From Molecules to Medicines: A Comprehensive Guide to Modern QSAR in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, a cornerstone computational methodology in modern drug discovery.

From Molecules to Medicines: A Comprehensive Guide to Modern QSAR in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, a cornerstone computational methodology in modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of QSAR, from its historical origins to its current transformation through artificial intelligence and machine learning. The scope encompasses classical and advanced methodological approaches, practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance, and rigorous frameworks for validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing these core intents, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging QSAR to accelerate lead identification, optimize candidate efficacy and safety, and ultimately reduce the high costs and extended timelines associated with pharmaceutical R&D.

What is QSAR? Understanding the Core Principles and Evolution in Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) is a fundamental methodology in computational chemistry and drug discovery that establishes a mathematical correlation between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activity [1] [2]. At its core, QSAR modeling applies statistical and machine learning techniques to predict the biological response of chemicals based on their molecular structures and physicochemical properties [1] [3]. The foundational principle of QSAR is that the biological activity of a compound can be expressed as a function of its structural and physicochemical properties, formally represented as: Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [1].

This approach has revolutionized modern pharmaceutical research by enabling faster, more accurate, and scalable identification of therapeutic compounds, significantly reducing the traditional reliance on trial-and-error methods in drug development [3]. The development of QSAR dates back to the 1960s when American chemist Corwin Hansch proposed Hansch analysis, which predicted biological activity by quantifying physicochemical parameters like lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects [4]. Over subsequent decades, QSAR has evolved from simple linear models using few interpretable descriptors to complex machine learning frameworks incorporating thousands of chemical descriptors [4].

Mathematical Foundations and Key Components

The QSAR Equation and Statistical Underpinnings

QSAR models mathematically relate a set of predictor variables (X) to the potency of a biological response (Y) through regression or classification techniques [1]. In regression models, the response variable is continuous, while classification models assign categorical activity values [1]. The fundamental mathematical relationship can be expressed as:

Biological Activity = f(physicochemical parameters) [2]

The "error" term in the QSAR equation encompasses both model error (bias) and observational variability that occurs even with a correct model [1]. The statistical methods employed range from traditional approaches like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Principal Component Regression (PCR) to more advanced machine learning algorithms including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) [3].

Essential Components of QSAR Modeling

Three critical elements form the foundation of any QSAR study, each requiring careful consideration and optimization [4]:

- Datasets: High-quality, curated datasets containing both structural information and experimentally derived biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀) for diverse chemical structures [4] [2]. The quality and representativeness of these datasets directly influence the model's predictive and generalization capabilities [4].

- Molecular Descriptors: Numerical representations encoding chemical, structural, or physicochemical properties of compounds [3]. These can be classified by dimensions as 1D (e.g., molecular weight), 2D (e.g., topological indices), 3D (e.g., molecular shape, electrostatic potentials), or 4D (accounting for conformational flexibility) [3].

- Mathematical Models: Algorithms that establish the functional relationship between descriptors and biological activity [4]. With the rise of machine learning and deep learning, models have become increasingly sophisticated, capable of capturing complex nonlinear patterns across expansive chemical spaces [4] [3].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors Used in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Dimension | Description | Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Based on overall molecular composition and bulk properties [3] | Molecular weight, pKa, log P (partition coefficient) [3] [2] | Simple to compute, provide general molecular characteristics |

| 2D Descriptors | Derived from molecular topology and structural patterns [2] | Topological indices, hydrogen bond counts, molecular refractivity [3] [2] | Capture connectivity information; invariant to molecular conformation |

| 3D Descriptors | Represent molecular shape and electronic distributions in 3D space [1] [3] | Steric parameters, electrostatic potentials, molecular surface area [1] [3] | Account for stereochemistry and spatial arrangements |

| 4D Descriptors | Incorporate conformational flexibility over ensembles of structures [3] | Conformer-based properties, interaction pharmacophores [3] | Provide more realistic representations under physiological conditions |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | Derived from quantum mechanical calculations [3] | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, molecular orbital energies [3] | Describe electronic properties influencing reactivity and bioactivity |

QSAR Workflow and Methodological Approaches

Essential Steps in QSAR Modeling

The development of a robust QSAR model follows a systematic workflow comprising four principal stages [1]:

- Selection of Data Set and Extraction of Descriptors: Curating a representative set of compounds with known biological activities and computing relevant molecular descriptors [1].

- Variable Selection: Identifying the most relevant descriptors that significantly contribute to the biological activity while eliminating redundant or irrelevant variables to prevent overfitting [1] [3].

- Model Construction: Applying statistical or machine learning algorithms to establish the mathematical relationship between selected descriptors and the biological response [1].

- Validation and Evaluation: Rigorously assessing the model's predictive performance, robustness, and domain of applicability using various validation strategies [1].

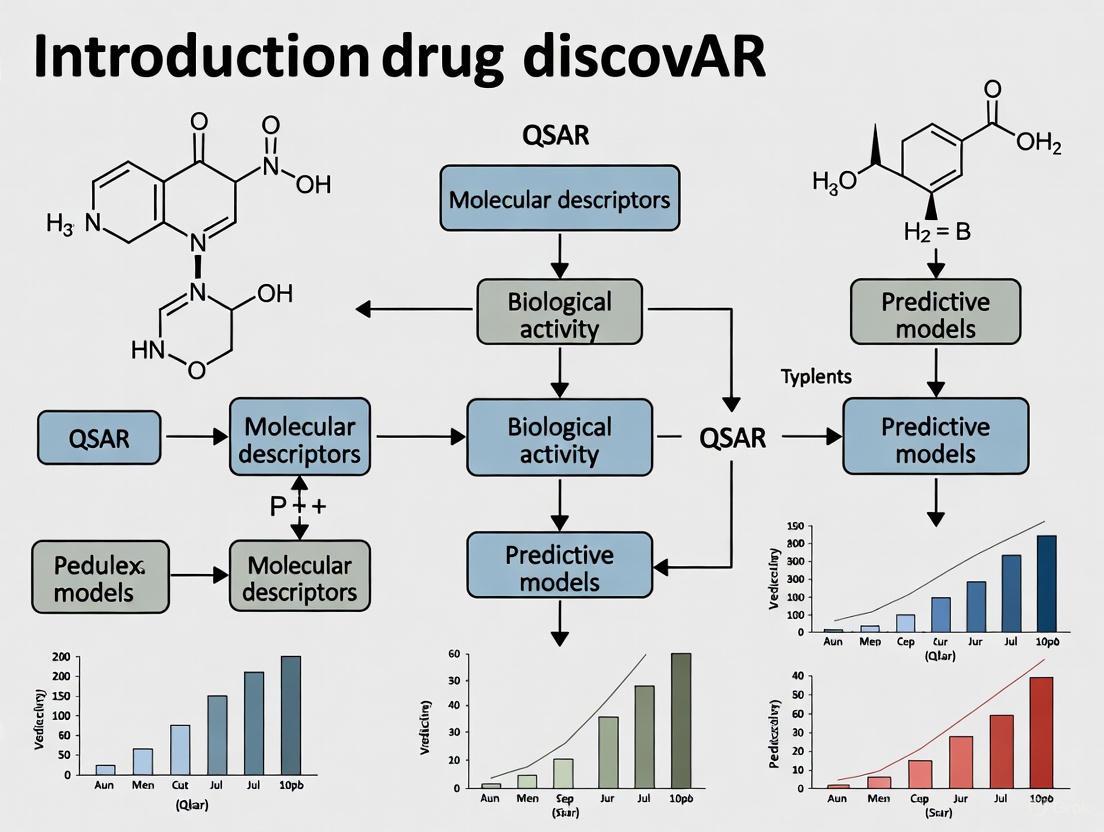

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive QSAR modeling workflow:

Types of QSAR Modeling Techniques

Various QSAR methodologies have been developed, each with distinct approaches to representing and analyzing molecular structures:

Fragment-Based (Group Contribution) QSAR: This approach, also known as GQSAR, predicts properties based on molecular fragments or substituents [1]. It operates on the principle that molecular properties can be determined by summing contributions from constituent fragments [1]. Advanced implementations include pharmacophore-similarity-based QSAR (PS-QSAR), which uses topological pharmacophoric descriptors to understand how specific pharmacophore features influence activity [1].

3D-QSAR: This methodology employs force field calculations requiring three-dimensional structures of molecules with known activities [1]. The first 3D-QSAR approach was Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), which examines steric and electrostatic fields around molecules and correlates them using partial least squares regression [1]. These models require careful molecular alignment based on either experimental data (e.g., ligand-protein crystallography) or computational superimposition [1].

Chemical Descriptor-Based QSAR: This approach computes descriptors quantifying various electronic, geometric, or steric properties of an entire molecule rather than individual fragments [1]. Unlike 3D-QSAR, these descriptors are computed from scalar quantities rather than 3D fields [1].

AI-Integrated QSAR: Modern QSAR incorporates advanced machine learning and deep learning approaches, including graph neural networks and SMILES-based transformers, which can capture complex nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional chemical data [3]. These methods enable virtual screening of extensive chemical databases containing billions of compounds and facilitate de novo drug design [3].

Table 2: Comparison of QSAR Modeling Techniques

| Modeling Technique | Core Principle | Typical Algorithms | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Statistical QSAR | Linear correlation between descriptors and activity [3] | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS) [3] | Preliminary screening, mechanism clarification, regulatory toxicology [3] |

| Machine Learning QSAR | Capturing complex nonlinear patterns [3] | Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, k-Nearest Neighbors [3] | Virtual screening, toxicity prediction with high-dimensional data [3] |

| 3D-QSAR | Analyzing 3D molecular interaction fields [1] | CoMFA, CoMSIA [1] | Lead optimization studying steric and electrostatic requirements |

| Deep Learning QSAR | Learning hierarchical representations from raw molecular data [3] | Graph Neural Networks, Transformers, Autoencoders [3] | De novo drug design, predicting properties of novel chemotypes |

The hierarchy of QSAR modeling techniques, from traditional to AI-integrated approaches, is visualized below:

Model Validation and Quality Assessment

Validation Protocols and Techniques

Rigorous validation is crucial for developing reliable QSAR models [1]. Several validation strategies are routinely employed:

- Internal Validation/Cross-Validation: Assesses model robustness by systematically omitting portions of the training data and evaluating prediction accuracy [1]. Leave-one-out cross-validation, while common, may overestimate predictive capacity and should be interpreted cautiously [1].

- External Validation: Involves splitting the available dataset into separate training and prediction sets to objectively test model performance on unseen compounds [1] [4].

- Data Randomization (Y-Scrambling): Verifies the absence of chance correlations between the response variable and molecular descriptors by randomly permuting activity values while keeping descriptor matrices unchanged [1].

- Applicability Domain (AD) Assessment: Defines the chemical space within which the model can reliably predict compound activity based on the training set's structural and response characteristics [1] [4].

Evaluation Metrics and Quality Standards

A high-quality QSAR model must meet several critical criteria [2]:

- Defined Endpoint: The specific biological activity or property being modeled must be clearly specified [2].

- Unambiguous Algorithm: The mathematical model should produce consistent, interpretable predictions without vague results [2].

- Defined Domain of Applicability: Clearly established boundaries for the physicochemical, structural, or biological space where the model is valid [2].

- Appropriate Measure of Goodness-of-Fit: Statistical metrics that quantify how well the model fits the observed data while maintaining predictive power for new compounds [2].

Common statistical metrics for evaluating QSAR models include R² (coefficient of determination) for goodness-of-fit and Q² (cross-validated R²) for predictive ability [3]. However, these metrics should be interpreted in the context of the model's intended application and applicability domain [1].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Beyond

Pharmaceutical Applications

QSAR modeling has become indispensable in modern drug discovery pipelines, with several critical applications:

- Virtual Screening and Lead Identification: Rapid in silico screening of large chemical databases to identify potential hit compounds with desired biological activities, significantly reducing experimental costs and time [3] [2].

- Lead Optimization: Guiding structural modifications of lead compounds to enhance potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties while reducing undesirable characteristics [4] [2].

- ADMET Prediction: Forecasting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties early in the drug development process to eliminate candidates with poor pharmacokinetic or safety profiles [3].

- De Novo Drug Design: Generating novel molecular structures with optimized biological activities using generative models and AI-driven approaches [3].

Recent applications demonstrate QSAR's continued relevance: Talukder et al. integrated QSAR with docking and simulations to prioritize EGFR-targeting phytochemicals for non-small cell lung cancer [3]; Kaur et al. developed BBB-permeable BACE-1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease using 2D-QSAR [3]; and researchers have applied QSAR-driven virtual screening to identify potential therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2 and Trypanosoma cruzi [3] [2].

Table 3: Key Software Tools for QSAR Analysis

| Software Tool | Type | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial platform [5] | Diverse QSAR models, high-quality visualization, bioinformatics interface [5] | Comprehensive drug discovery, peptide modeling [5] |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial platform [5] | User-friendly QSAR modeling, molecular dynamics, protein modeling [5] | Integrated drug discovery workflows [5] |

| QSAR Toolbox | Free software [6] | Data gap filling, read-across, category formation, metabolic simulation [6] | Regulatory chemical assessment, toxicity prediction [6] |

| Open3DQSAR | Open-source tool [5] | 3D-QSAR analysis, transparency in analytical processes [5] | Academic research, method development [5] |

| Python | Programming language [5] | High flexibility, extensive cheminformatics libraries, custom algorithm development [5] | Custom QSAR pipeline development, research prototyping [5] |

| ADMEWORKS ModelBuilder | Commercial tool [5] | ADMET prediction integration, highly customizable modules [5] | Drug discovery focusing on pharmacokinetic optimization [5] |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of QSAR modeling is increasingly intertwined with artificial intelligence and large-scale data integration [4] [3]. Several emerging trends are shaping the next generation of QSAR approaches:

- Universal QSAR Models: Development of broadly applicable models capable of predicting activities across diverse chemical spaces and biological targets remains a primary objective, though it poses significant challenges regarding dataset comprehensiveness, descriptor accuracy, and model flexibility [4].

- Explainable AI (XAI): Addressing the "black box" nature of complex machine learning models through techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to enhance model interpretability and regulatory acceptance [3].

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: Combining structural information with omics data, real-world evidence, and physiological parameters to create more predictive and clinically relevant models [3].

- Federated Learning: Enabling secure, collaborative model training across institutions without sharing proprietary data, thus expanding training datasets while maintaining privacy [7].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in areas of model interpretability, regulatory standards, ethical considerations, and the need for larger, higher-quality, and more diverse chemical datasets [4] [3]. As these challenges are addressed, QSAR will continue to evolve as an indispensable tool in molecular design and drug discovery, playing an increasingly important role in various scientific disciplines [4].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design, providing a critical methodology for predicting the biological activity of compounds based on their chemical structures [8]. For six decades, QSAR has served as an invaluable in silico tool that enables researchers to test and classify new compounds with desired properties, substantially reducing the need for extensive laboratory experimentation [9]. The fundamental premise underlying all QSAR approaches is that chemical structure quantitatively determines biological activity, a principle that can be mathematically formalized to accelerate therapeutic development [8]. The evolution of QSAR methodologies—from early linear regression models to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches—demonstrates a remarkable trajectory of technological advancement that has progressively enhanced predictive accuracy, interpretability, and efficiency in drug discovery pipelines [10].

The significance of QSAR modeling is particularly evident in modern pharmacological studies, where it is extensively employed to predict pharmacokinetic processes such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), as well as toxicity profiles [9]. By establishing mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological responses, QSAR models enable researchers to prioritize promising candidate molecules for synthesis and experimental validation, thereby streamlining the drug discovery process [8]. This review comprehensively traces the historical development of QSAR modeling, examines current methodologies incorporating deep learning, and explores emerging directions that promise to further transform computational drug discovery.

Historical Development of QSAR Modeling

Early Foundations and Classical Approaches

The conceptual foundations of QSAR emerged in the 19th century when Crum-Brown and Fraser first proposed that the physicochemical properties and biological activities of molecules depend on their chemical structures [8]. However, the field truly began to formalize in the 1960s with the pioneering work of Corwin Hansch and Toshio Fujita, who developed the first quantitative approaches to correlate biological activity with hydrophobic, electronic, and steric parameters through linear free-energy relationships [10]. This established the paradigm that molecular properties could be numerically represented and statistically correlated with biological outcomes.

Traditional QSAR modeling initially relied heavily on multiple linear regression (MLR) techniques, which constructed mathematical equations correlating biological activity (the dependent variable) with chemical structure information encoded as molecular descriptors (independent variables) [8]. These linear models provided a straightforward and interpretable framework for establishing structure-activity relationships, making them widely adopted in early drug discovery efforts. The general form of these relationships can be expressed as:

Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃…) where D₁, D₂, D₃, … are Molecular Descriptors [8].

The classical QSAR workflow involved several methodical steps: (1) collecting experimental biological activity data for a series of compounds; (2) calculating molecular descriptors to numerically represent chemical structures; (3) selecting the most relevant descriptors; (4) deriving a mathematical model correlating descriptors with activity; and (5) validating the model's predictive capability [8]. This process represented a significant advancement in rational drug design, moving beyond serendipitous discovery toward systematic molecular optimization.

Table 1: Evolution of QSAR Modeling Approaches Across Decades

| Time Period | Dominant Methodologies | Key Advances | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1980s | Linear Regression, Hansch Analysis | First quantitative approaches, Establishment of LFER principles | Limited computational power, Simple linear assumptions |

| 1990s-2000s | MLR, Partial Least Squares, Bayesian Neural Networks | Multivariate techniques, Early machine learning integration | Handling of high-dimensional data, Limited non-linear capability |

| 2000s-2010s | Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, ANN | Ensemble methods, Kernel techniques, Basic neural networks | Interpretability challenges, Data hunger |

| 2010s-Present | Deep Learning, Graph Neural Networks, Transformers | Representation learning, End-to-end modeling, Quantum enhancements | Black-box nature, Extensive data requirements |

The Shift Toward Machine Learning

As chemical datasets grew in size and complexity, classical linear regression approaches revealed significant limitations in capturing the intricate, non-linear relationships between molecular structure and biological activity [9]. This prompted a gradual transition toward machine learning techniques that could better handle high-dimensional descriptor spaces and complex structure-activity landscapes. Random Forest algorithms emerged as particularly effective tools for QSAR modeling, with their ensemble approach combining multiple decision trees to achieve superior predictive performance [9]. This method offered several advantages, including built-in performance evaluation, descriptor importance measures, and compound similarity computations weighted by the relative importance of descriptors [9].

The adoption of Bayesian neural networks represented another significant advancement, demonstrating remarkable ability to distinguish between drug-like and non-drug-like molecules with high accuracy [9]. These models showed excellent generalization capabilities, correctly classifying more than 90% of compounds in databases while maintaining low false positive rates [9]. Similarly, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with various kernel functions gained popularity for their effectiveness in navigating complex chemical spaces and identifying non-linear decision boundaries [9] [11]. These machine learning approaches substantially expanded the applicability and predictive power of QSAR models while introducing new challenges related to model interpretability and computational demands.

Modern AI-Driven QSAR Approaches

Deep Learning and the Emergence of Deep QSAR

The past decade has witnessed the emergence of deep QSAR, a transformative approach fueled by advances in artificial intelligence techniques, particularly deep learning, alongside the rapid growth of molecular databases and dramatic improvements in computational power [10]. Deep learning architectures have fundamentally reshaped QSAR modeling by enabling end-to-end learning directly from molecular representations, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering and descriptor calculation [10].

A significant innovation in this domain is the development of graph neural networks (GNNs), such as Chemprop, which use directed message-passing neural networks to learn molecular representations directly from molecular graphs [11]. These models have demonstrated exceptional performance in various drug discovery applications, including antibiotic discovery and lipophilicity prediction [11]. Concurrently, transformer-based architectures applied to Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings have leveraged the attention mechanism to enable transfer learning from pre-trained models to specific activity prediction tasks [11]. These approaches capture complex molecular patterns without relying on explicitly defined descriptors, instead learning relevant features directly from the data during training.

Table 2: Comparison of Modern AI-Based QSAR Approaches

| Methodology | Molecular Representation | Key Advantages | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Molecular graphs | Direct structure learning, No descriptor calculation | Chemprop for antibiotic discovery, Molecular property prediction |

| SMILES-based Transformers | SMILES strings | Transfer learning potential, Attention mechanisms | Pre-training with masked SMILES recovery, Activity prediction |

| Topological Regression (TR) | Molecular fingerprints | Interpretability, Handling of activity cliffs | Similarity-based prediction, Chemical space visualization |

| Quantum SVM (QSVM) | Quantum-encoded features | Potential quantum advantage, Hilbert space processing | Early exploration for classification tasks |

Interpretable AI and Similarity-Based Approaches

Despite their impressive predictive performance, deep learning models often function as "black boxes," providing limited insight into the structural features driving their predictions [11]. This interpretability challenge has prompted the development of alternative approaches that maintain predictive power while offering greater transparency. Topological regression (TR) has emerged as a particularly promising framework that combines the advantages of similarity-based methods with adaptive metric learning [11]. This technique models distances in the response space using distances in the chemical space, essentially building a parametric model to determine how pairwise distances in the chemical space impact the weights of nearest neighbors in the response space [11].

The Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) and Chemical Similarity Network Analysis Pulldown (CSNAP) represent other innovative similarity-based methods that enable visualization of drug-target interaction networks and prediction of off-target drug interactions [11]. These approaches have led to deeper investigations into drug polypharmacology and the discovery of off-target drug interactions [11]. For traditional machine learning models, techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) provide model-agnostic methods for calculating prediction-wise feature importance, while Molecular Model Agnostic Counterfactual Explanations (MMACE) generate counterfactual explanations that help identify structural changes that would alter biological outcomes [11].

Quantum-Enhanced QSAR

The integration of quantum computing principles with QSAR modeling represents the frontier of methodological innovation in the field. Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVMs) leverage quantum computing principles to process information in Hilbert spaces, potentially offering advantages for handling high-dimensional data and capturing complex molecular interactions [9]. By employing quantum data encoding and quantum kernel functions, these approaches aim to develop more accurate and efficient predictive models [9]. While still in early stages of exploration, quantum-enhanced QSAR methodologies anticipate future computational paradigms that may dramatically accelerate virtual screening and molecular optimization processes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Classical QSAR Workflow: A Case Study on PLK1 Inhibitors

The classical QSAR approach is exemplified by a comprehensive study of 530 polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) inhibitors compiled from the ChEMBL database [12]. This research followed a meticulous conformation-independent QSAR methodology that captures the essential elements of traditional workflow:

Step 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation

- The structurally diverse PLK1 inhibitors were compiled from ChEMBL, an open data resource of binding, functional, and ADMET bioactivity data [12].

- Experimental inhibitory effectiveness was expressed as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) in nM, with values ranging from 0.8 to 145,000 nM [12].

- After removing duplicates, compounds with ambiguous data, compounds with molecular weights >1000 g·mol⁻¹, and compounds without reported bioactivities, the final dataset consisted of 530 compounds [12].

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- The researchers computed 26,761 non-conformational molecular descriptors using multiple software tools to capture diverse structural characteristics [12].

- PaDEL software was used to calculate 1,444 0D-2D descriptors and 12 fingerprint types (16,092 bits) that involve the presence or count of specific chemical substructures [12].

- Mold2 generated 777 1D-2D structural variables from molecules in MDL sdf format [12].

- QuBiLs-MAS algebraic module calculated 8,448 quadratic, bilinear, and linear maps based on pseudograph-theoretic electronic-density matrices and atomic weightings [12].

Step 3: Descriptor Selection and Model Development

- After identifying collinear descriptor pairs and excluding non-informative descriptors, the researchers obtained a pool of 11,565 linearly independent non-conformational descriptors [12].

- The Replacement Method (RM) technique was employed to generate multivariable linear regression (MLR) models on the training set by searching for optimal subsets containing d descriptors (where d is much lower than D) with the smallest values for the standard deviation [12].

- The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using the balanced subsets method (BSM) to ensure similar structure-activity relationships across all subsets [12].

Figure 1: Classical QSAR Workflow for PLK1 Inhibitor Modeling

Modern AI-Driven QSAR Protocol: Tankyrase Inhibitor Identification

A contemporary QSAR approach integrating machine learning was demonstrated in a study targeting tankyrase (TNKS2) inhibitors for colorectal cancer treatment [13]. This protocol highlights the methodological shifts introduced by AI technologies:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

- A dataset of 1,100 TNKS2 inhibitors was retrieved from the ChEMBL database (target ID: CHEMBL6125) [13].

- Ligand-based QSAR modeling was employed to predict potent chemical scaffolds based on 2D and 3D structural and physicochemical molecular descriptors [13].

- Machine learning approaches, specifically feature selection algorithms and random forest (RF) classification models, were applied to enhance model reliability [13].

Step 2: Model Training and Optimization

- Models were trained, optimized, and rigorously validated using internal (cross-validation) and external test sets [13].

- The random forest model achieved high predictive performance with a ROC-AUC of 0.98, demonstrating the power of ensemble learning methods for classification tasks [13].

- Virtual screening of prioritized candidates was complemented by molecular docking, dynamic simulation, and principal component analysis to evaluate binding affinity, complex stability, and conformational landscapes [13].

Step 3: Validation and Experimental Integration

- Network pharmacology contextualized TNKS within colorectal cancer biology, mapping disease-gene interactions and functional enrichment to uncover TNKS-associated roles in oncogenic pathways [13].

- This integrated computational strategy led to the identification of Olaparib as a potential TNKS inhibitor, demonstrating drug repurposing applications through AI-driven QSAR [13].

Figure 2: Modern AI-Driven QSAR Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for QSAR Modeling

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Databases for QSAR Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Database | Open data resource of bioactive molecules | Source of experimental bioactivity data for model training |

| PaDEL | Software | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generates 1,444 0D-2D descriptors and molecular fingerprints |

| Mold2 | Software | Molecular descriptor generation | Computes 777 1D-2D structural variables from molecular structures |

| QuBiLs-MAS | Software | Algebraic descriptor calculation | Calculates bilinear and linear maps based on electronic-density matrices |

| RDKit | Software | Cheminformatics toolkit | Provides molecular representation and descriptor calculation capabilities |

| Gnina | Software | Deep learning-based molecular docking | Uses convolutional neural networks for pose scoring and binding affinity prediction |

| Chemprop | Software | Graph neural network implementation | Learns molecular representations directly from graphs for property prediction |

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

Performance Evaluation Across Methodologies

The evolution from classical to AI-driven QSAR approaches has yielded substantial improvements in predictive accuracy and applicability domains. A systematic comparison of various techniques applied to 121 nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitors revealed distinct performance characteristics across methodologies [8]. In this comprehensive assessment, multiple linear regression (MLR) models provided reasonable predictive capability with the advantage of straightforward interpretability, while artificial neural networks (ANNs) demonstrated superior reliability and prediction accuracy, particularly with an [8.11.11.1] architecture [8]. Similar patterns have been observed across diverse target classes, with deep learning models consistently outperforming traditional approaches for complex structure-activity relationships.

The performance advantage of AI-driven approaches becomes particularly evident when analyzing large and structurally diverse datasets. In a benchmark study comparing topological regression (TR) against deep-learning-based QSAR models across 530 ChEMBL human target activity datasets, the sparse TR model achieved equal, if not better, performance than deep learning models while providing superior intuitive interpretation [11]. This demonstrates that interpretability need not be sacrificed for predictive power when employing appropriately designed modern algorithms. Similarly, the integration of graph neural networks with classical descriptor-based approaches has shown complementary strengths, with each method excelling in different regions of chemical space [14].

Addressing Fundamental Challenges: Activity Cliffs and Interpretability

A persistent challenge in QSAR modeling is the presence of activity cliffs—pairs of compounds with similar molecular structures but large differences in potency against their target [11]. The existence of activity cliffs often causes QSAR models to fail, especially during lead optimization [11]. Modern AI approaches address this limitation through various strategies. Metric Learning Kernel Regression (MLKR) employs supervised metric learning to incorporate target activity information, resulting in smoother activity landscapes that better separate chemically-similar-but-functionally-different molecules [11]. Similarly, topological regression models distances in the response space using distances in the chemical space, effectively handling activity cliffs by adaptively weighting nearest neighbors based on the local structure-activity landscape [11].

The interpretability challenge inherent in complex AI models has prompted the development of innovative explanation techniques. Layer-wise Relevance Propagation provides structural interpretation of atoms and bonds in graph-based models, while salient maps highlight substructures closely related to model outputs [11]. These methodologies help bridge the gap between predictive performance and actionable insights, enabling medicinal chemists to make informed decisions about molecular optimization based on computational predictions.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Directions

The trajectory of QSAR modeling continues to evolve with several promising frontiers emerging. Quantum computing applications in QSAR represent a particularly transformative direction, with quantum kernel methods and quantum neural networks potentially offering exponential speedups for specific computational tasks [9] [10]. While still in early stages of exploration, quantum-enhanced QSAR methodologies may eventually enable the efficient exploration of enormous chemical spaces that are currently computationally intractable.

The integration of generative AI with QSAR models represents another significant frontier, enabling de novo molecular design conditioned on desired activity profiles [14] [10]. Approaches such as PoLiGenX directly address correct pose prediction by conditioning the ligand generation process on reference molecules located within specific protein pockets, generating ligands with favorable poses that have reduced steric clashes and lower strain energies [14]. This synergy between generative models and predictive QSAR approaches creates a powerful feedback loop for accelerating molecular discovery.

The emerging paradigm of democratized QSAR through open-source platforms and cloud-based resources promises to make advanced AI-driven drug discovery accessible to broader research communities [10]. Initiatives such as public molecular databases, standardized benchmarking platforms, and reproducible model architectures are helping establish best practices while lowering barriers to entry [14] [10]. This collaborative ecosystem, combined with methodological advances in interpretability and reliability, positions QSAR modeling for continued impact on pharmaceutical research in the coming decades.

The historical trajectory of QSAR modeling—from its origins in linear regression to contemporary AI-driven approaches—demonstrates a remarkable evolution in computational drug discovery. Classical methodologies established fundamental principles of quantitative structure-activity relationships and provided interpretable models that remain valuable for specific applications. The integration of machine learning techniques substantially expanded the scope and predictive power of QSAR approaches, enabling navigation of complex chemical spaces and identification of non-linear structure-activity relationships. Current deep learning architectures have further transformed the field through representation learning and end-to-end modeling, while emerging quantum-enhanced methods anticipate future computational paradigms.

This methodological progression has consistently addressed core challenges in drug discovery: expanding applicability domains, improving predictive accuracy, enhancing interpretability, and increasing computational efficiency. The convergence of AI-driven QSAR with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop that accelerates the identification and optimization of therapeutic compounds. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of generative modeling, quantum computation, and democratized platforms promises to further transform QSAR's role in pharmaceutical research, ultimately contributing to more efficient and effective drug development pipelines that can address unmet medical needs across diverse disease areas.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a computational methodology that mathematically links the chemical structure of compounds to their biological activity or physicochemical properties. As a cornerstone of ligand-based drug design, QSAR plays a crucial role in modern drug discovery by enabling the prediction of compound activity, prioritizing synthesis candidates, and guiding the optimization of lead compounds [15]. The fundamental principle underpinning QSAR is that molecular structure variations systematically influence biological activity, allowing for the development of predictive models that can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with experimental screening [16] [17]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the essential steps in QSAR model development, framed within the broader context of drug discovery research. We will explore the comprehensive workflow from data collection to model deployment, with particular emphasis on the critical phases of data curation, descriptor calculation, and model construction, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the methodological foundation necessary for building robust, predictive QSAR models.

The development of a reliable QSAR model follows a systematic, multi-stage process. Each phase builds upon the previous one, with rigorous validation ensuring the final model's predictive capability and applicability to new chemical entities. The complete workflow integrates both computational and statistical elements, transforming raw chemical data into validated predictive tools.

Figure 1. Comprehensive QSAR Model Development Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential, interdependent stages in building a validated QSAR model, from initial data preparation to final deployment.

Data Curation: The Foundation of Reliable Models

Data curation constitutes the critical foundation upon which all subsequent QSAR modeling efforts are built. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is particularly relevant in QSAR modeling, as the predictive power and reliability of the final model are directly dependent on the quality and consistency of the input data [16].

Dataset Collection and Experimental Data Compilation

The initial phase involves compiling a dataset of chemical structures and their associated biological activities from reliable sources such as literature, patents, and public or private databases [16]. The biological activity is typically expressed as quantitative measures like IC₅₀ (half-maximal inhibitory concentration), EC₅₀ (half-maximal effective concentration), or Kᵢ (inhibition constant). For atmospheric reaction QSARs, as in a study predicting VOC degradation, this could include reaction rate constants (kOH, kO3, kNO3) [18]. It is crucial that the dataset covers a diverse chemical space relevant to the problem domain and that all biological activities are converted to a common unit and scale, typically through logarithmic transformation (e.g., pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀)) to normalize the distribution [16].

Data Cleaning and Standardization

Chemical structure standardization ensures consistency across the dataset and includes processes such as removing salts, neutralizing charges, standardizing tautomers, and handling stereochemistry [16]. This step is essential for obtaining accurate and consistent molecular descriptors in subsequent phases. Additionally, identifying and handling outliers or erroneous data entries is necessary to prevent model skewing. For example, in a study on PfDHODH inhibitors for malaria, the initial data was carefully curated from the ChEMBL database before model development [19].

Data Splitting Strategies

The cleaned dataset must be divided into training, validation, and external test sets. The training set is used to build the models, the validation set tunes model hyperparameters and selects the final model, while the external test set is reserved exclusively for final model assessment and must remain independent of model tuning and selection [16]. Common splitting methods include random selection and the Kennard-Stone algorithm, which ensures the test set is representative of the chemical space covered by the training set [16]. For the modeling of NF-κB inhibitors, researchers randomly allocated approximately 66% of the 121 compounds to the training set [8].

Molecular Descriptors: Quantifying Chemical Structure

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that encode structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties of molecules, serving as the independent variables in QSAR models [16]. The appropriate selection and calculation of these descriptors is crucial for capturing the structure-activity relationship.

Types of Molecular Descriptors

Descriptors can be categorized based on the dimensionality and type of structural information they encode:

Table 1. Categories of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Based on molecular formula and bulk properties | Molecular weight, atom count, bond count, logP [17] | Preliminary screening, simple property prediction |

| 2D Descriptors | Derived from molecular topology/connectivity | Topological indices, connectivity indices, molecular fingerprints (ECFP) [20] [17] | Standard QSAR, similarity searching |

| 3D Descriptors | Dependent on molecular geometry/conformation | Molecular surface area, volume, polar surface area [17] | Receptor-ligand interaction modeling |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | From electronic structure calculations | HOMO/LUMO energies, dipole moment, electrostatic potential [18] [17] | Modeling reaction rates, electronic properties |

In a multi-target QSAR model for VOC degradation, quantum chemical descriptors such as EHOMO (energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital) and the electrophilic Fukui index (f(-)x) were identified as critical parameters influencing degradation rates [18].

Descriptor Calculation and Software Tools

Numerous software packages enable the calculation of molecular descriptors, making this process highly accessible to researchers.

Table 2. Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation

| Software Tool | Features | Descriptor Types | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Calculates 2D and 1D descriptors and fingerprints | Constitutional, topological, electronic | Free [16] |

| Dragon | Comprehensive descriptor calculation platform | 0D-3D descriptors, molecular fingerprints | Commercial [16] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics library with descriptor calculation | 2D, 3D, topological descriptors | Open-source [16] |

| Mordred | Calculates over 1800 molecular descriptors | Constitutional, topological, geometric | Free [16] |

Feature Selection and Model Construction

With hundreds to thousands of descriptors potentially available, feature selection becomes essential to avoid overfitting and to build interpretable models. Subsequently, appropriate machine learning algorithms are employed to construct the predictive relationship between descriptors and activity.

Feature Selection Methods

Feature selection techniques identify the most relevant molecular descriptors, improving model performance and interpretability while reducing computational complexity [16] [17].

- Filter Methods: Rank descriptors based on their individual correlation or statistical significance with the target activity (e.g., correlation coefficient, ANOVA) [16].

- Wrapper Methods: Use the modeling algorithm itself to evaluate different subsets of descriptors through iterative processes (e.g., genetic algorithms, simulated annealing) [16].

- Embedded Methods: Perform feature selection as part of the model training process (e.g., LASSO regression, random forest feature importance) [20] [16]. For instance, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) applies a penalty that drives less important coefficients to zero, effectively selecting a sparse set of meaningful features [17].

Model Building Algorithms

The choice of modeling algorithm depends on the complexity of the structure-activity relationship, dataset size, and desired interpretability.

Table 3. QSAR Modeling Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm | Type | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Linear [8] [16] | Simple, interpretable, provides explicit equation [8] | Linear relationships, mechanistic interpretation [8] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Linear [16] | Handles multicollinearity, reduces dimensionality [20] | Highly correlated descriptors [20] |

| Random Forest (RF) | Non-linear [19] | Robust, handles noise, provides feature importance [19] | Complex relationships, feature interpretation [19] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Non-linear [16] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile kernels | Small to medium datasets with non-linearity |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Non-linear [8] [16] | Captures complex patterns, high predictive power [8] | Large datasets with intricate structure-activity relationships [8] |

In a comparative study of NF-κB inhibitors, both MLR and ANN models were developed, with the ANN model demonstrating superior predictive performance, highlighting its capacity to capture non-linear relationships in the data [8].

Model Validation and Applicability Domain

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure a QSAR model's predictive reliability and applicability to new compounds. This process assesses the model's robustness, predictive power, and domain of applicability.

Validation Techniques

A comprehensive validation strategy incorporates both internal and external validation techniques:

- Internal Validation: Uses the training data to estimate model performance, typically through cross-validation techniques such as k-fold cross-validation or leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation [16]. In k-fold cross-validation, the training set is divided into k subsets; the model is trained on k-1 subsets and validated on the remaining subset, with the process repeated k times [16].

- External Validation: Assesses model performance on a completely independent test set that was not used during model development or training [16]. This provides the most realistic estimate of a model's predictive power on novel compounds.

Validation Metrics and Applicability Domain

Different metrics are used to evaluate model performance based on the type of model (regression vs. classification):

Table 4. Key Validation Metrics for QSAR Models

| Metric | Formula/Definition | Interpretation | Preferred Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | Proportion of variance explained by model | Goodness of fit for training data | Closer to 1 |

| Q² (Cross-validated R²) | Predictive ability from cross-validation | Model robustness and internal predictive power | > 0.5 for reliable model |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | √[Σ(Ŷᵢ - Yᵢ)²/n] | Average prediction error in activity units | Closer to 0 |

| MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) | Used for binary classification models | Balanced measure for binary classification | Range -1 to +1, closer to +1 |

The applicability domain defines the chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions based on the training set's structural and response characteristics [8]. Methods like the leverage approach can determine whether a new compound falls within this domain [8].

Figure 2. QSAR Model Validation Process. This workflow depicts the multi-faceted validation approach required to establish model reliability, including internal and external validation, applicability domain definition, and statistical evaluation.

Successful QSAR modeling requires a combination of software tools, computational resources, and methodological knowledge. The following table details key resources essential for implementing the QSAR workflow described in this guide.

Table 5. Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Features | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNIME Analytics Platform | Data analytics platform with cheminformatics extensions [21] | Implements data curation and ML workflows for QSAR [21] | Workflow implementation for data curation and model building [21] |

| scikit-learn | Python ML library | Comprehensive regression and classification algorithms | Model building, feature selection, and validation |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Grouping and read-across tool for chemical hazard assessment | Supports regulatory use of QSAR models | Data curation and regulatory application [22] |

| Apheris Federated Learning Platform | Privacy-preserving collaborative modeling [23] | Enables training on distributed datasets without data sharing [23] | Building models with expanded chemical space coverage [23] |

QSAR modeling represents a powerful methodology for linking chemical structure to biological activity, playing an indispensable role in modern drug discovery. The development of robust, predictive models requires meticulous attention to each step of the workflow: comprehensive data curation, appropriate descriptor calculation and selection, judicious choice of modeling algorithms, and rigorous validation. The integration of advanced machine learning techniques, coupled with rigorous validation standards and a clear definition of the applicability domain, continues to enhance the predictive power and reliability of QSAR models. As drug discovery faces increasing challenges of complexity and cost, the systematic application of these QSAR principles provides researchers with a validated framework for accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental computational approach in modern drug discovery, mathematically linking a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity or properties [16]. These models operate on the principle that structural variations systematically influence biological activity, enabling researchers to predict the behavior of untested compounds based on their molecular descriptors [16]. The evolution of QSAR from classical statistical methods to artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced approaches has transformed it into an indispensable tool for addressing key challenges in pharmaceutical development: predicting bioactivity with increasing accuracy, informing strategic lead optimization, and significantly reducing experimental costs and timelines [24] [3].

The drug discovery process typically spans 10-15 years with substantial resource investments, where efficacy and toxicity issues remain primary reasons for failure [8]. QSAR modeling addresses these challenges by enabling virtual screening of large compound libraries, prioritizing candidates with desired biological activity, and minimizing reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental procedures [16] [8]. By integrating wet experiments, molecular dynamics simulations, and machine learning techniques, modern QSAR frameworks provide powerful predictive capabilities while offering mechanistic interpretations at atomic and molecular levels [25].

Fundamental Principles and Key Objectives of QSAR

Theoretical Foundations

QSAR modeling establishes mathematical relationships that quantitatively connect molecular structures of compounds with their biological activities through data analysis techniques [8]. The fundamental principle, tracing back to the 19th century with Crum-Brown and Fraser, states that the physicochemical properties and biological activities of molecules depend on their chemical structures [8]. This relationship is formally expressed as:

Biological Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃, ...)

where D₁, D₂, D₃, ... represent molecular descriptors that numerically encode structural, physicochemical, or electronic properties [8]. The function f can be linear (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression) or non-linear (e.g., Artificial Neural Networks), depending on the complexity of the relationship and available data [16] [8].

Core Objectives in Drug Discovery

QSAR modeling serves three primary objectives that align with critical needs in pharmaceutical research:

Predicting Bioactivity: QSAR models enable the accurate prediction of biological activities for novel compounds, including binding affinity, inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀), and efficacy against therapeutic targets before synthesis and experimental testing [16] [26]. For example, in a study targeting Sigma-2 receptor (S2R) ligands, QSAR models successfully identified FDA-approved drugs with sub-1 µM binding affinity, facilitating drug repurposing for cancer and Alzheimer's disease [26].

Informing Lead Optimization: During the hit-to-lead phase, QSAR models guide chemical modifications by identifying structural features and physicochemical properties that influence biological activity [16]. Recent work demonstrated how deep graph networks generated 26,000+ virtual analogs, resulting in sub-nanomolar inhibitors with over 4,500-fold potency improvement over initial hits [24].

Reducing Experimental Costs: By prioritizing the most promising compounds for synthesis and testing, QSAR significantly reduces resource burdens associated with high-throughput screening and animal testing [16] [27]. Computational approaches can decrease drug discovery costs and shorten development timelines by filtering large compound libraries into focused sets with higher success probability [27] [3].

QSAR Workflow and Methodologies

Systematic Modeling Approach

Developing robust QSAR models follows a structured workflow with distinct phases, each contributing to model reliability and predictive power. The comprehensive process integrates data preparation, model building, and validation components essential for creating scientifically valid predictive tools.

Molecular Descriptors and Representations

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that encode chemical, structural, or physicochemical properties of compounds, serving as the fundamental input variables for QSAR models [3]. These descriptors are systematically categorized based on dimensionality and complexity:

Table: Types of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Simple molecular properties | Molecular weight, atom count, bond count | Preliminary screening, drug-likeness filters |

| 2D Descriptors | Topological descriptors based on molecular connectivity | Balaban J, Chi indices, connectivity fingerprints | Standard QSAR, large database studies |

| 3D Descriptors | Spatial and steric properties | Molecular surface area, volume, polarizability | Conformation-dependent activity modeling |

| 4D Descriptors | Conformational ensembles | Interaction energy fields, conformation-dependent properties | Flexible molecule modeling, pharmacophore mapping |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | Electronic properties | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, electrostatic potential | Modeling electronic interactions with targets |

Descriptor calculation utilizes specialized software tools including PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit, Mordred, ChemAxon, and OpenBabel [16]. These tools can generate hundreds to thousands of descriptors for a given set of molecules, necessitating careful selection of the most relevant descriptors to build robust and interpretable QSAR models [16].

Model Building Algorithms

QSAR modeling employs diverse algorithmic approaches, ranging from classical statistical methods to advanced machine learning techniques:

Table: QSAR Modeling Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Methods | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Interpretable, fast, minimal parameters | Limited to linear relationships | Congeneric series, small datasets |

| Machine Learning | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors | Captures non-linear relationships, handles noisy data | Black-box nature, requires careful tuning | Diverse chemical spaces, complex SAR |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks, SMILES-based Transformers | Automatic feature learning, high predictive accuracy | High computational demand, large data requirements | Very large datasets, multi-task learning |

| Ensemble Methods | Decision Forest, Stacking, Boosting | Improved accuracy, reduced overfitting | Complex interpretation, computational cost | Critical predictions requiring high reliability |

Selection of appropriate algorithms depends on multiple factors, including dataset size, complexity of structure-activity relationships, desired interpretability, and available computational resources [16] [8]. Recent trends show increasing adoption of AI-integrated approaches, with studies demonstrating superior performance of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) over traditional Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) models in predicting NF-κB inhibitory activity [8].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Strategies

Robust Model Development Protocol

Developing statistically significant QSAR models requires meticulous attention to each step of the experimental process:

Step 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Compile chemical structures and associated biological activities from reliable sources (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) with comparable activity values obtained through standardized experimental protocols [8].

- Ensure structural diversity covering a broad chemical space relevant to the problem domain [28].

- Standardize chemical structures by removing salts, normalizing tautomers, and handling stereochemistry [16].

- Convert biological activities to a common unit (typically pIC₅₀ or pKi) and scale appropriately [16].

- Handle missing values through removal or imputation techniques (k-nearest neighbors, matrix factorization) [16].

Step 2: Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Calculate molecular descriptors using specialized software (Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit) [16] [3].

- Apply feature selection methods to identify the most relevant descriptors:

- Remove constant or highly correlated descriptors to reduce dimensionality and minimize overfitting [3].

Step 3: Data Splitting

- Divide datasets into training (~60-80%), validation (~10-20%), and external test sets (~10-20%) using rational methods (Kennard-Stone, random selection) [16] [8].

- Ensure all sets represent similar chemical space and activity distributions [28].

- Reserve external test sets exclusively for final model assessment, independent of model tuning and selection [16].

Step 4: Model Training and Optimization

- Train selected algorithms (MLR, PLS, ANN, SVM) using training sets [16] [8].

- Optimize hyperparameters through grid search, Bayesian optimization, or genetic algorithms [3].

- Employ k-fold cross-validation or leave-one-out cross-validation to prevent overfitting and estimate generalization ability [16].

Step 5: Model Validation and Applicability Domain

- Conduct internal validation using training set data (Q², R², RMSE) [16] [8].

- Perform external validation using test set data to assess predictive performance on unseen compounds [16] [28].

- Define applicability domain using methods like leverage approach to identify where models make reliable predictions [8] [28].

Case Study: NF-κB Inhibitor QSAR Modeling

A comprehensive study demonstrating this protocol developed QSAR models for 121 Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitors, a promising therapeutic target for immunoinflammatory diseases and cancer [8]. The study compared Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models, with the ANN [8.11.11.1] architecture showing superior reliability and predictive performance. The leverage method defined the applicability domain, enabling efficient screening of new NF-κB inhibitor series [8]. This case highlights how rigorous QSAR methodologies facilitate targeted drug discovery for specific therapeutic targets.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for QSAR

Successful QSAR modeling relies on specialized computational tools and resources that constitute the essential "research reagents" in this domain:

Table: Essential Computational Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Platforms | Key Functionality | Application in QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit, Mordred | Generate 1D-3D molecular descriptors | Data preparation, feature generation |

| Cheminformatics | KNIME, Orange, ChemAxon | Data preprocessing, workflow automation | Data curation, pipeline management |

| Machine Learning | scikit-learn, WEKA, TensorFlow | Model building, algorithm implementation | Model training, validation |

| Specialized QSAR | QSARINS, Build QSAR, MOE | Domain-specific model development | Targeted QSAR implementation |

| Validation & Analysis | Various statistical packages | Model validation, applicability domain | Quality assessment, reliability testing |

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

AI Integration and Advanced Methodologies

The integration of artificial intelligence with QSAR modeling represents the most significant advancement in the field, transforming traditional approaches through:

- Deep Learning Architectures: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and SMILES-based transformers enable automatic feature learning without manual descriptor engineering, capturing hierarchical molecular features [3].

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: Combining structural information with omics data, real-world evidence, and multi-parametric optimization pushes the frontier of personalized medicine [3].

- Explainable AI (XAI): Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) address the "black-box" nature of complex models, enhancing interpretability and regulatory acceptance [3].

- Generative Models: Reinforcement learning and generative adversarial networks facilitate de novo drug design, creating novel molecular structures with desired properties [24] [3].

Addressing Current Challenges

Despite substantial progress, QSAR modeling faces ongoing challenges that guide future research directions:

- Data Quality and Quantity: The development of accurate predictive models strongly depends on the quality, quantity, and reliability of input data [28]. Curating large, diverse, and well-annotated datasets remains a priority.

- Activity Cliffs: Structural similarities with large property differences (activity cliffs) present significant prediction challenges [28]. Advanced methods like the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI) help identify and address these anomalies.

- Regulatory Acceptance: Standardizing validation protocols and demonstrating mechanistic interpretability are crucial for regulatory adoption of QSAR predictions [29] [3].

- Domain Applicability: Defining and communicating the boundaries of model applicability ensures appropriate use and prevents extrapolation beyond validated chemical spaces [29] [28].

QSAR modeling has evolved from a specialized computational technique to a central pillar of modern drug discovery, directly addressing the core objectives of predicting bioactivity, informing lead optimization, and reducing experimental costs. The integration of artificial intelligence with traditional QSAR methodologies has unleashed unprecedented predictive capabilities while introducing new challenges in interpretability and validation. As the field advances, the convergence of wet lab experiments, molecular simulations, and machine learning continues to enhance model accuracy and mechanistic understanding [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering QSAR principles and applications provides a powerful strategic advantage in accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics while optimizing resource allocation. Through continued refinement of algorithms, expansion of chemical databases, and standardization of validation practices, QSAR modeling is poised to remain an indispensable component of pharmaceutical research in the decade ahead.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and chemical risk assessment. These are regression or classification models that relate a set of "predictor" variables (X) to the potency of a biological response variable (Y) [1]. The fundamental premise underlying all QSAR analysis is the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) principle, which states that similar molecules have similar activities [1] [30]. This principle has guided medicinal chemistry for decades, enabling researchers to chemically modify bioactive compounds by inserting new chemical groups and testing how these modifications affect biological activity [30].

Traditional QSAR modeling follows a systematic workflow: (1) selection of a dataset and extraction of structural/empirical descriptors, (2) variable selection, (3) model construction, and (4) validation evaluation [1]. The mathematical expression of a QSAR model generally takes the form: Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [1]. This approach has yielded significant successes in predicting various chemical properties and biological activities, from boiling points of organic compounds to drug-likeness parameters such as the critical partition coefficient logP [31].

However, the emergence of the SAR paradox has challenged this fundamental assumption, revealing that structurally similar molecules do not always exhibit similar biological properties [1] [30] [31]. This paradox represents a significant challenge in drug discovery, as it undermines the predictive reliability of traditional QSAR approaches and necessitates more sophisticated modeling techniques that can account for these unexpected disparities in compound behavior.

Understanding the SAR Paradox

Definition and Fundamental Challenge

The SAR paradox refers to the observed phenomenon that it is not the case that all similar molecules have similar activities [1] [30] [31]. This contradiction to the central principle of SAR represents a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and drug design. The underlying problem stems from how we define a "small difference" on a molecular level, since different types of biological activities—such as reaction ability, biotransformation capability, solubility, and target activity—may each depend on distinct structural variations [1] [30].

The complexity of modern drug action exacerbates this paradox. Advances in network pharmacology have revealed that drug mechanisms are far more complex than traditionally expected [32]. Not only can a single target interact with diverse drugs, but it is increasingly recognized that most drugs act on multiple targets rather than a single one [32]. Furthermore, small changes to chemical structures can lead to dramatic fluctuations in their binding affinities to protein targets [32], violating the traditional understanding that similar molecules would possess similar biological properties through binding to the same protein target.

Theoretical Basis and Implications

From a computer science perspective, the no-free-lunch theorem provides insight into the SAR paradox by demonstrating that no general algorithm can exist to consistently define a "small difference" that always yields the best hypothesis [30]. This mathematical reality forces researchers to focus on identifying strong trends rather than absolute rules when working with finite chemical datasets [1] [30].

The implications of the SAR paradox for drug discovery are profound. It highlights the limitations of relying exclusively on molecular descriptors and sophisticated computational approaches alone [32]. When the SAR paradox occurs, conventional QSAR models may demonstrate poor predictability when applied to independent external datasets [32]. This unpredictability manifests in several ways, most notably through the phenomenon of "activity cliffs"—where small structural changes result in large potency changes [32] [33]—and challenges in defining the proper applicability domain for QSAR models [32].

Table 1: Factors Contributing to the SAR Paradox in Drug Discovery

| Factor | Description | Impact on SAR |

|---|---|---|

| Target Complexity | Single drugs acting on multiple targets rather than a single target [32] | Reduces predictability of activity based on structure alone |

| Activity Cliffs | Small structural changes causing large potency fluctuations [32] | Creates discontinuities in structure-activity relationships |

| Over-fitted Models | Models that fit training data well but perform poorly on new data [1] | Generates false confidence in SAR hypotheses |

| Limited Applicability Domain | Model predictions being unreliable outside specific chemical spaces [32] | Restricts generalizability of SAR principles |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating the SAR Paradox

Integrated QSAR Modeling Approach

To address the limitations posed by the SAR paradox, researchers have developed innovative methodologies that integrate multiple data types. One advanced approach incorporates both structural information of compounds and their corresponding biological effects into QSAR modeling [32]. This method was successfully demonstrated in a study predicting non-genotoxic carcinogenicity of compounds, where conventional molecular descriptors were combined with gene expression profiles from microarray data [32].

The experimental workflow for this integrated approach involves:

- Data Collection and Pretreatment: A toxicological dataset is compiled, and molecular descriptors are calculated. The number of molecular descriptors is typically reduced through pretreatment processes (e.g., from 929 to 108 descriptors) [32].

- Feature Selection: The Recursive Feature Selection with Sampling (RFFS) method is applied to identify the most predictive features. In the referenced study, this process selected five molecular descriptors with frequencies higher than 0.1 in traditional QSAR models, along with one significant genetic probe (metallothionein) with a frequency of 0.72 [32].

- Model Construction: Separate QSAR and integrated models are constructed. The traditional QSAR model uses only molecular descriptors, while the integrated model incorporates both molecular descriptors and biological data [32].

- Validation: Both internal and external validation processes assess model performance using metrics including accuracy (Acc.), sensitivity (Sens.), specificity (Spec.), area under curve (AUC), and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) [32].

Advanced Computational Approaches

Several specialized computational methodologies have been developed to better capture the complex relationships between chemical structure and biological activity:

3D-QSAR techniques, such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), apply force field calculations requiring three-dimensional structures of small molecules with known activities [1] [31]. These methods examine steric fields (molecular shape) and electrostatic fields based on applied energy functions like the Lennard-Jones potential [1] [31]. The created data space is then typically reduced through feature extraction before applying machine learning methods [1].

Graph-based QSAR approaches use the molecular graph directly as input for models, though these generally yield inferior performance compared to descriptor-based QSAR models [1]. Similarly, string-based methods attempt to predict activity based purely on SMILES strings [1].

Matched Molecular Pair Analysis (MMPA) coupled with QSAR modeling helps identify activity cliffs, addressing the "black box" nature of non-linear machine learning models [1]. This methodology systematically identifies pairs of compounds differing only by a specific structural transformation, allowing researchers to quantify the effect of particular chemical changes on biological activity [1].

Case Study: Overcoming the SAR Paradox in Predictive Toxicology

Experimental Design and Implementation

A compelling demonstration of overcoming the SAR paradox comes from a study focused on predicting non-genotoxic carcinogenicity of compounds [32]. Researchers hypothesized that incorporating biological context through gene expression data could mitigate the limitations of structure-only approaches. The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

The dataset was divided into training and test sets, with 57 samples for model development and 21 samples for external validation [32]. Molecular descriptors were calculated using specialized software, generating an initial set of 929 descriptors that was subsequently reduced to 108 through pretreatment processes [32]. Concurrently, microarray data analysis identified 96 genetic probes as candidates for signature genes in the feature selection process [32].

The Recursive Feature Selection with Sampling (RFFS) algorithm identified the most predictive features. This process revealed five molecular descriptors with frequencies higher than 0.1 in traditional QSAR models, along with one highly significant genetic probe (JnJRn0195, encoding metallothionein) with a remarkable frequency of 0.72 [32]. The final models were constructed using these selected features, with performance evaluated through both internal cross-validation and external validation on the test set.

Quantitative Results and Performance Comparison

The integrated model demonstrated significantly enhanced performance compared to the traditional QSAR approach. During internal validation, the integrated model showed statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01) across all five evaluation metrics: Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, AUC, and MCC [32].

Most notably, in external validation on the test set, the prediction accuracy of the QSAR model increased dramatically from 0.57 to 0.67 with the incorporation of just one selected signature gene (metallothionein) [32]. This substantial improvement with minimal additional biological data highlights the power of integrated approaches for addressing the SAR paradox.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Integrated QSAR Models

| Evaluation Metric | Traditional QSAR Model | Integrated QSAR Model | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (Acc.) | 0.57 | 0.67 | +17.5% |

| Sensitivity (Sens.) | Not Reported | Significantly Higher* | Statistically Significant |

| Specificity (Spec.) | Not Reported | Significantly Higher* | Statistically Significant |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Not Reported | Significantly Higher* | Statistically Significant |