From Hit to Candidate: A Strategic Framework for Lead Optimization in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the lead optimization (LO) stage in drug discovery, a critical phase following hit identification.

From Hit to Candidate: A Strategic Framework for Lead Optimization in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the lead optimization (LO) stage in drug discovery, a critical phase following hit identification. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of transforming screening hits into viable drug candidates. The scope covers methodological best practices for optimizing potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties, troubleshooting common challenges in candidate selection, and a comparative evaluation of strategies for validating lead compounds. The synthesis of these core intents offers a strategic framework to enhance efficiency and success rates in preclinical development.

Understanding the Hit-to-Lead Pipeline: Foundations for a Successful Optimization Campaign

Lead Optimization (LO) is a pivotal and complex stage in the drug discovery pipeline, dedicated to transforming early "hit" compounds into promising therapeutic candidates suitable for preclinical and clinical development [1]. This iterative process aims to simultaneously improve a molecule's potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics (ADME - Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) while reducing its potential toxicity [1]. Historically reliant on resource-intensive empirical methods, the field has been revolutionized by computational approaches and, more recently, by artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML), which enable a more rational and efficient design of novel drug candidates [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the modern experimental, computational, and AI-driven tools that define the current landscape of lead optimization.

The Strategic Position of Lead Optimization in the Drug Discovery Workflow

Lead optimization occupies a critical position in the drug discovery pipeline, acting as the crucial bridge between initial hit identification and the final selection of a drug candidate for formal preclinical testing [1]. The process begins after screening campaigns identify "hit" compounds with confirmed activity against a therapeutic target. The core objective of LO is to systematically refine these hits through iterative cycles of design, synthesis, and testing, balancing multiple property enhancements to identify a single molecule with the optimal profile for development.

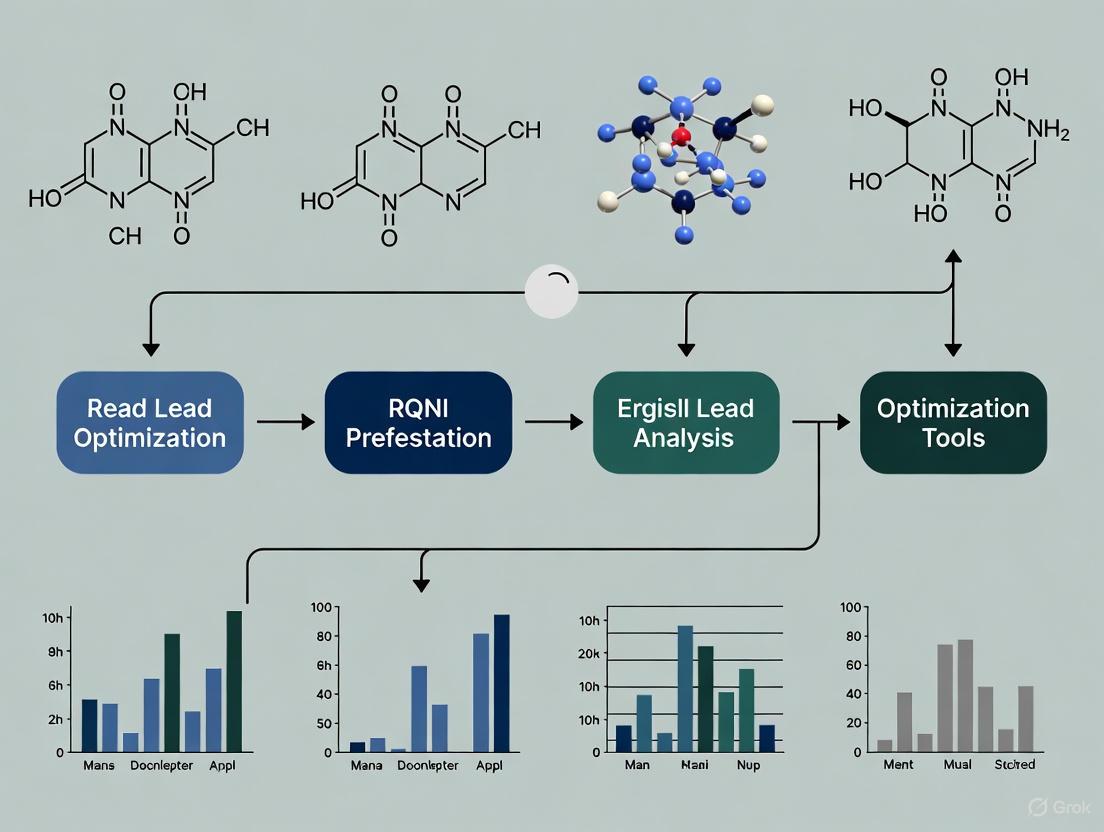

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the drug discovery pipeline and the central, iterative nature of the lead optimization phase.

Comparative Analysis of Lead Optimization Strategies and Technologies

Modern LO employs a synergistic combination of experimental, computational, and AI/ML approaches. The table below provides a high-level comparison of these core strategies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Lead Optimization Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental HTS & HCS [2] | Empirical testing of compound libraries using automated assays. | Provides direct biological data; HCS offers rich, multiparameter phenotypic data. | Resource-intensive; lower throughput compared to virtual methods. |

| Computational Methods (CADD) [3] [1] | Using computational models to predict molecular behavior and interactions. | Faster and cheaper than experimental methods; provides atomic-level insights. | Accuracy depends on model quality; can struggle with complex biology. |

| AI/ML-Driven Platforms [4] [1] | Using machine learning to predict properties and generate novel molecular structures. | High efficiency in exploring chemical space; continuous learning and improvement. | Requires large, high-quality datasets; "black box" interpretability challenges. |

| Specialized Modalities (e.g., TPD, ADCs) [3] [5] | Optimizing compounds based on novel mechanisms like targeted protein degradation or antibody-directed delivery. | Access to new target classes (e.g., "undruggable" proteins); enhanced therapeutic windows. | Complex molecular design; unique PK/PD and safety challenges. |

Experimental and Analytical Approaches

High-Content Screening (HCS) with 3D Models

Traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) often delivers single-end-point biochemical readouts. In contrast, High-Content Screening (HCS) leverages high-content imaging (HCI) and analytical tools (HCA) to provide high-throughput phenotypic analysis at subcellular resolution using multicolored, fluorescence-based images [2]. This multiparameter approach yields deeper insight into the specificity and sensitivity of novel lead compounds.

A key advancement is the application of HCS to 3D in vitro models like organoids and spheroids, which better recapitulate the in vivo cellular environment, tumor heterogeneity, and the tumor microenvironment compared to 2D monolayer cultures [2].

Table 2: Comparison of 3D Cell Models for HCS

| Model Type | Origin | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications in LO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organoids | Stem cell population from tissue [2]. | High clinical relevance, genetically stable, reproducible, scalable [2]. | Primary candidate for predictive drug response testing; evaluating tumor cell killing, invasion, differentiation [2]. |

| Spheroids | Cell aggregation [2]. | Easy to work with; less structural complexity than organoids; cannot be maintained long-term [2]. | Modeling cancer stem cells (CSCs); evaluating therapeutics targeting drug resistance [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: HCS Workflow with Organoids

- Pilot Screen & QC: A pilot screen with HCI is run to detect issues with 3D culture conditions before a full-scale screen [2].

- Cell Seeding & Compound Addition: Organoids are seeded, often in a scalable 384-well format, and test compounds are added [2].

- Incubation & Staining: Co-cultures are maintained for a set duration (1-7 days), followed by fixation and fluorescent staining (e.g., nuclei, actin cytoskeleton) [2].

- Image Acquisition: 3D image stacks are captured via "optical sectioning" using a high-content imager [2].

- Image Analysis: Advanced software (e.g., Ominer) performs image segmentation to identify individual organoid and cellular boundaries, extracting multivariate data (e.g., organoid size, shape, cell count) from the reconstituted images [2].

- Hit Selection: The rich dataset is analyzed and visualized to guide go/no-go decision-making on therapeutic candidates [2].

Efficiency Metrics for Novel Modalities

For innovative therapeutic modalities like Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), traditional potency metrics are insufficient. Cereblon E3 Ligase Modulators (CELMoDs), a class of molecular glue degraders, require optimization for both the potency and the maximum depth (efficacy) of protein degradation [6].

Degradation efficiency metrics have been developed to track these dual objectives during LO. The application of these metrics retrospectively tracked the optimization of a clinical molecular glue degrader series, culminating in the identification of Golcadomide (CC-99282), demonstrating their utility in identifying successful drug candidates [6].

Computational and AI-Driven Approaches

Virtual Screening (VS)

Virtual Screening is a cornerstone of computational LO, used to prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing. It is broadly divided into two categories [1]:

- Ligand-Based VS: Used when known active ligands are available. Key methods include Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, which relates molecular structure to biological activity, and pharmacophore modeling, which identifies essential molecular features for binding [1].

- Structure-Based VS: Used when the 3D structure of the target is known. It relies primarily on molecular docking, which predicts the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule within a protein's active site [1].

Table 3: Comparison of Virtual Screening Methodologies

| Method | Data Requirement | Key Function in LO | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | 3D structure of the target protein (experimental or homology model) [1]. | Predicts binding modes and ranks compounds by affinity; guides analog synthesis [1]. | Struggles with receptor flexibility and solvation effects; scoring functions can be imprecise [1]. |

| QSAR Modeling | Set of molecules with known activities [1]. | Predicts activity/toxicity of novel molecules; relates structural descriptors to biological effect [1]. | Limited to chemical space similar to the training set; quality depends on input data [1]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Set of known active ligands or a protein-ligand complex [1]. | Identifies key 3D chemical features for binding; used to screen libraries for novel scaffolds [1]. | Sensitive to the conformational model; may overlook valid hits that don't match the exact pharmacophore [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking and Dynamics Workflow

- Ligand Preparation: Ligands are drawn, protonated, and their geometry is minimized [1].

- Protein Preparation: The protein structure is prepared by adding hydrogens, calculating charges, and correcting side-chain orientations [1].

- System Minimization: The protein-ligand complex is minimized using a force field like Amber [1].

- Docking: Ligands are docked into the protein's active site using a multi-stage approach (e.g., High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) > Standard Precision (SP) > Extra Precision (XP)) in software like Glide to generate and rank binding poses [1].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation (for top poses): The complex is solvated in a water box, ions are added, and the system undergoes multi-step minimization and relaxation followed by a multi-nanosecond (e.g., 5000 ps) simulation under controlled temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble) to assess stability and conformational changes [1].

- Analysis: Results, including Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and hydrogen bonding interactions, are analyzed to validate binding stability [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between the key computational methods used in lead optimization.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI/ML is transforming LO by enabling more effective exploration of chemical space and more accurate prediction of molecular properties. Key applications include [1]:

- Predictive Modeling: Advanced ML models, including deep neural networks, are used to predict ADMET properties, binding affinities, and toxicity, often surpassing the accuracy of traditional QSAR methods [1].

- Generative Therapeutics Design (GTD): AI models can be trained to generate novel molecular structures that meet specific criteria (e.g., potency, synthesizability). The integration of 3D pharmacophore models into GTD workflows can significantly enhance the generation of relevant and effective inhibitor concepts [1].

The global AI-driven drug discovery platforms market, projected to grow from USD 2.9 billion in 2025 to USD 12.5 billion by 2035, underscores the rapid adoption and significant impact of these technologies, with a major application being in lead optimization [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and platforms essential for executing the lead optimization strategies discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Lead Optimization

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in LO |

|---|---|

| 3D Organoids (HUB protocol) [2] | Clinically relevant in vitro models for high-content phenotypic screening and predictive drug response testing. |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Organoids [2] | Advanced organoid models that retain the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the original patient tumor, enabling highly translatable drug studies. |

| Fluorescent Probes & Stains | Used in HCS for multiplexed imaging of nuclei, actin cytoskeleton, and specific target proteins to quantify phenotypic changes. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., Glide, Surflex-Dock) [1] | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of small molecules to a protein target, enabling structure-based virtual screening. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., Desmond) [1] | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand complexes. |

| AI/ML Platforms (e.g., for GTD or QMO) [1] | Utilizes machine learning to generate novel molecular entities (Generative Therapeutics Design) or optimize queries for molecular property prediction. |

| Cereblon-Based CELMoDs | A specific class of molecular glue degraders used as research tools and clinical candidates in Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) optimization [6]. |

| Ominer Software [2] | A powerful image analysis package used to extract multivariate data from 3D reconstituted images of organoids and spheroids in HCS assays. |

Lead optimization stands as a critical gateway in the drug discovery pipeline, where promising but imperfect hits are refined into viable drug candidates. The modern LO landscape is defined by the synergistic integration of multiple technologies: the physiological relevance of 3D HCS models, the predictive power of computational chemistry, and the transformative potential of AI/ML. While each approach has distinct strengths and limitations, their combined application allows research teams to navigate the complex optimization landscape more efficiently and effectively than ever before, ultimately accelerating the delivery of safer and more effective therapeutics to patients.

The primary goal of early drug discovery is to identify novel lead compounds that exhibit a optimal balance of desired potency, selectivity, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties for pre-clinical evaluation [7]. Achieving this balance is a complex, multi-parameter optimization problem; a compound with high potency against its target is of little therapeutic value if it is poorly absorbed, rapidly metabolized, or toxic. This comparative analysis focuses on the computational toolkits that enable researchers to navigate this challenging landscape. By objectively evaluating the features and capabilities of leading platforms, this guide aims to equip scientists with the data needed to select the most appropriate tools for streamlining the lead optimization process, ultimately increasing the probability of clinical success.

Comparative Analysis of Leading Optimization Platforms

This section provides a data-driven comparison of specialized software platforms designed to address the key objectives in lead optimization. The following table summarizes the core capabilities of these tools, highlighting their distinct approaches to predicting and optimizing critical compound properties.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Lead Optimization Software Platforms

| Software Platform | Primary Optimization Focus | Key Features | Methodology & Underlying Technology | Reported Application & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor (Simulations Plus) | ADMET Properties [7] | Predicts solubility, logP, permeability; ADMET Risk score; Advanced query language for property thresholds [7]. | QSAR (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) models; AI-powered predictive algorithms [7]. | Used to filter screening collections and prioritize synthetic candidates, reducing late-stage attrition [7]. |

| MedChem Studio (Simulations Plus) | Lead Discovery & Similarity Screening [7] | Class generation & clustering; Similarity screening based on molecular pairs; Combinatorial chemistry library enumeration [7]. | k-means clustering of MDL MACCS fingerprints; Molecular pair analysis and structural alignment [7]. | Enables creation of targeted libraries and identification of novel chemotypes through structural similarity [7]. |

| ADMET Modeler (Simulations Plus) | Building Custom Predictive Models [7] | Creates organization-specific QSAR models [7]. | Machine Learning-based model building on proprietary data sets [7]. | Allows teams to build predictive models as internal experimental data accumulates [7]. |

| GastroPlus PBPK Platform (Simulations Plus) | In Vivo Pharmacokinetics [7] | Predicts in vivo bioavailability and fraction absorbed; Simulates various dosing scenarios [7]. | Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and simulation [7]. | Used to predict human pharmacokinetics and prioritize compounds for synthesis based on simulated in vivo outcomes [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Tool Evaluation

To ensure a fair and objective comparison of different lead optimization tools, a standardized set of evaluation protocols is essential. The methodologies below outline key experiments for assessing a platform's predictive power and utility in a real-world research context.

Protocol for Predictive Performance Validation

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy of a platform's ADMET and potency predictions against a standardized set of experimental data. Materials:

- Software platform under evaluation (e.g., ADMET Predictor).

- Curated validation dataset comprising chemical structures with associated experimental values for key endpoints (e.g., solubility, logP, metabolic stability, IC50).

- Statistical analysis software (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn).

Methodology:

- Data Curation: A blinded dataset of 200-500 diverse compounds with high-quality, internally-generated experimental data is prepared.

- Prediction Generation: The chemical structures from the validation set are input into the software platform to generate in silico predictions for the target endpoints.

- Statistical Analysis: Predictions are statistically compared to experimental results using standard metrics:

- Correlation Coefficient (R²): Measures the strength of the linear relationship.

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Quantifies the average magnitude of prediction errors.

- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC): Assesses agreement between predicted and observed values.

Protocol for a Virtual Screening Workflow

Objective: To assess the tool's ability to prioritize compounds from a large virtual library for a specific target. Materials:

- Suite of computational tools (e.g., MedChem Studio for similarity screening, ADMET Predictor for property filtering).

- A known active compound ("seed") for the target of interest.

- A large, diverse virtual compound library (e.g., >100,000 compounds).

Methodology:

- Similarity Search: Use the "seed" compound to perform a similarity search within the virtual library using molecular pairing or fingerprint-based methods [7].

- ADMET Filtering: Apply calculated property filters (e.g., solubility >50 µM, logP <5, low predicted toxicity risk) to the resulting hit compounds [7].

- Diversity Selection: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) to select a structurally diverse subset of 50-100 compounds from the filtered list to ensure broad chemical space coverage [7].

- Output & Validation: The final prioritized list is generated. The success of the workflow is later determined by the experimental hit rate and quality of the compounds identified from this list.

Visualizing the Lead Optimization Workflow

The following diagrams, generated using the specified color palette and contrast rules, illustrate the logical flow of integrated computational processes in modern lead discovery.

Diagram: Integrated Lead Discovery Workflow

Integrated computational tools (green boxes) are embedded within the core experimental workflow to filter and prioritize compounds at multiple stages.

Diagram: Computational Screening & Prioritization Logic

This logic flow details the stepwise computational process for refining a large virtual library down to a small set of high-priority compounds predicted to have balanced properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

A successful lead optimization campaign relies on both computational tools and experimental reagents. The following table details key materials used in the associated biological and pharmacokinetic experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lead Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experimental Process |

|---|---|

| Screening Collection | A curated library of compounds (e.g., "general screening" or "targeted library") used in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns to identify initial "hit" compounds against a biological target [7]. |

| Targeted Library | A specialized subset of compounds designed or selected based on known modulators of the target, often created using computational similarity screening to improve hit rates [7]. |

| Primary Assay Reagents | The biochemical or cell-based components (e.g., purified target protein, cell lines, substrates) used in the initial HTS to measure a compound's potency and functional activity. |

| Secondary Assay Reagents | Reagents for follow-up experiments used to validate primary hits, assess selectivity against related targets, and identify mechanism-of-action or potential off-target effects. |

| QSAR Training Set | A curated set of chemical structures with corresponding experimentally-measured biological activity or ADMET property data. This dataset is used by tools like ADMET Modeler to build custom predictive machine learning models [7]. |

| PBPK Model Parameters | Physiological parameters (e.g., organ weights, blood flow rates, enzyme expression levels) and compound-specific data used within GastroPlus to simulate and predict human pharmacokinetics [7]. |

Discussion and Concluding Analysis

The comparative data and workflows presented demonstrate that modern computational toolkits are indispensable for achieving the critical balance between potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties. Platforms like the integrated suite from Simulations Plus provide a cohesive environment where predictive ADMET profiling, structural similarity analysis, and PBPK modeling work in concert [7]. This integration allows research teams to make data-driven decisions much earlier in the discovery process, shifting resource-intensive experimentation away from poor candidates and towards molecules with a higher probability of success.

The ultimate value of these tools is measured by their ability to de-risk the drug discovery pipeline. By using in silico predictions to filter virtual libraries, prioritize synthetic efforts, and forecast in vivo performance, organizations can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with lead optimization. The future of this field points toward even deeper integration of AI and machine learning, with continuous model refinement using internal data streams, further closing the loop between prediction and experimental validation to accelerate the delivery of new therapeutics.

In the rigorous process of drug discovery, lead optimization is a critical phase where identified compounds are refined into viable drug candidates. This process involves iterative rounds of synthesis and characterization to establish a clear picture of the relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its biological activity [8]. To navigate this complex landscape and prioritize compounds with the highest potential for success, researchers rely on key efficiency metrics. These quantitative tools help balance desirable potency against detrimental molecular properties, thereby estimating the overall "drug-likeness" of a candidate [9] [10].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three essential metrics for lead qualification: IC50 (Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration), which measures a compound's inherent potency; Ligand Efficiency (LE), which relates binding energy to molecular size; and Lipophilic Efficiency (LiPE or LLE), which links potency to lipophilicity [9] [11] [12]. By understanding and applying these metrics in concert, researchers and drug development professionals can make more informed decisions, steering lead optimization toward candidates with an optimal combination of biological activity and physicochemical properties.

Metric Definitions and Core Calculations

IC50/pIC50: The Potency Measure

IC50 is a direct measure of a substance's potency, defined as the concentration needed to inhibit a specific biological or biochemical function by 50% in vitro [12]. This biological function can involve an enzyme, cell, cell receptor, or microbe. To create a more convenient, linear scale for data analysis, IC50 is often converted to its negative logarithm, known as pIC50 [9] [12].

- Formula:

pIC50 = -log10(IC50)In this equation, the IC50 is expressed in molar concentration (mol/L, or M). Consequently, a lower IC50 value (indicating higher potency) results in a higher pIC50 value [12]. - Interpretation and Limitation: While IC50 is a crucial measure of functional strength, it is not a direct indicator of the binding affinity for a target. Its value can be highly dependent on experimental conditions, such as the concentration of substrate or agonist [12]. For a more absolute measure of binding affinity, the IC50 can be converted to the inhibition constant, Ki, using the Cheng-Prusoff equation [12].

Ligand Efficiency (LE): The "Bang per Buck" Metric

Ligand Efficiency was introduced as a "useful metric for lead selection" to normalize a compound's binding affinity by its molecular size [13] [11]. The underlying concept is to estimate the binding energy contributed per atom of the molecule, often summarized as getting 'bang for buck' [13].

- Formula:

LE = -ΔG / NWhere ΔG is the standard free energy of binding (approximately calculated as ΔG ≈ 1.4 * pIC50 at 298K, with pIC50 calculated from a molar concentration) and N is the number of non-hydrogen atoms (heavy atoms) [11]. - Alternative Form:

LE = 1.4 * pIC50 / N[11] - Interpretation and Limitation: LE helps identify lead compounds that achieve good potency without excessive molecular size, which is a key risk factor [13]. However, a significant critique of LE is its non-trivial dependency on the concentration unit used to express affinity, which challenges its physical meaningfulness for comparing individual compounds [13].

Lipophilic Efficiency (LiPE/LLE): Balancing Potency and Lipophilicity

Lipophilic Efficiency, also referred to as Ligand-Lipophilicity Efficiency (LLE), is a parameter that links a compound's potency with its lipophilicity [9] [10]. It is used to evaluate the quality of research compounds and estimate druglikeness by ensuring that gains in potency are not achieved at the cost of excessively high lipophilicity, which is associated with poor solubility, promiscuity, and off-target toxicity [9] [11].

- Formula:

LiPE (or LLE) = pIC50 - logP (or logD)Here, pIC50 represents the negative logarithm of the inhibitory potency, and LogP (or LogD at pH 7.4) is an estimate of the compound's overall lipophilicity [9] [10]. In practice, calculated values like cLogP are often used [9]. - Interpretation: Empirical evidence suggests that high-quality oral drug candidates typically have a LiPE value greater than 5 [9]. A high LiPE indicates that a compound achieves its potency through specific, high-quality interactions rather than non-specific hydrophobic binding [9] [10].

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

The table below provides a side-by-side comparison of these three critical lead qualification metrics, highlighting their formulas, primary functions, and strategic roles in the drug discovery process.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Key Lead Qualification Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Core Function | Strategic Role in Lead Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50/pIC50 [12] | pIC50 = -log10(IC50) |

Measures inherent biological potency. | Primary indicator of a compound's functional strength against the target. Serves as the foundational potency input for other efficiency metrics. |

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) [13] [11] | LE ≈ 1.4 * pIC50 / N(N = number of non-hydrogen atoms) |

Normalizes potency by molecular size. | Identifies compounds that deliver "more bang for the buck." Guides optimization toward smaller, less complex molecules without sacrificing potency. |

| Lipophilic Efficiency (LiPE/LLE) [9] [10] | LiPE = pIC50 - logP(logP or logD at pH 7.4) |

Balances potency against lipophilicity. | Penalizes gains in potency achieved merely by increasing lipophilicity. Aims to reduce attrition linked to poor solubility, metabolic clearance, and off-target toxicity. |

Strategic Interplay and Data Interpretation

Understanding how these metrics work together is crucial for effective lead qualification. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the fundamental properties of a compound and the derived metrics used for decision-making.

Diagram 1: The Interplay of Lead Qualification Metrics. This workflow shows how fundamental compound properties are synthesized into efficiency metrics to inform the lead qualification decision.

Interpreting the values of these metrics requires an understanding of their typical optimal ranges, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Benchmark Values and Interpretation Guidelines

| Metric | Desirable Range / Benchmark | Interpretation Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| pIC50 | Project-dependent; higher is better. | A pIC50 of 8 (IC50 = 10 nM) is generally considered highly potent. The required potency depends on the therapeutic area and target exposure [9]. |

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) | > 0.3 kcal/mol per heavy atom is often used as a threshold [11]. | Indicates whether a compound's binding affinity is achieved efficiently for its size. A low LE suggests the molecule is too large for its level of potency [13] [11]. |

| Lipophilic Efficiency (LiPE/LLE) | > 5 is considered desirable; > 6 indicates a high-quality candidate [9]. | A value of 6 corresponds to a highly potent (pIC50=8) compound with optimal lipophilicity (LogP=2). A low LLE signals high risk for poor solubility and promiscuity [9] [10]. |

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Standardized Protocols for Metric Determination

To ensure reliable and comparable data, consistent experimental protocols are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metric Determination

| Reagent / Assay | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Enzyme/Cell-Based Assay | Measures the primary functional IC50 value. The assay must be biologically relevant and robust. |

| Caco-2 Cell System [14] | An in vitro assay used to screen for permeability, which correlates with oral absorption. |

| Human Liver Microsomes [14] | Used to determine intrinsic clearance, estimating the metabolic stability and first-pass effect of a compound. |

| cLogP/LogD Calculation Software | Provides computational estimates of lipophilicity, which are frequently used in place of measured values for early-stage compounds [9]. |

IC50 Determination Protocol:

- Assay Setup: A dose-response curve is constructed by incubating the target (e.g., enzyme, cell) with a range of concentrations of the test antagonist/inhibitor.

- Response Measurement: The biological response (e.g., enzyme activity, cell growth) is measured for each concentration.

- Data Fitting: The data are fitted to a sigmoidal curve (e.g., using a four-parameter logistic model).

- IC50 Calculation: The concentration that yields a response halfway between the bottom and top plateaus of the curve is calculated as the IC50 [12]. This value is then converted to pIC50 for analysis.

Best Practice Note: The IC50 value is highly sensitive to assay conditions, including substrate concentration ([S]) and the concentration of agonist ([A]) in cellular assays. These should be carefully controlled and documented. For a more absolute measure of binding affinity, the Cheng-Prusoff equation can be used to convert IC50 to Ki [12].

Integrated Workflow for Lead Profiling

A typical profiling campaign for lead compounds involves a cascade of experiments to determine the necessary parameters for calculating these metrics. The following diagram outlines a standard integrated workflow.

Diagram 2: Integrated Lead Profiling Workflow. This protocol shows the sequence from compound synthesis through to multi-parameter optimization, integrating potency, lipophilicity, and size assessments.

The comparative analysis of IC50, Ligand Efficiency, and Lipophilic Efficiency reveals that no single metric provides a complete picture of a compound's potential. Instead, they form a complementary toolkit for lead qualification. IC50/pIC50 serves as the non-negotiable foundation of potency. Ligand Efficiency (LE) provides a crucial check against molecular obesity, ensuring that increases in potency are not merely a function of increased molecular size. Lipophilic Efficiency (LiPE/LLE) directly addresses one of the biggest risk factors in drug discovery—excessive lipophilicity—by rewarding compounds that achieve potency without high logP.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic imperative is clear: these metrics are most powerful when used in concert. Tracking LE and LLE throughout the lead optimization process provides a simple yet effective strategy to de-risk compounds early on. By aiming for candidates that simultaneously exhibit high potency (pIC50), efficient binding (LE > 0.3), and optimal lipophilicity (LLE > 5-6), teams can significantly increase the probability of advancing high-quality drug candidates with desirable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles [9] [13] [11]. This integrated, metrics-driven approach is fundamental to successful lead optimization in modern drug discovery.

In contemporary drug discovery, the journey from confirming a initial 'hit' compound to selecting a optimized compound 'series' for preclinical development represents a critical and resource-intensive phase. Establishing a robust project baseline during this period is paramount for success. This stage, encompassing hit-to-lead and subsequent lead optimization, demands rigorous comparative analysis to prioritize compounds with the highest probability of becoming viable drugs. The selection of a primary compound series is a foundational decision, setting the trajectory for all subsequent development work and significant financial investment [15].

The complexity of this process has been significantly augmented by sophisticated software platforms. These tools employ a range of computational methods—from quantum mechanics and free energy perturbation to generative AI—to predict and optimize key drug properties in silico before costly wet-lab experiments are conducted. This guide provides an objective comparison of leading software tools, framing their performance within the broader thesis that a multi-faceted, data-driven approach is essential for effective lead optimization research [15] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Lead Optimization Platforms

To make an informed choice, researchers must evaluate platforms based on their core capabilities, computational methodologies, and how they integrate into existing research workflows. The table below summarizes the performance and key features of several prominent tools.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Lead Optimization Software Platforms

| Software Platform | Primary Computational Method | Reported Efficiency Gain | Key Strengths | Licensing Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger | Quantum Mechanics, Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), Machine Learning (e.g., DeepAutoQSAR) | Simulation of billions of potential compounds weekly [15] | High-precision binding affinity prediction (GlideScore), scalable licensing via Live Design [15] | Modular pricing [15] |

| DeepMirror | Generative AI Foundational Models | Speeds up discovery process up to 6x; reduces ADMET liabilities [15] | User-friendly for medicinal chemists; predicts protein-drug binding; ISO 27001 certified [15] | Single package, no hidden fees [15] |

| Chemical Computing Group (MOE) | Molecular Modeling, Cheminformatics & Bioinformatics (e.g., QSAR, molecular docking) | Not explicitly quantified | All-in-one platform for structure-based design; interactive 3D visualization; modular workflows [15] | Flexible licensing [15] |

| Cresset (Flare V8) | Protein-Ligand Modeling, FEP, MM/GBSA | Supports more "real-life" drug discovery projects [15] | Handles ligands with different net charges; enhanced protein homology modeling [15] | Not Specified |

| Optibrium (StarDrop) | AI-Guided Optimization, QSAR, Rule Induction | Not explicitly quantified | Intuitive interface for small molecule design; integrates with Cerella AI platform and BioPharmics [15] | Modular pricing [15] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Understanding the underlying experimental protocols and methodologies is crucial for interpreting data and validating results from these platforms. Below are detailed methodologies for key computational experiments commonly cited in lead optimization research.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations

Objective: To achieve highly accurate predictions of the relative binding free energies of a series of analogous ligands to a protein target. This is a gold standard for computational prioritization of synthetic efforts [15].

Detailed Protocol:

- System Preparation: A representative protein-ligand complex structure is obtained from crystallography or homology modeling. The protein is prepared by assigning correct protonation states to residues (e.g., using PropKa), adding missing hydrogen atoms, and ensuring proper bond orders.

- Ligand Parameterization: The ligands are parameterized using a force field compatible with the FEP software (e.g., OPLS4 in Schrödinger). Partial charges are typically derived from quantum mechanical calculations.

- Alchemical Transformation Setup: A thermodynamic cycle is designed where one ligand is computationally "transformed" into another via a non-physical pathway. A series of intermediate states (λ windows) are defined, coupling the ligands to the environment with a scaling parameter λ that ranges from 0 (Ligand A) to 1 (Ligand B).

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: For each λ window, an MD simulation is performed in explicit solvent to sample the conformational space. This involves energy minimization, equilibration (NVT and NPT ensembles), and a production run (typically nanoseconds per window).

- Free Energy Analysis: The free energy difference (ΔΔG) between the ligands is calculated by integrating the energy derivatives across all λ windows using methods such as the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI).

- Validation: Results are often validated against a known set of ligands with experimentally determined binding affinities (IC50/Ki) to ensure predictive accuracy, with a correlation coefficient (R²) of >0.7 often considered a benchmark for a high-quality FEP model.

AI-Driven Molecular Property Prediction

Objective: To leverage generative AI and machine learning models to predict critical Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties and bioactivity directly from chemical structure [15] [16].

Detailed Protocol:

- Data Curation and Featurization: A large, high-quality dataset of compounds with associated experimental property data is assembled. Molecular structures are converted into numerical features (descriptors) or a machine-readable format (e.g., SMILES strings). The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets.

- Model Training: A machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Graph Neural Network, or a transformer-based foundational model as used in DeepMirror) is trained on the training set. The model learns the complex relationship between the molecular features and the target property [15].

- Hyperparameter Tuning & Validation: Model performance is evaluated on the validation set, and hyperparameters are tuned to optimize performance metrics (e.g., Mean Absolute Error for regression, AUC-ROC for classification). Techniques like cross-validation are employed to prevent overfitting.

- Model Evaluation: The final model's predictive power is assessed on the held-out test set. Performance is reported using standardized metrics, allowing for objective comparison against other models or traditional QSAR approaches.

- De Novo Molecular Design: In generative AI workflows, the trained model can be used to propose novel molecular structures optimized for multiple desirable properties simultaneously, exploring a broader chemical space [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational & Experimental Lead Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Lead Optimization |

|---|---|

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Technology for high-throughput screening of vast chemical libraries (billions of compounds) against a protein target, facilitating efficient hit discovery [3]. |

| Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) | Bifunctional small molecules that recruit a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to its degradation; enables targeting of "undruggable" proteins [3]. |

| Click Chemistry Reagents (e.g., Azides, Alkynes) | Enable rapid, modular, and bioorthogonal synthesis of diverse compound libraries for SAR exploration, or serve as linkers in PROTACs [3]. |

| Stable Cell Lines | Engineered cell lines (e.g., expressing a target receptor or a reporter gene) used for consistent, high-throughput cellular assays to evaluate compound efficacy and toxicity. |

| Human Liver Microsomes | In vitro system used to predict a compound's metabolic stability and identify potential metabolites during early ADME screening. |

Visualizing the Lead Optimization Workflow

The transition from hit confirmation to series selection follows a logical, iterative workflow that integrates computational and experimental data. The following diagram maps this critical pathway.

Diagram 1: Iterative Workflow from Hit Confirmation to Series Selection

This iterative cycle is powered by computational tools that accelerate each step. The "In Silico Profiling & Prioritization" phase heavily relies on the platforms compared in this guide to predict properties and select the most promising compounds for synthesis, thereby increasing the efficiency of the entire process [15].

Establishing a project baseline from hit confirmation to series selection is no longer reliant solely on empirical experimental data. The integration of sophisticated computational tools provides a powerful, predictive framework that de-risks this crucial phase. Platforms specializing in physics-based simulations (e.g., Schrödinger, Cresset) offer high-accuracy insights into binding, while AI-driven platforms (e.g., DeepMirror, Optibrium) enable rapid exploration of chemical space and ADMET properties [15].

The choice of tool is not mutually exclusive; a synergistic approach often yields the best results. The ultimate goal is to build a comprehensive data package for a lead series that demonstrates a compelling balance of potency, selectivity, and developability. By leveraging these technologies to create a robust, data-driven project baseline, research teams can make more informed decisions, allocate resources more effectively, and significantly increase the probability of clinical success.

Core Strategies and Experimental Methodologies for Lead Optimization

In the competitive landscape of drug discovery, lead optimization is a critical bottleneck. Two predominant methodologies—Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) and Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)—offer distinct yet complementary pathways for guiding this process. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, detailing their methodologies, performance, and practical applications to inform research strategies.

Core Methodological Comparison

At their core, SAR and SBDD differ in their fundamental requirements and the type of information they prioritize for lead optimization.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of SAR and SBDD

| Feature | Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | Bioactivity data & chemical structures of known active/inactive compounds [17] [18] [19] | Three-dimensional (3D) structure of the biological target (e.g., protein) [20] [21] [22] |

| Primary Approach | Ligand-based; infers target requirements indirectly [19] | Target-based; designs molecules for a specific binding site [20] [21] |

| Key Question | "How do changes in the ligand's structure affect its activity?" [18] | "How does the ligand interact with the 3D structure of the target?" [21] [22] |

| Dependency on Target Structure | Not required [19] | Essential (experimental or modeled) [22] [23] |

The following workflow illustrates the distinct and shared steps in applying SAR and SBDD in a lead optimization project:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis

The foundational process of SAR involves the systematic alteration of a lead compound's structure and the subsequent evaluation of how these changes affect biological activity [18].

Workflow for Probing Functional Group Interactions: A key application of SAR is to determine the role of specific functional groups, such as a hydroxyl group, in binding.

- Step 1: Hypothesis. A phenolic hydroxyl group in the lead compound is suspected to form a hydrogen bond with the target receptor [18].

- Step 2: Analog Synthesis. Synthesize analogs where the hydroxyl group is replaced with other functionalities [18].

- Replace -OH with -H (deoxy analog) or -CH3 (methyl ether) to remove hydrogen-bonding capability [18].

- Step 3: Biological Assay. Test the biological activity (e.g., IC50, Ki) of the original lead and its synthesized analogs in a consistent assay [18].

- Step 4: Data Interpretation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for SAR Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in SAR Analysis |

|---|---|

| Compound Analog Series | A collection of molecules with systematic, single-point modifications to a core lead structure to establish causality [18]. |

| In-vitro Bioassay Systems | Standardized pharmacological tests (e.g., enzyme inhibition, cell proliferation) to quantitatively measure compound activity [18]. |

| SAR Table | A structured data table that organizes compounds, their physical properties, and biological activities to visualize trends and relationships [24]. |

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) Protocol

SBDD relies on the knowledge of the target's 3D structure to directly visualize and computationally simulate the interaction with potential drugs [20] [22].

Workflow for Molecular Docking and Free Energy Calculation: This protocol is used to predict the binding mode and affinity of a designed compound before synthesis.

- Step 1: Target Preparation. Obtain the 3D structure of the protein target from experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) or build a high-quality homology model using tools like SWISS-MODEL or I-TASSER [22]. The structure is then prepared for simulation by adding hydrogen atoms and optimizing side-chain conformations.

- Step 2: Binding Site Identification. Define the binding site (active site, allosteric site) using cavity prediction tools like CASTp or Q-SiteFinder [22].

- Step 3: Molecular Docking. Dock the small molecule (ligand) into the defined binding site using software such as AutoDock Vina or Schrödinger Glide to generate an ensemble of possible binding poses [22].

- Step 4: Scoring and Pose Selection. The generated poses are ranked using a scoring function to estimate the binding affinity and select the most likely binding mode [22].

- Step 5: Binding Free Energy Validation. For higher accuracy, advanced methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations coupled with free energy perturbation (FEP) or MM-PBSA calculations are used to more rigorously compute the binding free energy and validate the stability of the docked complex [19].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents & Software for SBDD

| Research Reagent / Software | Function in SBDD |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A primary repository for experimental 3D structures of biological macromolecules, serving as the starting point for SBDD [22]. |

| Homology Modeling Software (e.g., SWISS-MODEL) | Tools used to generate a 3D structural model of a target when an experimental structure is unavailable [22]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Algorithms that predict the optimal binding orientation and conformation of a small molecule in a protein's binding site [22]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Software packages that simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess binding stability and dynamics [22] [19]. |

Performance and Output Comparison

The choice between SAR and SBDD has significant implications for project resources, timelines, and the nature of the output.

Table 4: Performance and Output Comparison of SAR and SBDD

| Aspect | Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Intensity | High chemical synthesis & assay burden [18] | High computational resource requirements [22] [19] |

| Key Output | A predictive, quantitative model linking chemical features to biological activity (e.g., QSAR, pharmacophore model) [17] [22] | A 3D structural model of the ligand-bound complex, revealing atomic-level interactions [20] [21] |

| Strength | Can be applied without target structure; provides direct experimental data on actual compounds [17] [19] | Provides mechanistic insight and can guide design to avoid steric clashes or improve complementarity [20] [23] |

| Limitation | Can be synthetically limited; may not reveal the structural basis for activity [18] | Accuracy depends on the quality of the target structure and the scoring functions [22] [23] |

| Ideal Application | Optimizing properties like solubility & metabolic stability when target structure is unknown [17] [18] | Scaffold hopping; optimizing binding affinity and selectivity [20] [23] |

The modern paradigm in lead optimization is not a choice between SAR and SBDD, but a strategic integration of both [20] [19]. SAR provides the crucial ground-truth of experimental activity data, while SBDD offers a structural rationale for the observed trends. The most effective drug discovery pipelines leverage both: using SBDD to generate intelligent design hypotheses and SAR to experimentally validate and refine those designs in an iterative cycle. Furthermore, both fields are being transformed by Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, which enhance the predictive power of QSAR models and the accuracy of molecular docking and dynamics simulations, promising even greater efficiency in the future [20] [22] [19].

The pursuit of high-quality lead compounds in drug discovery is increasingly reliant on efficient synthetic strategies for generating analogues. Among these, High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and Parallel Chemistry have emerged as powerful, complementary approaches that enable rapid exploration of chemical space. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, framing them within the broader context of lead optimization tools. HTE leverages automation and miniaturization to empirically test hundreds of reaction conditions or building blocks in parallel, drastically accelerating reaction optimization and scope exploration [25]. In contrast, parallel synthesis focuses on the simultaneous production of many discrete compounds, typically in a library format, to quickly establish Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR). For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these strategies hinges on the specific project goals, available infrastructure, and the stage of the drug discovery pipeline. This article objectively compares their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform strategic decision-making in medicinal chemistry.

Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Methodologies

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of HTE and Parallel Chemistry, providing a framework for their comparison.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of High-Throughput and Parallel Synthesis Approaches

| Feature | High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Parallel Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Reaction optimization and parameter screening (e.g., solvents, catalysts, ligands) [25] | Rapid generation of discrete compound libraries for SAR exploration [26] |

| Typical Scale | Microscale (e.g., 2.5 μmol for radiochemistry) [25] | Millimole to micromole scale |

| Key Output | Optimal reaction conditions and understanding of reaction scope [25] | A collection of purified, novel analogues |

| Throughput | Very High (e.g., 96-384 reactions per run) [25] | High (e.g., 24-96 compounds per run) |

| Automation Dependency | Critical for setup and analysis [25] | High for efficiency, but can be manual |

| Data Richness | Rich in reaction performance data under varied conditions [25] | Rich in biological activity data (SAR) |

| Typical Stage | Lead Optimization, Route Scouting | Hit-to-Lead, Lead Optimization |

| Infrastructure Cost | High (specialized equipment, analytics) | Moderate to High (automated synthesizers) |

A key application of HTE is in challenging chemical domains, such as radiochemistry. A 2024 study demonstrated an HTE workflow for copper-mediated radiofluorination using a 96-well block, reducing setup and analysis time while efficiently optimizing conditions for pharmaceutically relevant boronate ester substrates [25]. This exemplifies HTE's power in accelerating research where traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches are prohibitive due to time or resource constraints [25].

Parallel synthesis often draws from foundational strategies like fragment-based lead discovery (FBLD), where starting with low molecular mass fragments (Mr = 120–250) allows for the synthesis of potent, lead-like compounds with fewer steps compared to traditional approaches [26]. The optimization from these fragments into nanomolar leads can be achieved through the synthesis of significantly fewer compounds, making it a highly efficient parallel strategy [26].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Protocol: HTE for Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 HTE radiochemistry study, outlines a workflow for optimizing radiofluorination reactions in a 96-well format [25].

- Workflow Overview:

- Materials and Setup:

- Equipment: 96-well disposable glass microvials housed in an aluminum reaction block; multichannel pipettes; preheated heating block; Teflon sealing film; capping mat [25].

- Reagents: Stock solutions of Cu(OTf)₂, ligands, and additives; stock solution of aryl boronate ester substrates in DMF or DMSO; eluted [¹⁸F]fluoride [25].

- Procedure:

- Dispensing: Using multichannel pipettes, dispense reagents in the following order to the 96-well vials to ensure reproducibility [25]:

- Cu(OTf)₂ solution and any additives/ligands.

- Aryl boronate ester substrate solution.

- [¹⁸F]fluoride solution.

- Reaction Execution: Seal the vials with a Teflon film and capping mat. Use a custom transfer plate to simultaneously place all vials into the preheated aluminum reaction block at 110 °C. Heat for 30 minutes [25].

- Analysis: After cooling, analyze reactions in parallel. The study validated several rapid quantification techniques [25]:

- PET Scanner Imaging: Place the entire 96-well block in a PET scanner for direct quantification of radioactivity distribution.

- Gamma Counting: Use a gamma counter to measure radioactivity in each vial.

- Autoradiography: Expose a radio-sensitive film or phosphorimager plate to the reaction block.

- Dispensing: Using multichannel pipettes, dispense reagents in the following order to the 96-well vials to ensure reproducibility [25]:

Quantitative Comparison of HTE and Parallel Synthesis Output

The quantitative output of these methodologies differs fundamentally, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from Representative Studies

| Metric | HTE Radiochemistry Study [25] | Fragment-Based Lead Discovery (Typical) [26] |

|---|---|---|

| Reactions/Compounds per Run | 96 reactions | 25-100 compounds (from literature survey) |

| Reaction Scale | 2.5 μmol (substrate) | Varies (not specified) |

| Material Consumption | ~1 mCi [¹⁸F]fluoride per reaction | N/A |

| Typical Binding Affinity of Starting Point | N/A (reaction optimization) | mM – 30 μM (fragments) |

| Optimized Lead Affinity | N/A (reaction optimization) | Nanomolar range |

| Time per Run (Setup + Analysis) | ~20 min setup, 30 min reaction, rapid analysis [25] | Varies by project |

| Key Performance Indicator | Radiochemical Conversion (RCC) | Ligand Efficiency (LE) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of HTE and parallel chemistry relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput and Parallel Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cu(OTf)₂ | Copper source for Cu-mediated radiofluorination reactions [25]. | HTE for PET tracer development [25]. |

| (Hetero)aryl Boronate Esters | Versatile coupling partners for transition-metal catalyzed reactions, e.g., Suzuki coupling, radiofluorination [25]. | Core building blocks in both HTE substrate scoping and parallel library synthesis [26]. |

| Ligands (e.g., Phenanthrolines, Pyridine) | Coordinate metal catalysts to modulate reactivity and stability [25]. | HTE optimization screens to find optimal catalyst systems [25]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Plates | Enable parallel purification of reaction mixtures by capturing product or impurities [25]. | Workup in both HTE and parallel synthesis workflows [25]. |

| Fragment Libraries | Collections of low molecular weight compounds (Mr ~120-250) with high ligand efficiency [26]. | Starting points for parallel synthesis in fragment-based lead discovery [26]. |

Visualizing the Fragment-Based Lead Discovery Workflow

A major application of parallel synthesis is in FBLD. The following diagram outlines the key stages of this strategy, from initial screening to lead generation.

In modern drug discovery, the lead optimization phase demands precise characterization of how potential therapeutic compounds interact with their biological targets. Biophysical and in vitro profiling techniques provide the critical data on binding affinity, kinetics, and cellular efficacy required to transform initial lead compounds into viable drug candidates. Among the most powerful tools for this purpose are Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), and cellular assays, each offering complementary insights into molecular interactions [27] [28]. While SPR provides detailed kinetic information and high sensitivity, ITC delivers comprehensive thermodynamic profiling, and cellular assays place these interactions in their physiological context [29] [30]. Understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of these techniques enables researchers to design more efficient lead optimization strategies, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key biophysical techniques, presenting objective performance data and detailed experimental protocols to inform their application in pharmaceutical research and development. The integration of these methods provides a multifaceted view of compound-target interactions, from isolated molecular binding to functional effects in complex biological systems [31] [32].

Technical Comparison of Key Biophysical Techniques

Fundamental Principles and Measurable Parameters

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free optical technique that detects changes in the refractive index at a sensor surface to monitor biomolecular interactions in real-time [27] [29]. When molecules in solution (analytes) bind to immobilized interaction partners on the sensor chip, the increased mass shifts the resonance angle, allowing precise quantification of binding kinetics (association rate constant, kₒₙ, and dissociation rate constant, kₒff) and affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant, KD) [30]. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) measures the heat released or absorbed during molecular binding events [27] [33]. By sequentially injecting one binding partner into another while maintaining constant temperature, ITC directly determines binding affinity (KD), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamic parameters including enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) without requiring immobilization or labeling [29] [28]. Cellular Assays for efficacy assessment encompass diverse methodologies that measure compound effects in biologically relevant contexts, ranging from traditional viability assays like MTT to advanced label-free biosensing techniques that monitor real-time cellular responses [34].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principles of SPR and ITC, highlighting how each technique detects and quantifies biomolecular interactions:

Comparative Performance Analysis

The selection of appropriate biophysical techniques requires understanding their relative capabilities, limitations, and sample requirements. The following table provides a detailed comparison of key performance parameters across SPR, ITC, and other common interaction analysis methods:

| Parameter | SPR | ITC | MST | BLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetics (kₒₙ/kₒff) | Yes [29] [33] | No [27] [29] | No [27] [33] | Yes [27] [29] |

| Affinity Range | pM - mM [29] [33] | nM - μM [29] [33] | pM - mM [27] [29] | pM - mM [29] [33] |

| Thermodynamics | Yes [29] [33] | Yes (full) [29] [33] | Yes [29] | Limited [29] [33] |

| Sample Consumption | Low [27] [29] | High [27] [29] [33] | Very low [27] [29] | Low [27] [29] |

| Throughput | Moderately high [29] [33] | Low (0.25-2 h/assay) [27] | Medium [29] | High [29] |

| Label Requirement | Label-free [27] [29] | Label-free [27] [29] | Fluorescent label required [27] [29] | Label-free [27] |

| Immobilization Requirement | Yes [27] [29] | No [27] [29] | No [27] | Yes [27] [29] |

| Primary Applications | Kinetic analysis, affinity measurements, high-quality regulatory data [29] [33] | Thermodynamic profiling, binding mechanism [29] [28] | Affinity measurements in complex fluids [27] | Rapid screening, crude samples [27] |

SPR is particularly noted for providing the "highest quality data, with moderately high throughput, while consuming relatively small quantities of sample" and is recognized as "the gold standard technique for the study of biomolecular interactions" [29] [33]. It is also the only technique among those compared that meets regulatory requirements for characterization of biologics by authorities like the FDA and EMA [29] [33]. Conversely, ITC's principal advantage lies in its ability to "simultaneously determine all thermodynamic binding parameters in a single experiment" without requiring modification of binding partners [29] [33], though it demands significantly larger sample quantities and provides no kinetic information [27] [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Protocol

SPR experiments require meticulous preparation and execution to generate reliable kinetic data. The following protocol outlines key steps for immobilizing binding partners and characterizing interactions:

Sensor Chip Preparation: Select an appropriate sensor chip surface based on the properties of the ligand (the immobilized binding partner). Common options include carboxymethylated dextran (CM5) for amine coupling, nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) for His-tagged protein capture, or streptavidin surfaces for biotinylated ligands [29]. Condition the surface according to manufacturer specifications before immobilization.

Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the ligand in appropriate immobilization buffer (typically pH 4.0-5.5 for amine coupling). Activate the carboxymethylated surface with a mixture of N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). Inject the ligand solution until the desired immobilization level is reached (typically 50-500 response units for kinetic studies). Deactivate any remaining active esters with ethanolamine hydrochloride [29] [33].

Binding Kinetics Measurement: Prepare analyte (the mobile binding partner) in running buffer (typically HBS-EP: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) with appropriate DMSO concentration matching compound stocks. Inject analyte over ligand surface and reference flow cell using a series of concentrations (typically spanning 100-fold range above and below expected KD) with sufficient contact time for association. Monitor dissociation in running buffer. Regenerate surface if necessary between cycles using conditions that remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [35] [29].

Data Analysis: Subtract reference flow cell and blank injection responses. Fit resulting sensorgrams to appropriate binding models (typically 1:1 Langmuir binding) using global fitting algorithms to determine kₒₙ, kₒff, and KD (KD = kₒff/kₒₙ) [29] [30].

For PROTAC molecules inducing ternary complexes, special considerations apply. When characterizing MZ1 (a PROTAC inducing Brd4BD2-VHL complexes), researchers immobilized biotinylated VHL complex on a streptavidin chip, then sequentially injected MZ1 and Brd4BD2 to demonstrate cooperative binding [36]. The "hook effect" – where high PROTAC concentrations disrupt ternary complexes by forming binary complexes – must be considered in experimental design [36].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Protocol

ITC directly measures binding thermodynamics through precise monitoring of heat changes during molecular interactions:

Sample Preparation: Dialyze both binding partners (macromolecule and ligand) into identical buffer conditions (e.g., 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5) to minimize artifactual heat signals from buffer mismatches [36]. Centrifuge samples to remove particulate matter. Degas samples briefly to prevent bubble formation during titration.

Instrument Setup: Load the macromolecule solution (typically 10-100 μM) into the sample cell. Fill the injection syringe with ligand solution (typically 10-20 times more concentrated than macromolecule). Set experimental temperature (typically 25°C), reference power, stirring speed (typically 750 rpm), and injection parameters (number, volume, duration, and spacing of injections) [28].

Titration Experiment: Perform initial injection (typically 0.5 μL) followed by a series of larger injections (typically 2-10 μL) with adequate spacing between injections (180-300 seconds) to allow return to baseline. Include a control experiment injecting ligand into buffer alone to account for dilution heats [36].

Data Analysis: Integrate heat peaks from each injection relative to baseline. Subtract control titration data. Fit corrected isotherm to appropriate binding model (typically single set of identical sites) to determine KD, ΔH, ΔS, and stoichiometry (n) [28].

For PROTAC characterization, ITC can measure both binary interactions (e.g., MZ1 with VHL or Brd4BD2 individually) and ternary complex formation, though the latter requires more complex experimental design and data analysis [36].

Cell-Based Assay Protocol for Efficacy Assessment

Cell-based assays bridge the gap between purified system interactions and physiological efficacy:

Cell Culture and Seeding: Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., VERO E6 for antiviral studies [34]) in recommended media under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). Seed cells into assay plates at optimized density (e.g., 5×10⁴ cells/mL for SPR-based cell assays [34]) and allow adherence (typically 24 hours).

Compound Treatment: Prepare test compounds in vehicle (e.g., DMSO) with final concentration typically below 1% to minimize vehicle toxicity effects. Add compound dilutions to cells in replicates, including appropriate controls (vehicle-only, positive controls, untreated cells).

Viability Assessment (MTT Assay): After appropriate incubation period (e.g., 48-96 hours), add MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to cells. Incubate 2-4 hours to allow mitochondrial dehydrogenase conversion to purple formazan crystals. Dissolve crystals in appropriate solvent (e.g., DMSO or acidified isopropanol). Measure absorbance at 570 nm with reference wavelength (e.g., 630-690 nm) to quantify viability relative to controls [34].

SPR-Based Cell Assay (Alternative Method): Seed cells directly onto specialized SPR slides. For grating-based SPR, remove slides from medium at fixed intervals after seeding, rinse gently with deionized water, and measure SPR signal. Monitor signal changes induced by cell coverage, compound toxicity, and therapeutic effects [34]. This approach can detect morphological changes and cell proliferation in real-time without labels.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in integrating these techniques for comprehensive compound profiling:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of biophysical and cellular assays requires specific reagent systems optimized for each technology platform:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Sensor Chips | CM5 (carboxymethylated dextran), NTA (nitrilotriacetic acid), SA (streptavidin) [29] | Provide immobilization surfaces with different coupling chemistries for diverse ligand types |

| ITC Buffers | HEPES (20 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (150 mM), TCEP (1 mM) [36] | Maintain protein stability while minimizing heat of dilution artifacts during titrations |

| Viability Assay Reagents | MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) [34] | Measure mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity as indicator of cell health and compound toxicity |

| Cell Lines | VERO E6 (African green monkey kidney) [34] | Provide biologically relevant systems for antiviral and cytotoxicity testing |

| PROTAC System Components | Biotinylated VHL complex (VHL(53-213)/ElonginB/ElonginC) [36] | Enable study of ternary complex formation in targeted protein degradation |

SPR, ITC, and cellular assays each provide distinct yet complementary insights during lead optimization. SPR excels in detailed kinetic analysis with minimal sample consumption, ITC provides comprehensive thermodynamic profiling without molecular modifications, and cellular assays contextualize interactions within biologically relevant systems. The convergence of these techniques—particularly through innovations like cell-based SPR that measure interactions in native environments—represents the future of biomolecular interaction analysis [30]. Researchers can employ these technologies strategically based on their specific characterization needs: SPR for high-quality kinetic data suitable for regulatory submissions, ITC for understanding binding energetics and mechanism, and cellular assays for establishing functional efficacy. An integrated approach, leveraging the unique strengths of each methodology, provides the most robust path to optimizing lead compounds into development candidates.

Table 1: Platform Overview and Key Performance Indicators

| Platform/Tool | Primary Technology | Key ADMET Endpoints Covered | Reported Performance / Validation | Model Transparency & Customization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [37] | AI/ML & QSAR | 175+ properties, including LogD, solubility, CYP metabolism, P-gp, DILI [37] | LogD R²=0.79; HLM CLint R²=0.53 (Improved with local models) [38] | High; optional Modeler module for building local in-house models [38] |

| Receptor.AI ADMET Model [39] | Multi-task Deep Learning (Mol2Vec + descriptors) | 38+ human-specific endpoints, including key toxicity and PK parameters [39] | Competes with top performers in benchmarks; uses LLM-assisted consensus scoring [39] | Medium; flexible endpoint fine-tuning, but parts are "black-box" [39] |

| Federated Learning Models (e.g., Apheris) [40] | Federated Learning with GNNs | Cross-pharma ADMET endpoints (e.g., clearance, solubility) [40] | 40-60% reduction in prediction error; outperforms local baselines [40] | Varies; high on data privacy, model interpretability can be a challenge [40] |

| Open-Source Models (e.g., Chemprop, ADMETlab) [39] | Various ML (e.g., Neural Networks) | Varies by platform, often core physicochemical and toxicity endpoints [39] | Good baseline performance; can struggle with novel chemical space [39] | Low to Medium; often lack interpretability and adaptability [39] |

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties during the lead optimization phase is a critical determinant of clinical success. Historically, poor pharmacokinetics and toxicity were major causes of drug candidate failure, accounting for approximately 40% of attrition in clinical trials [41]. The implementation of early ADMET screening has successfully reduced failures for these reasons to around 11%, making lack of efficacy and human toxicity the primary remaining hurdles [41]. Early assessment allows researchers to identify and eliminate compounds with unfavorable profiles before significant resources are invested, thereby accelerating the discovery of safer, more effective therapeutics [42] [43].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of modern in silico tools for predicting three cornerstone properties of early ADMET: metabolic stability, permeability, and cytotoxicity. We objectively evaluate leading platforms by synthesizing published experimental validation data, detailing their underlying methodologies, and presenting a curated list of essential research reagents and datasets that underpin this field.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Data Comparison

Independent evaluations and vendor-reported data provide insights into the predictive performance of various platforms. The following tables summarize key quantitative comparisons for critical ADMET properties.

Table 2: Metabolic Stability and Permeability Prediction Performance

| Platform / Model | Experimental System / Endpoint | Dataset Size (Compounds) | Key Performance Metric(s) | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor (Global Model) [38] | Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) CL~int~ | 4,794+ | R² = 0.53 [38] | Evaluation on a large, proprietary dataset from Medivir. |

| ADMET Predictor (Local Model) [38] | Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) CL~int~ | (Medivir dataset) | R² = 0.72 [38] | Local model built with AP's Modeler module on in-house data. |

| ADMET Predictor [38] | Intestinal Permeability (S+Peff) | 4,794+ | Useful for categorization (High/Low) [38] | Guides synthesis and prioritizes in vitro experiments. |

| Federated Learning Models [40] | Human/Mouse Liver Microsomal Clearance, Solubility (KSOL), Permeability (MDR1-MDCKII) | Multi-pharma (Federated) | 40-60% reduction in prediction error [40] | Results from cross-pharma collaborative training (e.g., MELLODDY consortium). |

Table 3: Physicochemical Property and Toxicity Prediction Performance

| Platform / Model | Property / Endpoint | Key Performance Metric(s) | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [38] | Lipophilicity (LogD) | R² = 0.79 [38] | Strong correlation guides compound design. |

| ADMET Predictor [38] | Water Solubility | Model overprediction noted [38] | Performance may vary; local models can address this. |

| Receptor.AI [39] | Consensus Score across 38+ endpoints | Improved consistency and reliability [39] | LLM-based rescoring integrates signals across all endpoints. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vitro Assay Protocols for Experimental Validation

The predictive accuracy of in silico models is benchmarked against standardized wet-lab experiments. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays that provide the foundational data for model training and validation.

Metabolic Stability in Human Liver Microsomes (HLM)

- Objective: To measure the in vitro intrinsic clearance (CL~int~) of a compound, predicting its metabolic stability in vivo [38].

- Protocol: Incubate the test compound (typically 1 µM) with pooled human liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL protein) in a phosphate or Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing magnesium chloride. The reaction is initiated by adding NADPH (1 mM). Aliquots are taken at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45 minutes) and the reaction is stopped by transferring to an organic solvent like acetonitrile [38] [44]. The samples are centrifuged, and the supernatant is analyzed using LC-MS/MS to determine the parent compound's concentration remaining over time.

- Data Analysis: The natural log of the compound concentration is plotted versus time. The slope of the linear regression (k, the elimination rate constant) is used to calculate in vitro CL~int~ = k / microsomal protein concentration. This value is used for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) [44].