Comparative Effectiveness Research in Pharmaceuticals: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) in the pharmaceutical sector, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Effectiveness Research in Pharmaceuticals: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) in the pharmaceutical sector, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational definition and purpose of CER, as defined by the Institute of Medicine, and explores its core question: which treatment works best, for whom, and under what circumstances. The content delves into the key methodological approaches, including randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and evidence synthesis, while addressing critical challenges such as selection bias and data quality. It also examines the validation of CER findings and the comparative reliability of different study designs, concluding with the implications of CER for improving drug development, informing regulatory and payer decisions, and advancing personalized medicine.

What is Comparative Effectiveness Research? Defining the Foundation for Better Drug Decisions

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) is defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) as “the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care” [1]. The fundamental purpose of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers in making informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels [2]. In the specific context of pharmaceutical research, this translates to direct comparisons of drug therapies against other available treatments—including other drugs, non-drug interventions, or surgical procedures—to determine which work best for specific types of patients and under what circumstances [1].

This methodology represents a crucial shift from traditional efficacy research, which asks whether a treatment can work under controlled conditions, toward a focus on how it does work in real-world clinical practice [2]. CER is inherently patient-centered, focusing on the outcomes that matter most to patients in their everyday lives, and forms the foundation for high-value healthcare by identifying the most effective interventions among available alternatives [2].

Core Methodologies for Evidence Generation

The IOM definition emphasizes two core activities: the generation of new comparative evidence and the synthesis of existing evidence. Several established methodological approaches fulfill these functions in pharmaceutical research.

Primary Evidence Generation Methods

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Primary Evidence Generation in Pharmaceutical CER

| Method | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations | Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Participants randomly assigned to treatment groups; differs only in exposure to study variable [1] | Gold standard for causal inference; minimizes confounding [1] | Expensive, time-consuming; may lack generalizability to real-world populations [1] | Head-to-head drug comparisons; establishing efficacy under controlled conditions |

| Observational Studies | Participants not randomized; treatment choices made by patients and physicians [1] | Assesses real-world effectiveness; faster and more cost-efficient; suitable for rare diseases [1] | Potential for selection bias; confounding by indication [1] | Post-market surveillance; effectiveness in subpopulations; long-term outcomes |

| Prospective Observational Studies | Outcomes studied after creation of study protocol; interventions can include medications [1] | Captures real-world practice patterns; can study diverse populations [1] | Still susceptible to unmeasured confounding [1] | Pragmatic trials; patient-centered outcomes research |

| Systematic Reviews | Critical assessment of all research studies on a particular clinical issue using specific criteria [1] | Comprehensive evidence synthesis; identifies consistency of effects across studies [1] | Limited by quality and availability of primary studies [1] | Summarizing body of evidence for drug class comparisons |

Each method contributes distinct evidence for pharmaceutical decision-making. While RCTs provide the most reliable evidence of causal effects, observational studies offer insights into how drugs perform across heterogeneous patient populations in routine care settings [1]. The choice among methods involves balancing scientific rigor with practical considerations including cost, timeline, and generalizability requirements.

Analytical Approaches for CER

Advanced analytical methods are essential for generating valid evidence from observational data, which frequently forms the basis of pharmaceutical CER.

Risk Adjustment: An actuarial tool that identifies a risk score for a patient based on conditions identified via claims or medical records. Prospective risk adjusters use historical claims data to predict future costs, while concurrent risk adjustment uses current medical claims to explain an individual's present costs. Both approaches help identify similar types of patients for comparative purposes [1].

Propensity Score Matching: This method calculates the conditional probability of receiving a treatment given several predictive variables. Patients in a treatment group are matched to control group patients based on their propensity score, enabling estimation of outcome differences between balanced patient groups. This approach helps control for treatment selection biases, including regional practice variations [1].

Evidence Synthesis Approaches

Evidence synthesis represents the second pillar of the IOM definition, systematically integrating findings across multiple studies to develop more reliable and generalizable conclusions about pharmaceutical effectiveness.

Systematic reviews employ rigorous, organized methods for locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular clinical topic using predetermined criteria [1]. When systematic reviews include quantitative pooling of data through meta-analysis, they can provide more precise estimates of treatment effects and examine potential effect modifiers across studies [1].

For pharmaceutical research, these synthesis approaches are particularly valuable for:

- Resolving uncertainty when individual studies report conflicting findings

- Increasing statistical power for subgroup analyses to identify which patients benefit most from specific treatments

- Assessing the consistency of drug effects across different patient populations and care settings

- Informing clinical guideline development and coverage decisions

Implementation and Methodological Considerations

Successfully implementing CER in pharmaceuticals requires careful attention to several methodological and practical considerations that affect the validity and utility of the generated evidence.

Pharmaceutical CER utilizes diverse data sources, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

Claims Data: Historically used for actuarial analyses, these data provide large sample sizes and real-world prescribing information but typically lack clinical detail such as lab results or patient-reported outcomes [1].

Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Contain richer clinical information including vital signs, diagnoses, and treatment responses, though data quality and completeness may vary across institutions [3].

Prospective Data Collection: Specifically designed for research purposes, offering more control over data quality and the ability to capture patient-centered outcomes directly [1].

Data governance represents a critical framework for managing organizational structures, policies, and fundamentals that ensure accurate and risk-free data. Proper data governance establishes standards, accountability, and responsibilities, ensuring that data use provides maximum value while managing handling costs and quality [4]. Throughout the pharmaceutical data lifecycle, this includes planning and designing, capturing and developing, organizing, storing and protecting, using, monitoring and reviewing, and eventually improving or disposing of data [4].

Addressing Bias and Confounding

Selection bias presents a particular challenge in pharmaceutical CER, especially when physicians prescribe one treatment over another based on disease severity or patient characteristics [1]. Beyond the statistical methods previously discussed, approaches to address this include:

- Sensitivity Analyses: Testing how robust findings are to different assumptions about unmeasured confounding

- Instrumental Variable Methods: Using factors associated with treatment choice but not directly with outcomes to estimate causal effects

- High-Dimensional Propensity Scoring: Leveraging the vast number of variables in healthcare databases to improve confounding adjustment

Ethical and Professional Standards

CER investigators must adhere to ethical guidelines throughout research planning, design, implementation, management, and reporting [4]. Key principles include:

- Maintaining independence and avoiding conflicts of interest that could inappropriately influence research findings [4]

- Respecting human rights and ensuring data protection and confidentiality [4]

- Considering gender, ethnicity, age, disability, and other relevant factors when designing and implementing studies [4]

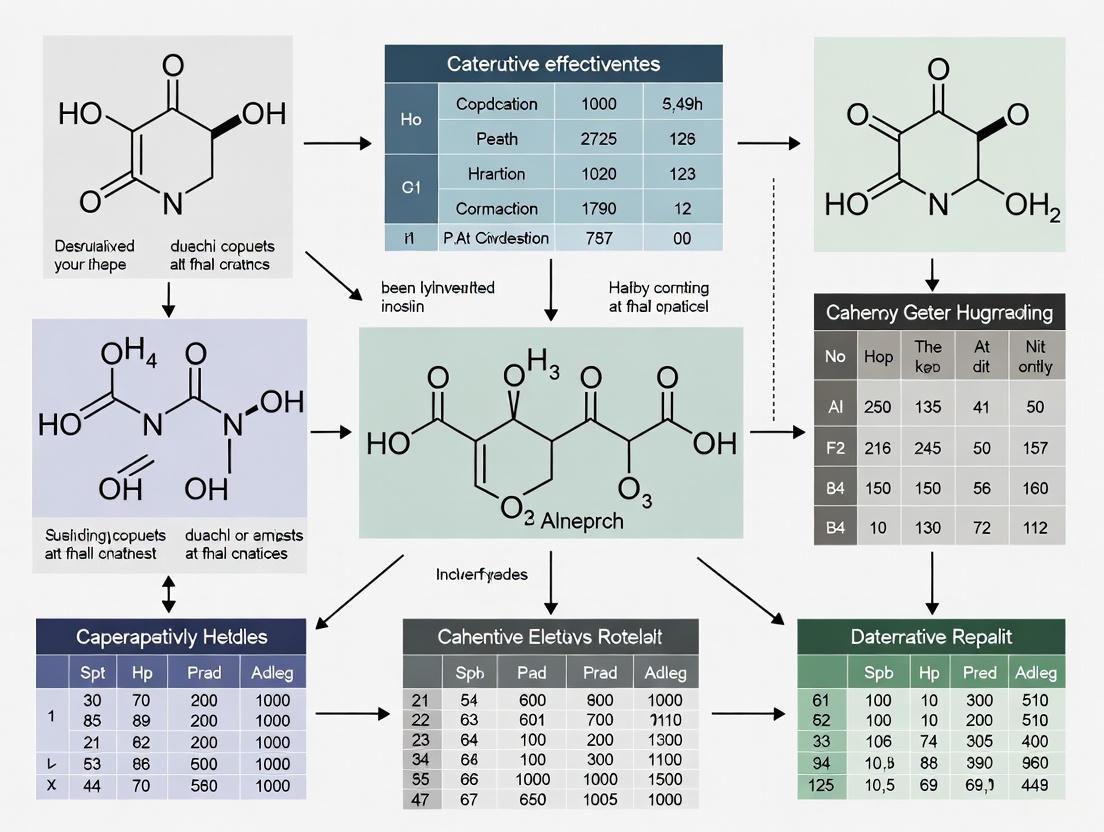

Visualizing CER Methodologies and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key methodological relationships and implementation pathways in pharmaceutical comparative effectiveness research.

CER Methodology Selection Framework

Pharmaceutical CER Implementation Pathway

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical CER

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in CER | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Infrastructure | Electronic Health Records, Claims Databases, Research Data Networks | Provides real-world treatment and outcome data | Observational studies; post-market surveillance; pragmatic trials |

| Biostatistical Packages | R, SAS, Python with propensity score matching libraries | Implements advanced adjustment methods for non-randomized data | Addressing confounding; risk adjustment; sensitivity analyses |

| Systematic Review Tools | Cochrane Collaboration software, meta-analysis packages | Supports evidence synthesis and quantitative pooling | Drug class reviews; comparative effectiveness assessments |

| Patient-Reported Outcome Measures | Standardized validated instruments for symptoms, function, quality of life | Captures outcomes meaningful to patients beyond clinical endpoints | Patient-centered outcomes research; quality of life comparisons |

| Clinical Registries | Disease-specific patient cohorts with detailed clinical data | Provides rich clinical context beyond routine care data | Studying rare conditions; long-term treatment outcomes |

The IOM definition of CER as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods" provides a comprehensive framework for advancing pharmaceutical research [1]. By employing appropriate methodological approaches—including randomized trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews—and addressing key implementation considerations around data quality, bias adjustment, and ethical standards, researchers can generate robust evidence to inform healthcare decisions [1] [4]. The continued refinement of these methods and their application to pressing therapeutic questions remains essential for achieving the ultimate goal of CER: improving health outcomes through evidence-based, patient-centered care.

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) is a rigorous methodological approach defined by the Institute of Medicine as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care" [1]. The core purpose of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policymakers in making informed decisions that improve health care outcomes at both individual and population levels by determining which treatment works best, for whom, and under what circumstances [1]. Unlike traditional efficacy studies that determine if an intervention works under ideal conditions, CER focuses on comparing available interventions in real-world settings to guide practical decision-making. In pharmaceutical research, this framework is increasingly critical for demonstrating value across the drug development lifecycle, from early clinical trials to post-market surveillance and health technology assessment.

CER fundamentally differs from cost-effectiveness analysis as it typically does not consider intervention costs, focusing instead on direct comparison of health outcomes [1]. This distinction is crucial for regulatory and reimbursement decisions where both clinical and economic value propositions must be evaluated separately. As pharmaceutical innovation accelerates with complex therapies for conditions like Alzheimer's disease and obesity, CER provides the evidentiary foundation for stakeholders to navigate treatment options in an increasingly crowded therapeutic landscape [5] [6].

Methodological Approaches in Comparative Effectiveness Research

Core Research Methods

CER employs three primary methodological approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications in pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Core Methodological Approaches in Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Method | Definition | Strengths | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Review | Critical assessment of all research studies addressing a clinical issue using specific criteria [1] | Comprehensive evidence synthesis; identifies consensus and gaps | Dependent on quality of primary studies; time-consuming | Foundational evidence assessment; guideline development |

| Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Participants randomly assigned to different interventions with controlled follow-up [1] | Gold standard for causality; minimizes confounding | Expensive; may lack generalizability; ethical constraints | Establishing efficacy under controlled conditions |

| Observational Studies | Analysis of interventions chosen in clinical practice without randomization [1] | Real-world relevance; larger sample sizes; suitable for rare diseases | Potential selection bias; confounding variables | Post-market surveillance; rare diseases; long-term outcomes |

Method Selection Framework

The choice of CER methodology depends on multiple factors including research question, available resources, patient population, and decision context. Randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard for establishing causal relationships but can be prohibitively expensive and may lack generalizability to broader populations [1]. Observational studies using real-world data from electronic health records, claims databases, or registries provide complementary evidence about effectiveness in routine practice settings but require sophisticated statistical methods to address potential confounding and selection bias [1].

The growing emphasis on patient-centered outcomes in drug development has increased the importance of pragmatic clinical trials that blend elements of both approaches by testing interventions in diverse, real-world settings while maintaining randomization [7]. Regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the value of this methodological spectrum, with recent guidance supporting innovative trial designs for rare diseases and complex conditions where traditional RCTs may be impractical [7].

CER Methodological Workflow and Analysis Techniques

The conduct of robust comparative effectiveness research follows a systematic workflow with specific analytical techniques to ensure validity and relevance to decision-makers.

Figure 1: CER Methodological Workflow and Decision Process. This diagram illustrates the systematic process for conducting comparative effectiveness research, highlighting key methodological decision points from research question formulation through dissemination of findings for decision support.

Addressing Bias in Observational Studies

Observational CER studies require specific methodological approaches to minimize selection bias and confounding, two significant threats to validity:

Risk Adjustment: Actuarial tools that identify risk scores for patients based on conditions identified via claims or medical records. Prospective risk adjusters use historical claims data to predict future costs, while concurrent risk adjustment explains current costs using contemporaneous data [1].

Propensity Score Matching: A statistical method that calculates the conditional probability of receiving treatment given several predictive variables. Patients in treatment groups are matched to control group patients based on their propensity scores, creating balanced comparison groups for outcome analysis [1].

These techniques help simulate randomization in observational settings, though residual confounding may remain. Recent advances in causal inference methods, including instrumental variable analysis and marginal structural models, provide additional tools for addressing these challenges in pharmaceutical CER.

Analytical Framework and Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Methodological Tools

CER employs specific "research reagent solutions" - methodological tools and data sources that form the foundation for robust comparative analyses.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in CER | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Electronic Health Records | Provide detailed clinical data from routine practice | Real-world effectiveness, safety monitoring, subgroup analysis |

| Administrative Claims Data | Offer comprehensive healthcare utilization information | Treatment patterns, economic outcomes, longitudinal studies | |

| Patient Registries | Collect standardized data on specific populations | Rare diseases, chronic conditions, long-term outcomes | |

| Statistical Methods | Propensity Score Analysis | Controls for confounding in observational studies | Balancing treatment groups on measured covariates |

| Risk Adjustment Models | Accounts for differences in patient case mix | Fair comparisons across providers, systems, or treatments | |

| Meta-analysis Techniques | Synthesizes evidence across multiple studies | Systematic reviews, guideline development | |

| Modeling Approaches | Decision-Analytic Models | Extrapolates long-term outcomes from short-term data | Health technology assessment, drug valuation [5] [8] |

| Markov Models | Simulates disease progression over time | Chronic conditions, lifetime cost-effectiveness [9] | |

| Validation Tools | Systematic Model Assessment (SMART) | Evaluates model adequacy and justification of choices | Ensuring models are fit for purpose [8] |

| Technical Verification (TECH-VER) | Validates computational implementation of models | Code verification, error checking [8] |

Quantitative Assessment in Current Pharmaceutical Research

The application of CER principles across therapeutic areas demonstrates the scope and impact of this approach in contemporary drug development.

Table 3: Quantitative Assessment of CER in Current Drug Development Pipelines

| Therapeutic Area | Pipeline Size (Agents) | Disease-Targeted Therapies | Repurposed Agents | Trials Using Biomarkers | Key CER Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease [6] | 138 agents in 182 trials | 73% (30% biologic, 43% small molecule) | 33% of pipeline | 27% of trials use biomarkers as primary outcomes | Demonstrating clinical meaningfulness of biomarker changes |

| Obesity Pharmacotherapies [5] | Multiple new agents (semaglutide, tirzepatide, liraglutide) | 100% (metabolic targets) | Limited information | Weight change as primary outcome | Long-term BMI trajectory modeling; cardio-metabolic risk extrapolation |

Regulatory and Health Technology Assessment Context

Integration into Decision-Making Frameworks

CER findings increasingly inform regulatory and reimbursement decisions through structured assessment processes. Health technology assessment (HTA) bodies like the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) require robust comparative evidence to evaluate new pharmaceuticals against existing standards of care [5]. This evaluation faces specific methodological challenges, particularly for chronic conditions like obesity and Alzheimer's disease where long-term outcomes must be extrapolated from shorter-term clinical trials [5] [6].

Modeling approaches must address four key challenges in this context: (1) modeling long-term disease trajectories with and without treatment, (2) estimating time on treatment and discontinuation patterns, (3) linking intermediate endpoints to final clinical outcomes using risk equations, and (4) accounting for clinical outcomes not solely related to the primary disease pathway [5]. The Systematic Model Adequacy Assessment and Reporting Tool (SMART) provides a framework for developing and validating these models, with 28 specific features to ensure models are adequately specified without unnecessary complexity [8].

Recent Regulatory Developments

Regulatory agencies worldwide are updating guidance to incorporate CER principles and real-world evidence into drug development:

The FDA has issued draft guidance on "Obesity and Overweight: Developing Drugs and Biological Products for Weight Reduction" to establish standards for demonstrating comparative efficacy and safety [10].

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has released reflection papers on incorporating patient experience data throughout the medicinal product lifecycle [7].

China's NMPA has implemented regulatory revisions to accelerate drug development through adaptive trial designs that facilitate comparative assessment [7].

These developments reflect the growing recognition that pharmaceutical value must be demonstrated through direct comparison with existing alternatives rather than through placebo-controlled trials alone.

Comparative Effectiveness Research represents a fundamental shift in pharmaceutical evidence generation, moving from establishing efficacy under ideal conditions to determining comparative value in real-world practice. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering CER methodologies is increasingly essential for demonstrating product value across the development lifecycle. The ongoing refinement of observational methods, statistical approaches to address confounding, and modeling techniques to extrapolate long-term outcomes will further strengthen CER's role in informing decisions for consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policymakers.

As regulatory and reimbursement frameworks increasingly require comparative evidence, pharmaceutical researchers must strategically integrate CER principles from early development through post-market surveillance. This evolution toward more patient-centered, comparative evidence generation promises to better align pharmaceutical innovation with the needs of all healthcare decision-makers.

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) is fundamentally designed to inform health-care decisions by providing evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of different treatment options [11]. This evidence is generated from studies that directly compare drugs, medical devices, tests, surgeries, or ways to deliver health care. In the specific context of pharmaceutical research, CER moves beyond the foundational question of "Does this drug work?" to address the more central and complex question: "Which treatment works best, for whom, and under what circumstances?" [12]. This refined focus is crucial for moving toward a more patient-centered and efficient healthcare system, where treatment decisions can be tailored to individual patient needs and characteristics.

The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) underscores that scientifically-sound CER is essential for prescribers and patients to evaluate and select the treatment options most likely to achieve a desired therapeutic outcome [12]. Furthermore, health care decision-makers use this information when designing benefits to ensure that safe and effective medications with the best value are provided across all stages of treatment [12]. This promotes optimal medication use while also encouraging the prudent management of financial resources within the health care system.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

Core Principles of CER

The conduct of CER is guided by several key principles aimed at ensuring its relevance and reliability [12]:

- Scientifically-Sound Research Design: CER must adhere to optimal research design and transparency standards. While randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are preferred, researchers should have the flexibility to use other designs, including analyses of real-world evidence (RWE), to inform healthcare decisions [12].

- Comprehensive Evaluation: Researchers should be free to evaluate the relative values of the treatments studied, which includes assessing direct and indirect costs in addition to patient outcomes [12].

- Transparency and Accessibility: Findings from CER, particularly those funded by the federal government, should be publicly available. Results should be presented in a manner understandable to lay persons to promote effective patient-provider collaboration [12].

- Informative, Not Mandating: CER results are intended to inform, not dictate, coverage decisions. Health care decision-makers must retain the flexibility to use research results as one of several variables when designing benefits for the diverse populations they serve [12].

The Critical Challenge of Heterogeneity

A core concept in answering the "for whom" aspect of the central question is clinical heterogeneity. It is defined as the variation in study population characteristics, coexisting conditions, cointerventions, and outcomes evaluated across studies that may influence or modify the magnitude of an intervention's effect [13]. In essence, it is the variability in health outcomes between individuals receiving the same treatment that can be explained by differences in the patient population or context [14].

Failing to account for this heterogeneity can lead to suboptimal decisions, inferior patient outcomes, and economic inefficiency. When coverage decisions are based solely on population-level evidence (the "average" patient), they can restrict treatment options for individuals who differ from this average, potentially denying them access to therapies that are safe, effective, and valuable for their specific situation [14].

Table: Types of Heterogeneity in CER

| Type of Heterogeneity | Definition | Impact on CER |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Heterogeneity | Variability in patient characteristics, comorbidities, and co-interventions that modify treatment effect [13]. | Influences whether a treatment's benefits and harms apply equally to all subgroups within a broader population. |

| Methodological Heterogeneity | Variability in study design, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and analysis methods across studies [13]. | Can make it difficult to synthesize results from different studies and may introduce bias. |

| Statistical Heterogeneity | Variability in observed treatment effects that is beyond what would be expected by chance alone [13]. | Often a signal that underlying clinical or methodological heterogeneity is present. |

| Heterogeneity in Patient Preferences | Differences in how patients value specific health states or treatment attributes (e.g., mode of administration) [14]. | Critical for patient-centered care; affects adherence and the overall value of a treatment to an individual. |

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Study Designs for CER

A range of study designs can be employed to conduct CER, each with distinct strengths and applicability.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are often considered the gold standard for establishing the efficacy of an intervention under ideal conditions. For CER, pragmatic clinical trials (PCTs)—a type of RCT—are particularly valuable. They are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in real-world practice settings with heterogeneous patient populations, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the results [12].

Observational studies using Real-World Evidence (RWE) are increasingly important. These studies analyze data collected from routine clinical practice, such as electronic health records, claims data, and patient registries. They are crucial for understanding how treatments perform in broader, more diverse patient populations and for addressing questions about long-term effectiveness and rare adverse events [12].

Systematic Reviews and Network Meta-Analyses (NMAs) are powerful tools for synthesizing existing evidence. Systematic reviews methodically gather and evaluate all available studies on a specific clinical question. NMA extends this by allowing for the comparison of multiple treatments simultaneously, even if they have not been directly compared in head-to-head trials. This can provide a hierarchy of treatment options, as demonstrated in a recent NMA of Alzheimer's disease drugs [15].

Addressing Heterogeneity: Analytical Techniques

To answer the "for whom" and "under what circumstances" components, specific analytical techniques are employed:

- Subgroup Analysis: This involves analyzing the treatment effect within specific patient subgroups defined by characteristics such as age, sex, race, genetic markers, or disease severity. For example, a cancer treatment statistic shows that Black people with stage I lung cancer were less likely to undergo surgery than their White counterparts (47% vs. 52%), highlighting a critical disparity that subgroup analysis can uncover [16].

- Meta-Regression: This technique is used in the context of meta-analysis to explore whether specific study-level characteristics (e.g., average patient age, dose of drug) are associated with the observed treatment effects.

- Individual Patient Data (IPD) Meta-Analysis: This is considered the gold standard for investigating heterogeneity, as it involves obtaining and analyzing the original raw data from each study. This allows for a more powerful and flexible analysis of patient-level subgroups.

Table: Methods for Investigating Heterogeneity in CER

| Method | Description | Primary Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup Analysis | Analyzes treatment effects within specific, predefined patient subgroups. | To identify whether treatment efficacy or safety differs based on a patient characteristic (e.g., age, biomarker status). | Risk of false positives due to multiple comparisons; should be pre-specified in the study protocol. |

| Network Meta-Analysis | Simultaneously compares multiple interventions using both direct and indirect evidence. | To rank the efficacy of several treatment options for a condition and explore effect modifiers across the network. | Requires underlying assumption of similarity and transitivity between studies. |

| Meta-Regression | Examines the association between study-level covariates and the estimated treatment effect. | To explore sources of heterogeneity across studies (e.g., year of publication, baseline risk). | Ecological fallacy: a study-level association may not hold true at the individual patient level. |

Case Studies in CER Application

Case Study 1: Comparative Drug Efficacy in Alzheimer's Disease

A 2025 network meta-analysis directly addressed the central question by comparing the efficacy of updated drugs for improving cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer's disease [15]. The study synthesized data from 11 randomized controlled trials involving 6,241 participants to compare and rank six different interventions against each other and placebo.

Table: Efficacy Rankings of Alzheimer's Drugs from a Network Meta-Analysis [15]

| Drug | Primary Mechanism of Action | ADAS-cog (SUCRA%) | CDR-SB (SUCRA%) | ADCS-ADL (SUCRA%) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GV-971 (Sodium oligomannate) | Inhibits Aβ aggregation & depolymerization | 76.1% | - | - | Best for improving ADAS-cog & NPI scores |

| Lecanemab | Anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody | 67.3% | 98.1% | - | Most effective in improving CDR-SB scores |

| Donanemab | Anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody | - | - | 99.8% | Most promising to slow decline in ADCS-ADL scores |

| Masupirdine | 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | - | - | - | Effect on MMSE significantly better than others |

This analysis provides a clear, quantitative answer to "which treatment works best" for specific clinical endpoints, guiding clinicians in selecting therapies based on the cognitive or functional domain they wish to target.

Case Study 2: Addressing Disparities in Cancer Treatment

Cancer survivorship statistics reveal profound racial disparities in treatment patterns, providing a stark example of the "for whom" question. For instance, in 2021, Black individuals with early-stage lung cancer were less likely to undergo surgery than their White counterparts (47% vs. 52%) [16]. An even larger disparity was observed in rectal cancer, where only 39% of Black people with stage I disease underwent proctectomy/proctocolectomy compared to 64% of White people [16]. These findings underscore that the "best" treatment is not being applied uniformly across patient subgroups. CER that investigates the underlying causes of these disparities—which may include access to care, provider bias, or social determinants of health—is vital for developing targeted, multi-level efforts to ensure all patients receive high-quality care [16].

Successful execution of CER, particularly in drug development, relies on a suite of specialized tools and resources.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Advanced CER

| Tool/Resource | Function in CER | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | A liquid biopsy method for detecting tumor-derived DNA in the bloodstream. | Monitoring response to treatment in early-phase clinical trials; guiding dose escalation and go/no-go decisions [17]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Provides a map of gene expression within the context of tissue architecture. | Understanding the tumor microenvironment to identify novel immunotherapy targets and predictive biomarkers [17]. |

| Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) | Computational analysis of complex datasets to identify patterns and predictions. | Analyzing H&E slides to impute transcriptomic profiles and spot early hints of treatment response or resistance [17]. |

| Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cells | Engineered T-cells designed to target specific cancer antigens. | Developing "Boolean logic" CAR T-cells that activate only upon encountering two tumor markers, sparing healthy cells [17]. |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | Targeted therapeutics consisting of a monoclonal antibody linked to a cytotoxic payload. | Exploring novel targets, linker technologies, and less toxic payloads to improve therapeutic index [17]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of CER is rapidly evolving, driven by technological advancements and a growing emphasis on patient-centeredness. Key trends shaping its future include:

- Expansion of Precision Medicine: The pipeline for targeted therapies continues to grow. In oncology, research is moving beyond first-generation KRAS^G12C^ inhibitors to target other variants like KRAS^G12D^ and toward pan-KRAS and pan-RAS inhibitors, offering hope for treating previously "undruggable" cancers like pancreatic cancer [17].

- Advancements in Immunotherapy: The success of cell-based therapies like Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) therapy in solid tumors is a major breakthrough [17]. Research is now focused on improving scalability and access through "off-the-shelf" allogeneic CAR T-cell therapies and enhancing specificity with Boolean logic-gated CAR T-cells [17].

- Incorporation of Patient Preferences: There is a growing recognition that economic evaluations and coverage decisions must account for heterogeneity in patient preferences regarding health states and treatment attributes [14]. This is particularly important in the U.S. where cost-sharing imposes significant financial considerations.

- Integration of Biomarkers in Clinical Trials: Biomarkers are playing an increasingly critical role. In the 2025 Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline, biomarkers were among the primary outcomes of 27% of active trials, used for determining trial eligibility and measuring pharmacodynamic response [6].

Answering the central question—"Which treatment works best, for whom, and under what circumstances?"—is the defining challenge and purpose of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Through the rigorous application of diverse methodological approaches, from pragmatic trials and real-world evidence analysis to advanced techniques like network meta-analysis and subgroup exploration, CER moves beyond average treatment effects. The ultimate goal is to generate the nuanced evidence needed to tailor therapeutic decisions to individual patient characteristics, preferences, and clinical contexts. As the field advances with new scientific tools and a deeper commitment to addressing heterogeneity and disparities, CER will remain indispensable for guiding pharmaceutical research and development toward more effective, efficient, and patient-centered care.

Distinguishing Efficacy in Trials from Effectiveness in Real-World Practice

In pharmaceutical research, a fundamental distinction exists between the efficacy of a drug—its performance under the ideal and controlled conditions of a randomized controlled trial (RCT)—and its effectiveness—its performance in real-world clinical practice among heterogeneous patient populations under typical care conditions [18]. This distinction lies at the heart of Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER), which the Institute of Medicine defines as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care" [19]. The goal of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers in making informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels [19].

Efficacy, demonstrated through traditional RCTs, establishes the biological activity and potential utility of a pharmaceutical agent. However, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, homogeneous patient populations, protocol-driven treatments, and close monitoring create an artificial environment that does not reflect ordinary clinical practice [20] [18]. Effectiveness, in contrast, examines how interventions work for diverse patients in community settings, encompassing the full spectrum of comorbidities, adherence patterns, and clinical decision-making that characterizes real-world care [21]. This whitepaper examines the methodological frameworks, analytical approaches, and evidence synthesis techniques that bridge this critical divide in pharmaceutical research and development.

Methodological Frameworks for Evidence Generation

Randomized Controlled Trial Designs

While traditional RCTs establish efficacy, adaptations to the classic RCT design enhance their ability to inform real-world effectiveness [20].

Table 1: Adaptive and Pragmatic Trial Designs for Effectiveness Research

| Design Type | Key Features | Applications in CER | Examples in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Trials | Uses accumulating evidence to modify trial design; may change interventions, doses, or randomization probabilities | Increases efficiency and probability that participants benefit; evaluates multiple agents simultaneously | I-SPY2 trial for neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment uses tumor profiles to assign patients [20] |

| Pragmatic Trials | Expands eligibility criteria; allows flexibility in intervention application; reduces intensity of follow-up | Maximizes relevance for clinicians and policy makers; reflects real-world practice patterns | CALGB 49907 in early-stage breast cancer used Bayesian predictive probabilities for sample size [20] |

| Large Simple Trials | Enrolls large numbers of participants with minimal data collection; focuses on final health outcomes | Evaluates final health outcomes like mortality across diverse populations | ALLHAT (N=42,418), ACCORD (N=10,251), STAR (N=19,747) for cardiovascular risk and prevention [18] |

Observational Study Designs

Observational studies comprise a growing proportion of CER because of their efficiency, generalizability to clinical practice, and ability to examine differences in effectiveness across patient subgroups [20]. These studies compare outcomes between patients who receive different interventions through clinical practice rather than investigator randomization [20]. Common designs include:

- Prospective cohort studies: Participants are recruited at the time of exposure and followed forward in time

- Retrospective cohort studies: The exposure occurred before participants are identified, using existing data sources

- Case-control studies: Participants are selected based on outcome status, with exposure histories compared between cases and controls

The primary limitation of observational studies is susceptibility to selection bias and confounding, particularly "confounding by indication," where disease severity or patient characteristics influence both treatment selection and outcomes [20] [18]. For example, new agents may be more likely to be used in patients for whom established therapies have failed, creating a false impression of reduced effectiveness [20].

Analytical Methods for Addressing Bias in Observational Data

Several statistical approaches have been developed to mitigate bias in observational studies of pharmaceutical effectiveness:

- Multivariable Regression: Adjusts for measured confounders by including them as covariates in statistical models [20]

- Propensity Score Methods: Create balanced comparison groups by matching, weighting, or stratifying patients based on their probability of receiving a treatment given observed covariates [22] [18]. In cardiovascular CER, methods including regression modeling, inverse probability of treatment weighting, and optimal full propensity matching produced essentially equivalent survival plots, suggesting similar comparative effectiveness conclusions [23] [22]

- Instrumental Variable Analysis: Uses a variable associated with treatment choice but not directly with outcomes to address unmeasured confounding [18]. This approach is particularly valuable when unmeasured factors such as extent of disease could affect both outcome and treatment selection [18]

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Addressing Confounding in Observational CER

| Method | Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariable Regression | Statistically adjusts for measured confounders | Straightforward implementation and interpretation | Limited to measured covariates; model misspecification concerns |

| Propensity Score Matching | Creates comparable groups based on probability of treatment | Mimics randomization in creating balanced groups | Still only addresses measured confounders |

| Inverse Probability Weighting | Creates a pseudo-population where treatment is independent of covariates | Uses entire sample; efficient estimation | Unstable with extreme propensity scores |

| Instrumental Variables | Uses a variable associated with treatment but not outcome | Addresses unmeasured confounding | Requires valid instrument; reduces precision |

Data Synthesis Methods for Comparative Effectiveness

Evidence Synthesis Approaches

Evidence synthesis methodologies combine results from multiple studies to strengthen conclusions about pharmaceutical effectiveness [18]:

- Systematic Reviews: Methodical approaches to identifying, appraising, and synthesizing all relevant studies on a specific research question. Systematic reviews are a major component of evidence-based medicine and can be adapted to CER by broadening the types of studies included and examining the full range of benefits and harms of alternative interventions [20]

- Meta-analysis: Statistical techniques for combining quantitative results from multiple studies. Traditional meta-analyses may be limited in providing useful comparative effectiveness data because they often combine studies with placebo arms rather than active comparators [18]

- Network Meta-analysis: Allows for indirect comparisons of multiple interventions even when they have not been directly compared in head-to-head trials. This approach continuously summarizes and updates evidence as new studies emerge, offering improvements in power to detect treatment effects and generalizability of inferences [22]

Integrating RCT and Observational Evidence

CER increasingly employs hierarchical models that incorporate both individual-level patient data and aggregate data from published studies, combining RCT and observational evidence [23] [22]. This integration increases the precision of effectiveness estimates and enhances the generalizability of findings across diverse patient populations [22]. In cardiovascular research, adding individual-level registry data to RCT network meta-analysis increased the precision of hazard ratio estimates without changing comparative effectiveness point estimates appreciably [23].

Figure 1: Integrated Framework for Comparative Effectiveness Evidence. This diagram illustrates how diverse data sources and study designs contribute to evidence synthesis for healthcare decision-making.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Data Management and Quality Assurance

Robust data management is critical for CER to ensure that data is accurate, reliable, and ethically handled throughout the research process [24]. Key data sources include:

- Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Contain detailed clinical information but may have missing data and variability in documentation practices

- Administrative Claims Data: Include billing information for large populations but lack clinical granularity

- Patient Registries: Systematically collect standardized data on patients with specific conditions or exposures

- Clinical Trials Databases: Provide rich, protocol-driven data, often with limited generalizability

Data management processes must address collection, cleaning, integration, and storage, with particular attention to handling missing data, ensuring integrity, and maintaining security and privacy [24]. CER studies often require linking disparate data sources and harmonizing variables across different systems and time periods [24].

Quality Assurance and Bias Mitigation

Addressing potential biases requires both design and analytical approaches [24]:

- Data Validation: Identifying duplicate records, missing values, outliers, and inconsistencies

- Sensitivity Analyses: Examining how missing data or different analytical assumptions might affect conclusions

- Measured Confounder Adjustment: Ensuring adequate assessment of potential confounders, as demonstrated by the example of hormone replacement therapy studies, where adjustment for socioeconomic status eliminated spurious protective effects [20]

Decision Science and Value Assessment

Decision Analysis and Modeling

Decision models are particularly suited to CER because they make quantitative estimates of expected outcomes based on data from a range of sources [20]. These estimates can be tailored to patient characteristics and can include economic outcomes to assess cost-effectiveness [20]. Modeling approaches include:

- Markov Models: Simulate disease progression through various health states over time

- Microsimulation Models: Track individual patients through possible health trajectories

- Discrete Event Simulation: Models complex systems with interdependent processes and resource constraints

Value of Information Analysis

Value of information (VOI) methodology estimates the expected value of future research by comparing health policy decisions based on current knowledge with decisions based on more precise information that could be obtained from additional research [23]. In cardiovascular CER, VOI analysis demonstrated that the value of additional research was greatest in the 1980s when uncertainty about comparative effects of percutaneous coronary intervention was high, but declined substantially in the 1990s as evidence accumulated [23]. This approach helps determine optimal investment in pharmaceutical research by identifying which comparisons have the greatest decision uncertainty [23].

Distinguishing efficacy from effectiveness requires methodological sophistication in both evidence generation and synthesis. While RCTs remain fundamental for establishing pharmaceutical efficacy, adaptations including pragmatic trials, observational studies with advanced causal inference methods, and evidence synthesis approaches that integrate diverse data sources are essential for understanding real-world effectiveness. The choice of method for CER is driven by the relative weight placed on concerns about selection bias and generalizability, as well as pragmatic considerations related to data availability and timing [20]. As pharmaceutical research increasingly focuses on personalized medicine, these methodologies will continue to evolve, providing richer evidence about which interventions work best for which patients under specific circumstances [25]. Ultimately, closing the gap between efficacy and effectiveness requires a learning healthcare system that continuously generates and applies evidence to improve patient outcomes [21].

The Growing Importance of CER in Controlling Healthcare Costs and Improving Value

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) is fundamentally defined as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care" [26] [27]. In the specific context of pharmaceutical research, CER moves beyond simple comparisons against placebo to direct, head-to-head comparisons of drugs against other drugs or therapeutic alternatives to determine which work best for which patients and under what circumstances [28]. The core question driving CER is which treatment works best, for whom, and under what circumstances [26]. This patient-centered approach aims to provide the evidence necessary for patients, clinicians, and policymakers to make more informed decisions that improve health care at both individual and population levels [26] [29].

The growing emphasis on CER stems from several critical factors within the healthcare system. Limitations of traditional regulatory trials have become increasingly apparent, as these explanatory trials are conducted under idealized conditions with stringent inclusion criteria, making it difficult to apply their results to the average patient seen in real-world practice [29]. Furthermore, the documented unwarranted variation in medical treatment, cost, and outcomes suggests substantial opportunities for improvement in our health care system [26]. Researchers have found that "patients in the highest-spending regions of the country receive 60 percent more health services than those in the lowest-spending regions, yet this additional care is not associated with improved outcomes" [26]. CER addresses these challenges by focusing on evidence generation in real-world settings that reflects actual patient experiences and clinical practice.

Methodological Approaches to CER

CER employs a diverse toolkit of research methodologies, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications in pharmaceutical research.

Core Study Designs in CER

Table 1: Comparison of Core CER Study Designs

| Method | Definition | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials (Pragmatic) | Participants randomly assigned to interventions; conducted in routine clinical practice [26] [29] | High internal validity; minimizes confounding; gold standard for causal inference [29] | Expensive, time-consuming; may lack generalizability to broad populations [1] | Head-to-head drug comparisons when feasible; establishing efficacy effectiveness |

| Observational Studies | Participants not randomized; treatment choices made by patients/physicians [1] | Real-world setting; larger, more diverse populations; cost-efficient; suitable for rare diseases [1] [29] | Potential for selection bias and confounding [1] [29] | Post-market safety studies; rare disease research; long-term outcomes |

| Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analysis | Critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies addressing a clinical issue [1] | Comprehensive evidence synthesis; identifies consistency across studies [1] [29] | Limited by quality of primary studies; potential publication bias | Summarizing body of evidence; informing guidelines and policy |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Addressing Bias in Observational Studies: CER has developed sophisticated methodological approaches to address limitations in observational studies. Propensity score analysis involves balancing the factors influencing treatment choice, thereby reducing selection bias [1] [29]. This method matches patients in different treatment groups based on their probability of receiving a particular treatment, creating comparable groups for analysis. The instrumental variable method is another analytical approach that uses a characteristic (instrument) associated with treatment allocation but not the outcome of interest, such as geographical area or distance to a healthcare facility, to account for unmeasured confounding [29].

New-User Designs: To address the "time-zero" problem in observational studies, CER often employs "new-user" designs that exclude patients who have already been on the treatment being evaluated [29]. This approach helps avoid prevalent user bias, which occurs when only patients who have tolerated a drug remain on it, potentially skewing results.

Adaptive Trial Designs: The introduction of Bayesian and analytical adaptive methods in randomized trials helps overcome some limitations of traditional RCTs, including reduced time requirements, more flexible sample sizes, and lower costs [29].

Experimental Protocols in CER

Protocol for Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trials

Pragmatic RCTs are designed to measure the benefit produced by treatments in routine clinical practice, bridging the gap between explanatory trials and real-world application [26]. The following protocol outlines key considerations:

Research Question Formulation: Define clinically relevant comparisons between active treatments (Drug A vs. Drug B) rather than placebo comparisons, unless ethically justified [29]. Questions should address decisions faced by real-world clinicians and patients.

Study Population Selection: Employ broader inclusion criteria with minimal exclusions to ensure the study population reflects real-world patient diversity, including those with comorbidities, varying ages, and different racial and ethnic backgrounds [29].

Intervention Protocol: Allow flexibility in dosing and administration to mirror clinical practice while maintaining protocol integrity. Implement usual care conditions rather than highly controlled intervention protocols.

Outcome Measurement: Select patient-centered outcomes that matter to patients, such as quality of life, functional status, and overall survival, rather than solely relying on biological surrogate markers [29].

Follow-up Procedures: Implement passive follow-up through routine care mechanisms, electronic health records, or registries to reduce participant burden and enhance generalizability [29].

Protocol for Retrospective Observational Studies Using Claims Data

Observational studies using existing data sources represent a core methodology in CER, particularly for pharmaceutical outcomes research:

Data Source Identification: Secure appropriate data sources, which may include administrative claims data, electronic health records, clinical registries, or linked data systems [1] [29]. The Multi-Payer Claims Database and Chronic Conditions Warehouse are examples of data infrastructures supporting CER [30].

Cohort Definition: Apply explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the study population. Identify the "time-zero" for each patient—the point at which they become eligible for the study [29].

Covariate Assessment: Measure baseline patient characteristics, including demographics, clinical conditions, healthcare utilization, and provider characteristics, that may influence treatment selection or outcomes.

Propensity Score Development: Estimate propensity scores using logistic regression with treatment assignment as the outcome and all measured baseline characteristics as predictors [1] [29].

Propensity Score Implementation: Apply propensity scores through matching, weighting, or stratification to create balanced comparison groups [1].

Outcome Analysis: Compare outcomes between treatment groups using appropriate statistical methods, accounting for residual confounding and the matched or weighted nature of the sample.

Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct multiple sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of findings to different methodological assumptions, including unmeasured confounding [29].

Observational Study Workflow

Key Tools and Frameworks for CER Implementation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CER

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in CER | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Administrative claims, EHRs, clinical registries, linked data systems [1] [30] | Provide real-world evidence on treatment patterns and outcomes | Data quality, completeness, granularity, and privacy concerns [1] |

| Risk Adjustment Methods | Prospective risk scores, concurrent risk scores [1] | Identify similar patients for comparative purposes; account for case mix | Choice between prospective vs. concurrent models depends on study design [1] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Matching, weighting, stratification, covariate adjustment [1] [29] | Balance measured confounders between treatment groups in observational studies | Requires comprehensive measurement of confounders; cannot address unmeasured confounding |

| Instrumental Variable Methods | Geographic variation, facility characteristics, distance to care [29] | Address unmeasured confounding in observational studies | Requires valid instrument associated with treatment but not outcome |

| Patient-Reported Outcome Measures | Quality of life, functional status, symptom burden | Capture outcomes meaningful to patients beyond clinical endpoints | Must be validated, responsive to change, and feasible for implementation |

Value Assessment Frameworks

CER operates within broader value assessment frameworks that help translate research findings into decisions about healthcare value. Organizations like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) provide structured approaches to evaluating the clinical effectiveness and comparative value of healthcare interventions [26] [31]. ICER's value framework forms "the backbone of rigorous, transparent evidence reports" that aim to help the United States evolve toward a health care system that provides sustainable access to high-value care for all patients [31]. These frameworks typically consider:

- Comparative clinical effectiveness: Net health benefit assessment based on CER evidence

- Long-term cost-effectiveness: Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), though note that the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is prohibited from using cost per QALY as a threshold [26]

- Potential budget impact: Assessment of short-term affordability and access challenges, with ICER's updated threshold being $821 million annually [31]

- Other elements of value: Considerations such as novelty, address of unmet needs, and reduction in uncertainty

CER Framework Ecosystem

Impact on Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The integration of CER into pharmaceutical research has profound implications for drug development, market access, and clinical practice.

Influence on Drug Development

CER principles are increasingly shaping earlier phases of drug development. Pharmaceutical companies are adopting comparative approaches earlier in clinical development to generate evidence that demonstrates relative effectiveness compared to standard of care, not just placebo [28]. This shift may influence trial design choices, including the selection of appropriate comparators, patient populations, and outcome measures that reflect real-world practice.

The focus on targeted therapeutics aligns with the CER question of "which treatment works best for whom." Development programs are increasingly incorporating biomarkers and patient characteristics that predict differential treatment response, enabling more personalized treatment approaches [28]. However, this also presents challenges in defining appropriate subpopulations and ensuring adequate sample sizes for meaningful comparisons.

Evidence Generation Throughout the Product Lifecycle

CER extends evidence generation beyond regulatory approval throughout the product lifecycle:

Pre-approval Phase: Traditional efficacy trials for regulatory approval, increasingly incorporating active comparators and diverse populations.

Early Post-Marketing Phase: Rapid generation of real-world evidence on comparative effectiveness, often through observational studies, to address evidence gaps from pre-approval trials [29].

Established Product Phase: Ongoing monitoring of comparative effectiveness as new alternatives enter the market and clinical practice evolves.

This lifecycle approach requires strategic evidence planning that anticipates the comparative evidence needs of different stakeholders—patients, clinicians, payers, and policymakers—across the product lifecycle [28].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Emerging Innovations in CER Methodology

The field of CER continues to evolve methodologically and conceptually. Novel data sources such as digital health technologies, patient-generated health data, and genomics are expanding the scope and granularity of evidence available for CER [1]. The development of advanced analytical techniques including machine learning and artificial intelligence offers new approaches to addressing confounding and identifying heterogeneous treatment effects in complex datasets.

The integration of clinical and economic data represents another frontier, though regulatory restrictions limit the use of certain economic measures in federal CER initiatives [26] [1]. The ongoing tension between population-level decision making and individualized care continues to drive methodological innovation in patient-centered outcomes research.

Implementation Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Several significant challenges remain in fully realizing the potential of CER in pharmaceutical research:

Communication Restrictions: Regulations place different communication restrictions on the pharmaceutical industry than on other health care stakeholders regarding CER, creating potential inequalities in information dissemination [28].

Individual vs. Population Application: The tendency to apply average results from CER to individuals presents challenges, as not every individual experiences the average result [28]. Implementation policies must accommodate flexibility while providing guidance.

Innovation Incentives: The impact of CER expectations on pharmaceutical innovation remains uncertain. In some cases, CER may increase development costs or decrease market size, while in others, better targeting of trial populations could result in lower development costs [28].

Stakeholder Engagement: Effective CER requires engagement of various stakeholders—including patients, clinicians, and policymakers—in the research process, which while difficult, makes research more applicable and improves patient decision making [26].

CER represents a fundamental shift in how evidence is generated and used in pharmaceutical research and healthcare decision-making. By focusing on comparative questions in real-world settings, CER provides the evidence necessary to improve healthcare value, control costs, and ensure patients receive the right treatments for their individual circumstances and preferences.

How to Conduct CER: A Deep Dive into RCTs, Observational Studies, and Evidence Synthesis

Within pharmaceutical research, Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) aims to provide evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of different interventions in real-world settings. The Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) serves as the foundational element of CER, providing the most robust evidence for causal inference regarding a drug's efficacy [32] [33]. As the scientific paradigm shifts from a pure efficacy focus toward value-based healthcare, the adaptation of traditional RCTs into more pragmatic designs has become essential for generating evidence that is not only scientifically rigorous but also directly applicable to clinical and policy decisions [34]. This whitepaper examines the position of RCTs as the gold standard for evidence and explores the pragmatic adaptations that enhance their relevance to CER.

RCTs as the Gold Standard: Core Principles and Methodologies

Defining Features and Historical Context

Randomized Controlled Trials are true experiments in which participants are randomly allocated to receive an investigational intervention, a different intervention, or no treatment at all [33]. The first modern RCT is widely recognized as the 1948 publication in the BMJ on the use of streptomycin in pulmonary tuberculosis [32]. The core principle, as articulated by Bradford Hill, is that by the random division of patients, the treatment and control groups are made alike in all respects except for the experimental therapy, thereby ensuring that any difference in outcome is due to the treatment itself [32].

The construction of a proper RCT design rests on three main features [32]:

- Control of Exposure: The researcher manages participants' exposure to the intervention.

- Random Allocation: Participants are randomly assigned to study groups.

- Temporal Precedence: The cause (intervention) precedes the effect (outcome).

Key Methodological Components

To safeguard against biases and ensure the validity of results, well-designed RCTs incorporate several key methodological components.

Table 1: Core Methodological Components of a Robust RCT

| Component | Description | Function in CER |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Participants are randomly allocated to experimental or control groups using a computerized sequence generator or similar method [35] [36]. | Reduces selection bias by balancing both known and unknown prognostic factors across groups, allowing the use of probability theory to assess treatment effects [32]. |

| Allocation Concealment | The process of ensuring that the person enrolling participants is unaware of the upcoming group assignment. | Prevents selection bias by thwarting any attempt to influence which group a participant enters based on knowledge of the next assignment. |

| Blinding (or Masking) | Participants and/or researchers are unaware of group assignments. "Single-blind" trials blind participants; "double-blind" trials blind both participants and researchers [36]. | Avoids performance and detection bias. Participants and researchers who are unblinded may act differently, potentially influencing the outcome or its measurement [36]. |

| Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis | All participants are analyzed in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned, regardless of the treatment they actually received [36]. | Preserves the benefits of randomization and provides a less biased estimate of the intervention's effectiveness in a real-world scenario where adherence can vary. |

The following workflow illustrates the typical stages of a rigorous RCT, from planning through to analysis:

The Evidence Hierarchy and Strengths of RCTs

In the hierarchy of research designs, RCTs reside at the top for evaluating therapeutic efficacy [32] [33]. A large, randomized experiment is the only study design that can guarantee that control and intervention subjects are similar in all known and unknown attributes that influence outcomes [32]. The primary strengths of RCTs include [36]:

- Minimized Bias: Randomization and blinding reduce the impact of confounding variables and researcher/participant biases.

- Causal Inference: The design allows for strong conclusions about causal relationships between an intervention and an outcome.

- High Internal Validity: The controlled nature of the experiment provides confidence that the results are due to the intervention itself.

The Evolution Toward Pragmatism in RCTs

Bridging the Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap

While traditional RCTs excel at establishing efficacy (whether an intervention can work under ideal conditions), they often face criticism for limited generalizability to routine clinical practice [35] [34]. This has led to the development of Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trials (pRCTs), which are designed to test whether an intervention does work in real-world settings [35].

Pragmatic trials are essential for CER as they directly compare clinically relevant alternatives in diverse practice settings and collect data on a wide range of health outcomes [34]. They harmonize efficacy with effectiveness, assisting decision-makers in prioritizing interventions that offer substantial public health impact [34].

Table 2: Traditional RCTs vs. Pragmatic RCTs (pRCTs)

| Characteristic | Traditional (Explanatory) RCT | Pragmatic RCT (pRCT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | Efficacy ("Can it work?") | Effectiveness ("Does it work in practice?") |

| Setting | Highly controlled, specialized research environments | Routine clinical or community settings |

| Participant Eligibility | Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria | Broad criteria, representative of the target patient population |

| Intervention Flexibility | Strictly protocolized, delivered by specialists | Flexible, integrated into routine care, delivered by typical healthcare providers |

| Comparison Group | Often placebo or sham procedure | Usual care or best available alternative |

| Outcomes | Laboratory measures or surrogate endpoints | Patient-centered outcomes (e.g., quality of life, functional status) |

The following diagram contrasts the core focuses of these two trial designs and their position on the efficacy-effectiveness spectrum:

Methodological Considerations for pRCTs

Designing a valid pRCT requires balancing real-world applicability with scientific rigor. Key methodological adaptations include [35]:

- Broad Eligibility Criteria: Minimizing exclusion criteria to ensure the study population reflects those who will receive the treatment in practice.

- Integration into Routine Care: Leveraging existing healthcare infrastructure, such as electronic health records (EHRs) and registry platforms, for participant recruitment, intervention delivery, and data collection.

- Cluster Randomization: Sometimes randomizing groups of individuals (e.g., clinics, geographic areas) rather than individuals themselves to avoid contamination and better assess system-level interventions.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes: Prioritizing outcomes that matter most to patients, such as quality of life, functional status, and the ability to work.

The Toddler Oral Health Intervention (TOHI) trial exemplifies this approach. It integrated oral health promotion into routine well-baby clinic care, used broad eligibility criteria, and employed dental hygienists as oral health coaches within community settings, demonstrating how a pRCT can be implemented within existing healthcare systems [35].

Quantitative Data and Challenges in RCTs

The High Cost of Evidence

RCTs, particularly in fields like neurology, are notoriously costly and time-intensive. They can take up to 15 years to complete, with costs ranging up to $2–5 billion for a single product to proceed through all phases of development up to market approval [32]. The median Research & Development cost per approved neurologic agent is close to $1.5 billion [32]. These figures underscore the immense financial investment required to generate the highest level of evidence for new pharmaceuticals.

Common Pitfalls and Limitations

Despite their strength, RCTs have inherent limitations and are prone to specific pitfalls [36]:

- Poor Recruitment and Retention: Difficulty in enrolling a representative sample can lead to selection bias and limit generalizability. High dropout rates can compromise the integrity of the results.

- Ethical and Feasibility Constraints: RCTs may not be appropriate, ethical, or feasible for all research questions, particularly in surgery or when investigating harmful exposures [33].

- Fragility of Results: Small and underpowered RCTs are common. The Fragility Index (FI) is a metric that quantifies how fragile a statistically significant result is; it indicates the number of events whose status would need to change from non-event to event to render a result non-significant [33]. A low FI suggests that the trial results are highly sensitive to minor changes in outcome data.

- Industry Sponsorship Bias: Approximately 70–80% of RCTs are industry-financed, which can create conflicts of interest and a bias toward publishing positive results [34].

Furthermore, the selection process in RCTs is rigorous. In some cases, such as recent trials on Alzheimer's disease, only about 15% of initially assessed patients may progress to the intention-to-treat analysis phase, raising questions about the applicability of results to the broader patient population seen in clinical practice [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RCTs

The successful execution of an RCT, whether traditional or pragmatic, relies on a suite of methodological and analytical "reagents."

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RCTs

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in RCTs |

|---|---|---|

| Computerized Randomization Sequence | Methodology | Generates an unpredictable allocation sequence, forming the foundation for unbiased group comparison [35]. |

| CONSORT Guidelines | Reporting | A set of evidence-based guidelines (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) to improve the quality and transparency of RCT reporting [32]. |

| Stratification Variables | Methodology | Variables (e.g., study site, disease severity) used during randomization to ensure balance between groups for known prognostic factors [35]. |

| Blinded Outcome Assessment | Methodology | Using independent assessors who are unaware of treatment allocation to measure outcomes, thereby reducing detection bias [35]. |

| Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Dataset | Data Analysis | A dataset where participants are analyzed in their originally assigned groups, preserving the benefits of randomization [36]. |

| Fragility Index (FI) | Statistical Analysis | A metric to assess the robustness of a statistically significant result, particularly useful for small trials with binary outcomes [33]. |

| Mixed Methods Integration | Analysis | Formal techniques (e.g., joint displays) for integrating quantitative trial data with qualitative data to explain variation in outcomes or understand implementation barriers [37]. |

The future of RCTs in pharmaceutical CER lies in the continued development and adoption of pragmatic methodologies. International collaborative networks, such as the PRIME-9 initiative across nine countries, are strengthening the pRCT concept by enabling the recruitment of larger, more diverse patient populations, sharing knowledge and resources, and overcoming ethical and regulatory barriers [34]. Furthermore, the integration of mixed methods—combining quantitative RCT data with qualitative research—holds great promise for generating deeper insights into why interventions work (or fail), for whom, and under what circumstances [37].

In conclusion, while the RCT remains the undisputed gold standard for establishing therapeutic efficacy, its evolution into more pragmatic and patient-centered designs is critical for answering the pressing questions of comparative effectiveness in real-world healthcare systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering both the core principles of the traditional RCT and the adaptive strategies of the pRCT is essential for generating evidence that is not only scientifically rigorous but also meaningful for clinical practice and health policy.