In Silico Pharmacokinetic Prediction: Integrating AI, PBPK, and Machine Learning for Modern Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles and advanced applications of in silico pharmacokinetic (PK) prediction for researchers and drug development professionals.

In Silico Pharmacokinetic Prediction: Integrating AI, PBPK, and Machine Learning for Modern Drug Development

Abstract

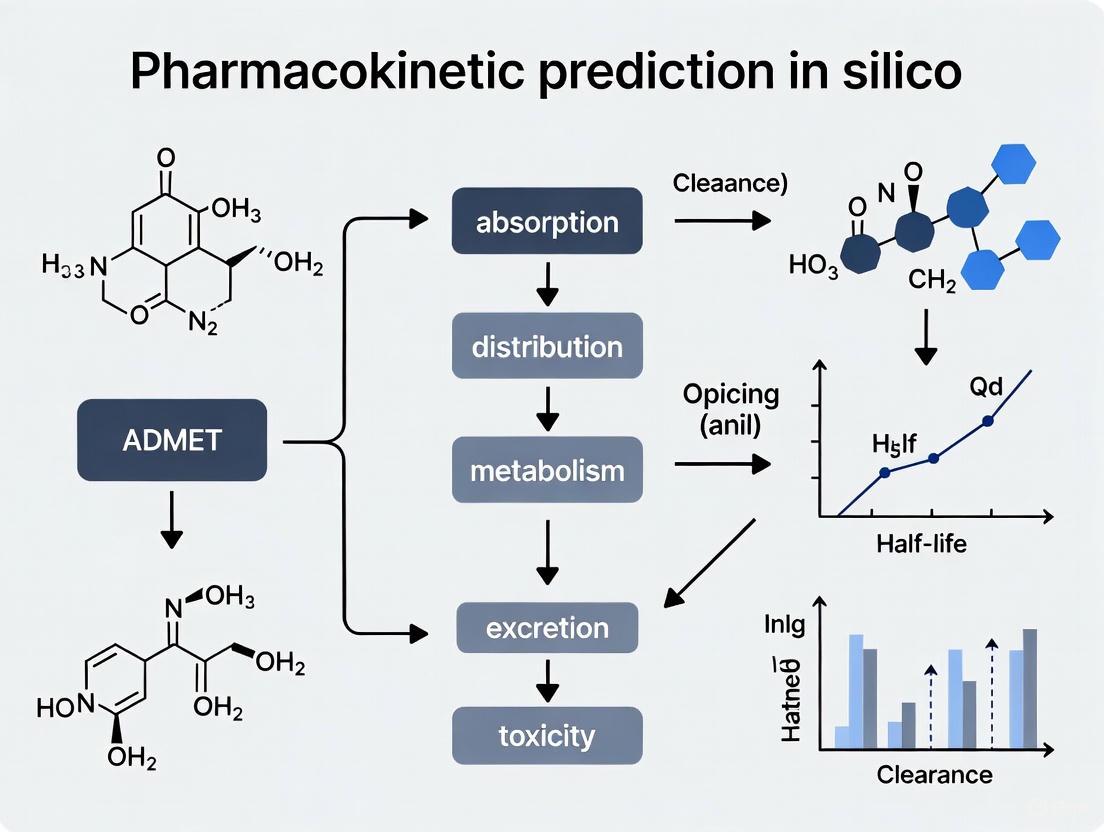

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles and advanced applications of in silico pharmacokinetic (PK) prediction for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and its integration with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). The scope spans from core methodologies like quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) and PBPK modeling to their practical application in predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties. It addresses key challenges such as model complexity, parameter uncertainty, and computational efficiency, while also covering validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different modeling approaches. The content highlights how these in silico tools enable more efficient, cost-effective, and ethical drug development from discovery through clinical stages.

The Core Principles of In Silico Pharmacokinetics: From Physiological Concepts to AI Integration

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is a mechanistic, mathematical technique for predicting the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of chemical substances in humans and other animal species [1]. Unlike classical compartmental pharmacokinetic models, which use empirical fitting to plasma concentration data, PBPK models incorporate prior knowledge of human or animal physiology and the physicochemical properties of a drug to achieve a mechanistic representation within biological systems [2] [3]. This allows for a priori simulation of drug concentration-time profiles not only in plasma but also at specific sites of action, which are often difficult or impossible to measure experimentally [2].

The fundamental principle of PBPK modeling, introduced as early as the 1920s and formally described by Teorell in 1937, is to divide the body into physiologically relevant compartments corresponding to actual organs and tissues [4] [5] [6]. These compartments are interconnected by the circulatory system and characterized by physiological parameters such as blood-flow rates, tissue volumes, and permeability, creating an integrated system that mirrors the anatomy and physiology of the organism [2] [1] [3]. PBPK modeling represents a "middle-out" approach, combining elements of both data-driven "top-down" and mechanistic "bottom-up" strategies, and has become an indispensable tool in drug development, regulatory review, and health risk assessment [6] [7].

Core Principles and Model Structure

Fundamental Concepts and Historical Context

PBPK modeling is grounded in the principle that the mammalian body can be represented as an interconnected system of physiological compartments. A whole-body PBPK model explicitly represents organs most relevant to ADME processes, typically including heart, lung, brain, stomach, gut, liver, kidney, adipose tissue, muscle, and skin [2] [4]. These tissues are linked by arterial and venous blood pools, with each organ characterized by its specific blood-flow rate, volume, and partition coefficients [2].

The development of PBPK modeling began with seminal work by Bischoff, Brown, and Dedrick in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by influential publications on styrene and methylene chloride in the 1980s that expanded its application in toxicology and risk assessment [3]. The approach has flourished in recent decades, facilitated by increased computational power and the development of specialized software platforms, with now over 700 publications related to PBPK modeling across industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and environmental pollutants [3].

Mathematical Foundation

PBPK models operate on mass balance principles, where the rate of change of drug quantity in each compartment is described by differential equations that account for all transport and metabolic processes [4] [3]. For a generic tissue compartment i, the basic mass balance equation under perfusion-limited kinetics is:

dQ_i/dt = F_i * (C_art - Q_i/(P_i * V_i)) [1]

Where:

dQ_i/dt= rate of change of drug quantity in compartmentiF_i= blood flow rate to compartmentiC_art= drug concentration in arterial bloodP_i= tissue-to-blood partition coefficientV_i= volume of compartmenti

The liver compartment typically has a more complex equation that accounts for input from the hepatic artery and portal vein (from intestinal and splenic circulation) [1]:

dQ_l/dt = F_a * C_art + F_g * (Q_g/(P_g * V_g)) + F_pn * (Q_pn/(P_pn * V_pn)) - (F_a + F_g + F_pn) * (Q_l/(P_l * V_l))

These differential equations for all compartments form a system that is solved numerically to simulate concentration-time profiles throughout the body [4].

Diagram: Structure of a Whole-Body PBPK Model

The following diagram illustrates the compartmental structure and circulatory connections of a typical whole-body PBPK model:

Diagram Title: Whole-Body PBPK Model Structure

This diagram shows the fundamental structure where organs are connected in parallel between arterial and venous blood pools, with the liver receiving additional input from the gastrointestinal tract via the portal vein [4] [1]. The lung compartment closes the circulatory loop.

Critical PBPK Model Parameters

PBPK model parameters can be categorized into three main groups: organism-specific physiological parameters, drug-specific properties, and administration protocol specifications [2].

Physiological Parameters

Physiological parameters describe the anatomy and physiology of the organism being modeled and are typically obtained from established literature compilations [2] [3]. These parameters are largely independent of the specific drug being studied.

Table 1: Key Physiological Parameters in PBPK Models

| Parameter Type | Examples | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Organ volumes | Liver volume, kidney volume, brain volume | Biological data compilations [3] |

| Blood flow rates | Cardiac output, hepatic blood flow, renal blood flow | Physiological literature [3] |

| Tissue composition | Water, lipid, protein content in various tissues | Experimental measurements [4] |

| Expression levels | Enzyme and transporter expression in different tissues | Proteomic/transcriptomic data [2] |

| Biometric data | Body weight, height, age, organ size relationships | Population databases [5] |

For special populations (e.g., pediatric, geriatric, or diseased populations), these physiological parameters are adjusted to reflect population-specific anatomical and physiological differences [2] [6].

Drug-Specific Parameters

Drug-specific parameters characterize the physicochemical and biological properties of the compound being modeled and can be further divided into two subcategories.

Table 2: Essential Drug-Specific Parameters for PBPK Modeling

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Determination Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties (independent of organism) | Molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), acid dissociation constant (pKa), solubility | Experimental measurement or in silico prediction [2] [8] |

| Drug-biological system interaction properties | Fraction unbound in plasma (fu), blood-to-plasma ratio (B/P), tissue-plasma partition coefficients, membrane permeability, metabolic parameters (Km, Vmax), transport parameters | In vitro experiments, in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE), quantitative structure-property relationships [2] [9] |

For tissue distribution, partition coefficients are frequently calculated using established distribution models that predict the equilibrium distribution between plasma and tissues based on drug physicochemical properties and tissue composition [2]. Passive processes like membrane permeation can often be predicted from fundamental properties, while active processes (metabolism, transport) typically require specific experimental data [2] [4].

The PBPK Modeling Workflow

Model Building Process

Building a PBPK model follows a systematic workflow that integrates information from multiple sources. The process can be summarized in several key stages:

Problem Identification and Literature Evaluation: Define the purpose of the model and conduct a thorough review of existing literature on the drug and relevant physiology [3].

Parameter Acquisition and Estimation: Gather the three essential parameter sets: physiological parameters (ventilation rates, cardiac output, organ volumes), thermodynamic parameters (tissue partition coefficients), and biochemical parameters (Km, Vmax for metabolism) [3].

Model Implementation: Construct the mathematical model using mass balance differential equations for each compartment, representing the interconnected physiological system [3].

Model Verification and Validation: Compare simulations with experimental pharmacokinetic data to assess model performance, then validate with additional independent data sets [3] [5].

Model Application: Use the validated model for its intended application, such as predicting exposure in special populations, evaluating drug-drug interactions, or supporting regulatory submissions [2] [9].

A recent example demonstrating this workflow is the development of a PBPK model for fexofenadine, which commenced with a comprehensive literature review to collect pertinent pharmacokinetic data, followed by model construction using PK-Sim software, and subsequent extrapolation to special populations including chronic kidney disease patients and pediatrics [5].

Diagram: PBPK Model Development Workflow

The following flowchart illustrates the systematic approach to PBPK model development:

Diagram Title: PBPK Model Development Workflow

This workflow highlights the iterative nature of PBPK model development, where discrepancies between simulations and experimental data may require parameter refinement or structural model adjustments [2] [3].

Key Applications in Drug Development

PBPK modeling has become an integral tool throughout the drug development continuum, with applications spanning from early discovery through clinical development and regulatory submission.

Table 3: Key Applications of PBPK Modeling in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Impact and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| First-in-Human (FIH) Predictions | Prediction of human pharmacokinetics from preclinical data, dose selection for first clinical trials [9] | Reduces uncertainty in initial human studies, helps establish safe starting doses [9] |

| Special Population Extrapolations | Pediatric extrapolations, patients with hepatic or renal impairment, elderly populations [2] [6] | Supports dose adjustments for populations where clinical trials are ethically or practically challenging [5] [6] |

| Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Assessment | Evaluation of enzyme inhibition/induction, transporter-mediated interactions [2] [7] | Identifies and quantifies DDI risks, informs contraindications and dose adjustments [2] |

| Formulation Development | Evaluation of different formulations, food effect predictions, absorption assessment [9] [6] | Guides formulation strategy to optimize bioavailability and product performance [6] |

| Regulatory Submissions | Support for labeling claims, pediatric study plans, DDI assessments [6] [7] | Provides mechanistic evidence to regulatory agencies, increasingly expected in submissions [6] |

According to a systematic review of PBPK publications between 2008-2014, the most common applications were drug-drug interaction studies (28%), interindividual variability and general clinical pharmacokinetics predictions (23%), absorption kinetics (12%), and age-related changes in pharmacokinetics (10%) [7]. For FDA regulatory filings, models were primarily used for DDI predictions (60%), pediatrics (21%), and absorption predictions (6%) [7].

Research Tools and Software Platforms

The implementation of complex PBPK models has been greatly facilitated by the development of specialized software platforms that integrate physiological databases and implement PBPK modeling approaches [2]. These tools have made PBPK modeling more accessible to researchers without requiring extensive programming or mathematical expertise.

Table 4: Key Software Platforms for PBPK Modeling

| Software Platform | Vendor/Developer | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GastroPlus | Simulations Plus | Comprehensive PBPK platform with absorption and dissolution modeling; offers training courses including "Introduction to PBPK Modeling" [2] [10] |

| Simcyp Simulator | Certara | Population-based PBPK platform with extensive library of virtual populations; used for DDI and special population modeling [2] [8] |

| PK-Sim | Bayer Technology Services/Open Systems Pharmacology | Whole-body PBPK modeling integrated with MoBi for multiscale systems pharmacology; used in recent fexofenadine PBPK study [2] [4] [5] |

| ADMET Predictor | Simulations Plus | QSAR-based property prediction software that can be used in conjunction with PBPK platforms to estimate parameters for new chemical entities [8] |

These platforms typically include extensive physiological databases covering multiple species, populations, and age groups, which are combined with compound-specific information to parameterize whole-body PBPK models [2]. Many also incorporate systems for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) to predict clearance from enzyme and transporter kinetics [9].

Experimental Protocols for PBPK Modeling

Parameter Estimation Protocol

A critical step in PBPK model development is the acquisition and estimation of necessary parameters. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach:

Physiological Parameter Collection:

- Source species-specific physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows) from established databases such as those provided by the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) [3].

- For special populations, collect age-dependent or disease-specific physiological changes from literature (e.g., reduced renal function in chronic kidney disease) [5] [6].

Drug-Specific Parameter Determination:

- Measure or obtain from literature fundamental physicochemical properties: molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), acid dissociation constants (pKa), and solubility [2] [8].

- Determine plasma protein binding (fraction unbound) using equilibrium dialysis or ultrafiltration [9].

- Calculate tissue:plasma partition coefficients using established distribution models (e.g., Poulin and Rodgers, Berezhkovskiy) implemented in PBPK software [2].

- For metabolism parameters, conduct in vitro metabolism studies using human liver microsomes, hepatocytes, or recombinant enzymes to obtain Km and Vmax values, then scale using IVIVE [9].

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with the greatest influence on key model outputs (e.g., AUC, Cmax) [6].

- Prioritize experimental verification of high-sensitivity parameters.

Model Verification and Validation Protocol

Establishing model credibility requires rigorous verification and validation:

Model Verification:

- Compare model predictions with observed plasma concentration-time data from clinical studies [3] [5].

- Use visual predictive checks to assess overlap between simulated and observed concentration-time profiles [5].

- Calculate quantitative metrics such as observed-to-predicted ratios (RObs/Pre), average fold error (AFE), and absolute average fold error (AAFE) with a common acceptance criterion of within two-fold error [5].

External Validation:

PBPK modeling represents a fundamental advancement in pharmacokinetic prediction, shifting from empirical descriptive approaches to mechanistic, physiology-based frameworks. By explicitly representing the anatomical and physiological structure of the body, PBPK models provide a powerful platform for predicting drug concentrations not only in plasma but also at specific sites of action, enabling more informed decisions throughout drug discovery and development [2] [4].

The strength of PBPK modeling lies in its ability to integrate diverse data types—from in vitro assays to clinical observations—into a unified mechanistic framework that supports extrapolation to novel clinical scenarios [2] [6]. This capability is particularly valuable for addressing challenges in special populations where clinical trials may be ethically or practically challenging, such as pediatric patients, pregnant women, or individuals with organ impairment [5] [6].

As PBPK modeling continues to evolve, it is increasingly integrated with pharmacodynamic models to form comprehensive PBPK/PD models that can predict both drug exposure and response [2]. Furthermore, the incorporation of population variability and Bayesian statistical methods enhances the utility of PBPK models for personalized medicine approaches, moving closer to the goal of delivering the "right drug at the right dose" for individual patients [6] [7]. With ongoing advancements in computational power, physiological knowledge, and biochemical characterization of drugs, PBPK modeling is positioned to play an increasingly central role in silico pharmacokinetic research and model-informed drug development.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) is the study of how the body interacts with administered substances for the entire duration of exposure, focusing on the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [11]. These four parameters fundamentally influence the drug levels and kinetics of drug exposure to tissues, thereby determining the compound's pharmacological activity and performance as a drug [12]. In the context of modern drug development, understanding ADME is critical for predicting the systemic exposure of a drug over time, which directly informs dosage regimen design to ensure that the majority of patients achieve a therapeutic exposure range without intolerable side effects [13].

The integration of in silico (computational) research methods has revolutionized the evaluation of ADME properties early in the drug discovery pipeline. These approaches offer a compelling advantage by eliminating the need for physical samples and laboratory facilities, providing rapid and cost-effective alternatives to expensive and time-consuming experimental testing [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, pharmacokinetic prediction models are indispensable tools for prioritizing lead compounds, forecasting human pharmacokinetics, and reducing late-stage attrition due to suboptimal drug-like properties.

The ADME Process: A Detailed Technical Examination

Absorption

Definition and Importance: Absorption is the process that brings a drug from its site of administration into the systemic circulation [11]. This stage critically determines the drug's bioavailability, which is defined as the fraction of the administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation in an active form [15]. The rate and extent of absorption directly affect the speed and concentration at which a drug arrives at its desired location of effect [11].

Key Mechanisms and Factors: The absorption process involves liberation, the process by which the drug is released from its pharmaceutical dosage form, which is especially critical for oral medications [11]. A primary consideration for orally administered drugs is the first-pass effect, where the drug is metabolized in the liver or gut wall before it reaches the systemic circulation, significantly reducing its bioavailability [11] [16]. Factors influencing drug absorption include:

- Route of administration (e.g., oral, intravenous, transdermal) [11] [16]

- Chemical properties of the drug (e.g., solubility, stability) [15]

- Formulation characteristics [13]

- Drug-food and drug-drug interactions [15] [13]

- Patient-specific factors such as gastric pH and emptying time [16]

Routes of Administration and Bioavailability:

| Route of Administration | Bioavailability | Key Characteristics | First-Pass Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous (IV) | 100% [11] [15] | Direct delivery into systemic circulation; rapid onset [11] | Avoided [16] |

| Oral (PO) | Variable; often <100% [11] [15] | Convenient; subject to GI environment and hepatic metabolism [11] [16] | Yes [11] [16] |

| Intramuscular (IM) | High | Absorption depends on blood flow to the muscle [11] | Avoided [16] |

| Subcutaneous (SC) | High | Slower absorption than IM [16] | Avoided [16] |

| Transdermal | Variable | Slow, steady drug delivery; bypasses liver [16] | Avoided [16] |

| Inhalation | Variable | Rapid delivery via lungs; large surface area for absorption [16] | Avoided [16] |

Distribution

Definition and Importance: After a drug is absorbed, it is distributed throughout the body into various tissues and organs [15]. Distribution describes the reversible transfer of a drug between different compartments and is crucial because it affects how much drug ends up at the active sites, thereby influencing both efficacy and toxicity [15] [12].

Key Parameters and Concepts:

- Volume of Distribution (Vd): A fundamental PK parameter defined as the amount of drug in the body divided by the plasma drug concentration [11]. It is a theoretical volume that describes the dissemination of a drug throughout the body's compartments. A low Vd indicates the drug is largely confined to the plasma, while a high Vd suggests extensive distribution into tissues [11].

- Protein Binding: Drugs can bind to plasma proteins (e.g., albumin), rendering them pharmacologically inactive while bound [13]. Only the free, unbound drug can act at receptor sites, be distributed into tissues, or be eliminated [11] [13]. Changes in protein binding (e.g., due to disease or drug interactions) can significantly alter the drug's effect and potential for toxicity [11].

- Barriers to Distribution: Natural barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier, can prevent certain drugs from reaching their target sites. Drugs with characteristics like high lipophilicity, small size, and low molecular weight are better able to cross this barrier [15].

Diagram 1: Drug Distribution and Protein Binding. This graph illustrates the equilibrium between free and protein-bound drug in plasma, and the movement of free drug to tissue compartments and receptor sites to exert a pharmacological effect.

Metabolism

Definition and Importance: Drug metabolism is the process of chemically altering drug molecules to create new compounds called metabolites [13]. This process is primarily a deactivation mechanism, converting lipophilic drugs into more water-soluble compounds to facilitate their excretion, though it can also activate prodrugs [11] [15].

Primary Pathways and Enzymes: The majority of small-molecule drug metabolism occurs in the liver via enzyme systems, with the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) family being the most prominent, responsible for metabolizing 70-80% of all drugs in clinical use [15].

- Phase I Reactions: Involve functionalization reactions such as oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis. These reactions, often mediated by CYP450 enzymes, typically introduce or expose a functional group, making the drug more polar [11] [13].

- Phase II Reactions: Conjugation reactions (e.g., glucuronidation, sulfation) that attach an endogenous molecule to the drug or its Phase I metabolite. This usually increases water solubility substantially and inactivates the drug, facilitating biliary or renal excretion [11] [13].

Factors Influencing Metabolism:

- Genetics: Genetic polymorphisms can result in individuals being classified as poor metabolizers (PMs) or ultra-rapid metabolizers (UMs), leading to significant variability in drug exposure and response [15].

- Drug-Drug Interactions: Concomitant medications can inhibit or induce metabolic enzymes, leading to clinically significant interactions [15].

- Age: Liver function is reduced in the elderly and immature in newborns, requiring special dosing considerations [15] [16].

- Organ Impairment: Liver disease can profoundly impair drug metabolism [13].

Excretion

Definition and Importance: Excretion is the process by which the drug and its metabolites are eliminated from the body [11]. This process, along with metabolism, determines the duration and intensity of a drug's action [12].

Routes and Mechanisms of Excretion:

- Renal Excretion: The kidneys are the most important organs for excretion [12]. Renal clearance involves three main mechanisms: glomerular filtration of unbound drug, active secretion by transporters in the tubules, and passive reabsorption [11] [12].

- Biliary/Fecal Excretion: Some drugs and their metabolites are excreted into the bile and then into the feces [12].

- Other Routes: Excretion can also occur via the lungs (e.g., anesthetic gases), sweat, and breast milk [12].

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Elimination:

- Clearance (CL): Defined as the ratio of a drug's elimination rate to the plasma drug concentration. It is a critical parameter for determining the maintenance dose rate [11].

- Half-Life (t½): The time required for the plasma concentration of a drug to decrease by 50%. It is directly proportional to the volume of distribution and inversely proportional to clearance (t½ = 0.693 × Vd / Clearance) [11]. A drug is generally considered eliminated after four to five half-lives [11].

- Drug Kinetics: Most drugs follow first-order kinetics, where the rate of elimination is proportional to the drug concentration. Some drugs, like phenytoin and alcohol, follow zero-order kinetics at high concentrations, where the elimination rate is constant and independent of concentration due to enzyme saturation [11].

Quantitative Pharmacokinetic Parameters

A critical component of pharmacokinetic prediction is the quantification of key parameters that define the ADME profile of a drug. These values are essential for building robust in silico models and making accurate predictions of human pharmacokinetics.

Table 2: Key Quantitative PK Parameters and Their Applications

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Formula/Description | Clinical/Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioavailability | F | Fraction of administered dose that reaches systemic circulation [11] | F = (AUCoral / AUCIV) * (DoseIV / Doseoral) [11] | Determines equivalent dosing between routes [11] |

| Area Under the Curve | AUC | Total drug exposure over time [11] | Integral of plasma concentration-time curve [11] | Used to calculate bioavailability and clearance [11] |

| Volume of Distribution | Vd | Apparent volume into which a drug distributes [11] | Vd = Amount of drug in body / Plasma drug concentration [11] | Predicts loading dose; indicates extent of tissue distribution [11] |

| Clearance | CL | Volume of plasma cleared of drug per unit time [11] | CL = Elimination rate / Plasma concentration [11] | Determines maintenance dose rate [11] |

| Half-Life | t½ | Time for plasma concentration to reduce by 50% [11] | t½ = (0.693 * Vd) / CL [11] | Predicts time to steady-state and time for drug elimination [11] |

4In SilicoADME Prediction: Methods and Protocols

Computational ADME prediction has become an integral part of drug discovery, helping to identify potential liabilities early and optimize lead compounds [14]. A variety of in silico methods are employed, ranging from fundamental quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to complex physiological simulations.

Predominant Computational Methods

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): This method uses statistical modeling to relate a drug's molecular descriptors or structural properties to its biological activity or ADME properties [14] [12]. It is widely used for high-throughput virtual screening.

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: PBPK models simulate the concentration-time profile of a drug in different tissues by incorporating physiological parameters (e.g., organ sizes, blood flows), tissue composition, and drug-specific properties [14]. These models are powerful for predicting human PK, exploring drug-drug interactions (DDIs), and supporting regulatory submissions [17].

- Molecular Docking: This technique predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (drug) when bound to a target macromolecule (e.g., a CYP enzyme or transporter) [14]. It helps in understanding and predicting metabolic stability and transporter-mediated DDIs.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations provide atomic-level detail of the motions and interactions of a drug with its environment over time, offering insights into binding affinities and reaction mechanisms relevant to metabolism [14].

Diagram 2: In Silico ADME Prediction Workflow. This flowchart outlines the primary computational approaches used to predict ADME properties from a compound's molecular structure, leading to data-driven lead optimization.

Experimental Protocols forIn VitroADME Assay

The development and validation of in silico models rely heavily on high-quality experimental data from standardized in vitro assays. The following protocols represent core methodologies for characterizing ADME properties.

Protocol 1: Metabolic Stability Assay Using Liver Microsomes

Objective: To determine the intrinsic metabolic clearance of a drug candidate by measuring its degradation rate in liver microsomes.

Materials:

- Test compound (e.g., drug candidate)

- Liver microsomes (human or relevant species) - source of CYP450 enzymes [17]

- NADPH-regenerating system - cofactor for CYP450 reactions

- Phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Stop solution (e.g., acetonitrile with internal standard)

- LC-MS/MS system for analytical quantification

Procedure:

- Incubation Preparation: Prepare incubation mixtures containing liver microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL protein) and the test compound (e.g., 1 µM) in phosphate buffer. Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the NADPH-regenerating system.

- Time Course Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes), remove aliquots from the incubation mixture and transfer them to a plate containing the stop solution to denature proteins and terminate the reaction.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the stopped samples to precipitate proteins. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine the remaining concentration of the parent compound over time.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the parent compound concentration remaining versus time. The slope of the linear phase is the elimination rate constant (k). Intrinsic clearance (CLint) is calculated as CLint = k / (microsomal protein concentration).

Protocol 2: Caco-2 Permeability Assay for Predicting Absorption

Objective: To assess the intestinal permeability and potential for oral absorption of a drug candidate using a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2).

Materials:

- Caco-2 cell line

- Transwell plates (e.g., 12-well format with polycarbonate membranes)

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with fetal bovine serum (FBS)

- Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with HEPES buffer (pH 7.4)

- Test compound

- LC-MS/MS system for analytical quantification

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Seed Caco-2 cells onto Transwell membranes at a high density and culture for 21-28 days to allow for differentiation and formation of a confluent monolayer. Monitor transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) to confirm monolayer integrity.

- Experiment Setup: On the day of the experiment, wash the cell monolayers with pre-warmed HBSS. Add the test compound to the donor compartment (apical for A→B transport, basolateral for B→A transport). Fill the receiver compartment with blank HBSS.

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the plates at 37°C with gentle shaking. Sample from the receiver compartment at regular intervals (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) and replace with fresh pre-warmed HBSS.

- Sample Analysis: Quantify the concentration of the test compound in the receiver samples using LC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A * C0), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the surface area of the membrane, and C0 is the initial donor concentration.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADME Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in ADME Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Individual human cytochrome P450 isoforms for reaction phenotyping and DDI studies. | Identifying which specific CYP enzyme is responsible for metabolizing a drug candidate [15]. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Intact liver cells containing full complement of phase I and II metabolic enzymes; used for more physiologically relevant metabolism studies. | Assessing metabolic stability and metabolite identification [17]. |

| Transfected Cell Lines | Cell lines overexpressing specific transporters (e.g., P-gp, BCRP, OATP). | Evaluating potential for transporter-mediated drug-drug interactions and permeability [17]. |

| Plasma Proteins | Human serum albumin (HSA) and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG) for protein binding studies. | Determining the fraction of drug that is unbound and pharmacologically active using assays like equilibrium dialysis [11] [13]. |

| PBPK Software Platforms | Commercial software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim) for simulating ADME in virtual populations. | Predicting human pharmacokinetics, food effects, and DDI potential prior to first-in-human studies [17] [14]. |

| Radiolabeled Compounds | Drug molecules labeled with isotopes (e.g., ¹⁴C, ³H) to track the fate of the drug and its metabolites. | Conducting definitive human ADME studies to elucidate mass balance and metabolic pathways [17]. |

Data Visualization and Model Communication in Pharmacokinetics

Effective communication of complex pharmacokinetic data and model outcomes is essential for informing drug development decisions. Visualization techniques transform numerical data into intuitive graphics, facilitating pattern recognition and timely decision-making [18].

Key Visualization Techniques:

- Line Graphs: The standard for depicting changes in drug concentration over time, allowing for the visualization of absorption and elimination profiles and the determination of parameters like half-life and Tmax [18].

- Visual Predictive Checks (VPCs): A graphical qualification tool where percentiles of observed data are overlaid with confidence intervals of the corresponding percentiles from model-based simulations. This assesses how well a population PK model captures the central tendency and variability of the data [19].

- Box-and-Whisker Plots: Useful for comparing the distribution of PK parameters (e.g., AUC, Cmax) across different patient populations, dose groups, or formulations [18].

- Interactive Visualization: Advanced software tools allow for interactive exploration of models, enabling project teams to ask "what-if" questions in real-time (e.g., "What is the impact of a higher dose or a different dosing interval?") and see the simulated outcomes immediately, thereby streamlining the decision-making process [19] [20].

The thorough understanding of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) processes forms the bedrock of pharmacokinetic science. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, the integration of robust in vitro and in vivo experimental data with sophisticated in silico prediction models is no longer optional but a necessity for efficient and successful drug development. The quantitative parameters derived from ADME studies directly enable the design of safe and effective dosing regimens, while computational tools like PBPK modeling and QSAR provide a powerful means to anticipate and overcome ADME-related challenges earlier in the pipeline. As these computational methods continue to evolve, their role in de-risking drug development and enabling truly predictive pharmacokinetics will only become more pronounced, ultimately accelerating the delivery of new therapies to patients.

The Role of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) in Early Parameter Estimation

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental computational approach in modern drug discovery and development, enabling the prediction of biological activity, pharmacokinetic properties, and toxicity of compounds directly from their molecular structures. These methodologies have become indispensable tools for early parameter estimation, particularly within the broader context of silico pharmacokinetic prediction research. By establishing mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and experimentally determined biological endpoints, QSAR models allow researchers to prioritize promising candidate molecules, reduce reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental assays, and adhere to the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal testing [21] [22].

The evolution of QSAR has progressed from traditional linear regression models based on simple physicochemical properties to sophisticated machine learning and deep learning algorithms that leverage vast chemical databases and complex molecular descriptors [23] [24]. This technical guide explores the core methodologies, applications, and emerging trends in QSAR modeling, with a specific focus on its critical role in predicting key pharmacokinetic parameters during the early stages of drug development. By providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing these computational approaches, this whitepaper aims to support the development of more efficient and predictive drug discovery pipelines.

Fundamental QSAR Methodologies in Pharmacokinetic Prediction

Molecular Descriptors and Feature Selection

The foundation of any robust QSAR model lies in the careful selection and computation of molecular descriptors that numerically represent structural and physicochemical properties of compounds. These descriptors can be broadly categorized into several classes:

- Constitutional descriptors: Basic molecular properties including molecular weight, number of atoms, bonds, or rings [25]

- Topological descriptors: Graph-based representations encoding molecular connectivity patterns

- Geometrical descriptors: Parameters derived from the three-dimensional structure of molecules

- Electronic descriptors: Quantities representing electronic distribution such as dipole moment, polar surface area (PSA), and highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) or lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies [25]

- Quantum chemical descriptors: Properties calculated using quantum mechanical methods

Feature selection techniques are critically important for developing predictive and interpretable QSAR models. Methods such as Genetic Function Approximation (GFA), permutation importance analysis in random forest, and stepwise regression help identify the most relevant descriptors while reducing the risk of overfitting [24] [26]. For instance, in a QSAR study on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, polar surface area, dipole moment, and molecular weight were identified as the key structural properties governing inhibitory activity [25].

Statistical Modeling Approaches

QSAR modeling employs a diverse range of statistical and machine learning algorithms to establish quantitative relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activities:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Creates linear models based on descriptor-activity relationships, providing easily interpretable equations [25]

- Multiple Non-Linear Regression (MNLR): Captures non-linear relationships in the data

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): Powerful pattern recognition algorithms capable of modeling complex non-linear relationships [27]

- Random Forest: Ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their predictions [24]

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for classification and regression tasks in high-dimensional spaces

- Deep Learning (DL): Advanced neural network architectures that can automatically learn relevant features from raw molecular data or images [24]

The selection of an appropriate modeling technique depends on the dataset characteristics, the complexity of the structure-activity relationship, and the desired balance between model interpretability and predictive power.

Experimental Protocols for QSAR Model Development

Standard QSAR Modeling Workflow

A robust QSAR modeling protocol involves several critical steps to ensure predictive reliability and regulatory acceptance:

Data Collection and Curation: Compile a structurally diverse set of compounds with reliable experimental biological activity data (e.g., IC50, EC50, clearance values). The dataset should encompass sufficient chemical diversity to represent the intended application domain [27] [24].

Chemical Structure Representation and Optimization: Generate accurate 2D or 3D molecular structures using software such as Chem3D or Gaussian. Perform geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MM2) or quantum chemical methods (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G(d)) to obtain energetically stable conformations [27].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Compute comprehensive descriptor sets using specialized software packages including Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), alvaDesc, or ADMET Predictor. The number of calculated descriptors often ranges from hundreds to thousands per compound [24].

Dataset Division: Split the dataset into training and test sets using appropriate methods such as Kennard-Stone algorithm, random selection, or k-means clustering. Typically, 70-80% of compounds are allocated for model training, while the remaining 20-30% are reserved for external validation [27] [24].

Model Construction and Internal Validation: Develop QSAR models using selected algorithms on the training set. Perform internal validation using techniques such as leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out (LMO) cross-validation to assess model robustness [27] [25].

External Validation and Applicability Domain Assessment: Evaluate the predictive performance of the finalized model on the external test set. Define the model's applicability domain to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable [25].

Advanced Protocol: DeepSnap-Deep Learning Integration

Recent advances have introduced innovative protocols such as the DeepSnap-Deep Learning (DeepSnap-DL) approach for improved prediction of challenging pharmacokinetic parameters like clearance:

Compound Image Generation: Capture multiple 2D snapshots of chemical structures from different rotational angles (e.g., 65°, 85°, 105°, and 145°) using DeepSnap software [24].

Deep Learning Model Configuration: Implement convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with optimized hyperparameters including learning rate (typically ranging from 0.0000001 to 0.001) and maximum epoch conditions (15-300) [24].

Model Selection and Validation: Identify the optimal model configuration based on validation set performance metrics, particularly area under the curve (AUC) values. For clearance prediction, the best performance was observed at 145° with a maximum epoch of 300 and learning rate of 0.000001 [24].

Ensemble Model Development: Combine predictions from conventional machine learning (using molecular descriptors) and DeepSnap-DL approaches by averaging predicted probabilities or implementing consensus strategies to significantly enhance predictive performance [24].

QSAR Applications in Key Pharmacokinetic Parameter Estimation

Prediction of Plasma Concentration-Time Profiles

The application of QSAR modeling has expanded beyond predicting individual pharmacokinetic parameters to forecasting complete plasma concentration-time profiles. A novel approach involves implicitly integrating deep neural networks with compartmental pharmacokinetic models, enabling direct prediction of concentration curves from chemical structures and in vitro/in silico ADME features [21].

In a comprehensive study utilizing 1,162 compounds across 30 projects, this integrated approach demonstrated significantly improved prediction accuracy compared to methods explicitly using PK parameters. The model achieved median R² values of 0.530-0.673 for intravenous administration and 0.119-0.432 for oral administration in 5-fold cross-validation, outperforming traditional techniques [21]. The methodology employed Integrated Gradients to elucidate feature attributions and their temporal dynamics, providing insights consistent with established pharmacokinetic principles [21].

Clearance Prediction Using Advanced Modeling Techniques

Clearance represents one of the most critical and challenging pharmacokinetic parameters to predict. Recent research has addressed this challenge through innovative modeling strategies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Clearance Prediction Models

| Model Type | Dataset Size | Algorithm | AUC | Accuracy | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional ML | 1,545 compounds | Random Forest | 0.883 | 0.825 | 100 molecular descriptors selected by permutation importance [24] |

| DeepSnap-DL | 1,545 compounds | Deep Learning | 0.905 | 0.832 | Compound images from multiple angles [24] |

| Ensemble Model | 1,545 compounds | RF + DeepSnap-DL | 0.943 | 0.874 | Mean of predicted probabilities from both models [24] |

| Consensus Model | 1,545 compounds | RF + DeepSnap-DL | 0.958 | 0.959 | Agreement between classifications [24] |

The ensemble approach, which combines conventional machine learning with DeepSnap-DL, demonstrated particularly strong performance, highlighting the value of integrating multiple modeling paradigms for challenging prediction targets [24].

Integrated QSAR-PBPK Modeling Frameworks

The integration of QSAR with physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling represents a significant advancement in predictive pharmacokinetics. This hybrid approach enables the prediction of tissue distribution and concentration-time profiles for compounds with limited experimental data [28].

A recent application of this framework focused on 34 fentanyl analogs, addressing the significant public health threat posed by these emerging new psychoactive substances. The QSAR-PBPK workflow involved:

Parameter Prediction: Using QSAR models within ADMET Predictor software to estimate critical PBPK input parameters including logD, pKa, and unbound fraction in plasma [28].

Model Validation: Validating the framework using intravenous β-hydroxythiofentanyl in rats, with all predicted PK parameters (AUC₀–t, Vss, T₁/₂) falling within a 2-fold range of experimental values [28].

Tissue Distribution Prediction: Simulating plasma and tissue distribution (including brain and heart) for 34 human fentanyl analogs, identifying eight compounds with brain/plasma ratios >1.2 (compared to fentanyl's ratio of 1.0), indicating higher CNS penetration and abuse potential [28].

This integrated approach demonstrated superior accuracy for predicting human volume of distribution compared to traditional interspecies extrapolation methods (error <1.5-fold vs. >3-fold), providing a scalable strategy for pharmacokinetic evaluation of poorly characterized compounds [28].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 2: QSAR Model Performance Across Different Pharmacokinetic Applications

| Application Area | Endpoint | Dataset Size | Model Type | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Concentration Profiles | IV administration | 1,162 compounds | DNN + 2-compartment model | R² = 0.530-0.673 (5-fold CV) [21] |

| Plasma Concentration Profiles | Oral administration | 1,162 compounds | DNN + 2-compartment model | R² = 0.119-0.432 (5-fold CV) [21] |

| Rat Clearance Prediction | Classification (High/Low CL) | 1,545 compounds | Ensemble (RF + DeepSnap-DL) | AUC = 0.943, Accuracy = 0.874 [24] |

| Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition | pIC50 | 48 compounds | Multiple Linear Regression | R² = 0.701, Q²CV = 0.638, R²test = 0.76 [25] |

| Fentanyl Analog PBPK | Volume of Distribution | 34 compounds | QSAR-PBPK | Error <1.5-fold vs. clinical data [28] |

Visualization of QSAR Workflows

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for QSAR-Based Pharmacokinetic Prediction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in PK Parameter Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor | Software | Molecular descriptor calculation and ADMET prediction | Predicts critical PBPK input parameters (logD, pKa, Fup) [28] |

| GastroPlus | Software | PBPK modeling and simulation | Integrates QSAR-predicted parameters for whole-body PK simulation [28] |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Software | Molecular modeling and descriptor calculation | Calculates comprehensive sets of molecular descriptors for QSAR [24] |

| alvaDesc | Software | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generates 2D/3D molecular descriptors for model development [24] |

| DataRobot | Platform | Automated machine learning | Builds and optimizes multiple prediction models for PK parameters [24] |

| DeepSnap | Software | Compound image generation | Creates 2D molecular images for deep learning approaches [24] |

| Gaussian | Software | Quantum chemical calculations | Computes electronic properties and optimizes molecular geometry [27] |

| National Cancer Institute (NCI) Database | Database | Chemical compound repository | Source of potential inhibitors for virtual screening [26] |

| PubChem Database | Database | Chemical structure and bioactivity | Provides structural information for compounds [28] |

QSAR modeling has evolved from a supplementary tool to a central methodology in early pharmacokinetic parameter estimation, enabling researchers to make informed decisions during the critical early stages of drug discovery. The integration of advanced machine learning techniques, novel molecular representations such as compound images, and hybrid modeling approaches like QSAR-PBPK frameworks has significantly enhanced the predictive accuracy and applicability of these computational methods. As the field continues to advance, driven by growing datasets, improved algorithms, and increased computational power, QSAR approaches are poised to become even more indispensable in the development of efficient, predictive, and translatable drug discovery pipelines. The ongoing challenge remains in the continual validation and refinement of these models to ensure their reliability and regulatory acceptance across diverse chemical domains and biological systems.

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the ability to accurately predict a compound's pharmacokinetic (PK) profile—its journey through absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within a living organism—is paramount for both efficacy and safety. In silico modeling has emerged as a cornerstone technology, enabling researchers to simulate biological systems computationally, thereby reducing reliance on extensive animal experimentation and accelerating development timelines [29]. These models span a spectrum from descriptive, top-down approaches to mechanistic, bottom-up representations of physiology. Among these, compartmental modeling serves as a fundamental framework, representing the body as a set of interconnected, homogeneous chambers between which drugs transit [30]. However, a significant challenge persists in bridging the output of these models with true physiological relevance, ensuring that predictions accurately reflect the complex, spatially heterogeneous, and dynamically regulated environment of a biological system. This guide details the principles of compartmental modeling and explores advanced computational strategies that enhance the biological fidelity of in silico PK predictions, framing them within the broader thesis of establishing robust, predictive pharmacokinetics in early-stage research.

Foundations of Compartmental Modeling

Compartmental models are composed of sets of interconnected mixing chambers or "stirred tanks," where each compartment is considered homogeneous and instantly mixed, with a uniform concentration of the substance being modeled [30]. The state variables are typically concentrations or molar amounts of chemical species, and the processes that move these species between compartments—such as chemical reactions, transmembrane transport, and binding—are generally treated using first-order rate equations.

Core Principles and Mathematical Formalism

The fundamental simplicity of representing systems via ordinary differential equations (ODEs) makes compartmental models computationally tractable. A generic mass balance for a drug in a compartment yields the equation:

dA_i/dt = Input - Output + Σ_j k_ji A_j - Σ_j k_ij A_i - k_el_i A_i

Where:

A_iis the amount of drug in compartmenti.k_ijandk_jiare the first-order rate constants for transfer between compartmentsiandj.k_el_iis the elimination rate constant from compartmenti.

While these models have a reputation for being descriptive "black boxes," they can be refined to incorporate realistic mechanistic features through more sophisticated kinetics [30]. In pharmacokinetics, compartments represent homogeneous pools of particular solutes, with inputs and outputs defined as flows or solute fluxes. The primary output is the concentration-time curve, which describes how long a drug remains available in the body and guides dosage regimen design [30].

Table 1: Common Compartmental Model Structures in Pharmacokinetics

| Model Structure | Description | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| One-Compartment | Body is represented as a single, uniformly mixed pool. | Initial, simplistic estimation of PK parameters. |

| Two-Compartment | Body is divided into a central compartment (e.g., plasma) and one peripheral compartment (e.g., tissues). | Characterizing drugs with a distinct distribution phase. |

| Multi-Compartment | Extension to multiple peripheral compartments with different distribution characteristics. | Modeling complex distribution patterns, e.g., into fat, bone, or specific organs. |

| Mammillary Model | A central compartment connected to multiple peripheral compartments, but no connections between peripherals. | Most common structure for PK analysis. |

| Catenary Model | Compartments connected in a linear chain. | Representing sequential processes, like absorption. |

Enhancing Physiological Relevance with Advanced Modeling

While traditional compartmental models are powerful, their assumption of homogeneity limits their physiological accuracy. To bridge this gap, several advanced modeling frameworks have been developed.

From Compartmental to Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling represents a significant leap towards physiological relevance. Instead of abstract compartments, PBPK models explicitly represent individual organs and tissues, interconnected by the circulatory system. Each organ has a physiologically realistic volume, blood flow rate, and can be characterized by tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients [31]. This allows for a mechanistic representation of ADME processes. The application of PBPK modeling in biopharmaceutics (PBBM) is increasingly used to establish a link between in vitro drug product performance and in vivo outcomes, helping to construct a bioequivalence safe space and set clinically relevant drug product specifications [31].

The Emergence of Machine Learning in PK Prediction

A novel paradigm is the direct prediction of PK profiles using machine learning (ML). One framework demonstrates that a rat's plasma concentration versus time profile can be predicted using molecular structure as the sole input [29]. This approach first predicts key ADME properties (like clearance and volume of distribution) from the compound's structure and then uses these as inputs to a second ML model that predicts the full PK profile, mitigating the need for animal experimentation in early stages [29]. For tested compounds, this method achieved an average mean absolute percentage error of less than 150%, providing a valuable tool for virtual PK analysis [29].

Hybrid and Multi-Scale Modeling

The future lies in multi-scale models that integrate different modeling philosophies. A PBPK model can serve as a scaffold for physiological realism, while ML algorithms can be used to predict difficult-to-measure input parameters directly from chemical structure [29] [32]. Furthermore, agent-based models (ABMs) can simulate localized tissue environments, representing individual cells or groups of cells and their interactions. For instance, an ABM of neural tube closure functionalizes cell signals and biomechanics to render a dynamic representation of the developmental process, predicting the nature and probability of defects from perturbations [33]. Integrating such fine-grained, dynamic models into a PBPK framework represents the cutting edge of physiological relevance.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Developing a Machine Learning Framework for PK Profile Prediction

This protocol is adapted from a study that predicted rat PK profiles from molecular structure [29].

Data Curation:

- Collect a dataset of molecular structures (represented as SMILES strings) with corresponding in vivo PK parameters (Clearance - CL, Volume of distribution - Vdss) and full concentration-time (PK profile) data.

- Preprocess SMILES strings: Strip salts, convert to canonical forms, and standardize.

- Represent molecules as numerical features using RDKit, generating either molecular fingerprints (e.g., 2048-bit Morgan fingerprint) or 200+ molecular descriptors (e.g., QED, TPSA, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors).

Feature and Model Selection:

- Perform exhaustive feature selection to identify the optimal input parameters (e.g., CL and Vdss alone, or combined with descriptors/fingerprints).

- Split the dataset into a training set (e.g., 85% of compounds) and a held-out test set (e.g., 15%).

- Train multiple ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, Support Vector Regressor) to predict the PK profile, using predicted CL, predicted Vdss, and time points as inputs. Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set for model selection and hyperparameter tuning.

Model Validation and Performance Assessment:

- Validate the final model on the test set.

- Assess performance using metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination (R²).

- Compare predicted and observed values for key PK metrics like C~max~ (peak concentration) and AUC~24h~ (Area Under the Curve up to 24 hours).

Figure 1: ML-based PK Prediction Workflow. A two-stage ML framework for predicting pharmacokinetic profiles directly from molecular structure.

Protocol: Building and Validating a PBBM for Clinically Relevant Specifications

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a Physiologically Based Biopharmaceutics Model (PBBM) for drug product development [31].

System Characterization:

- Drug Substance: Gather key physicochemical properties (solubility, pKa, logP, permeability, diffusivity).

- Physiology: Define the relevant human physiology (gastrointestinal fluid volumes, pH, bile salt levels, motility, transit times).

- Drug Product: Characterize the formulation, including dissolution profile under physiologically relevant conditions.

Model Construction:

- Select a robust PBPK platform (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim).

- Populate the model with the collected drug, physiological, and formulation data.

- Integrate a dissolution model to link the formulation's performance to the in vivo environment.

Model Verification and Application:

- Verify the model by comparing its predictions against observed human PK data (e.g., from a clinical study).

- Use the verified model to construct a bioequivalence safe space, which defines the boundaries of dissolution profiles that will not lead to clinically significant differences in exposure.

- Apply the model to set clinically relevant dissolution specifications and to support regulatory submissions for biowaivers or formulation changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational and Data Resources for In Silico PK Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| JSim | Software Platform | Open-source modeling system for solving ODEs and PDEs; used for general-purpose computational physiology, including compartmental modeling [30]. |

| Berkeley Madonna | Software Platform | A general-purpose ODE solver used for modeling physiological systems and dynamical systems [30]. |

| Simcyp Simulator | PBPK Software | A leading platform for PBPK modeling and simulation, widely used in the pharmaceutical industry for predicting human PK and drug-drug interactions. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics; used to convert SMILES strings into molecular descriptors and fingerprints for ML-based ADME prediction [29]. |

| Database of Essential Genes (DEG) | Database | A resource used in comparative genomics to identify genes essential for pathogen survival, aiding in therapeutic target discovery [34]. |

| UniProt | Database | A comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information, used for retrieving and comparing protein sequences [34]. |

| Leadscope Model Applier | QSAR Software | Provides predictive QSAR modeling for toxicology outcomes, supporting early risk assessments in drug discovery [35]. |

Visualization of Complex Biological Systems

To accurately model a biological process, one must first conceptualize its key components and their interactions. The following diagram outlines the core network involved in a specific morphogenetic process, neural tube closure, demonstrating how models can be built from known biology.

Figure 2: Agent-Based Model of Neural Tube Closure. A dynamic systems model showing how perturbations in signals and biomechanics can lead to defects [33].

The journey from simple, descriptive compartmental models to sophisticated, physiologically relevant simulations represents a paradigm shift in pharmacokinetic prediction. The integration of PBPK modeling provides a mechanistic framework that closely mirrors human physiology, while the advent of machine learning offers a powerful, data-driven approach to bypass early experimental bottlenecks. The ultimate bridge between in silico predictions and biological systems is being built through multi-scale, hybrid models that leverage the strengths of each approach. As these computational techniques continue to evolve, underscored by rigorous validation and a deep understanding of biology, they will increasingly enable researchers to make actionable predictions earlier in the drug design process. This will not only expedite development and reduce costs but also pave the way for more effective and safer therapeutics, fulfilling the core promise of in silico research.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling, the quantitative study of how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted (ADME) in the body, has long been a cornerstone of drug development. Traditional PK modeling approaches, particularly nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) modeling using established tools like NONMEM, have provided the fundamental framework for understanding drug behavior across populations. However, the increasing complexity of modern therapeutic modalities—from highly potent molecules with narrow therapeutic indices to complex biologic and nanoparticle formulations—has exposed the limitations of traditional methods. These challenges include handling massive parameter spaces, accounting for high inter-patient variability, and modeling non-linear kinetics from sparse clinical data.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) presents a paradigm shift, enhancing the efficiency, predictive accuracy, and scope of traditional PK modeling. AI/ML methodologies are not merely replacing established techniques but are creating powerful hybrid systems that combine mechanistic understanding with data-driven pattern recognition. This transformation is enabling more robust Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), accelerating the path from candidate selection to regulatory approval, and paving the way for truly personalized medicine. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of AI in PK modeling, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of this rapidly evolving landscape.

Performance Comparison: AI/ML vs. Traditional PK Modeling

A comparative analysis of AI-based and traditional PK modeling approaches reveals distinct performance advantages and optimal use cases for each methodology. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies evaluating these approaches on both simulated and real-world clinical datasets.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Traditional vs. AI/ML PK Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Key Characteristics | Performance Metrics | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional NLME (e.g., NONMEM) | Gold standard; mechanistic; highly interpretable; sequential model building [36] | Established benchmark; can struggle with complex, high-dimensional parameter landscapes [37] | Standard small molecules; scenarios with strong prior mechanistic knowledge |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models | Data-driven; handles complex patterns; multiple algorithms tested (e.g., Random Forest) [36] [38] | Often outperforms NONMEM; RMSE and MAE improvements vary by model and data [36] | Early screening of large compound libraries; analysis of high-dimensional data |

| Deep Learning (DL) Models | Complex neural networks; automatic feature extraction [36] | Strong performance, particularly with large datasets [36] | Modeling complex biologics (mAbs, nanoparticles); integrating diverse data types (e.g., imaging, -omics) |

| Neural ODEs | Combines neural networks with differential equations; balances flexibility and explainability [36] [39] | Provides strong performance and explainability, especially with large datasets [36] | Systems with complex, non-linear dynamics where some mechanistic understanding exists |

| Hybrid Mechanistic-AI | Integrates PBPK/PopPK with AI components; adds AI pattern recognition to known biology [40] | Enhances predictive power while maintaining scientific plausibility and regulatory trust [40] | Optimizing drug formulations; predicting API behavior with complex safety profiles |

Core AI/ML Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in PK Modeling

Automated Population PK Model Development

The labor-intensive, sequential process of traditional population PK (PopPK) model development is a prime target for automation. A 2025 study demonstrated an automated "out-of-the-box" approach for PopPK model development using the pyDarwin library [38].

- Objective: To automatically identify optimal PopPK model structures for drugs with extravascular administration, minimizing manual effort and timeline while ensuring model quality and biological plausibility [38].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Define Model Search Space: A generic search space of >12,000 unique PopPK model structures was constructed, covering various compartmental models, absorption mechanisms (first-order, zero-order, transit compartments), and elimination patterns [38].

- Implement Penalty Function: A dual-term penalty function was designed to automate model selection:

- Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) Term: Penalizes model overparameterization to ensure parsimony.

- Biological Plausibility Term: Penalizes abnormal parameter values (e.g., high relative standard errors, unrealistic inter-subject variability, high shrinkage) that expert modelers would reject [38].

- Execute Optimization: A combination of Bayesian optimization with a random forest surrogate and an exhaustive local search was used to efficiently navigate the vast model space, evaluating fewer than 2.6% of potential models on average [38].

- Key Findings: The automated approach reliably identified model structures comparable to or better than expert-developed models across four clinical and one synthetic dataset. For the synthetic ribociclib dataset, it recovered the exact true data-generation model. The average runtime was under 48 hours, significantly accelerating the model development cycle [38].

The following diagram illustrates the automated PopPK model development workflow.

Enhancing Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetics (PBPK) with AI

PBPK modeling offers a mechanistic framework for predicting drug disposition but is often constrained by a large number of uncertain parameters. AI/ML techniques are being applied to address these limitations [41] [42].

- AI for Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Quantification: ML algorithms, particularly Gaussian Process Emulators, can be trained on a limited set of PBPK simulations to create a rapid surrogate model. This surrogate can be used for global sensitivity analysis (e.g., using Latin Hypercube Sampling) to identify the most influential parameters, thereby reducing the effective dimensionality of the problem and focusing experimental resources [42].

- Addressing Data Gaps with QSAR and Deep Learning: For parameters difficult to measure experimentally, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models powered by deep learning can predict ADME properties directly from a compound's chemical structure, informing and refining PBPK models earlier in the development process [41] [40].

Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs)

A particularly innovative architecture bridging mechanistic and AI-driven modeling is the Neural ODE. This model uses a neural network to parameterize the derivative of the system's state, which is then integrated using an ODE solver [36] [39]. This approach inherently respects the temporal continuity of PK processes and can learn dynamics from irregularly sampled data, offering a powerful tool for modeling complex, non-linear PK profiles where traditional compartmental models may be insufficient [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for AI-Enhanced PK Research

Implementing AI-driven PK modeling requires a suite of computational tools and platforms. The table below details key software and libraries that form the modern PK scientist's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Enhanced PK Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in AI/PK Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Software | Industry-standard for NLME modeling; often used as the engine for model fitting in automated workflows [38]. |

| pyDarwin | Python Library | Specialized library for automated PopPK model development and selection using advanced optimization algorithms [38]. |

| MonolixSuite | Software Suite | Provides an integrated environment for PK/PD modeling, with increasing integration of ML-assisted features for model selection and diagnostics [40]. |

| Neural ODEs | Modeling Architecture | Available in deep learning frameworks (PyTorch, TensorFlow); used for creating flexible hybrid models that combine neural networks with ODE systems [36] [39]. |

| PBPK Platforms | Software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) | Mechanistic PBPK simulators that can be augmented with AI/ML for parameter estimation, sensitivity analysis, and uncertainty quantification [41] [42]. |

| SciBERT / BioBERT | NLP Model | Pre-trained language models for mining biomedical literature to extract drug-disease relationships and PK parameters [43]. |

Applications and Implementation in Drug Development

Key Application Areas

- Early-Stage Discovery and ADMET Prediction: AI/ML models can rapidly predict a full suite of ADME and toxicity properties directly from chemical structure, enabling virtual screening of vast compound libraries to de-risk candidates before significant investment [40]. For instance, ML models can predict the pharmacokinetic profile of small molecule drugs based solely on their molecular structure, providing high-throughput screening with minimal wet lab data [44].

- Optimizing Clinical Development: In clinical stages, ML-based models analyze sparse patient data to efficiently identify covariates (e.g., age, renal function, genetics) that contribute to variability in drug response. This leads to more robust population PK models and better-informed dosing strategies for special populations [40]. AI tools have also been developed to predict nonspecific treatment response in placebo-controlled trials, improving trial design and analysis [44].

- Model-Informed Precision Dosing (MIPD): AI facilitates a shift towards personalized medicine by enabling the development of models that predict individual drug exposure and response. Architectures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Neural ODEs can handle irregular and sparse data from clinical settings, supporting the implementation of adaptive dosing regimens tailored to individual patient constraints [39].

Implementation Workflow

The diagram below outlines a synergistic workflow that integrates traditional and AI-driven approaches throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the integration of AI into PK modeling faces several hurdles. The "black box" nature of some complex ML models can lack the transparency required for regulatory acceptance and scientific confidence [39] [40]. There is a critical need for large, high-quality, and well-curated datasets to train reliable models, as limited or biased data can lead to poor generalizability [40]. Furthermore, establishing "good machine learning practice" and standardized validation frameworks is essential for building trust with regulators [40].

The future evolution of AI in PK modeling will likely focus on explainable AI (XAI) to demystify model predictions and hybrid systems that deeply integrate mechanistic science with AI's pattern recognition capabilities [40]. As these models become more robust, they will advance in silico clinical trial simulation, allowing researchers to forecast outcomes under different scenarios and optimize trial protocols before enrolling patients [40]. Ultimately, the field is moving towards leveraging AI to integrate vast, patient-specific datasets—from genomics to real-world data—to enable accurate predictions of an individual's unique response to a drug, paving the way for optimized personalized treatments [39] [40].

The transformation of traditional PK modeling by AI and machine learning is well underway, moving from theoretical potential to tangible applications across the drug development continuum. By automating labor-intensive processes, uncovering complex patterns in high-dimensional data, and creating hybrid models that are both predictive and interpretable, AI is augmenting the capabilities of pharmacometricians and clinical pharmacologists. This synergy between mechanistic understanding and data-driven insight is creating a more efficient, robust, and predictive framework for pharmacokinetics. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this evolving landscape is no longer optional but essential to accelerating the delivery of new and personalized therapies to patients.

Methodologies in Action: PBPK, QSP, and AI-Driven Workflows for PK/PD Prediction

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling represents a advanced mathematical framework that revolutionizes how researchers predict the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of synthetic or natural chemical substances in humans and other animal species [1]. Unlike classical pharmacokinetic (PK) models that conceptualize the body as a system of abstract mathematical compartments with parameters lacking direct physiological referents, PBPK modeling is structured upon a mechanism-driven paradigm [45] [46]. This approach represents the body as a network of physiological compartments corresponding to specific organs and tissues (e.g., liver, kidney, brain) interconnected by blood circulation, integrating system-specific physiological parameters with drug-specific properties [46]. This fundamental difference provides PBPK models with remarkable extrapolation capability, enabling researchers to not only describe observed pharmacokinetic data but also quantitatively predict systemic and tissue-specific drug exposure under untested physiological or pathological conditions [46].