Natural vs. Synthetic Compounds: A Data-Driven Analysis of Predictive Accuracy in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the predictive accuracy of computational models for natural versus synthetic compounds.

Natural vs. Synthetic Compounds: A Data-Driven Analysis of Predictive Accuracy in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the predictive accuracy of computational models for natural versus synthetic compounds. It explores the foundational chemical and structural differences that influence model performance, examines cutting-edge AI and machine learning methodologies, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes rigorous validation and benchmarking frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this review offers practical insights for selecting appropriate models, improving prediction reliability, and accelerating the integration of complex natural products into the drug discovery pipeline.

Defining the Divide: Structural Complexity and Data Landscapes of Natural and Synthetic Compounds

The pursuit of new bioactive molecules, particularly for drug discovery, relies on two primary reservoirs: natural products (NPs), evolved in biological systems, and synthetic compounds (SCs), designed and produced in the laboratory. These two classes of compounds are not merely derived from different sources; they inhabit distinct regions of chemical space, characterized by fundamental differences in their molecular architectures. For researchers, particularly in drug development, understanding these inherent disparities is crucial for selecting compound libraries for screening, predicting biological activity, and optimizing lead compounds. The structural variations between NPs and SCs directly influence their performance in predictive computational models, their interactions with biological targets, and their overall suitability as drug candidates. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these chemical and structural differences, framing the analysis within the context of predictive accuracy for research involving natural versus synthetic compounds.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Molecular Descriptors

Extensive cheminformatic analyses of large compound databases have consistently revealed significant, quantifiable differences between NPs and SCs. The tables below summarize these key physicochemical properties and structural features, providing a clear, side-by-side comparison essential for researchers.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Physicochemical Properties

| Molecular Descriptor | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Higher (Average: ~500-750+ Da) [1] [2] | Lower (Average: ~350-500 Da) [1] [2] | NPs often exceed Rule of 5 limits, impacting oral bioavailability predictions [3]. |

| Fraction of sp3 Carbons (Fsp3) | Higher (More 3D complexity) [1] [4] | Lower (More planar structures) [1] | Higher Fsp3 in NPs correlates with better clinical success rates and reduced patent attrition [1]. |

| Chirality & Stereocenters | Greater number of stereogenic centers [4] | Fewer stereogenic centers [3] | Increased stereochemical complexity demands more sophisticated analytical and predictive methods. |

| Number of Aromatic Rings | Fewer [2] [4] | More [2] | SCs' aromaticity favors flat, 2D architectures; NPs' aliphatic rings contribute to 3D shape [2]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Functional Groups and Structural Features

| Structural Feature | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen-Bearing Functional Groups | More abundant (e.g., alcohols, carbonyls) [2] [5] | Less abundant [2] | NPs are more oxophilic, influencing solubility, hydrogen bonding, and target interactions [3]. |

| Nitrogen-Bearing Functional Groups | Less common, except in specific classes (e.g., peptides) [2] | More common and diverse [2] [5] | Reflects the synthetic chemist's reliance on nitrogen-containing building blocks (e.g., amines, heterocycles). |

| Halogens & Sulfur | Relatively rare [2] | More frequently incorporated [2] | Halogens are common in SCs for modulating electronic properties and metabolic stability. |

| Macrocyclic Structures | More prevalent and structurally diverse [1] | Less common [1] | Macrocycles in NPs access unique, underpopulated chemical space and can target challenging protein interfaces [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Structural Analysis

To objectively compare NPs and SCs, researchers employ standardized computational and analytical protocols. The following methodology details a typical cheminformatic workflow for quantifying these structural differences.

Cheminformatic Analysis of Compound Libraries

Objective: To quantitatively compare the structural and physicochemical properties of pre-defined sets of natural products and synthetic compounds.

Materials:

- Compound Datasets: Curated structural libraries, such as the Dictionary of Natural Products for NPs and commercial databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) for SCs [2].

- Software: Cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL Descriptor) for calculating molecular properties [5].

- Computing Environment: Standard computer workstation with sufficient RAM for processing large datasets.

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Compile and clean structural files (e.g., SDF, SMILES) for NPs and SCs. Remove duplicates and salts to ensure a representative dataset [2].

- Descriptor Calculation: For every molecule in both datasets, compute a standard set of molecular descriptors. These typically include [1] [2] [5]:

- Molecular weight (MW)

- Number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA)

- Calculated octanol/water partition coefficient (ALOGPs)

- Topological polar surface area (tPSA)

- Number of rotatable bonds (Rot)

- Fraction of sp3 carbons (Fsp3)

- Counts of aromatic and aliphatic rings

- Counts of specific functional groups

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the average, median, and distribution for each descriptor across the NP and SC datasets.

- Chemical Space Visualization: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the calculated descriptors to project the molecules into a 2D or 3D chemical space map. This visually illustrates the overlap and separation between NP and SC chemical spaces [2].

Interpretation: Consistent and statistically significant differences in the average values and distributions of the calculated descriptors (as summarized in Tables 1 and 2) confirm inherent structural disparities. The PCA plot will typically show that NPs occupy a broader and often distinct region of chemical space compared to the more clustered SCs [2].

Machine Learning for Classification

Objective: To develop a predictive model that distinguishes NPs from SCs based on their molecular descriptors, thereby identifying the most discriminating features.

Materials: The same curated datasets and computed descriptors from Protocol 3.1.

Procedure:

- Feature Selection: Use the computed molecular descriptors as features for a machine learning model.

- Model Training: Employ supervised learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) trained on a labeled dataset (NP vs. SC) [5].

- Model Validation: Assess model performance using cross-validation and a held-out test set. High accuracy (e.g., ~89% as achieved by Random Forest [5]) confirms that the structural differences are quantifiable and predictable.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Extract the molecular descriptors that contribute most to the model's classification decision. These are the key inherent differences between the two classes [5].

Interpretation: This protocol not only validates the existence of inherent differences but also ranks their relative importance for classification, providing a data-driven list of the most critical distinguishing features.

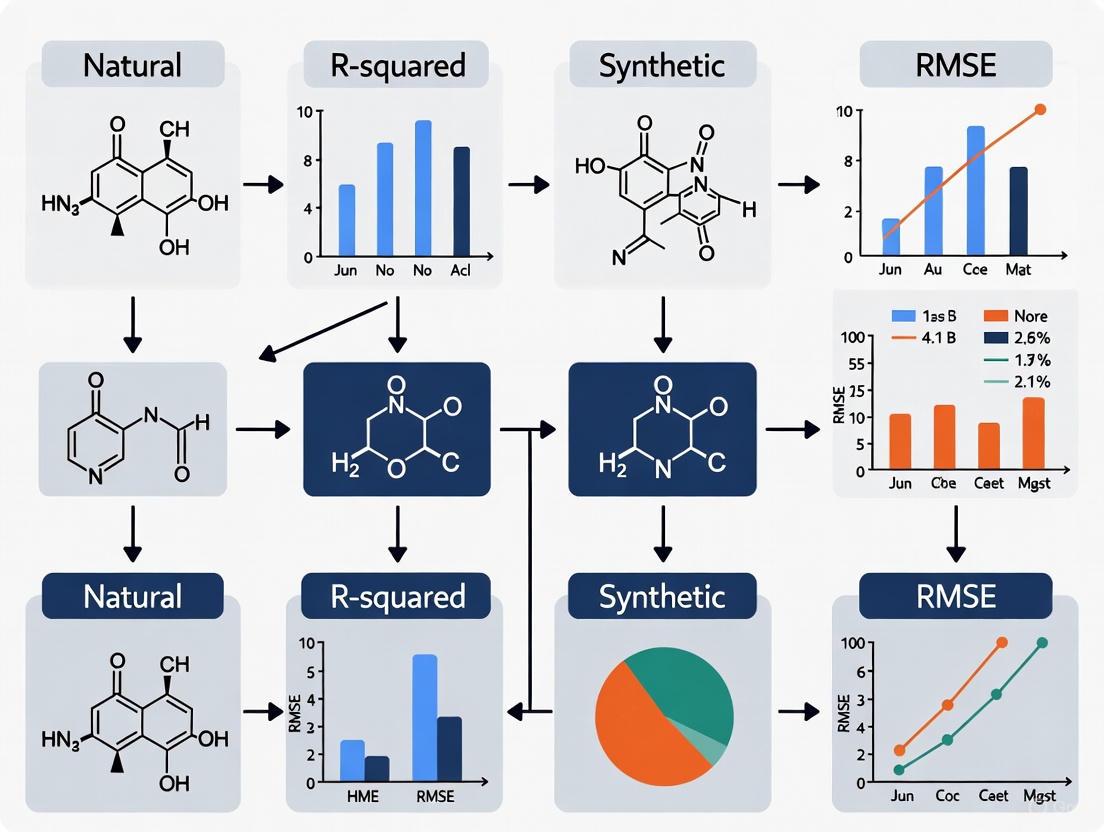

Visualization of Research Workflows and Chemical Space

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow and the conceptual relationship between different chemical spaces, aiding in the understanding of the research processes and their outcomes.

Table 3: Key Resources for Structural Comparison Studies

| Resource/Solution | Function | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Compound Databases | Provide canonical structural data for NPs and SCs to ensure analysis reproducibility. | Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP), COCONUT, ChEMBL, ZINC [2] [4] |

| Cheminformatics Software | Calculate molecular descriptors and generate chemical fingerprints for similarity analysis and modeling. | RDKit, PaDEL Descriptor, Open Babel [5] [4] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Implement classification algorithms to distinguish NPs from SCs and identify key molecular descriptors. | Scikit-learn, R [5] |

| Statistical & Visualization Software | Perform statistical tests and create plots (PCA, distribution histograms) to interpret and present results. | R, Python (Matplotlib, Seaborn) [2] |

In the data-driven landscape of modern drug discovery, the selection of chemical databases fundamentally shapes the outcome of research, particularly in the specialized field of natural product exploration. Databases such as COCONUT (Collection of Open Natural Products), ZINC, and various commercial libraries each offer distinct chemical spaces and data characteristics. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers aiming to compare predictive accuracy between natural and synthetic compounds. Natural products exhibit significant structural divergence from synthetic molecules, featuring higher scaffold diversity, more chiral centers, and distinct physicochemical properties that challenge conventional cheminformatic methods [6]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these essential resources, focusing on their structural coverage, fragment diversity, and implications for predictive model performance in natural product research.

Core Characteristics and Structural Diversity

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of COCONUT, ZINC, and representative commercial libraries, highlighting their distinct roles in chemical research.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Chemical Databases

| Characteristic | COCONUT | ZINC | Commercial Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Natural Products (NPs) & NP-like molecules [7] | Commercially available screening compounds [7] [6] | Synthetically accessible drug-like compounds [7] |

| Total Compounds | 401,624 [7] | ~885 million [7] | Billions to hundreds of billions (e.g., REAL database) [7] |

| Structural Emphasis | Higher scaffold diversity, more fused rings, more chiral centers [6] | Classical drug-like space, built from known building blocks [7] | Explores vast regions of synthesizable chemical space [7] |

| Key Applications | NP research, bioactivity prediction, understanding NP chemical space [7] [6] | Ligand-based virtual screening, initial hit identification [6] | High-throughput screening, finding novel hits for diverse targets [7] |

Quantitative Fragment Analysis and Bioactive Enrichment

A deeper understanding of database characteristics can be gleaned from analyzing their molecular fragments. Deconstructing molecules into Ring Fragments (RFs) and Acyclic Fragments (AFs) reveals differences in diversity and bioactive potential.

Table 2: Fragment Analysis and Bioactive Enrichment Potential

| Metric | COCONUT | ZINC | PubChem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Ring Fragments (RFs) | 115,381 [7] | 2.8 million [7] | 9.0 million [7] |

| Total Acyclic Fragments (AFs) | 45,816 [7] | 2.8 million [7] | 5.5 million [7] |

| Exclusive RFs (≤ 13 atoms) | 1,863 (1.6% of its total RFs) [7] | 17,578 (0.6% of its total RFs) [7] | 1,333,179 (14.8% of its total RFs) [7] |

| Exclusive AFs (≤ 13 atoms) | 2,131 (4.7% of its total AFs) [7] | 145,340 (5.3% of its total AFs) [7] | 1,805,294 (33.0% of its total AFs) [7] |

| Bioactive Fragment Source | Contains many RFs and AFs enriched in bioactive compounds from ChEMBL [7] | Serves as a source of synthetic decoys for NP identification models [6] | Provides a broad landscape of published molecules and their fragments [7] |

Analysis shows that while public databases and natural product collections contain mostly fragments up to 13 atoms, COCONUT has a significant proportion of molecules with larger, more complex fragments [7]. A key finding is that many fragments found in COCONUT are enriched in bioactive compounds compared to inactive molecules in ChEMBL, highlighting the inherent bioactivity-prone nature of natural product scaffolds [7]. Furthermore, COCONUT contains thousands of exclusive fragments not found in the other major databases, representing unique structural motifs for drug discovery [7].

Experimental Protocols for Database Evaluation and Application

Protocol 1: Evaluating Fingerprint Performance for Natural Product Identification

Objective: To assess the performance of different molecular fingerprints in distinguishing natural products from synthetic compounds and in identifying bioactive natural products [6].

Methodology:

Dataset Curation:

- Natural Products: Use a curated subset of the COCONUT database. Remove duplicates, invalid structures, and calculate Natural Product Likeness (NPL) scores [6].

- Synthetic Decoys: From the ZINC "in-stock" library, identify molecules similar to each NP (Tanimoto similarity ≥ 0.5 using ECFP4) but with an NPL score below zero. This ensures structural similarity while maximizing "synthetic" character [6].

- External Validation: Use separate datasets for tasks like "NP Identification" (NP vs. synthetic) and "Target Identification" (active vs. inactive NPs) from resources like NPASS [6].

Model Training:

- Train neural networks (e.g., multi-layer perceptrons or autoencoders) on the curated dataset to classify compounds as natural or synthetic.

- Extract neural fingerprints from the activations of the hidden layers of the trained network [6].

Performance Comparison:

- Compare the neural fingerprints against traditional fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS) and NP-specific fingerprints.

- Evaluation metrics include the ability to retrieve NPs from a synthetic background and to distinguish active from inactive NPs in virtual screening tasks [6].

Protocol 2: Fragment-Based Analysis of Chemical Space and Novelty

Objective: To quantify the diversity and novelty of fragments in different databases and identify novel, bioactive-like fragments for synthesis [7].

Methodology:

Fragment Deconstruction:

- Process all molecules from COCONUT, ZINC, PubChem, and generated databases (e.g., GDB-13s).

- Deconstruct each molecule into a Ring Fragment (RF) (ring atoms plus ring-adjacent atoms) and an Acyclic Fragment (AF) (only acyclic atoms) [7].

Frequency and Uniqueness Analysis:

- Count the occurrence of each unique RF and AF across the databases.

- Identify "exclusive fragments" present in only one database and "singleton fragments" that appear only once [7].

Bioactive Enrichment and Novelty Search:

- Identify RFs and AFs that are statistically enriched in bioactive compounds from ChEMBL.

- Search for structural analogues of these enriched, bioactive fragments within the fragments derived from the generated database (GDB-13s). These represent novel, synthetically accessible scaffolds with high potential for bioactivity [7].

The workflow below illustrates the process of using neural networks to generate specialized fingerprints for natural product research.

Diagram 1: Neural Fingerprint Workflow for NPs.

Table 3: Key Resources for Natural Product and Cheminformatics Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Database Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT [7] [6] | Database | Public repository of natural products and NP-like molecules. | Provides the definitive source of NP structures for training models, defining NP chemical space, and benchmarking. |

| ZINC [7] [6] | Database | Public repository of commercially available "drug-like" and screening compounds. | Serves as the primary source of synthetic molecules for creating decoy sets and comparative analysis against NPs. |

| ChEMBL [7] | Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Provides bioactivity data essential for identifying fragments and scaffolds enriched in bioactive compounds. |

| GDB (Generated Databases) [7] | Database | Enumerates all possible organic molecules up to a given atom count under stability rules. | A source of unprecedented molecular frameworks and novel fragments for fragment-based drug discovery. |

| RDKit [6] | Software | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for parsing molecules (SMILES), calculating descriptors, generating fingerprints, and fragmenting molecules. |

| FPSim2 [6] | Software | Library for chemical fingerprint similarity searches. | Enables high-performance similarity searches in large chemical databases (e.g., for decoy selection in Protocol 1). |

| Neural Fingerprints [6] | Method | Molecular representation derived from trained neural networks. | Creates NP-optimized molecular representations that can outperform traditional fingerprints in NP-related tasks. |

| NPL Score [6] | Metric | Quantitative estimate of a molecule's similarity to known natural products. | Used to filter and curate datasets, ensuring the "natural" or "synthetic" character of molecules in training sets. |

The comparative analysis of COCONUT, ZINC, and commercial libraries reveals a trade-off between unique bioactive diversity and vast synthetic accessibility. COCONUT provides a highly curated, bioactivity-enriched space of natural product scaffolds, offering thousands of exclusive fragments with high potential for drug discovery [7] [6]. In contrast, ZINC and commercial libraries offer unparalleled volume and synthetic tractability but are built from a more limited set of classical building blocks [7]. For research focused on predicting bioactivity, especially for natural products, the choice of database and associated tools is paramount. Employing NP-specific resources like COCONUT and advanced representations like neural fingerprints is critical for achieving high predictive accuracy, as traditional methods developed for synthetic compounds often underperform in the distinct and complex chemical space of natural products [6]. The future of effective natural product research lies in the continued development of specialized databases, algorithms, and experimental protocols that acknowledge and leverage these fundamental differences.

The accurate prediction of key molecular properties is fundamental to the success of modern drug discovery and development. Among these properties, frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO-LUMO gaps), polarizability, and three-dimensional (3D) conformational characteristics significantly influence a compound's biological activity, metabolic stability, and safety profile. The computational prediction of these properties for both natural and synthetic compounds presents distinct challenges and opportunities. Natural products often possess complex, three-dimensional architectures with diverse pharmacophores, while synthetic compounds frequently exhibit more planar geometries due to constraints in synthetic accessibility and traditional chemical feedstocks. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of predictive methodologies for these essential molecular properties, evaluating their accuracy, applicability, and limitations within the context of drug discovery research.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Methodologies

Predictive Accuracy for HOMO-LUMO Gaps

The HOMO-LUMO gap, representing the energy difference between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals, is a critical determinant of chemical reactivity, optical properties, and biological activity. Accurate prediction of this property is essential for designing organic electronic materials and bioactive compounds.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for HOMO-LUMO Gap Prediction

| Methodology | Theoretical Basis | Reported Accuracy | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ωB97XD/6-311++G(d,p) | Density Functional Theory | Closest to CCSD(T) reference [8] | High | Highest accuracy requirements for tellurophene-based helicenes |

| B3LYP/ωB97XD (Composite) | DFT (geometry optimization with B3LYP, single-point with ωB97XD) | Similar accuracy to full ωB97XD [8] | Moderate | Cost-effective screening of larger molecular systems |

| Machine Learning (XGBT) with KR FPs | Extreme Gradient Boosting with Klekota-Roth Fingerprints | R² = 0.84 for LUMO levels vs experimental data [9] | Low | High-throughput screening of organic semiconductor materials |

| CAM-B3LYP | Long-range corrected DFT functional | Good for excited states [8] | Moderate | Charge-transfer systems and excited state properties |

| B3LYP-D3 | Empirical dispersion-corrected DFT | Moderate improvement over B3LYP [8] | Moderate | Systems where dispersion forces are significant |

The benchmarking studies reveal that the ωB97XD functional provides the most accurate HOMO-LUMO gap predictions when compared to the gold-standard CCSD(T) method, particularly for tellurophene-based helicenes [8]. However, for large-scale virtual screening, machine learning approaches using the XGBT algorithm with Klekota-Roth fingerprints achieve remarkable accuracy (R² = 0.84 for LUMO levels) while dramatically reducing computational costs [9]. This transfer learning approach, which fine-tunes models initially trained on DFT data with experimental values, demonstrates particular value for predicting LUMO energy levels where DFT calculations can be unstable.

Assessment of 3D Conformational Prediction

The three-dimensional shape of drug molecules profoundly influences their biological interactions and efficacy. Various metrics have been developed to quantify molecular three-dimensionality, each with distinct strengths and limitations for comparing natural and synthetic compounds.

Table 2: Comparison of 3D Molecular Descriptors

| Descriptor | Definition | Range | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized Principal Moment of Inertia (PMI) | Ratio of molecular moments of inertia (I₁/I₃ and I₂/I₃) | 0-1 (linear to spherical) | Size-independent comparison [10] | Requires energy-minimized 3D structures |

| Fraction of sp³ Hybridized Carbons (Fsp³) | Count of sp³ carbons / total carbon count | 0-1 | Simple calculation | Does not fully capture molecular shape [11] |

| Plane of Best Fit (PBF) | RMSD of atoms from best-fit plane | 0-∞ Å | Intuitive geometric interpretation | Correlated with size; less resolution than PMI [11] |

| WHALES Descriptors | Holistic representation incorporating pharmacophore and shape patterns | Variable | Captures charge, atom distributions, and shape simultaneously [12] | Computationally intensive |

| 3D Score | Sum of normalized PMI values (I₁/I₃ + I₂/I₃) | >1.6 considered "highly 3D" | Single metric for quick classification [10] | Oversimplifies complex shape characteristics |

Analysis of molecular databases reveals striking differences in three-dimensionality between natural products and synthetic compounds. PMI analysis of DrugBank structures shows that approximately 80% of approved and experimental drugs have 3D scores below 1.2, indicating predominantly linear and planar topologies, with only 0.5% classified as "highly 3D" (score >1.6) [10]. This trend persists in protein-bound conformations from the Protein Data Bank, suggesting that the limited three-dimensionality is not merely a consequence of crystallization conditions but reflects inherent constraints in drug discovery pipelines [10].

The WHALES (Weighted Holistic Atom Localization and Entity Shape) descriptors represent a significant advancement for scaffold hopping from natural products to synthetic mimetics, simultaneously capturing geometric interatomic distances, molecular shape, and partial charge distribution [12]. This approach has demonstrated practical utility, successfully identifying novel synthetic cannabinoid receptor modulators with 35% experimental confirmation rate using natural cannabinoids as structural queries [12].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Molecular Property Prediction and 3D Conformational Analysis. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational approaches for predicting key molecular properties from different molecular representations.

Polarizability and Hyperpolarizability Calculations

Polarizability and hyperpolarizability are essential electronic properties that influence intermolecular interactions, spectroscopic behavior, and non-linear optical applications. Computational methods for predicting these properties range from quantum mechanical calculations to machine learning approaches.

Table 3: Methods for Calculating Polarizability and Hyperpolarizability

| Method | Level of Theory | Properties Calculated | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF/6-311++G(d,p) | Ab initio Hartree-Fock | Dipole moments, polarizabilities, first-order hyperpolarizabilities [13] | Benchmark studies of quinoxaline derivatives |

| DFT/B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | Density Functional Theory | Dipole moments, polarizabilities, first-order hyperpolarizabilities [13] | Cost-effective property prediction for drug-like molecules |

| ImageMol Pretraining | Deep Learning on Molecular Images | Multiple molecular properties from pixel-level features [14] | High-throughput prediction of drug metabolism and toxicity |

| Bayesian Active Learning | Transformer-based BERT with uncertainty estimation | Toxicity properties with reliable confidence intervals [15] | Data-efficient drug safety assessment |

For quinoxaline-1,4-dioxide derivatives, both HF/6-311++G(d,p) and DFT/B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) methods have been employed to calculate dipole moments, polarizabilities, and first-order hyperpolarizabilities, alongside frontier molecular orbital analysis [13]. The ImageMol framework represents an alternative approach, utilizing unsupervised pretraining on 10 million drug-like molecular images to predict various molecular properties, including electronic characteristics, from pixel-level structural features [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking HOMO-LUMO Gap Calculations

The accurate prediction of HOMO-LUMO gaps requires careful methodological selection and validation. The following protocol outlines a robust approach for benchmarking computational methods:

Molecular System Preparation: Begin with geometry optimization of the target molecules using a moderate-level DFT functional such as B3LYP with appropriate basis sets (e.g., 6-311++G(d,p) for light atoms, LANL2DZ for heavy elements like tellurium) [8].

Method Selection: Employ a diverse set of DFT functionals spanning different theoretical approximations, including:

- Global hybrids (B3LYP, PBE0)

- Meta-GGAs (M06, MN15)

- Long-range corrected functionals (CAM-B3LYP, ωB97XD, LC-BLYP)

- Double hybrids (B2PLYP) [8]

Reference Standards: Compare DFT-predicted HOMO-LUMO gaps against high-level wavefunction theory methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) where feasible, or against experimental values when available [8] [9].

Statistical Analysis: Perform comprehensive error analysis using metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and correlation coefficients (R²) to identify the most accurate functional for the specific chemical system under investigation [8].

Machine Learning Enhancement: For high-throughput screening, implement transfer learning approaches where models pretrained on large DFT datasets (e.g., 11,626 DFT calculations from the Harvard Energy database) are fine-tuned with smaller experimental datasets (e.g., 1,198 experimental measurements) to improve predictive accuracy for LUMO energy levels where DFT shows instability [9].

Quantifying Molecular Three-Dimensionality

The assessment of molecular 3D conformation involves multiple complementary approaches:

Structure Preparation: Generate representative 3D conformers using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94) or quantum chemical methods, ensuring adequate sampling of the conformational space [12].

PMI Analysis:

- Calculate the principal moments of inertia (I₁ ≤ I₂ ≤ I₃) for each energy-minimized structure

- Compute normalized PMI ratios (I₁/I₃ and I₂/I₃)

- Plot molecules on a normalized PMI triangle with reference points: [0,1] for linear molecules (e.g., dimethylbutadiyne), [0.5,0.5] for planar molecules (e.g., benzene), and [1,1] for spherical molecules (e.g., adamantane) [10]

WHALES Descriptor Calculation:

- For each non-hydrogen atom, compute an atom-centered weighted covariance matrix using partial charges as weights

- Calculate atom-centered Mahalanobis distances to normalize interatomic distances based on local feature distributions

- Derive atomic indices (remoteness, isolation degree, and their ratio) that capture local and global molecular shape characteristics

- Apply binning procedures to obtain fixed-length descriptors (33 values total) enabling comparison across diverse molecular sizes [12]

Database Analysis: Apply these metrics to large molecular databases (e.g., DrugBank, ChEMBL, ZINC) to establish baseline distributions and identify outliers with unusual three-dimensional characteristics [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Property Prediction

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS | DFT and wavefunction calculations | HOMO-LUMO gap prediction, polarizability calculations [13] [8] |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | RDKit, KNIME, MOE | Molecular fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation | KR fingerprint generation, PMI analysis [9] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | ImageMol, MolBERT, Graph Neural Networks | Molecular property prediction from structures or images | High-throughput toxicity prediction, molecular representation learning [14] [15] |

| Molecular Databases | DrugBank, PDB, ChEMBL, ZINC, Harvard Energy Database | Source of molecular structures and experimental properties | Training data for machine learning models, benchmarking [10] [9] |

| Shape Analysis Tools | Custom scripts for PMI/PBF, WHALES descriptor implementation | 3D molecular shape quantification | Scaffold hopping from natural products, 3D diversity analysis [11] [12] |

The comparative analysis of predictive methodologies for key molecular properties reveals significant advances in computational accuracy while highlighting persistent challenges. For HOMO-LUMO gap prediction, range-separated functionals like ωB97XD provide superior accuracy for complex systems, while machine learning approaches enable high-throughput screening with surprisingly high correlation to experimental values (R² = 0.84 for LUMO levels) [8] [9]. The assessment of three-dimensionality demonstrates that most approved drugs occupy limited conformational space, with fewer than 1% classified as "highly 3D" by PMI metrics [10]. This finding has profound implications for drug discovery, suggesting significant unexplored potential in underutilized regions of chemical space.

The integration of holistic molecular representations like WHALES descriptors enables effective scaffold hopping from natural products to synthetically accessible mimetics, successfully bridging the structural complexity divide between natural and synthetic compounds [12]. For polarizability and related electronic properties, combined computational approaches leveraging both quantum mechanical calculations and deep learning frameworks like ImageMol provide complementary strategies for comprehensive molecular characterization [14] [13].

As drug discovery increasingly targets complex biological systems and difficult-to-drug proteins, the accurate prediction and strategic optimization of these fundamental molecular properties will be crucial for expanding the therapeutic landscape. The methodologies compared in this guide provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for navigating this challenging but promising frontier.

The Data Scarcity Challenge for Natural Products

Natural products (NPs) are indispensable to drug discovery, with approximately 60% of medicines approved in the last 30 years deriving from NPs or their semisynthetic derivatives [16]. However, the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to NP research faces a fundamental obstacle: data scarcity. This challenge stems from intrinsic structural differences between NPs and synthetic compounds (SCs) that create a disparity in data availability and machine learning model performance.

Time-dependent chemoinformatic analyses reveal that NPs have evolved to become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness. In contrast, SCs exhibit continuous shifts in physicochemical properties constrained within a defined range governed by drug-like rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [2]. These structural differences are quantified in Table 1.

Table 1: Structural and Data Property Comparison Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Property Category | Specific Metric | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties | Mean Molecular Weight | Higher and increasing over time [2] | Lower and constrained by drug-like rules [2] |

| Ring Systems | More rings, larger fused rings, more non-aromatic rings [2] | Fewer rings but more ring assemblies, predominantly aromatic rings [2] | |

| Structural Complexity | Higher complexity, more stereocenters [2] [17] | Lower complexity, more synthetically accessible [2] | |

| Data Landscape | Bioactivity Data Availability | Limited and scattered [16] [18] | Extensive and well-organized [16] |

| Standardization | Unstandardized, multimodal, fragmented [18] | Fairly standardized, often non-relational [18] | |

| Data Repositories | Numerous, disconnected resources [16] [18] | Consolidated databases (e.g., ChEMBL) [16] |

Root Causes: Structural Complexity and Data Fragmentation

Fundamental Structural Differences

The structural divergence between NPs and SCs is not merely quantitative but qualitative in nature. NPs contain more oxygen atoms, ethylene-derived groups, and unsaturated systems, while SCs are richer in nitrogen atoms and halogens [2]. The ring systems of NPs are notably larger, more diverse, and more complex than those of SCs [2]. These structural characteristics directly impact the availability of bioactivity data, as the synthesis and testing of complex NPs remain labor-intensive, exemplified by the 30-year development timeline of Taxol from the Pacific yew tree [17].

The Data Ecosystem Challenge

The NP data landscape is characterized by high fragmentation across numerous datasets with varying levels of annotation, features, and metadata [18]. This fragmentation creates significant obstacles for AI applications:

- Multimodal Data Challenges: NP research generates diverse data types (genomic, proteomic, metabolomic, spectroscopic) that illuminate the same biochemical entities from different perspectives but are rarely integrated [18].

- Annotation Disparities: Many NPs lack comprehensive bioactivity annotations, with databases containing structures but limited target interaction profiles [16].

- Unbalanced Representation: Structural classes and bioactivity types are unevenly represented across NP datasets, creating inherent biases in predictive modeling [18].

Experimental Approaches to Overcome Data Scarcity

Similarity-Based Target Prediction with CTAPred

CTAPred (Compound-Target Activity Prediction) represents an experimental approach specifically designed to address NP data scarcity through similarity-based target prediction [16]. This methodology operates on the premise that similar molecules tend to bind similar protein targets, leveraging limited bioactivity data more efficiently.

Table 2: CTAPred Experimental Protocol and Performance

| Protocol Component | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Dataset | Compound-Target Activity (CTA) dataset from ChEMBL, COCONUT, NPASS, and CMAUP [16] | Focuses on proteins relevant to natural products compared to broader databases |

| Similarity Assessment | Fingerprinting and similarity-based search [16] | Identifies structurally similar compounds with known targets |

| Optimal Hit Selection | Top 3 most similar reference compounds [16] | Balances target recall against false positives |

| Performance | Comparable to more complex methods despite simplicity [16] | Demonstrates viability for NP target prediction |

The core innovation of CTAPred lies in its focused reference dataset that prioritizes protein targets known or likely to interact with NP compounds, thereby increasing the relevance of predictions despite limited data [16].

Knowledge Graphs as a Unifying Framework

The Experimental Natural Products Knowledge Graph (ENPKG) represents an emerging paradigm that addresses data fragmentation by converting unpublished and unstructured data into connected, machine-readable formats [18]. This approach enables causal inference rather than mere prediction by establishing relationships between different data modalities.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for constructing and utilizing a natural product knowledge graph:

Natural Product Knowledge Graph Workflow

This framework connects disparate data types through explicitly defined relationships, enabling AI models to reason across data modalities much like human experts [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Natural Product Data Science

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Data Scarcity Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAPred | Software Tool | Similarity-based target prediction [16] | Leverages limited bioactivity data through focused reference sets |

| COCONUT | Database | Open repository of elucidated and predicted NPs [16] | Provides structural data for ~400,000 natural products |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactive drug-like compounds [16] | Source of reference bioactivity data for similarity approaches |

| ENPKG | Knowledge Graph | Connects unpublished and unstructured NP data [18] | Converts fragmented data into connected, machine-readable format |

| Org-Mol | Pre-trained Model | Molecular representation learning [19] | Predicts physical properties from single molecular structures |

| Federated Learning | AI Approach | Collaborative model training without data sharing [20] [21] | Addresses data privacy concerns while expanding training data |

Comparative Predictive Accuracy in Target Identification

The performance gap between NPs and SCs in predictive modeling is particularly evident in target identification tasks. While SCs benefit from extensive bioactivity annotations in databases like ChEMBL, NPs face the challenge of limited target interaction profiles [16]. The similarity principle underlying many target prediction methods—that similar molecules tend to bind similar targets—becomes less reliable for NPs due to their structural uniqueness and the sparse coverage of NP-like structures in reference databases [16].

Advanced molecular representation learning approaches like Org-Mol show promise in bridging this accuracy gap. By pre-training on 60 million semi-empirically optimized small organic molecule structures and fine-tuning with experimental data, Org-Mol achieves R² values exceeding 0.92 for various physical properties, demonstrating that sophisticated architectures can partially compensate for data scarcity [19].

Future Directions: Overcoming Data Scarcity Through Integration

The path forward for NP research lies in embracing knowledge-driven AI that combines data-driven learning with explicit domain knowledge [18]. This approach includes:

- Federated Learning: Enables collaborative model training across institutions without sharing sensitive data, addressing privacy concerns that contribute to data silos [20] [21].

- Multimodal Learning Architectures: Capable of reasoning across genomic, spectroscopic, and bioactivity data to make predictions even when certain data types are missing [18].

- Causal Inference Models: Moving beyond correlation-based prediction to understanding cause-effect relationships in NP bioactivity [18].

The structural uniqueness of NPs that currently impedes predictive accuracy may ultimately become their greatest asset. As AI models evolve to better capture NP complexity, the very properties that make NPs challenging—structural diversity, complexity, and biological relevance—position them as exceptional sources for innovative therapeutics, provided the data scarcity challenge can be overcome through integrated approaches and specialized methodologies.

Impact of Structural Motifs on Initial Model Performance

The performance of computational models in drug discovery is profoundly influenced by the structural characteristics of the chemical libraries used for their development and validation. This is particularly evident when comparing models trained on natural products (NPs) versus synthetic compounds (SCs), which possess distinct structural motifs rooted in their different origins. NPs, resulting from billions of years of evolutionary selection, often exhibit greater structural complexity and three-dimensionality, while SCs frequently reflect the synthetic accessibility of flat, aromatic structures common in combinatorial chemistry [22] [2]. This guide objectively compares how these fundamental differences in structural motifs impact the initial performance of predictive models in areas such as toxicity assessment, chemical property prediction, and biological activity profiling.

Structural Differences Between Natural and Synthetic Compounds

The divergent origins of natural products and synthetic compounds have endowed them with significantly different structural landscapes, which in turn shape the learning capabilities and performance boundaries of predictive models.

Comparative Analysis of Key Structural Motifs

Table 1: Key Structural Differences Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Structural Feature | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Complexity | Higher, more stereogenic centers [22] | Generally lower and less complex [2] |

| Predominant Ring Types | More non-aromatic, aliphatic rings [2] [23] | Dominated by aromatic rings (e.g., benzene) [2] |

| Oxygen & Nitrogen Content | Higher oxygen atom count [2] | Higher nitrogen atom count [2] |

| Fused Ring Systems | Larger, more complex fused systems (e.g., bridged, spirocyclic) [2] | Simpler, less fused ring assemblies [2] |

| Stereochemical Complexity | High density of stereocenters [22] [23] | Fewer stereogenic elements [22] |

| Scaffold Diversity | Broader, more unique scaffold types [2] | More limited, concentrated in common chemotypes [2] |

Impact of Compound Origin on Molecular Properties

The structural differences between NPs and SCs manifest in distinct physicochemical profiles. NPs are generally larger and more complex, with higher molecular weights, more rotatable bonds, and greater molecular surface areas compared to SCs [2]. Furthermore, NPs occupy a broader and more diverse chemical space, which provides a richer training ground for models but also presents challenges in generalization due to the sparsity of data for unique scaffolds [2]. SCs, by contrast, often cluster in a more defined region of chemical space governed by "drug-like" rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, which can simplify model training but potentially limit the discovery of novel mechanisms of action [22] [2].

Performance Comparison in Predictive Modeling Tasks

The structural disparities between NPs and SCs directly impact the performance of predictive models. This section compares model efficacy across key tasks, supported by experimental data.

Toxicity Prediction Models

Toxicity prediction employs two primary computational strategies, each with distinct strengths and performance characteristics when applied to different compound classes.

Table 2: Performance of Modeling Approaches in Toxicity Prediction

| Modeling Approach | Description | Representative Algorithms | Performance & Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down Approaches | Leverages existing knowledge or databases to predict toxicity based on established structure-activity relationships [24]. | SVM, QSAR, Association Rule Mining, Text Mining [24] | Better performance for synthetic compounds and well-characterized toxicity endpoints due to reliance on large, structured datasets of known toxicophores [24]. |

| Bottom-Up Approaches | Focuses on understanding underlying molecular mechanisms from first principles via simulation of interactions [24]. | Molecular Docking, PBPK models, Random Walk with Restart [24] | Potentially more robust for predicting NP toxicity, as it does not require prior similar data and can elucidate novel mechanisms [24]. |

Solubility and Physicochemical Property Prediction

Accurate prediction of solubility is a critical rate-limiting step in drug development. Recent advances in machine learning have yielded models with significantly improved performance.

- State-of-the-Art Models: The FastSolv and ChemProp models represent the current state-of-the-art. Trained on the large, compiled BigSolDB dataset, these models leverage molecular structure embeddings to predict solubility in organic solvents, considering the effect of temperature [25].

- Performance Metrics: These new models demonstrate two to three times higher accuracy compared to the previous best model (SolProp), particularly in predicting temperature-dependent solubility variations [25]. Their performance appears to be limited mainly by the quality and consistency of the experimental training data rather than model architecture [25].

- Impact of Structural Motifs: While not explicitly comparing NPs and SCs, the models' reliance on comprehensive data underscores a challenge with NPs: their structural complexity and diversity may lead to poorer predictions if they are under-represented in training datasets like BigSolDB.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

To ensure the reliability of performance comparisons, rigorous and standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the field.

Protocol for Comparative Chemoinformatic Analysis

This protocol, used in time-dependent structural analyses [2], provides a framework for objectively comparing the chemical space of NPs and SCs.

- Dataset Curation: Assemble large, representative datasets. Example: 186,210 NPs from the Dictionary of Natural Products and 186,210 SCs from 12 synthetic databases [2].

- Time-Series Grouping: Sort molecules chronologically by their CAS Registry Numbers and group them (e.g., 37 groups of 5,000 molecules each) to analyze temporal trends [2].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute a comprehensive set of physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, volume, surface area, counts of heavy atoms, bonds, rings, and aromatic rings) [2].

- Fragment and Scaffold Analysis:

- Generate Bemis-Murcko scaffolds to represent core molecular frameworks.

- Identify ring assemblies and side chains.

- Apply the Retrosynthetic Combinatorial Analysis Procedure (RECAP) to generate molecular fragments [2].

- Chemical Space Mapping: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Tree MAP (TMAP) to visualize and compare the distribution of NPs and SCs in multidimensional chemical space [2].

Protocol for Training Solubility Prediction Models

The development of high-accuracy solubility models like FastSolv involves a structured machine learning pipeline [25].

- Data Preparation: Utilize a large-scale dataset such as BigSolDB, which compiles solubility data from nearly 800 publications, encompassing about 800 molecules and over 100 solvents [25]. Randomly split the data into a training set (>40,000 data points) and a held-out test set (~1,000 solutes).

- Molecular Featurization: Represent each molecule using a numerical embedding. The FastProp model uses pre-defined "static embeddings," while ChemProp learns embeddings during training [25].

- Model Training: Train the model to learn the complex function mapping the molecular features and temperature to a solubility value.

- Validation and Testing: Evaluate model performance on the held-out test set, ensuring it generalizes well to novel solutes not seen during training. Key metrics include accuracy and the ability to predict temperature-dependent solubility changes [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key computational tools and compound libraries that are instrumental in conducting the research and analyses described in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | Natural Product Database | Provides a comprehensive source of NP structures for analysis and model training [24]. |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Natural Product Database | A standard reference used for large-scale chemoinformatic analyses of NPs [2]. |

| BigSolDB | Curated Solubility Database | A large, compiled dataset used for training and benchmarking machine learning solubility models [25]. |

| Enamine NPL Library | Fragment Library (Physical Compounds) | A library of 4,160 natural product-like fragments for experimental screening, providing biologically validated starting points [26]. |

| QSAR Toolbox | Software | Aids in toxicity prediction by applying QSAR methodologies [24]. |

| ChemProp | Machine Learning Model | A graph neural network model for molecular property prediction, used for tasks like solubility and toxicity prediction [25]. |

| FastSolv | Machine Learning Model | A high-performance, publicly available model for predicting solubility in organic solvents [25]. |

The structural motifs inherent to natural and synthetic compounds consistently exert a significant influence on the initial performance of predictive models in drug discovery. Models applied to synthetic compound libraries often benefit from the more constrained chemical space and richer, more standardized data, leading to strong performance in tasks like toxicity prediction using top-down models. In contrast, the complexity, three-dimensionality, and greater scaffold diversity of natural products present both a challenge and an opportunity. While they may be harder to model accurately with current data resources, their structural richness is a key driver for discovering novel bioactivities. The emergence of sophisticated models like FastSolv for solubility prediction, along with strategies like diversity-oriented synthesis that create NP-inspired compounds, are progressively narrowing the performance gap. Future improvements will likely depend as much on generating higher-quality, standardized biological data for complex natural scaffolds as on advances in model architectures themselves.

Computational Arsenal: AI, ML, and Workflow Strategies for Property Prediction

The accurate prediction of molecular properties is a critical challenge in pharmaceutical research, particularly when distinguishing between natural and synthetic compounds. The selection of an appropriate machine learning model can significantly influence the predictive accuracy and reliability of computational drug discovery pipelines. Among the plethora of available algorithms, Gradient Boosting, Random Forests, and Multilayer Perceptrons have emerged as particularly prominent in contemporary research. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three model classes, focusing on their performance in predicting key pharmaceutical properties such as solubility, biological activity, and toxicity. By synthesizing experimental data from recent studies and detailing essential methodological protocols, this article serves as a reference for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize their model selection for compound analysis.

The following tables consolidate quantitative performance metrics from recent studies that directly compared Gradient Boosting, Random Forests, and Multilayer Perceptrons across various pharmaceutical prediction tasks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance in Solubility and Bioactivity Prediction

| Application Domain | Best Performing Model (Accuracy/R²) | Random Forest Performance | Gradient Boosting Performance | MLP Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lacosamide Solubility in SC-CO₂ | GBDT (R² = 0.9989) | R² = 0.9943 | XGBoost: R² = 0.9986, GBDT: R² = 0.9989 | R² = 0.9975 | [27] |

| Anticancer Ligand Prediction (ACLPred) | LightGBM (Accuracy = 90.33%, AUROC = 97.31%) | Not Specified | LightGBM: Accuracy = 90.33% | Not Specified | [28] |

| Organic Compound Aqueous Solubility | Random Forest (R² = 0.88, RMSE = 0.64) | R² = 0.88, RMSE = 0.64 | Not Specified | Not Specified | [29] |

| Chemical Toxicity Prediction | Vision Transformer + MLP (Accuracy = 0.872, F1 = 0.86) | Part of traditional ML comparison | Part of traditional ML comparison | Integrated in multimodal approach | [30] |

Table 2: Broad Benchmarking on Tabular Data (111 Datasets)

| Model Type | Performance Characterization | Key Strength | Notable Finding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning (MLP) | Often equivalent or inferior to GBMs on tabular data | Excels on specific dataset types where DL outperforms alternatives | Sufficient datasets found where DL models performed best, enabling characterization | [31] |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | Frequently outperforms or matches DL on tabular data | Strong general performance on structured data | Considered among top traditional methods in comprehensive benchmark | [31] |

| Random Forest | Robust performance across diverse datasets | Handles complex, multidimensional data well | Effective for various signal types in biochemical applications | [32] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Anticancer Ligand Prediction with Tree-Based Ensembles

The ACLPred study exemplifies a rigorous protocol for developing a high-accuracy bioactivity prediction model using tree-based ensembles [28].

Dataset Curation: Researchers compiled a balanced dataset of 9,412 small molecules (4,706 active and 4,706 inactive anticancer compounds) from PubChem BioAssay. Structural similarity was assessed using the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc), excluding molecules with Tc > 0.85 to reduce bias [28].

Feature Engineering: A comprehensive set of 2,536 molecular descriptors was calculated using PaDELPy and RDKit libraries, including 1D/2D descriptors and molecular fingerprints. Multistep feature selection was applied: (1) Variance threshold (<0.05) filtered low-variance features; (2) Correlation threshold (0.85) removed highly correlated features; (3) The Boruta algorithm identified statistically significant features [28].

Model Training and Evaluation: The Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) was implemented with independent test and external validation datasets. Model interpretability was enhanced using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify descriptor importance, revealing topological features as major contributors to predictions [28].

Protocol 2: Solubility Prediction in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide

This protocol outlines the methodology for predicting drug solubility in supercritical CO₂, a crucial process for pharmaceutical micronization [27].

Experimental Data Collection: Laboratory solubility data for Lacosamide was collected across four temperature levels (308, 318, 328, and 338 K) and seven pressure levels (12-30 MPa), corresponding to CO₂ density ranges of 384.2-929.7 kg m⁻³. Each experimental point represented the mean of three replicate measurements [27].

Model Implementation: Six machine learning models were trained using temperature (T), pressure (P), and CO₂ density (ρ) as input features to predict the mole fraction of Lacosamide solubility. The dataset was split 80%/20% for training and testing, with stratified sampling based on temperature to ensure proportional representation of all conditions [27].

Performance Validation: Models were evaluated using coefficient of determination (R²), mean squared error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and standard deviation (SD). Hyperparameter optimization was performed via RandomizedSearchCV with 20 iterations and 3-fold cross-validation [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for ML-Based Pharmaceutical Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Research | Example Application | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDELPy Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Generates 1,446 1D/2D descriptors for quantitative structure-property relationships | [28] |

| RDKit Library | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Calculates 210 additional molecular descriptors for enriched feature representation | [28] |

| Boruta Algorithm | Random forest-based feature selection | Identifies statistically significant features in high-dimensional biochemical datasets | [28] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretability framework | Quantifies feature importance and provides insight into model decision processes | [28] [29] |

| SMOTETomek | Hybrid sampling technique for class imbalance | Addresses dataset imbalance in water quality management scenarios | [33] |

| SciKit-Learn Python Library | Machine learning implementation | Provides RF, GBDT, and other ML models with consistent APIs | [32] |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

ML Model Comparison Workflow

Algorithmic Differences and Strengths

The comparative analysis of Gradient Boosting, Random Forests, and Multilayer Perceptrons reveals a nuanced landscape for pharmaceutical predictions. Gradient Boosting models, particularly implementations like LightGBM and XGBoost, consistently achieve top performance in structured data tasks such as solubility and bioactivity prediction [28] [27]. Random Forest offers robust, interpretable performance with strengths in handling complex, multidimensional biochemical data [32] [29]. Multilayer Perceptrons, while sometimes outperformed on general tabular data, demonstrate exceptional capability in specific domains, particularly when integrated into multimodal architectures or when modeling complex non-linear relationships [31] [30].

The optimal model selection depends critically on specific research contexts—Gradient Boosting for maximum predictive accuracy on structured molecular data, Random Forest for robust feature interpretation and reliability, and Multilayer Perceptrons for specialized applications leveraging their pattern recognition capabilities. This comparative guidance enables researchers to make informed decisions in deploying machine learning models for natural versus synthetic compound research.

Deep Learning and Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Representation

Molecular representation learning has catalyzed a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery, transitioning from reliance on manually engineered descriptors to the automated extraction of features using deep learning. This transition enables data-driven predictions of molecular properties, inverse design of compounds, and accelerated discovery of chemical materials [34]. Effective molecular representation serves as the critical bridge between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties, forming the foundation for various drug discovery tasks, including virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping [35]. The evolution from traditional representations like Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings and molecular fingerprints to advanced graph-based representations and geometric learning models has fundamentally transformed how scientists predict and manipulate molecular properties for drug discovery and material design [34].

Within this context, the comparison between natural products (NPs) and synthetic compounds (SCs) presents a particularly insightful research domain. NPs, resulting from prolonged natural selection, have evolved to interact with various biological macromolecules, implying novel modes of action that have historically served as a wellspring for innovative drugs [2]. Statistical analyses reveal that NPs occupy a more diverse chemical space than SCs, containing more oxygen atoms, ethylene-derived groups, unsaturated systems, and higher structural complexity [2]. Understanding how deep learning models, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), perform across these structurally distinct compound classes is essential for advancing molecular property prediction in drug discovery.

Graph Neural Networks: Architectural Foundations and Evolution

Core GNN Architectures for Molecular Representation

Graph Neural Networks have emerged as transformative tools in molecular representation due to their innate ability to model molecular structures as graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [36]. This natural alignment with chemical structure enables GNNs to accurately capture both local atomic environments and global molecular topology. Among the foundational architectures, several key variants have demonstrated significant utility in molecular property prediction:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) operate by performing neighborhood aggregation, where each node updates its representation by combining features from adjacent nodes [37] [38]. This approach effectively captures local structural patterns but may struggle with long-range interactions in complex molecular systems.

Graph Attention Networks (GATs) incorporate attention mechanisms that assign learned importance weights to neighboring nodes during aggregation [37] [38]. This allows the model to focus on the most relevant structural components for property prediction, enhancing both performance and interpretability.

Relational Graph Convolutional Networks (R-GCNs) extend GCNs to handle multiple relationship types, making them particularly suitable for heterogeneous molecular graphs that incorporate diverse atomic interactions and bond types [38].

Recent research has revealed that conventional covalent-bond-based molecular graph representations have limitations, while incorporating non-covalent interactions has been shown to notably enhance performance. These findings indicate that novel graph representations that integrate geometric and topological information can outperform traditional approaches [37].

Emerging GNN Architectures and Hybrid Approaches

The rapid evolution of GNN architectures has yielded several innovative frameworks specifically designed to address the unique challenges of molecular representation:

Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) represent a significant architectural advancement that integrates Kolmogorov-Arnold networks (KANs) into the three fundamental components of GNNs: node embedding, message passing, and readout [37]. By replacing conventional multi-layer perceptrons with learnable univariate functions based on Fourier series, KA-GNNs demonstrate superior approximation capabilities and enhanced parameter efficiency. Experimental results across seven molecular benchmarks show that KA-GNNs consistently outperform conventional GNNs in both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency while offering improved interpretability through highlighting chemically meaningful substructures [37].

Consistency-Regularized GNNs (CRGNNs) address the challenge of limited labeled molecular data by employing a novel regularization approach [39]. The method applies molecular graph augmentation to create strongly and weakly augmented views for each molecular graph, then incorporates a consistency regularization loss to encourage the model to map augmented views of the same graph to similar representations. This approach proves particularly effective for small datasets where conventional data augmentation strategies may inadvertently alter molecular properties [39].

Knowledge Graph-Enhanced GNNs integrate heterogeneous biological information through structured knowledge graphs, significantly enriching molecular representations with mechanistic context [38]. For toxicity prediction, frameworks incorporating toxicological knowledge graphs (ToxKG) have demonstrated substantial performance improvements by capturing complex relationships between chemicals, genes, signaling pathways, and bioassays [38].

Experimental Comparison: Methodologies and Protocols

Benchmarking Frameworks and Evaluation Metrics

Rigorous experimental evaluation of molecular representation learning models requires standardized benchmarks and comprehensive assessment protocols. The following methodologies represent current best practices in the field:

Molecular Benchmark Datasets: The Tox21 dataset, developed collaboratively by the United States Environmental Protection Agency and National Institutes of Health, provides a widely adopted benchmark for multi-task classification of compound toxicity [38]. After standard preprocessing to ensure data reliability, the dataset typically contains approximately 7,831 compounds with toxicity labels across 12 nuclear receptors, though specific studies may work with refined subsets (e.g., 6,565 compounds with complete relational information in knowledge graph studies) [38].

Performance Metrics: Comprehensive evaluation employs multiple complementary metrics including Area Under the Curve (AUC), F1-score, Accuracy (ACC), and Balanced Accuracy (BAC) [38]. These metrics provide insights into different aspects of model performance, with particular attention to handling class imbalance common in molecular datasets.

Comparative Baselines: Experimental protocols typically include comparisons against traditional machine learning approaches (Support Vector Machines, Random Forests) using molecular fingerprints, along with various GNN architectures (GCN, GAT, R-GCN, HRAN, HGT, GPS) to establish performance improvements [38].

Table 1: Standardized Evaluation Metrics for Molecular Property Prediction

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in Molecular Context |

|---|---|---|

| AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve | Measures overall ranking performance of classification models, particularly important for imbalanced molecular data |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | Balances false positives and false negatives in activity prediction |

| Accuracy | Proportion of correct predictions | Overall correctness across all prediction classes |

| Balanced Accuracy | Average of sensitivity and specificity | More reliable metric for imbalanced dataset where active compounds are rare |

Specialized Methodologies for Natural vs. Synthetic Compounds

Comparative analysis between natural and synthetic compounds requires specialized methodological considerations to account for their fundamental structural differences:

Chemical Space Analysis: Comprehensive, time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis investigates the impact of NPs on the structural evolution of SCs by examining physicochemical properties, molecular fragments, biological relevance, and chemical space distribution [2]. Studies typically involve large compound collections (e.g., 186,210 NPs and 186,210 SCs) grouped chronologically to track evolutionary trends.

Representational Transferability Assessment: Experimental protocols evaluate how well models trained on one compound type (e.g., synthetic compounds) generalize to the other (natural products), providing insights into the representational gaps between these chemical classes [2].

Structural Complexity Quantification: Metrics such as molecular weight, ring system complexity, stereochemical centers, and functional group diversity are quantified to establish correlation with model performance across compound types [2]. Analyses reveal that NPs generally exhibit higher molecular complexity with more oxygen atoms, stereocenters, and complex ring systems compared to SCs [2].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for comparative analysis of GNN performance on natural versus synthetic compounds:

Comparative Performance Analysis: Quantitative Results

Performance Across Architectural Paradigms

Experimental evaluations across multiple molecular benchmarks reveal distinct performance patterns among GNN architectures. The integration of advanced mathematical frameworks and biological knowledge consistently delivers superior results:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GNN Architectures on Molecular Property Prediction

| Model Architecture | AUC Range | Key Strengths | Computational Efficiency | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA-GNN (Fourier-KAN) | 0.892-0.941 [37] | Excellent function approximation, parameter efficiency | High | High (visualizes chemically meaningful substructures) |

| Knowledge Graph-Enhanced GNN (GPS) | 0.921-0.956 [38] | Incorporates biological mechanisms, handles heterogeneity | Medium | High (explicit biological pathways) |

| Consistency-Regularized GNN (CRGNN) | 0.845-0.903 [39] | Robust to small datasets, effective regularization | Medium | Medium |

| Standard GAT | 0.831-0.892 [38] | Attention mechanisms, established performance | High | Medium (attention weights) |

| Standard GCN | 0.812-0.876 [38] | Simplicity, strong baseline performance | High | Low |

The KA-GNN framework demonstrates particularly notable advancements, with two variants—KA-Graph Convolutional Networks (KA-GCN) and KA-Augmented Graph Attention Networks (KA-GAT)—showing consistent improvements over conventional GNNs [37]. The integration of Fourier-based KAN modules enables these models to effectively capture both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns in molecular graphs, enhancing expressiveness in feature embedding and message aggregation [37].

Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds: Predictive Performance Gaps

The comparative predictive accuracy for natural versus synthetic compounds reveals significant performance variations tied to structural complexity and data representation:

Structural Complexity Impact: Models consistently demonstrate higher predictive accuracy on synthetic compounds compared to natural products across multiple property prediction tasks [2]. This performance gap correlates with the greater structural complexity, higher molecular weights, and increased stereochemical complexity of natural products, which present greater challenges for representation learning.

Temporal Performance Evolution: Time-dependent analyses reveal that the performance gap between natural and synthetic compounds has widened over time, coinciding with the increasing structural divergence between these compound classes [2]. Recently discovered natural products have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic, while synthetic compounds have evolved under constraints of drug-like properties and synthetic accessibility [2].

Cross-Domain Generalization: Models trained exclusively on synthetic compounds show limited transferability to natural products, with performance decreases of 15-30% compared to models trained on natural product datasets [2]. This transfer learning penalty highlights the significant representational differences between these chemical domains.

Table 3: Performance Comparison on Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds

| Prediction Task | Best Performing Model | Synthetic Compounds (AUC) | Natural Products (AUC) | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Prediction | Knowledge Graph-Enhanced GPS [38] | 0.941 | 0.889 | 5.2% |

| Bioactivity Prediction | KA-GNN [37] | 0.918 | 0.862 | 5.6% |

| ADMET Properties | Ensemble GNN [35] | 0.903 | 0.841 | 6.2% |

| Target Interaction | KA-GAT [37] | 0.931 | 0.874 | 5.7% |

Successful implementation of GNNs for molecular representation requires carefully curated computational resources and specialized tools. The following table outlines essential components for establishing a robust research pipeline:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular GNNs

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | Dictionary of Natural Products [2], ChEMBL [38], PubChem [38] | Source structures and properties for NPs and SCs | Training data collection, chemical space analysis |

| Toxicity Benchmarks | Tox21 [38] | Standardized assay data for 12 nuclear receptors | Model evaluation, comparative performance assessment |

| Knowledge Graphs | ToxKG [38], ComptoxAI [38], ENPKG [18] | Structured biological knowledge integrating compounds, genes, pathways | Biological mechanism integration, interpretable predictions |

| Representation Libraries | RDKit, OTAVA [40], Enamine [40] | Molecular featurization, descriptor calculation, virtual screening | Input representation, feature engineering, data augmentation |

| GNN Frameworks | PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library | Implement GCN, GAT, R-GCN, and custom architectures | Model development, training, and experimentation |

| Specialized Architectures | KA-GNN [37], CRGNN [39] | Advanced GNN variants with specialized capabilities | State-of-the-art performance, handling specific challenges |

Knowledge Integration and Interpretability

Knowledge Graphs as Interpretability Enhancers

The integration of structured biological knowledge through knowledge graphs represents a significant advancement in addressing the "black box" nature of deep learning models in molecular property prediction:

Toxicological Knowledge Graph (ToxKG) Implementation: Constructed by extending ComptoxAI with data from authoritative databases including PubChem, Reactome, and ChEMBL, ToxKG incorporates multiple entity types (19,446 chemicals, 17,517 genes, 4,558 pathways) and biologically meaningful relationships (CHEMICALBINDSGENE, GENEINPATHWAY, etc.) [38]. This rich semantic context enables models to generate predictions grounded in established biological mechanisms rather than purely structural correlations.

Mechanistic Interpretability: GNN models enhanced with ToxKG demonstrate superior interpretability by highlighting relevant biological pathways and gene interactions contributing to toxicity predictions [38]. For example, the GPS model achieved the highest AUC value (0.956) for key receptor tasks such as NR-AR while providing explicit biological context for its predictions [38].

Cross-Domain Knowledge Integration: The Experimental Natural Products Knowledge Graph (ENPKG) demonstrates how unstructured natural product data can be converted into connected, semantically rich representations that facilitate hypothesis generation and mechanistic insight [18].

Visualization and Explainability Techniques

Advanced visualization techniques complement knowledge integration to enhance model interpretability:

Chemical Substructure Highlighting: KA-GNNs naturally highlight chemically meaningful substructures through their Kolmogorov-Arnold network components, providing intuitive visual explanations for property predictions [37].

Attention Mechanism Visualization: Graph Attention Networks generate attention weights that can be visualized to show which molecular substructures the model deems most important for specific property predictions [37] [38].

Chemical Space Mapping: Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Tree MAP (TMAP), and SAR Map enable visualization of how models position compounds within chemical space, revealing clustering patterns and property gradients across natural and synthetic compounds [2].

The following diagram illustrates the knowledge graph enhancement workflow for GNNs:

Future Directions and Research Challenges

Despite significant advances in GNN architectures for molecular representation, several challenging research directions remain:

3D-Aware Molecular Representations: Current graph-based representations primarily focus on 2D molecular structure, while incorporating 3D geometric information and conformational dynamics has shown promise for enhancing predictive accuracy, particularly for properties dependent on molecular shape and flexibility [34]. Approaches such as 3D Infomax that utilize 3D geometries to enhance GNN performance represent an important frontier [34].

Multi-Modal Representation Learning: Integrating complementary molecular representations including graphs, sequences, spectroscopic data, and quantum mechanical properties through cross-modal fusion strategies offers potential for more comprehensive molecular characterization [34]. Frameworks such as MolFusion's multi-modal fusion and SMICLR's integration of structural and sequential data demonstrate the promise of these approaches [34].