Lead Compound Identification Strategies: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern lead compound identification strategies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Lead Compound Identification Strategies: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern lead compound identification strategies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of what constitutes a quality lead, explores established and emerging methodological approaches from HTS to AI-powered data mining, addresses common challenges in optimization and false-positive reduction, and discusses rigorous validation and comparative analysis of techniques. By synthesizing current methodologies and future trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for efficiently navigating the initial, critical phase of the drug discovery pipeline.

What is a Lead Compound? Defining the Cornerstone of Drug Discovery

Definition and Key Characteristics of a Lead Compound

In the context of modern drug discovery, a lead compound is a chemical entity that demonstrates promising pharmacological or biological activity against a specific therapeutic target, serving as a foundational starting point for the development of a drug candidate [1]. It is crucial to distinguish this term from compounds containing the metallic element lead; here, "lead" signifies a "leading" candidate in a research pathway [1]. The identification and selection of a lead compound represent a critical milestone that occurs prior to extensive preclinical and clinical development, positioning it as a key determinant in the efficiency and ultimate success of a drug discovery program [2].

The principal objective after identifying a lead compound is to optimize its chemical structure to improve suboptimal properties, which may include its potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetic parameters, and overall druglikeness [1]. A lead compound offers the prospect of being followed by back-up compounds and provides the initial chemical scaffold upon which extensive medicinal chemistry efforts are focused. Its intrinsic biological activity confirms the therapeutic hypothesis, making the systematic optimization of its structure a central endeavor in translating basic research into a viable clinical candidate [3].

Key Characteristics and Optimization Criteria

A lead compound is evaluated and optimized against a multifaceted set of criteria to ensure it possesses the necessary characteristics to progress through the costly and time-consuming stages of drug development. The transition from a simple "hit" with confirmed activity to a validated "lead" involves rigorous assessment of its physicochemical and biological properties.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of a Lead Compound and Associated Optimization Goals

| Characteristic | Description | Optimization Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Activity & Potency | The inherent ability to modulate a specific drug target (e.g., as an agonist or antagonist) with a measurable effect [1]. | Increase potency and efficacy at the intended target [3]. |

| Selectivity | The compound's ability to interact primarily with the intended target without affecting unrelated biological pathways [1]. | Enhance selectivity to minimize off-target effects and potential side effects [4]. |

| Druglikeness | A profile that aligns with properties known to be conducive for human drugs, often evaluated using guidelines like Lipinski's Rule of Five [1]. | Modify structure to improve solubility, metabolic stability, and permeability [1] [3]. |

| ADMET Profile | The compound's behavior regarding Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity [5] [3]. | Optimize pharmacokinetics and reduce toxicity potential through structural modifications [3]. |

The optimization process, known as lead optimization, aims to maximize the bonded and non-bonded interactions of the compound with the active site of its target to increase selectivity and improve activity while reducing side effects [2]. This phase involves the synthesis and characterization of analog compounds to establish Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR), which guide medicinal chemists in making informed structural changes [3]. Furthermore, factors such as the ease of chemical synthesis and scaling up manufacturing must be considered early on to ensure the feasibility of future development [1].

Methodologies for Lead Compound Discovery

The discovery of a lead compound can be achieved through several well-established experimental and computational strategies. The choice of methodology often depends on the available information about the biological target and the resources of the research organization.

Experimental Discovery Approaches

High-Throughput Screening (HTS): This is a widely used lead discovery method that involves the rapid, automated testing of vast compound libraries (often containing thousands to millions of compounds) for interaction with a target of interest [5] [3]. HTS is characterized by its speed and efficiency, allowing for the assessment of hundreds of thousands of assays per day using ultra-high-throughput screening (UHTS) systems. A key advantage is its ability to process enormous numbers of compounds with reduced sample volumes and human resource requirements, though it may sometimes identify compounds with non-specific binding [5] [3].

Fragment-Based Screening: This approach involves testing smaller, low molecular weight compounds (fragments) for weak but efficient binding to a target [5]. Identified fragment "hits" are then systematically grown or linked together to create more potent lead compounds. This method requires detailed structural information, often obtained from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, but offers the advantage of exploring a broader chemical space and often results in leads with high binding efficiency [5].

Affinity-Based Techniques: Techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and bio-layer interferometry (BLI) measure the binding affinity, kinetics, and thermodynamics of interactions between a compound and its target [5]. These methods provide deep insights into the strength and nature of binding, helping researchers prioritize lead candidates with optimal drug-like properties early in the discovery process [5].

Computational Discovery Approaches

Virtual Screening (VS): VS is a computational methodology used to identify hit molecules from vast libraries of small chemical compounds [2]. It employs a cascade of computer filters to automatically evaluate and prioritize compounds against a specific drug target without the need for physical screening. This approach is divided into structure-based virtual screening (which relies on the 3D structure of the target) and ligand-based virtual screening (which uses known active compounds as references) [2] [6].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulations: Molecular docking is used to predict the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target (receptor) [5] [3]. This prediction of the binding pose helps in understanding the molecular basis of activity and in optimizing the lead compound. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations then study the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing a dynamic view of the ligand-receptor interaction and its stability under near-physiological conditions [5] [7].

Data Mining on Chemical Networks: Advanced data mining approaches are being developed to efficiently navigate the immense scale of available chemical space, which can contain billions of purchasable compounds [6]. One method involves constructing ensemble chemical similarity networks and using network propagation algorithms to prioritize drug candidates that are highly correlated with known active compounds, thereby addressing the challenge of searching extremely large chemical databases [6].

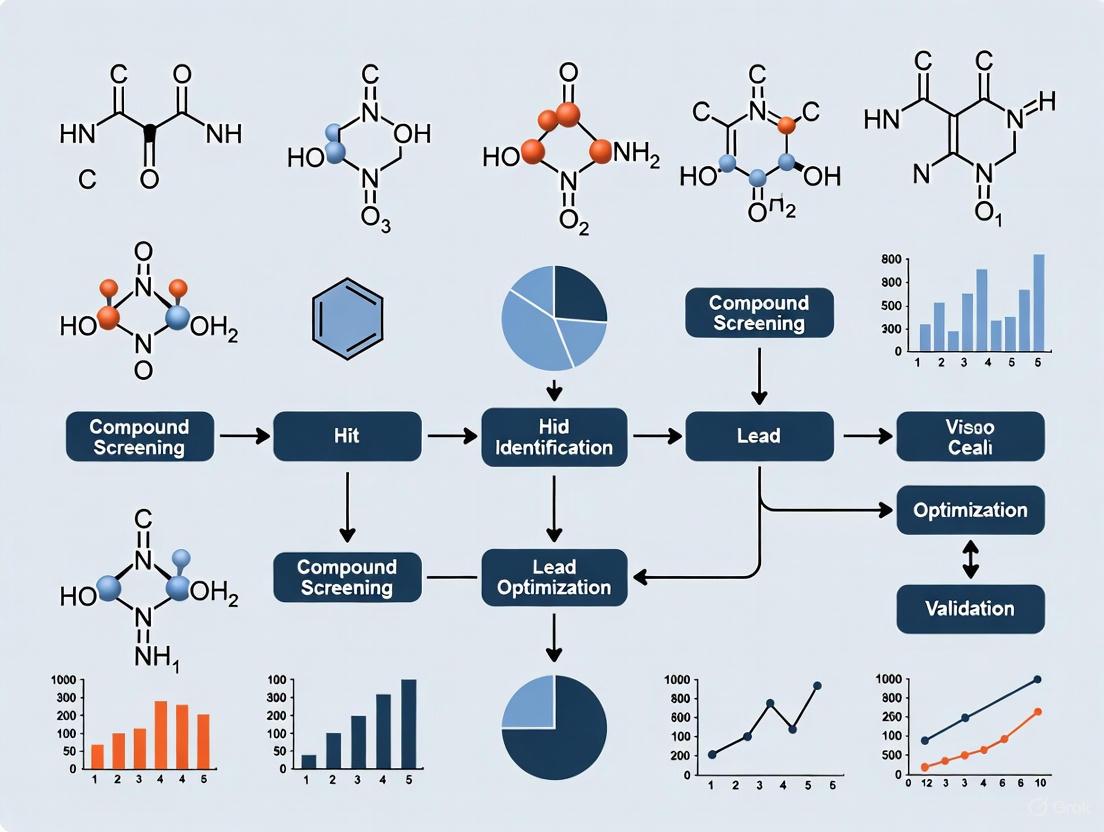

The following workflow diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of lead discovery, integrating both computational and experimental methodologies:

Lead Discovery Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The process of lead discovery and optimization relies on a sophisticated toolkit of reagents, databases, and instruments. The table below details key resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lead Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ChEMBL, ZINC [5] [6] | Provide extensive libraries of chemical compounds and their associated biological data for virtual screening and hypothesis generation. |

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [5] | Offer 3D structural information of biological macromolecules and small molecules critical for structure-based drug design. |

| Biophysical Assay Tools | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), NMR, Mass Spectrometry [5] [3] | Used for hit validation, studying binding affinity, kinetics, and characterizing molecular structures and interactions. |

| Specialized Screening Libraries | Fragment Libraries, HTS Compound Collections [7] [4] | Curated sets of molecules designed for specific screening methods like FBDD or phenotypic screening. |

The identification and characterization of a lead compound is a foundational and multifaceted stage in the drug discovery pipeline. A lead compound is defined not only by its confirmed biological activity against a therapeutic target but also by a suite of characteristics—including selectivity, druglikeness, and a favorable ADMET profile—that make it a suitable starting point for optimization. The modern researcher has access to a powerful and integrated arsenal of methodologies for lead discovery, ranging from high-throughput experimental screening to sophisticated computational approaches like virtual screening and data mining on chemical networks. The continued evolution of these technologies, especially in navigating ultra-large chemical spaces, holds the promise of delivering higher-quality lead candidates more efficiently, thereby accelerating the development of new therapeutic agents to address unmet medical needs.

The Critical Role of Lead Identification in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Lead identification represents a foundational and critical stage in the drug discovery pipeline, serving as the gateway between target validation and preclinical development. This comprehensive technical guide examines the methodologies, technologies, and strategic frameworks that define modern lead identification practices. We explore the evolution from traditional empirical screening to integrated computational approaches that leverage artificial intelligence, high-throughput automation, and multidimensional data analysis. The whitepaper details how these advanced paradigms have dramatically accelerated the initial phases of drug discovery while improving success rates through more informed candidate selection. Within the context of broader lead compound identification strategies research, we demonstrate how systematic lead identification establishes the essential chemical starting points that ultimately determine the viability of entire drug development programs. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review provides both theoretical foundations and practical frameworks for optimizing lead identification efforts across diverse therapeutic areas.

Lead identification constitutes the systematic process of identifying chemical compounds or molecules with promising biological activity against specific drug targets for downstream discovery processes [3]. These initial active compounds, known as "hits," are filtered based on critical physical properties including solubility, metabolic stability, purity, bioavailability, and aggregation potential [3]. The lead identification phase narrows the vast chemical space—estimated to contain approximately 10^60 potential compounds [8]—to a manageable number of promising candidates worthy of further optimization.

The identification of quality lead compounds marks a pivotal transition in the drug discovery pipeline, moving from theoretical target validation to tangible chemical entities with therapeutic potential. Lead compounds, whether natural or synthetic in origin, possess measurable biological activity against defined drug targets and provide the essential scaffold upon which drugs are built [3]. The quality of these initial leads fundamentally influences all subsequent development stages, with poor lead selection potentially dooming otherwise promising programs to failure after substantial resource investment.

Traditional drug discovery approaches relied heavily on empirical observations, serendipity, and labor-intensive manual screening of natural compounds [5]. These methods offered limited throughput and often failed to provide mechanistic insights into compound-target interactions. The introduction of genomics, molecular biology, and automated screening technologies in the late 20th century revolutionized the field, enabling more systematic and targeted approaches to lead discovery [5]. Today, lead identification sits at the intersection of multiple scientific disciplines, leveraging advances in computational chemistry, structural biology, and data science to navigate the complex landscape of chemical space with unprecedented efficiency.

Core Methodologies in Lead Identification

Experimental Screening Approaches

Traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) remains a widely-used lead discovery method that involves the rapid testing of large compound libraries against targets of interest [5]. Automated systems enable the screening of thousands to millions of compounds, significantly accelerating the identification of leads with potential therapeutic effects. Modern HTS systems can analyze up to 100,000 assays per day using ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) methods, detecting hits at micromolar or sub-micromolar levels for development into lead compounds [3]. Key advantages of HTS include enhanced automated operations, reduced human resource requirements, improved sensitivity and accuracy through novel assay methods, lower sample volumes, and significant cost savings in culture media and reagents [3].

Fragment-based screening offers a complementary approach that involves testing smaller, low molecular weight compounds (fragments) for their binding affinity to a target [5]. This method focuses on identifying key molecular fragments that can be subsequently optimized into more potent lead compounds. Although fragment-based screening requires detailed structural information and sophisticated analytical methods such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, it provides access to broader chemical space and often yields leads with improved binding affinities [5]. Fragment approaches are particularly valuable for challenging targets that may be difficult to address with traditional screening methods.

Affinity-based techniques represent a third major experimental approach, identifying lead compounds based on specific interactions with target molecules [5]. Techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and bio-layer interferometry (BLI) measure binding affinity, kinetics, and thermodynamics of molecular interactions. These methods provide invaluable insights into the strength and nature of binding, helping researchers prioritize candidates with optimal drug-like properties early in the discovery process [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Experimental Lead Identification Approaches

| Method | Throughput | Information Gained | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | High (10,000-100,000 compounds/day) | Biological activity | Broad coverage of chemical space; well-established infrastructure | High false-positive rates; limited mechanistic insight |

| Fragment-Based Screening | Medium (hundreds to thousands of fragments) | Binding sites and key interactions | Efficient exploration of chemical space; high-quality leads | Requires structural biology support; fragments may have weak affinity |

| Affinity-Based Techniques | Low to medium | Binding affinity, kinetics, thermodynamics | Detailed understanding of interactions; low false-positive rate | Lower throughput; requires specialized instrumentation |

Computational and AI-Driven Approaches

Computational methods have transformed lead identification by enabling efficient exploration of vast chemical spaces without the physical constraints of experimental screening. Molecular docking simulations serve as a foundational computational approach, predicting how small molecules interact with target binding sites [3]. These simulations prioritize compounds for experimental testing based on predicted binding affinities and interaction patterns, significantly reducing the number of compounds requiring physical screening.

Virtual screening extends this concept by computationally evaluating massive compound libraries against target structures. Modern AI-driven virtual screening platforms, such as the NVIDIA NIM-based pipeline developed by Innoplexus, can screen 5.8 million small molecules in just 5-8 hours, identifying the top 1% of compounds with high therapeutic potential [8]. These systems employ advanced neural networks for protein target prediction, trained on large-scale datasets of protein sequences, structural information, and molecular interactions [8].

Machine learning and deep learning approaches represent the cutting edge of computational lead identification. These methods systematically explore chemical space to identify potential drug candidates by analyzing large-scale data of known lead compounds [3]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have demonstrated particular promise, achieving up to 99% accuracy in benchmarking studies against specific targets like HER2 [9]. These models process molecular graphs to capture structural relationships and predict biological activity based on complex patterns in the data [9].

Network-based data mining approaches offer another innovative computational framework. These methods perform search operations on ensembles of chemical similarity networks, using multiple fingerprint-based similarity measures to prioritize drug candidates correlated with experimental activity scores such as IC50 [6]. This approach has demonstrated practical utility in case studies, successfully identifying and experimentally validating lead compounds for targets like CLK1 [6].

AI-Driven Lead Identification Workflow

Advanced Technologies and Research Reagents

Essential Research Tools and Platforms

Modern lead identification relies on sophisticated technological platforms and research reagents that enable precise manipulation and analysis of potential drug candidates. The following table details key solutions essential for contemporary lead identification workflows:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lead Identification

| Research Tool | Function in Lead Identification | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening Robotics | Automated testing of compound libraries | uHTS operations generating >100,000 data points daily; minimizes human resource requirements [3] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Molecular structure analysis and target interaction | Target druggability assessment, hit validation, pharmacophore identification [3] |

| Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Compound characterization and metabolite identification | Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics profiling; affinity selection of active compounds [3] [10] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding affinity and kinetics measurement | Determination of association/dissociation rates for target-compound interactions [5] |

| AlphaFold2 Protein Prediction | 3D protein structure determination from sequence | Accurate prediction of target protein structures for molecular docking [8] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Molecular property prediction from structural data | Analysis of molecular graphs to predict biological activity and binding affinity [9] |

| Knowledge Graphs (KGs) | Biological pathway mapping and target analysis | Organization and analysis of complex biological interactions; target prioritization [11] |

AI and Large Quantitative Models

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative force in lead identification, with Large Quantitative Models (LQMs) serving as comprehensive maps through the labyrinth of biological complexity [11]. These models integrate diverse data types—including genomic sequences, protein structures, literature findings, and clinical data—to provide holistic views of target interactions and enable efficient navigation of chemical space [11]. LQMs excel at identifying patterns and networks that would be difficult for researchers to discern using traditional methods alone.

Proteochemometric machine learning models represent a specialized AI approach designed to navigate complex experimental data sources [11]. Supported by automated data curation systems that ensure dataset validity, these models can be trained and evaluated for specific targets, providing researchers with predictive power to prioritize the most promising leads. When combined with physics-based computational chemistry models such as AQFEP (Advanced Quantum Free Energy Perturbation), these approaches offer unprecedented precision in evaluating molecule-target binding [11].

The real-world impact of these AI-driven approaches is demonstrated by their ability to identify novel targets for difficult-to-treat diseases, filter out false positives such as promiscuous binders, and recognize targets missed by traditional experimental screening methods [11]. These advancements not only accelerate the discovery process but significantly increase the likelihood of identifying viable treatment candidates.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AI-Driven Virtual Screening Protocol

The integration of AI in virtual screening has established new standards for throughput and efficiency in lead identification. The following protocol outlines a representative AI-driven screening workflow:

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Input target protein sequence into AlphaFold2 NIM microservice for 3D structure prediction [8]

- Generate multiple alignment configurations to improve structural accuracy

- Validate predicted structures against known homologous structures when available

Step 2: Compound Library Preparation

- Curate compound libraries from sources such as ZINC, PubChem, or proprietary collections

- Process molecular structures represented as SMILES strings into graph structures using RDKit library [9]

- Calculate molecular descriptors including molecular weight, topological polar surface area (TPSA), and octanol-water partition coefficient (MolLogP)

Step 3: AI-Based Compound Screening

- Implement Graph Neural Network (GNN) models with custom architecture including:

- Train models on known active and inactive compounds for the target family

- Screen 5.8M small molecules within 5-8 hours using NVIDIA H100 GPU clusters [8]

Step 4: Molecular Docking and Pose Prediction

- Process optimized molecules and target protein structure through DiffDock [8]

- Predict binding poses of molecules to the protein target

- Define number of poses and docking constraints for comprehensive analysis

Step 5: ADMET Profiling and Lead Selection

- Screen top 1,000 molecules through proprietary ADMET pipeline [8]

- Predict solubility, permeability, metabolism, and toxicity properties

- Filter and rank molecules based on predicted ADMET properties

- Select most promising candidates for experimental validation

Network Propagation-Based Lead Identification

For targets with limited known active compounds, network propagation approaches offer powerful alternative:

Step 1: Chemical Network Construction

- Compile 14 fingerprint-based similarity networks using diverse compound descriptors [6]

- Calculate compound similarities using Tanimoto similarity and Euclidean distance

- Build ensemble chemical similarity networks to minimize bias from individual similarity measures

Step 2: Initial Candidate Filtering

- Use deep learning-based drug-target interaction (DTI) model to narrow compound candidates [6]

- Address data gap issues through similarity-based associations between characterized and uncharacterized compounds

Step 3: Network Propagation Prioritization

- Implement network propagation algorithm to prioritize drug candidates highly correlated with drug activity scores (e.g., IC50) [6]

- Propagate information from known active compounds through the similarity networks

- Rank compounds based on propagation scores indicating likelihood of activity

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Select top candidates for synthesis and experimental testing

- Validate binding through biochemical assays such as binding assays or cellular activity tests

- In case study applications, this approach has successfully identified and validated 2 out of 5 synthesizable candidates for CLK1 target [6]

Network Propagation-Based Lead Identification

Current Market Landscape and Future Perspectives

Market Position and Growth Trajectory

The biologics drug discovery market, initially valued at $21.34 billion in 2024, is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.38%, reaching $63.07 billion by 2035 [12]. Within this expanding market, lead identification technologies play an increasingly crucial role. The hit generation/validation segment dominated the biologics drug discovery market by method, holding a 28.8% share in 2024 [12]. This segment encompasses critical lead identification activities such as phage display screening and hybridoma screening, which are pivotal in generating and validating high-affinity antibodies.

Geographic analysis reveals that the Asia-Pacific region is expected to witness the highest growth in biologics drug discovery, with a projected CAGR of 11.9% during the forecast period from 2025-2035 [12]. This growth is driven by increasing investment in biotechnology research, enhanced healthcare infrastructure, and growing emphasis on personalized medicine across countries such as China, Japan, India, and South Korea.

Table 3: Lead Identification Market Positioning and Technologies

| Market Segment | 2024 Valuation | Projected CAGR | Key Technologies | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hit Generation/Validation | 28.8% market share | Not specified | Phage display, hybridoma screening | Demand for precision medicine; complex disease targets [12] |

| Biologics Drug Discovery | $21.34 billion | 10.38% (2025-2035) | AI-driven platforms, high-throughput screening | Rising chronic disease prevalence; targeted therapy demand [12] |

| Asia-Pacific Market | Not specified | 11.9% (2025-2035) | CRISPR, gene editing, cell/gene therapies | Government investment; aging populations; healthcare infrastructure [12] |

Emerging Trends and Strategic Directions

The future of lead identification is being shaped by several converging technological trends. AI integration continues to advance beyond virtual screening to encompass target identification and validation, with Large Quantitative Models (LQMs) increasingly capable of navigating the complex maze of experimental data sources [11]. These models leverage automated data curation systems that ensure dataset validity, enabling more reliable predictions of target-compound interactions.

Automation and miniaturization represent another significant trend, with the development of homogeneous, fluorescence-based assays in miniaturized formats [3]. The introduction of high-density plates with 384 wells, automated dilution processes, and integrated liquid handling systems promise revolutionary improvements in screening efficiency and cost reduction.

Network-based approaches and chemical similarity exploration are gaining traction as effective strategies for addressing the data gap challenge—when only a small number of compounds are known to be active for a target protein [6]. These methods determine associations between compounds with known activities and large numbers of uncharacterized compounds, effectively expanding the utility of limited initial data.

The growing emphasis on academic-industry partnerships reflects the increasing complexity of lead identification technologies and the need for specialized expertise [3]. These collaborations are viewed as valuable mechanisms for addressing persistent challenges in drug discovery and ultimately delivering more effective therapies to patients.

Lead identification remains a critical determinant of success in the drug discovery pipeline, serving as the essential bridge between target validation and candidate optimization. The field has evolved dramatically from its origins in empirical observation and serendipity to become a sophisticated, technology-driven discipline that integrates computational modeling, high-throughput experimentation, and artificial intelligence. Modern lead identification strategies leverage diverse approaches—from fragment-based screening and affinity selection to AI-driven virtual screening and network propagation—to navigate the vastness of chemical space with increasing precision and efficiency.

The continuing transformation of lead identification is evidenced by several key developments: the achievement of 90% accuracy in lead optimization through AI-driven approaches [8], the ability to screen millions of compounds in hours rather than years [8], and the successful application of network-based methods to identify validated leads for challenging targets [6]. These advances collectively address the fundamental challenges of traditional drug discovery—high costs, lengthy timelines, and high attrition rates—while improving the quality of chemical starting points for optimization.

As the field progresses, the integration of increasingly sophisticated AI models, the expansion of chemical and biological databases, and the refinement of experimental screening technologies promise to further accelerate and enhance lead identification. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these evolving approaches is essential for maximizing the efficiency and success of therapeutic development programs. Through continued innovation and strategic implementation of these technologies, lead identification will maintain its critical role in bringing novel therapeutics to patients facing diverse medical challenges.

In the high-stakes landscape of drug discovery, the transition from a screening "hit" to a validated "lead" compound represents one of the most critical phases. A quality lead compound must embody three essential properties: efficacy against its intended therapeutic target, selectivity to minimize off-target effects, and optimal ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) characteristics to ensure adequate pharmacokinetics and safety [13] [14]. The pharmaceutical industry's high attrition rates, particularly due to unacceptable safety and toxicity accounting for over half of project failures, underscore the necessity of evaluating these properties early in the discovery process [13] [15]. The "fail early, fail cheap" strategy has consequently been widely adopted, with comprehensive lead profiling becoming indispensable for reducing late-stage failures [15]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these three pillars, offering detailed methodologies and contemporary approaches for identifying and optimizing lead compounds with the greatest potential for successful development.

Efficacy: Establishing Pharmacodynamic Activity

Defining and Measuring Target Engagement

Efficacy refers to a compound's ability to produce a desired biological response by engaging its specific molecular target. This encompasses binding affinity, functional activity (as an agonist or antagonist), and potency. Confirming target engagement and downstream pharmacological effects forms the foundation of lead qualification.

Key Experimental Protocols for Efficacy Assessment:

- In Vitro Binding Assays (e.g., SPR):

- Objective: To measure the direct binding affinity (KD) between the lead compound and its purified target protein.

- Detailed Protocol: The target protein is immobilized on a biosensor chip. Serial dilutions of the lead compound are flowed over the surface. The association and dissociation rates (ka and kd) are measured in real-time via surface plasmon resonance, and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated from these rates [15].

- Key Parameters: KD value, kinetic parameters (ka, kd), stoichiometry.

- Cell-Based Functional Assays:

- Objective: To determine the functional potency (IC50, EC50) of the lead compound in a cellular context.

- Detailed Protocol: Cells expressing the target of interest are treated with a concentration range of the lead compound. The functional output is measured, which may include reporter gene activity, second messenger levels (e.g., cAMP, Ca2+), or phosphorylation status. Data are normalized to controls and fitted to a sigmoidal curve to calculate the EC50/IC50 [16].

- Key Parameters: EC50, IC50, efficacy (% of control), Z'-factor for assay quality.

Table 1: Key In Vitro Experiments for Establishing Lead Compound Efficacy

| Property | Experimental Method | Key Readout | Target Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Binding | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | KD, ka, kd | KD < 100 nM (dependent on target class) |

| Functional Potency | Cell-based reporter assay, enzymatic assay | IC50, EC50 | IC50/EC50 < 100 nM |

| Mechanistic Action | Western blot, immunofluorescence, qPCR | Pathway modulation, target gene expression | Confirmation of hypothesized mechanism |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents for Efficacy Profiling

- Recombinant Target Proteins: Essential for biophysical binding assays (SPR, ITC) to determine direct binding affinity and kinetics without cellular complexity.

- Engineered Cell Lines: Stably or transiently transfected with the target gene of interest, often including a reporter system (e.g., luciferase, GFP) to quantify functional response in a physiologically relevant environment.

- Antibodies (Phospho-Specific & Total Protein): Used in techniques like Western Blot (Immunoblot) and ELISA to detect and quantify specific target proteins and their activation states (e.g., phosphorylation) downstream of compound treatment.

- Fluorescent Dyes & Probes (e.g., Ca2+ indicators, viability dyes): Enable real-time monitoring of cellular responses, ion flux, and cytotoxicity in high-throughput and high-content screening formats.

Selectivity: Minimizing Off-Target Effects

Assessing Selectivity Across the Proteome

Selectivity ensures that a lead compound's primary efficacy is not confounded by activity at off-target sites, which can lead to adverse effects. A selective compound interacts primarily with its intended target while showing minimal affinity for related targets, such as anti-targets and proteins in critical physiological pathways.

Key Experimental Protocols for Selectivity Assessment:

- Panel-Based Profiling (e.g., Kinase or GPCR Panels):

- Objective: To screen the lead compound against a broad panel of structurally or functionally related targets.

- Detailed Protocol: The lead compound is tested at a single concentration (e.g., 1 µM or 10 µM) against a predefined panel of 50-100 kinases, GPCRs, or ion channels in competitive binding or functional assays. The percentage of inhibition or binding for each off-target is calculated relative to controls.

- Key Parameters: % Inhibition at standard concentration; targets showing >50% inhibition are considered potential off-target hits.

- Cellular Phenotypic Profiling:

- Objective: To identify unexpected cellular effects or toxicity indicative of off-target activity.

- Detailed Protocol: Cells are treated with the lead compound and stained with multiplexed fluorescent dyes for various cellular components (nuclei, cytoskeleton, mitochondria). High-content imaging systems capture morphological features, and automated image analysis detects phenotypic changes that can be mapped to specific pathway perturbations [16].

- Key Parameters: Morphological profiling, cytotoxicity indices, mitochondrial health.

Table 2: Standard Selectivity Profiling Assays and Acceptability Criteria

| Selectivity Aspect | Profiling Method | Data Interpretation | Acceptability Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Target Activity | Primary assay on anti-target (e.g., hERG) | IC50 on anti-target vs. primary target | Selectivity index (IC50 anti-target / IC50 primary) > 30 |

| Panel Selectivity | Kinase/GPCR panel screening | Number of off-targets with >50% inhibition | <10% of panel members hit at 1 µM |

| Cytotoxicity | Cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo) | CC50 in relevant cell lines | Therapeutic index (CC50 / EC50) > 100 |

The following workflow outlines the strategic process for evaluating and optimizing lead compound selectivity.

ADMET: Optimizing Pharmacokinetics and Safety

Comprehensive ADMET Profiling

ADMET properties are crucial determinants of a lead compound's fate in the body and its potential to become a safe, efficacious drug. Early and systematic evaluation is essential to avoid costly late-stage failures due to poor pharmacokinetics or toxicity [13] [14] [17].

Key Experimental Protocols for Early ADMET Assessment:

- Caco-2 Permeability Assay:

- Objective: To predict human intestinal absorption and assess transporter effects.

- Detailed Protocol: Caco-2 cells are seeded on transwell filters and grown until they form a confluent, differentiated monolayer. The test compound is applied to the apical (A) or basolateral (B) side. Samples are taken from both compartments after a set incubation period, and compound concentration is quantified by LC-MS/MS. Apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio are calculated.

- Key Parameters: Papp (A→B) for absorption potential; Efflux Ratio (Papp (B→A)/Papp (A→B)); values >2 indicate active efflux.

- Metabolic Stability in Liver Microsomes:

- Objective: To determine the in vitro half-life and intrinsic clearance of a compound.

- Detailed Protocol: The lead compound is incubated with human liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH cofactor. Aliquots are taken at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min). The reaction is stopped, and the remaining parent compound is quantified by LC-MS/MS. The natural logarithm of the percent remaining is plotted versus time, and the slope is used to calculate the in vitro half-life (t1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint).

- Key Parameters: In vitro t1/2, Intrinsic Clearance (CLint).

- hERG Inhibition Patch-Clamp Assay:

- Objective: To assess the potential for cardiotoxicity via blockade of the hERG potassium channel.

- Detailed Protocol: Cells stably expressing the hERG channel are voltage-clamped. After establishing a stable current, the lead compound is applied in increasing concentrations. The inhibition of the tail current (IKr) is measured at each concentration, and an IC50 value is determined through non-linear regression fitting.

- Key Parameters: IC50 for hERG inhibition; a high IC50 (>10-30 µM, context-dependent) is desirable.

Table 3: Key ADMET Properties and Associated Experimental and In Silico Models

| ADMET Property | Standard In Vitro Assay | Common In Silico Endpoint | Target Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Caco-2 permeability, PAMPA | Caco-2 model, HIA model [17] | Papp (A-B) > 1x10-6 cm/s |

| Distribution | Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | LogD, VDss model [18] [19] | % Free > 1% |

| Metabolism | Microsomal/hepatocyte stability | CYP inhibition/substrate models [20] [17] | CLint < 15 µL/min/mg |

| Toxicity | hERG patch-clamp, Ames test | hERG, Ames, DILI models [18] [19] | hERG IC50 > 10 µM; Ames negative |

In Silico ADMET Prediction and the ADMET-Score

Computational approaches provide a high-throughput, cost-effective means for early ADMET screening, enabling the prioritization of compounds for synthesis and experimental testing [13] [15]. Two primary in silico categories are employed: molecular modeling (based on 3D protein structures, e.g., pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking) and data modeling (based on chemical structure, e.g., QSAR, machine learning) [13] [15]. The pharmaceutical industry now leverages numerous software platforms (e.g., ADMET Predictor, ADMETlab) capable of predicting over 175 ADMET endpoints [19] [17].

To integrate multiple predicted properties into a single, comprehensive metric, the ADMET-score was developed [20]. This scoring function evaluates chemical drug-likeness by integrating 18 critical ADMET endpoints—including Ames mutagenicity, Caco-2 permeability, CYP inhibition, hERG blockade, and human intestinal absorption—each weighted by model accuracy and the endpoint's pharmacokinetic importance [20]. This score has been validated to differ significantly between approved drugs, general chemical compounds, and withdrawn drugs, providing a valuable holistic view of a compound's ADMET profile [20].

The diagram below illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for ADMET risk assessment and mitigation in lead optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents for ADMET Profiling

- Caco-2 Cell Line: A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, expresses relevant transporters and forms a tight monolayer, making it a standard model for predicting intestinal permeability and efflux.

- Liver Microsomes / Hepatocytes: Subcellular fractions (microsomes) or primary cells (hepatocytes) from human and preclinical species, containing the full complement of CYP450 and other metabolic enzymes, used to assess metabolic stability and metabolite identification.

- hERG-Expressing Cell Lines: Engineered cell lines (e.g., HEK293 or CHO cells) that stably express the human ether-à-go-go-related gene potassium channel, which is critical for conducting patch-clamp electrophysiology studies to evaluate cardiotoxicity risk.

- S9 Fraction (for Ames Test): A post-mitochondrial supernatant fraction from rodent liver, containing necessary metabolic enzymes (activating system) used in the bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test) to assess the genotoxic potential of compounds.

The rigorous evaluation of efficacy, selectivity, and ADMET properties forms the cornerstone of successful lead identification and optimization. These three pillars are interdependent; a highly efficacious compound is of little therapeutic value if it lacks selectivity or possesses insurmountable ADMET deficiencies. The modern drug discovery paradigm necessitates the parallel, rather than sequential, assessment of these properties. This integrated approach, powered by both high-quality experimental data and sophisticated in silico predictions like the ADMET-score, allows research teams to identify critical flaws early and guide medicinal chemistry efforts more effectively [18] [20] [17]. By adhering to this comprehensive framework, drug discovery scientists can significantly de-risk the development pipeline, increasing the probability that their lead compounds will successfully navigate the arduous journey from the bench to the clinic.

Lead compound identification represents a critical foundation in the drug discovery pipeline, serving as the initial point for developing new therapeutic agents. A lead compound is defined as a chemical entity, whether natural or synthetic, that demonstrates promising biological activity against a therapeutically relevant target and provides a base structure for further optimization [21] [22]. This technical guide examines the three principal sources of lead compounds—natural products, synthetic libraries, and biologics—within the broader context of strategic lead identification. The selection of an appropriate source significantly influences subsequent development stages, impacting factors such as chemical diversity, target selectivity, and eventual clinical success rates. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the strategic advantages, limitations, and appropriate methodologies for leveraging each source is paramount for efficient drug discovery. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of these source categories, supported by experimental protocols, quantitative comparisons, and visualization of strategic workflows to guide research planning and execution.

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have constituted a rich and historically productive source of lead compounds for various therapeutic areas [23] [24]. These compounds, derived from plants, microbes, and animals, are characterized by their exceptional structural diversity, complex stereochemistry, and evolutionary optimization for biological interaction. It is estimated that approximately 35% of all current medicines originated from natural sources [21]. Major drug classes derived from natural leads include anti-infectives, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants. The therapeutic significance of natural product-derived drugs is exemplified by landmark compounds such as artemisinin (antimalarial), ivermectin (antiparasitic), morphine (analgesic), and the statins (lipid-lowering agents) [23] [22]. These compounds often serve as structural templates for extensive synthetic modification campaigns to enhance potency, improve pharmacokinetic properties, and reduce toxicity.

Advantages and Limitations

The primary advantage of natural products lies in their structural complexity and broad biological activity, which often translates into novel mechanisms of action and effectiveness against challenging targets [24]. However, several limitations complicate their development. The complexity of composition in crude natural extracts makes identifying active ingredients challenging and requires sophisticated isolation techniques [24]. Issues of sustainable supply can arise for compounds derived from rare or slow-growing organisms [23]. Furthermore, natural products may exhibit unfavorable physicochemical properties or present challenges in synthetic accessibility due to their complex molecular architectures [24]. These constraints necessitate careful evaluation of natural leads early in the discovery pipeline.

Table 1: Natural Product-Derived Drugs and Their Origins

| Natural Product Lead | Source Organism | Therapeutic Area | Optimized Drug Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | Papaver somniferum (Poppy) | Analgesic | Codeine, Hydromorphone, Oxycodone [22] |

| Teprotide | Bothrops jararaca (Viper Venom) | Antihypertensive | Captopril (ACE Inhibitor) [21] [22] |

| Lovastatin | Pleurotus ostreatus (Mushroom) | Lipid-lowering | Atorvastatin, Fluvastatin, Rosuvastatin [22] |

| Artemisinin | Artemisia annua (Sweet Wormwood) | Antimalarial | Artemether, Artesunate [23] [24] |

| Penicillin | Penicillium mold | Antibacterial | Multiple semi-synthetic penicillins, cephalosporins [24] |

Synthetic Compound Libraries

Design and Enumeration Strategies

Synthetic compound libraries represent a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, allowing for the systematic exploration of chemical space through designed collections of compounds. The design and enumeration of these libraries rely heavily on chemoinformatics approaches and reaction-based enumeration using accessible chemical reagents [25]. Key linear notations used in library enumeration include SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line System), SMARTS (SMILES Arbitrary Target Specification) for defining reaction rules, and InChI (International Chemical Identifier) for standardized representation [25]. Libraries can be designed using various strategies, including Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) to maximize structural variety, target-oriented synthesis for specific target classes, and focused libraries built around known privileged scaffolds or reaction schemes [26] [25]. The synthetic feasibility of designed compounds is a critical consideration, with tools like Reactor, DataWarrior, and KNIME enabling enumeration based on pre-validated chemical reactions [25].

Screening Approaches for Lead Identification

Synthetic libraries are primarily evaluated through high-throughput and virtual screening paradigms. High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated process that rapidly tests large compound libraries (hundreds of thousands to millions) for specific biological activity [22] [3]. HTS offers advantages in automated operations, reduced sample volumes, and increased throughput compared to traditional methods, though it requires significant infrastructure investment [3]. Virtual Screening (VS) complements HTS by computationally evaluating compound libraries against three-dimensional target structures [5] [2]. VS approaches include structure-based methods (molecular docking) and ligand-based methods (pharmacophore modeling, QSAR), enabling the prioritization of compounds for experimental testing [5] [2]. Fragment-based screening represents a specialized approach that identifies low molecular weight compounds (typically 150-300 Da) with weak but efficient binding, which are then optimized through fragment linking, evolution, or self-assembly strategies [21].

Table 2: Synthetic Library Design and Screening Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Characteristics | Typical Library Size | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Automated robotic systems, biochemical or cell-based assays, 384-1536 well plates [22] [3] | 500,000 - 1,000,000+ compounds [22] | Primary screening of diverse compound collections |

| Virtual Screening (VS) | Molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, machine learning approaches [5] [2] | Millions of virtual compounds [2] | Pre-screening to prioritize compounds, difficult targets |

| Fragment-Based Screening | Low molecular weight fragments (<300 Da), biophysical detection (NMR, SPR, X-ray) [21] | 500 - 5,000 fragments | Targets with well-defined binding pockets, novel chemical space |

| Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) | Build/Couple/Pair strategy, maximizes structural diversity [25] | Varies (typically 10^3 - 10^5) | Exploring novel chemical space, chemical biology |

Characteristics and Therapeutic Applications

Biologics represent a rapidly expanding category of therapeutic agents derived from biological sources, including proteins, antibodies, peptides, and nucleic acids. These compounds differ fundamentally from small molecules in their size, complexity, and mechanisms of action. The rise of biologics is reflected in drug approval statistics; in 2016, biologics (primarily monoclonal antibodies) accounted for 32% of total drug approvals, maintaining a significant presence in subsequent years [24]. Biologics offer several advantages as lead compounds, including high target specificity and potency, which can translate into reduced off-target effects. Approved biologic drugs include antibody-drug conjugates, enzymes, pegylated proteins, and recombinant therapeutic proteins [24]. Peptide-based therapeutics represent a particularly promising category, with over 40 cyclic peptide drugs clinically approved over recent decades, most derived from natural products [24].

Discovery and Engineering Approaches

The discovery of biologic lead compounds employs distinct methodologies compared to small molecules. Hybridoma technology remains foundational for monoclonal antibody discovery, while phage display and yeast display platforms enable the selection of high-affinity binding proteins from diverse libraries [24]. For peptide-based leads, combinatorial library approaches using biological systems permit the screening of vast sequence spaces. Engineering strategies focus on optimizing lead biologics through humanization of non-human antibodies to reduce immunogenicity, affinity maturation to enhance target binding, and Fc engineering to modulate effector functions and serum half-life [24]. Computational methods are increasingly integrated into biologic lead optimization, particularly for predicting immunogenicity, stability, and binding interfaces.

Experimental Protocols for Lead Identification

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Protocol

HTS represents a cornerstone experimental approach for identifying lead compounds from large synthetic or natural extract libraries. A standardized protocol for enzymatic HTS is detailed below:

Assay Development and Validation:

- Select a homogeneous assay format (e.g., fluorescence-based) compatible with automation and miniaturization [22].

- Optimize biochemical parameters including buffer composition, enzyme concentration, substrate KM determination, and linear reaction range.

- Validate assay robustness using statistical parameters (Z'-factor >0.5) and known controls [22].

Library Preparation:

- Prepare compound libraries in DMSO at standardized concentrations (typically 10 mM).

- Transfer compounds to assay plates (384- or 1536-well format) using automated liquid handlers, maintaining DMSO concentration below 1% [22].

Screening Execution:

- Dispense enzyme solution to assay plates.

- Pre-incubate compounds with enzyme for appropriate time (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Initiate reaction by adding substrate and monitor signal development over time.

- Include controls on each plate (no enzyme, no inhibitor, reference inhibitor) [22].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate percentage inhibition for each compound: % Inhibition = [1 - (Signalcompound - Signalno enzyme)/(Signalno inhibitor - Signalno enzyme)] × 100.

- Identify primary hits based on predetermined threshold (typically >50% inhibition at test concentration).

- Confirm hits through retesting in dose-response to determine IC50 values [22].

Fragment-Based Screening Protocol

Fragment-based screening identifies starting points with optimal ligand efficiency:

Library Design:

- Curate fragment library according to "Rule of Three" (MW <300, HBD ≤3, HBA ≤3, cLogP ≤3, rotatable bonds ≤3) [21].

- Ensure aqueous solubility >1 mM and chemical diversity.

Primary Screening:

- Screen fragments using biophysical methods such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or NMR.

- Identify binders showing dose-responsive binding, typically with affinity in high micromolar to millimolar range [21].

Hit Validation:

- Confirm binding using orthogonal techniques (e.g., ITC, X-ray crystallography).

- Determine binding mode and ligand efficiency (LE = ΔG/Nheavy atoms) [21].

Fragment Optimization:

- Employ strategies including fragment linking (joining two proximal fragments), fragment evolution (growing from initial fragment), or fragment self-assembly (designing complementary fragments that anneal in situ) [21].

- Iteratively optimize using structural information to maintain or improve ligand efficiency while increasing potency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lead Identification

| Reagent/Technology | Function in Lead Discovery | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures biomolecular interactions in real-time without labeling [21] | Fragment screening, binding kinetics (kon/koff), affinity measurements (KD) |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Provides atomic-level structural information on compound-target interactions [3] | Hit validation, pharmacophore identification, binding site mapping |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Characterizes drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics [3] | Metabolic stability assessment, metabolite identification, purity analysis |

| Assay-Ready Compound Plates | Pre-dispensed compound libraries in microtiter plates [22] | HTS automation, screening reproducibility, dose-response studies |

| 3D Protein Structures (PDB) | Atomic-resolution models of molecular targets [5] | Structure-based drug design, molecular docking, virtual screening |

| CHEMBL/PubChem Databases | Curated chemical and bioactivity databases [5] | Target profiling, lead prioritization, SAR analysis |

| Homogeneous Assay Reagents | "Mix-and-measure" detection systems (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) [22] | HTS implementation, miniaturized screening (384/1536-well) |

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Integration

Strategic selection of lead sources requires understanding their relative advantages and limitations. The following table provides a comparative analysis of key parameters:

Table 4: Strategic Comparison of Lead Compound Sources

| Parameter | Natural Products | Synthetic Libraries | Biologics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversity | High complexity, unique scaffolds [23] [24] | Broad but less complex, design-dependent [26] | Limited to proteinogenic building blocks |

| Success Rate (Historical) | High for anti-infectives, anticancer [23] [24] | Variable across target classes | High for specific targets (e.g., cytokines) |

| Development Timeline | Longer (isolation, characterization) [24] | Shorter (defined structures) | Medium to long (engineering, production) |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Often challenging (complex structures) [23] | High (deliberately designed) | Medium (biological production systems) |

| IP Position | May be constrained by prior art [23] | Strong with novel compositions | Strong with specific sequences/formulations |

| Therapeutic Area Strengths | Anti-infectives, Oncology, CNS [23] [24] | Broad applicability | Immunology, Oncology, Metabolic Diseases |

Integrated Lead Discovery Strategy

An effective lead discovery program often integrates multiple sources to leverage their complementary strengths. The following diagram illustrates a strategic workflow for lead identification that systematically incorporates natural, synthetic, and biologic approaches:

The strategic identification of lead compounds from natural, synthetic, and biologic sources remains fundamental to successful drug discovery. Each source offers distinct advantages: natural products provide unparalleled structural diversity and validated bioactivity; synthetic libraries enable systematic exploration of chemical space with defined properties; and biologics offer high specificity for challenging targets. Contemporary drug discovery increasingly leverages integrated approaches that combine the strengths of each source, guided by computational methods and high-throughput technologies. As drug discovery evolves, the continued strategic integration of these complementary approaches, enhanced by advances in computational prediction, library design, and screening methodologies, will be essential for addressing the challenges of novel target classes and overcoming resistance mechanisms. The optimal lead identification strategy ultimately depends on the specific target, therapeutic area, and resources available, requiring researchers to maintain expertise across all source categories to maximize success in bringing new therapeutics to patients.

The hit-to-lead (H2L) phase represents a critical gateway in the drug discovery pipeline, serving as the foundational process where initial screening hits are transformed into viable lead compounds with demonstrated therapeutic potential. This whitepaper examines the rigorous qualification criteria and experimental methodologies that govern this progression, framed within the broader context of lead compound identification strategies. We present a comprehensive analysis of the multi-parameter optimization framework required to advance compounds through this crucial stage, including detailed experimental protocols, quantitative structure-activity relationship (SAR) establishment, and the integration of computational approaches that enhance the efficiency of lead identification. For research teams navigating the complexities of early drug discovery, mastering the hit-to-lead transition is essential for reducing attrition rates and building a robust pipeline of clinical candidates.

The hit-to-lead stage is defined as the phase in early drug discovery where small molecule hits from initial screening campaigns undergo evaluation and limited optimization to identify promising lead compounds [27]. This process serves as the critical bridge between initial target identification and the more extensive optimization required for clinical candidate selection. The overall drug discovery pipeline follows a defined path: Target Validation → Assay Development → High-Throughput Screening (HTS) → Hit to Lead (H2L) → Lead Optimization (LO) → Preclinical Development → Clinical Development [27].

Within this continuum, the H2L phase specifically focuses on confirming and evaluating initial screening hits, followed by synthesis of analogs through a process known as hit expansion [27]. Typically, initial screening hits display binding affinities for their biological targets in the micromolar range (10−6 M), and through systematic H2L optimization, these affinities are often improved by several orders of magnitude to the nanomolar range (10−9 M) [27]. The process also aims to improve metabolic half-life so compounds can be tested in animal models of disease, while simultaneously enhancing selectivity against other biological targets whose binding may result in undesirable side effects [27].

Defining Hits and Leads: Fundamental Concepts

What Constitutes a "Hit"?

In drug discovery terminology, a hit is a compound that displays desired biological activity toward a drug target and reproduces this activity when retested [28]. Hits are identified through various methods including High-Throughput Screening (HTS), virtual screening (VS), or fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) [28]. The key characteristics of a qualified hit include:

- Reproducible activity in confirmatory testing

- Demonstrable binding to the intended target

- Reasonable potency (typically micromolar range)

- Chemical structure that allows for further modification

The Transition to "Lead" Compound

A lead compound is defined as a chemical entity within a defined chemical series that has demonstrated robust pharmacological and biological activity on a specific therapeutic target [28]. More specifically, a lead compound is "a new chemical entity that could potentially be developed into a new drug by optimizing its beneficial effects to treat diseases and minimize side effects" [29]. These compounds serve as starting points in drug design, from which new drug entities are developed through optimization of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties [29].

The progression from hit to lead involves significant improvement in multiple parameters. While hits may have initial activity, leads must demonstrate:

- Higher affinity for the target (often <1 μM)

- Improved selectivity versus other targets

- Significant efficacy in cellular assays

- Demonstrated drug-like properties

- Acceptable early ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) properties [28]

The Hit-to-Lead Process: Methodologies and Workflows

Hit Confirmation Protocols

The hit-to-lead process begins with rigorous confirmation and evaluation of initial screening hits through multiple experimental approaches:

Confirmatory Testing: Compounds identified as active against the selected target are re-tested using the same assay conditions employed during the initial screening to verify that activity is reproducible [27].

Dose Response Curve Establishment: Confirmed hits are tested over a range of concentrations to determine the concentration that results in half-maximal binding or activity (represented as IC50 or EC50 values) [27].

Orthogonal Testing: Confirmed hits are assayed using different methods that are typically closer to the target physiological condition or utilize alternative technologies to validate initial findings [27].

Secondary Screening: Confirmed hits are evaluated in functional cellular assays to determine efficacy in more biologically relevant systems [27].

Biophysical Testing: Techniques including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), dynamic light scattering (DLS), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), dual polarisation interferometry (DPI), and microscale thermophoresis (MST) assess whether compounds bind effectively to the target, along with binding kinetics, thermodynamics, and stoichiometry [27].

Hit Ranking and Clustering: Confirmed hit compounds are ranked according to various experimental results and clustered based on structural and functional characteristics [27].

Freedom to Operate Evaluation: Hit structures are examined in specialized databases to determine patentability and intellectual property considerations [27].

Hit Expansion and SAR Development

Following hit confirmation, several compound clusters are selected based on their characteristics in the previously defined tests. The ideal compound cluster contains members possessing the following properties [27]:

- High affinity toward the target (typically less than 1 μM)

- Selectivity versus other targets

- Significant efficacy in cellular assays

- Drug-like characteristics (moderate molecular weight and lipophilicity as estimated by ClogP)

- Low to moderate binding to human serum albumin

- Low interference with P450 enzymes and P-glycoproteins

- Low cytotoxicity

- Metabolic stability

- High cell membrane permeability

- Sufficient water solubility (above 10 μM)

- Chemical stability

- Synthetic tractability

- Patentability

Project teams typically select between three and six compound series for further exploration. The subsequent step involves testing analogous compounds to determine quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR). Analogs can be rapidly selected from internal libraries or purchased from commercially available sources in an approach often termed "SAR by catalog" or "SAR by purchase" [27]. Medicinal chemists simultaneously initiate synthesis of related compounds using various methods including combinatorial chemistry, high-throughput chemistry, or classical organic synthesis approaches [27].

The DMTA Cycle: Core Engine of Hit-to-Lead Optimization

The hit-to-lead process operates through iterative Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycles [28]. This systematic approach drives continuous improvement of compound properties:

Design: Based on emerging SAR data and structural information, medicinal chemists design new analogs with predicted improvements in potency, selectivity, or other properties.

Make: The designed compounds are synthesized through appropriate chemical methods, with consideration for scalability and synthetic feasibility.

Test: Newly synthesized compounds undergo comprehensive biological testing to assess potency, selectivity, ADME properties, and初步毒性.

Analyze: Results are analyzed to identify structural trends and inform the next cycle of compound design.

This iterative process continues until compounds meet the predefined lead criteria, typically requiring multiple cycles to achieve sufficient optimization.

Diagram: Hit-to-Lead Workflow with DMTA Cycles. This workflow illustrates the iterative DMTA (Design-Make-Test-Analyze) process that drives hit-to-lead optimization.

Key Qualification Criteria and Experimental Design

Quantitative Progression Metrics

The transition from hit to lead requires compounds to meet specific quantitative benchmarks across multiple parameters. The following table summarizes the key criteria for lead qualification:

Table: Hit versus Lead Qualification Criteria

| Parameter | Hit Compound | Lead Compound | Measurement Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | Typically micromolar range (µM) | Nanomolar range (nM), <1 µM | IC₅₀, EC₅₀, Kᵢ determinations [27] |

| Selectivity | Preliminary assessment | Significant selectivity versus related targets | Counter-screening against target family members [27] |

| Cellular Activity | May show limited cellular activity | Demonstrated efficacy in cellular models | Cell-based assays, functional activity measurements [27] |

| Solubility | >10 µM acceptable | >10 µM required | Kinetic and thermodynamic solubility measurements [27] |

| Metabolic Stability | Preliminary assessment | Moderate to high stability in liver microsomes | Microsomal stability assays, hepatocyte incubations [28] |

| Cytotoxicity | Minimal signs of toxicity | Low cytotoxicity at therapeutic concentrations | Cell viability assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo) [27] |

| Permeability | Preliminary assessment | High cell membrane permeability | Caco-2, PAMPA assays [27] |

| Chemical Stability | Acceptable for initial testing | Demonstrated stability under various conditions | Forced degradation studies [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Lead Qualification

Biochemical Assay Protocol for Potency Assessment

Purpose: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of compounds against the target protein.

Materials:

- Purified target protein

- Test compounds dissolved in DMSO

- Substrate/ligand for the target

- Detection reagents (fluorogenic or chromogenic)

- 384-well assay plates

- Plate reader capable of absorbance/fluorescence detection

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of test compounds in assay buffer, typically spanning a 10,000-fold concentration range.

- Add target protein to wells followed by compound solutions.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature to allow compound binding.

- Initiate reaction by adding substrate at Km concentration.

- Monitor reaction progress for 30-60 minutes.

- Calculate percentage inhibition relative to controls (DMSO-only for 0% inhibition, reference inhibitor for 100% inhibition).

- Fit concentration-response data to four-parameter logistic equation to determine IC₅₀ values.

Data Analysis: Compounds with IC₅₀ < 1 µM typically progress to secondary assays. Ligand efficiency (LE) is calculated as LE = (1.37 × pIC₅₀)/number of heavy atoms to identify compounds with efficient binding [27].

Metabolic Stability Assay Protocol

Purpose: To evaluate the metabolic stability of lead candidates in liver microsomes.

Materials:

- Pooled species-specific liver microsomes

- NADPH regenerating system

- Test compounds (10 µM final concentration)

- Acetonitrile for protein precipitation

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Procedure:

- Pre-incubate liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) with test compounds in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Initiate reaction by adding NADPH regenerating system.

- Remove aliquots at 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes.

- Terminate reaction by adding ice-cold acetonitrile containing internal standard.

- Centrifuge to precipitate proteins and analyze supernatant by LC-MS/MS.

- Monitor parent compound disappearance over time.

Data Analysis: Calculate half-life (t₁/₂) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) using the formula: CLint = (0.693/t₁/₂) × (microsomal incubation volume/microsomal protein). Compounds with low clearance (CLint < 50% of liver blood flow) are preferred [3].

Computational and Advanced Approaches in Lead Identification

Emerging Computational Methods

Modern lead identification increasingly leverages computational approaches to enhance efficiency and success rates:

Machine Learning and Deep Learning: ML and DL approaches systematically explore chemical space to identify potential drug candidates by analyzing large-scale data of lead compounds [3] [6]. These methods offer accurate prediction of lead compound generation and can identify new chemical scaffolds.

Network Propagation-Based Data Mining: Recent approaches use network propagation on chemical similarity networks to prioritize drug candidates that are highly correlated with drug activity scores such as IC₅₀ [6]. This method performs searches on an ensemble of chemical similarity networks to identify unknown compounds with potential activity.

Chemical Similarity Networks: These networks utilize various similarity measures including Tanimoto similarity and Euclidean distance to compare and rank compounds based on structural and chemical properties [6]. By constructing multiple fingerprint-based similarity networks, researchers can comprehensively explore chemical space.

Virtual Screening: Computational techniques such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations predict which compounds within large libraries are likely to bind to a target protein [3] [28]. This approach significantly narrows the candidate pool for experimental testing.

High-Throughput Screening Methodologies

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) remains a cornerstone technology for hit identification, with modern implementations offering significant advantages:

Automated Operations: HTS employs automated robotic systems to analyze thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds rapidly [3].

Reduced Resource Requirements: Modern HTS requires minimal human intervention while providing improved sensitivity and accuracy through novel assay methods [3].

Miniaturized Formats: Current systems utilize lower sample volumes, resulting in significant cost savings for culture media and reagents [3].

Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (UHTS): Advanced systems can conduct up to 100,000 assays per day, detecting hits at micromolar or sub-micromolar levels for development into lead compounds [3].

Diagram: Lead Identification Strategies. Multiple computational and experimental approaches contribute to modern lead identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Hit-to-Lead Studies

| Tool/Technology | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions | Provides kinetic parameters (kₒₙ, kₒff), affinity measurements, and binding stoichiometry [27] [28] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Structural analysis of compounds and target engagement | Determines binding sites, structural changes, and ligand orientation; used in FBDD [3] [28] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Quantification of binding thermodynamics | Measures binding affinity, enthalpy change (ΔH), and stoichiometry without labeling [27] [28] |

| High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry | Compound characterization and metabolic profiling | Identifies metabolic soft spots, characterizes DMPK properties; used in LC-MS systems [3] |

| Cellular Assay Systems | Functional assessment in biologically relevant contexts | Measures efficacy, cytotoxicity, and permeability in cell-based models [27] |

| Molecular Docking Software | In silico prediction of protein-ligand interactions | Prioritizes compounds for synthesis through virtual screening [3] [6] |

| Chemical Similarity Networks | Data mining of chemical space for lead identification | Uses network propagation to identify compounds with structural similarity to known actives [6] |

The hit-to-lead process represents a methodologically rigorous stage in drug discovery that demands integrated application of multidisciplinary approaches. Successful navigation of this phase requires systematic evaluation of compounds against defined criteria encompassing potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties through iterative DMTA cycles. The continuing integration of computational methods, including machine learning and network-based approaches, with experimental validation provides an powerful framework for enhancing the efficiency of lead identification. By adhering to structured qualification criteria and employing the appropriate experimental and computational tools detailed in this whitepaper, research teams can significantly improve their probability of advancing high-quality lead compounds into subsequent development stages, ultimately increasing the likelihood of clinical success.

Methodologies in Action: A Guide to Modern Lead Identification Techniques

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated methodology that enables the rapid execution of millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests, fundamentally transforming the landscape of drug discovery and basic biological research [30]. By leveraging robotics, sophisticated data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors, HTS allows researchers to efficiently identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways [30] [31]. This paradigm shift from traditional one-at-a-time experimentation to massive parallel testing provides the foundational technology for modern lead compound identification strategies, serving as the critical initial step in the drug discovery pipeline where promising candidates are selected from vast compound libraries for further development.