Molecular Representations for ADMET Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and AI-Driven Approaches

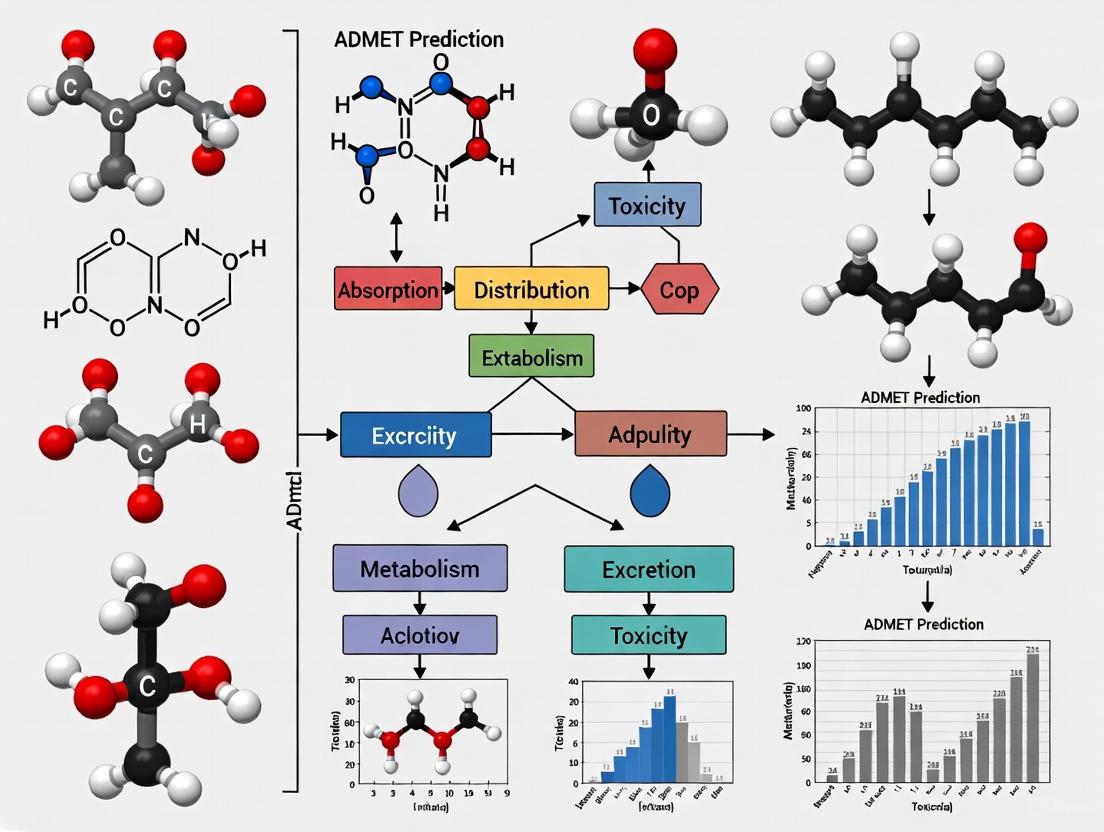

Accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is crucial for reducing late-stage failures in drug discovery.

Molecular Representations for ADMET Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and AI-Driven Approaches

Abstract

Accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is crucial for reducing late-stage failures in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of molecular representation methods, from traditional fingerprints and descriptors to modern AI-driven embeddings. It explores foundational concepts, practical methodologies, common troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation techniques. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent benchmarking studies to offer actionable insights for selecting, optimizing, and validating molecular representations to improve the efficiency and accuracy of ADMET prediction models.

Understanding Molecular Representation: From SMILES to AI Embeddings

The Critical Role of ADMET Prediction in Modern Drug Discovery

The prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical frontier in modern drug discovery, standing as the primary defense against costly late-stage clinical failures. Historical analyses reveal that approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition is directly attributable to unfavorable ADMET properties, making it the single largest cause of drug development failure [1] [2]. This staggering statistic underscores why pharmaceutical companies now prioritize ADMET assessment early in the discovery pipeline, shifting from a traditional sequential approach to a parallelized strategy that evaluates pharmacokinetic and safety profiles alongside therapeutic potency. The economic imperative is clear: with the average cost of developing a single new drug estimated to easily exceed $2 billion, early identification of ADMET liabilities can save hundreds of millions of dollars in development costs and several years of research effort [3].

The evolution of ADMET prediction has undergone a revolutionary transformation, moving from resource-intensive experimental methods to sophisticated in silico approaches that leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning. Traditional in vitro and in vivo methods, while reliable, are characterized by being time-consuming, expensive, and low-throughput, making them impractical for screening large compound libraries [4] [3]. Computational methods now facilitate the acquisition of toxicity information for molecules with elucidated chemical structures expeditiously, reproducibly, and at reduced cost, thereby reducing the number of animals required for analyses [5]. This paradigm shift has positioned ADMET prediction as both a gatekeeper for candidate selection and an optimization tool for medicinal chemists seeking to improve compound profiles through structural modification.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches for ADMET Prediction

Fundamental Methodologies and Molecular Representations

The accuracy of ADMET prediction is fundamentally constrained by the choice of molecular representation and algorithmic approach. Research indicates that no single representation universally outperforms others across all ADMET endpoints, necessitating a nuanced understanding of their respective strengths and limitations [6].

Classical Descriptors and Fingerprints: Traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models typically employ molecular descriptors (mathematical representations of chemical and physical properties) and fingerprints (binary vectors representing molecular substructures). While widely used, these representations provide a simplified view of molecular structure and may not capture all relevant features affecting ADMET properties [3]. The RDKit toolkit provides standardized implementations of these representations, with RDKit descriptors and Morgan fingerprints being particularly prevalent in benchmarking studies [6] [4].

Graph-Based Representations: Graph neural networks (GNNs) represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, directly learning relevant features from the molecular structure itself without requiring pre-computed descriptors [3]. This approach inherently captures atomic connectivity and stereochemistry, potentially modeling complex structure-property relationships more effectively. The message-passing neural network (MPNN) architecture, implemented in packages like Chemprop, has demonstrated particular effectiveness for molecular property prediction [6] [4].

Multi-View and Multi-Task Frameworks: Advanced frameworks like MolP-PC integrate multiple representation types—1D molecular fingerprints, 2D molecular graphs, and 3D geometric representations—using attention-gated fusion mechanisms. This multi-view approach captures complementary molecular information, with multi-task learning significantly enhancing predictive performance on small-scale datasets [7]. Similarly, the OmniMol framework formulates molecules and properties as a hypergraph to extract relationships among properties, molecule-to-property, and among molecules, addressing the challenge of imperfectly annotated data common in ADMET datasets [8].

Performance Benchmarking of Predictive Software and Algorithms

Comprehensive benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of different computational tools and algorithms. A landmark evaluation of twelve QSAR software tools for predicting 17 physicochemical and toxicokinetic properties confirmed the adequate predictive performance of the majority of selected tools, with models for PC properties (R² average = 0.717) generally outperforming those for TK properties (R² average = 0.639 for regression) [9].

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of ADMET Prediction Software

| Software/Algorithm | Best Application Context | Key Strengths | Supported Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [5] | Microcystin toxicity evaluation, lipophilicity, permeability | >70 models with valid predictions; consistent results | Extensive coverage including transport proteins, environmental biodegradation |

| XGBoost [4] | Caco-2 permeability prediction | Superior performance with molecular fingerprints and descriptors; handles public-to-private data transfer | Regression tasks for permeability and related physicochemical properties |

| SwissADME [5] | General screening | Freely accessible; user-friendly interface | Basic physicochemical and pharmacokinetic parameters |

| Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN) [6] | Data-rich environments with complex relationships | Direct learning from molecular structure; state-of-the-art on many benchmarks | Broad applicability across classification and regression tasks |

| Federated Learning [1] | Multi-organizational collaboration | Expands chemical space coverage without sharing proprietary data | Cross-pharma QSAR without compromising proprietary information |

For specific ADMET endpoints, algorithm performance varies significantly. In predicting Caco-2 permeability—a critical determinant of oral bioavailability—comprehensive validation found that XGBoost generally provided better predictions than comparable models, including random forests, support vector machines, and deep learning approaches like DMPNN [4]. However, the optimal algorithm and representation combination remains highly dataset-dependent, with no single approach universally dominating across all ADMET endpoints [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

Robust evaluation of ADMET prediction models requires standardized protocols that address data quality, representation selection, and statistical validation. Leading research groups have converged on a multi-stage experimental workflow that ensures reliable and reproducible comparisons [6].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for ADMET Model Evaluation

Data Collection and Curation: The initial phase involves gathering datasets from public sources such as ChEMBL, PubChem, and specialized collections like the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [6] [10]. This is followed by rigorous data cleaning including standardization of SMILES representations, neutralization of salts, removal of duplicates, and treatment of inconsistent measurements. For Caco-2 permeability modeling, one protocol merged three public datasets, applied logarithmic transformation to permeability values, excluded entries with standard deviation >0.3 for duplicates, and used RDKit's MolStandardize for molecular standardization, resulting in a curated set of 5,654 non-redundant compounds [4].

Molecular Representation Selection: Researchers typically evaluate multiple representation types including molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit 2D descriptors), fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints), and graph-based representations. Feature selection may involve iterative combination of representations informed by statistical testing rather than simply concatenating all available features [6].

Model Training with Scaffold Splitting: To assess generalization capability rather than mere interpolation, datasets are typically split using scaffold-based division, which separates compounds with distinct molecular frameworks, ensuring that models are tested on structurally novel compounds [6] [4]. This approach more closely mimics real-world drug discovery scenarios where predictions are needed for novel chemotypes.

Cross-Validation with Statistical Testing: Beyond simple hold-out validation, robust protocols employ cross-validation combined with statistical hypothesis testing to determine whether performance differences between models are statistically significant rather than random variations [6].

Practical Scenario Validation: The final validation stage tests model transferability by evaluating performance on external datasets from different sources, such as pharmaceutical company proprietary data, simulating real-world application where models trained on public data must generalize to novel compound libraries [6] [4].

Emerging Protocols: Federated Learning and Multi-Organizational Collaboration

Traditional isolated modeling efforts face fundamental limitations due to the restricted chemical space covered by any single organization's data. Federated learning has emerged as a transformative protocol that enables multiple pharmaceutical companies to collaboratively train models without sharing proprietary data [1]. The MELLODDY project demonstrated that federation systematically extends a model's effective domain, with federated models consistently outperforming local baselines across various ADMET endpoints. Performance improvements scale with the number and diversity of participants, with multi-task settings yielding the largest gains, particularly for pharmacokinetic and safety endpoints where overlapping signals amplify one another [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental landscape for ADMET prediction relies on a sophisticated toolkit of software libraries, datasets, and computational resources that enable rigorous model development and validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for ADMET Prediction

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit, OpenBabel | Molecular standardization, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation | Open Source |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM | Implementation of classical ML algorithms | Open Source |

| Deep Learning Platforms | Chemprop, DeepChem, PyTorch Geometric | Graph neural networks and message passing architectures | Open Source |

| Benchmark Datasets | TDC, MoleculeNet, PharmaBench | Curated ADMET datasets for model training and benchmarking | Public Access |

| Specialized Prediction Suites | ADMETlab 2.0, admetSAR | Pre-trained models for specific ADMET endpoints | Web Services |

| Federated Learning Platforms | Apheris, kMoL | Privacy-preserving collaborative modeling | Commercial/Open Source |

The PharmaBench dataset represents a significant advancement in benchmarking resources, addressing limitations of previous collections through a multi-agent LLM system that extracted experimental conditions from 14,401 bioassays [10]. Unlike earlier benchmarks that contained only a fraction of publicly available data and compounds unrepresentative of drug discovery projects, PharmaBench comprises 52,482 entries across eleven ADMET properties, with molecular weights more closely aligned with typical drug-like compounds (300-800 Dalton) [10].

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The field of ADMET prediction stands at an inflection point, with several emerging trends poised to further transform its role in drug discovery. Multi-task frameworks that jointly learn correlated properties demonstrate enhanced performance, particularly for small datasets, by leveraging shared information across endpoints [7] [8]. Explainable AI approaches are increasingly integrated into predictive models, providing mechanistic insights that extend beyond black-box predictions to offer medicinal chemists actionable guidance for molecular optimization [8]. The integration of 3D structural information and conformational awareness through innovative architectures like SE(3)-equivariant networks addresses critical limitations in chirality recognition and stereochemistry-dependent property prediction [8].

As machine learning performance becomes increasingly limited by data availability rather than algorithmic sophistication, federated learning and other privacy-enhancing technologies will likely become standard practice, enabling collaborative model improvement while preserving intellectual property protection [1]. These advances, combined with increasingly rigorous benchmarking practices and more representative datasets, are steadily closing the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality, positioning ADMET prediction as an indispensable pillar of modern drug discovery that systematically reduces attrition rates and accelerates the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

Molecular representation serves as the foundational step in computational chemistry and drug design, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties [11]. These representations translate molecules into mathematical or computational formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior [11]. In the context of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction research, effective molecular representation is particularly crucial for tasks such as virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping [11]. Traditional molecular representation methods have laid a strong foundation for many computational approaches in drug discovery, relying primarily on three core methodologies: molecular descriptors that quantify physical and chemical properties, molecular fingerprints that encode substructural information, and string-based representations like SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) that provide linear notations of molecular structure [11]. This comparative analysis examines the performance characteristics, experimental applications, and relative advantages of these traditional representation methods within modern ADMET prediction research, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection in drug development workflows.

Methodological Foundations

Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors constitute a fundamental approach to molecular representation that quantifies the physical or chemical properties of molecules through numerical values [11]. These descriptors encompass a wide range of molecular characteristics, including basic properties like molecular weight and hydrophobicity, as well as more complex topological indices that capture structural information [11]. Methods such as alvaDesc and RDKit descriptors provide comprehensive sets of these numerical features that describe various aspects of molecular structure and properties [11]. In ADMET prediction research, descriptors have demonstrated particular utility in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, where they serve as input features for predicting biological activity and pharmacokinetic properties [11] [12]. For instance, in the FP-ADMET framework, researchers combined molecular descriptors with machine learning models to establish robust prediction frameworks for a wide range of ADMET-related properties [11]. Similarly, the BoostSweet framework leveraged a soft-vote ensemble model based on LightGBM that combined layered fingerprints with alvaDesc molecular descriptors to predict molecular sweetness, demonstrating the continued relevance of descriptors in specialized property prediction tasks [11].

Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints represent another cornerstone of traditional molecular representation, typically encoding substructural information as binary strings or numerical values [11]. The most widely used fingerprint approach is the extended-connectivity fingerprint (ECFP), which captures local atomic environments in a compact and efficient manner, making them invaluable for representing complex molecules [11]. These fingerprints function by identifying circular substructures around each atom in a molecule up to a certain radius and then hashing these substructures into a fixed-length bit vector [11]. The binary nature of these representations makes them computationally efficient for similarity search, clustering, and virtual screening tasks [12]. In modern implementations, fingerprints have been adapted for use with deep learning approaches, as demonstrated by the FP-BERT model, which employs a substructure masking pre-training strategy on ECFP fingerprints to derive high-dimensional molecular representations, then leverages CNNs to extract high-level features for classification or regression tasks [11]. The computational efficiency and concise format of fingerprints have maintained their relevance in contemporary ADMET prediction research, particularly for similarity-based virtual screening and as input features for machine learning models [11].

SMILES Representations

The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) provides a compact and efficient way to encode chemical structures as strings using ASCII characters [11]. Introduced in 1988 by Weininger et al., SMILES strings represent molecular graphs as linear sequences of atoms, bonds, and branching information using a small set of grammar rules [11]. This approach offers the advantage of being human-readable while maintaining computational efficiency for storage and processing [11]. Subsequent improvements led to extended versions like ChemAxon Extended SMILES (CXSMILES), OpenSMILES, and SMILES Arbitrary Target Specification (SMARTS) to extend the functionalities of the original SMILES system [11]. Despite the development of alternative representations such as the International Chemical Identifier (InChI) by IUPAC in 2005, SMILES remains the mainstream molecular representation method, largely because InChI cannot guarantee decoding back to their original molecular graphs and SMILES offers superior human readability [11]. However, SMILES has inherent limitations in capturing the full complexity of molecular interactions, particularly as drug discovery tasks grow more sophisticated and require reflection of intricate relationships between molecular structure and key drug-related characteristics such as biological activity and physicochemical properties [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Frameworks and Benchmarking

The evaluation of traditional molecular representations in ADMET prediction research employs rigorous experimental frameworks that focus on dataset diversity, model selection, and performance metrics. Contemporary benchmarking studies typically utilize publicly available datasets from sources such as the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC), which provides standardized ADMET-related datasets for model comparison [12]. These benchmarks encompass a range of ADMET properties, including permeability (Caco-2), lipophilicity (LogD), plasma protein binding, toxicity (LD50), volume of distribution, half-life, metabolic clearance, bioavailability, intestinal absorption, blood-brain barrier penetration, and cytochrome P450 inhibition [12]. Studies typically employ cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing to ensure robust model comparison, moving beyond simple hold-out test sets to provide more reliable performance assessments [12]. Practical scenario evaluations, where models trained on one data source are tested on different external datasets, further validate the real-world applicability of these representations [12]. The field has observed a trend toward systematic feature selection processes that statistically justify the choice of molecular representation rather than arbitrarily combining different representations without systematic reasoning [12].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional Molecular Representations Across ADMET Tasks

| Representation Type | Sample Dataset | Performance Metric | Model Architecture | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Lipophilicity (LogD) | MAE: 0.48-0.62 | Random Forest | Strong performance for physicochemical properties [12] |

| Molecular Fingerprints (ECFP) | Caco-2 Permeability | ROC-AUC: 0.76-0.82 | SVM, Random Forest | Effective for binary classification tasks [12] |

| SMILES Strings | BBB Penetration | Accuracy: 0.71-0.79 | Transformer-based Models | Captures sequential patterns but struggles with stereochemistry [11] |

| Combined Descriptors + Fingerprints | hERG Inhibition | ROC-AUC: 0.80-0.85 | Gradient Boosting Machines | Enhanced performance through feature complementarity [12] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Plasma Protein Binding | R²: 0.58-0.67 | Neural Networks | Better for continuous endpoint prediction [12] |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Research comparing the effectiveness of traditional molecular representations reveals a complex performance landscape where optimal representation choice depends significantly on the specific ADMET task, dataset characteristics, and model architecture. In comprehensive benchmarking studies, classical descriptors and fingerprints frequently remain competitive with more complex deep learning representations, particularly for smaller datasets [12]. For instance, in a systematic assessment of ADMET prediction models, random forest algorithms using radial fingerprints demonstrated robust performance across multiple ADMET datasets, with the optimal model and feature choices being highly dataset-dependent [12]. Similarly, recent studies have found that fixed representations (including traditional fingerprints and descriptors) generally outperform learned representations in many ADMET prediction tasks, challenging the assumption that more complex representations invariably yield superior results [12]. The MolMapNet approach, which transforms large-scale molecular descriptors and fingerprint features into two-dimensional feature maps and uses convolutional neural networks to predict molecular properties, demonstrates how traditional representations can be adapted for deep learning architectures while maintaining interpretability [11]. This approach captures intrinsic correlations of complex molecular properties while leveraging the well-established predictive power of traditional descriptors and fingerprints.

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Traditional Molecular Representations in ADMET Prediction

| Representation | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Direct physicochemical interpretation; Computational efficiency; QSAR compatibility | Limited structural resolution; Challenges with complex molecular interactions | Early-stage drug screening; QSAR modeling; Property-focused optimization |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Structural pattern capture; High similarity search efficiency; Substructure identification | Fixed representation constraints; Limited spatial information; Hashing collisions | Virtual screening; Compound clustering; Scaffold hopping |

| SMILES | Human readability; Compact storage; Sequential pattern learning | Syntax sensitivity; Stereochemistry limitations; Structural ambiguity | Sequence-based deep learning; Transfer learning; Chemical language processing |

Integration with Modern Learning Paradigms

Hybrid Approaches

Traditional molecular representations have demonstrated remarkable adaptability through integration with modern machine learning and deep learning approaches, creating hybrid models that leverage both well-established chemical knowledge and data-driven pattern recognition. These hybrid approaches frequently combine multiple representation types to overcome the limitations of individual methods [12]. For example, studies have systematically investigated the concatenation of different compound representations, finding that carefully selected combinations can yield performance improvements over single-representation models [12]. The MolP-PC framework exemplifies this trend, implementing a multi-view fusion and multi-task learning approach that integrates 1D molecular fingerprints, 2D molecular graphs, and 3D geometric representations [7]. This framework incorporates an attention-gated fusion mechanism and multi-task adaptive learning strategy for precise ADMET property predictions, demonstrating that traditional fingerprints continue to provide valuable information when combined with more complex representations [7]. Experimental results show that MolP-PC achieves optimal performance in 27 of 54 tasks, with its multi-task learning mechanism significantly enhancing predictive performance on small-scale datasets and surpassing single-task models in 41 of 54 tasks [7]. Similarly, descriptor augmentation approaches have been successfully applied to unsupervised embedding methods like Mol2Vec, with combined representations outperforming single-modality representations across multiple ADMET benchmarks [13].

Specialized Applications

The adaptation of traditional representations for specialized ADMET prediction tasks further illustrates their ongoing evolution and utility in targeted drug discovery applications. For instance, the DeepDelta approach addresses the challenge of predicting property differences between molecular derivatives, which is crucial for lead optimization in drug development [14]. This method processes pairs of molecules using traditional fingerprint representations (Morgan circular fingerprints with radius 2, 2048 bits) and demonstrates significantly improved performance in predicting ADMET property differences compared to established molecular machine learning algorithms [14]. On 10 ADMET benchmark tasks, DeepDelta significantly outperformed the directed message passing neural network (D-MPNN) ChemProp and Random Forest using radial fingerprints for 70% of benchmarks in terms of Pearson's r and 60% of benchmarks in terms of mean absolute error (MAE) [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for predicting large differences in molecular properties and performing scaffold hopping, demonstrating how traditional fingerprint representations can be adapted for specialized molecular comparison tasks that are central to lead optimization in drug discovery [14]. The continued relevance of traditional representations in these specialized contexts highlights their fundamental utility in chemical space navigation, even as more complex deep learning approaches emerge.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Workflows

Robust experimental protocols for evaluating traditional molecular representations in ADMET prediction incorporate several critical components to ensure reliable and reproducible results. A standardized approach begins with comprehensive data cleaning procedures to address common issues in public ADMET datasets, including inconsistent SMILES representations, duplicate measurements with varying values, and inconsistent binary labels [12]. Following data curation, studies typically implement iterative feature selection processes to identify optimal representation combinations, moving beyond the conventional practice of combining different representations without systematic reasoning [12]. Model training incorporates rigorous cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing, adding a layer of reliability to model assessments that surpasses simple hold-out validation [12]. Finally, practical scenario evaluation tests models trained on one data source against external test sets from different sources, providing critical insights into real-world applicability and generalization capability [12]. This comprehensive workflow ensures that performance comparisons between different molecular representations reflect true predictive capabilities rather than dataset-specific artifacts or optimization biases.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating traditional molecular representations in ADMET prediction, covering from structure representation to performance validation.

Data Partitioning and Validation Strategies

Effective experimental protocols for ADMET prediction research require careful attention to data partitioning and validation strategies that reflect real-world application scenarios. For traditional molecular representations, which can be susceptible to overfitting and limited generalization, appropriate validation approaches are particularly important. Cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing provides a more robust model comparison framework than single hold-out test sets, allowing researchers to assess performance consistency across different data splits [12]. For pairwise comparison approaches like DeepDelta, specialized data partitioning prevents data leakage by ensuring that training data is first split into train and test sets prior to cross-merging to create molecule pairings, guaranteeing that each molecule appears exclusively in either training or test set pairs [14]. External validation using completely independent datasets from different sources provides the most rigorous assessment of model generalizability, testing the practical utility of representations beyond their original training distribution [12]. Temporal splits, where models are trained on older compounds and tested on newer ones, offer another validation approach that simulates real-world drug discovery workflows where predictions are made for novel chemical entities [12]. These comprehensive validation strategies are essential for producing reliable performance comparisons between traditional molecular representations and their modern counterparts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Traditional Molecular Representation Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Generation of molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and SMILES processing [12] |

| alvaDesc | Molecular descriptor calculation | Comprehensive descriptor generation for QSAR modeling [11] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Curated ADMET datasets | Standardized benchmarking and performance comparison [12] |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP) | Circular substructure representation | Similarity searching, virtual screening, and machine learning features [11] |

| SMILES Strings | Linear molecular notation | Sequence-based modeling and chemical language processing [11] |

| Matched Molecular Pairs (MMP) | Structural change analysis | Property difference prediction and scaffold hopping [14] |

Traditional molecular representations—descriptors, fingerprints, and SMILES—continue to play vital roles in ADMET prediction research despite the emergence of sophisticated deep learning approaches. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that these established methods maintain competitive performance across diverse ADMET tasks, particularly when strategically combined or adapted for modern machine learning architectures. Molecular descriptors provide chemically interpretable features with strong performance for physicochemical property prediction, molecular fingerprints offer efficient structural pattern recognition for similarity-based applications, and SMILES strings enable sequential pattern learning in language-model contexts. The optimal selection among these representations depends critically on specific research objectives, dataset characteristics, and computational constraints. Hybrid approaches that intelligently combine traditional representations with modern learning paradigms demonstrate particular promise for advancing ADMET prediction accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency and interpretability. As the field progresses, the integration of traditional chemical knowledge embodied in these representations with data-driven pattern recognition will continue to accelerate drug discovery by enabling more reliable in silico ADMET assessment.

The optimization of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a pivotal challenge in modern drug discovery, with approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition still attributed to ADMET liabilities [1]. Traditional molecular representation methods, including molecular descriptors and fingerprints, have long served as the foundation for computational prediction models. However, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has catalyzed a significant shift toward more sophisticated representation learning techniques, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs) and language models (LMs) [11].

These AI-driven approaches fundamentally differ from traditional rule-based representations by learning continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from molecular data, enabling more nuanced capture of structure-property relationships [11]. This comparative analysis examines the capabilities, performance, and implementation considerations of graph-based and language model-based representations specifically within the context of ADMET prediction, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection.

Molecular Representation Paradigms

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph-based representations conceptualize molecules as mathematical graphs where atoms constitute nodes and bonds form edges [3] [15]. This approach provides a natural structural representation that explicitly encodes molecular topology. Graph Neural Networks leverage this structure through message-passing mechanisms where atom representations are iteratively updated by aggregating information from neighboring atoms [15].

In typical implementations, each atom node is described by a feature vector containing atomic properties (e.g., atom type, formal charge, hybridization), while edges encode bond characteristics [3]. The GNN processes this graph through multiple layers, with each layer extending the receptive field by aggregating information from more distant neighbors. Finally, a readout function generates a holistic molecular representation from the updated atom features [15]. Attention-based GNNs, such as Attentive FP, further enhance this process by learning to weight the importance of different atoms and bonds during aggregation [3].

Language Models (LMs)

Language model-based approaches treat molecular representations as sequences, typically using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings as a specialized chemical language [11] [16]. Inspired by advances in natural language processing, models like Transformers process these sequences by tokenizing molecular strings at the atomic or substructure level [11].

Each token is mapped to a continuous vector representation, which is then processed through self-attention mechanisms that capture long-range dependencies across the molecular sequence [11] [16]. Recent advancements have seen the application of large language models (LLMs) to molecular representation, enabling few-shot learning and transfer learning capabilities [17] [16]. These models can be pre-trained on massive unlabeled molecular datasets and subsequently fine-tuned for specific ADMET prediction tasks.

Performance Comparison for ADMET Prediction

Quantitative Benchmarking

Table 1: Performance comparison of representation methods across ADMET tasks

| Representation Method | Model Examples | Key ADMET Applications | Reported Performance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph-based Models | GCN, GAT, MPNN, Attentive FP | CYP inhibition, solubility, toxicity, permeability [3] [15] | Outstanding on larger/multi-task datasets; Matches or outperforms descriptors on most endpoints [15] | High training cost; Requires specialized implementation [15] |

| Language Models | Transformer-based architectures, BERT-style models | Multi-task ADMET prediction, data curation [17] [11] | State-of-the-art on certain tasks with sufficient data [11] | Moderate to high computational requirements [11] |

| Traditional Descriptors | SVM, XGBoost, Random Forest | Broad ADMET endpoints, especially solubility, CYP inhibition [15] | SVM best for regression; RF/XGBoost reliable for classification [15] | Excellent efficiency (seconds for large datasets) [15] |

Table 2: Direct performance comparison on benchmark datasets [15]

| Dataset | Task Type | Best Descriptor Model (Metric) | Best Graph Model (Metric) | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESOL | Regression (Solubility) | SVM (Best MAE/R²) | Attentive FP | Descriptor-based superior |

| FreeSolv | Regression (Solvation) | SVM (Best MAE/R²) | Attentive FP | Descriptor-based superior |

| BBBP | Classification (Permeability) | RF/XGBoost (Best AUC) | Attentive FP | Comparable performance |

| HIV | Classification (Inhibition) | RF/XGBoost (Best AUC) | GCN, Attentive FP | Graph-based superior |

| Tox21 | Classification (Toxicity) | RF/XGBoost (Best AUC) | Attentive FP | Graph-based superior |

Contextual Performance Analysis

Comparative studies reveal that the performance superiority between representation methods is highly task-dependent. While graph-based models demonstrate particular strength for complex molecular interactions and multi-task learning [15], traditional descriptor-based models using algorithms like SVM and XGBoost remain highly competitive, especially for regression tasks and when computational efficiency is prioritized [15].

For specific ADMET endpoints like cytochrome P450 inhibition and solubility, attention-based GNNs have shown remarkable effectiveness by focusing on structurally significant molecular regions [3]. However, a comprehensive evaluation across 11 public datasets demonstrated that descriptor-based models generally outperformed graph-based models in both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency, with SVM achieving the best performance for regression tasks and both Random Forest and XGBoost providing reliable classification [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Graph Neural Network Implementation

Molecular Graph Construction: Molecules are represented as graphs G = (V, E) with atoms as nodes (V) and bonds as edges (E). The adjacency matrix A ∈ R^(N×N) encodes connectivity, where N is the number of atoms [3]. Each node is associated with a feature vector containing atomic properties (atom type, formal charge, hybridization, ring membership, aromaticity, chirality) using one-hot encoding [3].

GNN Architecture: Attention-based GNNs employ a message-passing framework where node representations are updated iteratively. The attention mechanism computes attention coefficients to weight neighbor contributions during aggregation [3]. The model uses multiple adjacency matrices (A₁-A₅) to represent different bond types: all bonds, single, double, triple, and aromatic bonds, enabling specialized processing of distinct molecular substructures [3].

Training Protocol: Models are typically evaluated using five-fold cross-validation on large publicly available datasets (≥4,200 compounds). The loss function is selected according to the task type (e.g., mean squared error for regression, cross-entropy for classification) [3] [15].

Language Model Implementation

Data Preprocessing and Curation: LLMs facilitate automated data extraction from biomedical databases. A multi-agent LLM system identifies experimental conditions from assay descriptions in sources like ChEMBL, addressing variability in experimental protocols that complicate data integration [17].

Model Architecture: Transformer-based architectures process tokenized SMILES strings using self-attention layers. Pre-training often employs masked token prediction objectives to learn fundamental chemical principles [11].

Training Strategy: Models are typically pre-trained on large unlabeled molecular datasets (e.g., 14,401 bioassays with 97,609 entries) then fine-tuned on specific ADMET endpoints. Data standardization and filtering ensure consistency in experimental conditions and units [17].

Benchmarking Methodology

Dataset Selection: Standardized benchmarks like PharmaBench provide curated ADMET datasets with 52,482 entries across 11 properties, ensuring consistent evaluation [17]. Scaffold-based splitting evaluates model generalization to novel chemotypes, while random splitting assesses overall performance [15].

Evaluation Metrics: Regression tasks use Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R², while classification tasks employ Area Under the Curve (AUC) and balanced accuracy [15]. Statistical significance testing compares performance distributions across multiple training runs rather than single scores [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research tools for AI-driven ADMET prediction

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network Frameworks | PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library | GNN model implementation | Molecular graph representation and processing [3] |

| Language Model Platforms | Transformer libraries (Hugging Face) | Pre-trained LM fine-tuning | SMILES-based molecular representation [11] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit | Molecular graph generation from SMILES, descriptor calculation | Data preprocessing and traditional baseline [15] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC), PharmaBench | Standardized performance evaluation | Model comparison and validation [17] [15] |

| Federated Learning Systems | Apheris Federated ADMET Network, MELLODDY | Cross-institutional model training | Privacy-preserving collaborative learning [1] |

| Data Curation Tools | LLM-based multi-agent systems | Experimental condition extraction | Automated dataset compilation [17] |

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The convergence of AI with computational chemistry continues to evolve, with several promising developments emerging. Hybrid models that integrate graph-based and language model approaches show potential for capturing both structural and sequential molecular characteristics [11]. Federated learning frameworks enable collaborative model training across pharmaceutical organizations without sharing proprietary data, systematically expanding chemical space coverage and improving generalizability [1].

The integration of large language models in data curation addresses critical bottlenecks in benchmark quality, with systems like the multi-agent LLM approach enabling processing of 14,401 bioassays to create comprehensive resources like PharmaBench [17]. As model performance becomes increasingly limited by data quality and diversity rather than algorithms, these approaches to expanding and curating training datasets will grow in importance [1] [17].

Additionally, the rise of multimodal learning strategies that combine molecular representation with biological context (e.g., protein structures, assay conditions) promises to enhance predictive accuracy for complex ADMET endpoints [11]. As these technologies mature, they offer the potential to substantially reduce late-stage attrition in drug development by providing more reliable early-stage ADMET assessment.

Accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical bottleneck in modern drug discovery. While artificial intelligence and machine learning promise to revolutionize this domain, their effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by three interconnected challenges: data quality limitations, standardization deficiencies, and inadequate chemical space coverage in public benchmarks. These issues collectively undermine model reliability and generalizability, contributing to the persistent high failure rates in drug development, where approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition is still attributed to ADMET liabilities [1].

Recent analyses of public ADMET datasets have revealed substantial distributional misalignments and inconsistent property annotations between gold-standard and popular benchmark sources [18]. Simultaneously, systematic evaluations of existing tools highlight how data heterogeneity introduces noise that ultimately degrades model performance [9]. This comparative analysis examines how these core challenges manifest across current approaches and evaluates emerging solutions aimed at creating more robust, reliable ADMET prediction frameworks for drug discovery professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Current Dataset Limitations

Data Quality and Standardization Deficiencies

Data quality issues permeate public ADMET resources, originating from multiple sources including experimental variability, inconsistent reporting, and aggregation artifacts. Studies systematically comparing benchmark sources have identified significant inconsistencies that compromise predictive modeling efforts.

Table 1: Common Data Quality Issues in Public ADMET Datasets

| Issue Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Variability | Different buffer types, pH levels, assay procedures for solubility measurements [10] | Same compound exhibits different property values under different conditions |

| Annotation Inconsistencies | Conflicting binary labels for identical SMILES strings across train/test sets [6] | Introduces contradictory learning signals during model training |

| Measurement Ambiguity | Duplicate compounds with significantly varying experimental values (>20% IQR) [6] | Increases noise and reduces model confidence |

| Representation Problems | Multiple organic compounds in fragmented SMILES, salt forms without standardization [6] | Invalid feature representation and erroneous structure-property relationships |

The Johnson & Johnson in-house solubility study demonstrated how systematic noise, particularly from amorphous solid forms present post-solubility measurement, introduces biased positive errors that cannot be overcome simply by increasing dataset size [19]. This highlights a critical limitation in many public datasets where insufficient metadata about experimental conditions prevents appropriate filtering and normalization.

Chemical Space Coverage Limitations

Beyond quality issues, public benchmarks suffer from fundamental representational gaps that limit their utility for drug discovery applications. Comparative analyses reveal significant mismatches between the chemical space covered by public datasets and the structural diversity encountered in industrial drug discovery pipelines.

Table 2: Chemical Space Coverage Gaps in Public ADMET Benchmarks

| Benchmark Dataset | Typical Molecular Weight Range | Drug Discovery Relevance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESOL (MoleculeNet) | Mean 203.9 Dalton [10] | Low | Compounds substantially smaller than typical drug molecules |

| PharmaBench | 300-800 Dalton (drug-like focus) [10] | High | Specifically designed to address coverage gaps in earlier benchmarks |

| Traditional QSAR Sets | Varies, often limited scaffolds | Moderate to Low | Often overrepresent specific chemical classes while underrepresenting others |

| Proprietary Corporate Data | 300-800 Dalton (optimized) [20] | High | Comprehensive coverage including negative results and failed compounds |

The PharmaBench initiative explicitly addressed these limitations by creating a benchmark encompassing 52,482 entries from 14,401 bioassays, specifically designed to better represent compounds encountered in actual drug discovery projects [10]. This represents a significant scaling from earlier benchmarks like MoleculeNet, which included only 1,128 compounds in its ESOL solubility dataset despite thousands of relevant entries being available in PubChem [10].

Experimental Approaches for Addressing Data Challenges

Data Curation and Standardization Methodologies

Recent studies have established rigorous protocols for ADMET data curation to address quality concerns. The workflow typically involves multiple standardization and filtering steps:

- Molecular Standardization: Using tools like the RDKit cheminformatics toolkit to generate canonical SMILES, neutralize salts, and normalize functional group representation [6]

- Duplicate Resolution: Identifying compounds with multiple measurements and retaining values only when consistent (within 20% of inter-quartile range for regression, identical labels for classification) [6]

- Outlier Detection: Applying Z-score analysis (removing points with Z > 3) to identify experimental anomalies [9]

- Inter-dataset Consistency: Comparing values for compounds appearing across multiple datasets and removing those with standardized standard deviation > 0.2 [9]

The application of these methods in one comprehensive review resulted in the curation of 41 validation datasets (21 for physicochemical properties, 20 for toxicokinetic properties) that supported more reliable benchmarking of 12 QSAR tools [9].

Figure 1: Experimental Data Curation Workflow

Novel Data Mining and Integration Frameworks

Advanced computational approaches are emerging to address the fundamental challenges in ADMET data aggregation. One significant innovation involves using large language models (LLMs) to extract structured experimental conditions from unstructured assay descriptions.

The PharmaBench project implemented a multi-agent LLM system consisting of three specialized components [10]:

- Keyword Extraction Agent (KEA): Identifies and summarizes key experimental conditions from assay descriptions

- Example Forming Agent (EFA): Generates few-shot learning examples based on KEA output

- Data Mining Agent (DMA): Extracts experimental conditions from all assay descriptions using the generated examples

This system analyzed 14,401 bioassays to facilitate merging entries from different sources while accounting for critical experimental variables like buffer composition, pH levels, and procedural differences that significantly impact measured properties [10].

Figure 2: Multi-Agent LLM Data Mining System

For assessing dataset compatibility before integration, tools like AssayInspector provide systematic data consistency assessment through [18]:

- Statistical comparison of endpoint distributions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for regression, Chi-square for classification)

- Chemical space analysis using molecular similarity metrics

- Identification of conflicting annotations for shared compounds

- Visualization of dataset intersections and coverage

Emerging Solutions and Comparative Performance

Federated Learning for Expanded Chemical Coverage

Federated learning has emerged as a promising paradigm for addressing data scarcity while preserving intellectual property. This approach enables multiple organizations to collaboratively train models without sharing proprietary data, significantly expanding the effective chemical space coverage.

The MELLODDY project, a large-scale cross-pharma federated learning initiative, demonstrated that federated models consistently outperform single-organization baselines, with benefits scaling with participant diversity [1]. Key findings from federated learning implementations include:

- 40-60% reduction in prediction error for endpoints like human and mouse liver microsomal clearance, solubility, and permeability [1]

- Expanded applicability domains, with improved performance on novel scaffolds not seen in any single organization's data

- Persistent benefits across heterogeneous assay protocols and endpoint coverage

Figure 3: Federated Learning Architecture for ADMET

Quality-Centric Data Generation Frameworks

An alternative approach prioritizes data quality over quantity by leveraging consistently generated proprietary datasets. The Johnson & Johnson solubility study systematically compared models trained on datasets with different quality profiles, finding that [19]:

- With equivalent dataset sizes, high-quality data consistently produced better model performance (RMSE improvements of 0.1-0.2 log units)

- Larger datasets with analytical variability could match the performance of smaller, cleaner datasets, but only when the noise was random rather than systematic

- Systematic bias introduced by amorphous solid forms could not be overcome by increasing dataset size

This highlights the importance of critical data review processes and standardized assay protocols in generating reliable training data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for ADMET Data Management and Modeling

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AssayInspector [18] | Data consistency assessment | Pre-modeling data aggregation | Statistical comparison of distributions, chemical space visualization, conflict detection |

| PharmaBench [10] | Benchmark dataset | Model training and evaluation | 52,482 entries with standardized experimental conditions from 14,401 bioassays |

| RDKit [6] [9] | Cheminformatics processing | Data preprocessing and featurization | Molecular standardization, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation |

| Apheris Federated Platform [1] | Privacy-preserving collaborative learning | Cross-institutional model training | Federated learning infrastructure for proprietary data collaboration |

| TDC [6] | Benchmark resource | Model benchmarking | Curated ADMET datasets with standardized train/test splits |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [18] | Predictive modeling | Property prediction | Platform incorporating multiple ADMET endpoints with gold-standard data |

The comparative analysis of data challenges in ADMET prediction reveals a complex landscape where solutions must address the interconnected issues of quality, standardization, and coverage. The evidence suggests that while expanding dataset size provides diminishing returns, improving data quality and chemical space diversity through approaches like federated learning and advanced data curation offers substantial benefits. Future progress will likely depend on continued development of standardized experimental protocols, wider adoption of data consistency assessment tools prior to modeling, and increased participation in collaborative initiatives that expand the collective chemical space available for model training without compromising proprietary information. As these approaches mature, the field moves closer to developing ADMET models with truly generalizable predictive power across the diverse chemical landscapes encountered in modern drug discovery.

Implementing AI and Classical Models for ADMET Endpoints

Molecular representation serves as the foundational bridge between chemical structures and their biological activities, forming the critical first step in any computational ADMET prediction pipeline. The selection of an appropriate representation method directly determines a model's ability to capture the intricate relationships between molecular structure and key pharmacokinetic and toxicological endpoints. As drug discovery increasingly relies on computational approaches to reduce late-stage attrition rates, understanding the practical trade-offs between different representation strategies has become essential for researchers [11] [21].

The evolution from traditional descriptor-based methods to modern deep learning approaches has significantly expanded the molecular representation landscape. This guide provides a comparative analysis of predominant representation paradigms, supported by experimental data and standardized benchmarking studies, to equip researchers with evidence-based criteria for selecting optimal representations for specific ADMET tasks within drug discovery workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Paradigms

Traditional Representation Methods

Traditional molecular representations rely on explicit, rule-based feature extraction methods derived from chemical and physical properties. These approaches have established strong baselines in ADMET prediction and remain competitive due to their computational efficiency and interpretability [11] [6].

Molecular descriptors quantify physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, hydrophobicity (logP), polar surface area, and topological indices. RDKit provides comprehensive descriptor calculation capabilities, with over 5000 possible descriptors encompassing constitutional, topological, and electronic properties [21]. Molecular fingerprints encode substructural information as binary strings or numerical vectors, with Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) being particularly widely adopted for their ability to represent local atomic environments [11] [6].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional Representation Methods on TDC ADMET Benchmarks

| Representation | AUC Range | Key Strengths | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit Descriptors | 0.68-0.85 | Computational efficiency, interpretability | Solubility, permeability prediction |

| ECFP4 Fingerprints | 0.71-0.88 | Strong baseline, similarity searching | Virtual screening, toxicity classification |

| Molecular ACCess System (MACCS) | 0.65-0.82 | Simplified structure alerts | High-throughput prioritization |

| Combined Descriptors + ECFP | 0.73-0.90 | Complementary information | Multi-task learning settings |

Modern Deep Learning Representations

AI-driven molecular representations employ deep learning techniques to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from data, capturing both local and global molecular features beyond predefined rules [11].

Graph-based representations model molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), particularly Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) as implemented in Chemprop, have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance by learning complex patterns from molecular graphs [22] [6]. Language model-based representations treat molecular sequences (SMILES/SELFIES) as chemical language, adapting Transformer architectures to learn contextualized molecular embeddings [11] [23].

Table 2: Performance of Deep Learning Representations on Standardized ADMET Benchmarks

| Representation | Model Architecture | Average AUC | Notable Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Representation | Chemprop (D-MPNN) | 0.76-0.92 | Metabolism, toxicity endpoints |

| SMILES + Transformer | ChemBERTa | 0.72-0.89 | Scaffold hopping, generalization |

| Multimodal (Graph + SMILES) | MSformer-ADMET | 0.81-0.94 | Overall best performance |

| Fragment-based | MSformer-ADMET | 0.83-0.95 | Interpretability, natural products |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Rigorous benchmarking requires standardized datasets, evaluation metrics, and data splitting strategies to enable fair comparison across representation methods. The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) provides curated ADMET datasets with official train-test splits that facilitate reproducible model comparison [22] [6]. Recent initiatives like PharmaBench have addressed limitations in previous benchmarks by incorporating larger dataset sizes (156,618 raw entries) and better representation of drug-like compounds (molecular weight 300-800 Da) using LLM-powered data extraction from public sources [10].

The standard evaluation protocol involves:

- Data cleaning and standardization: Removal of inorganic salts, extraction of parent compounds from salt forms, tautomer standardization, and SMILES canonicalization [6]

- Data splitting: Scaffold-based splitting to assess generalization to novel chemical scaffolds

- Model training: Extensive hyperparameter optimization with cross-validation

- Performance assessment: Statistical hypothesis testing to distinguish significant performance differences

Multi-Task Learning Experimental Framework

Multi-task learning (MTL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for ADMET prediction, leveraging shared information across related tasks. The QW-MTL framework incorporates quantum chemical descriptors (dipole moment, HOMO-LUMO gap, electron properties, total energy) to enrich molecular representations with electronic structure information [22]. This approach employs a novel exponential task weighting scheme that combines dataset-scale priors with learnable parameters for dynamic loss balancing across tasks [22].

Experimental results demonstrate that MTL systematically outperforms single-task baselines on 12 out of 13 TDC classification benchmarks, with particularly strong improvements for low-resource tasks that benefit from knowledge transfer [22].

Decision Framework for Representation Selection

Task-Specific Representation Recommendations

The optimal molecular representation depends on the specific ADMET endpoint, available data, and computational constraints. Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies:

- Metabolism endpoints (CYP inhibition, clearance): Graph-based representations (D-MPNN) enhanced with quantum chemical descriptors consistently achieve superior performance due to their ability to capture electronic properties relevant to metabolic transformations [22]

- Toxicity endpoints (hERG, hepatotoxicity): Combined representations (MSformer-ADMET) that integrate multiple perspectives demonstrate robust performance across diverse toxicity mechanisms [23]

- Solubility and permeability: Traditional descriptors (RDKit + Morgan fingerprints) remain highly competitive, offering an favorable balance of performance and computational efficiency [6]

- Cross-domain generalization: Fragment-based representations (MSformer-ADMET) show particular strength in scaffold hopping and out-of-distribution prediction [23]

Diagram 1: Molecular Representation Selection Workflow for ADMET Tasks

Practical Implementation Considerations

Beyond pure predictive performance, several practical factors influence representation selection in real-world drug discovery settings:

- Computational requirements: Traditional fingerprints enable rapid screening of ultra-large libraries (>10^6 compounds), while graph neural networks require significantly more resources [6]

- Interpretability needs: Fragment-based representations (MSformer-ADMET) provide inherent interpretability through attention mechanisms that highlight structural fragments contributing to predictions [23]

- Data integration capabilities: Federated learning approaches enable training across distributed proprietary datasets without centralizing sensitive data, systematically expanding chemical coverage [1]

- Regulatory compliance: Models intended for regulatory submissions must balance performance with interpretability and methodological transparency [24]

Table 3: Essential Resources for ADMET Representation Research

| Resource | Type | Key Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Benchmark Datasets | Standardized ADMET datasets with train-test splits | Model evaluation and comparison |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation | Traditional representation baseline |

| Chemprop | Deep Learning Library | Message Passing Neural Network implementation | Graph-based representation |

| MSformer-ADMET | Specialized Framework | Fragment-based molecular representation | Interpretable multi-task prediction |

| PharmaBench | Enhanced Benchmark | Expanded ADMET datasets with experimental conditions | Real-world model validation |

| QM Descriptors | Quantum Chemical Features | Electronic structure properties (HOMO-LUMO, dipole moment) | Metabolism and reactivity prediction |

The molecular representation landscape for ADMET prediction has evolved from simple descriptors to sophisticated multimodal learning approaches. Evidence from rigorous benchmarking indicates that no single representation dominates across all tasks and contexts. Rather, the optimal choice depends on the specific ADMET endpoint, data characteristics, and practical constraints.

Hybrid approaches that combine complementary representation strategies generally achieve superior performance, with MSformer-ADMET's fragment-based paradigm and QW-MTL's quantum-enhanced multi-task learning representing the current state-of-the-art [22] [23]. Emerging trends include federated learning to expand chemical diversity [1], large language models for automated data curation [10], and increased emphasis on interpretability to bridge the gap between prediction and mechanistic understanding.

As the field advances, representation selection will remain a critical determinant of success in computational ADMET prediction, requiring researchers to balance empirical evidence with practical implementation considerations within their specific drug discovery context.

The accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical challenge in modern drug discovery. With approximately 40-45% of clinical failures still attributed to unfavorable ADMET characteristics, the development of robust computational models has become indispensable for prioritizing viable drug candidates early in the development pipeline [1]. The field has witnessed a paradigm shift from traditional descriptor-based machine learning to sophisticated deep learning architectures capable of extracting nuanced patterns from complex molecular data.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of three predominant architectural paradigms in ADMET prediction: the classical Random Forest algorithm, geometrically-aware Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and sequence-processing Transformers. Each architecture brings distinct advantages and limitations to the complex task of molecular property prediction, with performance characteristics that vary significantly across different ADMET endpoints and data regimes. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and experimental findings, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with actionable insights for selecting appropriate modeling strategies based on their specific project requirements, data availability, and computational resources.

Random Forests: The Established Performer

Random Forests (RF) represent an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode of their predictions for classification or mean prediction for regression tasks. In ADMET prediction, RF models typically operate on fixed molecular representations such as fingerprints or descriptors.

Key Characteristics:

- Input Representation: Utilizes pre-computed molecular features including RDKit descriptors, Morgan fingerprints, and other ligand-based representations [6]

- Interpretability: Medium - provides feature importance metrics but lacks atomic-level interpretability

- Data Efficiency: Effective with small to medium-sized datasets (hundreds to thousands of compounds)

- Computational Demand: Low to moderate, suitable for standard computational resources

Recent benchmarking studies indicate that RF maintains competitive performance against more complex deep learning architectures, particularly on smaller datasets. The algorithm's robustness against overfitting and ability to handle diverse feature types make it a reliable baseline for ADMET modeling [6].

Graph Neural Networks: Structural Specialists

GNNs operate directly on molecular graph structures where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges. Through message-passing mechanisms, GNNs learn to aggregate information from local atomic neighborhoods to derive meaningful molecular representations.

Key Variants:

- GCN (Graph Convolutional Network): Applies convolution operations to graph nodes, aggregating feature information from neighbors [25]

- GAT (Graph Attention Network): Incorporates attention mechanisms to weight neighbor importance during feature aggregation [25]

- MPNN (Message Passing Neural Network): Employs an iterative message-passing framework where nodes exchange information with neighbors [25] [26]

- GIN (Graph Isomorphism Network): Uses a sum aggregator to maximize discriminative power for graph structures [25]

Key Characteristics:

- Input Representation: Native molecular graphs with atom and bond features

- Interpretability: Medium to high - attention mechanisms can highlight structurally important regions

- Data Efficiency: Requires moderate to large datasets (thousands of compounds) for optimal performance

- Computational Demand: Moderate to high, especially for deep architectures

Advanced GNN implementations like MoleculeFormer have demonstrated robust performance across diverse ADMET tasks by incorporating multi-scale feature integration, 3D structural information, and rotational equivariance constraints [27].

Transformers: Sequence Modeling Powerhouses

Originally developed for natural language processing, Transformers have been adapted for molecular representation by treating SMILES strings as sequential data. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to capture long-range dependencies and global molecular context.

Key Characteristics:

- Input Representation: SMILES strings or hybrid tokenization schemes [26]

- Interpretability: Medium - attention weights can highlight important sequence segments

- Data Efficiency: Benefits from pre-training on large unlabeled molecular datasets

- Computational Demand: High, especially for pre-training phases

Innovative approaches like hybrid fragment-SMILES tokenization have enhanced Transformer performance by incorporating chemically meaningful substructures alongside character-level tokens [26]. The MTL-BERT model exemplifies how transfer learning and multi-task training can boost ADMET prediction accuracy [26].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comparative performance of RF, GNNs, and Transformers across ADMET tasks

| ADMET Task | Random Forest | GNN (MPNN/D-MPNN) | Transformer | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | MAE: ~0.7-1.0 log units [6] | Competitive with RF [6] | Varies by implementation | RF and GNNs often show comparable performance [6] |

| BBB Penetration | AUC: ~0.85 [25] | AUC: ~0.85-0.90 [25] | Similar to GNNs | GNNs may capture structural determinants more effectively |

| Metabolic Stability | RMSE: ~0.6-0.8 [6] | RMSE: ~0.5-0.7 [6] | Dependent on pre-training | GNNs show advantages for structure-aware properties |

| Toxicity (Tox21) | AUC: ~0.80-0.85 [25] | AUC: ~0.82-0.87 [25] | AUC: ~0.83-0.88 [26] | Transformers benefit from multi-task learning |

Table 2: Architectural strengths and limitations in ADMET contexts

| Architecture | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Robust on small datasets, fast training, handles mixed features | Limited extrapolation, cannot learn novel representations | Initial screening, baseline models, resource-constrained environments |

| GNN | Native structural understanding, strong generalization on scaffolds | Requires careful hyperparameter tuning, moderate data requirements | Structure-activity relationships, lead optimization phases |

| Transformer | Transfer learning capability, captures complex patterns | Data-hungry, computationally intensive, SMILES dependencies | Large-scale screening, integration with bioactivity data |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust evaluation of ADMET prediction models requires standardized protocols to ensure fair comparisons across architectures. Recent benchmarking initiatives have established several key methodological considerations:

Data Curation and Splitting:

- Scaffold Splitting: Compounds are divided based on molecular scaffolds to assess generalization to novel chemotypes [6] [10]

- Temporal Splitting: Evaluation based on time of compound synthesis to simulate real-world discovery settings [6]

- Data Cleaning: Standardization of SMILES representations, removal of inorganic salts, and handling of tautomers [6]

Feature Representation Strategies:

- Classical Descriptors: RDKit descriptors, topological indices, and physicochemical properties [6]

- Fingerprints: Morgan fingerprints, ECFP, FCFP, and structural keys [6] [27]

- Learned Representations: Atom-level embeddings from GNNs or token embeddings from Transformers [27] [26]

Evaluation Metrics:

- Regression Tasks: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R² [6] [25]

- Classification Tasks: ROC-AUC, Precision-Recall AUC, Balanced Accuracy [6] [25]

- Statistical Validation: Cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing to confirm performance differences [6]

Critical Experimental Findings

Recent rigorous benchmarking reveals nuanced performance patterns across architectural paradigms:

Representation Impact: The choice of molecular representation frequently exerts greater influence on performance than the specific model architecture, particularly for classical machine learning approaches [6]. Systematic feature selection and combination strategies can yield significant improvements over arbitrary representation choices.

Data Quality Considerations: Public ADMET datasets often contain inconsistencies including duplicate measurements with conflicting values and ambiguous binary labels [6]. Implementation of comprehensive data cleaning pipelines is essential for reliable model assessment.

Cross-Dataset Generalization: Models trained on one data source frequently experience performance degradation when evaluated on external datasets measuring the same property [6]. This highlights the critical importance of assay conditions and experimental protocols in ADMET prediction.

Federated Learning Benefits: Cross-pharma federated learning initiatives have demonstrated that expanding chemical space coverage through privacy-preserving multi-institutional collaboration systematically improves model performance and applicability domains [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key computational tools and resources for ADMET model development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Architecture Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, SMILES processing | All architectures (feature generation) |

| DeepChem | Deep Learning Library | End-to-end molecular machine learning workflows | GNNs, Transformers, RF |

| Chemprop | Specialized Package | Message Passing Neural Networks for molecular property prediction | GNNs (D-MPNN) |

| TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons) | Data Resource | Curated ADMET benchmarks and evaluation tools | All architectures |

| PharmaBench | Benchmark Dataset | Large-scale, standardized ADMET property data | All architectures |

| MTL-BERT | Pre-trained Model | Transformer-based multi-task learning for ADMET | Transformers |

| kMoL | Federated Learning Library | Privacy-preserving collaborative model training | All architectures |

The comparative analysis of Random Forests, GNNs, and Transformers for ADMET prediction reveals a complex performance landscape where no single architecture dominates across all scenarios. Each approach brings distinctive strengths that align with specific drug discovery contexts:

Random Forests remain surprisingly competitive, particularly in resource-constrained environments or when working with smaller datasets (hundreds to low thousands of compounds). Their robustness, interpretability, and computational efficiency make them ideal for initial screening campaigns and as performance baselines against which to benchmark more complex approaches.

Graph Neural Networks excel in scenarios requiring explicit structural reasoning, particularly when molecular topology or stereochemistry significantly influences the ADMET property being modeled. Their native ability to operate on molecular graphs without predefined feature engineering makes them particularly valuable for lead optimization stages where understanding structure-property relationships is crucial.