Ligand-Based Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), a cornerstone computational method in modern drug discovery.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), a cornerstone computational method in modern drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that underpin LBVS, detailing key methodological approaches from traditional shape-based and pharmacophore methods to the latest AI and machine learning integrations. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, offering practical troubleshooting guidance. Furthermore, it presents a comparative analysis of current tools and validation protocols, evaluating performance through established metrics and benchmarks to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively implement and critically assess LBVS campaigns.

The Core Principles and Evolution of Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) represents a cornerstone computational methodology in modern drug discovery, employed to efficiently identify novel candidate compounds by leveraging the known biological activity of existing ligands. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of LBVS, delineating its fundamental principles, core methodologies, and practical implementation protocols. Within the broader context of virtual screening overview research, we frame LBVS as a knowledge-driven approach that is indispensable when three-dimensional structural data of the biological target is unavailable or incomplete. The document details quantitative performance data, provides visualized experimental workflows, and catalogues essential research tools, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in computational lead identification.

In the modern drug discovery pipeline, virtual screening (VS) stands as a critical computational technique for evaluating extensive libraries of small molecules to pinpoint structures with the highest potential to bind a drug target, typically a protein receptor or enzyme [1]. Virtual screening has been defined as "automatically evaluating very large libraries of compounds" using computer programs, serving to enrich libraries of available compounds and prioritize candidates for synthesis and testing [1]. This approach is broadly categorized into two paradigms: structure-based virtual screening (SBVS), which relies on the 3D structure of the target protein, and ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), the focus of this document [2].

LBVS is a computational strategy utilized when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or uncertain [3]. Instead, it operates on the principle that compounds structurally or physicochemically similar to known active molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activity [2]. This methodology exploits collective information contained within a set of structurally diverse ligands that bind to a receptor, building a predictive model of receptor activity [1]. Different computational techniques explore the structural, electronic, molecular shape, and physicochemical similarities of different ligands to imply their mode of action [1]. Given that LBVS methods often require only a fraction of a second for a single structure comparison, they allow for the screening of massive chemical databases in a highly time- and cost-efficient manner, even on standard CPU hardware [4]. Consequently, LBVS serves as a valuable tool for identifying close analogues of known active compounds and for conducting initial filtering of ultra-large virtual databases [4].

Core Methodologies in Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

The effectiveness of LBVS hinges on several well-established computational techniques. The choice of method often depends on the quantity and quality of known active ligands and the specific goals of the screening campaign.

Molecular Similarity and Fingerprint-Based Screening

At the heart of many LBVS approaches lies the concept of molecular similarity, typically quantified using molecular fingerprints [4]. Fingerprints are bit vector representations of molecular structure, encoding the presence or absence of specific chemical features or substructures. The similarity between two molecules is then calculated by comparing their fingerprint vectors using a similarity coefficient, with the Tanimoto coefficient being the most common [4]. A widely used fingerprint type is the Morgan fingerprint (often referred to as ECFP - Extended Connectivity Fingerprint), which is a circular fingerprint capturing the molecular environment around each atom up to a specified radius [4]. The VSFlow tool, for instance, supports a wide range of RDKit-generated fingerprints, including Morgan, RDKit, Topological Torsion, and Atom Pairs fingerprints, as well as MACCS keys, and allows for the use of multiple similarity measures such as Tversky, Cosine, Dice, Sokal, Russel, Kulczynski, and McConnaughey similarity [4].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore model represents an ensemble of steric and electronic features that are necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with a biological target to trigger or block its biological response [1]. In essence, it is an abstract definition of the essential functional groups and their relative spatial arrangement required for activity. Pharmacophore models can be generated from a single active ligand or, more robustly, by exploiting the collective information from a set of structurally diverse active compounds [1]. The model is subsequently used as a 3D query to screen compound databases for molecules that share the same spatial arrangement of critical features, even if their underlying molecular scaffolds differ.

Shape-Based Screening

Shape-based similarity approaches are established as important and popular virtual screening techniques [1]. These methods are based on the premise that a molecule must possess a complementary shape to the bioactive conformation of a known active ligand to fit into the same binding site. Techniques like ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) use Gaussian functions to define molecular volumes and rapidly overlay and score candidate molecules against a reference shape [1]. The selection of the query conformation is less critical than the selection of the query compound itself, making shape-based screening ideal for ligand-based modeling when a definitive bioactive conformation is unavailable [1]. As an improvement, field-based methods incorporate additional fields influencing ligand-receptor interactions, such as electrostatic potential or hydrophobicity, providing a more comprehensive similarity assessment [1].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling constitutes a different approach, focusing on building predictive correlative models [1]. QSAR models use computational statistics to derive a mathematical relationship between quantitative descriptors of molecular structure (e.g., logP, polar surface area, molecular weight, vibrational frequencies) and a defined biological activity [1]. This model can then predict the activity of new, untested compounds. While Structure-Activity Relationships (SARs) treat data qualitatively and can handle structural classes with multiple binding modes, QSAR provides a quantitative framework for prioritizing compounds for lead discovery [1].

Table 1: Core Methodologies in Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Input Requirements | Common Tools/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Similarity | Compounds with similar structures have similar activities [2]. | One or more known active ligand(s). | Molecular fingerprints (ECFP, FCFP), Tanimoto coefficient [4]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Essential functional features and their 3D arrangement dictate activity [1]. | Multiple structurally diverse active ligands (preferred). | Pharmacophore query features (donor, acceptor, hydrophobic, etc.) [1]. |

| Shape-Based Screening | Complementary molecular shape is critical for binding [1]. | A 3D conformation of an active ligand. | ROCS, FastROCS, Gaussian molecular volumes [1]. |

| QSAR | A mathematical model correlates molecular descriptors to biological activity [1]. | A set of compounds with known activity values. | ML algorithms, molecular descriptors (logP, PSA, etc.) [1]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A typical LBVS campaign follows a structured workflow, from data preparation to hit identification. The following protocols detail key stages of this process.

Compound Library Preparation and Standardization

The first step involves preparing the virtual compound library to ensure chemical consistency and integrity, which is crucial for the accuracy of subsequent similarity calculations.

- Data Collection: Gather chemical structures from various sources such as in-house repositories, commercially available compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine), or public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) [5] [6].

- Standardization: Process all molecules through a standardization pipeline to neutralize charges, remove salts and counterions, and generate canonical tautomers. This can be achieved using tools like the MolVS library implemented within open-source toolkits such as RDKit [4]. The

preparedbtool in VSFlow, for example, automates this standardization. - Format Conversion: Ensure all molecular structures are converted into a consistent format for processing (e.g., SMILES, SDF). Tools like RDKit or Open Babel are commonly used for this purpose [5].

- Descriptor/Fingerprint Generation: Calculate molecular descriptors or generate the chosen fingerprint (e.g., Morgan fingerprint with a specified radius and bit length) for every molecule in the standardized database. This pre-computation significantly speeds up the screening process [4].

Protocol for Fingerprint-Based Similarity Screening

This protocol uses a known active compound as a query to find structurally similar molecules in a prepared database.

- Query Definition: Select a known active ligand (the "query") and represent it in an appropriate format (e.g., SMILES).

- Fingerprint Generation: Generate the molecular fingerprint for the query molecule using the same method and parameters (e.g., Morgan fingerprint, radius 2, 2048 bits) applied to the database compounds during the preparation phase.

- Similarity Calculation: For each molecule in the pre-processed database, calculate the similarity between its fingerprint and the query fingerprint. The Tanimoto coefficient is the most widely used metric for this purpose.

- Ranking and Selection: Rank all database compounds based on their calculated similarity score to the query. Compounds exceeding a user-defined similarity threshold are selected as potential hits for further evaluation.

Protocol for Shape-Based Screening with VSFlow

The open-source tool VSFlow provides a integrated workflow for shape-based screening, which combines molecular shape with pharmacophoric features [4].

- Conformer Generation for Query: If starting from a 2D query structure, generate multiple 3D conformers using a method like RDKit's ETKDGv3. Optimize these conformers with a forcefield like MMFF94 [4].

- Pre-screened Database: Utilize a database that has been pre-processed with the

preparedbtool from VSFlow, which includes generating multiple conformers for each database molecule [4]. - Shape Alignment and Scoring: Align conformers of the query molecule to all conformers of each database molecule using the RDKit Open3DAlign functionality. For every conformer pair, calculate the shape similarity using a metric like TanimotoDist or ProtrudeDist. The most similar conformer pair for each query/database molecule pair is selected [4].

- Pharmacophore Fingerprint Similarity: For the selected most similar conformer pair, generate a 3D pharmacophore fingerprint and calculate its similarity [4].

- Combined Scoring: Calculate a final combo score, typically the average of the shape similarity and the 3D fingerprint similarity, to rank the database molecules. This combined score provides a more robust ranking than shape alone [4].

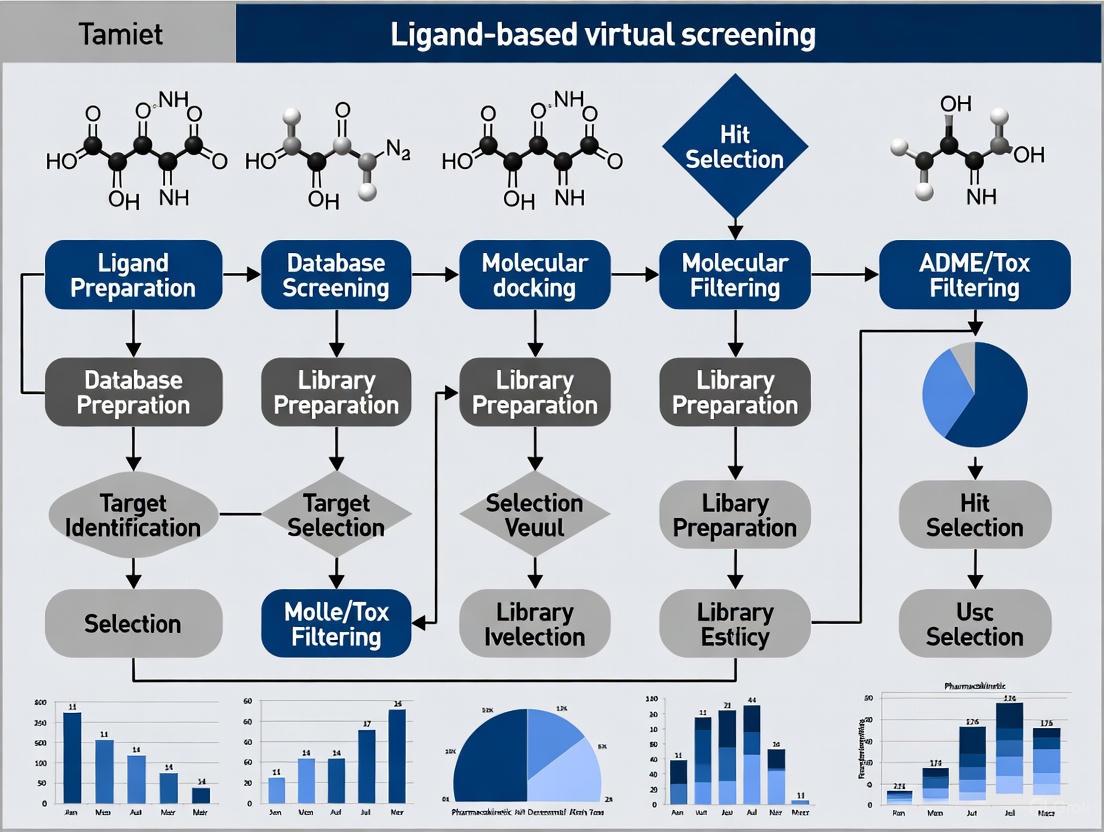

Diagram 1: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Workflow. This flowchart outlines the generalized protocol for conducting an LBVS campaign, from data preparation through to hit identification for experimental validation.

Machine Learning-Based Protocol using SVM

Machine learning algorithms, particularly Support Vector Machines (SVM), can be used for classification to distinguish between active and inactive compounds.

- Training Set Construction: Compile a labeled dataset from bioassay data, containing molecular structures and their corresponding class labels (active or inactive). Each molecule is represented as a vector of molecular descriptors or fingerprints [3].

- Feature Selection: Identify and select the most relevant molecular descriptors that contribute to the predictive power of the model, improving performance and reducing overfitting [3].

- Model Training: Train an SVM model using the training set. The algorithm finds the optimal hyperplane that separates the active and inactive compounds with a maximum margin. Non-linear kernels like the Radial Basis Function (RBF) can be used to handle complex, non-linearly separable data [3].

- Virtual Screening: Use the trained SVM model to predict the activity class (active/inactive) or a probability score for each molecule in the virtual screening database.

- Parallelization for Performance: Given the computational intensity of training on large datasets, parallelized versions of SVM algorithms (e.g., on GPUs) can be employed to drastically reduce processing time, making it feasible to screen billions of molecules [3].

Diagram 2: Machine Learning-Based LBVS Protocol. This diagram details the workflow for a machine learning-driven screening campaign, which relies on a trained model to predict compound activity.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The practical application of LBVS requires a suite of software tools and access to chemical databases. The table below catalogs key resources that constitute the modern computational chemist's toolkit for LBVS.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for LBVS: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in LBVS | Access/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Core cheminformatics operations: molecule standardization, fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation, pharmacophore perception, and shape alignment [4] [5]. | Python-based, widely used in tools like VSFlow [4]. |

| VSFlow | Open-Source Command-Line Tool | Integrated workflow for substructure, fingerprint, and shape-based virtual screening. Fully relies on RDKit and supports quick visualization of results [4]. | Available on GitHub under MIT license [4]. |

| ZINC Database | Commercial Compound Library | A publicly available database of over 21 million commercially available compounds for virtual screening [6]. Used as a standard screening library. | Publicly accessible database [6]. |

| Enamine REAL Space | Ultra-Large Virtual Chemical Library | A make-on-demand virtual chemical library exceeding 75 billion compounds, expanding the accessible chemical space for virtual screening [5]. | Accessible via vendor platforms. |

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) | Software for Shape-Based Screening | Industry-standard tool for rapid shape-based overlay and scoring of small molecules, used for ligand-centric virtual screening [1]. | Commercial software (OpenEye) [7]. |

| GpuSVMScreen | GPU-Accelerated Screening Tool | A tool that uses Support Vector Machines (SVM) for classification, parallelized on GPUs to enable the screening of billions of molecules in a short time frame [3]. | Source code available online [3]. |

| SwissSimilarity | Web Server | Public web tool that allows for 2D fingerprint and 3D shape screening of common public databases and commercial vendor libraries [4]. | Freely accessible web server [4]. |

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

The accuracy and utility of any LBVS method must be rigorously evaluated using standardized metrics and benchmarks. In retrospective studies, a virtual screening technique is tested on its ability to retrieve a small set of known active molecules from a much larger library of assumed inactive compounds or decoys [1].

Key metrics include:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the ability of a method to enrich true active compounds in the top X% of the ranked list compared to a random selection. For example, an EF1% of 16.72 indicates that the top 1% of the list is 16.72 times richer in actives than a random 1% of the entire library [8].

- Hit Rate: The percentage of compounds identified as hits out of the total number screened. Hit rates for virtual screening are generally low, often ranging from 0.1% to 5%, but can be significantly improved with high-quality methods and data [2].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC) of ROC Curve: The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate. The AUC provides a single measure of overall screening performance, where a value of 1.0 represents a perfect classifier and 0.5 represents a random classifier [8].

It is critical to note that retrospective benchmarks are not perfect predictors of prospective performance, where the goal is to find novel active scaffolds. Consequently, only prospective studies with experimental validation constitute conclusive proof of a method's effectiveness [1].

Ligand-based virtual screening remains a powerful, knowledge-driven paradigm in computational drug discovery. Its reliance on the chemical information of known actives makes it uniquely valuable when structural target data is lacking. As detailed in this whitepaper, the core methodologies—ranging from straightforward fingerprint similarity to advanced 3D shape alignment and machine learning models—provide a versatile toolkit for lead identification. The continuous development of open-source tools like VSFlow and the advent of GPU-accelerated algorithms are making the screening of billion-member libraries increasingly feasible. When integrated with careful experimental design and validation, LBVS significantly streamlines the early drug discovery pipeline, enhancing the efficiency and reducing the cost of bringing new therapeutics to the forefront.

The Similarity-Potency Principle in Chemical Space

The Similarity-Potency Principle stands as a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, positing that structurally similar molecules are more likely to exhibit similar biological activities and binding affinities. This principle permeates much of our understanding and rationalization of chemistry, having become particularly evident in the current data-intensive era of chemical research [9]. The principle provides the foundational justification for ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) approaches, which capitalize on the fact that ligands similar to an active ligand are more likely to be active than random ligands [10]. In practical terms, this means that when researchers know a set of ligands is active against a target of interest but lack the protein structure, they can employ LBVS to find new ligands by evaluating similarity between candidate ligands and known active compounds [10].

The Similarity-Potency Principle operates within a conceptual framework known as chemical space—a multidimensional descriptor space where molecules are positioned based on their structural and physicochemical properties [9]. In this space, similar molecules cluster together, creating neighborhoods with comparable bioactivity profiles. However, this principle has important exceptions, most notably "activity cliffs" where structurally similar compounds exhibit dramatically different potencies [11]. These exceptions highlight the complexity of molecular interactions and the nuanced application of the similarity principle in predictive modeling.

Theoretical Foundation: Molecular Representations and Similarity Quantification

Molecular Representations: From Structure to Fingerprints

Converting chemical structures into computable representations is essential for applying the Similarity-Potency Principle. The most widely used approaches transform molecular structures into molecular fingerprints—binary or count-based vectors that enable rapid comparison of large compound libraries [11].

Table 1: Major Molecular Fingerprint Types Used in Similarity-Potency Applications

| Fingerprint Type | Representation Method | Structural Features Encoded | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path-Based | Linear paths through molecular graphs | Sequences of atoms and bonds up to predefined length | Molecular similarity searching, substructure matching |

| Circular | Local atomic environments | Atom-centered substructures with defined radius | Separating actives from inactives in virtual screening |

| Atom-Pair | Atom pairs with distances | Atom types with topological separation | Medium-range structural features, 3D similarity |

| 2D Pharmacophore | Annotated paths | Pharmacophoric features and distances | Feature-based similarity, scaffold hopping |

| 3D Pharmacophore | Spatial arrangements | 3D distribution of pharmacophoric features | Shape-based screening, binding mode prediction |

These fingerprinting methods transform complex molecular structures into simplified numerical representations that can be efficiently processed by similarity algorithms. Path-based fingerprints count linear paths through molecular graphs, while circular fingerprints capture local atomic environments around each atom [11]. Atom-pair fingerprints incorporate topological distances between atoms, providing information about medium-range structural features [11].

Quantifying Similarity: Metrics and Algorithms

The Tanimoto coefficient emerges as the most prevalent method for quantifying molecular similarity, particularly with binary fingerprints. This coefficient measures the overlap between two fingerprint vectors by comparing the number of shared features to the total number of unique features, producing a similarity score ranging from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical) [11]. The Tanimoto coefficient is defined as:

[ T = \frac{N{AB}}{NA + NB - N{AB}} ]

Where (NA) and (NB) represent the number of features in molecules A and B, respectively, and (N_{AB}) represents the number of features common to both molecules.

For shape-based similarity approaches, which consider the three-dimensional arrangement of molecules, the similarity calculation incorporates volumetric overlap. The Tanimoto-like shape similarity is calculated as [10]:

[ T{shape} = \frac{V{A \cap B}}{V_{A \cup B}} ]

Where (V{A \cap B}) represents the common occupied volume between molecules A and B, and (V{A \cup B}) represents their total combined volume.

Experimental Validation: Assessing the Similarity-Potency Relationship

Benchmarking Databases and Validation Methodologies

Experimental validation of the Similarity-Potency Principle requires carefully designed benchmarks and standardized databases. The Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) database has emerged as a critical resource for this purpose, consisting of 40 pharmaceutically relevant protein targets with over 100,000 small molecules [10] [8]. This database enables researchers to systematically evaluate whether similarity-based methods can successfully distinguish active compounds from decoys with similar physical properties but dissimilar biological activity.

The Database of Useful Decoys (DUD) provides a rigorous testing ground for similarity-based approaches by including decoy molecules that are physically similar but chemically different from active compounds, creating a challenging discrimination task [10]. When using such benchmarks, virtual screening performance is typically evaluated using several key metrics:

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC): Measures the overall ability to rank active compounds higher than inactives

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Quantifies the concentration of active compounds in the top fraction of ranked results

- Hit Rate (HR): Measures the percentage of active compounds identified at specific thresholds [10]

Performance Benchmarks for Similarity-Based Screening

Rigorous validation studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of properly implemented similarity-based methods. A comprehensive evaluation of shape-based screening against the 40 targets in the DUD database achieved an average AUC value of 0.84 with a 95% confidence interval of ±0.02 [10]. This study also reported impressive early enrichment capabilities, with average hit rates of 46.3% at the top 1% of active compounds and 59.2% at the top 10% of active compounds [10].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

| Performance Metric | Average Value | Confidence Interval | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0.84 | ±0.02 (95% CI) | Excellent overall discrimination |

| Hit Rate at 1% | 46.3% | ±6.7% (95% CI) | Strong early enrichment |

| Hit Rate at 10% | 59.2% | ±4.7% (95% CI) | Good mid-range performance |

| Enrichment Factor | Varies by target | Target-dependent | Measure of early recognition |

These quantitative results provide compelling evidence for the practical utility of the Similarity-Potency Principle in drug discovery campaigns. The consistency across diverse protein targets demonstrates the generalizability of the approach, though performance naturally varies depending on the specific characteristics of each target and its corresponding active compounds.

Computational Protocols: Implementing Similarity-Based Screening

Workflow for Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

Implementing the Similarity-Potency Principle in practical drug discovery follows a structured workflow that transforms chemical structures into predicted activities. The following diagram illustrates the complete LBVS process:

Molecular Similarity Assessment Protocol

The core similarity assessment follows a standardized two-step process that can be implemented using open-source tools like VSFlow, which relies on the RDKit cheminformatics framework [4]:

Step 1: Molecular Representation

- Generate molecular fingerprints for both query and database compounds

- For 3D similarity: Generate multiple conformers using RDKit ETKDGv3 method

- Optimize conformers with MMFF94 forcefield

- Standardize structures using MolVS rules (charge neutralization, salt removal)

Step 2: Similarity Calculation

- For 2D similarity: Calculate Tanimoto coefficient between fingerprint vectors

- For 3D shape similarity: Align conformers with Open3DAlign functionality

- Calculate shape similarity (TanimotoDist) and 3D pharmacophore fingerprint similarity

- Compute combined score as average of shape and fingerprint similarities [4]

Practical Implementation with Open-Source Tools

The VSFlow toolkit provides a comprehensive implementation of similarity screening protocols with five specialized tools [4]:

- preparedb: Standardizes molecules, removes salts, generates fingerprints and multiple conformers

- substructure: Performs substructure search using RDKit's GetSubstructMatches()

- fpsim: Calculates fingerprint similarity with multiple similarity measures

- shape: Performs shape-based screening with combined shape and pharmacophore scoring

- managedb: Manages compound databases for virtual screening

For researchers, a typical similarity screening command using VSFlow would be:

This command screens database.vsdb using query compounds in query.smi, outputs results to results.sdf, and generates a similarity map visualization [4].

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Similarity-Potency Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular representation, fingerprint generation | Open-source |

| VSFlow | Screening Tool | Substructure, fingerprint, and shape-based screening | Open-source |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Commercially available compounds for screening | Public |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Known active compounds and bioactivities | Public |

| DUD Database | Benchmark Set | Active compounds and decoys for validation | Public |

| ROCS | Shape Similarity | Molecular shape comparison and overlay | Commercial |

| SwissSimilarity | Web Server | 2D fingerprint and 3D shape screening | Web-based |

For experimental confirmation of similarity-based predictions, researchers employ relative potency assays that measure how much more or less potent a test sample is compared to a reference standard under the same conditions [12]. These assays typically use parallel-line or parallel-curve models to assess similarity through equivalence testing, as recommended by USP guidelines [13].

The Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-finding Experiments (CACHE) initiative provides a modern framework for evaluating virtual screening methods, including similarity-based approaches [14]. In recent challenges, participants screened ultra-large libraries like the Enamine REAL space containing 36 billion purchasable compounds, with successful hits requiring measurable binding affinity (KD < 150 μM) confirmed by surface plasmon resonance assays [14].

Case Study: Application to SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors

A recent application demonstrates the power of the Similarity-Potency Principle in drug discovery. Researchers performed ligand-based virtual screening of approximately 16 million compounds from various small molecule databases using boceprevir as the reference compound [15]. Boceprevir, an HCV drug repurposed as a SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitor with IC50 = 4.13 ± 0.61 μM, served as the similarity query [15].

The screening identified several lead compounds exhibiting higher binding affinities (-9.9 to -8.0 kcal mol⁻¹) than the original boceprevir reference (-7.5 kcal mol⁻¹) [15]. Further analysis using molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) identified specific compounds (ChEMBL144205/C3, ZINC000091755358/C5, and ZINC000092066113/C9) as high-affinity binders to Mpro with binding affinities of -65.2 ± 6.5, -66.1 ± 7.1, and -67.3 ± 5.8 kcal mol⁻¹, respectively [15].

This case study exemplifies the complete workflow from similarity-based screening to experimental validation, with molecular dynamics simulations revealing higher structural stability and reduced residue-level fluctuations in Mpro upon binding of the identified compounds compared to apo-Mpro and Mpro-boceprevir complexes [15].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite its established utility, the Similarity-Potency Principle faces several significant challenges. Activity cliffs—where structurally similar compounds exhibit dramatically different potencies—remain difficult to predict and represent exceptions to the general principle [11]. The field also grapples with the fundamental question of what constitutes a "meaningful" similarity difference, as a Tanimoto similarity of 0.85 versus 0.75 may correspond to substantial activity changes in some contexts but not others [11].

Future directions focus on integrating artificial intelligence with similarity-based methods. New platforms like RosettaVS incorporate active learning techniques to efficiently triage and select promising compounds for expensive docking calculations, enabling screening of multi-billion compound libraries in less than seven days [8]. The emerging trend of hybrid approaches combines ligand-based and structure-based methods to leverage their complementary strengths, with machine learning models helping to integrate similarity information with interaction patterns from structural data [14].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated future approach:

As chemical libraries continue to grow into the billions of compounds, the Similarity-Potency Principle remains foundational for navigating this expansive chemical space efficiently. By combining traditional similarity concepts with modern AI acceleration, researchers can continue to leverage this fundamental principle to accelerate drug discovery while developing more nuanced understandings of its limitations and exceptions.

Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) is a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid identification of potential drug candidates from vast chemical libraries. Its strategic value is anchored in three fundamental advantages: superior computational speed, significant cost-efficiency, and valuable independence from protein structural data. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core advantages, framing them within the broader context of a virtual screening overview for researchers and drug development professionals. We detail the underlying methodologies, present curated experimental data, and provide protocols for implementing these techniques, thereby offering a comprehensive resource for leveraging LBVS in early-stage drug discovery campaigns.

Core Advantage 1: Unparalleled Speed and Operational Workflow

The velocity of LBVS stems from its reliance on computationally lightweight comparisons of molecular descriptors, bypassing the complex physics-based simulations of structure-based methods.

Quantitative Speed Comparisons

The following table summarizes the typical operational speeds of various LBVS methodologies compared to a common structure-based method, molecular docking.

Table 1: Speed Comparison of Virtual Screening Methodologies

| Methodology | Representative Tool | Approximate Speed (molecules/second/core) | Key Computational Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Fingerprint Similarity | VSFlow (fpsim) [4] | 1,000 - 100,000 | Tanimoto coefficient calculation on bit vectors |

| 3D Shape-Based Screening | VSFlow (shape) [4] | 10 - 100 | Molecular shape overlay and comparison |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | EquiVS [16] | 100 - 1,000* | High-order representation learning from molecular graphs |

| Structure-Based Docking | AutoDock Vina [8] | 0.1 - 10 | Pose sampling and physics-based energy scoring |

Note: Speed is highly dependent on model complexity and hardware (e.g., GPU acceleration).

As evidenced in Table 1, 2D fingerprint methods offer the highest throughput, capable of screening millions to billions of compounds in a feasible timeframe [4]. This makes them ideal for initial ultra-large library triaging. While 3D shape-based methods are slower, they remain significantly faster than molecular docking.

Workflow for High-Speed Fingerprint Screening

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for a high-speed, fingerprint-based screening campaign using a tool like VSFlow.

Protocol: High-Throughput Fingerprint Screening with VSFlow

Database Preparation (

preparedb):- Input: A compound library in SDF or SMILES format.

- Standardization: Execute

vsflow preparedb -s -cto standardize molecules, neutralize charges, and remove salts using MolVS rules [4]. - Fingerprint Generation: Use the

-fand-rarguments to generate and store the desired fingerprint (e.g., ECFP4) for every molecule in an optimized.vsdbdatabase file.

Similarity Search (

fpsim):- Input: The prepared

.vsdbdatabase and a query molecule (SMILES or structure file). - Execution: Run

vsflow fpsim -q <query.smi> -db <database.vsdb> -o results.xlsxto perform the similarity search. - Parameters: The default fingerprint is a 2048-bit Morgan fingerprint (FCFP4-like) with a radius of 2, using the Tanimoto coefficient for similarity scoring. These parameters can be customized.

- Input: The prepared

Hit Identification: The tool outputs a ranked list of compounds based on similarity score, allowing for rapid prioritization of the top hits for further experimental validation [4].

Core Advantage 2: Significant Cost-Efficiency

LBVS drastically reduces the financial burden of early drug discovery by minimizing the need for expensive experimental protein structures and replacing a substantial portion of costly high-throughput screening (HTS) with computational filtering.

Economic Impact Analysis

Table 2: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Hit Identification Strategies

| Factor | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) | Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Costs | Experimental reagents, assay plates, liquid handlers, and extensive personnel time. | Computational infrastructure (CPUs/GPUs) and software. | Protein crystallization/X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or NMR; high-performance computing (HPC) for docking. |

| Typical Library Size | 100,000 - 1,000,000 compounds | 1,000,000 - 1,000,000,000+ compounds [8] | 1,000,000 - 10,000,000+ compounds (ultra-large docking is resource-intensive) [14] |

| Hit Rate | Often low (0.001% - 0.1%) | Can be significantly enriched (e.g., 14-44% reported in one study [8]) | Varies with target and method accuracy; can be highly enriched. |

| Resource Demand | Very high (specialized lab) | Low to moderate (standard compute cluster) | Moderate to very high (HPC for large-scale docking) |

The data in Table 2 highlights that LBVS leverages low-cost computational resources to intelligently guide experimental efforts, focusing synthesis and assay resources on a much smaller, higher-probability set of compounds, thereby offering an outstanding return on investment [8].

Core Advantage 3: Independence from Protein Structure

A pivotal advantage of LBVS is its applicability when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown, unavailable, or of poor quality.

LBVS operates on the "similarity principle" – that structurally similar molecules are likely to have similar biological activities [16] [17]. This allows it to use known active ligands as templates to find new ones, entirely bypassing the need for the protein structure. The following table classifies key LBVS methodologies that operate without structural data.

Table 3: Key Structure-Independent LBVS Methodologies and Performance

| Methodology | Description | Representative Tool / Study | Reported Performance (AUC/EF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Fingerprint Similarity | Compares molecular topological patterns using bit-string fingerprints. | VSFlow [4] | Average AUC: 0.84 on DUD dataset [10] |

| 3D Shape/Pharmacophore | Aligns and scores molecules based on 3D shape and chemical feature overlap. | HWZ Score [10] | Average Hit Rate @ 1%: 46.3% on DUD [10] |

| Graph Edit Distance (GED) | Computes distance between molecular graphs representing pharmacophoric features. | Learned GED Costs [17] | Improved classification vs. baseline costs on multiple datasets [17] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Learns complex molecular representations directly from graph structures. | EquiVS [16] | Outperformed 10 baseline methods on a large benchmark [16] |

Protocol for Structure-Independent Screening with a GNN

For targets with sufficient bioactivity data, deep learning models like GNNs can achieve state-of-the-art performance without structural information.

Protocol: Implementing a GNN for LBVS

Data Curation and Featurization:

- Input: Collect a set of known active and inactive compounds for the target.

- Featurization: Represent each molecule as a graph where nodes are atoms (featurized with atom type, degree, etc.) and edges are bonds (featurized with bond type) [18] [16]. Alternatively, use a SMILES string as input for a chemical language model.

Model Training and Fusion:

- Architecture Selection: Choose a GNN architecture such as a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Graph Attention Network (GAT). Studies show that simpler GNNs, when combined with expert-crafted molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP), can perform on par with more complex models [18].

- Training: Train the model to classify compounds as active/inactive or predict a binding affinity value. Use the curated dataset, ensuring a rigorous train/test split to avoid overfitting.

Virtual Screening:

- Deployment: Use the trained model to predict the bioactivity of every molecule in a large virtual library.

- Output: The output is a ranked list of compounds based on the predicted activity, ready for experimental confirmation [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for executing a successful LBVS campaign.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LBVS

| Item / Tool | Function / Description | Use Case in LBVS |

|---|---|---|

| VSFlow [4] | An open-source command-line tool that integrates substructure, fingerprint, and shape-based screening in one package. | A versatile all-in-one solution for running various LBVS methodologies, from simple 2D searches to 3D shape comparisons. |

| RDKit [4] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit written in C++ and Python. | The computational engine behind many tools (like VSFlow) for molecule standardization, fingerprint generation, and conformer generation. |

| CURATED Benchmark Datasets (e.g., DUD-E, LIT-PCBA [17]) | Publicly available datasets containing known active and decoy molecules for validated targets. | Essential for training, validating, and benchmarking new LBVS models and protocols to ensure performance and generalizability. |

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., ECFP4, Physicochemical Properties [18]) | Numerical representations of molecular structure and properties. | Used as input features for machine learning models. Expert-crafted descriptors can significantly boost model performance [18]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Architectures (e.g., GCN, SphereNet [18] [16]) | Deep learning models designed to operate directly on graph-structured data. | Used to learn complex, high-order molecular representations from data, often leading to state-of-the-art prediction accuracy. |

| Pre-computed Molecular Libraries (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL [4] [16]) | Large, annotated databases of commercially available or published compounds. | The source "haystack" in which to search for new "needles" (hits). Often pre-processed for virtual screening. |

The field of drug discovery has undergone a revolutionary transformation over recent decades, shifting from traditional trial-and-error approaches to sophisticated computational and automated methodologies. Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) stands as a pivotal component in this evolution, operating on the fundamental principle that chemically similar compounds are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [19]. This principle, first qualitatively applied by medicinal chemists "in cerebro," has been systematically quantified and operationalized through computational means, creating a discipline now essential to modern pharmaceutical research [20] [21]. The journey from early similarity concepts to contemporary high-throughput platforms represents more than just technological advancement; it signifies a fundamental restructuring of the drug discovery workflow, enabling researchers to navigate the expansive chemical universe of potential drug candidates with unprecedented speed and precision.

The historical development of LBVS is characterized by key transitions: from one-dimensional descriptors to complex graph-based representations, from manual calculations to artificial intelligence-accelerated platforms, and from targeted small-scale screening to the exploration of ultra-large chemical libraries. This whitepaper examines this technical evolution, documenting how foundational similarity principles have been adapted and enhanced through successive technological innovations to address the growing complexity and demands of contemporary drug discovery, particularly for challenging therapeutic areas such as neurodegenerative diseases [22].

Historical Foundations of Ligand-Based Screening

Early Theoretical and Methodological Origins

The conceptual roots of ligand-based screening extend back to the 19th century with early recognitions of relationships between chemical structure and biological activity. Pioneering work by Meyer (1899) and Overton (1901) established the "Lipoid theory of cellular depression," formally recognizing lipophilicity as a key determinant of pharmacological activity [20]. This period marked the crucial transition from purely descriptive observations to quantitative relationships, laying the groundwork for systematic drug design.

The 1960s witnessed the formal birth of quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) through the groundbreaking work of Corwin Hansch, who utilized computational statistics to establish mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological effects [20]. This represented the infancy of in silico pharmacology, moving beyond qualitative assessment to predictive computational modeling. Early QSAR approaches primarily focused on one-dimensional molecular properties such as size, molecular weight, logP, and dipole moment [19]. Concurrently, the evolution from two-dimensional to three-dimensional molecular recognition, advanced by researchers like Cushny (1926), introduced the critical importance of stereochemistry and molecular conformation in biological activity [20].

Key Technological Transitions

The 1980s and 1990s marked a period of rapid methodological expansion, with several complementary approaches emerging to enrich the ligand-based screening toolkit:

- Molecular fingerprinting enabled efficient similarity searching through binary structural representations [23]

- Pharmacophore modeling allowed for three-dimensional database searching based on essential functional group arrangements [23]

- Compound clustering algorithms facilitated the organization of chemical libraries based on structural similarity [23]

- Whole-molecule similarity assessment gained formal recognition as an indicator of similar biological activity [23]

During this period, the term "chemoinformatics" first appeared in the literature (1998), providing an umbrella for the growing collection of computational methods being applied to chemical problems [23]. The field was further stimulated by the advent of combinatorial chemistry and high-throughput screening (HTS), which generated unprecedented volumes of compounds and data requiring computational management and analysis [23].

Methodological Evolution and Technical Approaches

Molecular Representation and Descriptor Development

The evolution of molecular representation has progressed through increasing levels of abstraction and sophistication, directly enabling more nuanced and effective virtual screening approaches.

Table 1: Evolution of Molecular Descriptors in Virtual Screening

| Descriptor Dimension | Representation Type | Key Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Global molecular properties | Molecular weight, logP, dipole moment, BCUT parameters | Initial screening, property prediction |

| 2D Descriptors | Structural fingerprints | Topological fingerprints, path-based fingerprints | High-throughput similarity searching |

| 3D Descriptors | Spatial representations | Molecular volume, steric and electronic fields | Shape-based similarity, pharmacophore mapping |

| Graph-Based Descriptors | Attributed graphs | Reduced graphs, extended reduced graphs (ErGs) | Complex similarity assessment, scaffold hopping |

The transition to graph-based representations represents one of the most significant advances in molecular similarity assessment. In these models, compounds are represented as attributed graphs where nodes represent pharmacophoric features or structural components and edges represent chemical bonds or spatial relationships [19]. This representation enables the application of sophisticated graph theory algorithms, including the Graph Edit Distance (GED), which defines molecular similarity as the minimum cost required to transform one graph into another through a series of edit operations (node/edge insertion, deletion, or substitution) [19]. The critical challenge in implementing GED lies in properly tuning the transformation costs to reflect biologically meaningful similarities, which has led to the development of machine learning approaches to optimize these parameters for specific screening applications [19].

Quantitative Methodologies and Similarity Assessment

The computational core of LBVS has evolved through several generations of quantitative methodologies:

Bayesian Methods: Probabilistic virtual screening approaches based on Bayesian statistics have emerged as widely used ligand-based methods, offering a robust statistical framework for compound prioritization [23]. These methods utilize molecular descriptors to calculate the probability of activity given a compound's structural features, allowing for effective ranking of screening libraries.

Shape-Based Similarity: Going beyond two-dimensional structural similarity, shape-based approaches assess the three-dimensional volume overlap between molecules, recognizing that similar molecular shapes often interact with biological targets in similar ways [19].

Pharmacophore Mapping: This technique abstracts molecules into their essential functional components (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups) and evaluates similarity based on the spatial arrangement of these features [19].

Table 2: Core Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Methodologies

| Methodology | Fundamental Principle | Technical Implementation | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Similarity Searching | Structural resemblance in 2D space | Molecular fingerprints, Tanimoto coefficient | High speed, well-established |

| 3D Shape Similarity | Complementary molecular volumes | Volume overlap algorithms | Identification of scaffold hops |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Essential feature alignment | 3D pharmacophore perception and mapping | Incorporates chemical functionality |

| Graph-Based Similarity | Topological structure matching | Graph Edit Distance, reduced graphs | Balanced detail and abstraction |

| Bayesian Methods | Probabilistic activity prediction | Machine learning classifiers, statistical models | Robust statistical foundation |

Modern High-Throughput Screening Platforms

The Rise of Automated Screening Technologies

The emergence of high-throughput screening (HTS) in the mid-1980s, pioneered by pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer using 96-well plates, marked a transformative moment in drug discovery [24]. This technological shift replaced months of manual work with days of automated testing, fundamentally changing the scale and pace of compound evaluation. A screen is formally considered "high throughput" when it conducts over 10,000 assays per day, with ultra-high-throughput screening reaching 100,000+ daily assays [24].

Modern HTS platforms integrate multiple advanced components:

- Automation systems with robotic liquid handlers and plate stackers

- Miniaturized assay formats (384-well and 1536-well microtiter plates)

- High-sensitivity detection methods (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance)

- Sophisticated data management systems (LIMS, ELNs) [25]

The typical HTS workflow encompasses target selection, assay development, plate formatting, screen execution, data acquisition, and hit validation—a process that can be completed in 4-6 weeks in well-established platforms [25].

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Screening

Protocol 1: Cell-Based HTS Assay for Neurodegenerative Disease Targets

- Target Identification: Focus on proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, such as tau in Alzheimer's disease or α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease [22]

- Assay Design: Develop cell-based assays using neuronal cell lines or primary neurons to capture complex disease phenotypes [22]

- Plate Preparation: Dispense compounds into 384-well or 1536-well plates using acoustic dispensing or pin tools

- Cell Seeding and Compound Treatment: Seed cells at appropriate density and treat with compound libraries

- Incubation and Stimulation: Incubate under physiological conditions and apply disease-relevant stressors if required

- Endpoint Measurement: Utilize fluorescence-based readouts (e.g., calcium flux, cell viability dyes) or luminescence assays

- Data Acquisition: Employ high-content imaging or plate readers for signal detection

- Hit Identification: Apply statistical thresholds (e.g., 3 standard deviations from DMSO control) to identify initial hits [22]

Protocol 2: Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

- Compound Titration: Prepare compound plates with concentration gradients across multiple wells

- Dose-Response Testing: Test each compound at multiple concentrations in parallel

- Curve Fitting: Generate dose-response curves for all library compounds

- Quality Control: Assess assay performance using Z'-factor calculations

- Hit Confirmation: Prioritize compounds with robust concentration-dependent effects [24]

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Platforms

The most recent evolution in screening technology comes from the integration of artificial intelligence with physical screening methods. Platforms like RosettaVS incorporate active learning techniques to efficiently triage and select promising compounds from ultra-large libraries for expensive docking calculations [8]. These systems employ a two-tiered docking approach:

- Virtual Screening Express (VSX): Rapid initial screening mode

- Virtual Screening High-Precision (VSH): More accurate method for final ranking of top hits [8]

This hierarchical approach, combined with improved force fields (RosettaGenFF-VS) that incorporate both enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) components, has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks, achieving an enrichment factor of 16.72 in the top 1% of screened compounds—significantly outperforming previous methods [8]. The platform has successfully identified hit compounds with single-digit micromolar binding affinities for challenging targets like the human voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7, completing screening of billion-compound libraries in under seven days using 3000 CPUs and one GPU [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflows in modern screening platforms depend on carefully curated research reagents and materials that ensure reproducibility and biological relevance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Screening Platforms

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Screening Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | 100,000 to millions of diverse chemical structures | Source of potential drug candidates for screening |

| Cell Lines | Genetically engineered or disease-relevant cell types | Provide biological context for target engagement |

| Assay Reagents | Fluorescent dyes, luminescent substrates, antibodies | Enable detection of biological activity |

| Microtiter Plates | 384-well or 1536-well format with specialized coatings | Miniaturized platform for parallel compound testing |

| Liquid Handling Reagents | Buffers, diluents, detergent solutions | Ensure accurate compound transfer and dispensing |

For specialized applications such as neurodegenerative disease research, primary neuronal cultures are increasingly used despite their technical challenges, as they offer enhanced biological and clinical relevance for capturing critical cellular events in disease states [22]. Advanced platforms like the Bioelectrochemical Crossbar Architecture Screening Platform (BiCASP) enable real-time electrochemical characterization of cellular responses, providing minute-scale signal stability for functional screening [26].

Visualization of Screening Workflows and Methodologies

Historical Evolution of Ligand-Based Screening Approaches

Modern AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Workflow

The journey from early similarity searches to modern high-throughput platforms represents a remarkable technological evolution that has fundamentally transformed drug discovery. What began as qualitative observations of structure-activity relationships has matured into a sophisticated computational discipline capable of navigating chemical spaces containing billions of compounds. The historical development of ligand-based virtual screening has been characterized by continuous methodological innovation—from QSAR to molecular fingerprints, from graph-based similarity to Bayesian statistics, and finally to the integration of artificial intelligence with high-throughput experimental platforms.

Contemporary screening paradigms successfully combine the strengths of computational and experimental approaches, using virtual screening to prioritize compounds for experimental validation in an iterative feedback loop that continuously improves predictive models. This synergy has proven particularly valuable for challenging therapeutic areas like neurodegenerative diseases, where the complexity of biological systems demands sophisticated screening approaches [22]. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of multi-omics data, advanced biomimetic assay systems, and increasingly accurate AI models promises to further enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of ligand-based screening, continuing the historical trajectory of innovation that has characterized this critical domain of pharmaceutical research.

The essential principle that "similar compounds have similar activities" continues to guide methodological development, even as the techniques for quantifying similarity and assessing activity grow increasingly sophisticated. This enduring foundation, combined with relentless technological innovation, ensures that ligand-based virtual screening will remain a cornerstone of drug discovery for the foreseeable future.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) is a fundamental strategy for identifying novel bioactive compounds when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable or limited [14]. This approach operates on the Similarity-Property Principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities and properties [27]. The effectiveness of LBVS hinges on three interconnected computational concepts: molecular representations, which translate chemical structures into computer-readable formats; similarity measures, which quantify the structural or functional resemblance between molecules; and scoring functions, which rank compounds based on their predicted activity or complementarity to a target [28] [27]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core concepts, framing them within the context of a comprehensive LBVS overview research thesis, and is intended for researchers, scientists, and professionals engaged in drug development.

Molecular Representations

Molecular representation serves as the foundational step in any chemoinformatics or virtual screening pipeline, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties [28]. It involves converting molecules into mathematical or computational formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior [28].

Traditional Molecular Representations

Traditional methods rely on explicit, rule-based feature extraction or string-based formats to describe molecules [28].

- String-Based Representations: The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) is a compact and efficient string-based method to encode chemical structures and remains a mainstream molecular representation method [28]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) name and the International Chemical Identifier (InChI) are other standardized string representations [28].

- Molecular Descriptors: These are numerical values that quantify the physical or chemical properties of a molecule (e.g., molecular weight, hydrophobicity) or its topological characteristics (e.g., topological indices) [28].

- Molecular Fingerprints: These typically encode substructural information as binary strings or numerical vectors, enabling efficient comparison of molecules [28]. They can be broadly categorized as substructure-preserving or feature-based fingerprints [27].

Modern AI-Driven Representations

Advances in artificial intelligence have ushered in data-driven learning paradigms that move beyond predefined rules [28]. These methods leverage deep learning models to directly extract and learn intricate features from molecular data [28].

- Language Model-Based Representations: Inspired by natural language processing (NLP), models such as Transformers have been adapted for molecular representation by treating molecular sequences (e.g., SMILES) as a specialized chemical language [28].

- Graph-Based Representations: These methods represent a molecule as a graph, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can then learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings that capture both local and global molecular features [28].

- Multimodal and Contrastive Learning: Recently, frameworks that combine multiple representation types (e.g., SMILES and graphs) or that use contrastive learning to enhance the quality of learned embeddings have gained popularity for their ability to capture more robust molecular features [28].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Molecular Representations

| Category | Type | Key Examples | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | String-Based | SMILES, InChI [28] | Human-readable, compact string format; may not fully capture structural complexity. | Data storage, exchange, simple parsing. |

| Molecular Descriptors | AlvaDesc, RDKit Descriptors [29] | Numeric values quantifying physico-chemical or topological properties. | QSAR, QSPR, machine learning model input. | |

| Fingerprints | Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) [28], MACCS Keys [30], Chemical Hashed Fingerprint (CFP) [27] | Binary or count-based vectors encoding substructures or features; computationally efficient. | Similarity search, clustering, virtual screening. | |

| Modern AI-Driven | Language Model-Based | SMILES-BERT, Transformer-based models [28] | Treats molecules as sequential data; learns contextual embeddings via self-supervised tasks. | Molecular property prediction, generation. |

| Graph-Based | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [28] | Represents atoms/bonds as nodes/edges; captures topological structure inherently. | Activity prediction, binding affinity estimation. | |

| Multimodal & Contrastive Learning | Multimodal frameworks, Contrastive loss models [28] | Combines multiple data views (e.g., graph + SMILES); improves feature robustness. | Scaffold hopping, lead optimization. |

Similarity Measures

Once molecules are represented as vectors or embeddings, similarity measures are used to quantify the degree of resemblance between two molecules, which is the core of ligand-based virtual screening.

Molecular Fingerprints and Similarity Expressions

Molecular fingerprints are one of the most systematic and broadly used molecular representation methodologies for computational chemistry workflows [27]. They are descriptors of structural features and/or properties within molecules, determined either by predefined features or mathematical descriptors [27]. The choice of fingerprint has a significant influence on quantitative similarity [27].

- Substructure-Preserving Fingerprints: These use a predefined library of structural patterns or exhaustive path identification. They are suitable for substructure search and similarity assessments where specific structural motifs are critical. Examples include:

- Feature Fingerprints: These represent characteristics within a molecule that correspond to key structure-activity properties and are often more suitable for activity-based virtual screening. They are non-substructure preserving. Examples include:

- Radial (Circular) Fingerprints: The Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) is the most common, which starts from each atom and expands out to a given diameter [27]. Others include Functional-Class FingerPrints (FCFPs) and MiniHashFingerpint (MHFP) [27].

- Topological Fingerprints: These represent graph distance within a molecule. Examples include Atom pair fingerprints, Topological Torsion (TT), and MAP4 fingerprints [27].

- 3D- and Interaction-Based Fingerprints: These include pharmacophore fingerprints (e.g., PLIF, SPLIF), and shape-based fingerprints (e.g., ROCS, USR) that describe the 3D surface of a molecule [27].

Similarity and distance functions are used to quantitatively determine the similarity between two structures represented by fingerprints [27]. For a binary fingerprint, the following symbols are used:

a= number of on bits in molecule Ab= number of on bits in molecule Bc= number of bits that are on in both moleculesd= number of common off bitsn= bit length of the fingerprint (n = a + b - c + d) [27]

Table 2: Common Similarity and Distance Measures for Molecular Fingerprints

| Measure Name | Formula | Key Properties and Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Tanimoto Coefficient | ( S_{Tanimoto} = \frac{c}{a + b - c} ) | The most widely used similarity metric for binary fingerprints; symmetric and intuitive [27]. |

| Soergel Distance | ( D{Soergel} = 1 - S{Tanimoto} ) | Tanimoto dissimilarity; a proper distance metric [27]. |

| Dice Coefficient | ( S_{Dice} = \frac{2c}{a + b} ) | Similar to Tanimoto but gives more weight to common on-bits [27]. |

| Tversky Index | ( S_{Tversky} = \frac{c}{\alpha(a - c) + \beta(b - c) + c} ) | An asymmetric similarity measure; useful when one molecule is a reference query [27]. |

| Cosine Similarity | ( S_{Cosine} = \frac{c}{\sqrt{a} \cdot \sqrt{b}} ) | Measures the angle between feature vectors; common in continuous-valued descriptor spaces [27]. |

| Euclidean Distance | ( D_{Euclidean} = \sqrt{(a - c) + (b - c)} ) | Straight-line distance between vectors; sensitive to vector magnitude [27]. |

| Manhattan Distance | ( D_{Manhattan} = (a - c) + (b - c) ) | Sum of absolute differences; less sensitive to outliers than Euclidean distance [27]. |

Performance and Benchmarking

The performance of similarity measures is significantly influenced by the applied molecular descriptors, the chosen similarity measure, and the specific biological target [30]. For instance, a benchmark study on nucleic acid-targeted ligands demonstrated that classification performance varied across targets and that a consensus method that combines the best-performing algorithms of distinct nature outperformed all other tested single methods [30]. This highlights the importance of method selection and benchmarking for specific virtual screening campaigns.

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are computational procedures used to rank-order compounds based on their predicted activity, binding affinity, or complementarity to a target. They are the final critical step in a virtual screening workflow that enables prioritization of compounds for experimental testing.

Classical and Consensus Scoring

- Structure-Based Scoring: In molecular docking, which is a structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) technique, scoring functions estimate the binding affinity of a protein-ligand complex. Terms often include nonbonded van der Waals, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen-bonding, and desolvation penalties [31]. The Pharmacophore Matching Similarity (FMS) scoring function is an example that encodes useful chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic groups) and scores based on the overlap between a reference ligand pharmacophore and candidate pharmacophores [31].

- Ligand-Based Scoring: This includes predicted activity values from Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, which establish a statistical correlation between molecular descriptors and biological activity [32]. Similarity scores from ligand-based methods also serve as scoring functions.

- Consensus Scoring: This approach combines multiple scoring functions to improve the robustness and enrichment of virtual screening. It mitigates the limitations of individual scoring functions by approximating the true value more closely through repeated samplings [29]. Methods include:

- Mean, Median, Min, Max: Simple statistical aggregations of normalized scores from different methods [29].

- Machine Learning-Based Consensus: A novel pipeline employs machine learning models to amalgamate various conventional screening methods (e.g., QSAR, Pharmacophore, docking, 2D shape similarity) into a single consensus score, which has been shown to outperform individual methods [29].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Scoring

Machine learning has revolutionized scoring functions by enabling faster predictions and leveraging large datasets.

- QSAR Models: ML-based QSAR uses regression models (e.g., random forest, support vector regression, gradient boosting) to predict activity values like IC50 or binding affinity based on molecular fingerprints and descriptors [33] [32].

- Docking Score Prediction: ML models can be trained to predict docking scores directly from 2D molecular structures, bypassing the need for time-consuming molecular docking procedures. This approach can be 1000 times faster than classical docking-based screening, enabling the rapid evaluation of ultra-large chemical libraries [32].

- Hybrid and Parallel Combination: The integration of LBVS and SBVS can be achieved through sequential, hybrid, or parallel combinations [14]. Hybrid methods integrate both into a unified framework, such as interaction-based methods that use interaction fingerprints, while parallel combinations run LBVS and SBVS simultaneously and fuse the results using data fusion algorithms [14].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Methodology for a Consensus Virtual Screening Workflow

The following protocol, adapted from a recent study on consensus holistic virtual screening, provides a detailed template for running a multi-method virtual screening campaign [29].

Dataset Curation:

- Obtain active compounds and corresponding decoys from public databases like PubChem and the Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced (DUD-E) [29].

- Standardize molecular structures: neutralize charges, remove duplicates, salt ions, and small fragments. Convert activity values (e.g., IC50) to pIC50 [pIC50 = -log10(IC50)] [29].

- Assess and mitigate dataset bias by analyzing the distribution of physicochemical properties between actives and decoys to ensure a realistic screening scenario [29].

Calculation of Fingerprints and Descriptors:

- Use cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit to compute a wide range of molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MACCS, Topological Torsions) and molecular descriptors for all compounds [29].

Multi-Method Scoring:

- Score the dataset using four distinct methods [29]:

- QSAR: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) on active/decoy data to predict activity scores.

- Pharmacophore: Perform a pharmacophore screening using a tool like Pharaho or LiSiCA to get a fit score.

- Docking: Conduct molecular docking (e.g., with AutoDock Vina) for all compounds to obtain a binding energy score.

- 2D Shape Similarity: Calculate the Tanimoto similarity based on a fingerprint like ECFP4 against a known active reference.

- Score the dataset using four distinct methods [29]:

Model Training and Consensus Score Calculation:

- Fine-tune the machine learning models used in the QSAR step. Rank the performance of all models (across all four methods) using a robust metric (e.g., a novel formula like "w_new" that integrates coefficients of determination and error metrics) [29].

- Calculate a Z-score for each compound from each of the four screening methodologies.

- Compute the final consensus score for each compound as a weighted average of the Z-scores, where the weights are determined by the performance ranking of the respective models [29].

Validation:

- Perform an enrichment study (e.g., calculate AUC-ROC values) to evaluate the ability of the consensus score to rank active compounds earlier than decoys compared to individual methods [29].

- Externally validate the model's predictive performance using a hold-out test set not seen during training [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Software, Databases, and Resources for Virtual Screening

| Item Name | Type | Function in Workflow | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics Toolkit | Calculation of molecular fingerprints, descriptors, structure standardization, and basic molecular operations. | [29] [33] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity Database | Source of known active ligands and their activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) for model training and validation. | [32] |

| DUD-E | Database | Repository of known active compounds and matched decoys for specific protein targets; used for benchmarking virtual screening methods. | [29] |

| ZINC | Commercial Compound Library | Large database of purchasable compounds for virtual screening to identify potential hit compounds. | [32] |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Structure-based virtual screening by predicting the binding pose and affinity of ligands to a protein target. | [33] |

| Smina | Docking Software | A variant of Vina with a focus on scoring function customization, used for generating docking scores for training ML models. | [32] |

| Python & scikit-learn | Programming Language & ML Library | Environment for building and training machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) for QSAR and score prediction. | [33] [32] |

| KNIME | Analytics Platform | Graphical platform for building and executing data pipelines, including cheminformatics nodes for fingerprint calculation and data processing. | [30] |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for ligand-based virtual screening, depicting the sequential stages of molecular representation, similarity measurement, and scoring, culminating in a ranked hit list.

Figure 2: A comprehensive virtual screening strategy illustrating the combined usage of ligand-based and structure-based methods, culminating in data fusion and consensus scoring for hit prioritization.

Implementing LBVS: From Traditional Methods to AI-Driven Workflows

In the face of high costs and protracted timelines associated with traditional drug development, Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) has emerged as a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. LBVS methods are employed when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown or unavailable, relying instead on the principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical properties are likely to exhibit similar biological activities—a concept formally known as the Similar Property Principle (SPP) [34]. Among the most robust and widely used techniques within the LBVS paradigm are two-dimensional (2D) methods, which utilize the abstract topological structure of a molecule, treating it as a graph where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to three foundational 2D approaches: molecular fingerprints, substructure searches, and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, framing them within a comprehensive LBVS workflow designed for researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Fingerprints: Encoding Molecules as Vectors

Concepts and Generation

Molecular fingerprints are computational representations that transform a chemical structure into a fixed-length bit string or numerical vector, enabling rapid similarity comparison and machine learning-ready data generation [35]. They serve as a bridge to correlate molecular structures with physicochemical properties and biological activities. A quality fingerprint is characterized by its ability to represent local molecular structures, be efficiently combined and decoded, and maintain feature independence [35].

The generation process typically involves fragmenting the molecule according to a specific algorithm and then hashing these fragments into a fixed-length vector. The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for generating a molecular fingerprint.

Types of Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints can be classified into several distinct types based on the algorithmic approach used to generate the molecular features. The table below summarizes the key categories, their operating principles, and representative examples.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major Molecular Fingerprint Types

| Fingerprint Type | Core Principle | Representative Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dictionary-Based (Structural Keys) [36] [35] | Predefined list of structural fragments; each bit represents the presence/absence of a specific substructure. | MACCS, PubChem Fingerprints | Fast substructure screening; interpretable but limited to known fragments. |