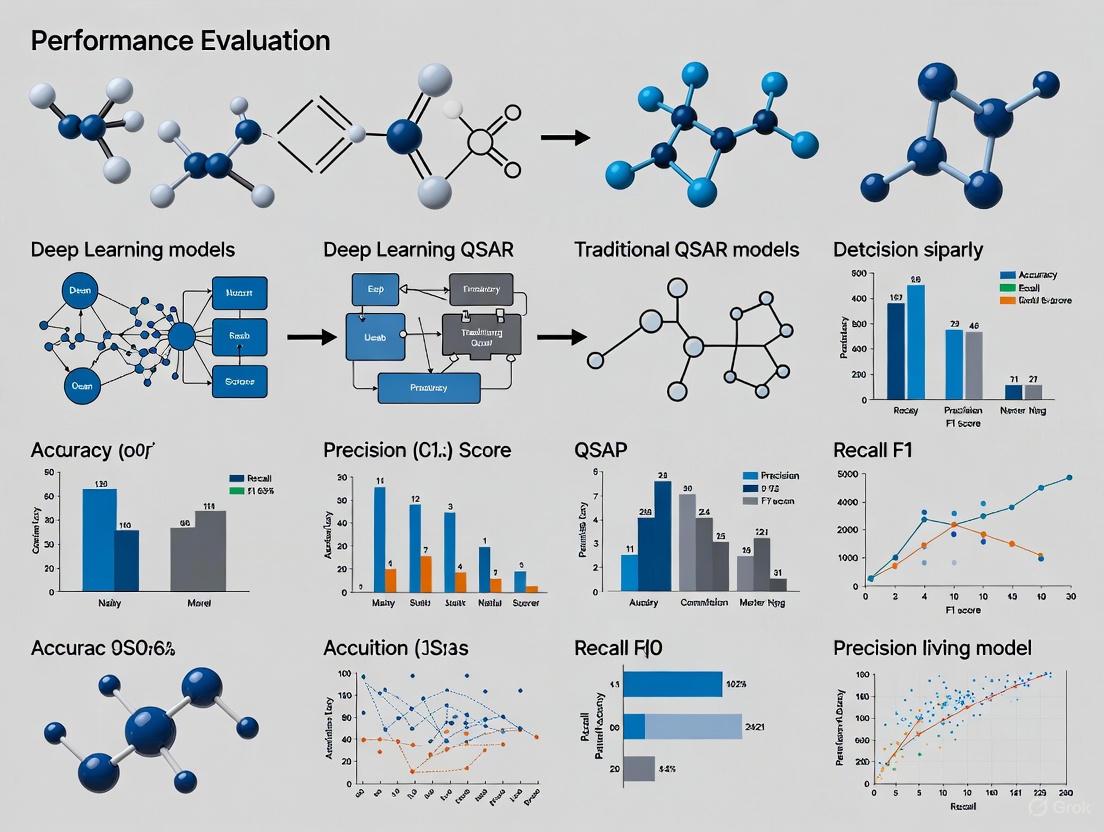

Deep Learning vs. Traditional QSAR: A Performance Evaluation for Modern Drug Discovery

The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning (DL), is revolutionizing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling in drug discovery.

Deep Learning vs. Traditional QSAR: A Performance Evaluation for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning (DL), is revolutionizing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of DL versus traditional QSAR methods, targeting researchers and development professionals. We explore the foundational shift from classical statistical models to advanced neural networks, detail methodological implementations across potency and ADMET prediction, and address critical troubleshooting aspects like data requirements and model interpretability. Through rigorous validation and comparative analysis, we synthesize evidence on the superior predictive power of DL in specific contexts while outlining a practical framework for selecting and optimizing QSAR strategies to accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

From Classical Equations to AI: The Evolution of QSAR Modeling

In the era of artificial intelligence and deep learning, classical Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling remains a foundational methodology in drug discovery and chemical risk assessment. These models operate on the fundamental principle that a chemical's biological activity can be correlated with its molecular structure through quantitative mathematical relationships [1] [2]. While modern machine learning approaches offer advanced pattern recognition capabilities, classical methods including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Principal Component Regression (PCR) provide unparalleled interpretability, statistical rigor, and well-established validation frameworks [3] [4]. This guide objectively examines the theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications of these classical workhorses, providing researchers with a clear understanding of their appropriate implementation within contemporary computational pipelines that increasingly integrate both classical and machine learning approaches.

Theoretical Foundations of Classical QSAR Methods

Core Mathematical Principles

Classical QSAR methodologies establish a quantitative link between molecular descriptors (independent variables) and biological activity (dependent variable) through linear model frameworks [4] [5]. The fundamental relationship can be expressed as:

Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃, ...)

Where D₁, D₂, D₃, etc. are molecular descriptors that numerically encode structural, physicochemical, or electronic properties of molecules [4]. These models aim to identify a mathematical function (typically linear) that best describes this relationship, enabling prediction of biological activities for new compounds based solely on their structural descriptors [1].

The molecular descriptors employed in these models span multiple dimensions: constitutional descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, atom counts), topological descriptors (encoding molecular connectivity), geometric descriptors (molecular shape and size), electronic descriptors (e.g., HOMO-LUMO energies, dipole moment), and thermodynamic descriptors [1] [6]. Proper selection and interpretation of these descriptors are critical for developing robust, predictive models [3].

The Classical QSAR Workflow

The development of reliable classical QSAR models follows a systematic workflow with distinct stages [4]:

- Data Compilation and Curation: Assembling a high-quality dataset of chemical structures with associated biological activities from reliable sources [1].

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating molecular descriptors using software tools such as DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor, or RDKit [1] [3].

- Feature Selection: Identifying the most relevant descriptors using statistical techniques to reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting [1] [5].

- Model Construction: Applying MLR, PLS, or PCR algorithms to establish the mathematical relationship between selected descriptors and biological activity [4] [5].

- Model Validation: Rigorously assessing model performance using internal and external validation techniques to ensure predictive reliability and robustness [1] [4].

The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the key decision points for method selection:

Methodological Deep Dive: MLR, PLS, and PCR

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

MLR represents the most straightforward classical approach, constructing a linear equation that directly relates molecular descriptors to biological activity [4]. The model takes the form:

Activity = b₀ + b₁D₁ + b₂D₂ + ... + bₙDₙ + ε

Where b₀ is the intercept, b₁...bₙ are regression coefficients for each descriptor, and ε represents the error term [4]. MLR's key advantage lies in its high interpretability—the magnitude and sign of each coefficient provide direct insight into how specific structural features enhance or diminish biological activity [4]. However, MLR requires careful variable selection and performs poorly with correlated descriptors, as it assumes descriptor independence [5].

Partial Least Squares (PLS)

PLS regression was developed to handle data with many correlated predictor variables, a common scenario in QSAR where molecular descriptors often exhibit significant collinearity [5]. Unlike MLR, PLS does not use the original descriptors directly but projects them onto a new set of latent variables (components) that maximize covariance with the response variable [5]. This approach allows PLS to efficiently handle datasets where the number of descriptors exceeds the number of compounds and effectively manage intercorrelated descriptors [5]. The method is particularly valuable when the underlying structural factors influencing activity are complex and distributed across multiple correlated molecular properties.

Principal Component Regression (PCR)

PCR addresses multicollinearity problems through a two-step process: first applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to transform the original descriptors into a set of uncorrelated principal components, then using these components as predictors in a regression model [7]. While similar to PLS in using latent variables, PCR's component selection focuses solely on explaining variance in the descriptor matrix without considering the response variable [5]. Recent studies on acylshikonin derivatives have demonstrated PCR's strong predictive capability, with one model achieving R² = 0.912 and RMSE = 0.119 in predicting antitumor activity [7].

Performance Comparison: Classical Methods vs. Modern Approaches

Predictive Performance Benchmarking

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for classical and modern machine learning methods across various studies and datasets, highlighting their relative strengths and limitations:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches

| Method | Performance Metrics | Training Set Size | Application Context | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | R²training: 0.93, R²test: ~0 [8] | 303 compounds | TNBC inhibitors [8] | High false-positive rate with limited data; prone to overfitting |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | R²: ~0.65 [8] | 6069 compounds | TNBC inhibitors [8] | Moderate performance; handles collinearity better than MLR |

| Principal Component Regression (PCR) | R²: 0.912, RMSE: 0.119 [7] | 24 derivatives | Acylshikonin antitumor activity [7] | Strong predictive performance with optimal descriptors |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Superior reliability vs. MLR [4] | 121 compounds | NF-κB inhibitors [4] | Better captures non-linear relationships |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | R²: 0.94 [8] | 303 compounds | TNBC inhibitors [8] | Sustained performance with small training sets |

| Random Forest (RF) | R²: 0.84 [8] | 303 compounds | TNBC inhibitors [8] | Robust with small datasets but lower than DNN |

Operational Characteristics Comparison

Beyond raw predictive performance, operational characteristics determine the appropriate application context for each method:

Table 2: Operational Characteristics of QSAR Modeling Techniques

| Characteristic | MLR | PLS | PCR | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Handling Correlated Descriptors | Poor | Excellent | Excellent | Good |

| Data Efficiency | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Variable |

| Training Speed | Fast | Fast | Fast | Slow |

| Overfitting Risk | High (without careful variable selection) | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Non-linearity Handling | None | Limited | Limited | Excellent |

Experimental Protocols for Classical QSAR Modeling

Standardized Model Development Protocol

To ensure reproducible and robust classical QSAR models, researchers should follow this detailed experimental protocol:

Dataset Preparation: Curate a minimum of 20-30 compounds with comparable activity values measured under standardized experimental conditions [4]. Divide compounds into training (typically 70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) using algorithms like Kennard-Stone to ensure representative chemical space coverage [1].

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing: Calculate molecular descriptors using established software (Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit) [1] [3]. Apply descriptor filtering to remove constant or near-constant variables. Standardize descriptors to zero mean and unit variance to prevent dominance by numerically large descriptors [1].

Variable Selection: Apply feature selection techniques (genetic algorithms, stepwise regression, or filter methods based on correlation) to identify the most relevant descriptors [1] [5]. The optimal descriptor number depends on dataset size but should maintain a minimum compound-to-descriptor ratio of 5:1 [4].

Model Training and Optimization: For MLR, use ordinary least squares estimation with significance testing of coefficients (p < 0.05) [4]. For PLS/PCR, determine optimal component number through cross-validation to maximize Q² (cross-validated R²) while minimizing overfitting [5].

Model Validation: Employ both internal validation (leave-one-out or k-fold cross-validation) and external validation (hold-out test set) [1] [4]. Calculate Q² for internal validation and R²pred for external validation, with acceptable thresholds >0.6 and >0.5, respectively [8] [4].

Case Study: NF-κB Inhibitor Modeling

A recent study on 121 NF-κB inhibitors provides a practical example of classical QSAR implementation [4]. Researchers compared MLR and ANN models using topological, constitutional, and quantum chemical descriptors. The MLR model identified statistically significant descriptors through ANOVA, while the ANN model ([8-11-11-1] architecture) demonstrated superior predictive performance despite similar computational requirements [4]. Both models underwent rigorous validation using the leverage method to define applicability domains, enabling reliable prediction of new compound activities within the defined chemical space [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Classical QSAR Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit | Generate molecular descriptors from chemical structures | PaDEL-Descriptor is free and open-source; Dragon provides extensive descriptor libraries |

| Statistical Analysis | R, scikit-learn, MATLAB | Implement MLR, PLS, PCR algorithms | R offers specialized packages (pls, chemometrics) for multivariate analysis [5] |

| Molecular Modeling | ChemBioOffice, Gaussian | Structure optimization and electronic descriptor calculation | Gaussian calculates quantum chemical descriptors (HOMO-LUMO, dipole moment) [6] |

| Variable Selection | Stepwise regression, Genetic Algorithms | Identify optimal descriptor subsets | Critical for MLR to avoid overfitting; less critical for PLS/PCR |

| Model Validation | QSARINS, in-house scripts | Internal and external validation | QSARINS provides comprehensive validation metrics and applicability domain assessment |

Classical QSAR methods remain indispensable tools in computational chemistry and drug discovery, offering distinct advantages in interpretability, computational efficiency, and regulatory acceptance. MLR provides transparent structure-activity relationships when appropriate descriptor selection is possible, while PLS and PCR offer robust solutions for high-dimensional, correlated data. The performance data clearly indicates that classical methods maintain competitiveness for many QSAR applications, particularly with well-behaved datasets and linear structure-activity relationships.

However, the comparative evidence also shows that modern machine learning approaches, particularly DNNs and Random Forests, can achieve superior predictive performance, especially with complex, nonlinear relationships and limited training data [8]. The optimal approach frequently involves strategic integration—using classical methods for initial exploratory analysis and model interpretability, while leveraging machine learning for final predictive accuracy. This hybrid methodology capitalizes on the respective strengths of both paradigms, positioning classical MLR, PLS, and PCR as enduring pillars within the increasingly diverse QSAR methodological landscape.

The field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling stands at a significant inflection point, where researchers must choose between established traditional machine learning algorithms and emerging deep learning approaches. For drug development professionals navigating this complex landscape, the selection of an appropriate algorithm can dramatically impact project timelines, computational resource allocation, and ultimately, the success of candidate identification. This guide provides an objective performance comparison of three fundamental traditional machine learning (ML) algorithms—Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN)—within the context of modern QSAR research. As deep learning demonstrates remarkable success across various domains, previous comparative benchmarks have revealed a crucial insight: deep learning models frequently do not outperform traditional methods on structured tabular data, which forms the backbone of QSAR datasets [9]. This makes understanding the precise strengths and weaknesses of RF, SVM, and k-NN more critical than ever for researchers designing efficient and effective drug discovery pipelines.

Algorithmic Foundations and Mechanisms

Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest operates as an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training. The algorithm employs bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) to create several subsets of the original data, building a decision tree for each subset. For classification tasks, the final output is determined by majority voting across all trees, while regression tasks use averaging. This ensemble approach gives RF its notable robustness against overfitting, even with high-dimensional data [8]. The algorithm's built-in feature importance calculation provides valuable interpretability, revealing which molecular descriptors most significantly influence bioactivity predictions—a crucial advantage in medicinal chemistry applications.

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

SVM functions by identifying an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between different classes in a high-dimensional feature space. Through the use of kernel functions (linear, polynomial, or radial basis function), SVM can efficiently handle non-linear relationships by transforming data into higher dimensions without explicit computational overhead. This maximum-margin principle makes SVM particularly effective for datasets with clear separation boundaries, though its performance can be sensitive to parameter tuning and kernel selection [10] [11]. In cheminformatics, SVM has proven valuable for classifying compounds based on their structural features and predicting activity profiles.

k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN)

As a non-parametric, instance-based learning algorithm, k-NN classifies data points based on the majority class among their k-nearest neighbors in the feature space. The algorithm relies critically on distance metrics (Euclidean, Manhattan, or Minkowski) to determine proximity between data points [12]. k-NN's simplicity and adaptability make it suitable for various pattern recognition tasks, though its computational efficiency decreases with dataset size as it requires storing the entire training dataset and calculating distances for each new prediction [13]. Recent advancements have introduced confidence-aware k-NN approaches that perform two-layered neighborhood analysis to provide more reliable class probabilities, enhancing its applicability to biomedical data [13].

Figure 1: Core algorithmic workflows of RF, SVM, and k-NN classifiers

Performance Benchmarking in Scientific Applications

Comparative Performance in Classification Tasks

Table 1: Performance comparison across diverse classification domains

| Application Domain | Best Performing Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Activity Recognition [10] | k-NN | 97.08 | 95.2 | 94.9 | 94.9 | 102 subjects, 12 activities, sensor data |

| Brain Tumor Detection [14] | RF (vs. SVM+HOG) | 99.77 (vs. 96.51) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2870 MRI images, 4 classes |

| Virtual Screening (QSAR) [8] | RF & DNN | ~90 (R²) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7130 molecules, 613 descriptors |

| General Classification [11] | RF | Highest | N/A | N/A | N/A | Multiple datasets |

| Biomedical Data [13] | Enhanced k-NN | Improved | N/A | N/A | N/A | Clinical EHR data |

Robustness and Cross-Domain Generalization

Table 2: Cross-domain generalization performance [14]

| Algorithm | Within-Domain Accuracy (%) | Cross-Domain Accuracy (%) | Performance Drop | Training Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet18 (DL) | 99 | 95 | 4% | Moderate |

| Random Forest | 97 | 80 | 17% | High |

| SVM + HOG | 97 | 80 | 17% | High |

| ViT-B/16 (DL) | 98 | 93 | 5% | Low |

| SimCLR (SSL) | 97 | 91 | 6% | Moderate |

Recent benchmark studies highlight the nuanced performance landscape of traditional ML versus deep learning approaches. In brain tumor classification from medical images, ResNet18 (a deep learning model) achieved superior accuracy (99.77%) and demonstrated stronger cross-domain generalization (95% vs. 80% for traditional methods) [14]. However, this performance advantage comes with increased computational complexity and data requirements. For traditional ML algorithms, Random Forest consistently emerges as a robust performer, particularly on structured data. In human activity recognition based on sensor data, k-NN achieved marginally higher accuracy (97.08%) compared to SVM (95.88%), though SVM offered faster processing times [10]. These findings underscore the critical context-dependency of algorithm performance.

Experimental Protocols in QSAR Research

Standard QSAR Modeling Workflow

The development of robust QSAR models follows a systematic experimental protocol that begins with data acquisition and curation. For PfDHODH inhibitor studies, researchers typically extract IC₅₀ values from reliable databases such as ChEMBL, followed by rigorous curation to ensure data quality [15]. The subsequent steps involve:

Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Generation of chemical fingerprints and molecular descriptors using tools like DRAGON, PaDEL, or RDKit to numerically represent structural and physicochemical properties [3]. Common descriptors include extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs), functional-class fingerprints (FCFPs), and topological indices.

Dataset Partitioning: Splitting the data into training (model development), validation (hyperparameter tuning), and test (final evaluation) sets, typically using 70-30 or 80-20 ratios with appropriate stratification [16].

Model Training with Cross-Validation: Implementing k-fold cross-validation (commonly 5 or 10 folds) on the training set to optimize model hyperparameters and assess robustness while mitigating overfitting [15].

External Validation: Evaluating the final model on a completely held-out test set to estimate real-world performance and generalizability [8].

Handling Class Imbalance

In real-world QSAR applications, datasets often exhibit significant class imbalance, which can severely impact model performance. Researchers employ various strategies to address this challenge, including undersampling majority classes, oversampling minority classes using techniques like SMOTE, or utilizing algorithmic approaches that incorporate class weights [15]. Studies on PfDHODH inhibitors demonstrated that balanced oversampling techniques yielded optimal results, with Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) values exceeding 0.65 in cross-validation and external test sets [15].

Figure 2: Standard QSAR modeling workflow with iterative refinement

Table 3: Essential resources for ML-based QSAR research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem | Source of bioactivity data & compound structures | Provide experimental IC₅₀ values & structural information for model training [8] [15] |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit, PaDEL, DRAGON | Generate molecular fingerprints & physicochemical descriptors | Convert chemical structures into numerical representations for ML algorithms [3] |

| ML Frameworks | scikit-learn, KNIME | Implement classification & regression algorithms | Provide optimized implementations of RF, SVM, k-NN with hyperparameter tuning [3] |

| Model Validation | QSARINS, Build QSAR | Statistical validation & model robustness assessment | Calculate R², Q², MCC metrics & perform y-randomization tests [3] |

| Cloud Platforms | Google Colab, AWS SageMaker | Computational resources for training | Enable resource-intensive operations like deep learning & large-scale virtual screening [3] |

Critical Analysis: When Does Each Algorithm Excel?

Dataset Characteristics Driving Algorithm Selection

The performance differentiation between RF, SVM, and k-NN becomes particularly evident when examining their response to specific dataset characteristics:

Random Forest demonstrates superior performance with high-dimensional data containing numerous molecular descriptors, showing remarkable resistance to overfitting even when descriptor count exceeds compound count [3]. Its built-in feature importance ranking provides medicinal chemists with valuable insights into which structural features correlate with bioactivity, enabling rational compound optimization [15]. However, studies note RF's tendency to achieve near-perfect training AUC (0.999) while test performance plateaus around 0.80, indicating the need for careful regularization [16].

Support Vector Machine excels in scenarios with clear margin separation and moderate dataset sizes, particularly when using appropriate kernel functions that map descriptors to higher-dimensional spaces where activity separation becomes possible [11]. SVM's maximum-margin principle makes it less susceptible to overfitting in high-dimensional spaces, though its performance heavily depends on proper kernel and parameter selection [10].

k-Nearest Neighbors performs optimally with low-dimensional data where distance metrics meaningfully capture compound similarity, and when dataset size remains computationally manageable [12] [13]. Recent advancements in confidence-aware k-NN have improved its applicability to biomedical data through two-layered neighborhood analysis that provides more reliable probability estimates [13]. However, k-NN's performance deteriorates significantly with high-dimensional data due to the "curse of dimensionality" where distance metrics lose semantic meaning [12].

Computational Efficiency Considerations

Beyond raw predictive performance, computational efficiency presents another critical differentiator. In human activity recognition applications, SVM models demonstrated faster processing times compared to k-NN models, despite k-NN achieving marginally higher accuracy (97.08% vs. 95.88%) [10]. Random Forest's training process can be computationally intensive due to the construction of multiple trees, though prediction remains fast once trained. For large-scale virtual screening of compound libraries containing hundreds of thousands of compounds, these efficiency considerations directly impact project feasibility and resource allocation.

The current inflection point in QSAR research demands strategic algorithm selection based on comprehensive performance understanding. While deep learning approaches demonstrate impressive capabilities in specific domains, traditional machine learning algorithms—particularly Random Forest, SVM, and k-NN—maintain significant advantages for many QSAR applications, especially with structured tabular data and limited dataset sizes. Random Forest emerges as the most consistently performing algorithm across diverse QSAR tasks, offering robust predictive accuracy and valuable feature interpretability. SVM provides competitive performance with greater computational efficiency for appropriately scaled problems, while k-NN remains relevant for specific applications with strong local similarity relationships and lower-dimensional data. The optimal algorithm selection ultimately depends on specific project requirements including dataset characteristics, computational resources, interpretability needs, and performance priorities—reinforcing the continued importance of these established algorithms in the modern drug discovery toolkit.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has served as a cornerstone computational method in drug discovery for decades, traditionally relying on predefined molecular descriptors and linear statistical models to correlate chemical structure with biological activity [17] [18]. This approach operates on the fundamental principle that similar structures exhibit similar biological activities, with early QSAR methodologies pioneered by Hansch in the 1960s utilizing physicochemical parameters like lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects to predict molecular behavior [17]. The traditional QSAR pipeline follows a sequential process: expert-driven descriptor selection, mathematical model development, and activity prediction based on these hand-crafted features [19].

The emergence of deep learning (DL), a branch of artificial intelligence based on artificial neural networks with multiple hidden layers, represents a paradigm shift in computational molecular design [20] [21]. Unlike traditional QSAR that depends on human-engineered descriptors, deep neural networks (DNNs) autonomously learn relevant features directly from raw molecular representations, enabling identification of complex, non-linear structure-activity relationships that often elude conventional methods [8] [20]. This "self-taught" capability allows DL models to discover hierarchical feature representations without explicit human guidance, potentially transforming virtual screening and drug discovery efficiency [8] [21]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison between these evolving methodologies, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and implications for modern drug development.

Performance Comparison: Deep Learning vs. Traditional QSAR

Predictive Accuracy and Data Efficiency

Table 1: Comparative Performance Across Machine Learning Methodologies

| Method | Training Set (n=6069) R² Pred | Training Set (n=303) R² Pred | Data Efficiency | Multi-Task Learning Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | ~0.90 [8] | 0.94 [8] | Excellent | Native support [22] |

| Random Forest (RF) | ~0.90 [8] | 0.84 [8] | Good | Limited |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | ~0.65 [8] | 0.24 [8] | Poor | Not supported |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | ~0.65 [8] | 0.00 [8] | Very Poor | Not supported |

Direct comparative studies demonstrate the superior predictive performance of deep learning approaches over traditional QSAR methods, particularly as training data volume decreases [8]. In one comprehensive analysis using 7,130 molecules with MDA-MB-231 inhibitory activities from ChEMBL, DNNs and Random Forest both achieved R² values approximating 0.90 with large training sets (n=6,069). However, with a substantially reduced training set (n=303), DNNs maintained a high R² value of 0.94, significantly outperforming Random Forest (0.84) and completely eclipsing traditional QSAR methods like Partial Least Squares (0.24) and Multiple Linear Regression (0.00) [8]. This data efficiency is particularly valuable in drug discovery contexts where experimental activity data is often limited.

The performance advantages of deep learning extend beyond standard QSAR benchmarks to complex toxicity prediction challenges. In the Tox21 Challenge, which assesses compound toxicity across 12 different targets, deep learning with multitask learning slightly outperformed all other computational methods across nuclear receptor and stress response datasets [21]. This superior performance stems from the innate ability of DNNs to leverage related information across multiple endpoints simultaneously, a capability generally lacking in traditional single-task QSAR models [22].

Application-Specific Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Across Diverse Pharmaceutical Endpoints

| Dataset/Endpoint | Best Performing Method | Key Metric | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Deep Learning [21] | Favorable comparison to other ML | Handles non-linear relationships |

| hERG Inhibition | Deep Neural Networks [21] | Higher ranking across multiple metrics | Reduced false positives |

| Tuberculosis (Mtb) | Deep Learning [21] | Superior AUC, F1 score, MCC | Enhanced virtual screening efficiency |

| Malaria (P. falciparum) | Deep Neural Networks [21] | Higher normalized score | Improved hit identification |

| KCNQ1 | DNN ranked highest [21] | Array of metrics (AUC, F1, Kappa) | Robust performance across validation measures |

Deep learning demonstrates consistently strong performance across diverse pharmaceutical endpoints, as evidenced by a systematic comparison study that evaluated eight distinct drug discovery datasets including solubility, hERG inhibition, KCNQ1, bubonic plague, Chagas disease, tuberculosis, and malaria [21]. When assessed using an array of metrics including Area Under the Curve (AUC), F1 score, Cohen's kappa, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Deep Neural Networks consistently ranked highest, followed by Support Vector Machines, with both outperforming methods like Naïve Bayes, Decision Trees, and Logistic Regression [21].

This cross-endpoint robustness highlights a key advantage of the deep learning paradigm: its ability to automatically learn relevant features from diverse molecular representations without requiring domain-specific descriptor engineering for each new target or endpoint [8] [21]. This flexibility translates to substantial practical benefits in pharmaceutical research and development settings where multiple therapeutic targets and ADME/Tox (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties must be evaluated simultaneously [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Deep Learning Workflow for Molecular Activity Prediction

The application of deep learning to molecular activity prediction follows a structured experimental pipeline that differs fundamentally from traditional QSAR approaches. A representative protocol for constructing DNN models for virtual screening, as implemented in comparative drug discovery studies, involves several key stages [8] [21]:

Compound Dataset Curation: Researchers first assemble a collection of chemical structures with corresponding experimental bioactivity measurements. In one TNBC (triple-negative breast cancer) inhibition study, 7,130 molecules with reported MDA-MB-231 inhibitory activities were collected from the ChEMBL database, then randomly divided into training (n=6,069) and test (n=1,061) sets to evaluate model performance [8]. Similar dataset preparation was employed for ADME/Tox properties and anti-infective screening, utilizing public repositories like PubChem and ChEMBL [21].

Molecular Representation: Unlike traditional QSAR that relies on pre-selected molecular descriptors, deep learning implementations typically use extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) or functional-class fingerprints (FCFPs) that encode molecular structures as fixed-length bit vectors [8] [21]. These circular topological fingerprints systematically record the neighborhood of each non-hydrogen atom into multiple circular layers up to a specified diameter, capturing local structural information that serves as input for the neural network [8]. In one comparative study, a total of 613 descriptors derived from AlogP_count, ECFP, and FCFP were used to generate models [8].

Network Architecture and Training: A typical deep neural network for QSAR comprises an input layer matching the descriptor dimensions, multiple hidden layers with non-linear activation functions (e.g., ReLU), and an output layer corresponding to the prediction task [23] [21]. The model is trained through empirical risk minimization, usually via gradient-based optimization methods like backpropagation, iteratively updating parameters to minimize the difference between predicted and actual activity values [23] [20]. Training requires careful regularization to prevent overfitting, with techniques like dropout and early stopping commonly employed [21].

Model Validation: Rigorous validation is essential and typically involves both internal cross-validation and external testing on held-out compounds not used during training [8] [21]. Performance metrics including R², AUC, F1 score, and others are calculated to assess predictive accuracy, with Y-scrambling or permutation tests often conducted to verify model robustness [21].

Traditional QSAR Modeling Protocol

Classical QSAR approaches follow a distinctly different workflow centered on expert-guided descriptor selection [19] [17]:

Descriptor Calculation: Researchers compute predefined molecular descriptors encoding structural, quantum chemical, and physicochemical properties [17]. These may include thousands of possible descriptors generated by software like Dragon, with subsequent feature selection to reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting [19].

Model Construction: Linear methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) or Partial Least Squares (PLS) establish quantitative relationships between selected descriptors and biological activity [8] [17]. The process emphasizes interpretability, with researchers seeking to identify chemically meaningful descriptors that provide mechanistic insights [19].

Validation and Applicability Domain: Traditional QSAR models undergo statistical validation including leave-one-out cross-validation and external test set prediction, with careful definition of the model's applicability domain to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable [19] [17].

Technical Workflows: Comparative Visualization

Deep Learning Workflow for QSAR

The deep learning workflow demonstrates the fundamental paradigm shift from descriptor engineering to feature learning. Molecular structures undergo initial representation as fingerprints, but the deep neural network autonomously discovers relevant hierarchical features through its hidden layers, enabling identification of complex structure-activity relationships without explicit human guidance [8] [20]. This self-taught capability allows the model to learn directly from data, progressively building more abstract representations through multiple processing layers [20] [21].

Traditional QSAR Workflow

The traditional QSAR workflow highlights the human-dependent nature of descriptor selection and engineering. This approach relies heavily on chemical intuition and domain expertise to identify meaningful molecular descriptors, which then feed into typically linear mathematical models [19] [17]. While offering interpretability, this methodology inherently limits the complexity of discoverable patterns and introduces potential expert bias into the modeling process [8] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Deep Learning in Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | ECFP, FCFP, AlogP [8] | Convert structures to numerical representations | Input for both DL and QSAR models |

| Software/Libraries | RDKit, TensorFlow, Keras, scikit-learn [21] | Implement machine learning algorithms | Model development and training |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, Tox21 [8] [21] [22] | Provide experimental training data | Model development and validation |

| Validation Metrics | R², AUC, F1 score, MCC [8] [21] | Quantify model performance | Method comparison and optimization |

| Specialized Techniques | Multi-task learning, Imputation models [22] | Enhance learning from sparse data | Addressing data limitations |

The experimental toolkit for modern QSAR research spans multiple categories essential for implementing both traditional and deep learning approaches. Molecular descriptors like Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) and Functional-Class Fingerprints (FCFPs) provide fundamental representations of chemical structures, transforming molecular features into numerical data suitable for computational analysis [8]. Software libraries including RDKit for cheminformatics and TensorFlow or scikit-learn for machine learning implementation form the computational backbone of modeling efforts [21].

Critical to model development are comprehensive bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL, PubChem, and Tox21, which supply the experimental activity data necessary for training and validating predictive models [8] [21] [22]. Robust validation metrics including R-squared (R²), Area Under the Curve (AUC), F1 score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) provide standardized measures for comparing model performance across different methodologies and datasets [8] [21]. Emerging specialized techniques like multi-task learning and imputation models represent advanced approaches for leveraging related information across multiple endpoints or filling gaps in sparse bioactivity matrices, particularly enhancing performance for compounds with limited experimental data [22].

The paradigm shift from traditional QSAR to deep learning represents more than a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how computational models extract meaningful patterns from chemical data. The comparative evidence demonstrates that deep learning approaches consistently match or exceed the performance of traditional QSAR methods across diverse pharmaceutical endpoints while offering superior data efficiency, particularly valuable in early discovery stages where experimental data is limited [8] [21].

The autonomous feature learning capability of deep neural networks addresses a core limitation of traditional QSAR: the dependency on human-engineered descriptors and linear modeling assumptions [8] [20] [17]. This advantage manifests most clearly in complex structure-activity relationships with strong non-linear characteristics, where deep learning's hierarchical representation learning captures patterns that elude conventional methods [21]. Furthermore, the native support for multi-task learning in deep neural networks enables more efficient knowledge transfer across related targets or endpoints, creating synergies that enhance prediction accuracy [22].

Despite these advantages, challenges remain in interpretability and implementation complexity [20] [24]. Traditional QSAR models often provide more straightforward chemical insights through examination of significant descriptors, whereas deep learning models can function as "black boxes" with limited inherent interpretability [20]. Ongoing research in explainable AI and model interpretability continues to address this limitation [24].

For drug development professionals and researchers, the practical implications are substantial. Deep learning approaches can increase virtual screening efficiency, improve hit identification rates, and reduce experimental resource requirements by more accurately prioritizing compounds for synthesis and testing [8] [18] [21]. As deep learning methodologies continue evolving alongside computational resources and chemical data availability, their role in drug discovery is poised to expand, potentially becoming the standard computational approach for molecular design and optimization across pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling stands as a cornerstone in modern drug discovery and chemical risk assessment, operating on the fundamental principle that molecular structure determines biological activity and physicochemical properties [17]. For decades, the success of QSAR has hinged on one critical step: the translation of chemical structures into numerical representations known as molecular descriptors. These descriptors, which encode everything from simple atom counts to complex three-dimensional electronic properties, serve as the input variables for statistical and machine learning models that predict biological activity, toxicity, and environmental fate of chemicals [25] [17]. The selection of appropriate descriptors has long been recognized as pivotal to developing predictive, interpretable, and robust QSAR models.

The landscape of molecular descriptors has evolved dramatically, from early physicochemical parameters like lipophilicity (log P) and electronic properties to thousands of computationally-derived descriptors encompassing topological, geometrical, and quantum-chemical features [17] [3]. Among these, molecular fingerprints—particularly the Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) and Functional Class Fingerprint (FCFP)—have emerged as powerful, widely-adopted tools for capturing substructural information in a mathematically compact form [26]. Their development represents a significant milestone in cheminformatics, offering a balance between computational efficiency and chemical relevance.

More recently, the field has witnessed the rise of descriptor-free models that leverage deep learning architectures to automatically learn relevant features directly from molecular representations such as SMILES strings or molecular graphs [27] [3]. This paradigm shift, fueled by advances in artificial intelligence and increased computational resources, challenges the traditional descriptor-based approach and promises to unlock new levels of predictive performance, particularly for complex endpoints with nonlinear structure-activity relationships. This review comprehensively compares these molecular representation strategies within the broader context of performance evaluation between deep learning and traditional QSAR research, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection in their molecular design and analysis workflows.

Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints: Fundamental Concepts

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that encode chemical information about a molecule's structure, composition, or properties. They can be categorized by the dimensionality of the structural information they capture: 1D descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, atom counts), 2D descriptors (topological indices based on molecular connectivity), 3D descriptors (geometrical and surface properties), and even 4D descriptors that account for conformational flexibility [3]. The primary utility of these descriptors lies in their ability to convert qualitative structural features into quantitative data that machine learning algorithms can process to establish structure-activity relationships.

Molecular fingerprints represent a special class of 2D descriptors that encode the presence or absence of specific structural patterns or features within a molecule. They are typically represented as bit vectors of fixed or variable length, where each bit indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of a particular structural feature. Fingerprints have gained widespread adoption in cheminformatics due to their computational efficiency and effectiveness in similarity searching, virtual screening, and QSAR modeling [26]. They can be broadly classified into several categories based on their generation algorithm:

- Path-based fingerprints (e.g., Atom Pair): Generate features by analyzing paths through the molecular graph between atom pairs.

- Circular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, FCFP): Capture circular atom environments around each atom by iteratively considering neighboring atoms up to a specified radius.

- Substructure-based fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys): Use predefined dictionaries of structural fragments where each bit corresponds to a specific substructure.

- Pharmacophore fingerprints (e.g., PH2, PH3): Encode potential pharmacophoric points and their relationships, focusing on interaction capabilities rather than exact structure.

- String-based fingerprints (e.g., LINGO, MHFP): Operate directly on SMILES strings by fragmenting them into substrings or using hashing techniques [26].

The choice of fingerprint type significantly impacts molecular similarity assessments and model performance, as different algorithms capture complementary aspects of molecular structure and function.

Traditional Workhorses: ECFP and FCFP Fingerprints

Technical Foundations and Algorithmic Differences

The Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) and Functional Class Fingerprint (FCFP) belong to the category of circular fingerprints, which are generated through an iterative process that captures circular atom environments within the molecular graph [26]. The ECFP algorithm begins by assigning initial identifiers to each non-hydrogen atom based on their atom features (atomic number, degree, connectivity, etc.). In each iteration, information from neighboring atoms is incorporated, updating each atom's identifier to represent its evolving circular environment. The radius parameter (typically 2 for ECFP4) determines the number of iterations, with each iteration extending the diameter of the captured environment by one bond. Unique identifiers generated throughout this process are then hashed into a fixed-length bit vector to create the final fingerprint [26].

The fundamental distinction between ECFP and FCFP lies in their atom typing schemes. While ECFP uses structure-based atom features (e.g., atomic number, bond orders), FCFP employs pharmacophore-based atom features that classify atoms according to their potential functional roles in molecular recognition, such as hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, acidic centers, basic centers, and hydrophobic regions [26]. This key difference means ECFP captures specific structural motifs, whereas FCFP encodes more abstract, functional patterns that may be shared by structurally diverse compounds with similar interaction capabilities.

Applications and Performance Characteristics

ECFP has established itself as the de facto standard for fingerprint-based QSAR modeling across diverse applications, from cardiotoxicity prediction to virtual screening [28] [8]. In cardiotoxicity modeling, ECFP features combined with machine learning classifiers have demonstrated stable performance for identifying hERG channel blockers, a major cause of drug-induced arrhythmias [28]. Similarly, in targeted therapeutic development, ECFP descriptors have been successfully employed in random forest and deep neural network models for predicting inhibitors of triple-negative breast cancer and GPCR agonists [8].

FCFP often outperforms ECFP in tasks where functional groups rather than specific structural motifs govern biological activity, such as scaffold hopping and cross-pharmacology modeling [26]. The pharmacophore-based encoding of FCFP makes it particularly valuable for identifying structurally distinct compounds that share interaction profiles, potentially revealing novel chemical series with desired activity but improved properties.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ECFP and FCFP Fingerprints

| Feature | ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint) | FCFP (Functional Class Fingerprint) |

|---|---|---|

| Atom Typing | Structure-based (atomic number, connectivity, etc.) | Pharmacophore-based (H-bond donor/acceptor, charged, hydrophobic, etc.) |

| Information Captured | Specific structural motifs and substructures | Abstract functional patterns and interaction capabilities |

| Primary Strengths | Excellent for structurally congeneric series; widely validated | Superior for scaffold hopping and functional similarity |

| Typical Applications | Lead optimization, toxicity prediction, QSAR modeling | Virtual screening, cross-pharmacology, motif discovery |

| Performance Considerations | Stable performance across diverse problems [28] | Better for identifying functionally similar but structurally diverse compounds [26] |

The Deep Learning Revolution: Descriptor-Free Models

Paradigm Shift in Molecular Representation

Descriptor-free modeling represents a fundamental departure from traditional QSAR approaches by eliminating the need for pre-defined molecular descriptors. Instead, these methods use deep learning architectures to automatically learn relevant feature representations directly from raw molecular inputs, such as SMILES strings or molecular graphs [27] [3]. This end-to-end learning paradigm allows models to discover complex, hierarchical representations that may be more optimally tuned to the specific prediction task than hand-crafted descriptors.

Two primary architectural approaches have emerged in descriptor-free QSAR modeling. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and related recurrent neural networks process SMILES strings as sequences of characters, learning representations that capture syntactic and semantic patterns in the linear notation [27]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and their variants, such as Graph Transformers, operate directly on molecular graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, enabling native processing of the non-linear molecular topology [28] [3]. This graph-based approach more naturally aligns with chemical intuition and has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across multiple benchmarks.

Key Architectures and Performance Advantages

SMILES-Based LSTMs: Pioneering work on descriptor-free QSAR demonstrated that LSTM networks trained directly on SMILES strings could achieve prediction accuracies comparable to traditional descriptor-based models for endpoints including Ames mutagenicity, hepatitis C virus inhibition, and Plasmodium falciparum inhibition [27]. A critical innovation in these models is the incorporation of attention mechanisms, which help identify which parts of the SMILES string contribute most to the prediction, thereby enhancing interpretability and enabling the detection of structural alerts [27].

Graph Neural Networks: GNNs have shown remarkable performance in molecular property prediction due to their ability to natively represent molecular structure and learn hierarchical features. For cardiotoxicity prediction, graph transformer models with substructure-aware bias have achieved impressive performance (90.4% precision, 90.4% recall, 90.5% F1-score) in identifying hERG blockers, surpassing traditional fingerprint-based approaches [28]. The key advantage of GNNs lies in their high flexibility in feature extraction and decision rule generation, which allows them to capture complex structure-activity relationships that may be challenging for fixed fingerprints [28].

Hybrid and Specialized Architectures: Recent innovations include graph subgraph transformer networks that improve model expressiveness by introducing substructure-aware bias, helping to address the activity cliff problem where small structural changes lead to large potency differences [28]. Self-supervised pre-training on large unlabeled molecular datasets has further enhanced the performance of these models by enabling them to learn general chemical principles before fine-tuning on specific prediction tasks.

Comparative Analysis: Performance Evaluation Across Methodologies

Experimental Design for Method Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide valuable insights into the relative performance of descriptor-based and descriptor-free approaches under controlled conditions. A comprehensive evaluation of molecular fingerprints for exploring the chemical space of natural products analyzed 20 different fingerprinting algorithms from four packages on over 100,000 unique natural products [26]. The study evaluated fingerprints on both unsupervised similarity searches and supervised QSAR modeling tasks using 12 bioactivity prediction datasets from the Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD). Performance was assessed using standard classification metrics and similarity comparison techniques [26].

In comparative studies between deep learning and QSAR methods, researchers have systematically evaluated models using the same data splits and evaluation metrics. One such study used a database of 7,130 molecules with reported MDA-MB-231 inhibitory activities, splitting them into training (6,069 compounds) and test (1,061 compounds) sets [8]. The researchers implemented ECFP and FCFP as major molecular descriptors for traditional models, while DNN architectures used the same descriptor sets or raw molecular inputs. Performance was quantified using R² values for both training and test sets, with careful attention to avoiding overfitting, especially with smaller training sets [8].

Quantitative Performance Results

Table 2: Performance Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Training Set Size | Test Set R² (Prediction Accuracy) | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP/Random Forest | 6,069 compounds | ~0.90 (R²) [8] | High robustness, built-in feature selection, handles noisy data | Limited expressiveness for complex nonlinear relationships |

| FCFP/Random Forest | Varies by application | Competitive with ECFP, superior for functional similarity tasks [26] | Better capture of pharmacophore features | May miss specific structural motifs |

| DNN with Descriptors | 6,069 compounds | ~0.90 (R²) [8] | Automatic feature weighting, high capacity for complex patterns | Computationally intensive, requires careful regularization |

| DNN (Descriptor-Free) | 7,866-31,919 compounds [27] | Close to fragment-based models, superior for dissimilar compounds [27] | No descriptor engineering needed, learns task-specific features | "Black box" nature, limited interpretability without attention mechanisms |

| Graph Neural Networks | Varies by application | 90.5% F1-score for cardiotoxicity [28] | Native graph processing, substructure-aware learning | High computational requirements, complex implementation |

Critical Analysis of Performance Trade-offs

The comparative evidence reveals several important patterns. First, machine learning methods (both DNN and RF) generally outperform traditional QSAR methods (PLS and MLR) particularly as dataset size and complexity increase [8]. With training sets of ~6,000 compounds, machine learning methods achieved R² values around 0.90, while traditional methods reached only ~0.65 [8]. Second, descriptor-free models exhibit particular advantages for compounds structurally dissimilar to those in the training set, a coveted quality for real-world applications where chemical diversity is substantial [27].

However, the performance advantages of deep learning approaches become most pronounced with larger datasets. With significantly smaller training sets (303 compounds), DNN maintained a respectable R² value of 0.94 compared to RF's 0.84, while traditional MLR completely failed (R²pred = 0) due to overfitting [8]. This underscores the data dependency of deep learning methods and the continued value of simpler models for smaller datasets.

For natural products, which present unique challenges due to their structural complexity and stereochemical richness, fingerprint performance differs significantly from drug-like molecules. While ECFP is typically the default for drug-like compounds, other fingerprints can match or outperform them for natural product bioactivity prediction, highlighting the importance of context-specific fingerprint selection [26].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Standardized Workflow for Model Comparison

To ensure fair and reproducible comparison of different molecular representation strategies, researchers should adhere to standardized experimental protocols encompassing data curation, model training, and evaluation.

Data Curation Protocol:

- Compound Collection: Assemble molecules from diverse, reliable sources (e.g., PubChem, ChEMBL, in-house databases) with consistent experimental measurements for the target endpoint [27] [29].

- Structure Standardization: Process all structures using toolkits like RDKit or ChEMBL structure curation package to neutralize charges, remove salts, perceive aromaticity, and eliminate stereochemistry if not relevant [29] [26].

- Duplicate Removal: Identify and remove duplicates, retaining the highest quality measurement when conflicts exist [29].

- Dataset Splitting: Partition data into training, validation, and test sets using rational methods (e.g., random, temporal, or scaffold-based splits) to assess generalizability [8].

Model Training Protocol:

- Descriptor Calculation: For traditional models, compute molecular descriptors using standardized software (RDKit, Dragon, PaDEL) or generate molecular fingerprints with specified parameters (ECFP4: radius=2, nBits=1024) [8] [26].

- Model Implementation: Implement comparable machine learning architectures (RF, SVM, DNN) using consistent frameworks (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch) with appropriate hyperparameter optimization [8] [3].

- Descriptor-Free Setup: For deep learning approaches, use raw molecular inputs (SMILES for LSTMs, graphs for GNNs) with standardized preprocessing [27].

Evaluation Protocol:

- Performance Metrics: Calculate multiple metrics (R², accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-ROC) on hold-out test sets to comprehensively assess performance [8] [29].

- Statistical Significance: Perform multiple runs with different random seeds and use statistical tests to confirm performance differences are significant.

- Applicability Domain Assessment: Evaluate model performance within and outside the applicability domain using appropriate methods [29].

QSAR Model Comparison Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit, PaDEL, Dragon | Compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Comprehensive descriptor sets, standardization, open-source options |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, DeepChem | Implement descriptor-free neural networks | GNN support, pretrained models, chemistry-specific layers |

| Model Building Platforms | scikit-learn, KNIME, AutoQSAR | Train traditional machine learning models | User-friendly interfaces, automated workflows, robust implementations |

| Validation Software | QSARINS, OPERA | Model validation and applicability domain assessment | Regulatory compliance, detailed diagnostics [29] |

| Specialized QSAR Tools | VEGA, EPI Suite, ADMETLab | End-to-end QSAR modeling for specific applications | Curated models, regulatory acceptance, specific property focus [30] [29] |

The evolution of molecular representation in QSAR modeling reveals a clear trajectory from expert-defined descriptors to learned representations, with ECFP/FCFP fingerprints representing a sophisticated midpoint in this transition and descriptor-free models embodying the current frontier. The experimental evidence indicates that no single approach dominates all scenarios, with optimal method selection depending on multiple factors including dataset size, chemical diversity, endpoint complexity, and available computational resources.

For many practical applications, particularly with moderate dataset sizes and well-defined chemical series, ECFP-based random forest models continue to offer an excellent balance of performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency [8]. Their robust performance across diverse problems, built-in feature selection capabilities, and resistance to overfitting make them a reliable choice for many drug discovery and toxicity prediction applications. FCFP provides a valuable alternative when functional similarity rather than structural similarity likely drives activity, such as in scaffold hopping and cross-pharmacology studies [26].

For organizations with access to large, high-quality datasets and specialized computational resources, descriptor-free deep learning approaches, particularly graph neural networks, offer compelling performance advantages for complex endpoints with nonlinear structure-activity relationships [28] [3]. Their ability to automatically learn task-relevant features without human bias in descriptor selection, coupled with their native handling of molecular topology, positions them as the future of computational molecular property prediction.

The emerging consensus suggests a hybrid future where descriptor-based and descriptor-free approaches coexist and complement each other in integrated workflows. Traditional fingerprints will likely maintain their relevance for interpretable modeling, rapid screening, and applications with limited data, while descriptor-free methods will increasingly dominate challenges requiring maximal predictive accuracy for complex endpoints across diverse chemical spaces. As benchmark studies continue to refine our understanding of the strengths and limitations of each approach, the field moves closer to the ultimate goal of universally applicable QSAR models capable of accurate property prediction for any molecule of interest.

Implementing Deep Learning and Traditional QSAR in Real-World Discovery

The field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from classical statistical approaches to sophisticated deep learning architectures. This evolution is driven by the need to navigate the increasing complexity and scale of chemical data in modern drug discovery. Traditional QSAR methods, rooted in linear regression and carefully curated molecular descriptors, have long provided interpretable models for predicting biological activity. However, their ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships in large, diverse chemical spaces has remained limited. The integration of deep learning technologies—including Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and multimodal architectures—has unleashed new capabilities for extracting patterns and features directly from molecular representations, significantly advancing predictive performance across multiple drug discovery applications [31] [32].

This performance evaluation examines how these specialized neural architectures are redefining the boundaries of QSAR modeling. Through rigorous benchmarking studies and real-world applications, we analyze the comparative advantages of each architecture against traditional methods and their suitability for specific tasks in the drug discovery pipeline, from virtual screening to lead optimization [33]. The findings presented herein offer researchers and drug development professionals an evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate architectures based on their specific project requirements, data constraints, and performance expectations.

Performance Benchmarking: Deep Learning vs. Traditional QSAR

Quantitative Comparative Studies

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the performance advantages of deep learning architectures over traditional QSAR methods. A comprehensive comparative study evaluated Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and Random Forests (RFs) against classical approaches like Partial Least Squares (PLS) and Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) for predicting inhibitors against MDA-MB-231 cancer cells [8]. As shown in Table 1, machine learning methods demonstrated superior predictive accuracy, particularly with larger training datasets.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches [8]

| Method | Training Set Size: 6069 | Training Set Size: 3035 | Training Set Size: 303 | Architecture Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNN | R² = ~0.90 | R² = ~0.90 | R² = ~0.94 | Deep Learning |

| RF | R² = ~0.90 | R² = ~0.88 | R² = ~0.84 | Machine Learning |

| PLS | R² = ~0.65 | R² = ~0.45 | R² = ~0.24 | Classical QSAR |

| MLR | R² = ~0.65 | R² = ~0.40 | R² = ~0.93* | Classical QSAR |

Note: MLR with 303 compounds showed severe overfitting (R²pred = 0) despite high training R²

The 2025 ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET Antiviral Challenge provided further validation, demonstrating that while classical methods remain competitive for predicting compound potency, modern deep learning algorithms significantly outperformed traditional machine learning in ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) prediction [34]. This real-world benchmarking involved over 65 teams worldwide and highlighted the context-dependent superiority of different approaches.

Task-Specific Performance Variations

The CARA (Compound Activity benchmark for Real-world Applications) study revealed that model performance varies significantly across different drug discovery tasks [33]. Through careful analysis of ChEMBL data distinguishing between virtual screening (VS) and lead optimization (LO) assays, researchers found that popular training strategies like meta-learning and multi-task learning effectively improved classical machine learning methods for VS tasks. In contrast, training QSAR models on separate assays already achieved strong performances in LO tasks, reflecting the distinct data distribution patterns of these applications.

This task-specific performance underscores the importance of matching architectural strengths to application requirements. While deep learning excels at extracting complex patterns from diverse chemical spaces, traditional methods may maintain advantages in data-scarce scenarios or when interpretability is prioritized [8] [33].

Deep Learning Architectures in QSAR: Technical Specifications and Applications

Table 2: Deep Learning Architectures in QSAR: Applications and Strengths

| Architecture | Molecular Representation | Key Strengths | Ideal Use Cases | Notable Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNN (Deep Neural Networks) | Molecular descriptors, fingerprints | Handling high-dimensional data, automatic feature weighting [8] | Bioactivity prediction, ADMET profiling [34] [8] | Identified nanomolar MOR agonists from limited training set (63 compounds) [8] |

| CNN (Convolutional Neural Networks) | Molecular graphs, SMILES strings | Capturing local chemical contexts, spatial hierarchies [35] [36] | Substructure recognition, pattern detection in molecular structures [36] | Multiscale CNN extracts local chemical background from SMILES [35] |

| LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) | SMILES strings, sequences | Modeling sequential dependencies, handling variable-length inputs [35] [36] | Processing SMILES notation, molecular generation, property prediction [35] | Bi-directional GRU/LSTM captures semantic meanings in SMILES [35] |

| Multimodal Models | Multiple representations (graphs, SMILES, descriptors) | Integrating complementary information, capturing comprehensive features [35] | Complex property prediction where single representations are insufficient [35] | State-of-the-art performance on eight benchmark datasets [35] |

| GNN (Graph Neural Networks) | Molecular graphs | Directly encoding molecular topology, atom/bond relationships [31] [35] | Structure-based prediction, capturing intramolecular interactions | Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) capture topological structure [35] |

Multimodal Integration: The State of the Art

The MMRLFN (Multi-Modal Molecular Representation Learning Fusion Network) represents a significant architectural advancement that simultaneously learns and integrates drug molecular features from both molecular graphs and SMILES sequences [35]. This framework employs three complementary deep neural networks—Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) for topological structure, a Multiscale CNN for local chemical context, and Bi-directional GRUs for substructure information—to capture a more comprehensive set of molecular features than any single representation can provide.

When evaluated on eight public datasets covering physicochemical, bioactivity, and physiological-toxicity properties, MMRLFN consistently outperformed models based on mono-modal molecular representations [35]. This demonstrates the power of multimodal approaches to overcome the limitations inherent in single-representation models, such as the neglect of spatial information in SMILES or the challenges with long-range dependencies in graph-based approaches.

Diagram 1: Multimodal molecular representation learning framework that integrates graph and sequence features [35]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Experimental Design

The comparative study between deep learning and classical QSAR methods followed a rigorous experimental protocol [8]. Researchers collected 7,130 molecules with reported MDA-MB-231 inhibitory activities from ChEMBL, then randomly separated them into training (6,069 compounds) and test sets (1,061 compounds). To evaluate model performance with varying data availability, additional training sets of 3,035 and 303 compounds were created. The molecular representations included 613 descriptors derived from AlogP_count, Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs), and Functional-Class Fingerprints (FCFPs).

For the DNN implementation, the model architecture consisted of multiple hidden layers with increasing nodes to allow progressive feature learning. Each layer learned different feature clusters based on the previous layer's output, with the system automatically assigning weights to neurons during training. This architecture enabled the DNN to outperform RF, particularly with smaller training sets, due to its superior capability in weighting important features [8].

Multimodal Model Training Methodology

The MMRLFN framework employed a comprehensive training methodology across eight public datasets involving various molecular properties [35]. The implementation involved:

Data Preprocessing: Molecular structures were converted into both graph representations (with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges) and SMILES sequences standardizes to consistent lengths.

Feature Extraction:

- Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) processed molecular graphs through message-passing operations to capture topological information.

- Multiscale CNN applied convolutional filters of varying sizes to SMILES sequences to extract local chemical contexts at different scales.

- Bi-directional GRUs processed sequential SMILES data to capture long-range dependencies and semantic meanings.

Feature Fusion: Extracted features from all three networks were concatenated and passed through fully connected layers for final property prediction.

Evaluation: Model performance was assessed using root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) for regression tasks, and area under the curve (AUC) for classification tasks, with rigorous cross-validation [35].

Diagram 2: Benchmarking workflow for evaluating QSAR modeling approaches [8] [33]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Databases | ChEMBL [33], BindingDB [33], PubChem [33] | Sources of experimental compound activity data for model training | Millions of well-organized compound activity records from literature and patents |

| Molecular Descriptors | ECFP/FCFP [8], Dragon descriptors [31] | Numerical representation of molecular structures and properties | Circular fingerprints capturing atom neighborhoods and pharmacophore features |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch [36] | Implementation of DNN, CNN, LSTM architectures | Flexible neural network design with GPU acceleration support |

| Specialized QSAR Tools | QSARINS [31], Build QSAR [31] | Classical QSAR model development with validation workflows | Statistical modeling with enhanced validation and visualization tools |

| Representation Tools | RDKit [31], PaDEL [31] | Molecular graph and descriptor generation | Open-source cheminformatics for molecular representation |

The integration of deep learning architectures into QSAR modeling represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery. Evidence from comprehensive benchmarking studies demonstrates that while classical methods maintain utility for specific applications and offer interpretability advantages, deep learning architectures—particularly DNNs, LSTMs, and multimodal models—consistently deliver superior predictive performance for complex tasks including ADMET profiling, bioactivity prediction, and virtual screening.

The future of QSAR modeling lies in the continued development of specialized architectures that can leverage multiple molecular representations simultaneously, as demonstrated by the state-of-the-art performance of multimodal approaches [35]. Furthermore, the emergence of large language models and autonomous agents presents new opportunities for molecular design and synthesis prediction [37]. As these technologies mature and higher-quality, larger-scale datasets become available, the predictive ability, interpretability, and application domain of QSAR models will continue to expand, solidifying their role as indispensable tools in modern drug discovery pipelines [17].

The landscape of early drug discovery has been fundamentally transformed by the emergence of ultra-large chemical libraries, which contain billions of readily available compounds. This expansion offers unprecedented opportunity to identify novel chemical matter but introduces significant computational challenges for traditional virtual screening methods. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging computational paradigms—including deep learning-accelerated screening, evolutionary algorithms, and synthon-based approaches—against traditional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models within this new context. Focusing on practical implementation, experimental validation, and scalability, this analysis provides researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for their screening campaigns.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of various virtual screening approaches as reported in recent large-scale studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methodologies for Ultra-Large Libraries

| Methodology | Reported Hit Rate | Library Size | Key Performance Metrics | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REvoLd (Evolutionary Algorithm) | 869 to 1622x improvement over random [38] | ~20 billion molecules [38] | Strong, stable enrichment; continuous discovery of new scaffolds [38] | High (Explores combinatorial space without full enumeration) [38] |

| RosettaVS (AI-Accelerated Platform) | 14% (KLHDC2); 44% (NaV1.7) [39] | Multi-billion compound libraries [39] | Top 1% Enrichment Factor (EF1%) of 16.72; Superior binding pose prediction [39] | Screening completed in <7 days using HPC cluster [39] |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Identification of nanomolar agonists (~500 nM) [8] | In-house database of 165,000 compounds [8] | R² value of 0.94 with limited training set (n=303) [8] | High after initial model training; efficient with limited data [8] |

| Traditional QSAR (PLS/MLR) | Not specified | Not specified | R² value dropped to 0.24 with small training sets; overfitting concerns [8] | Low to moderate; performance degrades significantly with less data [8] |

| ROSHAMBO2 (3D Similarity) | Not specified | Ultralarge libraries [40] | >200x speedup over original implementation [40] | Very High (GPU-accelerated alignment) [40] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Design

Deep Learning-Accelerated Docking with Active Learning

The RosettaVS platform exemplifies a modern hybrid approach, integrating physics-based docking with deep learning to efficiently screen billion-member libraries [39]. Its experimental protocol is designed for maximum efficiency and accuracy.

Diagram 1: RosettaVS Active Learning Workflow

The methodology employs a two-tiered docking system and active learning [39]:

- VSX (Virtual Screening Express) Mode: An initial rapid screening is performed using a rigid receptor model to quickly evaluate a diverse subset of the library.