Isotropic vs Anisotropic Lipophilicity: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a thorough comparison of isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity, two critical concepts in medicinal chemistry and drug design.

Isotropic vs Anisotropic Lipophilicity: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparison of isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity, two critical concepts in medicinal chemistry and drug design. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles defining each system, detailing standard and high-throughput methodologies for their measurement. The content addresses common challenges in lipophilicity determination and offers optimization strategies, supported by a validation framework that compares predictive power for key pharmacokinetic behaviors. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application, this guide aims to enhance drug candidate selection and optimize physicochemical property profiling.

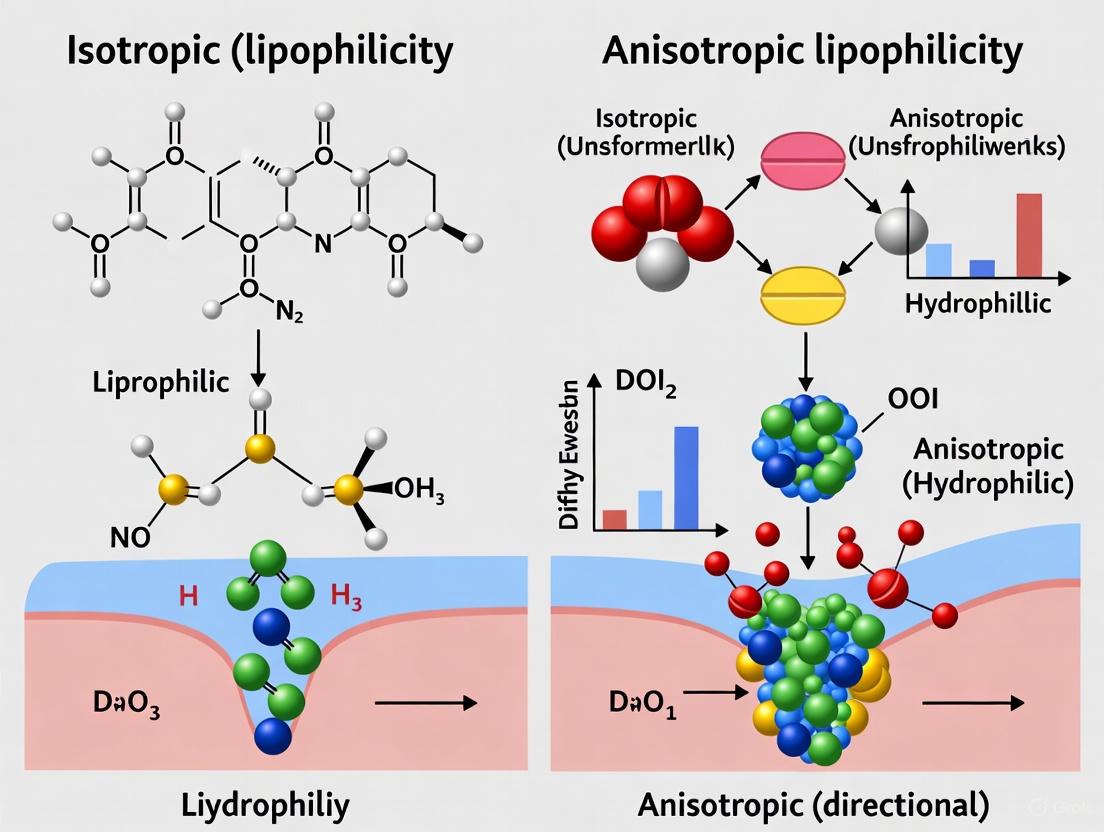

Defining the Lipophilicity Landscape: From Isotropic Solvents to Anisotropic Biomimetic Systems

Lipophilicity, a fundamental physicochemical property, is defined as the affinity of a molecule for a lipophilic environment relative to an aqueous one [1]. It is a critical parameter in drug discovery and development, influencing a compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile [1] [2]. Traditionally, lipophilicity has been assessed through an isotropic model, which assumes a uniform, homogenous partitioning environment. However, the recognition that biological membranes are highly organized and structurally complex has led to the emergence of anisotropic lipophilicity models, which account for directionally dependent, heterogeneous interactions [1] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two paradigms, detailing their core definitions, experimental determination methods, and relevance for modern pharmaceutical research.

Core Concepts and Fundamental Differences

The distinction between isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity lies in the nature of the partitioning environment and the intermolecular forces involved.

Isotropic Lipophilicity describes the partitioning of a solute between two isotropic, or uniform, bulk phases—typically n-octanol (nonpolar) and water (polar) [1]. The resulting partition coefficient (log P) represents the net sum of a molecule's hydrophobicity minus its polarity. It is a direction-independent property, where the measured value is identical regardless of orientation, much like the physical properties of glass or cubic crystals [4] [5] [6]. This model provides a single, averaged measure of lipophilicity.

Anisotropic Lipophilicity, in contrast, describes partitioning into anisotropic, non-uniform phases such as artificial membranes, liposomes, or micelles [1]. These environments possess distinct topological regions and can form different types of interactions with a solute. Unlike the isotropic model, anisotropic lipophilicity encodes not only hydrophobicity and polarity but also considers directional interactions like ionic bonds and specific π–π interactions [1]. The property is direction-dependent, akin to the varying strength of wood along versus across its grain [4] [5].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these two concepts.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity.

| Characteristic | Isotropic Lipophilicity | Anisotropic Lipophilicity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Partitioning into uniform, bulk phases [1] | Partitioning into ordered, non-uniform phases [1] |

| Direction Dependence | Direction-independent [4] | Direction-dependent [4] |

| Representative System | n-Octanol/Water [1] [7] | Liposomes/Buffer; Chromatographic Systems [1] |

| Intermolecular Forces Encoded | Hydrophobicity, Polarity [1] | Hydrophobicity, Polarity, Ionic bonds, Specific interactions (e.g., π–π) [1] |

| Primary Measured Output | log P (for unionized species) or log D (at a specific pH) [1] [8] | Chromatographic retention parameters (e.g., log k, Rₘ) [9] [1] [2] |

| Physiological Relevance | Simpler model; a good initial approximation | Higher; better mimics complex biological barriers like cell membranes [1] [3] |

Experimental Determination: Methods and Protocols

The philosophical difference between isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity is reflected in the experimental techniques used for their determination.

Determining Isotropic Lipophilicity

The "gold standard" for isotropic lipophilicity is the shake-flask method [1] [7]. This direct method involves partitioning the solute between n-octanol and water (or a buffer) phases.

- Detailed Protocol: Shake-Flask Method

- Preparation: Pre-saturate n-octanol and water with each other to prevent phase changes during the experiment.

- Partitioning: Dissolve a known amount of the test compound in either the aqueous or organic phase. Combine the two phases in a flask, typically at a 1:1 ratio.

- Equilibration: Shake the mixture vigorously for a predetermined period (which can range from 1 hour to 24 hours) to allow the solute to distribute between the phases [7].

- Separation: After shaking, allow the phases to separate completely. Centrifugation may be used to aid separation.

- Quantification: Carefully sample each phase and quantify the solute concentration in both using a suitable analytical method, most often Liquid Chromatography (LC) due to its wide applicability and low detection limit [1] [7].

- Calculation: The partition coefficient, log P, is calculated as the logarithm (base 10) of the ratio of the solute's concentration in the n-octanol phase to its concentration in the aqueous phase.

While accurate, the shake-flask method is labor-intensive, consumes significant amounts of solvent and compound, and is not well-suited for compounds with very high or low log P values [1] [7]. Several modifications have been developed to address these limitations, such as the slow-stirring method to prevent emulsions and the vortex-assisted liquid–liquid microextraction (VALLME) to drastically reduce equilibration time and solvent volumes [7].

Determining Anisotropic Lipophilicity

Chromatographic techniques are the primary tool for assessing anisotropic lipophilicity. These are indirect methods where the retention behavior of a compound on a chromatographic system correlates with its lipophilicity.

- Detailed Protocol: Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RP-LC)

- System Setup: A reversed-phase chromatographic system is used, typically with a non-polar stationary phase (e.g., C18-silanized silica) and a polar mobile phase (e.g., mixtures of methanol or acetonitrile with water or buffer) [9] [2] [8].

- Column Selection: The choice of stationary phase is crucial. While octadecyl (C18) columns are common, phenyl columns are particularly interesting for anisotropic studies as they can engage in specific π–π interactions with analytes, mimicking specific biological interactions [9].

- Analysis: The test compound is injected into the mobile phase stream. As it passes through the column, it partitions between the mobile phase and the stationary phase.

- Data Collection: The retention time (tᵣ) of the compound is recorded. The retention time of an unretained marker (t₀) is also determined.

- Calculation: The capacity factor (k) is calculated as 𝑘 = (tᵣ − t₀)/t₀ [9]. This log k value, often determined at several mobile phase compositions, serves as a chromatographic descriptor of anisotropic lipophilicity. The specific interactions with the stationary phase (e.g., hydrophobic, π–π, hydrogen-bonding) make this a direction-dependent, anisotropic measure.

This approach is high-throughput, requires minimal amounts of compound, and can tolerate impurities [2] [8]. The retention data can be analyzed using chemometric tools like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reveal similarities and dissimilarities between compounds and chromatographic systems [9].

Graphviz diagram illustrating the core workflow for determining lipophilicity, highlighting the parallel paths for isotropic and anisotropic methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental determination of lipophilicity relies on key reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for both isotropic and anisotropic methods.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for lipophilicity studies.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Common Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol | The standard nonpolar phase in isotropic (shake-flask) partition systems [1] [7]. | HPLC or ACS grade, pre-saturated with water or buffer. |

| Aqueous Buffer | The polar phase in partition systems; controls pH for log D measurements [1]. | Phosphate buffer (e.g., pH 7.4); water (HPLC grade). |

| Reversed-Phase LC Columns | The stationary phase for anisotropic lipophilicity measurement; mimics a structured environment [9] [8]. | C18 (Octadecyl), C8 (Octyl), Phenyl columns. |

| Organic Modifiers | Component of the mobile phase in RP-LC; controls elution strength and selectivity [9] [2]. | Methanol (protic), Acetonitrile (aprotic); HPLC grade. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Immobilized on stationary phases to study drug-plasma protein binding via High Performance Affinity Chromatography (HPAC), an anisotropic parameter [2]. | Commercial HSA-based HPLC columns. |

| Liposomes | Anisotropic vesicles used as a non-aqueous phase to better model biological membrane partitioning [1]. | Prepared from phospholipids like phosphatidylcholine. |

Isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity represent complementary paradigms in physicochemical profiling. The isotropic model, exemplified by the n-octanol/water shake-flask method, provides a simple, standardized, and invaluable measure of a compound's general lipophilicity (log P). In contrast, anisotropic lipophilicity, determined primarily via chromatographic techniques, offers a more nuanced and physiologically relevant perspective by accounting for the directional and specific interactions a compound may encounter with complex biological structures like cell membranes and proteins. For researchers in drug development, a strategic combination of both approaches is ideal: using isotropic log P for initial screening and compound design, and leveraging anisotropic data to refine predictions of in vivo behavior, particularly for understanding permeability, distribution, and protein binding, thereby de-risking the candidate selection process.

In medicinal chemistry and drug design, the behavior of a molecule in a biological system is profoundly influenced by a trio of fundamental molecular forces: hydrophobicity, polarity, and ionic bonds. These forces collectively govern how substances interact with aqueous environments, cross biological barriers, and bind to their targets. Hydrophobicity describes the tendency of nonpolar molecules or molecular regions to associate in an aqueous environment, a phenomenon famously characterized by the clathrate "cage" structure water molecules form around hydrophobes [10] [11]. Polarity arises from the unequal sharing of electrons in covalent bonds between atoms of different electronegativities, creating molecular dipoles that can interact favorably with water molecules [12] [13]. Ionic bonds represent the electrostatic attraction between fully charged, oppositely charged species, such as those found in salts and many biological macromolecules [12].

The interplay of these forces is encapsulated in the concept of lipophilicity, a key physicochemical property that can be assessed through two distinct lenses: isotropic and anisotropic systems. Isotropic lipophilicity, typically measured in a homogeneous solvent system like n-octanol/water, reflects the compound's partition coefficient (log P) resulting from the net sum of hydrophobicity minus polarity [1]. In contrast, anisotropic lipophilicity is determined using structurally ordered systems such as chromatographic stationary phases or artificial membranes, where ionic charges have fixed locations and the resulting distribution coefficient encodes not only hydrophobicity and polarity but also ionic interactions [1] [14]. This comparison guide objectively examines the experimental approaches, data, and implications of research in both isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity, providing scientists with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies in drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The Hydrophobic Effect and Its Thermodynamic Basis

The hydrophobic effect is primarily an entropically driven phenomenon. When a hydrophobe is introduced into water, hydrogen bonds between water molecules break to accommodate the solute. The surrounding water molecules reorganize to form a more ordered, ice-like "clathrate cage" structure around the hydrophobe, resulting in a decrease in system entropy (ΔS < 0) [10]. The enthalpy change (ΔH) during this process can be negative, zero, or positive, but it is the large negative entropy change that makes the overall Gibbs free energy change (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS) positive, rendering the mixing of hydrophobes and water non-spontaneous [10]. However, when hydrophobic molecules come together, the structured water molecules are released back into the bulk, increasing entropy and making hydrophobic interactions spontaneous with a negative ΔG [10] [11].

Polarity and Dipolar Interactions

Polarity stems from the unequal sharing of electrons in covalent bonds between atoms with different electronegativities. In water molecules, oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, resulting in a partial negative charge (δ-) on the oxygen and partial positive charges (δ+) on the hydrogens [12] [13]. This creates a molecular dipole. Polar molecules interact through dipole-dipole interactions, where the partially positive end of one molecule attracts the partially negative end of another [12]. These interactions are stronger than London dispersion forces but weaker than hydrogen bonds or ionic bonds. The polarity of a molecule significantly influences its solubility, with polar compounds generally dissolving readily in polar solvents like water.

Ionic Bonds and Ion-Dipole Forces

Ionic bonds represent the strongest type of intermolecular force covered here, formed by the complete transfer of electrons from one atom to another, resulting in positively and negatively charged ions that electrostatically attract each other [12]. In aqueous solutions, ionic compounds interact with water molecules through ion-dipole interactions, where the charged ions are surrounded by the oppositely charged ends of water molecules, facilitating dissolution through a process called hydration [13]. These interactions are crucial for the solubility of salts and for the behavior of charged molecules in biological systems.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Molecular Forces

| Force Type | Origin | Relative Strength | Role in Lipophilicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Entropic drive from water reorganization | Relatively stronger than other weak intermolecular forces [10] | Increases lipophilicity; promotes association of nonpolar groups |

| Polarity / Dipole-Dipole | Unequal electron sharing in covalent bonds | Moderate [12] | Decreases lipophilicity; enhances aqueous solubility |

| Ionic Bonds / Ion-Dipole | Electrostatic attraction between full charges | Strong [12] | Significantly decreases lipophilicity; dominant in anisotropic systems |

Methodological Comparison: Isotropic vs. Anisotropic Lipophilicity Assessment

Isotropic Lipophilicity Determination

The gold standard for experimental determination of isotropic lipophilicity is the shake-flask method, which uses n-octanol and water as the biphasic system [1] [7]. This method, recommended by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), involves dissolving the sample in the system, shaking until equilibrium is reached, and measuring the compound concentration in each phase [7]. The partition coefficient, P, is calculated as the ratio of the equilibrium concentration in n-octanol to that in water, and lipophilicity is expressed as log P [1].

While direct, this method has limitations: it is time-consuming (1-24 hours to reach equilibrium), requires relatively large amounts of pure compounds, and is not suitable for compounds with log P > 4 due to detection limit issues in the aqueous phase [1] [7]. Several modifications have been developed to address these drawbacks:

- Slow-Stirring Method: Prevents emulsion formation by slow stirring instead of shaking, requiring 2-3 days to reach equilibrium but providing more accurate values for highly lipophilic compounds (log P > 4.5) [7].

- Vortex Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (VALLME): Uses vortex agitation to disperse n-octanol into microdroplets in the aqueous phase, dramatically increasing the interfacial contact area and reducing equilibrium time to just 2 minutes [7].

- Flow-Based Methods: Utilize flow injection analysis to standardize measurements, with the large surface area enabling rapid equilibrium attainment [7].

Anisotropic Lipophilicity Determination

Chromatographic methods are primarily used for determining anisotropic lipophilicity, where the stationary phase mimics the ordered environment of biological membranes [1] [14]. Both High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) are employed, with the latter offering advantages of reduced cost, time, and solvent consumption while allowing multiple samples to be handled simultaneously [14].

In these systems, the retention factor correlates with the compound's distribution behavior between the mobile phase and the stationary phase. The spatial distribution of ionic charges in the non-aqueous phase represents the key difference from isotropic systems - in anisotropic media, ionic charges have fixed locations on the chromatography plates or columns, more closely resembling the fixed charge distribution in phospholipid membranes [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Methods for Lipophilicity Determination

| Method | System Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask | Isotropic | Partition between n-octanol and water | Gold standard, direct measurement [7] | Time-consuming, not for log P > 4, emulsion issues [1] [7] |

| Slow-Stirring | Isotropic | Prevents emulsions by slow stirring | Accurate for high log P [7] | Very long equilibrium time (2-3 days) [7] |

| VALLME | Isotropic | Vortex creates microdroplets for fast equilibrium | Rapid (2 min), high throughput [7] | Requires centrifugation for phase separation [7] |

| RP-HPTLC/HPLC | Anisotropic | Retention on structured stationary phase | Mimics biomembranes, high throughput [14] | No standardized system, correlation-dependent [14] |

Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparison in Model Systems

Research on anisotropic and isotropic gelatin hydrogels provides compelling experimental data on how structural differences affect molecular permeability based on lipophilicity. In a study investigating permeability with model molecules of different log P values, anisotropic networks formed with polypropylene (PP) templates demonstrated preferential permeability for hydrophobic molecules, while isotropic networks favored hydrophilic compounds [15].

Table 3: Permeability Behavior in Anisotropic vs. Isotropic Hydrogel Systems

| Model Molecule | log P Value | Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Character | Anisotropic Network (PP system) | Isotropic Network (Glass system) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-phenylalanine (Phe) | -1.5 [15] | Hydrophilic (log P < 0) | Unique permeability with two induction and two permeation phases [15] | Typical diffusion behavior after initial induction phase [15] |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | -0.1 [15] | Hydrophilic (log P < 0) | Typical diffusion behavior [15] | Unique permeability with induction phase and two permeation phases [15] |

| Rhodamine B (RhB) | 2.3 [15] | Hydrophobic (log P > 0) | Typical diffusion behavior [15] | Unique permeability with induction phase and two permeation phases [15] |

This study demonstrated that anisotropic networks create hydrophobic regions that favor the transport of hydrophobic molecules like RhB, while isotropic networks, composed of water-soluble gelatin, show higher affinity for hydrophilic molecules like Phe [15]. The only differing factor was the anisotropy of the gelatin network structure, highlighting how molecular organization alone can dictate functional properties in otherwise identical compositions [15].

Case Study: 1-Arylsuccinimide Derivatives Analysis

A comprehensive study of 59 1-arylsuccinimide derivatives compared chromatographic lipophilicity across five structural series using Reverse-Phase High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (RP-HPTLC) with aprotic solvents [14]. The retention parameters (R₍M⁰) ranged from 0.678 to 3.674 in acetone and 0.280 to 3.154 in acetonitrile systems, showing significant variation based on substituents [14].

Series B (1-aryl-3,3-diphenylsuccinimide derivatives) exhibited the highest chromatographic lipophilicity, attributed to the presence of two phenyl rings, while Series C (1-aryl-3-methylsuccinimide derivatives) showed the lowest lipophilicity [14]. The study established high-quality Quantitative Structure-Retention Relationship (QSRR) models, revealing that anisotropic lipophilicity is influenced by different molecular descriptors in different solvent systems - primarily size-related descriptors in acetone and electronic features in acetonitrile [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipophilicity Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol | Standard nonpolar phase in isotropic systems [1] [7] | Shake-flask method; reference solvent for log P determination |

| Water/Buffer Solutions | Polar phase in partitioning systems [1] | Aqueous phase in both isotropic and anisotropic systems |

| Chromatographic Plates/Columns | Structured stationary phases [14] | RP-HPTLC/HPLC for anisotropic lipophilicity determination |

| Aprotic Solvents (Acetone, Acetonitrile) | Organic modifiers in mobile phases [14] | RP-HPTLC systems for maintaining anisotropic conditions |

| Polymer Templates (PP, PVC) | Induce anisotropic network formation [15] | Creating structurally controlled hydrogels for permeability studies |

| Liposomes/Artificial Membranes | Biomimetic anisotropic phases [1] | Alternative to chromatographic systems for anisotropic lipophilicity |

The comparison between isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity assessment reveals a critical dichotomy in how molecular forces are encoded and measured in different systems. Isotropic systems like n-octanol/water provide a fundamental measure of a compound's inherent partition behavior, reflecting the net balance between hydrophobicity and polarity [1]. In contrast, anisotropic systems, particularly chromatographic methods, incorporate additional factors including ionic interactions with fixed charges, more closely mimicking the structured environment of biological membranes [1] [14].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this distinction has profound practical implications. Isotropic log P values remain valuable for initial compound characterization and in silico modeling. However, anisotropic lipophilicity data often provides better correlation with biological membrane permeation and pharmacokinetic behavior, including absorption, distribution, and blood-brain barrier penetration [1] [14]. The case study of 1-arylsuccinimide derivatives demonstrates how anisotropic measurements can reveal structure-property relationships that might be obscured in isotropic systems [14].

Modern drug discovery would benefit from a tiered approach: employing rapid isotropic measurements for early-stage compound screening, followed by anisotropic characterization for lead compounds with proven biological activity. This strategy balances throughput with biological relevance, ultimately enabling more informed decisions in compound selection and optimization. As research continues to elucidate the complex interplay of hydrophobicity, polarity, and ionic forces in biological systems, the integration of both isotropic and anisotropic perspectives will remain essential for rational drug design.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Shake-Flask Method for Isotropic Lipophilicity

RP-HPTLC Protocol for Anisotropic Lipophilicity

Lipophilicity is a fundamental physicochemical property that significantly influences the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) of drug candidates [1]. It is most frequently expressed as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (Log P), which describes the distribution of a compound between a nonpolar organic solvent and an aqueous phase [16] [1]. Among various solvent systems, the n-octanol/water system has emerged as the gold standard for isotropic lipophilicity measurement. Isotropic lipophilicity refers to partitioning between two bulk, immiscible solvents where ionic charges have no defined spatial location [14]. This system serves as a critical experimental benchmark for validating computational models and chromatographic methods, providing an essential parameter for the drug discovery process [17] [18].

Experimental Methodologies for Log P Determination

The Shake-Flask Method: The Recognized Gold Standard

The shake-flask method, officially endorsed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD Test No. 107), is the definitive experimental technique for Log P determination [19]. This direct method measures the equilibrium concentrations of a compound in both phases of a biphasic n-octanol/water system [7] [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (OECD Guidelines):

- System Preparation: A two-phase system is prepared using n-octanol saturated with water and water saturated with n-octanol to prevent phase volume changes during the experiment [19].

- Temperature Control: The test is conducted at a constant temperature between 20°C and 25°C (±1°C) to ensure reproducibility [19].

- Partitioning: The compound is dissolved in one phase, and the system is agitated vigorously to facilitate partitioning between the two immiscible solvents. This is typically performed in duplicate vessels with different volume ratios of n-octanol to water across three separate runs [19].

- Phase Separation: After agitation reaches equilibrium (which can take 1-24 hours), the phases are separated, typically by centrifugation [7] [19].

- Concentration Analysis: The concentration of the test substance in both phases is quantified using appropriate analytical methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography, or photometry [7] [19].

- Validation & Calculation: The total quantity of substance recovered from both phases is compared with the amount originally introduced to validate the experiment. The partition coefficient (Pow) is then calculated for each run, with the final Log Pow values expected to fall within a range of ±0.3 units [19].

Comparison of Key Experimental Methods

While the shake-flask method remains the benchmark, several modifications and alternative approaches have been developed to address its limitations, such as being labor-intensive, time-consuming, and requiring relatively large amounts of pure compounds [7] [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Direct Experimental Methods for Log P Determination

| Method | Key Principle | Log P Range | Throughput | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask [7] [19] | Direct partitioning between n-octanol and water with agitation | -2 to 4 (up to 5) | Low | OECD standardized; Direct measurement | Time-consuming; Prone to emulsions; Requires pure compounds |

| Slow-Stirring [7] | Slow mixing to prevent emulsion formation | Up to 4.5+ | Very Low | More reliable for high Log P compounds; Prevents emulsions | Very long equilibration (2-3 days) |

| Vortex-Assisted Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (VALLME) [7] | Vortex agitation to create microdroplets increasing interfacial area | N/A | Medium | Rapid equilibrium (2 minutes); Reduced solvent consumption | Requires optimization of vortex conditions |

| Water-Plug Aspiration/Injection [7] | Specialized sampling technique to prevent phase contamination | N/A | Medium | Improved accuracy for highly lipophilic compounds | Requires specialized technique |

| Flow-Based Methods [7] | Continuous flow with in-line mixing and detection | N/A | Medium | Automated; Standardized measurement | Requires specialized equipment |

Computational and Indirect Methods for Log P Prediction

In Silico Prediction Approaches

Computational methods for Log P prediction have gained significant traction, particularly in early drug discovery where rapid property estimation is essential for virtual screening [1] [18]. These methods can be categorized into four main families:

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Log P Prediction

| Method Family | Key Principle | Representative Methods | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom-Based [18] | Summation of atomic contributions | ALOGP | Fast calculation; Simple implementation | Less accurate for complex molecules |

| Fragment-Based [20] [18] | Summation of hydrophobic fragment constants with correction factors | CLOGP, KLOGP | Better for large molecules; Accounts for interactions | Training-set dependent; Fragment library dependent |

| Topology/Graph-Based [18] | Uses topological descriptors or molecular graphs | MLOGP, Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Can capture complex patterns; No 3D structure needed | Black-box nature; Training-set dependent |

| Structural Property-Based [18] | Based on physical-chemical principles and transfer free energy | FElogP, QM/MM methods | Physically rigorous; Potentially more transferable | Computationally intensive; Requires 3D structures |

The FElogP method represents a recent advance in structural property-based approaches, utilizing molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) to calculate transfer free energy from water to n-octanol [18]. This method is based on the fundamental thermodynamic principle:

-RT ln(10) × logP = ΔGtransfer [18]

where ΔGtransfer represents the free energy change of transferring a molecule from water to n-octanol. In validation studies on 707 structurally diverse molecules, FElogP achieved a root mean square error of 0.91 log units, outperforming several popular QSPR and machine learning-based models [18].

Chromatographic Methods for Lipophilicity Assessment

Chromatographic techniques, particularly reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and thin-layer chromatography (RP-TLC/HPTLC), provide indirect measures of lipophilicity by correlating retention factors with Log P values [17] [1]. These methods are valuable for high-throughput screening and require minimal compound quantities [17] [14].

In RP-TLC, the chromatographic lipophilicity parameter (RMW) is determined by extrapolating retention data to zero concentration of organic modifier in the mobile phase [17]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse compound classes, including anti-androgen drugs and uric acid-lowering agents, showing good correlation with computational Log P values [17].

Comparative Analysis: Isotropic vs. Anisotropic Lipophilicity

While the n-octanol/water system represents the gold standard for isotropic lipophilicity, anisotropic systems using artificial or natural membranes (e.g., liposomes, chromatographic stationary phases) provide complementary information that may better mimic biological barriers [1] [14].

Key Differences:

- Intermolecular Forces: Isotropic systems encode hydrophobicity and polarity, while anisotropic systems additionally account for ionic bonds due to the fixed location of charges in membranes or stationary phases [1].

- Biological Relevance: Anisotropic systems may better mimic partitioning into biological membranes, as the distribution between phospholipid membranes and extracellular fluids represents an anisotropic environment [14].

- Measurement Output: Isotropic lipophilicity provides a well-standardized physicochemical parameter (Log P), while anisotropic measurements offer insights into membrane interactions potentially more predictive of cellular permeability [1] [14].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful determination of n-octanol/water partition coefficients requires specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table outlines essential materials for conducting these experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for n-Octanol/Water Partitioning Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Purity | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol | HPLC grade or higher; Pre-saturated with water | Organic phase mimicking biological membranes | Must be mutually saturated with water to prevent volume shifts during partitioning [19] |

| Water | Ultra-pure grade (e.g., Milli-Q); Pre-saturated with n-octanol | Aqueous phase representing biological fluids | Saturating with n-octanol ensures stable phase volumes [19] |

| Buffer Solutions | pH-specific buffers (e.g., phosphate buffer) | For Log D determination of ionizable compounds | Enables measurement at physiologically relevant pH values [16] |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC, GC, or UV-Vis spectrophotometer | Quantification of compound concentrations in both phases | HPLC provides wide applicability and low detection limits [7] |

| Centrifugation System | Capable of precise phase separation | Separates n-octanol and water phases after equilibration | Critical for obtaining pure phase samples for analysis [19] |

| Temperature Control | Thermostatic chamber or water bath (±1°C) | Maintains constant temperature during experiment | Essential for reproducible results [19] |

The n-octanol/water partition coefficient remains the gold standard isotropic system for lipophilicity assessment, providing a fundamental physicochemical parameter that profoundly influences drug discovery and development. While the shake-flask method offers the most direct and standardized measurement, various modifications and alternative approaches address specific limitations. Computational predictions provide valuable estimates, particularly in early discovery, but should be supplemented with experimental validation as compounds advance. The complementary relationship between isotropic systems like n-octanol/water and anisotropic membrane-based systems offers a more comprehensive understanding of compound behavior, enabling more effective optimization of drug candidates for desirable ADMET properties. As drug discovery continues to evolve with increasingly complex targets, the nuanced application of both isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity measurements will remain essential for developing successful therapeutic agents.

Lipophilicity is a fundamental physicochemical property that profoundly influences the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) of drug-like compounds [2]. Traditionally, lipophilicity is assessed as an isotropic property through the partition coefficient (Log P) in the n-octanol/water system, known as the "shake-flask" method. This system represents a homogeneous, isotropic environment where ionic charges have no defined spatial arrangement [14]. In contrast, anisotropic lipophilicity is determined using systems where the non-aqueous phase has a structured, organized environment with fixed spatial arrangements of ionic charges, such as chromatographic stationary phases or liposome membranes [14]. These anisotropic systems more closely mimic the biological environment where drugs must interact with organized phospholipid bilayers in cell membranes [14] [21].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of two primary anisotropic systems used in pharmaceutical research: chromatographic phases (particularly reversed-phase TLC and HPLC) and biomimetic liposomes. We examine their experimental protocols, applications, advantages, and limitations to inform method selection for drug discovery and development.

Comparative Analysis of Anisotropic Systems

Table 1: System Comparison for Lipophilicity Assessment

| Feature | Chromatographic Systems | Liposome Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Retention based on analyte interaction with stationary phase | Partition coefficient between aqueous phase and lipid bilayer |

| Key Parameters | Capacity factor (logk), RM0, C0 [9] [2] | Partition coefficient (log Kp) [22] |

| Throughput | High (multiple samples simultaneously) [2] | Moderate to low |

| Biomimetic Relevance | Moderate (structured interface) [14] | High (phospholipid bilayer similar to cell membranes) [22] [21] |

| Sample Purity | Tolerates impurities (separation occurs during analysis) [2] | Requires pure compounds |

| Consumables Cost | Low to moderate [2] | Higher (specialized lipids) |

| Technical Expertise | Moderate | High |

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

| Study Context | Chromatographic Lipophilicity Parameters | Liposome System Results |

|---|---|---|

| Triazine Derivatives [9] | logk values determined with C18 and phenyl columns with binary/ternary mobile phases | Not applicable |

| Tacrine Derivatives [2] | RM0 values: MeOH system: 1.36-2.79; ACN system: 0.93-2.31 | Not applicable |

| OECD Reference Compounds [22] | Not applicable | Log Kp values: Liposomes suitable for broad range; Micelles only for log Kp > 3 |

| Gelatin Hydrogels [15] | Not applicable | Permeability varied with logP: Phe (-1.5) vs. RhB (2.3) showed opposite permeability in anisotropic vs. isotropic networks |

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points when selecting an appropriate anisotropic system for lipophilicity assessment:

System Selection Decision Tree

Experimental Protocols for Anisotropic Lipophilicity Assessment

Chromatographic Systems (RP-TLC and RP-HPLC/UHPLC)

RP-TLC Methodology [2]:

- Stationary Phase: RP-18W F254s plates

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve compounds in MeOH (~0.5 mg/mL), apply 1.0 μL spots

- Mobile Phase: Binary mixtures of organic modifier (MeOH, ACN, dioxane, acetone) with water acidified with formic acid

- Modifier Concentration: Varying concentrations (e.g., MeOH: 0.5-0.9 v/v)

- Development: Vertical developing chamber, equilibrium with mobile phase vapor

- Detection: UV at 254 nm

- Data Analysis: Calculate RM values, extrapolate to zero organic modifier (RM0)

RP-UHPLC Methodology [9]:

- Columns: C18 (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm) or phenyl (150 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phases: Binary (methanol/water or acetonitrile/water) or ternary (methanol/acetonitrile/water) mixtures

- Modifier Volume Fraction: 0.5-0.85 v/v

- Conditions: Isocratic elution, 25°C, flow rate 0.3-0.5 mL/min

- Detection: DAD at 254 nm

- Data Analysis: Calculate capacity factor k = (tᵣ - t₀)/t₀; logk as lipophilicity index

Biomimetic Liposome Systems

Liposome Preparation & Partition Measurement [22]:

- Liposome Composition: 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine (DMPC) or mixtures with other phospholipids/cholesterol

- Preparation: Thin-film hydration or microfluidic technology [23]

- Size Control: Extrusion through polycarbonate membranes or microfluidic mixing

- Partition Determination: Derivative spectroscopy at physiological conditions (37°C, pH 7.4)

- Measurement: Compound concentration in aqueous phase before/after incubation with liposomes

- Data Analysis: Calculate partition coefficient log Kp = log(Cliposome/Cwater)

Microfluidic Liposome Fabrication [23]:

- Device: 3D-printed T-shaped microfluidic chips

- Process: Continuous flow mixing of lipid and aqueous phases

- Advantages: Monodisperse liposomes, reproducible manufacturing, precise size control

- Characterization: Dynamic light scattering, electron microscopy, protein quantification (Bradford method)

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Materials for Anisotropic Lipophilicity Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Materials | RP-18W F254s TLC plates [2] | Stationary phase for reversed-phase TLC |

| C18 and phenyl columns [9] | UHPLC stationary phases with different selectivity | |

| HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile [9] | Organic modifiers for mobile phase preparation | |

| Liposome Components | DMPC, POPC, POPS phospholipids [22] [21] | Building blocks for biomimetic membrane systems |

| Cholesterol [21] | Modifies membrane fluidity and integrity | |

| Fluorescent probes (DPH, NBD-PE, Liss Rhod PE) [21] [23] | Membrane structure and organization assessment | |

| Specialized Equipment | 3D-printed microfluidic devices [23] | Precision manufacturing of uniform liposomes |

| Vertical TLC development chambers [2] | Controlled TLC separation environment | |

| Ultracentrifugation systems [22] | Liposome separation and purification |

Applications and Data Interpretation

Chromatographic systems particularly excel in early discovery phases where high-throughput screening of structural analogs is required. The linear relationship between RM and organic modifier concentration (RM = RM0 + bC) allows extrapolation to zero organic modifier content, providing the RM0 parameter that correlates well with lipophilicity [2]. For example, in the study of tacrine derivatives, RM0 values effectively differentiated the lipophilicity of compounds with subtle structural variations [2].

Liposome systems provide superior biomimetic prediction for biological barrier permeability. Research demonstrates that liposomes are generally the preferred model for assessing drug lipophilicity, outperforming both octanol/water and micelle systems [22]. The partition coefficients obtained using biomimetic models are "quite different and more reliable than the ones obtained using an octanol/water system" [22]. This enhanced predictability stems from their structural similarity to biological membranes, particularly when complex compositions including cholesterol and anionic lipids are incorporated [21].

The anisotropic nature of chromatographic systems arises from the structured chemical environment of the stationary phase, which provides a fixed orientation of functional groups that interact differentially with analytes based on their physicochemical properties [14]. This creates a more biologically relevant system than the isotropic n-octanol/water system, though less complex than liposome bilayers.

Chromatographic phases and liposome systems offer complementary approaches for anisotropic lipophilicity assessment. Chromatographic methods provide robust, high-throughput screening suitable for early-stage discovery and compound ranking, particularly when sample purity varies. Liposome systems deliver superior biomimetic prediction for membrane permeability and biological distribution, making them invaluable for lead optimization and mechanistic studies. The choice between systems should be guided by research stage, throughput requirements, needed biological relevance, and available resources.

The Critical Role of Lipophilicity in ADMET and Pharmacodynamics

Lipophilicity is a fundamental physicochemical property defining a molecule's affinity for a lipophilic environment versus an aqueous one. It is primarily expressed as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (log P) for unionized species or the distribution coefficient (log D) for both ionized and unionized species at a specific pH [1] [8]. This property is not merely a number but a critical descriptor that influences every aspect of a drug's behavior within the body, from its initial absorption to its final excretion, as well as its interaction with the intended biological target [24] [1] [25]. The pursuit of optimal lipophilicity is central to modern drug design, as it seeks to balance potency with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of "molecular obesity" associated with excessively large and lipophilic molecules [1].

A key conceptual framework in this field is the distinction between isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity. Isotropic lipophilicity is determined using homogeneous, bulk organic solvents like n-octanol. The resulting log P value represents the net sum of hydrophobicity (which drives partitioning into the organic phase) and polarity (which favors the aqueous phase) [1]. In contrast, anisotropic lipophilicity is measured using anisotropic systems such as artificial or natural membranes (e.g., liposomes, micelles). These systems introduce topographical relationships and additional intermolecular forces, including ionic bonds, offering a more biologically relevant mimic of cellular barriers [1]. This guide will objectively compare the experimental approaches, data, and implications of research into these two paradigms of lipophilicity.

Isotropic vs. Anisotropic Lipophilicity: A Fundamental Comparison

The choice between isotropic and anisotropic models dictates the type of intermolecular forces measured and the subsequent biological inferences that can be drawn. The table below provides a structured comparison of these two approaches.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Isotropic and Anisotropic Lipophilicity

| Feature | Isotropic Lipophilicity | Anisotropic Lipophilicity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Partitioning into a homogeneous, bulk organic solvent [1] | Partitioning into an anisotropic system like a membrane [1] |

| Typical Non-Aqueous Phase | n-octanol [7] [1] | Liposomes, micelles, phospholipid bilayers [1] |

| Forces Measured | Net sum of Hydrophobicity minus Polarity [1] | Hydrophobicity, polarity, and Ionic bonds [1] |

| Biological Relevance | Models passive transport through bulk lipids; well-established for QSAR [1] | More accurately mimics interactions with complex cell membranes [1] [8] |

| Key Parameter | log P (partition coefficient) [1] | log D (distribution coefficient at specific pH) [1] |

The relationship between the intermolecular forces governed by lipophilicity and biological systems is complex. The following diagram illustrates the forces encoded in each lipophilicity type and their primary pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) consequences.

Diagram 1: Lipophilicity Types, Forces, and Biological Impacts

Impact on ADMET and Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetics (ADME)

Lipophilicity is a master regulator of a drug's journey through the body. It profoundly influences absorption, as compounds must passively permeate lipid biomembranes; the rate-limiting step for hydrophilic drugs is partitioning into the membrane, while for hydrophobic drugs, it is partitioning back into the intracellular aqueous environment [1]. Regarding distribution, lipophilic compounds tend to have a larger volume of distribution and accumulate in adipose tissue, but they also exhibit higher plasma protein binding, which can reduce their free concentration [1]. A critical aspect of distribution is Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration, which is generally enhanced by higher lipophilicity, though this can also increase affinity for efflux pumps like P-glycoprotein [24] [1]. Furthermore, lipophilicity influences metabolism and excretion, as the body often metabolizes lipophilic drugs into more polar metabolites to facilitate clearance. Highly lipophilic compounds may be stored in fatty tissues, leading to a prolonged half-life [1] [26].

Toxicity and Pharmacodynamics

Beyond pharmacokinetics, lipophilicity directly impacts safety and efficacy. High lipophilicity is a key risk factor for hERG channel binding, which can lead to cardiotoxicity by prolonging the QT interval [1]. It is also associated with target promiscuity, where compounds achieve potency through non-specific hydrophobic interactions, increasing the risk of off-target effects and toxicity [1]. From a pharmacodynamic perspective, the presence of lipophilic moieties can be crucial for interacting with hydrophobic binding pockets on target proteins, but this must be carefully balanced to maintain selectivity [1].

Experimental Data: Linking Lipophilicity to Properties and Activity

Recent studies on novel anticancer compounds provide quantitative evidence of these relationships. Research on 1,9-diazaphenothiazines showed that lipophilicity is associated with the activation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (BAX induction, cytochrome c release, and caspase 9/3 activation) [24]. The following table summarizes experimental lipophilicity data and its connection to molecular properties for a series of diquinothiazines.

Table 2: Experimental Lipophilicity and Drug-Likeness Parameters of Selected Anticancer Diquinothiazines [26]

| Compound | RM₀ (RP-TLC) | logPTLC | iLOGP (calc.) | # Violations of Lipinski's Rule | TPSA (Ų) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.02 | 3.75 | 3.22 | 0 | 32.78 |

| 5 | 1.41 | 4.65 | 4.44 | 0 | 21.76 |

| 8 | 1.10 | 3.91 | 3.56 | 0 | 41.99 |

| 11 | 1.26 | 4.29 | 3.89 | 0 | 32.78 |

This data demonstrates that computational tools like iLOGP can provide a reasonable approximation of experimental chromatographic lipophilicity (RM0), supporting their use in early drug design [26]. All listed compounds adhere to Lipinski's Rule of Five, indicating a high probability of good oral bioavailability [24] [26].

Experimental Protocols for Lipophilicity Determination

Isotropic Methods: The Gold Standard and Its Evolution

The shake-flask method is the gold standard for direct log P determination, officially recommended by the OECD. It involves dissolving the sample in a biphasic system of n-octanol and water, shaking it until equilibrium is reached (which can take 1 to 24 hours), and then measuring the compound concentration in each phase, typically using HPLC [7] [1] [26]. While accurate for log P between -2 and 4, it is labor-intensive, requires pure compounds, and is unsuitable for poorly soluble or surface-active materials [7] [1].

Several modernized methods have been developed to address these shortcomings:

- Slow-Stirring Method: Prevents emulsion formation by using slow stirring instead of shaking, providing more reliable data for log P > 4.5, albeit with longer equilibration times (2-3 days) [7].

- Vortex-Assisted Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (VALLME): Uses vortex agitation to create an n-octanol emulsion in water, dramatically increasing the interfacial area and reducing equilibrium time to just 2 minutes. The phases are separated by centrifugation, and the solute concentration is determined by LC [7].

- High-Throughput 96-Well Method: This method measures the partition coefficient between a plasticized poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) film and water in a 96-well microplate format. With 6 repeats, log Ppw values for 15 solutes can be determined in one plate in 4 hours. A linear correlation with log Pow allows this method to be used for prediction [27].

Anisotropic and Chromatographic Methods

Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RP-HPLC and RP-TLC) is a popular indirect method for determining lipophilicity. It is high-throughput, requires small sample amounts, and has a wide applicable range. The retention factor (log k) correlates with log P [26] [8]. RP-TLC, using C18 plates and a water-acetone mobile phase, has been successfully used to determine the RM0 parameter for novel diquinothiazines [26]. A significant advantage of chromatographic systems is that the stationary phase (e.g., C18-silica) is a non-polar anisotropic environment, making it more similar to partitioning into phospholipid bilayers than the isotropic n-octanol/water system [8].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a high-throughput, modern lipophilicity measurement method that can be adapted for both isotropic and anisotropic systems.

Diagram 2: High-Throughput Lipophilicity Measurement Workflow [27]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful lipophilicity research relies on a set of core materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lipophilicity Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol / Water System | The standard isotropic biphasic solvent system for direct partition coefficient measurement [7] [1]. | Shake-flask, slow-stirring, and VALLME methods [7]. |

| Plasticized PVC Film | The hydrophobic polymer phase in the 96-well high-throughput partition method [27]. | Serves as the non-aqueous phase in log Ppw determination [27]. |

| C18 Functionalized Silica | The stationary phase for reversed-phase chromatographic (RP-HPLC & RP-TLC) lipophilicity estimation [26] [8]. | Used in RP-TLC with acetone-TRIS buffer mobile phase to determine RM0 [26]. |

| TRIS Buffer (pH 7.4) | An aqueous mobile phase component that mimics physiological pH for chromatographic determination [26]. | Creates a biologically relevant environment for measuring lipophilicity in RP-TLC [26]. |

| Liposomes / Micelles | Anisotropic non-aqueous phases that mimic biological membranes for partitioning studies [1]. | Used in slow-stirring or other methods to determine anisotropic distribution coefficients [7] [1]. |

The comparative analysis of isotropic and anisotropic lipophilicity research underscores that the choice of model system is not trivial; it fundamentally shapes the interpretation of a compound's behavior. Isotropic measures like the n-octanol/water log P provide a vital, standardized metric for forecasting general absorption and informing QSAR models. However, anisotropic systems offer a more nuanced and biologically faithful representation of a drug's interaction with cellular membranes, impacting its distribution, ability to penetrate specific barriers like the BBB, and its potential for off-target effects. Modern drug discovery benefits from a hybrid approach: leveraging high-throughput computational and chromatographic methods for initial screening and rapid iteration, while employing more sophisticated anisotropic and direct measurement techniques for lead optimization to de-risk efficacy and toxicity profiles. Ultimately, framing lipophilicity within this dualistic context enables researchers to more intelligently navigate the complex trade-offs in designing effective and safe therapeutics.

Measuring Lipophilicity: From Shake-Flask to High-Throughput Chromatographic Methods

Lipophilicity, the affinity of a compound for a lipid-like environment over an aqueous one, is a fundamental property in drug discovery and development. It influences a molecule's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET). The classical methods for determining lipophilicity—shake-flask, slow-stirring, and their modern miniaturized variants—are classified as isotropic techniques. These methods measure a compound's behavior in a uniform, homogeneous chemical environment, most commonly the 1-octanol/water system. The resulting partition coefficient (log P) and distribution coefficient (log D) provide a baseline understanding of a molecule's hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance. This guide objectively compares these isotropic methodologies, detailing their protocols, performance, and appropriate applications within the broader context of lipophilicity research, which increasingly explores anisotropic systems that mimic the heterogeneous, structured nature of biological membranes [15].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, performance metrics, and applications of the primary isotropic lipophilicity assessment methods.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Classical Isotropic Lipophilicity Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Throughput | log P Range | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask [28] [29] [30] | Vigorous shaking to accelerate partitioning between 1-octanol and water phases. | Medium; can be medium-to-high when automated with LC-MS/MS for compound mixtures [29]. | Up to ~4 [30] | Considered a gold standard; well-understood; can be adapted for high-throughput [29]. | Prone to emulsion formation; cannot measure very high log P values; manual version is labor-intensive [31]. | Early-stage drug discovery for compounds with low-to-medium log P; generation of training data for in silico models [28]. |

| Slow-Stirring [31] | Gentle stirring to establish equilibrium without emulsion formation. | Low (requires prolonged stirring and multiple time points) [31]. | Up to 8.2 [31] | Eliminates emulsion issues; allows for measurement of very high log P values; OECD guideline method [31]. | Very low throughput; time-consuming (can take days); requires large volumes [31]. | Definitive measurement for highly lipophilic compounds in late-stage development or for regulatory purposes. |

| Miniaturized Variants [32] [33] | Scaling down assay volumes using microtiter plates and advanced analytical detection. | High | Varies with detection method | Dramatically reduced sample and solvent consumption (Green Analytical Chemistry); high-speed data acquisition; suitable for automation [32] [33]. | Potential for analytical interference; may not be suitable for very high log P compounds without specialized detection. | High-throughput screening in early discovery; profiling of large compound libraries; working with scarce compounds. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The Shake-Flask Method

The shake-flask method is a foundational technique for determining the partition coefficient of a compound between water-saturated 1-octanol and 1-octanol-saturated water [29] [30].

- Procedure:

- Phase Saturation: Pre-saturate 1-octanol and the aqueous buffer (at the desired pH for log D measurements) with each other by mixing them thoroughly and allowing them to separate before use.

- System Setup: Combine the test compound with both phases in a flask or vial. The volume ratio of the phases is chosen based on the expected log P to ensure measurable concentrations in both layers.

- Equilibration: Shake the mixture vigorously using an orbital shaker to create a large surface area for partitioning. The shaking frequency and diameter (e.g., up to 400 rpm [34]) are key process parameters that influence equilibration speed.

- Phase Separation: After shaking, allow the mixture to stand undisturbed until the phases separate completely. Centrifugation may be used to aid separation if emulsions form.

- Concentration Analysis: Carefully sample each phase and quantify the concentration of the test compound using a suitable analytical method, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection or tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [29].

- Data Calculation: The partition coefficient, log P, is calculated as the logarithm (base 10) of the ratio of the compound's molar concentration in the 1-octanol phase to its molar concentration in the water phase [15] [30].

The Slow-Stirring Method

The slow-stirring method, an OECD guideline (Test No. 123), is designed to measure very high log P values while avoiding the formation of emulsions [31].

- Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Water, 1-octanol, and the test substance are equilibrated at a constant temperature (e.g., 25 °C) in a thermostated, sealed stirred reactor, protected from daylight.

- Gentle Agitation: The mixture is stirred slowly and gently using a magnetic stirrer. The key is to create minimal shear stress to keep the interface between the two phases undisturbed, thus preventing emulsion formation.

- Kinetic Sampling: The concentrations of the test substance in both phases are determined at multiple consecutive time points over an extended period (potentially days). This is crucial for demonstrating that equilibrium has been attained.

- Replication: The determination must be performed using at least three independent slow-stirring experiments with identical conditions [31].

- Data Analysis: The log P is calculated from the equilibrium concentrations. A regression analysis based on at least four consecutive time points is used to confirm that the concentration ratio has stabilized, proving equilibrium has been reached [31].

Miniaturized and High-Throughput Variants

To address the demand for faster and more efficient screening, miniaturized versions of the shake-flask method have been developed.

- Procedure:

- Microplate Setup: The experiment is conducted in 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates. The pre-saturated octanol and aqueous phases, along with the test compound, are dispensed into the wells using automated liquid handlers.

- Miniaturized Equilibration: The plate is sealed and agitated on an orbital plate shaker. The small volumes and high surface-to-volume ratios can lead to faster equilibration times.

- Automated Analysis: After phase separation, samples from each phase are directly injected from the microplate into an LC-MS/MS system for quantification. A significant advancement is the ability to measure the distribution coefficients of mixtures of up to 10 compounds simultaneously by using MS detection to deconvolute the signals [29].

- Core Principle: This approach leverages the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry by drastically reducing solvent and sample consumption while increasing throughput [32] [33].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow common to these isotropic methods, highlighting the shared steps and key decision points.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful execution of these methods relies on specific laboratory materials and reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lipophilicity Assays

| Item Name | Function/Description | Critical Notes for Use |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Octanol (Water-Saturated) | Organic solvent phase modeling lipid environments. | Must be pre-saturated with the aqueous buffer to prevent volume shifts during partitioning [31]. |

| Aqueous Buffer (Octanol-Saturated) | Aqueous phase at physiologically relevant pH (e.g., pH 7.4). | Must be pre-saturated with 1-octanol. Buffer choice controls ionization for log D measurements [28]. |

| Shake Flasks / Microtiter Plates | Cultivation vessels for equilibration. | Glass shake flasks are common [34]; polypropylene 96-well plates are standard for miniaturized assays [29] [33]. |

| Orbital Shaker / Plate Shaker | Provides mechanical agitation for equilibration. | Shaking frequency and diameter are key parameters controlling oxygen transfer and mixing [34] [35]. |

| HPLC-MS/MS System | For sensitive and specific quantification of analyte concentrations in both phases. | Essential for high-throughput methods analyzing compound mixtures [29] [33]. |

| Centrifuge | Aids in separation of phases post-equilibration. | Crucial for breaking micro-emulsions that can form in the shake-flask method. |

Connecting Isotropic Data to Anisotropic Research

The data generated from isotropic methods serve as a critical foundation for understanding more complex, anisotropic biological systems. Anisotropic environments, such as cellular membranes and engineered anisotropic hydrogels, possess ordered, non-uniform structures that can selectively influence molecular permeability based on direction and molecular properties [15].

For instance, research on anisotropic gelatin hydrogels has demonstrated that they preferentially permit the permeability of hydrophobic molecules (high log P), whereas isotropic hydrogels from the same material favor the transport of hydrophilic molecules (low log P) [15]. This mirrors the selective permeability of biological membranes. Therefore, a molecule's isotropic log P value, as measured by the methods described in this guide, is a key descriptor that helps predict its behavior in these more complex, biologically relevant anisotropic environments. This establishes a direct conceptual and practical link between classical isotropic measurements and cutting-edge anisotropic lipophilicity research.

Lipophilicity represents a fundamental physicochemical property in drug discovery, traditionally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as a "partitioning equilibrium of solute molecules between water and an immiscible organic solvent, favouring the latter" [1]. Conventionally, this property is expressed as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (log P) for a solute partitioned between n-octanol (nonpolar phase) and water (aqueous phase) [1]. This classical measurement, termed isotropic lipophilicity, results from the net sum of hydrophobicity minus polarity interactions in a uniform solvent environment [1].

In contrast, anisotropic lipophilicity has emerged as a more biologically relevant concept that accounts for complex interactions with non-homogeneous phases such as artificial membranes, liposomes, and micelles [1]. These anisotropic systems establish different topographical relationships between the solute and the nonaqueous phase, incorporating additional interaction forces including ionic bonds [1]. This distinction is crucial because anisotropic lipophilicity better mimics the heterogeneous environments drugs encounter in biological systems, particularly when interacting with cell membranes and proteins [1].

Chromatographic techniques have proven invaluable for assessing anisotropic lipophilicity, as the retention parameters obtained from reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) strongly correlate with a compound's partitioning behavior in anisotropic systems [36] [37]. These chromatographic methods provide a rapid, reliable alternative to traditional shake-flask methods, especially for compounds with limited purity or availability [37].

Methodological Approaches: RP-HPLC versus HPTLC

Fundamental Principles of Chromatographic Lipophilicity Assessment

Both RP-HPLC and RP-HPTLC determine lipophilicity through a compound's retention behavior in reversed-phase systems, where the stationary phase is nonpolar and the mobile phase is polar. The underlying principle states that more lipophilic compounds exhibit stronger interactions with the stationary phase, resulting in longer retention times (in HPLC) or lower migration distances (in TLC) [37].

In RP-HPLC, lipophilicity is typically expressed as the capacity factor (log k), calculated as log k = log[(tr - t0)/t0], where tr is the retention time of the compound and t0 is the dead time of the system [9]. For isocratic measurements, the extrapolated value log k0 (determined at 0% organic modifier) provides a standardized lipophilicity measure [36] [37].

In RP-HPTLC, lipophilicity is expressed as the RM value, calculated as RM = log[(1/Rf) - 1], where Rf is the retardation factor [38]. Similar to HPLC, the extrapolated value RM0 (determined at 0% organic modifier) serves as the chromatographic lipophilicity index [36] [37].

Experimental Protocols for Anisotropic Lipophilicity Determination

RP-HPLC Methodology

The typical RP-HPLC protocol for determining anisotropic lipophilicity involves the following steps [36] [37] [9]:

Stationary Phase Selection: Common columns include octadecyl (C18) or phenyl-modified silica columns. The phenyl columns are particularly valuable for compounds containing aromatic rings due to their ability to form π-π interactions [9].

Mobile Phase Preparation: Binary mixtures (methanol/water or acetonitrile/water) or ternary mixtures (methanol/acetonitrile/water) are used. The organic modifier content typically ranges from 50% to 85% (v/v) [9].

System Equilibration: The column is equilibrated with the mobile phase until a stable baseline is achieved.

Sample Preparation: Compounds are dissolved in appropriate solvents (e.g., acetone, methanol) at concentrations of approximately 1 mg/mL, followed by filtration [9].

Chromatographic Analysis: Samples are injected (typically 10 μL injection volume), and analyses are performed under isocratic conditions at controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C) [9].

Detection: UV detection at appropriate wavelengths (e.g., 254 nm for triazine derivatives) is commonly employed [9].

Data Processing: Retention times are recorded, and capacity factors (log k) are calculated. Plotting log k against organic modifier percentage and extrapolating to 0% modifier yields the log k0 parameter [37].

RP-HPTLC Methodology

The standard RP-HPTLC protocol involves these key steps [38] [37]:

Stationary Phase Preparation: Commercially available RP-HPTLC plates (e.g., C8 or C18 modified silica gel) are used without pretreatment.

Mobile Phase Selection: Various organic modifiers including methanol, acetonitrile, and dioxane are mixed with water in different proportions [38].

Sample Application: Compounds are spotted 1-1.5 cm from the bottom edge of the HPTLC plate using micropipettes.

Chromatogram Development: The mobile phase ascends through the stationary phase in a saturated chromatographic chamber until the solvent front reaches a predetermined distance.

Detection: UV light at appropriate wavelengths or specific staining reagents are used to visualize spots.

Data Processing: Rf values are determined, RM values calculated, and plots of RM versus organic modifier concentration are used to derive RM0 values [37].

Comparative Experimental Data: RP-HPLC versus HPTLC Performance

Case Study: Succinimide Derivatives

A comprehensive study on 1-aryl-3-ethyl-3-methylsuccinimide derivatives demonstrated strong correlation between RP-HPLC and RP-HPTLC determinations of anisotropic lipophilicity [36] [37]. The researchers determined log k0 values using RP-HPLC with methanol/water mobile phases and RM0 values using RP-HPTLC, with high determination coefficients (R² ≥ 0.99) for the correlations between organic modifier content and retention parameters [37].

Table 1: Lipophilicity Parameters of Selected Succinimide Derivatives [37]

| Compound | Substituent | RP-HPLC log k₀ | RP-HPTLC Rₘ₀ | Computational log P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4-Br | 1.32 | 1.45 | 2.47 |

| 2 | 4-Cl | 1.29 | 1.41 | 2.37 |

| 3 | 4-CN | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.32 |

| 4 | 4-COOH | 0.42 | 0.51 | 1.21 |

| 5 | 4-OH | 0.38 | 0.46 | 1.15 |

The study revealed that halogenated derivatives (compounds 1 and 2) exhibited the highest lipophilicity, while hydroxyl and carboxyl-substituted derivatives (compounds 4 and 5) showed the lowest lipophilicity [37]. Most significantly, strong linear relationships were observed between chromatographic parameters (log k0 and RM0) and computed log P values, validating both chromatographic approaches as reliable measures of anisotropic lipophilicity [37].

Case Study: Thiadiazole Derivatives

Another comparative investigation on 5-heterocyclic 2-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1,3,4-thiadiazoles employed multiple chromatographic approaches including RP-HPLC with C8, C18, phosphatidylcholine (IAM), and cholesterol stationary phases, alongside RP-HPTLC with C8 and C18 phases [38]. The researchers found that dioxane and methanol were particularly beneficial organic modifiers for lipophilicity estimation in HPTLC [38].

Table 2: Comparison of Chromatographic Methods for Thiadiazole Derivatives [38]

| Method | Stationary Phase | Organic Modifiers | Correlation with Computational log P | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP-HPLC | C18, C8, IAM, Cholesterol | Methanol, Acetonitrile | Strong correlation (85% redundancy) | High precision, automation capability |

| RP-HPTLC | C18, C8 | Methanol, Dioxane | Strong correlation (85% redundancy) | High throughput, low solvent consumption |

| In silico | - | - | Reference method for validation | Rapid screening |

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the results demonstrated that chromatographic lipophilicity parameters (log kw and RMw) were well correlated and showed high redundancy (85%) compared with computed values [38]. Most tested compounds exhibited lipophilicity parameters within the recommended range for drug candidates, demonstrating the utility of these methods in early drug development [38].

Correlation with Pharmacokinetic Properties

Chromatographically determined anisotropic lipophilicity parameters show significant correlations with key pharmacokinetic properties. Research on succinimide derivatives demonstrated that log k0 and RM0 values strongly influence plasma protein binding (PPB), Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cell permeability, volume of distribution (Vd), and absorption constant (Ka) [36] [37].

These correlations are mechanistically explained by the fact that anisotropic lipophilicity captures not just hydrophobic interactions but also polarity and ionic contributions that mirror the complex biological environments drugs encounter in vivo [1]. For instance, compounds with moderate anisotropic lipophilicity (log k0 values around 1.0-1.5 in succinimides) demonstrated optimal balance between permeability and solubility, resulting in favorable absorption and distribution profiles [37].

Additionally, anisotropic lipophilicity parameters have proven valuable in predicting blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, with studies applying Clark's rules and Pre-ADMET software demonstrating that moderately lipophilic compounds (log k0 ~ 1.0-2.0) generally exhibit better BBB penetration potential [37]. This application is particularly relevant for central nervous system-active drugs such as anticonvulsant succinimide derivatives [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chromatographic Lipophilicity Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Modified Columns | Stationary phase for RP-HPLC | ZORBAX Eclipse C18, 2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 µm [9] |

| Phenyl Modified Columns | Stationary phase for π-π interactions | ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-Phenyl, 95 Å, 2.1 × 150 mm, 5 µm [9] |

| RP-HPTLC Plates | Stationary phase for thin-layer chromatography | C8 or C18 modified silica gel plates [38] |

| HPLC-grade Methanol | Protic organic modifier for mobile phase | HPLC gradient grade, J.T. Baker [9] |

| HPLC-grade Acetonitrile | Aprotic organic modifier for mobile phase | For HPLC analysis, Acros Organics [9] |

| HPLC-grade Water | Aqueous component of mobile phase | HPLC grade distilled water [9] |

| Reference Compounds | System suitability testing | Compounds with known lipophilicity values [37] |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Chromatographic Lipophilicity Determination Workflow

Isotropic vs. Anisotropic Lipophilicity Concepts

Chromatographic determination of anisotropic lipophilicity using RP-HPLC and HPTLC provides a sophisticated approach that transcends traditional isotropic measurements. Both techniques offer distinct advantages: RP-HPLC delivers high precision and automation capability, while RP-HPTLC enables high-throughput analysis with minimal solvent consumption [38] [37].

The strong correlations between chromatographic parameters and key pharmacokinetic properties underscore the biological relevance of anisotropic lipophilicity measurements [36] [37]. Furthermore, the consistency between RP-HPLC and RP-HPTLC results, as demonstrated in multiple case studies, validates both approaches for reliable lipophilicity assessment in drug discovery [38] [37].

For optimal results, researchers should consider employing both techniques complementarily—using HPTLC for rapid screening of compound libraries and HPLC for detailed characterization of promising candidates. This integrated approach provides a comprehensive understanding of anisotropic lipophilicity, enabling more efficient optimization of drug candidates with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles.

Lipophilicity is a fundamental physicochemical property defined as the affinity of a molecule or a moiety for a lipophilic environment, commonly measured by its distribution behavior in a biphasic system [39]. In medicinal chemistry, it is crucial for explaining a compound's distribution in biological systems and is a key parameter in the drug discovery pipeline [1] [39]. Lipophilicity is primarily expressed as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (log P) for a solute between n-octanol and water, or as the distribution coefficient (log D), which accounts for all forms of a compound (neutral and ionized) at a given pH [1]. This property affects every pharmacokinetic component—absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET)—and also influences pharmacodynamic behavior by helping to explain ligand-target interactions [1]. The determination of lipophilicity can be broadly categorized into two approaches: isotropic methods, which use homogeneous solvents like n-octanol, and anisotropic methods, which use membrane-like systems such as liposomes or immobilized artificial membranes (IAMs) [1]. Isotropic lipophilicity results from the net sum of hydrophobicity minus polarity, whereas anisotropic lipophilicity also incorporates ionic bonds, meaning they express lipophilicity on different scales and encode different intermolecular forces [1]. This guide compares high-throughput approaches for determining these lipophilicity parameters, focusing on the central role of 96-well microplates and automated workflows.