Leveraging QSAR for ADMET Prediction: A Guide to Accelerating Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to the application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of drug candidates.

Leveraging QSAR for ADMET Prediction: A Guide to Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to the application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of drug candidates. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of how molecular structure influences pharmacokinetics, explores the integration of classical and modern machine learning methodologies, addresses key challenges in model development and data quality, and reviews strategies for robust validation and benchmarking. By synthesizing current computational approaches, this guide serves as a resource for leveraging QSAR to de-risk the drug development pipeline and reduce late-stage attrition.

The Critical Role of ADMET Properties and QSAR Fundamentals in Drug Development

Why ADMET Properties Are a Major Cause of Drug Candidate Attrition

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties remains a critical bottleneck in drug discovery and development, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates [1]. Undesirable pharmacokinetic properties and unacceptable toxicity pose potential risks to human health and constitute principal causes of drug development failure [2]. It has been widely recognized that ADMET should be evaluated as early as possible in the drug development pipeline, as the majority of problems arising during drug discovery include unfavourable ADMET properties, which have been known to be a major cause of failure of potential molecules [3].

Traditional experimental approaches for ADMET evaluation are often time-consuming, cost-intensive, and limited in scalability [1]. The typical timeframe for drug discovery and development of a new drug spans from 10 to 15 years of rigorous research and testing, with current estimates of advancing a drug candidate to the market requiring investments exceeding USD $1 billion and failure rates above 90% [3] [4]. This review examines the fundamental reasons behind ADMET-related attrition and explores how computational approaches, particularly Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and machine learning, are revolutionizing early risk assessment in drug development.

The Multifaceted Nature of ADMET-Related Attrition

Key ADMET Properties Contributing to Failure

Drug candidates fail due to various ADMET deficiencies, which can be categorized into specific property limitations. The following table summarizes the primary ADMET properties that contribute to drug candidate attrition:

Table 1: Key ADMET Properties Contributing to Drug Candidate Attrition

| ADMET Property | Impact on Drug Development | Common Failure Modes |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Affects drug absorption and bioavailability | Poor oral bioavailability due to insufficient dissolution |

| Permeability | Determines ability to cross biological membranes | Inadequate absorption through intestinal epithelium |

| Metabolic Stability | Influences drug exposure and half-life | Rapid metabolism leading to insufficient therapeutic concentrations |

| Toxicity | Impacts safety profile and therapeutic index | Hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity (hERG inhibition), genotoxicity |

| Protein Binding | Affects volume of distribution and efficacy | Excessive plasma protein binding reducing free drug concentration |

| Drug-Drug Interactions | Influences safety in polypharmacy scenarios | CYP450 enzyme inhibition or induction |

Quantitative Impact of ADMET Properties on Attrition

Analysis of drug development pipelines reveals the significant contribution of ADMET properties to candidate failure. Studies indicate that approximately 40-50% of failures in clinical development can be attributed to inadequate pharmacokinetic profiles and safety concerns [1] [4]. The distribution of these failures across different stages of development highlights the critical need for early prediction:

Table 2: Phase-Wise Attrition Due to ADMET Properties in Drug Development

| Development Phase | Attrition Rate | Primary ADMET-Related Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Preclinical Discovery | 30-40% | Poor physicochemical properties, inadequate in vitro ADMET profiles |

| Phase I Clinical Trials | 40-50% | Human pharmacokinetics issues, safety findings in humans |

| Phase II Clinical Trials | 60-70% | Lack of efficacy often linked to inadequate exposure or distribution |

| Phase III Clinical Trials | 25-40% | Safety issues in larger populations, drug-drug interactions |

QSAR Methodologies for ADMET Prediction

Fundamental QSAR Principles and Workflow

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents an effective method for analyzing and harnessing the relationship between chemical structures and their biological activities [5]. Through mathematical models, QSAR enables the prediction of biological activity for chemical compounds based on their structural and physicochemical features. The roots of QSAR can be traced back about 100 years, with significant advancements occurring in the early 1960s with the works of Hansch and Fujita and Free and Wilson [5].

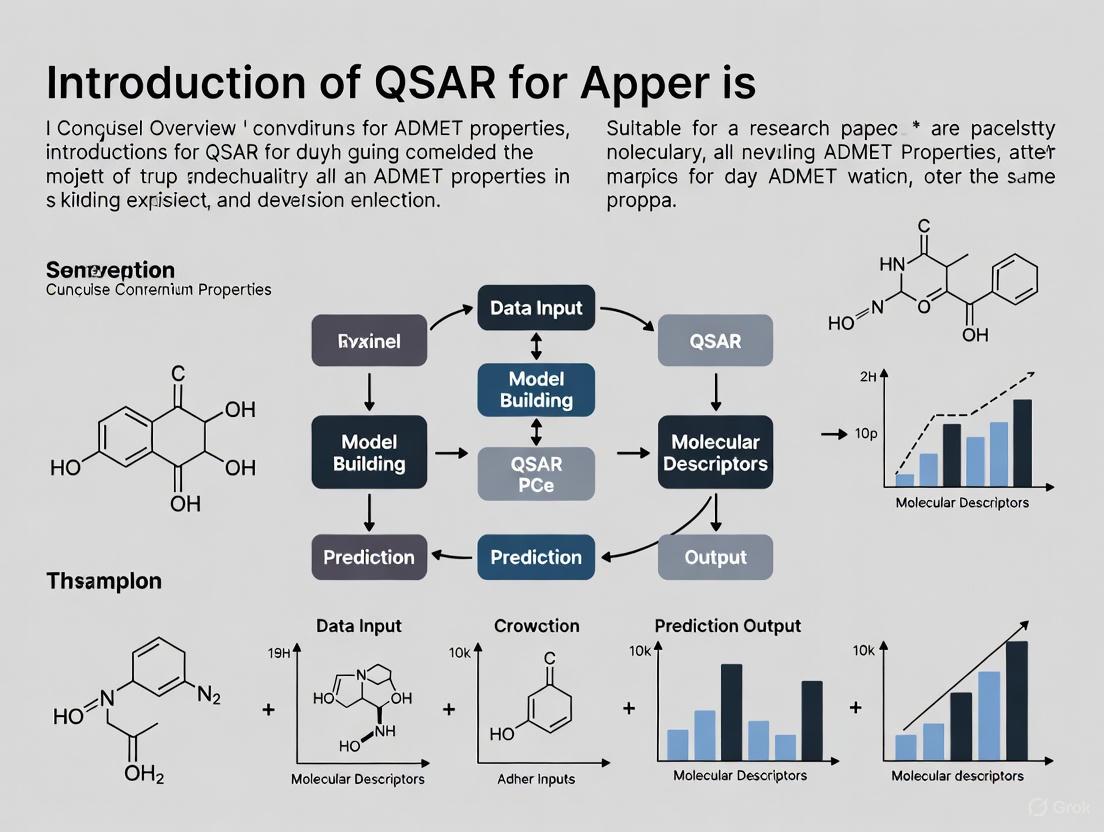

The standard QSAR methodology follows a systematic workflow from data collection to model deployment, as illustrated below:

Diagram 1: QSAR Model Development Workflow

Experimental Protocol for QSAR Model Development

Dataset Collection and Preparation

The development of a robust QSAR model begins with obtaining a suitable dataset, often from publicly available repositories tailored for drug discovery [3]. Various databases provide pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties, enabling robust model training and validation. Data preprocessing, including cleaning, normalization, and feature selection, is essential for improving data quality and reducing irrelevant or redundant information [3]. Specific steps include:

- Compound optimization using computational methods such as density functional theory at the basis set of B3LYP/6-31G* [6]

- Dataset division into training and test sets via methods like the Kennard stone algorithm or k-means clustering [7] [6]

- Molecular descriptor calculation using software such as PaDel-Descriptor or RDKit [6]

Model Building and Validation Techniques

QSAR model development employs various statistical and machine learning approaches to correlate structural descriptors with biological activities:

- Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA): Used to select optimal descriptors and generate models with high predictive power [6]

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): Employed to develop linear and non-linear QSAR models [7]

- Model validation using techniques including:

Table 3: Key Validation Parameters for QSAR Models

| Validation Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | > 0.6 | Measures goodness of fit |

| Q² (Cross-Validated Correlation Coefficient) | > 0.5 | Indicates internal predictive ability |

| R²pred (Predictive R²) | > 0.5 | Measures external predictive ability |

| cR²p (Y-Randomization) | > 0.5 | Confirms model not based on chance correlation |

Advanced 3D-QSAR Approaches

Beyond traditional 2D-QSAR, three-dimensional QSAR methods provide enhanced predictive capability by incorporating spatial molecular features:

- Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): Examines steric and electrostatic fields around molecules [8]

- Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): Extends CoMFA to include hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor fields [8]

- Molecular docking integration: Combined with 3D-QSAR to elucidate binding interactions with target proteins [8]

These advanced approaches have demonstrated excellent predictability, with CoMFA models achieving Q² = 0.73 and R² = 0.82, and CoMSIA models reaching Q² = 0.88 and R² = 0.9 in studies of Aztreonam analogs as E. coli inhibitors [8].

Machine Learning Revolution in ADMET Prediction

ML Workflow for ADMET Modeling

Machine learning has emerged as a transformative tool in ADMET prediction, offering new opportunities for early risk assessment and compound prioritization [1]. The development of a robust machine learning model for ADMET predictions follows a structured workflow:

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Workflow for ADMET Prediction

Key Machine Learning Algorithms and Applications

ML-based models have demonstrated significant promise in predicting key ADMET endpoints, outperforming some traditional QSAR models [1]. These approaches provide rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives that integrate seamlessly with existing drug discovery pipelines:

- Supervised Learning Methods: Support vector machines, random forests, decision trees, and neural networks for classification and regression tasks [3]

- Deep Learning Approaches: Message passing neural networks (MPNN) and graph neural networks for complex pattern recognition [9]

- Ensemble Methods: Gradient boosting frameworks (LightGBM, CatBoost) that combine multiple weak learners [4]

Recent benchmarking studies have revealed that the optimal model and feature choices are highly dataset-dependent for ADMET prediction tasks [9]. For instance, random forest model architecture was found to be generally best performing for many ADMET datasets, while Gaussian Process-based models showed superior performance in uncertainty estimation [9].

Integrated Computational Platforms for ADMET Assessment

Comprehensive platforms have been developed to provide researchers with integrated tools for ADMET assessment:

- admetSAR3.0: Hosts over 370,000 high-quality experimental ADMET data for 104,652 unique compounds and provides predictions for 119 endpoints using a multi-task graph neural network framework [2]

- ADMETlab 2.0: Offers integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties [1]

- Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC): Provides curated benchmarks for ADMET-associated properties, enabling standardized comparison of ML algorithms [9]

These platforms represent significant advancements over earlier tools, with admetSAR3.0 demonstrating a 78.08% increase in data records and a 108.77% increase in endpoint numbers compared to its predecessor [2].

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for ADMET and QSAR Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in ADMET/QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for QSAR modeling |

| PaDel-Descriptor | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generates 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors for model development |

| Spartan | Quantum chemistry software | Performs molecular geometry optimization using DFT methods |

| PyCaret | Machine learning library | Compares and optimizes multiple ML algorithms for property prediction |

| Chemprop | Message passing neural networks | Implements deep learning for molecular property prediction |

| admetSAR3.0 | Comprehensive ADMET platform | Provides prediction for 119 ADMET endpoints and optimization guidance |

High-quality, curated datasets are fundamental for developing reliable ADMET prediction models:

- ChEMBL: Database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties containing curated ADMET data [2]

- DrugBank: Comprehensive database containing drug and drug target information with ADMET profiles [2]

- Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC): Provides benchmark datasets and leaderboards for ADMET prediction tasks [9]

- PhaKinPro: Database containing pharmacokinetic properties for drugs and drug-like molecules [4]

The evaluation of ADMET properties remains a critical challenge in drug discovery, contributing significantly to the high attrition rates of drug candidates. Traditional experimental approaches are often inadequate for early-stage screening due to time, cost, and scalability limitations. The integration of QSAR modeling and machine learning approaches has revolutionized this field, enabling rapid, cost-effective prediction of key ADMET endpoints and facilitating early risk assessment in the drug development pipeline.

While challenges such as data quality, algorithm transparency, and regulatory acceptance persist, continued integration of computational methods with experimental pharmacology holds the potential to substantially improve drug development efficiency and reduce late-stage failures [1]. Future directions include the development of more sophisticated deep learning architectures, expanded ADMET endpoint coverage, and the incorporation of therapeutic indication-specific property profiles to guide de novo molecular design [4].

As computational power increases and high-quality ADMET datasets expand, the synergy between in silico predictions and experimental validation will continue to strengthen, ultimately reducing the burden of ADMET-related attrition in drug development and bringing effective therapies to patients more efficiently.

The process of drug discovery has been fundamentally reshaped by the evolution of screening strategies for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. For decades, the pharmaceutical industry faced a persistent challenge: promising drug candidates frequently failed in late-stage clinical development due to unforeseen pharmacokinetic or safety issues, leading to enormous financial losses and extended development timelines [10]. This economic and scientific imperative catalyzed a strategic shift from a reactive model of late-stage ADMET testing to a proactive approach that integrates predictive screening early in the discovery process [11]. The journey from cumbersome, low-throughput in vitro assays to sophisticated, high-throughput in silico prediction represents a cornerstone of modern rational drug design.

This evolution aligns perfectly with the framework of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) research, which posits that the physicochemical properties of a molecule determine its biological behavior. The core thesis of this whitepaper is that the application of QSAR principles to ADMET properties has been the driving force behind this technological transition. By establishing mathematical relationships between chemical structure and ADMET endpoints, researchers have been able to move from laborious experimental testing on single compounds to predictive modeling that can inform the design of thousands of virtual molecules before synthesis ever begins [10] [12]. This document will trace this technological progression, detail current methodologies, and provide a practical toolkit for researchers engaged in optimizing the "druggability" of new chemical entities.

The Historical Trajectory of ADMET Screening

The Era of Low-Throughput In Vitro Assays

Before the 1990s, ADMET evaluation was a low-throughput, resource-intensive endeavor. Traditional pharmacological methods required milligram quantities of each compound, which were weighed and dissolved individually, leading to a maximum throughput of only 20-50 compounds per week per laboratory [13]. Assays were typically conducted in large (∼1 ml) volumes in single test tubes, with components added sequentially. This process was not only slow and laborious but also severely limited the chemical diversity that could be explored for any new target [13].

The First Revolution: Advent of High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

The paradigm began to shift in the mid-1980s with the inception of High-Throughput Screening (HTS). A pivotal development occurred at Pfizer in 1986, where researchers substituted natural product fermentation broths with dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) solutions of synthetic compounds, utilizing 96-well plates and reduced assay volumes of 50-100 µl [14] [13]. This seemingly simple change in format was transformative, enabling a dramatic increase in capacity. Throughput jumped from 800 compounds per week at its inception to a steady state of 7,200 compounds per week by 1989 [14].

The period from 1995 to 2000 marked the logical expansion of HTS to encompass ADMET targets. Key advancements included the adaptation of the mutagenic Ames assay to a 96-well plate format and the development of automated high-throughput Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to physically detect compounds in ADME assays [14] [13]. By 1996, automated systems could screen 90 compounds per week in microsomal stability, plasma protein binding, and serum stability assays. This integration of ADME HTS into the discovery cycle by 1999 allowed for the early identification of compounds with poor pharmacokinetic profiles, embodying the emerging "fail early, fail cheap" philosophy [14] [10].

Table 1: Evolution of Screening Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

| Screening Aspect | Traditional Screening (Pre-1980s) | Early HTS (1980s-1990s) | Modern In Silico Approaches (2000s-Present) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 20-50 compounds/week | 1,000 - 10,000 compounds/week | Virtually unlimited (thousands of virtual compounds in seconds) |

| Assay Volume | ~1 ml | 50-100 µl | Not applicable |

| Compound Consumption | 5-10 mg | ~1 µg | No physical compound required |

| Primary Format | Single test tube | 96-well plate | Computational prediction |

| Key Enabling Technology | Manual pipetting | 8/12-channel pipettes, robotics | Machine Learning, AI, Cloud Computing |

| Data Output | Single endpoints, low data density | Single endpoints, higher data density | Multi-parameter ADMET profiles with confidence estimates |

The Economic and Strategic Driver: The "Fail Early, Fail Cheap" Imperative

The adoption of HTS and later in silico methods was driven by a critical economic reality. Historically, approximately 40% of drug candidates failed due to ADME and toxicity concerns [10]. With the median cost of a single clinical trial at $19 million, failures in late-stage development imposed a massive economic burden [10]. The strategic response was to integrate ADMET profiling as early as possible in the discovery pipeline. This shift from post-hoc analysis to early integration meant that problematic compounds could be identified and eliminated—or their structures optimized—before significant resources were invested [10] [11]. In silico prediction, being inherently high-throughput and low-cost, became the ultimate expression of this strategy, enabling the profiling of virtual compounds even before they are synthesized.

The Rise of In Silico ADMET and QSAR Modeling

Early Computational Chemistry and QSAR Foundations

The early 2000s marked the genesis of in silico ADMET as a formal discipline. Initial computational methods relied on foundational QSAR principles, leveraging structural biology, computational chemistry, and information technology [10]. Techniques such as 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and pharmacophore modeling were employed to identify crucial structural features responsible for interactions with ADME-relevant targets like metabolic enzymes and transporters [10]. While these methods were cost-effective and provided valuable insights, they faced limitations. The predictive accuracy for complex pharmacokinetic properties was often insufficient for critical candidate selection, partly due to the promiscuity of ADME targets and a scarcity of high-quality, publicly available data [10].

The Machine Learning and AI Revolution

The past two decades have witnessed a profound transformation driven by machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) [10]. ML algorithms, including support vector machines, random forests, and—more recently—graph neural networks and transformers, have dramatically improved predictive performance [12]. These models can automatically learn complex, non-linear relationships from large, heterogeneous datasets, moving beyond the limitations of earlier linear QSAR models.

Deep learning platforms like Deep-PK and DeepTox now enable highly accurate predictions of pharmacokinetics and toxicity using graph-based descriptors and multitask learning [12]. Furthermore, generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) are being used for de novo drug design, creating novel molecular structures optimized for desired ADMET profiles from the outset [12]. This represents the culmination of the QSAR thesis: not just predicting properties for existing structures, but using the understanding of structure-property relationships to generate new, optimal chemical matter.

Validating QSAR Models for Reliability

A critical aspect of modern in silico QSAR is rigorous validation. Reliable models are built using high-quality experimental data and validated against independent test sets to ensure their predictive power extends to new chemical scaffolds [15] [16]. For instance, researchers at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) have developed and updated QSAR models for kinetic aqueous solubility, PAMPA permeability, and rat liver microsomal stability, validating them against a set of marketed drugs. These models achieved balanced accuracies between 71% and 85%, demonstrating their utility in a discovery setting [16] [17]. Modern software platforms provide confidence estimates and define the applicable chemical space for each model, alerting users when a molecule falls outside the domain of reliable prediction [15].

Essential Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

Key In Vitro HTS ADMET Assays

Despite the rise of in silico methods, in vitro assays remain the gold standard for experimental validation and are the source of data for building computational models. The following are key Tier I ADMET assays commonly used in lead optimization.

- Kinetic Aqueous Solubility: This assay determines the dissolution rate and equilibrium solubility of a compound in aqueous buffer. Poor solubility is a major cause of low oral bioavailability. The assay is typically performed in a 96-well plate format using a nephelometric or UV-plate reader. Compounds are dissolved in DMSO and then diluted into aqueous buffer. The formation of precipitate is measured by light scattering (nephelometry) or the concentration in solution is quantified via LC-MS [16] [17].

- Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA): PAMPA is a non-cell-based model used to predict passive transcellular permeability, a key factor for intestinal absorption. The assay uses a 96-well filter plate where an artificial lipid membrane is created on a filter. A solution of the test compound is added to the donor well, and its movement through the membrane into the acceptor well is measured over time, typically using a UV-plate reader or LC-MS [16] [17].

- Microsomal Stability (e.g., Rat Liver Microsomes): This assay evaluates the metabolic stability of a compound by incubating it with liver microsomes, which contain cytochrome P450 enzymes and other drug-metabolizing enzymes. The test compound is incubated with microsomes in the presence of NADPH cofactor. Aliquots are taken at various time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes), and the reaction is quenched. The remaining parent compound is quantified using LC-MS/MS. The half-life ((t{1/2})) and intrinsic clearance ((CL{int})) are calculated from the disappearance curve of the parent compound [16] [17].

- Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Inhibition: This assay determines if a compound inhibits major CYP enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6), which is a primary cause of drug-drug interactions. Human CYP enzymes are incubated with a probe substrate and the test compound. The formation of a specific metabolite from the probe substrate is measured with and without the inhibitor (test compound) using LC-MS/MS. The IC50 value (concentration that inhibits 50% of enzyme activity) is determined.

- Ames Test for Mutagenicity: The bacterial reverse mutation assay assesses the mutagenic potential of a compound. Specially engineered strains of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli that require histidine (or tryptophan) are exposed to the test compound in a 96-well plate liquid assay. If the compound causes mutations that revert the bacteria to their prototrophic state, the bacteria will grow in a histidine-deficient medium. Growth is quantified, often using novel algorithms for automated image analysis [14] [13].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in ADMET Screening |

|---|---|

| 96/384-Well Plates | Standardized microtiter plates for conducting miniaturized, parallel assays. Enable high-throughput screening. |

| Dimethyl Sulphoxide (DMSO) | Universal solvent for preparing stock solutions of chemical compounds for both in vitro and in silico libraries. |

| Liver Microsomes (Human/Rat) | Subcellular fractions containing CYP enzymes and other metabolizing enzymes; used for in vitro metabolic stability studies. |

| Caco-2 Cells | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates into enterocyte-like monolayers; a gold standard model for predicting intestinal absorption and permeability. |

| Parallel Artificial Membrane (PAMPA) | A synthetic lipid membrane system used to model passive gastrointestinal permeability without the complexity of cell cultures. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Analytical workhorse for quantifying compounds and metabolites in complex biological matrices with high sensitivity and specificity. |

| Specific CYP Probe Substrates (e.g., Testosterone for CYP3A4) | Enzyme-specific substrates whose metabolite formation rate is monitored to assess the inhibitory potential of a test compound. |

| Ames Test Bacterial Strains (e.g., S. typhimurium TA98, TA100) | Engineered bacteria used to detect point mutations (base-pair or frame-shift) caused by mutagenic test compounds. |

Core In Silico ADMET Workflows

The in silico prediction of ADMET properties is now an integral part of the drug discovery workflow. The following diagram illustrates a standard protocol for its application.

In Silico ADMET Prediction Workflow

Integrated Screening Strategies and Future Directions

The Modern Integrated Discovery Workflow

Today, the most effective drug discovery pipelines seamlessly integrate in silico and in vitro methods. The modern workflow is cyclical, leveraging the speed of computation to triage and design, and the reliability of experimentation to validate and refine.

Modern Integrated ADMET Screening Paradigm

Current Software Landscape for ADMET Prediction

The advancements in QSAR and AI have been operationalized through a range of sophisticated software platforms. These tools put powerful predictive capabilities into the hands of researchers.

Table 3: Key Software Platforms for In Silico ADMET and QSAR Modeling

| Software Platform | Core Strengths | Representative ADMET Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| StarDrop (Optibrium) | AI-guided lead optimization with high-quality QSAR models and intuitive visualization. | pKa, logP/logD, solubility, CYP affinity, hERG inhibition, BBB penetration, P-gp transport [15]. |

| Schrödinger | Integrated quantum mechanics, ML (DeepAutoQSAR), and free energy perturbation (FEP) for high-accuracy prediction. | Binding affinity prediction, metabolic stability, toxicity endpoints, de novo design [12] [18]. |

| MOE (Chemical Computing Group) | Comprehensive molecular modeling and cheminformatics for structure-based design. | Molecular docking, QSAR modeling, protein engineering, ADMET prediction [18]. |

| deepmirror | Augmented hit-to-lead optimization using generative AI to reduce ADMET liabilities. | Potency prediction, ADME property forecasting, protein-drug binding complex prediction [18]. |

| ADME@NCATS | Publicly available QSAR prediction service validated against marketed drugs. | Kinetic aqueous solubility, PAMPA permeability, rat liver microsomal stability [16] [17]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of in silico ADMET modeling continues to evolve at a rapid pace. Several key trends are poised to define its future:

- Explainable AI (XAI): As models become more complex, there is a growing demand for interpretability. XAI techniques help researchers understand the structural features driving a particular prediction, building trust and providing actionable insights for chemists [10].

- Hybrid AI-Quantum Frameworks: The convergence of AI with quantum computing holds the promise of performing highly accurate quantum chemical calculations on large molecular sets, potentially revolutionizing the prediction of reaction mechanisms and complex properties [12].

- Multi-Scale and Systems Pharmacology Modeling: Moving beyond single-property prediction, the field is advancing towards integrated multi-scale models that simulate a drug's behavior in a virtual human system, incorporating genomics, proteomics, and physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling [12] [18].

- Generative AI and Multi-Objective Optimization: Generative models are becoming more sophisticated, capable of designing novel compounds that simultaneously optimize multiple parameters, including potency, selectivity, and a full suite of ADMET properties, thereby accelerating the path to viable clinical candidates [12] [18].

The evolution of ADMET screening from its low-throughput in vitro origins to the current era of AI-powered in silico prediction represents a quintessential example of scientific progress driven by necessity and innovation. This journey is fundamentally aligned with the principles of QSAR, demonstrating a continuous effort to formalize the complex relationships between chemical structure and biological fate. The strategic integration of these predictive tools has enabled a paradigm shift from reactive testing to proactive design, allowing researchers to "fail early and fail cheap" and thereby increasing the overall quality and probability of success for new drug candidates. As machine learning, AI, and quantum computing continue to mature, the capacity to accurately forecast human pharmacokinetics and toxicity from molecular structure will only improve, further solidifying in silico ADMET prediction as an indispensable pillar of efficient and successful drug discovery.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a fundamental ligand-based approach for predicting the biological activity and ADMET properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) of chemical compounds. These mathematical models operate on the principle that the biological behavior of a molecule can be correlated with numerical representations of its chemical structure, known as molecular descriptors. Molecular descriptors are quantitative measures that encode specific physicochemical and structural properties of molecules, transforming chemical information into standardized numerical values suitable for statistical analysis and machine learning. The accurate prediction of ADMET properties early in the drug discovery pipeline significantly reduces experimental costs and attrition rates by identifying compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic profiles before synthesis and biological testing. This technical guide explores the core principles of molecular descriptors, their classification, and their crucial role in encoding structural and physicochemical information for QSAR modeling in ADMET research.

Fundamental Classification of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be categorized based on the dimensionality of the structural information they encode and the specific properties they represent. Understanding these classifications helps researchers select appropriate descriptors for building robust QSAR models.

Dimensionality-Based Classification

- 1D Descriptors: These are derived from the molecular formula and include bulk properties such as molecular weight (MW), atom and bond counts, and number of specific functional groups. They provide basic information about molecular size and composition [19] [20].

- 2D Descriptors: Based on the molecular topology (connection table), these include topological indices (e.g., Wiener index, Balaban index) and molecular connectivity. They encode information about molecular shape and branching patterns without explicit 3D coordinates [21] [22].

- 3D Descriptors: These require the three-dimensional structure of the molecule and capture features related to molecular shape, volume, and electrostatic potential maps. Examples include molecular surface area, volume, and dipole moment [20].

- 4D Descriptors: An advancement beyond 3D, these descriptors account for conformational flexibility by considering ensembles of molecular structures rather than a single static conformation, providing more realistic representations under physiological conditions [20].

Property-Based Classification

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Descriptors and Their Roles in Drug Design

| Descriptor | Symbol/Name | Definition | Role in ADMET and Biological Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity | logP | Partition coefficient between n-octanol and water [22] | Influences membrane permeability, absorption, and distribution [22] |

| Hydrophobicity | logD | Distribution coefficient at physiological pH (7.4) [22] | Predicts solubility and partitioning in biological systems [22] |

| Water Solubility | logS | Logarithm of aqueous solubility [23] [22] | Critical for oral bioavailability and absorption [23] [22] |

| Acid-Base Dissociation Constant | pKa | -log₁₀ of the acid dissociation constant [22] | Affects ionization state, solubility, and permeability [22] |

| Molecular Size & Bulk | MW, MV, MR | Molecular Weight, Molar Volume, Molar Refractivity [22] | Affects transport, binding affinity, and steric interactions |

Table 2: Key Electronic and Topological Descriptors and Their Significance

| Descriptor | Symbol/Name | Definition | Role in ADMET and Biological Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontier Orbital Energies | EHOMO, ELUMO | Energy of Highest Occupied/Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital [23] | Determines reactivity and charge transfer interactions [23] |

| Orbital Energy Gap | ΔE = ELUMO - EHOMO | HOMO-LUMO energy gap [23] | Related to kinetic stability and polarizability [23] |

| Absolute Electronegativity | χ = -(EHOMO + ELUMO)/2 [23] | Tendency to attract electrons | Influences binding interactions with protein targets [23] |

| Molecular Topology | Wiener (W), Balaban (J) | Indices based on molecular graph theory [23] [22] | Correlate with boiling points, molar volume, and biological activity [22] |

| Polar Surface Area | PSA | Surface area over polar atoms | Predicts cell permeability (e.g., blood-brain barrier) [23] |

Calculation of Molecular Descriptors: Methodologies and Protocols

The accurate computation of molecular descriptors requires a structured workflow involving structure preparation, geometry optimization, and descriptor calculation using specialized software tools.

Structure Preparation and Optimization Protocol

- Initial Structure Construction: Draw 2D chemical structures of all compounds in the dataset using software like ChemDraw or ChemSketch. Save the structures in a recognized format (e.g., SDF, MOL) [21].

- Force Field Optimization: Perform initial geometry optimization using molecular mechanics methods (e.g., MM2 force field) to minimize steric clashes and strain energy. A gradient convergence criterion (e.g., RMS gradient of 0.01 kcal/mol) is typically applied [21].

- Quantum Chemical Optimization: For electronic descriptors, further optimize the geometry at a higher level of theory. A standard protocol employs Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the B3LYP functional and the 6-31G(d) basis set (or 6-31G(p,d) for heavier elements). This calculates the equilibrium geometry in the gas phase [21] [23].

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized structure at the same level of theory to confirm the presence of a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain thermodynamic properties.

Descriptor Calculation Workflow

- Constitutional and Topological Descriptors: Use software such as ChemOffice, DRAGON, or PaDEL-Descriptor to compute descriptors like molecular weight, logP, topological indices, and polar surface area from the 2D structure or the force-field optimized 3D structure [23] [20].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Using the quantum-chemically optimized structure from Gaussian 09W or similar software, extract orbital energies (EHOMO, ELUMO) and the dipole moment (μm) directly from the output file. Calculate derived properties like absolute hardness (η), absolute electronegativity (χ), and the reactivity index (ω) using the following equations [23]:

- Descriptor Consolidation: Compile all calculated descriptors from different sources into a single data matrix, where each row represents a compound and each column represents a descriptor value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation

| Tool/Software Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Drawing & Editing | ChemDraw, ChemSketch [21] | 2D structure creation and initial rendering |

| Force Field Optimization | Chem3D, OpenBabel | Molecular mechanics geometry optimization |

| Quantum Chemical Calculation | Gaussian 09W, GAMESS [21] [23] | High-level geometry optimization and electronic property calculation |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit, Mordred [19] [20] | Calculation of a wide range of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors |

| QSAR Modeling Platforms | QSARINS, CORAL, KNIME, scikit-learn [24] [20] | Statistical analysis, model building, and validation |

Integration of Descriptors in QSAR for ADMET Prediction

In ADMET-focused QSAR studies, specific descriptors are critically important for predicting pharmacokinetic behavior. For instance, lipophilicity (logP) and topological polar surface area (TPSA) are strong predictors of passive intestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier penetration [22]. Water solubility (LogS) is a key parameter for predicting bioavailability, while electronic descriptors like HOMO and LUMO energies can inform metabolic stability related to redox processes [23] [22]. The acid-base character, quantified by pKa, influences the ionization state of a molecule, thereby affecting its solubility and membrane permeability across different physiological pH environments [22].

Molecular descriptors are the fundamental language that translates chemical structures into quantifiable data for predictive modeling in drug discovery. A deep understanding of how these descriptors—ranging from simple constitutional counts to complex quantum chemical indices—encode structural and physicochemical properties is essential for developing robust QSAR models. The strategic selection and accurate calculation of these descriptors, following rigorous computational protocols, enable researchers to reliably predict critical ADMET properties. This knowledge empowers medicinal chemists to design novel compounds with optimized pharmacokinetic profiles early in the drug development pipeline, ultimately increasing the likelihood of clinical success while reducing the time and cost associated with experimental attrition.

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical bottleneck in modern drug discovery and development, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of candidate drugs [3]. These properties collectively determine the pharmacokinetic profile and safety of a pharmaceutical compound within an organism, directly influencing drug levels, kinetics of tissue exposure, and ultimately, pharmacological efficacy [25]. The integration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has revolutionized this landscape by enabling the prediction of ADMET properties from molecular structure, thereby providing a cost-effective and efficient strategy for early risk assessment and compound prioritization [3]. This technical guide details the core ADMET parameters, framed within the context of QSAR research, to provide drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for optimizing compound developability.

Foundational ADMET Parameters and Their QSAR Correlates

Lipophilicity

Lipophilicity, quantitatively represented by the logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient (log P), is a fundamental physicochemical property that dominates quantitative structure-activity relationships [26]. It serves as a key descriptor for predicting a molecule's passive absorption and membrane permeability.

- Mechanistic Role: Lipophilicity governs the passive diffusion of molecules across biological membranes, a primary route for intestinal absorption and distribution into tissues and organs [25] [26]. However, excessively high lipophilicity can diminish aqueous solubility and increase metabolic clearance, often leading to a parabolic relationship between lipophilicity and biological activity.

- QSAR Foundations: The history of QSAR is deeply rooted in the correlation of biological activity with partition coefficient [26]. Lipophilicity parameters correlate strongly with numerous bulk properties such as molecular weight, volume, surface area, and parachor, particularly for apolar molecules. For polar molecules, lipophilicity factors into both bulk and polar/hydrogen-bonding components.

- Optimal Range: For drug developability, the sector defined by molecular weight <400 and cLogP <4 is associated with the greatest chance of success, though developable molecules can sometimes be found outside this range at much lower probabilities [27].

Solubility

Aqueous solubility is a critical determinant for drug absorption and bioavailability, particularly for orally administered compounds that must dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids before permeating the intestinal wall.

- QSAR Modeling Approaches: QSAR-based solubility models have been developed to predict water solubility of drug-like compounds, providing valuable tools for compound selection in screening libraries [28]. These models utilize structural descriptors to classify compounds based on their solubility characteristics, with reliable predictions confirmed through validation against experimental data.

- Absorption Implications: Poor compound solubility, alongside factors like gastric emptying time, intestinal transit time, chemical instability in the stomach, and inability to permeate the intestinal wall, can significantly reduce the extent of drug absorption after oral administration [25]. Absorption critically determines a compound's bioavailability, necessitating alternative administration routes (e.g., intravenous, inhalation) for compounds with poor solubility and absorption profiles.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Parameters in ADMET Optimization

| Parameter | Definition | QSAR Descriptors | Optimal Range for Developability | Primary Impact on ADMET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity (log P) | Logarithm of octanol-water partition coefficient | Hydrophobic substituent constants, calculated logP | <4 [27] | Absorption, membrane permeability, metabolic clearance |

| Aqueous Solubility | Concentration in saturated aqueous solution | Hydrogen bonding counts, polar surface area, molecular flexibility | Compound-dependent | Oral bioavailability, absorption rate |

| Molecular Weight | Mass of molecule | Simple count of atoms | <400 [27] | Permeability, solubility, diffusion |

| Metabolic Stability | Resistance to enzymatic degradation | Structural alerts, cytochrome P450 binding descriptors | High stability desired | Clearance, half-life, bioavailability |

Metabolic Stability

Metabolic stability determines the residence time of a drug in the body and its susceptibility to cytochrome P450 enzymes, which are responsible for metabolizing over 75% of marketed drugs [29].

- Enzyme-Specific Metabolism: The three most prominent xenobiotic-metabolizing human cytochrome P450 enzymes are CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, which collectively account for approximately 75% of total cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of clinical drugs [29]. Overreliance on a single cytochrome P450 for clearance poses a high risk of drug-drug interactions and variable pharmacokinetics due to genetic polymorphisms.

- QSAR Modeling Advances: Robust QSAR models have been developed to predict high-clearance substrates for major cytochrome P450 enzymes, enabling early identification of metabolic liabilities [29]. These models, developed using large datasets from standardized high-throughput screening protocols, can distinguish between substrates and inhibitors of these enzymes with balanced accuracies of approximately 0.7.

- Screening Assays: Standard metabolic stability assessment uses human liver microsomes (HLMs) enriched with various xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochromes P450 [29]. However, simple HLM clearance assays do not identify the specific cytochromes P450 responsible for metabolism, necessitating additional enzyme-specific studies or predictive modeling.

Computational Workflows for ADMET Prediction

QSAR and Machine Learning Approaches

The integration of machine learning (ML) models has significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of ADMET prediction, offering powerful alternatives to traditional QSAR approaches [3].

- Algorithm Selection: Common ML algorithms employed in ADMET prediction include supervised methods such as support vector machines, random forests, decision trees, and neural networks, as well as unsupervised approaches like Kohonen's self-organizing maps [3]. The selection of appropriate techniques depends on the characteristics of available data and the specific ADMET property being predicted.

- Feature Engineering: Feature quality has been shown to be more important than feature quantity, with models trained on non-redundant data achieving higher accuracy (>80%) compared to those trained on all features [3]. When dealing with imbalanced datasets, combining feature selection and data sampling techniques can significantly improve prediction performance.

- Model Development Workflow: The development of a robust machine learning model for ADMET predictions follows a systematic workflow: 1) raw data collection from public repositories; 2) data preprocessing (cleaning, normalization); 3) feature selection; 4) model training with various ML algorithms; 5) hyperparameter optimization and cross-validation; and 6) independent testing using validation datasets [3].

Diagram 1: Machine Learning Model Development Workflow for ADMET Prediction

Toxicity Prediction

Toxicity prediction represents a crucial component of ADMET assessment, with QSAR models providing valuable tools for identifying potential adverse effects.

- Computational Tools: The Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST) developed by the U.S. EPA allows users to estimate toxicity of chemicals using QSAR methodologies [30]. The software employs multiple prediction approaches including hierarchical, single-model, group contribution, nearest neighbor, and consensus methods.

- Endpoints: TEST includes models for various toxicity endpoints such as 96-hour fathead minnow LC50, 48-hour Daphnia magna LC50, Tetrahymena pyriformis IGC50, oral rat LD50, developmental toxicity, and Ames mutagenicity [30].

- Model Performance Challenges: The predictivity of QSARs for toxicity can be limited by factors including inadequate consideration of underlying data quality, lack of appropriate descriptors related to the endpoint and mechanism of action, failure to address metabolism in the modeling process, and predictions outside the model's applicability domain [31].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Key ADMET Parameters

| ADMET Parameter | Primary Experimental Assays | Experimental System | Key Measured Endpoints | QSAR Model Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Stability | Clearance assay [29] | Human liver microsomes, recombinant cytochrome P450 enzymes | Depletion over time, IC50 values | Structural fingerprints, molecular descriptors |

| CYP Inhibition | Luminescence-based inhibition assay [29] | CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 Supersomes | Inhibition potency | Electrostatic, topological descriptors |

| Cytotoxicity | Cell viability assay [32] [33] | HeLa, K562, A549 cancer cell lines | IC50 values, growth percentages | Topological distances, charge descriptors |

| Ames Mutagenicity | Bacterial reverse mutation assay [30] | Salmonella typhimurium strains | Mutation frequency | Structural alerts, electronic parameters |

Experimental Methodologies and Technical Protocols

Metabolic Stability and CYP Inhibition Assays

Standardized protocols for assessing metabolic stability and cytochrome P450 inhibition provide critical data for both experimental characterization and QSAR model development.

- Enzyme Incubation Conditions: Metabolic stability assays typically employ recombinant cytochrome P450 Supersomes (CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2D6) incubated with test compounds in the presence of an NADPH Regenerating System to maintain catalytic activity [29]. The depletion of the parent compound is monitored over time to calculate clearance rates.

- Inhibition Screening: Luminescence-based cytochrome P450 inhibition assays (P450-Glo) utilize probe substrates that generate luminescent signals upon metabolism [29]. Test compounds that reduce this signal indicate potential inhibition, though cross-referencing with clearance data is necessary to distinguish true inhibitors from competing substrates.

- Data Interpretation: Compounds with indiscriminate cytochrome P450 metabolic profiles are considered advantageous, as they present lower risk for issues with cytochrome P450 polymorphisms and drug-drug interactions [29]. Understanding the specific enzymes responsible for metabolism enables project teams to strategize or pivot when necessary during drug discovery.

Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Activity Screening

Evaluation of cytotoxic potential represents a dual-purpose assessment, both for therapeutic anticancer activity and general toxicity profiling.

- Cell-Based Assays: Cytotoxicity is typically evaluated against established human cancer cell lines such as HeLa (cervical cancer), K562 (chronic myeloid leukemia), and A549 (lung adenocarcinoma), with activity expressed as IC50 values or growth percentages [32] [33].

- QSAR Modeling of Cytotoxicity: Quantitative structure-activity relationship studies on cytotoxic activity utilize topological, ring, and charge descriptors based on stepwise multiple linear regression techniques [33]. These models have revealed that anticancer activity often depends on topological distances, number of ring systems, maximum positive charge, and number of atom-centered fragments.

Diagram 2: Interrelationship of Key ADMET Parameters in Drug Optimization

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Evaluation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in ADMET Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Systems | CYP3A4/2C9/2D6 Supersomes [29] | Enzyme-specific metabolism studies | Metabolic stability, reaction phenotyping |

| * Screening Assays* | P450-Glo Assay Kits [29] | Luminescence-based CYP inhibition screening | High-throughput inhibition profiling |

| Computational Tools | Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST) [30] | QSAR-based toxicity prediction | Prioritization of compounds for testing |

| Cell-Based Assays | HeLa, K562, A549 Cell Lines [32] [33] | Cytotoxicity and anticancer activity evaluation | Therapeutic efficacy and safety assessment |

| Metabolic Incubation | NADPH Regenerating System [29] | Maintenance of cytochrome P450 catalytic activity | In vitro metabolic stability assays |

The strategic integration of computational prediction and experimental validation of ADMET properties has transformed modern drug discovery paradigms. Foundational physicochemical parameters including lipophilicity, solubility, metabolic stability, and toxicity collectively determine compound developability, with QSAR and machine learning models providing powerful tools for their optimization. As ADMET evaluation continues to shift earlier in the discovery pipeline, the continued refinement of predictive models—coupled with robust experimental protocols—holds the potential to substantially improve drug development efficiency and reduce late-stage failures. The harmonization of computational and empirical approaches remains essential for advancing chemical entities with optimal pharmacokinetic and safety profiles toward successful clinical application.

From Classical Models to AI: Building and Applying QSAR-ADMET Workflows

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a fundamental computational tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict biological activity, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties based on molecular descriptors. Classical statistical approaches, particularly Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS), remain essential despite the emergence of more complex machine learning algorithms. These methods are esteemed for their simplicity, speed, and interpretability, especially in regulatory settings where understanding the relationship between molecular features and biological endpoints is crucial [20]. In the specific context of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) research, these models provide a transparent framework for predicting critical properties such as metabolic stability, membrane permeability, and hepatotoxicity, thereby reducing the need for resource-intensive experimental assays [34].

The foundation of QSAR modeling relies on molecular descriptors—numerical representations of chemical structures that encode various physicochemical and structural properties. These descriptors are typically categorized by dimensions: 1D descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, atom counts), 2D descriptors (e.g., topological indices, connectivity fingerprints), and 3D descriptors (e.g., molecular surface area, volume) [20]. Classical QSAR methods correlate these descriptors with biological responses using statistical regression techniques, establishing mathematically defined relationships that can guide chemical optimization in drug development pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations of MLR and PLS

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) represents one of the most straightforward and interpretable approaches in classical QSAR modeling. MLR establishes a linear relationship between multiple independent variables (molecular descriptors) and a dependent variable (biological activity or ADMET property) through a linear equation. The general form of an MLR model is expressed as:

Where Y is the predicted biological activity or ADMET property, β₀ is the intercept, β₁ to βₙ are regression coefficients representing the contribution of each descriptor, X₁ to Xₙ are molecular descriptor values, and ε is the error term [20]. The method operates on several key assumptions: linearity between dependent and independent variables, normal distribution of residuals, homoscedasticity (constant variance of errors), and absence of multicollinearity (high correlation among descriptors).

The primary advantage of MLR lies in its straightforward interpretability—each coefficient quantitatively indicates how a unit change in a particular descriptor affects the biological response. This transparency makes MLR particularly valuable in mechanistic interpretation and regulatory applications. However, MLR faces limitations when dealing with highly correlated descriptors (multicollinearity), which can inflate coefficient variances and destabilize the model. Additionally, MLR struggles with datasets where the number of descriptors approaches or exceeds the number of observations, necessitating robust feature selection methods as a preliminary step [20].

Partial Least Squares (PLS)

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was developed to address the limitations of MLR when handling datasets with numerous, collinear descriptors. Unlike MLR, which maximizes the variance explained in the response variable, PLS seeks latent variables (components) that simultaneously maximize the covariance between descriptor matrix (X) and response vector (Y). This makes PLS particularly effective for datasets with more descriptors than samples or when significant multicollinearity exists among descriptors [20] [35].

The PLS algorithm iteratively extracts these latent components through a process that decomposes both the descriptor and response matrices. The fundamental PLS model can be represented as:

Where T and U are matrices of latent vectors, P and Q are loading matrices, and E and F are error matrices. The relationship between the X and Y blocks is established through an inner regression model connecting T and U [20]. A key advantage of PLS is its ability to handle noisy, collinear, and incomplete data—common challenges in chemical descriptor datasets. By focusing on the most variance-relevant dimensions, PLS effectively reduces the impact of irrelevant descriptors while retaining those most predictive of the biological response.

PLS has proven particularly valuable in ADMET prediction, where descriptors often number in the hundreds or thousands and frequently exhibit strong correlations. For modeling ADMET properties, PLS demonstrates superior performance to MLR in many scenarios, especially with larger descriptor sets and more complex molecular representations [35].

Comparative Analysis of MLR and PLS

Table 1: Key Characteristics of MLR and PLS in QSAR Modeling

| Feature | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Partial Least Squares (PLS) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Maximizes variance explained in response variable | Maximizes covariance between descriptors and response |

| Descriptor Handling | Requires independent, non-collinear descriptors | Handles collinear descriptors effectively |

| Model Interpretation | Direct interpretation of coefficients | Interpretation via variable importance in projection (VIP) |

| Data Requirements | Number of observations > number of descriptors | Suitable for high-dimensional data (descriptors > observations) |

| Feature Selection | Mandatory preliminary step | Built-in through latent variable selection |

| Regulatory Acceptance | High due to transparency | Moderate to high with proper validation |

| Computational Complexity | Low | Moderate to high |

| Optimal Application Scope | Small, curated descriptor sets with clear mechanistic interpretation | Large descriptor sets with inherent collinearity |

Methodological Implementation

Workflow for Classical QSAR Modeling

The development of robust MLR and PLS models for ADMET prediction follows a systematic workflow encompassing data collection, preprocessing, model construction, and validation. The following diagram illustrates this standardized process:

Data Preparation and Curation

The initial phase of classical QSAR modeling involves assembling a high-quality dataset of compounds with experimentally determined ADMET properties. This process begins with chemical structure representation, typically using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) notations or molecular graph representations [36]. Following structure representation, researchers calculate molecular descriptors using software tools such as DRAGON, PaDEL, or RDKit, generating numerical representations of physicochemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight), topological features, and electronic characteristics [20].

Data curation represents a critical step to ensure model reliability. This process includes removing inorganic salts and organometallic compounds, extracting parent organic compounds from salt forms, standardizing tautomeric representations, canonicalizing SMILES strings, and addressing duplicate measurements [9]. For ADMET endpoints with highly skewed distributions, appropriate transformations (typically logarithmic) are applied to normalize the data distribution. Consistent data curation significantly enhances model performance and generalizability by reducing noise and ambiguity in the training data.

Feature Selection Strategies

For MLR modeling, feature selection is essential to address the curse of dimensionality and mitigate multicollinearity. Several established techniques facilitate this process:

- Stepwise Regression: Iteratively adds or removes descriptors based on statistical significance criteria, such as F-statistics or Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [20]

- Genetic Algorithms: Evolutionary approaches that evolve descriptor subsets toward optimal fitness (predictive performance) [20]

- LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator): Applies L1 regularization that shrinks some coefficients to zero, effectively performing feature selection [20]

- Mutual Information Ranking: Ranks descriptors based on their mutual information with the response variable, prioritizing non-linear relationships [20]

For PLS, feature selection is inherently managed through the extraction of latent components, though preliminary descriptor filtering may still enhance model interpretability and performance.

Dataset Splitting Strategies

Proper dataset division is crucial for developing statistically robust models. The standard approach partitions compounds into:

- Training Set: Used for model parameter estimation (typically 60-80% of total data)

- Test Set: Held back for final model evaluation (typically 20-40% of total data)

Splitting should maintain representativeness across subsets, often achieved through structural clustering or scaffold-based splitting to ensure structural diversity in both training and test sets [9]. For smaller datasets, cross-validation techniques (e.g., leave-one-out, leave-many-out) provide more reliable performance estimates.

Model Validation Protocols

Rigorous validation represents the cornerstone of reliable QSAR modeling for ADMET prediction. The following protocols ensure model robustness and predictive capability:

Internal Validation assesses model stability using only training set data through:

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Sequentially removes one compound, builds model on remainder, predicts removed compound

- Leave-Many-Out (LMO) Cross-Validation: Removes multiple compounds (typically 20-30%) in each iteration

- Bootstrapping: Generates multiple models from random resamples (with replacement) of the training data

Key metrics include Q² (cross-validated R²), which should exceed 0.6 for acceptable models, and Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSECV) [37].

External Validation evaluates model performance on completely independent test set compounds, providing the most realistic assessment of predictive power. Standard acceptance criteria include:

- Coefficient of determination between predicted and observed values (R²ₑₓₜ > 0.6) [37]

- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC > 0.8) [37]

- Slopes of regression lines (k and k') between 0.85 and 1.15 [37]

- rm² metric > 0.5, with Δrm² < 0.2 [37]

Additionally, the Applicability Domain should be defined to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable, typically based on leverage and residual analysis [36].

Table 2: Standard Validation Metrics for Classical QSAR Models

| Validation Type | Metric | Calculation | Acceptance Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Q² (LOO) | 1 - PRESS/SSY | > 0.6 |

| Internal Validation | RMSECV | √(∑(yᵢ-ŷᵢ)²/n) | Dataset dependent |

| External Validation | R²ₑₓₜ | 1 - ∑(yᵢ-ŷᵢ)²/∑(yᵢ-ȳ)² | > 0.6 |

| External Validation | CCC | 2rσᵧσŷ/(σᵧ²+σŷ²+(ȳ-μŷ)²) | > 0.8 |

| External Validation | rm² | r²(1-√(r²-r₀²)) | > 0.5 |

| External Validation | k, k' | Slope of regression lines | 0.85 - 1.15 |

Experimental Protocols for ADMET Modeling

Protocol 1: Developing an MLR Model for Cytotoxicity Prediction

This protocol outlines the development of an MLR model for predicting metal oxide nanoparticle (MeONP) cytotoxicity based on physicochemical properties, adapted from published QSAR studies [38].

Materials and Data Collection:

- Collect a homogeneous set of 30 MeONPs with measured cytotoxicity (e.g., IL-1β release in THP-1 cells)

- Characterize key physicochemical properties: primary particle size (TEM), hydrodynamic size (DLS), ζ-potential, dissolution rate in phagolysosomal simulated fluid (PSF)

- Apply density functional theory (DFT) computations to calculate quantum chemical descriptors

Feature Selection and Model Building:

- Pre-screen descriptors using correlation analysis to remove highly correlated variables (r > 0.9)

- Apply stepwise regression with p-value threshold of 0.05 for descriptor inclusion

- Construct final MLR model using 4-6 most significant descriptors

- Calculate regression coefficients and assess statistical significance (t-test, p < 0.05)

Model Validation:

- Perform leave-one-out cross-validation to calculate Q²

- Validate on external set of 7 independent MeONPs

- Calculate predictive accuracy (ACC) with target threshold > 0.85

- Define applicability domain using leverage approach

Protocol 2: Developing a PLS Model for Metabolic Stability Prediction

This protocol describes the development of a PLS model for predicting human metabolic stability, a critical ADMET property [9].

Materials and Data Preparation:

- Compile dataset of 2,000-5,000 compounds with measured human metabolic clearance

- Calculate comprehensive descriptor set (750+ 1D-3D descriptors) using DRAGON or PaDEL

- Apply data cleaning: standardize structures, remove inorganic salts, handle tautomers, canonicalize SMILES

- Log-transform clearance values to achieve normal distribution

Model Development:

- Preprocess X-matrix by autoscaling (mean-centering and unit variance)

- Determine optimal number of latent components using cross-validation

- Build PLS model with identified components

- Calculate Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores for descriptor ranking

Validation and Application:

- Validate using scaffold-based split to assess performance on structurally novel compounds

- Calculate R² and Q² for training and test sets

- Evaluate external predictivity on hold-out test set (20% of data)

- Apply model to virtual screening of compound libraries for lead optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Resources for Classical QSAR Modeling

| Category | Tool/Resource | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | DRAGON | Molecular descriptor calculation | 5,000+ molecular descriptors |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL-Descriptor | Molecular descriptor calculation | 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors, open-source |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit | Cheminformatics and descriptor calculation | Comprehensive Python-based toolkit |

| Statistical Analysis | QSARINS | MLR model development with validation | Advanced validation metrics, applicability domain |

| Statistical Analysis | SIMCA | PLS model development | Industrial-standard PLS implementation |

| Statistical Analysis | R (pls package) | PLS modeling | Open-source, customizable |

| Data Curation | DataWarrior | Data visualization and cleaning | Interactive chemical space visualization |

| Data Curation | Standardiser | Structure standardization | Automated structure standardization |

| Validation | CORAL | QSAR model validation | Monte Carlo optimization, IIC/CII metrics |

Applications in ADMET Research

Classical statistical approaches continue to deliver significant value in ADMET property prediction, as demonstrated by numerous successful applications:

Inflammatory Potential Prediction of Nanomaterials

QSAR models employing MLR have successfully predicted the inflammatory potential of metal oxide nanoparticles (MeONPs) based on physicochemical properties. Researchers built a comprehensive dataset of 30 MeONPs measuring interleukin (IL)-1β release in THP-1 cells, then developed QSAR models with predictive accuracy exceeding 90%. Key descriptors included metal electronegativity and ζ-potential, with models revealing that MeONPs with metal electronegativity lower than 1.55 and positive ζ-potential were more likely to cause lysosomal damage and inflammation. The models were experimentally validated against seven independent MeONPs with 86% accuracy, demonstrating the practical utility of classical approaches for nanomaterial safety assessment [38].

Metabolic Stability and Clearance Prediction

PLS regression has proven particularly effective for predicting metabolic stability, a critical ADME property. In one implementation, researchers calculated 1,426 molecular descriptors for 3,200 drug-like compounds with measured human metabolic clearance values. PLS modeling with 8 latent components achieved Q² = 0.72 and R²ₑₓₜ = 0.68 on an external test set, significantly outperforming MLR approaches (R²ₑₓₜ = 0.52). Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) analysis identified lipophilicity (AlogP), polar surface area, and hydrogen bond donor counts as the most influential descriptors, providing mechanistic insights for medicinal chemistry optimization [9].

Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Prediction

Classical QSAR approaches have successfully modeled blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, a crucial distribution property. Using a dataset of 250 compounds with measured logBB values, researchers developed an MLR model with 6 descriptors achieving R² = 0.83 and Q² = 0.79. The model identified molecular weight, topological polar surface area, and number of rotatable bonds as key predictors, aligning with known physicochemical drivers of BBB penetration. This model successfully prioritized compounds for central nervous system drug discovery programs, demonstrating the continued relevance of classical statistical methods in modern drug development [20].

Comparative Performance with Machine Learning Methods

While deep learning and other advanced machine learning methods have gained prominence in ADMET prediction, classical statistical approaches maintain important advantages in specific scenarios. Benchmarking studies demonstrate that MLR and PLS remain competitive for datasets with limited samples (n < 500) and well-defined descriptor-response relationships [35]. In one comprehensive comparison using 7,130 compounds with MDA-MB-231 inhibitory activities, traditional QSAR methods (PLS, MLR) showed significantly lower prediction accuracy (R² = 0.65) compared to machine learning methods (R² = 0.90) when using large training sets (n = 6,069). However, with smaller training sets (n = 303), MLR maintained a respectable R² value of 0.93 but showed poor external predictivity (R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹 = 0), indicating overfitting tendencies with limited data [35].

The choice between classical and machine learning approaches should be guided by dataset characteristics and project objectives. Classical methods provide superior interpretability and regulatory acceptance, while machine learning approaches may offer higher predictive accuracy for complex endpoints with large, high-quality datasets. For many ADMET properties, ensemble approaches that combine classical and machine learning methods deliver optimal performance [9].

The integration of machine learning (ML) into quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling has revolutionized the prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties in drug discovery. Traditional experimental approaches to ADMET evaluation are often time-consuming, cost-intensive, and limited in scalability, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates in later development stages [39]. The paradigm has now shifted toward in silico methods, where the ultimate goal is to identify compounds liable to fail before they are even synthesized, bringing even greater efficiency benefits to the drug discovery pipeline [40]. This transition is powered by advanced ML algorithms—including Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)—that learn complex relationships between molecular structures and pharmacokinetic properties from large-scale chemical data. The application of these techniques within the QSAR framework has moved the field beyond simple linear regression models to sophisticated predictive tools that significantly enhance the efficiency of oral drug development [41].

Core Machine Learning Algorithms in ADMET Prediction

Random Forests

Random Forests (RF) represent an ensemble learning method that operates by constructing multiple decision trees during training and outputting the mode of the classes (classification) or mean prediction (regression) of the individual trees [39]. This algorithm has demonstrated exceptional performance across various ADMET prediction tasks due to its ability to handle high-dimensional data and mitigate overfitting. In practice, RF models have been successfully applied to predict critical properties such as Caco-2 permeability, where they achieved competitive performance against other ML approaches [41]. The algorithm's inherent feature importance calculation also provides valuable insights into which molecular descriptors most significantly influence specific ADMET endpoints, offering medicinal chemists guidance for structural optimization [39].

Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) constitute an established technique for regression and classification across the spectrum of ADME properties [40]. The fundamental principle behind SVMs is the identification of a hyperplane that optimally separates data points of different classes in a high-dimensional feature space. For ADMET prediction, SVMs have been widely employed in binary classification tasks such as cytochrome P450 inhibition, P-glycoprotein substrate identification, and toxicity endpoints [42]. Their effectiveness stems from the kernel trick, which allows them to model complex, non-linear relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activities without explicit feature transformation. Studies have demonstrated that SVM-based models can achieve prediction accuracies exceeding 80% for various ADMET properties, including Ames mutagenicity (84.3%) and hERG inhibition (80.4%), making them a reliable choice for early-stage risk assessment [42].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent a transformative deep learning approach that directly processes molecular structures as graphs, where atoms constitute nodes and bonds form edges [43]. This representation bypasses the need for pre-computed molecular descriptors, instead learning task-specific features directly from the molecular topology. In typical implementation, each node/atom is described by a feature vector containing information about atom type, formal charge, hybridization type, and other atomic characteristics [43]. Message-passing mechanisms then allow information to flow between connected atoms, enabling the model to capture complex substructural patterns relevant to biological activity. GNNs have demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in predicting various ADMET properties, including solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability, often outperforming traditional descriptor-based methods [43] [44].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms on Key ADMET Properties

| ADMET Property | Random Forest | SVM | GNN | Dataset Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | R²: 0.81 [41] | Accuracy: 76.8% [42] | MAE: 0.410 [41] | 4,464-5,654 compounds [41] |

| CYP2D6 Inhibition | — | Accuracy: 85.5% [42] | AUC: 0.893 [44] | 14,741 compounds [42] |

| Ames Mutagenicity | — | Accuracy: 84.3% [42] | — | 8,348 compounds [42] |

| hERG Inhibition | — | Accuracy: 80.4% [42] | — | 978 compounds [42] |

| BBB Penetration | — | — | AUC: 0.952 [44] | 2,039 compounds [44] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Curation