Navigating Drug-Like Space: The Central Role of Physicochemical Properties in Modern Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role physicochemical properties play in the entire drug discovery and development pipeline.

Navigating Drug-Like Space: The Central Role of Physicochemical Properties in Modern Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role physicochemical properties play in the entire drug discovery and development pipeline. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that define 'drug-likeness,' examines cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for property optimization, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios in lead optimization and formulation, and validates strategies through comparative analysis of successful drug candidates. By synthesizing traditional rules with modern AI-driven approaches, this review serves as a strategic guide for designing effective, safe, and developable drug candidates, ultimately aiming to reduce late-stage attrition and accelerate the delivery of new medicines.

The Bedrock of Drug Design: Core Physicochemical Properties and 'Drug-Likeness'

In modern drug discovery, the optimization of a molecule's biological activity must be balanced with the engineering of its physicochemical properties to ensure adequate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of four cornerstone physicochemical properties—lipophilicity (LogP), aqueous solubility (LogS), acid dissociation constant (pKa), and molecular weight (MW). We define their fundamental principles, detail standardized experimental and computational protocols for their determination, and contextualize their critical influence on drug permeability and bioavailability. Framed within the context of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) and informed by contemporary artificial intelligence (AI) approaches, this guide serves as a resource for researchers and scientists in rational drug design.

Drug discovery is a lengthy, costly, and high-risk process, where a significant reason for clinical failure is inadequate drug-like properties, accounting for 10–15% of attritions [1]. The transition from a pharmacologically active hit compound to a viable drug candidate requires meticulous optimization of its physicochemical parameters to achieve a favorable equilibrium between solubility and permeability, which are critical for optimal drug uptake [1]. These properties are not isolated; they are interconnected determinants of a molecule's behavior in biological systems. Lipophilicity, solubility, ionization (pKa), and molecular size collectively influence a compound's ability to dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids, cross biological membranes, and reach its therapeutic target at an effective concentration. This guide delves into these four key properties, providing a technical foundation for their application in accelerating drug development.

Property Fundamentals and Measurement Methodologies

Lipophilicity (LogP and LogD)

Fundamental Principles: Lipophilicity quantifies a compound's affinity for a lipophilic phase over an aqueous phase. The partition coefficient (LogP) is the gold-standard measure, defined as the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of a compound's concentration in the immiscible solvents n-octanol and water at equilibrium, for the unionized form of the compound [2] [3].

For ionizable compounds, the distribution coefficient (LogD) is a more physiologically relevant metric, as it accounts for the distribution of all species (ionized, unionized, and partially ionized) at a specified pH. LogD is therefore pH-dependent, typically reported at pH 7.4 (blood) or 6.5 (intestinal) [2] [3]. A compound's LogD profile directly impacts its passive membrane permeability and aqueous solubility.

Experimental Protocols:

- Shake-Flask Method (Gold Standard): This method involves pre-saturating n-octanol and water buffers with each other. The compound of interest is dissolved in one phase, and the two phases are vigorously mixed to reach partitioning equilibrium. After phase separation via centrifugation, the compound concentration in each phase is quantified using techniques like UV spectroscopy or HPLC. LogP is calculated from the concentration ratio in the unionized state, while LogD is determined at the relevant pH [2].

- Reversed-Phase HPLC: This high-throughput alternative estimates lipophilicity by measuring the retention time of a compound on a reversed-phase column. The retention times are compared to those of a calibration set of standards with known LogP/LogD values. This method is amenable to automation but requires validation against the shake-flask method [2].

Table 1: Interpreting Lipophilicity Values

| LogP/LogD Value | Interpretation | Impact on Permeability & Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| < 0 | Hydrophilic / Low Lipophilicity | High aqueous solubility, low membrane permeability |

| 0 - 3 | Moderate Lipophilicity | Favorable balance for oral absorption; ideal range for many drugs |

| > 3 - 5 | High Lipophilicity | Lower solubility, higher permeability; increased risk of metabolic clearance |

| > 5 | Very High Lipophilicity | Very poor aqueous solubility, high permeability, poor ADMET profile |

Aqueous Solubility (LogS)

Fundamental Principles: Aqueous solubility (often expressed as LogS, the logarithm of the molar solubility) is the maximum amount of a solute that dissolves in a given volume of aqueous solution under specified conditions of temperature, pressure, and pH. It is a critical determinant of a drug's bioavailability, particularly for orally administered compounds, as a drug must be in solution to be absorbed [4]. Two key concepts are:

- Thermodynamic Solubility: The equilibrium concentration of a compound in a saturated solution where the solid phase is stable [4].

- Kinetic Solubility: The concentration at which a compound begins to precipitate from a supersaturated solution, often relevant in early discovery screens [4].

Experimental Protocols:

- Shake-Flask Method (for Thermodynamic Solubility): An excess of the solid compound is added to a buffered aqueous solution (e.g., at pH 7.4) and agitated for a prolonged period (e.g., 24-72 hours) to achieve equilibrium. The solution is then filtered or centrifuged to separate undissolved solid, and the concentration of the dissolved compound in the supernatant is quantified by a validated analytical method like HPLC-UV [4].

- Nephelometry / Turbidimetry (for Kinetic Solubility): A concentrated stock solution of the compound in DMSO is added incrementally to an aqueous buffer. The onset of precipitation is detected by an increase in light scattering (nephelometry) or absorbance (turbidimetry). This method is faster and requires less compound, making it suitable for high-throughput screening [4].

Acid Dissociation Constant (pKa)

Fundamental Principles: The pKa is the negative base-10 logarithm of the acid dissociation constant (Ka). It quantifies the tendency of a molecule to donate or accept a proton, defining its ionization state at a given pH [5] [6]. For a monoprotic acid (HA ⇌ H⁺ + A⁻), the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation describes the relationship between pH and the ratio of ionized ([A⁻]) to unionized ([HA]) species: pH = pKa + log₁₀([A⁻]/[HA]) A compound is 50% ionized and 50% unionized when the pH equals its pKa. The ionization state profoundly impacts a drug's lipophilicity, solubility, and membrane permeability, as only the unionized form can typically passively diffuse through lipid membranes [6].

Experimental Protocols:

- Potentiometric Titration: This is a standard methodology for determining pKa. A solution of the compound is titrated with a strong acid or base while continuously monitoring the pH. The pKa values are derived from the resulting titration curve. This method is effective for compounds with pKa values in the approximate range of 2-12 [5] [6].

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Titration: For compounds whose ionized and unionized forms have distinct UV-Vis absorption spectra, the pKa can be determined by monitoring spectral changes as a function of pH. This method is particularly useful for compounds with very high or low pKa values falling outside the optimal range for potentiometry [5].

Molecular Weight (MW)

Fundamental Principles: Molecular weight is the mass of a molecule, calculated as the sum of the atomic weights of its constituent atoms. It is a straightforward yet fundamental property that influences several other parameters, including melting point, diffusion rate, and, in conjunction with other properties, permeability. High molecular weight can complicate synthesis and formulation and is a key parameter in rules-based screening like the Rule of 5 [1] [3].

Experimental Protocols:

- Calculation: MW is trivially calculated from the molecular formula.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Experimental confirmation of a compound's molecular weight is typically achieved using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), which provides the exact mass of the molecular ion.

Computational Prediction and In Silico Methods

The integration of in silico tools in early drug discovery allows for the prioritization of compounds with desirable properties before synthesis.

Lipophilicity Prediction: Computational programs often use fragment-based or atom-contribution methods to calculate LogP (e.g., ALOGP, KLOGP) [1]. These methods assign values to molecular fragments and apply correction factors to estimate the overall partition coefficient.

Solubility Prediction: Machine learning (ML) has significantly advanced solubility prediction. Models use molecular descriptors (e.g., LogP, molecular weight, hydrogen bonding counts) or features derived from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations—such as Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) and Coulombic interaction energies—as input for ensemble algorithms like Gradient Boosting and Random Forest to predict LogS with high accuracy [4].

pKa Prediction: A variety of computational approaches exist, each with trade-offs between speed, accuracy, and interpretability [5] [7].

- Quantum Mechanics (QM) and MD Simulations: Physics-based methods like DFT and free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculations offer high accuracy and generality but are computationally expensive [7].

- Fragment-Based Methods: These use Hammett/Taft-style linear free-energy relationships and curated fragment libraries. They are fast and accurate within their domain of applicability but may generalize poorly [7].

- Data-Driven and Hybrid Methods: Machine learning models, including graph neural networks (GNNs), learn pKa relationships from large datasets of chemical structures. Hybrid approaches combine physics-based features with ML to improve robustness [7].

AI and Molecular Representation: Modern AI-driven methods leverage deep learning models such as graph neural networks (GNNs) and transformers. These models learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from molecular structures (e.g., SMILES strings or molecular graphs), enabling more accurate predictions of physicochemical properties and facilitating tasks like molecular generation and scaffold hopping [8] [9].

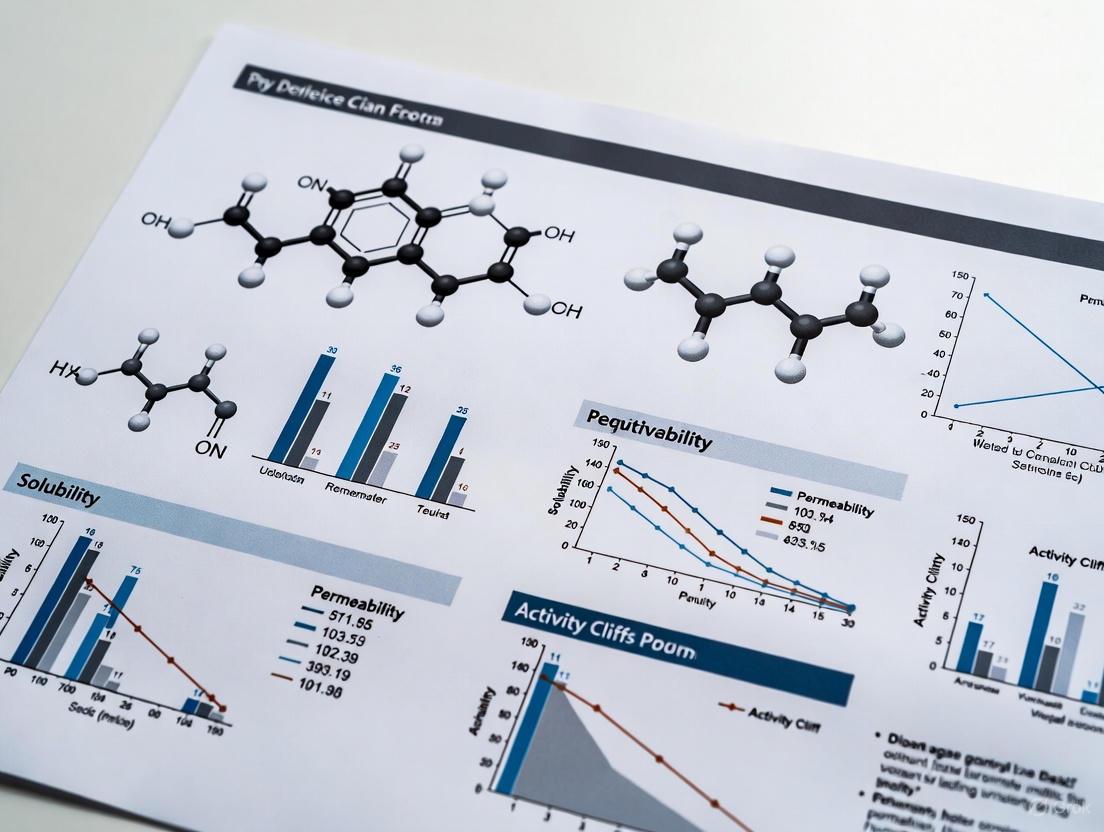

Diagram 1: Integrated Property Workflow. This diagram outlines the iterative cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation in modern drug design.

Interplay of Properties and Impact on Drug Disposition

The critical relationship between solubility and permeability is formally captured by the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), which categorizes drugs into four classes based on these two fundamental properties [1].

Table 2: The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS)

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Key Development Challenges | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Formulation robustness; chemical stability | Acyclovir, Captopril [1] |

| Class II | Low | High | Enhancing dissolution rate and extent; mitigating food effects | Atorvastatin, Diclofenac [1] |

| Class III | High | Low | Enhancing permeability; protecting from gut-wall metabolism | Cimetidine, Atenolol [1] |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Overcoming multiple barriers; often requires advanced formulations | Furosemide, Methotrexate [1] |

The ionization state of a molecule (governed by its pKa and the environmental pH) is a master regulator of its lipophilicity and solubility. This relationship is described by the following logical sequence, which is crucial for predicting a drug's absorption:

Diagram 2: Property Interplay Logic. This chart illustrates how pKa and pH determine ionization, which directly modulates the critical balance between solubility and lipophilicity/permeability.

For ionizable compounds, the total aqueous solubility (Saq) is a function of its intrinsic solubility (S0, the solubility of the neutral form) and its ionization. For a monoprotic acid, this is given by: log₁₀(Saq) = log₁₀(S0) + log₁₀(10^(pH-pKa) + 1) [10] This equation demonstrates how solubility increases for acids at high pH (where they are ionized) and for bases at low pH.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol / Buffer Systems | Immiscible solvent pair for experimental determination of LogP/LogD via the shake-flask method [2]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard aqueous buffer for maintaining physiological pH (e.g., 7.4) in solubility, permeability, and stability assays. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Biorelevant media (e.g., FaSSIF/FeSSIF) used to predict dissolution and solubility in the human GI tract. |

| ACD/Percepta Platform | Commercial software suite for predicting physicochemical properties including pKa, LogP, LogD, and solubility [5] [3]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprint generation, and informatics workflows [10]. |

| GROMACS | A versatile package for performing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, used to derive properties like solvation free energy [4]. |

Lipophilicity (LogP/LogD), solubility (LogS), pKa, and molecular weight are not mere numbers on a data sheet; they are interdependent principles that govern a molecule's journey from administration to action. A deep and quantitative understanding of these properties, facilitated by robust experimental protocols and advanced in silico predictions, is indispensable for making rational decisions in drug design. By systematically applying this knowledge within frameworks like the BCS, researchers can more effectively navigate the challenges of permeability and solubility, thereby reducing late-stage attrition and accelerating the development of safe and effective therapeutics.

The concept of 'drug-likeness' has undergone significant evolution since the introduction of Lipinski's Rule of Five over two decades ago. This whitepaper charts the progression from these foundational physicochemical rules to contemporary, holistic frameworks that govern modern drug design. We examine the original Rule of Five criteria and its limitations, the development of advanced classification systems like BDDCS, the critical role of in silico predictive tools, and the emerging integration of artificial intelligence in molecular design. Within the broader context of physicochemical property optimization in drug design research, this review provides researchers and development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide to current methodologies and future directions in predicting successful drug candidates.

The systematic study of drug-likeness represents a cornerstone of pharmaceutical research, providing crucial frameworks for predicting which chemical compounds possess the necessary physicochemical properties to become effective medications. The concept emerged from systematic observations that successful drugs often share common structural and physicochemical characteristics, even when targeting different biological pathways. Physicochemical properties form the fundamental basis for understanding drug-likeness, as they directly influence a compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile [11] [12]. These properties include lipophilicity, solubility, molecular size, polarity, and hydrogen bonding capacity, all of which interact in complex ways to determine a molecule's fate in biological systems.

For decades, drug discovery was hampered by high attrition rates in clinical development, with many failures attributable to suboptimal pharmacokinetic profiles [12]. This challenge prompted the development of predictive guidelines that could help medicinal chemists design compounds with a higher probability of success. The pioneering work of Christopher Lipinski and colleagues at Pfizer in 1997 marked a watershed moment in this endeavor, establishing simple, memorable rules that could be applied early in the drug discovery process to identify compounds with a higher likelihood of demonstrating oral bioavailability [13] [14].

Lipinski's Rule of Five: The Original Framework

The Four Criteria

Lipinski's Rule of Five emerged from an analysis of nearly 2,500 compounds that had reached Phase II clinical trials, identifying specific physicochemical boundaries associated with successful oral drugs [14]. The "Rule of Five" derives its name from the fact that all four criteria involve the number five or its multiples:

- Molecular weight (MW) ≤ 500 daltons

- Octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP) ≤ 5

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) ≤ 5

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) ≤ 10 [13] [14] [15]

The rule states that compounds violating more than one of these criteria are likely to exhibit poor absorption or permeation characteristics [13]. These parameters were selected because they directly influence key processes governing oral bioavailability, including solubility and intestinal permeability. Excessive molecular weight and lipophilicity can hinder a compound's ability to traverse biological membranes, while too many hydrogen bond donors and acceptors can negatively impact permeability by strengthening the hydration shell around the molecule [12].

Application and Impact in Drug Discovery

The Rule of Five provided medicinal chemists with a rapid assessment tool that could be applied during compound library design and lead optimization. Current statistics indicate that approximately 16% of oral medications violate at least one Rule of Five criterion, while only 6% violate two or more, confirming the rule's continued predictive value [14]. Adherence to these guidelines correlates with higher success rates in clinical trials, with compliant compounds demonstrating an average Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) score of 0.766 for approved oral formulations [14].

The application process involves systematic evaluation of each parameter [14]:

- Calculate Molecular Weight using molecular modeling software or online calculators

- Determine LogP through experimental measurement or computational prediction

- Count Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors through molecular structure analysis

- Evaluate Results and consider structural modifications for compounds with multiple violations

Table 1: Lipinski's Rule of Five Criteria and Their Rationale

| Parameter | Threshold | Physicochemical Basis | Impact on Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ≤ 500 Da | Influences molecular volume and diffusion rates | Excessive size impedes membrane permeability |

| LogP | ≤ 5 | Measures lipophilicity | High values reduce aqueous solubility; low values limit membrane penetration |

| H-Bond Donors | ≤ 5 | Counts OH and NH groups | Excessive donors strengthen hydration shell, reducing permeability |

| H-Bond Acceptors | ≤ 10 | Counts O and N atoms | High counts increase molecular polarity, affecting solubility and permeability |

Limitations and Exceptions to the Rule of Five

While revolutionary, Lipinski's Rule of Five was never intended as an absolute predictor of drug success, and its limitations have become increasingly apparent as chemical space exploration has expanded [13] [14].

Established Exceptions

Several important exception categories have been documented:

Biologics and Natural Products: Large molecule biologics, peptides, and natural products frequently violate multiple Rule of Five criteria while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [14]. For instance, many biologics exceed the molecular weight limit yet demonstrate substantial therapeutic value.

Alternative Administration Routes: The rule specifically predicts oral bioavailability, making it less relevant for drugs designed for intravenous, inhalation, transdermal, or other administration routes where absorption barriers differ [14]. Research indicates that over 98% of approved ophthalmic medications contain molecular descriptors within Rule of Five limits, yet effective exceptions exist [14].

Transporter-Mediated Uptake: The original Rule of Five assumed passive diffusion as the primary absorption mechanism. However, we now recognize that many successful drugs are substrates for active transporters that facilitate their absorption and distribution [13]. As noted in contemporary analyses, "almost all drugs are substrates for some transporter" [13].

Emerging Therapeutic Modalities: New drug classes including monoclonal antibodies, RNA-based therapies, and targeted protein degraders often fall outside traditional Rule of Five boundaries [14]. These innovative modalities challenge conventional understandings of drug-likeness and necessitate expanded criteria.

The "Beyond Rule of 5" (bRo5) Space

Recent years have seen increasing exploration of chemical space beyond Rule of Five constraints, particularly for challenging targets where extensive molecular interactions are required for potency and selectivity [16]. Kinase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and other targeted therapies often require molecular properties that exceed traditional limits while maintaining adequate bioavailability through specialized formulations or prodrug approaches [16].

Evolution to Advanced Classification Systems

The Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS)

The Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS) represents a significant advancement beyond the Rule of Five by incorporating metabolism as a key classification parameter [13]. Developed by Wu and Benet, BDDCS builds upon the foundation of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) but expands its predictive capability to encompass drug disposition and potential drug-drug interactions [13].

BDDCS classifies drugs into four categories based on their solubility and metabolism:

- Class 1: High solubility, high metabolism

- Class 2: Low solubility, high metabolism

- Class 3: High solubility, low metabolism

- Class 4: Low solubility, low metabolism [13]

This classification system successfully predicts disposition characteristics for both Rule of 5-compliant and non-compliant compounds, with analyses now encompassing over 1,100 drugs and active metabolites [13]. BDDCS provides particularly valuable insights into transporter effects, predicting that Class 1 drugs typically exhibit no clinically relevant transporter effects, while transporter interactions become increasingly important for Classes 2-4 [13].

Expanded Physicochemical Parameters

Modern drug-likeness assessment incorporates additional physicochemical parameters that provide a more comprehensive profiling of candidate compounds [11] [12]:

- Polar Surface Area (PSA): Predicts passive molecular transport through membranes and blood-brain barrier penetration [17]

- Molecular Flexibility: Measured by rotatable bond count, influences oral bioavailability and binding entropy

- Aromaticity: Impacts solubility, planar surface area for target interaction, and propensity for aggregation [12]

- Fraction of sp³ Carbons (Fsp³): Correlates with improved solubility and success in clinical development [12]

The concept of "molecular obesity" has emerged to describe the dangers of excessive lipophilicity-driven design strategies, characterized by an abundance of aromatic rings that increase molecular weight and lipophilicity disproportionately [12]. This can lead to suboptimal drug candidates with reduced solubility, higher molecular size, and increased nonspecific interactions.

Table 2: Advanced Physicochemical Parameters in Modern Drug Design

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Optimal Range | Significance in Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | Sum of surfaces of polar atoms | ≤ 140 Ų for good oral bioavailability | Predicts passive transport through membranes |

| Rotatable Bond Count | Number of non-terminal flexible bonds | ≤ 10 | Influences oral bioavailability and binding entropy |

| Fraction of sp³ Carbons | sp³ hybridized carbons/total carbon count | > 0.42 | Higher saturation correlates with better developability |

| Aromatic Ring Count | Number of aromatic rings | ≤ 3 | Reduces molecular planarity and improves solubility |

Contemporary Experimental and Computational Methodologies

In Silico ADME Prediction Platforms

The development of comprehensive computational ADME prediction tools represents a major advancement in drug-likeness assessment. Platforms such as SwissADME provide free web-based tools that evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry friendliness [17]. These tools integrate multiple predictive models for critical parameters:

- Lipophilicity Prediction: Consensus log P values from multiple methods including iLOGP, XLOGP3, and WLOGP [17]

- Solubility Prediction: Topological methods using ESOL and Ali methods [17]

- Bioavailability Radar: Rapid visual assessment of drug-likeness across six key physicochemical properties [17]

- BOILED-Egg Model: Prediction of gastrointestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier penetration [18] [17]

These computational tools enable rapid evaluation of compound libraries prior to synthesis, significantly accelerating the lead optimization process [17].

High-Throughput Physicochemical Assays

Modern drug discovery employs high-throughput experimental assays to efficiently profile key physicochemical properties [12]:

- Lipophilicity Measurement: Using chromatographic techniques such as immobilized artificial membrane (IAM) chromatography and reversed-phase HPLC

- Solubility Assessment: High-throughput shake-flask and kinetic solubility methods

- Permeability Evaluation: PAMPA (Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay) and cell-based models like Caco-2

These experimental approaches generate critical data for structure-property relationship analysis and validate computational predictions [12].

Figure 1: Modern Workflow for Drug-Likeness Assessment Integrating Traditional and AI-Based Approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Modern Drug-Likeness Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissADME [17] | Computational Platform | Multi-parameter ADME prediction | Early-stage compound prioritization |

| BOILED-Egg Model [18] [17] | Predictive Model | GI absorption and BBB penetration prediction | Lead compound selection for CNS targets |

| Human Serum Albumin Columns [12] | Chromatographic Tool | Plasma protein binding assessment | Distribution and free fraction estimation |

| Immobilized Artificial Membrane [12] | Chromatographic Tool | Biomimetic permeability screening | Passive membrane permeation prediction |

| Caco-2 Cell Lines [12] | Biological Model | Intestinal permeability assessment | Absorption potential for oral drugs |

| Hepatocyte Assays [13] | Biological Model | Metabolic stability evaluation | Clearance prediction and metabolite identification |

Emerging Frontiers: AI and Generative Models in Molecular Design

The integration of artificial intelligence represents the most recent evolution in drug-likeness optimization. Generative models (GMs) employing variational autoencoders (VAEs) combined with active learning (AL) cycles can now design novel molecules with tailored physicochemical properties and predicted bioactivity [19].

These advanced systems operate through structured pipelines:

- Molecular Representation: Compounds are encoded as SMILES strings and converted to numerical representations

- Initial Training: Models are trained on general chemical libraries followed by target-specific fine-tuning

- Active Learning Cycles: Iterative refinement using chemoinformatic and molecular modeling oracles

- Candidate Selection: Stringent filtration based on synthetic accessibility, drug-likeness, and predicted affinity [19]

This approach has demonstrated remarkable success in generating novel scaffolds for challenging targets like CDK2 and KRAS, with experimentally confirmed activity including nanomolar potency in some cases [19]. The integration of physics-based molecular modeling with data-driven generative AI creates a powerful framework for exploring previously inaccessible regions of chemical space while maintaining desirable drug-like properties.

The evolution from Lipinski's Rule of Five to modern drug-likeness guidelines reflects the pharmaceutical industry's growing sophistication in understanding the complex interplay between molecular structure, physicochemical properties, and biological outcomes. While the Rule of Five established crucial foundational principles that remain relevant today, contemporary drug discovery has moved toward multi-parameter optimization frameworks that balance permeability, solubility, metabolic stability, and transporter effects.

The future of drug-likeness assessment lies in the intelligent integration of computational prediction, high-throughput experimentation, and generative AI approaches that can navigate the complex trade-offs inherent in molecular design. As chemical space continues to expand beyond traditional Rule of Five boundaries, these advanced methodologies will prove increasingly vital for addressing challenging therapeutic targets and developing innovative medicines for patients in need.

The successful development of orally bioavailable drugs hinges on the meticulous optimization of key physicochemical properties, primarily lipophilicity and molecular size. These parameters are fundamental determinants of a compound's behavior in vivo, directly influencing its absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on the critical relationships between lipophilicity, molecular size, and ADMET outcomes. It details established and emerging experimental protocols for measuring these properties, visualizes their impact on biological pathways, and presents a curated toolkit for researchers. Framed within the broader thesis of rational drug design, this review underscores the necessity of balancing these physicochemical properties to navigate the delicate trade-off between biological potency and desirable pharmacokinetics.

In the realm of drug discovery, physicochemical properties form the foundational blueprint that dictates a molecule's pharmacological fate. Among these, lipophilicity and molecular size stand out as paramount drivers of ADMET characteristics [20] [2]. Lipophilicity, quantitatively expressed as the partition coefficient (LogP) or the distribution coefficient (LogD) at physiological pH, measures a compound's affinity for a lipophilic phase (e.g., octanol) versus an aqueous phase (e.g., water) [2]. Molecular size, often represented by molecular weight (MW), influences a compound's ability to diffuse through membranes and its solvation energy [21].

The seminal Lipinski's Rule of Five established an early framework, stating that for good oral absorption, a molecule should typically have: MW ≤ 500, LogP ≤ 5, hydrogen bond donors (HBD) ≤ 5, and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) ≤ 10 [22] [23]. Subsequent rules by Veber et al. emphasized additional parameters like topological polar surface area (TPSA) ≤ 140 Ų and rotatable bonds ≤ 10 [22]. However, the evolution of drug targets, particularly towards protein-protein interactions (PPIs), has pushed the boundaries of these rules. Modern analyses reveal that PPI inhibitors (iPPIs) and other new modalities often exhibit higher average MW (≈521 Da) and LogP (≈4.8) compared to traditional small molecules, presenting unique ADMET challenges that require advanced design and formulation strategies [20] [21].

The Impact of Lipophilicity and Size on ADMET Properties

Absorption and Permeability

Lipophilicity plays a dual role in absorption. A compound requires sufficient lipophilicity to passively diffuse across the lipid bilayers of the gastrointestinal tract [20]. However, excessive lipophilicity (LogP > 5) often leads to poor aqueous solubility, creating a dissolution-rate limited absorption and reducing bioavailability [20] [2]. The molecular size and polar surface area (PSA) are equally critical; high TPSA, often correlated with larger size and increased HBD/HBA count, generally decreases membrane permeability [22] [21]. For instance, cyclic peptides like cyclosporin achieve oral bioavailability despite a high MW (1202 Da) through "chameleonic" properties, where their conformation shifts in different environments to mask polar surfaces and enable membrane permeability [22].

Distribution and Tissue Penetration

The distribution of a drug throughout the body is heavily influenced by its lipophilicity. Higher LogP values increase the volume of distribution and enhance penetration into fatty tissues and cells [20]. This can be beneficial for drugs targeting intracellular sites but problematic for those needing high plasma concentrations. Furthermore, highly lipophilic drugs are more prone to nonspecific binding to plasma proteins and tissues, which can reduce the free fraction available for pharmacological activity [2]. Moderately lipophilic compounds (LogP ~2) are often optimal for crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [24].

Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity

Lipophilicity is a key determinant of metabolic clearance. Drugs with high LogP are more readily metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, potentially leading to a short half-life and the generation of reactive, toxic metabolites [20] [23]. Elevated lipophilicity and molecular size are also strongly correlated with promiscuous target binding and off-target toxicity, including inhibition of the hERG channel, which is linked to cardiotoxicity [21] [23]. Larger, more complex molecules are also more likely to be substrates for efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which can limit their intestinal absorption and brain penetration [22] [23].

Table 1: Optimal Ranges for Key Physicochemical Properties in Oral Drug Design

| Property | Optimal Range for Oral Drugs | ADMET Impact of High Values | Key Supporting Rules/Filters |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogP/LogD | 1 - 5 | Poor solubility, high metabolism, tissue accumulation, toxicity | Lipinski's Rule of Five (LogP ≤ 5) [23] |

| Molecular Weight | ≤ 500 | Reduced permeability, increased efflux by transporters | Lipinski's Rule of Five (MW ≤ 500) [23] |

| Topological Polar Surface Area | ≤ 140 Ų | Low membrane permeability | Veber's Rule (TPSA ≤ 140 Ų) [22] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors | ≤ 5 | Low permeability, poor absorption | Lipinski's Rule of Five (HBD ≤ 5) [23] |

| Rotatable Bonds | ≤ 10 | Increased metabolic flexibility, potentially faster clearance | Veber's Rule (Rotatable Bonds ≤ 10) [22] |

Quantitative Analysis and Trends in Modern Drug Discovery

Computational analyses of large compound datasets reveal distinct trends for different drug classes. A study comparing enzymes, GPCRs, ion channels, nuclear receptors, and iPPIs found that iPPIs have the highest mean MW (521 Da) and among the highest mean LogP values (4.8) [21]. This reflects the nature of PPI interfaces, which are large and relatively flat, requiring larger, often more lipophilic, molecules for effective inhibition.

Historically, the proportion of highly polar molecules (LogP < 0) in drug discovery pipelines has decreased, contributing to a gradual increase in the median LogP of approved drugs over the past decades [20]. Data indicates the average LogP has increased by approximately one unit over twenty years, equating to a tenfold increase in lipophilicity [20]. This shift is partly attributed to a move away from natural product-inspired discovery, which often yielded highly hydrophilic compounds, towards targeted discovery of fully synthetic molecules [20].

Table 2: Comparative Physicochemical Properties Across Different Compound Classes

| Compound Class | Mean MW (Da) | Mean LogP | Mean HBD | Mean TPSA (Ų) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Marketed Drugs | ~360 | ~2.5 | 1.7 | ~90 |

| iPPIs (PPI Inhibitors) | 521 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 101 |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | ~400 | ~2.8 | ~2.5 | 108 |

| GPCR Ligands | ~430 | ~3.5 | 1.8 | ~80 |

| Nuclear Receptor Ligands | ~480 | ~4.5 | 1.5 | ~70 |

Essential Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Lipophilicity (LogP/LogD)

Shake-Flask Method: This is the considered gold standard for experimental LogP/LogD determination [2]. The protocol involves:

- Preparation: A compound of interest is dissolved in a pre-saturated mixture of 1-octanol and a buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 for LogD).

- Equilibration: The mixture is shaken vigorously for a set period to allow partitioning between the two phases and then centrifuged to achieve complete phase separation.

- Quantification: The concentration of the compound in each phase is quantified using a sensitive analytical technique, typically high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV or mass spectrometry detection.

- Calculation: LogP/LogD is calculated as the logarithm of the ratio of the compound's concentration in the octanol phase to its concentration in the aqueous phase.

Reversed-Phase Thin-Layer Chromatography (RP-TLC): This method offers a high-throughput, low-cost alternative [24]. The procedure is as follows:

- Chromatography: The test compound is spotted on a reversed-phase TLC plate (e.g., C18-coated silica gel). The plate is developed in a chromatographic chamber containing a mobile phase of water mixed with a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile).

- Measurement: The retention factor (RM) is calculated from the distance migrated by the compound spot.

- Calibration: RM values are determined using several mobile phase compositions. The RM0 value, obtained by extrapolation to 0% organic modifier, is a reliable chromatographic descriptor of lipophilicity and can be correlated with LogP [24].

Immobilized Artificial Membrane (IAM) Chromatography: This technique uses stationary phases that mimic cell membranes more closely than octanol, potentially providing a better correlation with cellular permeability [2].

Assessing Membrane Permeability

Caco-2 Cell Model: This is a widely used in vitro model for predicting intestinal absorption.

- Culture: Human colon adenocarcinoma Caco-2 cells are cultured on semi-permeable filters until they differentiate into a monolayer that resembles the intestinal epithelium.

- Dosing: The test compound is added to the apical compartment (representing the intestinal lumen).

- Sampling: Samples are taken from the basolateral compartment over time and analyzed to determine the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp).

- Analysis: High Papp values indicate high permeability. The integrity of the monolayer is verified by measuring trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and using low-permeability marker compounds [23].

Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA): PAMPA is a high-throughput, non-cell-based assay that uses a lipid-infused filter to simulate passive transcellular permeability [23].

Visualizing the Relationship: From Molecular Properties to ADMET Outcomes

The following diagram synthesizes the core relationships between molecular properties, their key influences, and the resulting ADMET outcomes, providing a conceptual roadmap for researchers.

Diagram 1: ADMET Property Relationship Map. This map visualizes how increased lipophilicity and molecular size drive key physicochemical effects that ultimately determine critical ADMET outcomes. The experimental workflow for characterizing a compound's properties and predicting its ADMET profile involves a combination of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methods, as outlined below.

Diagram 2: Property Determination and ADMET Prediction Workflow. The standard pipeline begins with computational prediction, proceeds through experimental validation of key physicochemical properties, and culminates in in vivo studies to confirm pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behavior.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Property Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol / Buffer Systems | Gold standard solvent system for shake-flask LogP/LogD determination. | Pre-saturate phases with each other before use to ensure volume stability [2]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro model of human intestinal permeability and active transport. | Monitor TEER and use control compounds to validate monolayer integrity [23]. |

| Reversed-Phase TLC Plates | High-throughput, low-cost chromatographic estimation of lipophilicity (RM0). | Ideal for early-stage discovery; requires a calibration curve for LogP correlation [24]. |

| PAMPA Plates | High-throughput assay for passive transcellular permeability. | Lipid composition can be customized to mimic different biological barriers (e.g., BBB) [23]. |

| admetSAR 2.0 | A comprehensive, free web server for predicting chemical ADMET properties. | Integrates 18+ predictive models; useful for virtual screening and prioritization [23]. |

| SwissADME | A free web tool to compute physicochemical descriptors, drug-likeness, and ADME parameters. | Provides multiple LogP predictors and a boiled-eye representation of drug-likeness [24]. |

| Absorption Enhancers (e.g., SNAC, C8) | Facilitate oral absorption of middle-to-large molecules (e.g., peptides). | Used in approved drugs (Rybelsus, Mycapssa); mechanism includes transient permeability increase [22]. |

| Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems (LBDDS) | Formulation strategy to enhance solubility and absorption of lipophilic drugs. | Includes self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) and drug-loaded micelles [20]. |

Lipophilicity and molecular size are indispensable, interconnected properties that sit at the heart of drug design. Their profound influence on every aspect of ADMET necessitates a careful balancing act throughout the discovery process. While trends in modern drug discovery, such as the targeting of PPIs, are pushing molecules towards higher molecular weight and lipophilicity, this must be counterbalanced by sophisticated formulation technologies and a deep understanding of property-based design rules. The future of successful drug development lies in the intelligent application of the experimental and computational tools outlined herein, enabling researchers to strategically optimize these fundamental physicochemical properties to achieve the ultimate goal: efficacious and safe medicines.

The pursuit of high-affinity ligands in drug discovery has inadvertently fostered a problematic trend toward increasingly lipophilic and complex molecular structures, a phenomenon widely termed 'molecular obesity'. This tendency represents a significant challenge in pharmaceutical development, where an overreliance on lipophilic interactions to drive target affinity often results in compounds with suboptimal physicochemical properties [25] [12]. These molecules, characterized by excessive molecular weight and lipophilicity, frequently demonstrate poor solubility, inadequate absorption, and increased metabolic instability, ultimately contributing to higher rates of attrition in later development stages [25].

The chemical basis of lipophilicity arises from a molecule's affinity for non-polar environments, driven by hydrophobic moieties such as alkyl chains and aromatic rings which minimize polar interactions with water [12]. While moderate lipophilicity is essential for membrane permeability and target engagement, excessive values disrupt the delicate balance required for optimal drug disposition. Contemporary drug discovery has observed a steady increase in the average lipophilicity of investigational compounds, partly attributable to the pursuit of challenging targets like protein-protein interactions which often require larger, more lipophilic molecules for effective inhibition [25] [26]. This review examines the critical relationship between elevated lipophilicity and compound attrition, establishes methodological frameworks for its assessment, and proposes strategic approaches to mitigate associated risks in the drug development pipeline.

The Structural and Energetic Basis of Molecular Obesity

Molecular Drivers and Energetic Implications

The propensity toward molecular obesity often stems from design strategies that prioritize target affinity above all other considerations. Aromatic rings, while conferring structural stability and favorable binding interactions, disproportionately increase molecular weight and lipophilicity when incorporated excessively [12]. This "lipophilicity addiction" reflects a reliance on hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions, which are entropically driven and relatively straightforward to optimize compared to more specific enthalpic interactions like hydrogen bonding and electrostatic contacts [25].

The thermodynamic signature of high-quality drugs typically reveals a significant enthalpic contribution to binding energy, whereas molecularly obese compounds often depend predominantly on entropic gains derived from lipophilic interactions [25]. This distinction carries profound implications for drug specificity and safety, as enthalpically-driven binders typically demonstrate superior selectivity profiles due to the requirement for more precise complementarity with their biological targets. The optimization process itself contributes to this problem; refining the entropic component of binding energy through increased lipophilicity is synthetically more accessible than engineering specific enthalpic interactions, creating a natural trajectory toward heavier, more lipophilic molecules during lead optimization [25].

Table 1: Structural Features Associated with Molecular Obesity

| Structural Element | Impact on Properties | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive aromatic rings | Increased molecular weight & lipophilicity | Reduced solubility, promiscuous binding |

| High alkyl chain content | Elevated logP | Increased metabolic instability, tissue accumulation |

| Limited polar functionality | Decreased solubility | Poor oral bioavailability |

| Large molecular framework | Increased rotatable bonds & TPSA | Impaired membrane permeability |

Quantitative Assessment Using Efficiency Metrics

To combat the trend toward molecular obesity, medicinal chemists have developed efficiency metrics that contextualize biological activity relative to molecular size and lipophilicity. Ligand efficiency (LE) normalizes binding affinity against heavy atom count, providing a measure of potency per unit molecular size [25] [12]. Similarly, lipophilic efficiency (LipE) relates potency to lipophilicity by subtracting the logP from a measure of biological activity (typically pIC50) [12]. These metrics enable objective assessment of compound quality during lead optimization, helping researchers identify candidates that achieve potency through specific, high-quality interactions rather than mere hydrophobic bulk.

The application of these metrics reveals alarming trends in contemporary drug discovery. Analyses of candidate compounds demonstrate a steady increase in molecular weight and lipophilicity compared to drugs launched in the late 20th century [25]. This "molecular inflation" frequently corresponds with decreased developability, as excessively lipophilic compounds face greater challenges with formulation, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity. Monitoring lipophilic ligand efficiency throughout optimization campaigns provides an early warning system for molecular obesity, allowing teams to maintain focus on compounds with balanced physicochemical profiles [25].

Experimental Determination of Lipophilicity

Chromatographic Methods for Lipophilicity Assessment

Accurate determination of lipophilicity is fundamental to understanding compound behavior in biological systems. While the traditional shake-flask method remains the gold standard for direct logP measurement, it suffers from limitations including time-consuming procedures, strict purity requirements, and a constrained measurement range (typically -2 < logP < 4) [27] [28]. These challenges have motivated the development of reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) methods that offer rapid analysis, minimal sample requirements, and extended detection ranges (logP 0-6) [27].

In RP-HPLC, a compound's lipophilicity is correlated with its retention time on a non-polar stationary phase. The affinity for the stationary phase is quantified by the capacity factor (k), calculated as k = (tR - t0)/t0, where tR is the retention time of the compound and t0 is the dead time of the system [28]. By measuring k values at different mobile phase compositions and extrapolating to 100% aqueous conditions, researchers can derive logkw, a chromatographic lipophilicity index that closely correlates with shake-flask logP values [27] [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Lipophilicity Measurement Methods

| Method | Measurement Range (logP) | Speed | Sample Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask | -2 to 4 | Slow | High purity, mg quantities | Direct measurement, regulatory acceptance | Time-consuming, limited range |

| RP-HPLC (Isocratic) | 0 to 6 | Rapid (≤30 min/sample) | Low purity, µg quantities | Broad range, high throughput | Indirect measurement |

| RP-HPLC (Gradient) | 0 to 6 | Moderate (2-2.5 h/sample) | Low purity, µg quantities | High accuracy, logkw determination | More complex implementation |

| Computer Simulation | Broad | Instant | None | Cost-effective, early screening | Accuracy depends on algorithm |

Detailed RP-HPLC Protocol for Lipophilicity Determination

The following protocol outlines the establishment of an RP-HPLC method for rapid lipophilicity screening during early drug discovery [27]:

Reference Compound Selection: Six reference compounds with known logP values spanning a wide lipophilicity range (e.g., 4-acetylpyridine, logP 0.5; acetophenone, logP 1.7; chlorobenzene, logP 2.8; ethylbenzene, logP 3.2; phenanthrene, logP 4.5; triphenylamine, logP 5.7) are selected to establish the calibration curve.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., LiChroCART Purosphere RP-18e, 125 mm × 3 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Binary gradient of methanol and water (with 0.1% formic acid)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV absorbance at 254 nm

- Column Temperature: 22°C or 37°C to mimic physiological conditions

- Injection Volume: 1 μL of 1 mg/mL solution

System Calibration: The retention time of each reference compound is measured, and capacity factors (k) are calculated. A standard equation is generated by plotting logk against known logP values: logP = a × logk + b. The correlation coefficient (R²) should exceed 0.97 to meet regulatory requirements [27].

Sample Analysis: Test compounds are analyzed under identical conditions, their capacity factors are calculated, and logP values are determined using the established standard equation.

For enhanced accuracy in late-stage development, a modified approach replaces logk with logkw (the capacity factor in pure aqueous mobile phase), which is determined by measuring k values at multiple methanol concentrations and extrapolating to 0% organic modifier [27]. This method achieves superior correlation (R² > 0.996) with reference values by eliminating the confounding effects of organic modifiers on retention behavior.

Figure 1: RP-HPLC Lipophilicity Determination Workflow

The Correlation Between High Lipophilicity and Compound Attrition

Impact on Pharmacokinetics and Safety Profiles

Excessive lipophilicity directly influences multiple aspects of a compound's disposition and safety profile, contributing significantly to developmental attrition. Poor aqueous solubility remains a primary challenge, as lipophilic compounds often require sophisticated formulation approaches to achieve adequate exposure [12]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in oral dosage forms, where dissolution rate and extent directly impact bioavailability. Furthermore, highly lipophilic compounds demonstrate increased nonspecific tissue binding and volume of distribution, which can reduce free drug concentrations at the target site while increasing accumulation in adipose tissues and prolonging elimination half-lives [12].

The metabolic fate of lipophilic compounds also presents development challenges. These molecules are more susceptible to oxidative metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzymes, leading to unpredictable drug-drug interactions and potential toxicity from reactive metabolites [25] [12]. Additionally, their tendency toward phospholipidosis—accumulation within cellular membranes—can disrupt normal organelle function and contribute to organ-specific toxicity. Perhaps most concerning is the correlation between high lipophilicity and promiscuous target engagement, where compounds interact with multiple unintended biological targets, resulting in off-target pharmacology and adverse effects [25].

Quantitative Relationships Between Lipophilicity and Attrition

Retrospective analyses of compound success rates reveal striking correlations between lipophilicity and developmental outcomes. Candidates with logP > 3 demonstrate significantly higher attrition due to toxicity and pharmacokinetic issues compared to those with lower lipophilicity [25]. This relationship persists across multiple therapeutic areas, suggesting fundamental limitations in the developability of highly lipophilic molecules. The introduction of lipophilic efficiency metrics has enabled quantitative assessment of this risk, with LipE < 5 often predicting increased likelihood of failure in development [12].

The impact of molecular obesity extends beyond individual compounds to influence portfolio management decisions. Development programs featuring lead compounds with optimized lipophilicity profiles demonstrate higher success rates in early clinical trials, reducing costly late-stage failures [25]. This evidence supports the implementation of lipophilicity guidelines during lead optimization, where maintaining logP < 5 and LipE > 5 significantly enhances the probability of technical success [12].

Figure 2: Consequences of High Lipophilicity in Drug Development

Mitigation Strategies and Design Principles

Rational Approaches to Control Lipophilicity

Successful mitigation of molecular obesity requires deliberate design strategies throughout the drug discovery process. Property-based design emphasizes the maintenance of optimal physicochemical properties during lead optimization, rather than focusing exclusively on potency improvements [25] [12]. This approach incorporates structure-activity relationships (SAR) with structure-property relationships (SPR) to balance target affinity with developability. Critical to this strategy is the early implementation of efficiency metrics (LE and LipE) as key decision-making parameters, ensuring that potency gains achieved through increased lipophilicity are properly contextualized [12].

Molecular design tactics to reduce lipophilicity while maintaining potency include:

- Bioisosteric replacement of aromatic rings with saturated or partially saturated counterparts

- Introduction of polar substituents to improve solubility and reduce logP

- Molecular simplification to remove non-essential hydrophobic groups

- Conformational constraint to improve potency without adding molecular weight

These approaches require sophisticated synthetic and analytical support but yield compounds with superior developmental prospects compared to their molecularly obese counterparts [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Lipophilicity Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Compound Set | Calibration standard for chromatographic methods | RP-HPLC method development and validation |

| RP-18 Chromatographic Column | Non-polar stationary phase for retention measurement | Standard lipophilicity screening via RP-HPLC |

| Specialized Columns (C8, C16-Amide, PFP) | Alternative stationary phases with different selectivity | Comprehensive lipophilicity profiling [28] |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Organic modifier for mobile phase | Chromatographic separation |

| n-Octanol and Buffer Solutions | Phases for shake-flask partition experiments | Direct logP measurement (gold standard) |

| Immobilized Artificial Membrane (IAM) Columns | Biomimetic stationary phase | Membrane partitioning prediction |

| Software for in silico Prediction | Computational logP estimation | Early-stage compound design and virtual screening |

The phenomenon of molecular obesity represents a significant challenge to pharmaceutical productivity, contributing to elevated attrition rates through suboptimal pharmacokinetics and increased toxicity. The correlation between excessive lipophilicity and compound failure underscores the importance of physicochemical property optimization throughout the drug discovery process. By implementing rigorous lipophilicity assessment protocols, including efficient chromatographic methods, and adhering to design principles that prioritize balanced physicochemical profiles, research teams can significantly improve the likelihood of technical success. The integration of efficiency metrics and property-based design into lead optimization represents a critical strategy for developing safer, more effective therapeutics with reduced developmental risk. As drug discovery ventures into increasingly challenging target spaces, maintaining discipline against molecular obesity will be essential for delivering the next generation of innovative medicines.

From Prediction to Practice: Computational and Experimental Methods for Property Optimization

The process of drug discovery is notoriously protracted, often spanning 10–15 years and requiring investments that can exceed $2.8 billion to bring a single candidate to market [29]. A significant contributor to these high costs and extended timelines is the late-stage failure of drug candidates due to efficacy and toxicity issues that could, in principle, be predicted from molecular structure [29]. Within this challenging landscape, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling have emerged as indispensable computational methodologies. These approaches are founded on the principle that the biological activity and physicochemical properties of a compound are deterministic functions of its molecular structure [30]. By mathematically correlating numerical descriptors of chemical structures with experimentally measured biological or physicochemical endpoints, QSAR/QSPR models enable the in silico prediction of key properties for novel compounds prior to their synthesis or biological testing. This predictive capability allows researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates for expensive experimental validation, thereby accelerating lead optimization and reducing attrition rates in later development stages [31].

The application of QSAR/QSPR modeling extends throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial hit identification to lead optimization and even toxicity prediction. These models have been successfully deployed to predict a diverse array of properties critical to drug performance, including boiling point, enthalpy of vaporization, molar refractivity, polarizability, soil adsorption coefficients (Koc) for environmental risk assessment, and complex biological activities against therapeutic targets such as Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) [30] [32] [29]. The evolution of these models from simple linear regressions to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches has fundamentally transformed their predictive power and applicability, establishing them as veritable powerhouses in modern computational drug design [31].

Theoretical Foundations of QSAR/QSPR

Fundamental Principles and Historical Context

The conceptual foundation of QSAR/QSPR was laid in the 19th century when Crum-Brown and Fraser first postulated that the biological activity and physicochemical properties of molecules are inherent functions of their chemical structures [29]. The core principle is encapsulated in the mathematical expression: Activity/Property = f (physiochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [33] This equation establishes that a quantifiable relationship exists between a molecule's structural features (represented by molecular descriptors) and its observable behavior, with the error term accounting for both model inaccuracies and experimental variability.

A related fundamental concept is the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), which posits that similar molecules typically exhibit similar biological activities. However, this principle is tempered by the "SAR paradox," which acknowledges that not all similar molecules display similar activities—a critical consideration that underscores the complexity of molecular interactions in biological systems [33]. The related term QSPR is used specifically when the modeled response variable is a chemical property rather than a biological activity [33].

Molecular Descriptors: Encoding Chemical Information

Molecular descriptors are numerical quantifiers that capture specific aspects of molecular structure and properties, serving as the independent variables in QSAR/QSPR models. These descriptors are broadly categorized based on the dimensionality of the structural information they encode [31]:

- 1D Descriptors: These represent bulk properties of the molecule without structural detail, such as molecular weight, atom count, and bond count.

- 2D (Topological) Descriptors: Derived from the molecular graph (atoms as vertices, bonds as edges), these capture structural connectivity. Examples include the Atom Bond Connectivity (ABC) index, Sombor index, Hyper Zagreb index, and various Zagreb indices [34]. Their calculation for drugs like Cladribine demonstrates their application: for instance, the Revised First Zagreb Index (ReZG₁) is calculated by summing the term (d(u) + d(v))/(d(u) × d(v)) for all edges uv in the molecular graph, where d(u) and d(v) are the degrees of the connected atoms [34].

- 3D Descriptors: These utilize the three-dimensional geometry of molecules, capturing features like molecular surface area, volume, and stereochemistry.

- 4D Descriptors: An advanced category that accounts for conformational flexibility by using ensembles of molecular structures rather than a single static conformation [31].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Derived from quantum mechanical calculations, these include properties such as HOMO-LUMO energy gaps, dipole moments, and electrostatic potential surfaces, which are particularly valuable for modeling electronic properties that influence bioactivity [31].

Table 1: Classification of Key Molecular Descriptors in QSAR/QSPR Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Representative Examples | Information Encoded | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological (2D) | ABC Index, Sombor Index, Zagreb Indices [34] | Molecular connectivity & branching | Predicting bioavailability, stability [34] |

| Geometrical (3D) | Molecular Surface Area, Volume | 3D shape & size | Protein-ligand docking, binding affinity |

| Quantum Chemical | HOMO-LUMO Gap, Dipole Moment [31] | Electronic distribution & reactivity | Mechanism of action, reactivity studies |

| Constitutional (1D) | Molecular Weight, Heavy Atom Count [30] | Bulk composition | Preliminary screening, rule-of-5 compliance |

Methodological Workflow for QSAR/QSPR Model Development

Constructing a robust and predictive QSAR/QSPR model is a multi-stage process that demands rigorous execution at each step. The following workflow, depicted in the diagram below, outlines the critical path from data collection to model deployment.

Data Set Selection and Curation

The process begins with assembling a high-quality dataset of compounds with reliably measured biological activities or physicochemical properties. The activity data, such as IC₅₀ (half-maximal inhibitory concentration), should be obtained through standardized experimental protocols to ensure consistency [29]. For example, a study on NF-κB inhibitors collected IC₅₀ values for 121 compounds from the scientific literature [29]. Data curation is critical and involves checking for errors, removing duplicates, and standardizing chemical structures (e.g., correcting tautomeric forms, neutralizing charges) to ensure data integrity [35].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

Following data collection, molecular descriptors are calculated for each compound using specialized software. The initial descriptor pool can be extensive, often containing hundreds or thousands of variables. Data preprocessing is therefore essential to reduce noise and prevent model overfitting. This includes:

- Normalization/Standardization: Scaling descriptors to a common range to prevent variables with large numerical ranges from dominating the model.

- Dataset Splitting: The curated dataset is typically divided into a training set (≈75-80%) for model development and a test set (≈20-25%) for external validation. Splitting should be strategic, such as using a Y-ranking method to ensure both sets represent a similar range of activity values [32].

Feature Selection and Model Construction

Feature selection identifies the most relevant descriptors, creating a robust and interpretable model. Techniques range from simple Genetic Algorithms [35] to more advanced methods like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) [31]. The goal is to select a small set of non-redundant, mechanistically interpretable descriptors that show a strong correlation with the target property.

Model construction involves choosing the appropriate algorithmic approach to define the mathematical relationship Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃...). The choice of algorithm depends on the data's nature and complexity.

Table 2: Comparison of QSAR/QSPR Modeling Algorithms

| Modeling Algorithm | Type | Key Advantages | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) [29] | Classical / Linear | Simple, highly interpretable, fast | Initial modeling, establishing clear structure-property trends [29] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) [33] | Classical / Linear | Handles descriptor collinearity | Modeling with correlated descriptors |

| Random Forest (RF) [31] | Machine Learning (Non-linear) | Robust to noise, built-in feature importance | Virtual screening, complex activity prediction [31] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) [32] | Machine Learning (Non-linear) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces | Toxicity prediction, classification tasks |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [29] | Machine Learning (Non-linear) | Captures highly complex non-linear relationships | Lead optimization, property prediction [29] |

Model Validation and Applicability Domain

Validation is the cornerstone of establishing a model's reliability and predictive power for new compounds. It involves multiple stringent checks:

- Internal Validation: Assesses the model's robustness within the training data, primarily through cross-validation (e.g., fivefold cross-validation). A common metric is Q² (cross-validated R²), with values above 0.5-0.6 generally considered acceptable [35]. Y-scrambling is used to verify the absence of chance correlations by randomizing the response variable and confirming that the resulting models perform poorly [33].

- External Validation: The true test of a model's predictive ability is its performance on the previously unseen test set. The model is used to predict the activities of the test set compounds, and the predicted values are compared against the experimental values. The R² value for the test set is a key indicator of external predictivity [33].

- Applicability Domain (AD): A critical concept defining the chemical space within which the model can make reliable predictions. A model is only reliable for compounds structurally similar to those in its training set. The leverage method is one approach to define the AD, identifying when a new compound is an outlier for which predictions should not be trusted [29].

Advanced Applications and a Case Study in Coronary Artery Disease

Case Study: Eccentricity-Based QSPR Modeling for CAD Drugs

A 2025 study on coronary artery disease (CAD) drugs provides an excellent example of a modern QSPR application. The research aimed to predict key physicochemical properties—including boiling point, enthalpy of vaporization, molar refractivity, and polarizability—for 16 CAD drugs like atorvastatin and clopidogrel [30].

- Methodology: The researchers employed eccentricity-based topological indices (e.g., the eccentric Albertson index) as molecular descriptors. They then investigated four different types of regression models: linear, quadratic, logarithmic, and cubic.

- Findings: The study concluded that nonlinear models, particularly cubic regression, were optimal for predicting most properties like enthalpy of vaporization and polarizability. The eccentric Albertson and eccentric geometric arithmetic indices demonstrated superior predictive performance. The robustness of the models was confirmed by successfully predicting the properties of five additional CAD drugs not included in the initial dataset [30].

This case highlights how the choice of descriptor and model algorithm is context-dependent, with nonlinear models often providing a better fit for complex structure-property relationships.

AI-Integrated QSAR and Emerging Trends

The field is being transformed by artificial intelligence (AI). Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that operate directly on molecular graphs, can automatically learn complex patterns from large chemical datasets without relying solely on pre-defined descriptors [31]. Furthermore, AI enables the integration of QSAR with other computational techniques like molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, providing a more holistic view of drug-target interactions [31]. These approaches are also being applied to predict ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties early in the discovery process, de-risking the development of drug candidates [31].

Successful QSAR/QSPR modeling relies on a suite of software tools and databases for descriptor calculation, model building, and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR/QSPR Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor [32] | Software | Molecular Descriptor Calculation | Open-source, calculates 1D, 2D, and fingerprints [32] |

| DRAGON [32] | Software | Molecular Descriptor Calculation | Commercial software, wide range of >5000 descriptors |

| OPERA [35] | Software / Model | QSAR Prediction Platform | Open-source, provides OECD-compliant models for physicochemical properties & environmental fate [35] |

| QSARINS [29] | Software | Model Development & Validation | Software for MLR-based model development with robust validation tools |

| scikit-learn [31] | Python Library | Machine Learning Modeling | Open-source library for implementing ML algorithms (SVM, RF, etc.) |

| PHYSPROP Database [35] | Database | Experimental Property Data | Curated database of physicochemical properties used for training models |

QSAR and QSPR modeling have evolved from simple linear regression techniques into sophisticated, AI-powered in silico powerhouses that are fundamental to modern drug discovery. By establishing quantitative relationships between molecular structures and their properties or activities, these models provide a rational framework for designing safer and more effective therapeutics, thereby reducing the high costs and long timelines associated with traditional drug development. As the field advances with the integration of more complex AI algorithms, larger datasets, and enhanced interpretability tools, the predictive accuracy and scope of QSAR/QSPR applications will continue to expand. This progression promises to further solidify their role as indispensable assets in the quest to address unmet medical needs through rational, data-driven drug design.

Within the paradigm of modern drug design, the prediction and optimization of physicochemical properties are critical for developing compounds with desired stability, bioavailability, and therapeutic activity. Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling serves as a cornerstone technique, establishing mathematical correlations between a molecule's structure and its properties, thereby accelerating discovery by reducing reliance on protracted laboratory experiments [36]. This whitepaper examines the integral role of graph-based topological indices as molecular descriptors within QSPR frameworks, highlighting their efficacy in modeling key properties such as boiling point, molar refraction, and polarizability for diverse therapeutic classes, including antibiotics, anticancer agents, and drugs for neurological and eye disorders [36] [37] [38].

A topological index (TI) is a numerical descriptor derived from the molecular graph, where atoms are represented as vertices and bonds as edges. By encoding essential structural information such as branching, connectivity, and molecular size, these graph invariants provide a robust, computationally efficient means of characterizing molecular topology independent of spatial coordinates [39] [40]. Their calculation does not require 3D coordinate generation or intensive conformational analysis, making them particularly suitable for the high-throughput screening of large chemical libraries in early-stage drug discovery and optimization [36] [39].

Fundamental Concepts and Classifications

Molecular Graph Representation

In chemical graph theory, a molecule is abstracted into a mathematical graph ( G(V, E) ), where:

- ( V(G) ) represents the set of vertices corresponding to non-hydrogen atoms [37].

- ( E(G) ) represents the set of edges corresponding to covalent bonds between these atoms [37]. The degree of a vertex ( d(u) ), is the number of edges incident to it, typically representing the atom's valence in hydrogen-suppressed graphs [36] [41].

Categorization of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be broadly classified based on the structural information they utilize [39] [40]:

- 0D Descriptors: Simple counts of atom types or molecular weight.

- 1D Descriptors: Counts of functional groups or hydrogen bond donors/acceptors.

- 2D (Topological) Descriptors: Derived from the molecular graph's connectivity, using graph theory. Topological indices fall into this category.

- 3D (Topographical) Descriptors: Based on the three-dimensional geometry of the molecule.

Topological descriptors offer a balance between computational efficiency and informational content, capturing the connectedness of atoms without the need for 3D conformation generation [39].

Key Degree-Based Topological Indices

Degree-based topological indices are among the most widely used in QSPR studies due to their strong correlation with various physicochemical properties. The table below summarizes several key indices.

Table 1: Key Degree-Based Topological Indices and Their Formulations

| Topological Index | Mathematical Formulation | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| First Zagreb Index [37] | ( M1(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} (du + dv) ) | Measures the sum of degrees of adjacent vertices, related to molecular branching. |

| Second Zagreb Index [37] | ( M2(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} (du \cdot dv) ) | Captures the product of degrees of adjacent vertices. |

| Atom-Bond Connectivity (ABC) Index [37] [42] | ( ABC(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} \sqrt{\frac{du + dv - 2}{du d_v}} ) | Models the energy of π-electrons and thermodynamic properties. |

| Randic Index [38] [41] | ( \chi(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} \frac{1}{\sqrt{du d_v}} ) | Characterizes molecular branching and connectivity; the original connectivity index. |

| Hyper Zagreb Index [37] | ( HM(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} (du + d_v)^2 ) | An extension of the Zagreb indices, sensitive to vertex degrees. |

| Geometric-Arithmetic (GA) Index [42] | ( GA(G) = \sum{uv \in E(G)} \frac{2\sqrt{du dv}}{du + d_v} ) | Relates to the stability and reactivity of molecular structures. |

Computational Methodologies and Workflows