High-Throughput Screening Assay Development: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Validation

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in developing robust high-throughput screening (HTS) assays.

High-Throughput Screening Assay Development: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in developing robust high-throughput screening (HTS) assays. It covers the foundational principles of HTS, including automation, miniaturization, and core components. The guide delves into methodological choices between target-based and phenotypic screening, assay design, and advanced applications in toxicology and drug repurposing. It addresses critical challenges in data quality control, hit selection, and systematic error correction. Finally, it outlines streamlined validation processes, comparative analysis of public HTS data, and the integration of FAIR data principles. This resource is designed to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop reliable, high-quality HTS assays that accelerate discovery in biomedicine.

Building Blocks of HTS: Core Principles, Components, and Strategic Planning

Defining High-Throughput and Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (HTS/uHTS)

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated, experimental method used primarily in drug discovery to rapidly test thousands to millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological compounds for biological activity against a specific target [1] [2]. The core principle involves the parallel processing of vast compound libraries using automated equipment, robotic-assisted sample handling, and sophisticated data processing software to identify initial "hit" compounds with desired activity [1]. HTS typically enables the screening of 10,000 to 100,000 compounds per day [3].

Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) represents an advanced evolution of HTS, pushing throughput capabilities even further. uHTS systems can conduct over 100,000, and in some configurations, millions of assays per day [2] [3]. This is achieved through extreme miniaturization, advanced microfluidics, and highly integrated automation, allowing for unprecedented speeds in lead compound identification.

Key Characteristics and Quantitative Comparison

The distinction between HTS and uHTS is defined by several operational and technological parameters. The following table summarizes the core characteristics that differentiate these two screening paradigms.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of HTS and uHTS

| Attribute | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 10,000 - 100,000 compounds per day [3] | >100,000, potentially millions of compounds per day [2] [3] |

| Typical Assay Formats | 96-, 384-, and 1536-well microtiter plates [1] [2] | 1536-well plates and higher (3456, 6144); microfluidic droplets [2] [3] |

| Assay Volume | Microliter (μL) range [4] | Nanoliter (nL) to low microliter range; some systems use 1-2 μL [2] [3] |

| Primary Goal | Rapid identification of active compounds ("hits") from large libraries [1] | Maximum screening capacity for the largest libraries; extreme miniaturization and cost reduction [3] |

| Technology Enablers | Robotics, automated liquid handlers, sensitive detectors [2] | Advanced microfluidics, high-density microplates, multiplexed sensor systems [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Cell Viability Screening using a Homogeneous Assay

This protocol is designed for a 384-well format to identify compounds that affect cell viability, a common application in oncology and toxicology research [4].

A. Primary Screening Workflow

- Assay Plate Preparation: Using an automated liquid handler, prepare assay plates by transferring 10 nL - 50 nL of compound from a DMSO stock library into the wells of a 384-well microtiter plate. Include control wells: positive control (e.g., 1 μM staurosporine for cell death) and negative control (DMSO only) [2] [3].

- Cell Seeding: Harvest and resuspend adherent cells (e.g., HeLa or HEK293) in appropriate growth medium to a density of 50,000 - 100,000 cells/mL. Using a dispensing unit, add 40 μL of cell suspension to each well of the assay plate, resulting in 2,000 - 5,000 cells per well [4].

- Incubation: Place the assay plates in a humidified CO₂ incubator at 37°C for 48-72 hours to allow cell growth and compound exposure.

- Viability Reagent Addition: Following incubation, add 10 μL of a homogeneous, luminescent cell viability assay reagent (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) to each well using a reagent dispenser. The assay reagent lyses the cells and produces a luminescent signal proportional to the amount of present ATP, which correlates with the number of viable cells.

- Signal Detection: Protect the plate from light and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to stabilize the luminescent signal. Read the plate using a microplate reader equipped with a luminescence detector.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cell viability for each test compound using the formula:

- % Viability = (Luminescence of Test Compound - Luminescence of Positive Control) / (Luminescence of Negative Control - Luminescence of Positive Control) x 100

- Compounds exhibiting viability below a pre-set threshold (e.g., <50% viability) are identified as "hits" for confirmation [3].

B. Secondary Screening: IC₅₀ Determination

- Hit Confirmation: "Hit" compounds from the primary screen are re-tested in a dose-response manner. Prepare a 3-fold serial dilution of each hit compound across 8-10 concentrations.

- Dose-Response Assay: Repeat steps 1-5 of the primary screening protocol for these dilution series.

- Curve Fitting: Plot the log of compound concentration against the % viability response. Fit the data to a four-parameter logistic model (4PL) to calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) for each confirmed hit [3].

Protocol: Biochemical Enzyme Inhibition Assay

This protocol outlines a uHTS-compatible, miniaturized fluorescence-based assay to identify enzyme inhibitors in a 1536-well format [3].

- Compound and Reagent Dispensing: Using a non-contact acoustic dispenser, transfer 20 nL of each test compound from the library into the wells of a 1536-well plate. Subsequently, dispense 2 μL of the enzyme (e.g., 1 nM Protein Phosphatase 1C (PP1C)) in assay buffer into all wells [3].

- Pre-Incubation: Centrifuge the plate briefly and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes to allow compounds to interact with the enzyme.

- Reaction Initiation: Add 2 μL of a fluorescently labeled substrate (e.g., 100 μM 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate) to all wells to initiate the enzymatic reaction. The final assay volume is 4 μL.

- Reaction and Detection: Incubate the plate for 60 minutes at room temperature. Stop the reaction by adding 1 μL of a stop solution. Measure the fluorescence intensity (excitation ~360 nm, emission ~450 nm) using a high-speed plate reader.

- uHTS Data Processing: The raw fluorescence data is automatically processed. The % inhibition for each compound is calculated relative to enzyme-only (positive inhibition) and substrate-only (basal signal) controls. Advanced data analysis software employing machine learning algorithms can be used for hit identification and triage to minimize false positives [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful HTS/uHTS campaigns rely on a standardized set of high-quality reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HTS/uHTS

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Disposable plastic plates with 96, 384, 1536, or more wells; the foundational labware for HTS [2]. | All HTS/uHTS formats; 1536-well plates are standard for uHTS. |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of structurally diverse small molecules, natural product extracts, or biologics stored in DMSO [1] [3]. | Source of chemical matter for screening against biological targets. |

| Cell Lines | Engineered or primary cells used in cell-based assays to provide a physiological context [4] [5]. | Phenotypic screening, toxicity assessment, and target validation. |

| Fluorescent Probes / Antibodies | Molecules that bind to specific cellular targets (e.g., proteins, DNA) and emit detectable light [6] [5]. | Detection of binding events, cell surface markers, and intracellular targets in flow cytometry. |

| Homogeneous Assay Kits | "Mix-and-read" reagent kits (e.g., luminescent viability, fluorescence polarization) that require no washing steps [3] [6]. | Simplified, automation-friendly assays for high-throughput applications. |

| High-Throughput Flow Cytometry Systems | Instruments like the iQue platform that combine rapid sampling with multiparameter flow cytometry [6] [5]. | Multiplexed analysis of cell phenotype and function directly from 384-well plates. |

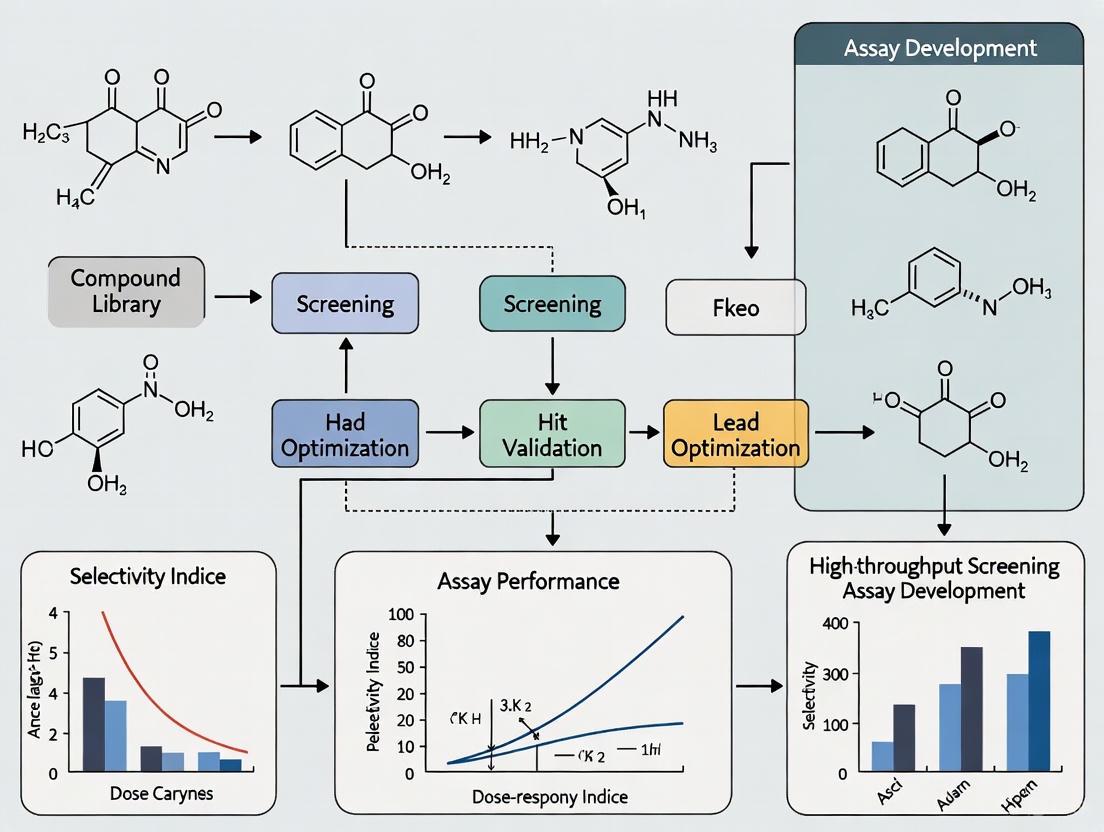

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the core HTS/uHTS screening cascade and a multiplexed high-throughput flow cytometry process.

HTS Screening Cascade

HT Flow Cytometry Process

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a method for scientific discovery that uses automated equipment to rapidly test thousands to millions of samples for biological activity at the model organism, cellular, pathway, or molecular level [1]. In its most common form, HTS is an experimental process in which 103–106 small molecule compounds of known structure are screened in parallel [1]. The effectiveness of HTS relies on a triad of core automated systems: robotic liquid handlers for precise sample and reagent manipulation, microplate readers for detecting biological or chemical reactions, and sophisticated detection systems that translate these events into quantifiable data. This integrated hardware foundation enables researchers in pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and academic settings to identify "hit" compounds with pharmacological or biological activity, providing starting points for drug discovery and development [1]. The relentless drive for efficiency has pushed assay volumes down, making reliable manual handling impossible and necessitating the implementation of automation to manage the immense scale of screening [1].

Core Hardware Components of an HTS Platform

Robotic Liquid Handling Systems

Robotic liquid handlers are the workhorses of any HTS platform, automating the precise transfer of liquids that is fundamental to screening millions of compounds. These systems minimize human error, enhance reproducibility, and enable the processing of thousands of microplates without manual intervention. The integration of these systems with other laboratory instruments creates a seamless, walk-away automated workflow essential for modern HTS operations [7].

Table 1: Types of Automated Liquid Handling Systems and Their Applications

| System Type | Primary Function | Common Applications | Approximate Price Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pipetting Robots [8] | Automated liquid transfer using pipette tips. | PCR setup, serial dilutions, plate reformatting. [8] | $10,000 - $50,000 [8] |

| Workstations [8] | Versatile systems for simple to complex tasks; often include integrated modules. | High-throughput screening, ELISA, complex assay assembly. [8] | $30,000 - $150,000 [8] |

| Microplate Dispensers [8] | High-speed dispensing of reagents, samples, or cells into microplates. | Drug screening, biochemical assays, genomic assays. [8] | $5,000 - $30,000 [8] |

| Liquid Handling Platforms [8] | Fully automated, scalable systems that integrate with other lab instruments. | Large-scale operations, complex workflows in pharma and biotech. [8] | $100,000 - $500,000 [8] |

Advanced HTS systems, like the one implemented at the NIH Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), feature random-access on-line compound library storage carousels with a capacity for over 2.2 million samples, multifunctional reagent dispensers, and 1,536-pin arrays for rapid compound transfer [7]. This level of integration and miniaturization is crucial for paradigms like quantitative HTS (qHTS), which tests each compound at multiple concentrations and can require screening between 700,000 and 2,000,000 sample wells for a single library [7].

Microplate Readers and Detection Technologies

The microplate reader is the optical engine of the HTS system, tasked with measuring chemical, biological, or physical reactions within the wells of a microplate [9]. These instruments detect signals produced by assay reactions and convert them into numerical data for analysis. The choice of detection mode is dictated by the assay chemistry and the biological question being asked.

Table 2: Key Detection Modes in Microplate Readers

| Detection Mode | Working Principle | Typical HTS Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Absorbance [9] | Measures the amount of light absorbed by a sample at a specific wavelength. | Microbial growth (OD600), ELISA, cell viability (MTT, WST). [9] |

| Fluorescence Intensity (FI) [9] | Measures light emitted by a sample after excitation at a specific wavelength. | Cell viability (Resazurin), enzyme activity (NADH-based), nucleic acid quantification. [9] |

| Luminescence [9] | Measures light emitted from a chemical or enzymatic reaction without excitation. | Cell viability (CellTiter-Glo), reporter gene assays (Dual-Luciferase). [9] |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [9] | Measures the change in polarization of emitted light from a fluorescent molecule, indicating molecular binding or size. | Competitive binding assays, nucleotide detection. [9] |

| Time-Resolved Fluorescence (TRF) & TR-FRET [9] | Uses long-lived fluorescent lanthanides to delay measurement, eliminating short-lived background fluorescence. TR-FRET combines TRF with energy transfer between molecules in close proximity. | Biomolecule quantification, kinase assays, protein-protein interaction studies. [9] |

| AlphaScreen [9] | A bead-based proximity assay that produces a luminescent signal when donor and acceptor beads are brought close together. | Protein-protein interactions, protein phosphorylation, cytokine quantification (AlphaLISA). [9] |

Modern HTS facilities utilize multi-mode microplate readers that combine several of these detection technologies on a single platform, providing great flexibility for a diverse portfolio of assays [10]. For instance, a multi-mode reader might be configured for absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, fluorescence polarization, and TR-FRET, allowing it to support everything from ELISAs and nucleic acid quantitation to complex cell-based reporter assays and binding studies [10].

Application Note: Implementing a Quantitative HTS (qHTS) Campaign

Objective

To implement a full qHTS campaign for a biochemical enzyme inhibition assay, identifying active compounds and generating concentration-response curves (CRCs) for a library of 100,000 compounds. qHTS involves testing each compound at multiple concentrations (typically seven or more) and is used to generate a rich data set that more fully characterizes biological effects and decreases false positive/negative rates compared to traditional single-concentration HTS [1] [7].

Experimental Workflow and Hardware Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated hardware workflow for a qHTS campaign, from compound storage to data output.

Protocol: qHTS for Enzyme Inhibition

Pre-Screening Hardware and Reagent Setup

- Compound Library Management: Ensure the robotic system's on-line storage carousels contain the compound library formatted in a 7-point concentration series, diluted in DMSO, in 1536-well compound plates [7]. The final concentration of DMSO in the assay must be validated (typically kept under 1% for cell-based assays) to ensure compatibility [11].

- Assay Plate Selection: Use 1536-well, low-volume, white assay plates for optimal signal detection in luminescence-based assays.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare enzyme, substrate, and appropriate controls (Max, Min, and Mid signals) in assay buffer. The stability of these reagents under storage and assay conditions must be predetermined [11].

- Liquid Handler Programming: Program the robotic liquid handler to transfer a defined nanoliter volume of the compound series from the source plates to the assay plates using a high-precision pin tool [7].

Automated Screening Protocol

- Compound Transfer: The robotic system transfers 20 nL of each compound concentration from the source plate to the corresponding well of the assay plate [7].

- Enzyme Addition: Using a bulk reagent dispenser (e.g., a solenoid-valve-based dispenser), add 2 µL of the enzyme solution in assay buffer to all wells of the assay plate. The system's anthropomorphic robotic arm moves the plate to the dispenser station [7].

- Incubation and Mixing: The plate is transferred to one of the system's incubators and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes with gentle shaking to facilitate mixing and compound-enzyme interaction.

- Substrate Addition: Add 2 µL of substrate solution to initiate the enzymatic reaction. The final reaction volume is 4 µL.

- Reaction Incubation: Incubate the plate for a predetermined time (e.g., 60 minutes) at room temperature, ensuring the reaction stability over this period has been validated [11].

- Signal Detection: Transfer the plate to a luminescence-compatible microplate reader (e.g., a ViewLux or similar). Read the plate according to the luminescence protocol optimized for the specific substrate (e.g., integration time of 1 second per well) [7].

Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Data Collection: The microplate reader's software (e.g., SoftMax Pro) collects raw luminescence counts for every well [10].

- Curve Fitting: Data processing software automatically normalizes the raw data using the controls (Max and Min signals) and fits a CRC for each compound using a four-parameter logistic model [7] [10].

- Hit Selection: Compounds are classified based on the quality and potency of their CRCs. A hit is typically defined by a curve class and a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) or inhibitory concentration (IC50) value below a predefined threshold (e.g., 10 µM) [2] [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The success of an HTS assay depends on the seamless interaction between hardware, reagents, and biological components.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for HTS Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTS Assay | Example Kits/Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Kits [9] | Measure ATP content or metabolic activity as a proxy for the number of viable cells. | CellTiter-Glo (Luminescence), Resazurin (Fluorescence), MTT (Absorbance). [9] |

| Reporter Gene Assay Kits [9] | Quantify gene expression or pathway modulation by measuring the activity of a reporter enzyme (e.g., luciferase). | Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay. [9] |

| Protein Quantification Kits [9] [10] | Quantify the amount of protein in a sample, often used in ELISAs or general protein analysis. | Bradford, BCA, Qubit assays. [9] [10] |

| TR-FRET/HTRF Kits [9] [10] | Homogeneous assays used to study binding events, protein-protein interactions, and post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation). | HTRF, Lanthascreen kits for kinase targets. [9] [10] |

| Enzyme Substrates | Converted by the target enzyme to a detectable product (fluorescent, luminescent, or chromogenic). | 4-Methylumbelliferone (4-MU), 7-Amino-4-Methylcoumarin (AMC). [9] |

| Controls (Agonists/Antagonists) [11] | Used for assay validation and data normalization. Define the Max, Min, and Mid signals for curve fitting and quality control. | A known potent inhibitor for an enzyme assay; a full agonist for a receptor assay. [11] |

Assay Validation and Quality Control Protocols

Rigorous validation is essential before initiating any large-scale HTS campaign to ensure the assay is robust, reproducible, and pharmacologically relevant [11]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for HTS assay validation.

Objective

To statistically validate the performance of an HTS assay in a 384-well format, establishing its robustness and readiness for automated screening.

Protocol: Plate Uniformity and Variability Assessment

This validation assesses the signal uniformity and the ability to distinguish between positive and negative controls across the entire microplate [11].

Reagent and Plate Preparation

- Define Assay Signals: Prepare solutions for three critical signals:

- Max Signal: The maximum possible signal (e.g., enzyme reaction with no inhibitor).

- Min Signal: The background or minimum signal (e.g., enzyme reaction with a potent inhibitor or no substrate).

- Mid Signal: A mid-point signal (e.g., enzyme reaction with an IC50 concentration of a control inhibitor) [11].

- Plate Layout: For a 3-day validation, use an interleaved-signal format. On each 384-well plate, designate wells for Max (H), Min (L), and Mid (M) signals in a statistically designed pattern that controls for positional effects [11]. A simplified layout is shown below.

Execution and Data Analysis

- Assay Execution: Run the assay on three separate days using independently prepared reagents. Use the same robotic liquid handlers and microplate readers planned for the production screen.

- Quality Control (QC) Metric Calculation: For each day, calculate the Z'-factor, a standard QC metric that assesses the assay's quality by evaluating the separation between the Max and Min signal bands [2] [11].

- Formula: Z' = 1 - [ (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| ]

- Where σ is the standard deviation and μ is the mean of the Max and Min controls.

- Interpretation: An assay is generally considered excellent if the Z'-factor is >0.5, indicating a large separation band and low variability, and therefore suitable for HTS [2].

Microtiter plates, also known as microplates or multiwell plates, are foundational tools in modern high-throughput screening (HTS) and drug discovery research. These platforms, characterized by their standardized footprint and multiple sample wells, have revolutionized how scientists prepare, handle, and analyze thousands of biological or chemical samples simultaneously [12] [13]. The evolution from manual testing methods to automated, miniaturized assays has positioned microtiter plates as indispensable in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and basic life science research.

The transition toward higher-density formats represents a critical innovation pathway in HTS assay development. Beginning with 96-well plates as the historical workhorse, technology has advanced to 384-well, 1536-well, and even 3456-well formats, enabling unprecedented miniaturization and throughput [12] [13]. This progression allows researchers to dramatically reduce reagent volumes and costs while expanding screening capabilities, though it introduces new challenges in liquid handling, assay optimization, and data management that must be addressed through careful experimental design.

Technical Specifications and Selection Criteria

Microplate Formats and Geometries

Microtiter plates are available in standardized formats with wells arranged in a rectangular matrix. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening (SLAS) have established critical dimensional standards (ANSI/SLAS) to ensure compatibility with automated instrumentation across manufacturers [12] [13]. These standards define the footprint (127.76 mm × 85.48 mm), well positions, and flange geometry, while well shape and bottom elevation remain more variable proprietary implementations.

Table 1: Standard Microtiter Plate Formats and Volume Capacities [12]

| Well Number | Well Arrangement | Typical Well Volume | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 2×3 | 2-5 mL | Small-scale cell culture |

| 12 | 3×4 | 2-4 mL | Small-scale cell culture |

| 24 | 4×6 | 0.5-3 mL | Cell culture, ELISA |

| 48 | 6×8 | 0.5-1.5 mL | Cell culture, ELISA |

| 96 | 8×12 | 100-300 µL | ELISA, biochemical assays, primary screening |

| 384 | 16×24 | 30-100 µL | HTS, compound screening |

| 1536 | 32×48 | 5-25 µL | UHTS, miniaturized screening |

| 3456 | 48×72 | 1-5 µL | Specialized UHTS applications |

Higher density formats (384-well and above) enable significant reagent savings and throughput enhancement but require specialized equipment for liquid handling and detection [12]. For instance, transitioning from 96-well to 384-well format reduces reagent consumption approximately 4-fold, while 1536-well plates can reduce volumes by 8-10 times compared to 96-well plates. Miniaturized variants such as half-area 96-well plates and low-volume 384-well plates provide intermediate solutions that offer volume reduction while maintaining compatibility with standard 96-well plate instrumentation [12] [14].

Material Composition and Optical Properties

The choice of microplate material significantly impacts assay performance through effects on light transmission, autofluorescence, binding characteristics, and chemical resistance. Manufacturers utilize different polymer formulations optimized for specific applications:

- Polystyrene (PS): The most common material, offering excellent clarity for optical detection; suitable for absorbance assays and microscopy with moderate modification. Standard polystyrene does not transmit UV light below 320 nm, making it unsuitable for nucleic acid quantification [12] [13].

- Cyclo-olefins (COP/COC): Provide superior ultraviolet light transmission (200-400 nm) with low autofluorescence, ideal for DNA/RNA quantification and UV spectroscopy [12] [13].

- Polypropylene (PP): Exhibits excellent temperature stability and chemical resistance, suitable for storage at -80°C, thermal cycling, and applications involving organic solvents [13].

- Polycarbonate (PC): Used for disposable PCR plates due to ease of molding and moderate temperature tolerance [13].

- Glass/Quartz: Provide the best optical properties for transparency and UV transmission but are expensive, fragile, and typically reserved for specialized applications [12].

Table 2: Microplate Material Properties and Applications [12] [13] [14]

| Material | UV Transparency | Auto-fluorescence | Temperature Resistance | Chemical Resistance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene | Poor (<320 nm) | Moderate | Low (melts at ~80°C) | Poor to organic solvents | ELISA, absorbance assays, cell culture (treated) |

| Cyclo-olefin | Excellent | Low | Moderate | Moderate | UV spectroscopy, DNA/RNA quantification |

| Polypropylene | Moderate | Moderate | Excellent (-80°C to 121°C) | Excellent | Compound storage, PCR, solvent handling |

| Polycarbonate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Disposable PCR plates |

| Glass/Quartz | Excellent | Very Low | Excellent | Excellent | Specialized optics, UV applications |

Plate Color and Well Geometry

Microplate color significantly influences detection sensitivity in various assay formats by controlling background signal, autofluorescence, and cross-talk between adjacent wells [12]:

- Clear plates are essential for absorbance-based assays where light must pass through the sample, such as ELISA and colorimetric enzymatic assays [12].

- Black plates absorb excitation and emission light, reducing background fluorescence and cross-talk, making them ideal for fluorescence intensity, FRET, and fluorescence polarization assays [12].

- White plates reflect light, maximizing signal capture for luminescence, time-resolved fluorescence (TRF), and TR-FRET applications where signal intensity is typically low [12].

- Grey plates serve as a compromise between black and white, recommended for AlphaScreen and AlphaLISA technologies to balance signal detection with cross-talk reduction [12].

Well geometry also impacts assay performance. Round wells facilitate mixing and are less prone to cross-talk, while square wells provide greater surface area for light transmission and cell attachment. Well bottom shape varies including flat (optimal for optical reading and adherent cells), conical (for maximum volume retrieval), and rounded (facilitating mixing and solution removal) [12] [14].

Application Note 1: Determination of Optimal Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) for Bacteriophage Therapy

Background and Principle

Bacteriophage therapy represents a promising approach for addressing antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) infections. The multiplicity of infection (MOI), defined as the ratio of bacteriophages to target bacteria, is a critical parameter determining therapeutic efficacy. This application note details a revisited two-step microtiter plate assay for optimizing MOI values for coliphage and vibriophage, enabling rapid screening across a wide MOI range (0.0001 to 10,000) followed by precise determination of optimal concentrations [15].

The assay principle involves co-cultivating bacteriophages with their bacterial hosts in microtiter plates and monitoring bacterial growth inhibition through optical density measurements. The two-step approach first identifies effective MOI ranges, then refines the optimum MOI that achieves complete bacterial growth inhibition with minimal phage input [15].

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial strains: Antimicrobial-resistant E. coli strains (EC-3, EC-7, EC-11) and luminescent Vibrio harveyi [15]

- Bacteriophages: Coliphage-ɸ5 and Vibriophage-ɸLV6 [15]

- Growth media: Appropriate sterile broth for each bacterial strain

- Microtiter plates: 96-well plates with clear, flat bottoms for absorbance reading [15]

- Plate reader: Capable of measuring OD at 550 nm or 600 nm

Procedure Step 1: Broad-Range MOI Screening

- Prepare bacterial suspensions in log-phase growth (OD ~0.3-0.4) in fresh broth.

- Serially dilute bacteriophage stocks to create concentrations spanning the target MOI range (0.0001 to 10,000).

- In a 96-well microtiter plate, add 100 µL of bacterial suspension to each well.

- Add 100 µL of appropriate phage dilution to respective wells, creating the desired MOI values. Include phage-free controls for normal growth comparison.

- Seal plates with breathable membranes or lid and incubate at optimal growth temperature with shaking if available.

- Monitor OD at 550 nm or 600 nm at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) until control wells reach stationary phase.

- Identify MOI ranges that show significant bacterial growth inhibition compared to controls.

Step 2: Optimal MOI Determination

- Based on Step 1 results, prepare a narrower range of phage dilutions centered on the effective MOI values.

- Repeat the co-culture procedure as in Step 1 with more replicate wells (minimum n=3) per MOI value.

- Measure OD values throughout growth周期.

- Calculate specific growth parameters and determine the optimal MOI as the lowest phage concentration that achieves complete bacterial growth inhibition.

Data Analysis

- Plot growth curves for each MOI condition and control.

- Calculate area under the curve (AUC) for each growth profile.

- Determine percentage growth inhibition relative to phage-free controls.

- The optimal MOI is identified as the point where further increases in phage concentration do not significantly improve inhibition efficiency.

Validation For coliphage-ɸ5, this method identified optimal MOI values of 17.44, 191, and 326 for controlling growth of E. coli strains EC-3, EC-7, and EC-11, respectively. For vibriophage-ɸLV6, the optimum MOI was determined to be 79 for controlling luminescent Vibrio harveyi [15]. The microtiter plate method yielded faster optimization with reduced reagent consumption compared to conventional flask methods, with comparable results obtained using either 3 or 5 replicate wells and OD measurements at either 550 nm or 600 nm [15].

Application Note 2: Multiplex Microarray for β-Lactamase Gene Detection

Background and Principle

The rapid spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly those producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases, necessitates efficient multiplex detection methods. This application note describes a novel microarray system fabricated in 96-well microtiter plates for simultaneous identification of multiple β-lactamase genes and their single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [16].

The technology utilizes photoactivation with 4-azidotetrafluorobenzaldehyde (ATFB) to covalently attach oligonucleotide probes to polystyrene plate wells. Following surface modification, the microarray detects target genes through hybridization with biotinylated DNA, followed by colorimetric development using streptavidin-peroxidase conjugates with TMB substrate [16]. This approach combines the multiplexing capability of microarrays with the throughput and convenience of standard microtiter plate formats.

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

- Microplates: 96-well polystyrene plates [16]

- Photoactivation reagent: 4-azidotetrafluorobenzaldehyde (ATFB) [16]

- Oligonucleotide probes: 5'-aminated with 13-mer thymidine spacers [16]

- Target DNA: Biotinylated PCR products or biotin-labeled RNA transcripts

- Detection reagents: Streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate, TMB substrate [16]

- Hybridization buffer: Containing dextran sulfate, casein, and Triton X-100 [16]

Procedure Step 1: Plate Surface Functionalization

- Prepare ATFB solution in organic solvent (e.g., ethanol or acetone).

- Add ATFB solution to polystyrene plate wells and incubate briefly.

- Remove excess solution and dry plates under gentle stream of nitrogen.

- Expose plates to UV light (254 nm) for photoactivation and covalent attachment.

- Wash plates extensively to remove unbound reagent.

Step 2: Oligonucleotide Probe Immobilization

- Prepare amine-modified oligonucleotide probes in appropriate spotting buffer.

- Array probes onto functionalized plate wells using manual or robotic spotting.

- Incubate plates overnight under humid conditions to complete covalent linkage.

- Block remaining reactive groups with blocking solution (e.g., BSA or casein).

- Wash plates with buffer containing detergent to remove unbound probes.

Step 3: Sample Hybridization

- Prepare biotin-labeled target DNA through PCR with biotinylated primers or in vitro transcription with biotin-UTP for RNA targets.

- Denature DNA samples by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes then immediately chill on ice.

- Add denatured samples to microarray wells in hybridization buffer.

- Incubate at optimal hybridization temperature (determined by probe Tm) for 2-4 hours.

- Wash stringently with buffers of decreasing ionic strength to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

Step 4: Colorimetric Detection

- Add streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate in appropriate buffer.

- Incubate 30-60 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Wash thoroughly to remove unbound conjugate.

- Add TMB substrate solution and incubate for color development.

- Stop reaction with acid solution when optimal signal develops.

- Measure absorbance at 450 nm using standard plate reader.

Microarray Design The platform was designed to detect:

- 8 carbapenemase gene types (classes A, B, D: blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaSPM, blaGIM, blaSIM, blaOXA)

- 3 ESBL gene types (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M)

- 16 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in class A bla genes [16]

A second microarray variant was developed for quantifying bla mRNAs (TEM, CTX-M-1, NDM, OXA-48) to study gene expression in resistant bacteria [16].

Validation The method demonstrated high sensitivity and reproducibility when testing 65 clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae, detecting bla genes with accuracy comparable to conventional methods while offering significantly higher multiplexing capability [16]. The combination of reliable performance in standard 96-well plates with inexpensive colorimetric detection makes this platform suitable for routine clinical application and studies of multi-drug resistant bacteria.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of microtiter plate-based assays requires careful selection of specialized reagents and materials. The following table outlines key solutions for the protocols described in this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microtiter Plate Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Azidotetrafluorobenzaldehyde (ATFB) | Photoactivatable crosslinker for surface functionalization | Forms covalent bonds with polystyrene upon UV exposure; creates reactive aldehyde groups | Microarray probe immobilization in polystyrene plates [16] |

| Biotin-UTP/dUTP | Labeling nucleotide for target detection | Incorporated into DNA/RNA during amplification; binds streptavidin conjugates | Preparation of labeled targets for microarray detection [16] |

| Streptavidin-Peroxidase Conjugate | Signal generation enzyme complex | Binds biotin with high affinity; catalyzes colorimetric reactions | Colorimetric detection in microarray and ELISA applications [16] |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic peroxidase substrate | Colorless solution turns blue upon oxidation; reaction stoppable with acid | Color development in enzymatic detection systems [16] |

| Amine-Modified Oligonucleotides | Capture probes for microarray | 5'-amino modification with spacer arm for surface attachment | Specific gene detection in multiplex arrays [16] |

| Dextran Sulfate | Hybridization accelerator | Anionic polymer that increases effective probe concentration | Enhancement of hybridization efficiency in microarrays [16] |

| Casein/Tween-20 | Blocking agents | Reduce non-specific binding in biomolecular assays | Blocking steps in microarray and ELISA protocols [16] |

The evolution of microtiter plate technology continues to drive advances in high-throughput screening and diagnostic applications. Several emerging trends are shaping the future landscape of microplate-based research:

Market Growth and Technological Convergence The high-throughput screening market is projected to grow from USD 32.0 billion in 2025 to USD 82.9 billion by 2035, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.0% [17]. This expansion is fueled by increasing R&D investments in pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, alongside continuous innovation in automation, miniaturization, and data analytics [17] [18]. The convergence of artificial intelligence with experimental HTS, along with developments in 3D cell cultures, organoids, and microfluidic systems, promises to further enhance the predictive power and efficiency of microplate-based screening platforms [19].

Ultra-High-Throughput Screening Advancements The ultra-high-throughput screening segment is anticipated to expand at a CAGR of 12% through 2035, reflecting the growing demand for technologies capable of screening millions of compounds rapidly and efficiently [17]. Improvements in automation, microfluidics, and detection sensitivity are making 1536-well and 3456-well formats increasingly accessible, though these platforms require substantial infrastructure investment and specialized expertise [12] [17].

Integration with Personalized Medicine The shift toward precision medicine is creating new applications for microtiter plate technologies in genomics, proteomics, and chemical biology [20]. Microplate-based systems are adapting to support the development of targeted therapies through improved assay relevance, including the use of primary cells, 3D culture models, and patient-derived samples [19] [14].

In conclusion, microtiter plates maintain a central role in high-throughput screening and diagnostic applications, with their utility extending from basic 96-well formats to sophisticated ultra-high-density systems. The continued innovation in plate design, surface chemistry, and detection methodologies ensures that these platforms will remain indispensable tools for drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and life science research. As assay requirements evolve toward greater physiological relevance and higher information content, microplate technology will similarly advance to meet these challenges, supporting the next generation of scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

High-throughput screening (HTS) generates vast biological data from testing millions of compounds, making robust software and data management systems critical for controlling automated hardware and transforming raw data into actionable scientific insights [21]. This article details the protocols and application notes for managing these complex workflows, framed within the context of HTS assay development.

The HTS Data Landscape and Management Architecture

The core challenge in modern HTS is no longer simply generating data, but effectively managing, processing, and analyzing the massive datasets produced. Public data repositories like PubChem, hosted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), exemplify this data scale, containing over 60 million unique chemical structures and data from over 1 million biological assays [21]. A typical HTS data management architecture must integrate multiple components to handle this flow.

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of data from automated hardware control to final analysis and storage.

Quantitative HTS Data Profile

The table below summarizes the scale and characteristics of a typical HTS data landscape.

Table 1: Profile of HTS Data from a Single Screening Campaign

| Data Characteristic | Typical Scale or Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Compounds Screened | 100,000 - 1,000,000+ | Number of unique compounds tested in a single primary screen [22]. |

| Assay Plate Format | 384, 1536, or 3456 wells | Miniaturized formats enabling high-throughput testing [22]. |

| Data Points Generated | Millions per campaign | A single 384-well plate generates 384 data points; a 100,000-compound screen in 1536-well format generates over 100,000 data points. |

| Primary Readout Types | Fluorescence, Luminescence, Absorbance | Common detection methods (e.g., FP, TR-FRET, FI) [22]. |

| Key Performance Metric | Z'-factor > 0.5 | Indicates an excellent and robust assay; values of 0.5-1.0 are acceptable [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation and Management

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments and data handling procedures in HTS.

Protocol: Biochemical HTS Assay for Kinase Inhibition

This protocol uses a universal ADP detection method (e.g., Transcreener platform) to identify kinase inhibitors [22].

Assay Setup and Automation

- Plate Format: Use 384-well or 1536-well microplates.

- Liquid Handling: Employ an automated liquid handling system to dispense 5-20 µL of kinase reaction buffer into each well.

- Compound Addition: Using a pintool or nanoliter dispenser, transfer compounds from the library to assay plates. Include controls: positive controls (no compound, maximum enzyme activity), negative controls (no enzyme, background signal), and a reference inhibitor control.

- Enzyme Addition: Add kinase enzyme to all wells except negative controls.

Reaction Initiation and Incubation

- Initiate the reaction by dispensing ATP/substrate mix into all wells using the liquid handler.

- Seal the plate to prevent evaporation and incubate at room temperature for the predetermined time (e.g., 60 minutes).

Detection and Signal Capture

- Stop the reaction by adding the detection mix containing ADP-specific antibody and fluorescent tracer.

- Incubate the plate for 30-60 minutes in the dark for signal development.

- Read the plate using a compatible microplate reader (e.g., for Fluorescence Polarization (FP) or TR-FRET).

Primary Data Acquisition and File Management

- The plate reader software outputs raw data files (e.g., CSV, XML).

- Automatically transfer files to a designated network location with a standardized naming convention (e.g.,

AssayID_PlateID_Date_ReaderID). - Use a script to parse files and load raw values into a database for analysis.

Protocol: Programmatic Retrieval of HTS Data from PubChem

For computational modelers needing bioactivity data for large compound sets, manual download is impractical. This protocol uses PubChem Power User Gateway (PUG)-REST for automated data retrieval [21].

Input List Preparation

- Prepare a list of target compound identifiers (e.g., PubChem CIDs, SMILES) in a text file.

URL Construction for PUG-REST

- Construct a URL string with four parts: base, input, operation, and output.

- Base:

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/rest/pug - Input:

compound/cid/[CID_LIST]/(e.g.,compound/cid/2244,7330/) - Operation:

property/followed by the desired properties (e.g.,BioAssayResults). - Output:

JSON,XML, orCSV.

Automated Data Retrieval Script

- Write a script in a language like Python or Perl to iterate through the input list.

- For each compound, the script constructs the appropriate PUG-REST URL and submits the HTTP request.

- The script parses the returned data (e.g., JSON) and compiles it into a structured table.

Data Compilation and Storage

- The final output is a file (e.g., CSV) containing the bioassay results for all target compounds, ready for local analysis.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biochemical HTS

| Tool or Reagent | Function in HTS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Universal Detection Assays (e.g., Transcreener) | Measures a universal output (e.g., ADP) for multiple enzyme classes (kinases, GTPases, etc.), simplifying assay development and increasing workflow flexibility [22]. |

| Chemical Compound Libraries | Collections of thousands to millions of small molecules used to probe biological targets and identify potential drug candidates ("hits") [22]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Kits (e.g., Reporter Assays) | Enable phenotypic screening in a physiologically relevant environment to study cellular processes like receptor signaling or gene expression [22] [23]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Market | Valued at USD 28.8 billion in 2024, it is projected to grow, reflecting ongoing innovation and adoption in drug discovery [18]. |

| PubChem BioAssay Database | The largest public repository for HTS data, allowing researchers to query and download biological activity results for millions of compounds [21]. |

Data Analysis Workflow and Hit Identification

After data acquisition, a rigorous analytical workflow is employed to ensure quality and identify true "hits." The following diagram maps this multi-step process.

- Data Normalization: Raw signal values are normalized to plate-based controls (e.g., positive and negative controls) to calculate % activity or inhibition for each test compound.

- Quality Control (QC): Assay robustness is verified using the Z'-factor.

- Calculation: Z' = 1 - [ (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| ]

- Interpretation: A Z'-factor between 0.5 and 1.0 indicates an excellent assay suitable for HTS [22].

- Hit Identification: Active compounds ("hits") are identified by applying a threshold, commonly >50% inhibition or activation relative to controls.

- Secondary Analysis: Confirmed hits undergo further analysis to determine potency (IC50/EC50), efficacy, and structure-activity relationships (SAR) to prioritize the most promising leads [22].

The integration of sophisticated software for hardware control, data processing, and analysis with public data management infrastructures is fundamental to the success of modern HTS. These systems enable researchers to navigate the complex data landscape, accelerating the transformation of raw screening data into novel therapeutic discoveries.

Key Considerations in Assay Plate Design and Preparation

Microplate Selection and Miniaturization Strategy

The choice of microplate format is a foundational decision that dictates reagent consumption, throughput, and data quality in high-throughput screening (HTS). The standard plate formats and their characteristics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Standard Microplate Formats and Key Design Parameters for HTS

| Plate Format | Typical Assay Volume (μL) | Primary Application | Key Design Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96-Well | 50 - 200 | Assay development, low-throughput validation | High reagent consumption |

| 384-Well | 5 - 50 | Medium- to high-throughput screening | Increased risk of evaporation and edge effects |

| 1536-Well | 2 - 10 | Ultra-high throughput screening (uHTS) | Requires specialized, high-precision dispensing equipment |

Miniaturization from 96-well to 384- or 1536-well plates significantly reduces reagent costs but introduces physical challenges. The increased surface-to-volume ratio accelerates solvent evaporation. This is mitigated by using low-profile plates with fitted lids, humidified incubators, and specialized environmental control units [24].

Plate material selection—including polystyrene, polypropylene, or cyclic olefin copolymer—and surface chemistry—such as tissue culture treated or non-binding surfaces—must be rigorously tested for compatibility with assay components to mitigate non-specific binding [24].

Robust Assay Development and Validation

Before initiating a full HTS campaign, assay performance must be validated using quantitative statistical metrics to ensure robustness and reproducibility [24]. The Z'-factor is a key metric for assessing assay quality and is calculated from control data run in multiple wells across a plate [25] [24].

Table 2: Key Statistical Metrics for HTS Assay Validation

| Metric | Formula/Definition | Interpretation and Ideal Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | 1 - [3*(σp + σn) / | μp - μn | ] | Excellent assay: 0.5 to 1.0. |

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) | μp / μn | A higher ratio indicates a larger signal window. | ||

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | (μp - μn) / √(σp² + σn²) | A higher ratio indicates a more discernible signal. | ||

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (σ / μ) * 100% | Measures well-to-well variability; typically should be <10%. |

μ_p, σ_p: Mean and Standard Deviation of positive control; μ_n, σ_n: Mean and Standard Deviation of negative control.

Validation also encompasses several pre-screening tests [24]:

- Compound Tolerance: Determining if compounds or their solvents (e.g., DMSO) interfere with the assay signal.

- Plate Drift Analysis: Running control plates over a sustained period to confirm signal window stability, detecting issues like reagent degradation or instrument drift.

- Edge Effect Mitigation: Identifying and correcting for systematic signal gradients caused by uneven heating or evaporation, often via strategic control placement or specialized sealants.

Only after an assay demonstrates a consistent, acceptable Z'-factor (typically ≥0.5) should it be used for screening large compound libraries [25] [24].

Experimental Protocol: Vesicle Nucleating Peptide (VNp) Based Protein Expression and Assay

The following protocol describes a high-throughput method for expressing, exporting, and assaying recombinant proteins from Escherichia coli in the same microplate well using Vesicle Nucleating Peptide (VNp) technology [26].

Basic Protocol: Expression, Export, and Isolation of Vesicular-Packaged Recombinant Protein

Principle: A Vesicle Nucleating peptide (VNp) tag, fused to the protein of interest, induces the export of functional recombinant proteins from E. coli into extracellular membrane-bound vesicles. This allows for the production of protein of sufficient purity and yield for direct use in plate-based enzymatic assays without additional purification [26].

Materials:

- Recombinant E. coli strain: Expressing the VNp-tagged protein of interest.

- Growth Medium: LB or other suitable bacterial growth medium.

- Multi-well Plates: Sterile, deep-well plates (e.g., 96-well or 384-well format).

- Inducer: e.g., IPTG, for inducing protein expression.

- Plate Centrifuge: Capable of centrifuging multi-well plates.

- Lysis Buffer: Optional, containing anionic or zwitterionic detergents to lyse vesicles.

Procedure:

- Inoculation and Growth: In a sterile deep-well plate, inoculate growth medium with the recombinant E. coli strain. The typical working volume is 100-200 µL for a 96-well plate.

- Induction: Grow cells to mid-log phase and induce protein expression with an appropriate inducer (e.g., IPTG). Incubate overnight under optimal temperature and aeration conditions for protein expression and vesicular export.

- Vesicle Isolation: Centrifuge the culture plate (e.g., 3000-4000 x g for 10-30 minutes) to pellet the bacterial cells. The recombinant protein, packaged within vesicles, remains in the cleared culture supernatant.

- Transfer: Carefully transfer the supernatant containing the vesicles to a fresh microplate.

- Storage or Lysis: The vesicle-containing supernatant can be stored sterile-filtered at 4°C for over a year. For downstream assays, lyse the vesicles by adding a lysis buffer containing anionic or zwitterionic detergents to release the functional protein [26].

Support Protocol 2: In-Plate Affinity-Tag Protein Purification

If further purification is required, this protocol can be performed after the basic protocol.

- Equilibration: Transfer the vesicle-lysed supernatant to a plate pre-coated with affinity resin corresponding to the tag on the protein (e.g., Ni-NTA resin for His-tagged proteins).

- Binding: Incubate with gentle agitation to allow the tagged protein to bind to the resin.

- Washing: Wash the resin multiple times with a suitable buffer to remove non-specifically bound contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the purified protein using a buffer containing a competitive agent (e.g., imidazole for His-tagged proteins). The eluate can be used directly in assays [26].

Support Protocol 3: Example In-Plate Enzymatic Assay

This protocol measures the activity of an expressed and exported enzyme, such as VNp-uricase.

- Reaction Setup: In a fresh assay plate, combine the isolated vesicle fraction (containing the active enzyme) from the Basic Protocol with the appropriate enzyme substrate in the recommended reaction buffer.

- Kinetic Reading: Immediately place the plate in a microplate reader and initiate kinetic measurements. Monitor the change in absorbance or fluorescence over time, according to the assay's detection method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate enzymatic activity based on the rate of signal change. The reproducibility of protein yields with the VNp protocol allows for reliable comparison of activity across different conditions or mutant clones [26].

Workflow Automation and Integration

Effective HTS requires integrating microplate technology components into a continuous, optimized workflow [24]. Automation streamlines liquid handling, incubation, and detection, eliminating human variability.

A fully integrated HTS workflow typically includes:

- Liquid Handling Systems: High-precision automated dispensers (syringe-based or acoustic) for accurate, low-volume liquid transfer [27] [24].

- Robotic Plate Movers: Articulated arms or linear transports to move microplates between instruments (e.g., stackers, washers, readers, incubators) [24].

- Environmental Control: Temperature and CO₂-controlled incubators integrated within the system to maintain optimal assay conditions [24].

- Detection Systems: Microplate readers (e.g., spectrophotometers, fluorometers, luminometers, high-content imagers) linked directly to the system control software [25] [24].

Workflow optimization involves performing a time-motion study for every process step to maximize the utilization rate of the "bottleneck" instrument, typically the plate reader or a complex liquid handler [24].

Data Management and Quality Control

The volume and complexity of data generated by HTS necessitate a robust data management infrastructure. Millions of data points must be captured, processed, normalized, and stored in a searchable database [24].

Raw data from the microplate reader often requires normalization to account for systematic plate-to-plate variation. Common techniques include [24]:

- Z-Score Normalization: Expressing each well's signal in terms of standard deviations away from the plate's mean.

- Percent Inhibition/Activation: Calculating the signal relative to the positive (uninhibited) and negative (fully inhibited) controls.

Quality control (QC) metrics are critical for validating the entire screening run. Key metrics include [24]:

- Signal-to-Background Ratio (S/B)

- Control Coefficient of Variation (CV)

- Z'-factor

Plates that fail to meet pre-defined QC thresholds (e.g., Z'-factor < 0.5) should be flagged for potential re-screening [25] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HTS Assay Plate Preparation

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| VNp (Vesicle Nucleating peptide) Tag | Facilitates high-yield export of functional recombinant proteins from E. coli into extracellular vesicles [26]. | Fuse to the N-terminus of the protein of interest; optimal for monomeric proteins <85 kDa [26]. |

| Cell/Tissue Extraction Buffer | For preparing soluble protein extracts from cells or tissues for cell-based ELISAs or other assays [28]. | Typically contains Tris, NaCl, EDTA, EGTA, Triton X-100, and Sodium deoxycholate; must be supplemented with protease inhibitors [28]. |

| Transcreener HTS Assays | Universal biochemical assay platform for detecting enzyme activity (e.g., kinases, GTPases) [25]. | Uses fluorescence polarization (FP) or TR-FRET; flexible for multiple targets; suitable for potency and residence time measurements [25]. |

| HTS Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules screened against biological targets to identify active compounds ("hits") [25]. | Can be general or target-family focused; quality is critical to minimize false positives and PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) [25]. |

| Microplates (96-, 384-, 1536-well) | The physical platform for miniaturized, parallel assay execution [24]. | Choice of material (e.g., polystyrene) and surface treatment (e.g., TC-treated) is critical for assay compatibility and to prevent non-specific binding [24]. |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to lysis and extraction buffers to prevent protein degradation and preserve post-translational modifications during sample preparation [28]. | Should be added immediately before use [28]. |

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) serves as a foundational technology in modern drug discovery and biological research, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological compounds against biological targets [2]. This automated method leverages robotics, sophisticated data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to accelerate scientific discovery [2]. The fundamental workflow transforms stored compound libraries into actionable experimental data through a meticulously orchestrated process centered on microplate manipulation. At the core of this process lies the precise transition from stock plates—permanent libraries of carefully catalogued compounds—to assay plates, which are disposable testing vessels created specifically for each experiment [2]. This transformation enables researchers to efficiently identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways, providing crucial starting points for drug design and understanding biological interactions [2]. The evolution toward quantitative HTS (qHTS) has further enhanced this approach by generating full concentration-response relationships for each compound, providing richer pharmacological profiling of entire chemical libraries [2].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Fundamental HTS Components

- Stock Plates: Carefully catalogued libraries of compounds stored in microplate formats, typically maintained for long-term use. These plates serve as the master source of compounds and are not used directly in experiments to preserve their integrity [2].

- Assay Plates: Experimental plates created by transferring small liquid volumes from stock plates into empty plates. These plates contain the test compounds alongside biological entities and are the direct vessel for experimental measurements [2].

- Microtiter Plates: The essential labware for HTS, featuring grids of small wells in standardized formats. Common configurations include 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144 wells, all multiples of the original 96-well format with 9 mm spacing [2].

- Hit Compounds: Substances that demonstrate a desired effect size in screening experiments, identified through systematic hit selection processes [2].

- qHTS (Quantitative High-Throughput Screening): An advanced HTS paradigm that generates full concentration-response relationships for each compound, enabling more comprehensive pharmacological profiling [2].

HTS Assay Formats and Approaches

HTS assays generally fall into two primary categories, each with distinct advantages and applications:

- Biochemical Assays: Measure direct enzyme activity or receptor binding in a defined, cell-free system using purified components. These include enzyme activity assays (kinases, ATPases, GTPases, etc.) and receptor binding studies, providing highly quantitative readouts for specific target interactions [29].

- Cell-Based Assays: Utilize living cells to capture pathway effects or phenotypic changes, offering more physiologically relevant context. These include reporter gene assays, cell viability tests, second messenger signaling studies, and high-content imaging approaches that provide multiparametric readouts [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary HTS Assay Approaches

| Assay Type | Key Characteristics | Common Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical | Target-based, uses purified components, well-defined system | Enzyme inhibition, receptor binding, protein-protein interactions | High reproducibility, direct mechanism analysis, minimal interference |

| Cell-Based | Phenotypic, uses living cells, pathway-focused | Functional response, toxicity screening, pathway modulation | Physiological relevance, identifies cell-permeable compounds |

| High-Content Screening | Multiparametric, imaging-based, subcellular resolution | Complex phenotype analysis, multiparameter profiling, spatial information | Rich data collection, simultaneous multiple readouts |

Workflow: From Stock Plates to Assay Plates

The transition from stock plates to assay plates represents the physical implementation of HTS experimentation. This multi-stage process ensures that compounds are efficiently transferred from storage to active testing while maintaining integrity and tracking throughout the workflow. The creation of assay plates involves transferring nanoliter-scale liquid volumes from stock plates to corresponding wells in empty plates using precision liquid handling systems [2]. This replica plating approach preserves the spatial encoding of compounds, enabling accurate tracking of compound identity throughout the screening process. The critical importance of this transfer process lies in its impact on data quality—even minor inconsistencies in liquid handling can compromise experimental results and lead to false positives or negatives [30].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive HTS workflow from stock plates to hit identification

Detailed Protocol: Assay Plate Preparation

Materials and Equipment

- Source Plates: Stock compound plates (library), carefully catalogued and stored under appropriate conditions [2]

- Destination Plates: Appropriate microplate format (96, 384, 1536-well) compatible with detection systems [29]

- Liquid Handling System: Automated pipetting station or non-contact dispenser (e.g., I.DOT Liquid Handler) [30]

- Laboratory Automation: Robotic arms for plate movement between stations (optional but recommended for full automation) [2]

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Setup and Calibration

- Initialize liquid handling system according to manufacturer specifications

- Perform priming and calibration steps using appropriate solvents

- Verify tip alignment and liquid class settings for the specific solvents used (e.g., DMSO for compound libraries)

Plate Configuration Verification

- Confirm stock plate barcode identification and database mapping

- Validate destination plate type and orientation in the deck

- Cross-reference compound mapping database to ensure positional accuracy

Liquid Transfer Process

- Program transfer parameters based on desired final assay concentration

- Execute nanoliter-scale transfer (typically 10 nL to 1 μL range) from stock to assay plates [30]

- Implement mixing steps if intermediate dilution is required

- The I.DOT Liquid Handler can dispense 10 nL across a 96-well plate in 10 seconds and a 384-well plate in 20 seconds, demonstrating the efficiency of modern systems [30]

Quality Control Steps

- Perform visual inspection for meniscus consistency and absence of bubbles

- Verify liquid presence in all destination wells using capacitance or imaging technologies

- Document any transfer failures or anomalies for database annotation

Assay Component Addition

Final Plate Preparation

- Apply sealing membranes or lids if required by assay protocol

- Centrifuge plates briefly to ensure all liquid is at well bottom

- Transfer to incubation conditions or detection systems as required

Reaction Observation and Data Collection

Following assay plate preparation and incubation, measurement occurs across all plate wells using specialized detection systems. The measurement approach depends on assay design and may include manual microscopy for complex phenotypic observations or automated readers for high-speed data collection [2]. Automated analysis machines can conduct numerous measurements by shining polarized light on wells and measuring reflectivity (indicating protein binding) or employing various detection methodologies including fluorescence, luminescence, TR-FRET, fluorescence polarization, or absorbance [29] [2]. These systems output results as numerical grids mapping to individual wells, with high-capacity machines capable of measuring dozens of plates within minutes, generating thousands of data points rapidly [2]. For example, in a recent TR-FRET assay development for FAK-paxillin interaction inhibitors, researchers employed time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer to detect inhibitors of protein-protein interactions in a high-throughput format [31].

Data Analysis and Hit Selection

Quality Control Metrics

Robust quality assessment is fundamental to reliable HTS data interpretation. Several established metrics help distinguish between high-quality assays and those with potential systematic errors:

- Z'-factor: Measures the separation between positive and negative controls, with values between 0.5-1.0 indicating excellent assay quality [29]

- Signal-to-Background Ratio: Assesses the magnitude of response relative to baseline noise

- Signal Window: Evaluates the dynamic range between positive and negative controls

- Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD): Recently proposed metric for assessing data quality in HTS assays [2]

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Measures well-to-well and plate-to-plate variability

Table 2: Key Quality Control Metrics for HTS Assay Validation

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Optimal Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | 1 - (3σp + 3σn)/|μp - μn| | 0.5 - 1.0 | Excellent assay robustness and reproducibility |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | (μp - μn)/σn | >3 | Acceptable signal discrimination from noise |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (σ/μ) × 100 | <10% | Low well-to-well variability |

| Signal Window | (μp - μn)/(3σp + 3σn) | >2 | Sufficient dynamic range for hit detection |

Hit Selection Methods

Hit selection methodologies vary depending on screening design, particularly regarding the presence or absence of experimental replicates. The fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing true biological activity from random variation or systematic artifacts:

- Screens Without Replicates: Utilize z-score methods, SSMD, average fold change, percent inhibition, or percent activity, though these approaches assume every compound has similar variability to negative controls [2]

- Screens With Replicates: Employ t-statistics or SSMD that directly estimate variability for each compound, providing more reliable hit identification [2]

- Robust Methods: Address outlier sensitivity through z-score, SSMD, B-score, or quantile-based approaches that accommodate the frequent outliers in HTS experiments [2]

Statistical parameter estimation in HTS, particularly when using nonlinear models like the Hill equation, presents significant challenges. Parameter estimates such as AC50 (concentration for half-maximal response) and Emax (maximal response) can show poor repeatability when concentration ranges fail to establish both asymptotes or when responses are heteroscedastic [32]. As shown in simulation studies, AC50 estimates can span several orders of magnitude in unfavorable conditions, highlighting the importance of optimal study designs for reliable parameter estimation [32].

Diagram 2: HTS data analysis workflow with quality control and hit selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HTS Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function in HTS Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Testing vessel for assays with standardized well formats (96 to 3456+ wells) | Enable miniaturization and parallel processing; choice depends on assay volume and detection method [2] |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules for screening; range from diverse general libraries to target-focused sets | Quality and diversity critically impact screening success; must account for PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) [29] |

| Detection Reagents | Chemistry for signal generation (fluorescence, luminescence, TR-FRET, FP, absorbance) | Selection depends on assay compatibility and sensitivity requirements; TR-FRET ideal for protein-protein interactions [29] [31] |

| Cell Culture Components | For cell-based assays: cell lines, growth media, cytokines, differentiation factors | Essential for phenotypic screening; requires careful standardization to minimize biological variability [29] |

| Enzyme Systems | Purified enzymes with cofactors and substrates for biochemical assays | Provide defined system for target-based screening; Transcreener platform offers universal detection for multiple enzyme classes [29] |

| Automation-Compatible Reagents | Formulated for robotic liquid handling with appropriate viscosity and surface tension | Enable consistent performance across high-throughput platforms; reduce liquid handling failures [30] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The field of HTS continues to evolve with emerging technologies that enhance screening efficiency and data quality. Quantitative HTS (qHTS) represents a significant advancement by generating full concentration-response curves for each compound in a single screening campaign, providing richer pharmacological data upfront [2]. Recent innovations include the application of drop-based microfluidics, enabling screening rates 1,000 times faster than conventional techniques while using one-millionth the reagent volume [2]. These systems replace microplate wells with fluid drops separated by oil, allowing continuous analysis and hit sorting during flow through microfluidic channels [2]. Additional advances incorporate silicon lens arrays placed over microfluidic devices to simultaneously measure multiple fluorescence output channels, achieving analysis rates of 200,000 drops per second [2]. The integration of artificial intelligence and virtual screening with experimental HTS creates synergistic approaches that accelerate discovery timelines, while 3D cell cultures and organoids provide more physiologically relevant models for complex biological systems [29]. These technological advances, combined with increasingly sophisticated data analysis methods, continue to expand the capabilities and applications of high-throughput screening in drug discovery and biological research.

Advanced Assay Strategies: From Target-Based Screens to Complex Phenotypic Applications

Within high-throughput screening (HTS) assay development, the selection between target-based and phenotypic screening strategies represents a critical foundational decision that profoundly influences downstream research outcomes. Target-based screening employs a mechanistic approach, focusing on compounds that interact with a predefined, purified molecular target such as a protein or enzyme [33] [34]. Conversely, phenotypic screening adopts a biology-first, functional approach, identifying compounds based on their ability to produce a desired observable change in cells, tissues, or whole organisms without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [35] [36]. The strategic choice between these paradigms dictates the entire experimental workflow, technology investment, and potential for discovering first-in-class therapeutics. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal path for their specific drug discovery campaigns.

Comparative Analysis: Strategic Considerations for HTS Assay Development

The decision between target-based and phenotypic approaches requires careful evaluation of project goals, biological understanding of the disease, and available resources. Each strategy offers distinct advantages and faces specific limitations that impact their application in modern drug discovery pipelines.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Parameter | Target-Based Screening | Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Tests compounds against a predefined, purified molecular target [34] [37] | Identifies compounds based on observable effects in biological systems [36] |

| Discovery Bias | Hypothesis-driven, limited to known pathways and targets [36] | Unbiased, allows for novel target and mechanism identification [35] [36] |

| Mechanism of Action (MoA) | Defined from the outset [36] [37] | Often unknown at discovery, requires subsequent deconvolution [36] |

| Throughput Potential | Typically high [36] | Variable; modern advances enable higher throughput [38] |

| Technological Requirements | Recombinant technology, structural biology, enzyme assays [39] [37] | High-content imaging, functional genomics, AI/ML analysis [35] [38] [36] |

| Hit-to-Lead Optimization | Straightforward due to known target; enables efficient SAR [37] | Complex due to unknown MoA; requires early counter-screening [36] |

| Best-Suited Applications | Well-validated targets, rational drug design, repurposing campaigns [33] | Complex diseases, polygenic disorders, novel mechanism discovery [35] [33] [36] |

Target-based screening has contributed significantly to first-in-class medicines, with one analysis noting it accounted for 70% of such FDA approvals from 1999 to 2013 [37]. Its strength lies in mechanistic clarity, enabling rational drug design and efficient structure-activity relationship (SAR) development once a hit is identified [37]. However, this approach is inherently limited to known biology and may fail to capture the complex, polypharmacology often required for therapeutic efficacy in multifactorial diseases [35] [36].

Phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful strategy, particularly valuable when the molecular underpinnings of a disease are poorly understood [36]. It enables the discovery of first-in-class drugs with novel mechanisms of action, as compounds are selected based on functional therapeutic effects rather than predefined molecular interactions [33] [36]. This approach is especially powerful in complex disease areas like oncology, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases where cellular redundancy and compensatory mechanisms can render single-target approaches ineffective [35] [38]. The primary challenge remains target deconvolution—identifying the specific molecular mechanism through which active compounds exert their effects [36]. Recent advances in computational target prediction methods, such as MolTarPred, and integrative AI platforms are helping to address this historical bottleneck [38] [40].

Application Note 1: Implementing a Target-Based HTS Campaign

Protocol: Development of a Biochemical HTS Assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mycothione Reductase (MtrMtb) Inhibitors