In Silico ADMET Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Drug Discovery

In silico ADMET prediction has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to assess the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of compounds early in the...

In Silico ADMET Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Drug Discovery

Abstract

In silico ADMET prediction has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to assess the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of compounds early in the development process. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the foundational concepts, methodological approaches, current challenges, and validation strategies in computational ADMET profiling. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores how these high-throughput, cost-effective computational techniques help reduce late-stage attrition rates through the 'fail early, fail cheap' strategy. The content bridges theoretical frameworks with practical applications, addressing both small molecules and natural products, while examining the integrated use of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo platforms for optimized decision-making in pharmaceutical R&D.

The Foundation of In Silico ADMET: Core Principles and Evolutionary Landscape

ADMET is an acronym that stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. These five pharmacokinetic and safety parameters are paramount for determining the viability and efficacy of any therapeutic agent [1]. Ideal ADMET characteristics govern how a drug interacts with the human body, directly influencing its bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and the likelihood of regulatory approval [2].

The evaluation of these properties remains a critical bottleneck in drug discovery and development, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates [3]. Current industry data indicates that approximately 95% of new drug candidates fail during clinical trials, with up to 40% failing due to toxicity concerns and nearly half due to insufficient efficacy, often linked to poor pharmacokinetics [1]. The median cost of a single clinical trial stands at $19 million, translating to billions of dollars lost annually on failed drug candidates [1]. This economic pressure has fundamentally catalyzed the adoption of in silico ADMET prediction as a vital survival strategy for pharmaceutical research and development.

Table 1: Fundamental ADMET Properties and Their Impact on Drug Development

| Property | Definition | Significance in Drug Discovery | Key Experimental Assays/Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | How much and how rapidly a drug is absorbed into systemic circulation. | Determines bioavailability and optimal route of administration (especially oral). | Caco-2 Permeability Assay, intestinal permeability models [2] [1]. |

| Distribution | How a drug travels through the body to various tissues and organs after absorption. | Influences drug concentration at the target site and potential off-target effects. | Plasma Protein Binding, Volume of Distribution, Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration studies [2] [1]. |

| Metabolism | The biochemical transformation of drugs by enzymatic systems in the body. | Affects drug clearance, duration of action, and formation of active/toxic metabolites. | Metabolic stability assays, CYP450 enzyme interaction studies [2] [4] [1]. |

| Excretion | The process by which a drug and its metabolites are eliminated from the body. | Crucial for determining dosing regimens and preventing accumulation and toxicity. | Renal clearance, biliary excretion, half-life studies [2] [1]. |

| Toxicity | The potential for a drug to cause adverse effects or damage to the organism. | Essential for ensuring drug safety and reducing late-stage clinical failures. | Cytotoxicity, organ-specific toxicity (e.g., hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity/hERG), mutagenicity assays [2] [1] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for ADMET Evaluation

Traditional ADMET assessment relies on a suite of well-established in vitro and in vivo experimental methods. These protocols, while resource-intensive, provide critical data for regulatory submissions and remain the gold standard for validation.

Protocol: Caco-2 Permeability Assay for Predicting Intestinal Absorption

1. Principle: This in vitro assay uses a monolayer of human colon adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2) that, upon differentiation, exhibit properties similar to intestinal epithelial cells. It measures a compound's ability to cross the intestinal barrier, a key determinant of oral absorption [2] [1].

2. Materials:

- Caco-2 cell line

- Transwell plates (e.g., 12-well format with polycarbonate membranes, 1.12 cm² surface area, 0.4 µm pore size)

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), non-essential amino acids, L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin

- Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 10mM HEPES (pH 7.4)

- Test compound dissolved in DMSO (final concentration typically <1%)

- LC-MS/MS system for analytical quantification

3. Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Seeding: Maintain Caco-2 cells in culture. Seed cells onto the apical (AP) side of the Transwell insert at a high density (~100,000 cells/cm²). Culture for 21-28 days, changing the medium every 2-3 days, to allow for full differentiation and tight junction formation. Monitor transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) to confirm monolayer integrity (TEER > 300 Ω·cm² is typically acceptable).

- Experimental Setup: On the day of the experiment, wash the cell monolayers twice with pre-warmed HBSS-HEPES buffer. Add the test compound (typically 10-100 µM) to the AP side (donor compartment). The basolateral (BL) side (receiver compartment) contains blank buffer. Include a low-permeability control (e.g., Lucifer Yellow) and a high-permeability control (e.g., Propranolol).

- Sampling and Analysis: Incubate the plates at 37°C with gentle agitation. Collect samples from the BL compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) and replace with fresh buffer. Collect a final sample from the AP side. Analyze all samples using a validated LC-MS/MS method to determine compound concentrations.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) using the formula: Papp (cm/s) = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the rate of compound appearance in the receiver compartment (µmol/s), A is the surface area of the membrane (cm²), and C₀ is the initial concentration in the donor compartment (µM).

Protocol: hERG Inhibition Assay for Cardiotoxicity Screening

1. Principle: This assay evaluates a compound's potential to block the human Ether-à-go-go–Related Gene (hERG) potassium channel, inhibition of which is a major mechanism of drug-induced arrhythmia (Torsades de Pointes) [6] [5]. It is a regulatory cornerstone for safety assessment.

2. Materials:

- Cell line stably expressing the hERG potassium channel (e.g., HEK293-hERG or CHO-hERG)

- Patch-clamp electrophysiology setup (manual or automated) or a fluorescence-based membrane potential assay kit

- Extracellular and intracellular recording solutions

- Test compound and positive control (e.g., E-4031, Cisapride)

3. Procedure (Manual Patch-Clamp - Gold Standard):

- Cell Preparation: Culture hERG-expressing cells under standard conditions. On the day of the experiment, dissociate cells to create a single-cell suspension.

- Electrophysiology Recording: Place a cell suspension in the recording chamber. Establish a whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration using a borosilicate glass micropipette. Maintain the cell at a holding potential of -80 mV.

- Voltage Protocol: Apply a depolarizing pulse to +20 mV for 4 seconds to fully activate hERG channels, followed by a repolarization step to -50 mV for 5 seconds to elicit the large outward tail current (IhERG), which is the quantitative measure. Repeat this protocol every 10-15 seconds.

- Compound Application: After obtaining a stable baseline recording of IhERG, apply the test compound at increasing concentrations (e.g., 0.1, 1, 10 µM) to the extracellular solution. Perfuse each concentration for a sufficient time (~5-10 minutes) to reach equilibrium blockade.

- Data Analysis: Measure the peak amplitude of IhERG during the repolarization step after each compound application. Normalize the amplitude to the baseline pre-drug level. Plot the normalized current against the compound concentration and fit the data with a Hill equation to calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀).

Diagram 1: hERG inhibition assay workflow for cardiotoxicity screening.

The Shift to In Silico ADMET Prediction

The impracticality and high cost of performing exhaustive experimental ADMET procedures on thousands of compounds have propelled computational prediction to the forefront of early drug discovery [1]. This shift embraces the strategic philosophy to “fail early and fail cheap” by identifying compounds with poor ADMET profiles before they enter costly development phases [1].

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as transformative tools in this domain [3]. These approaches leverage large-scale compound databases to enable high-throughput predictions with improved efficiency and accuracy, often outperforming traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [3] [2]. ML models can capture complex, non-linear relationships between molecular structure and ADMET endpoints that are difficult to model with traditional methods [2].

Table 2: Progression of In Silico ADMET Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Era | Key Methodologies | Typical Molecular Representations | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early QSAR (2000s) | Linear Regression, Partial Least Squares, 3D-QSAR, Pharmacophore Modeling. | Predefined 2D molecular descriptors (e.g., cLogP, TPSA), 3D pharmacophores. | Cost-effective, interpretable, established workflow. | Limited applicability domain, struggles with novel scaffolds, dependent on high-quality 3D structures [1]. |

| Modern Machine Learning (2010s) | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost. | Extended molecular fingerprints (ECFP), large descriptor sets (e.g., Mordred). | Handles non-linear relationships, improved accuracy on larger datasets, higher throughput. | Relies on manual feature engineering, may not generalize well to entirely new chemical space [2] [6]. |

| Deep Learning (Current) | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, Multi-Task Learning (MTL). | SMILES strings, Molecular Graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges). | Automatic feature extraction, state-of-the-art accuracy, models complex structure-property relationships. | "Black-box" nature, high computational cost, requires large amounts of data [2] [7] [8]. |

Protocol: Building a Graph Neural Network for ADMET Prediction

1. Principle: GNNs directly operate on the molecular graph structure, where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges. This allows the model to learn features relevant to biological activity directly from the data, leading to superior predictive performance for many ADMET endpoints [2] [5].

2. Materials (Research Reagent Solutions - Computational Tools):

- Programming Environment: Python (v3.8+)

- Deep Learning Framework: PyTorch or TensorFlow

- Cheminformatics Library: RDKit (for molecule processing and descriptor calculation)

- GNN Library: PyTor Geometric (PyG) or Deep Graph Library (DGL)

- Hardware: Computer with a CUDA-compatible GPU (e.g., NVIDIA Tesla V100, A100) for accelerated training

- Dataset: Curated ADMET dataset with compound structures (SMILES) and labeled endpoints (e.g., PharmaBench [9])

3. Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Featurization:

- Data Collection: Obtain a dataset such as PharmaBench, which provides over 52,000 entries across eleven ADMET properties, curated from public sources like ChEMBL using a multi-agent LLM system to standardize experimental conditions [9].

- SMILES Standardization: Standardize all molecular structures using RDKit (e.g., neutralization, removal of salts, tautomer normalization).

- Graph Representation: Convert each standardized SMILES string into a graph representation. Nodes (atoms) are featurized using vectors encoding atom type, degree, hybridization, etc. Edges (bonds) are featurized with bond type and conjugation.

- Dataset Splitting: Split the data into training, validation, and test sets using a scaffold split based on molecular Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This evaluates the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes, which is more challenging and realistic than a random split [5].

- Model Architecture Definition:

- Define a GNN architecture using a message-passing framework (e.g., Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN)).

- The model typically consists of:

- Input Layer: Takes the featurized graph.

- GNN Layers (2-4): Each layer updates node embeddings by aggregating information from neighboring nodes.

- Readout/Global Pooling Layer: Aggregates all node embeddings into a single, fixed-size graph-level representation (e.g., using mean, sum, or attention-based pooling).

- Task-Specific Head: A final fully connected neural network layer that maps the graph-level representation to the predicted ADMET endpoint (e.g., classification for toxicity, regression for solubility).

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Loss Function: For classification tasks (e.g., hepatotoxicity), use Binary Cross-Entropy loss. For regression tasks (e.g., logD), use Mean Squared Error loss. For multi-task models like MTAN-ADMET, a weighted sum of losses for each endpoint is used [8].

- Training: Train the model using the training set. Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and to avoid overfitting. Employ techniques like early stopping.

- Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Report appropriate metrics: Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and Accuracy for classification; R² and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for regression [5].

Diagram 2: GNN-based ADMET prediction workflow from SMILES input.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Modern ADMET Science

The contemporary ADMET researcher requires a combination of wet-lab reagents and computational tools. The following table details key solutions for a modern, integrated ADMET research pipeline.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for ADMET Research

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In Vitro Biological Model | Model human intestinal absorption and permeability. | Predicting oral bioavailability of new chemical entities [2] [1]. |

| hERG-Expressing Cell Line | In Vitro Biological Model | Screen for compound-induced cardiotoxicity risk. | Mandatory safety pharmacology screening for all new drug candidates [6] [5]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes/Cytosol | In Vitro Biochemical Reagent | Study Phase I and Phase II metabolic stability and metabolite identification. | Predicting metabolic clearance and potential for drug-drug interactions [4]. |

| RDKit | Computational Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, including molecule manipulation and descriptor calculation. | Standardizing chemical structures, generating molecular fingerprints and descriptors for ML models [6]. |

| PharmaBench | Computational Dataset | A comprehensive, LLM-curated benchmark set for ADMET properties with over 52,000 entries. | Training and benchmarking new AI/ML models for ADMET prediction [9]. |

| PyTorch Geometric | Computational Deep Learning Library | A library for deep learning on graphs and other irregular structures. | Building and training Graph Neural Network models for molecular property prediction [5]. |

| ADMET-AI / Chemprop | Pre-trained AI Model | Open-source platforms providing pre-trained models for rapid ADMET property prediction. | Quick, initial prioritization of compound libraries during virtual screening [6]. |

ADMET properties are critical determinants of clinical success, and their early assessment is fundamental to reducing the high attrition rates in drug development. While traditional experimental protocols provide essential validation, the field is undergoing a rapid transformation driven by AI and machine learning. The integration of sophisticated in silico models, such as Graph Neural Networks trained on comprehensive datasets like PharmaBench, into the early discovery pipeline allows researchers to proactively design molecules with optimal ADMET profiles. This synergistic approach, combining robust experimental data with powerful predictive algorithms, is key to accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

The evolution of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction represents a fundamental paradigm shift in pharmaceutical research, transitioning from reliance on costly experimental methods to sophisticated computational approaches [10] [11]. This transformation has been driven by the persistent challenge of drug candidate failure, where historically approximately 40% of failures were attributed to inadequate pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles [10] [2]. The adoption of the "fail early, fail cheap" strategy across the pharmaceutical industry has positioned in silico ADMET prediction as an indispensable component of modern drug discovery pipelines [10] [11].

This evolution has progressed through distinct phases: from early observational toxicology and animal testing, to the development of quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR), to the current era of artificial intelligence and machine learning [11]. The journey has been marked by continuous refinement of models, expansion of chemical data spaces, and integration of multidisciplinary approaches from computational chemistry, bioinformatics, and computer science [7]. Understanding this historical progression provides critical context for current methodologies and future innovations in predictive ADMET sciences.

Historical Background: From Traditional Methods to Early Computational Approaches

The Era of Traditional Experimental Assessment

Before the advent of computational methods, ADMET evaluation relied exclusively on in vitro and in vivo techniques conducted in laboratory settings [12]. These included:

- Permeability assays using Caco-2 cell lines to predict intestinal absorption

- Plasma protein binding studies through equilibrium dialysis or ultrafiltration

- Metabolic stability assessments in liver microsomes and hepatocytes

- Toxicity screening including cytotoxicity assays (MTT, LDH) and organ-specific toxicity models [12]

These experimental approaches, while valuable, presented significant limitations: they were costly, time-consuming, and low-throughput, making comprehensive evaluation of large compound libraries impractical [10] [11]. Furthermore, the high attrition rates in clinical stages persisted, with approximately 40% of failures due to toxicity and another 40% due to inadequate efficacy [11].

The Genesis of In Silico ADMET

The early 2000s witnessed the emergence of in silico ADMET prediction as pharmaceutical companies recognized the economic imperative of early liability detection [11]. Initial computational approaches included:

- Structure-based methods: Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations

- Ligand-based methods: Pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR [10] [11]

- Simple rule-based systems: Such as Lipinski's Rule of 5 for predicting oral absorption [13]

Early adoption of these computational filters led to a notable reduction in drug failures attributed to ADME issues, decreasing from 40% to 11% between 1991 and 2000 [11]. However, these early in silico tools faced considerable limitations, including dependence on limited high-resolution protein structures and challenges in predicting complex pharmacokinetic properties like clearance and volume of distribution [11].

Current State of Computational ADMET Prediction

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Modern computational ADMET prediction is dominated by machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches that have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in modeling complex biological relationships [14] [2]. Key methodologies include:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These process molecular structures as graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, enabling direct learning from molecular structure without requiring precomputed descriptors [14] [15]

- Ensemble Methods: Combining multiple models to improve prediction accuracy and robustness [15]

- Multitask Learning: Simultaneously predicting multiple ADMET endpoints to enhance generalization and efficiency [15]

- Transformer-based Models: Leveraging attention mechanisms to capture complex molecular patterns [7]

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modern ADMET Prediction Platforms

| Platform/Approach | Key Features | Number of Properties | Notable Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET-AI [15] | Graph neural network with RDKit descriptors | 41 ADMET endpoints | Highest average rank on TDC ADMET Leaderboard |

| ADMET Predictor [13] | AI/ML platform with PBPK integration | >175 properties | #1 rankings in independent peer-reviewed comparisons |

| Chemprop-RDKit [15] | Message passing neural network with molecular features | Flexible architecture | R² >0.6 for 5/10 regression tasks; AUROC >0.85 for 20/31 classification tasks |

| Attention-based GNN [14] | Processes molecular graphs from SMILES | 6 benchmark datasets | Competitive performance on solubility, lipophilicity, and CYP inhibition |

Experimental Protocols for Modern ADMET Prediction

Protocol 1: Implementing Graph Neural Networks for ADMET Prediction

Purpose: To predict key ADMET properties using graph neural networks directly from molecular structures [14]

Materials:

- Molecular structures in SMILES format

- Graph neural network framework (e.g., PyTorch Geometric, DGL)

- RDKit cheminformatics toolkit

- ADMET dataset (e.g., TDC benchmark datasets)

Procedure:

- Molecular Graph Representation: Convert SMILES strings into molecular graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [14]

- Node Feature Assignment: Encode atom-specific features (atom type, formal charge, hybridization, ring membership, chirality) using one-hot encoding [14]

- Adjacency Matrix Construction: Create multiple adjacency matrices to represent different bond types (single, double, triple, aromatic) [14]

- Model Architecture:

- Implement message passing neural network with 4-6 propagation steps

- Augment with 200 RDKit physicochemical descriptors

- Use attention mechanisms to weight important molecular substructures [14]

- Training Protocol:

- Apply five-fold cross-validation

- Use ensemble of models trained on different data splits

- Optimize using Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Validation: Evaluate performance on hold-out test sets using appropriate metrics (AUROC for classification, R² for regression)

Protocol 2: High-Throughput ADMET Screening with ADMET-AI

Purpose: Rapid screening of compound libraries for ADMET properties using pre-trained models [15]

Materials:

- Compound library in SMILES format

- ADMET-AI web server (admet.ai.greenstonebio.com) or Python package

- Reference set of approved drugs (e.g., DrugBank compounds)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare SMILES strings of query molecules (up to 1000 compounds per batch)

- Reference Selection: Choose appropriate reference set based on therapeutic area using ATC codes [15]

- Property Prediction:

- Submit compounds to ADMET-AI platform

- Generate predictions for 41 ADMET endpoints using ensemble models

- Result Interpretation:

- Review radar plot summary of key druglikeness parameters

- Examine percentile rankings relative to reference approved drugs

- Identify potential liabilities (hERG toxicity, poor solubility, etc.)

- Hit Selection: Prioritize compounds with favorable ADMET profiles based on project-specific requirements

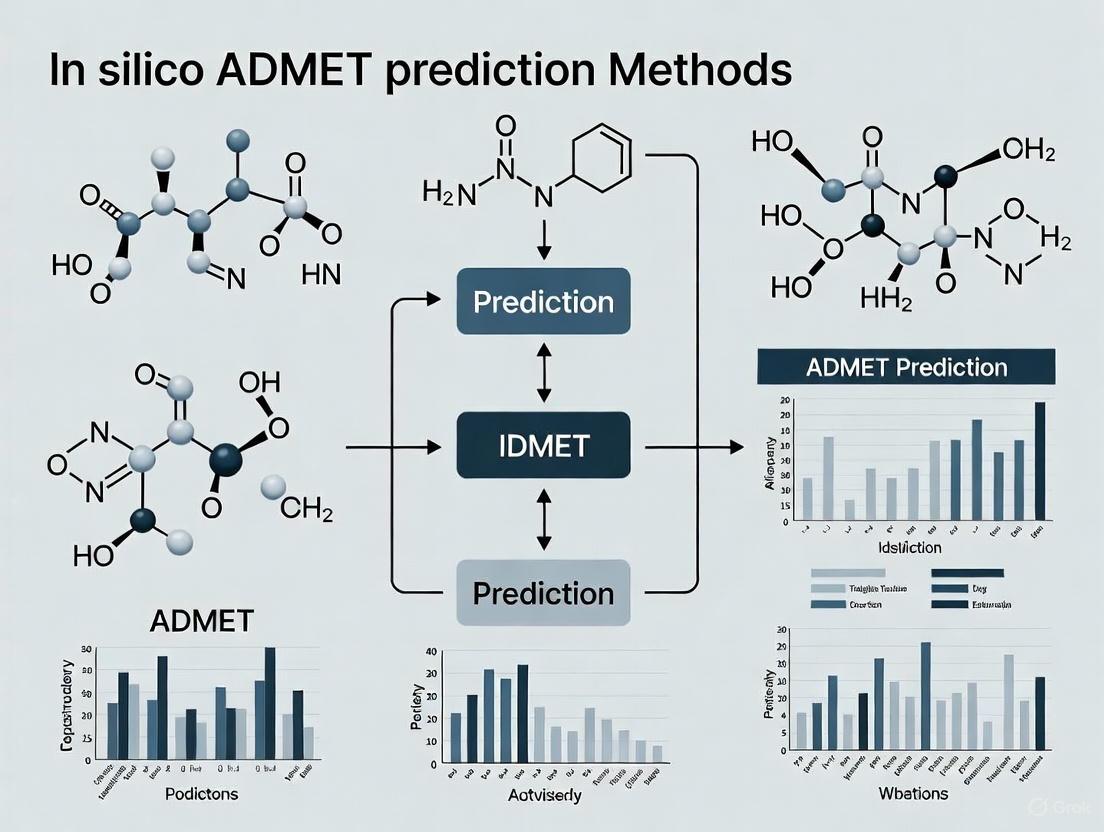

Visualization of Modern ADMET Prediction Workflow

Graph 1: GNN Workflow for ADMET Prediction. This diagram illustrates the processing of molecular structures through a graph neural network to predict ADMET properties.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Tools and Platforms for Computational ADMET Prediction

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET-AI [15] | Web server/Python package | Graph neural network for ADMET prediction | High-throughput screening of large compound libraries |

| ADMET Predictor [13] | Commercial software suite | AI/ML platform with PBPK integration | Comprehensive ADMET profiling with mechanistic interpretation |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [15] [9] | Data repository | Curated benchmark datasets for ADMET properties | Model training, validation, and benchmarking |

| RDKit [15] | Cheminformatics library | Molecular descriptor calculation and manipulation | Feature generation, molecular representation |

| PharmaBench [9] | Benchmark dataset | Enhanced ADMET data with standardized experimental conditions | Development and evaluation of predictive models |

| Chemprop [15] | Deep learning framework | Message passing neural networks for molecular property prediction | Building custom ADMET prediction models |

The historical evolution of ADMET prediction from traditional methods to computational paradigms represents a transformative journey that has fundamentally reshaped pharmaceutical research [10] [11]. The field has progressed from reliance on low-throughput experimental assays to sophisticated AI-driven platforms capable of evaluating thousands of compounds in silico [15] [13]. This paradigm shift has been catalyzed by the convergence of big data, advanced algorithms, and computational power, enabling unprecedented accuracy in predicting human pharmacokinetics and toxicity [7] [2].

Current state-of-the-art approaches, particularly graph neural networks and ensemble methods, have demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse ADMET endpoints [14] [15]. The development of comprehensive benchmarks like PharmaBench and platforms like ADMET-AI provides researchers with robust tools for accelerating drug discovery [15] [9]. As the field continues to evolve, emerging technologies including explainable AI, multi-scale modeling, and quantum computing promise to further enhance prediction accuracy and mechanistic interpretability, ultimately contributing to more efficient development of safer and more effective therapeutics [7] [2] [11].

The efficacy and safety of a potential drug are governed not only by its biological activity but also by its Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profile. In silico ADMET prediction has become an indispensable component of modern drug discovery, providing a cost-effective and rapid means to triage compounds and prioritize those with favorable pharmacokinetic properties [16]. Among the myriad of factors influencing ADMET, three key physicochemical properties stand out for their profound impact: lipophilicity, solubility, and hydrogen bonding. These properties are integral to the drug-likeness of a molecule, influencing its behavior in biological systems from initial absorption to final elimination [3]. This document details experimental and computational protocols for the accurate assessment of these properties, framed within the context of a broader thesis on advancing in silico ADMET prediction methods.

Property Analysis and Quantitative Benchmarks

The following table summarizes the key physicochemical properties, their ADMET implications, and optimal value ranges for drug-like compounds.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties, Their Roles in ADMET, and Ideal Ranges

| Property | Definition & Measurement | Primary ADMET Influence | Optimal Range for Drug-like Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity | Partition coefficient (logP) between n-octanol and water [17]. | Absorption, blood-brain barrier penetration, metabolism, toxicity [17]. | logP between 1 and 3 [17]. |

| Solubility | Water solubility, often expressed as logS. | Oral bioavailability, absorption rate [18]. | > 0.1 mg/mL (approximate, project-dependent) [18]. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Count of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA). | Membrane permeability, absorption, solubility [19]. | HBD ≤ 5, HBA ≤ 10 (as per Lipinski's Rule of 5) [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Property Determination

Protocol: Experimental Determination of Lipophilicity (logP)

Principle: Lipophilicity is quantified by the partition coefficient (logP), measuring how a compound distributes itself between two immiscible solvents: n-octanol (representing lipid membranes) and water (representing aqueous physiological environments) [17].

Materials:

- n-Octanol: Pre-saturated with water.

- Aqueous Buffer: (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4), pre-saturated with n-octanol.

- Test Compound: High-purity, accurately weighed.

- Analytical Instrument: HPLC-UV or LC-MS for compound quantification.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Equilibrate n-octanol and buffer to the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Partitioning: Add a known concentration of the test compound to a mixture of n-octanol and buffer in a sealed vial. Shake vigorously for 24 hours to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Separation: Allow the phases to separate completely. Centrifuge if necessary to achieve a clean phase separation.

- Analysis: Carefully sample from both the n-octanol and aqueous phases. Dilute samples as needed and quantify the concentration of the compound in each phase using a calibrated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV).

- Calculation: Calculate logP using the formula: logP = log₁₀ (Concentrationinoctanol / Concentrationinwater).

Protocol: Kinetic Aqueous Solubility Measurement

Principle: This protocol determines the concentration of a compound in a saturated aqueous solution after a fixed equilibration time, providing a "kinetic" solubility relevant to early drug discovery.

Materials:

- Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO): High-quality stock for compound dissolution.

- Aqueous Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4).

- Test Compound: As a concentrated DMSO stock solution.

- Equipment: Microtiter plates, multi-channel pipettes, plate shaker, and a plate reader (e.g., UV-vis spectrophotometer or Nephelometer).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the DMSO stock of the test compound into the aqueous buffer to achieve the final desired concentration range (typical final DMSO concentration ≤ 1% v/v).

- Equilibration: Shake the plate for a defined period (e.g., 1-24 hours) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Analysis:

- Nephelometry: Measure the turbidity of the solution. A clear solution indicates dissolution, while a cloudy solution indicates precipitation.

- UV-vis Analysis: Centrifuge the plate to pellet any precipitate. Measure the concentration of the compound in the supernatant via UV absorbance against a standard calibration curve.

- Calculation: The kinetic solubility is the highest concentration at which the compound remains fully dissolved in solution.

Protocol: Assessment of Hydrogen Bonding Capacity

Principle: Hydrogen bonding potential is typically assessed computationally or by counting hydrogen bond donors (HBD; e.g., OH, NH groups) and acceptors (HBA; e.g., O, N atoms) from the molecular structure [19].

Procedure:

- Structural Input: Use a canonical SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) string or 2D/3D molecular structure file as the starting point [21].

- Automated Counting:

- HBD Count: Algorithmically count all atoms (typically O-H and N-H) that can donate a hydrogen bond.

- HBA Count: Algorithmically count all oxygen and nitrogen atoms that can accept a hydrogen bond.

- Computational Analysis (Advanced): For a more quantitative assessment, use quantum chemical calculations (e.g., Gaussian '09 software at the wB97XD/6-311++G(d,p) level) to analyze the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface, which visually identifies electron-rich (HBA) and electron-poor (HBD) regions [19].

In SilicoPrediction Workflows

The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for predicting ADMET properties, integrating the key physicochemical properties.

Protocol: Machine Learning Prediction of Lipophilicity (logP)

Principle: This protocol uses deep learning models in conjunction with modern molecular featurization techniques like Mol2vec to predict logP directly from molecular structure [17] [21].

Materials & Software:

- Dataset: Lipophilicity dataset (e.g., from MoleculeNet/DeepChem) containing SMILES strings and experimental logP values [17].

- Software: Python with TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch, and DeepChem library.

- Featurizer: Mol2vec for generating 300-dimensional molecular embeddings [17].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load the dataset and preprocess SMILES strings. Split data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80/10/10).

- Featurization: Convert SMILES strings into numerical representations using Mol2vec. This treats molecular substructures as "words" and the molecule as a "sentence," generating a dense vector for each molecule [17] [21].

- Model Training:

- MLP Model: Construct a Multi-Layer Perceptron with multiple fully connected (Dense) layers.

- LSTM/1D-CNN Model: For a sequence of substructure vectors, use Long Short-Term Memory networks or 1D Convolutional Neural Networks to capture contextual information.

- Model Evaluation: Train the model using mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. Evaluate performance on the test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) [17].

Protocol: QSAR Modeling for Aqueous Solubility

Principle: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models correlate structural descriptors of compounds with their experimental solubility to predict the solubility of new compounds [18].

Materials & Software:

- Dataset: Curated dataset of drug-like compounds with experimental solubility (e.g., from PHYSPROP database) [18].

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, RDKit.

- Descriptors: A set of relevant molecular descriptors (e.g., logP, molecular weight, topological polar surface area, hydrogen bond counts).

Procedure:

- Data Curation & Filtering: Apply drug-likeness filters (e.g., based on properties from the FDAMDD database) to define a relevant chemical space [18].

- Descriptor Calculation & Selection: Compute molecular descriptors for all compounds. Use feature selection algorithms (e.g., GBFS - Gradient-Boosted Feature Selection) to identify the most relevant descriptors, reducing multicollinearity [21].

- Model Building & Validation:

- Train a model (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on a training subset of the data.

- Validate the model's classification or regression accuracy on a separate test set and with external validation sets to ensure reliability [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for In Silico ADMET Profiling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in ADMET |

|---|---|---|

| MoleculeNet/DeepChem | Software Library & Benchmark | Provides standardized datasets (e.g., lipophilicity) and implementations of molecular machine learning models [17]. |

| Mol2vec | Molecular Descriptor | Generates unsupervised learned vector embeddings for molecules from substructures, useful for ML models [17] [21]. |

| Gaussian '09 | Quantum Chemistry Software | Performs quantum chemical calculations (e.g., DFT) to derive electronic properties, MEP surfaces, and hydrogen bonding energies [19]. |

| Schrodinger Suite | Molecular Modeling Platform | Used for protein preparation, molecular docking, and MM-GBSA calculations in integrated drug discovery workflows [20]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Performs molecular docking to predict protein-ligand binding modes and affinities [20]. |

| SwissParam | Web Server | Generates topologies and parameters for small molecules for use in molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., with GROMACS) [19]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and handles chemical data for QSAR modeling [21]. |

Lipophilicity, solubility, and hydrogen bonding capacity form the foundational triad of physicochemical properties that dictate the ADMET profile and ultimate success of drug candidates. The experimental and computational protocols detailed herein provide a standardized framework for their rigorous characterization. The integration of modern machine learning techniques, such as deep learning models with Mol2vec featurization and robust QSAR modeling, into the drug discovery pipeline enables the rapid and cost-effective in silico prediction of these critical properties [17] [3] [21]. By systematically applying these protocols for early-stage profiling, researchers can effectively de-risk the drug development process, prioritize compounds with a higher probability of clinical success, and accelerate the journey of delivering new therapeutics to patients.

The optimization of a drug candidate's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profile represents a critical bottleneck in drug discovery pipelines. Unlike binding affinity data, ADME data is largely obtained from in vivo studies using animal models or clinical trials, making it costly and labor-intensive to generate [22]. This scarcity of high-quality experimental data has propelled the development of in silico predictive models as an essential component of modern pharmaceutical research. Molecular descriptors—numerical representations of a compound's structural and physicochemical properties—serve as the foundational input for these quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models. Within the context of a broader thesis on in silico ADMET prediction methods, this application note provides a detailed overview of descriptor systems, organized by dimensionality (1D, 2D, and 3D), and presents standardized protocols for their application in predictive toxicology and pharmacokinetics.

The reliability of any predictive model is inherently tied to the quality and consistency of its training data. Recent analyses of public ADME datasets have uncovered significant distributional misalignments and annotation discrepancies between benchmark sources [22]. Such inconsistencies can introduce noise and ultimately degrade model performance, highlighting the importance of rigorous data consistency assessment prior to modeling.

Classification and Applications of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors are mathematically derived quantities that encode molecular information into a numerical format. The following table summarizes the primary descriptor classes used in ADMET prediction.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors in ADMET Prediction

| Descriptor Class | Description | Example Descriptors | Primary ADMET Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Derived from molecular formula; do not require structural information. | Molecular weight, atom count, rotatable bond count, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors. | Preliminary solubility prediction, Rule of 5 screening, intestinal absorption. |

| 2D Descriptors | Based on 2D molecular structure (connectivity). | Topological indices, molecular connectivity indices, ECFP4 fingerprints, graph-based descriptors. | Metabolic stability, CYP450 inhibition, toxicity (e.g., hERG), plasma protein binding. |

| 3D Descriptors | Require 3D molecular geometry/conformation. | Molecular surface area, polar surface area (TPSA), volume descriptors, 3D-MoRSE descriptors. | Tissue penetration (BBB), binding affinity, mechanistic toxicity endpoints. |

One-Dimensional (1D) Descriptors

1D descriptors, also known as constitutional descriptors, are the simplest type. They are calculated directly from the molecular formula and composition, requiring no structural information. Their computational efficiency makes them ideal for high-throughput virtual screening of large compound libraries in early discovery stages, such as applying Lipinski's Rule of 5 to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of oral bioavailability [7].

Two-Dimensional (2D) Descriptors

2D descriptors encode information about the connectivity of atoms within a molecule. This class includes topological descriptors and molecular fingerprints, which are particularly powerful for similarity searching and machine learning models. Graph neural networks, for instance, operate directly on 2D graph representations of molecules to predict ADMET properties [7] [23]. Tools like RDKit are commonly used to calculate a wide array of 1D and 2D descriptors on the fly [22].

Three-Dimensional (3D) Descriptors

3D descriptors capture spatial information derived from a molecule's three-dimensional geometry. These descriptors are sensitive to molecular conformation and are crucial for modeling interactions that depend on steric and electrostatic complementarity, such as binding to enzyme active sites or receptors. The calculation of these descriptors is computationally intensive but can provide critical insights for predicting properties like herg channel blockage, which is strongly influenced by 3D structure [23].

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Calculation and Modeling

Protocol 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing for ADMET Modeling

Purpose: To ensure data quality and consistency prior to descriptor calculation and model training, a critical step given the prevalence of dataset discrepancies [22].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Input Data: Molecular structures (e.g., SMILES strings, SDF files) with associated experimental ADMET endpoints.

- Software: Python with libraries such as RDKit or KNIME.

Procedure:

- Structure Standardization: Standardize all molecular structures using RDKit. This includes neutralizing charges, removing salts, and generating canonical SMILES.

- Duplicate Removal: Identify and remove duplicate molecules based on canonical SMILES. For duplicates with conflicting property annotations, apply statistical tests (e.g., Grubbs' test) to identify and exclude outliers [22].

- Data Consistency Assessment: Use a tool like AssayInspector to perform a systematic data consistency assessment [22]. This includes:

- Generating descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, quartiles) for regression endpoints.

- Performing statistical comparisons of endpoint distributions between datasets using the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test.

- Visualizing chemical space coverage using UMAP to identify distributional misalignments.

- Data Splitting: Split the cleaned dataset into training and test sets. Use scaffold splitting to assess the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes.

Protocol 2: Calculation of Multi-Dimensional Descriptors

Purpose: To generate a comprehensive set of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors for subsequent model building.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 2 for a detailed list of essential software and their functions.

- Input: Cleaned and standardized molecular structures from Protocol 1.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Descriptor Calculation

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function in Descriptor Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates a broad range of 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors; generates molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) [22]. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial Software | Provides advanced tools for molecular mechanics calculations, conformational search, and 3D descriptor generation. |

| Open3DALIGN | Open-source Tool | Handles 3D molecular alignment and calculates 3D descriptors such as 3D-MoRSE and WHIM. |

| Python SciPy Stack | Programming Environment | Supports statistical analysis, data transformation, and numerical computations during descriptor preprocessing. |

Procedure:

- 1D Descriptor Calculation: Using RDKit, compute constitutional descriptors. Key descriptors to extract include: molecular weight, number of heavy atoms, number of rotatable bonds, number of hydrogen bond donors, and number of hydrogen bond acceptors.

- 2D Descriptor Calculation:

- Topological Descriptors: Calculate descriptors such as topological polar surface area (TPSA) and molecular connectivity indices using RDKit.

- Molecular Fingerprints: Generate ECFP4 (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints) or other fingerprint types to capture circular substructures in the molecule [22].

- 3D Descriptor Calculation:

- Conformer Generation: Use RDKit's distance geometry methods (or a more advanced tool like OMEGA from Schrödinger) to generate an ensemble of low-energy 3D conformers for each molecule.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a quick geometry optimization on the generated conformers using the MMFF94 force field.

- Descriptor Computation: From the lowest-energy conformer, compute 3D descriptors such as radius of gyration, principal moments of inertia, and molecular surface area descriptors.

Protocol 3: Building a Predictive ADMET Model with AI

Purpose: To integrate calculated descriptors into a machine learning or deep learning model for predicting a specific ADMET endpoint.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch; platforms like DeepTox for toxicity prediction [7].

Procedure:

- Feature Preprocessing: Standardize all descriptor values (e.g., scale to zero mean and unit variance) to ensure model stability.

- Feature Selection: Reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting by selecting the most relevant features. Methods include:

- Variance Threshold: Remove low-variance descriptors.

- Univariate Feature Selection: Select the top-k features based on statistical tests (e.g., f-regression).

- Recursive Feature Elimination: Iteratively remove the least important features using a model-based approach.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose an appropriate algorithm based on data size and complexity. For structured descriptor data, Random Forests or Support Vector Machines are robust choices. For graph-based data, Graph Neural Networks are state-of-the-art [7].

- Training: Train the model on the preprocessed training set.

- Validation: Evaluate model performance on the held-out test set using metrics relevant to the task (e.g., ROC-AUC for classification, RMSE for regression). Use cross-validation to ensure robustness.

- Model Interpretation: Use techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or model-specific feature importance (e.g., from Random Forest) to interpret the model's predictions and identify which molecular descriptors are most influential.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The predictive performance of models can vary significantly based on the type of descriptors used and the specific ADMET property being modeled. The table below provides a comparative summary based on literature benchmarks.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Descriptor Types in ADMET Prediction

| ADMET Property | Descriptor Type | Typical Model Performance (Metric) | Key Advantages | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | 1D & 2D Descriptors | ~0.75-0.85 (R²) [22] | Fast calculation, suitable for high-throughput screening. | May miss complex 3D solvation effects. |

| hERG Toxicity | 2D & 3D Descriptors | ~0.80-0.90 (AUC) [23] | 3D descriptors capture steric and electrostatic blocking of ion channel. | Computationally expensive; conformationally dependent. |

| CYP450 Inhibition | 2D Fingerprints (ECFP) | ~0.85-0.95 (AUC) [7] | Excellent for recognizing key substructures (pharmacophores). | Can be less interpretable than simpler descriptors. |

| Human Half-Life | Integrated 1D/2D/3D | Varies with data quality [22] | Comprehensive representation of molecular properties. | High dimensionality requires careful feature selection. |

The integration of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptor systems provides a powerful framework for building robust in silico ADMET prediction models. The choice of descriptor is not one-size-fits-all; it must be tailored to the specific biological endpoint, the available computational resources, and the stage of the drug discovery pipeline. While 1D and 2D descriptors offer speed and efficiency for early-stage virtual screening, 3D descriptors can provide critical insights for mechanistically complex endpoints like hERG toxicity.

A central challenge in this field, however, is data quality and consistency. The presence of significant misalignments between public ADMET datasets underscores the necessity of rigorous data curation and assessment protocols, such as those enabled by the AssayInspector tool, before model development [22]. Furthermore, the issue of scarce molecular annotations in real-world scenarios is driving research into Few-shot Molecular Property Prediction (FSMPP) methods, which aim to learn from only a handful of labeled examples [23].

Future directions in this field point towards the increased use of hybrid AI-quantum computing frameworks and the integration of multi-omics data to create more holistic and predictive models of drug behavior in vivo [7]. As these computational methods continue to mature, their role in de-risking the drug development process and accelerating the delivery of safer, more effective therapeutics will only become more pronounced.

The high attrition rate of drug candidates represents a significant challenge for the pharmaceutical sector, with approximately 90% of failures in the last decade attributed to poor pharmacokinetic profiles, including lack of clinical efficacy (40-50%), unmanaged toxicity (30%), and inadequate drug-like properties (10-15%) [24]. The 'Fail Early, Fail Cheap' strategy addresses this problem by emphasizing early identification of compounds with suboptimal absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties before substantial resources are invested in later development stages [25]. This approach is fundamentally rooted in engineering principles where the cost of repairing an error increases exponentially as a product moves through development phases—from design ($1) to prototyping ($10) to production ($100) and finally to market release ($1000) [26]. In silico ADMET prediction tools have emerged as transformative technologies that enable researchers to apply this strategy effectively during early drug discovery, providing computational estimates of critical pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties to prioritize compounds with the highest probability of clinical success [27] [28].

Economic Rationale for Early ADMET Screening

The pharmaceutical industry faces a fundamental economic challenge: the later a compound fails in the development process, the more significant the financial loss. The 'Fail Early, Fail Cheap' paradigm provides a framework for mitigating these losses through strategic early intervention. The core principle states that the cost of fixing errors escalates dramatically as a compound progresses through development stages [26]. This economic reality makes early detection of problematic ADMET properties critically important for resource allocation and portfolio management.

The 'Fail Early, Fail Cheap' concept should be properly understood as 'Learn Fast, Learn Cheap' [29]. The goal is not merely to identify failures, but to design careful experiments that test specific assumptions about a compound's behavior, generating valuable data to inform the next iteration of compound design. A well-executed experiment that rejects a hypothesis about a compound's metabolic stability is not a failure but a successful learning event that prevents wasted resources on unsuitable candidates [29]. This learning-oriented approach encourages smart risk-taking and offensive rather than defensive research cultures [30].

Table 1: Economic Impact of Early vs. Late-Stage Failure in Drug Development

| Development Stage | Relative Cost of Failure | Primary Failure Causes Addressable by Early ADMET Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery/Design | 1x [26] | Poor physicochemical properties, structural alerts for toxicity, inadequate target binding |

| Preclinical Testing | 10x [26] | Poor permeability, metabolic instability, toxicity in cellular models, inadequate PK/PD |

| Clinical Phase I | 100x [26] | Human toxicity (e.g., hERG inhibition), unfavorable human pharmacokinetics, safety margins |

| Clinical Phase II/III | 1000x [26] | Lack of efficacy in humans, chronic toxicity findings, drug-drug interactions |

| Post-Marketing | >10,000x [26] | Rare adverse events, human metabolites with unexpected toxicity |

Available ADMET Prediction Tools and Databases

The implementation of early ADMET screening requires access to robust predictive tools and high-quality data. Researchers can select from commercial software, free web servers, and curated public databases, each offering different advantages depending on research needs, resources, and required level of accuracy.

Commercial and Free ADMET Prediction Platforms

Commercial software platforms like ADMET Predictor provide comprehensive solutions, predicting over 175 ADMET properties including aqueous solubility profiles, logD curves, pKa, CYP metabolism outcomes, and key toxicity endpoints like Ames mutagenicity and drug-induced liver injury (DILI) [13]. These platforms often incorporate AI/ML capabilities, extensive data analysis tools, and integration with PBPK modeling software like GastroPlus [13]. For academic researchers and small biotech companies with limited budgets, numerous free web servers provide valuable ADMET predictions. These platforms vary significantly in their coverage of ADMET parameters, mathematical models employed, and usability features [24].

Table 2: Comparison of Selected ADMET Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Access Type | Key Predictions | Special Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [13] | Commercial License | >175 properties including solubility vs. pH, logD, pKa, CYP metabolism, DILI, Ames | Integrated HTPK simulations, AI-driven design, custom model building | Cost may be prohibitive for some academics/small companies |

| ADMETlab [24] | Free Web Server | Parameters from all ADMET categories | Broad coverage, no registration required | May lack specialized metabolism predictions |

| pkCSM [24] | Free Web Server | PK and toxicity properties | Graph-based signatures, user-friendly | Limited to specific property types |

| admetSAR [24] | Free Web Server | Comprehensive ADMET parameters | Large database, batch upload | Calculation time may be long for large compound sets |

| MetaTox [24] | Free Web Server | Metabolic properties only | Specialized in metabolism prediction | Narrow focus requires multiple tools for full profile |

| MolGpka [24] | Free Web Server | pKa prediction | Graph-convolutional neural network | Only predicts pKa |

Critical ADMET Databases and Benchmarks

High-quality, curated datasets are fundamental for developing reliable predictive models. PharmaBench represents a significant advancement, addressing limitations of previous benchmarks like small size and lack of representation of compounds relevant to drug discovery projects [9]. This comprehensive benchmark set comprises eleven ADMET datasets and 52,482 entries, created through a sophisticated data mining system using large language models (LLMs) to identify experimental conditions within 14,401 bioassays [9]. Other essential data resources include ChEMBL, PubChem, and BindingDB, which provide publicly accessible screening results crucial for model training and validation [9] [27].

Experimental Protocols for In Silico ADMET Screening

Protocol 1: Comprehensive ADMET Profiling Using Free Web Tools

Objective: To obtain a complete initial ADMET profile for novel compounds using freely accessible web servers.

Materials and Methods:

- Compounds: Structures in SMILES, SDF, or MOL2 format

- Software: Access to multiple free web servers (e.g., ADMETlab, pkCSM, admetSAR)

- Computing: Standard computer with internet connection

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Generate and optimize 3D structures of compounds using cheminformatics software like RDKit or OpenBabel.

- Property Calculation with ADMETlab:

- Navigate to https://admet.scbdd.com/

- Input structures via SMILES strings or file upload

- Select all relevant ADMET parameters for prediction

- Submit job and download results in table format

- Toxicity and PK Screening with pkCSM:

- Access the pkCSM web server

- Input the same compound structures

- Focus on toxicity endpoints (Ames, hERG) and pharmacokinetic parameters

- Compare results with ADMETlab outputs for consistency

- Data Integration and Analysis:

- Compile results from all servers into a unified spreadsheet

- Flag compounds with potential ADMET issues based on established thresholds

- Prioritize compounds for further experimental validation

Expected Output: A comprehensive table of predicted ADMET properties for each compound, with flags for potential liabilities including poor solubility, low permeability, metabolic instability, or toxicity concerns.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based ADMET Modeling with PharmaBench

Objective: To build custom predictive ADMET models using the PharmaBench dataset and machine learning algorithms.

Materials and Methods:

- Data: PharmaBench dataset (available through official channels)

- Software: Python 3.12.2 with pandas, scikit-learn, RDKit, NumPy

- Computing: Computer with sufficient RAM for dataset size

Procedure:

- Environment Setup:

- Create a Python virtual environment using Conda

- Install required packages: pandas 2.2.1, NumPy 1.26.4, scikit-learn 1.4.1, rdkit 2023.9.5

- Data Loading and Preprocessing:

- Load the PharmaBench dataset using pandas

- Handle missing values and outliers appropriately

- Generate molecular descriptors or fingerprints using RDKit

- Feature Selection:

- Apply correlation-based feature selection (CFS) to identify fundamental molecular descriptors

- Use wrapper methods or embedded methods for optimal feature subset identification

- Reduce dimensionality while maintaining predictive power

- Model Training and Validation:

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using random and scaffold splitting

- Train multiple ML algorithms (Random Forest, XGBoost, Neural Networks)

- Optimize hyperparameters using cross-validation

- Evaluate models using appropriate metrics (AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision-recall)

Expected Output: Custom-trained machine learning models for specific ADMET endpoints with documented performance characteristics and applicability domains.

Early ADMET Screening Workflow

Implementation Framework and Risk Assessment

Successful implementation of early ADMET screening requires access to specific computational tools and data resources. This toolkit enables researchers to efficiently predict and evaluate critical properties that determine a compound's likelihood of success.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ADMET Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [13] | Commercial Software Platform | Predicts >175 ADMET properties using AI/ML models | Solubility vs. pH profiles, metabolite prediction, toxicity risk assessment |

| PharmaBench [9] | Curated Dataset | Benchmark set for ADMET model development/evaluation | Training custom ML models, comparing algorithm performance |

| RDKit [9] | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Calculates molecular descriptors, handles chemical data | Structure preprocessing, fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation |

| admetSAR [24] | Free Web Server | Predicts comprehensive ADMET parameters | Initial screening of compound libraries, academic research |

| MolGpka [24] | Free Web Server | Predicts pKa using neural networks | Ionization state prediction, pH-dependent property modeling |

| CYP Inhibition Models [27] | Specialized AI Models | Predicts cytochrome P450 inhibition | Drug-drug interaction risk assessment, metabolic stability optimization |

ADMET Risk Quantification Framework

Beyond individual property predictions, comprehensive risk assessment requires integrated scoring systems. The ADMET Risk framework extends Lipinski's Rule of 5 by incorporating "soft" thresholds for multiple calculated and predicted properties that represent potential obstacles to successful development of orally bioavailable drugs [13]. This system calculates an overall ADMET_Risk score composed of:

- Absn_Risk: Risk of low fraction absorbed

- CYP_Risk: Risk of high CYP metabolism

- TOX_Risk: Toxicity-related risks

The framework uses threshold regions where predictions falling between start and end values contribute fractional amounts to the Risk Score, providing a more nuanced assessment than binary pass/fail criteria [13].

ADMET Risk Assessment Pathway

The implementation of a 'Fail Early, Fail Cheap' strategy through early and comprehensive in silico ADMET screening represents a paradigm shift in modern drug discovery. By leveraging increasingly sophisticated computational tools, machine learning models, and curated benchmark datasets, researchers can identify potential pharmacokinetic and toxicological liabilities before committing substantial resources to experimental work. This approach transforms drug discovery from a high-risk gamble to a more efficient, knowledge-driven process focused on learning and optimization. As ADMET prediction technologies continue to evolve through advances in artificial intelligence and data availability, their integration into standard drug discovery workflows will become increasingly essential for improving the success rate of compounds transitioning from bench to bedside.

The optimization of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical bottleneck in modern drug discovery. High attrition rates due to unfavorable pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles necessitate advanced predictive modeling from the earliest stages of development [2]. The strategic selection between global and local machine learning models has emerged as a pivotal decision point for research teams, with significant implications for resource allocation, compound optimization, and ultimately, clinical success rates.

Global models, trained on extensive and diverse chemical datasets, aim for broad applicability across the chemical space, while local models focus on specific chemical series or discovery projects to capture nuanced structure-activity relationships [31]. Evidence from recent blinded competitions indicates that integrating additional ADMET data meaningfully improves performance over local models alone, highlighting the value of broader chemical context [32]. However, the performance of modeling approaches varies significantly across different drug discovery programs, limiting the generalizability of conclusions drawn from any single program [32].

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Performance Evaluation

Key Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Table 1: Comparative performance of global versus local models across ADMET endpoints

| ADMET Endpoint | Global Model MAE | Local Model MAE | Performance Differential | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomal Stability | Varies by program (4-24%) | Varies by program | Fingerprint models lower MAE in 8/10 programs [32] | Program-specific performance variations observed |

| Kinetic Solubility (PBS @ pH 7.4) | Close to lowest MAE on ASAP dataset | Higher MAE | Significant | Dataset clustering near assay ceiling affects ranking [32] |

| MDR1-MDCK Permeability | By far highest Spearman r | Lower Spearman r | Substantial | Test series behavior drives high performance [32] |

| General ADMET Properties | 23% lower error vs. local models [32] | 41% higher error vs. global models [32] | Significant | From Polaris-ASAP competition results |

Application to Novel Therapeutic Modalities

Table 2: Performance of global models on Targeted Protein Degraders (TPDs)

| Property | All Modalities MAE | Molecular Glues MAE | Heterobifunctionals MAE | Misclassification Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Permeability | ~0.22 | Lower errors | Higher errors | Glues: <4%, Heterobifunctionals: <15% [31] |

| CYP3A4 Inhibition | ~0.24 | Lower errors | Higher errors | Glues: <4%, Heterobifunctionals: <15% [31] |

| Metabolic Clearance | ~0.26 | Lower errors | Higher errors | Glues: <4%, Heterobifunctionals: <15% [31] |

| Lipophilicity (LogD) | 0.33 | ~0.35 | ~0.39 | All modalities: 0.8-8.1% [31] |

Recent comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that global ML models perform comparably on TPDs versus traditional small molecules, despite TPDs' structural complexity [31]. For permeability, CYP3A4 inhibition, and metabolic clearance, misclassification errors into high and low risk categories remain below 4% for molecular glues and under 15% for heterobifunctionals, supporting global models' applicability to emerging modalities [31].

Experimental Protocols for Model Implementation

Protocol 1: Developing Program-Specific Local Models

Objective: Construct and validate local ADMET models tailored to specific chemical series within a discovery program.

Materials:

- RDKit Cheminformatics Toolkit: Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints [33]

- Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC)*: Access benchmark datasets and evaluation frameworks [34]

- Scikit-learn or DeepChem: Implement machine learning algorithms [27]

Methodology:

- Data Curation and Cleaning

- Apply standardized cleaning protocols: remove inorganic salts, extract organic parent compounds from salts, adjust tautomers, canonicalize SMILES strings [33]

- De-duplicate records, keeping first entry if target values are consistent (exactly same for binary tasks; within 20% IQR for regression) [33]

- Perform visual inspection of cleaned datasets using tools like DataWarrior [33]

Chronological Splitting

- Separate data using temporal splits: first 75% for training/validation, latest 25% for testing [32]

- Preserve chemical series integrity across splits to mimic real-world forecasting scenarios

Model Training with Classical Representations

Performance Validation

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning Global Models for Program Application

Objective: Adapt pre-trained global models to specific discovery programs using transfer learning techniques.

Materials:

- MSformer-ADMET or Similar Framework: Transformer-based architecture pretrained on large molecular datasets [34]

- Program-Specific ADMET Data*: Internal assay results for target chemical series

- Deep Learning Framework: PyTorch or TensorFlow for model fine-tuning

Methodology:

- Base Model Selection

- Choose pretrained models with demonstrated ADMET prediction capability (e.g., MSformer-ADMET fine-tuned on 22 TDC tasks) [34]

- Verify model architecture compatibility with available computational resources

Representation Alignment

- Convert program compounds into model-compatible representations (e.g., SMILES, molecular graphs, or fragment-based meta-structures)

- For MSformer-ADMET: fragment molecules using pretrained meta-structure library [34]

Transfer Learning Implementation

- Replace final prediction layer with program-specific output layer

- Employ gradual unfreezing strategies: initially freeze early layers, fine-tune later layers

- Utilize multi-task learning where possible to leverage correlations between ADMET endpoints [31]

Validation and Applicability Assessment

- Compare fine-tuned global model performance against local baselines

- Analyze attention mechanisms to identify key structural fragments influencing predictions [34]

- Establish applicability domain through distance metrics to training chemical space

Decision Framework for Model Selection

The choice between global and local modeling approaches depends on multiple factors, including program stage, data availability, and chemical space characteristics.

Program Stage Considerations

- Early Discovery: Global models are preferable when program-specific data is limited, leveraging broad chemical knowledge to guide initial design [31]

- Lead Optimization: Local models or fine-tuned global models become advantageous as sufficient program data accumulates (>150 compounds), capturing series-specific patterns [32]

- Development Candidate Selection: Hybrid approaches combining global model robustness with local model precision provide optimal prediction accuracy [32]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools for ADMET model development

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation | Local model feature engineering [33] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Benchmarking Platform | Curated ADMET datasets and evaluation standards | Model validation and benchmarking [34] [33] |

| MSformer-ADMET | Transformer Framework | Fragment-based molecular representation learning | Global model pre-training and fine-tuning [34] |

| Chemprop | Message Passing Neural Network | Molecular property prediction with graph representations | Both global and local model implementation [33] [31] |

| OpenADMET Datasets | Experimental Data Repository | High-quality, consistently generated ADMET measurements | Training data for specialized model development [35] |

The strategic integration of global and local modeling approaches represents a paradigm shift in ADMET optimization. Evidence indicates that models incorporating additional ADMET data achieve superior performance, yet the optimal approach remains program-dependent [32]. Emerging methodologies such as transfer learning and multi-task learning demonstrate promise for enhancing model generalizability while maintaining program-specific accuracy [34] [31].

Future advancements will likely focus on improved model interpretability, uncertainty quantification, and seamless integration into automated design-make-test-analyze cycles [35]. The research community's growing commitment to open data initiatives, such as OpenADMET, will further accelerate progress by providing the high-quality, standardized datasets essential for robust model development and validation [35].

Computational Methodologies and Practical Applications in ADMET Prediction

Molecular modeling represents a cornerstone of modern in silico prediction methods, enabling researchers to study the interactions between potential drug compounds and biological macromolecules at an atomic level. Within the context of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction, these structure-based approaches provide critical insights into pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties early in the drug discovery pipeline. The fundamental premise of structure-based molecular modeling rests on utilizing the three-dimensional structures of proteins relevant to ADMET processes, such as metabolic enzymes, transporters, and receptors, to predict compound behavior in vivo [10]. This approach stands in contrast to ligand-based methods that rely solely on compound characteristics without direct reference to protein structure.

The application of molecular modeling to ADMET prediction addresses a critical need in pharmaceutical development, where undesirable pharmacokinetics and toxicity remain significant reasons for failure in costly late-stage development [10]. By employing structure-based methods early in discovery, researchers can prioritize compounds with optimal ADMET characteristics, adhering to the "fail early, fail cheap" strategy widely adopted by pharmaceutical companies [10]. These computational approaches have gained prominence alongside increasing availability of protein structures and advances in computing power, enabling more accurate simulations of the physical interactions governing drug disposition and safety.

Fundamental Methodologies and Approaches

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking serves as a fundamental structure-based technique for predicting the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target macromolecule (receptor). This method enables researchers to rapidly screen large compound libraries through high-throughput virtual screening, prioritizing candidates based on predicted binding affinity and complementarity to the binding site [36] [37]. The docking process typically involves sampling possible ligand conformations and orientations within the binding site, followed by scoring each pose to estimate binding strength.

In practice, molecular docking has been successfully applied to identify compounds targeting specific ADMET-related proteins. For instance, in a study targeting the human αβIII tubulin isotype, researchers employed docking-based virtual screening of 89,399 natural compounds from the ZINC database, selecting the top 1,000 hits based on binding energy for further investigation [36]. Such applications demonstrate how docking facilitates the efficient exploration of chemical space while focusing experimental resources on the most promising candidates.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a more sophisticated approach by simulating the time-dependent behavior of molecular systems according to Newton's equations of motion. Unlike docking, which typically treats proteins as rigid entities, MD accounts for protein flexibility and solvent effects, offering insights into binding kinetics, conformational changes, and stability of protein-ligand complexes [36] [10]. These simulations calculate the trajectories of atoms over time, revealing dynamic processes critical to understanding ADMET properties.

The value of MD simulations in ADMET prediction is exemplified in studies evaluating potential tubulin inhibitors, where researchers analyzed RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation), RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation), Rg (Radius of Gyration), and SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area) to assess how candidate compounds influenced the structural stability of the αβIII-tubulin heterodimer compared to the apo form [36]. Such analyses provide deep insights into compound effects on protein structure and dynamics, informing optimization efforts to improve selectivity and reduce toxicity.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

Free Energy Perturbation represents a more computationally intensive approach that provides quantitative predictions of binding affinities by simulating the thermodynamic transformation between related ligands. FEP methods have gained prominence for structure-based affinity prediction because they directly model physical interactions between proteins and ligands at the atomic level [38]. These approaches are particularly valuable for lead optimization, where small chemical modifications can significantly impact potency and selectivity.

Despite their power, FEP methods face limitations including high computational cost, the requirement for high-quality protein structures, and restricted applicability to structural changes around a reference ligand [38]. Additionally, target-to-target variation in prediction accuracy remains a challenge. Nevertheless, ongoing methodological research continues to enhance FEP capabilities, with promising developments in absolute binding free energy calculations that would enable affinity predictions without requiring a closely related reference ligand [38].

Quantum Mechanics (QM) Calculations

Quantum mechanics calculations employ first-principles approaches to electronically describe molecular systems, providing unparalleled accuracy for studying chemical reactions, including metabolic transformations relevant to ADMET properties [10]. QM methods are particularly valuable for predicting bond cleavage processes involved in drug metabolism and for accurately describing electronic properties that influence protein-ligand interactions [10].

Common QM approaches applied in ADMET prediction include ab initio (Hartree-Fock), semiempirical (AM1 and PM3), and density functional theory (DFT) methods [10]. For example, researchers have utilized DFT to study the absorption profiles of sulfonamide Schiff bases and to evaluate the metabolic selectivity of antipsychotic thioridazine by CYP450 2D6 [10]. These applications demonstrate how QM methods can reveal atomic-level insights critical for understanding and predicting metabolic fate and associated toxicity concerns.

Application to ADMET Properties