Ensuring Model Robustness in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Y-Randomization and Applicability Domain Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical practices of assessing model robustness using Y-randomization and Applicability Domain (AD) analysis.

Ensuring Model Robustness in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Y-Randomization and Applicability Domain Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical practices of assessing model robustness using Y-randomization and Applicability Domain (AD) analysis. As machine learning and QSAR models become integral to accelerating drug discovery, ensuring their reliability and predictive power is paramount. We explore the foundational principles of model validation as defined by the OECD guidelines, detailing the step-by-step methodologies for implementing Y-randomization tests to combat chance correlation and various techniques for defining a model's AD. The article further addresses common pitfalls in model development, offers strategies for optimizing AD methods for specific datasets, and presents a framework for the comparative validation of different robustness assurance techniques. By synthesizing these concepts, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build more trustworthy, robust, and predictive models, thereby de-risking the drug development pipeline.

The Pillars of Trustworthy Models: Understanding OECD Principles, Robustness, and Generalizability

The OECD (Q)SAR Validation Principles: A Foundation for Regulatory Acceptance

For researchers and drug development professionals using Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) validation principles provide a critical foundation for ensuring scientific rigor and regulatory acceptance. Established to keep QSAR applications on a solid scientific foundation, these principles represent an international consensus on the necessary elements for validating (Q)SAR technology for regulatory applications [1].

The OECD formally articulated five principles for QSAR model validation. These principles ensure that models are scientifically valid, transparent, and reliable for use in chemical hazard and risk assessment [2]. Adherence to these principles is particularly important for reducing and replacing animal testing, as regulatory acceptance of alternative methods requires demonstrated scientific rigor [3].

The Five Validation Principles: Detailed Analysis and Methodologies

Principle 1: A Defined Endpoint

The first principle mandates that the endpoint being modeled must be unambiguously defined. This requires clear specification of the biological activity, toxicity, or physicochemical property the model predicts.

Experimental Protocol: When citing or developing a QSAR model, researchers should:

- Clearly define the experimental system and conditions used to generate the training data

- Specify the measurement units and any normalization procedures applied

- Document the biological relevance of the endpoint to the regulatory context

- Report any data curation steps, including outlier removal and data transformation techniques

Principle 2: An Unambiguous Algorithm

This principle requires that the algorithm used to generate the model must be transparent and fully described. This ensures the model can be independently reproduced and verified.

Methodological Details: The model description should include:

- Mathematical form of the model (linear, non-linear, etc.)

- Software implementation and version

- All equations, descriptors, and parameters with their statistical significance

- For complex models like ANNs or SVMs, the network architecture or kernel functions must be specified [2]

Principle 3: A Defined Domain of Applicability

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions. This is crucial for identifying when a prediction for a new chemical structure is an extrapolation beyond the validated scope.

Domain Establishment Protocol:

- Descriptor Range Method: A compound with descriptor values within the range of the training set compounds is considered inside the AD [4]

- Leverage Analysis: Calculate leverage value (hᵢ) for each compound: hᵢ = xᵢᵀ(XᵀX)⁻¹xᵢ, where xᵢ is the descriptor vector for compound i, and X is the descriptor matrix of the training set [4]

- Critical Threshold: A leverage value greater than the critical h* value (h* = 3p/n, where p is the number of model variables and n is the number of training compounds) indicates the compound is outside the optimal prediction space [4]

- Standardization Approaches: Used to identify X-outliers in the training data [4]

Principle 4: Appropriate Measures of Goodness-of-Fit, Robustness, and Predictivity

This principle addresses the statistical validation of the model, encompassing three key aspects: how well the model fits the training data (goodness-of-fit), how sensitive it is to small changes in the training set (robustness), and how well it predicts new data (predictivity).

Validation Protocol:

- Goodness-of-Fit: Assess using R² (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (root mean square error) on training data [2]

- Robustness Evaluation:

- Predictivity Assessment:

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for QSAR Models

| Validation Type | Common Metrics | Interpretation Guidelines | Methodological Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-Fit | R², RMSE | R² > 0.6-0.7 generally acceptable; Beware overestimation on small samples [2] | Misleadingly overestimates models on small samples [2] |

| Robustness | Q²LOO, Q²LMO | Values should be close to R²; Difference indicates overfitting | LOO and LMO can be rescaled to each other [2] |

| Predictivity | Q²F1, Q²F2, Q²F3, CCC | Q² > 0.5 generally acceptable | External validation provides independent information from internal validation [2] |

Principle 5: A Mechanistic Interpretation, If Possible

While not always mandatory, providing a mechanistic interpretation of the model strengthens its scientific validity and regulatory acceptance. This principle encourages linking structural descriptors to biological activity through plausible biochemical mechanisms.

Assessment Approach:

- Identify known toxicophores or structural alerts associated with the endpoint

- Relate descriptor importance to known biological pathways

- Consider metabolic activation or transformation products when relevant [5]

The OECD (Q)SAR Assessment Framework: Recent Advances

Building on the original principles, the OECD has developed the (Q)SAR Assessment Framework (QAF) to provide more specific guidance for regulatory assessment. The QAF establishes elements for evaluating both models and individual predictions, including those based on multiple models [3] [6].

The QAF provides clear requirements for model developers and users, enabling regulators to evaluate (Q)SARs consistently and transparently. This framework is designed to increase regulatory uptake of computational approaches by establishing confidence in their predictions [3]. The principles may extend to other New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to facilitate broader regulatory acceptance [3].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Recent studies applying OECD principles demonstrate both capabilities and limitations of validated QSAR approaches:

Table 2: Performance of OECD QSAR Toolbox Profilers in Genotoxicity Assessment [5] [7]

| Profiler Type | Endpoint | Accuracy Range | Impact of Metabolism Simulation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNT-related Profilers | In vivo Micronucleus (MNT) | 41% - 78% | +4% to +16% accuracy | High rate of false positives; Low positive predictivity [5] |

| AMES-related Profilers | AMES Mutagenicity | 62% - 88% | +4% to +6% accuracy | "No alert" correlates well with negative experimental outcomes [5] |

| General Observation | Absence of profiler alerts reliably predicts negative outcomes [5] |

The data indicates that while negative predictions are generally reliable, positive predictions require careful evaluation due to varying false positive rates. The study recommends that "genotoxicity assessment using the Toolbox profilers should include a critical evaluation of any triggered alerts" and that "profilers alone are not recommended to be used directly for prediction purpose" [5].

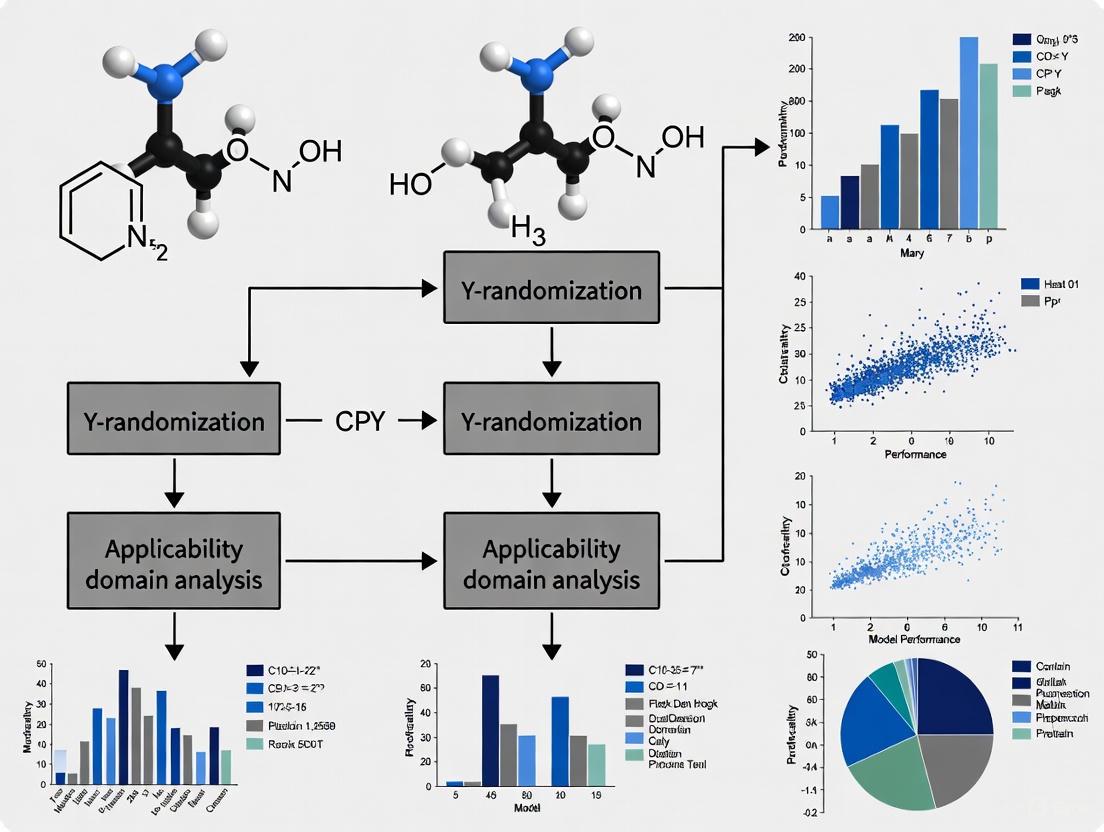

Visualization of QSAR Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for validating QSAR models according to OECD principles, highlighting the relationship between different validation components:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function in QSAR Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Provides profilers and databases for chemical hazard assessment | Regulatory assessment of genotoxicity, skin sensitization [5] |

| Y-Randomization Tools | Tests for chance correlation in models | Robustness assessment (Principle 4) [2] |

| Applicability Domain Methods | Defines model boundaries using leverage and descriptor ranges | Domain of applicability analysis (Principle 3) [4] |

| Cross-Validation Scripts | Evaluates model robustness to training set variations | Internal validation (Principle 4) [2] |

| External Test Sets | Assesses model predictivity on unseen data | External validation (Principle 4) [2] |

Uncertainty Analysis in QSAR Predictions

A critical aspect of QSAR validation involves understanding and quantifying sources of uncertainty in predictions. Recent research has developed methods to analyze both implicit and explicit uncertainties in QSAR studies [8].

The most significant uncertainty sources identified include:

- Mechanistic plausibility: Uncertainty about the biological mechanism

- Model relevance: Appropriateness of the model for the specific chemical space

- Model performance: Statistical uncertainty in predictions [8]

Uncertainty is predominantly expressed implicitly in QSAR literature, with implicit uncertainty being more frequent in 13 of 20 identified uncertainty sources [8]. This analysis supports the fit-for-purpose evaluation of QSAR models required by regulatory frameworks.

The OECD validation principles provide a systematic framework for developing and assessing QSAR models that are scientifically valid and regulatory acceptable. The recent development of the (Q)SAR Assessment Framework offers additional guidance for consistent regulatory evaluation [3] [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing these principles requires careful attention to endpoint definition, algorithmic transparency, applicability domain specification, comprehensive statistical validation, and mechanistic interpretation. The integration of y-randomization tests and rigorous applicability domain analysis addresses the core thesis requirement of assessing model robustness, ensuring that QSAR predictions used in regulatory decision-making and drug development are both reliable and appropriately qualified.

Defining Robustness and Generalizability in Machine Learning for Drug Discovery

In modern drug discovery, machine learning (ML) models promise to accelerate the identification and optimization of candidate compounds. However, their practical utility hinges on two core properties: robustness—the model's consistency and reliability under varying conditions—and generalizability—its ability to make accurate predictions for new, unseen data, such as novel chemical scaffolds or different experimental settings [9]. The high failure rates in drug development, with approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition linked to poor Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties, underscore that a model's performance on a static benchmark is insufficient; it must perform reliably in real-world, dynamic discovery settings [10].

This guide objectively compares methodologies and performance metrics for assessing these vital characteristics, framing the evaluation within the rigorous context of Y-randomization and applicability domain (AD) analysis. These frameworks move beyond simple accuracy metrics, providing a structured approach to quantify a model's true predictive power and limitations before it influences costly experimental decisions [11] [12].

Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance and Robustness Strategies

Different modeling approaches and validation strategies lead to significant variations in performance and generalizability. The tables below summarize comparative data and key methodological choices that influence model robustness.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Models in Drug Discovery Applications

| Model/Technique | Application Context | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANDO Platform [13] | Drug-Indication Association | % of known drugs in top 10 candidates | 7.4% (CTD), 12.1% (TTD) | Benchmarking against CTD/TTD databases |

| Optimized Ensembled Model (OEKRF) [14] | Drug Toxicity Prediction | Accuracy | 77% → 89% → 93%* | Three scenarios with increasing rigor |

| Federated Learning (Cross-Pharma) [10] | ADMET Prediction | Reduction in prediction error | 40-60% | Multi-task learning on diverse datasets |

| XGBoost [11] | Caco-2 Permeability | Predictive Performance | Superior to comparable models | Transferability to industry dataset |

| Structure-Based DDI Models [9] | Drug-Drug Interaction | Generalization to unseen drugs | Tends to generalize poorly | Three-level scenario testing |

*Performance improved from 77% (original features) to 89% (with feature selection/resampling and percentage split) and 93% (with feature selection/resampling and 10-fold cross-validation) [14].

Table 2: Impact of Validation and Data Strategies on Generalizability

| Strategy | Core Principle | Effect on Robustness/Generalizability | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Split [15] [10] | Splitting data by molecular scaffold to test on new chemotypes | Directly tests generalizability to novel chemical structures | Considered a more challenging and realistic benchmark than random splits [15]. |

| Federated Learning [10] | Training models across distributed datasets without sharing data | Significantly expands model applicability domain | Systematic performance improvements; models show increased robustness on unseen scaffolds [10]. |

| Multi-Task Learning [10] | Jointly training related tasks (e.g., multiple ADMET endpoints) | Improves data efficiency and model generalization | Largest gains for pharmacokinetic and safety endpoints due to overlapping signals [10]. |

| 10-Fold Cross-Validation [14] | Robust resampling technique for performance estimation | Reduces overfitting and provides more reliable performance estimates | Key to achieving highest accuracy (93%) in toxicity prediction models [14]. |

| Temporal Splitting [13] | Splitting data based on approval dates to simulate real-world use | Tests model performance on future, truly unknown data | Used alongside k-fold CV and leave-one-out protocols [13]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Assessment

Y-Randomization Testing

Purpose: To verify that a model's predictive power derives from genuine structure-activity relationships and not from chance correlations within the dataset [11]. Methodology: The experimental activity or toxicity values (Y-vector) are randomly shuffled while the molecular structures and descriptors remain unchanged. A new model is then trained on this randomized data. Interpretation: A robust model should show significantly worse performance on the randomized dataset than on the original one. If the performance on the shuffled data is similar, it indicates the original model likely learned random noise and is not valid. This test is a cornerstone for establishing model credibility [11].

Applicability Domain (AD) Analysis

Purpose: To define the chemical space for which the model's predictions can be considered reliable, thereby quantifying its generalizability [11] [12]. Methodology: The AD is often characterized using:

- Leverage-based Methods: Calculating the Mahalanobis distance or similar metrics to determine if a new compound is within the descriptor space of the training set.

- PCA-based Methods: Projecting new compounds into the principal component space of the training data and assessing their proximity to training compounds.

- Descriptor Range: Checking if the values of key molecular descriptors for a new compound fall within the ranges observed in the training set. Interpretation: Predictions for compounds falling inside the AD are considered reliable; those outside the AD should be treated with caution, as the model is extrapolating. This is crucial for reliable decision-making in lead optimization [11].

Robust Data Splitting Strategies

Purpose: To realistically simulate a model's performance on future, unseen chemical matter. Methodology:

- Random Splitting: The dataset is randomly divided into training and test sets. This is a weak method for assessing generalizability as similar compounds can end up in both sets.

- Scaffold Splitting: Compounds are split based on their molecular scaffolds (core structures). This tests the model's ability to predict activity for truly novel chemotypes, providing a much stricter assessment of generalizability [15].

- UMAP Splitting: A more advanced technique where a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection is used to create a chemically meaningful split that is more challenging than traditional methods [15].

Diagram 1: A workflow for comprehensive model assessment, integrating rigorous data splitting, Y-randomization, and applicability domain analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust ML Model Development in Drug Discovery

| Resource / 'Reagent' | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay Guidance Manual (AGM) [16] | Guidelines/Best Practices | Provides standards for robust assay design and data analysis. | Ensures biological data used for training is reliable and reproducible. |

| Caco-2 Permeability Dataset [11] | Curated Public Dataset | Models intestinal permeability for oral drugs. | A standard, well-characterized benchmark for evaluating model generalizability. |

| Federated ADMET Network [10] | Collaborative Framework | Enables multi-organization model training on diverse data. | Inherently increases chemical space coverage, improving model robustness. |

| ChemProp [15] | Software (Graph Neural Network) | Predicts molecular properties directly from molecular graphs. | A state-of-the-art architecture for benchmarking new models. |

| kMoL Library [10] | Software (Machine Learning) | Open-source library supporting federated learning for drug discovery. | Facilitates reproducible and standardized model development. |

| RDKit [11] | Software (Cheminformatics) | Generates molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Provides standardized molecular representations, a foundation for robust modeling. |

| ADME@NCATS Web Portal [16] | Public Data Resource | Provides open ADME models and datasets for validation. | Offers a critical benchmark for external validation of internal models. |

Visualizing the Role of the Applicability Domain

The Applicability Domain acts as a boundary for model trustworthiness, a concept critical for understanding generalizability.

Diagram 2: The concept of the Applicability Domain (AD). Predictions for Test Compound A (blue), which is near training compounds (green), are reliable. Test Compound B (red) is outside the AD, and its prediction is an untrustworthy extrapolation.

Defining and assessing robustness and generalizability is not a single experiment but a multi-faceted process. As the data shows, the choice of model, the quality and diversity of the training data, and—critically—the rigor of the validation protocol collectively determine a model's real-world value.

The integration of Y-randomization and applicability domain analysis provides a scientifically sound framework for this assessment, moving the field beyond potentially misleading aggregate performance metrics. Future progress will likely be driven by collaborative approaches, such as federated learning, which inherently expand the chemical space a model can learn from, and the continued development of more challenging benchmarking standards that force models to generalize rather than memorize [15] [10]. For researchers and development professionals, adopting these rigorous practices is essential for building machine learning tools that truly de-risk and accelerate the journey from a digital prediction to a safe and effective medicine.

The Critical Role of Y-Randomization in Detecting Chance Correlation

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the risk of chance correlation represents a fundamental threat to model validity and subsequent application in drug discovery. This phenomenon occurs when models appear statistically significant despite using randomly generated or irrelevant descriptors, creating an illusion of predictive power that fails upon external validation or practical application. The problem intensifies with modern computational capabilities that enable researchers to screen hundreds or even thousands of molecular descriptors, increasing the probability that random correlations will emerge by sheer chance [17]. As noted in one analysis, "if we have sufficiently many structure descriptor variables to select from we can make a model fit data very closely even with few terms, provided that they are selected according to their apparent contribution to the fit. And this even if the variables we choose from are completely random and have nothing whatsoever to do with the current problem!" [17].

Within this context, Y-randomization (also called y-scrambling or response randomization) has emerged as a critical validation procedure to detect and quantify chance correlations. This method systematically tests whether a model's apparent performance stems from genuine underlying structure-activity relationships or merely from random artifacts in the data. By deliberately destroying the relationship between descriptors and activities while preserving the descriptor matrix, Y-randomization creates a statistical baseline against which to compare actual model performance [17]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of Y-randomization methodologies, experimental protocols, and integration with complementary validation techniques, offering researchers a framework for robust QSAR model assessment.

Understanding Y-Randomization: Principles and Purpose

Conceptual Foundation and Mechanism

Y-randomization functions on a straightforward but powerful principle: if a QSAR model captures genuine structure-activity relationships rather than random correlations, then randomizing the response variable (biological activity) should significantly degrade model performance. The technical procedure involves repeatedly permuting the activity values (y-vector) while keeping the descriptor matrix (X-matrix) unchanged, then rebuilding the model using the identical statistical methodology applied to the original data [17]. This process creates what are known as "random pseudomodels" that estimate how well the descriptors can fit random data through chance alone.

The validation logic follows that if the original model demonstrates substantially better performance metrics (e.g., R², Q²) than the majority of random pseudomodels, one can conclude with statistical confidence that the original model captures real relationships rather than chance correlations. As one study emphasizes, "If the original QSAR model is statistically significant, its score should be significantly better than those from permuted data" [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for models developed through descriptor selection, where the risk of overfitting and chance correlation is heightened.

The Critical Importance in Modern QSAR Practice

The value of Y-randomization has increased substantially with the proliferation of high-dimensional descriptor spaces and automated variable selection algorithms. Contemporary QSAR workflows often involve screening hundreds to thousands of molecular descriptors, creating ample opportunity for random correlations to emerge. Research indicates that with sufficient variables to select from, researchers can produce models that appear to fit data closely "even with few terms, provided that they are selected according to their apparent contribution to the fit" even when using completely random descriptors [17].

This vulnerability to selection bias makes Y-randomization an essential component of model validation, particularly in light of the growing regulatory acceptance of QSAR models in safety assessment and drug discovery contexts. The technique features prominently in the scientific literature as "probably the most powerful validation procedure" for establishing model credibility [17]. Its proper application helps prevent the propagation of spurious models that could misdirect synthetic efforts or lead to inaccurate safety assessments.

Methodological Variants: A Comparative Analysis

Standard Y-Randomization and Its Limitations

The standard Y-randomization approach involves permuting the activity values and recalculating model statistics without repeating the descriptor selection process. While this method provides a basic check for chance correlation, it can yield overoptimistic results because it fails to account for the selection bias introduced when descriptors are chosen specifically to fit the activity data [17]. This approach essentially tests whether the specific descriptors chosen in the final model correlate with random activities, but doesn't evaluate whether the selection process itself capitalized on chance correlations in the larger descriptor pool.

Enhanced Approaches: Integrating Descriptor Selection

More rigorous variants of Y-randomization incorporate the descriptor selection process directly into the randomization test. As emphasized in the literature, the phrase "and then the full data analysis is carried out" is crucial—this includes repeating descriptor selection for each Y-randomized run using the same criteria applied to the original model [17]. This approach more accurately simulates how chance correlations can influence the entire modeling process, not just the final regression with selected descriptors.

Research indicates that for a new MLR QSAR model to be statistically significant, "its fit should be better than the average fit of best random pseudomodels obtained by selecting descriptors from random pseudodescriptors and applying the same descriptor selection method" [17]. This represents a more stringent criterion that directly addresses the selection bias problem inherent in high-dimensional descriptor spaces.

Table 1: Comparison of Y-Randomization Methodological Variants

| Method Variant | Procedure | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Y-Randomization | Permute y-values, recalculate model statistics with fixed descriptors | Simple to implement, computationally efficient | Does not account for descriptor selection bias, can be overoptimistic |

| Y-Randomization with Descriptor Selection | Permute y-values, repeat full descriptor selection and modeling process | Accounts for selection bias, more rigorous assessment | Computationally intensive, requires automation of descriptor selection |

| Modified Y-Randomization with Pseudodescriptors | Replace original descriptors with random pseudodescriptors, apply selection process | Directly tests selection bias, establishes statistical significance | May be overly conservative, complex implementation |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Y-Randomization Protocol

Implementing Y-randomization correctly requires careful attention to methodological details. The following protocol ensures comprehensive assessment:

- Initial Model Development: Develop the QSAR model using standard procedures including descriptor selection, parameter optimization, and internal validation.

- Y-Permutation: Randomly permute the activity values (y-vector) while maintaining the descriptor matrix (X-matrix) intact.

- Full Model Reconstruction: Repeat the entire model development process, including descriptor selection, on the permuted data using identical methodologies and criteria as the original model.

- Iteration: Perform steps 2-3 repeatedly (typically 100-1000 iterations) to build a distribution of random model performance metrics.

- Statistical Comparison: Compare the original model's performance metrics (R², Q², etc.) against the distribution of metrics from random models.

- Significance Assessment: Calculate the p-value as the proportion of random models that perform as well as or better than the original model. A common threshold for statistical significance is p < 0.05 [17].

This workflow ensures that the validation process accurately reflects the entire modeling procedure rather than just the final regression step.

Quantitative Interpretation Guidelines

Proper interpretation of Y-randomization results requires both quantitative and qualitative assessment. The following criteria support robust evaluation:

- Performance Threshold: The original model's R² and Q² values should be "much lower" than those from the scrambled data to indicate a valid model [17].

- Statistical Significance: For rigorous validation, the original model's fit should exceed the average fit of the best random pseudomodels obtained through the complete randomization procedure including descriptor selection [17].

- Visual Assessment: Histograms of randomization results should show clear separation between the original model's performance and the distribution of random models.

Research emphasizes that a single or few y-permutation runs may occasionally produce high fits by chance if the permuted y-values happen to be close to the original arrangement. Therefore, sufficient iterations (typically 50-100 minimum) are necessary to establish a reliable distribution of chance correlations [17].

Figure 1: Standard Y-Randomization Experimental Workflow

Complementary Validation Techniques

Integration with Applicability Domain Analysis

Y-randomization finds enhanced utility when combined with applicability domain (AD) analysis, creating a comprehensive validation framework. AD analysis defines the chemical space where models can provide reliable predictions based on the training set compounds' distribution in descriptor space [18]. While Y-randomization assesses model robustness against chance correlations, AD analysis establishes prediction boundaries and identifies when models are applied beyond their validated scope.

The integration of these approaches follows a logical sequence: Y-randomization first establishes that the model captures genuine structure-activity relationships rather than chance correlations, while AD analysis then defines the appropriate chemical space where these relationships hold predictive power. This combined approach is particularly valuable for identifying reliable predictions during virtual screening, where compounds may fall outside the model's trained chemical space [18].

Cross-Validation and External Validation

Y-randomization complements rather than replaces other essential validation techniques:

- Cross-Validation: Provides estimates of model predictive ability within the training data through systematic data partitioning. Double cross-validation (2CV) is particularly valuable as it provides external figures of merit and helps mitigate overfitting [19].

- External Validation: Represents the "gold standard" for assessing predictive performance using completely independent data not used in model development [19].

- Permutation Tests: Non-parametric permutation tests based on random rearrangements of the y-vector help determine the statistical significance of model metrics and are useful in combination with 2CV [19].

Table 2: Comprehensive QSAR Validation Strategy Matrix

| Validation Technique | Primary Function | Implementation | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-Randomization | Detects chance correlations | 50-1000 iterations with full model reconstruction | Original model performance should significantly exceed random model distribution (p < 0.05) |

| Applicability Domain Analysis | Defines reliable prediction boundaries | Distance-based, range-based, or leverage approaches | Predictions for compounds outside AD are considered unreliable extrapolations |

| Cross-Validation | Estimates internal predictive performance | Leave-one-out, k-fold, or double cross-validation | Q² > 0.5 generally acceptable; Q² > 0.9 excellent |

| External Validation | Assesses performance on independent data | Hold-out test set or completely external dataset | R²ₑₓₜ > 0.6 generally acceptable; R²ₑₓₜ > 0.8 excellent |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Implementing robust Y-randomization requires both computational tools and methodological components. The following table details essential "research reagents" for effective chance correlation detection:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Y-Randomization Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software Platforms | MATLAB with PLS Toolbox, R Statistical Environment, Python with scikit-learn | Provides permutation testing capabilities and model rebuilding infrastructure | Ensure capability for full workflow automation including descriptor selection |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | RDKit, Dragon, MOE | Generates comprehensive molecular descriptor sets for QSAR modeling | Standardize descriptor calculation protocols to ensure consistency |

| Modeling Algorithms | PLS-DA, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks | Enables model reconstruction with permuted y-values | Maintain constant algorithm parameters across all randomization iterations |

| Validation Metrics | R², Q², RMSE, MAE, NMC (Number of Misclassified Samples) | Quantifies model performance for original and randomized models | Use multiple metrics to assess different aspects of model performance |

| Visualization Tools | Histograms, scatter plots, applicability domain visualizations | Compares original vs. random model performance distributions | Implement consistent color coding (original vs. random models) |

Y-randomization remains an indispensable tool for detecting chance correlations in QSAR modeling, particularly in an era of high-dimensional descriptor spaces and automated variable selection. The most effective implementation incorporates the complete modeling workflow—including descriptor selection—within each randomization iteration to accurately capture selection bias. When combined with applicability domain analysis, cross-validation, and external validation, Y-randomization forms part of a comprehensive validation framework that establishes both the statistical significance and practical utility of QSAR models.

The continuing evolution of QSAR methodologies, including dynamic models that incorporate temporal and dose-response dimensions [12], underscores the ongoing importance of robust validation practices. By adhering to the protocols and comparative frameworks presented in this guide, researchers can more effectively discriminate between genuinely predictive models and statistical artifacts, thereby accelerating reliable drug discovery and safety assessment.

Conceptualizing the Applicability Domain (AD) for Reliable Predictions

In the realm of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and machine learning for drug development, the Applicability Domain (AD) defines the boundaries within which a model's predictions are considered reliable [20]. It represents the chemical, structural, and biological space covered by the training data used to build the model [20]. The fundamental premise is that models are primarily valid for interpolation within the training data space rather than extrapolation beyond it [21] [20]. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) principles for QSAR model validation, defining the AD is a mandatory requirement for models intended for regulatory purposes [22] [20]. This underscores its critical role in ensuring predictions used for chemical safety assessment or drug discovery decisions are trustworthy.

The core challenge AD addresses is the degradation of model performance when predicting compounds structurally dissimilar to those in the training set [21]. As the distance between a query molecule and the training set increases, prediction errors tend to grow significantly [21]. Consequently, mapping the AD allows researchers to identify and flag predictions that may be unreliable, thereby improving decision-making in exploratory research and development.

Key Methodologies for Defining Applicability Domains

Various algorithms have been developed to characterize the interpolation space of a QSAR model, each with distinct mechanisms and theoretical foundations [23] [20]. These methods can be broadly categorized, and their comparative analysis is essential for selecting an appropriate approach for a given modeling task.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Applicability Domain Methodologies

| Method Category | Key Examples | Underlying Mechanism | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range-Based & Geometric | Bounding Box, Convex Hull [24] [20] | Defines boundaries based on the min/max values of descriptors or their geometric enclosure. | Simple to implement and interpret [20]. | May include large, empty regions within the hull with no training data, overestimating the safe domain [25]. |

| Distance-Based | Euclidean, Mahalanobis, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) [24] [20] | Measures the distance of a new compound from the training set compounds or their centroids in descriptor space. | Intuitively aligns with the similarity principle [21]. | Performance depends on the choice of distance metric and the value of k; may not account for local data density variations [25]. |

| Density-Based | Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), Local Outlier Factor (LOF) [24] [25] | Estimates the probability density distribution of the training data to identify sparse and dense regions. | Naturally accounts for data sparsity and can handle arbitrarily complex geometries of ID regions [25]. | Computationally more intensive than simpler methods; requires bandwidth selection for KDE [25]. |

| Classification-Based | One-Class Support Vector Machine (OCSVM) [24] | Treats AD as a one-class classification problem to define a boundary around the training data. | Can model complex, non-convex boundaries in the feature space. | The fraction of outliers (ν) is a hyperparameter that cannot be easily optimized [24]. |

| Leverage-Based | Hat Matrix Calculation [20] | Uses leverage statistics from regression models to identify influential compounds and define the domain. | Integrated into regression frameworks, provides a statistical measure of influence. | Primarily suited for linear regression models. |

| Consensus & Reliability-Based | Reliability-Density Neighbourhood (RDN) [26] | Combines local data density with local model reliability (bias and precision). | Maps local reliability across chemical space, addressing both data density and model trustworthiness [26]. | More complex to implement; requires feature selection for optimal performance [26]. |

Advanced and Integrated Approaches

Beyond the standard categories, recent research has introduced more sophisticated frameworks. The Reliability-Density Neighbourhood (RDN) approach represents a significant advancement by combining the k-NN principle with measures of local model reliability [26]. It characterizes each training instance not just by the density of its neighborhood but also by the individual bias and precision of predictions in that locality, creating a more nuanced map of reliable chemical space [26].

Another general approach utilizes Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to assess the distance between data in feature space, providing a dissimilarity score [25]. Studies have shown that chemical groups considered unrelated based on chemical knowledge exhibit significant dissimilarities with this measure, and high dissimilarity is associated with poor model performance and unreliable uncertainty estimates [25].

For classification models, research indicates that class probability estimates consistently perform best at differentiating between reliable and unreliable predictions [27]. These built-in confidence measures of classifiers often outperform novelty detection methods that rely solely on the explanatory variables [27].

Experimental Protocols for AD Assessment and Optimization

Implementing a robust AD requires more than selecting a method; it involves a systematic process for evaluation and optimization tailored to the specific dataset and model.

Workflow for Machine Learning and AD Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for model building and AD integration, synthesizing common elements from the literature [24] [25] [26].

Protocol for Evaluating and Optimizing the AD Model

A critical protocol proposed in recent literature involves a quantitative method for selecting the optimal AD method and its hyperparameters for a given dataset and mathematical model [24]. The steps are as follows:

- Perform Double Cross-Validation (DCV): Conduct DCV on all samples to obtain a predicted y value for each sample. This provides a robust estimate of model performance without data leakage [24].

- Calculate AD Indices: For each candidate AD method and hyperparameter (e.g., k in k-NN, ν in OCSVM), calculate the AD index (a measure of reliability or distance) for every sample [24].

- Sort and Calculate Metrics: Sort all samples in descending order of their AD index value. Then, iteratively add samples one by one from most reliable (lowest distance) to least reliable (highest distance). For each step

i, calculate: - Compute the Area Under the Curve (AUCR): Plot RMSE against coverage and calculate the Area Under the Coverage-RMSE Curve (AUCR). A lower AUCR value indicates a better AD method, as it means the model maintains lower error rates across a larger portion of the data [24].

- Select Optimal AD Model: Choose the AD method and hyperparameter combination that yields the lowest AUCR value [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AD Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function in AD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints) [21] | Data Representation | Convert chemical structures into numerical vectors, forming the basis for distance and similarity calculations in the feature space. |

| Tanimoto Distance [21] | Distance Metric | A standard measure of molecular similarity based on fingerprint overlap; commonly used to define distance-to-training-set. |

Python package dcekit [24] |

Software Library | Provides code for the proposed AD evaluation and optimization method, including coverage-RMSE analysis and AUCR calculation. |

| R Package for RDN [26] | Software Library | Implements the Reliability-Density Neighbourhood algorithm, allowing for local reliability mapping. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [25] | Statistical Tool | Estimates the probability density of the training data in feature space, used as a dissimilarity score for new queries. |

| Y-Randomization Data | Validation Reagent | Used to validate the model robustness by testing the model with randomized response variables, ensuring the AD is not arbitrary. |

Decision Framework for AD in Model Assessment

Integrating AD analysis with Y-randomization tests forms a comprehensive framework for assessing model robustness. Y-randomization establishes that the model has learned a real structure-activity relationship and not chance correlations, while AD analysis defines the boundaries where this relationship holds.

The following diagram outlines the decision process for classifying predictions and assessing model trustworthiness based on this integrated approach.

Defining the Applicability Domain is a critical step in the development of reliable QSAR and machine learning models for drug development. While no single universally accepted algorithm exists, methods based on data density, local reliability, and class probability have shown superior performance in benchmarking studies [24] [25] [27]. The choice of AD method should be guided by the nature of the data, the model type, and the regulatory or research requirements. Furthermore, the emerging paradigm of optimizing the AD method and its hyperparameters for each specific dataset and model, using protocols like the AUCR-based evaluation, represents a significant leap toward more rigorous and trustworthy predictive modeling in medicinal chemistry and toxicology [24]. By systematically integrating Y-randomization for model validation and a carefully optimized AD for defining reliable chemical space, researchers can provide clear guidance on the trustworthiness of their predictions, thereby de-risking the drug discovery process.

The Interplay between Model Robustness and AI Trustworthiness

In modern drug discovery, the trustworthiness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) models is inextricably linked to their robustness—the ability to maintain predictive performance when faced with data that differs from the original training set [11]. As AI systems become deeply integrated into high-stakes pharmaceutical research and development, ensuring their reliability is paramount. The framework of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) emphasizes that for any AI tool to be valuable, it must be "fit-for-purpose," meaning its capabilities must be well-aligned with specific scientific questions and contexts of use [28]. This article examines the critical interplay between robustness and trustworthiness, focusing on two pivotal methodological approaches for their assessment: Y-randomization and applicability domain analysis. These protocols provide experimental means to quantify model reliability, thereby enabling researchers to calibrate their trust in AI-driven predictions for critical tasks such as ADMET property evaluation and small molecule design [11] [29] [30].

Theoretical Foundations: Robustness and Trustworthiness

Defining AI Trustworthiness in Drug Discovery

Trustworthiness in AI is a multi-faceted concept. In the context of drug discovery, it extends beyond simple accuracy to encompass reliability, ethical adherence, and predictive consistency [31] [32]. Scholars have identified key components including toxicity, bias, adversarial robustness, out-of-distribution robustness, privacy, machine ethics, and fairness [32]. A trustworthy AI system for drug development must generate predictions that are not only accurate on training data but also robust when applied to novel chemical structures or different experimental conditions [11].

The Critical Role of Model Robustness

Model robustness serves as the foundational pillar for AI trustworthiness. A robust model resists performance degradation when confronted with:

- Noise and variations in input data.

- Compounds falling outside its chemical training space.

- Adversarial attacks designed to manipulate outputs [32].

Without demonstrated robustness, AI predictions carry significant risks, potentially leading to misguided experimental designs, wasted resources, and failed clinical trials [28]. The techniques of Y-randomization and applicability domain analysis provide measurable, quantitative assessments of this vital property [11].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Robustness

Y-Randomization Testing

Purpose: The Y-randomization test, also known as label scrambling, is designed to validate that a model has learned genuine structure-activity relationships rather than merely memorizing or fitting to noise in the dataset [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Model Training with True Labels: A model is trained using the original dataset with correct activity values (e.g., Caco-2 permeability, IC50 values).

- Label Randomization: The process is repeated multiple times (e.g., 50-100 iterations), but each time the target activity values (the Y-vector) are randomly shuffled among the compounds, thereby breaking any real relationship between the chemical structures and their activities.

- Performance Comparison: The predictive performance (e.g., R², RMSE) of the model trained on true data is compared against the distribution of performance metrics from the models trained on scrambled data.

Interpretation: A robust and meaningful model will demonstrate significantly superior performance on the original data compared to any model built on the randomized data. If models from scrambled data achieve similar performance, it indicates the original model likely learned spurious correlations and is not trustworthy [11].

Applicability Domain (AD) Analysis

Purpose: Applicability Domain analysis defines the chemical space within which a model's predictions can be considered reliable. It assesses whether a new compound is sufficiently similar to the ones used in the model's training set [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Domain Characterization: The chemical space of the training set is characterized using molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit 2D descriptors) or fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints).

- Similarity Measurement: For a new query compound, its similarity or distance to the training set is calculated. Common methods include:

- Leverage-based Approaches: Calculating the leverage of a compound based on descriptor values to identify outliers.

- Distance-based Approaches: Using metrics like Euclidean distance or Mahalanobis distance to the centroid of the training set.

- Similarity-based Approaches: Using Tanimoto similarity to the nearest neighbor in the training set.

- Domain Definition: A threshold is set (e.g., a maximum leverage value, a minimum similarity score). Compounds falling outside this threshold are considered outside the model's Applicability Domain, and their predictions are flagged as less reliable.

Interpretation: By clearly delineating its reliable prediction boundaries, a model demonstrates self-awareness. Predictions for compounds within the AD are considered trustworthy, while those outside the AD require caution and experimental verification [11].

Comparative Analysis of AI Models in Drug Discovery

The following tables summarize experimental data from recent studies evaluating different AI/ML models, with a focus on assessments of their robustness and trustworthiness.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Models for Caco-2 Permeability Prediction (Dataset: 5,654 compounds) [11]

| Model | Average Test Set R² | Average Test Set RMSE | Performance in Y-Randomization | AD Analysis Implemented? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.81 | 0.31 | Significantly outperformed scrambled models | Yes |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.79 | 0.33 | Significantly outperformed scrambled models | Yes |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.75 | 0.37 | Significantly outperformed scrambled models | Yes |

| DeepMPNN (Graph) | 0.78 | 0.34 | Data Not Provided | Yes |

Table 2: Performance of QSAR Models for Acylshikonin Derivative Antitumor Activity [29]

| Model Type | R² | RMSE | Key Robustness Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Regression (PCR) | 0.912 | 0.119 | Electronic and Hydrophobic |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | 0.89 | 0.13 | Electronic and Hydrophobic |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | 0.85 | 0.15 | Electronic and Hydrophobic |

Table 3: Context-Aware Hybrid Model (CA-HACO-LF) for Drug-Target Interaction [33]

| Performance Metric | CA-HACO-LF Model Score |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.6% |

| AUC-ROC | >0.98 |

| F1-Score | >0.98 |

| Cohen's Kappa | >0.98 |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and validating a robust AI model in drug discovery, incorporating the key experimental protocols discussed.

AI Model Robustness Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Robust AI Modeling in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Open-source cheminformatics for molecular standardization, fingerprint generation (e.g., Morgan), and descriptor calculation (RDKit 2D) [11]. |

| XGBoost | ML Algorithm | A gradient boosting framework that often provides superior predictive performance and is frequently a top performer in comparative studies [11]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Assay | In Vitro Assay | The "gold standard" experimental model for evaluating intestinal permeability, used to generate ground-truth data for training and validating AI models [11]. |

| ChemProp | Software Library | A deep learning package specifically for message-passing neural networks (MPNNs) that uses molecular graphs as input for property prediction [11]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) Method | Computational Protocol | A set of techniques (e.g., leverage, distance-based) to define the chemical space where a model's predictions are reliable, crucial for trustworthiness [11]. |

| Y-Randomization Test | Statistical Protocol | A validation technique to confirm a model has learned real structure-activity relationships and not just dataset-specific noise [11]. |

| Matched Molecular Pair Analysis (MMPA) | Computational Method | Identifies systematic chemical transformations and their effects on properties, providing interpretable insights for molecular optimization [11]. |

The path toward trustworthy AI in drug discovery is paved with rigorous, evidence-based demonstrations of model robustness. The experimental frameworks of Y-randomization and applicability domain analysis are not merely academic exercises but are essential components of a robust model development workflow. As the field progresses, the integration of these validation techniques with advanced AI models—from XGBoost to graph neural networks—will be critical for building systems that researchers and drug developers can truly rely upon. This ensures that AI serves as a powerful, dependable tool in the mission to deliver safe and effective therapeutics, ultimately fulfilling the promise of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) and creating AI systems whose trustworthiness is built on a foundation of demonstrable robustness [11] [28].

A Practical Guide to Implementing Y-Randomization and Defining the Applicability Domain

Step-by-Step Protocol for Conducting a Y-Randomization Test

This guide provides a detailed protocol for conducting Y-randomization tests, a critical validation procedure in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling. We objectively compare the performance of various validation approaches and present experimental data demonstrating how Y-randomization protects against chance correlations and over-optimistic model interpretation. Framed within broader research on model robustness and applicability domain analysis, this guide equips computational chemists and drug development professionals with standardized methodology for establishing statistical significance in QSAR models.

Y-randomization, also known as Y-scrambling or response randomization, is a fundamental validation procedure used to establish the statistical significance of QSAR models [17]. This technique tests the null hypothesis that the structure-activity relationship described by a model arises from chance correlation rather than a true underlying relationship. As noted by Rücker et al., Y-randomization was historically described as "probably the most powerful validation procedure" in QSAR modeling [17]. The core principle involves repeatedly randomizing the response variable (biological activity) while maintaining the original descriptor matrix, then rebuilding models using the same workflow applied to the original data [17]. If models built with scrambled responses consistently show inferior performance compared to the original model, one can conclude that the original model captures a genuine structure-activity relationship rather than a random artifact.

The critical importance of Y-randomization has increased with modern cheminformatics capabilities, where researchers routinely screen hundreds or thousands of molecular descriptors to select optimal subsets for model building [17]. As Wold pointed out, "if we have sufficiently many structure descriptor variables to select from we can make a model fit data very closely even with few terms, provided that they are selected according to their apparent contribution to the fit. And this even if the variables we choose from are completely random and have nothing whatsoever to do with the current problem!" [17]. This guide provides a standardized protocol for implementing Y-randomization tests, complete with performance comparisons and methodological details to ensure proper application in drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundation and Significance

The Problem of Chance Correlation in QSAR

Chance correlation represents a fundamental risk in QSAR modeling, particularly when descriptor selection is employed. The phenomenon occurs when models appear to have strong predictive performance based on statistical metrics, but the relationship between descriptors and activity is actually random [17]. This risk escalates with the size of the descriptor pool; with thousands of available molecular descriptors, the probability of randomly finding a subset that appears to correlate with activity becomes substantial [17].

Traditional validation methods like cross-validation or train-test splits assess predictive ability but cannot definitively rule out chance correlation. Y-randomization specifically addresses this gap by testing whether the model performance significantly exceeds what would be expected from random data. Livingstone and Salt quantified this selection bias problem through computer experiments fitting random response variables with random descriptors, demonstrating the need for rigorous validation [17].

How Y-Randomization Works

Y-randomization works by deliberately breaking the potential true relationship between molecular structures and biological activity while preserving the correlational structure among descriptors [17]. By comparing the original model's performance against models built with randomized responses, researchers can estimate the probability that the observed performance occurred by chance. A statistically significant original model should outperform the vast majority of its randomized counterparts according to established fitness metrics [17].

Variants of Y-Randomization

Several variants of randomization procedures exist, with differing levels of stringency [17]:

- Basic Y-randomization: Simple permutation of activity values without descriptor reselection

- Complete Y-randomization: Full model rebuilding including descriptor selection for each scramble

- Advanced Y-randomization: Includes descriptor selection from random pseudodescriptors

Table 1: Comparison of Y-Randomization Variants

| Variant | Descriptor Selection | Stringency | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Y-randomization | Uses original descriptor set | Low | Preliminary screening |

| Complete Y-randomization | Full selection from original pool | High | Standard validation |

| Advanced Y-randomization | Selection from random descriptors | Very High | High-stakes model validation |

Experimental Protocol for Y-Randomization

Prerequisites and Preparation

Before initiating Y-randomization, researchers must have developed a QSAR model using their standard workflow, including descriptor calculation, selection, and model building. The original model's performance metrics (e.g., R², Q², RMSE) should be recorded as a baseline for comparison. All data preprocessing steps and model parameters must be thoroughly documented to ensure consistent application during randomization trials.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Record Original Model Performance:

- Document the original model's performance metrics including R², Q², RMSE, and any other relevant statistics

- Note the specific descriptors selected and the final model equation

Randomization Loop Setup:

- Define the number of randomization iterations (typically 100-1000)

- For each iteration, generate a random permutation of the response variable (Y) using a reliable random number generator

Model Reconstruction with Scrambled Data:

- Crucially, for each randomization, repeat the entire model building process including descriptor selection if it was part of the original workflow [17]

- Apply identical preprocessing, variable selection methods, and model building techniques as used for the original model

- Record performance metrics for each randomized model

Performance Comparison:

- Calculate the mean and standard deviation of performance metrics from all randomized models

- Compare the original model's performance against the distribution of randomized models

Statistical Significance Assessment:

- Compute the probability that the original model's performance occurred by chance

- Apply the significance criterion: the original model's fit should exceed the average fit of the best random models obtained through the complete randomization procedure [17]

Figure 1: Y-Randomization Test Workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete process for conducting a Y-randomization test, emphasizing the critical step of rebuilding models with descriptor selection for each permutation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Y-Randomization Tests

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Y-Randomization |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation Software | PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit, Mordred | Generates molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling |

| Statistical Analysis Platforms | R, Python (scikit-learn), MATLAB | Implements randomization algorithms and statistical testing |

| QSAR Modeling Environments | WEKA, KNIME, Orange | Builds and validates QSAR models with standardized workflows |

| Custom Scripting Templates | R randomization scripts, Python permutation code | Automates Y-randomization process and performance tracking |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Case Study: Valid vs. Invalid Y-Randomization Implementation

Experimental data demonstrates the critical importance of proper Y-randomization implementation. In a comparative study, researchers applied both correct and incorrect Y-randomization to the same QSAR dataset [17]:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Y-Randomization Implementation Methods

| Implementation Method | Original Model R² | Average Random Model R² | Statistical Significance | Correct Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incorrect: Fixed descriptors | 0.85 | 0.22 | Apparent p < 0.001 | False positive |

| Correct: Descriptor reselection | 0.85 | 0.79 | p = 0.12 | True negative |

The data clearly shows that using fixed descriptors (the original model's descriptors) with scrambled responses produces deceptively favorable results, as the randomized models cannot achieve good fits with inappropriate descriptors. Only when descriptor selection is included in each randomization cycle does the test accurately reveal the model's lack of statistical significance [17].

Quantitative Assessment Criteria

For a QSAR model to be considered statistically significant based on Y-randomization, it should satisfy the following quantitative criteria [17]:

- The original model's R² should exceed the average R² of random pseudomodels by a substantial margin

- The original model's performance should rank in the top 5% of all randomized models (p < 0.05)

- The difference in performance should be consistent across multiple metrics (R², Q², RMSE)

Rücker et al. propose that "the statistical significance of a new MLR QSAR model should be checked by comparing its measure of fit to the average measure of fit of best random pseudomodels that are obtained using random pseudodescriptors instead of the original descriptors and applying descriptor selection as in building the original model" [17].

Integration with Broader Validation Framework

Relationship to Applicability Domain Analysis

Y-randomization represents one component of a comprehensive QSAR validation framework that must include applicability domain (AD) analysis [26]. While Y-randomization establishes statistical significance, AD analysis defines the chemical space where models can reliably predict new compounds [26]. The reliability-density neighborhood (RDN) approach represents an advanced AD technique that characterizes each training instance according to neighborhood density, bias, and precision [26]. Combining Y-randomization with rigorous AD analysis provides complementary information about model validity and predictive scope.

Comparison with Other Validation Methods

Table 4: Comparison of QSAR Validation Methods

| Validation Method | What It Tests | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-randomization | Statistical significance, chance correlation | Directly addresses selection bias, establishes null hypothesis | Does not assess predictive ability on new compounds |

| Cross-validation | Model robustness, overfitting | Estimates predictive performance, uses all data efficiently | Can be optimistic with strong descriptor selection |

| Train-test split | External predictivity | Realistic assessment of generalization | Reduced training data, results vary with split |

| Applicability Domain | Prediction reliability | Identifies reliable prediction regions, maps chemical space | Multiple competing methods, no standard implementation |

Troubleshooting and Methodological Considerations

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Insufficient Randomization Iterations

- Problem: Low iteration counts (e.g., < 50) provide unreliable significance estimates

- Solution: Use at least 100-1000 iterations depending on dataset size and model complexity

Neglecting Descriptor Selection

- Problem: Using fixed descriptors during randomization produces overly optimistic results [17]

- Solution: Repeat the entire descriptor selection process for each randomization

Inappropriate Randomization Techniques

- Problem: Simple randomization may not fully address all chance correlation mechanisms

- Solution: Consider advanced variants including random pseudodescriptors for maximum stringency [17]

Interpretation Guidelines

Proper interpretation of Y-randomization results requires both quantitative and qualitative assessment:

- Clear Pass: Original model performance substantially exceeds all randomized models (p < 0.01)

- Borderline Case: Original model moderately exceeds most randomized models (0.01 < p < 0.05)

- Clear Failure: Original model performance falls within the distribution of randomized models (p > 0.05)

For borderline cases, researchers should consider additional validation methods and potentially collect more experimental data to strengthen conclusions.

Y-randomization remains an essential component of rigorous QSAR validation, particularly in pharmaceutical development where model reliability directly impacts resource allocation and safety decisions. This guide has presented a standardized protocol emphasizing the critical importance of including descriptor selection in each randomization cycle—a step often overlooked that dramatically affects test stringency and conclusion validity [17]. When properly implemented alongside applicability domain analysis [26] and other validation techniques, Y-randomization provides powerful protection against chance correlation and statistical artifacts. As QSAR modeling continues to evolve with increasingly complex algorithms and descriptor spaces, adherence to rigorous validation standards like those outlined here will remain fundamental to generating scientifically meaningful and reliable models for drug discovery.

Calculating the CR2P Metric and Interpreting Y-Randomization Results

In modern drug development, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models are indispensable for predicting the biological activity of compounds, thereby accelerating candidate optimization and reducing costly late-stage failures [28]. However, the predictive utility of these models depends entirely on their robustness and reliability. A model that performs well on its training data may still fail with new compounds if it has learned random noise rather than true structure-activity relationships.

This is where validation techniques like Y-randomization become crucial. Also known as label scrambling, Y-randomization is a definitive test that assesses whether a QSAR model has captured meaningful predictive relationships or merely reflects chance correlations in the dataset [34]. The CR2P metric (coefficient of determination for Y-randomization) serves as a key quantitative indicator for interpreting these results, providing researchers with a standardized measure to validate their models against random chance.

Theoretical Foundations of Y-Randomization

The Principle of Y-Randomization

Y-randomization tests the fundamental hypothesis that a QSAR model should perform significantly better on the original data than on versions where the relationship between structure and activity has been deliberately broken. This is achieved through multiple iterations of random shuffling of the response variable (biological activity values) while keeping the descriptor matrix unchanged, followed by rebuilding the model using the exact same procedure applied to the original data [34].

The theoretical basis stems from understanding that a model developed using the original response variable should demonstrate substantially superior performance compared to models built with randomized responses. If models trained on scrambled data achieve similar performance metrics as the original model, this indicates that the original model likely captured accidental correlations rather than genuine predictive relationships, rendering it scientifically meaningless and dangerous for decision-making in drug development pipelines.

Variants of Y-Randomization

Research has identified different Y-randomization approaches, each with specific advantages:

- Standard Y-Randomization: Uses the original descriptor pool with permuted response values [34]

- Pseudodescriptor Y-Randomization: Employs random number pseudodescriptors instead of original molecular descriptors [34]

- Double Testing: Compares original model performance against both standard and pseudodescriptor variants for comprehensive validation [34]

These variants address different aspects of validation, with pseudodescriptor testing typically producing higher mean random R² values due to the intercorrelation of real descriptors in the original pool.

Calculating the CR2P Metric

The CR2P Formula

The Coefficient of Determination for Y-Randomization (CR2P) is calculated using the following established formula:

CR2P = R × R²

Where:

- R represents the correlation coefficient between the original model's predicted activities and the randomized model's predicted activities

- R² represents the squared correlation coefficient from the original QSAR model [35]

This metric effectively penalizes models where the predictions from randomized data closely correlate with those from the original model, which would indicate the presence of chance correlations rather than meaningful relationships.

Interpretation Guidelines

The calculated CR2P value provides a clear criterion for assessing model validity:

- CR2P > 0.5: Indicates a powerful model unlikely to be inferred by chance [35]

- CR2P ≤ 0.5: Suggests the model may be based on chance correlations and requires further investigation

This threshold provides researchers with a quantitative benchmark for model acceptance or rejection in rigorous QSAR workflows.

Experimental Protocols for Y-Randomization

Standardized Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive Y-randomization testing protocol:

Detailed Methodological Steps

Develop Original QSAR Model: Construct the initial model using standardized procedures (e.g., GA-MLR, PLS) with the untransformed response variable [35]

Calculate Performance Metrics: Determine key statistics including:

- R² (coefficient of determination)

- Q² (cross-validated R²)

- R²pred (predictive R² for test set)

Implement Y-Randomization:

- Randomly permute the activity values (Y-vector) while maintaining descriptor matrix structure

- Rebuild the model using identical procedures and descriptor selection methods

- Calculate R² for the randomized model

- Repeat for multiple iterations (typically 100+ cycles) [34]

Statistical Comparison:

- Compute average random R² across all iterations

- Compare original R² against distribution of random R² values

- Calculate CR2P metric using the established formula

Result Interpretation:

- Accept model if CR2P > 0.5 and original R² >> average random R²

- Reject model if CR2P ≤ 0.5 or original R² approximates random R²

Comparative Analysis of Y-Randomization Results

Case Studies from Recent Literature

Table 1: Comparative Y-Randomization Results from Published QSAR Studies

| Study Focus | Original R² | Average Random R² | CR2P Value | Model Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Alkoxy Cinnamic Analogues (Anticancer) | 0.7436 | Not Reported | 0.6569 | Accepted (Robust) | [35] |

| Benzoheterocyclic 4-Aminoquinolines (Antimalarial) | Model Not Specified | Not Reported | Not Reported | Validated | [36] |

| NET Inhibitors (Anti-psychotic) | 0.952 | Not Reported | Validated via Y-randomization | Accepted | [37] |

Interpretation of Comparative Data

The case studies demonstrate varied reporting practices in QSAR publications. The 4-alkoxy cinnamic analogues study provides the most complete documentation with a CR2P value of 0.6569, which clearly exceeds the 0.5 threshold and validates model robustness [35]. This indicates a low probability of chance correlation, supporting the model's use for predicting anticancer activity in this chemical series.

The antimalarial and anti-psychotic studies reference Y-randomization validation but omit specific CR2P values, highlighting the need for more standardized reporting in QSAR literature to enable proper assessment and reproducibility [36] [37].

Integration with Applicability Domain Analysis

Complementary Validation Approaches

Y-randomization and CR2P assessment must be complemented by applicability domain (AD) analysis for comprehensive model validation. While Y-randomization tests for chance correlations, AD analysis defines the chemical space where the model can reliably predict new compounds, addressing different aspects of model reliability [37].

The integration of these approaches provides a multi-layered validation strategy:

- Y-randomization: Ensures model is not based on chance correlations

- Applicability domain: Ensures predictions are only made for compounds within the model's chemical space

- External validation: Tests predictive performance on truly independent compounds

Strategic Implementation in Drug Development

In Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), robust QSAR models validated through Y-randomization contribute significantly to early-stage decision-making [28]. These validated models enable:

- More reliable prediction of biological activity for novel compounds

- Improved candidate prioritization before synthesis and testing

- Reduced attrition rates in later, more expensive development stages

- Enhanced understanding of structure-activity relationships

Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for QSAR Model Development and Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in QSAR Validation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL-Descriptor [35], Dragon | Generates molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Calculates 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors; Handles multiple file formats |

| Model Building & Validation | BuildQSAR [35], MATLAB, R | Implements GA-MLR and other algorithms for model development | Genetic Algorithm for variable selection; Built-in validation protocols |

| Y-Randomization Implementation | Custom scripts in R/Python, DTC Lab tools [35] | Automates response permutation and statistical testing | Facilitates multiple randomization iterations; Calculates CR2P metric |