Mastering Solvation Effects in Structure-Based Drug Design: From Theory to Clinical Application

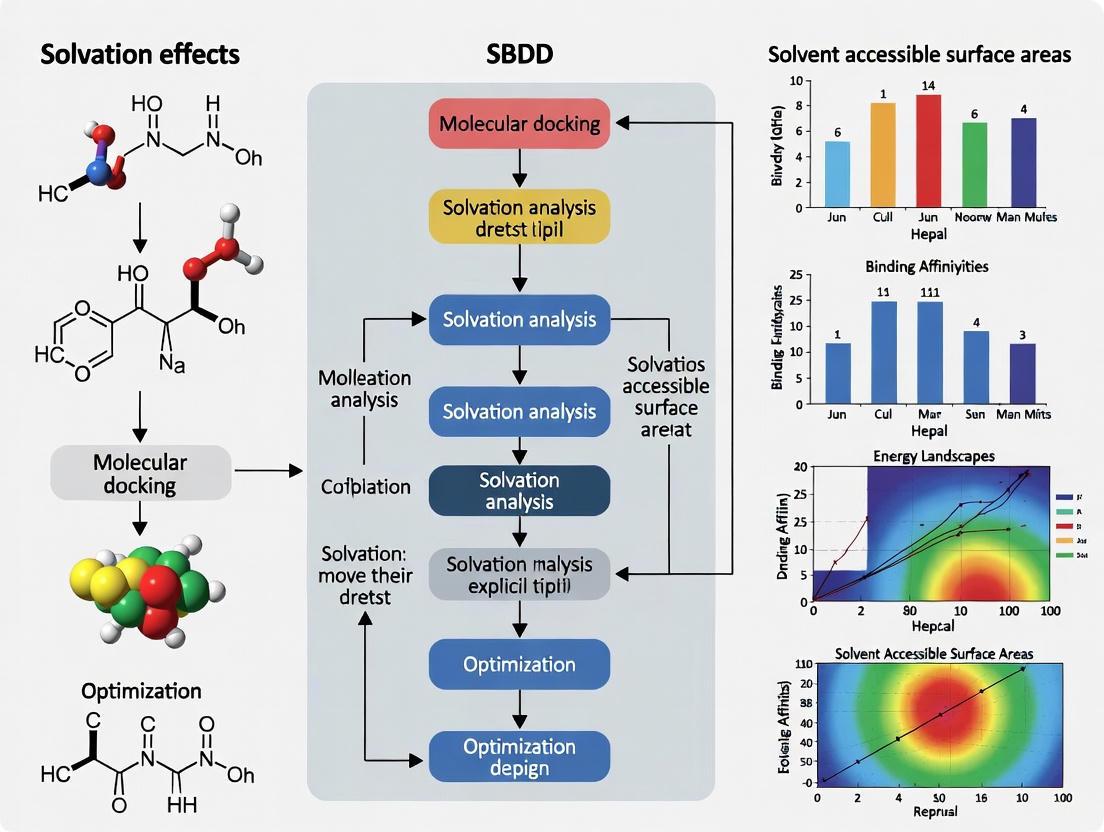

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on handling solvation effects in Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD).

Mastering Solvation Effects in Structure-Based Drug Design: From Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on handling solvation effects in Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD). Solvation is a critical but often overlooked factor that significantly influences protein-ligand binding affinity, prediction accuracy, and ultimately drug efficacy. We explore the fundamental principles of solvation, covering both traditional implicit/explicit models and cutting-edge machine learning approaches. The content delves into practical methodologies for implementation, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and offers validation frameworks for comparing computational predictions with experimental results. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with advanced applications, this resource aims to bridge the gap between theoretical models and real-world drug discovery challenges, enabling more accurate and efficient development of therapeutic candidates.

The Critical Role of Water: Foundational Principles of Solvation in SBDD

Conceptual Foundations: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is explicitly accounting for solvation so critical for accurate binding affinity predictions in Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)?

Predicting binding affinity is notoriously difficult because binding occurs in the presence of a solvent, and predictions will always fall short if this is not fully accounted for [1]. A protein's binding sites in the unbound state are not empty; they are occupied mainly by water molecules that do not behave as a homogeneous solvent but have well-defined hydration spots and regions where water density is much lower than in bulk solvents [1]. The thermodynamics of the subsequent solvent reorganization process—whereby these water molecules are displaced or retained to bridge interactions—is a key contribution to the complex formation free energy and thus to the ligand's binding affinity [1].

FAQ 2: What are the fundamental thermodynamic components of solvation?

The solvation free energy can be conceptually broken down into two primary steps, each with enthalpic and entropic contributions [2]:

- ΔG₁: Cavity Formation. This is the free energy required to open a cavity in the water. It involves breaking the strong cohesive intermolecular interactions in water (an unfavorable, positive ΔH₁) and reducing the configurational entropy of the water hydrogen-bond network (an unfavorable, negative TΔS₁). Consequently, ΔG₁ is large and positive, and this term dominates the hydrophobic effect [2].

- ΔG₂: Solute Insertion. This is the free energy gained from inserting the solute into the cavity and turning on the interactions between the solute and solvent. For ions and polar solutes, this term is usually dominated by favorable electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions (a favorable, negative ΔH₂) [2].

The overall solvation free energy is the sum: ΔG_sol = ΔG₁ + ΔG₂ = (ΔH₁ - TΔS₁) + (ΔH₂ - TΔS₂) [2]. These terms are often large and opposing, leading to a high degree of uncertainty if not properly evaluated.

FAQ 3: My lead compound shows excellent shape complementarity and electrostatic potential with the target's binding pocket, yet its measured binding affinity is weak. What solvation-related factors could be the cause?

This common issue can often be traced to incomplete analysis of the solvent. Key factors to investigate include:

- Displacement of High-Energy Water: The binding site may contain one or more highly stable, tightly bound water molecules. The thermodynamic cost of displacing these waters may outweigh the energetic benefit gained from the direct protein-ligand interactions [1]. These waters can have residence times ranging from 1 ns to 106 ns [1].

- Poor Solvent-Shell Disruption: Your compound might be insufficiently disrupting the ordered solvent shell around hydrophobic regions of the binding site, thereby failing to capitalize on the entropic gain (the hydrophobic effect) that drives binding [2].

- Ignored Water-Mediated Interactions: The compound's binding mode might fail to preserve key water molecules that act as crucial bridges for hydrogen-bonding networks between the protein and the ligand [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Inaccurate Binding Free Energy Estimates from Computational Docking

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low hit rates in virtual screening; poor correlation between docking scores and experimental binding affinities. | The scoring function uses an implicit solvent model that fails to capture key features of explicit water, such as the energetic cost of displacing specific water molecules or the entropic gain from releasing others. | Incorporate explicit solvent information. Perform MD simulations to identify Water Sites (WS)—regions with a high probability of finding a water molecule—and their properties (residence time, interactions). Use this data to inform or post-process docking poses [1]. |

Problem 2: Difficulty Identifying Viable Binding Pockets or Hot Spots on a Protein Target

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A seemingly flat protein surface with no obvious deep pockets; known active-site inhibitors cannot be rationalized. | Traditional surface analysis may miss regions that are key for binding but are only revealed by solvent behavior. These "hot spots" are regions on the protein surface that provide most of the binding affinity [1]. | Employ Mixed-Solvent Molecular Dynamics (MDmix). Simulate the protein in an aqueous solution containing small organic solvent probes (e.g., isopropanol, which captures hydrophobic and H-bond properties). The probes will preferentially bind to and reveal these hot spots, identifying key interaction sites for drug-like molecules [1]. |

Problem 3: Failure to Explain Potency Differences in a Congeneric Series of Inhibitors

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Small chemical modifications in a lead series lead to drastic, unexplained changes in potency that cannot be rationalized by static protein-ligand structures. | Cryo-cooled crystallography may trap the protein-ligand complex in a single, non-representative low-energy conformation, masking critical conformational dynamics and solvation differences [3]. | Utilize Room-Temperature Serial Crystallography. This technique can capture conformational dynamics and flexibility in the binding site that are lost at cryogenic temperatures. It can reveal alternative ligand binding modes, disrupted hydrogen bonds, and flexible regions that explain potency differences [3]. |

Key Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Identification of Binding Hot Spots Using Mixed-Solvent MD (MDmix)

Objective: To systematically identify and characterize preferential binding sites ("hot spots") on a protein surface using molecular dynamics simulations with mixed solvents [1].

Detailed Workflow:

- System Setup:

- Place the protein structure (e.g., from the PDB) in a simulation box.

- Solvate the system with water mixed with a low concentration (1-5%) of organic probe molecules. Isopropanol is a common choice as it contains both hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor moieties common in drugs [1].

- Simulation Run: Perform a long-timescale MD simulation (modern workstations can handle this). Ensure the simulation runs for a sufficient duration (e.g., 20-50 ns for good convergence of water sites) to allow for adequate sampling of probe binding events [1].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the simulation trajectory to identify regions where the probe molecules accumulate preferentially.

- These regions of high probe density correspond to binding hot spots.

- The chemical nature of the interactions (hydrophobic, H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor) can be inferred from the behavior of the probe.

- Application: Use the identified hot spots to guide molecular docking, virtual screening, and lead optimization by ensuring designed compounds target these energetically favorable regions [1].

The logical flow of this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Mapping Hydration Sites Using Explicit Solvent MD

Objective: To determine the positions, stability, and thermodynamic properties of water molecules within a protein's binding site to inform ligand design [1].

Detailed Workflow:

- System Setup & Simulation: Place the protein in a box of explicit water molecules and run a standard MD simulation.

- Identify Water Sites (WS): Apply a clustering algorithm to the positions of water oxygen atoms from the simulation trajectory to define discrete Water Sites [1].

- Characterize WS Properties:

- Water Finding Probability (WFP): The probability of finding a water molecule in the site.

- Residence Time: How long a water molecule remains in the site (can range from 10 ps to >1 μs) [1].

- Energetics: Use methods like the Inhomogeneous Fluid Solvation Theory (IFST) to characterize the thermodynamics of each site [1].

- Ligand Design Strategy:

- Displace: Design ligand functional groups to displace water sites with low WFP and/or unfavorable energies (positive ΔG), as this is thermodynamically favorable.

- Mimic or Keep: If a water site has a high WFP, very negative ΔG (tightly bound), or acts as a critical bridge in an H-bond network, consider designing ligand groups that mimic its position or leave it undisturbed [1].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for designed ligands based on water site properties:

The following table details key materials and tools used in the experiments and methods cited in this guide.

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Experiment / Analysis |

|---|---|

| Organic Probe Solvents (e.g., Isopropanol) | Used in MDmix simulations to identify protein surface "hot spots" by mimicking diverse chemical features of drug-like molecules [1]. |

| Microcrystals (10+ microns) | Essential for serial room-temperature crystallography, enabling the collection of high-quality, damage-free diffraction data that captures protein dynamics [3]. |

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Creates a thin liquid jet (<10 µm) to deliver a continuous stream of fresh microcrystals for X-ray diffraction at XFELs, preventing radiation damage [3]. |

| Fixed Target Chips (e.g., Silicon) | Sample supports for serial synchrotron crystallography onto which microcrystals are pipetted; allows high-throughput raster scanning for data collection [3]. |

| Water Map Software (e.g., WaterMap) | Computational tool used to analyze MD trajectories and identify hydration sites, calculating their thermodynamics (entropy, enthalpy) to guide ligand design [4]. |

| Protein Preparation Software (e.g., PDB2PQR, PROPKA) | Prepares protein structures from the PDB for simulation or docking by adding H atoms, assigning protonation states, and optimizing H-bond networks [4]. |

Thermodynamics Reference Data

The table below summarizes key thermodynamic parameters and concepts relevant to solvation and binding.

| Parameter / Concept | Symbol / Term | Typical Range / Value | Relevance to Binding Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Energy of Solvation | ΔGsol | Varies by solute (e.g., -237 kJ/mol for liquid water [5]) | Determines solute solubility; contributes to the overall binding free energy cycle. |

| Cavity Formation Free Energy | ΔG1 | Large and positive [2] | Major driver of the hydrophobic effect; favors binding that releases ordered water. |

| Solute-Solvent Interaction Energy | ΔG2 | Large and negative for polar/charged solutes [2] | Favors solvation; must be overcome by strong protein-ligand interactions upon binding. |

| Water Residence Time | τ | 10 ps to >1 μs [1] | Indicates stability of a hydration site; long residence times suggest costly displacement. |

| Binding Affinity Constant | KA / KD | KA = 1/KD = exp(-ΔGBIND/RT) [1] | The primary experimental measure of ligand potency, directly related to the binding free energy. |

Conceptual Foundations in SBDD

In Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD), accurately modeling the solvent environment is not a peripheral concern but a central challenge. The binding affinity between a drug candidate and its protein target is profoundly influenced by the surrounding water and ions, as binding occurs in a condensed state with numerous configurational possibilities [1]. Solvent reorganization during ligand binding is a key thermodynamic contribution to the free energy of complex formation [1]. The following models provide different frameworks for capturing these critical effects.

Explicit Solvation Models

Explicit solvent models treat solvent molecules as individual entities with defined coordinates and degrees of freedom [6]. This approach provides a physically realistic, atomistic picture of the solvent environment.

- Core Principle: The solute is immersed in a bath of explicit solvent molecules, often water. Molecular Dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo simulations are then used to sample the system's configurations [6] [1].

- Key Features: These models can capture specific solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, and solvent ordering phenomena like the formation of hydration shells around a solute [6]. They are particularly valuable for revealing preferential interaction sites, or "hot spots," on protein surfaces [1].

- Common Implementations: Simplified, parametrized models are common for efficiency. For water, these include the TIPnP and Simple Point Charge (SPC) families, which use a fixed number of interaction sites with point charges and repulsion/dispersion parameters [6]. A new generation of polarizable force fields, such as AMOEBA, is also emerging to account for changes in molecular charge distribution [6].

Implicit Solvation Models

Implicit solvent models, also known as continuum models, replace the explicit solvent molecules with a homogeneously polarizable medium characterized by macroscopic properties like the dielectric constant (ε) [6] [7].

- Core Principle: The solute is placed inside a cavity within a continuous dielectric medium. The solvent's response to the solute's charge distribution is modeled as a reaction field, which is included as a perturbation to the solute's Hamiltonian [6].

- Key Features: This approach is computationally efficient and avoids the need to simulate numerous solvent molecules. The solvation free energy is typically decomposed into contributions from cavity formation, electrostatic polarization, and dispersion-repulsion interactions [6].

- Common Implementations:

- CPCM/COSMO: The Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) treats the bulk solvent as a conductor-like continuum and is invoked with keywords like

CPCM(solvent)in computational software such as ORCA [7]. - SMD: The Solvation Model based on Density (SMD) is an extension that uses the full solute electron density to compute the non-electrostatic (cavity-dispersion) contribution, making it more parametrized but potentially more accurate [6] [7].

- Recent Advances: Methods like the Analytical Linearized Poisson–Boltzmann (ALPB) model are being combined with semiempirical quantum methods (e.g., GFN2-xTB) to efficiently add solvation corrections to calculations from neural network potentials [8].

- CPCM/COSMO: The Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) treats the bulk solvent as a conductor-like continuum and is invoked with keywords like

Hybrid Solvation Models

Hybrid models aim to strike a balance between the computational efficiency of implicit models and the physical realism of explicit models [6] [9].

- Core Principle: A small number of explicit solvent molecules are included in the primary region of interest (e.g., the first solvation shell of a solute or a protein's active site), while the bulk solvent is treated as an implicit continuum [6] [9].

- Key Features: This setup ensures bulk solvent behavior at the boundary with the continuum while retaining specific, local solvent interactions [9]. It is particularly useful in QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) simulations, where the core region (QM) and its immediate solvation shell can be treated with explicit solvent, while the outer environment is handled with a cheaper MM or implicit model [6].

- Validation: Studies have shown that such hybrid models can describe dynamical and solvent effects with an accuracy comparable to conventional approaches using periodic boundary conditions [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Solvation Model Characteristics

| Feature | Explicit Models | Implicit Models | Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | High [6] | Low [6] | Moderate [6] |

| Treatment of Solvent | Individual molecules with degrees of freedom [6] | Continuum dielectric medium [6] | Explicit molecules near solute + continuum bulk [6] [9] |

| Description of Solvent Shells | Spatially resolved, captures local fluctuations [6] | Averaged, isotropic; misses local structure [6] | Captures local structure in explicit region only [6] |

| Common Use Cases in SBDD | MD simulations to find water sites/hot spots [1] | Quick scoring in docking, initial geometry optimizations [6] | QM/MM MD simulations of reaction mechanisms [6] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My implicit solvent calculations on a protein-ligand system are yielding poor binding affinity predictions. What could be wrong? Implicit models struggle with specific solvent effects. If the binding site contains tightly bound water molecules that mediate protein-ligand interactions (e.g., through bridging hydrogen bonds), an implicit model will fail to capture their contribution [1]. Consider using a hybrid explicit/implicit approach or post-processing your results with tools like WaterMap that characterize the thermodynamics of crystallographic water molecules [1] [4].

Q2: Why does my gas-phase neural network potential (NNP) fail to model a simple thia-Michael addition reaction? Unsolved anions are highly unstable and reactive in the gas phase, leading to a confused potential-energy surface with an unclear barrier [8]. The fundamental problem is the lack of a solvent environment to stabilize the ions. You must incorporate solvation effects, for instance, by adding an implicit-solvent correction (e.g., ALPB) to the NNP calculations [8].

Q3: My MD simulations with explicit solvent are computationally expensive and slow to converge. Are there alternatives for identifying binding hot spots? Yes, consider Mixed Solvent MD (MDmix). This method involves simulating the protein in an aqueous solution containing a low concentration of organic solvent probes (e.g., isopropanol) [1]. The probes will preferentially bind to favorable interaction sites on the protein surface, efficiently revealing "hot spots" without requiring the simulation of full drug-like molecules [1].

Q4: When calculating solution-phase thermodynamics using an implicit model, my results are consistently off by about 1.9 kcal/mol. What is the likely cause? You are likely forgetting the concentration correction term, ( \Delta G^o_{conc} ), when transitioning from a gas-phase standard state (1 atm) to a solution standard state (1 mol/L) [7]. This term is calculated as ( RTln(24.5) = 1.89 ) kcal/mol at 298 K and must be added to your computed free energy of solvation [7].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Unphysical distortions in AI-generated drug candidates from 3D-SBDD models.

- Explanation: Advanced 3D-SBDD generative models sometimes produce molecules with distorted substructures (e.g., unreasonable ring formations) to optimize docking scores, compromising drug-likeness and stability [10].

- Solution: Implement a collaborative framework like CIDD that refines initial 3D-SBDD outputs with a Large Language Model (LLM). The LLM can identify and correct chemically unreasonable structures while preserving key interactions, improving both the Reasonable Ratio and binding affinity [10].

Problem: Inaccurate solvation free energies for charged molecules in implicit solvation.

- Explanation: Traditional implicit models use a fixed set of atomic radii to define the cavity, which does not account for the changing electronic environment of an atom (e.g., a neutral vs. a charged oxygen) [7].

- Solution: Use a model with dynamic radii adjustment, such as the DRACO model available in ORCA for CPCM and SMD. DRACO scales atomic radii based on partial charges and coordination numbers, significantly improving the description of charged systems [7].

Problem: Difficulty predicting solubility for novel drug-like molecules.

- Explanation: Traditional methods like the Abraham Solvation Model have limited accuracy, and older machine learning models were hampered by a lack of comprehensive training data [11].

- Solution: Utilize the latest machine learning models trained on large, diverse datasets like BigSolDB. The FastSolv model, for example, provides highly accurate solubility predictions across a wide range of organic solvents and temperatures, aiding in solvent selection for synthesis [11].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Solvation Models in SBDD

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor prediction of binding affinity with key water-mediated interactions. | Implicit models cannot account for specific, structured water molecules [1]. | Use MD to identify conserved "water sites" or apply a hybrid QM/MM-explicit/implicit model [6] [1]. |

| Long, computationally expensive MD simulations to observe binding. | The timescale of binding events increases exponentially with ligand size [1]. | Use cosolvent MD (MDmix) with small probe molecules to rapidly map interaction hot spots [1]. |

| Instabilities in solvation energy during geometry optimization. | Sharp changes in the solvent-accessible surface area with small atomic displacements [7]. | Switch to a solvation model that uses a Gaussian smearing of surface charges (e.g., SURFACETYPE VDW_GAUSSIAN in ORCA's CPCM) for a smoother potential energy surface [7]. |

| High false-positive rate in virtual screening with ML models. | Model bias from training datasets like DUD-E, and neglect of solvation thermodynamics [12]. | Thoroughly validate models and integrate solvation thermodynamics tools like Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) into the analysis pipeline [12]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Mapping Hydration Sites with Explicit-Solvent MD

This protocol uses explicit water molecules to identify structurally and thermodynamically important water molecules on a protein surface, which are critical for understanding ligand binding [1].

- System Setup: Prepare the protein structure in a solvated box using a tool like PDB2PQR. Assign protonation states using software like PROPKA or H++ [4].

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate force field. For standard simulations, use non-polarizable force fields (e.g., TIP3P water model). For higher accuracy, especially with ions, consider a polarizable force field like AMOEBA [6].

- Simulation Run: Perform a molecular dynamics simulation. Good convergence for water site identification is typically achieved in 20-50 ns [1].

- Trajectory Analysis: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., in CPPTRAJ) to the snapshots of water oxygen positions to identify high-occupancy sites, known as Water Sites (WS) or hydration sites [1].

- Characterization: For each WS, calculate:

- Water Finding Probability (WFP): The probability of finding a water molecule in that site.

- R90 Value: The radius containing a water molecule 90% of the time, describing the site's size [1].

- Thermodynamics: Use methods like Inhomogeneous Fluid Solvation Theory (IFST) to calculate entropy and enthalpy contributions [1].

Protocol: Running a Single-Point Energy Calculation with Implicit Solvent in ORCA

This is a fundamental protocol for obtaining the energy of a molecule in solution using a continuum model [7].

- Input File Preparation: Create an input file for your molecule.

- Keyword Selection: Specify the computational method and the implicit solvent model. For a single-point energy calculation with the SMD model in water, the input block would be:

For CPCM with water, use

CPCM(WATER)[7]. - Execution: Run the ORCA calculation.

- Output Interpretation: In the output, locate the "TOTAL SCF ENERGY" section. The solvation free energy components are:

- Electrostatic (ΔGENP): Listed as "CPCM Dielectric."

- Cavity-Dispersion (ΔGCDS): For SMD, this is listed as "SMD CDS (Gcds)." Note that for regular CPCM, this term is often not calculated by default [7].

- Standard State Correction: For solution-phase thermodynamics, remember to add the concentration correction term, ( \Delta G^o_{conc} = 1.89 ) kcal/mol, to the final Gibbs free energy [7].

Protocol: Identifying Binding Hot Spots with Mixed-Solvent MD (MDmix)

This protocol efficiently finds ligandable sites on a protein surface by simulating it in the presence of organic solvent probes [1].

- Probe Selection: Choose an organic solvent probe that mimics common drug motifs. Isopropanol is a common choice as it contains both hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor moieties [1].

- System Setup: Prepare the protein in an aqueous buffer. Replace a small percentage (e.g., 1-5%) of the water molecules with the probe solvent molecules, ensuring the protein remains stable at this concentration [1].

- Simulation Run: Perform a relatively long MD simulation (timescale depends on system size and desired convergence) to allow adequate sampling of probe binding events.

- Density Analysis: Analyze the resulting trajectory to compute the 3D density map of the probe molecules around the protein.

- Site Identification: Regions with high probe density correspond to preferential binding sites or "hot spots." These sites are prime targets for functional groups in drug design [1].

Visualizing Solvation Model Workflows

Model Selection Workflow for SBDD

Solvation-Aware SBVS Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Solvation Modeling in SBDD

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in SBDD | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulation Engine | Runs explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations. | Simulating a protein in a water box to identify high-occupancy water sites (WS) in a binding pocket [1]. |

| ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Package | Performs electronic structure calculations with built-in implicit solvation models. | Calculating the solvation-free energy of a ligand or optimizing its geometry in water using CPCM or SMD [7]. |

| Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) | Analysis Tool | Calculates thermodynamic properties of water molecules from MD trajectories. | Post-processing MD data to compute the entropy and enthalpy of water molecules displaced by a ligand [12]. |

| FastSolv / ChemProp | Machine Learning Model | Predicts solubility of molecules in various organic solvents. | Screening potential solvent systems for the synthesis or formulation of a new drug candidate [11]. |

| Cosolvent Probes (e.g., Isopropanol) | Computational Reagent | Used in MDmix simulations as a proxy for drug fragments. | Efficiently mapping hydrophobic and H-bonding hot spots on a protein surface without simulating full ligands [1]. |

| PDB2PQR / PROPKA | Pre-processing Tool | Prepares protein structures for simulation by adding H atoms and assigning protonation states. | Critical first step in ensuring a realistic protein structure before any MD or docking study [4]. |

The Physical Chemistry of Water-Mediated Protein-Ligand Interactions

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is explicitly modeling water molecules critical for accurate binding affinity predictions in SBDD?

Implicit solvent models, while computationally efficient, often fail to capture critical, specific water-mediated interactions that significantly influence ligand binding. Over 85% of protein-ligand complexes have one or more water molecules bridging the protein and ligand, with a mean of 3.5 molecules per complex [13]. The thermodynamics of solvent reorganization is a key contribution to the complex formation free energy. Accurately predicting the role of these water molecules—whether they are displaced, retained, or form ordered networks during binding—is essential for reliable affinity predictions [1] [13].

FAQ 2: My molecular docking results are inconsistent with experimental binding data. Could solvation effects be the cause?

Yes, this is a common issue. Classical docking often falls short because it does not fully account for the solvent's contribution. The binding site in an unbound protein is not empty; it is occupied by water molecules with well-defined structures and dynamics [1]. Displacing a tightly bound water molecule with a high free energy cost can be unfavorable, even if the ligand forms good direct interactions with the protein. Incorporating explicit water positions and their free energy penalties or gains into the scoring function can dramatically improve the predictive capability of docking [1] [13].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between the first and second hydration shells, and why does the second shell matter?

The first hydration shell refers to water molecules directly interacting with the protein surface. The second hydration shell consists of water molecules that interact with the first shell water molecules and can also influence protein-ligand recognition [13]. The free energy contribution from the water network, including the second shell, is significant but challenging to study. Recent research shows that the second shell of water molecules can be critical for binding affinity and kinetics, and fully considering these effects is vital for accurate predictions in drug discovery [13].

FAQ 4: How can I identify "hot spots" or key interaction sites on my protein target?

Mixed-solvent Molecular Dynamics (MDmix) is a powerful method for this. By simulating the protein in an aqueous solution containing small organic solvent molecules (e.g., isopropanol), you can identify surface regions where these probe molecules bind preferentially [1]. These sites correspond to "hot spots" that provide most of the binding affinity. These probes effectively capture hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding motifs common in drug-like molecules, revealing crucial interaction sites for ligand design [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Correlation Between Calculated and Experimental Binding Free Energies

- Problem: Binding free energy calculations using methods like MM/PBSA result in poor correlation with experimental data.

- Solution: Include explicit water free energy corrections. Research has demonstrated that when MM/PBSA alone was used for systems like CDK2 and Factor Xa, the computed binding free energy showed poor to moderate correlation. However, including a free energy correction for key water molecules greatly improved the calculation's accuracy [13].

- Protocol (MM/PBSA with Water Correction):

- Run a molecular dynamics simulation of the protein-ligand complex with explicit water molecules.

- Identify stable, ordered water molecules at the protein-ligand interface.

- Calculate the free energy of moving these key water molecules from their binding sites to the bulk solvent using a method like VM2 or similar [13].

- Integrate this water free energy term as a correction into your MM/PBSA calculation.

Issue 2: Inability to Identify Stable Water Positions in a Binding Site

- Problem: Crystallographic data may be missing water molecules, or their positions may be unreliable due to low resolution. You need to predict stable hydration sites computationally.

- Solution: Use a hydration site-locating algorithm via molecular dynamics or a grid-based method.

- Protocol (Hydration Sites Locating Algorithm):

- Start with a protein structure (from a crystal structure or homology model) and remove all water molecules and cofactors.

- Define a grid box with a fine spacing (e.g., 0.2 Å) centered on the binding site [13].

- Probe all vacant grid points with a water probe, calculating interaction energies (non-polar, electrostatic, and hydrogen-bonding) between the probe and the protein.

- Identify regions with high probability of finding a water molecule (Water Finding Probability, WFP). These are your hydration sites, which can predict key hydrophilic interaction points for ligands [1] [13].

Issue 3: High Computational Cost of Simulating Ligand Binding/Unbinding

- Problem: Directly simulating the binding of a drug-sized ligand is computationally expensive and time-consuming.

- Solution: Utilize cosolvent molecular dynamics (MDmix) as a more efficient alternative for fragment-based screening and hot spot identification.

- Protocol (MDmix Simulations):

- Simulate the protein in an explicit aqueous solution containing 1-5% of organic solvent probes (e.g., isopropanol, which captures both hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding properties) [1].

- Run a sufficiently long MD simulation (convergence is often achieved in 20-50 ns for water sites) to ensure adequate sampling [1].

- Analyze the simulation trajectories to identify regions with high density and long residence times for the probe molecules. These preferential interaction sites are the "hot spots" for ligand binding [1].

Quantitative Data and Method Comparison

The table below summarizes key quantitative data and properties for analyzing hydration sites from Molecular Dynamics simulations [1].

Table 1: Key Properties and Metrics for Characterizing Hydration Sites from MD Simulations

| Property | Description | Typical Range/Values | Significance in SBDD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Finding Probability (WFP) | Probability of finding a water molecule at a specific site. | Varies between sites | High WFP sites are often displaced by ligand hydrophilic groups to form key interactions [1]. |

| Residence Time | The average time a water molecule remains in a specific site. | 10 ps to > 1 µs [1] | Longer residence times indicate tightly bound waters; displacing them may be energetically costly. |

| Radius (R₉₀) | The radius that contains a water molecule 90% of the time. | Measured in Ångstroms [1] | Defines the spatial extent and size of the hydration site, informing ligand design to fit the site. |

The table below compares different computational methods used for evaluating water effects in protein-ligand recognition.

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Evaluating Water Effects in Protein-Ligand Recognition

| Method | Description | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent MD | Simulates protein, ligand, and water molecules with atomic detail. | Captures full dynamics and entropic effects; identifies hydration sites (WS) [1]. | Computationally expensive; slow convergence for buried water exchange [13]. |

| Mixed-Solvent MD (MDmix) | MD with explicit water and organic solvent probes. | Systematically identifies binding hot spots; more efficient than simulating large ligands [1]. | Uses small probes; binding free energy is non-additive for larger molecules [1]. |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Alchemically transforms molecules to compute free energy differences. | Rigorous and theoretically sound for absolute binding free energy of water [13]. | Very computationally expensive and can be labor-intensive to set up [13]. |

| VM2 Method | A predominant states method using implicit solvent and statistical thermodynamics. | Balanced accuracy and efficiency; can handle multiple water molecules [13]. | Relies on identifying stable conformations; uses implicit solvent model [13]. |

| Geometry-Based Methods (e.g., WarPP) | Uses algorithms to predict water positions from static structures. | Very fast computation. | Often lacks entropy contributions, which are critical for binding [13]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Protocol 1: MM/PBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation with Water Correction

Purpose: To improve the accuracy of binding free energy calculations by incorporating the contribution of explicit water molecules.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex. Parameterize the protein and ligand using appropriate force fields (e.g., AMBER) [13].

- Explicit Solvent MD Simulation: Run a molecular dynamics simulation of the solvated complex to sample conformational states. Ensure the simulation is long enough for the relevant water molecules to exchange or stabilize.

- Identify Key Waters: Analyze the trajectory to locate stable, ordered water molecules at the protein-ligand interface. Look for waters with high residence times and those that form hydrogen-bond bridges.

- Calculate Water Displacement Free Energy: Use a method like the VM2 water-removal algorithm to compute the free energy (ΔG) of moving each key water molecule from its binding site to the bulk solvent [13]. VM2 computes the standard chemical potential of the system with and without the water molecule.

- Standard MM/PBSA: Perform a traditional MM/PBSA calculation on the MD trajectory to get the initial binding free energy estimate (ΔG_MMPBSA).

- Apply Correction: The final, corrected binding free energy (ΔGCorrected) is obtained by summing the initial estimate and the free energy contributions from the displaced water molecules: ΔGCorrected = ΔGMMPBSA + Σ ΔGWater.

Detailed Protocol 2: Hydration Site Analysis via Inhomogeneous Fluid Solvation Theory (IFST)

Purpose: To characterize the structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics of water molecules around a protein binding site.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Apo-Protein MD Simulation: Run a long MD simulation of the protein (without ligand) solvated in a box of explicit water molecules.

- Trajectory Analysis: Extract the positions of water oxygen atoms from thousands of simulation snapshots.

- Clustering for Water Sites: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g, density-based clustering) to the collected water positions. Each cluster defines a "water site" (WS) or "hydration site," characterized by its 3D coordinates [1].

- Property Calculation:

- Water Finding Probability (WFP): The probability of the site being occupied by a water molecule.

- R₉₀: The radius containing a water molecule 90% of the time, defining the site's size.

- Residence Time: The average time a water molecule stays in the site, indicating its stability [1].

- IFST Thermodynamics: Use Inhomogeneous Fluid Solvation Theory to decompose the solvation free energy into energetic and entropic contributions for each water site, providing deep thermodynamic insight [1] [13].

- Ligand Design Application: Use the map of water sites to inform ligand design. Favor ligand functional groups that can displace unstable water sites (high free energy) and maintain or incorporate groups that interact favorably with stable water sites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Studying Water-Mediated Interactions

| Item/Resource | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER) | Simulate the dynamic behavior of proteins, ligands, and explicit water molecules over time. | Sampling conformational ensembles, calculating residence times of water, running MDmix simulations [1] [13]. |

| Free Energy Calculation Tools (e.g., VM2, FEP) | Compute the binding free energy of a ligand or the free energy cost of displacing a water molecule. | Predicting absolute binding affinities, calculating the stability of key hydration sites [13]. |

| Water Analysis Software (e.g., WaterMap, MobyWat, HydraMap) | Identify and characterize hydration sites from MD simulations or static structures. | Mapping "hot spots" and dehydration sites on protein surfaces; guiding ligand optimization [13]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Predict the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule within a protein's binding site. | Initial virtual screening of compound libraries; can be improved by incorporating pre-calculated water sites [14]. |

| Implicit Solvent Models (e.g., PBSA, GBSA) | Approximate the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium for faster energy calculations. | Used in MM/PBSA and as a component in methods like VM2; efficient but misses specific water effects [13]. |

| Cosolvent Probes (in MDmix) | Small organic molecules (e.g., isopropanol, acetonitrile) used to mimic chemical features of drugs. | Experimentally mapping protein surface hot spots by identifying preferential binding locations [1]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of initial protein structures for simulations; provides experimental data on crystallographic water positions [13]. |

FAQs: Understanding and Troubleshooting Solvation Analysis

What are the key thermodynamic descriptors for quantifying solvation effects in SBDD?

The table below summarizes the key computational descriptors and parameters used to quantify solvation effects, along with the methods used to obtain them.

| Descriptor/Parameter | Computational Method | Significance in SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| Solvation Free Energy (ΔGsolv) | 3D-RISM, MD Free Energy Perturbation, QM/Continuum Models [15] | Predicts solubility, permeability, and binding affinity [15]. |

| Partial Solvation Parameters (PSPs) | Quantum Mechanics & QSPR/LSER approaches [16] | Molecular descriptors for predicting solvation properties and phase equilibria [16]. |

| Water Finding Probability (WFP) | Explicit Solvent MD Simulations [1] | Identifies high-occupancy hydration sites on a protein surface; spots likely for displacement by ligand [1]. |

| Enthalpy (ΔH) & Entropy (ΔS) of Hydration | Inhomogeneous Fluid Solvation Theory (IFST) applied to MD trajectories [1] | Decomposes free energy into energetic (ΔH) and disorder (ΔS) components for a detailed view of solvation [1]. |

| Preferential Interaction Sites | Mixed-Solvent MD (MDmix) [1] | Identifies "hot spots" on a protein surface that preferentially bind organic solvent probes, indicating where drug-like fragments might bind [1]. |

How do I choose the right method for predicting pKain drug-like molecules?

Selecting a pKa prediction method involves trade-offs between accuracy, speed, and chemical space coverage. The table below compares the primary approaches.

| Method | Typical Applications | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | Novel/Exotic functional groups; high-accuracy studies [17] | High physical rigor; good extrapolation to new chemistries [17] | Computationally expensive; slower [17] |

| Explicit-Solvent Free-Energy Simulations | Protein residue pKa; cases where solvent effects are dominant [17] | Explicitly models solvent; high accuracy for complex environments [17] | Very computationally expensive; requires significant expertise [17] |

| Data-Driven & Machine Learning (ML) | High-throughput virtual screening of drug-like molecules [17] | Very fast; high accuracy for well-represented chemical classes [17] | Unreliable for exotic structures; data-hungry [17] |

| Fragment/Group-Based | Rapid estimation for standard functional groups [17] | Extremely fast and accurate within domain [17] | Poor generalization; misses through-space effects [17] |

| Hybrid Approaches | Balancing speed and physical insight [17] | Incorporates physical bias; more robust than pure ML [17] | Speed depends on underlying physical model [17] |

My MD simulations of ligand binding are not converging. What could be wrong?

Insufficient simulation time is a common cause. Observing full binding/unbinding events is computationally expensive and has an exponential relationship with molecular size [1]. Furthermore, using a single, static protein structure from a cryogenic crystal might not capture the necessary flexibility. Consider these steps:

- Extended Sampling: Run multiple, longer simulations or use enhanced sampling techniques.

- Incorporating Flexibility: Use methods like induced-fit docking or ensemble docking from MD snapshots to account for protein motion [4].

- Solvent Representation: The use of explicit solvent is crucial, but also computationally demanding. For some properties, a well-validated implicit solvent model can be a useful alternative [8].

Why do my computational binding affinity predictions disagree with experimental data?

This is a common challenge, often stemming from an incomplete treatment of solvation. Key factors to check include:

- Displacement of Key Water Molecules: The thermodynamics of binding are heavily influenced by the displacement of water molecules from the binding site. Failure to identify and account for high-energy ("unhappy") waters can lead to significant errors [1]. Using tools like WaterMap or 3D-RISM can help characterize these sites [4].

- Protonation States: The protonation states of key protein residues and the ligand itself can change between solvated and bound states. Use tools like PROPKA [4] to predict pKa values and ensure states are appropriate for the binding context.

- Entropic Contributions: Binding involves complex trade-offs in entropy from the ligand, protein, and solvent. Methods like Molecular Dynamics with Mixed Solvents (MDmix) can help probe these contributions [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Binding Hot Spots Using Mixed-Solvent Molecular Dynamics (MDmix)

Purpose: To identify key interaction sites ("hot spots") on a protein surface by simulating the system in the presence of organic solvent probes, which mimic functional groups of drug-like molecules [1].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Obtain a high-resolution structure of the protein target (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM).

- Prepare the protein using a standard workflow (e.g., with Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard or a similar tool). This includes adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and optimizing hydrogen bonds [4].

- Solvate the protein in a pre-equilibrated box containing a mixed solvent, typically water with 1-5% of an organic probe like isopropanol. Isopropanol is a common choice as it captures both hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interactions [1].

- Simulation:

- Run an extended molecular dynamics simulation (often tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) using a package like AMBER, GROMACS, or OpenMM.

- Ensure the simulation is long enough for the organic probes to adequately sample the protein surface. Good convergence for solvent structure is often achieved in 20–50 ns [1].

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Analyze the resulting trajectory to identify regions on the protein surface where the organic solvent probes accumulate preferentially.

- Calculate the spatial density of the probe molecules around the protein. These high-density regions are the "hot spots" [1].

- Application to Drug Discovery:

- Use the identified hot spots to guide fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) or to inform molecular docking. The hot spots indicate where chemical functional groups from a potential drug molecule are likely to form favorable interactions.

Protocol 2: Calculating Solvation Free Energy Using 3D-RISM

Purpose: To predict the solvation free energy (SFE) of a small molecule in various solvents, a key property for predicting solubility, logP, and membrane permeability [15].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Ligand Preparation:

- Generate a 3D structure of the solute (drug-like molecule) and optimize its geometry using quantum chemistry (e.g., DFT) or molecular mechanics.

- 3D-RISM Calculation:

- Set up the 3D-RISM calculation by defining the solute molecule and the solvent (e.g., water, octanol). The 3D-RISM theory is an integral equation theory that computes the 3D structure of the liquid around the solute [15].

- Run the 3D-RISM simulation to obtain the spatial density distributions of the solvent sites (e.g., oxygen and hydrogen for water) around the solute.

- SFE Calculation:

- Calculate the SFE by integrating the solute-solvent interaction energy over the solvent distribution. The Kovalenko-Hirata (KH) closure is a common approximation used for this purpose [15].

- Multi-Solvent Prediction (Optional):

- The SFE in water, or a set of hydration thermodynamic descriptors from 3D-RISM, can be used as input features for a machine learning (ML) model. This ML model can then be trained to predict SFEs in a wide range of organic solvents, increasing efficiency [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

| Reagent / Software Solution | Function in Solvation Analysis |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines (AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM, OpenMM) | Simulate the motion of protein-ligand systems in explicit solvent, providing atomic-level detail of solvation dynamics [1] [17]. |

| 3D-RISM Software | Calculates the 3D structure of a liquid solvent around a solute, enabling efficient computation of solvation free energies and other thermodynamic descriptors [15]. |

| Continuum Solvation Models (e.g., ALPB, GB/SA, COSMO-RS) | Provide a faster, approximate method for calculating solvation effects by treating the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, rather than explicit molecules [8] [17]. |

| pKa Prediction Tools (e.g., Jaguar, Epik, ACD/pKa) | Determine the acid dissociation constant, which is critical for predicting the correct protonation state and charge of a ligand in solution, dramatically affecting solvation and binding [17]. |

| Protein Preparation Suites (e.g., Maestro Protein Prep Wizard, WebPDB) | Prepare protein structures from the PDB for simulation or docking, including assigning bond orders, adding H atoms, and optimizing protonation states [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How does neglecting solvation specifically impact virtual screening results in drug discovery? In Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS), solvation effects are critical during the binding event as a ligand must first displace water molecules from the protein's binding pocket. Neglecting this desolvation process can lead to a significant overestimation of binding affinity. This is because the energetic penalty for dehydrating the ligand and the protein binding site is not accounted for. Accurate prediction requires estimating the free energy changes that accompany this desolvation [4] [18].

2. What are "non-additive solvation effects" and why are they a pitfall? A common assumption is that a molecule's total solvation free energy is the sum of its individual parts. However, this additivity often fails. When two substituent groups on a molecule are close together, their solvation shells can overlap and interact, leading to non-additive behavior. For instance, if two -OH groups are adjacent, they might form an intramolecular hydrogen bond, making the molecule behave as if it only has one -OH group from a solvation perspective. The error from assuming additivity can be as large as 1.4 kcal/mol or more, which is enough to render predictions quantitatively useless [18].

3. What is the key difference between implicit and explicit solvent models, and when is each appropriate? The choice between implicit and explicit models is a fundamental one.

- Implicit Models (e.g., PCM, GB/SA): Treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium. They are computationally efficient and good for estimating electrostatic contributions to solvation and performing high-throughput screening [19] [20].

- Explicit Models: Treat each solvent molecule individually. They are computationally expensive but are essential for capturing specific, directional interactions like hydrogen bonding, shared solvation shells, and the role of key water molecules in active sites. They are necessary for modeling reaction mechanisms and accurate binding kinetics [19] [20] [18].

4. How can solvation affect the binding kinetics of a drug candidate? Solvation and desolvation are key drivers of binding kinetics (kon and koff). Molecular dynamics simulations show that the transition state for unbinding can be located in two key areas:

- Near the bound state: The barrier is enthalpic, requiring the breaking of strong interactions with the protein.

- In the vestibule area: The barrier is entropic, linked to solvent reorganization and the cost of (re)hydrating the ligand and protein. Neglecting explicit water dynamics makes predicting residence time (1/koff) very difficult [21].

5. Why is modeling "mutual polarization" between solute and solvent so important? Polarization is not a one-way street. When a solute's electron density changes (e.g., upon photoexcitation), it polarizes the surrounding solvent. This rearranged solvent, in turn, repolarizes the solute. This mutual polarization is a dominating factor for accurately predicting properties like absorption spectra. Standard non-polarizable force fields cannot capture this effect, leading to inaccurate predictions of spectral peaks and shapes [20].

Experimental Protocols & Troubleshooting

Protocol 1: Incorporating Solvation in Structure-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the key steps for preparing a protein target for SBVS, highlighting where solvation is most critical [4].

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure from X-ray, NMR, or homology modeling.

- Assign Protonation States: Use software like PROPKA or H++ to determine the correct protonation states of amino acid residues at physiological pH. Incorrect states will distort electrostatics.

- Handle Water Molecules: This is a critical decision point. Use methods like WaterMap, 3D-RISM, or JAWS to identify structurally important "water molecules" that should be retained in the binding site as part of the protein structure.

- Relieve Steric Clashes: Perform a gentle energy minimization of the protein structure while restraining heavy atoms to fix any unrealistic clashes.

Ligand Library Preparation:

- Generate accessible tautomeric and ionization states for each compound in the library.

- Assign proper stereochemistry and formal charges.

Docking and Post-Processing:

- Perform molecular docking with a program that can account for, or be parameterized for, solvent effects.

- During post-processing, visually inspect top-scoring hits to check if key water-mediated interactions are present or if the pose suggests unfavorable desolvation.

Protocol 2: Assessing Solvation Contributions to Binding Kinetics using suMetaD

This protocol uses advanced molecular dynamics to simulate the role of solvation in ligand unbinding/binding [21].

System Setup:

- Start with a ligand-protein complex embedded in an explicit solvent box.

- Equilibrate the system using standard MD.

Define Collective Variables (CVs):

- Select CVs that describe the unbinding path. A common choice is the distance between the ligand and the protein's binding site center of mass. Crucially, a second CV should be a measure of solvation, such as the number of water molecules in the binding site or around the ligand.

Run Supervised MD (SuMD) and Metadynamics (MetaD):

- Use the SuMD method to simulate the ligand unbinding and binding events, guiding the process along the pre-defined CVs.

- Employ Well-Tempered Metadynamics to reconstruct the free energy surface of the entire process.

Analysis:

- Identify the transition state (the highest energy barrier).

- Analyze the conformation and, most importantly, the solvation structure at this state. A transition state in the vestibule is often characterized by an entropic barrier linked to solvent behavior.

Quantitative Data on Solvation Effects

Table 1: Experimental Evidence of Non-Additive Solvation Free Energies

| Molecular System | Observed Phenomenon | Energetic Impact | Physical Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xylenol Isomers [18] | Different spatial arrangement of identical groups (methyl and hydroxyl) | ΔΔG~solv~ = 1.4 kcal/mol | Steric hindrance prevents optimal H-bonding with water for one isomer. |

| Dihydroxybenzene [18] | Two adjacent -OH groups vs. two separated -OH groups | The adjacent groups contribute ~0 kcal/mol vs. -5.7 kcal/mol each for separated groups | Intramolecular H-bonding prevents favorable interaction with water. |

| Dinitrate Alkyl Chain [18] | Two nitrate groups close together vs. far apart | Each nitrate contributes less than its individual solvation energy | Crowding and sharing of solvation shells between the two groups. |

Table 2: Comparison of Solvation Modeling Approaches

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit (Continuum) [19] [18] | Solvent as dielectric continuum | Computationally fast; Good for electrostatic effects | Misses specific H-bonds, non-additivities, and solvent structure | High-throughput screening; Initial pose generation |

| Explicit (Classical FF) [19] [20] | Every solvent molecule modeled | Captulates H-bonding and solvent structure; Allows for dynamics | Computationally expensive; Force field dependence | MD simulations; Binding kinetics studies |

| Explicit (Polarizable FF) [20] | Explicit solvent with polarizable sites | Captures mutual polarization | Even more computationally expensive; Parameterization is complex | Modeling spectroscopy; Systems with strong polarization |

| QM/MM [20] | QM for solute, MM for solvent | High accuracy for solute electronic structure | Costly; Limited time/length scales | Studying reaction mechanisms in solution |

| Machine-Learned Potentials (MLPs) [19] | ML surrogate for quantum methods | Near-quantum accuracy; lower cost | Data-intensive training; Transferability challenges | Accurate free energy calculations; Complex reactive systems |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Software and Methods for Solvation Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Solvation Modeling |

|---|---|

| PROPKA / H++ [4] [22] | Predicts pK~a~ and protonation states of protein residues for proper electrostatic setup. |

| WaterMap / 3D-RISM [4] [22] | Identifies the location and thermodynamic properties of ordered water molecules in binding sites. |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) [20] [22] | An implicit solvation model for efficient calculation of electrostatic solvent effects in QM. |

| Generalized Born (GB) [18] | A faster, approximate implicit model often used in molecular mechanics. |

| AMOEBA Force Field [20] | A polarizable force field for explicit solvent simulations that captures mutual induction. |

| Effective Fragment Potential (EFP) [20] | A quantum-mechanically derived method for explicitly modeling solvent molecules with high accuracy without empirical parameters. |

| Metadynamics [21] | An enhanced sampling MD technique to simulate rare events like ligand (un)binding and map the free energy landscape. |

Workflow Visualization

Computational Strategies for Solvation: From Continuum Models to AI

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the PCM and GB-SA implicit solvent models? The Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) and the Generalized Born-Surface Area (GB-SA) model are both implicit solvent models but employ different physical approaches. PCM treats the solvent as a polarizable continuum characterized by its dielectric constant and solves the Poisson-Boltzmann equation numerically to compute electrostatic solvation energies [23]. In contrast, the GB-SA model is an approximation to the Poisson-Boltzmann theory. It uses a Generalized Born equation to calculate the electrostatic component of solvation, which is then combined with a non-polar contribution estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [23]. GB-SA is generally computationally faster, while PCM can be more accurate but demands greater computational resources.

Q2: In what scenarios is it particularly crucial to account for solvation free energy in binding affinity calculations? Calculating solvation free energy becomes absolutely essential in cases involving ionized fragments or charged molecules [23]. The transfer of a ligand from an aqueous solvent to a protein binding pocket involves significant desolvation penalties, especially for charged groups. Neglecting these effects can lead to severe inaccuracies in predicting binding affinity. Furthermore, the solvent plays a critical role in the kinetics of binding and unbinding; for instance, transition states located in protein vestibules can have kinetic bottlenecks dominated by entropic effects linked to solvent behavior [21].

Q3: My FMO/PCM binding affinity predictions are inconsistent with experimental data. Which energy terms should I investigate? The Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method reliably calculates gas-phase potential energy, but binding affinity is influenced by additional terms [23]. We recommend you systematically check the following components:

- Solvation Free Energy: Ensure your PCM (or other implicit solvent model) calculations are configured correctly for your system, particularly regarding the dielectric constants for the solvent and solute.

- Deformation Energy: This is the energy penalty required for the ligand to adopt its bioactive conformation from its lowest-energy free state. Incorporating this term has been shown to enhance the precision of FMO predictions [23].

- Entropy: Although often computationally expensive to include (e.g., via the Interaction Entropy method), the entropy contribution to binding can be significant. While sometimes omitted for efficiency, its inclusion can provide a performance boost [23].

Q4: Are there modern, efficient alternatives to traditional QM/MM solvent models for large-scale virtual screening? Yes. For scenarios requiring high throughput, such as screening massive compound libraries, structure-free approaches are emerging. For instance, models like BIND use protein language models and molecular graphs to achieve screening power comparable to state-of-the-art structure-based models but with dramatically reduced computational time and without requiring 3D protein structures [24]. Similarly, hybrid AI frameworks that combine 3D-SBDD with Large Language Models (LLMs) can refine molecules to improve drug-likeness while maintaining binding affinity [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inaccurate Solvation Energy Calculation for Charged Ligands

- Symptoms: Systematic overestimation or underestimation of binding affinity for charged molecules; poor correlation with experimental results for a series of ionizable compounds.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Verify Model Parameters: Confirm that the internal and external dielectric constants used in your PCM or GB-SA calculation are appropriate for your protein-ligand system. Typical values are 1-4 for the solute and ~80 for the solvent (water).

- Check Cavity Definition: In PCM, the results are sensitive to the definition of the molecular cavity. Ensure the cavity is neither too small (underestimating solvation) nor too large (overestimating it). Experiment with different cavity definitions (e.g., using different atomic radii sets).

- Cross-validate with a Different Model: Run the same system using a different implicit solvent model (e.g., compare PCM with GB-SA or the PM7/COSMO model [23]). If both models show the same large deviation, it strengthens the evidence that the solvation term is the source of error.

- Consider Explicit Solvent: For highly charged systems, a hybrid QM/MM molecular dynamics (MD) simulation with explicit water molecules might be necessary to capture specific solvent effects, such as tightly bound water molecules in the active site, though this is computationally expensive [21].

Problem: High Computational Cost of PCM in FMO Calculations

- Symptoms: FMO calculations with PCM become prohibitively slow for large protein-ligand systems, hindering research progress.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Explore Semi-Empirical Methods: Consider using a lower level of theory for the PCM calculation. The semi-empirical PM7 method combined with the COSMO solvation model has demonstrated good performance in calculating solvation energy changes during binding and offers a favorable compromise between speed and accuracy [23].

- Leverage Linear Scaling Methods: Investigate if your computational software supports linear-scaling algorithms for the PCM computation itself. Modern implementations are designed to handle large systems more efficiently.

- Evaluate the Necessity: For initial screening or less critical calculations, a well-parameterized GB-SA model might provide a sufficiently accurate solvation energy estimate at a fraction of the computational cost, allowing you to reserve full PCM for final, high-accuracy predictions on top candidates [23].

Problem: Discrepancy Between Predicted and Experimental Binding Kinetics

- Symptoms: Your model accurately predicts binding affinity (KD) but fails to replicate experimental association (kon) or dissociation (koff) rates.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Focus on the Unbinding Pathway: Binding kinetics are determined by the energy landscape along the entire binding/unbinding pathway, not just the bound state. Implicit models focused on a single snapshot are limited here.

- Implement Enhanced Sampling MD: Use methods like metadynamics or supervised MD (suMetaD) to simulate the ligand unbinding process [21]. These techniques can identify transition states and the role of water in creating enthalpic or entropic barriers.

- Analyze Solvent Bottlenecks: These MD simulations can reveal if the kinetic bottleneck is an enthalpic barrier (e.g., breaking strong ligand-protein interactions) near the bound state or an entropic barrier (e.g., linked to solvent ordering/disordering) in a vestibule or channel [21].

Performance Data and Methodologies

Comparative Performance of Implicit Solvent Methods in FMO

The table below summarizes the performance of various implicit solvent methods when integrated into the FMO framework for binding affinity prediction on a benchmarked dataset [23].

Table 1: Performance of FMO-based binding affinity calculation methods incorporating different implicit solvent and energy terms.

| Method Name | Linear Fit Form Description | Key Solvation Model | Additional Terms | Pearson Correlation (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMO | Gas-phase potential energy only | None | None | 0.62 |

| FMO_PBSA | Adds solvation free energy | PBSA | - | [Data from citation:1] |

| FMO_GBSA | Adds solvation free energy | GBSA | - | [Data from citation:1] |

| FMO_COSMO | Adds solvation free energy | PM7/COSMO | - | [Data from citation:1] |

| FMO_PCM | Adds solvation free energy | PCM | - | [Data from citation:1] |

| FMO_SMD | Adds solvation free energy | SMD | - | [Data from citation:1] |

| FMOCOSMOSE | Adds solvation and deformation | PM7/COSMO | Ligand Strain | Improved performance [23] |

| FMOScore | Optimized linear combination | PM7/COSMO | Ligand Strain | Good performance vs. FEP+, MM/PB(GB)SA [23] |

Detailed Protocol: FMOScore for Binding Affinity Prediction

The following workflow outlines the methodology for the FMOScore, which integrates FMO with implicit solvation and other key energy terms [23].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex, ideally from a reliable crystal structure or a well-validated docking pose.

- Perform standard structure preparation steps: add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states for ionizable residues (considering the pH and binding site environment), and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

FMO Calculation:

- Fragment Partitioning: Divide the entire protein-ligand system into smaller fragments. The ligand is typically treated as a single fragment.

- Quantum Mechanical Calculation: Perform ab initio QM calculations (e.g., at the HF/STO-3G level) on the fragmented system using the FMO method to obtain the gas-phase interaction energy (ΔE_int).

Solvation Free Energy (ΔG_solv):

- Calculate the solvation free energy for the complex, the protein alone, and the ligand alone using an implicit solvent model. The FMOScore method recommends the PM7/COSMO model for its efficiency and performance [23].

- The change in solvation upon binding is computed as: ΔΔGsolv = ΔGsolv(complex) - ΔGsolv(protein) - ΔGsolv(ligand).

Ligand Deformation Energy (ΔE_def):

- Geometry optimize the ligand in its free state (unbound) to find its minimum energy conformation.

- Calculate the single-point energy of the ligand in its free-state conformation and its bound-state conformation (extracted from the complex).

- The deformation energy is the difference: ΔEdef = Eligand(bound conformation) - E_ligand(free conformation).

Entropy Contribution (-TΔS):

- This term is often calculated using methods like Interaction Entropy (IE) or normal mode analysis. However, due to high computational cost, it may be omitted in some implementations, with the understanding that this may limit accuracy [23].

Linear Regression & Scoring:

- The final binding free energy (ΔGpred) is computed using a linearly fitted function of the calculated terms [23]: *ΔGpred = a * ΔEint + b * ΔΔGsolv + c * ΔE_def + d * (-TΔS) + ...*

- The coefficients (a, b, c, d) are obtained by fitting the model to a dataset of known binding affinities.

FMOScore Calculation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and resources used in modern SBDD for handling solvation effects.

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for implementing implicit solvation models.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in SBDD | Relevance to Solvation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMO Software | Quantum Mechanical Method | Enables ab initio QM calculations on large biomolecules by dividing them into fragments. | Provides accurate gas-phase interaction energies; can be coupled with implicit solvent models like PCM. |

| Implicit Solvent Modules | Computational Model | Calculate the free energy of solvation for molecules. | Core implementations of models like PCM, GB-SA, and SMD within QM or MD software packages. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Simulation Software | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Allows for explicit solvent simulations and advanced sampling (e.g., metadynamics) to study solvation/desolvation. |

| DUD-E / DEKOIS 2.0 | Benchmark Dataset | Provides decoy molecules and known binders for specific protein targets. | Used for validating the screening power and accuracy of scoring functions, including solvation models. |

| PDBBind | Curated Database | A comprehensive collection of protein-ligand complex structures and binding affinities. | Serves as a primary source for training and testing empirical scoring functions and machine learning models. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the advantage of using an explicit solvent model over an implicit one in molecular dynamics simulations? Explicit solvent models, which represent individual water molecules, compute more accurate results compared to implicit models, which treat the solvent as a continuous medium. Implicit models are less accurate because they cannot capture specific, atomic-level interactions like hydrogen bonding between water and the solute. Explicit solvents are crucial for studying processes where water structure and dynamics play a direct role, such as ligand binding and protein folding [25].

Q2: My GROMACS simulation fails with an "Out of memory" error. What are the most common causes and solutions? This error occurs when the program attempts to allocate more memory than is available. Common causes and solutions include [26]:

- Cause: The simulation system is too large (e.g., due to an error in box size definition).

- Solution: Check the system size, particularly when using

gmx solvate, as confusion between Ångström (Å) and nanometers (nm) can lead to a box 10³ times larger than intended. - Cause: The analysis involves too many atoms or too long a trajectory.

- Solution: Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis or the length of the trajectory being processed.

- Cause: Insufficient physical memory.

- Solution: Use a computer with more RAM or install more memory.

Q3: How can cryogenic-temperature protein structures distort water networks, and what tools can correct this? Techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy use freezing temperatures, which can distort how water molecules appear in protein structures. These "structural artifacts" artificially increase the number of observed water molecules. The ColdBrew computational tool addresses this by leveraging data on protein-water networks to predict the likelihood of water molecule positions at higher, more physiologically relevant temperatures. This is particularly valuable for identifying key waters within drug-binding sites [27].

Q4: What are the key steps in preparing a system for an explicit solvent MD simulation? A standard protocol involves [25]:

- System Setup: Placing the solute (e.g., a protein-ligand complex) in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP4P water model) with a defined buffer size (e.g., 10 Å).

- Ionic Conditions: Adding ions to mimic physiological conditions (e.g., 0.15 M salt) and adding counter-ions to neutralize the system's total charge.

- Energy Minimization: Running an energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes or unrealistic geometry in the initial structure, using a convergence threshold (e.g., 1.0 kcal/mol/Å).

- Production MD: Running the simulation with a specific force field (e.g., OPLS-2005) for the desired time (e.g., 100 ns) while saving trajectory frames at set intervals (e.g., every 10 ps).

Q5: How do I resolve the "Residue not found in residue topology database" error in GROMACS's pdb2gmx?

This error means the force field you selected does not contain a definition for the residue 'XXX' in its database. Solutions include [26]:

- Check if the residue name in your PDB file matches the name used in the force field's database and rename it if necessary.

- If the residue is truly missing, you cannot use

pdb2gmxdirectly. You will need to parameterize the molecule yourself (a complex task), find a pre-existing topology file, or use a different force field that includes parameters for this residue.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation Crashes Due to "Long Bonds and/or Missing Atoms"

- Description: During the

pdb2gmxstep, the program encounters impossibly long bond lengths, often leading to a failure in generating the topology. - Diagnosis: This is frequently caused by missing atoms in the initial PDB file. The screen output from

pdb2gmxwill typically indicate which specific atom is missing [26]. - Solution: Check your input PDB file for missing atoms. Many PDB files from experiments contain

REMARK 465andREMARK 470entries, which explicitly list missing atoms. These atoms must be modeled back in using specialized software before runningpdb2gmx, as GROMACS itself does not have a tool for this [26].

Problem: "Invalid order for directive" Error in grompp

- Description: The molecular dynamics preprocessor

gromppfails because the directives in your topology (.top) or include (.itp) files are in an incorrect sequence. - Diagnosis: The topology file has a strict required order. A common error is placing a

[ position_restraints ]directive or an#includestatement for a position restraint file in the wrong location [26]. - Solution: Ensure the directives in your topology files follow the correct hierarchy. For position restraints, the

#includestatement for a restraint file must be placed immediately after the[ moleculetype ]directive for that specific molecule. Do not cluster all restraint includes at the top or bottom of the topology file [26].

Diagram 1: Fixing an "Invalid order for directive" error in grompp.

Problem: Instability in Simulations Involving Covalent Probes

- Description: Simulations of covalent protein-ligand complexes become unstable, or the reaction mechanism is not accurately captured.

- Diagnosis: Covalent binding involves multiple distinct states (non-covalent complex, near-attack conformation, transition state, product), each with different energy and geometry requirements. Standard force fields and simulation setups may not handle these transitions correctly [28].