Integrating Molecular Docking with ADMET Prediction: Strategies for Accelerating Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated computational approach of molecular docking and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling in modern drug discovery.

Integrating Molecular Docking with ADMET Prediction: Strategies for Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated computational approach of molecular docking and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling in modern drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, current methodological applications including machine learning advances, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation frameworks. The content synthesizes recent research to offer practical strategies for leveraging these in silico techniques to prioritize lead compounds, de-risk development, and improve clinical success rates by simultaneously optimizing for target affinity and desirable pharmacokinetic properties.

The Essential Role of ADMET and Docking in Modern Drug Development

Why ADMET Properties are a Leading Cause of Drug Candidate Failure

The journey of a drug candidate from the laboratory to the clinic is fraught with challenges, with suboptimal Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties representing the most significant hurdle. It has been reported that approximately 30% of preclinical candidate compounds (PCCs) fail due to toxicity issues, making adverse toxicological reactions the leading cause of drug withdrawal from the market [1]. Furthermore, inadequate ADMET profiles account for approximately 40% of failures in preclinical candidate drugs [1]. These statistics underscore the strategic importance of comprehensive ADMET assessment early in the drug development pipeline, as these properties directly influence a drug's bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and safety profile [2] [3].

Traditional ADMET assessment paradigms rely heavily on in vivo animal experiments and in vitro assays, which are often costly, time-consuming (typically 6-24 months), and ethically controversial [1]. The protracted timelines and high costs per compound (often exceeding millions of dollars) associated with these traditional approaches no longer meet modern ethical and efficiency standards [1]. This has spurred the rapid emergence of computational toxicology, which integrates quantum chemical calculations, molecular dynamics simulations, machine learning algorithms, and multi-omics datasets to develop mechanism-based predictive models, thereby shifting from an "experience-driven" to a "data-driven" evaluation paradigm [1].

The Scale of the Problem: Quantitative Impact of ADMET Failures

The quantitative impact of ADMET properties on drug development success rates is profound. The high attrition rates directly attributed to ADMET deficiencies highlight the critical need for early and accurate prediction. The following table summarizes key statistical data on ADMET-related drug failures:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of ADMET Properties on Drug Development Attrition

| Failure Point | Failure Rate | Primary ADMET Causes | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical Candidate Compounds | ~30% | Toxicity issues [1] | Candidate withdrawal before clinical trials |

| Preclinical Candidate Drugs | ~40% | Insufficient ADMET profiles [1] | Failure before human testing |

| Marketed Drugs | Leading cause of withdrawal | Unforeseen toxic reactions [1] | Post-market recalls, patient harm |

The financial implications of these failures are staggering, with development costs for a single drug often exceeding millions of dollars [1]. Beyond the economic impact, inadequate ADMET prediction poses significant public health risks, as demonstrated by historical cases like thalidomide and fialuridine which underscored the limitations of traditional preclinical testing in capturing human-relevant toxicities [4].

Key ADMET Failure Mechanisms and Biological Pathways

Organ-Specific Toxicity Pathways

Drug candidates frequently fail due to organ-specific toxicities that may not be detected until late-stage development. Understanding the biological pathways underlying these toxicities is essential for developing predictive models:

Hepatotoxicity: Hepatic damage is generally characterized by elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin levels [1]. The liver's role as the primary site of drug metabolism makes it particularly vulnerable to drug-induced injury through mechanisms such as metabolic activation, covalent binding, and oxidative stress [4].

Cardiotoxicity: This is frequently associated with hERG channel inhibition, which can lead to fatal arrhythmias [1] [4]. Regulatory agencies require comprehensive hERG assay data to assess this cardiotoxicity risk [4].

Nephrotoxicity: Kidney damage can be detected through elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen measurements [1]. The kidneys' role in drug excretion exposes them to high concentrations of compounds and their metabolites.

Metabolic and Pharmacokinetic Failure Pathways

CYP450 Inhibition: Drug-induced inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes (particularly CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4) represents a major metabolic failure pathway, as it can lead to dangerous drug-drug interactions and altered metabolic profiles [4] [5]. These interactions are a focus of regulatory requirements from agencies like the FDA and EMA [4].

Poor Absorption and Bioavailability: Inadequate intestinal absorption, often predicted through models like Caco-2 cell permeability and human intestinal absorption (HIA), remains a common cause of failure [5]. The Rule of Five (molecular weight <500 Da, LogP <5, hydrogen bond donors <5, hydrogen bond acceptors <10) serves as an initial filter for predicting oral bioavailability [6] [5].

Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration: For CNS-targeted drugs, insufficient blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration can lead to lack of efficacy, while unintended BBB penetration for non-CNS drugs can cause neurotoxicity [5].

Figure 1: ADMET Failure Pathways Leading to Drug Candidate Attrition

Computational Protocols for ADMET Assessment

Integrated Computational Workflow for ADMET Prediction

The following workflow represents a comprehensive protocol for computational ADMET assessment integrated with molecular docking studies:

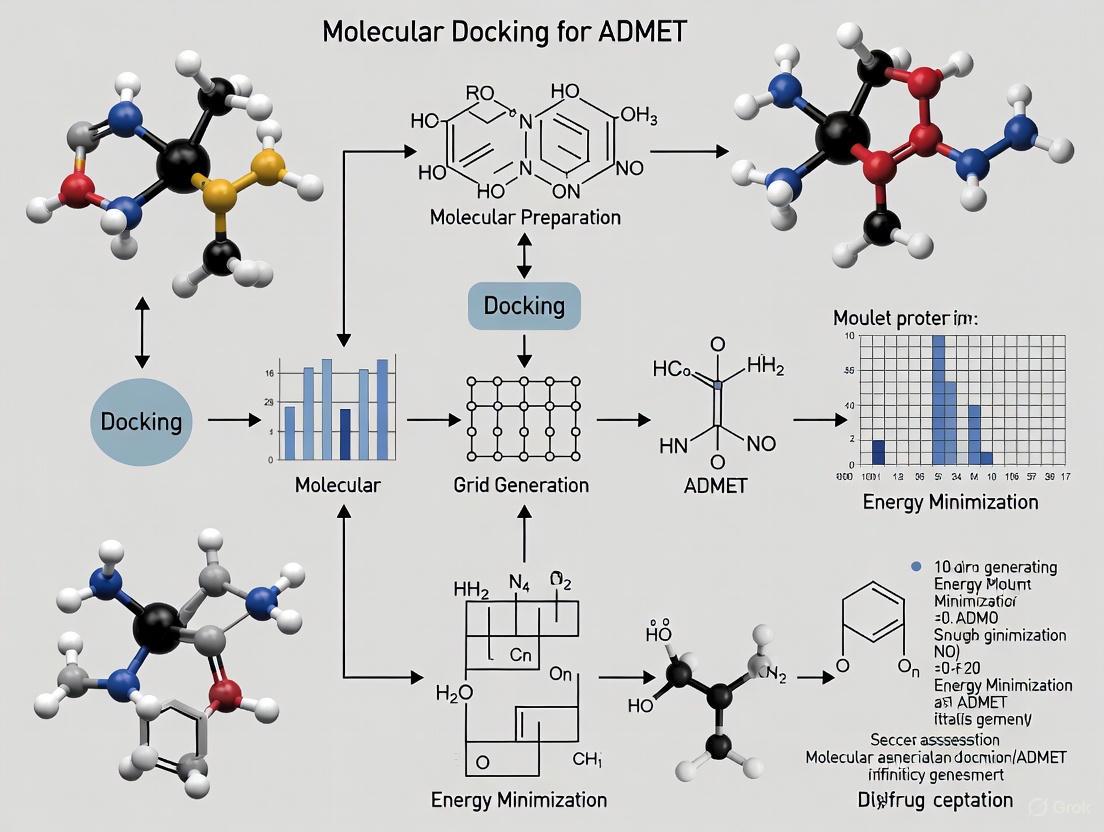

Figure 2: Integrated Computational ADMET Assessment Workflow

Molecular Docking Protocol for Binding Affinity Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the binding affinity and interaction模式 of candidate compounds with target proteins and off-target receptors relevant to ADMET properties.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB): Source of 3D protein structures (e.g., BACE1, PDB ID: 6ej3) [6]

- Schrödinger Suite: Comprehensive software for molecular modeling including GLIDE module for docking [6]

- ZINC Database: Repository of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [6]

- RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for molecular descriptor calculation [1]

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation:

Ligand Preparation:

Docking Validation:

- Re-dock co-crystallized ligand to validate docking protocol

- Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD); values ≤2 Å are acceptable [6]

- Establish docking reliability before proceeding with virtual screening

Virtual Screening Workflow:

Analysis of Docking Results:

- Evaluate binding energy (G-score; values ≤-7 kcal/mol indicate strong binding) [6]

- Identify key ligand-protein interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions)

- Analyze binding modes and structural determinants of affinity

ADMET Property Prediction Protocol

Objective: To predict key ADMET properties using computational models and integrate these predictions with docking results for comprehensive candidate evaluation.

Materials and Platforms:

- pkCSM: Online platform for pharmacokinetic prediction [5]

- ADMETlab 2.0/3.0: Comprehensive ADMET prediction platform [4]

- SwissADME: Web tool for physicochemical and ADME property prediction [6]

- Multi-task Graph Learning Models: Advanced ML frameworks for ADMET endpoint prediction [7]

Methodology:

- Input Preparation:

- Generate SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) notations for compounds

- Calculate molecular descriptors (molecular weight, logP, TPSA, H-bond donors/acceptors) [1]

Absorption Prediction:

Distribution Prediction:

- Predict blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration using qualitative (CNS +/-) or quantitative (logBB) models [5]

- Evaluate volume of distribution and plasma protein binding

Metabolism Prediction:

- Assess CYP450 inhibition potential for major isoforms (2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4) [5]

- Predict CYP450 substrate specificity

- Identify potential metabolic sites

Excretion Prediction:

- Predict total clearance values

- Assess renal excretion mechanisms

Toxicity Prediction:

Advanced Machine Learning Protocols for ADMET Prediction

Objective: To implement advanced machine learning and multi-task learning approaches for improved ADMET endpoint prediction.

Materials and Frameworks:

- MTGL-ADMET: Multi-task graph learning framework for ADMET prediction [7]

- PharmaBench: Large-scale benchmark dataset for ADMET model development [2]

- Receptor.AI Platform: Advanced ADMET prediction with descriptor augmentation [4]

Methodology:

- Data Curation and Preprocessing:

Molecular Featurization:

Model Training and Validation:

- Implement multi-task learning architecture with "one primary, multiple auxiliaries" approach [7]

- Utilize graph neural networks for structure-property relationship learning [7]

- Apply adaptive auxiliary task selection using status theory and maximum flow algorithms [7]

- Validate models using rigorous cross-validation and external test sets

Model Interpretation and Explainability:

- Identify key molecular substructures related to specific ADMET endpoints [7]

- Implement attention mechanisms for feature importance visualization

- Generate model explanations for regulatory acceptance

Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Assessment

The following table details essential research reagents, computational tools, and databases required for comprehensive ADMET assessment:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ADMET Assessment

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Platforms | Schrödinger Suite | Molecular docking, dynamics, and ADMET prediction [6] | Integrated drug discovery workflows |

| SwissADME | Physicochemical property and ADME prediction [6] | Rapid screening of drug-likeness | |

| pkCSM | Pharmacokinetic parameter prediction [5] | Absorption and distribution modeling | |

| ADMETlab 2.0/3.0 | Comprehensive ADMET endpoint prediction [4] | Multi-parameter optimization | |

| Databases | ZINC Database | Repository of commercially available compounds [6] | Virtual screening compound source |

| ChEMBL | Curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [2] | Model training and validation | |

| PharmaBench | Large-scale ADMET benchmark dataset [2] | Machine learning model development | |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | 3D protein structures for molecular docking [6] | Target structure-based design | |

| Experimental Assays | Caco-2 Cell Model | Prediction of intestinal permeability [5] | Absorption potential assessment |

| hERG Assay | Cardiotoxicity risk assessment [4] | Safety pharmacology | |

| CYP450 Inhibition Assays | Metabolic stability and drug interaction potential [4] | Metabolism characterization | |

| Human Liver Microsomes | Metabolic stability assessment [1] | Clearance prediction | |

| Advanced Algorithms | MTGL-ADMET Framework | Multi-task graph learning for ADMET prediction [7] | Integrated property optimization |

| Mol2Vec Embeddings | Molecular structure representation for ML [4] | Feature generation for AI models | |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Data extraction from scientific literature [1] [2] | Automated data curation |

The integration of computational ADMET assessment, particularly when combined with molecular docking studies, represents a transformative approach to addressing the leading cause of drug candidate failure. The protocols outlined in this document provide a framework for researchers to systematically evaluate and optimize ADMET properties early in the drug discovery pipeline. By leveraging advanced computational methods, including multi-task machine learning, molecular dynamics simulations, and comprehensive virtual screening, researchers can significantly reduce late-stage attrition rates and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

The future of ADMET prediction lies in the continued development of more accurate, interpretable, and biologically-relevant models that can better capture the complexity of human physiology and disease. As computational power increases and novel algorithms emerge, the integration of these tools into standard drug discovery workflows will become increasingly essential for success in the pharmaceutical industry.

Molecular Docking as a Tool for Predicting Protein-Ligand Interactions and Binding Affinity

Molecular docking stands as a pivotal computational technique in structure-based drug design (SBDD), consistently contributing to advancements in pharmaceutical research [8]. In essence, it employs algorithms to identify the optimal binding mode between a small molecule (ligand) and a biological target (receptor), predicting the three-dimensional structure of the resulting complex and estimating the binding affinity [8] [9]. This process assumes particular significance in unraveling the mechanistic intricacies of physicochemical interactions at the atomic scale, with wide-ranging implications for virtual screening and lead optimization [8] [6]. Within the broader context of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) property assessment research, molecular docking provides a crucial structural understanding of how ligands interact with their protein targets, complementing other predictive models to de-risk drug candidates early in the development pipeline [10].

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Docking

Physical Basis of Protein-Ligand Interactions

Protein-ligand interactions are central to the in-depth understanding of protein functions in biology because proteins accomplish molecular recognition through binding with various molecules [8]. These interactions are primarily governed by non-covalent forces, which, despite being individually weak (typically 1–5 kcal/mol), produce highly stable and specific associations through cumulative effects [8] [9].

The four main types of non-covalent interactions in biological systems are:

- Hydrogen bonds: Polar electrostatic interactions between an electron donor (D) and acceptor (A) in the form of D—H…A, with a strength of about 5 kcal/mol [8].

- Ionic interactions: Electronic attraction between oppositely charged ionic pairs, highly specific but influenced by the aqueous solvent environment [8].

- Van der Waals interactions: Nonspecific forces resulting from transient dipoles in electron clouds when atoms approach closely, with approximately 1 kcal/mol strength [8].

- Hydrophobic interactions: Entropy-driven aggregation of nonpolar molecules excluding themselves from the aqueous solvent [8].

Table 1: Major Non-Covalent Interactions in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Interaction Type | Strength (kcal/mol) | Nature | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | ~5 | Polar | Directional, specific D—H…A pattern |

| Ionic Interactions | 3-8 | Electrostatic | Strong, distance-dependent, solvent-influenced |

| Van der Waals | ~1 | Non-polar | Non-specific, cumulative effect important |

| Hydrophobic | 1-5 | Entropic | Driven by solvent exclusion |

The net driving force for binding is quantified by the Gibbs free energy equation: ΔGbind = ΔH - TΔS, where ΔG represents the change in free energy, ΔH the enthalpy change from bonds formed and broken, and ΔS the entropy change reflecting system randomness [8] [9]. The binding free energy directly correlates with the equilibrium binding constant (Keq), which can be determined experimentally from kinetic rate constants [8].

Molecular Recognition Models

Three conceptual models explain the mechanisms of molecular recognition:

- Lock-and-key model: Theorizes that binding interfaces are pre-formed and complementarily matched, with both protein and ligand remaining rigid—an entropy-dominated process [8].

- Induced-fit model: Proposes that conformational changes occur in the protein during binding to optimally accommodate the ligand, adding flexibility to Fisher's original idea [8].

- Conformational selection model: Suggests ligands bind selectively to the most suitable conformational state among an ensemble of protein substates, with possible subsequent rearrangements [8].

Molecular Docking Methodologies

Conformational Search Algorithms

Docking programs employ various search algorithms to explore the conformational space available to the ligand within the binding site. These methods can be broadly classified into two categories:

Systematic Methods:

- Systematic Search: Rotates all possible rotatable bonds by fixed intervals to exhaustively explore conformations, using "bump checks" to prune sterically clashed rotations. Implemented in Glide and FRED [9].

- Incremental Construction: Fragments the molecule into rigid components, docks them into suitable sub-pockets, then systematically builds linkers. Used in FlexX and DOCK [9].

Stochastic Methods:

- Monte Carlo: Uses random sampling with Boltzmann-weighted acceptance criteria to explore conformational space. Employed in Glide for pose refinement [9].

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): Mimics natural selection by encoding conformational degrees of freedom as binary strings, applying mutations and cross-over operations. Implemented in AutoDock and GOLD [9].

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are designed to reproduce binding thermodynamics by estimating the binding affinity of predicted poses [9] [11]. They can be categorized as:

- Force-field based: Calculate energies using molecular mechanics terms for van der Waals, electrostatic, and sometimes solvation contributions [11].

- Empirical: Parameterized using experimental binding data, summing weighted energy terms representing different interaction types [11].

- Knowledge-based: Derived from statistical analyses of atom-pair frequencies in known protein-ligand complexes [11].

GlideScore, for example, is an empirical scoring function that includes terms for lipophilic interactions, hydrogen bonding, rotatable bond penalty, and hydrophobic enclosure—where ligands displace water molecules from areas with many proximal lipophilic protein atoms [11].

Diagram 1: Molecular Docking Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Docking

Protein Preparation Protocol

Objective: Generate an accurate, minimized protein structure for docking simulations.

Methodology:

- Retrieve 3D Structure: Obtain the target protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB ID: 6ej3 for BACE1) [6].

- Preprocess Structure:

- Remove crystallographic water molecules, except those mediating key interactions

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and complete partial side chains

- Assign appropriate protonation states for acidic and basic residues at physiological pH

- Energy Minimization:

- Optimize hydrogen bonding network

- Perform restrained minimization using force fields (e.g., OPLS2005) to relieve steric clashes

- Apply convergence criteria of 0.3 Å RMSD for heavy atoms [6]

Ligand Preparation Protocol

Objective: Generate accurate, energetically minimized 3D structures for database compounds.

Methodology:

- Compound Sourcing: Access natural compound libraries (e.g., ZINC database containing >80,000 molecules) [6].

- Filter by Drug-likeness: Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five criteria:

- Molecular weight < 500 Da

- LogP < 5

- Hydrogen bond donors < 10

- Hydrogen bond acceptors < 10 [6]

- Generate Tautomers and States:

- Generate possible ionization states at pH 7.4 ± 0.5

- Create stereoisomers and tautomers where applicable

- Generate low-energy 3D conformers (minimum 10 per ligand) [6]

- Energy Minimization: Optimize geometries using appropriate force fields (e.g., OPLS2005) [6].

Docking Validation Protocol

Objective: Validate docking parameters and methodology prior to large-scale screening.

Methodology:

- Re-docking Validation:

- Enrichment Studies (for virtual screening):

Table 2: Docking Precision Modes and Performance Characteristics (Glide)

| Precision Mode | Speed (compounds/sec) | Use Case | Sampling Thoroughness | Pose Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTVS (High Throughput Virtual Screening) | ~0.5 | Ultra-large library screening (>1M compounds) | Limited | Lower, but sufficient for hit identification |

| SP (Standard Precision) | ~0.1 | Intermediate library screening | Balanced | Good (85% success rate with <2.5Å RMSD) |

| XP (Extra Precision) | ~0.008 | Lead optimization, top-hit analysis | Exhaustive | Highest, better enrichment in known actives |

Molecular Dynamics Refinement Protocol

Objective: Refine docked poses and account for protein flexibility through dynamics simulations.

Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an orthorhombic box with TIP3P water molecules

- Add 0.15 M NaCl to neutralize system charge

- Apply periodic boundary conditions [6]

- Simulation Parameters:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software Solutions for Molecular Docking and ADMET Assessment

| Software/Resource | Type | Key Features | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial Platform | Glide docking, Prime MM/GBSA, QM-Polarized Ligand Docking | High-accuracy pose prediction and binding affinity estimation [6] [11] |

| AutoDock | Free Software | Genetic algorithm, empirical scoring function | Academic research, molecular docking education [9] |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial Suite | All-in-one molecular modeling, cheminformatics, QSAR | Structure-based design and protein engineering [14] |

| ZINC Database | Public Repository | >80,000 purchasable compounds, natural product libraries | Virtual screening compound source [6] |

| Protein Data Bank | Public Database | Experimental 3D structures of proteins and complexes | Source of target structures for docking studies [8] |

| SwissADME | Web Tool | ADMET prediction, drug-likeness analysis | Rapid pharmacokinetic profiling of docked hits [6] |

| DeepMirror | AI Platform | Generative AI for molecular design, property prediction | Hit-to-lead optimization, reducing ADMET liabilities [14] |

Advanced Applications in ADMET Assessment

Integration with ADMET Prediction

Molecular docking provides critical structural insights that complement data-driven ADMET prediction models [10]. Key integration points include:

- Metabolism Prediction: Docking against cytochrome P450 isoforms (CYP3A4, CYP2D6) to identify potential metabolic soft spots and inhibitory interactions [10] [13].

- Toxicity Assessment: Screening against anti-targets like hERG potassium channel to predict cardiotoxicity risks, and nuclear receptors for endocrine disruption potential [10].

- Distribution and BBB Penetration: Evaluating interactions with transport proteins (P-glycoprotein) and predicting blood-brain barrier permeability based on interaction profiles [6] [13].

AI-Enhanced Docking Approaches

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are transforming molecular docking methodologies:

- Geometric Deep Learning: Graph neural networks that incorporate spatial features of interacting atoms to improve binding pocket descriptions and pose predictions [9] [15].

- Diffusion Models: Generative approaches that progressively refine ligand poses, showing improved performance in binding mode prediction [15].

- Hybrid AI-Physics Models: Integrating deep learning with physical constraints to enhance scoring functions and virtual screening accuracy beyond traditional methods [15].

Diagram 2: Docking Integration with ADMET Assessment

Best Practices and Troubleshooting

Controls and Validation

To enhance the likelihood of successful docking outcomes, implement these control measures:

- Pose Reproduction: Validate methodology by re-docking native ligands, requiring RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å from crystal structure [6] [9].

- Decoy-based Enrichment: Assess virtual screening performance using datasets like DUD-E containing known actives and property-matched decoys [12] [11].

- Multiple Conformational Sampling: Account for receptor flexibility by docking against multiple protein conformations when available [9] [11].

Common Challenges and Solutions

- Protein Flexibility: When induced fit effects are significant, employ Induced Fit Docking protocols that sample side-chain conformational changes [11].

- Scoring Function Inaccuracy: Use consensus scoring approaches or post-docking MM/GBSA refinement to improve binding affinity rankings [9] [11].

- Solvation Effects: Consider explicit water molecules in the binding site when they mediate key protein-ligand interactions [9].

- Charge Assignment: Ensure appropriate protonation states for ligand and protein functional groups, particularly histidine residues and acidic/basic moieties [9].

Molecular docking remains an indispensable tool in the drug discovery pipeline, providing atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions that inform lead optimization and ADMET assessment. When properly validated and integrated with complementary computational and experimental approaches, docking methodologies significantly enhance the efficiency of structure-based drug design. The continuing evolution of docking algorithms, particularly through integration with artificial intelligence and enhanced treatment of flexibility, promises to further improve the accuracy and applicability of these methods in pharmaceutical research. For researchers focused on ADMET property assessment, molecular docking offers the crucial structural context needed to interpret and predict the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of novel therapeutic candidates.

Within modern drug discovery, the assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is fundamental for determining the clinical success of candidate molecules. These properties define the pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety profiles of a compound, directly influencing its bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and likelihood of regulatory approval [3]. Notably, poor ADMET characteristics are a major contributor to the high attrition rates observed in late-stage clinical development, accounting for approximately half of all failures [3] [10] [16].

The integration of in silico methodologies, particularly molecular docking and machine learning (ML), has revolutionized early-stage ADMET evaluation. These computational tools provide rapid, cost-effective, and scalable alternatives to traditional resource-intensive experimental assays, enabling higher-throughput screening and more informed lead optimization [3] [10]. This application note details the protocols for predicting four critical ADMET endpoints—solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and toxicity—framed within the context of a molecular docking and modeling research workflow.

Key ADMET Endpoints: Application Notes & Protocols

The following sections provide a detailed examination of the four key ADMET endpoints, including their biological significance, standard computational prediction methodologies, and relevant experimental benchmarks.

Aqueous Solubility

Biological Significance & Prediction Context Aqueous solubility is a critical determinant of a drug's absorption potential, as a compound must be in solution to permeate biological membranes. Poor solubility is a frequent cause of low oral bioavailability [3]. In silico models predict solubility to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of adequate dissolution in the gastrointestinal tract.

Computational Prediction Protocol Machine learning models have demonstrated significant promise in predicting solubility endpoints, often outperforming traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [10]. The standard protocol involves:

- Data Collection and Curation: Utilize large-scale, high-quality solubility datasets from public repositories such as the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [17] [18].

- Molecular Featurization: Represent molecules using descriptors that capture structural and physicochemical properties relevant to solvation. Common approaches include:

- Molecular Descriptors: Calculate using software like RDKit, PaDEL, or Mordred. These can include constitutional descriptors (e.g., molecular weight), topological descriptors, and electronic descriptors [10] [16].

- Graph-Based Representations: Model the molecule as a graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) for input into graph neural networks (GNNs) [3] [17].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Incorporate 3D electronic properties (e.g., dipole moment, HOMO-LUMO gap) for a more physically-grounded representation [18].

- Model Training and Validation: Train ML models (e.g., Random Forests, Gradient Boosting, or GNNs) on the featurized data. Employ rigorous validation strategies such as scaffold splitting or temporal splitting to ensure model generalizability to novel chemical classes [17] [16]. The ADMET Benchmark Group promotes standardized metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² for regression tasks [16].

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Solubility Prediction Models

| Model Class | Molecular Representation | Reported Metric | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosted Trees [16] | ECFP, RDKit Descriptors | R², MAE | Highly competitive, state-of-the-art on several benchmarks |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [3] [17] | Molecular Graph | MAE | Captures complex structure-property relationships |

| Transformer (MSformer-ADMET) [17] | Fragment-based Meta-Structures | Superior Performance vs. Baselines | Demonstrates robust performance across TDC benchmarks |

| Quantum-Enhanced MTL (QW-MTL) [18] | RDKit + Quantum Descriptors | AUROC/AUPRC (for classification) | Enhances prediction with electronic structure information |

Permeability

Biological Significance & Prediction Context Permeability refers to a compound's ability to cross biological membranes, such as the intestinal epithelium. It is often evaluated using models like Caco-2 cell lines, which predict how effectively a drug is absorbed after oral administration [3]. Interactions with efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) are also critical, as they can actively transport drugs out of cells, limiting absorption and bioavailability [3].

Computational Prediction Protocol The prediction of permeability and transporter interactions can be integrated into a molecular docking and modeling workflow:

- Molecular Docking for P-gp Interactions:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of P-gp (or other relevant transporters) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Prepare the protein by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and optimizing hydrogen bonds using tools like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard [6] [19].

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare the ligand library using a tool like Schrödinger's LigPrep, generating likely ionization states and tautomers at physiological pH [6].

- Grid Generation and Docking: Define the binding site around the known substrate pocket of P-gp and perform molecular docking using programs such as GLIDE (Schrödinger) or AutoDock Vina [6] [20]. The docking pose and score help predict whether a compound is a likely P-gp substrate.

- Machine Learning for Caco-2 Prediction:

- Model Training: Train ML classifiers on datasets of Caco-2 permeability measurements. Models can use fingerprints, graph representations, or multimodal data to classify compounds as having high or low permeability [3] [10].

- Feature Interpretation: Leverage interpretable ML models to identify key structural fragments that contribute to high or low permeability, providing insights for medicinal chemistry [17].

Metabolic Stability

Biological Significance & Prediction Context Metabolic stability, primarily mediated by hepatic enzymes such as Cytochrome P450 (CYP), influences a drug's half-life and exposure. A compound that is metabolized too quickly may not achieve therapeutic concentrations, while one that is too stable might accumulate, leading to toxicity [3]. Predicting metabolism is therefore crucial for balancing efficacy and safety.

Computational Prediction Protocol Predicting metabolic stability involves a multi-faceted computational approach:

- CYP Inhibition Prediction: This is often treated as a classification task to predict if a compound inhibits major CYP isoforms (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6).

- Data Source: Use large, curated datasets from TDC or ChEMBL [16].

- Modeling: Apply multitask learning (MTL) frameworks, which have been shown to significantly outperform single-task baselines on CYP inhibition prediction by leveraging shared information across related tasks [18]. For instance, the QW-MTL framework achieved high predictive performance on 12 out of 13 TDC ADMET tasks, including CYP inhibition [18].

- Site of Metabolism (SOM) Prediction: Molecular docking can be used to predict how a compound fits into the active site of a CYP enzyme, identifying atoms close to the heme iron as potential sites of oxidation [3].

- Clinical Translation: Advanced algorithms can now predict the activity of key enzymes like CYP3A4 with remarkable accuracy, enabling precise dose adjustments for patients with genetic polymorphisms (e.g., slow metabolizers) and supporting personalized medicine [3].

Table 2: Key Metabolic Stability Endpoints and Computational Approaches

| Endpoint | Biological Target | Common Computational Models | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP Inhibition | CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, etc. | Multitask Learning (MTL), Graph Neural Networks [18] | Early identification of drug-drug interaction risks |

| Site of Metabolism | CYP Active Site | Molecular Docking, Reactivity Models | Guide structural modification to block labile sites |

| Intrinsic Clearance | Hepatic Enzymes | Quantitative Structure-Metabolism Relationship (QSMR) Models | Prioritize compounds with desirable half-life |

Toxicity

Biological Significance & Prediction Context Toxicity remains a pivotal consideration in evaluating adverse effects and overall human safety, and it is a major cause of drug candidate failure [3]. In silico toxicity prediction aims to identify various adverse outcomes, including hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and mutagenicity (e.g., Ames toxicity), early in the discovery process.

Computational Prediction Protocol Toxicity prediction leverages diverse modeling strategies:

- Data Integration and Model Training: Utilize toxicity databases from public sources like TDC. Train classifiers (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, Deep Neural Networks) on structural and physicochemical data to predict toxic endpoints [10] [20].

- Leveraging Interpretable AI: Models like MSformer-ADMET use attention mechanisms to identify key structural fragments associated with toxicity, providing transparent insights into the structure-property relationship [17]. This "post hoc interpretability" is crucial for understanding and mitigating toxicity risks.

- In silico Toxicity Profiling Tools: Web servers such as Stoptox, pkCSM, and ADMETlab 2.0 are commonly used to forecast the drug-likeness and toxicity of ligands, predicting parameters like AMES toxicity, hepatotoxicity, and maximum tolerated dose [20]. These tools allow for rapid virtual screening of compound libraries.

Integrated Computational Workflow for ADMET Assessment

A robust ADMET assessment integrates multiple computational techniques into a cohesive workflow. The following diagram illustrates the standard protocol from initial compound screening to lead optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

This table details key resources, both computational and experimental, required for conducting the protocols described in this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category / Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Suite [6] | Commercial Software Platform | Integrated computational tool for protein & ligand prep, molecular docking (GLIDE), and dynamics (Desmond) | Predicting ligand binding poses and affinities for P-gp [6] |

| RDKit [10] [18] | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints for ML model featurization | Generating 2D and 3D molecular features for solubility Random Forest models [10] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [17] [18] [16] | Curated Public Benchmark Datasets | Provides standardized ADMET datasets for model training and fair benchmarking | Accessing curated CYP inhibition and toxicity data for multitask learning [17] [16] |

| PyRx/AutoDock Vina [20] | Open-Source Docking Software | Performing virtual screening of compound libraries against protein targets | Identifying potential inhibitors of the DprE1 enzyme in tuberculosis [20] |

| ADMETlab 2.0 / pkCSM [6] [20] | Web-based Prediction Servers | Comprehensive in silico profiling of pharmacokinetics and toxicity | Rapidly assessing drug-likeness and safety profiles of novel compounds [20] |

| Caco-2 Cell Assay [3] | In Vitro Assay (Experimental) | Experimental model for assessing intestinal permeability; used for model validation | Providing ground-truth data to train and validate ML permeability models [3] |

| Human Liver Microsomes | In Vitro Assay (Experimental) | Experimental system for evaluating metabolic stability | Measuring intrinsic clearance to benchmark computational predictions [3] |

The integration of molecular docking and machine learning into ADMET prediction represents a paradigm shift in early drug discovery. By applying the detailed protocols for solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and toxicity outlined in this application note, researchers can construct robust in silico screening pipelines. The use of standardized benchmarks [16], advanced model architectures like Transformers [17] and MTL frameworks [18], and interpretable AI [17] collectively enables more accurate and efficient prioritization of lead compounds. This approach mitigates the risk of late-stage attrition due to poor pharmacokinetics or safety, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

The Synergy of Combining Binding Affinity with Pharmacokinetic Profiling

In modern drug discovery, the integration of binding affinity assessments with comprehensive pharmacokinetic (PK) profiling has emerged as a critical paradigm for predicting in vivo efficacy and improving candidate selection. While high binding affinity to a biological target was historically prioritized, many compounds with excellent in vitro activity fail in vivo due to insufficient target engagement resulting from suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties [21]. This application note delineates protocols for the synergistic combination of these two domains, contextualized within molecular docking for ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) property assessment research. We present a unified framework that enables researchers to simultaneously optimize for binding kinetics and pharmacokinetic parameters, thereby enhancing the efficiency of lead optimization and reducing attrition rates in later development stages.

The fundamental premise of this integrated approach recognizes that in vivo efficacy is governed not merely by binding affinity but by the dynamic interplay between binding kinetics (BK) and target site pharmacokinetics (TPK) [21]. A compound must not only bind tightly to its target but also achieve and maintain sufficient concentrations at the target site for an adequate duration to elicit the desired pharmacological response. This necessitates methodologies that can accurately quantify both the rate constants of binary drug-target complex formation/dissociation (kon and koff) and the temporal concentration profile of the compound at the target vicinity.

Theoretical Foundations

Binding Kinetics and In Vivo Efficacy

Traditional drug discovery has heavily emphasized equilibrium binding affinity (Ki, IC50) measured under steady-state conditions. However, it is increasingly recognized that the rate constants (kon and koff) governing the association and dissociation of drug-target complexes often provide better predictors of in vivo efficacy, particularly for slow-binding inhibitors [21]. The residence time (1/koff) of a drug-target complex directly influences the duration of pharmacological effect, potentially enabling lower dosing frequencies and improved therapeutic indices.

The critical relationship between binding kinetics and in vivo target occupancy can be described using the following equation for a bimolecular interaction under pseudo-first-order conditions:

Where the equilibrium dissociation constant Kd = koff/kon represents the traditional affinity measurement [22]. However, the temporal dimension of target engagement is governed by these kinetic parameters in conjunction with local drug concentrations.

Integration with Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The integration of binding kinetics with pharmacokinetic profiling establishes a quantitative framework for predicting in vivo target occupancy [21]. The percent target occupancy at any time point depends on both the binding kinetic constants (kon, koff) and the compound concentration in the target vicinity at that specific time [21]. This relationship can be modeled using the following equation for a simple bimolecular interaction:

However, this equilibrium equation must be contextualized within the dynamically changing drug concentrations at the target site, requiring more sophisticated kinetic modeling approaches.

Recent studies have demonstrated the power of this integrated approach. For instance, research on α-glucosidase inhibitors ECG and EGCG revealed that despite similar binding affinities, their maximum target occupancies varied significantly (48.9-95.3% for ECG versus 96-99.8% for EGCG) due to differences in their binding kinetic profiles and pharmacokinetic behavior across different intestinal segments [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Binding Kinetics via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Objective: To determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants for compound-target interaction.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biacore T200 SPR system or equivalent with CM5 chip

- Purified target protein (>95% purity)

- Compounds of interest dissolved in DMSO

- HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4)

- Amine coupling kit (NHS, EDC, ethanolamine)

- Regeneration solution (typically 10 mM glycine, pH 2.0-3.0)

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize the target protein on a CM5 sensor chip using standard amine coupling chemistry according to manufacturer's protocols.

- System Calibration: Prime the system with running buffer and establish a stable baseline.

- Binding Measurements: Inject a series of compound concentrations (typically spanning 0.1-10 × expected Kd) over the immobilized target surface at a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

- Data Collection: Monitor the association phase for 60-180 seconds, followed by dissociation phase for 120-300 seconds.

- Surface Regeneration: Apply a 30-second pulse of regeneration solution to remove bound compound without damaging the immobilized target.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting sensorgrams to a 1:1 binding model using the Biacore T200 evaluation software to extract kon and koff values.

- Validation: Calculate Kd from the kinetic constants (Kd = koff/kon) and compare with equilibrium measurements for internal consistency.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If mass transport limitations are suspected, repeat measurements at higher flow rates.

- For compounds with very slow off-rates, extend the dissociation phase monitoring time.

- Include reference-subtracted and buffer blank injections to correct for nonspecific binding and buffer artifacts.

Protocol 2: Establishment of Micro-Pharmacokinetics in Target Vicinity

Objective: To develop a pharmacokinetic model that characterizes compound concentration-time profiles at the target site.

Materials and Reagents:

- Animal model (typically rat or mouse)

- Compounds of interest

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- Physiological-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling software

Procedure:

- Study Design: Administer compounds to animals via relevant routes (oral, intravenous) at therapeutically relevant doses.

- Sample Collection: Collect serial blood samples and, if feasible, target tissue samples at predetermined time points.

- Bioanalysis: Quantify compound concentrations in biological matrices using validated LC-MS/MS methods.

- Data Modeling: Fit concentration-time data using compartmental or PBPK modeling approaches to extract key PK parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC, t1/2, clearance, volume of distribution).

- Target Site PK: For inaccessible targets, utilize specialized sampling techniques (microdialysis) or modeling approaches to estimate target site concentrations.

- Integration: Combine the PK parameters with in vitro binding kinetic data to predict target occupancy-time profiles.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For compounds with high protein binding, consider measuring free concentrations.

- When direct tissue sampling is impossible, utilize surrogate markers or physiologically-based modeling approaches.

Protocol 3: Integrated Target Occupancy Simulation (BK-TPK Model)

Objective: To simulate the dynamic change of target engagement over time by integrating binding kinetics (BK) and target site pharmacokinetics (TPK).

Materials and Reagents:

- Binding kinetic parameters (from Protocol 1)

- Pharmacokinetic parameters (from Protocol 2)

- Mathematical modeling software (MATLAB, R, or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Data Input: Import binding kinetic constants (kon, koff) and target site concentration-time data.

- Model Implementation: Implement the following differential equation to describe the temporal change in target occupancy: Where [RL] is the concentration of the receptor-ligand complex, [R] is the concentration of free receptor, and [L] is the time-dependent concentration of free ligand at the target site.

- Parameter Optimization: Iteratively refine model parameters to achieve best fit with experimental data.

- Simulation: Run simulations to predict target occupancy under various dosing regimens.

- Validation: Compare model predictions with experimental in vivo target occupancy measurements when available.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If model predictions deviate significantly from experimental observations, consider additional complexity (e.g., rebinding events, target turnover).

- For targets with multiple binding sites, implement appropriate allosteric or competitive binding models.

Quantitative Data Presentation

Table 1: Binding Kinetic and Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Representative α-Glucosidase Inhibitors [21]

| Parameter | ECG | EGCG | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| kon (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | 1.2 × 10⁴ | 2.8 × 10⁴ | EGCG associates ~2.3x faster |

| koff (s⁻¹) | 8.5 × 10⁻³ | 1.2 × 10⁻³ | EGCG dissociates ~7x slower |

| Kd (nM) | 708.3 | 42.9 | EGCG has ~16.5x higher affinity |

| Residence Time (min) | 19.6 | 138.9 | EGCG remains bound ~7x longer |

| Cmax at Target Site (μM) | 15.3 | 22.7 | EGCG achieves higher concentrations |

| Target Occupancy Range | 48.9-95.3% | 96-99.8% | EGCG maintains more consistent occupancy |

| Duration >70% Occupancy | 0-0.64 h | 1.5-8.9 h | EGCG provides sustained target engagement |

Table 2: ADMET Property Predictions for Optimal Drug Candidates [23] [6]

| ADMET Property | Optimal Range | Computational Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Lipinski's Rule of 5 | MW ≤ 500, LogP ≤ 5, HBA ≤ 10, HBD ≤ 5 | Druglikeness analysis |

| Water Solubility (LogS) | > -4 log mol/L | QSAR models with 2D descriptors |

| Caco-2 Permeability | > -5.15 log cm/s | Random Forest models |

| P-gp Substrate | Non-substrate | SVM with ECFP4 descriptors |

| BBB Penetration | Variable by intent | SVM with ECFP2 descriptors |

| CYP Inhibition | Minimal | Multiple machine learning models |

| hERG Inhibition | Non-inhibitor | Random Forest models |

| Hepatotoxicity | Non-toxic | Structural alert screening |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integrated BK-PK Profiling

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Kinetics | Biacore T200/8K systems, Nicoya OpenSPR | Quantify kon/koff rates | Real-time monitoring, high sensitivity |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM | Determine binding modes | Atomic-resolution complex structures |

| Molecular Docking | Glide, AutoDock Vina, GOLD | Predict binding poses and affinity | Flexible docking, scoring functions |

| ADMET Prediction | ADMETlab 2.0, SwissADME | Predict pharmacokinetic properties | QSAR models, large datasets |

| MD Simulation | Desmond, GROMACS, AMBER | Refine docked poses, assess stability | OPLS force field, explicit solvation |

| PK Modeling | GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim | Predict in vivo concentration profiles | PBPK modeling, population variability |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated BK-PK Profiling Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of combining computational predictions with experimental measurements to optimize compounds based on both binding kinetics and pharmacokinetic properties.

Diagram 2: Synergy Between Binding Kinetics and Pharmacokinetics. This conceptual model illustrates how parameters from both binding kinetics and pharmacokinetics domains synergize to enable accurate prediction of target occupancy and in vivo efficacy.

Applications in Drug Discovery

The integration of binding affinity with pharmacokinetic profiling finds particular utility in several key areas of drug discovery:

Lead Optimization

During lead optimization, the BK-TPK model enables rational selection of compounds with optimal binding kinetic profiles matched to their pharmacokinetic behavior. For instance, a compound with moderate affinity but slow off-rate may demonstrate superior in vivo efficacy compared to a high-affinity compound with rapid clearance, as exemplified by the comparison between EGCG and ECG in α-glucosidase inhibition [21]. This approach facilitates informed trade-off decisions between various molecular properties.

Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment

The integrated framework provides a foundation for predicting pharmacodynamic drug-drug interactions (DDIs), which occur when one drug alters the pharmacological effect of another drug in a combination regimen [24]. These interactions can be classified as synergistic, additive, or antagonistic, with synergy occurring when the combination effect is greater than additive [25]. Quantitative modeling of DDIs enables the design of optimal combination therapies, particularly in complex disease areas such as oncology, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular disorders.

Natural Product Drug Discovery

The BK-PK integration approach has proven valuable in natural product drug discovery, where promising in vitro activity often fails to translate to in vivo efficacy. Research on BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease demonstrated that virtual screening of natural product libraries, followed by integrated ADMET prediction and molecular docking, successfully identified candidates with favorable binding affinity and pharmacokinetic profiles [6]. This methodology helps prioritize natural products with a higher probability of in vivo success.

The synergistic combination of binding affinity assessment with pharmacokinetic profiling represents a transformative approach in modern drug discovery. The protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with a systematic framework for integrating these traditionally separate domains, enabling more accurate prediction of in vivo efficacy during early discovery stages. The BK-TPK model, which dynamically couples binding kinetic parameters with target site pharmacokinetics, offers a powerful tool for simulating target occupancy and optimizing compound properties.

As drug discovery continues to confront challenges with compound attrition, particularly in the transition from in vitro activity to in vivo efficacy, the integrated approach described herein promises to enhance decision-making and improve success rates. Future advancements in computational methods, including AI-enhanced docking and prediction of ADMET properties, will further strengthen this synergy, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients.

The high attrition rate of drug candidates, predominantly caused by unfavorable pharmacokinetics and toxicity, remains a significant challenge in pharmaceutical development [26]. The concept of 'drug-likeness' provides a crucial framework to address this issue early in the discovery process. Among these guidelines, Lipinski's Rule of Five (RO5) stands as a foundational principle for predicting the oral bioavailability of biologically active molecules [27] [28]. This application note details the core concepts of the Rule of Five and provides structured protocols for its practical integration into molecular docking workflows for ADMET property assessment.

Core Principles of Lipinski's Rule of Five

Formulated by Christopher A. Lipinski in 1997, the Rule of Five is a rule-of-thumb to evaluate the "drug-likeness" of a compound, determining if it possesses chemical and physical properties that would make it a likely orally active drug in humans [27]. The rule is based on the observation that most orally administered drugs are relatively small and moderately lipophilic molecules.

The "Rule of Five" derives its name from the fact that all four criteria involve multiples of five. The rule states that an orally active drug should exhibit no more than one violation of the following criteria [27] [28]:

- Table 1: The Four Criteria of Lipinski's Rule of Five

Criterion Threshold Value Rationale Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) ≤ 5 Impacts compound's ability to cross lipid membranes via passive diffusion. Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) ≤ 10 Influences solubility and permeability. Molecular Weight (MW) < 500 Daltons Smaller molecules generally have better diffusion and absorption. Partition Coefficient (log P) ≤ 5 A measure of lipophilicity; high log P can indicate poor aqueous solubility.

It is critical to recognize that the RO5 specifically predicts oral bioavailability and does not assess a compound's pharmacological activity [27]. Furthermore, the rule operates under the assumption of passive diffusion as the primary cellular entry mechanism and has notable exceptions, including natural products (e.g., macrolides, peptides) and drugs that utilize active transport mechanisms [27] [26].

Integration with Molecular Docking and ADMET Assessment

In modern drug discovery, Lipinski's Rule of Five is not used in isolation but is integrated into a broader computational workflow that includes molecular docking and ADMET prediction. This multi-stage process helps prioritize lead compounds that are not only potent but also have a high probability of favorable pharmacokinetic profiles.

- Diagram 1: Integrated Drug Discovery Workflow

This integrated approach was exemplified in a study screening over 80,617 natural compounds from the ZINC database. The initial RO5 filtering step narrowed the library down to 1,200 compounds, which were then subjected to molecular docking against the BACE1 target, followed by ADMET prediction and molecular dynamics simulations, ultimately identifying a high-potency ligand (L2) with promising properties [6].

Protocol: Virtual Screening with RO5 Integration

Aim: To identify potential drug candidates from a large compound library by sequentially applying RO5 filtering, molecular docking, and ADMET prediction.

Materials:

- Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Item Function / Description Example Tools & Databases Compound Database Source of small molecules for screening. ZINC [6], ChEMBL [29], PubChem [29] RO5 Prediction Tool Calculates molecular properties and checks RO5 compliance. ChemAxon [28], SwissADME [26], MOE LigPrep [6] Molecular Docking Software Predicts binding pose and affinity of ligands to a protein target. AutoDock Vina [29], Glide (Schrödinger) [30] [6], MOE [30] ADMET Prediction Server Predicts pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties in silico. admetSAR [31] [6], SwissADME [26] [6] Protein Data Bank Repository for 3D structural data of proteins. RCSB PDB [30] [6]

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Download or assemble a library of small molecules in an appropriate format (e.g., SDF, SMILES) from databases like ZINC or ChEMBL.

- RO5 Filtering:

- Ligand and Protein Preparation:

- Ligands: Prepare the filtered ligand set using a tool like MOE LigPrep or OpenBabel. This involves energy minimization, generating 3D structures, and producing possible tautomers and ionization states at physiological pH (e.g., 7.4) [6] [29].

- Protein: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target protein from the RCSB PDB. Prepare the protein by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and optimizing hydrogen bonds followed by energy minimization using a force field like OPLS 2005 [6].

- Molecular Docking:

- Validation: Validate the docking protocol by re-docking a known co-crystallized ligand. A root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of ≤ 2 Å between the docked and original pose is generally acceptable [6].

- Docking Run: Perform molecular docking of the prepared ligand library into the active site of the prepared protein. Employ a multi-level approach (e.g., High-Throughput Virtual Screening followed by Standard Precision and Extra Precision docking in Glide) to progressively refine and score the ligands based on their binding affinity (G-Score) [6].

- ADMET Profiling: Subject the top-ranked docked compounds (e.g., 50-100 ligands) to in silico ADMET prediction using platforms like admetSAR or SwissADME. Key properties to assess include human intestinal absorption, blood-brain barrier permeability, CYP450 enzyme inhibition, and hERG toxicity [31] [6].

Advanced Extensions and AI-Driven Paradigms

While Lipinski's RO5 is a foundational filter, the field of drug-likeness assessment has evolved significantly.

- Refined Rules and Scoring Functions: Several extensions to the RO5 have been proposed to improve predictive accuracy. These include Veber's Rule (which emphasizes polar surface area ≤ 140 Ų and rotatable bonds ≤ 10) and the Ghose Filter [27]. Furthermore, quantitative scoring functions like the Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) integrate multiple physicochemical properties into a continuous, weighted index, providing a more nuanced assessment than binary rules [31] [26].

- The "Rule of Three" for Fragments: For fragment-based lead discovery, a stricter "Rule of Three" (RO3) is often applied to define "lead-like" compounds, ensuring sufficient space for optimization while maintaining drug-like properties [27].

AI-Powered ADMET Prediction: Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) are revolutionizing ADMET prediction. Models using graph neural networks (GNNs) and multitask learning can decipher complex structure-property relationships from large-scale datasets, offering superior accuracy and generalizability compared to traditional methods [32] [3]. These AI-driven approaches help mitigate late-stage attrition by providing more reliable early-stage pharmacokinetic and safety profiles [3].

Diagram 2: Evolution of Drug-Likeness Assessment

Comprehensive scoring functions like the ADMET-score have been developed to integrate predictions from 18 different ADMET endpoints (e.g., Ames mutagenicity, Caco-2 permeability, CYP inhibition, hERG liability) into a single, comprehensive index, providing a holistic view of a compound's drug-likeness [31].

Protocol: Calculating a Comprehensive ADMET-Score

Aim: To evaluate the overall drug-likeness of a compound using a multi-parameter ADMET-score [31].

Procedure:

- Select ADMET Endpoints: Identify a suite of critical ADMET properties for evaluation. The original ADMET-score incorporated 18 endpoints, including Ames mutagenicity, Caco-2 permeability, CYP450 inhibition for major isoforms (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4), hERG inhibition, human intestinal absorption, and P-glycoprotein inhibition/substrate status [31].

- Obtain Predictions: Use a comprehensive prediction server like admetSAR 2.0 to compute the selected ADMET properties for the compound(s) of interest. The server provides binary (Yes/No) or categorical predictions for these endpoints based on its underlying machine learning models [31].

- Calculate the Score: The ADMET-score is a weighted sum of the individual property predictions. The weight for each property is determined by three parameters:

- The predictive accuracy of the model for that endpoint.

- The importance of the endpoint in the overall pharmacokinetic process.

- A usefulness index [31].

- Interpret Results: A higher composite ADMET-score indicates a more favorable overall drug-likeness profile. This score can be used to rank-order candidate molecules and has been shown to differentiate significantly between FDA-approved drugs, general bioactive compounds, and withdrawn drugs [31].

Lipinski's Rule of Five remains an indispensable first-pass filter in modern computational drug discovery, providing a rapid and effective means to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of oral bioavailability. However, its true power is realized when integrated into a holistic workflow that combines molecular docking for potency assessment with advanced, often AI-driven, ADMET prediction tools for comprehensive pharmacokinetic and safety profiling. This multi-faceted approach, leveraging both foundational rules and next-generation predictive models, significantly de-risks the drug discovery pipeline and enhances the likelihood of identifying viable clinical candidates.

Practical Workflows: From Docking Screens to ADMET Prediction

In modern computational drug discovery, integrating molecular docking with Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction has become a fundamental strategy for identifying viable therapeutic candidates. This integrated approach enables researchers to evaluate not only the binding affinity of a compound toward its biological target but also its pharmacokinetic and safety profiles early in the discovery pipeline. The systematic workflow outlined in this application note provides a standardized protocol for progressing from target protein preparation to comprehensive ADMET analysis, framed within the broader context of molecular docking for ADMET property assessment research. This methodology significantly reduces the high attrition rates traditionally associated with unfavorable pharmacokinetics and toxicity, which are major causes of failure in drug development [10] [33].

The complete pathway from target preparation to ADMET analysis constitutes a multi-stage in silico pipeline. Figure 1 below visualizes this integrated workflow, highlighting the sequential stages and key decision points.

Figure 1. Integrated Workflow from Target Preparation to ADMET Analysis. This diagram outlines the sequential stages of the computational drug discovery pipeline, from initial target identification through to the selection of lead candidates for experimental validation.

Experimental Protocols

Target Protein Preparation

Objective: To obtain and refine the three-dimensional structure of the target protein for molecular docking simulations.

Detailed Methodology:

Protein Structure Retrieval: Download the crystal structure of the target protein from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prioritize structures with:

Protein Structure Preprocessing: Using software such as Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard:

Energy Minimization: Perform restrained minimization on the protein structure using a force field (e.g., OPLS4 or OPLS 2005) to relieve steric clashes and correct geometric distortions, typically until the average root mean square deviation (RMSD) of heavy atoms reaches a threshold of 0.30 Å [6] [34]. This step ensures a stable and energetically favorable starting conformation for docking.

Ligand Library Preparation

Objective: To generate a library of chemically diverse, energetically optimized, and biologically relevant small molecules for docking screens.

Detailed Methodology:

Library Sourcing: Acquire compound structures from publicly available databases such as:

Initial Filtering: Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five (Ro5) as an initial filter to prioritize compounds with drug-like properties. The criteria are:

Ligand Preprocessing: Using tools like Schrödinger's LigPrep:

Molecular Docking and Validation

Objective: To predict the binding pose and affinity of ligands within the target's active site and validate the docking protocol for reliability.

Detailed Methodology:

Docking Protocol Validation (Critical Step):

- Extract the native co-crystallized ligand from the PDB structure.

- Re-dock the ligand back into the prepared binding site using the same parameters intended for the virtual screen.

- Calculate the RMSD between the docked pose and the original crystallographic pose. An RMSD value ≤ 2.0 Å indicates a reliable and validated docking protocol [6].

Receptor Grid Generation: Define the docking search space by generating a grid box centered on the active site. The center is typically based on the centroid of the co-crystallized ligand, with a box size large enough to accommodate the ligands in the library (e.g., a 20 Å radius) [35].

High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS): Dock the entire prepared ligand library using a fast, less precise method (HTVS mode in Glide) to rapidly filter out weak binders.

Standard Precision (SP) and Extra Precision (XP) Docking: Subject the top-ranked hits from HTVS to successively more rigorous docking levels (SP, then XP). XP docking is particularly effective for minimizing false positives and refining poses by employing a more detailed scoring function [6] [35]. The output is a ranked list of compounds based on their docking scores (expressed in kcal/mol).

ADMET Prediction and Profiling

Objective: To computationally assess the pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and toxicity profiles of the top-ranked docked compounds.

Detailed Methodology:

Platform Selection: Utilize comprehensive web-based platforms for efficient ADMET profiling. Key platforms include:

- admetSAR3.0: Hosts over 370,000 experimental data points and provides predictions for 119 ADMET and environmental toxicity endpoints using a multi-task graph neural network framework [33].

- ADMETlab 2.0: Offers systematic evaluation based on a large database, including drug-likeness analysis and similarity searching [23].

- SwissADME: A popular tool for predicting physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness [6].

Key Endpoint Prediction: Input the chemical structures (e.g., as SMILES strings) of the candidate compounds to predict critical properties summarized in Table 1.

Data Integration and Analysis: Cross-reference the ADMET predictions with the docking scores. A promising candidate should possess not only a strong binding affinity but also a favorable ADMET profile, such as high gastrointestinal absorption and low toxicity risks.

Table 1. Essential ADMET Endpoints for Candidate Evaluation

| Category | Property | Desired Profile | Research Tool Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) | High | ADMETlab 2.0 [23] |

| Caco-2 Permeability | High | admetSAR3.0 [33] | |

| P-glycoprotein Substrate | Non-substrate | ADMETlab 2.0 [23] | |

| Distribution | Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Penetration | Target-dependent | admetSAR3.0, ADMETlab 2.0 [23] [33] |

| Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | Moderate to low | ADMETlab 2.0 [23] | |

| Metabolism | Cytochrome P450 Inhibition (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6) | Non-inhibitor | admetSAR3.0, ADMETlab 2.0 [23] [33] |

| Toxicity | hERG Inhibition | Non-inhibitor (to avoid cardiotoxicity) | ADMETlab 2.0 [23] |

| Ames Test | Non-mutagen | admetSAR3.0, ADMETlab 2.0 [23] [33] | |

| Hepatotoxicity (e.g., DILI) | Low risk | ADMETlab 2.0 [23] | |

| Drug-likeness | Lipinski's Rule of Five | ≤ 1 violation | SwissADME, ADMETlab 2.0 [6] [23] |

Advanced Simulations and Validation

Objective: To validate the stability of the protein-ligand complex and estimate binding free energy using advanced computational techniques.

Detailed Methodology:

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- Solvate the top-ranked protein-ligand complex in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water model).

- Neutralize the system by adding counterions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻).

- Run simulations for a sufficient timescale (typically 100 ns or more) using software like Desmond to analyze the stability of the complex under dynamic conditions [6] [36].

- Analyze trajectories using metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and the number of hydrogen bonds to assess conformational stability and interaction persistence.

Binding Free Energy Calculation: Employ methods such as Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area Solvation (MM-GBSA) to compute the binding free energy of the complex, providing a more rigorous assessment of binding affinity than docking scores alone [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2 catalogs essential software, databases, and web servers that form the core toolkit for executing the integrated workflow.

Table 2. Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB | Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | http://www.rcsb.org [6] |

| Schrödinger Suite | Software Platform | Integrated suite for protein preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), ligand preparation (LigPrep), molecular docking (Glide), and MD simulations (Desmond). | Commercial [6] [34] |

| ZINC15 | Database | Publicly available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | https://zinc15.docking.org [6] [35] |

| PubChem | Database | Database of chemical molecules and their activities against biological assays. | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [34] |

| admetSAR3.0 | Web Server | Comprehensive platform for predicting ADMET properties, including environmental and cosmetic risk assessments. | http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar3/ [33] |

| ADMETlab 2.0 | Web Server | Web-based tool for systematic ADMET evaluation and drug-likeness analysis. | https://admet.scbdd.com [23] |

| SwissADME | Web Server | Tool for computing physicochemical descriptors, predicting pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness. | http://www.swissadme.ch [6] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, used for descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation in ML-based ADMET models. | https://www.rdkit.org [38] |

| Gaussian 09W | Software | Program for quantum chemical calculations, including Density Functional Theory (DFT) for analyzing electronic properties. | Commercial [35] |

The step-by-step integrated workflow presented here—from rigorous target and ligand preparation through molecular docking to comprehensive ADMET profiling—provides a robust framework for accelerating early-stage drug discovery. By incorporating machine learning-powered ADMET predictions [10] [33] and validating docking poses with molecular dynamics simulations [6] [36], researchers can prioritize lead candidates with a higher probability of success in subsequent preclinical studies. This protocol emphasizes the critical importance of validating each computational step and encourages the use of open-access tools alongside commercial software to ensure a thorough and critical evaluation of potential drug candidates.

The integration of computational methodologies has revolutionized the early phases of drug discovery, enabling researchers to prioritize promising candidates with desired pharmacokinetic and safety profiles before committing to costly synthetic efforts and experimental testing [39] [40]. Molecular docking predicts how small molecules interact with biological targets, while ADMET prediction platforms assess critical pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties in silico [32] [6]. This application note provides a detailed overview of two widely used docking software packages—Glide and AutoDock Vina—and three key ADMET platforms—SwissADME, QikProp, and ProTox-III. Framed within the context of molecular docking for ADMET property assessment research, this guide offers structured comparisons and actionable protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Docking Software

Molecular docking serves as a cornerstone of structure-based drug design, allowing for the prediction of ligand binding geometry and affinity towards a target of interest, often accelerating virtual screening campaigns [41].

Comparative Analysis of Docking Software

Table 1: Key Features of Glide and AutoDock Vina

| Feature | Glide (Schrödinger) | AutoDock Vina |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | High-accuracy virtual screening & lead optimization [6] | High-throughput screening, automated pipelines [41] |

| Docking Algorithms | High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS), Standard Precision (SP), Extra Precision (XP) [6] | Hybrid global/local search optimization, empirical scoring function |

| Scoring Function | Proprietary, force field-based (OPLS) with XP for fewer false positives [6] | Empirical, knowledge-based scoring function [41] |

| Input File Requirements | Prepared protein structure (e.g., .mae), ligand file (.sdf, .mae) [6] | Receptor and ligand in PDBQT format [41] |

| Typical Workflow Integration | Integrated Schrödinger suite (LigPrep, Protein Prep Wizard, Desmond MD) [6] | Standalone; often scripted with Open Babel, fpocket, etc. [41] |

| Computational Speed | Slower, especially XP mode; resource-intensive | Faster; suitable for large compound libraries [41] |

| License & Cost | Commercial, proprietary | Free, open-source [41] |

| Key Strength | High precision and accurate pose prediction, advanced scoring [6] | Speed, ease of use, and seamless integration into automated workflows [41] |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol for Glide Docking (as applied to BACE1 Inhibitors)

This protocol is adapted from a study identifying BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease [6].

System Setup and Software Installation

- Access the Schrödinger suite. The Maestro interface provides the integrated environment for this workflow.

- Ensure modules including LigPrep, Protein Preparation Wizard, Glide, and Desmond are available and licensed [6].

Protein Preparation

- Retrieve Structure: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., BACE1, PDB ID: 6EJ3) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank [6].

- Preprocess: Using the Protein Preparation Wizard, add missing hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and correct for missing side chains.

- Optimize and Minimize: Remove original water molecules, generate protonation states at biological pH, and perform restrained energy minimization using the OPLS4 force field until an RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) of 0.3 Å is achieved [6].

Ligand Preparation

- Input Library: Import a library of ligand structures (e.g., in .sdf format). The study by Kaur et al. began with 80,617 natural compounds from ZINC, filtered to 1,200 based on drug-likeness rules [6].

- Process with LigPrep: Using the LigPrep module, generate 3D structures, assign correct chiralities, generate possible tautomers, and perform energy minimization using the OPLS4 force field [6].

Receptor Grid Generation