Comparative Drug Efficacy Studies: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions for Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of comparative drug efficacy studies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Drug Efficacy Studies: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions for Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of comparative drug efficacy studies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, from defining comparative effectiveness research (CER) to its role in clinical and policy decisions. The piece delves into advanced methodological approaches, including adjusted indirect comparisons and network meta-analyses, and addresses common challenges like confounding and evidentiary gaps. Finally, it explores regulatory trends and validation frameworks, highlighting how technological advances like AI and high-resolution analytics are shaping the future of evidence generation for novel therapeutics.

What is Comparative Effectiveness? Defining the Landscape for Drug Development

In the field of drug development and clinical research, two distinct but complementary paradigms guide the evaluation of medical interventions: traditional efficacy trials and comparative effectiveness research (CER) [1]. Efficacy trials ask, "Does this intervention work under ideal and controlled circumstances?" In contrast, CER asks, "How does this intervention compare to alternatives under real-world conditions of clinical practice?" [2]. Understanding the core principles, methodologies, and applications of each is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to generate evidence that is not only statistically sound but also clinically relevant and applicable to diverse patient populations [3].

Core Definitions and Purpose

Traditional Efficacy Trials

Efficacy trials, also known as explanatory trials, are designed to determine whether an intervention produces the expected result under ideal, highly controlled conditions [4]. The primary goal is to maximize internal validity—the certainty that any observed effect is indeed caused by the intervention being studied [1]. These trials are the cornerstone of the drug approval process, providing the initial proof-of-concept that an intervention is biologically active and efficacious.

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER)

The Institute of Medicine defines CER as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care" [5] [2]. Its purpose is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policymakers in making informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels [5]. CER focuses on external validity, or generalizability, seeking to answer the critical questions of "what works best, for whom, and under what circumstances?" [3] [2].

Comparative Analysis: Key Dimensions of Difference

The distinctions between efficacy trials and CER manifest across several key dimensions of study design and execution. The following table summarizes these fundamental differences.

| Dimension | Traditional Efficacy Trial | Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Question | Does it work under ideal conditions? [1] [6] | Does it work in real-world practice compared to alternatives? [2] |

| Primary Goal | Maximize internal validity; establish causal effect [4] [1] | Maximize external validity (generalizability); inform clinical/policy decisions [4] [5] |

| Typical Comparator | Placebo or no treatment [1] [6] | Active treatment or usual care [1] [6] |

| Patient Population | Highly selected, homogeneous; strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [1] | Heterogeneous, representative of clinical practice; few exclusion criteria [1] |

| Study Setting & Intervention | Ideal, resource-intensive settings; strictly standardized protocol [1] | Routine clinical settings; flexible application of intervention permitted [1] [6] |

| Data Analysis | Intention-to-treat; often includes per-protocol analysis [1] | Intention-to-treat; methods to handle confounding (e.g., propensity scores) [5] [2] |

| Outcomes Measured | Often a single primary outcome (e.g., biomarker) [3] | A broad range of benefits and harms relevant to patients [5] [3] |

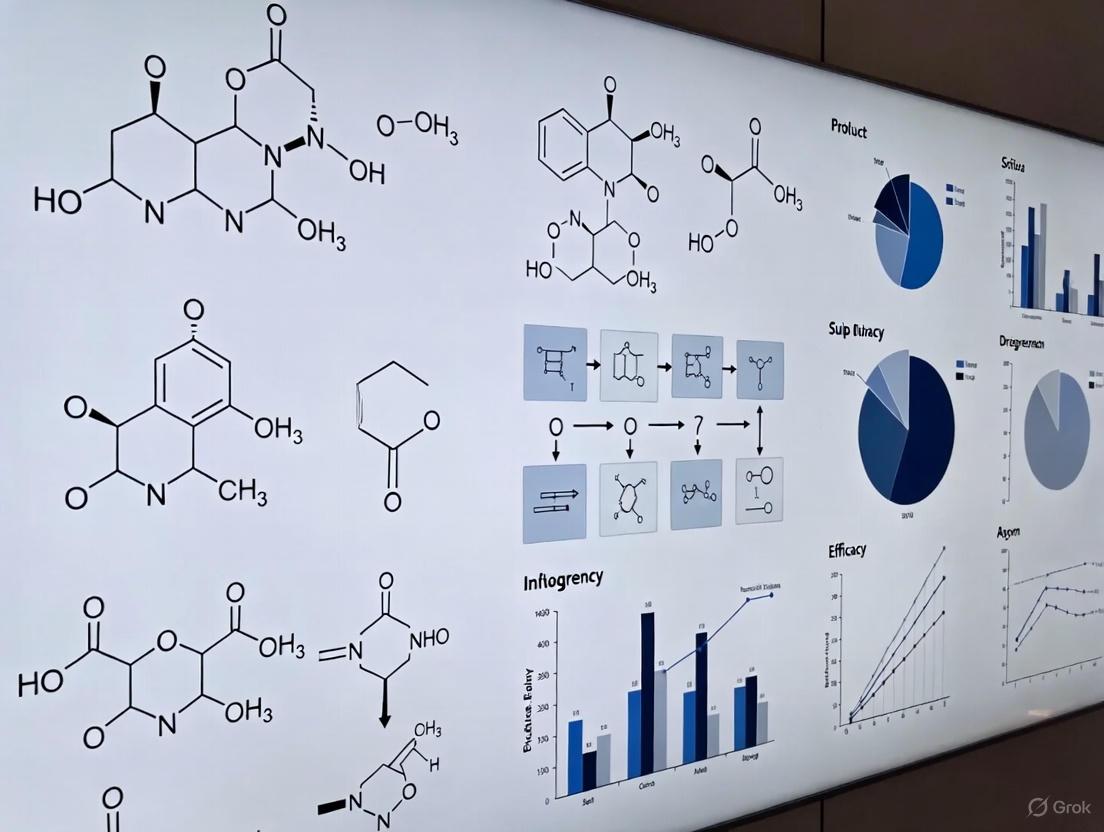

This continuum of research approaches can be visualized as a spectrum from highly controlled to highly pragmatic studies.

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Methodologies in Traditional Efficacy Trials

The randomized controlled trial (RCT), particularly the double-blind, placebo-controlled design, is considered the gold standard for efficacy evaluation [5] [1].

- Randomization and Blinding: Participants are randomly assigned to the intervention or control group to eliminate selection bias. Blinding of participants, investigators, and outcome assessors prevents differential treatment and assessment.

- Strict Protocols: The intervention is delivered in a highly standardized way, including fixed dosing, timing, and concomitant restrictions on other treatments. This ensures that any witnessed effect can be attributed to the intervention of interest [1].

- Highly Experienced Providers: Trials are often conducted at specialized research centers with providers who receive specific training on the protocol, ensuring consistent, high-quality delivery of the intervention [1].

Methodologies in Comparative Effectiveness Research

CER employs a broader toolkit, including both experimental and observational methods, to answer questions that are difficult to address with traditional efficacy trials alone [5].

Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trials

Pragmatic trials relax the strict rules of traditional RCTs to increase relevance to routine practice [5]. Key features include:

- Comparison to Usual Care: The new intervention is compared to the current standard of care rather than a placebo [1].

- Flexible Intervention Protocols: Providers are allowed flexibility in dosing, timing, and co-therapy to mimic real-world clinical decision-making [1].

- Broad Eligibility Criteria: Few exclusion criteria are applied to enroll a patient population that reflects the heterogeneity of clinical practice, including patients with comorbidities and those on multiple medications [1].

Observational Studies

Observational studies compare outcomes between patients who receive different interventions through clinical practice, not investigator randomization [5] [2]. These can be prospective or retrospective and are particularly valuable for studying rare diseases, long-term outcomes, and situations where RCTs are unethical or impractical [5] [2]. A major challenge is selection bias, which occurs when intervention groups differ in characteristics associated with the outcome [5]. To mitigate this, CER employs specific analytical techniques, detailed in the workflow below.

Evidence Synthesis

CER also includes methodologies for synthesizing existing evidence [5] [2].

- Systematic Reviews: A critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular clinical issue using a predefined, organized method [2].

- Meta-Analysis: A quantitative pooling of data from multiple studies to provide a more precise estimate of effect size [2].

- Decision and Cost-Effectiveness Modeling: These models use data from various sources to make quantitative estimates of expected outcomes, which can be tailored to specific patient characteristics and include economic outcomes [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Analytical Solutions

In the context of CER, the essential "reagents" are not just biochemicals but, more critically, methodological and data solutions required to conduct robust analyses.

| Tool / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Real-World Data (RWD) | Data derived from electronic health records (EHRs), claims and billing data, and disease registries that provide information on health status and care delivery in routine practice [7]. |

| Propensity Score Analysis | A statistical technique that estimates the probability of a patient receiving a treatment given their observed covariates. It is used to create balanced comparison groups in observational studies, mimicking randomization [5] [2]. |

| Risk Adjustment Models | Actuarial tools that use claims or medical records data to calculate a risk score for a patient based on their health conditions. This allows for calibration when comparing outcomes across groups with different baseline risks [2]. |

| Instrumental Variables | An analytic method used to address unmeasured confounding in observational studies by using a variable that is correlated with the treatment assignment but not directly with the outcome [5]. |

Efficacy trials and comparative effectiveness research are not in opposition but exist on a continuum essential for a complete evidence generation ecosystem [4] [1]. Efficacy trials provide the initial, critical proof of a causal biological effect under ideal conditions, forming the foundation for regulatory approval. CER builds upon this foundation by determining how efficacious interventions perform when translated into the complex, heterogeneous environment of real-world clinical practice compared to existing alternatives. For drug development professionals and researchers, a strategic approach that appreciates the strengths and applications of both paradigms is key to developing not only new drugs, but the necessary evidence to ensure they deliver meaningful outcomes to the diverse patients and health systems they are intended to serve.

The Critical Role of CER in Informing Clinical Practice and Health Policy

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) is a crucial methodology for providing evidence on the "effectiveness, benefits, and harms of different treatment options" [8]. It directly compares drugs, medical devices, tests, surgeries, or ways to deliver health care to determine which interventions work best for specific patients and circumstances [8]. This evidence is vital for building a more evidence-informed and patient-centered health system [9].

Defining Patient-Centered Comparative Effectiveness Research

Unlike abstract medical puzzles, patient-centered CER addresses pressing, everyday questions faced by patients, caregivers, and clinicians. It moves beyond studying treatments in isolation to perform head-to-head evaluations of at least two different, real-world approaches to care [9].

This research is characterized by three defining principles [9]:

- Patient-Centered: It focuses on outcomes that matter most to patients, such as quality of life, symptom relief, and day-to-day functioning, rather than solely on clinical metrics.

- Patient-Engaged: It actively involves patients, caregivers, and the broader healthcare community throughout the entire research process.

- Practical and Applicable: It generates findings that can be readily adopted in real-world clinical practice nationwide.

CER evidence can be generated through systematic reviews of existing evidence or through the conduct of new studies or trials that directly compare effective approaches [8].

Key Applications and Impact on Decision-Making

CER produces practical evidence that directly informs decisions at multiple levels, from the clinic to national policy. The table below summarizes its impact on different stakeholder groups.

Table 1: Impact of CER on Clinical and Policy Decision-Making

| Stakeholder | Key Decisional Dilemmas Addressed by CER | Impact of CER Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Patients & Clinicians | Should I try antibiotics instead of surgery for appendicitis? What is the most effective way to manage asthma long-term? Is a low dose of aspirin as safe and effective as a higher one for preventing heart attacks? [9] | Empowers patients with information to make care decisions aligned with their individual values, preferences, and life circumstances [9]. |

| Health Policy Makers | Determining which interventions represent the best value for healthcare investments. Allocating resources for public health programs. | Provides evidence on the comparative clinical effectiveness of available interventions, supporting the development of evidence-informed policies and coverage decisions [10] [8]. |

| Researchers & Health Systems | Identifying critical gaps in evidence for common clinical decisions. Improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery. [8] [11] | Informs the research agenda and provides the tools and real-world evidence needed to improve the effectiveness of care delivery at local, state, and national levels [8]. |

Methodological Frameworks and Funding Landscape

A prominent driver of CER in the United States is the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which funds high-quality, patient-centered CER [10] [9]. PCORI emphasizes large-scale randomized controlled trials that address critical decisional dilemmas where insufficient evidence exists [10].

A key funding mechanism is the Phased Large Awards for Comparative Effectiveness Research (PLACER) program. This program anticipates that complex research projects will require two distinct phases of funding [10]:

- Feasibility Phase: This initial phase supports study refinement, infrastructure establishment, patient and stakeholder engagement, and feasibility testing of study operations. Investigators may request up to

$2 millionin direct costs for this phase, which can last up to 18 months [10]. - Full-Scale Study Phase: Continuation to this second phase is contingent on achieving specific milestones from the feasibility phase. It supports the full implementation of the trial, with requests of up to

$20 millionin direct costs for a duration of up to five years [10].

A critical expectation for PCORI-funded research is the meaningful engagement of patients and stakeholders, guided by PCORI's Foundational Expectations for Partnerships in Research [10]. Furthermore, due to the scale and complexity of these trials, applications must include shared trial leadership by a Data Coordinating Center to provide an independent role in analytical, statistical, and data management aspects [10].

Table 2: Key Elements of a PCORI PLACER Research Project

| Component | Description & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Trial Design | Individual-level or cluster randomized controlled trials of significant scale and scope [10]. |

| Interventions | Compares interventions that already have robust efficacy evidence and are in current use, including both clinical and delivery system interventions [10]. |

| Engagement | Active involvement of patients and stakeholders along a continuum from input to shared leadership, guided by PCORI's Foundational Expectations [10]. |

| Study Leadership | Requires a shared leadership model with an independent Data Coordinating Center [10]. |

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow and logical progression of a two-phase PLACER trial, from application to dissemination.

Implementation in Practice: Case Examples from Research Institutions

Academic and research institutions play a critical role in conducting CER and translating evidence into practice. Their work demonstrates the real-world application and scope of this research.

- Weill Cornell Medicine: The Division of Comparative Effectiveness and Outcomes Research pursues research on medications, medical devices, and procedures. Key areas include the comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for substance use disorder, pharmacoepidemiology of diabetes medications, and cardiovascular medical device safety monitoring [11]. This work often involves analyzing large datasets such as Medicare claims data and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data [11].

- University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC): The CER program aims to bring together faculty to identify knowledge gaps in clinical care effectiveness. Its goals are to conduct systematic reviews, analyze large datasets and clinical trials, and design new comparative effectiveness trials to improve the translation of research into practice and policy [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful CER relies on a combination of data resources, methodological expertise, and stakeholder partnerships. The following table details key "research reagents" and their functions in the context of conducting comparative effectiveness studies.

Table 3: Key Resources for Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Item/Resource | Function in CER |

|---|---|

| Large Administrative Datasets (e.g., Medicare data, SEER-Medicare, State discharge data) [11] | Provides real-world data on treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and patient outcomes across diverse populations and care settings for observational analyses. |

| Clinical Registries [11] | Offers detailed, prospectively collected clinical data on specific patient populations or procedures, enabling robust comparison of devices, surgeries, and long-term outcomes. |

| Systematic Review Methodology [8] | Allows for the synthesis of existing evidence from multiple studies to identify what is already known about the comparative effectiveness of interventions and to pinpoint critical evidence gaps. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Framework (e.g., PCORI's Foundational Expectations) [10] | Ensures that the research addresses questions and outcomes that are important to patients and clinicians, enhancing the relevance and uptake of study findings. |

| Data Coordinating Center (DCC) [10] | Provides independent expertise and infrastructure for data management, statistical analysis, and study leadership, ensuring scientific rigor and integrity in large-scale trials. |

| Qualitative Research Methods | Complements quantitative data by providing deep insight into patient preferences, experiences, and potential barriers to implementing evidence in clinical practice. |

In the realm of drug development and healthcare delivery, clinical uncertainty poses a significant challenge to achieving optimal patient outcomes and resource allocation. This uncertainty often stems from a lack of direct, head-to-head comparative evidence on the efficacy and safety of therapeutic alternatives. Such evidence is crucial for researchers, clinicians, health technology assessment bodies, and payers to make informed decisions [12]. The traditional drug development and regulatory paradigm, which often relies on placebo-controlled trials, frequently fails to generate this needed comparative data at the time of market entry [13]. This gap complicates the determination of a new drug's place in therapy and its relative value compared to existing standards of care.

The growing complexity of therapeutic landscapes, exemplified by areas like type 2 diabetes and obesity where multiple drug classes with different mechanisms of action are available, intensifies this challenge [12] [14]. Consequently, advanced methodological frameworks for generating and synthesizing comparative evidence are becoming critical "key drivers" in addressing clinical uncertainty and optimizing healthcare value. This guide explores these frameworks, detailing their experimental protocols, applications, and the essential tools that empower researchers in this endeavor.

Methodological Frameworks for Comparative Efficacy Research

When direct head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are absent or impractical, several statistical methodologies can be employed to estimate comparative treatment effects. The choice of method depends on the available evidence, the research question, and the underlying assumptions that can reasonably be made about the similarity of different study populations.

Comparative Methodologies Overview

| Method | Core Principle | Key Assumption | Primary Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head-to-Head RCT [12] | Direct, randomized comparison within a single trial. | Randomization ensures group comparability. | Gold standard; minimizes confounding and bias. | Expensive, time-consuming, not always available. |

| Adjusted Indirect Comparison (AIC) [12] | Indirectly compares Drug A vs. Drug B via their effects against a common comparator (Drug C). | The studies involved are similar in design and patient population. | Preserves randomization from the original trials; more reliable than naïve comparison. | Increased statistical uncertainty; relies on a connected evidence network. |

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) [14] [13] | Simultaneously incorporates all available direct and indirect evidence within a connected network of treatments. | Consistency between direct and indirect evidence within the network. | Maximizes use of all available data; reduces uncertainty; allows ranking of multiple treatments. | Complex statistical models; requires careful assessment of network consistency and transitivity. |

| Single-Arm Trial (SAT) with External Controls [15] | Compares outcomes from a single treatment arm to a control group derived from historical or external data. | The trial population and the external control population are prognostically similar. | Practical for rare diseases or urgent unmet needs where RCTs are infeasible. | Highly susceptible to bias from population differences, changes in care, and outcome assessment. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and evidence pathways that connect these different methodological approaches.

Regulatory Evolution and Current Applications

The regulatory landscape for accepting comparative evidence is rapidly evolving, reflecting growing confidence in advanced analytical methods. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently signaled a significant shift in its requirements for demonstrating biosimilarity of therapeutic protein products.

Case Study: FDA's Updated Approach to Biosimilarity

The FDA's 2025 draft guidance proposes that for certain well-characterized therapeutic protein products, a comparative efficacy study (CES) may no longer be routinely required. This "streamlined approach" is predicated on three conditions being met [16] [17]:

- The products are highly purified and can be well-characterized using advanced analytical methods.

- The relationship between quality attributes and clinical efficacy is well understood.

- Any residual uncertainty can be addressed by a human pharmacokinetic (PK) similarity study and a robust immunogenicity assessment.

This shift underscores that for these products, a comparative analytical assessment (CAA) is now considered "generally more sensitive than a CES to detect differences between two products" [17]. This represents a major departure from the 2015 guidance and highlights the role of advanced technology in reducing clinical uncertainty. A CES may still be necessary for products with limited structural characterization, such as some locally acting products [17].

Case Study: Network Meta-Analysis in Obesity Pharmacotherapy

A 2025 systematic review and network meta-analysis published in Nature Medicine exemplifies the application of these methods to resolve uncertainty in a complex therapeutic area [14]. The study evaluated the efficacy and safety of six pharmacological treatments for obesity in adults, using percentage of total body weight loss (TBWL%) as the primary endpoint.

Key Quantitative Findings from Obesity Pharmacotherapy NMA [14]

| Pharmacological Treatment | Number of RCTs (Comparisons) | Total Body Weight Loss (%) vs. Placebo at Endpoint (Mean) | Proportion of Patients Achieving ≥15% TBWL vs. Placebo (Odds Ratio) | Key Safety and Complication Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide | 6 | >10% | Highest odds | Remission of obstructive sleep apnea and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. |

| Semaglutide | 14 | >10% | Very high odds | Reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and pain in knee osteoarthritis. |

| Liraglutide | 11 | 5-10% | Moderate odds | Effective weight loss, superior to orlistat. |

| Phentermine/Topiramate | 2 | 5-10% | Moderate odds | Not specified in snippet. |

| Naltrexone/Bupropion | 5 | 5-10% | Moderate odds | Not specified in snippet. |

| Orlistat | 22 | <5% | Not significant | Not specified in snippet. |

Experimental Protocol for the NMA [14]:

- Data Sources & Search: Systematic search of Medline and Embase databases up to January 31, 2025.

- Eligibility Criteria: Included RCTs comparing the OMMs of interest versus placebo or an active comparator in adults with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²). The primary endpoint was TBWL% at the study's end.

- Data Extraction & Quality Assessment: Two reviewers independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane tool.

- Statistical Analysis - NMA Model: A frequentist or Bayesian random-effects NMA model was used to synthesize the data. The model allowed for the combination of direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (via common comparators like placebo) to estimate pooled effect sizes for all pairwise comparisons.

- Inconsistency Assessment: Statistical tests (e.g., Higgins H-value) were used to check for inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence within the network.

- Certainty of Evidence: The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework was likely applied to rate the confidence in the estimated effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully executing comparative efficacy studies, particularly those involving complex syntheses like NMA, requires a suite of methodological and material resources.

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Efficacy Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Implementation Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) Framework [14] | Assesses the certainty (quality) of evidence in a systematic review or NMA, rating it as high, moderate, low, or very low. | Used by the EASO to develop their treatment algorithm based on the obesity NMA, informing the strength of recommendations. |

R (with netmeta/gemtc packages) or Stata |

Statistical software environments capable of performing frequentist and Bayesian NMA models, respectively. | Essential for the complex statistical computations required to combine direct and indirect evidence and output league tables and forest plots. |

| PRISMA-NMA Checklist | Reporting guideline ensuring transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews incorporating NMA. | Improves the reproducibility and reliability of published NMA studies. |

| Prospective NMA Protocol [13] | A pre-specified plan for a future NMA, developed before the individual trials are conducted. | Aims to reduce heterogeneity and bias by aligning trial designs (populations, outcomes, definitions) across different drug development programs. |

| Indirect Comparison Software | Dedicated tools for performing adjusted indirect comparisons. | The Canadian Agency for Drug and Technologies in Health (CADTH) provides simple software for this purpose [12]. |

The workflow for planning and conducting a prospective NMA, which is increasingly advocated to strengthen comparative evidence at drug approval, can be visualized as follows.

Addressing clinical uncertainty is a fundamental driver for enhancing the value delivered by healthcare systems. As demonstrated, robust methodological frameworks like Adjusted Indirect Comparisons and Network Meta-Analysis provide powerful tools for generating comparative efficacy evidence when direct head-to-head trials are lacking. The ongoing evolution of regulatory science, embracing advanced analytics and sophisticated evidence synthesis, is crucial for streamlining drug development and ensuring that clinicians, patients, and payers have the information needed to make optimal choices. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these methodologies and the associated toolkit is no longer a niche specialty but a core competency for navigating the complex therapeutic landscapes of the future and ultimately optimizing healthcare value.

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) has become a cornerstone of modern drug development and healthcare decision-making. Defined by the Institute of Medicine as "the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care" [2], CER provides the critical evidence base that informs decisions by patients, clinicians, policymakers, and payers. In the current regulatory and reimbursement landscape, the demand for robust comparative evidence has intensified, driven by the need to demonstrate not just efficacy and safety, but also value relative to existing therapeutic alternatives. This evolution reflects a broader shift toward a more efficient, transparent, and patient-centered healthcare system where resource allocation decisions are increasingly guided by structured comparisons of which interventions work best, for whom, and under what circumstances [2].

The regulatory environment is simultaneously adapting to this demand. Recent guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledges that for certain products, such as biosimilars, a comparative analytical assessment can be more sensitive than a comparative clinical efficacy study for detecting product differences [18] [19]. This "streamlined approach" can reduce development time by 1-3 years and save an average of $24 million per biosimilar program, significantly lowering barriers to market entry and competition [19]. However, for novel chemical entities and innovative therapies, well-designed comparative studies remain pivotal for regulatory approval, reimbursement negotiations, and clinical adoption. This article examines the methodologies, regulatory framework, and practical applications of CER, providing a guide for generating the high-quality comparative evidence demanded in today's evidence-based healthcare environment.

Methodological Frameworks for Comparative Effectiveness Research

CER employs a spectrum of study designs, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications. Understanding these methodologies is essential for designing rigorous comparisons that yield valid, actionable evidence.

Core Research Designs

The three primary methodological approaches for CER are systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and observational studies [2].

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: A systematic review involves a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies addressing a particular clinical issue using an organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular topic with specific criteria. When it includes a quantitative pooling of data, it becomes a meta-analysis [2]. This approach is exemplified by a 2025 network meta-analysis in Nature Medicine that evaluated the efficacy and safety of six pharmacological treatments for obesity by synthesizing data from 56 randomized controlled trials involving 60,307 patients [14]. Such analyses provide the highest level of evidence by synthesizing all available research, though their quality depends entirely on the rigor of the underlying primary studies.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): RCTs represent the gold standard for clinical research where participants are randomly assigned to two or more groups that differ only in the intervention being studied. The groups are followed for predetermined outcomes, and results are compared using statistical analyses [2]. RCTs are ideal for research requiring high certainty about causal inference, though they can be expensive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming. They may also lack generalizability due to strict inclusion criteria and controlled settings. For comparative evidence, RCTs can be designed as superiority, non-inferiority, or equivalence trials, providing direct head-to-head evidence of product performance.

Observational Studies: In observational studies, participants are not assigned to treatments at random. Instead, treatments are chosen by patients and their physicians in real-world practice. These studies can be prospective (following patients forward in time after creating a study protocol) or retrospective (using existing data sources like claims data or medical records where both interventions and outcomes have already occurred) [2]. Observational studies are typically faster and more cost-efficient than RCTs and are particularly valuable for studying rare diseases, long-term outcomes, and treatment effects in diverse patient populations. However, they are more susceptible to confounding bias, as treatment assignment is not random.

Advanced Methodological Innovations

Recent methodological advances are expanding the capacity of CER to address increasingly complex clinical questions. Machine learning and novel statistical approaches are enabling more sophisticated analysis of real-world data and complex treatment regimens.

The METO framework is one such innovation, designed specifically to estimate treatment effects of multiple drug combinations on multiple outcomes. This framework addresses key challenges in hypertension management, where patients often require combination therapy. METO uses multi-treatment encoding to handle detailed information on drug combinations and administration sequences, and it explicitly differentiates between effectiveness and safety outcomes during prediction [20]. To address confounding bias inherent in observational data, METO employs an inverse probability weighting method for multiple treatments, assigning each patient a balance weight derived from their propensity score for receiving different drug combinations [20]. When evaluated on a real-world dataset of over 19 million patients with hypertension, this approach demonstrated a 6.4% average improvement in the precision of estimating heterogeneous treatment effects compared to existing methods [20].

Another innovative approach combines machine learning with comparative effectiveness research techniques to investigate clinical pathways. A 2025 study applied this method to examine pharmacotherapy pathways for veterans with depression, using process mining and machine learning to generate treatment pathways and instrumental variable analysis to balance both observable and unobservable patient and provider characteristics [21]. This study produced a counterintuitive finding that contradicts the "start low, go slow" adage for antidepressant titration, instead showing that ramping up the dose faster had a statistically significant positive effect on engagement in care [21].

Addressing Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies

A critical challenge in observational CER is addressing selection bias and confounding, which occur when patient characteristics influence both treatment assignment and outcomes. Two primary statistical tools used to mitigate these issues are:

Risk Adjustment: An actuarial tool that identifies a risk score for a patient based on conditions identified via claims or medical records. Risk adjustment can be used to calibrate payments to health plans based on the relative health of the covered population and to identify similar types of patients for comparative purposes [2]. Prospective risk adjusters use historical data to predict future costs, while concurrent models use current data to explain present costs.

Propensity Score Matching: This method involves calculating the conditional probability of a patient receiving a specific treatment given their observed characteristics. Patients in different treatment groups are then matched based on their propensity scores, creating balanced comparison groups that more closely resemble the balance achieved through randomization [2].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a robust comparative effectiveness study using real-world data, incorporating these methods to address confounding:

Regulatory Landscape and Recent Developments

The regulatory environment for comparative evidence is evolving rapidly, with significant implications for drug development strategies and evidence requirements.

FDA Initiatives and Guidances

The FDA has recently proposed significant updates to its evidentiary standards for certain product categories, particularly biosimilars. In a 2025 draft guidance, the FDA outlined an "updated framework" that recognizes the superior sensitivity of comparative analytical assessments over comparative clinical efficacy studies for detecting differences between proposed biosimilars and their reference products [18] [19]. Under this new framework, if comparative analytical data strongly supports biosimilarity, "an appropriately designed human pharmacokinetic similarity study and an assessment of immunogenicity may be sufficient to evaluate whether there are clinically meaningful differences" without a separate comparative efficacy trial [19]. This streamlined approach applies when the products are manufactured from clonal cell lines, are highly purified, can be well-characterized analytically, and when the relationship between quality attributes and clinical efficacy is well understood [19].

Other significant regulatory changes affecting clinical research include:

FDAAA 801 Final Rule Updates (2025): These changes tighten clinical trial reporting requirements by shortening results submission timelines from 12 to 9 months after the primary completion date, expanding the definition of applicable clinical trials, requiring public posting of informed consent documents, and implementing real-time public notifications of noncompliance with enhanced penalties reaching $15,000 per day for continued violations [22].

ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice: The recently finalized guidance introduces more flexible, risk-based approaches and embraces modern innovations in trial design, conduct, and technology [23] [24].

Focus on Diverse Enrollment: Regulatory agencies are increasing their emphasis on representative participant enrollment in clinical trials to ensure treatments are effective across diverse populations [24].

International Regulatory Harmonization

Globally, regulatory agencies are moving toward greater harmonization of CER standards and requirements:

Health Canada: In 2025, proposed significant revisions to its biosimilar approval guidance, notably removing the routine requirement for Phase III comparative efficacy trials and instead relying on analytical comparability plus pharmacokinetic, immunogenicity, and safety data [23].

European Medicines Agency (EMA): Currently developing new reflection papers on patient experience data and updated guidelines for specific therapeutic areas including hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis, emphasizing the growing importance of patient-centered outcomes in comparative assessment [23].

China's NMPA: Recently implemented revisions to clinical trial regulations aimed at accelerating drug development and shortening trial approval timelines by approximately 30%, including allowing adaptive trial designs with real-time protocol modifications under stricter safety oversight [23].

The following diagram summarizes the evolving regulatory pathways for generating comparative evidence:

Case Study: Comparative Evidence in Obesity Pharmacotherapy

A recent comprehensive network meta-analysis published in Nature Medicine provides an exemplary case study of how rigorous comparative evidence can inform clinical practice and regulatory decisions [14]. This analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of six pharmacological treatments for obesity in adults—orlistat, semaglutide, liraglutide, tirzepatide, naltrexone/bupropion, and phentermine/topiramate—based on 56 randomized controlled trials enrolling 60,307 patients.

Quantitative Efficacy Outcomes

The primary endpoint was percentage of total body weight loss (TBWL%) at study endpoint. All medications showed significantly greater weight loss compared to placebo, with important differences between agents [14].

Table 1: Efficacy Outcomes of Obesity Pharmacotherapies from Network Meta-Analysis [14]

| Medication | TBWL% at Endpoint (vs. Placebo) | ≥5% TBWL Achievement (Odds Ratio) | ≥10% TBWL Achievement (Odds Ratio) | ≥20% TBWL Achievement (Odds Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide | >10% | 14.2 [9.8–20.6] | 33.8 [18.4–61.9] | 18.9 [12.1–29.5] |

| Semaglutide | >10% | 12.5 [8.6–18.2] | 21.3 [14.8–30.6] | 9.8 [6.9–13.9] |

| Liraglutide | 7.5% [6.2–8.9] | 8.9 [6.1–13.0] | 6.6 [4.8–9.1] | 3.2 [2.3–4.4] |

| Phentermine/Topiramate | 8.1% [6.9–9.3] | 9.1 [6.2–13.4] | 7.1 [5.1–9.9] | 3.8 [2.7–5.4] |

| Naltrexone/Bupropion | 6.5% [5.3–7.7] | 7.4 [5.0–10.9] | 5.2 [3.7–7.3] | 2.5 [1.8–3.5] |

| Orlistat | 3.5% [2.9–4.1] | 3.1 [2.5–3.8] | 2.2 [1.8–2.7] | 1.5 [1.2–1.9] |

Additional Clinical Benefits and Safety Profiles

Beyond weight loss, the analysis documented important differences in obesity-related complications. Tirzepatide and semaglutide demonstrated normoglycemia restoration, remission of type 2 diabetes, and reduction in hospitalization due to heart failure [14]. Semaglutide was particularly effective in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events and pain in knee osteoarthritis, while tirzepatide showed significant benefits in remission of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis [14].

The analysis also provided crucial insights into long-term weight management, finding that discontinuation of medications typically led to significant weight regain. After 52 weeks of treatment, discontinuation of semaglutide and tirzepatide resulted in regain of 67% and 53% of lost weight, respectively, highlighting the chronic nature of obesity management and the need for continued therapy [14].

Conducting rigorous comparative effectiveness research requires specialized methodological expertise and analytical tools. The following table outlines key components of the CER methodological toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools & Methods | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Administrative Claims Data, Electronic Health Records, Disease Registries, Patient-Reported Outcomes | Provide real-world clinical data on treatment patterns, outcomes, costs, and patient experiences in diverse populations [20] [2]. |

| Statistical Methods | Propensity Score Matching, Inverse Probability Weighting, Instrumental Variable Analysis, Risk Adjustment | Address confounding and selection bias in observational studies by balancing comparison groups on measured characteristics [20] [2]. |

| Advanced Modeling | Network Meta-Analysis, Machine Learning Algorithms (e.g., METO framework), Multi-Treatment Encoding | Enable comparison of multiple interventions simultaneously and model complex treatment pathways and combinations [14] [20]. |

| Causal Inference Frameworks | Potential Outcomes Framework, Structural Equation Modeling, Marginal Structural Models | Provide formal mathematical frameworks for estimating causal treatment effects from observational data [20]. |

| Software & Computing | R, Python, SAS, Stata with specialized packages for causal inference | Implement complex statistical analyses and machine learning models for treatment effect estimation [25]. |

The demand for robust comparative evidence in the regulatory and reimbursement context will continue to intensify as healthcare systems worldwide face increasing pressure to demonstrate value and optimize outcomes. The field of comparative effectiveness research is rapidly evolving, with several key trends shaping its future trajectory. Methodological innovations in machine learning, causal inference, and real-world data analysis are expanding the scope and rigor of comparative evidence [20] [21]. Regulatory modernization efforts are creating more efficient pathways for evidence generation, particularly for biosimilars and follow-on products [18] [19] [23]. Transparency mandates are ensuring that comparative evidence is publicly accessible to inform decision-making by all stakeholders [22]. Finally, global harmonization of regulatory standards is facilitating more efficient drug development programs across international markets [23] [24].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering the principles and practices of comparative effectiveness research is no longer optional—it is essential for demonstrating product value in an increasingly competitive and evidence-driven healthcare marketplace. By employing rigorous methodologies, adapting to evolving regulatory expectations, and leveraging new sources of data and analytical approaches, the research community can generate the high-quality comparative evidence needed to inform treatment decisions, guide resource allocation, and ultimately improve patient outcomes across diverse populations and clinical contexts.

Beyond Head-to-Head Trials: Advanced Methodologies for Comparative Analysis

In the field of drug development and comparative effectiveness research, head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represent the most rigorous methodological approach for directly comparing the efficacy and safety of therapeutic interventions. These trials, characterized by the random allocation of participants to different active treatments, provide the most unbiased estimates of relative treatment effects by minimizing confounding through balanced distribution of both known and unknown prognostic factors [26] [27]. Unlike placebo-controlled trials, which primarily establish absolute efficacy, head-to-head comparisons offer clinicians, researchers, and health policy makers critical evidence for making informed decisions between multiple available treatment options [12].

The primacy of head-to-head RCTs stems from their ability to establish causal inference through experimental design. When properly executed with adequate blinding, allocation concealment, and follow-up, these trials deliver high internal validity, providing a robust foundation for clinical practice guidelines and health technology assessments [28] [27]. Despite this respected position, head-to-head RCTs face significant practical limitations including ethical constraints, resource intensiveness, and feasibility challenges, particularly when comparing multiple treatment options across diverse patient populations [12] [29]. This article examines the methodological strengths, limitations, and evolving role of head-to-head RCTs within the broader context of evidence generation for therapeutic interventions.

Methodological Foundations and Strengths of Head-to-Head RCTs

Core Design Principles

The fundamental strength of head-to-head RCTs lies in their experimental design, which incorporates random assignment, prospective data collection, and controlled implementation of interventions. Randomization serves as the cornerstone of this methodology, statistically equating treatment groups with respect to both measured and unmeasured baseline characteristics [26] [27]. This process effectively minimizes selection bias and mitigates the influence of confounding variables that often plague observational comparative studies [28].

The preservation of randomization ensures that differences in outcomes can be attributed to the treatments being compared rather than extraneous factors. As Saldanha et al. explain, "The randomization of study participants to treatment and comparator groups, when allocation is concealed, minimizes selection bias" and "helps ensure that the study groups are comparable with respect to known and unknown baseline prognostic factors" [26]. This protection against confounding establishes a firmer foundation for causal conclusions about relative treatment effects.

Advantages Over Alternative Comparison Methods

Head-to-head RCTs provide distinct advantages over indirect comparison methods. While statistical approaches such as adjusted indirect comparisons and mixed treatment comparisons can provide valuable information when direct evidence is lacking, they rely on the untestable assumption that study populations across different trials are sufficiently similar [12]. Naïve direct comparisons that simply contrast results across different trials "break the original randomization and are subject to significant confounding and bias because of systematic differences between or among the trials being compared" [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Methodological Approaches for Treatment Comparisons

| Methodological Approach | Key Features | Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head-to-Head RCT | Direct random assignment to active treatments; prospective data collection | Preserves randomization; minimizes confounding; high internal validity | Resource intensive; may lack generalizability; ethical constraints |

| Adjusted Indirect Comparison | Uses common comparator to link treatments across separate trials | More valid than naïve approaches; accepted by some regulatory bodies | Uncertainty from summing statistical errors; relies on similarity assumption |

| Naïve Direct Comparison | Simple contrast of results from different trials | Easily performed; requires no complex statistics | Severely confounded; breaks randomization; potentially misleading |

| Mixed Treatment Comparison | Bayesian network meta-analysis incorporating all available evidence | Incorporates all relevant data; reduces uncertainty | Complex methodology; not widely accepted by regulators |

The superiority of head-to-head RCTs is particularly evident when examining hypothetical scenarios. For instance, as illustrated in one analysis, where Drug A reduced blood glucose by -3 mmol/L versus -2 mmol/L for Drug C in one trial, and Drug B reduced it by -2 mmol/L versus -1 mmol/L for Drug C in another trial, a naïve comparison would incorrectly suggest Drug A is superior to Drug B (-1 mmol/L difference). However, an adjusted indirect comparison correctly shows no difference (0 mmol/L) after accounting for the common comparator [12].

Practical Limitations and Methodological Challenges

Resource and Feasibility Constraints

Head-to-head RCTs present substantial practical challenges that limit their widespread implementation. These studies are typically expensive, time-consuming, and require large sample sizes, particularly when designed to demonstrate non-inferiority or equivalence between active treatments [12]. The resource intensiveness of these trials creates a significant barrier to their conduct, resulting in a comparative evidence gap for many therapeutic areas where multiple treatment options exist.

This challenge is particularly acute in rare diseases, where "RCTs may have to draw from a very small population of interest, which may make enrollment very challenging" [26]. Additionally, for outcomes that manifest over extended timeframes (such as long-term drug safety or chronic disease progression), RCTs "may be of limited value... because RCTs are frequently small and/or of too short duration for uncommon harms or longer-term harms to be detected" [26]. These constraints often force researchers to rely on surrogate endpoints rather than clinically important outcomes, potentially limiting the practical relevance of findings.

Ethical and Equity Considerations

The implementation of head-to-head RCTs must navigate complex ethical terrain. In situations where clinical equipoise is absent—meaning one treatment is already widely believed to be superior—randomizing patients to the presumed inferior intervention may be ethically problematic [26] [27]. This challenge frequently arises when preliminary evidence suggests potential differences in efficacy or safety between treatments but falls short of conclusive proof.

The principle of clinical equipoise ("genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community... about the preferred treatment") presents practical difficulties in its application and assessment [27]. As noted in the ethical discussion of RCTs, "equipoise may be difficult to ascertain," and "collective equipoise" may conflict with a lack of "personal equipoise" among individual clinicians or patients [27]. These ethical complexities can prevent or delay important comparative studies, particularly when one treatment is more expensive or invasive than another.

Generalizability and External Validity Concerns

While head-to-head RCTs excel in internal validity, their generalizability to real-world clinical practice is often limited. These trials typically employ strict eligibility criteria, resulting in homogeneous study populations that may not reflect the diversity of patients encountered in routine practice [26] [30]. As one analysis notes, "results of some RCTs may not be broadly applicable due to their narrow eligibility criteria for participants, tightly controlled implementation of interventions and comparators, smaller sample size, shorter duration, and focus on short-term, surrogate, and/or composite outcomes" [26].

The highly controlled nature of RCTs, while methodologically advantageous for establishing efficacy, simultaneously distances these studies from real-world clinical contexts where treatments are implemented with variable adherence, in combination with other therapies, and across diverse healthcare settings [28] [30]. This limitation has prompted increased interest in pragmatic trials and real-world evidence to complement the efficacy data generated by traditional RCTs.

Head-to-Head RCT Balance of Attributes

Industry Sponsorship and Its Impact on Evidence Generation

Dominance of Industry-Funded Research

The landscape of head-to-head RCTs is predominantly shaped by industry sponsorship, which introduces specific methodological biases and strategic considerations. A systematic examination of RCTs published in 2011 revealed that the literature of head-to-head RCTs is overwhelmingly dominated by industry funding, with "238,386 of the 289,718 randomized subjects (82.3%) included in the 182 trials funded by companies" [29]. This funding pattern has profound implications for the questions being investigated, the designs employed, and the results disseminated.

Industry-sponsored trials differ systematically from investigator-initiated studies in several important aspects. They tend to be larger, more commonly registered, and use noninferiority or equivalence designs more frequently than non-industry-sponsored trials [29]. Perhaps most importantly, industry-funded trials are "more likely to have 'favorable' results (superiority or noninferiority/equivalence for the experimental treatment)" [29]. This association remains strong even after accounting for other trial characteristics.

Design Selection and Outcome Reporting Biases

The influence of sponsorship extends to fundamental design choices that affect the interpretation and clinical relevance of head-to-head comparisons. Statistical analysis reveals that both industry funding (OR 2.8; 95% CI: 1.6, 4.7) and noninferiority/equivalence designs (OR 3.2; 95% CI: 1.5, 6.6) are independently associated with "favorable" findings [29]. The strength of this association is particularly pronounced, with "55 of the 57 (96.5%) industry-funded noninferiority/equivalence trials getting desirable 'favorable' results" [29].

This pattern suggests strategic design selection that increases the likelihood of commercially favorable outcomes, potentially at the expense of clinically meaningful comparisons. When sponsors invest in head-to-head trials, they typically do so when confident of a favorable outcome, creating a publication bias in the comparative evidence base. This selective investigation means that many clinically important comparative questions remain unaddressed when commercial incentives are misaligned with scientific or clinical needs.

Table 2: Industry Sponsorship Patterns in Head-to-Head RCTs (Based on 2011 Sample)

| Trial Characteristic | Industry-Sponsored (n=182) | Non-Industry-Sponsored (n=137) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Randomized Subjects | 238,386 (82.3%) | 51,332 (17.7%) | P < 0.001 |

| Average Sample Size | Larger | Smaller | P < 0.05 |

| Trial Registration | More common | Less common | P < 0.05 |

| Use of Noninferiority/Equivalence Design | More frequent | Less frequent | P < 0.05 |

| "Favorable" Results (for experimental treatment) | 76.9% | 57.7% | P < 0.001 (OR 2.8) |

| Multiple Industry Sponsors | 23/182 (12.6%) | N/A | N/A |

Methodological Innovations and Evolving Paradigms

Adaptive and Pragmatic Trial Designs

Recent methodological innovations aim to address some limitations of traditional head-to-head RCTs while preserving their core strengths. Adaptive trial designs incorporate planned modifications based on interim analyses of accumulating data, making more efficient use of resources and potentially reducing the number of patients exposed to inferior treatments [28] [31]. These designs include sequential trials that continuously analyze results as participants are enrolled, allowing early termination once sufficient evidence is obtained [28].

Platform trials represent another significant innovation, focusing on "an entire disease or syndrome to compare multiple interventions and add or drop interventions over time" [28]. This approach is particularly valuable for conditions with multiple therapeutic options, as it creates a sustainable infrastructure for iterative comparison. The RECOVERY trial for COVID-19 treatments exemplifies this model, using a combination of parallel-group, sequential, and factorial randomizations to efficiently evaluate multiple interventions within a single master protocol [31].

Integration with Real-World Evidence and Registry Data

The growing availability of electronic health records (EHRs) and clinical registries has enabled new approaches to conducting head-to-head comparisons. Registry-based RCTs leverage existing data infrastructure to streamline participant identification, randomization, and outcome assessment, significantly reducing the cost and administrative burden of traditional trials [31]. The TASTE trial, which evaluated a medical device for patients with acute myocardial infarction, demonstrated the feasibility of this approach by using existing national registries for patient enrollment and outcome ascertainment [31].

The integration of real-world evidence (RWE) with RCT data offers promising opportunities to enhance both the efficiency and generalizability of comparative effectiveness research. RWE, derived from sources such as EHRs, health claims data, and digital health tools, "reflects the actual clinical aspects" of treatment and can provide complementary information about effectiveness in diverse real-world populations [30]. When carefully analyzed using advanced causal inference methods, RWE can address questions that may be impractical or unethical to study in traditional RCTs.

Evolution of Head-to-Head RCT Methodologies

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Key Methodological Protocols for Head-to-Head RCTs

The validity of head-to-head RCTs depends on rigorous implementation of specific methodological protocols. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines provide a standardized framework for reporting these studies, ensuring transparency and critical appraisal [27]. Key design elements include proper random sequence generation using computer-generated algorithms rather than quasi-random methods, allocation concealment to prevent selection bias, and implementation of blinding whenever feasible to minimize performance and detection biases [27].

For noninferiority trials—a common design in head-to-head comparisons—prespecified noninferiority margins must be clinically justified and statistically appropriate, representing the maximum acceptable difference in effectiveness for which the experimental treatment would still be considered noninferior [29]. Sample size calculations for these designs require careful consideration of both statistical power and the noninferiority margin, typically requiring larger samples than superiority trials to demonstrate comparable efficacy [12] [29].

Protocols for large simple trials emphasize streamlined data collection, minimal exclusion criteria, and outcome assessment through routine health records [31]. The RECOVERY trial exemplifies this approach with its "one-page electronic case report form" completed at randomization and again at 28 days, supplemented by linkage to national healthcare datasets [31]. This design enables rapid enrollment, representative sampling, and efficient follow-up while maintaining methodological rigor.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for Head-to-Head RCTs

| Research Reagent/Methodological Tool | Primary Function | Application in Head-to-Head RCTs |

|---|---|---|

| Centralized Randomization System | Ensures allocation concealment and sequence generation | Prevents selection bias; maintains randomization integrity across sites |

| Validated Outcome Measures | Standardized assessment of efficacy and safety endpoints | Ensures consistent, reproducible outcome measurement across treatment groups |

| Blinding Protocols | Minimizes performance and detection bias | Reduces influence of expectations on treatment administration and outcome assessment |

| Clinical Registries | Population-based databases of patient characteristics and outcomes | Facilitates participant identification, outcome ascertainment, and generalizability assessment |

| Data Monitoring Committees | Independent oversight of accumulating trial data | Ensures participant safety and trial integrity; conducts interim analyses |

| Causal Inference Methods | Statistical approaches for estimating treatment effects | Enhances analysis of observational components; addresses post-randomization biases |

Head-to-head RCTs remain an essential methodology for comparing therapeutic interventions, providing the most reliable evidence for causal inference about relative treatment effects. Their strengths in controlling confounding through randomization and their high internal validity justify their position as the preferred approach for establishing comparative efficacy. However, practical limitations including resource intensiveness, ethical constraints, and generalizability concerns necessitate their thoughtful application within a broader evidence generation ecosystem.

The future of comparative effectiveness research lies not in unquestioned adherence to head-to-head RCTs as a standalone gold standard, but in their strategic integration with other evidence sources. Triangulation of evidence from RCTs, observational studies, real-world data, and patient perspectives offers the most robust foundation for clinical and policy decisions [28]. As methodological innovations continue to evolve—including adaptive designs, registry-based trials, and advanced causal inference methods—the scientific community must maintain focus on the fundamental goal: generating reliable, relevant evidence to inform optimal treatment decisions for diverse patient populations.

Rather than viewing different methodological approaches as competing alternatives, researchers should recognize their complementary strengths and limitations. As one analysis concludes, "No study is designed to answer all questions, and consequently, neither RCTs nor observational studies can answer all research questions at all times. Rather, the research question and context should drive the choice of method to be used" [28]. Within this context, head-to-head RCTs will continue to play a vital, though not exclusive, role in advancing comparative effectiveness research and guiding evidence-based therapeutic decisions.

In the field of comparative drug efficacy research, head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard for evidence generation [32]. However, ethical constraints, practical feasibility issues, and the proliferation of treatment options often make direct comparisons impossible or impractical [32] [12]. Indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) have emerged as a crucial methodological framework that enables researchers to estimate relative treatment effects when direct evidence is unavailable [33].

These techniques are particularly valuable in health technology assessment (HTA) and drug development decision-making, where comparisons against multiple relevant alternatives are essential [32]. The fundamental principle underlying ITCs involves leveraging a common comparator (typically placebo or standard care) that connects two or more interventions through a network of evidence [12]. This approach preserves the randomization benefits of the original trials while enabling comparisons that were not directly tested in clinical studies [12].

Fundamental Methods and Statistical Frameworks

Core Methodological Approaches

The simplest and most flawed approach is the naïve direct comparison, which directly compares results from different trials without adjustment [12]. This method breaks the original randomization and introduces significant confounding bias, as differences may reflect variations in trial populations, designs, or conditions rather than true treatment effects [12] [33].

The adjusted indirect comparison, introduced by Bucher et al., provides a statistically sound alternative that preserves randomization [12]. This method compares the magnitude of treatment effects between two interventions relative to a common comparator, which serves as the linking element [12]. The validity of this approach depends critically on the similarity assumption, which requires that the trials being compared are sufficiently similar in effect modifiers and clinical characteristics [33].

Network meta-analysis (NMA) extends these principles to complex evidence networks involving multiple treatments [32]. As the most frequently described ITC technique (79.5% of included articles in a recent systematic review), NMA incorporates all available direct and indirect evidence to provide coherent estimates of relative treatment effects across an entire network of interventions [32].

Table 1: Key Indirect Treatment Comparison Techniques

| Method | Description | Key Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Indirect Comparison | Compares two treatments via their effects against a common comparator [12] | Two trials with a common comparator; similarity assumption | Preserves randomization; statistically sound | Increased uncertainty; requires similarity |

| Network Meta-Analysis | Simultaneously analyzes network of treatments using direct and indirect evidence [32] | Connected network of trials; consistency assumption | Uses all available evidence; ranks multiple treatments | Complex methodology; multiple assumptions |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | Weightes individual patient data to match aggregate trial characteristics [32] | Individual patient data for at least one trial | Adjusts for cross-trial differences | Relies on observed characteristics only |

| Bucher Method | Frequentist approach for simple indirect comparisons [32] | Two trials with common comparator | Simple implementation; transparent | Limited to simple comparisons |

Statistical Workflow for Indirect Comparisons

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and implementing appropriate indirect comparison methods:

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Adjusted Indirect Comparison

The implementation of a valid adjusted indirect comparison requires meticulous methodology and strict adherence to statistical principles:

Literature Search and Trial Selection: Conduct a comprehensive systematic review to identify all relevant RCTs for the treatments of interest and the common comparator [33]. Implement predefined eligibility criteria based on the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) framework and document the search strategy transparently [32].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment: Extract treatment effect estimates (e.g., odds ratios, hazard ratios, mean differences) with their measures of variance (confidence intervals or standard errors) for each treatment-comparator pair [12]. Assess risk of bias in individual studies using validated tools like Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment [33].

Statistical Analysis: Calculate the indirect estimate using the Bucher method: for treatments A and B with common comparator C, the indirect log odds ratio is ln(ORAB) = ln(ORAC) - ln(ORBC) [12]. The variance of the indirect estimate is the sum of the variances of the two direct comparisons: Var(ln(ORAB)) = Var(ln(ORAC)) + Var(ln(ORBC)) [12].

Assumption Validation: Explicitly evaluate the similarity assumption by comparing trial characteristics, including patient demographics, disease severity, concomitant treatments, and outcome definitions [33]. Perform subgroup or meta-regression analyses to explore potential effect modifiers when sufficient data are available [33].

Protocol for Network Meta-Analysis

Network meta-analysis requires additional methodological considerations:

Network Geometry Evaluation: Diagram the evidence network to visualize the connectivity between treatments and identify potential gaps in the evidence base [32]. Assess whether the network is sufficiently connected to yield reliable estimates.

Consistency Assessment: Evaluate the statistical consistency between direct and indirect evidence where both are available [33]. Use node-splitting approaches or design-by-treatment interaction models to test for inconsistency within the network.

Model Implementation: Implement either Bayesian or frequentist approaches using appropriate software [32]. Bayesian methods typically employ Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation with non-informative priors, while frequentist approaches use multivariate meta-analysis techniques.

Uncertainty and Heterogeneity: Account for between-study heterogeneity using random-effects models and assess its impact on results [33]. Present results with appropriate measures of uncertainty, such as credible intervals (Bayesian) or confidence intervals (frequentist).

Applications in Single-Arm Trials and Complex Scenarios

Indirect Comparisons with External Controls

In therapeutic areas such as oncology and rare diseases, single-arm trials (SATs) are increasingly common due to ethical and practical constraints [34]. These designs present unique challenges for comparative effectiveness research:

Threshold Establishment: SATs typically establish success criteria based on historical controls or clinical consensus [34]. The threshold represents the expected outcome in the hypothetical untreated scenario, and efficacy is demonstrated when the observed result exceeds this benchmark with statistical significance.

Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC): When individual patient data (IPD) are available for one trial but only aggregate data for another, MAIC weights the IPD to match the aggregate population characteristics [32]. This method effectively creates a simulated population that is more comparable to the aggregate data cohort.

Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC): This technique uses multivariable regression on IPD to adjust for cross-trial differences in effect modifiers [32]. By modeling the relationship between baseline characteristics and outcomes, STC predicts how the treatment effect would manifest in the target population.

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Single-Arm Trial Contextualization

| Method | Data Requirements | Key Assumptions | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Control Comparison | Aggregate data from historical studies | Stable natural history; comparable populations | Early-phase oncology; rare diseases |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | IPD for index trial; aggregate for comparator | All effect modifiers are measured and included | HTA submissions with limited RCT data |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) | IPD for index trial; aggregate for comparator | Correct specification of outcome model | Comparisons where effect modifiers are known |

Methodological Challenges and Limitations

All indirect comparison methods face significant methodological challenges that researchers must acknowledge and address:

Similarity Assumption Violations: The core assumption of similarity is fundamentally untestable and may be violated by differences in trial populations, settings, or methodologies [33]. Even small differences in effect modifiers can introduce bias in indirect estimates.

Increased Statistical Uncertainty: Indirect comparisons inherently accumulate statistical uncertainty from each direct comparison in the evidence chain [12]. This results in wider confidence intervals compared to direct evidence from adequately powered RCTs.

Inconsistency Between Direct and Indirect Evidence: Empirical studies have documented cases where direct and indirect estimates disagree significantly [33]. Such inconsistencies may indicate violations of the similarity assumption or the presence of effect modifiers.

Limited Acceptability by Decision-Makers: Health technology assessment agencies and regulatory bodies often view indirect evidence as supplementary to direct head-to-head trials [32]. The acceptability of ITCs remains variable across different jurisdictions and decision-making contexts.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Indirect Comparisons

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (gemtc, pcnetmeta), SAS, WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Implementation of complex statistical models for ITC and NMA |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Cochrane Risk of Bias, GRADE for NMA | Assessment of evidence quality and potential biases |

| Data Extraction Frameworks | PRISMA for Systematic Reviews, PICO Framework | Structured approach to literature review and data collection |

| Assumption Checking Methods | Net heat plots, node-splitting, inconsistency factors | Evaluation of similarity and consistency assumptions |

| Visualization Tools | Network diagrams, forest plots, rankograms | Communication of complex evidence networks and results |

Indirect treatment comparisons represent a powerful methodological framework for estimating comparative drug effectiveness when direct evidence is unavailable. By leveraging a common comparator such as placebo or standard care, these techniques enable researchers to construct connected evidence networks that support decision-making in drug development and health technology assessment.

The appropriate application of ITC methods requires careful consideration of their underlying assumptions, particularly the similarity assumption that trials are sufficiently comparable in their effect modifiers. Methodological choices should be guided by the available evidence base, including the number of treatments being compared, the connectivity of the evidence network, and the availability of individual patient data.

As these techniques continue to evolve, researchers should prioritize transparent reporting, thorough sensitivity analyses, and appropriate interpretation of results within the constraints of the methodological approach. When properly implemented, indirect comparisons provide valuable evidence to inform clinical and policy decisions in situations where direct head-to-head trials are not feasible or ethical.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) represents a significant methodological advancement in evidence-based medicine, extending traditional pairwise meta-analysis to allow for the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions, even when direct head-to-head comparisons are not available [35]. Clinical decision-making requires the synthesis of evidence from literature reviews, and while conventional systematic reviews with pairwise meta-analyses are useful for combining homogeneous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing two treatments, they fall short in real-world scenarios where healthcare providers must choose among numerous treatment options [36]. NMA addresses this limitation by integrating both direct evidence (from trials directly comparing treatments) and indirect evidence (through common comparators) within a single analytical framework [37]. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of treatment options for clinicians and researchers, particularly in fields like cardiovascular research, pain management, and ophthalmology where multiple competing interventions exist [36] [38] [37].

The foundational principle of NMA rests on connecting interventions through a network of comparisons. For example, if Treatment A has been compared to Treatment B in some trials, and Treatment B has been compared to Treatment C in others, NMA enables an indirect comparison between Treatment A and Treatment C through their common connection to Treatment B [39]. This interconnected network of treatment comparisons allows researchers to fill knowledge gaps in the available evidence and provide more precise effect estimates to guide decision-making in complex clinical scenarios [36]. The methodology has gained substantial traction in recent years, with 456 NMAs with four or more treatments identified up until 2015 [40], reflecting its growing importance in comparative effectiveness research.

Fundamental Principles and Key Assumptions

Transitivity and Consistency