Molecular Docking for Protein-Ligand Interactions: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular docking, a pivotal computational technique in structure-based drug design.

Molecular Docking for Protein-Ligand Interactions: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular docking, a pivotal computational technique in structure-based drug design. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of protein-ligand interactions and key docking concepts. It delivers practical, step-by-step methodologies for performing docking simulations, highlights common pitfalls and strategies for optimization to ensure reproducible results, and explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of tools. By synthesizing information across these four core intents, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to effectively apply molecular docking in virtual screening and lead optimization, accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

The Essential Guide to Protein-Ligand Interactions and Docking Fundamentals

Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the preferred orientation and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (usually a protein) [1] [2]. By simulating this "computational handshake," docking aims to predict the binding affinity and analyze the molecular interactions that stabilize the complex, thereby playing a critical role in modern structure-based drug design (SBDD) [2] [3]. Its applications span from virtual screening of large chemical libraries to hit identification and optimization, greatly enhancing the efficiency and reducing the cost of early drug discovery [3] [4].

The Molecular Docking Workflow

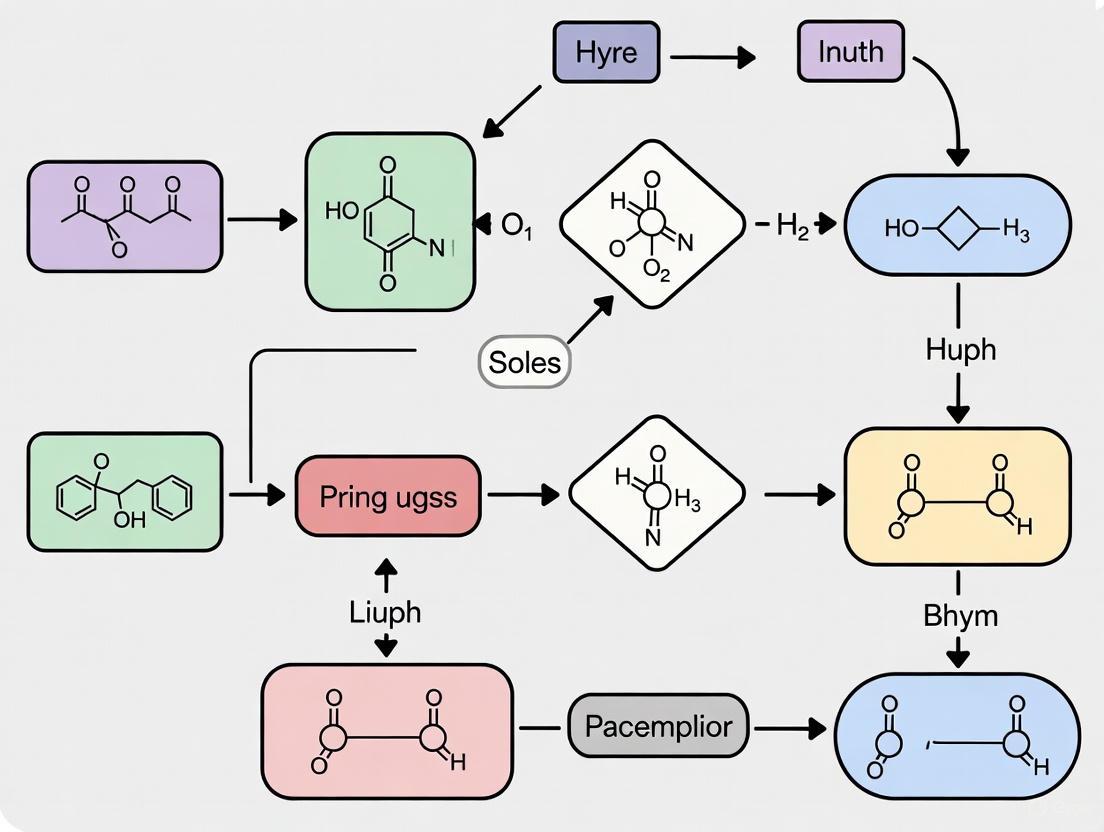

The general process of molecular docking can be broken down into several key stages, from target preparation to result analysis. The following diagram outlines this workflow, highlighting the cyclical nature of structure-based drug design.

Structure Preparation

The process begins with obtaining the 3D structures of the target protein and the ligand. Protein structures are typically sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), while ligand structures can be retrieved from databases like ZINC or PubChem [1] [2]. Critical preparation steps include:

- Adding Hydrogen Atoms: Experimental structures often lack hydrogens, which are essential for modeling hydrogen bonds.

- Assigning Protonation States: The protonation states of amino acid residues and the ligand at physiological pH are evaluated using tools like PropKa or H++ [1].

- Removing Redundant Elements: Crystallographic water molecules and cofactors are often removed unless they are known to be crucial for binding.

When an experimental protein structure is unavailable, computational models generated by tools like AlphaFold2 (AF2) can serve as suitable starting points, performing comparably to native structures in docking benchmarks for protein-protein interfaces [5].

Docking Execution

The core of the procedure involves the conformational search and scoring of the ligand within the protein's binding site.

Conformational Search Algorithms

Search algorithms explore the ligand's possible orientations and conformations within the binding site. They are broadly classified as follows [1] [2]:

- Systematic Search: Explores each torsional degree of freedom incrementally. To avoid combinatorial explosion, methods like incremental construction (used by FlexX) break the ligand into fragments and rebuild it inside the binding pocket [2].

- Stochastic Search: Uses random changes to the ligand's degrees of freedom. This includes Genetic Algorithms (used by GOLD and AutoDock) and Monte Carlo methods, which help avoid local energy minima [2].

- Deterministic Search: The new state is determined by the previous one (e.g., energy minimization), but this can trap poses in local minima [1].

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions estimate the binding affinity of each generated pose. They can be classified as [1] [2]:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energies based on molecular mechanics.

- Empirical: Use weighted parameters derived from experimental data.

- Knowledge-Based: Derive potentials from statistical analyses of known protein-ligand complexes.

Post-Docking Analysis

After docking, the results require careful analysis. The top-ranked poses are inspected for key molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions). Tools like InVADo provide interactive visual analysis of large docking datasets, enriching results with post-docking analysis of protein-ligand interactions [6]. It is crucial to validate the docking protocol, for instance, by redocking a known native ligand to check if the software can reproduce the experimental binding mode [4].

Key Methodologies and Benchmarking Insights

Performance of AlphaFold2 Models in Docking

Recent benchmarking studies evaluating AF2 models for docking at protein-protein interfaces (PPIs) have yielded critical insights [5]. The table below summarizes the key comparative findings between AF2 models and experimentally solved structures.

Table 1: Benchmarking AF2 Models vs. Experimental Structures in PPI-Targeted Docking

| Aspect | Performance in AF2 Models (AFnat) | Performance in Experimental (PDB) Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Docking Performance | Comparable to native structures [5] | Standard for comparison |

| Local vs. Blind Docking | Local docking strategies outperformed blind docking [5] | Local docking strategies outperformed blind docking [5] |

| Top-Performing Protocols | TankBind_local and Glide performed best [5] | TankBind_local and Glide performed best [5] |

| Impact of Structural Refinement | MD simulations and AlphaFlow ensembles improved outcomes in selected cases [5] | MD simulations and AlphaFlow ensembles improved outcomes in selected cases [5] |

| Primary Limiting Factor | Performance constrained by scoring function limitations, not model quality [5] | Performance constrained by scoring function limitations [5] |

Addressing Flexibility with Ensemble Docking

Protein flexibility is a major challenge. A common strategy to address this is ensemble docking, where multiple protein conformations are used. These ensembles can be generated from:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Refining AF2 or PDB structures with all-atom MD simulations (e.g., 500 ns) can improve virtual screening performance [5].

- Experimental Structures: Using multiple PDB structures of the same target from apo, holo, or ligand-bound states.

- Computational Models: Using algorithms like AlphaFlow to generate sequence-conditioned conformations [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and tools that form the backbone of a molecular docking pipeline.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Docking

| Category / Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | ||

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database of experimental 3D macromolecular structures [1] [3] | Primary source for target protein structures for docking [1] [3]. |

| ZINC & PubChem | Databases of commercially available and small-molecule compounds [1] [3] | Source of 2D/3D ligand structures for virtual screening [1] [3]. |

| Docking Software | ||

| AutoDock Vina | Docking program with stochastic search and empirical scoring [1] | Known for speed and accuracy; widely used for virtual screening [1]. |

| Glide | Docking program with systematic search and empirical scoring [5] [2] | Identified as a top performer in PPI docking benchmarks [5]. |

| GOLD | Docking program using a genetic algorithm search [1] [2] | Applies multiple scoring functions (GoldScore, ChemPLP) [1]. |

| Analysis & Visualization | ||

| InVADo | Interactive visual analysis tool for docking data [6] | Filters, clusters, and enriches docking results with interaction analysis for decision-making [6]. |

| PyMOL | Open-source molecular graphics tool [3] | Used for visualizing protein-ligand complexes and binding poses. |

| Structure Prediction & Refinement | ||

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction algorithm [5] | Generates high-accuracy protein models for docking when experimental structures are unavailable [5]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulation technique for sampling molecular motion [5] | Refines static structures and generates conformational ensembles for more robust docking [5]. |

Advanced Considerations and Best Practices

Controls and Validation

As with any experimental technique, controls are essential for reliable docking outcomes [4]. Before undertaking a large-scale screen, it is critical to:

- Reproduce a Known Pose: Redock a co-crystallized ligand to validate that your protocol can accurately reproduce the experimental binding mode.

- Enrichment Studies: Perform a retrospective virtual screening to check if the method can prioritize known active compounds over decoys.

Awareness of Limitations

Despite its utility, molecular docking has inherent limitations that researchers must acknowledge [7]:

- Scoring Function Inaccuracy: Scoring functions are approximations and often struggle to predict binding affinities accurately due to incomplete treatment of effects like solvation and entropy [5] [7].

- Limited Protein Flexibility: Although ensemble docking helps, most protocols still treat the protein as rigid during the docking simulation itself, which can be a major simplification [7].

- Membrane Environment Neglect: Docking into lipophilic or membrane-facing pockets is challenging, as the models typically do not explicitly include the lipid bilayer [7].

In conclusion, molecular docking is a powerful, accessible, and indispensable tool in computational drug discovery. Its successful application relies on a thoughtful workflow, careful preparation of structures, an understanding of the underlying algorithms, and a critical assessment of results complemented by experimental validation. The integration of new technologies like AlphaFold2 and machine learning continues to push the boundaries of what is possible, making docking an ever more valuable handshake in the design of new therapeutics.

{article title} Key Physicochemical Principles Governing Protein-Ligand Binding {/article title}

{article content}

Protein-ligand interactions are fundamental to biological processes and represent a primary focus in structure-based drug design [8] [9]. Molecular recognition, characterized by high specificity and affinity, enables proteins to perform a vast array of cellular functions, including catalysis, signal transduction, and regulatory processes [8]. The formation of a specific protein-ligand complex is governed by a combination of physicochemical principles, such as binding kinetics, thermodynamics, and molecular forces [8] [10]. A detailed understanding of these principles is central to predicting binding behavior, optimizing lead compounds, and facilitating the discovery and development of new therapeutics [8] [11]. This application note synthesizes the key principles and provides detailed protocols for their investigation within the context of molecular docking research.

Foundational Physicochemical Principles

The association between a protein (P) and a ligand (L) to form a complex (PL) is a dynamic equilibrium process, described by the equation: P + L ⇌ PL [8]. The kinetics of this process are defined by the association rate constant (kon) and the dissociation rate constant (koff). At equilibrium, the ratio of these constants yields the binding constant (Kb = kon / koff) or its inverse, the dissociation constant (Kd) [8]. A high Kb (low Kd) indicates strong binding affinity [8] [9].

From a thermodynamic perspective, the spontaneity and stability of the binding event are determined by the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), which is related to the binding constant by the equation: ΔG° = -RT lnK_b [8]. A negative ΔG signifies a favorable binding reaction. This free energy change can be deconstructed into enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components through the fundamental relationship: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [8] [12]. Enthalpy changes arise from the formation and breaking of non-covalent interactions, while entropy changes relate to alterations in the disorder of the system, such as the release of water molecules from the binding interface [8] [11].

Table 1: Key Intermolecular Forces in Protein-Ligand Binding

| Force Type | Strength Range (kcal/mol) | Characteristics | Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding [9] | 2 - 10 | Directional; occurs between electronegative atoms and hydrogen. | Provides specificity and contributes significantly to binding affinity. |

| Electrostatic Interactions [9] | Varies with distance | Includes ion-ion and ion-dipole attractions; governed by Coulomb's law. | Long-range forces that can guide ligands to the binding site. |

| Hydrophobic Effect [9] | Not applicable per bond | Driven by the entropy gain of released water molecules. | Major driving force for burying non-polar surfaces. |

| Van der Waals Forces [9] | < 1 (per atom pair) | Weak, short-range interactions between induced dipoles. | Collectively contribute to stability when surfaces are complementary. |

Several conceptual models describe the mechanism of molecular recognition. The "Lock-and-Key" model, proposed by Emil Fischer, posits a rigid, pre-formed binding site that complements the ligand's shape [8] [9]. Daniel Koshland's "Induced Fit" model accounts for protein flexibility, suggesting the binding site reshapes to accommodate the ligand [8] [11] [9]. The "Conformational Selection" model expands on this by proposing that proteins exist in an ensemble of conformations, and the ligand selectively stabilizes a pre-existing, complementary state [8] [9]. Modern docking approaches must consider these models, particularly the implications of protein flexibility.

{caption} Fig 1. Protein-ligand binding model evolution. {/caption}

Experimental Methods for Investigating Binding

Experimental techniques provide critical data for validating computational predictions and understanding binding mechanisms. The following protocols outline key methodologies.

Protocol: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Principle: ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event, allowing for the direct determination of all thermodynamic parameters (K_b, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, and stoichiometry, n) in a single experiment [8].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely degas the protein and ligand solutions to prevent air bubbles in the calorimeter. Use an identical buffer for both to avoid heats of dilution.

- Instrument Setup: Load the protein solution into the sample cell (typically 200-300 µL) and the ligand solution into the syringe. Set the stirring speed to a constant rate (e.g., 300-400 rpm).

- Titration Program: Program the instrument to perform a series of sequential injections of the ligand into the protein solution. A typical experiment may involve 15-25 injections of 2-10 µL each.

- Data Collection: The instrument records the power (µcal/sec) required to maintain a constant temperature difference between the sample and reference cells after each injection.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the heat peaks from each injection. Plot the normalized heat per mole of injectant against the molar ratio of ligand to protein. Fit the resulting isotherm to a suitable binding model (e.g., one-set-of-sites) to extract the thermodynamic parameters.

Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Principle: SPR measures real-time biomolecular interactions by detecting changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface, providing kinetic data (kon and koff) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D) [8] [9].

Procedure:

- Ligand Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the protein (ligand) onto a dextran-coated gold sensor chip via amine coupling or other suitable chemistry.

- System Equilibration: Pass a continuous flow of running buffer over the sensor surface to establish a stable baseline.

- Analyte Binding: Inject the small molecule analyte at a range of concentrations over the immobilized protein surface and a reference flow cell.

- Real-Time Monitoring: The SPR signal (Response Units, RU) is monitored throughout the association (injection) and dissociation (buffer flow) phases.

- Kinetic Analysis: Subtract the reference cell signal. Fit the resulting sensorgrams globally to a kinetic model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding) to determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants. The KD is calculated as koff / k_on.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Techniques

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Sample Consumption | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [8] | K_b, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, n | High (mg quantities) | Direct measurement of full thermodynamics; no labeling. | Requires large amounts of sample. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [8] [9] | kon, koff, K_D | Low (µg of immobilized target) | Provides real-time kinetic data; low analyte consumption. | Requires immobilization, which may affect activity. |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [8] | K_D (indirectly) | Low | Homogeneous assay; suitable for high-throughput screening. | Requires a fluorescently labeled ligand or tracer. |

| X-ray Crystallography [9] | 3D Atomic Structure | Medium | Provides atomic-resolution structure of the complex. | Requires high-quality crystals; static snapshot. |

Computational Protocols for Molecular Docking

Molecular docking predicts the optimal binding pose and affinity of a ligand within a protein's binding site. It is a cornerstone of structure-based drug design [11] [12]. The general workflow involves target preparation, ligand preparation, docking execution, and post-docking analysis.

{caption} Fig 2. Standard molecular docking workflow. {/caption}

Protocol: Structure Preparation and Pre-docking

A. Protein Target Preparation:

- Source the Structure: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate one using a predictive tool like AlphaFold2 [5] [12].

- Pre-process the Structure: Remove water molecules and non-essential cofactors, though structured waters mediating key interactions may be retained. Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states to ionizable residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) at the desired pH.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a brief energy minimization to relieve steric clashes introduced during the hydrogen addition process.

B. Ligand Preparation:

- Generate 3D Conformers: If starting from a 2D structure, generate a 3D model. Identify and define rotatable bonds.

- Assign Charges and Protonation: Assign Gasteiger or other suitable partial atomic charges. Generate probable protonation states and tautomers at physiological pH.

C. Define the Binding Site:

- Identify the Cavity: Use cavity detection algorithms (e.g., in AutoDock, MOE) to map potential binding pockets [11].

- Create a Grid or Map: Define a 3D grid box that encompasses the entire binding site of interest. The grid should be large enough to allow the ligand to rotate and translate freely.

Protocol: Docking Execution and Pose Refinement

A. Conformational Sampling: Docking programs use various search algorithms to explore the ligand's conformational space within the binding site [12].

- Systematic Search: Rotates all rotatable bonds by fixed intervals (e.g., Glide, FRED).

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): Uses principles of natural selection (mutation, crossover) to evolve populations of ligand poses (e.g., AutoDock, GOLD).

- Monte Carlo (MC): Makes random changes to the ligand's position and conformation, accepting or rejecting based on a probabilistic criterion (e.g., used in Glide).

B. Scoring and Pose Ranking: Scoring functions estimate the binding affinity of each generated pose [12] [7]. They fall into three main categories:

- Force-Field Based: Calculate energy using molecular mechanics terms (van der Waals, electrostatics).

- Empirical: Use weighted sums of physicochemical terms (H-bonds, hydrophobics) fitted to experimental data.

- Knowledge-Based: Derive potentials from statistical analyses of atom-atom distances in known protein-ligand complexes.

C. Post-docking Analysis and Refinement:

- Cluster Poses: Cluster top-ranked poses based on root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to identify consensus binding modes.

- Visual Inspection: Manually inspect the best poses for key interactions (H-bonds, pi-stacking, hydrophobic contacts).

- Refinement with Molecular Dynamics (MD): Use short MD simulations to refine the docked pose, incorporate full protein flexibility, and assess the stability of the predicted complex [5] [12]. This step can help account for "induced fit" effects.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein-Ligand Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Protein Target | The macromolecule for binding studies; requires high purity and maintained activity. | Recombinantly expressed proteins; consider tags (e.g., His-tag) for purification. |

| Characterized Ligand Library | A collection of small molecules for screening against the target. | Commercially available libraries (e.g., LOPAC, Mcule); in-house compound collections. |

| ITC Instrumentation | To directly measure the thermodynamics of binding in solution. | Malvern MicroCal PEAQ-ITC; requires careful buffer matching. |

| SPR System | To measure binding kinetics in real-time without labels. | Cytiva Biacore; requires chip surface and immobilization chemistry. |

| Crystallization Kits | To grow crystals of the protein-ligand complex for structural validation. | Sparse matrix screens from Hampton Research or Qiagen. |

| Molecular Docking Software | To computationally predict binding modes and affinities. | AutoDock, Glide, GOLD; consider algorithm and scoring function. |

| AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Database | Source of high-quality predicted protein structures when experimental ones are unavailable. | Models can perform comparably to experimental structures in docking [5]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | To refine docked poses and simulate protein-ligand dynamics. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD; computationally intensive but insightful. |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite advancements, accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding remains challenging. Key limitations include the treatment of protein flexibility, as receptors are often treated as rigid bodies in docking, ignoring induced fit and allosteric effects [11] [7]. Furthermore, scoring functions often struggle to accurately predict binding affinities due to approximations in modeling solvation effects, entropy, and polarization [11] [12] [7]. The role of water molecules is also critical; while displacement can drive binding, structured waters that mediate interactions are difficult to model accurately [11].

Future progress is likely to come from integrated approaches. The use of structural ensembles from molecular dynamics or generative models (e.g., AlphaFlow) can better represent protein flexibility, though predicting the most effective conformation for docking remains non-trivial [5]. The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning is leading to more generalizable scoring functions and improved search algorithms, helping to mitigate issues of over-fitting and data limitation [12]. Finally, a consensus approach that combines multiple docking programs, scoring functions, and subsequent refinement with MD simulations is often necessary to generate robust, testable hypotheses for drug discovery [12] [7].

{/article content}

Molecular docking, the computational prediction of how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a protein target, has become an indispensable tool in structural biology and drug discovery. By modeling these interactions at an atomic level, docking helps elucidate fundamental biochemical processes and plays a critical role in rational drug design [13]. The field has evolved from simple rigid-body approximations based on steric complementarity to sophisticated algorithms that account for molecular flexibility and complex energy landscapes [14]. This evolution has been driven by a deeper understanding of protein interactions, growing computational resources, and the increasing availability of protein structures. Docking methodologies now enable researchers to predict binding conformations (poses) and estimate binding affinities, providing crucial insights for virtual screening and lead optimization in pharmaceutical development [15] [13]. This article traces the historical development of docking principles, provides quantitative performance comparisons of modern algorithms, and offers detailed protocols for their application in protein-ligand interaction research.

Historical Foundations of Docking

The Early Era: Rigid-Body Docking and Shape Complementarity

The conceptual foundations of molecular docking were laid in the 1970s with the earliest approaches focusing on protein interactions with small ligands at predetermined binding sites [14]. These pioneering methods were remarkably sophisticated, occasionally attempting to model flexibility in both ligand and receptor—a challenge that remains difficult even with modern computational resources. The first protein-protein docking approaches soon followed, implementing global search methodologies in a rigid-body approximation [14]. These early methods operated on the lock-and-key hypothesis proposed by Fischer, where both interaction partners were treated as rigid entities, and binding affinity was presumed proportional to their geometric fit [15] [13].

A significant transformation occurred in the early 1990s with the introduction of algorithms based on Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) correlation techniques [14]. This approach, developed by an interdisciplinary team of scientists, enabled computationally feasible exhaustive search of the full six-dimensional translational and rotational docking space by discretizing the search area. The FFT method rapidly became arguably the most popular protein docking algorithm due to its comprehensive sampling capability [14]. This period also saw the adoption of other computer science-inspired sampling techniques, including Monte Carlo simulations and genetic algorithms, which provided alternative strategies for navigating the complex conformational space of interacting molecules [16] [13].

The Paradigm Shift: Incorporating Molecular Flexibility

The recognition that both ligands and receptors undergo conformational changes upon binding led to a critical evolution in docking methodology. The rigid-body assumption gave way to induced-fit theory, which acknowledged that binding sites often reshape during interactions [13]. This paradigm shift necessitated the development of algorithms that could accommodate molecular flexibility.

Initial efforts focused primarily on ligand flexibility, with receptor binding sites remaining largely rigid—an approach that remains popular due to computational constraints [13]. Techniques such as incremental construction (breaking ligands into fragments and rebuilding them within the binding site) and conformational ensembles (docking multiple pre-generated ligand conformations) emerged as effective strategies [13]. More recently, the field has increasingly addressed the challenge of receptor flexibility, particularly through methods that model side-chain movements and, in more advanced implementations, backbone flexibility [17] [14]. Specialized algorithms like AutoDockFR and AutoDockCrankPep were developed to handle these complex flexible systems, representing the current frontier in docking methodology [17].

Table 1: Evolution of Molecular Docking Approaches

| Time Period | Dominant Paradigm | Key Methodological Advances | Representative Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1980s | Rigid-body Docking | Lock-and-key theory; Geometric complementarity | Early protein-ligand docking algorithms [14] |

| 1990s | FFT-Based Global Search | Exhaustive 6D space sampling; Shape and electrostatic complementarity | FFT-based docking algorithms [14] |

| 2000s | Flexible Ligand Docking | Incremental construction; Stochastic algorithms; Scoring function refinement | AutoDock, GOLD, FlexX [15] [13] |

| 2010s-Present | Limited Receptor Flexibility & Peptide Docking | Side-chain flexibility; Coarse-grained modeling; Hybrid approaches | AutoDock Vina, FRODOCK, HADDOCK, pepATTRACT [17] [18] |

Quantitative Benchmarking of Modern Docking Software

The performance of docking programs is typically assessed using key metrics such as ligand root-mean-square deviation (L-RMSD) between predicted and experimental poses, fraction of native contacts (FNAT), and interface RMSD (I-RMSD). These parameters, established by the Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions (CAPRI) community, provide standardized evaluation criteria [18].

Performance in Protein-Peptide Docking

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated six docking methods on 133 protein-peptide complexes with peptide lengths between 9-15 residues [18]. The results demonstrated varying performance across software packages:

Table 2: Performance of Docking Software in Protein-Peptide Docking (Blind Docking)

| Software | Search Algorithm | Scoring Function Components | Average L-RMSD (Å) - Top Pose | Average L-RMSD (Å) - Best Pose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRODOCK 2.0 | Rigid-body, FFT-based | Knowledge-based potential, spherical harmonics | 12.46 | 3.72 |

| ZDOCK 3.0.2 | Rigid-body, FFT-based | Shape complementarity, desolvation, electrostatics | 13.85 | 4.21 |

| Hex 8.0.0 | Rigid-body, Spherical Polar Fourier | Electrostatics, desolvation | 15.92 | 5.38 |

| ATTRACT | Flexible, randomized search | Lennard-Jones potential, electrostatic energy | 16.34 | 5.67 |

| pepATTRACT | Flexible, coarse-grained global search | Knowledge-based potential | 17.28 | 6.02 |

| PatchDock 1.0 | Rigid-body, geometry-based | Geometry fit, atomic desolvation energy | 18.15 | 6.84 |

The study revealed that while FRODOCK achieved the best performance in blind docking scenarios, ZDOCK excelled in re-docking experiments where binding sites were known [18]. A critical finding was the significant improvement in accuracy when considering the best-generated pose rather than the top-ranked pose, highlighting limitations in current scoring functions for pose ranking [18].

Performance in Small Molecule Docking

For small molecule docking, programs have been calibrated and validated against extensive datasets of protein-ligand complexes. The accuracy is typically measured by the RMSD of heavy atoms between predicted and experimental binding poses:

Table 3: Performance of Small Molecule Docking Software

| Software | Sampling Method | Scoring Function | Average Heavy Atom RMSD (Å) | Pose Prediction Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Monte Carlo | Empirical, knowledge-based | 1.5-2.0 | High [15] |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm | Empirical, force field-based | 1.5-2.0 | ~90.0% [15] |

| Glide (XP) | Systematic search | Empirical | 1.5-2.0 | ~90.0% [15] |

| AutoDock | Genetic Algorithm | Empirical free energy | 1.5-2.5 | Moderate [15] |

| LeDock | Monte Carlo | Force field-based | 1.5-2.0 | High for pose prediction [15] |

These programs demonstrate robust performance for rigid receptor docking, with backbone flexibility remaining a significant challenge [15]. The selection of optimal docking box size has been identified as a critical parameter, with research indicating that a box size approximately 2.9 times the ligand's radius of gyration maximizes pose prediction accuracy in AutoDock Vina [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Protein-Ligand Docking with AutoDock Vina

This protocol provides a methodology for predicting the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule ligand to a protein target using AutoDock Vina, suitable for virtual screening applications [17] [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Molecular Docking

| Reagent/Software | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure File | PDB format, hydrogen atoms added | Provides the receptor structure for docking |

| Ligand Structure File | MOL2 or SDF format, 3D coordinates | The small molecule to be docked |

| AutoDock Tools | MGLTools package | Prepares receptor and ligand PDBQT files |

| AutoDock Vina | Version 1.2.0 or newer | Performs the docking simulation |

| Box Size Calculator | Custom script [19] | Determines optimal search space dimensions |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling.

- Remove water molecules and heteroatoms unless critical for binding.

- Add hydrogen atoms and calculate partial charges using AutoDock Tools.

- Save the prepared structure in PDBQT format.

Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the ligand from databases like PubChem or generate it using chemical modeling software.

- Assign proper bond orders and add hydrogen atoms.

- Minimize the ligand structure using molecular mechanics to relieve steric clashes.

- Convert the ligand to PDBQT format using AutoDock Tools.

Grid Box Configuration:

- Identify the binding site coordinates from experimental data or binding site prediction tools like AutoSite [17].

- Calculate the optimal box size using the formula:

Box Size = 2.857 × Radius of Gyration (Rg) of ligand[19]. - Center the grid box on the binding site coordinates with dimensions determined in the previous step.

Docking Execution:

- Create a configuration file specifying receptor, ligand, search space, and exhaustiveness parameters.

- Run AutoDock Vina from the command line:

vina --config config.txt --log log.txt. - For virtual screening, automate this process for multiple ligands using shell or Python scripts.

Result Analysis:

- Examine the generated poses in molecular visualization software like PyMOL or Chimera.

- Evaluate binding modes based on complementary interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, electrostatic complementarity).

- Select top poses for further analysis or experimental validation.

Diagram 1: Vina Docking Workflow (76 characters)

Protocol 2: Flexible Protein-Peptide Docking with FRODOCK

This protocol describes the application of FRODOCK for protein-peptide docking, which is particularly challenging due to peptide flexibility [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Specialized Materials for Protein-Peptide Docking

| Reagent/Software | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Unbound form, solvent molecules removed | The receptor for peptide docking |

| Peptide Structure | Linear or cyclic peptide, 5-15 residues | The flexible peptide ligand |

- FRODOCK 2.0

- Web server or standalone version

- Performs rigid-body docking using FFT with knowledge-based potentials

- PPDbench

- Web service

- Calculates CAPRI parameters for performance evaluation [18]

Step-by-Step Workflow

Input Structure Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure in PDB format, ensuring all atoms are present.

- Generate an initial 3D structure of the peptide using modeling software or experimental data.

- For blind docking, shift the Cartesian coordinates of the peptide away from the native binding site to avoid bias [18].

FRODOCK Execution:

- Access the FRODOCK web server or run the standalone version.

- Upload the protein and peptide structure files.

- Set parameters: angular step size (recommended: 5-10°), distance cutoff for interactions.

- Submit the job and retrieve results once processing is complete.

Result Processing:

- Download the top predicted complexes (typically top 100-1000 poses).

- Analyze the consensus binding mode across multiple high-ranking poses.

Performance Validation (Optional):

- For benchmarking, use PPDbench to calculate CAPRI parameters (FNAT, L-RMSD, I-RMSD) by comparing predicted poses with experimental structures [18].

- Evaluate the success of docking based on CAPRI criteria: acceptable (L-RMSD <10Å), medium (L-RMSD <5Å), high (L-RMSD <1Å) accuracy.

Diagram 2: FRODOCK Peptide Docking (76 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 6: Comprehensive Toolkit for Molecular Docking Research

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | AutoDock Suite [17] | Protein-ligand docking with flexible ligand | AutoDockTools GUI, Vina for speed, specialized tools for peptides |

| ZDOCK [18] | Rigid-body protein-protein/peptide docking | FFT-based global search, combination scoring function | |

| FRODOCK [18] | Rigid-body docking with spherical harmonics | Knowledge-based potentials, high peptide docking accuracy | |

| GOLD [15] | Flexible ligand docking with genetic algorithm | High pose prediction accuracy, suitable for virtual screening | |

| Structure Preparation | AutoDockTools [17] | Prepares receptor and ligand files | Adds hydrogens, calculates charges, generates PDBQT format |

| Raccoon2 [17] | Virtual screening workflow management | Manages coordinates, docking, and analysis for large libraries | |

| Binding Site Prediction | AutoSite [17] | Predicts ligand binding sites | Identifies potential binding pockets without prior knowledge |

| GRID [13] | Molecular interaction fields | Maps favorable interaction sites for different chemical groups | |

| Performance Evaluation | PPDbench [18] | Calculates CAPRI parameters for benchmarks | Web service for standardized docking assessment |

| Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced [19] | Virtual screening validation | Benchmarking sets for evaluating enrichment performance |

The evolution of molecular docking from simple shape complementarity to sophisticated flexible algorithms represents a remarkable scientific journey. Modern docking suites like AutoDock, which integrate multiple specialized tools, provide researchers with powerful methodologies for studying protein-ligand interactions [17]. While significant challenges remain—particularly in handling full receptor flexibility and improving pose ranking—current methods already achieve impressive accuracy, with top programs predicting binding poses within 1.5-2.0 Å RMSD from experimental structures for small molecules [15]. The continued development of docking methodologies, guided by community-wide assessments and benchmark studies, ensures that computational docking will remain a cornerstone technology for structural biology and drug discovery, enabling researchers to bridge the gap between molecular structure and biological function.

Molecular docking is a cornerstone computational technique in structural biology and drug discovery, aimed at predicting the optimal binding mode and affinity between a small molecule (ligand) and its biological target (receptor) [20]. The utility of docking extends across multiple applications in pharmaceutical research, including virtual screening of large compound libraries to identify novel hits, de novo design of new molecular entities, and lead optimization to improve affinity and selectivity of existing compounds [21]. The performance and predictive power of any molecular docking program rest on two fundamental computational pillars: the search algorithm and the scoring function [20] [22]. This application note delineates the core principles, classifications, and practical protocols for these components, providing researchers with a framework for the effective application of docking in protein-ligand interaction studies.

Core Component 1: Search Algorithms

Search algorithms are responsible for exploring the vast conformational and orientational space available to the ligand within the binding site of the receptor. Their objective is to generate a set of plausible binding poses by sampling the numerous translational, rotational, and internal degrees of freedom of the ligand.

Classification and Methodologies

Search algorithms employ diverse strategies to navigate the complex energy landscape of protein-ligand interactions:

- Systematic Search: This approach methodically explores all possible torsional angles of the ligand's rotatable bonds, often combined with incremental rotations and translations within the binding site. While thorough, it is computationally demanding and prone to combinatorial explosion for highly flexible ligands [20].

- Genetic Algorithms (GAs): Inspired by natural selection, GAs operate on a population of candidate poses. Through iterative cycles of crossover (combining parts of different poses), mutation (introducing random changes), and fitness-based selection, they evolve populations toward optimal solutions. GAs are particularly effective for handling ligand flexibility and are implemented in programs like GOLD [20].

- Shape Matching (Geometric Hashing): This class of algorithms, pioneered by programs like DOCK, treats the interaction as a geometric fit problem [23] [20]. It matches the three-dimensional shape of the ligand to a negative image of the binding cavity (represented by "spheres" as seen in DOCK protocols) to rapidly identify favorable orientations [23].

- Monte Carlo (MC) Methods: MC algorithms make random changes to the ligand's position and conformation. These new poses are accepted or rejected based on a probabilistic criterion (e.g., the Metropolis criterion), which allows the search to escape local minima and explore a broader energy landscape [20].

- Swarm Intelligence (SI): Algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) use a population (swarm) of particles that move through the search space, with their trajectories influenced by both individual and collective memory, leading to efficient convergence on promising regions [20].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): MD simulations use classical mechanics to simulate the physical movements of atoms over time. While traditionally too resource-intensive for standard docking, short MD simulations or pre-generated MD ensembles are increasingly used to account for protein flexibility and refine docking poses [24].

Protocol: A Standard Docking Workflow using DOCK

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for molecular docking using the DOCK software suite, demonstrating the practical integration of a search algorithm [23].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for a Docking Workflow

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) File | A file format containing the 3D atomic coordinates of a macromolecule. | Source of the initial receptor and ligand structures (e.g., PDB ID: 1XMU). |

| UCSF Chimera | A highly extensible program for interactive visualization and analysis of molecular structures. | Used for structure preparation, visualization, and file format generation. |

| DOCK 6.12 | A molecular docking program based on geometric shape-matching and physics-based scoring. | Core program for performing sphere generation, grid calculation, and docking. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A collection of computers working together for high-throughput computational tasks. | Provides the necessary computational power to run docking calculations. |

Objective: To perform a virtual screening workflow using the catalytic domain of Human Phosphodiesterase 4B (PDB Code: 1XMU) as a case study [23].

Software Prerequisites: DOCK 6.12, UCSF Chimera, and access to an HPC cluster.

Methodology:

Structure Preparation

- Receptor Preparation: Open the PDB file (1XMU.pdb) in Chimera. Delete the native ligand and all water molecules. Add hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger charges using the "AddH" and "Add Charge" tools, respectively. Save the prepared receptor in MOL2 format (e.g.,

1XMU_Rec_wCH.mol2). - Ligand Preparation: Isolate the native ligand from the same PDB file. Add hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger charges. Save the prepared ligand in MOL2 format (e.g.,

1XMU_lig_wCH.mol2). For virtual screening, a database of small molecules would be prepared similarly.

- Receptor Preparation: Open the PDB file (1XMU.pdb) in Chimera. Delete the native ligand and all water molecules. Add hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger charges using the "AddH" and "Add Charge" tools, respectively. Save the prepared receptor in MOL2 format (e.g.,

Surface and Sphere Generation

- In Chimera, generate a molecular surface for the prepared receptor (without hydrogens or charges). Use Tools → Structure Editing → Write DMS to create a surface file (

1XMU_surface.dms). - On the HPC cluster, use the DOCK utility

sphgento generate spheres that fill the binding pocket. The input file (INSPH) specifies the surface file and parameters for sphere generation. - Run

sphere_selectorto select spheres located within a specified distance (e.g., 10.0 Å) of the native ligand, thus defining the active site for docking.

- In Chimera, generate a molecular surface for the prepared receptor (without hydrogens or charges). Use Tools → Structure Editing → Write DMS to create a surface file (

Grid Generation

- The program

gridis used to pre-calculate the interaction energy of chemical probes across a 3D grid encompassing the selected spheres. This grid is used during docking for rapid scoring of ligand poses.

- The program

Docking Execution

- With the grid and spheres defined, run the docking calculation using the

dockexecutable. The input file specifies the ligand database, grid parameters, and search algorithm settings (e.g., orientation and conformation sampling methods). DOCK will generate multiple poses for each ligand, which are scored and ranked.

- With the grid and spheres defined, run the docking calculation using the

The workflow for this protocol, from structure preparation to result analysis, is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Molecular Docking Workflow using DOCK. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a standard docking protocol, from initial structure preparation to final pose analysis.

Core Component 2: Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical constructs used to evaluate and rank the binding poses generated by the search algorithm. They approximate the binding affinity, typically by estimating the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) upon binding, with more negative scores generally indicating stronger binding [21].

Classification of Scoring Functions

Scoring functions can be categorized into four primary classes, each with distinct theoretical foundations and practical trade-offs [21] [22] [25].

Table 2: Classification and Characteristics of Scoring Functions

| Type | Theoretical Basis | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field-Based | Molecular mechanics (van der Waals, electrostatic terms). | DOCK, GoldScore | Strong physical basis; energy components are interpretable. | Often oversimplifies solvation and entropy; requires careful parameterization. |

| Empirical | Weighted sum of interaction terms fitted to experimental binding data. | GlideScore, AutoDock Vina, LUDI | Fast calculation; good correlation with experiment for training sets. | Risk of overfitting; performance depends on representativeness of training data. |

| Knowledge-Based | Statistical potentials derived from frequency of atom-pair contacts in known structures. | DrugScore, PMF | Implicitly captures complex effects; no need for experimental affinities for training. | Lacks direct physical interpretation; quality depends on the size and quality of the structural database. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | ML models learn the relationship between structural features and binding affinity. | RF-Score, CNN-based models | High performance in binding affinity prediction; can model complex, non-linear relationships. | Requires large, high-quality training datasets; potential for poor generalization ("black box" nature). |

Performance Benchmarking and Selection

The choice of scoring function is critical and can be target-dependent. A 2015 comparative study of 16 scoring functions found that performance varied significantly across different protein targets. For instance, FlexX and GOLDScore produced good correlations for hydrophilic targets like Factor Xa and kinases, whereas pla2g2a and COX-2 emerged as difficult targets for most functions [26]. A 2025 benchmarking study further revealed that local docking strategies using functions like TankBind and Glide provided superior results for drugging protein-protein interfaces compared to blind docking [24].

Recent advances consistently show that machine-learning scoring functions tend to outperform classical functions in binding affinity prediction for diverse protein-ligand complexes and in structure-based virtual screening [21] [22]. For example, the PandaDock platform's PandaML algorithm demonstrated a 100% success rate in docking 50 complexes from the PDBbind database with sub-angstrom accuracy [27]. However, the best performance is often achieved when the function is trained or applied to data relevant to the specific target of interest [21].

Integrated Docking Protocol and Best Practices

This section synthesizes the components above into a generalized, robust protocol for molecular docking, incorporating current best practices.

Objective: To execute a docking experiment that reliably predicts the binding mode and affinity of a ligand to a protein target.

Workflow Overview:

Target Selection and Structure Preparation

- Action: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein from the PDB or generate a high-confidence model using a tool like AlphaFold2 [24]. Studies show AF2 models perform comparably to experimental structures in docking, especially when the binding site is accurately predicted.

- Protocol: Prepare the protein using a tool like Chimera's Dock Prep or the Spruce TK [23] [28]. Critical steps include:

- Adding missing hydrogen atoms.

- Assigning appropriate protonation states for residues like His, Asp, and Glu at the physiological pH of interest.

- Assigning partial atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger or AM1-BCC).

- Removing crystallographic water molecules, unless they are part of a conserved water network or directly coordinated to a metal ion.

Ligand Preparation

- Action: Prepare the small molecule ligand(s) for docking.

- Protocol: Generate realistic 3D conformations from a 1D SMILES string or 2D structure. Use a tool like Omega TK or RDKit to sample low-energy conformers. Add hydrogens and assign charges consistent with those used for the receptor.

Binding Site Definition and Search Algorithm Configuration

- Action: Define the search space. This can be done based on the location of a co-crystallized ligand, known functional residues, or through binding site detection algorithms.

- Protocol: In tools like SwissDock, users can interactively select residues to define the search box [29]. In DOCK, this is achieved via sphere selection [23].

- Action: Configure the search. Select a search algorithm (e.g., Genetic Algorithm in GOLD, Monte Carlo in AutoDock) suitable for the ligand's flexibility and the required sampling exhaustiveness.

Docking Execution and Pose Scoring

- Action: Run the docking calculation.

- Protocol: The prepared receptor and ligand files are used as input. The search algorithm generates poses, which are evaluated by the primary scoring function. It is standard practice to generate 10-50 poses per ligand to ensure adequate sampling.

Post-Docking Analysis and Validation

- Action: Critically evaluate the results.

- Protocol:

- Pose Clustering and Visual Inspection: Examine the top-ranked poses. A reliable prediction often has multiple similar poses (a cluster) with good scores. Use visualization software to check for sensible intermolecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges).

- Rescoring: Employ a different, and preferably more advanced, scoring function to re-rank the generated poses. This could be a more rigorous physics-based method, a machine-learning scoring function, or a consensus approach across multiple functions [21] [22].

- Validation: If the experimental binding mode is known (e.g., from a co-crystal structure), calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted pose and the experimental structure. An RMSD below 2.0 Å is typically considered a successful prediction [27] [25].

Molecular docking is an indispensable tool for probing protein-ligand interactions in silico. Its efficacy is fundamentally governed by the integrated performance of its two core components: the search algorithm, which explores the vast conformational space, and the scoring function, which identifies the most biologically relevant poses. While classical search algorithms and scoring functions remain widely used, the field is rapidly evolving with the integration of machine learning, ensemble-based approaches using MD-refined or AF2-predicted structures, and more sophisticated benchmarks. A thorough understanding of these components, coupled with rigorous validation protocols, empowers researchers to leverage docking as a powerful and predictive asset in drug discovery and basic biomedical research.

Molecular docking is a foundational computational technique in structural biology and computer-aided drug design that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein. By predicting this binding mode, researchers can infer the binding affinity and biological activity of the ligand, accelerating drug discovery and development processes. The core challenge in molecular docking lies in accurately simulating molecular recognition, which in biological systems involves complex processes governed by physical forces and conformational adjustments [30]. The docking process essentially consists of two main components: sampling (exploring possible ligand binding orientations/conformations) and scoring (evaluating and ranking these possibilities using energy functions) [31]. Over decades of development, three major docking paradigms have emerged—rigid docking, flexible docking, and blind docking—each with distinct approaches to balancing computational efficiency with biological accuracy within the broader context of protein-ligand interactions research.

Rigid-Body Docking

Fundamental Principles and Assumptions

Rigid-body docking represents the simplest computational approach, operating on the fundamental assumption that both the protein receptor and the ligand maintain fixed conformations throughout the binding process. This method treats the interaction as a lock-and-key system, where the ligand (key) possesses a static three-dimensional structure that complements the binding site of the protein (lock) without either molecule undergoing conformational changes [30]. The primary objective of rigid docking is to identify the optimal alignment between two rigid structures that maximizes shape complementarity while minimizing steric clashes [32] [33]. This simplification dramatically reduces the computational complexity of the docking problem by limiting the search space to only six degrees of freedom—three translational and three rotational—without considering internal structural flexibility [32].

Methodological Approaches

Rigid docking employs several computational strategies to efficiently explore the spatial relationship between protein and ligand. Shape matching algorithms constitute a primary method, where the molecular surface of the ligand is systematically aligned to complement the molecular surface of the protein's binding site [31]. Programs implementing this approach include DOCK, FRED, and FLOG [31]. Reciprocal space methods represent another strategy, utilizing fast Fourier transforms to efficiently evaluate shape complementarity across numerous possible orientations by representing proteins as simple cubic lattices [32] [33]. These methods can rapidly assess enormous numbers of configurations but become less efficient when torsional changes are introduced [33]. A significant advantage of rigid-body docking is its computational efficiency, allowing for rapid screening of large compound libraries when the binding site is known and minimal conformational changes occur upon binding [32].

Applications and Limitations

Rigid docking finds particular utility in virtual screening of large compound databases against targets with well-characterized, rigid binding sites [30]. It also serves as an initial sampling step in more sophisticated docking pipelines, providing candidate structures for subsequent refinement [34] [35]. However, the fundamental limitation of this approach stems from its neglect of molecular flexibility, which is physiologically unrealistic. Most proteins exhibit some degree of conformational adaptability upon ligand binding, ranging from side-chain adjustments to large-scale domain movements [34] [35]. This "induced fit" effect means that rigid docking often fails to accurately predict binding modes when significant conformational changes occur, potentially resulting in false negatives or inaccurate affinity predictions [35] [31].

Table 1: Key Rigid-Body Docking Software and Their Methodologies

| Software | Sampling Method | Scoring Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOCK | Shape matching, Geometric hashing | Force field, Chemical matching | Virtual screening, Binding mode prediction |

| FRED | Shape matching with conformer ensembles | Empirical, Knowledge-based | High-throughput screening |

| FLOG | Shape matching | Empirical descriptors | Database screening |

| ZDOCK | Fast Fourier Transform | Shape complementarity, electrostatics | Protein-protein docking |

Flexible Docking

Accounting for Molecular Flexibility

Flexible docking represents a more sophisticated approach that acknowledges and incorporates the reality of molecular flexibility in binding interactions. This paradigm recognizes that both ligands and proteins can undergo significant conformational changes during complex formation, as described by the induced-fit model where binding partners adjust their structures to achieve optimal complementarity [34] [30] [35]. Some methods also incorporate the conformational selection model, which posits that proteins exist as ensembles of pre-existing conformations, with ligands selectively binding to compatible states [34] [35]. Flexible docking methods must navigate the considerable challenge of exponentially expanding the search space when internal degrees of freedom are added to the six rigid-body degrees of freedom [34] [31]. Consequently, these methods employ intelligent strategies to sample relevant conformational changes without becoming computationally prohibitive.

Methodological Strategies for Handling Flexibility

Ligand Flexibility

Most flexible docking approaches focus primarily on ligand flexibility, as small molecules typically have fewer degrees of freedom than proteins. Systematic search methods explore rotatable bonds at regular intervals, though they face combinatorial explosion with highly flexible ligands [31]. Fragmentation methods decompose ligands into rigid segments that are docked separately before reassembly, as implemented in FlexX and DOCK [31]. Stochastic algorithms use Monte Carlo methods or genetic algorithms to make random changes to ligand conformation, accepting or rejecting them based on probabilistic criteria [32] [33] [31]. Conformational ensemble approaches dock multiple pre-generated ligand conformations rather than modeling flexibility on-the-fly [31].

Protein Flexibility

Incorporating protein flexibility presents greater challenges due to the larger number of degrees of freedom. Side-chain flexibility methods keep the protein backbone fixed while allowing side-chains to adopt alternative conformations using rotamer libraries [31]. Molecular relaxation approaches perform initial rigid docking followed by energy minimization of the resulting complexes using molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo methods [35] [31]. Backbone flexibility techniques employ normal mode analysis to model large-scale conformational changes, focusing on low-frequency modes that often capture biologically relevant motions [34] [35]. Ensemble docking uses multiple protein structures from different experimental conditions or conformational sampling to represent flexibility [31].

Advanced Flexible Docking Techniques

Recent methodological advances have led to more sophisticated flexible docking approaches. The FiberDock method incorporates both backbone and side-chain flexibility during refinement by iteratively minimizing structures along the most relevant normal modes identified through force correlation analysis [35]. Molecular dynamics-based approaches provide explicit simulation of atomic movements but remain computationally demanding for routine docking applications [34]. Replica-exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) methods, as implemented in EDock, enhance sampling efficiency by running multiple simulations at different temperatures and allowing exchanges between them [36]. The emerging FABFlex framework represents a regression-based multi-task learning model that simultaneously predicts binding sites and the holo structures of both ligands and protein pockets in a unified process [37].

Diagram 1: Flexible docking workflow with key stages.

Blind Docking

Conceptual Foundation and Challenges

Blind docking represents a specialized docking approach where the binding site on the protein surface is unknown beforehand, requiring the exploration of the entire protein surface to identify potential binding regions. This method is particularly valuable when studying proteins with uncharacterized binding sites or when investigating potential allosteric binding pockets [38] [36]. The central challenge in blind docking stems from the massive expansion of the search space compared to site-specific docking. Whereas conventional docking restricts sampling to a defined binding pocket, blind docking must evaluate the entire protein surface, increasing computational demands by orders of magnitude [38]. This expanded search space coupled with the need to maintain sufficient sampling density makes blind docking particularly susceptible to false positives and poses significant scoring challenges [38] [36].

Computational Strategies and Implementations

Search space management constitutes a primary consideration in blind docking implementations. Some approaches, like QuickVina-W, employ inter-process spatio-temporal integration to enhance search efficiency across large volumes by enabling communication between parallel search threads [38]. This allows threads to share information about explored regions, reducing redundant sampling and improving decision-making speed. Hierarchical approaches initially perform coarse-grained scanning of the entire protein surface followed by focused refinement of promising regions [38] [36]. Replica-exchange Monte Carlo methods, as implemented in EDock, enhance sampling efficiency by running parallel simulations at different temperatures and permitting exchanges between them, preventing trapping in local minima [36]. Binding site prediction integration combines docking with binding site detection algorithms. EDock, for instance, first predicts binding sites using sequence-profile and substructure comparisons before generating initial ligand poses through graph matching [36].

Advanced Blind Docking Frameworks

Recent advances in blind docking incorporate machine learning and multi-task learning frameworks. FABFlex exemplifies this trend with its three specialized modules: a pocket prediction module that identifies potential binding sites, a ligand docking module that predicts bound ligand structures, and a pocket docking module that forecasts the holo structures of protein pockets [37]. The system employs an iterative update mechanism that facilitates information exchange between the ligand and pocket docking modules, enabling continuous structural refinements in a unified process [37]. This approach addresses the critical challenge of working with predicted protein structures from sources like AlphaFold2, which often exhibit discrepancies between apo predictions and actual holo structures [37]. These advanced methods demonstrate significantly improved performance in blind docking scenarios, with FABFlex reporting approximately 208-fold speed advantage over previous flexible docking methods while maintaining accuracy [37].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Docking Methods on Standard Benchmarks

| Method | Docking Type | Ligand RMSD <2Å (%) | Pocket RMSD (Å) | Computational Speed | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Rigid/Flexible Ligand | ~25-30% | N/A | Medium | Good balance of speed and accuracy |

| QuickVina-W | Blind Docking | ~28-33% | N/A | Fast | Optimized for large search spaces |

| EDock | Blind Flexible | ~35% | N/A | Medium | Robust with predicted structures |

| FiberDock | Flexible Refinement | Improvement over rigid | ~1.5-2.0 | Slow | Advanced backbone flexibility |

| FABFlex | Blind Flexible | 40.59% | 1.10Å | Very Fast | End-to-end prediction |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standardized Docking Protocols

Rigid-Body Docking Protocol

A typical rigid-body docking protocol begins with structure preparation, where hydrogen atoms are added to both protein and ligand structures, partial charges are assigned, and solvation parameters are configured [30]. The binding site is then defined using known catalytic residues or from experimental data. For the actual docking, sampling algorithms such as shape matching or FFT-based methods generate thousands of potential binding orientations [32] [31]. Each generated pose is evaluated using a scoring function that typically includes terms for van der Waals interactions, electrostatic complementarity, and desolvation effects [22] [31]. The top-ranked poses are visually inspected for reasonable interaction patterns, such as hydrogen bonding with key residues or appropriate positioning in catalytic sites [30].

Flexible Docking Protocol

Comprehensive flexible docking follows an extended workflow. The preprocessing stage involves analyzing protein flexibility through normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics simulations, or comparison of multiple experimental structures [34]. An initial rigid-body docking phase generates candidate complexes, allowing some steric clashes to account for anticipated conformational adjustments [34] [35]. The refinement stage then optimizes these candidates through side-chain repacking using rotamer libraries, backbone minimization along relevant normal modes, and rigid-body adjustments [35]. Finally, scoring and ranking employ more sophisticated energy functions that may include terms for deformation energy and binding entropy in addition to standard interaction energies [34] [35].

Blind Docking Protocol

Specialized protocols for blind docking begin with binding site prediction using algorithms like COACH, which combines sequence-profile comparisons, structural similarity matching, and surface cavity detection [36]. The search space is defined as a box encompassing the entire protein or multiple boxes covering different surface regions [38]. Enhanced sampling algorithms such as replica-exchange Monte Carlo or inter-process communication methods extensively explore this expanded space [38] [36]. Post-processing involves clustering similar poses and applying consensus scoring to mitigate limitations of individual scoring functions [36].

Assessment and Validation Frameworks

Docking method validation relies on standardized benchmarks and blind trials. The Protein-Protein Docking Benchmark provides carefully curated test cases with known complex structures, categorizing examples by difficulty based on the extent of conformational change [32] [33]. For protein-ligand docking, the PDBbind database offers thousands of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data for development and validation [22]. The Critical Assessment of Predicted Interactions (CAPRI) organizes regular blind trials where participants predict unknown complex structures, providing objective community-wide assessment [32] [33]. These validation frameworks have revealed that while current docking methods achieve reasonable success rates for enzyme-inhibitor complexes, antibody-antigen complexes and targets with large conformational changes remain challenging [32].

Diagram 2: Docking assessment framework and applications.

Key Software Tools

The molecular docking landscape features diverse software implementations catering to different docking scenarios. AutoDock Vina represents one of the most widely used tools, employing a hybrid scoring function and evolutionary search algorithm that balances accuracy with computational efficiency [38] [22]. QuickVina-W extends this capability specifically for blind docking through inter-process spatio-temporal integration that enhances search efficiency across large protein surfaces [38]. EDock specializes in blind docking with replica-exchange Monte Carlo sampling, demonstrating particular robustness when working with predicted protein structures from sources like I-TASSER [36]. FiberDock focuses on flexible refinement of docking solutions, incorporating both backbone flexibility through normal mode analysis and side-chain flexibility using rotamer libraries [35]. FABFlex represents an emerging machine learning approach that unifies binding site prediction, ligand docking, and pocket conformation prediction in an end-to-end framework [37].

Critical Datasets and Benchmarks

Rigorous docking development and validation relies on standardized benchmarks. The PDBbind database provides a comprehensive collection of protein-ligand complexes with experimentally measured binding affinities, currently containing over 19,000 structures in its 2020 release [22]. The Protein-Protein Docking Benchmark offers categorized test cases for protein-protein interactions, with the latest version containing 230 complexes classified by difficulty based on conformational change magnitude [33]. Specialized benchmarks exist for protein-nucleic acid interactions, with curated datasets of protein-DNA and protein-RNA complexes [33]. The DUDE and COACH datasets provide additional resources for method development and testing, particularly for binding site prediction and decoy generation [36].

Computational Infrastructure

Successful docking applications require appropriate computational resources. Hardware requirements range from standard desktop computers for single rigid docking calculations to high-performance computing clusters for extensive flexible docking or virtual screening. Preprocessing tools facilitate critical preparation steps including hydrogen addition, charge assignment, and protonation state determination at biological pH [30]. Visualization software such as PyMOL or Chimera enables critical analysis of docking results and interaction patterns. Analysis scripts help with post-processing tasks including RMSD calculation, clustering of similar poses, and extraction of key interaction metrics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, DOCK, GOLD, Glide | Pose generation and scoring | All docking types |

| Flexible Docking Tools | FiberDock, FlexX, RosettaDock | Modeling conformational changes | Flexible docking scenarios |

| Blind Docking Solutions | QuickVina-W, EDock, FABFlex | Binding site identification + docking | Uncharacterized targets |

| Benchmark Datasets | PDBbind, Protein-Protein Docking Benchmark | Method development and validation | Algorithm assessment |

| Structure Preparation | MolProbity, PDB2PQR, PROPKA | Hydrogen addition, charge assignment | Pre-docking processing |

| Analysis & Visualization | PyMOL, Chimera, LigPlot+ | Result interpretation and visualization | Post-docking analysis |

Molecular docking has evolved from simple rigid-body approaches to sophisticated methods that increasingly capture the complexity of biomolecular recognition. The three major docking types—rigid, flexible, and blind docking—offer complementary strengths that make them suitable for different research scenarios. Rigid docking provides computational efficiency for high-throughput screening, flexible docking enables more realistic modeling of molecular interactions, and blind docking allows exploration of uncharacterized proteins. Current challenges include improving the treatment of large-scale conformational changes, developing more reliable scoring functions, and enhancing methods for working with predicted protein structures. Emerging trends point toward increased integration of machine learning approaches, more efficient sampling algorithms, and unified frameworks that combine binding site prediction with flexible docking. These advances will further solidify docking's role as an indispensable tool in structural biology and drug discovery, enabling researchers to increasingly accurately model the complex interplay between proteins and their molecular partners.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Successful Docking and Virtual Screening

In molecular docking for drug discovery, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" holds profound significance. The accuracy of any docking simulation is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the initial protein and ligand structures used as input. Recent research underscores that widely-used datasets like PDBbind contain significant structural artifacts, statistical anomalies, and sub-optimal organization that can compromise the accuracy, reliability, and generalizability of resulting scoring functions [39]. Similarly, benchmarking studies reveal that the commonly used PDBBind time-split test-set is inappropriate for comprehensive protein-ligand complex evaluation, with state-of-the-art tools showing conflicting results on more representative and high-quality datasets [40]. These inconsistencies undermine the purpose of refined sets intended to serve as high-quality benchmarks for evaluating scoring functions and docking methods.

The critical importance of structure preparation extends across all docking approaches, whether utilizing experimentally solved structures or predicted models from systems like AlphaFold2. Studies evaluating ligand docking methods for drugging protein-protein interfaces reveal that while AlphaFold2 models perform comparably to native structures in docking protocols, their effectiveness still depends on proper preparation and refinement [24]. Furthermore, assessments of docking tools consistently demonstrate that preparation quality significantly influences binding mode prediction accuracy and virtual screening enrichment [41] [42]. This protocol details comprehensive, reproducible workflows for protein and ligand structure preparation to ensure researchers can generate reliable inputs for docking studies, thereby maximizing the predictive value of subsequent computational analyses.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Benchmarks

The Impact of Structure Quality on Docking Outcomes

The relationship between input structure quality and docking success has been quantitatively demonstrated across multiple studies. Evaluations of docking programs for cyclooxygenase inhibitors revealed performance variations from 59% to 100% in correctly predicting binding poses (RMSD < 2 Å) depending on preparation methods [42]. The Glide program achieved 100% success with proper preparation, while other tools showed substantially lower performance, highlighting how preparation quality interacts with algorithmic capabilities.

When utilizing predicted structures, the degradation of docking performance becomes even more pronounced. Studies show that the success rate for ligand docking decreases by approximately half when using predicted structures compared to holo-structures (20.3% vs. 38.2%) [43]. This performance drop underscores the necessity of rigorous curation and refinement for structures not determined experimentally with their bound ligands.

Comparative Performance of Docking Methods with Prepared Structures

Table 1: Success Rates of Various Protein-Ligand Complex Prediction Methods

| Method | Input Requirements | Success Rate (LRMSD ≤ 2 Å) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Native holo-protein + target area | 52% | Requires experimental structure |

| Umol-pocket | Sequence + ligand SMILES + pocket | 45% | Limited very high precision (<0.5Å) |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Sequence + ligand | 42% | Performance drops to 8% without templates |

| NeuralPlexer1 | Sequence + ligand | 24% | Moderate accuracy |

| Umol (blind) | Sequence + ligand SMILES | 18% | Lower accuracy without pocket information |

| AlphaFold2 + DiffDock | AF2 structure + ligand | 21% | Dependent on AF2 pocket accuracy |

Data compiled from benchmarking studies [43]