Bridging the Prediction Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating In Silico ADMET Models with In Vitro Data

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to effectively validate in silico ADMET predictions with robust in vitro data.

Bridging the Prediction Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating In Silico ADMET Models with In Vitro Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to effectively validate in silico ADMET predictions with robust in vitro data. As the pharmaceutical industry increasingly relies on computational tools to accelerate discovery, bridging the gap between prediction and experimental validation is critical for reducing late-stage attrition. We explore the foundational principles of ADMET modeling, detail advanced methodological and integrated application workflows, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation and comparative strategies. By synthesizing current trends, including the use of AI and complex in vitro models, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and regulatory acceptance of in silico-in vitro integrated approaches in preclinical development.

The Critical Need for ADMET Validation in Modern Drug Discovery

Why Predictive ADMET is a Cornerstone for Reducing Clinical Attrition

The pharmaceutical industry faces a formidable challenge: the overwhelming majority of drug candidates fail to reach the market, often after substantial investments have been made in clinical trials. A primary reason for these late-stage failures is unsatisfactory profiles in Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET). Poor ADMET properties account for approximately 50-60% of clinical phase failures, highlighting a critical bottleneck in the drug development pipeline [1] [2]. This high attrition rate translates into staggering costs, with the average new drug requiring nearly $2.6 billion and 12-15 years to develop [3].

The traditional drug discovery approach, which tested ADMET properties relatively late in the process, has proven economically and temporally unsustainable. Consequently, the industry has undergone a significant strategic shift, now performing extensive ADMET screening considerably earlier in the drug discovery process [1]. This paradigm shift positions predictive ADMET as a cornerstone strategy for de-risking drug development. By identifying and eliminating problematic compounds before they enter costly clinical phases, in silico (computational) ADMET prediction saves both money and time, boosting overall medication development efficiency [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this translates into a workflow where computational models are no longer auxiliary tools but fundamental components for making critical go/no-go decisions on candidate compounds.

The Evolution and Methodologies ofIn SilicoADMET Prediction

The field of in silico ADMET prediction has evolved dramatically from simple quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) platforms. This evolution has been driven by the accumulation of large-scale experimental data and advances in computational algorithms.

Fundamental Computational Approaches

At its core, predictive ADMET relies on a suite of computational methods that span different levels of complexity and mechanistic insight:

- Quantum Mechanics (QM) and Molecular Mechanics (MM): These methods provide deep mechanistic insights, particularly for understanding metabolic processes. For instance, QM/MM simulations have been used to study the metabolism of camphor by bacterial P450 enzymes and to examine the regioselectivity of estrone metabolism in humans, helping to predict which specific positions in a molecule are most susceptible to oxidation by CYP enzymes [1].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR/QSPR): These traditional yet powerful approaches establish quantitative relationships between molecular descriptors (physicochemical properties, topological structures, etc.) and ADMET endpoints. Commercial tools like ADMET Predictor extensively use QSPR models, constructing predictions for over 220 properties that comprehensively cover a compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic parameters [4].

- Molecular Docking and Pharmacophore Modeling: These techniques are particularly valuable for predicting specific interactions, such as a compound's binding to metabolic enzymes (e.g., CYP450) or toxicity-related receptors like the hERG channel [1].

The Rise of Machine Learning and AI

Modern ADMET prediction has been revolutionized by machine learning and artificial intelligence, which can model complex, non-linear structure-property relationships that are difficult to capture with traditional methods [5]. Key ML approaches include:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These methods represent molecules as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) and can directly learn from molecular structure without relying on pre-defined descriptors. Platforms like ADMETlab 3.0 use Directed Message Passing Neural Networks (DMPNN) to achieve state-of-the-art prediction performance [6].

- Multitask Learning (MTL): This framework allows simultaneous prediction of multiple ADMET endpoints by sharing representations across related tasks, improving data efficiency and model robustness [5].

- Ensemble Methods: These combine predictions from multiple base models (e.g., decision trees, neural networks) to create more robust and accurate consensus predictions, effectively addressing challenges like limited data availability and high model uncertainty [5].

The performance of these models is heavily dependent on the quality and quantity of training data. Leading platforms are trained on massive datasets; for example, ADMETlab 3.0 incorporates over 400,000 data entries across 119 endpoints, while some commercial tools additionally integrate proprietary data from pharmaceutical industry partners to enhance model accuracy [4] [6].

Comparative Analysis of Leading ADMET Prediction Platforms

The landscape of ADMET prediction tools is diverse, ranging from open-source packages to comprehensive commercial suites. The table below provides a structured comparison of several prominent platforms, highlighting their respective capabilities, data coverage, and primary applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Leading ADMET Prediction Platforms

| Platform Name | Type/Availability | Key Features | Model Foundation | Endpoint Coverage | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMET Predictor [4] | Commercial Software | - ADMET Risk scoring based on 2,260 marketed drugs- High-throughput PK (HTPK) module- Structure Sensitivity Analysis (SSA)- Predicts 220+ properties | QSPR models combined with AI algorithms | Covers physicochemical properties, transporters, metabolism, toxicity, and PK parameters | Early compound screening, formulation design, toxicity mitigation, dose prediction |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [6] | Free Web Platform | - Covers 119 endpoints (77 modeled, 42 calculated)- API for programmatic access- Uncertainty estimation for predictions- Molecular comparison tools | DMPNN-Des (Graph Neural Network + RDKit 2D descriptors) | Extensive coverage of physicochemical, ADME, and toxicity properties | Academic research, virtual screening, lead optimization |

| ADMET-AI [7] | Open-Source | - Fast prediction speed- Benchmarks against approved drugs in DrugBank- Provides percentile ranks relative to reference drugs- Easy integration via Python API | Chemprop-RDKit Graph Neural Network | 41 ADMET datasets from TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons) | Early-stage compound prioritization, relative risk assessment |

| SwissADME [6] | Free Web Tool | - User-friendly interface- Key physicochemical and pharmacokinetic descriptors- Drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski, Veber) | Combination of rule-based and ML models | Focuses on key physicochemical properties and absorption-related parameters | Quick initial profiling, educational use |

Performance and Accuracy Considerations

When evaluating these platforms, predictive accuracy remains the paramount criterion. Independent literature validations have shown that several commercial and academic tools achieve high performance. For instance, ADMET Predictor's models for key properties like logP (a measure of lipophilicity), fraction unbound in plasma (fup), and P-gp substrate identification have demonstrated strong concordance with experimental data [4]. Similarly, ADMETlab 3.0 reports R² values for regression tasks primarily between 0.75 and 0.95, and AUC values for classification tasks ranging from 0.72 to 0.99, indicating robust predictive power across diverse endpoints [6].

A critical differentiator among modern platforms is the inclusion of Uncertainty Quantification (UQ). Tools like ADMETlab 3.0 and ADMET-AI provide estimates of prediction confidence, which is crucial for prioritizing compounds in virtual screening. ADMETlab 3.0 implements an evidence-based approach for regression models and Monte Carlo dropout for classification models to assess uncertainty [6]. This functionality helps researchers identify when a prediction is outside the model's reliable "applicability domain," reducing the risk of decisions based on unreliable forecasts.

ValidatingIn SilicoPredictions withIn VitroandIn VivoData

The true test of any in silico model is its ability to correlate with empirical data. The validation of ADMET predictions follows a hierarchical approach, moving from in vitro assays to in vivo studies, with each step providing a more complex layer of confirmation.

Key Experimental Protocols for Validation

To establish a robust validation framework for in silico ADMET predictions, researchers employ a suite of standardized experimental protocols. The table below details key methodologies that serve as benchmarks for computational forecasts.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Validating ADMET Predictions

| ADMET Property | Experimental Protocol | Brief Description & Function | Key Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Caco-2 Permeability Assay [8] | Uses human colon adenocarcinoma cell monolayers to model intestinal absorption. | Apparent Permeability (Papp), predicts absorption rate (ka) and fraction absorbed (Fa). |

| Metabolism | Liver Microsome/Hepatocyte Stability [8] | Incubates test compound with liver enzymes to measure metabolic degradation. | Intrinsic Clearance (CLint), used in IVIVE to predict in vivo hepatic clearance (CL). |

| Toxicity | hERG Inhibition Assay [7] | Measures compound's potential to block the hERG potassium channel, linked to cardiac arrhythmia. | IC50 value (concentration causing 50% inhibition); predictive of Torsades de Pointes risk. |

| Distribution | Plasma Protein Binding [8] | Determines the fraction of drug bound to plasma proteins vs. free (pharmacologically active). | Fraction unbound (fup); critical for correcting clearance and volume of distribution predictions. |

| Distribution | P-gp Transporter Assay [4] | Evaluates if a compound is a substrate or inhibitor of the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter. | Efflux ratio; predicts potential for drug-drug interactions and tissue penetration (e.g., BBB). |

These experimental protocols provide the essential ground-truth data against which in silico predictions are validated. The relationship between computational prediction and experimental validation can be visualized as an iterative cycle that refines model accuracy and informs drug design.

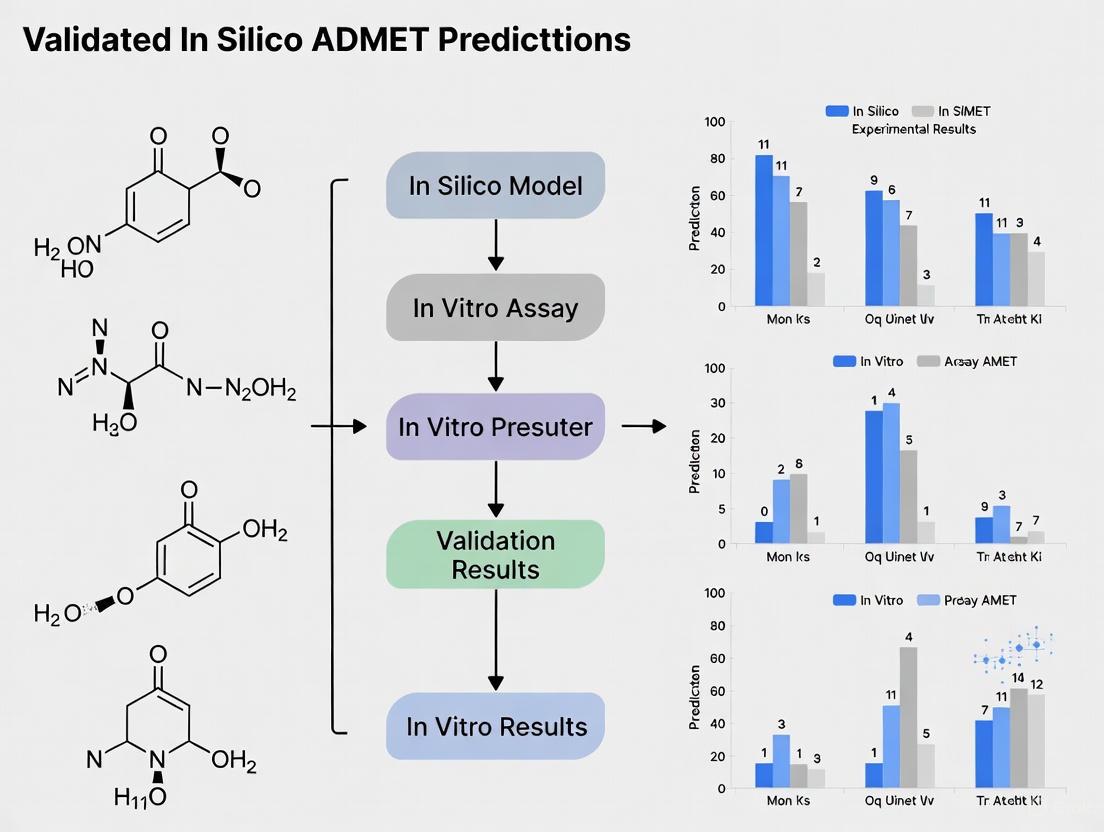

Diagram Title: ADMET Prediction and Validation Workflow

Case Studies: Integrating Prediction with Experimental Data

Concrete examples illustrate the power and limitations of integrating in silico predictions with experimental data:

GSK3β Inhibitors and hERG Toxicity: A study using the open-source tool ADMET-AI demonstrated its ability to predict the hERG cardiotoxicity risk of two GSK3β inhibitors. The tool correctly predicted a high probability (0.98) of hERG inhibition for a problematic compound (Cmpd 1, experimental hERG IC50 = 44 nM) and a lower probability (0.73) for an optimized analog (Cmpd 14). However, it is noteworthy that Cmpd 14 was still classified as a hERG inhibitor by the model despite an experimental IC50 >100 µM, highlighting a potential area for model refinement concerning negative prediction accuracy [7].

MET Inhibitor and CYP3A4 Time-Dependent Inhibition (TDI): ADMET-AI was used to retrospectively predict the CYP3A4 inhibition risk for a MET inhibitor (compound 13) and its N-desmethyl metabolite. The model predicted a high probability of CYP3A4 inhibition for both, especially the metabolite (0.849), corroborating experimental findings that the metabolite was a potent inhibitor (Ki = 105 nM). This case shows how in silico tools can predict metabolic activation leading to toxicity, a critical consideration in drug design [7].

These case studies underscore that while in silico tools are powerful for risk stratification and prioritization, they are most effective when used in concert with experimental data rather than as standalone arbiters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Validating in silico ADMET predictions requires a well-characterized set of biological reagents and assay systems. The following table details key materials essential for conducting the experimental protocols outlined in the previous section.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Experimental Validation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in ADMET Assessment |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line [8] | A model of the human intestinal epithelium used to predict oral absorption and permeability of drug candidates. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) / Cryopreserved Hepatocytes [8] | Enzyme systems derived from human liver tissue used to study metabolic stability, clearance, and metabolite identification. |

| HEK293 Cells Expressing hERG Channel [7] | A cell line engineered to express the human Ether-à-go-go Related Gene potassium channel, crucial for assessing cardiotoxicity risk. |

| Human Plasma [8] | Used in equilibrium dialysis or ultrafiltration experiments to determine the extent of plasma protein binding (fraction unbound, fup). |

| MDR1-MDCK II Cell Line [4] | Canine kidney cells expressing the human P-glycoprotein (MDR1) transporter, used to assess efflux potential and blood-brain barrier penetration. |

Predictive ADMET has unequivocally established itself as a cornerstone for reducing clinical attrition. By enabling the early identification of compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles, in silico tools directly address the leading cause of failure in drug development. The continuous improvement of AI and ML models, coupled with the expansion of high-quality biological data, is steadily increasing the accuracy and reliability of these predictions. The future of the field lies in the tighter integration of computation and experimentation, where in silico predictions not only guide experimental design but are also continuously refined by experimental results. This virtuous cycle, supported by robust validation protocols and a clear understanding of each tool's strengths and limitations, promises to streamline the drug development pipeline, increase success rates, and ultimately accelerate the delivery of safer and more effective medicines to patients.

The assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical gatekeeper in drug discovery, determining whether promising drug candidates succeed or fail during development. Approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition continues to be attributed to ADMET liabilities, making accurate prediction of these properties essential for improving drug development efficiency [9]. The pharmaceutical industry employs three complementary methodological approaches—in silico, in vitro, and in vivo—each with distinct advantages, limitations, and applications within the drug development pipeline. These approaches form an interconnected toolkit that enables researchers to evaluate how compounds behave within biological systems, from initial screening through preclinical development.

Over decades, ADMET properties have become one of the most important issues for assessing the effects or risks of small molecular compounds on the human body [10]. The growing need to minimize animal use in medical development and research further highlights the increasing significance of in silico and in vitro tools [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three methodological landscapes, focusing on their respective roles, experimental protocols, and how their integration—particularly the validation of in silico predictions with in vitro data—strengthens the drug discovery process.

Core Methodologies: Definitions and Characteristics

Comparative Analysis of ADMET Approaches

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo ADMET evaluation methods

| Feature | In Silico | In Vitro | In Vivo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Computational simulation of ADMET properties | Experiments conducted in controlled laboratory environments using biological components outside living organisms | Studies performed within living organisms |

| Throughput | Very high (can screen thousands of compounds rapidly) | Moderate to high (depends on assay format) | Low (time-intensive and resource-heavy) |

| Cost Factors | Very low once models are established | Moderate (reagents, equipment, labor) | Very high (animal costs, facilities, personnel) |

| Time Requirements | Minutes to hours for predictions | Days to weeks depending on assay complexity | Weeks to months for complete studies |

| Data Output | Predictive parameters and calculated properties | Quantitative measurements of specific processes | Integrated physiological responses |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Supporting role for decision-making | Accepted for specific endpoints (e.g., Caco-2 for permeability) | Gold standard for preclinical safety |

| Key Advantages | No physical samples required; high speed and low cost [1] | Controlled environment; mechanistic insights | Complete physiological context |

| Primary Limitations | Model dependency and applicability domain constraints [10] | Simplified biological representation | Species translation challenges; ethical considerations |

Methodology-Specific Applications

In silico approaches eliminate the need for physical samples and laboratory facilities while providing rapid and cost-effective alternatives to expensive and time-consuming experimental testing [1]. These computational methods include quantum mechanics calculations, molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, QSAR analysis, molecular dynamics simulations, and PBPK modeling [1]. The fusion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) with computational chemistry has further revolutionized drug discovery by enhancing compound optimization, predictive analytics, and molecular modeling [11].

In vitro models include systems such as Caco-2 cell monolayers for intestinal permeability assessment, which have emerged as the "gold standard" for drug permeability due to their ability to closely mimic the human intestinal epithelium [12]. These assays provide a balance between biological relevance and experimental control, though they may not fully capture the complexity of whole organisms.

In vivo studies remain essential for understanding complete pharmacokinetic profiles and toxicity outcomes in intact physiological systems. However, there is growing pressure to reduce animal testing through the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement), driving increased adoption of in silico and in vitro alternatives [1].

Experimental Validation: Integrating In Silico Predictions with In Vitro Data

Validation Workflow and Relationship

The convergence of in silico predictions with experimental validation represents a cornerstone of modern ADMET evaluation. The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for validating computational predictions with biological assays:

Diagram 1: Integrated ADMET validation workflow showing the feedback loop between methodologies

This validation framework creates a virtuous cycle where computational models identify promising candidates for experimental testing, and experimental results subsequently refine and improve the computational models. The feedback loop is essential for enhancing model accuracy and expanding applicability domains over time.

Case Study: Caco-2 Permeability Prediction

The Caco-2 cell model has been widely used to assess intestinal permeability of drug candidates in vitro, owing to its morphological and functional similarity to human enterocytes [12]. This validation case study exemplifies the rigorous comparison between computational predictions and experimental measurements.

Table 2: Performance comparison of machine learning models for Caco-2 permeability prediction

| Model Type | Dataset Size | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 5,654 compounds | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit2D descriptors | Best overall performance on test sets | [12] |

| Random Forest | 5,654 compounds | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit2D descriptors | Competitive performance | [12] |

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | 5,654 compounds | Molecular graph representation | Captured nuanced molecular features | [12] |

| Boosting Model | 1,272 compounds | MOE 2D/3D descriptors | R² = 0.81, RMSE = 0.31 | [12] |

| MESN Deep Learning | 4,464 compounds | Multiple molecular embeddings | MAE = 0.410, RMSE = 0.545 | [12] |

| Consensus Random Forest | 4,900+ molecules | QSPR approach with feature selection | RMSE = 0.43-0.51, R² = 0.57-0.61 | [12] |

Experimental Protocol for Caco-2 Validation:

- Data Curation: Compile experimental Caco-2 permeability measurements from public sources and in-house datasets

- Molecular Standardization: Apply standardized procedures for tautomer canonicalization and neutral forms preservation

- Representation Generation: Calculate multiple molecular representations including Morgan fingerprints, RDKit 2D descriptors, and molecular graphs

- Model Training: Implement various machine learning algorithms with scaffold-based data splitting to ensure structural diversity

- Validation: Assess model performance using hold-out test sets and external validation compounds from industrial collections

- Application Domain Analysis: Evaluate model robustness and define boundaries for reliable predictions [12]

This systematic validation approach demonstrates that machine learning models, particularly XGBoost, can achieve significant predictive accuracy for Caco-2 permeability, enabling their use as reliable tools for assessing intestinal absorption during early-stage drug discovery [12].

Advanced Approaches and Recent Innovations

Federated Learning for Expanded Chemical Space Coverage

A fundamental challenge in ADMET prediction is that model performance typically degrades when predictions are made for novel scaffolds or compounds outside the distribution of training data [9]. Federated learning addresses this limitation by enabling model training across distributed proprietary datasets without centralizing sensitive data, thus expanding the chemical space coverage.

Cross-pharma research has demonstrated that federated models systematically outperform local baselines, and performance improvements scale with the number and diversity of participants [9]. This approach alters the geometry of chemical space a model can learn from, improving coverage and reducing discontinuities in the learned representation. The benefits persist across heterogeneous data, as all contributors receive superior models even when assay protocols, compound libraries, or endpoint coverage differ substantially [9].

Quantitative In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation (QIVIVE)

Quantitative in vitro to in vivo extrapolation has emerged as a crucial methodology for converting concentrations that produce adverse outcomes in vitro to corresponding in vivo doses using physiologically based kinetic modeling-based reverse dosimetry [13]. A significant challenge in applying QIVIVE arises from the common use of "nominal" chemical concentrations reported for in vitro assays that are not directly comparable to "free" chemical concentrations in plasma observed in vivo [13].

Recent comparative analyses of chemical distribution models have evaluated the performance of different in vitro mass balance models for predicting free media or cellular concentrations [13]. These studies found that predictions of media concentrations were more accurate than those for cells, and that the Armitage model had slightly better performance overall [13]. Through sensitivity analyses, researchers determined that chemical property-related parameters were most influential for media predictions, while cell-related parameters were also important for cellular predictions.

AI and Machine Learning Advancements

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) with traditional computational methods has transformed ADMET prediction landscapes. Core AI algorithms including support vector machines, random forests, graph neural networks, and transformers are now extensively applied in molecular representation, virtual screening, and ADMET property prediction [11]. Platforms like Deep-PK and DeepTox leverage graph-based descriptors and multitask learning for pharmacokinetics and toxicity prediction [11].

In structure-based design, AI-enhanced scoring functions and binding affinity models outperform classical approaches, while deep learning transforms molecular dynamics by approximating force fields and capturing conformational dynamics [11]. The convergence of AI with quantum chemistry and density functional theory is illustrated through surrogate modeling and reaction mechanism prediction, though challenges remain in data quality, model interpretability, and generalizability [11].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Evaluation

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for ADMET assessment

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Caco-2, MDCK, LLC-PK1 cell lines | Model intestinal, renal, and blood-brain barrier permeability | In vitro permeability assessment [12] |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Quantum mechanics (QM), Molecular mechanics (MM) | Predict reactivity, stability, and metabolic routes | In silico ADMET profiling [1] |

| Molecular Representations | Morgan fingerprints, RDKit 2D descriptors, molecular graphs | Encode structural features for machine learning | Model training and prediction [12] [14] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | XGBoost, Random Forest, MPNN, SVM | Build predictive models from structural data | In silico property prediction [12] [14] |

| Metabolic Enzyme Systems | CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 | Assess compound metabolism and potential interactions | In vitro and in silico metabolism studies [1] |

| Physiologically-Based Kinetic Models | PBK modeling with reverse dosimetry | Convert in vitro concentrations to in vivo doses | QIVIVE implementation [13] |

| In Vitro Mass Balance Models | Armitage, Fischer, Fisher models | Predict free concentrations in assay media | In vitro assay interpretation [13] |

The integration of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methodologies represents the most promising path forward for comprehensive ADMET evaluation in drug discovery. While each approach has distinct strengths and limitations, their synergistic application creates a powerful framework for predicting compound behavior and mitigating late-stage attrition. The continuous refinement of computational models through experimental validation, as demonstrated in the Caco-2 permeability case study, enables increasingly accurate predictions that can guide compound selection and optimization during early discovery phases.

Recent advances in federated learning, AI-powered predictive modeling, and quantitative in vitro to in vivo extrapolation are addressing fundamental challenges in chemical space coverage, data diversity, and physiological relevance. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate, the drug discovery community moves closer to developing truly generalizable ADMET models with expanded predictive power across the chemical and biological diversity encountered in modern pharmaceutical research. This progression ultimately supports the development of safer, more effective therapeutics while potentially reducing costs and animal testing in the drug development pipeline.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The ADMET Failure Landscape

- Quantifying the Impact: ADMET Attrition in the Drug Development Pipeline

- Benchmarking Predictive Models: Performance on Key ADMET Properties

- A Guide to Experimental Protocols for ADMET Validation

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Resources

- Integrated Workflows: Bridging In Silico and In Vitro Data

- Future Perspectives in ADMET Prediction

Drug discovery and development is a high-stakes endeavor, plagued by considerable doubt and a high likelihood of failure. A leading cause of this failure is undesirable Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties [15] [16]. Understanding the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of candidate drugs is crucial for their success, requiring early assessment of these properties in the discovery process [15]. Poor ADMET profiles are a major cause of attrition in drug development, accounting for approximately 40% of compound failures during the testing phase [17]. This translates to a massive financial burden, with the average cost of developing a single new drug estimated to easily exceed $2 billion [15]. The high attrition rate underscores the critical need for robust tools to predict and validate ADMET properties early, weeding out problematic compounds before they enter the costly clinical development phase [16].

Quantifying the Impact: ADMET Attrition in the Drug Development Pipeline

The following table summarizes the key ADMET parameters and their role in drug failure, highlighting why they are critical to assess early.

Table 1: Key ADMET Properties and Their Impact on Drug Failure

| ADMET Property | Description | Consequence of Poor Performance | Common Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Transportation of the unmetabolized drug from the administration site to circulation [18]. | Low oral bioavailability, inadequate therapeutic effect [18]. | Caco-2 cell permeability, Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) models [19] [18]. |

| Distribution | Reversible transfer of a drug through the body's blood and tissues [18]. | Failure to reach the target site of action (e.g., brain), or distribution to sensitive tissues causing toxicity [18]. | Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration, Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) [18]. |

| Metabolism | Biotransformation of the drug in the body [18]. | Too rapid metabolism leads to short duration of action; too slow metabolism leads to accumulation and toxicity [20]. | Cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibition/induction, Human Liver Microsomal (HLM) stability [20] [18]. |

| Excretion | The removal of the administered drug from the body [18]. | Accumulation of the drug, leading to potential toxicity [18]. | Clearance (Cl), Half-life (t1/2) [18]. |

| Toxicity | The level of damage a compound can inflict on an organism [18]. | Adverse effects in patients, drug withdrawal from the market, trial failure [16]. | hERG inhibition (cardiac toxicity), Ames test (mutagenicity), carcinogenicity [18]. |

Benchmarking Predictive Models: Performance on Key ADMET Properties

The field of in silico ADMET prediction has evolved significantly, with various machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models now offering rapid, cost-effective screening. The table below compares the performance of different modeling approaches on benchmark ADMET tasks, using standard evaluation metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of In Silico ADMET Prediction Models

| Prediction Task | Model Type | Dataset | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | XGBoost (on Morgan Fingerprints + RDKit 2D Descriptors) | 5,654 compounds | Best-performing model on test sets vs. RF, GBM, SVM, DMPNN, and CombinedNet. | [19] |

| Caco-2 Permeability | Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | 4,464 compounds | MAE = 0.410, RMSE = 0.545 | [19] |

| CYP450 Inhibition | Attention-based Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Six benchmark datasets | Competitive performance on CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 classification tasks. | [15] |

| Aqueous Solubility (log S) | Attention-based Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Six benchmark datasets | Effective performance on regression task, bypassing molecular descriptors. | [15] |

| Lipophilicity (log P) | Attention-based Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Six benchmark datasets | Effective performance on regression task, bypassing molecular descriptors. | [15] |

| Multi-task ADME-T | Transformer-based Model | Pre-trained on 1.8B molecules from ZINC/PubChem | High accuracy in predicting a wide array of properties (e.g., solubility, BBB penetration, toxicity). | [17] |

Evaluation Metrics Explained:

- Classification Models: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score (range 0-1, higher is better), and ROC-AUC (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) are used to evaluate models that categorize compounds (e.g., CYP inhibitor vs. non-inhibitor) [20].

- Regression Models: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) (lower is better), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) (higher is better, up to 1) are used for models predicting continuous values (e.g., solubility, permeability values) [19] [20].

A Guide to Experimental Protocols for ADMET Validation

For a computational prediction to be trusted, it must be validated with experimental data. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays cited in the literature.

Caco-2 Permeability Assay for Predicting Intestinal Absorption

The Caco-2 cell model is the "gold standard" for assessing intestinal permeability in vitro due to its morphological and functional similarity to human enterocytes [19].

Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Culture Caco-2 cells in standard media (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin) [19].

- Seeding and Differentiation: Seed cells on permeable filter supports in transwell plates. Allow cells to differentiate and form tight junctions over 21 days [19].

- Transepithelial Transport: On the day of the experiment, add the test compound to the donor compartment (apical side for absorption study). The receiver compartment (basolateral side) contains fresh buffer [19].

- Sampling and Analysis: Incubate for a set time (e.g., 2 hours). Sample from the receiver compartment and analyze compound concentration using a sensitive method like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [19].

- Data Calculation: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A × C0), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C0 is the initial donor concentration [19]. Results are often reported as log Papp (cm/s).

Molecular Docking for Binding Affinity and Metabolism Studies

Molecular docking is a computational method used to predict the orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) within a protein's active site, useful for understanding interactions with metabolic enzymes like CYP450s [21].

Protocol:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from Protein Data Bank, PDB). Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using software like MOE or Schrödinger Suite [21].

- Ligand Preparation: Draw or obtain the 3D structure of the test molecule. Energy-minimize the structure and generate potential 3D conformations [21].

- Docking Simulation: Define the active site (often based on the location of a co-crystallized native ligand). Run the docking algorithm to generate multiple binding poses. The software scores each pose based on an energy function [21].

- Validation and Analysis: Validate the docking procedure by re-docking the native ligand and calculating the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted and original pose; an RMSD < 2.0 Å is acceptable. Analyze the binding mode (poses) and interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) of the test compound [21].

MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

The MTT assay is a colorimetric method for assessing cell metabolic activity, used as a proxy for cell viability and compound toxicity [21].

Protocol:

- Cell Seeding: Seed adherent cells (e.g., human gingival fibroblasts) in a 96-well plate and allow them to attach overnight [21].

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with a range of concentrations of the test compound. Include negative control (vehicle only) and positive control (a known toxic compound) wells [21].

- MTT Incubation: After a designated exposure time (e.g., 24-72 hours), add MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to each well and incubate for 2-4 hours. Living cells reduce the yellow MTT to purple formazan crystals [21].

- Solubilization and Measurement: Remove the media and dissolve the formazan crystals in a solvent like DMSO. Measure the absorbance of the solution at 570 nm using a microplate reader [21].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cell viability compared to the negative control. The concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50% (IC50) is determined from the dose-response curve [21].

Successful ADMET validation relies on a suite of computational and experimental resources. The following table details key tools for modern drug discovery research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Validation

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use in ADMET Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates into enterocyte-like cells, forming a polarized monolayer. | The primary in vitro model for predicting human intestinal absorption and permeability [19]. |

| Transwell Plates | Multi-well plates with permeable membrane inserts that allow for compartmentalized cell culture. | Used in Caco-2 assays to separate apical and basolateral compartments for permeability measurement [19]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used to compute molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit 2D descriptors) and generate molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) for machine learning models [19]. |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Commercial software suite for molecular modeling and drug discovery. | Used for molecular docking studies to predict binding interactions with targets like metabolic enzymes or viral proteins [21]. |

| PharmaBench | A comprehensive, open-source benchmark set for ADMET properties with over 52,000 entries. | Serves as a high-quality, diverse dataset for training and validating in silico ADMET prediction models [22]. |

| SwissADME / pkCSM | Free web servers for predicting pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties. | Provide accessible in silico predictions for parameters like log P, solubility, and CYP inhibition during early-stage screening [18]. |

Integrated Workflows: Bridging In Silico and In Vitro Data

The most effective strategy to mitigate ADMET-related failure is an integrated workflow that iteratively cycles between computational prediction and experimental validation. This approach ensures that only the most promising compounds advance, saving time and resources. The following diagram illustrates this iterative validation cycle.

Future Perspectives in ADMET Prediction

The future of ADMET prediction lies in enhancing the accuracy and integration of models. The use of Generative AI (GenAI) for de novo molecular design is emerging, with a focus on creating "beautiful molecules" that are synthetically feasible and have optimal ADMET profiles from the outset [23]. A key challenge remains the accurate prediction of complex properties like binding affinity and toxicity when exploring novel chemical spaces [23]. Furthermore, the creation of larger, more standardized, and clinically relevant benchmark datasets, such as PharmaBench, is crucial for developing robust models [22]. The ultimate goal is a closed-loop discovery system where AI-generated molecules are rapidly synthesized and tested, with the resulting data continuously refining the predictive models, thereby accelerating the journey to safe and effective therapeutics [23] [17].

Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) represent a significant clinical challenge, potentially leading to serious adverse events, reduced treatment efficacy, and even market withdrawal of pharmaceuticals [24]. For decades, drug development programs faced practical challenges in designing and interpreting DDI studies due to differing regional guidance from major regulatory agencies including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) [25] [26]. The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) initiated the M12 guideline to address these disparities and create a single set of globally harmonized recommendations for designing, conducting, and interpreting metabolic enzyme- or transporter-mediated drug-drug interaction studies [27] [28] [26]. This harmonization aims to streamline global drug development, facilitate patient access to new therapies, and ensure consistent safety standards across regions [25].

The ICH M12 guideline, which reached its final version in 2024 after a draft release in 2022, provides a consolidated framework that supersedes previous regional guidances [27] [28]. This article examines the role of ICH M12 in achieving regulatory harmonization, with particular focus on its implications for validating in silico ADMET predictions against in vitro data—a critical component of modern drug development workflows.

Comparative Analysis of DDI Guidelines: Pre- and Post-ICH M12

Key Regional Differences Before ICH M12

Prior to the adoption of ICH M12, regional regulatory agencies maintained distinct guidelines with variations in experimental protocols, interpretation criteria, and submission requirements. These differences created complexities for sponsors seeking global approval for new therapeutic products [25] [26]. The table below summarizes the major regional guidances that ICH M12 replaces or consolidates.

Table 1: Major Regional DDI Guidances Consolidated by ICH M12

| Regulatory Agency | Previous Guidance Document | Key Characteristics | Status with ICH M12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| US FDA | In Vitro and Clinical DDI Guidance (2020) | Separate documents for in vitro and clinical studies; specific FDA recommendations | Replaced by ICH M12 [25] |

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Guideline on Investigation of Drug Interactions - Revision 1 (2013) | Comprehensive coverage including GI-mediated interactions | Superseded by ICH M12 [28] |

| Japan PMDA | DDI Guidance (2018) | Specific requirements for Japanese submissions | Replaced by harmonized approach [25] |

Substantive Changes in ICH M12

ICH M12 introduces significant changes to DDI evaluation criteria that affect both experimental design and interpretation. These modifications create a unified standard for assessing interaction potential across regulatory jurisdictions. The following table compares key evaluation parameters between previous approaches and the new ICH M12 standards.

Table 2: Comparison of Key DDI Evaluation Parameters Before and After ICH M12

| Evaluation Area | Previous Regional Variations | ICH M12 Harmonized Approach | Impact on DDI Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding | Differing recommendations between FDA and EMA on using unbound fraction [29] | Use of unbound human plasma fraction <0.01 allowed with proper methodology [30] [29] | May decrease predicted interaction risk for highly bound compounds [29] |

| CYP Induction Concentration | FDA used 50× Cmax,u; EMA used lower multiples [30] | Standardized to 50× Cmax,u for induction risk assessment [30] [29] | More consistent induction potential evaluation |

| Time-Dependent Inhibition (TDI) | Primarily dilution assays recommended [29] | Both dilution and non-dilution methods accepted [30] [29] | Increased methodological flexibility |

| Metabolite as Inhibitor | Threshold differences between regions [25] | Consistent threshold: AUCmetab ≥25% of AUCparent and ≥10% of drug-related material [25] [30] | Standardized metabolite DDI assessment |

| Transporter Inhibition Cut-offs | Different R-values between FDA and EMA [30] | Harmonized cut-off values for positive signals [30] | Consistent transporter DDI interpretation |

| UGT Enzyme Evaluation | Minimal guidance in FDA's previous guidance [25] | Detailed recommendations with list of substrates and inhibitors [25] | Enhanced evaluation of glucuronidation interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

In Vitro DDI Evaluation Framework

ICH M12 provides detailed methodological recommendations for in vitro DDI studies that support the validation of in silico ADMET predictions. These protocols establish standardized conditions for assessing enzyme- and transporter-mediated interactions.

Enzyme-Mediated DDI Assessments:

- Reaction Phenotyping: Experiments should identify enzymes contributing ≥25% to drug elimination [24]. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A) must be routinely evaluated using in vitro reaction phenotyping, preferably before Phase 1 trials [24] [30].

- CYP Inhibition Studies: Both direct and time-dependent inhibition should be tested for all major CYP enzymes using pooled human liver microsomes (HLM), pooled hepatocytes, or microsomes from recombinant systems [24]. Determination of Ki or IC50 should use several concentrations of the investigational drug relevant to clinical exposure [24].

- CYP Induction Studies: Testing for CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and CYP3A4 induction is recommended using human hepatocytes from a minimum of three individual donors [24]. The preferred readout (except for CYP2C19) is changes in CYP450 mRNA levels [24].

Transporter-Mediated DDI Assessments:

- Efflux Transporters: In vitro P-gp and BCRP substrate and inhibition data are typically expected in regulatory submissions [24]. Bidirectional transport assays with cell-based systems are recommended, especially for drugs where biliary excretion is a major elimination pathway or when the pharmacological target is in the brain [24].

- Hepatic Uptake Transporters: Evaluation as a substrate for OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 is recommended if hepatic metabolism or biliary excretion accounts for ≥25% of drug elimination or if the pharmacological target is in the liver [24] [30].

- Renal Transporters: Assessment of OAT1, OAT3, OCT2, MATE1, and MATE2-K is recommended if a drug demonstrates renal toxicity or if renal active secretion accounts for ≥25% of systemic clearance [24].

Timing of DDI Evaluations in Drug Development

ICH M12 provides clearer recommendations on when to conduct specific DDI assessments throughout the drug development continuum [25] [24]:

Table 3: Recommended Timing for DDI Assessments in Drug Development

| Development Stage | Required DDI Assessments | Purpose and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Phase 1 | In vitro reaction phenotyping (enzymes) [24] [30] | Identify major metabolic pathways to inform initial clinical trial design and safety monitoring |

| Pre-Phase 1 | In vitro precipitant effects on CYP enzymes and transporters [30] | Understand potential perpetrator effects to guide exclusion criteria for concomitant medications |

| During Clinical Development | In vitro interactions for major/active metabolites [30] | Characterize metabolite DDI potential once human metabolic profile is established |

| Before Phase 3 | Human absorption, metabolism, and excretion (hAME) study results [30] | Comprehensive understanding of elimination pathways to inform final DDI strategy |

| Before Phase 3 | Clinical DDI studies based on integrated in vitro and clinical data [24] | Final confirmation of DDI risk to inform product labeling |

Model-Informed Drug Development Approaches

ICH M12 explicitly recognizes the value of model-based approaches for DDI evaluation [28] [31] [30]. The guideline describes the application of both mechanistic static models (MSM) and physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling in various contexts:

- Mechanistic Static Models: These can be used to extrapolate victim DDI results with CYP or transporter inhibitors to "less potent" inhibitors, allowing for a semi-quantitative approach based on justifications and sensitivity analyses [30].

- PBPK Modeling: Recommended for informing DDI strategy and study design, translating pharmacogenomic effects to object DDIs, evaluating complex DDIs, DDIs in specific populations, replacing studies of staggered dosing, supporting evaluations of drugs with long half-lives, and leveraging endogenous biomarker data [31] [30].

- Endogenous Biomarkers: ICH M12 endorses the use of biomarkers such as plasma coproporphyrin I (for hepatic OATP1B1/3), plasma and urine N-methylnicotinamide and N-methyladenosine (for renal OCT2, MATE1, MATE2K), and plasma 4β-hydroxycholesterol/cholesterol ratio (for CYP3A) [30]. These biomarkers can be leveraged in PBPK models to strengthen DDI predictions [30].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for DDI assessment under ICH M12:

Diagram 1: Integrated DDI Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementation of ICH M12-compliant DDI assessments requires specific research reagents and experimental systems. The following table details essential materials for conducting these evaluations.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ICH M12-Compliant DDI Assessments

| Reagent/System | Function in DDI Assessment | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Evaluation of metabolic stability and enzyme inhibition potential [24] | CYP reaction phenotyping; reversible inhibition assays |

| Transfected Cell Lines | Transporter substrate and inhibition assays [24] | P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OATs, OCTs, MATEs evaluation |

| Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes | Assessment of enzyme induction potential and metabolic clearance [24] | CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP3A4 induction assays; metabolite identification |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Reaction phenotyping to identify specific enzymes involved in metabolism [24] | Determination of enzyme-specific contribution to total metabolism |

| Specific Probe Substrates | Evaluation of enzyme and transporter inhibition potential [24] [30] | Quantitative assessment of inhibitory potency (IC50, Ki) |

| Validated Chemical Inhibitors | Selective inhibition of specific enzymes or transporters in phenotyping studies [24] | Identification of contribution of specific pathways to total clearance |

Implications for In Silico ADMET Prediction Validation

The harmonization achieved through ICH M12 has significant implications for validating in silico ADMET predictions, creating more standardized datasets for model training and verification.

Standardized Data for Model Development

The consistent experimental protocols and interpretation criteria established by ICH M12 generate standardized datasets that enhance the reliability of in silico ADMET models in several key areas:

- Protein Binding Considerations: ICH M12's guidance on using experimentally measured fraction unbound for drugs with >99% protein binding enables more accurate prediction of unbound drug concentrations, a critical parameter for DDI risk assessment [31] [30] [29].

- Transporter DDI Prediction: Harmonized cut-off values for transporter inhibition create consistent thresholds for validating in silico predictions of transporter-mediated DDIs [30].

- Metabolite DDI Assessment: Standardized criteria for when to evaluate metabolites as substrates, inhibitors, or inducers provide clear decision trees for in silico model development [25] [30].

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflows

ICH M12's recognition of model-informed drug development approaches supports the integration of in silico predictions with experimental data throughout the drug development process. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow for enzyme-mediated DDI assessment:

Diagram 2: Computational-Experimental DDI Workflow

The ICH M12 guideline represents a significant achievement in global regulatory harmonization, establishing consistent standards for DDI assessment that transcend previous regional differences. By providing unified recommendations for experimental design, methodology, and data interpretation, ICH M12 enables more efficient global drug development while maintaining rigorous safety standards.

For researchers focused on validating in silico ADMET predictions, ICH M12 creates a foundation of standardized experimental data that enhances model training and verification. The explicit recognition of model-informed drug development approaches within the guideline facilitates the integration of computational predictions with experimental verification throughout the drug development process.

As the pharmaceutical industry transitions to ICH M12 standards, the harmonized framework will likely accelerate the adoption and refinement of in silico ADMET prediction methods, ultimately contributing to more efficient drug development and improved patient safety through better prediction and management of drug interactions.

In silico models, particularly for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) of drug candidates, have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery, offering a scalable and efficient alternative to resource-intensive traditional methods [32] [33]. These computer-based simulations allow for the high-throughput screening of compounds, significantly accelerating the lead optimization phase [33] [34]. The ultimate goal is to mitigate the high attrition rates in clinical development, where poor pharmacokinetics and unforeseen toxicity remain major causes of failure [33]. However, the reliability of these in silico predictions hinges on their validation against experimental data, with in vitro assays serving as a crucial benchmark for establishing real-world biological relevance before proceeding to complex and costly in vivo studies [35] [36]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various in silico approaches against in vitro data, examining the key challenges of data quality and model generalization that define the current landscape.

Performance Comparison: In Silico Predictions vs. In Vitro Data

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data and core challenges when comparing in silico model predictions with experimental in vitro results.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of In Silico Models Against In Vitro Data

| ADMET Property | Typical In Vitro Assay | High-Performing In Silico Models | Reported Performance (AUC/R²/Accuracy) | Key Limitations vs. In Vitro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption (Permeability) | Caco-2 cell assay [33] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Ensemble Methods [33] | R²: ~0.67-0.68 (on analogous endpoints) [37] | Struggles with active transport mechanisms (e.g., P-gp) not fully captured by structure [33] |

| Metabolism (CYP Inhibition) | Human liver microsomes, recombinant enzymes [33] | Multitask Deep Learning, XGBoost [33] | High AUC values reported for major CYP isoforms [33] | Predicts potential, not actual metabolic rate; misses novel metabolites [33] |

| Toxicity (hERG) | hERG potassium channel assay [33] | Machine Learning on molecular descriptors [32] [33] | Accuracy often >70% in research settings [32] | High false-negative risk for structurally novel scaffolds; lacks organ-level context [33] |

| Blastocyst Formation (IVF) | Embryo morphology assessment [38] | LightGBM, XGBoost, SVM [37] | R²: 0.673–0.676; Accuracy: 0.675–0.71 [37] | Model may underestimate yields in poor-prognosis subgroups [37] |

Table 2: Core Data Quality and Generalization Challenges

| Challenge Category | Impact on In Silico Model Performance | Manifestation in In Vitro Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Availability | Model accuracy is highly dependent on the quality, size, and chemical diversity of the training data [32] [34]. | Predictions are unreliable for chemical spaces not represented in the training set, leading to high error rates when tested with novel compounds in vitro [33]. |

| Algorithmic Limitations & Black-Box Nature | Deep learning models, while powerful, often lack interpretability, making it difficult to understand the rationale behind a prediction [33]. | Difficult for scientists to trust or troubleshoot mismatches between in silico and in vitro results without mechanistic insights [33]. |

| Experimental Variability & Biological Complexity | Inconsistencies in experimental protocols and biological noise in the in vitro data used for training confound model learning [38]. | Models trained on one lab's in vitro data may not generalize to another lab's data due to differences in assay conditions or cell lines [38]. |

| Contextual Oversimplification | Models predict based on molecular structure alone, missing the integrated physiology of a living system [35] [36]. | A compound predicted to have high permeability in silico may show poor absorption in vitro due to efflux transporters or metabolism not modeled [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A rigorous and transparent methodology is essential for the meaningful validation of in silico ADMET predictions against in vitro benchmarks. The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for this process.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Compound Selection and Curation: Select a diverse and chemically representative set of drug candidates not used in the model's training. Curate structures using standardized formats (e.g., SMILES) and ensure purity is verified for in vitro testing [34].

In Silico Prediction Execution: Apply the trained machine learning model (e.g., GNN, LightGBM) to generate predictions for the specific ADMET endpoint (e.g., Caco-2 permeability, hERG inhibition). All predictions and associated confidence scores should be documented before in vitro testing [33] [34].

Parallel In Vitro Assay Performance: Conduct the corresponding gold-standard in vitro assay (e.g., Caco-2 for permeability, hERG patch clamp for toxicity) following strict, standardized operating procedures (SOPs) to minimize experimental variability. Assays should be performed in replicates, and raw data should be recorded with metadata on assay conditions [33] [38].

Data Integration and Statistical Comparison: Integrate the in silico predictions and in vitro results into a unified dataset. Calculate a suite of performance metrics to evaluate the agreement, including:

- Discrimination: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) for classification tasks.

- Accuracy & Error: R-squared (R²) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression tasks [37].

- Calibration: Analysis of how well the predicted probabilities match the observed frequencies in vitro [38].

Discrepancy Analysis and Model Iteration: Systematically investigate compounds where major discrepancies occur between prediction and assay results. This analysis can reveal model blind spots and inform the refinement of the training set or algorithm, leading to model retraining for improved generalizability [33] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation relies on specific, high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for featured ADMET validation workflows.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for ADMET Validation

| Reagent/Tool Name | Function in Workflow | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line used as an in vitro model of the human intestinal mucosa to predict drug absorption [33]. | Measuring apparent permeability (Papp) of drug candidates for comparison with in silico absorption predictions [33]. |

| hERG-Expressing Cell Line | Cell lines (e.g., HEK293) stably expressing the human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene potassium channel. | In vitro patch-clamp or flux assays to assess compound risk for Torsades de Pointes cardiac arrhythmia, validating in silico toxicity alerts [33]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Subcellular fractions containing cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and other drug-metabolizing enzymes. | Incubated with a drug candidate to identify major metabolites and calculate metabolic stability (e.g., half-life), grounding truth for in silico metabolism models [33]. |

| Standardized Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical structures (e.g., ECFP, molecular weight, logP) used as input for ML models. | Enable quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling for ADMET endpoints. Critical for model interoperability and performance [32] [34]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Framework | A class of deep learning algorithms that operate directly on molecular graph structures. | Captures complex structure-property relationships for ADMET endpoints, often leading to higher predictive accuracy compared to traditional descriptors [33]. |

The current landscape of in silico ADMET prediction is defined by a tension between immense promise and persistent challenges. While advanced machine learning models like graph neural networks and ensemble methods increasingly demonstrate robust performance, their utility in de-risking drug development is ultimately constrained by the quality of the underlying data and their ability to generalize beyond their training sets. The critical practice of rigorous, multi-faceted validation against standardized in vitro assays remains the cornerstone for building trust in these in silico tools. Future progress hinges on the generation of higher-quality, more comprehensive experimental data, the development of more interpretable and biologically integrated models, and a continued commitment to transparent and standardized benchmarking. By systematically addressing these challenges of data quality and model generalization, the field can fully realize the potential of in silico methods to accelerate the delivery of safer and more effective therapeutics.

Building and Applying Integrated In Silico and In Vitro Workflows

In modern drug development, the assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical gatekeeper determining candidate success or failure. Historically, poor ADMET profiles have been responsible for approximately 40-60% of clinical trial failures, creating compelling economic and ethical imperatives for earlier, more reliable prediction [39]. The pharmaceutical industry has consequently shifted toward extensive ADMET screening earlier in the discovery process to identify and eliminate problematic compounds before they enter costly development phases [40].

In silico (computational) methods have emerged as powerful tools addressing this challenge, offering rapid, cost-effective alternatives to expensive and time-consuming experimental testing. These approaches eliminate the need for physical samples and laboratory facilities while providing critical insights into compound behavior [40]. This guide examines the evolving landscape of in silico ADMET tools, from established Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) methods to advanced machine learning (ML) algorithms and sophisticated Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling platforms, with particular emphasis on validation against experimental data.

Fundamental Methods: QSAR and Molecular Modeling

QSAR Foundations and Applications

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents the foundational approach for predicting chemical properties from molecular structure. QSAR models correlate structural descriptors of compounds with their biological activities or physicochemical properties through statistical methods, enabling property prediction for novel compounds based on their structural features [39].

The predictive performance of QSAR models is highly dependent on the quality and diversity of their training data and the relevance of selected molecular descriptors. Recent benchmarking studies of twelve QSAR software tools demonstrated adequate predictive performance for many physicochemical properties (average R² = 0.717), with slightly lower performance for toxicokinetic properties (average R² = 0.639 for regression models) [39]. These tools have become increasingly sophisticated, with applications ranging from predicting basic physicochemical properties like solubility and lipophilicity to complex metabolic stability and transporter affinity.

Molecular Modeling Techniques

Beyond traditional QSAR, more computationally intensive molecular modeling methods provide atomic-level insights into ADMET processes:

Quantum Mechanics (QM) and Molecular Mechanics (MM): QM calculations explore electronic structure properties that influence chemical reactivity and metabolic transformations, particularly valuable for understanding cytochrome P450 metabolism mechanisms [40]. The hybrid QM/MM approach combines accuracy of QM for reaction centers with efficiency of MM for protein environments.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD tracks atom movements over time, revealing binding/unbinding processes, conformational changes, and passive membrane permeability that directly influence absorption and distribution properties [11].

Molecular Docking: This technique predicts how small molecules bind to protein targets like metabolic enzymes or transporters, providing insights into substrate specificity and inhibition potential [41].

Table 1: Molecular Modeling Methods for ADMET Prediction

| Method | Key Applications in ADMET | Computational Cost | Key Insights Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | High-throughput property prediction | Low | Structure-property relationships across compound libraries |

| Molecular Docking | Metabolic enzyme binding, transporter interactions | Medium | Binding modes, affinity estimates, molecular interactions |

| MD Simulations | Membrane permeability, conformational changes | High | Time-dependent behavior, free energy calculations |

| QM/MM | Metabolic reaction pathways, reactivity | Very High | Electronic structure effects, reaction mechanisms |

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Algorithmic Advances in ADMET Prediction

Machine learning (ML) has dramatically expanded capabilities for ADMET prediction, moving beyond traditional QSAR's linear assumptions to capture complex, nonlinear relationships in chemical data. Commonly employed algorithms include Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost, and Gradient Boosted Machines (GBM), each with strengths for different prediction tasks [42] [19].

More recently, deep learning (DL) approaches using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Message-Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance by directly learning from molecular graph representations rather than pre-defined descriptors [42] [19]. For example, Directed-MPNN (D-MPNN) has shown particular promise in molecular property prediction by operating on the graph structure of molecules and passing messages through edge-dependent neural networks [42].

Case Study: Caco-2 Permeability Prediction

Caco-2 cell monolayer permeability represents a critical parameter for predicting intestinal absorption of oral drugs. Traditional experimental assessment requires 7-21 days for cell differentiation, creating bottlenecks in early discovery [19]. Machine learning models address this limitation through quantitative prediction from chemical structure alone.

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated multiple ML algorithms using a large dataset of 5,654 curated Caco-2 permeability measurements [19]. The research compared four machine learning methods (XGBoost, RF, GBM, SVM) and two deep learning approaches (D-MPNN and CombinedNet) using diverse molecular representations including Morgan fingerprints, RDKit 2D descriptors, and molecular graphs. The study found that XGBoost generally provided superior predictions, with model performance robust across different dataset splits [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms for Caco-2 Permeability Prediction

| Algorithm | Molecular Representation | R² | RMSE | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit 2D | 0.81 | 0.31 | Best overall performance, handling of non-linear relationships |

| Random Forest | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit 2D | 0.78 | 0.33 | Robust to outliers, feature importance analysis |

| GBM | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit 2D | 0.79 | 0.32 | Good balance of performance and training speed |

| D-MPNN | Molecular graphs | 0.76 | 0.35 | Automatic feature learning, no descriptor engineering required |

| SVM | Morgan fingerprints + RDKit 2D | 0.72 | 0.38 | Effective in high-dimensional spaces |

The transferability of models trained on public data to industrial settings was also investigated using an internal pharmaceutical company dataset. Results demonstrated that boosting models retained reasonable predictive performance when applied to industry compounds, though some performance degradation highlighted the importance of domain applicability [19].

PBPK Modeling: Integrating Physiology and Mechanism

Principles and Applications of PBPK Modeling

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling represents a mechanistic approach that simulates drug disposition by incorporating physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows), drug-specific properties (lipophilicity, permeability, binding), and system-specific characteristics (enzyme/transporter abundances) [43] [44]. Unlike purely empirical models, PBPK models maintain direct physiological relevance, enabling prediction of drug concentrations in specific tissues and extrapolation to special populations [43].

PBPK modeling has proven particularly valuable in scenarios where clinical data are limited or difficult to obtain due to ethical constraints, such as in pediatric or geriatric populations, pregnant women, and patients with organ impairments [44]. These models can also predict variations in drug metabolism resulting from genetic polymorphisms (e.g., in CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19), age-related physiological changes, and disease states [44].

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite their power, traditional PBPK models face several significant challenges:

Parameter Uncertainty: PBPK models depend on numerous physiological and drug-specific parameters, many of which have substantial uncertainty or inter-individual variability [43]. For example, values for lymph flow rates used in antibody PBPK models vary by two orders of magnitude across different publications [43].

Model Complexity: Comprehensive PBPK models can become extraordinarily complex. A full PBPK model for a therapeutic antibody may require knowledge of over a dozen parameters per tissue compartment, with extrapolation to multiple organs dramatically increasing the parameter estimation challenge [43].

Limited Data Availability: Local drug concentrations in different cells and tissues are rarely available for model verification, creating validation challenges [43].

Extension to Novel Formulations: Adapting PBPK models for new drug delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles) requires accounting for entirely new processes like uptake by the mononuclear phagocytic system, with additional parameters that are often poorly characterized [43].

Hybrid Approaches: Integrating Machine Learning with PBPK Modeling

The ML-PBPK Framework

Recent advances have focused on integrating machine learning with PBPK modeling to overcome traditional limitations. This hybrid approach uses ML to predict critical drug-specific parameters directly from chemical structure, which are then incorporated into mechanistic PBPK frameworks [45] [42].

A landmark study developed an ML-PBPK platform that predicts human pharmacokinetics from compound structures without requiring experimental data [42]. The approach used machine learning models to predict three key parameters: plasma protein fraction unbound (fup), Caco-2 cell permeability, and total plasma clearance (CLt). These ML-predicted parameters were then used as inputs for a whole-body PBPK model encompassing 14 tissues [42].

The results demonstrated that the ML-PBPK model predicted the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) with 65.0% accuracy within a 2-fold range, significantly outperforming PBPK models using traditional in vitro inputs (47.5% accuracy within 2-fold) [42]. This represents a substantial improvement in predictive performance while simultaneously reducing experimental requirements.

Diagram 1: ML-PBPK Integrated Modeling Workflow

Case Study: AI-PBPK for Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitors

A specialized AI-PBPK model was developed to predict pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of aldosterone synthase inhibitors (ASIs) during early discovery stages [45]. The model integrated machine learning with classical PBPK modeling to enable PK simulation of ASIs directly from their structural formulas.

The workflow involved:

- Inputting the compound's structural formula into the AI model to generate key ADME parameters and physicochemical properties

- Using these parameters in the PBPK model to predict pharmacokinetic profiles

- Developing a PD model to predict inhibition rates of aldosterone synthase and 11β-hydroxylase based on plasma free drug concentrations [45]

This approach successfully predicted PK/PD properties for multiple ASI compounds from their structural formulas alone, providing valuable reference for early lead compound screening and optimization [45]. The model demonstrated that AI-PBPK integration could significantly accelerate candidate selection while reducing resource-intensive experimental screening.

Benchmarking and Validation Frameworks

Software Tool Performance Assessment

Comprehensive benchmarking of computational tools is essential for assessing their real-world predictive performance. A recent evaluation of twelve QSAR software tools across 41 validation datasets for 17 physicochemical and toxicokinetic properties provided valuable insights into the current state of computational ADMET prediction [39].

Key findings included:

- Models for physicochemical properties generally outperformed those for toxicokinetic properties

- Several tools exhibited good predictivity across different properties and were identified as recurring optimal choices

- The importance of applicability domain assessment for identifying reliable predictions

- Significant performance variation across different chemical classes and property types

Table 3: Performance Summary of Selected ADMET Prediction Tools

| Software Tool | Key Features | Supported Properties | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPERA | Open-source QSAR models, applicability domain assessment | PC properties, environmental fate, toxicity | Good predictivity for logP, water solubility |

| SwissADME | Web-based, user-friendly interface | Physicochemical properties, drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics | Free tool with comprehensive ADME profiling |

| ADMETlab 3.0 | Platform with multiple prediction modules | Comprehensive ADMET endpoints | High efficiency for large-scale screening |

| B2O Simulator | AI-PBPK integrated platform | PK/PD prediction from structure | Specialized for pharmacokinetic simulation |

Emerging Benchmark Datasets

The development of robust benchmark datasets like PharmaBench addresses critical limitations in previous ADMET datasets, which were often too small or unrepresentative of drug discovery compounds [22]. PharmaBench comprises eleven ADMET datasets with 52,482 entries, significantly larger and more diverse than previous resources.

This benchmark was constructed using a novel multi-agent data mining system based on Large Language Models (LLMs) that effectively identifies experimental conditions within 14,401 bioassays, enabling proper merging of entries from different sources [22]. Such comprehensive, well-curated benchmarks are essential for rigorous tool validation and development of next-generation predictive models.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for ADMET Prediction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro system | Intestinal permeability assessment | Gold standard for absorption prediction; training data for ML models |