Druggability Assessment of Molecular Targets: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of druggability assessment in modern drug discovery, addressing the high attrition rates in pharmaceutical development.

Druggability Assessment of Molecular Targets: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of druggability assessment in modern drug discovery, addressing the high attrition rates in pharmaceutical development. We examine foundational concepts, computational and experimental methodologies, and optimization strategies for evaluating target druggability—the likelihood of a biological target being effectively modulated by therapeutic agents. For researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides practical insights into structure-based predictions, data-driven approaches, and validation techniques, including specialized considerations for challenging target classes like protein-protein interactions. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this work serves as a strategic guide for prioritizing targets with higher success potential in drug development pipelines.

Understanding Druggability: Fundamental Concepts and Strategic Importance in Target Selection

The concept of druggability is fundamental to modern drug discovery, serving as a critical filter for selecting viable therapeutic targets. Druggability describes the ability of a biological target, typically a protein, to bind with high affinity to a drug molecule, resulting in a functional change that provides a therapeutic benefit to the patient [1]. Importantly, disease relevance alone is insufficient for a protein to serve as a drug target; the target must also be druggable [1]. The term "druggable genome" was originally coined by Hopkins and Groom to describe proteins with genetic sequences similar to known drug targets and capable of binding small molecules compliant with the "rule of five" [1] [2].

The druggability concept has evolved significantly over the past two decades, expanding from its original focus on small molecule binding to encompass biologic medical products such as therapeutic monoclonal antibodies [1]. Contemporary definitions address the more complex question of whether a target can yield a successful drug, considering factors such as disease modification, binding site functionality, selectivity, oral bioavailability, on-target toxicity, and expression in disease-relevant tissue [2]. This multi-parameter problem requires integration of diverse data types and computational approaches to assess effectively.

The Druggable Genome and Target Landscape

The human genome contains approximately 21,000 protein-coding genes, with estimates of the druggable genome ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 targets [3]. However, only a small fraction of human proteins are established drug targets. Current knowledge indicates that approximately 3% of human proteins are known "mode of action" drug targets—proteins through which approved drugs act—while another 7% interact with small molecule chemicals [1]. Based on DrugCentral data, 1,795 human proteins interact with 2,455 approved drugs [1].

Analysis of FDA-approved drugs from 2015-2024 reveals continued focus on major protein families, with G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), kinases, ion channels, and nuclear receptors remaining predominant target classes [3]. However, recent trends show increased exploration of non-protein targets and novel therapeutic modalities, including gene therapies and oligonucleotides [3]. A striking finding from this period is the correlation between regulatory efficiency and innovation, with 73% of 2018 approvals utilizing expedited review pathways and 19 drugs designated as first-in-class [3].

Table 1: Analysis of FDA-Approved Drugs (2015-2024)

| Category | Number | Percentage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total FDA Approvals | 465 | 100% | Average 46.5 drugs annually |

| New Molecular Entities (NMEs) | 332 | 71.4% | Small molecules and macromolecules |

| Biotherapeutics | 133 | 28.6% | Monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, etc. |

| Peak Approval Years | 2018 (59), 2023 (55) | - | Highest in FDA history for this period |

| Expedited Pathway Utilization | - | Up to 73% (2018) | Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, etc. |

The limited scope of successfully targeted proteins highlights the challenge of "undruggable" targets—proteins generally considered inaccessible to therapeutic intervention. Many disease-modifying proteins fall into this category, particularly those involved in protein-protein interactions that occur across relatively flat surfaces with low susceptibility to small molecule binding [1]. It is estimated that only 10-15% of human proteins are disease-modifying while only 10-15% are druggable, meaning only between 1 and 2.25% of disease-modifying proteins are likely to be druggable [1].

Methodologies for Druggability Assessment

Structure-Based Approaches

Structure-based druggability assessment relies on the availability of experimentally determined 3D structures or high-quality homology models. These methods typically involve three main components: (1) identifying cavities or pockets on the protein structure; (2) calculating physicochemical and geometric properties of the pocket; and (3) assessing how these properties fit a training set of known druggable targets, often using machine learning algorithms [1].

Early work on structure-based parameters came from Abagyan and coworkers, followed by Fesik and coworkers, who assessed the correlation of certain physicochemical parameters with hits from NMR-based fragment screens [1]. Commercial tools and databases for structure-based assessment are now available, with public resources like ChEMBL's DrugEBIlity portal providing pre-calculated druggability assessments for all structural domains within the Protein Data Bank [1].

Advanced methods incorporate molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility. Techniques like Mixed-Solvent MD (MixMD) and Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) probe protein surfaces using organic solvent molecules to identify binding hotspots that account for flexibility [4]. For complex conformational transitions, frameworks like Markov State Models (MSMs) and enhanced sampling algorithms (e.g., Gaussian accelerated MD) enable exploration of long-timescale dynamics and discovery of cryptic pockets absent in static structures [4].

Sequence-Based and Machine Learning Approaches

When high-quality 3D structures are unavailable, sequence-based methods offer alternative solutions. These approaches primarily rely on evolutionary conservation analysis, sequence pattern recognition, and homology modeling [4]. Tools like ConSurf identify functionally critical residues conserved across homologs, while PSIPRED and its components (TM-SITE, S-SITE) utilize sequence analysis for binding site prediction [4].

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have revolutionized druggability prediction. Traditional algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RF), and Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) have been successfully deployed in tools like COACH, P2Rank, and various affinity prediction models [4]. These methods excel at integrating diverse feature sets—encompassing geometric, energetic, and evolutionary descriptors—to achieve robust predictions.

More recently, deep learning architectures have demonstrated superior capability in automatically learning discriminative features from raw data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) process 3D structural representations in tools like DeepSite and DeepSurf, while Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) natively handle the non-Euclidean structure of biomolecules [4]. Transformer models, inspired by natural language processing, interpret protein sequences as "biological language," learning contextualized representations that facilitate binding site prediction [4] [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Druggability Assessment Tools

| Tool/Method | Approach | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE+HSAPSO [6] | Stacked Autoencoder with optimization | Feature extraction + parameter optimization | 95.52% accuracy, 0.010 s/sample |

| DrugProtAI [7] | Random Forest, XGBoost | 183 biophysical, sequence, and non-sequence features | AUC-PR 0.87 |

| DrugTar [5] | Deep learning with ESM-2 embeddings | Protein language model + Gene Ontology terms | AUC 0.94, AUPRC 0.94 |

| SPIDER [7] | Stacked ensemble learning | Diverse sequence-based descriptors | Limited by training set size |

| DrugMiner [6] | SVM, Neural Networks | 443 protein features | 89.98% accuracy |

| XGB-DrugPred [6] | XGBoost | Optimized DrugBank features | 94.86% accuracy |

Integrated and Ensemble Approaches

Recognizing that no single method is universally superior, integrated approaches have gained prominence. Ensemble learning methods, such as the COACH server, combine predictions from multiple independent algorithms, often yielding superior accuracy and coverage by leveraging complementary strengths [4]. Simultaneously, multimodal fusion techniques create unified representations by jointly modeling heterogeneous data types, including protein sequences, 3D structures, and physicochemical properties [4].

The partitioning-based method implemented in DrugProtAI represents an innovative approach to address class imbalance in training data [7]. By dividing the majority class (non-druggable proteins) into multiple partitions, each trained against the full druggable set, the method reduces class imbalance and generates multiple models whose collective performance exceeds individual partitions [7].

Experimental Protocols for Druggability Assessment

Structure-Based Druggability Workflow

Objective: To identify and evaluate potential binding sites on protein targets using structural information.

Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain high-quality protein structures from PDB or via homology modeling. Apply standardized preparation including hydrogen addition, missing side-chain completion, and protonation state assignment at physiological pH.

- Binding Site Detection: Utilize geometric and energetic algorithms (e.g., Fpocket, Q-SiteFinder) to identify potential binding cavities. Parameters include:

- Pocket volume and surface area

- Depth and enclosure metrics

- Hydrophobicity and polarity distributions

- Druggability Assessment: Calculate druggability scores using tools like SiteMap (SiteScore, Dscore) that evaluate:

- Size and enclosure (ideal range: 100-500 ų)

- Hydrogen bonding capacity

- Hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity balance

- Dynamics Consideration: Perform molecular dynamics simulations (≥100 ns) or mixed-solvent MD to identify cryptic pockets and assess binding site stability.

- Validation: Compare predictions with known ligand-binding sites from PDB or experimental fragment screening data.

Expected Output: Rank-ordered list of potential binding sites with associated druggability scores and structural validation.

Machine Learning-Based Prediction Protocol

Objective: To classify proteins as druggable or non-druggable using sequence and structural features.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Curate training sets from DrugBank, ChEMBL, and Swiss-Prot with known druggable and non-druggable proteins. Apply careful balancing to address class imbalance [7].

- Feature Extraction: Calculate comprehensive feature sets including:

- Sequence-based: amino acid composition, physicochemical properties, conservation scores

- Structure-based: pocket descriptors, surface geometry, electrostatic potentials

- Evolutionary: domain annotations, phylogenetic profiles, Gene Ontology terms

- Model Training: Implement ensemble classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost) or deep learning architectures (CNN, GNN, Transformers) using cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters.

- Feature Selection: Apply genetic algorithms or recursive feature elimination to identify most predictive features [7].

- Validation: Perform blind testing on independent datasets not used in training. Evaluate using AUC-ROC, AUC-PR, accuracy, and F1-score metrics.

Interpretation: Utilize SHAP values or similar explainable AI techniques to interpret model predictions and identify key druggability determinants [7].

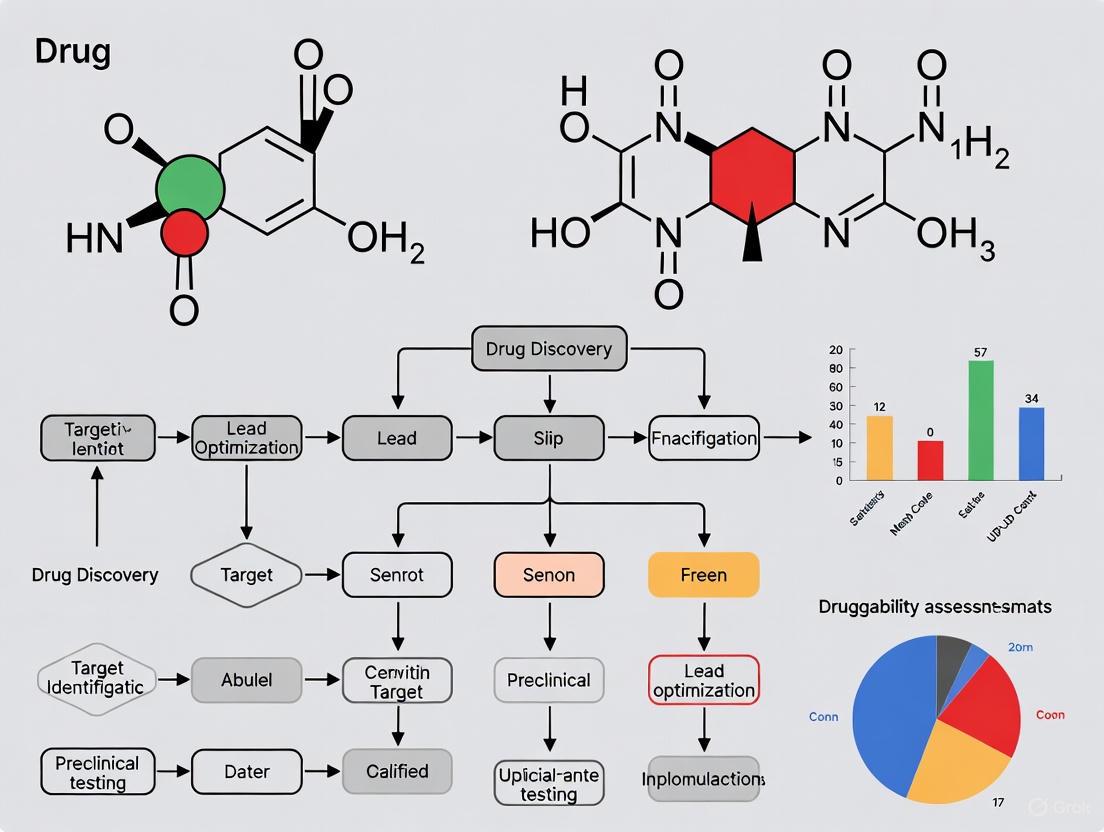

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for Druggability Assessment

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Druggability Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB | Source of protein structures for analysis | Experimental and predicted 3D structures |

| Binding Site Detection | Fpocket, SiteMap, CASTp | Identify potential ligand-binding cavities | Geometric and energetic pocket characterization |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulate protein flexibility and cryptic pockets | Captures conformational dynamics |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implement druggability classification algorithms | Pre-built models and customization options |

| Feature Databases | UniProt, DrugBank, ChEMBL | Source of protein annotations and known drug targets | Comprehensive biological and chemical data |

| Specialized Prediction Tools | DrugTar, DrugProtAI, SPIDER | Webservers for druggability assessment | User-friendly interfaces, pre-trained models |

| Validation Resources | PDBbind, PubChem BioAssay | Experimental data for model validation | Curated protein-ligand interaction data |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

AI and Knowledge Graph Integration

The future of druggability assessment lies in integrating diverse data types into comprehensive knowledge graphs that capture information from gene-level to protein residue-level annotations [2]. Such graphs can incorporate target-disease associations from Open Targets, structural annotations from PDBe-KB, and functional data from various omics technologies [2]. Graph-based AI methods can then expertly navigate these complex knowledge networks to identify promising targets that would be difficult to discern through manual analysis alone [2].

The arrival of AlphaFold 2 has dramatically expanded the structural coverage of the human proteome, making proteome-scale druggability assessment more feasible [2]. However, challenges remain in accurately predicting binding sites from static structures, particularly for transient cryptic pockets that only form in certain conformational states [4].

Expanding Therapeutic Modalities

Traditional druggability concepts focused primarily on small molecule binding are expanding to include diverse therapeutic modalities. Recent FDA approvals include RNA-targeting therapies, protein degraders (PROTACs), and cell and gene therapies, each with their own druggability considerations [3]. The rise of therapeutic biologics is particularly notable, with approval rates for biologics increasing significantly in recent years [3].

Chemoproteomics techniques are expanding the scope of druggable targets by identifying covalently modifiable sites across the proteome [1]. Similarly, approaches targeting protein-protein interactions and allosteric sites are overcoming previous limitations of "undruggable" targets [1] [4].

Safety Prediction and Genetic Evidence

Incorporating safety considerations early in target assessment is becoming increasingly important. The development of genetic priority scores like SE-GPS (Side Effect Genetic Priority Score) leverages human genetic evidence to inform side effect risks for drug targets [8]. These approaches utilize diverse genetic data sources—including clinical variants, single variant associations, gene burden tests, and GWAS loci—to predict potential adverse effects based on the biological consequences of lifelong target modulation [8].

Directional versions of these scores (SE-GPS-DOE) incorporate the direction of genetic effect to determine if genetic risk for phenotypic outcomes aligns with the intended drug mechanism [8]. This represents an important advance in predicting on-target toxicity before significant resource investment in drug development.

Figure 2: Future Framework: Integrated Knowledge Graph for Target Assessment

Druggability assessment has evolved from simple similarity-based predictions to sophisticated multi-parameter analyses that integrate structural, genetic, functional, and chemical information. Computational methods now play a central role in this process, with machine learning and AI approaches dramatically improving prediction accuracy and scalability. The continuing expansion of structural coverage through experimental methods and AlphaFold predictions, combined with growing databases of protein-ligand interactions, provides an increasingly rich foundation for these assessments.

Future advances will likely come from better integration of protein dynamics, more comprehensive knowledge graphs, and improved understanding of how genetic evidence predicts therapeutic outcomes and safety concerns. As these methods mature, they will accelerate the identification of novel targets for currently undruggable diseases, ultimately expanding the therapeutic landscape and bringing new treatments to patients.

The concept of the druggable genome represents a foundational pillar in modern pharmaceutical science, providing a systematic framework for understanding which human genes encode proteins capable of interacting with drug-like molecules. First introduced in the seminal paper by Hopkins and Groom twenty years ago, this paradigm emerged from the completion of the human genome project and recognized that only a specific subset of the newly sequenced genome encoded proteins capable of binding orally bioavailable compounds [2] [9]. This original definition has since evolved beyond simple ligandability—the ability to bind drug-like molecules—to encompass the more complex question of whether a target can yield a successful therapeutic agent [2]. Contemporary definitions integrate multiple parameters including disease modification capability, functional effect upon binding, selectivity potential, on-target toxicity profile, and expression in disease-relevant tissues [9].

The systematic assessment of druggability has become increasingly critical in an era where drug development faces substantial challenges, with only approximately 4% of development programs yielding licensed drugs [10]. This high failure rate stems partly from poor predictive validity of preclinical models and the late-stage acquisition of definitive target validation evidence [10]. Within this context, the druggable genome provides a strategic roadmap for prioritizing targets with the highest probability of clinical success, thereby optimizing resource allocation and reducing attrition rates in drug development pipelines.

Historical Evolution of the Druggable Genome Concept

Foundational Studies and Initial Estimates

The initial estimation of the druggable genome by Hopkins and Groom identified approximately 130 protein families and domains found in targets of existing drug-like small molecules, encompassing over 3,000 potentially druggable proteins containing these domains [10]. This pioneering work established the crucial distinction between "druggable" and "drug target," emphasizing that mere biochemical tractability does not necessarily translate to therapeutic relevance [2] [9]. Early definitions primarily focused on proteins capable of binding orally bioavailable molecules satisfying Lipinski's Rule of Five, which describes molecular properties associated with successful oral drugs [2].

Subsequent refinements by Russ and Lampel and the dGene dataset curated by Kumar et al. maintained similar estimates while incorporating updated genome builds and annotations [10]. These early efforts predominantly focused on small molecule targets, reflecting the pharmaceutical landscape of the early 2000s where small molecules dominated therapeutic development. The historical evolution of druggable genome estimates reflects both technological advances in genomics and changing therapeutic modalities, with later iterations incorporating targets for biologics and novel therapeutic modalities.

Expansion and Contemporary Re-definitions

A significant expansion occurred in 2017 when Finan et al. redefined the druggable genome, estimating that 4,479 (22%) of the 20,300 protein-coding genes annotated in Ensembl v.73 were drugged or druggable [10]. This updated estimate added 2,282 genes to previous calculations through the inclusion of multiple new categories: targets of first-in-class drugs licensed since 2005; targets of drugs in late-phase clinical development; preclinical small molecules with protein binding measurements from ChEMBL; and genes encoding secreted or plasma membrane proteins that form potential targets for monoclonal antibodies and other biotherapeutics [10].

This contemporary stratification organized the druggable genome into three distinct tiers reflecting position in the drug development pipeline:

- Tier 1 (1,427 genes): Efficacy targets of approved small molecules and biotherapeutic drugs plus clinical-phase drug candidates

- Tier 2 (682 genes): Targets with known bioactive drug-like small molecule binding partners or those with ≥50% identity over ≥75% of sequence with approved drug targets

- Tier 3 (2,370 genes): Encoded secreted or extracellular proteins, proteins with more distant similarity to approved drug targets, and members of key druggable gene families not in Tiers 1 or 2 [10]

This tiered classification system enables more nuanced target prioritization, reflecting varying levels of validation confidence and druggability evidence.

Quantitative Landscape of the Druggable Genome

The quantitative landscape of the druggable genome has been systematically cataloged in public resources, with the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) representing a comprehensive knowledge base. The 2024 update of TTD provides extensive druggability characteristics for thousands of targets across different development stages [11].

Table 1: Current Landscape of Therapeutic Targets and Drugs in TTD (2024)

| Category | Target Count | Drug Count | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful Targets | 532 | 2,895 | Targets of FDA-approved drugs |

| Clinical Trial Targets | 1,442 | 11,796 | Targets of investigational drugs in clinical trials |

| Preclinical/Patented Targets | 239 | 5,041 | Targets with preclinical or patented drug candidates |

| Literature-Reported Targets | 1,517 | 20,130 | Targets with experimental evidence from literature |

| Total | 3,730 | 39,862 | Comprehensive coverage of known targets and agents |

These statistics reveal that approximately 22% of human proteins with roles in disease represent the most promising subset for therapeutic targeting [9]. The expanding coverage of structural information, with an estimated 70% of the human proteome covered by homologous protein structures, significantly enhances druggability assessment capabilities [2].

Druggability Characteristics Framework

The TTD database organizes druggability characteristics into three distinct perspectives, each with specific sub-categories that enable comprehensive target evaluation [11]:

Table 2: Druggability Characteristics Framework in TTD

| Perspective | Characteristic Category | Assessment Metrics | Application in Target Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Interactions/Regulations | Ligand-specific spatial structure | Binding pocket residues, interaction distances (<5Å) | Informs rational drug design and lead optimization |

| Network properties | Node degree, betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient | Differentiates targets with speedy vs. non-speedy clinical development | |

| Microbiota-drug bidirectional regulations | Drug metabolism impact, microbiota composition changes | Predicts toxicity and bioavailability issues | |

| Human System Profile | Similarity to human proteins | Sequence similarity outside protein families | Assess potential for off-target effects |

| Pathway essentiality | Involvement in life-essential pathways | Informs mechanism-based toxicity risk | |

| Organ distribution | Expression patterns across human organs | Guides tissue-specific targeting strategies | |

| Cell-Based Expression Variation | Disease-specific expression | Differential expression across disease states | Supports target-disease association evidence |

| Exogenous stimulus response | Expression changes induced by external stimuli | Identifies dynamically regulated targets | |

| Endogenous factor regulation | Expression altered by human internal factors | Reveals homeostatic control mechanisms |

This comprehensive framework moves beyond simple binding pocket analysis to incorporate systems biology and physiological context, enabling multi-dimensional druggability assessment.

Methodological Approaches for Druggability Assessment

Structure-Based Druggability Assessment

Structure-based approaches form the cornerstone of experimental druggability assessment, leveraging the growing repository of protein structural information in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). These methods generally comprise three key components: binding site identification, physicochemical property analysis, and validation against reference targets with known druggability outcomes [12].

Pocket Detection Algorithms employ either geometry-based approaches (utilizing 3D grids, sphere-filling, or computational geometry) or methods combining geometric and physicochemical considerations to identify potential binding sites [12]. The Exscientia automated pipeline exemplifies modern scalable approaches, processing all available structures for a target to account for conformational diversity rather than relying on single static structures [2]. This workflow involves structure preparation to address common issues like missing atoms or hydrogens, followed by robust pocket detection across multiple structures per target [2].

Discrimination Functions apply biophysical modeling, linear regression, or support vector machines to quantify druggability using descriptors derived from binding site surfaces [12]. Seminal work by Hajduk et al. established that experimental nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) screening hit rates correlated with computed pocket properties, enabling predictive druggability assessment [12]. Hotspot-based approaches provide residue-level scoring using either molecular dynamics or static structures, offering granular insights into binding site energetics [2] [9].

Structure-Based Druggability Assessment Workflow

Knowledge Graphs and AI-Driven Approaches

The integration of diverse data sources into unified knowledge graphs represents a paradigm shift in druggability assessment. While individual resources like Open Targets (focusing on target-disease associations), canSAR (providing structure-based and ligand-based druggability scores), and PDBe-KB (offering residue-level annotations) provide valuable standalone information, their combination enables more comprehensive evaluation [2] [9].

Modern approaches aim to construct knowledge graphs incorporating annotations from the residue level up to the gene level, creating connections that represent biological pathways and protein-protein interactions [2]. This integrated approach captures the complexity of biological systems but generates data complexity that challenges human interpretation. Consequently, graph-based artificial intelligence methods are being deployed to navigate these knowledge graphs expertly, identifying patterns and relationships that might escape human analysts [2] [9].

The implementation of automated, scalable workflows for hotspot-based druggability assessment across all available structures for large target numbers represents a significant advancement. Companies like Exscientia have developed cloud-based pipelines that generate druggability profiles for each target while retaining essential details about non-conserved binding pockets across different conformational states [2]. These approaches leverage automation to confidently expand the druggable genome into novel and overlooked areas that might be missed through manual assessment.

Essential Databases and Knowledgebases

The experimental and computational assessment of druggability relies on numerous publicly available databases that provide specialized data types relevant to target evaluation.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Druggability Assessment

| Resource Name | Data Type | Primary Application | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) | Comprehensive target-disease associations with druggability characteristics | Multi-perspective target assessment and prioritization | Web interface, downloadable data [11] |

| Open Targets Platform | Target-disease evidence, tractability assessments for small molecules, antibodies, PROTACs | Target identification and validation with genetic evidence | UI, JSON, Parquet, Apache Spark, Google BigQuery, GraphQL API [2] [9] |

| canSAR | Integrated drug discovery data including structure/ligand/network-based druggability scores | 3D structural analysis and ligandability assessment | Web interface [2] [9] |

| PDBe Knowledge Base | Functional annotations and predictions at protein residue level in 3D structures | Residue-level functional annotation and binding site analysis | UI, Neo4J Graph Database, GraphQL API [2] [9] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactive drug-like small molecules, binding properties | Compound tractability evidence and chemical starting points | Web interface, downloadable data [2] |

| GWAS Catalog | Genome-wide association studies linking genetic variants to traits and diseases | Genetic validation of target-disease associations | Web interface, downloadable data [10] |

Experimental and Computational Tools

Beyond databases, specific experimental and computational tools enable practical druggability assessment:

Structure-Based Assessment Tools include both geometric pocket detection algorithms (LIGSITE, SURFNET, PocketDepth) and methods combining geometry with physicochemical properties [12]. Molecular dynamics simulations capture protein flexibility but remain computationally expensive for proteome-scale application [2]. Modern implementations like Schrödinger's computational platform provide integrated workflows for binding site detection, druggability assessment, and target prioritization, incorporating free energy perturbation methods for binding affinity prediction [13].

Genetic Validation Tools leverage human genetic evidence to support target identification, with the recognition that clinically relevant associations of variants in genes encoding drug targets can model the effect of pharmacological intervention on the same targets [10]. This Mendelian randomization approach provides human-based evidence for target validation before substantial investment in drug development.

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Proteome-Scale Expansion and AlphaFold Impact

The ambition to perform druggability assessment at the proteome scale has been dramatically advanced by the arrival of AlphaFold 2 (AF2), which provides highly accurate protein structure predictions for virtually the entire human proteome [2]. This expansion of structural coverage enables the application of structure-based druggability methods to previously inaccessible targets, particularly those with no experimentally determined structures.

The integration of AF2 predictions with experimental structures in unified assessment pipelines represents a promising approach to comprehensively characterize the structural landscape of potential drug targets. However, important considerations remain regarding the static nature of these predictions and their ability to capture conformational diversity relevant to ligand binding [2].

AI and Automation in Target Prioritization

The future of druggability assessment lies in the expert integration of multi-scale data through artificial intelligence approaches. As noted in contemporary perspectives, "Bringing together annotations from the residue up to the gene level and building connections within the graph to represent pathways or protein-protein interactions will create complexity that mirrors the biological systems they represent. Such complexity is difficult for the human mind to utilise effectively, particularly at scale. We believe that graph-based AI methods will be able to expertly navigate such a knowledge graph, selecting the targets of the future" [2].

The development of automated, scalable workflows for structure-based assessment represents a critical step toward this future. These systems leverage cloud computing and robust automation platforms to process all available structural data for targets, providing consistent, comprehensive druggability profiles that account for conformational diversity and structural variations [2].

AI-Driven Knowledge Graph for Target Prioritization

Expanding Therapeutic Modalities

Contemporary druggability assessment must accommodate an expanding repertoire of therapeutic modalities beyond traditional small molecules. The updated druggable genome now includes targets for biologics, particularly monoclonal antibodies targeting secreted proteins and extracellular domains [10]. More recently, assessment frameworks have incorporated tractability data for PROTACs (proteolysis targeting chimeras) that catalyze target protein degradation rather than simple inhibition [2].

This expansion reflects the evolving therapeutic landscape and the need for modality-specific druggability criteria. While small molecule druggability emphasizes the presence of well-defined binding pockets with suitable physicochemical properties, biologics assessment focuses on extracellular accessibility, immunogenicity considerations, and manufacturability. These modality-specific requirements necessitate tailored assessment frameworks while maintaining integrated prioritization across therapeutic approaches.

The concept of the druggable genome has evolved substantially from its original formulation twenty years ago, expanding from a limited set of proteins binding drug-like molecules to a comprehensive framework for systematic target assessment incorporating genetic validation, structural characterization, and physiological context. The integration of diverse data sources into unified knowledge graphs, combined with AI-driven analysis approaches, promises to transform target identification and validation, potentially reversing the low success rates that have plagued drug development.

As these methodologies mature, the field moves toward proteome-scale druggability assessment powered by AlphaFold-predicted structures and automated analysis pipelines. This comprehensive approach will illuminate previously overlooked targets and enable more informed prioritization decisions, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for human disease. The ongoing challenge remains the translation of druggability assessments into clinical successes, maintaining the crucial distinction between "druggable" and "high-quality drug target" that Hopkins and Groom recognized at the inception of this field.

The biopharmaceutical industry is operating at unprecedented levels of research and development activity, with over 23,000 drug candidates currently in development and more than 10,000 in clinical stages [14]. Despite this remarkable investment exceeding $300 billion annually, the industry faces a critical productivity crisis characterized by rising development costs, prolonged timelines, and unsustainable attrition rates [14]. The success rate for Phase 1 drugs has plummeted to just 6.7% in 2024, compared to 10% a decade ago, driving the internal rate of return for R&D investment down to 4.1%—well below the cost of capital [14].

This article examines how systematic druggability assessment of molecular targets presents a fundamental strategy for addressing these challenges. Druggability, defined as the likelihood of a target being effectively modulated by drug-like agents, provides a critical framework for de-risking drug development through early and comprehensive target evaluation [11]. By integrating advanced computational approaches, multi-dimensional druggability characteristics, and data-driven decision-making, researchers can significantly improve R&D productivity and navigate the largest patent cliff in history, which places an estimated $350 billion of revenue at risk between 2025 and 2029 [14].

The Druggability Assessment Framework

Multi-Dimensional Druggability Characteristics

The Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) 2024 version provides a systematic framework for evaluating druggability across three distinct perspectives, comprising nine characteristic categories that enable comprehensive target assessment [11]. This framework facilitates early-stage evaluation of target quality and intervention potential, addressing a critical need in pharmaceutical development where traditional single-characteristic assessment often proves insufficient.

Table 1: Multi-Dimensional Druggability Assessment Framework

| Assessment Perspective | Characteristic Category | Description | Application in Target Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Interactions/Regulations | Ligand-specific spatial structure | Drug binding pocket architecture and residue interactions | Essential for structure-based drug design and lead optimization |

| Network properties | Protein-protein interaction metrics (betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient) | Differentiates targets with speedy vs. non-speedy clinical development | |

| Bidirectional microbiota regulations | Microbiota-drug interactions impacting bioavailability and toxicity | Predicts gastrointestinal toxicity and drug metabolism issues | |

| Human System Profile | Similarity to human proteins | Sequence/structural similarity to proteins outside target families | Informs selectivity concerns and potential off-target effects |

| Pathway essentiality | Involvement in well-established life-essential pathways | Anticipates mechanism-based toxicity and safety liabilities | |

| Organ distribution | Expression patterns across human organs and tissues | Predicts tissue-specific exposure and potential adverse effects | |

| Cell-Based Expression Variations | Disease-specific expression | Varied expression across different disease contexts | Identifies novel targets with crucial disease roles |

| Exogenous stimulus response | Differential expressions induced by external stimuli | Reveals drug-drug interaction and environmental impact potential | |

| Endogenous factor modifications | Expression alterations from internal human factors | Informs personalized medicine approaches and patient stratification |

Quantitative Impact of Druggability Assessment

The implementation of systematic druggability assessment has demonstrated measurable benefits across key drug development metrics. Current data reveals that comprehensive evaluation of the druggability characteristics outlined in Table 1 can significantly improve development outcomes, particularly when applied during target selection and validation stages.

Table 2: Druggability Impact on Development Metrics

| Development Metric | Current Industry Standard | With Druggability Assessment | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 Success Rate | 6.7% [14] | Up to 95.5% classification accuracy [6] | ~14-fold increase |

| R&D Internal Rate of Return | 4.1% [14] | Not quantified | Below cost of capital |

| Computational Efficiency | Traditional methods (SVM, XGBoost) [6] | 0.010 s per sample [6] | Significant acceleration |

| Model Stability | Variable performance [6] | ± 0.003 variability [6] | Enhanced reliability |

| Development Timeline | 10-17 years [6] | Not quantified | Substantial reduction potential |

Computational Methodologies for Druggability Assessment

Methodological Approaches and Applications

The prediction of protein-ligand binding sites has become a central component of modern drug discovery, with computational methods overcoming the constraints of traditional experimental approaches that feature long cycles and high costs [15]. Four main methodological categories have emerged, each with distinct advantages and implementation considerations.

Table 3: Computational Methods for Druggable Site Identification

| Method Category | Fundamental Principles | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Methods | Molecular dynamics simulation, binding pocket detection | High accuracy for targets with known structures | Limited to targets with structural data |

| Sequence-Based Methods | Evolutionary conservation, homology modeling | Applicable to targets without structural data | Lower resolution than structure-based methods |

| Machine Learning-Based Methods | Artificial intelligence, deep learning, feature learning | Handles complex, high-dimensional data | Requires large training datasets |

| Druggability Assessment Methods | Binding site feature analysis, physicochemical properties | Direct relevance to drug development decisions | May oversimplify complex biological systems |

Advanced AI-Driven Workflows

Recent advancements integrate stacked autoencoder (SAE) networks with hierarchically self-adaptive particle swarm optimization (HSAPSO) to create a novel framework (optSAE + HSAPSO) that achieves 95.52% accuracy in drug classification and target identification tasks [6]. This approach demonstrates significantly reduced computational complexity (0.010 s per sample) and exceptional stability (± 0.003), addressing key limitations of traditional methods like support vector machines and XGBoost that struggle with large, complex pharmaceutical datasets [6].

The experimental workflow begins with rigorous data preprocessing from established sources including DrugBank and Swiss-Prot, followed by feature extraction through the stacked autoencoder, which learns hierarchical representations of molecular data [6]. The HSAPSO algorithm then adaptively optimizes hyperparameters, dynamically balancing exploration and exploitation to enhance convergence speed and stability in high-dimensional optimization problems [6].

AI-Driven Druggability Assessment Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Druggability Assessment

Protocol 1: Binding Pocket Identification and Analysis

Objective: To identify and characterize drug binding pockets using structural bioinformatics approaches.

Methodology:

- Structure Retrieval: Conduct comprehensive search of target structures in Protein Data Bank (PDB) using target names and synonyms [11].

- False Match Removal: Manually validate retrieved structures to eliminate incorrect matches, resulting in >25,000 target crystal structures for comprehensive analysis [11].

- Drug Binding Verification: Investigate availability of drug binding to these structures and identify corresponding drugs through systematic screening.

- Co-crystal Structure Analysis: Obtain co-crystal structures containing both target and interacting drug; calculate drug-residue distances using biopython [11].

- Pocket Definition: Define 'drug binding pocket' as all residues interacting with drug at distance <5 Å, based on established structural conventions [11].

- Visualization and Annotation: Generate van der Waals surface representations using iCn3D; annotate with structural resolution, sequence, and mutation data [11].

Output: Ligand-specific binding pockets for 319 successful, 427 clinical trial, 116 preclinical/patented, and 375 literature-reported targets identified from 22,431 complex structures [11].

Protocol 2: Network-Based Druggability Assessment

Objective: To evaluate target druggability through protein-protein interaction network properties.

Methodology:

- Network Construction: Collect high-confidence PPIs (confidence score ≥0.95) from STRING database; construct human PPI network comprising 9,309 proteins and 52,713 interactions [11].

- Property Calculation: Compute nine representative network properties (betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient, etc.) for each target using graph theory algorithms [11].

- Two-Layer Visualization: Generate hierarchical PPI network illustrations highlighting immediate and secondary interactions.

- Speed Classification: Apply network descriptors to differentiate targets of rapid (speedy) and slow (non-speedy) clinical development processes.

- Integration: Combine network metrics with other druggability characteristics for comprehensive assessment.

Output: Network properties for 426 successful, 727 clinical trial, 143 preclinical/patented, and 867 literature-reported targets [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational assessment of druggability relies on specialized reagents, databases, and analytical tools that enable comprehensive target evaluation.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Druggability Assessment

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) | Provides comprehensive druggability characteristics for 3,730 targets [11] | Target selection and validation |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for protein-ligand co-crystal structures [11] | Binding pocket identification and analysis |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network data with confidence scores [11] | Network-based druggability assessment |

| iCn3D | Molecular visualization tool for structural analysis [11] | Binding pocket visualization and characterization |

| BioPython | Python library for biological computation [11] | Structural analysis and distance calculations |

| optSAE + HSAPSO Framework | Integrated deep learning and optimization algorithm [6] | High-accuracy drug classification and target identification |

| DrugBank Database | Comprehensive drug and target information [6] | Model training and validation |

| Swiss-Prot Database | Curated protein sequence and functional information [6] | Feature extraction and model training |

Integrated Druggability Assessment Strategy

A comprehensive druggability assessment strategy requires the integration of computational, structural, and systems-level approaches to effectively de-risk drug development. The relationship between assessment methodologies and their impact on development attrition reveals a strategic framework for implementation.

Integrated Druggability Assessment Strategy

Implementation Framework

Successful implementation requires sequential application of assessment methodologies:

- Early-Stage Computational Screening: Apply AI-driven models (optSAE + HSAPSO) for initial target prioritization based on classification accuracy exceeding 95% [6].

- Structural Validation: Conduct binding pocket identification and analysis for prioritized targets using PDB structures and distance-based mapping [11].

- Systems-Level Profiling: Evaluate network properties, pathway involvement, and expression variations to identify potential development challenges [11].

- Integrative Decision-Making: Combine multidimensional druggability characteristics to build target portfolios aligned with strategic R&D objectives [14].

This integrated approach enables data-driven portfolio management, helping organizations focus resources on targets with the highest probability of technical success while navigating the competitive landscape intensified by the upcoming patent cliff [14].

Druggability assessment represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical R&D, directly addressing the core challenges of unsustainable attrition rates and declining productivity. By implementing comprehensive druggability evaluation frameworks that integrate computational, structural, and systems-level approaches, research organizations can significantly improve development outcomes. The availability of specialized databases like TTD, advanced computational methods like optSAE + HSAPSO, and systematic assessment protocols provides the necessary toolkit for this transformation. As the industry faces unprecedented challenges including the largest patent cliff in history, strategic focus on druggability assessment will be essential for building sustainable R&D pipelines and delivering innovative therapies to patients.

The systematic assessment of a protein's druggability—its ability to be modulated by a drug-like small molecule—represents a critical initial step in modern drug discovery. With approximately 20,000 proteins constituting the human proteome, only a minority possess the inherent characteristics necessary for effective therapeutic targeting [13]. Druggability assessment has evolved from experimental trial-and-error to a sophisticated computational discipline that predicts target engagement potential through analysis of binding pocket structural features and molecular interaction capabilities. This paradigm shift enables researchers to prioritize targets with the highest probability of success before committing substantial resources to development programs.

The fundamental premise underlying druggability assessment rests on the principle that similar binding pockets tend to bind similar ligands [16]. This chemogenomic principle connects the structural biology of proteins with the chemical space of small molecules, enabling computational predictions of binding potential. Current approaches leverage both experimentally determined structures and AlphaFold2-predicted models to systematically identify and characterize druggable sites across entire proteomes, with recent studies identifying over 32,000 potential binding sites across human protein domains [16]. This whitepaper examines the key structural characteristics, computational assessment methodologies, and experimental validation protocols essential for comprehensive druggability evaluation within the broader context of molecular target research.

Fundamental Characteristics of Druggable Binding Pockets

Structural and Physicochemical Properties

Druggable binding pockets exhibit distinct structural and physicochemical properties that enable high-affinity binding to drug-like small molecules. These properties collectively create complementary environments for specific molecular interactions:

Pocket Geometry: Druggable pockets typically display sufficient volume (often 500-1000 ų) and depth to accommodate drug-sized molecules while maintaining structural definition. Compactness and enclosure contribute to binding strength by increasing ligand-protein contact surfaces [17]. Recent analyses of the human proteome have systematically categorized pocket geometries, enabling similarity-based searches across protein families [16].

Surface Characteristics: The composition and character of the pocket surface critically influence binding potential. Apolar surface area facilitates hydrophobic interactions, while specific polar regions enable hydrogen bonding and electrostatic complementarity. Surface flexibility, particularly in loop regions, allows induced-fit binding to diverse ligand structures [17].

Hydrophobic-Hydrophilic Balance: Optimal druggable pockets maintain a balanced distribution of hydrophobic and hydrophilic character, creating environments suitable for drug-like molecules that typically possess logP values in the 1-5 range. This balance enables both desolvation and specific molecular interactions [17].

Molecular Interaction Capabilities

The interaction capabilities of binding pockets determine both binding affinity and specificity through well-defined physicochemical mechanisms:

Hydrogen Bonding Networks: Druggable pockets contain strategically positioned hydrogen bond donors and acceptors that form directional interactions with ligands. The spatial arrangement and accessibility of these groups significantly influence binding selectivity. Complementary donor-acceptor patterns between protein and ligand maximize binding energy [17].

Hydrophobic Interactions: Extended apolar regions in binding pockets facilitate van der Waals interactions and hydrophobic driving forces that contribute substantially to binding free energy. These interactions provide affinity for ligand hydrophobic moieties while enabling desolvation during the binding process [17].

Electrostatic Complementarity: The distribution of charged residues in and around the binding pocket creates electrostatic potential fields that guide ligand binding and enhance affinity for complementary charged groups on ligands. Optimal druggable pockets often contain localized charge distributions rather than uniformly charged surfaces [17].

Aromatic and Cation-π Interactions: Presence of aromatic residues (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) enables π-π and cation-π interactions that provide additional binding energy and directional preference for ligand positioning [17].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Druggable Binding Pockets

| Characteristic Category | Specific Properties | Typical Range/Features | Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Properties | Volume | 500-1000 ų for small molecule drugs | Fpocket, SiteMap |

| Depth & Enclosure | Sufficient to envelop ligand | POCASA, DepthMap | |

| Surface Shape | Complementary to ligand morphology | Surface mapping | |

| Physicochemical Properties | Hydrophobic Surface Area | 40-70% of total surface area | Voronota, CASTp |

| Hydrogen Bond Capacity | Balanced donor/acceptor distribution | HBPLUS, LigPlot+ | |

| Surface Flexibility | Moderate for induced-fit recognition | Molecular dynamics | |

| Interaction Potential | Hot Spot Strength | Strong binding energy regions | FTMap, Mixed-solvent MD |

| Interaction Diversity | Multiple interaction types available | Pharmacophore analysis | |

| Subpocket Definition | Well-divided regions for ligand groups | Pocket segmentation |

Computational Methodologies for Binding Site Detection and Characterization

Structure-Based Binding Site Identification

Structure-based methods leverage three-dimensional protein structures to identify and characterize potential binding pockets through geometric and energetic analyses:

Pocket Detection Algorithms: Computational tools including Fpocket, SiteMap, and CASTp employ geometric criteria to locate cavity regions on protein surfaces. These algorithms typically use alpha spheres, Voronoi tessellation, or grid-based methods to define potential binding sites based on shape characteristics [15]. The resulting pockets are ranked by various druggability metrics including volume, hydrophobicity, and enclosure.

Molecular Interaction Field Analysis: Methods such GRID and WaterMap calculate interaction energies between chemical probes and protein structures to identify favorable binding regions. These approaches provide detailed energetic landscapes of binding sites, highlighting regions with potential for specific molecular interactions including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contact, and electrostatic complementarity [15].

Mixed-Solvent Molecular Dynamics: Molecular dynamics simulations with water-organic cosolvent mixtures identify regions where organic molecules preferentially accumulate, indicating potential binding hot spots. This method effectively captures the dynamic nature of protein surfaces and can reveal cryptic binding sites not apparent in static crystal structures [17].

Pocket Descriptor Generation and Similarity Assessment

Recent advances in binding site characterization employ descriptor-based approaches that enable quantitative comparison of pockets across the proteome:

PocketVec Descriptors: The PocketVec approach generates fixed-length vector descriptors for binding pockets through inverse virtual screening of lead-like molecules. Instead of directly characterizing pocket geometry, it assesses how a pocket ranks a predefined set of small molecules through docking, creating a "fingerprint" based on binding preferences [16]. This method performs comparably to leading methodologies while addressing limitations related to requirements for co-crystallized ligands.

Machine Learning-Based Druggability Prediction: Tools like DrugTar integrate protein sequence embeddings from pre-trained language models (ESM-2) with gene ontology terms to predict druggability through deep neural networks. This approach has demonstrated superior performance (AUC = 0.94) compared to state-of-the-art methods, revealing that protein sequence information is particularly informative for druggability prediction [5].

Binding Site Similarity Networks: By generating descriptors for thousands of pockets across the proteome, researchers can construct similarity networks that reveal unexpected relationships between binding sites in unrelated proteins. These analyses enable identification of novel off-targets and drug repurposing opportunities through systematic comparison of pocket features [16].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Binding Site Analysis

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Principles | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry-Based Detection | Fpocket, SiteMap, CASTp | Voronoi tessellation, Alpha spheres, Surface mapping | Initial pocket identification, Volume calculation | Limited physicochemical information |

| Energy-Based Analysis | GRID, FTMap, WaterMap | Molecular interaction fields, Probe binding energies | Hot spot identification, Interaction potential | Computational intensity, Parameter sensitivity |

| Simulation-Based Methods | Mixed-solvent MD, Markov models | Molecular dynamics, Cosolvent accumulation | Cryptic site discovery, Dynamic pocket characterization | High computational cost, Sampling challenges |

| Descriptor-Based Approaches | PocketVec, SiteAlign, MaSIF | Inverse virtual screening, Pocket fingerprinting | Proteome-wide comparison, Off-target prediction | Training data dependence, Representation limits |

| Machine Learning Methods | DrugTar, SPIDER, Ensemble learning | Sequence/structure feature integration, Pattern recognition | Druggability classification, Target prioritization | Generalization challenges, Interpretability issues |

Advanced Topics in Druggable Target Characterization

Cryptic Binding Sites and Their Druggability

Cryptic binding sites represent a promising frontier in expanding the druggable proteome, particularly for targets lacking conventional binding pockets:

Definition and Identification: Cryptic sites are binding pockets not present in ligand-free protein structures but formed upon ligand binding or through protein dynamics. These sites can be identified through molecular dynamics simulations, Markov state models, and accelerated sampling methods that capture conformational transitions revealing transient pockets [17]. Recent analyses indicate that 80% of proteins with cryptic sites have other ligand-free structures with at least partially open pockets, suggesting a continuum of pocket accessibility [17].

Druggability Limitations: The therapeutic potential of cryptic sites depends critically on their opening mechanism. Sites formed primarily by side chain motions typically demonstrate limited ability to bind drug-sized molecules with high affinity (Kd values rarely below micromolar range). In contrast, sites formed through loop or hinge motion often present valuable drug targeting opportunities [17]. This distinction reflects differences in the timescales and energy barriers associated with side chain versus backbone motions.

Assessment Methods: FTMap, a computational mapping program that identifies binding hot spots, can detect potential cryptic sites even in unbound structures, though it may overestimate their druggability [17]. Mixed-solvent molecular dynamics simulations provide more realistic assessment by explicitly modeling protein flexibility and cosolvent interactions to identify stabilization mechanisms for cryptic pockets.

Deep Learning in Molecular Docking and Binding Assessment

Deep learning approaches are transforming molecular docking and binding assessment through improved pose prediction and affinity estimation:

Performance Benchmarking: Recent comprehensive evaluations categorize docking methods into four performance tiers: traditional methods (Glide SP) > hybrid AI scoring with traditional conformational search > generative diffusion methods (SurfDock, DiffBindFR) > regression-based methods [18]. Generative diffusion models achieve superior pose accuracy (SurfDock: 91.76% on Astex diverse set), while hybrid methods offer the best balanced performance.

Limitations and Challenges: Despite advances, deep learning docking methods exhibit significant limitations in physical plausibility and generalization. Regression-based models frequently produce physically invalid poses, and most deep learning methods show high steric tolerance and poor performance on novel protein binding pockets [18]. These limitations highlight the continued importance of physics-based validation for computational predictions.

Integration with Druggability Assessment: Deep learning approaches enable proteome-scale docking screens that systematically evaluate potential ligand interactions across entire protein families. The PocketVec methodology demonstrates how docking-based descriptors can facilitate binding site comparisons beyond traditional sequence or fold similarity, revealing novel relationships between seemingly unrelated proteins [16].

Experimental Protocols for Druggability Assessment

Protocol 1: Systematic Binding Site Detection and Characterization

This protocol provides a comprehensive workflow for identifying and evaluating binding pockets using integrated computational approaches:

Input Structure Preparation: Obtain high-quality three-dimensional protein structures from experimental sources (PDB) or prediction tools (AlphaFold2). For structures with missing residues, employ homology modeling or loop reconstruction to complete the structure. Remove existing ligands but retain crystallographic waters.

Binding Pocket Identification:

- Execute Fpocket algorithm with default parameters to identify potential binding cavities.

- Perform SiteMap analysis using Schrödinger Suite with extended search parameters to ensure comprehensive pocket detection.

- For each identified pocket, calculate geometric properties including volume, depth, and surface area.

Pocket Characterization:

- Run FTMap analysis to identify binding hot spots through small organic probe mapping.

- Perform mixed-solvent molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) with 5-10% isopropanol or acetonitrile cosolvent to identify regions of preferential cosolvent accumulation.

- Calculate physicochemical properties for each pocket using Voronota or other surface analysis tools.

Druggability Assessment:

- Generate PocketVec descriptors for each pocket through inverse virtual screening against lead-like molecule libraries.

- Compute druggability scores using DrugTar or similar machine learning classifiers.

- Compare pockets against proteome-wide databases to identify similar binding sites in unrelated proteins.

Validation and Prioritization:

- Select top candidate pockets based on composite druggability scores.

- Validate pocket stability through additional molecular dynamics simulations in aqueous solution.

- Prioritize targets for experimental verification based on druggability metrics and biological relevance.

Protocol 2: Cryptic Binding Site Identification and Evaluation

This specialized protocol focuses on detecting and assessing transient binding pockets:

System Setup:

- Prepare apo protein structure with special attention to protonation states of ionizable residues.

- Solvate the system in explicit water with 5-10% cosolvent (typically isopropanol or acetonitrile).

Enhanced Sampling Simulations:

- Perform accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) or temperature replica exchange MD (T-REMD) to enhance conformational sampling.

- Utilize collective variable-based enhanced sampling methods (metadynamics, umbrella sampling) to specifically probe pocket opening transitions.

- Run simulations for sufficient time to observe multiple opening/closing events (typically 500 ns - 1 μs).

Pocket Formation Analysis:

- Cluster simulation trajectories based on pocket volume and shape metrics.

- Identify frames with potential cryptic pocket formation using volumetric analysis tools.

- Characterize the mechanism of pocket opening (side chain motion, loop rearrangement, hinge motion).

Druggability Assessment for Cryptic Sites:

- Apply FTMap to representative structures with open cryptic pockets to assess hot spot strength.

- Evaluate the energetic cost of pocket opening through free energy calculations.

- Assess ligandability through docking studies with flexible side chains in the binding region.

Experimental Validation Planning:

- Design biophysical assays (SPR, ITC) to detect weak binding fragments.

- Plan X-ray crystallography screens with fragment libraries to experimentally validate cryptic site binding.

- Consider chemical strategies (covalent tethering, molecular glues) to stabilize open conformations.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Druggability Assessment Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Services | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB, ModelArchive | Source of protein structures for analysis | Initial target assessment, Comparative studies |

| Pocket Detection Software | Fpocket, SiteMap, CASTp, POCASA | Geometric identification of binding cavities | Primary binding site discovery, Pocket characterization |

| Molecular Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, Desmond | Molecular dynamics simulations | Cryptic site identification, Pocket flexibility assessment |

| Binding Analysis Tools | FTMap, WaterMap, GRID, Schrödinger Suite | Energetic mapping of binding sites | Hot spot identification, Interaction potential assessment |

| Docking Programs | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina, rDock, SMINA | Ligand binding pose prediction | Binding mode analysis, Virtual screening |

| Machine Learning Platforms | DrugTar, Custom TensorFlow/PyTorch implementations | Druggability classification, Pattern recognition | Target prioritization, Proteome-scale assessment |

| Specialized Libraries | Lead-like molecule sets, Fragment libraries | Reference compounds for computational screening | PocketVec descriptor generation, Pharmacophore modeling |

| Visualization Software | PyMOL, ChimeraX, VMD | Structural visualization and analysis | Result interpretation, Publication-quality graphics |

The comprehensive characterization of binding pockets and their molecular interaction capabilities provides the foundation for systematic druggability assessment in target-based drug discovery. Through integrated computational methodologies spanning geometric analysis, energetic mapping, and machine learning classification, researchers can now reliably identify and prioritize targets with the highest potential for successful therapeutic intervention. The ongoing development of advanced approaches including cryptic site detection, proteome-wide similarity mapping, and deep learning-based prediction continues to expand the boundaries of the druggable genome. As these methodologies mature and integrate with experimental validation frameworks, they promise to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and enhance the efficiency of drug discovery pipelines across diverse disease areas.

The fundamental objective of pharmaceutical research is to develop safe and effective medicines by understanding how drugs interact with complex biological macromolecules, including proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and nucleic acids [3]. Historically, "druggability" has been defined as a target's ability to be therapeutically modulated by traditional small molecules, primarily due to the relative ease of studying drug-protein interactions and predicting specificity and toxicity [3]. While the human genome contains approximately 21,000 protein-coding genes, estimates of likely druggable targets have ranged from 3,000 to 10,000 genes, with approximately 3,000 genes associated with diseases [3].

The pharmaceutical landscape is undergoing a transformative shift as novel therapeutic modalities emerge to address previously unmet medical needs [19]. Advances in molecular medicine have expanded treatment options to encompass genes and their RNA transcripts as well, moving beyond traditional small molecules to include biologics, gene therapies, and therapeutic oligonucleotides that affect gene expression post-transcription [3]. This expansion has fundamentally redefined the concept of druggability, enabling researchers to target previously "undruggable" pathways and proteins through innovative mechanisms of action.

The Evolving Therapeutic Modality Landscape

Market Shift from Small Molecules to Biologics and Novel Modalities

The global pharmaceutical market has demonstrated a significant shift from dominance by small molecules toward biologics and novel modalities. The market was valued at $828 billion in 2018, split 69% small molecules and 31% biologics [20]. By 2023, it had grown to $1,344 billion with small molecules at 58% and biologics at 42% [20]. Biologics sales are growing three times faster than small molecules, with some analysts predicting biologics will outstrip small molecule sales by 2027 [20].

This trend is reflected in research and development spending. Total global pharmaceutical R&D spending has increased from approximately $140 billion in 2014 to over $250 billion in 2024 [20]. During this period, small molecules' share of the R&D budget declined from 55-60% in 2014-16 to 40-45% by 2024, with a corresponding growth in biologics R&D [20].

New drug approvals further demonstrate this shift. Based on FDA CDER numbers, small molecules continue to dominate new novel molecular entity approvals but show a gradual decline from 79% (38/49) in 2019 to 62% (31/50) in 2024 [20]. According to BCG's 2025 analysis, new modalities now account for $197 billion, representing 60% of the total pharma projected pipeline value, up from 57% in 2024 [21]. This growth far outpaces conventional modalities, with projected new-modality pipeline value rising 17% from 2024 to 2025 [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Small Molecules vs. Biologics

| Characteristic | Small Molecule Drugs | Biologic Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Development Cost | 25-40% less expensive than biologics | Estimated $2.6-2.8B per approved drug |

| Manufacturing | Chemical synthesis: faster, cheaper, reproducible | Living cell production: expensive facilities, batch variability concerns |

| Storage & Shelf Life | Stability at room temperature | Often require refrigeration, shorter shelf lives |

| User Cost | Lower cost due to generics after patent expiry | Often 10x more expensive than small molecules |

| Delivery | Mostly oral administration (pills/tablets) | Mostly IV or subcutaneous injection |

| Dosing Intervals | Shorter half-life often requires multiple daily doses | Longer half-life allows less frequent administration (e.g., every 2-4 weeks) |

| Specificity & Efficacy | Less specific targeting, more off-target effects | Highly specific, fewer off-target effects |

| Therapeutic Range | Broad applicability across disease types | Especially effective for autoimmune diseases, cancer, rare genetic conditions |

| Market Exclusivity | 5 years before generics can enter | 12 years before biosimilars can enter |

| Additional Challenges | Rapid metabolism; development of resistance | Risk of immune response triggering neutralizing antibodies |

Classification Frameworks for Emerging Modalities

Several classification frameworks have been proposed to organize the growing diversity of therapeutic modalities. Laurel Oldach broadly grouped new modalities into small molecules (including inhibitors and degraders) and biologics (including antibodies, RNA therapeutics, and cell or gene therapies) [22]. Valeur et al. categorized emerging modalities by their mechanisms of action into groups such as protein-protein interaction (PPI) stabilization, protein degradation, RNA downregulation/upregulation, and multivalent/hybrid strategies [22].

Blanco and Gardinier proposed a dual framework: one classifying modalities by chemical structure and mechanism of action, and another aligning them with specific biological use cases [22]. Meanwhile, Liu and Ciulli offered a functional classification of proximity-based modalities, organizing them by therapeutic goals such as degradation, inhibition, stabilization, and post-translational modification, further distinguishing them by structural complexity (monomeric, bifunctional, multifunctional) [22].

Table 2: Emerging Modality Classes and Their Characteristics

| Modality Class | Key Examples | Primary Mechanisms | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | mAbs, ADCs, BsAbs | Target binding, payload delivery | Oncology, immunology, expanding to neurology, rare diseases [21] |

| Proteins & Peptides | GLP-1 agonists, recombinant proteins | Receptor activation, enzyme replacement | Metabolic diseases, rare disorders [21] |

| Cell Therapies | CAR-T, TCR-T, TIL, CAR-NK | Engineered cellular activity | Hematological cancers, solid tumors [21] |

| Nucleic Acids | DNA/RNA therapies, RNAi, mRNA | Gene expression modulation | Genetic disorders, infectious diseases, metabolic conditions [21] |

| Gene Therapies | Gene augmentation, gene editing | Gene replacement, correction | Rare genetic diseases, hematological disorders [21] |

| Targeted Protein Degradation | PROTACs, molecular glues | Protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system | Previously "undruggable" targets [22] |

Figure 1: Classification of Therapeutic Modalities. This diagram illustrates the expanding landscape of drug modalities, from traditional small molecules to complex biologics and novel therapeutic approaches.

Modality-Specific Advances and Clinical Impact

Established Modalities Showing Continued Innovation

Antibodies remain a cornerstone of biologic therapeutics, with continuous innovation expanding their applications. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) continue to demonstrate robust growth, with the clinical pipeline expanding beyond oncology and immunology into neurology, rare diseases, gastroenterology, and cardiovascular diseases [21]. Apitegromab (Scholar Rock), a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy currently under priority FDA review, has the highest revenue forecast of any mAb in development outside of oncology and immunology [21].

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have seen remarkable growth, with expected pipeline value increasing 40% during the past year and 22% CAGR over the past five years [21]. This trajectory can be attributed to approvals of products like Datroway (AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo) for breast cancer, which has the highest peak sales forecast of ADCs approved in the past year [21]. In 2025 alone, the FDA's CDER has approved two ADCs: AbbVie's Emrelis for non-small cell lung cancer and AstraZeneca's/Daiichi Sankyo's Datroway for breast cancer [23].

Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) have seen forecasted pipeline revenue rise 50% in the past year [21]. This growth is driven by a strong pipeline of products such as ivonescimab (Akeso and Summit) as well as commercialized therapies that have received expanded FDA approvals, like Rybrevant (Johnson & Johnson and Genmab) [21]. CD3 T-cell engagers are the BsAbs with the most clinically validated mechanism of action, used in seven of the top ten BsAbs as ranked by forecasted 2030 revenue [21].

Emerging Modalities with Transformative Potential

Cell therapies represent a rapidly evolving field with mixed results across different approaches. CAR-T therapy continues to have its greatest patient impact and market value in hematology, while results in solid tumors and autoimmune diseases have been mixed [21]. Multiple companies are now pursuing in vivo CAR-T, which could overcome the logistical challenges of traditional CAR-T therapies [21]. Beyond CAR-T, other cell therapies have shown some clinical progress but face adoption challenges. In 2024, Tecelra (Adaptimmune) became the first T-cell receptor therapy (TCR-T) to receive approval for treating synovial sarcoma, though adoption has been limited [21]. The pipeline for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) has grown over the past few years, with Amtagvi (Iovance), approved in 2024, forecasted to be a blockbuster [21].

Nucleic acid therapies are experiencing diverse growth patterns. DNA and RNA therapies have been one of the fastest-growing modalities over the past year, with projected revenue up 65% year-over-year, driven primarily by recently approved antisense oligonucleotides such as Rytelo (Geron), Izervay (Astellas), and Tryngolza (Ionis) [21]. RNAi therapies remain on a steady upward path, with approvals including Amvuttra (Alnylam) for cardiomyopathy and Qfitlia (Sanofi) for hemophilia A and B fueling a 27% increase in pipeline value during the past year [21]. In contrast, mRNA continues to decline significantly as the pandemic wanes [21].