Ligand-Based Drug Design: Approaches, Applications, and Advances in Modern Drug Discovery

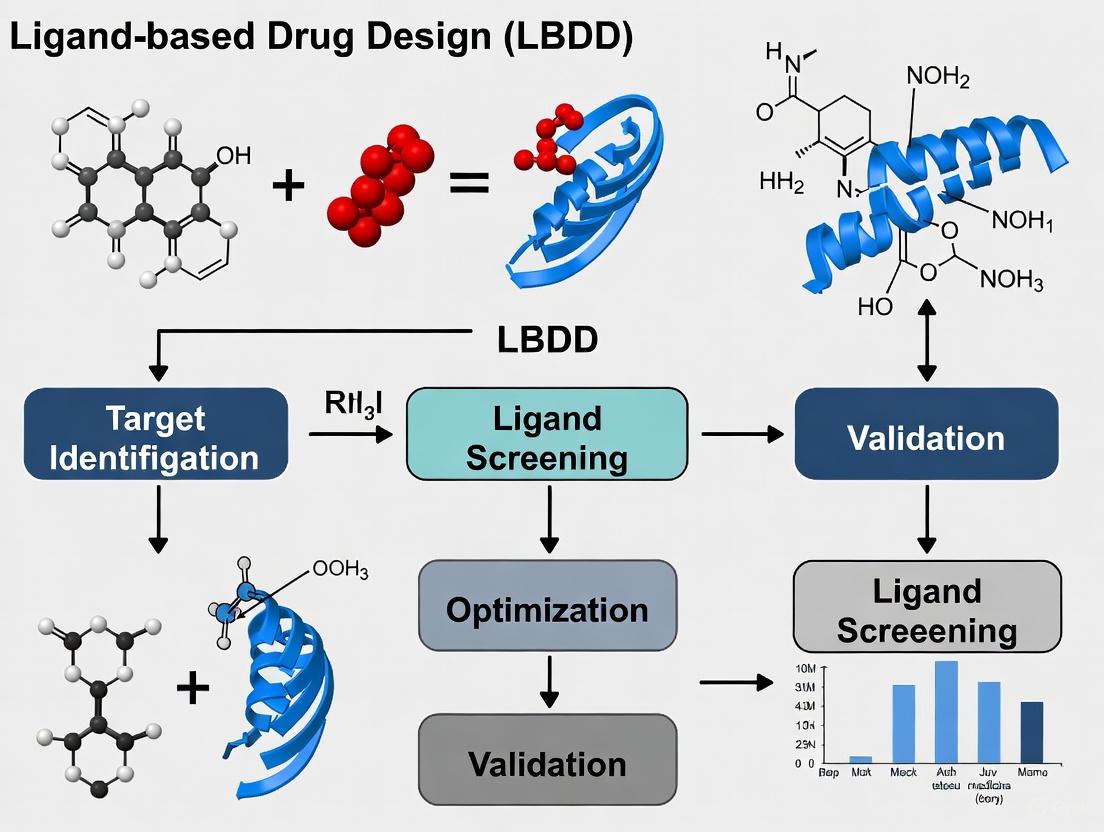

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD), a pivotal computational approach in modern drug discovery when the 3D structure of a biological target is unavailable.

Ligand-Based Drug Design: Approaches, Applications, and Advances in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD), a pivotal computational approach in modern drug discovery when the 3D structure of a biological target is unavailable. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of LBDD, details key methodologies like Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and pharmacophore modeling, and discusses their practical applications in lead identification and optimization. The content further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, validates LBDD through comparisons with structure-based methods, and highlights the growing impact of integrated and AI-enhanced approaches for developing novel therapeutics.

The Foundations of Ligand-Based Drug Design: Principles and Core Concepts

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) represents a cornerstone computational strategy in modern drug discovery for targets lacking three-dimensional structural data. This application note delineates the core principles, methodologies, and protocols of LBDD, framing it within the broader context of rational drug design. We provide a detailed examination of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and pharmacophore development as primary techniques, supplemented by structured workflows and reagent solutions. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this document serves as a practical guide for implementing LBDD strategies to accelerate lead identification and optimization, particularly for recalcitrant targets such as membrane proteins and novel disease mechanisms.

In the drug discovery pipeline, the absence of a resolved three-dimensional (3D) structure for a target protein—often the case for membrane-associated proteins like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), nuclear receptors, and transporters—presents a significant hurdle [1]. Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) emerges as a powerful solution to this challenge, enabling drug discovery efforts based solely on knowledge of small molecules (ligands) known to modulate the target's biological activity [2] [3]. This approach is fundamentally independent of any direct structural information about the target itself, operating instead on the principle that compounds with similar structural and physicochemical properties are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [4].

The core of LBDD is the establishment of a Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), which correlates variations in the chemical structures of known ligands with their measured biological activities [5] [1]. By iteratively analyzing this SAR, researchers can elucidate the key features responsible for biological activity and rationally design new compounds with improved potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic profiles [1]. The continued relevance of LBDD is underscored by the fact that over 50% of FDA-approved drugs target membrane proteins, for which 3D structures are often unavailable, ensuring LBDD's critical role in the foreseeable future of drug development [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Key LBDD Methods

LBDD methodologies range from simple similarity comparisons to complex quantitative models, all aiming to translate chemical information into predictive tools for compound design.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

QSAR is a mathematical modeling technique that relates a suite of numerical descriptors, which encode the physicochemical and structural properties of a set of ligands, to their quantitative biological activity [1] [6]. The general workflow involves calculating molecular descriptors for compounds with known activity, using statistical methods to build a model that links these descriptors to the activity, and then using the validated model to predict the activity of new, untested compounds [7].

Molecular Descriptors can be one-dimensional (1D), such as molecular weight or hydrogen bond count; two-dimensional (2D), derived from the molecular graph and including topological indices; or three-dimensional (3D), capturing spatial attributes like molecular volume and stereochemistry [1]. The choice of statistical method for model building depends on the data characteristics. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) are common for linear relationships, while machine learning techniques like Support Vector Machines (SVM) can handle non-linearity [1]. A critical final step is model validation using techniques like cross-validation and external test sets to ensure the model's predictive robustness and avoid overfitting [1] [7].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore model is an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features that are necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger its pharmacological response [1] [6]. It captures the essential molecular interactions—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—and their relative spatial arrangement, without being tied to a specific chemical scaffold [5]. This makes pharmacophore models exceptionally useful for scaffold hopping, the process of identifying novel chemotypes that possess the same critical interaction capabilities as known active ligands [2]. Once developed, these models can be used as 3D queries to perform virtual screening of large compound databases to identify new potential hit compounds [5].

Molecular Similarity and Machine Learning

Foundational to LBDD is the similarity principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to have similar properties [4]. This principle is often implemented through similarity searching in chemical databases using molecular fingerprints or other 2D/3D descriptors [1]. More recently, machine learning (ML) algorithms have been increasingly employed to build robust predictive models for both activity (QSAR) and physicochemical properties (QSPR) [8] [2]. These ML models can uncover complex, non-linear patterns within large chemical datasets that may be missed by traditional statistical methods, further enhancing the power and predictive accuracy of LBDD campaigns [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary LBDD Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Requirements | Primary Output | Best Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | Quantitative relationship between molecular descriptors and biological activity [1]. | Set of compounds with known biological activities and calculated descriptors [7]. | Predictive mathematical model for activity [1]. | Lead optimization; predicting potency of analog series. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identification of essential steric/electronic features for bioactivity [1] [6]. | Multiple known active ligands (and sometimes inactives) for a target [5]. | 3D spatial query of essential features [5]. | Virtual screening for novel scaffolds (scaffold hopping) [2]. |

| Similarity Searching | Similar molecules have similar activities [4]. | One or more known active compound(s). | Ranked list of compounds similar to the query. | Early-stage hit identification from large databases. |

LBDD Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, executable protocols for core LBDD workflows, from data curation to model application.

Protocol: Developing a Robust QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a validated QSAR model, based on a study of anticancer compounds on a melanoma cell line [7].

I. Data Curation and Preparation

- Data Collection: Curate a set of chemical structures and their corresponding biological activity values (e.g., IC₅₀, GI₅₀, Ki). The dataset should be as congeneric as possible. Example: Retrieve 70 compounds and their pGI₅₀ activities from a database like the National Cancer Institute (NCI) [7].

- Structure Optimization: Convert 2D structures into 3D models. Clean and minimize the structures using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MM2) to remove strain. Follow with more advanced optimization using methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311G(d) level to obtain equilibrium geometries [7].

- Descriptor Calculation: Use software toolkits like PaDEL to calculate a wide range of molecular descriptors from the optimized 3D structures [7].

II. Data Splitting and Model Building

- Training/Test Set Division: Split the dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) for model development and a test set (20-30%) for external validation. Use algorithms like the Kennard-Stone method to ensure representative sampling of the chemical space [7].

- Descriptor Selection and Model Generation: Use a variable selection algorithm such as the Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA) to identify the most relevant, non-redundant descriptors. Build the model using a regression technique like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) [7].

III. Model Validation and Application

- Statistical Validation: Evaluate the model using the training set with metrics including the squared correlation coefficient (R²) and the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²cv). Example: A robust model may have R² = 0.885 and Q²cv = 0.842 [7].

- External Validation: Assess the model's predictive power on the untouched test set using the predictive R² (R²pred). Example: A model with R²pred = 0.738 is considered predictive [7].

- Define Applicability Domain (AD): Establish the chemical space domain for which the model can make reliable predictions. Use methods like the leverage approach to identify when a new compound is outside the model's AD [7].

- Activity Prediction: Use the validated model to predict the activity of newly designed compounds before they are synthesized.

Diagram 1: QSAR model development and validation workflow.

Protocol: Pharmacophore Model Generation and Virtual Screening

This protocol describes the creation of a pharmacophore model and its use in screening compound libraries.

I. Input Ligand Preparation

- Select a Training Set: Assemble a set of known active ligands that are structurally diverse but share a common mechanism of action. Including known inactive compounds can also help refine the model.

- Conformational Sampling: For each ligand in the training set, generate a representative ensemble of low-energy conformations using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) or stochastic methods. Accurate sampling is critical for capturing the bioactive conformation [1].

II. Model Generation and Validation

- Feature Identification and Alignment: Use pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., in Schrödinger or MOE) to identify common chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings) across the active ligands. The algorithm will then superimpose the ligand conformations to find the best spatial overlap of these features.

- Model Validation: Validate the generated model by testing its ability to correctly discriminate between known active and inactive compounds not used in the training set.

III. Database Screening

- Prepare a Virtual Library: Convert a commercial (e.g., ZINC) or in-house compound database into a searchable 3D format, ensuring multiple conformers and protonation states are considered [5].

- Run Pharmacophore Query: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D search query against the prepared database.

- Analyze and Prioritize Hits: Examine the top-matching compounds, considering the fit value and visual inspection of the alignment with the model. Select promising hits for subsequent in vitro testing.

Successful LBDD relies on a suite of software, data, and computational resources. The table below catalogs key solutions used in the field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LBDD

| Category | Item/Solution | Function in LBDD | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | Cheminformatics Suites | Calculate molecular descriptors, build QSAR/pharmacophore models, and perform virtual screening. | Commercial: Schrödinger Suite, MOE, OpenEye [5]. Open-Source: PaDEL descriptor calculator [7]. |

| Conformational Sampling Tools | Generate ensembles of low-energy 3D conformations for ligands, which is crucial for pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR. | Molecular dynamics (MD) codes: CHARMM, AMBER, GROMACS [5] [1]. | |

| Scaffold Hopping Tools | Identify novel chemotypes that match a given pharmacophore or shape, enabling lead diversification. | Cresset's Spark [2]. | |

| Data Resources | Compound Databases | Source of commercially available compounds for virtual screening and of bioactivity data for model training. | ZINC (90+ million purchasable compounds) [5], ChEMBL, PubChem [9]. |

| Bioactivity Databases | Provide publicly available structure-activity data for building and validating LBDD models. | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [9]. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the necessary computing power for intensive tasks like MD simulations, conformational analysis, and large-scale virtual screening. | GPU-accelerated computing clusters can significantly speed up calculations [5]. |

Concluding Remarks

Ligand-Based Drug Design stands as an indispensable paradigm in computational medicinal chemistry, effectively bridging the knowledge gap when target structures are elusive. By leveraging the chemical information encoded in known active compounds, LBDD empowers researchers to derive predictive models and abstract functional patterns that guide the rational design of novel therapeutics. The integration of advanced molecular modeling, robust statistical and machine learning techniques, and the vast chemical data now available ensures that LBDD will remain a vital component of the drug discovery arsenal. As computational power and algorithms continue to evolve, the accuracy, scope, and impact of LBDD strategies are poised to expand further, solidifying their role in delivering the next generation of effective medicines.

The "molecular similarity principle" stands as a foundational concept in ligand-based drug design (LBDD), asserting that structurally similar molecules are more likely to exhibit similar biological activities [10]. This principle underpins a wide array of computational methods used in drug discovery when three-dimensional structural information for the biological target is unavailable [11] [12]. By exploiting the structural and physicochemical similarities between known active compounds and unknown candidates, researchers can efficiently identify and optimize novel drug leads, significantly accelerating the drug discovery pipeline [13].

This article explores the central role of molecular similarity in predicting bioactivity, detailing key methodologies such as pharmacophore modeling, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR), and modern machine learning approaches. We provide detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in implementing these powerful LBDD techniques, complete with validated workflows, necessary reagent solutions, and visualization tools to facilitate practical application in drug development settings.

Key Methodological Frameworks

Pharmacophore Modeling and Similarity Searching

A pharmacophore represents the essential three-dimensional arrangement of molecular features responsible for a ligand's biological activity, including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups [13]. Pharmacophore modeling translates this abstract concept into a computable query for virtual screening.

Protocol 2.1.1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

- Objective: To create a pharmacophore model from a set of known active ligands for virtual screening.

- Materials: A congeneric series of 20-30 compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or Ki values); computational software such as Discovery Studio [5] or OpenEye ROCS [14].

- Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collect and prepare a diverse set of active ligands. Generate energetically reasonable 3D conformations for each ligand using a tool like OMEGA [14].

- Molecular Alignment: Superimpose the ligand conformations based on their common pharmacophoric features using automated algorithms (e.g., HipHop or HypoGen) [13].

- Feature Identification: Analyze the aligned ensemble to identify conserved chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings) critical for biological activity.

- Model Validation: Assess the model's quality by its ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds in a test dataset. Use statistical measures like the Guner-Henry score or enrichment factor.

Application Note: Pharmacophore models are highly effective for "scaffold hopping"—identifying novel chemotypes that maintain the crucial pharmacophore pattern, thereby enabling the discovery of structurally distinct compounds with the desired bioactivity [15] [10].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

QSAR is a computational methodology that quantifies the relationship between the physicochemical/structural properties (descriptors) of a series of compounds and their biological activity [11] [12]. The resulting model can predict the activity of new, untested compounds.

Protocol 2.2.1: Developing a 3D-QSAR Model using CoMFA/CoMSIA

- Objective: To build a predictive 3D-QSAR model that correlates molecular fields with biological activity.

- Materials: A dataset of compounds with measured biological activity; molecular modeling software with 3D-QSAR capabilities (e.g., SYBYL for CoMFA/CoMSIA).

- Procedure:

- Molecular Alignment: Superimpose all molecules in the training set according to a common pharmacophore or a reference molecule's bioactive conformation.

- Descriptor Calculation: Place the aligned molecules within a 3D grid. Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) field energies at each grid point for CoMFA. For CoMSIA, calculate additional similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields [11].

- Model Building: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the field descriptors with the biological activity values [12].

- Model Validation: Perform internal validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out cross-validation to obtain q²) and external validation by predicting the activity of a test set not used in model building [12].

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for QSAR Model Validation

| Metric | Description | Acceptance Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| q² (LOO-CV) | Cross-validated correlation coefficient | Typically > 0.5 [12] |

| r² | Non-cross-validated correlation coefficient | > 0.8 [12] |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error | As low as possible |

| F Value | Fisher F-test statistic | Should be significant |

Application Note: The interpretative contour maps generated by CoMFA and CoMSIA visually highlight regions where specific molecular properties (e.g., increased steric bulk or electronegativity) enhance or diminish biological activity, providing direct guidance for lead optimization [11].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Molecular Similarity

Advanced machine learning models have dramatically enhanced the ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships between molecular structure and bioactivity [16] [13].

Protocol 2.3.1: Building a Machine Learning Model for Bioactivity Prediction

- Objective: To train a model that predicts bioactivity from molecular fingerprints or descriptors.

- Materials: A large dataset of compounds with annotated bioactivity (e.g., from ChEMBL [16]); programming environment (e.g., Python); machine learning libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, DeepChem).

- Procedure:

- Descriptor Calculation: Encode molecules using numerical descriptors. Common choices include ECFP4 fingerprints (2D structure) [16], USRCAT (3D shape and pharmacophore) [16], or physicochemical properties.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning algorithm on the training set. Options include:

- Random Forest / Support Vector Machines (SVMs): Effective for structured data and smaller datasets [13].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Directly learn from molecular graph structures, capturing complex topological features [16].

- Chemical Language Models (CLMs): Treat molecules as text sequences (e.g., SMILES) to generate novel bioactive structures [16].

- Model Evaluation: Assess the model's predictive performance on a held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression or AUC-ROC for classification.

Application Note: Models like DRAGONFLY and TransPharmer integrate deep learning with interactome data (drug-target networks) or pharmacophore fingerprints, enabling "zero-shot" or conditioned de novo design of novel bioactive molecules with high predicted affinity and synthesizability [16] [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of LBDD relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LBDD

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in LBDD |

|---|---|---|

| ROCS (OpenEye) [14] | Software | Rapid 3D shape and chemical feature similarity searching for virtual screening. |

| OMEGA (OpenEye) [14] | Software | Rapid generation of small molecule conformer libraries for 3D modeling. |

| ZINC Database [5] | Database | A publicly accessible repository of commercially available compounds for virtual screening (~90 million molecules). |

| ChEMBL Database [16] | Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing binding affinities and ADMET information. |

| CHARMM/AMBER [5] | Force Field | Empirical energy functions for molecular mechanics simulations and geometry optimization. |

| DRAGONFLY [16] | Deep Learning Model | Interactome-based deep learning for de novo molecular design, combining graph and language models. |

| TransPharmer [15] | Deep Learning Model | A generative model using pharmacophore fingerprints to design novel bioactive ligands. |

Integrated Workflows and Visualization

Combining ligand-based and structure-based methods in a sequential or parallel workflow can leverage their complementary strengths and mitigate individual weaknesses [17].

Diagram 1: A sequential LB-SB virtual screening workflow.

Case Study 4.1: Combined VS for HDAC8 Inhibitors [17] A successful application of a sequential workflow involved identifying histone deacetylase 8 (HDAC8) inhibitors. Researchers first screened a 4.3-million-compound library using a ligand-based pharmacophore model. The top 500 hits were subsequently filtered using ADMET criteria and then evaluated by structure-based molecular docking. This integrated approach led to the identification of compounds SD-01 and SD-02, which demonstrated potent inhibitory activity with IC₅₀ values of 9.0 and 2.7 nM, respectively.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of information and decision points within a standard ligand-based drug design campaign.

Diagram 2: The iterative ligand-based drug design cycle.

Key Scenarios for Employing LBDD in Drug Discovery Projects

Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) represents a foundational computational approach employed in drug discovery when three-dimensional structural information of the biological target is unavailable or limited [12]. This methodology derives critical insights from the known chemical structures and physicochemical properties of molecules that interact with the target of interest, enabling researchers to identify and optimize novel bioactive compounds through indirect inference [12] [18]. As a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design (CADD), LBDD operates on the fundamental principle that structurally similar molecules often exhibit similar biological activities—the "similarity principle" that underpins quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and pharmacophore development [12] [19]. The continued relevance and utility of LBDD in modern drug discovery stems from its ability to accelerate early-stage projects where structural data may be sparse, while complementing structure-based approaches in later stages of lead optimization [17] [19].

The strategic implementation of LBDD is particularly valuable in addressing several common challenges in pharmaceutical research, including orphan targets with unknown structures, the need for rapid hit identification, and scaffold-hopping to discover novel chemotypes with improved properties [18]. This application note delineates the key scenarios where LBDD approaches provide maximal impact, supported by quantitative data comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflow guides to facilitate implementation by research scientists and drug development professionals.

Key Application Scenarios for LBDD

Table 1: Primary Scenarios for Employing Ligand-Based Drug Design

| Scenario | Key LBDD Methods | Typical Output | Advantages Over SBDD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targets with Unknown 3D Structure | Pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, Similarity searching [12] [18] | Predictive models of activity, Novel hit compounds [12] | Applicable without protein crystallization or homology modeling [12] [19] |

| Rapid Virtual Screening | 2D/3D molecular similarity, Shape-based screening [17] [14] | Prioritized compound libraries, Enriched hit rates [17] | Higher throughput for screening ultra-large libraries [19] |

| Scaffold Hopping & Lead Optimization | Pharmacophore mapping, QSAR with molecular descriptors [12] [18] | Novel chemotypes with maintained activity, Optimized potency [18] | Identifies structurally diverse compounds with similar bioactivity [17] |

| PPI Inhibitor Development | Conformationally sampled pharmacophores, 3D-QSAR [12] [18] | PPI inhibitors with validated activity [18] | Addresses challenging flat binding interfaces [18] |

| ADMET Property Prediction | QSAR models with physicochemical descriptors [12] | Predicted pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles [18] | Enables early elimination of problematic compounds [18] |

Targets with Unknown or Difficult-to-Obtain 3D Structures

LBDD approaches provide the primary computational strategy when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein remains undetermined through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy [12] [19]. This scenario frequently occurs in early-stage discovery programs for novel targets or for target classes that prove recalcitrant to structural characterization. In the development of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitors, for instance, researchers successfully employed LBDD strategies for years before the protein's crystal structure was solved, utilizing pharmacophore modeling and QSAR to guide the optimization of novel anti-inflammatory agents [20]. Similarly, LBDD enabled the discovery of novel antimicrobials targeting Staphylococcus aureus transcription without requiring the protein structure of the NusB-NusE complex [18].

The strategic advantage of LBDD in this scenario stems from its reliance solely on ligand information, circumventing the need for resource-intensive protein structure determination [12]. When structural data is unavailable, LBDD methods can leverage known active compounds to develop predictive models that capture the essential structural features required for target binding and biological activity, providing a rational foundation for compound design and optimization [12] [18].

Rapid Virtual Screening of Ultra-Large Chemical Libraries

The exponential growth of commercially available chemical space, now encompassing billions of synthesizable compounds, presents both opportunity and challenge for virtual screening initiatives [17] [19]. LBDD techniques, particularly those utilizing simplified molecular representations like 2D fingerprints or 3D shape descriptors, enable computationally efficient screening of massive compound collections at a scale that often proves prohibitive for structure-based methods like molecular docking [17].

Similarity-based virtual screening, one of the most widely used LBDD techniques, operates on the principle that structurally similar molecules tend to exhibit similar biological activities [19]. This approach can rapidly identify potential hits from large libraries by comparing candidate molecules against known active compounds using molecular descriptors [19]. The throughput advantages of LBDD become particularly evident in industrial applications where screening billions of compounds necessitates extremely efficient computational methods [19]. Following initial ligand-based enrichment, more computationally intensive structure-based approaches can be applied to the refined subset, creating an efficient hybrid workflow [17] [19].

Scaffold Hopping and Lead Optimization

Once initial hit compounds have been identified, LBDD provides powerful tools for scaffold hopping—the identification of structurally distinct compounds exhibiting similar biological activity—and systematic lead optimization [12] [18]. Pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR techniques can abstract the essential functional features responsible for biological activity from known active molecules, enabling researchers to transcend specific chemical scaffolds and identify novel chemotypes that maintain critical interactions with the target [12] [14].

In lead optimization, QSAR modeling quantitatively correlates structural descriptors with biological activity, establishing predictive mathematical relationships that guide the rational design of analogs with improved potency [12] [18]. The conformationally sampled pharmacophore (CSP) approach exemplifies advanced LBDD methodology that accounts for ligand flexibility, often yielding models with enhanced predictive capability for scaffold hopping applications [12]. These approaches enable medicinal chemists to explore structural modifications while maintaining core pharmacophoric elements, balancing potency optimization with improvements in other drug-like properties [12] [18].

Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs)

Protein-protein interactions represent an important class of therapeutic targets but often present challenges for structure-based design due to their extensive, relatively flat interfaces with limited deep binding pockets [18]. LBDD has emerged as a particularly valuable approach for PPI inhibitor development, as demonstrated in the discovery of nusbiarylins—novel antimicrobials that disrupt the NusB-NusE interaction in Staphylococcus aureus [18].

In this application, researchers developed a ligand-based pharmacophore model based on known active compounds and their antimicrobial activity, successfully identifying novel chemotypes with predicted activity against this challenging PPI target [18]. The LBDD workflow encompassed pharmacophore generation, 3D-QSAR analysis, and machine learning-based AutoQSAR modeling, culminating in the identification of promising candidates with computed binding free energies ranging from -58 to -66 kcal/mol [18]. This case study highlights how LBDD can effectively address difficult targets where traditional structure-based approaches may struggle.

ADMET Property Prediction

Beyond primary pharmacological activity, LBDD approaches play a crucial role in predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties—critical determinants of compound viability and eventual clinical success [18]. QSAR models trained on curated ADMET datasets can forecast key pharmacokinetic and safety parameters based on chemical structure alone, enabling early identification and mitigation of potential developability issues [18].

The integration of ADMET prediction into LBDD workflows allows researchers to prioritize compounds with balanced efficacy and safety profiles early in the discovery process, potentially reducing late-stage attrition [18]. These predictive models utilize molecular descriptors encoding structural and physicochemical properties known to influence biological behavior, providing valuable insights beyond primary activity measurements [12] [18].

Integrated LBDD Experimental Protocol

Phase 1: Compound and Activity Data Collection

Objective: Compile a comprehensive dataset of known active and inactive compounds with associated biological activity data to serve as the foundation for LBDD model development.

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical Databases: Commercial (e.g., ChemDiv, ZINC) or proprietary compound libraries

- Activity Data: Experimentally determined IC~50~, EC~50~, K~i~, or MIC values from standardized assays

- Software Tools: Molecular spreadsheet applications (e.g., OpenEye FILTER, Schrödinger Canvas) for descriptor calculation [14]

Procedure:

- Curate Training Set: Collect a minimum of 20-50 compounds with reliable activity data spanning at least 3-4 orders of magnitude in potency [12]. Ensure chemical diversity while maintaining a congeneric series to facilitate meaningful comparisons.

- Define Activity Thresholds: Establish criteria for classifying compounds as "active," "inactive," and "intermediate" based on biological activity measurements. For example, in antimicrobial discovery, pMIC values ≥5.0 may define actives while pMIC ≤3.0 define inactives [18].

- Calculate Molecular Descriptors: Generate comprehensive molecular descriptors including:

Phase 2: Pharmacophore Model Generation

Objective: Develop a ligand-based pharmacophore hypothesis that captures the essential structural features responsible for biological activity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software Platform: Pharmacophore modeling suite (e.g., Schrödinger PHASE, OpenEye ROCS) [18] [14]

- Conformational Sampling: Tools for comprehensive conformer generation (e.g., OpenEye OMEGA) [14]

Procedure:

- Conformational Analysis: Generate representative low-energy conformations for each training set compound using systematic search or stochastic algorithms [12] [14].

- Pharmacophore Development:

- Identify common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups) across active compounds [18]

- Exclude features present in inactive compounds to refine specificity

- Develop multiple hypotheses with varying feature combinations and spatial constraints

- Hypothesis Selection: Evaluate models using statistical scoring (e.g., survival scores, select scores) and select the optimal pharmacophore based on:

Phase 3: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

Objective: Establish quantitative mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activity to enable predictive compound design.

Materials and Reagents:

- Statistical Software: QSAR modeling platforms (e.g., OpenEye 3D-QSAR, Schrödinger QSAR) [14] or programming environments (R, Python with scikit-learn)

- Validation Tools: Cross-validation routines, external test sets, y-randomization scripts [12]

Procedure:

- Descriptor Selection: Apply feature selection algorithms (genetic algorithms, stepwise regression) to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors [12].

- Model Construction: Develop QSAR models using appropriate statistical techniques:

- Model Validation: Assess predictive power and robustness through:

Phase 4: Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Objective: Apply validated LBDD models to screen virtual compound libraries and identify novel hit candidates for experimental testing.

Materials and Reagents:

- Screening Libraries: Commercial databases (e.g., ChemDiv, Enamine, ZINC) or proprietary corporate collections [18]

- Screening Tools: Ultra-high throughput similarity search platforms (e.g., OpenEye ROCS X, FastROCS) [14]

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Pre-process screening libraries by:

- Pharmacophore Screening: Screen pre-processed libraries against the validated pharmacophore model to identify compounds matching the essential feature arrangement [18].

- Similarity Searching: Perform 2D and 3D similarity searches using known active compounds as queries:

- QSAR Prediction: Apply validated QSAR models to predict activity of database compounds and prioritize those with highest predicted potency.

- Consensus Scoring: Integrate results from multiple LBDD methods to identify consensus hits with strong support across different approaches [17] [19].

Phase 5: Hit Evaluation and Experimental Validation

Objective: Critically evaluate computational hits and select the most promising candidates for experimental confirmation.

Materials and Reagents:

- ADMET Prediction Tools: Software for predicting physicochemical properties, metabolic stability, and toxicity (e.g., OpenEye QUAPAC, pKa Prospector) [14]

- Structural Visualization: Molecular graphics software for manual inspection of proposed binding modes

- Compound Acquisition: Commercial sources or internal medicinal chemistry for compound synthesis

Procedure:

- Property Filtering: Apply ADMET criteria to eliminate compounds with unfavorable properties:

- Poor solubility, permeability, or metabolic stability predictions

- Structural alerts for toxicity or reactive functional groups [18]

- Unfavorable physicochemical properties beyond accepted drug-like space

- Structural Diversity Analysis: Select hits representing distinct chemotypes to ensure structural diversity in experimental testing [18].

- Commercial Availability/Synthesizability Assessment: Prioritize compounds that are commercially available or readily synthesizable [16].

- Experimental Testing: Subject prioritized hits to in vitro biological evaluation:

- Primary activity assays to confirm target engagement

- Counter-screening against related targets to assess selectivity

- Cytotoxicity assays to identify non-specific effects

- Iterative Optimization: Use experimental results to refine LBDD models and guide subsequent design cycles [12] [18].

Case Study: LBDD for Novel Antimicrobial Discovery

Table 2: LBDD Application in Staphylococcus aureus Antimicrobial Development

| LBDD Component | Implementation | Result/Output |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 61 nusbiarylin compounds with measured MIC values [18] | Activity range: pMIC 3.0-5.0 for model development |

| Pharmacophore Model | AADRR_1 hypothesis: 2 acceptors, 1 donor, 2 aromatic rings [18] | Survival score: 4.885; Select score: 1.608; BEDROC: 0.639 |

| 3D-QSAR Model | Based on pharmacophore alignment and PLS analysis [18] | Predictive model for novel compound activity |

| Virtual Screening | ChemDiv PPI database screened against pharmacophore [18] | 4 identified hits with predicted pMIC 3.8-4.2 |

| Validation | Docking studies and binding free energy calculations [18] | Confirmed binding to NusB target (-58 to -66 kcal/mol) |

Case Study Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LBDD Implementation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in LBDD Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ChemDiv, ZINC, Enamine, MCULE, PubChem | Sources of chemical structures for virtual screening and training set creation [18] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Schrödinger PHASE, OpenEye ROCS, MOE Pharmacophore | Development of 3D pharmacophore hypotheses from known actives [18] [14] |

| QSAR Modeling | OpenEye 3D-QSAR, Schrödinger QSAR, MATLAB, R | Construction of quantitative structure-activity relationship models [12] [14] |

| Similarity Search Tools | OpenEye FastROCS, EON, BROOD, RDKit | 2D and 3D similarity searching for scaffold hopping and lead optimization [14] |

| Descriptor Calculation | OpenEye FILTER, pKa Prospector, QUAPAC, Dragon | Computation of molecular descriptors for QSAR and compound profiling [14] |

| Conformer Generation | OpenEye OMEGA, CONFLEX, CORINA | Generation of representative 3D conformations for pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR [14] |

In the absence of a solved three-dimensional structure for a potential drug target, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) provides a powerful alternative pathway for drug discovery and lead optimization [12]. This approach relies entirely on the structural information and physicochemical properties of known active ligands to develop new drug candidates [11]. The fundamental hypothesis underpinning LBDD is that similar structural or physicochemical properties yield similar biological activity [12]. By studying a set of known active compounds, researchers can derive crucial insights into the structural requirements for binding and activity, enabling the rational design of novel compounds with improved pharmacological profiles.

LBDD methods are particularly valuable when the target structure remains unknown or difficult to resolve, and they have successfully led to the development of therapeutic agents across multiple disease areas [12] [18]. The approach typically involves analyzing a congeneric series of compounds with varying levels of biological activity to establish a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR), which can then guide the optimization of lead compounds [12]. As the number of known bioactive compounds in public databases continues to grow, the potential for LBDD to accelerate drug discovery increases correspondingly.

Core LBDD Methodologies and Data Types

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

QSAR is a computational methodology that quantifies the correlation between the chemical structures of a series of compounds and their biological activity [12]. The general QSAR workflow involves multiple consecutive steps: identifying ligands with experimentally measured biological activity, calculating relevant molecular descriptors, discovering correlations between these descriptors and the biological activity, and rigorously testing the statistical stability and predictive power of the developed model [12]. The molecular descriptors used in QSAR can encompass a wide range of structural and physicochemical properties that serve as a molecular "fingerprint" correlating with biological activity [12].

Advanced 3D-QSAR methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extend these principles to three-dimensional molecular fields, providing visual representations of the regions around molecules where specific physicochemical properties enhance or diminish biological activity [12] [11]. For example, in the development of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitors, CoMFA and CoMSIA were used to generate derivatives of 5-hydroxyindole-3-carboxylate with predicted improved affinity, based on structural and electrostatic similarities to the lead compound [11].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore model represents the essential structural features and their spatial arrangements necessary for a molecule to interact with its target and elicit a biological response [21]. It abstracts specific molecular functionalities into generalized features such as hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups. Pharmacophore models can be derived either from a set of known active ligands (ligand-based) or from the 3D structure of the target binding site (structure-based) [18].

In a recent application, researchers developed a ligand-based pharmacophore model to discover novel antimicrobials against Staphylococcus aureus by targeting bacterial transcription [18]. The model, named AADRR_1, comprised two hydrogen bond acceptors (A), one hydrogen bond donor (D), and two aromatic rings (R). This hypothesis was selected based on robust statistical scores (select score: 1.608, survival score: 4.885) and demonstrated excellent ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds [18].

The Challenge of Nonadditivity in SAR

A significant challenge in classical SAR analysis is the common occurrence of nonadditivity (NA), where the simultaneous change of two functional groups results in a biological activity that dramatically differs from the expected contribution of the individual changes [22]. Systematic analysis of both pharmaceutical industry data and public bioactivity data reveals that significant nonadditivity events occur in 57.8% of inhouse assays and 30.3% of public assays [22]. Furthermore, 9.4% of all compounds in the analyzed pharmaceutical database and 5.1% from public sources displayed significant additivity shifts [22].

Nonadditivity presents substantial challenges for traditional QSAR models and machine learning approaches, as these methods often struggle to predict nonadditive data accurately [22]. Identifying and understanding nonadditive events is crucial for rational drug design, as they may indicate important SAR features, variations in binding modes, or fundamental measurement errors [22].

Table 1: Key LBDD Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique | Core Principle | Typical Application | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D/3D QSAR | Establishes mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activity | Lead optimization for congeneric series | Quantitative predictions of activity; Handles large datasets |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies essential 3D arrangement of structural features | Virtual screening; Scaffold hopping | Not limited to congeneric series; Intuitive interpretation |

| Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Analysis | Systematic identification of small structural changes and their effects on properties | SAR transfer; Medchem optimization | Simple interpretation; Identifies consistent transformation effects |

| Shape-Based Screening | Compares molecular shape and electrostatic properties | Identifying novel chemotypes with similar binding potential | Can find structurally diverse compounds with similar binding |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Developing a QSAR Model

Objective: To construct a statistically robust QSAR model for predicting the biological activity of novel compounds.

Materials and Software:

- A dataset of compounds with reliable biological activity measurements (IC₅₀, Ki, EC₅₀, etc.)

- Molecular modeling software (Schrödinger, MOE, OpenEye, or open-source alternatives)

- Statistical analysis environment (R, Python, or built-in software modules)

Procedure:

Data Curation and Preparation

- Collect a series of 20-50 congeneric compounds with experimentally determined biological activity values [12].

- Convert activity values to negative logarithmic scale (pIC₅₀, pKi, etc.) for linear regression analysis.

- Apply appropriate chemical standardization: neutralize charges, generate canonical tautomers, and clear unknown stereochemistry [22].

Molecular Descriptor Generation

- Optimize the 3D geometry of each compound using molecular mechanics or quantum chemical methods [12].

- Calculate relevant molecular descriptors (electronic, steric, hydrophobic, topological) using software such as Dragon, RDKit, or MOE.

- Select descriptors with sufficient variance and low intercorrelation to avoid overfitting.

Model Development and Validation

- Split the dataset into training (70-80%) and test (20-30%) sets using rational methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone).

- Use statistical methods like Partial Least Squares (PLS) or Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) to build the model [12].

- Validate the model internally using cross-validation (leave-one-out or k-fold) and calculate Q² [12].

- Validate the model externally using the test set and calculate predictive R².

- Apply domain of applicability analysis to define the model's reliable prediction scope.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If the model shows poor predictive power (Q² < 0.5), consider expanding the chemical diversity of the dataset or exploring different descriptor sets.

- If overfitting occurs (high R², low Q²), reduce the number of descriptors or apply regularization techniques.

Protocol 2: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

Objective: To identify novel hit compounds using a pharmacophore model for database screening.

Materials and Software:

- A set of known active compounds (minimum 3-5 highly active compounds for model generation)

- Inactive compounds (if available, to improve model selectivity)

- Database of screening compounds (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house collections)

- Pharmacophore modeling software (Schrödinger PHASE, MOE, Catalyst)

Procedure:

Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Select a diverse set of active compounds representing different chemical scaffolds but common biological activity.

- Conformational analysis: generate a representative set of low-energy conformers for each compound.

- Identify common pharmacophore features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups) across the active molecules.

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses and select the best model based on statistical scores (survival score, site score, vector score) [18].

Model Validation

- Test the model's ability to discriminate known active compounds from inactive ones using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis [18].

- Calculate enrichment factors (EF) to assess the model's performance in virtual screening.

- Verify that the model aligns with known SAR data, if available.

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Screen a database of compounds (commercial or in-house) using the validated pharmacophore model.

- Apply appropriate ADMET filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties.

- Visually inspect the top-ranking hits to verify sensible alignment with the pharmacophore features.

- Select 20-50 compounds for experimental testing based on pharmacophore fit, chemical diversity, and commercial availability.

Validation: The workflow should successfully identify known active compounds when applied to a test set containing both active and inactive molecules. A successful model typically achieves an enrichment factor >10 and area under the ROC curve >0.7.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LBDD

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in LBDD | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ZINC15, ChEMBL, PubChem | Sources of known bioactive compounds and screening libraries; provide structural and bioactivity data | Publicly available (ZINC: https://zinc15.docking.org) |

| Molecular Modeling Software | Schrödinger Suite, MOE, OpenEye, RDKit | Small molecule optimization, descriptor calculation, pharmacophore modeling, QSAR analysis | Commercial and open-source options |

| Descriptor Calculation Tools | Dragon, PaDEL, RDKit | Generation of molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling | Commercial and open-source options |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Schrödinger PHASE, MOE Pharmacophore, Catalyst | Create, validate, and use pharmacophore models for virtual screening | Commercial software |

| SAR Analysis Tools | Matched Molecular Pair analysis, R-group decomposition | Systematic analysis of structural changes and their effects on activity | Available in major modeling suites and open-source packages |

Case Study: Antimicrobial Discovery Targeting Staphylococcus aureus

In a recent application of LBDD, researchers developed novel antimicrobials against Staphylococcus aureus by targeting bacterial transcription through inhibition of the NusB-NusE protein-protein interaction [18]. The study utilized a dataset of 61 nusbiarylin compounds with known antimicrobial activity against S. aureus.

The LBDD workflow integrated multiple computational approaches:

- A ligand-based pharmacophore model (AADRR_1) was developed using the PHASE module, containing two hydrogen bond acceptors, one hydrogen bond donor, and two aromatic rings.

- A 3D-QSAR model was built to visualize how chemical modifications influence antimicrobial activity and predict activities of new compounds.

- An AutoQSAR model using machine learning methods validated the predictions from the 3D-QSAR model.

- ADME/T calculations filtered out compounds with undesirable properties.

This integrated approach identified four promising compounds (J098-0498, 1067-0401, M013-0558, and F186-026) as potential antimicrobials against S. aureus, with predicted pMIC values ranging from 3.8 to 4.2. Docking studies confirmed that these molecules bound tightly to NusB with favorable binding free energies ranging from -58 to -66 kcal/mol [18].

Table 3: Statistical Performance of LBDD Models in Antimicrobial Discovery

| Model Type | Statistical Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore (AADRR_1) | Select Score | 1.608 | Quality of hypothesis fit |

| Survival Score | 4.885 | Overall model quality | |

| BEDROC | 0.639 | Early recognition capability | |

| 3D-QSAR | R² | 0.904 | Good explanatory power |

| Q² | 0.658 | Good predictive capability | |

| Pearson-R | 0.872 | Good correlation coefficient |

Advanced Applications: Integrating LBDD with Structure-Based Methods

While LBDD is powerful on its own, its integration with structure-based methods creates a synergistic approach that leverages the advantages of both techniques [17]. Three primary strategies have emerged for combining ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening:

Sequential Approaches: The virtual screening pipeline is divided into consecutive steps, typically starting with faster LB methods for pre-filtering followed by more computationally intensive SB methods for the final selection [17] [23]. This strategy optimizes the tradeoff between computational cost and methodological complexity.

Parallel Approaches: Both LB and SB methods are run independently, and the best candidates identified from each method are selected for biological testing [23]. The final rank order often leads to meaningful increases in both performance and robustness over single-modality approaches.

Hybrid Approaches: These integrate LB and SB information into a single, unified method that simultaneously considers both ligand similarity and complementarity to the target structure [17] [23]. This represents the most sophisticated integration, potentially overcoming limitations of individual methods.

The selection of an appropriate strategy depends on the specific project requirements, available data, and computational resources. As both LB and SB methods continue to evolve, their strategic integration will likely play an increasingly important role in accelerating drug discovery.

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) represents a cornerstone methodology in computer-aided drug discovery, applied in scenarios where the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unknown or difficult to obtain [19] [6]. Instead of relying on direct structural information about the target protein, LBDD infers critical binding characteristics from the physicochemical properties and structural patterns of known active molecules [19] [1]. This approach stands in contrast to Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD), which requires detailed three-dimensional structural information of the target, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques [6]. The strategic advantage of LBDD becomes particularly evident during the early stages of drug discovery when structural information is sparse, offering distinct benefits in speed, resource efficiency, and broader applicability across diverse target classes [19] [1].

For researchers engaged in hit identification and lead optimization, LBDD provides a powerful suite of computational tools that can significantly accelerate the discovery pipeline. By leveraging known structure-activity relationships (SAR), LBDD enables the prediction and design of novel compounds with improved biological attributes even in the absence of target structural data [1]. This application note delineates the quantitative advantages, detailed methodologies, and practical implementation protocols for harnessing LBDD in contemporary drug discovery campaigns.

Core Advantages of LBDD

The strategic implementation of LBDD offers three distinct categories of advantages that address critical challenges in modern drug discovery. The comparative analysis below quantifies these benefits relative to structure-based approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of LBDD versus SBDD Approaches

| Parameter | LBDD Approach | SBDD Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Dependency | No target structure required [6] | Requires 3D target structure [19] |

| Computational Speed | High-throughput screening of trillion-compound libraries [24] | Docking billions of compounds computationally intensive [25] |

| Resource Requirements | Significant reduction in experimental screening time and cost [6] | Dependent on expensive structural biology techniques [6] |

| Target Applicability | Suitable for membrane proteins, GPCRs, and targets without solved structures [1] | Limited to targets with solved or predictable structures [19] |

| Data Requirements | Requires sufficient known active compounds for model building [19] | Requires high-quality structural data [19] |

| Scaffold Hopping Capability | Excellent for identifying novel chemotypes via similarity searching [24] | Limited by binding site complementarity [19] |

Operational Speed and Efficiency

LBDD techniques enable exceptionally rapid virtual screening operations, significantly accelerating early-stage hit identification. Modern LBDD platforms can efficiently navigate trillion-sized chemical spaces to identify compounds similar to known actives, a process that dramatically outperforms traditional experimental screening in terms of speed [24]. The underlying efficiency stems from the computational tractability of similarity comparisons compared to the more computationally intensive molecular docking procedures used in SBDD [19] [25]. This speed advantage translates directly to reduced project timelines, allowing research teams to rapidly prioritize synthetic efforts and experimental testing.

Resource Optimization

The resource-efficient nature of LBDD manifests through multiple dimensions of the drug discovery process. By employing computational filtering before synthesis and testing, LBDD minimizes costly experimental procedures [6]. Virtual screening based on ligand similarity or quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models can process millions of compounds in silico, focusing resource-intensive synthetic chemistry and biological testing only on the most promising candidates [19] [1]. This strategic resource allocation becomes particularly valuable in academic settings or small biotech companies where research budgets are constrained.

Broad Applicability

LBDD demonstrates exceptional versatility across biologically significant but structurally challenging target classes. Notably, more than 50% of FDA-approved drugs target membrane proteins such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), nuclear receptors, and transporters [1]. For these targets, obtaining high-resolution three-dimensional structures remains technically challenging, making LBDD the preferred methodological approach [1]. This applicability extends to novel targets without structural characterization, enabling drug discovery campaigns against emerging biological targets of therapeutic interest.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

Similarity-based virtual screening operates on the fundamental principle that structurally similar molecules tend to exhibit similar biological activities [19]. This methodology employs computational comparison techniques to identify novel candidate compounds from large chemical databases based on their resemblance to known active molecules.

Protocol 1: Similarity-Based Screening Using Molecular Fingerprints

Step 1: Query Compound Selection and Preparation

- Select known active compound(s) with confirmed biological activity against the target of interest

- Generate canonical Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification (SMILES) representations

- Remove salts and standardize tautomeric states using chemoinformatics toolkits

- Generate 2D molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS keys) [1]

Step 2: Database Preparation

- Obtain compound database from commercial vendors or internal collections

- Apply standard chemical standardization protocols (neutralization, desalting)

- Generate identical fingerprint representations for all database compounds

- Implement appropriate chemical space indexing for rapid similarity searching [24]

Step 3: Similarity Calculation

- Select appropriate similarity metric (Tanimoto coefficient recommended)

- Calculate similarity between query fingerprint and all database compounds

- Apply similarity threshold (typically >0.7-0.8 for scaffold hopping) [24]

- Rank compounds by descending similarity score

Step 4: Result Analysis and Hit Selection

- Visualize chemical structures of top-ranking compounds

- Apply additional filters (drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility)

- Select diverse chemotypes from high-ranking compounds for experimental testing

Figure 1: Similarity-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR modeling establishes mathematical relationships between chemical structure descriptors and biological activity, enabling predictive assessment of novel compounds [1]. This approach facilitates lead optimization by quantifying the structural features that contribute to potency and selectivity.

Protocol 2: 2D-QSAR Model Development and Application

Step 1: Dataset Curation

- Compile structurally diverse compounds with consistent biological activity data

- Ensure adequate sample size (>30 compounds recommended)

- Divide dataset into training (70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) using rational division methods

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Compute comprehensive set of 2D molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, hydrophobic)

- Apply descriptor pre-processing (normalization, variance filtering)

- Remove highly correlated descriptors (|r| > 0.95) to reduce multicollinearity [1]

Step 3: Model Building

- Select appropriate machine learning algorithm (Random Forest, PLS, SVM)

- Implement feature selection (genetic algorithm, stepwise selection)

- Train model using training set compounds

- Validate model using internal cross-validation (leave-one-out, k-fold)

Step 4: Model Validation

- Apply model to external test set for predictivity assessment

- Calculate validation metrics (R², Q², RMSE, MAE) [26]

- Perform y-randomization to confirm model robustness

Step 5: Model Application

- Screen virtual compound libraries using validated QSAR model

- Prioritize compounds with predicted high activity

- Select candidates spanning diverse structural classes for synthesis and testing

Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling identifies the essential steric and electronic features responsible for molecular recognition and biological activity [6]. This methodology provides a three-dimensional framework for designing novel compounds that maintain critical interactions with the biological target.

Protocol 3: Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation

Step 1: Conformational Analysis

- Select training set of 3-10 structurally diverse active compounds

- Generate representative conformational ensembles for each compound

- Apply energy window (typically 10-20 kcal/mol) and RMSD criteria (0.5-1.0 Å) [1]

Step 2: Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Align conformations using flexible superposition algorithms

- Identify common chemical features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups)

- Define spatial tolerances for each feature element

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses

Step 3: Hypothesis Validation

- Test ability to discriminate known actives from inactive compounds

- Select optimal hypothesis based on enrichment metrics

- Verify hypothesis robustness using external test set

Step 4: Virtual Screening

- Screen compound databases against validated pharmacophore model

- Apply geometric constraints and feature matching criteria

- Rank hits by fit value and visual inspection

- Select compounds for experimental validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of LBDD methodologies requires both computational tools and chemical resources. The following table summarizes key solutions for establishing robust LBDD capabilities.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for LBDD

| Tool Category | Representative Solutions | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, REAL Database [25] | Source of compounds for virtual screening | Provides screening libraries containing billions of commercially available compounds |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit, PaDEL, Dragon | Generation of molecular descriptors | Computes structural features for QSAR and similarity searching |

| Similarity Searching | InfiniSee [24], Scaffold Hopper [24] | Chemical space navigation | Identifies structurally similar compounds and novel chemotypes |

| QSAR Modeling | scikit-learn [26], Orange, WEKA | Machine learning model development | Builds predictive models linking structure to activity |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Phase, MOE, LigandScout | 3D pharmacophore creation and screening | Identifies essential structural features for bioactivity |

| Conformational Analysis | OMEGA, CONFLEX, CORINA | Generation of 3D conformers | Samples accessible conformational space for flexible alignment |

Integrated Workflow for Practical Implementation

The strategic integration of multiple LBDD techniques creates a synergistic effect that enhances hit identification efficiency. The following workflow represents a validated approach for practical LBDD implementation in drug discovery projects.

Figure 2: Integrated LBDD Workflow for Hit Identification

This integrated methodology begins with known active compounds and applies parallel LBDD techniques to maximize the probability of identifying novel hits. Similarity-based screening rapidly identifies structurally analogous compounds, while QSAR modeling enables activity prediction across broader chemical space. Pharmacophore modeling captures essential three-dimensional features necessary for bioactivity. The computational triaging stage applies consensus scoring to prioritize compounds identified by multiple methods, followed by experimental validation of top candidates. This approach efficiently leverages limited structural information to generate valuable lead compounds for further optimization.

Ligand-Based Drug Design represents a powerful, efficient, and broadly applicable strategy for modern drug discovery. Its advantages in speed, resource efficiency, and applicability to challenging target classes make it an indispensable component of the computational drug discovery toolkit. The methodologies and protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing LBDD in their discovery pipelines. As chemical and biological databases continue to expand and machine learning algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, the impact and utility of LBDD approaches are poised for continued growth, offering robust solutions for the ongoing challenges of drug development.

Core LBDD Methodologies and Their Real-World Applications

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, establishing mathematical relationships between the structural properties of chemical compounds and their biological activities [27] [28]. The fundamental principle underlying QSAR formalism is that differences in structural properties are responsible for variations in biological activities of compounds [28]. These methodologies have evolved significantly from classical approaches based on simple physicochemical parameters to advanced techniques incorporating the three-dimensional properties of molecules and their conformational flexibility [27] [29].

Within the context of ligand-based drug design (LBDD), QSAR approaches are particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unknown [27]. By exploiting the structural information of active ligands, researchers can develop predictive models that guide the optimization of lead compounds and prioritize candidates for synthesis and biological testing [30] [31]. This review comprehensively examines the theoretical foundations, practical applications, and experimental protocols for implementing QSAR strategies across different dimensional representations, with a particular emphasis on the transition from 2D descriptors to 3D field-based approaches.

Theoretical Foundations: The Dimensional Evolution of QSAR

The Dimensional Spectrum of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that encode various chemical, structural, or physicochemical properties of compounds, forming the basis for QSAR modeling [29]. These descriptors are systematically classified according to the level of structural representation they encompass:

- 1D Descriptors: These include global molecular properties such as molecular weight, atom counts, and functional group presence [27] [29].

- 2D Descriptors: These topological descriptors capture information derived from the molecular connection table, including topological indices, molecular connectivity, and electronic parameters such as logP [27] [30] [29].

- 3D Descriptors: These encode geometric and shape-related properties derived from the three-dimensional structure of molecules, including molecular surface area, volume, and electrostatic potential maps [27] [29] [28].

- 4D Descriptors: An extension of 3D-QSAR, these descriptors account for conformational flexibility by considering ensembles of molecular structures from molecular dynamics simulations rather than a single static conformation [27].

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Dimensions

Table 1: Comparative analysis of QSAR methodologies across different dimensions

| Dimension | Descriptor Examples | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR | Molecular weight, logP, TPSA, rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors [32] [30] | ADMET prediction, preliminary screening, high-throughput profiling [32] | Rapid calculation, alignment-independent, suitable for large datasets [32] | Limited representation of 3D structure and stereochemistry [27] |

| 3D-QSAR | Steric/electrostatic field values, molecular interaction fields [31] [28] | Lead optimization, pharmacophore mapping, activity prediction for congeneric series [31] [28] | Captures spatial molecular features, provides visual guidance for optimization [28] | Requires molecular alignment, sensitive to conformation selection [27] [28] |

| 4D-QSAR | Grid cell occupancy descriptors (GCODs) of interaction pharmacophore elements [27] | Complex ligand-receptor interactions, flexible molecular systems [27] | Accounts for conformational flexibility, multiple alignments, and induced fit [27] | Computationally intensive, complex model interpretation [27] |

Application Note 1: 2D-QSAR for Angiogenin Inhibitors in Cancer Therapeutics

Background and Objective

Angiogenin is a monomeric protein recognized as an important factor in angiogenesis, making it an ideal drug target for treating cancer and vascular dysfunctions [30]. This application note details the development of a 2D-QSAR model for small molecule angiogenin inhibitors, employing a ligand-based approach for cancer drug design when structural information of the target protein was limited [30].

Experimental Protocol

Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Compound Collection: 30 inhibitor compounds of angiogenin and their biological activities (Kᵢ) were collected from published literature [30].

- Activity Data Preparation: Kᵢ values (μM) were converted to molar units and transformed to negative logarithmic scale (pKᵢ = -log Kᵢ) to ensure a linear relationship with free energy changes [30].

- Training-Test Set Division: The dataset was divided into a training set (75%, 23 compounds) for model development and a test set (25%, 7 compounds) for validation. Division was performed by sorting compounds by biological activity to ensure both sets spanned the entire activity range [30].

- Structure Optimization: Compound structures were sketched using Maestro (Schrödinger), converted to 3D structures using LigPrep, and subjected to geometry optimization and energy minimization using MacroModel with OPLS-2005 all-atom force field [30].

Descriptor Generation and Selection

- Descriptor Calculation: 50 different 2D structural descriptors were generated using QikProp (Schrödinger) [30].

- Descriptor Filtering: 18 descriptors with constant values across the dataset were removed. The remaining 32 descriptors were selected for QSAR modeling [30].

- Multicollinearity Assessment: Descriptors were evaluated for intercorrelation to minimize redundancy in the model [30].

Model Development and Validation

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Initially applied but resulted in a mono-parametric equation due to descriptor multicollinearity [30].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression: Implemented using MINITAB software to handle correlated descriptors. The optimum number of latent variables was determined using leave-one-out cross-validation based on the lowest Predicted Residual Error Sum of Squares (PRESS) [30].

- Model Refinement: Descriptors with negligible regression coefficients were sequentially removed until reliable statistical measures were obtained [30].

- Validation Metrics: Model quality was assessed using squared correlation coefficient (R²), adjusted R², standard deviation, PRESS, F-value, and significance level (p-value). Internal validation was performed using leave-one-out cross-validation (q²) [30].

Key Findings and Research Implications

The optimized PLS-based 2D-QSAR model demonstrated that ring atoms and hydrogen bond donors positively contributed to angiogenin inhibitory activity [30]. These structural insights provide medicinal chemists with valuable guidance for designing novel angiogenin inhibitors with potential anticancer properties, highlighting how 2D-QSAR serves as an efficient preliminary screening tool in ligand-based drug design pipelines.

Application Note 2: 3D-QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling for Pyrazoline Derivatives as Antiamoebic Agents

Background and Objective

With increasing resistance to metronidazole, the standard treatment for amoebiasis caused by Entamoeba histolytica, there is an urgent need for novel therapeutic agents [31]. This application note outlines the implementation of 3D-QSAR and pharmacophore modeling for a series of 60 pyrazoline derivatives with documented activity against the HM1:IMSS strain of E. histolytica [31].

Experimental Protocol

Dataset Preparation and Molecular Modeling

- Compound Selection: 60 pyrazoline derivatives with known antiamoebic activity (IC₅₀) were retrieved from PubChem database [31].

- Activity Expression: Biological activities were converted to pIC₅₀ (-log₁₀IC₅₀) values for QSAR analysis [31].

- Training-Test Set Division: The dataset was divided into a training set (80%, 48 compounds) for model development and a test set (20%, 12 compounds) for validation [31].

- Ligand Preparation: All molecular structures were built in Maestro and prepared using LigPrep (Schrödinger), which generates 3D structures, determines ionization states at pH 7.0±2.0, adds hydrogens, and produces energy-minimized conformers using OPLS-2005 force field [31].

Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Activity Threshold Definition: Compounds with pIC₅₀ > 6 were classified as active, while those with pIC₅₀ < 5.5 were considered inactive [31].

- Feature Identification: Pharmacophore features were defined including hydrogen bond acceptors (A), donors (D), hydrophobic groups (H), and aromatic rings (R) [31].

- Hypothesis Generation: Common pharmacophore hypotheses were generated using the PHASE module (Schrödinger) with a maximum of six features [31].

- Model Selection: The top-ranked pharmacophore model was selected based on PhaseHypoScore, which evaluates alignment, vector, and activity scores [31].

Field-Based 3D-QSAR Model Development

- Molecular Alignment: Training set compounds were aligned based on the selected pharmacophore hypothesis [31].

- Field Calculation: Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor fields were computed using Gaussian field types [31].

- PLS Regression: The 3D-QSAR model was developed using Partial Least Squares regression with six components to correlate field values with biological activities [31].

- Model Validation: The model was validated both internally using cross-validation with the training set and externally using the test set compounds [31].