dynamics | AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking and binding affinity estimation | Standalone software [10] |

| Applicability Domain Assessment | Physicochemical Range Analysis | Determines prediction reliability based on training data boundaries | Implementation in admetSAR 3.0 [25] |

Workflow Visualization: Integrated ADMET Profiling Pipeline

ADMET Profiling Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated computational pipeline for ADMET evaluation, from compound input through result interpretation, highlighting the key properties assessed and open-access tools available.

Case Study: ADMET Profiling of Karanjin for Anti-Obesity Potential

A recent investigation into the natural compound Karanjin (a furanoflavonoid from Pongamia pinnata) demonstrates the practical application of in silico ADMET profiling in drug discovery [10]. Researchers employed a multi-platform approach to evaluate Karanjin's potential as an anti-obesity agent, utilizing admetSAR, vNN-ADMET, and ProTox for comprehensive pharmacokinetic and toxicity assessment [10]. The study revealed favorable absorption and distribution properties, with no significant toxicity alerts, supporting its potential as a therapeutic candidate [10].

Network pharmacology analysis identified 145 overlapping targets between Karanjin and obesity-related genes, with enriched pathways including AGE-RAGE signaling in diabetic complications—a pathway implicated in oxidative stress and metabolic dysregulation [10]. Molecular docking against eight hub proteins demonstrated strong binding affinities, with Karanjin exhibiting superior binding energies compared to reference anti-obesity drugs, particularly with the PIK3CA-Karanjin complex showing the most favorable interaction profile [10].

This case study exemplifies how integrated in silico methodologies can provide comprehensive ADMET characterization early in the drug discovery process, enabling researchers to prioritize natural compounds with promising therapeutic potential and favorable safety profiles before committing to costly experimental validation.

The strategic implementation of open access in silico tools for evaluating key ADMET endpoints—LogP, solubility, permeability, and toxicity—represents a paradigm shift in early drug discovery. These computational approaches enable researchers to identify potential pharmacokinetic and safety issues before investing in synthetic chemistry and biological testing, significantly reducing development costs and timelines [21] [22]. The continuous advancement of prediction algorithms, particularly through multi-task graph learning and robust applicability domain assessment, continues to enhance the reliability and scope of these tools [24] [25]. As these resources become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they empower the research community to make more informed decisions in compound selection and optimization, ultimately contributing to more efficient and successful drug development pipelines.

A Practical Workflow for Using Open Access ADMET Tools

Step-by-Step Guide to Molecular Encoding with SMILES and Beyond

In the realm of modern drug discovery, the ability to accurately represent molecular structures in a digital format is foundational for computational analysis. Molecular encoding serves as the critical bridge between a chemical structure and the in silico models that predict its behavior, most notably its Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) is a simplified chemical nomenclature that provides a robust, string-based representation of a molecule's structure and stereochemistry [26] [27]. This encoding is the primary input for a generation of open-access, predictive ADMET tools that have revolutionized the early stages of drug development, allowing researchers to triage compounds with unfavorable properties before committing to costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments [12] [28].

This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of molecular encoding using SMILES, detailing its syntax, advanced canonicalization algorithms, and its integral role within contemporary ADMET profiling workflows. By framing this within the context of open-access research, we emphasize the democratization of tools that are essential for efficient and effective drug discovery.

Fundamentals of the SMILES Language

SMILES is more than a simple file format; it is a precise language that describes a molecular graph based on established principles of valence chemistry [26]. It represents a valence model of a molecule, making it intuitive for chemists to understand and validate.

Core Grammar and Syntax

The grammar of SMILES is built upon a small set of rules for representing atoms, bonds, branches, and cycles.

- Atoms: Atoms are represented by their atomic symbols. Elements in the "organic subset" (B, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, and I) can be written without brackets. All other elements, such as metals or atoms with specified properties, must be enclosed in square brackets (e.g.,

[Na+],[Fe+2]) [26] [27]. - Hydrogens: Hydrogen atoms attached to atoms in the organic subset are typically implied to satisfy the atom's standard valence. For example, "C" represents a carbon atom with four implicit hydrogens (methane, CH₄). Hydrogens are explicitly stated when they are attached to atoms outside the organic subset or in specific cases like molecular hydrogen (

[H][H]) or hydronium ([OH3+]) [26]. - Bonds: Single and aromatic bonds are default and are not represented with a symbol. Double bonds are denoted by

=, and triple bonds by#[26]. For example, ethene isC=C, and ethyne isC#C. - Branches: Branches in the molecular structure are represented using parentheses. For instance, isobutane can be written as

CC(C)C, where the(C)represents a methyl group branching off from the central carbon [26]. - Cycles: Cyclic structures are represented by breaking one single or aromatic bond in the ring and labeling the two atoms involved with the same number after their atomic symbol. For example, cyclohexane is

C1CCCCC1, where the "1" indicates the connection between the first and last carbon atoms [26]. Structures with more than ten rings use a two-digit number preceded by a percent sign (e.g.,%99) [27]. - Aromaticity: Aromatic rings are denoted by using lowercase letters for the aromatic atoms (e.g.,

c,n,o). Aromaticity is determined by applying an extended version of Hückel's rule [26]. Benzene, for example, isc1ccccc1.

Table 1: Summary of Fundamental SMILES Notation Rules

| Structural Feature | SMILES Symbol | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic Atom | Uppercase Letter | C, N, O |

Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen (with implicit H) |

| Aromatic Atom | Lowercase Letter | c, n |

Aromatic carbon, nitrogen |

| Explicit Atom | Square Brackets | [Na+], [nH] |

Specifies element, charge, or H-count |

| Double Bond | = |

O=C=O |

Carbon dioxide |

| Triple Bond | # |

C#N |

Hydrogen cyanide |

| Branch | Parentheses () |

CC(=O)O |

Acetic acid (branch for =O) |

| Ring Closure | Numbers | C1CCCCC1 |

Cyclohexane |

Representing Stereochemistry and Isotopes

SMILES provides mechanisms for conveying the three-dimensional configuration of molecules, which is critical for accurately modeling biological interactions.

- Tetrahedral Chirality: Tetrahedral chiral centers are specified with

@or@@symbols placed after the atom in brackets.@indicates an anticlockwise order of the subsequent ligands when viewed from the chiral center towards the first-connected atom, while@@indicates a clockwise order [27]. For example, L-alanine isN[C@@H](C)C(=O)O[26]. - Double Bond Stereochemistry: The configuration around a double bond (E/Z) is indicated using the forward slash (

/) and backslash (\) directional bonds to show the relative positions of substituents. For example, trans-2-butene is represented asC/C=C/C[26]. - Isotopes: Isotopes are represented by placing the mass number immediately before the atomic symbol within the brackets. Deuterium oxide (heavy water) is written as

[2H]O[2H][26].

The CANGEN Algorithm: From SMILES to Canonical SMILES

A significant limitation of generic SMILES is that a single molecule can have multiple valid string representations depending on the atom traversal order. For instance, ethanol can be written as CCO, OCC, or C(O)C. This non-uniqueness is problematic for database indexing and cheminformatics algorithms. The solution is canonical SMILES, a unique, standardized representation for any given molecular structure, generated using the CANGEN algorithm [27].

The CANGEN algorithm consists of two main phases: CANON (canonical labeling) and GENES (SMILES generation) [27].

The CANON Phase: Canonical Labeling of Atoms

The CANON phase is an iterative process that assigns a unique rank to every atom in the molecule based on its topological features. The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow.

CANON Algorithm Flow

The process relies on five atomic invariants, which are intrinsic properties of each atom that do not depend on the molecular representation [27]:

- Number of non-hydrogen connections

- Number of non-hydrogen bonds (single, double, triple)

- Atomic number

- Sign of the charge

- Number of attached hydrogen atoms

The step-by-step methodology is as follows:

- Step Zero: Calculate Individual Invariants. Each heavy atom is assigned a tuple of the five atomic invariants. For example, a methyl carbon (-CH₃) might have the invariant

(1, 1, 6, 0, 3), indicating 1 connection, 1 non-hydrogen bond, atomic number 6 (carbon), 0 charge, and 3 attached hydrogens [27]. - Step One: Assign Initial Ranks. All atoms are ranked based on their individual invariant tuples, and each rank is assigned a corresponding prime number (e.g., rank 1 -> 2, rank 2 -> 3, rank 3 -> 5, etc.) [27].

- Step Two: Calculate New Invariants. For each atom, a new invariant is calculated by multiplying the prime numbers corresponding to the ranks of all its neighboring atoms. This incorporates information about the atom's topological environment [27].

- Step Three: Re-rank Atoms. Atoms are re-ranked based first on their previous rank and then on their new invariant to break ties. This creates a more refined ordering [27].

- Step Four: Iterate to Convergence. Steps Two and Three are repeated, using the new ranks to calculate new primes and new invariants. The process continues until the atomic ranks stabilize and no longer change between iterations [27].

The GENES Phase: Generating the Canonical String

Once every atom has a unique canonical rank, the GENES phase begins. This involves generating a SMILES string by performing a depth-first traversal of the molecular graph, starting from the highest-ranked atom and proceeding to its lowest-ranked neighbor at each branch. The traversal follows a strict order based on the canonical ranks, ensuring the same molecular graph always produces the same unique SMILES string [27].

SMILES in Practice: Integration with ADMET Profiling

The primary application of SMILES encoding within drug discovery is as the input for predictive ADMET models. Open-access platforms leverage these encodings to provide rapid, cost-effective property assessments.

Open-Access ADMET Prediction Platforms

Several key platforms have become staples in computational drug discovery:

- admetSAR3.0: This is a comprehensive platform for chemical ADMET assessment. Its core database contains over 370,000 high-quality experimental ADMET data points for more than 100,000 unique compounds, all searchable and accessible via SMILES strings. The prediction module uses a multi-task graph neural network framework to evaluate compounds across 119 different ADMET endpoints, more than double its previous version. It supports user-friendly input via SMILES string, chemical structure drawing, or batch file upload [28].

- PharmaBench: This is a recently developed, large-scale benchmark dataset designed to overcome the limitations of earlier, smaller datasets. It was constructed using a multi-agent LLM (Large Language Model) system to mine and standardize experimental data from sources like ChEMBL. PharmaBench contains over 52,000 entries for eleven key ADMET properties, providing a robust dataset for training and evaluating predictive AI models [9].

- SwissADME and ProTox-II: These are other widely cited, open-access web servers that provide ADMET predictions using SMILES as the primary input format [28].

Table 2: Key Open-Access ADMET Tools and Databases

| Tool / Database | Key Features | Number of Endpoints / Compounds | Primary Input |

|---|---|---|---|

| admetSAR3.0 [28] | Search, Prediction, & Optimization modules | 119 endpoints; 370,000+ data points | SMILES, Structure Draw, File |

| PharmaBench [9] | Curated benchmark for AI model training | 11 ADMET properties; 52,000+ entries | SMILES |

| MoleculeNet [9] | Broad benchmark for molecular machine learning | 17+ datasets; 700,000+ compounds | SMILES |

| Therapeutics Data Commons [9] | Integration of multiple curated datasets | 28 ADMET datasets; 100,000+ entries | SMILES |

Experimental Protocol for In Silico ADMET Screening

The following workflow details a standard methodology for using SMILES with open-access tools to screen a compound library for ADMET properties.

- Compound Library Preparation. A virtual library of compounds is assembled, and a canonical SMILES string is generated for each unique structure using a tool like RDKit or Open Babel. This ensures consistency and uniqueness.

- Data Input. The list of canonical SMILES strings is prepared as a plain text file, with one SMILES per line.

- Batch Processing. The file is uploaded to the batch screening function of an ADMET platform, such as admetSAR3.0, which allows the evaluation of up to 1000 compounds per job [28].

- Result Analysis. The platform returns a table of results, typically with both categorical (e.g., "Yes"/"No" for Ames toxicity) and continuous (e.g., predicted logS for solubility) values. These results are analyzed against project-specific success criteria (e.g., "High intestinal absorption," "No predicted hERG inhibition").

- Decision Guidance. Based on the predictions, compounds are prioritized. Some platforms, like admetSAR3.0, offer an "ADMETopt" module that suggests structural modifications to improve problematic properties through scaffold hopping or transformation rules [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Computational ADMET

Table 3: Key Research "Reagents" for SMILES-Based ADMET Workflows

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular properties, generates canonical SMILES, handles file format conversion. |

| Open Babel | Chemical Toolbox | Converts between chemical file formats and generates SMILES strings. |

| admetSAR3.0 | Web Platform | Provides experimental data lookup and multi-endpoint ADMET prediction. |

| PharmaBench | Benchmark Dataset | Serves as a gold-standard dataset for training and validating new predictive models. |

| JSME Molecular Editor | Web Component | Allows for interactive drawing of chemical structures and outputs corresponding SMILES. |

| ChEMBL Database | Public Repository | Source of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for data mining. |

Advanced Topics: Beyond Basic SMILES Encoding

The field of molecular representation continues to evolve beyond the string-based paradigm of SMILES.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Modern ADMET prediction models, like the one in admetSAR3.0, increasingly use GNNs. These models operate directly on the molecular graph, using atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, thereby bypassing the SMILES string entirely and potentially capturing richer structural information [28].

- Large Language Models (LLMs) for Data Curation: The construction of large benchmarks like PharmaBench is now assisted by multi-agent LLM systems. These systems automatically mine and extract complex experimental conditions from unstructured text in scientific literature, enabling the creation of larger, more consistent, and more reliable datasets for model training [9].

- Integration with Optimization Tools: The next step beyond profiling is active optimization. Tools like ADMETopt use SMILES representations to suggest structural analogs with improved predicted ADMET profiles, closing the loop between prediction and design [28].

SMILES encoding remains a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery, providing a compact, human-readable, and machine-interpretable language for representing molecules. Its direct integration into powerful, open-access ADMET platforms like admetSAR3.0 and large-scale benchmarks like PharmaBench has democratized access to critical pharmacokinetic and toxicity data. As the field advances with Graph Neural Networks and AI-driven data curation, the principles of unambiguous molecular representation—exemplified by the canonical SMILES algorithm—will continue to underpin the development of more reliable and effective in silico tools for guiding drug candidates to clinical success.

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for High-Throughput ADMET Screening

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) into Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) screening represents a paradigm shift in modern drug discovery. Traditional experimental methods for assessing these critical properties, while reliable, are notoriously resource-intensive and time-consuming, often creating bottlenecks in the development pipeline [2]. Conversely, conventional computational models have historically lacked the robustness and generalizability required for accurate prediction of complex in vivo outcomes [2]. The emergence of AI and ML technologies has successfully addressed this gap, providing scalable, efficient, and powerful alternatives that are rapidly becoming indispensable tools for early-stage drug discovery [2] [29].

This transformation is particularly crucial given the high attrition rates in clinical drug development, where approximately 40–45% of clinical failures are attributed to inadequate ADMET profiles [5]. By leveraging large-scale compound databases and sophisticated algorithms, ML-driven approaches enable the high-throughput prediction of ADMET properties with significantly improved efficiency, allowing researchers to filter out problematic compounds long before they reach costly clinical trials [2]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how AI and ML are being leveraged for high-throughput ADMET screening, with a specific focus on the pivotal role of open-access in silico tools and datasets in advancing this field.

Core Machine Learning Methodologies in ADMET Prediction

The application of ML in ADMET prediction encompasses a diverse array of algorithmic strategies, each with distinct strengths for deciphering the complex relationships between chemical structure and biological activity.

Key Algorithmic Approaches

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs have emerged as a particularly powerful architecture for ADMET prediction because they operate directly on the molecular graph structure, naturally representing atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. This approach allows the model to capture intricate topological features and functional group relationships that are fundamental to understanding pharmacokinetic behavior [2]. GNNs can learn hierarchical representations of molecules, from atomic environments to larger substructures, enabling them to make predictions based on chemically meaningful patterns.

Ensemble Learning: This methodology combines predictions from multiple base ML models to produce a single, consensus prediction that is generally more accurate and robust than any individual model. Ensemble techniques are especially valuable in ADMET prediction due to the noisy and heterogeneous nature of biological screening data [2]. By reducing variance and mitigating model-specific biases, ensemble methods enhance prediction reliability across diverse chemical spaces, a critical requirement for effective virtual screening.

Multitask Learning (MTL): MTL frameworks simultaneously train models on multiple related ADMET endpoints, allowing the algorithm to leverage shared information and latent representations across different prediction tasks [2] [29]. This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in predictive accuracy, particularly for endpoints with limited training data, by effectively regularizing the model and preventing overfitting. The MTL paradigm mirrors the interconnected nature of ADMET processes themselves, where properties like metabolic stability and permeability often share underlying physicochemical determinants.

Transfer Learning: This approach involves pre-training models on large, general chemical databases followed by fine-tuning on specific ADMET endpoints. Transfer learning is particularly beneficial when experimental ADMET data is scarce, as it allows the model to incorporate fundamental chemical knowledge before specializing [29].

Enhanced Predictive Capabilities through Multimodal Data Integration

A cutting-edge advancement in ML-driven ADMET prediction involves the integration of multimodal data sources to enhance model robustness and clinical relevance. Beyond molecular structures alone, state-of-the-art models now incorporate diverse data types including pharmacological profiles, gene expression datasets, and protein structural information [2]. This multimodal approach enables the development of more physiologically realistic models that can better account for the complex biological interactions governing drug disposition and safety.

For example, models that combine compound structural data with information about relevant biological targets or expression patterns of metabolizing enzymes can provide more accurate predictions of interspecies differences and potential drug-drug interactions [2]. The integration of such diverse data modalities represents a significant step toward bridging the gap between in silico predictions and clinical outcomes, addressing a long-standing challenge in computational ADMET modeling.

Table 1: Core Machine Learning Approaches in ADMET Prediction

| Methodology | Key Mechanism | Primary Advantage | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Direct learning from molecular graph structure | Captures complex topological features and functional group relationships | Molecular property prediction from structural data [2] |

| Ensemble Learning | Combination of multiple base models | Reduces variance and increases prediction robustness | Consensus models for toxicity endpoints [2] |

| Multitask Learning (MTL) | Simultaneous training on related endpoints | Leverages shared information across tasks; improves data efficiency | Concurrent prediction of solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability [2] [29] |

| Transfer Learning | Pre-training on large datasets before fine-tuning | Effective for endpoints with limited training data | Using general chemical knowledge to enhance specific ADMET predictions [29] |

Open-Access Tools and Benchmarks for ADMET Profiling

The development of robust, accessible in silico tools is fundamental to the advancement of AI-driven ADMET screening. A growing ecosystem of open-access platforms provides researchers with powerful capabilities for predicting ADMET properties without prohibitive costs or computational barriers.

Leading Open-Access Platforms

ADMET-AI: This web-based platform employs a graph neural network architecture known as Chemprop-RDKit, trained on 41 ADMET datasets from the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [30]. ADMET-AI provides predictions for a comprehensive range of properties and offers the distinct advantage of contextualizing results by comparing them against a reference set of approximately 2,579 approved drugs from DrugBank [30]. This benchmarking capability allows researchers to quickly assess how their compounds of interest compare to known drug molecules across multiple ADMET parameters simultaneously.

ADMETlab 2.0: This extensively updated platform enables the calculation and prediction of 80 different ADMET-related properties, spanning 17 physicochemical properties, 13 medicinal chemistry measures, 23 ADME endpoints, and 27 toxicity endpoints [31]. The system is built on a multi-task graph attention (MGA) framework that significantly enhances prediction accuracy for many endpoints. A particularly valuable feature is its user-friendly visualization system, which employs color-coded dots (green, yellow, red) to immediately indicate whether a compound falls within the desirable range for each property [31].

PharmaBench: Addressing a critical need in the field, PharmaBench is a comprehensive benchmark set for ADMET properties, comprising eleven curated datasets and over 52,000 entries [9]. This resource was developed specifically to overcome the limitations of previous benchmarks, which often contained compounds that were not representative of those used in actual drug discovery projects. The creation of PharmaBench utilized an innovative multi-agent data mining system based on Large Language Models (LLMs) to effectively identify and standardize experimental conditions from 14,401 bioassays [9].

The Critical Role of Standardized Benchmarking

The development and widespread adoption of standardized benchmarks like PharmaBench and the Therapeutics Data Commons represent a pivotal advancement for the field [9]. These resources address two significant challenges that have historically hampered progress in AI-driven ADMET prediction: data scarcity and lack of standardized evaluation protocols.