Comparative ADMET Profiling of Analogs: Strategies for Lead Optimization in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic application of comparative ADMET profiling for analog series.

Comparative ADMET Profiling of Analogs: Strategies for Lead Optimization in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic application of comparative ADMET profiling for analog series. It covers foundational principles, explores cutting-edge computational methodologies like hybrid tokenization and graph-based models, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines robust validation frameworks. By integrating the latest advances in machine learning, web-based optimization tools, and experimental design, this resource aims to enhance lead optimization efficiency, reduce late-stage attrition, and accelerate the development of safer, more effective drug candidates.

ADMET Foundations: Why Analog Profiling is Critical in Modern Drug Discovery

Drug discovery and development is a long, costly, and high-risk process that takes over 10–15 years with an average cost of over $1–2 billion for each new drug to be approved for clinical use [1]. Despite significant advances in scientific methodologies, the attrition rate in late-stage drug development remains alarmingly high at over 80%, particularly in Phase II and III clinical trials [2]. Analyses of clinical trial data reveal that approximately 40–50% of failures are due to lack of clinical efficacy, while about 30% are attributed to unmanageable toxicity [1]. These persistent failure rates occur despite implementation of many successful strategies in target validation and drug optimization, raising critical questions about whether certain aspects in drug optimization are being overlooked in current practice.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a critical challenge: 90% of clinical drug development fails for candidates that have already entered clinical trials [1]. This statistic does not include failures at the preclinical stage, making the overall success rate even lower. Issues with ADMET properties—Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity—represent a fundamental bottleneck that contributes significantly to these failures. As traditional approaches struggle to predict human pharmacokinetics and toxicity accurately, new methodologies are emerging to address these challenges through advanced computational modeling, comprehensive benchmarking, and innovative experimental design.

The ADMET Failure Landscape: Beyond Efficacy

Why Potency Alone Is Not Enough

Current drug discovery often overemphasizes potency and specificity using structure-activity relationship (SAR) while overlooking tissue exposure and selectivity in disease versus normal tissues [1]. This imbalance can mislead drug candidate selection and negatively impact the balance of clinical dose, efficacy, and toxicity. The limitations of this approach become apparent when drug candidates with excellent in vitro potency fail in clinical stages due to inadequate ADMET properties.

The structure–tissue exposure/selectivity–activity relationship (STAR) framework has been proposed to improve drug optimization by classifying drug candidates based on both potency/selectivity and tissue exposure/selectivity [1]. This classification system identifies four distinct categories:

- Class I: High specificity/potency and high tissue exposure/selectivity (needs low dose for superior clinical efficacy/safety)

- Class II: High specificity/potency but low tissue exposure/selectivity (requires high dose with high toxicity)

- Class III: Relatively low specificity/potency but high tissue exposure/selectivity (often overlooked despite good efficacy)

- Class IV: Low specificity/potency and low tissue exposure/selectivity (should be terminated early)

This framework explains why some compounds with adequate potency fail clinically while others with moderate potency succeed, highlighting the critical importance of ADMET properties in overall compound performance.

Key ADMET Failure Points

Late-stage attrition due to ADMET issues manifests across multiple domains. Poor bioavailability remains a significant challenge, with many compounds failing due to inadequate absorption or rapid clearance [2]. Hepatotoxicity has been a common factor in post-approval drug withdrawals, making liver safety evaluation a critical part of early drug screening [3]. Cardiotoxicity risks, particularly through hERG channel inhibition, continue to eliminate promising candidates despite extensive screening protocols [3] [4].

Species-specific metabolic differences between animal models and humans present another major challenge, potentially masking human-relevant toxicities and distorting results for other endpoints [3]. Historical cases like thalidomide and fialuridine underscore the limitations of traditional preclinical testing in capturing human-specific risks. Furthermore, drug-drug interactions mediated through CYP450 inhibition or induction can render otherwise effective compounds unsafe in clinical settings where polypharmacy is common [2].

Table 1: Primary Causes of Clinical Stage Attrition Linked to ADMET Properties

| Failure Cause | Percentage of Failures | Key ADMET Properties Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Efficacy | 40-50% | Distribution, Metabolism, Absorption |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | ~30% | Toxicity, Metabolism, Distribution |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties | 10-15% | Absorption, Metabolism, Excretion |

| Strategic/Commercial Issues | ~10% | N/A |

Modern ADMET Assessment Platforms and Benchmarking

Evolution from Traditional to AI-Driven Approaches

Traditional ADMET assessment methods, including in vitro assays (e.g., cell-based permeability, metabolic stability studies) and in vivo animal models, remain central to early drug development but are difficult to scale [3]. As compound libraries grow, these resource-intensive methods become increasingly impractical. Early computational approaches, especially quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, brought automation but their static features and narrow scope limit scalability and reduce performance on novel diverse compounds.

The field has since evolved through several generations of approaches. Open-source platforms like Chemprop, DeepMol, and OpenADMET contributed meaningful advances but face limitations in interpretability, adaptability, and generalization to novel chemical space [3]. Current deep learning models utilizing graph-based molecular embeddings and multi-task learning represent the state of the art, demonstrating improved performance across multiple ADMET endpoints.

Federated learning has emerged as a transformative approach, enabling model training across distributed proprietary datasets without centralizing sensitive data [5]. Cross-pharma research consistently shows that federated models systematically outperform local baselines, with performance improvements scaling with the number and diversity of participants. This approach expands applicability domains, with models demonstrating increased robustness when predicting across unseen scaffolds and assay modalities.

Benchmarking Platforms and Performance Standards

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating ADMET prediction tools. The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) ADMET Benchmark Group provides a standardized framework for comparing model performance across 22 ADMET datasets [4]. This comprehensive benchmark covers absorption (Caco-2, HIA, Pgp), distribution (BBB, PPBR, VDss), metabolism (CYP inhibition and substrates), excretion (half-life, clearance), and toxicity (LD50, hERG, Ames, DILI) endpoints.

Table 2: Selected ADMET Benchmark Metrics from TDC [4]

| Endpoint | Measurement Unit | Dataset Size | Task Type | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | cm/s | 906 | Regression | MAE |

| Human Intestinal Absorption | % | 578 | Binary | AUROC |

| BBB Penetration | % | 1,975 | Binary | AUROC |

| CYP2C9 Inhibition | % | 12,092 | Binary | AUPRC |

| hERG Inhibition | % | 648 | Binary | AUROC |

| Ames Mutagenicity | % | 7,255 | Binary | AUROC |

| VDss | L/kg | 1,130 | Regression | Spearman |

| Half Life | hr | 667 | Regression | Spearman |

More recently, PharmaBench has addressed limitations of earlier benchmarks by leveraging large language models to extract experimental conditions from 14,401 bioassays, resulting in a comprehensive benchmark set comprising eleven ADMET datasets and 52,482 entries [6]. This approach significantly expands coverage of chemical space and better represents compounds used in actual drug discovery projects, addressing concerns that previous benchmarks included only a small fraction of publicly available data and compounds that differed substantially from those in industrial drug discovery pipelines.

Comparative Analysis of ADMET Prediction Approaches

In Silico Model Performance Comparison

Multiple approaches to ADMET prediction have demonstrated varying strengths and limitations. Receptor.AI's ADMET model exemplifies modern deep learning approaches, combining multi-task learning methodologies, graph-based molecular embeddings (Mol2Vec), and rigorous expert-driven validation processes [3]. The model is available in four variants optimized for different virtual screening contexts, ranging from a fast Mol2Vec-only version to a comprehensive Mol2Vec+Best version that combines embeddings with curated molecular descriptors for maximum accuracy.

Traditional rule-based approaches like Lipinski's "Rule of Five" continue to provide valuable initial screening but lack the sophistication for nuanced predictions [7]. The quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) concept introduced greater flexibility by replacing stiff cutoffs with a continuous index based on eight physicochemical properties [7]. However, both approaches focus primarily on physicochemical properties without incorporating specific ADMET endpoint predictions.

The ADMET-score represents a comprehensive scoring function that integrates predictions from 18 ADMET properties, with weights determined by model accuracy, endpoint importance in pharmacokinetics, and usefulness index [7]. This approach has demonstrated significant differentiation between FDA-approved drugs, general small molecules, and withdrawn drugs, suggesting its utility as a comprehensive index for evaluating chemical drug-likeness.

Integrated Workflows for ADMET Profiling

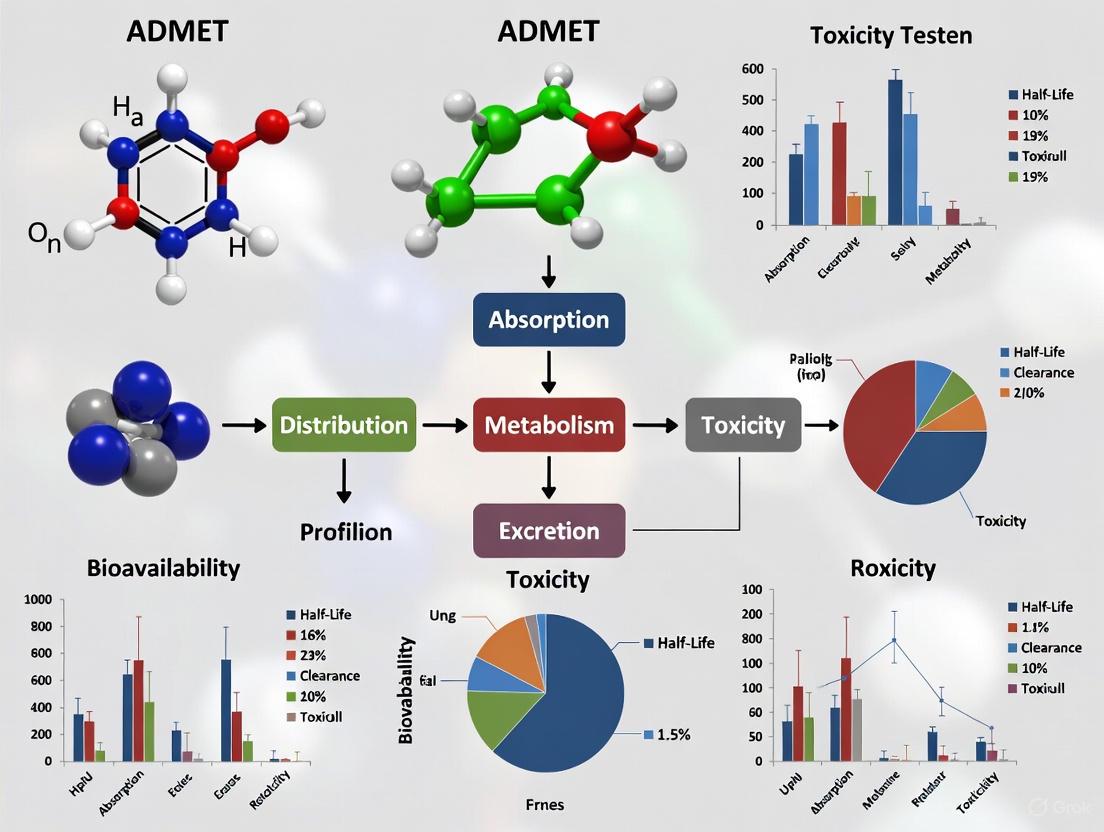

Effective ADMET assessment requires integrated workflows that combine computational predictions with experimental validation. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive ADMET profiling workflow that bridges in silico and in vitro approaches:

Comprehensive ADMET Profiling Workflow

This workflow begins with in silico screening of compound libraries using molecular descriptors and machine learning prediction models, progressing to comprehensive ADMET scoring that integrates multiple endpoints. Promising candidates then advance to in vitro validation using established DMPK assays before final data integration and go/no-go decisions.

Experimental Protocols for Key ADMET Assays

Critical In Vitro DMPK Assays

Well-established experimental protocols form the foundation of reliable ADMET assessment. Key in vitro DMPK assays provide essential data on compound behavior before advancing to more resource-intensive in vivo studies:

Metabolic Stability Assays utilize liver microsomes or hepatocytes from humans or animals to evaluate the rate at which a compound is metabolized, influencing its half-life and clearance [2]. Protocols typically involve incubating test compounds with metabolic systems, sampling at multiple time points, and quantifying parent compound disappearance using LC-MS/MS. A drug that is rapidly broken down may have a short duration of action, requiring frequent or higher dosing.

Permeability Assays assess a drug's ability to cross biological membranes, particularly the intestinal epithelium, which is crucial for oral absorption and bioavailability [2]. The Caco-2 cell permeability model mimics human intestinal barriers through cultured colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, while the Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA) provides a non-cell-based method for evaluating passive, transcellular intestinal absorption.

Plasma Protein Binding assays measure the degree to which a compound binds to proteins within plasma, typically using equilibrium dialysis or ultrafiltration methods [2]. Only the unbound (free) fraction of a drug is pharmacologically active and available for distribution, making this parameter critical for understanding efficacy potential.

CYP450 Inhibition and Induction assays identify potential drug-drug interactions by testing compounds against major cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4) using fluorescent probes or LC-MS/MS detection [2]. Inhibition of CYP450 enzymes may result in higher-than-intended levels of co-administered drugs, potentially leading to adverse effects or toxicity.

Molecular Descriptors and Feature Engineering

Feature engineering plays a crucial role in improving ADMET prediction accuracy. Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that convey structural and physicochemical attributes of compounds based on their 1D, 2D, or 3D structures [8]. These include:

- Constitutional descriptors: Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts

- Topological descriptors: Connectivity indices, molecular graphs

- Electronic descriptors: Partial charges, polarizability, HOMO/LUMO energies

- Geometric descriptors: Molecular volume, surface areas, shape indices

Recent advancements involve learning task-specific features by representing molecules as graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [8]. Graph convolutions applied to these explicit molecular representations have achieved unprecedented accuracy in ADMET property prediction. Feature selection methods—including filter, wrapper, and embedded approaches—help determine relevant properties for specific classification or regression tasks, alleviating the need for time-consuming experimental assessments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for ADMET Profiling

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico Platforms | ADMETlab 3.0, admetSAR 2.0, Receptor.AI | Computational prediction of ADMET properties | Early screening, compound prioritization, liability identification |

| Benchmark Databases | TDC ADMET Group, PharmaBench, MoleculeNet | Standardized datasets for model training and validation | Performance benchmarking, model development, transfer learning |

| Molecular Descriptors | RDKit, Mordred, Dragon | Calculation of structural and physicochemical properties | Feature engineering, QSAR modeling, similarity assessment |

| CYP450 Assay Systems | Human liver microsomes, recombinant enzymes, fluorescent substrates | Metabolic stability and drug-drug interaction assessment | CYP inhibition screening, metabolic clearance prediction |

| Permeability Models | Caco-2 cells, PAMPA, MDCK-MDR1 | Membrane permeability measurement | Absorption prediction, transporter effects, BBB penetration |

| Toxicity Assays | hERG binding, Ames test, hepatocyte imaging | Safety liability identification | Cardiotoxicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity assessment |

| Protein Binding Assays | Human plasma, equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration | Free fraction determination | Tissue distribution prediction, efficacy optimization |

Regulatory Considerations and Future Directions

Evolving Regulatory Frameworks

Regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the value of advanced ADMET prediction approaches. The FDA and EMA have demonstrated openness to AI in ADMET prediction, provided models are transparent and well-validated [3]. In April 2025, the FDA outlined a plan to phase out animal testing requirements in certain cases, formally including AI-based toxicity models and human organoid assays under its New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) framework [3].

These tools may now be used in Investigational New Drug and Biologics License Application submissions, provided they meet scientific and validation standards. The regulatory shift acknowledges both the ethical imperative to reduce animal testing and the technological advances that make alternative approaches increasingly reliable. However, significant challenges persist around model interpretability, with the black-box nature of many complex algorithms hindering scientific validation and regulatory acceptance where clear insight and reproducibility are essential.

Emerging Technologies and Methodologies

Future advances in ADMET prediction will likely come from several emerging approaches. Federated learning enables multiple organizations to collaboratively train models without sharing proprietary data, addressing fundamental limitations of isolated modeling efforts [5]. Cross-pharma initiatives like MELLODDY have demonstrated that federation systematically extends models' effective domain, improving coverage and reducing discontinuities in learned representations.

Large language models are being applied to extract experimental conditions from biomedical literature at scale, facilitating the creation of more comprehensive and standardized benchmarks [6]. The multi-agent LLM system used to develop PharmaBench represents a significant advance in automated data curation, potentially enabling more rapid incorporation of new public data into prediction models.

Integrated multi-task learning approaches that capture complex interdependencies among pharmacokinetic and toxicological endpoints show promise for improving prediction consistency and reliability [3]. As model performance increasingly becomes limited by data diversity rather than algorithms, approaches that maximize learning from available data will become increasingly valuable.

The high cost of failure in late-stage drug development remains a significant challenge for the pharmaceutical industry, with ADMET properties playing a crucial role in attrition rates. While traditional approaches to ADMET assessment provide valuable data, they struggle with scalability and prediction accuracy for novel chemical entities. Advanced computational approaches, including machine learning and federated learning, show significant promise for improving prediction accuracy and reducing late-stage failures.

The integration of comprehensive in silico profiling with targeted experimental validation represents the most effective strategy for identifying compounds with optimal ADMET properties early in development. As regulatory frameworks evolve to embrace these advanced methodologies, and as benchmarking initiatives provide clearer standards for model performance, the field moves closer to realizing the goal of accurately predicting human pharmacokinetics and toxicity before compounds enter clinical development.

By adopting integrated workflows that leverage both computational and experimental approaches, researchers can significantly de-risk the drug development process, focusing resources on candidates with the highest likelihood of clinical success. This approach ultimately supports the broader objective of bringing safe and effective therapies to patients more efficiently while reducing the tremendous costs associated with late-stage failures.

In modern drug discovery, the assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) parameters is crucial for evaluating the viability and safety of candidate compounds. ADMET properties collectively describe how a drug moves through and interacts with the body, determining its systemic exposure and potential side effects [9] [10]. These properties significantly influence the pharmacological activity, dosing regimen, and overall success of a pharmaceutical compound, with poor ADMET characteristics being a primary reason for late-stage drug development failures [3].

The acronym ADMET extends from the foundational concept of pharmacokinetics, which traditionally focuses on Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) [11] [9]. The addition of "T" (Toxicity) reflects the critical importance of understanding a compound's potential adverse effects early in the development process [12]. For researchers conducting comparative ADMET profiling of analogs, a thorough understanding of these core parameters enables more informed decisions in selecting lead compounds with the highest probability of therapeutic success.

Defining the Core ADMET Parameters

Absorption

Absorption refers to the process by which a drug moves from its site of administration into the systemic circulation [11] [10]. This parameter critically determines the bioavailability, defined as the fraction of the administered drug that reaches systemic circulation intact [11]. For instance, intravenous administration provides 100% bioavailability, while oral medications must navigate stomach acidity, digestive enzymes, and intestinal absorption, often resulting in reduced bioavailability due to first-pass metabolism in the liver [11] [10]. Key factors influencing absorption include the drug's chemical properties, formulation, and route of administration (oral, intravenous, transdermal, etc.) [11] [10].

Distribution

Distribution describes how an absorbed drug disseminates throughout the body's various tissues and fluids [11]. This process is influenced by factors such as blood flow, molecular size, polarity, and particularly protein binding, as only unbound drug molecules can exert pharmacological effects [11] [10]. Distribution is quantified by the volume of distribution (Vd), a fundamental pharmacokinetic parameter that relates the amount of drug in the body to its plasma concentration [11]. A drug's ability to cross natural barriers like the blood-brain barrier is a critical distribution consideration that can significantly impact therapeutic efficacy [9].

Metabolism

Metabolism encompasses the biochemical modification of drugs, typically transforming them into more water-soluble compounds for easier elimination [11] [10]. The liver serves as the primary site of metabolism, where enzymes—particularly the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family—catalyze Phase I (functionalization) and Phase II (conjugation) reactions [11] [10]. While metabolism generally inactivates drugs, some administered compounds (prodrugs) require metabolic conversion to become therapeutically active, and certain metabolites may themselves be pharmacologically active or toxic [11] [10].

Excretion

Excretion represents the final process of eliminating the drug and its metabolites from the body [11]. The kidneys are the principal organs of excretion, primarily through glomerular filtration and tubular secretion [9]. Other excretion routes include the bile (feces), lungs, and skin [11] [9]. The efficiency of excretion is measured by clearance, defined as the volume of plasma from which the drug is completely removed per unit of time [11]. Impaired excretion, particularly in patients with renal dysfunction, can lead to drug accumulation and potential toxicity [10].

Toxicity

Toxicity assessment evaluates the potential for a drug to cause harmful effects [12]. This parameter includes specific endpoints such as cardiotoxicity (e.g., hERG channel inhibition), hepatotoxicity (drug-induced liver injury), mutagenicity (Ames test), and lethal dose (LD50) measurements [13] [14]. Understanding toxicity mechanisms is essential for designing safer drugs and remains a critical focus in regulatory evaluations by agencies like the FDA and EMA [3].

Table 1: Core ADMET Parameters and Their Defining Characteristics

| Parameter | Definition | Key Processes | Primary Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Movement from administration site to systemic circulation | Liberation, membrane permeation | Route of administration, solubility, chemical stability, first-pass metabolism [11] [10] |

| Distribution | Reversible transfer between blood and tissues | Tissue partitioning, protein binding | Blood flow, tissue permeability, plasma protein binding, molecular size/lipophilicity [11] [9] |

| Metabolism | Biochemical conversion of drug molecules | Phase I (oxidation) and Phase II (conjugation) reactions | CYP enzyme activity, genetics, drug interactions, organ function [11] [10] |

| Excretion | Elimination of drug and metabolites from body | Renal filtration, biliary secretion, passive diffusion | Renal/hepatic function, molecular size, urine pH, transporter activity [11] [9] |

| Toxicity | Potential for harmful physiological effects | Off-target binding, reactive metabolite formation | hERG inhibition, metabolic activation, tissue accumulation, dosage [12] [13] |

Diagram 1: Integrated ADMET Process Flow showing the interconnected nature of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity pathways in drug disposition.

Experimental Methodologies for ADMET Profiling

In Vitro Assays and High-Throughput Screening

Traditional ADMET assessment relies on a battery of standardized in vitro assays that evaluate specific properties under controlled laboratory conditions. These assays provide crucial data points for comparative profiling of analog series [3]. Permeability studies often utilize Caco-2 cell models to predict intestinal absorption, while metabolic stability is assessed in human liver microsomes or hepatocytes [14] [3]. Toxicity screening includes mandatory hERG inhibition assays for cardiotoxicity assessment, Ames tests for mutagenicity, and various cell-based assays for hepatotoxicity [13] [3]. These experimental approaches are increasingly being adapted to high-throughput formats to accommodate the growing need for rapid compound screening in early discovery phases.

In Vivo and Clinical Evaluations

In vivo studies in animal models provide more comprehensive ADMET data by accounting for whole-organism complexity, including inter-organ transport, hormonal influences, and integrated physiology [3]. Key parameters measured in these studies include bioavailability, volume of distribution, half-life, and clearance [11] [10]. Such studies also identify species-specific differences in ADMET properties that may impact human translation. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA are increasingly accepting New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), including advanced in silico predictions and human organoid assays, to reduce reliance on animal testing while maintaining rigorous safety standards [3].

Table 2: Standardized Experimental Protocols for Key ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Parameter | Experimental Method | Key Measured Endpoints | Protocol Overview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Caco-2 Permeability Assay | Apparent permeability (Papp) | Culture Caco-2 cells on semi-permeable inserts for 21 days; apply test compound to apical side; measure basolateral appearance over time [14] [15] |

| Distribution | Plasma Protein Binding | Fraction unbound (Fu) | Incubate compound with human plasma; separate bound/free fractions using equilibrium dialysis or ultracentrifugation; quantify by LC-MS/MS [14] |

| Metabolism | Human Liver Microsome Stability | Intrinsic clearance (CLint) | Incubate compound with pooled human liver microsomes and NADPH; measure parent depletion over time; calculate half-life and CLint [14] |

| Enzyme Inhibition | CYP450 Inhibition | IC50 values | Incubate CYP isoform-specific substrates with human liver microsomes ± test compound; measure metabolite formation; determine inhibition potency [3] |

| Toxicity | hERG Inhibition | IC50 / pIC50 | Measure compound inhibition of hERG potassium current using patch-clamp electrophysiology or fluorescence-based assays; determine cardiac risk [14] [3] |

| Toxicity | Ames Test | Mutagenicity (positive/negative) | Incubate compound with Salmonella typhimurium strains ± metabolic activation; count revertant colonies; assess mutagenic potential [14] |

Computational Approaches for ADMET Prediction

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models

Computational ADMET prediction has emerged as a powerful approach to supplement experimental methods, leveraging machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to forecast compound properties from chemical structure [14] [16] [3]. These in silico methods enable rapid screening of virtual compound libraries and guide structural optimization before synthesis [3]. Current ML models employ diverse algorithms including random forests, support vector machines, and deep neural networks (DNNs) trained on large-scale ADMET datasets [14] [16]. Molecular representations for these models range from traditional molecular descriptors and fingerprints to more advanced graph neural networks (GCNNs) that directly learn from molecular structure [14] [16] [3]. Natural language processing approaches, such as ChemBERTa, have also been adapted to process SMILES strings (simplified molecular input line entry systems) for property prediction [16].

Current Tools and Platforms

The computational ADMET prediction landscape includes both commercial and open-source platforms offering diverse capabilities. Commercial solutions like ADMET Predictor provide comprehensive packages predicting over 175 properties using proprietary algorithms and high-quality training data [13]. Open-source alternatives include Chemprop, ADMETlab, and emerging initiatives like OpenADMET that focus on community-driven model development [15] [3]. These tools employ various molecular representations, with recent advances incorporating multitask learning to improve prediction of related endpoints and conformal prediction methods to define model applicability domains and estimate prediction uncertainty [14] [15].

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Framework for ADMET Prediction illustrating the transformation of molecular structures into predictive models through various representation and learning approaches.

Comparative Analysis of ADMET Prediction Tools

Performance Benchmarking Across Platforms

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial insights into the relative performance of different ADMET prediction approaches. Recent comprehensive evaluations examine multiple machine learning methods across diverse ADMET endpoints, assessing performance metrics such as area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for classification tasks and root mean square error (RMSE) for regression problems [14] [16]. These studies reveal that optimal model performance depends significantly on the specific ADMET endpoint, with different algorithms and molecular representations excelling in different prediction contexts [14]. For instance, while graph neural networks generally perform well on many toxicity endpoints, simpler random forest models sometimes outperform more complex deep learning approaches on specific metabolic stability predictions [14] [16].

Critical Assessment of Current Capabilities

Despite significant advances, current ADMET prediction tools face several challenges that impact their utility in comparative analog profiling. Data quality issues, including inconsistent experimental protocols and annotation errors across public datasets, remain a significant obstacle to model reliability [14] [3]. The "black-box" nature of many complex models also limits interpretability, making it difficult for medicinal chemists to extract actionable design guidance from predictions [3]. Furthermore, model generalization to novel chemical spaces outside training data distributions continues to present difficulties, emphasizing the importance of applicability domain assessment in practical deployment [14] [3].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Computational ADMET Prediction Platforms

| Platform | Algorithmic Approach | Key Features | Reported Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [13] | Machine learning with proprietary descriptors | Predicts 175+ properties, ADMET Risk scoring, HTPK simulations | Ranked #1 in independent peer-reviewed comparisons for several endpoints | Commercial license required, limited model customization |

| Chemprop [15] [3] | Message-passing neural networks | Multitask capability, open-source, interpretability extensions | Strong performance in molecular property prediction challenges [3] | Black-box nature, requires technical expertise for optimal use |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [15] [3] | Multiple machine learning methods | Web-based platform, 130+ endpoints, API functionality | Comprehensive coverage with improved performance over previous versions [3] | Limited model transparency, static architecture |

| Receptor.AI [3] | Multi-task deep learning with Mol2Vec | Combines embeddings with chemical descriptors, LLM consensus scoring | Enhanced accuracy through descriptor augmentation (preprint 2025) [3] | New approach with limited independent validation |

| OpenADMET [17] | Community-driven ML models | Open science initiative, regular blind challenges, structural insights | Developing high-quality datasets for model training and assessment | Early development stage, limited current model availability |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ADMET Studies

The experimental assessment of ADMET parameters requires specialized reagents, assay systems, and computational resources. This section details key components of the researcher's toolkit for comprehensive ADMET profiling.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Profiling

| Reagent/Assay System | Supplier Examples | Primary Application | Critical Function in ADMET Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | ATCC, Sigma-Aldrich | Intestinal absorption prediction | Model for human intestinal permeability and active transport mechanisms [14] [15] |

| Human Liver Microsomes | Corning, XenoTech | Metabolic stability screening | Source of CYP450 enzymes for phase I metabolism studies and clearance prediction [14] [3] |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | BioIVT, Lonza | Hepatic metabolism assessment | Intact cell system for phase I/II metabolism, transporter studies, and species comparison [3] |

| hERG Assay Kits | Eurofins, Millipore | Cardiotoxicity screening | In vitro evaluation of hERG potassium channel inhibition potential [13] [3] |

| Ames Test Strains | MolTox, EBPI | Mutagenicity assessment | Salmonella typhimurium strains for bacterial reverse mutation assay [14] |

| Plasma Protein Binding Kits | HTDialysis, Thermo Fisher | Distribution studies | Equilibrium dialysis systems for determining fraction unbound in plasma [14] |

| CYP450 Inhibition Assays | Promega, BD Biosciences | Drug-drug interaction potential | Fluorescent or luminescent substrates for evaluating CYP enzyme inhibition [3] |

| PAMPA Plates | pION, Millipore | Passive permeability | Artificial membrane system for high-throughput permeability screening [15] |

Comparative ADMET profiling of structural analogs represents a critical strategy in modern drug discovery, enabling the selection of lead compounds with optimal pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. The core ADMET parameters—absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity—provide a systematic framework for evaluating how candidate drugs interact with biological systems. While traditional experimental methods remain foundational for ADMET assessment, computational prediction tools are increasingly sophisticated and valuable for early-stage compound prioritization. The continuing evolution of both experimental and in silico approaches, particularly through advances in machine learning and high-throughput screening technologies, promises enhanced efficiency and predictive accuracy in ADMET profiling, ultimately contributing to more successful drug development outcomes.

The journey from identifying an initial "hit" compound to advancing a optimized "lead" candidate represents one of the most critical and resource-intensive phases in drug discovery. Within this process, comparative profiling has emerged as an indispensable strategy for de-risking development and maximizing the potential for clinical success. This systematic approach involves the parallel evaluation of multiple compound analogs across a comprehensive panel of biological activity, selectivity, and physicochemical property assays. The fundamental thesis underpinning this practice is that strategic, data-driven comparisons at the analog level enable more informed decision-making, ultimately yielding drug candidates with superior therapeutic profiles.

The imperative for comparative profiling stems from the sobering statistics of drug development failure. Traditional approaches long reliant on cumbersome trial-and-error have resulted in prohibitively high attrition rates, with lack of efficacy and safety concerns representing the primary causes of failure [7]. In this context, comparative ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling provides a crucial framework for identifying potential liabilities early, when chemical interventions are most feasible and cost-effective. By generating structured data that illuminates structure-activity and structure-property relationships across compound series, researchers can prioritize analogs with the optimal balance of target engagement and drug-like properties [18].

The evolution of drug discovery has further amplified the importance of rigorous profiling. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning platforms now leverage profiling data to build predictive models that accelerate design-make-test-analyze cycles [19] [20]. Similarly, pharmacometric approaches use these data to develop physiological-based models that inform clinical trial design and dosing strategies [21] [22]. This review examines the methodological framework, technological advances, and practical implementation of comparative profiling from hit-to-lead to lead optimization, providing researchers with an evidence-based guide for enhancing candidate quality and development efficiency.

The Hit-to-Lead Transition: Establishing Profiling Foundations

Objectives and Strategic Goals

The hit-to-lead (H2L) phase bridges the gap between initial screening hits and compounds worthy of extensive optimization. The primary objective is to transform chemical starting points into workable lead series with confirmed activity and promising developability profiles. This transition requires multiparameter optimization across competing objectives, where comparative profiling delivers the critical data needed to make informed trade-offs [18].

Strategic goals during H2L include confirming target engagement and mechanism of action, establishing preliminary structure-activity relationships (SAR), assessing selectivity against related targets, and evaluating initial ADMET properties. Well-designed profiling at this stage filters out compounds with fundamental flaws, allowing teams to focus resources on the most promising chemical series. The "fail early, fail cheaply" paradigm finds its greatest application here, where comprehensive analog profiling identifies critical liabilities before substantial investment in lead optimization [18].

Essential Profiling Assays and Methodologies

Hit-to-lead assays are experimental tools that help researchers evaluate whether initial "hit" compounds from a high-throughput screen can be advanced into optimized leads [18]. These assays emphasize depth and detail over pure throughput, typically measuring:

- Potency: How strongly a compound modulates its target enzyme or receptor

- Selectivity: Whether the compound interacts specifically with the target versus unrelated proteins

- Mechanism of action: Insights into how the compound binds or interferes with target function

- ADME properties: Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion characteristics that influence drug-likeness [18]

Profiling methodologies span biochemical, cell-based, and counter-screening platforms. Biochemical assays utilize cell-free systems to measure direct target interaction through techniques like fluorescence polarization, TR-FRET, or radioligand displacement. Cell-based assays add physiological relevance by evaluating compound effects in a cellular environment, measuring endpoints like reporter gene activity, signal transduction pathway modulation, or cellular proliferation. Counter-screening assays confirm selectivity and rule out off-target activity by testing compounds against panels of related targets or anti-targets [18].

Table 1: Core Assay Types for Hit-to-Lead Profiling

| Assay Category | Key Technologies | Primary Endpoints | Strategic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical | Fluorescence polarization, TR-FRET, radiometric binding | IC50, Ki, binding affinity | Confirms direct target engagement and potency |

| Cell-Based | Reporter gene, pathway modulation, viability/cytotoxicity | EC50, functional potency, efficacy | Demonstrates cellular activity and functional consequences |

| Selectivity | Panel screening, kinome profiling, GPCR panels | Selectivity scores, off-target liability | Identifies potential toxicity and specificity concerns |

| Early ADMET | Caco-2 permeability, metabolic stability, CYP inhibition | Permeability, clearance, drug-drug interaction potential | Flags developability issues before lead optimization |

Lead Optimization: Advanced Profiling for Candidate Selection

Expanding the Profiling Paradigm

Lead optimization (LO) represents the intensive process of refining a lead series to deliver a development candidate with the optimal balance of efficacy, safety, and developability. While hit-to-lead profiling focuses on identifying promising chemical series, lead optimization demands more sophisticated and expansive profiling to guide precise structural modifications. The comparative profiling paradigm expands significantly during LO to encompass detailed ADMET characterization, in vivo pharmacokinetics, and safety pharmacology assessment [23].

The fundamental objective shifts from series triage to candidate differentiation, where subtle distinctions between closely related analogs determine which compound advances to development candidate status. This requires profiling strategies that generate high-quality, comparable data across hundreds of analogs, enabling robust structure-property relationship analysis. The most successful LO campaigns employ iterative design cycles where profiling data directly informs subsequent analog design, creating a continuous feedback loop that systematically improves compound quality [19] [23].

Comprehensive ADMET Profiling Strategies

During lead optimization, ADMET profiling advances from preliminary screening to detailed characterization, with comparative data guiding critical decisions about which structural features impart desirable properties. The ADMET-score concept provides a comprehensive scoring function that evaluates drug-likeness based on 18 predicted ADMET properties, offering a unified metric for comparing analogs [7]. This scoring system integrates predictions for crucial endpoints including:

- Absorption: Human intestinal absorption, Caco-2 permeability

- Distribution: Plasma protein binding, P-glycoprotein substrate/inhibition

- Metabolism: CYP450 inhibition (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4), CYP450 substrate specificity

- Excretion: Renal clearance predictions

- Toxicity: Ames mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, hERG inhibition, acute oral toxicity [7]

Modern LO platforms leverage both in silico predictions and experimental data to build comprehensive ADMET profiles. Companies like Schrödinger have developed integrated platforms that combine physics-based simulations with machine learning to predict key properties including membrane permeability, hERG inhibition, CYP inhibition, brain exposure, and solubility [23]. This computational-guided approach enables prioritization of synthetic targets before resource-intensive chemistry, exemplifying the "predict-first" philosophy that maximizes efficiency in LO.

Technological Enablers of Comparative Profiling

AI and Machine Learning Platforms

Artificial intelligence has transformed comparative profiling from a retrospective analytical tool to a prospective design aid. AI-driven platforms can decode intricate structure-activity relationships, facilitating de novo generation of bioactive compounds with optimized pharmacokinetic properties [20]. The efficacy of these algorithms is intrinsically linked to the quality and volume of profiling data used for training, particularly in deciphering latent patterns within complex biological datasets [20].

Companies leading in this space have demonstrated remarkable efficiencies. Exscientia reports in silico design cycles approximately 70% faster and requiring 10-fold fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [19]. In one program, a CDK7 inhibitor achieved clinical candidate status after synthesizing only 136 compounds, whereas traditional programs often require thousands [19]. Similarly, Schrödinger's platform enables researchers to profile billions of virtual target-specific molecules through intelligent, reaction-based enumeration and accurate FEP+ scoring workflows [23].

Integrated Software Solutions

Specialized software platforms have emerged as essential tools for managing and interpreting the complex data generated through comparative profiling. These solutions provide environments for chemical enumeration, property prediction, and team collaboration, enabling research teams to deploy a 'predict-first' approach to lead optimization challenges [23] [24].

Table 2: Leading Software Platforms for Comparative Profiling

| Platform | Key Features | Profiling Strengths | ADMET Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger | FEP+, WaterMap, LiveDesign | Free energy calculations, binding affinity prediction | hERG, CYP inhibition, permeability, solubility |

| deepmirror | Generative AI engine, protein-drug binding prediction | Hit-to-lead optimization, molecular property prediction | ADMET liability reduction, potency and ADME prediction |

| Chemical Computing Group (MOE) | Molecular modeling, cheminformatics | Structure-based design, QSAR modeling | ADMET prediction, protein engineering |

| Optibrium (StarDrop) | AI-guided optimization, sensitivity analysis | Compound prioritization, library design | ADME and physicochemical property QSAR models |

| Cresset (Flare) | Protein-ligand modeling, FEP enhancements | Electrostatic property analysis, binding site mapping | MM/GBSA binding free energy calculations |

Automation and High-Throughput Experimental Systems

The practical implementation of comparative profiling relies heavily on automated and miniaturized assay systems that enable rapid data generation across analog series. Modern laboratories employ robotic workstations like the Tecan Genesis to execute critical ADMET assays, including Caco-2 permeability, metabolic stability in liver microsomes, and CYP450 inhibition [25]. This automation enables the generation of reliable profiles for structure-activity or structure-property relationships of compounds from screening "hit sets" or libraries, making the identification of discovery compounds with desirable "druglike" properties increasingly data-driven [25].

The integration of AI-driven analysis with automated screening platforms represents the cutting edge of profiling technology. Robotic automation reduces human error and enables large-scale profiling with reproducibility, while AI tools can predict likely off-target interactions and help prioritize assays [18]. This synergy creates a powerful ecosystem for comparative profiling, where data integration allows seamless progression from HTS to H2L to lead optimization.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Workflow Design for Analog Profiling

A structured, tiered profiling approach ensures efficient resource allocation while generating comprehensive data for analog comparison. The following workflow visualization illustrates a robust profiling strategy from hit-to-lead through lead optimization:

Key Experimental Protocols

ADMET-Score Calculation Protocol

The ADMET-score provides a comprehensive metric for comparing analog drug-likeness [7]. The experimental and computational protocol involves:

Endpoint Selection: 18 ADMET properties are evaluated, including Ames mutagenicity, acute oral toxicity, Caco-2 permeability, carcinogenicity, CYP450 inhibition profiles (1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, 3A4), CYP450 substrate specificity, CYP inhibitory promiscuity, hERG inhibition, human intestinal absorption, organic cation transporter protein 2 inhibition, P-gp inhibition, and P-gp substrate potential [7].

Prediction Methodology: Properties are predicted using the admetSAR 2.0 web server or equivalent platforms, which employ machine learning models (support vector machines, random forests, k-nearest neighbors) trained on curated chemical databases using molecular fingerprints for structure representation [7].

Scoring Algorithm: The ADMET-score integrates predictions through a weighted function considering model accuracy, endpoint importance in pharmacokinetics, and usefulness index. The resulting score enables direct comparison of analogs, with established thresholds differentiating drug-like from non-drug-like compounds [7].

Validation: Performance is validated against known drugs (DrugBank), chemical databases (ChEMBL), and withdrawn drugs, demonstrating significant differentiation between these classes [7].

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol for Binding Affinity Prediction

FEP+ calculations provide high-precision binding affinity predictions for analog comparison [23]:

System Preparation: Protein structures are prepared using standard protein preparation workflows, including hydrogen addition, bond order assignment, and optimization of hydrogen bonding networks. Ligands are prepared with accurate ionization states and tautomer enumeration.

Molecular Dynamics Parameters: Simulations are performed using explicit solvent models with OPLS3 or OPLS4 force fields. Desmond molecular dynamics engine runs simulations with 2 fs time steps under NPT conditions at 300 K.

Free Energy Calculations: The FEP+ workflow employs a hybrid topology approach to mathematically "morph" between ligand pairs. Each transformation involves 12 lambda windows of 5-20 ns each, with replica exchange sampling enhancing conformational exploration.

Analysis and Validation: ΔΔG values are calculated using Bennetts Acceptance Ratio or Multistate Bennetts Acceptance Ratio. Method validation includes comparison with experimental binding data for known ligands, with typical accuracy of ~1.0 kcal/mol corresponding to ~5-fold in binding affinity [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Profiling Assays

| Reagent/Cell Line | Vendor Examples | Primary Application | Profiling Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 cells | ATCC, Sigma-Aldrich | Intestinal permeability prediction | Absorption potential ranking for analogs |

| Human liver microsomes | Corning, XenoTech | Metabolic stability assessment | Comparative clearance predictions |

| Recombinant CYP450 enzymes | BD Biosciences, Thermo Fisher | CYP inhibition screening | Drug-drug interaction risk assessment |

| hERG-expressing cells | Charles River, Eurofins | Cardiac safety screening | Torsades de pointes risk comparison |

| Transcreener assays | Bellbrook Labs | Biochemical assay platforms | Uniform assay format for selectivity panels |

| Equilibrium dialysis plates | HTDialysis, Thermo Fisher | Plasma protein binding measurement | Free fraction comparison across analogs |

Case Studies: Comparative Profiling in Action

AI-Driven Lead Optimization: Exscientia and Insilico Medicine

AI-platform companies have demonstrated the power of data-driven comparative profiling in accelerating drug discovery. Exscientia's "Centaur Chemist" approach integrates algorithmic design with human expertise to iteratively design, synthesize, and test novel compounds [19]. By incorporating patient-derived biology through acquisition of Allcyte, the platform enables high-content phenotypic screening of AI-designed compounds on real patient tumor samples, ensuring translational relevance beyond traditional biochemical assays [19].

Notable outcomes include the development of a CDK7 inhibitor that achieved clinical candidate status after synthesizing only 136 compounds, compared to industry norms of thousands [19]. Similarly, Insilico Medicine's generative-AI-designed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, substantially faster than the typical 5-year timeline for conventional approaches [19]. These cases highlight how comparative profiling data fuels AI algorithms, creating a virtuous cycle of compound optimization.

Integrated Platform Approach: Schrödinger

Schrödinger's platform exemplifies how integrated computational and experimental profiling enhances lead optimization. In one case study, researchers rapidly discovered a novel MALT1 inhibitor, progressing from hit to development candidate in just 10 months [23]. The platform combined FEP+ calculations for potency prediction, WaterMap analysis of hydration site thermodynamics, and machine learning-based ADMET profiling to prioritize analogs with optimal properties.

The platform's "predict-first" approach enabled researchers to profile billions of virtual compounds in silico before synthesizing only the most promising candidates [23]. LiveDesign facilitated real-time collaboration and data sharing, ensuring that profiling results immediately informed chemical design. This case demonstrates how comprehensive comparative profiling, integrating both computational and experimental data, dramatically accelerates the identification of high-quality development candidates.

Comparative profiling from hit-to-lead to lead optimization represents a foundational strategy in modern drug discovery. The systematic, data-rich comparison of analogs across multiple parameters enables researchers to make informed decisions that balance potency, selectivity, and developability. As AI and automation technologies continue to advance, the scope, quality, and impact of comparative profiling will only increase, further accelerating the delivery of innovative medicines to patients.

The most successful drug discovery organizations recognize comparative profiling not as a series of disconnected assays, but as an integrated knowledge-generating engine. By implementing tiered profiling strategies, leveraging advanced computational tools, and maintaining focus on critical decision points, research teams can maximize the value of every synthesized compound and enhance the probability of technical and regulatory success.

In contemporary drug discovery, the comparative profiling of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties for analog series represents a critical methodology for optimizing candidate compounds. Early assessment of these pharmacokinetic and safety parameters allows researchers to identify molecules with the highest potential for clinical success, thereby reducing late-stage attrition rates. The foundation of effective ADMET profiling rests upon access to high-quality, well-curated data resources. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three essential public databases—ChEMBL, PubChem, and the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC)—that support ADMET predictive modeling and analog profiling research. By examining their respective structures, data content, and benchmarking capabilities, this analysis equips researchers with the knowledge to select appropriate resources for their specific drug discovery workflows.

Resource Descriptions and Primary Functions

ChEMBL is a manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, primarily sourced from medicinal chemistry literature and containing extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) data [26]. Its content includes quantitative binding, functional, and ADMET information for drug discovery applications.

PubChem serves as a comprehensive repository of chemical substances and their biological activities, aggregating data from hundreds of sources including high-throughput screening programs and scientific literature [26]. It provides both chemical structures and associated bioactivity data for a diverse range of compounds.

Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) functions as a unified platform that aggregates, standardizes, and benchmarks datasets for machine learning applications in therapeutics development [27] [4]. Its ADMET benchmark group specifically curates datasets for fair comparison of predictive models in drug discovery.

Quantitative Database Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ADMET Databases

| Resource | Primary Focus | Data Curation Level | ADMET-Specific Content | Benchmarking Capabilities | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Bioactive molecules & SAR data | Manual expert curation | Extensive ADMET endpoints from literature | Limited built-in benchmarking | Regular releases (quarterly) |

| PubChem | Chemical substances & bioactivities | Automated aggregation with some curation | Diverse bioactivity data including some ADMET | No specific ADMET benchmarking | Continuous updates |

| TDC | Machine learning readiness | Standardized curation for ML | Dedicated ADMET benchmark group (22 datasets) | Comprehensive leaderboard & evaluation metrics | Periodic version updates |

Table 2: ADMET Benchmark Group Dataset Summary from TDC

| ADMET Category | Example Datasets | Dataset Sizes | Task Types | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Caco-2, HIA, Bioavailability | 578-9,982 compounds | Classification & Regression | MAE, AUROC |

| Distribution | BBB, PPBR, VDss | 1,130-1,975 compounds | Classification & Regression | MAE, AUROC, Spearman |

| Metabolism | CYP Inhibition/Substrate | 664-13,130 compounds | Classification | AUPRC, AUROC |

| Excretion | Half Life, Clearance | 667-1,102 compounds | Regression | Spearman |

| Toxicity | hERG, Ames, DILI | 475-7,385 compounds | Classification & Regression | MAE, AUROC |

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization

Standardized Benchmarking Using TDC

The TDC framework provides a systematic approach for evaluating ADMET prediction models through its benchmark group. The experimental workflow involves:

Data Retrieval and Splitting:

TDC employs scaffold splitting to partition datasets into training, validation, and test sets, simulating real-world scenarios where models encounter structurally novel compounds [4]. This method ensures that evaluation reflects performance on chemically distinct molecules rather than random splits that may overestimate accuracy.

Model Evaluation Metrics: For regression tasks, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is typically used, while Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) are employed for classification tasks [4] [28]. Spearman's correlation coefficient is utilized for specific distribution-related endpoints like VDss, which depend on factors beyond chemical structure alone [4].

Data Extraction and Curation Protocols

Advanced Curation Using Large Language Models: Recent advancements incorporate Large Language Models (LLMs) for extracting experimental conditions from unstructured assay descriptions in databases like ChEMBL [29]. This multi-agent system identifies critical parameters such as pH conditions, measurement techniques, and biological models that significantly influence ADMET measurements.

Data Standardization Workflow:

- Compound Standardization: Normalization of chemical structures, removal of salts, and tautomer standardization [30]

- Duplicate Resolution: Identification and resolution of conflicting measurements for the same compound [29]

- Condition Filtering: Application of inclusion criteria based on relevant experimental conditions (e.g., pH = 7.4 for logD measurements) [29]

- Value Transformation: Appropriate transformation of skewed distributions (e.g., log-transformation for solubility data) [30]

Visualization of ADMET Data Workflows

ADMET Predictive Modeling Pipeline

Diagram 1: Integrated ADMET Predictive Modeling Workflow illustrating how multiple databases contribute to model development and evaluation.

Sequential ADME Multi-Task Learning Architecture

Diagram 2: Sequential ADME Multi-Task Learning Architecture demonstrating the A→D→M→E flow that mirrors pharmacological principles to enhance prediction accuracy [27].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Findings

Model Performance Across ADMET Endpoints

Table 3: Representative Model Performance on TDC ADMET Benchmarks

| ADMET Endpoint | Best Performing Model | Performance Metric | Score | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | XGBoost with Feature Ensemble | MAE | 0.234 | Outperformed graph neural networks [28] |

| BBB Penetration | XGBoost with Feature Ensemble | AUROC | 0.954 | Top-ranked performance among 8+ models [28] |

| CYP2C9 Inhibition | XGBoost with Feature Ensemble | AUPRC | 0.902 | Superior to attentive FP and GCN models [28] |

| hERG Toxicity | ADME-DL Sequential MTL | AUROC | +2.4% improvement | State-of-the-art enhancement over baselines [27] |

Experimental results demonstrate that tree-based ensemble methods like XGBoost, when combined with comprehensive feature ensembles (including molecular fingerprints and descriptors), achieve competitive performance across multiple ADMET prediction tasks [28]. The ADME-DL framework, which incorporates sequential multi-task learning following the A→D→M→E pharmacological flow, shows improvements of up to +2.4% over state-of-the-art baselines and enhances performance across tested molecular foundation models by up to +18.2% [27].

Impact of Data Quality and Representation

Studies comparing model performance highlight the critical importance of data quality and feature representation. Research indicates that systematic feature selection and appropriate molecular representations significantly impact model performance, with concatenated feature ensembles often yielding superior results compared to single representation approaches [30]. Furthermore, cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing provides more robust model comparison than simple hold-out test set evaluations, particularly given the noise inherent in ADMET datasets [30].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for ADMET Profiling Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in ADMET Profiling | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | Generation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Open-source Python library [30] [28] |

| ADMETboost | Web server for prediction | Accurate ADMET prediction using ensemble XGBoost models | Public web server [28] |

| ADMET Predictor | Commercial AI/ML platform | Prediction of 175+ ADMET properties with enterprise workflows | Commercial license [13] |

| Mordred Descriptors | Molecular descriptor calculator | Comprehensive 2D/3D molecular descriptor generation | Open-source Python package [28] |

| PharmaBench | Extended benchmark dataset | Enhanced ADMET modeling with 52,482 entries across 11 properties | Publicly available dataset [29] |

For researchers engaged in comparative ADMET profiling of analog series, the selection of appropriate databases depends on specific research objectives. ChEMBL offers depth with manually curated bioactivity data, PubChem provides breadth through extensive compound coverage, and TDC delivers standardized benchmarks for method comparison. Experimental evidence indicates that combining multiple molecular representations with ensemble methods like XGBoost typically yields robust predictive performance. The emerging paradigm of sequential multi-task learning that respects pharmacological hierarchies (A→D→M→E) shows particular promise for enhancing prediction accuracy. As the field advances, initiatives like OpenADMET that focus on generating high-quality, consistent experimental data specifically for model development will address current limitations in data quality and reproducibility, further accelerating predictive ADMET profiling in drug discovery pipelines [17].

Methodologies for Analog Profiling: From In Silico Predictions to Experimental Assays

The optimization of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is a critical determinant of success in drug discovery, with inadequate profiles accounting for a significant proportion of clinical-stage failures [31] [32]. In silico tools have emerged as indispensable assets for predicting these properties early in the development pipeline, offering cost and time efficiencies while reducing reliance on animal testing [33]. This review provides a comparative analysis of three web-based platforms—OptADMET, ChemMORT, and ADMETlab 2.0—framed within the context of comparative ADMET profiling of analog series. We evaluate their predictive performance, scope of property coverage, and practical utility for researchers engaged in lead optimization, supported by experimental benchmarking data and detailed methodological protocols.

Platform Capabilities at a Glance

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison of ADMET Prediction Platforms

| Feature | ADMETlab 2.0 | OptADMET | ChemMORT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Comprehensive ADMET profiling [32] [34] | Lead optimization via transformation rules [35] [36] | Information not available in search results |

| Number of Endpoints | 88 properties & 8 toxicophore rules [34] | 32 ADMET properties [35] | Not specified |

| Key Technology | Multi-task Graph Attention (MGA) framework [32] [34] | Matched Molecular Pairs analysis [35] [36] | Not specified |

| Data Foundation | ~0.25 million experimental data points [32] | 177,191 experimental + 239,194 predicted data points [36] | Not specified |

| Batch Screening | Supported (SDF/TXT file) [34] | Implied via optimization suggestions | Not specified |

| Access | Free, no registration [32] | Free web server [35] | Not specified |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial insights into the real-world performance of computational ADMET tools. A large-scale assessment of twelve QSAR tools evaluated models for 17 physicochemical (PC) and toxicokinetic (TK) properties, finding that models for PC properties (average R² = 0.717) generally outperformed those for TK properties (average R² = 0.639 for regression; average balanced accuracy = 0.780 for classification) [31]. This analysis emphasized validating predictions within the models' applicability domain, a critical consideration for reliable application in research.

ADMETlab 2.0 employs a multi-task graph attention framework trained on a structurally diverse dataset of approximately 0.25 million entries, which supports robust predictions across a wide chemical space [32]. The platform provides regression values for continuous endpoints (e.g., Caco-2 permeability) and probability ranges for classification endpoints, with a recommended cautious interpretation for probabilities falling between 0.3-0.7 [32].

OptADMET takes a different approach, leveraging 41,779 validated transformation rules derived from the analysis of 177,191 reliable experimental datasets [35] [36]. This methodology provides medicinal chemists with specific, data-driven guidance on which substructural modifications are most likely to improve multiple ADMET parameters simultaneously.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking ADMET Tools

Standardized Workflow for Tool Evaluation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental protocol for benchmarking the predictive performance of ADMET in silico tools, synthesized from methodologies described in the search results.

Detailed Methodological Components

1. Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Source Identification: Collect experimental ADMET datasets from publicly available repositories such as ChEMBL, PubChem, and peer-reviewed literature [31] [6].

- Structural Standardization: Standardize molecular structures using tools like RDKit, including neutralization of salts, removal of duplicates, and normalization of tautomers [31] [30].

- Data Quality Control: Implement Z-score analysis to identify and remove response outliers (typically |Z-score| > 3), and resolve inconsistent measurements for compounds appearing across multiple datasets [31].

- Chemical Space Analysis: Assess structural diversity of the validation set through scaffold analysis to ensure representative coverage of the chemical space relevant to drug discovery [32] [6].

2. Prediction Generation and Performance Validation

- Model Prediction: Input curated validation sets into each platform using batch processing capabilities where available [32] [34].

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Applicability Domain Assessment: Evaluate whether prediction chemicals fall within the model's applicability domain, as performance typically degrades for compounds outside this domain [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational Resources for ADMET Profiling Research

| Resource Category | Example Tools | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit [30] [32] | Provides fundamental cheminformatics functions including descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and SMILES standardization |

| Web-Based Prediction Platforms | ADMETlab 2.0, OptADMET [32] [35] | Offer user-friendly interfaces for ADMET property prediction without requiring local installation |

| Data Curation & Standardization | Custom Python scripts, DataWarrior [31] [30] | Enable processing of chemical structures and experimental data to ensure consistency |

| Benchmark Datasets | PharmaBench, TDC [30] [6] | Provide standardized datasets for model training and validation |

| Molecular Representation | Morgan Fingerprints, Graph Neural Networks [30] [37] | Convert chemical structures into machine-readable formats for modeling |

ADMETlab 2.0 and OptADMET represent complementary approaches to in silico ADMET profiling, with the former excelling in comprehensive property assessment and the latter specializing in guiding lead optimization through structural transformation rules. Independent benchmarking confirms that while current tools achieve adequate predictive performance for many properties, careful attention to applicability domains remains crucial. For researchers engaged in comparative ADMET profiling of analogs, these platforms offer powerful capabilities for prioritizing compounds with the highest likelihood of success, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery process while reducing late-stage attrition due to unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicity profiles.

In contemporary pharmaceutical research, accurately predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has become crucial for reducing late-stage clinical failures and optimizing drug candidates. The traditional drug discovery process typically requires over $2.6 billion and 10-15 years per approved drug, with only 1 in 5,000 discovered compounds ultimately reaching market approval [38]. Within this challenging landscape, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology, particularly transformer models and hybrid tokenization approaches that enhance molecular property prediction. These computational methods have evolved from early quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and structure-based drug design to modern deep learning architectures that can process complex molecular representations [38]. The integration of AI into drug discovery represents not a replacement of established approaches but rather the development of complementary tools that augment human expertise and traditional computational chemistry methods [38]. This comparative analysis examines the performance, methodologies, and applications of transformer architectures and hybrid tokenization strategies in ADMET prediction, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate computational approaches within comparative ADMET profiling of analogs research.

Transformer Architectures in Molecular Property Prediction

Fundamental Architecture and Adaptation to Molecular Data

Transformer models have revolutionized molecular property prediction through their unique architectural features and exceptional performance in managing intricate data landscapes. Originally developed for natural language processing, transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and complex relationships within sequential data [39]. For molecular applications, transformers typically process Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings, which provide a textual representation of chemical structures using characters like "C" for carbon, "=" for double bonds, and parentheses for branches [40]. The self-attention mechanism enables these models to weigh the importance of different molecular substructures when making property predictions, allowing them to capture complex structure-activity relationships that traditional machine learning methods might miss [39] [41].

The adaptability of pre-trained transformer-based models has made them indispensable assets for data-centric advancements in drug discovery, chemistry, and biology [39]. These models typically follow a pre-training and fine-tuning paradigm, where they are first trained on large unlabeled molecular datasets (sometimes containing billions of molecules) using objectives like masked language modeling (MLM), then fine-tuned on smaller, labeled ADMET datasets for specific prediction tasks [41]. This approach allows transformers to learn general chemical principles during pre-training and subsequently apply this knowledge to specialized prediction tasks with limited labeled data, addressing a fundamental challenge in computational drug discovery where high-quality experimental ADMET data is often scarce and expensive to obtain [41].

Domain Adaptation Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Recent research has revealed that simply increasing pre-training dataset size provides diminishing returns for molecular property prediction. Studies demonstrate that performance improvements plateau at approximately 400,000-800,000 molecules, suggesting significant redundancy in larger molecular databases [41]. Instead, domain adaptation strategies have emerged as more effective approaches for enhancing transformer performance in ADMET prediction.

Domain adaptation through chemically informed objectives has shown particularly promising results. One effective method involves multi-task regression (MTR) of physicochemical properties during domain adaptation, where the model is further trained on a small number of domain-relevant molecules (≤4,000) to predict multiple physicochemical properties simultaneously [41]. This approach significantly improves model performance across diverse ADMET datasets, outperforming models trained on much larger general molecular databases without domain-specific adaptation [41].

Alternative domain adaptation strategies include contrastive learning (CL) of different SMILES representations of the same molecules and functional group masking approaches. The MLM-FG model, for instance, employs a novel pre-training strategy that randomly masks subsequences corresponding to chemically significant functional groups, compelling the model to better infer molecular structures and properties by learning the context of these key units [42]. This method has demonstrated superior performance compared to standard masking approaches, outperforming existing SMILES- and graph-based models in 9 out of 11 benchmark tasks [42].

Hybrid Tokenization Approaches

Fundamental Concepts and Implementation

Hybrid tokenization represents an innovative approach to molecular representation that combines fragment-based and character-level SMILES tokenization. Traditional SMILES tokenization breaks molecules into individual characters or short sequences, potentially overlooking important chemical motifs, while fragmentation approaches decompose molecules into chemically meaningful substructures but face challenges with fragment size variability and rare fragments [40]. Hybrid tokenization addresses these limitations by integrating both representations within a unified framework.

The implementation of hybrid tokenization typically begins with the decomposition of molecules into fragments using algorithmic approaches. These fragments are then filtered based on frequency thresholds to create a fragment library, with studies investigating various cutoff values to optimize performance [40]. High-frequency fragments are retained as tokens, while low-frequency fragments and atomic constituents are represented using standard SMILES tokenization. This hybrid approach is coupled with transformer architectures, such as the MTL-BERT model, which utilizes an encoder-only transformer optimized for multi-task learning in ADMET prediction [40].

Comparative Performance Analysis