Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Validating Computational ADMET Models with Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating computational ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) models.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Validating Computational ADMET Models with Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating computational ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) models. As machine learning and AI revolutionize predictive toxicology and pharmacokinetics, establishing robust validation frameworks is essential for regulatory acceptance and reducing clinical-stage attrition. We explore the foundational importance of high-quality experimental data, detail state-of-the-art methodological approaches including graph neural networks and multi-task learning, address common challenges like data variability and model interpretability, and present best practices for rigorous, comparative model evaluation. The content synthesizes recent advances to empower scientists in building trust and utility in computational ADMET predictions.

The Critical Role of Validation in Computational ADMET

Why ADMET Validation is a Bottleneck in Modern Drug Discovery

Accurate prediction of a drug candidate's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is a fundamental cornerstone of modern drug discovery. Despite decades of scientific advancement, ADMET validation remains a critical bottleneck, responsible for approximately 40–45% of clinical-stage attrition due to unforeseen pharmacokinetic and safety issues [1] [2]. This bottleneck persists because traditional experimental methods are resource-intensive and slow, while modern computational models, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven approaches, face significant hurdles in achieving robust validation against reliable experimental data [3]. The transition towards AI-powered prediction offers great promise, but its ultimate success hinges on the ability to effectively bridge the gap between in-silico forecasts and experimental reality, a process fraught with challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, and biological complexity [4] [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ADMET Validation Issues

This section addresses specific, high-frequency problems researchers encounter when validating computational ADMET models with experimental assays.

FAQ 1: My AI model performs well on test sets but fails in experimental validation. Why?

Answer: This is often due to a domain shift problem, where the chemical space of your experimental compounds differs significantly from the data used to train the model.

- Root Cause: AI models trained on public datasets like ChEMBL or Tox21 may not generalize well to novel, proprietary chemical scaffolds with different structural features or physicochemical properties [1] [3]. The model has learned patterns specific to its training data and fails when those patterns are absent.

- Solution:

- Perform Applicability Domain Analysis: Before experimentation, assess whether your new compounds fall within the chemical space your model was trained on. Use tools like PCA or t-SNE to visualize your new compounds against the training set.

- Utilize Federated Learning: To inherently broaden the model's applicability, use or develop models via federated learning. This technique allows training on diverse, distributed datasets from multiple pharmaceutical companies without sharing raw data, significantly expanding the learned chemical space and improving performance on novel scaffolds [1].

- Implement Continuous Learning: Establish a feedback loop where experimental results are used to continuously fine-tune and update the model, allowing it to adapt to new chemical spaces over time [5].

FAQ 2: My in vitro and in vivo toxicity results are inconsistent. How should I proceed?

Answer: Disconnects between cell-based assays and animal models are common and often stem from physiological complexity not captured in simple systems.

- Root Cause: Conventional 2D cell cultures lack the tissue-specific architecture, cell-cell interactions, and metabolic functions of a whole organism. This can lead to false negatives (missing toxicity) or false positives [6] [3].

- Solution:

- Adopt More Physiologically Relevant Models: Bridge the gap by using advanced in vitro models such as 3D cell cultures, organoids, or organs-on-a-chip. These systems better mimic the in vivo environment and provide more translatable data for model validation [6] [2]. For example, human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatic organoids are now used for more accurate hepatotoxicity evaluation [3].

- Incorporate Mechanistic Data: Move beyond simple viability readouts. Use High Content Screening (HCS) that employs automated microscopy and multiparametric analysis to capture phenotypic changes and specific toxicity pathways (e.g., oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane potential) [6] [5]. This provides richer data for correlating with computational predictions.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the interpretability of my "black-box" AI model for regulatory submissions?

Answer: Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require transparency in the models used to support safety assessments [3].

- Root Cause: Complex AI models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and deep learning architectures make predictions based on patterns that are not easily interpretable by humans, reducing trust and hindering regulatory acceptance.

- Solution:

- Employ Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Integrate methods such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or attention mechanisms into your model workflow. These tools can highlight which molecular substructures or features the model deemed important for its prediction (e.g., identifying a toxicophore) [4] [2] [5].

- Use Model-Specific Interpretation: For models like GNNs, leverage built-in attention layers to visualize which parts of the molecular graph contributed most to the predicted ADMET endpoint [5].

- Provide Rationale-Based Validation: When submitting results, include not just the prediction but also the XAI-derived rationale, linking model outputs to established toxicological knowledge. This builds a compelling case for the model's reliability.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is non-negotiable. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays used to ground-truth computational ADMET predictions.

Protocol for In Vitro Metabolic Stability Assessment

This assay validates predictions of how quickly a compound is metabolized, a key factor determining its half-life in the body.

- Objective: To determine the metabolic stability of a drug candidate using human liver microsomes (HLM) or hepatocytes and calculate intrinsic clearance (CLint).

- Materials:

- Test compound (10 mM stock in DMSO)

- Human liver microsomes (HLM) or cryopreserved human hepatocytes

- NADPH-regenerating system

- Magnesium chloride (MgCl2)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

- Stop solution (Acetonitrile with internal standard)

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- Procedure:

- Incubation Preparation: Prepare incubation mixtures containing 1 mg/mL HLM (or 1 million hepatocytes/mL) and 1 µM test compound in PBS with MgCl2. Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding the NADPH-regenerating system.

- Time-Point Sampling: At time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes), aliquot 50 µL of the incubation mixture and quench with 100 µL of ice-cold stop solution.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge samples, analyze the supernatant via LC-MS/MS to determine the peak area of the parent compound at each time point.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the remaining compound percentage against time. The slope of the linear regression (-k) is used to calculate CLint = (k * Volume of Incubation) / (Microsomal Protein or Cell Count).

Protocol for hERG Inhibition Assay

This protocol validates computational predictions of cardiotoxicity risk associated with the blockade of the hERG potassium channel.

- Objective: To assess the potential of a test compound to inhibit the hERG channel using an in vitro electrophysiology assay.

- Materials:

- Cell line stably expressing the hERG channel (e.g., HEK-293-hERG)

- Patch clamp rig (automated or manual)

- Extracellular and intracellular recording solutions

- Test compound (serial dilutions in DMSO)

- Positive control (e.g., Cisapride, E-4031)

- Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate hERG-expressing cells onto coverslips and incubate until suitable for electrophysiology.

- Baseline Recording: Establish a whole-cell patch clamp configuration. Apply a voltage protocol to elicit hERG tail currents and record a stable baseline.

- Compound Application: Perfuse the cell with increasing concentrations of the test compound (e.g., from 0.1 nM to 30 µM). At each concentration, allow sufficient time for equilibration (e.g., 3-5 minutes) before re-applying the voltage protocol.

- Washout: Perform a washout with compound-free solution to check for reversibility of inhibition.

- Data Analysis: Measure the peak tail current amplitude at each compound concentration. Normalize the current to the baseline level. Fit the normalized data to a Hill equation to calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50).

Data Presentation: Quantitative Benchmarks

Table 1: Key Properties for Common ADMET Assays and their Computational Counterparts. This table helps align experimental design with model validation goals.

| ADMET Property | Common Experimental Assay | Typical AI Model Input | Key Benchmarking Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Stability | Liver microsomal clearance [7] [2] | Molecular structure, physicochemical descriptors [3] | CLint (µL/min/mg) [2] |

| hERG Inhibition | Patch-clamp IC50 [5] [3] | Graph-based molecular representation [2] [5] | IC50 (µM) [5] |

| Hepatotoxicity | DILIrank assessment in hepatocytes [5] | Multitask deep learning on toxicophore data [2] | Binary classification (High/Low Concern) [5] |

| Solubility | Kinetic solubility (pH 7.4) [1] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [1] [2] | LogS value [1] |

| P-gp Substrate | Caco-2 permeability assay [2] | Molecular fingerprints and descriptors [2] [3] | Efflux Ratio |

Table 2: Publicly Available Datasets for ADMET Model Training and Validation. Utilizing these resources is crucial for benchmarking and avoiding data bias.

| Dataset Name | Primary Focus | Scale | Use Case in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tox21 [5] | Nuclear receptor & stress response pathways | 8,249 compounds, 12 assays | Benchmarking for toxicity classification models |

| ToxCast [5] | High-throughput in vitro toxicity | ~4,746 chemicals, 100s of endpoints | Profiling compounds across multiple mechanistic targets |

| hERG Central [5] | Cardiotoxicity (hERG channel inhibition) | >300,000 experimental records | Training and testing for both classification & regression tasks |

| DILIrank [5] | Drug-Induced Liver Injury | 475 annotated compounds | Validating hepatotoxicity predictions for clinical relevance |

| ChEMBL [4] [5] | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Millions of bioactivity data points | General model pre-training and feature learning |

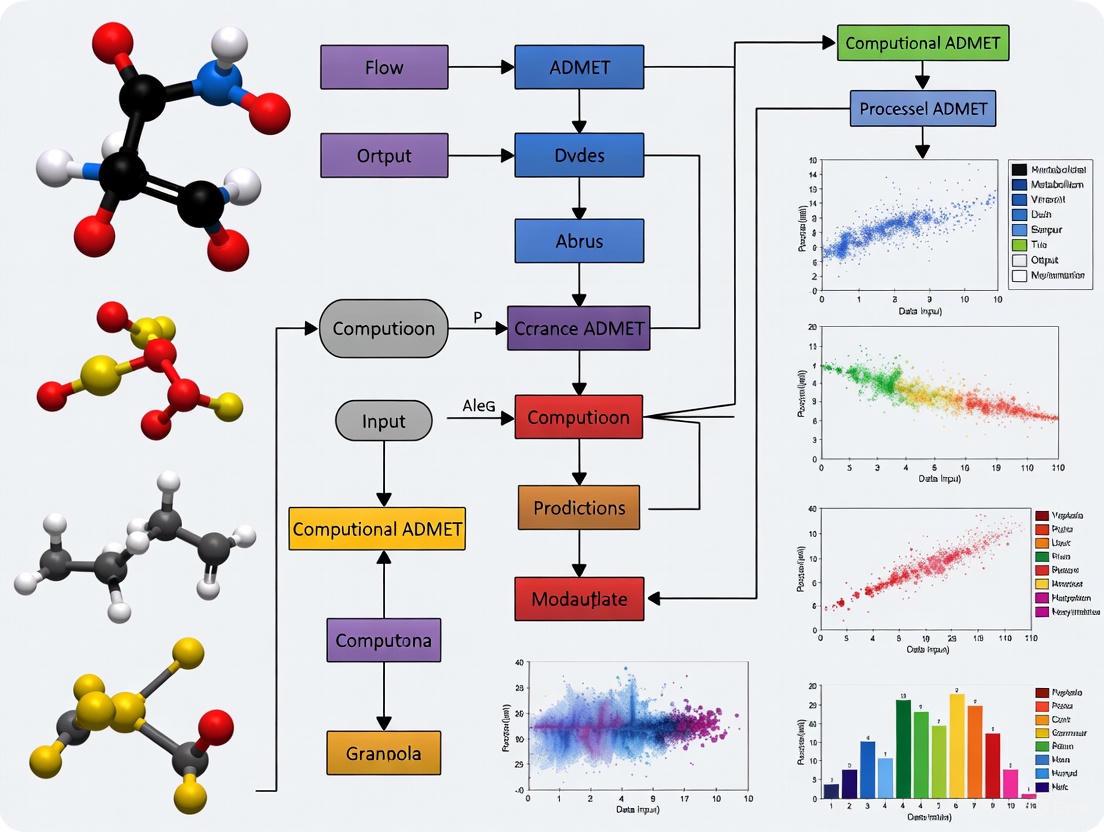

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative cycle for validating computational ADMET models, integrating the troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols outlined above.

ADMET Model Validation Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Validation.

| Reagent / Material | Function in ADMET Validation |

|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Key enzyme source for in vitro metabolism and clearance studies to predict human pharmacokinetics [7]. |

| Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes | Gold-standard cell model for studying hepatic metabolism, toxicity (DILI), and enzyme induction [7] [2]. |

| hERG-Expressing Cell Lines | Essential for in vitro assessment of a compound's potential to cause lethal cardiotoxicity [5] [3]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model of human intestinal epithelium used to predict oral absorption and P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux [2]. |

| 3D Cell Culture Systems / Organoids | Physiologically relevant models for more accurate toxicity screening and efficacy testing, reducing reliance on animal models [6] [3]. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Cofactor required for cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme activity in metabolic stability and drug-drug interaction assays [2]. |

In the landscape of drug discovery, the high failure rate of clinical candidates represents a massive financial and scientific burden. Industry analyses consistently reveal that approximately 40–45% of clinical attrition is directly attributed to poor Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties [1]. For every 5,000–10,000 chemical compounds that enter the drug discovery pipeline, only 1–2 ultimately reach the market, a process that can take 10–15 years [8]. This attrition crisis underscores the critical need for robust predictive models and reliable experimental validation frameworks to identify ADMET liabilities earlier in the development process. The integration of computational predictions with high-quality experimental data forms the cornerstone of modern strategies to mitigate these risks and reduce late-stage failures.

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my computational ADMET model perform well on internal validation but fails to predict prospective compound liabilities accurately?

A: This common issue often stems from limited chemical diversity in training data. Models trained on a single organization's data describe only a small fraction of relevant chemical space [1]. The problem may also involve inappropriate dataset splitting; models should be evaluated using scaffold-based splits that simulate real-world application on structurally distinct compounds, rather than random splits [9]. Additionally, assay variability between your training data and prospective compounds can cause discrepancies. A recent study found almost no correlation between IC50 values for the same compounds tested by different groups, highlighting significant reproducibility challenges in literature data [10].

Q2: How can I determine if my ADMET model's predictions are reliable for a specific chemical series?

A: Systematically define your model's applicability domain by analyzing the relationship between your training data and the compounds being predicted [10]. For cytochrome P450 predictions specifically, ensure you're distinguishing between substrate and inhibitor predictions, as these represent distinct biological endpoints with different clinical implications [11]. Implement uncertainty quantification methods; the confidence in a prediction should be estimable from the training data used, though prospective validation of these estimates remains challenging [10].

Q3: What are the best practices for validating my ADMET model against experimental data?

A: Participate in blind challenges, which provide the most rigorous assessment of predictive performance on unseen compounds [10] [12]. Follow rigorous method comparison protocols that benchmark against various null models and noise ceilings to distinguish real gains from random noise [1]. For experimental validation, use scaffold-based cross-validation across multiple seeds and folds, evaluating a full distribution of results rather than a single score [1].

Q4: When should I use a global model versus a series-specific local model for ADMET prediction?

A: The choice depends on your chemical space coverage and data availability. Federated models that learn across multiple pharmaceutical organizations' datasets systematically outperform local baselines, with performance improvements scaling with participant diversity [1]. However, for specialized chemical series with sufficient data, local models may capture domain-specific relationships more effectively. OpenADMET initiatives are gathering diverse datasets to enable systematic comparisons between these approaches [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor correlation between predicted and experimental metabolic stability values

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Assay variability | Compare protocol details with model's training data sources; check for consistency in experimental conditions (e.g., microsomal lots, incubation times). | Re-normalize data or fine-tune model on consistent assay protocols; use federated learning approaches that account for heterogeneous data [1]. |

| Incorrect species specificity | Verify whether the model was trained on human vs. mouse liver microsomal data and that predictions align with the appropriate species. | Use species-specific models; for human predictions, ensure training data comes from human liver microsomes (HLM) rather than mouse (MLM) [12]. |

| Limited applicability domain | Calculate similarity scores between your compounds and the model's training set compounds. | Apply domain-of-applicability filters; use models with expanded chemical space coverage through federated learning [1]. |

Problem: Discrepancies between different software tools for the same ADMET endpoint

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Different training data | Investigate the original data sources and curation methods for each software tool. | Use tools with transparent, well-documented data provenance; prefer models trained on consistently generated data [10]. |

| Variant feature representations | Check whether tools use different molecular representations (fingerprints, descriptors, graph representations). | Use ensemble approaches that combine multiple features types; XGBoost with feature ensembles ranks first in 18 of 22 ADMET benchmark tasks [9]. |

| Differing algorithm architectures | Determine if tools use different underlying algorithms (e.g., XGBoost vs. Graph Neural Networks). | Understand algorithm strengths: graph-based models excel at representing molecular structures, while tree-based models often outperform on tabular data [11] [9]. |

Quantitative Data: ADMET Performance Benchmarks

| ADMET Endpoint | Metric | Top Performing Model | Performance Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco2 Permeability | MAE | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.234 (MAE) |

| Human Liver Microsomal (HLM) CLint | MAE | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.366 (MAE) |

| Solubility (LogS) | MAE | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.631 (MAE) |

| hERG Inhibition | AUC | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.856 (AUC) |

| CYP2C9 Inhibition | AUC | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.863 (AUC) |

| CYP2D6 Inhibition | AUC | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.849 (AUC) |

| CYP3A4 Inhibition | AUC | XGBoost Ensemble | 0.856 (AUC) |

| Endpoint | Property Measured | Units | Relevance to Clinical Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogD | Lipophilicity at specific pH | Unitless | Impacts absorption, distribution, and metabolism |

| Kinetic Solubility (KSOL) | Dissolution under non-equilibrium conditions | µM | Affects oral bioavailability and formulation |

| HLM CLint | Human liver metabolic clearance | mL/min/kg | Predicts in vivo liver metabolism and clearance |

| MLM Stability | Mouse liver metabolic stability | mL/min/kg | Informs preclinical to clinical translation |

| Caco-2 Papp A>B | Intestinal absorption mimic | 10^-6 cm/s | Predicts oral absorption potential |

| Plasma Protein Binding | Free drug concentration in plasma | % Unbound | Impacts efficacy and dosing requirements |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Rigorous ADMET Model Validation

- Data Curation and Sanity Checks: Carefully validate datasets, performing sanity and assay consistency checks with normalization. Slice data by scaffold, assay, and activity cliffs to assess modelability [1].

- Scaffold-Based Splitting: Split datasets using scaffold-based approaches that separate structurally distinct compounds, simulating real-world prediction scenarios on novel chemotypes [1] [9].

- Multi-Seed Cross-Validation: Train and evaluate models using scaffold-based cross-validation runs across multiple seeds and folds, evaluating a full distribution of results rather than a single score [1].

- Statistical Testing: Apply appropriate statistical tests to result distributions to separate real gains from random noise. Benchmark against various null models and noise ceilings [1].

- Blinded Prospective Validation: Submit predictions for blinded test sets in community challenges where ground truth data is held by independent organizers [12].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Metabolic Stability Assessment

- Incubation Setup: Prepare liver microsomes (human or mouse) from pooled donors in appropriate buffer systems. Include positive control compounds with known metabolic profiles.

- Compound Exposure: Add test compounds at relevant concentrations (typically 1µM) and initiate reactions with NADPH cofactor.

- Timepoint Sampling: Remove aliquots at multiple timepoints (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45 minutes) and quench reactions with organic solvent.

- Analytical Quantification: Use LC-MS/MS to measure parent compound disappearance over time.

- Data Analysis: Calculate intrinsic clearance (CLint) values from the slope of the natural log of compound concentration versus time. Compare to reference compounds [12].

Visualizing ADMET Validation Workflows

Diagram 1: ADMET Model Validation Framework

Diagram 2: Multi-Tiered ADMET Validation Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Validation

| Reagent/System | Function in ADMET Validation | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Models intestinal absorption and permeability | Predicts oral bioavailability and efflux transporter effects [12] |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Contains major CYP450 enzymes for metabolism studies | Metabolic stability assessment, drug-drug interaction potential [11] [12] |

| Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLM) | Species-specific metabolic enzyme source | Preclinical to clinical translation, species comparison studies [12] |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Individual cytochrome P450 isoform studies | Enzyme-specific metabolism and inhibition profiling [11] |

| MDCK-MDR1 Cells | P-glycoprotein transporter activity assessment | Blood-brain barrier penetration, efflux transporter substrate identification |

| Plasma Protein Binding Kits | Determination of free drug fraction | Estimation of effective concentration and dosing requirements [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the Applicability Domain (AD) and why is it a mandatory requirement for QSAR models?

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the boundaries within which a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) model's predictions are considered reliable. It represents the chemical, structural, or biological space covered by the model's training data. Predictions for compounds within the AD are more reliable because the model is primarily valid for interpolation within this known space, rather than extrapolation beyond it. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) states that defining the applicability domain is a fundamental principle for having a valid QSAR model for regulatory purposes [13] [14].

2. My model performs well on the test set but fails prospectively. How can AD analysis help?

This common issue often occurs when the test set compounds are structurally similar to the training set, but prospective compounds are not. A well-defined Applicability Domain helps you identify when a new compound is structurally or chemically distant from the compounds used to train the model. If a compound falls outside the AD, the model's prediction for it is less reliable, as the model is essentially extrapolating. Using AD analysis allows you to flag such predictions, prompting further scrutiny or experimental validation, thus managing the risk of model failure in real-world applications [13] [15].

3. What is the difference between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty, and why does it matter?

Understanding the source of uncertainty is crucial for deciding how to address it.

- Aleatoric uncertainty refers to the inherent stochastic variability or noise in the experimental data itself. It is often considered irreducible because it cannot be mitigated by collecting more data. In drug discovery, this can reflect biological stochasticity or human intervention during experiments [16].

- Epistemic uncertainty stems from the model's lack of knowledge, which can be due to insufficient training data or model limitations. Unlike aleatoric uncertainty, it can be reduced by acquiring more relevant data or improving the model [16]. Distinguishing between them helps in risk management. High aleatoric uncertainty highlights inherently unpredictable areas, while high epistemic uncertainty points to regions of chemical space where your model would benefit from additional data [16].

4. What are some practical methods to define the Applicability Domain of my model?

There is no single, universally accepted algorithm, but several methods are commonly employed [13]. The choice of method can depend on the model type and the nature of the descriptors.

Table: Common Methods for Defining Applicability Domain

| Method Category | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Range-Based | Checks if the descriptor values of a new compound fall within the range of the training set descriptors. | Bounding Box [13]. |

| Distance-Based | Measures the distance of a new compound from the training set in the descriptor space. | Leverage values (Hat matrix), Euclidean distance, Mahalanobis distance [13] [14]. |

| Geometrical | Defines a geometric boundary that encompasses the training set data points. | Convex Hull [13]. |

| Density-Based | Estimates the probability density of the training data to identify sparse and dense regions in the chemical space. | Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [15]. |

5. How can I incorporate censored data labels to improve uncertainty quantification?

In drug discovery, assays often have measurement limits, resulting in censored labels (e.g., "IC50 > 10 μM"). Standard regression models ignore this partial information. To leverage it, you can adapt ensemble-based, Bayesian, or Gaussian models using tools from survival analysis, such as the Tobit model. This approach allows the model to learn from the threshold information provided by censored labels, leading to more accurate predictions and better uncertainty estimation, especially for compounds with activities near the assay limits [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Epistemic Uncertainty in Predictions Issue: Your model shows high epistemic uncertainty for many compounds, indicating a lack of knowledge in those regions of chemical space. Solution:

- Identify the Gap: Use AD methods like leverage or distance-based measures to confirm that these compounds are far from the training set distribution [13] [14].

- Strategic Data Acquisition: Focus your experimental resources on synthesizing and testing compounds that reside in these high-uncertainty regions. This actively reduces the model's epistemic uncertainty [16].

- Model Retraining: Incorporate the new experimental data into your training set and retrain the model. This expands the model's Applicability Domain and increases its confidence in previously uncertain areas.

Problem: Poor Model Performance on Out-of-Domain Compounds Issue: The model provides inaccurate predictions for compounds that are structurally dissimilar to its training set. Solution:

- Implement an AD Filter: Before trusting any prediction, calculate its position relative to the model's AD. Define a threshold for a suitable distance metric (e.g., leverage, Euclidean distance to nearest neighbor) [14].

- Flag and Handle OoD Predictions: Automatically flag predictions that fall outside the AD. Do not treat these predictions with the same confidence as in-domain predictions.

- Use a More Robust AD Method: Consider using a density-based method like Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), which can better handle complex and disconnected regions of chemical space compared to a simple convex hull, leading to a more accurate domain classification [15].

Problem: Inaccurate Uncertainty Estimates on New Data Issue: The predicted uncertainty intervals do not reliably reflect the actual prediction errors when the model is applied to new data. Solution:

- Calibrate Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Employ methods specifically designed for UQ, such as Conformal Prediction, which provides calibrated prediction intervals that are valid under weak assumptions [17].

- Evaluate on Realistic Splits: Test your model's UQ using a temporal split of data (if available) or a scaffold split, rather than a random split. This provides a more realistic assessment of how the model and its uncertainty estimates will perform on truly novel compounds [16].

- Leverage Censored Data: If your historical data contains censored labels, use adapted models that can learn from this partial information to improve both the accuracy and the reliability of uncertainty estimates [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing the Applicability Domain Using a Leverage-Based Approach

This protocol uses the leverage of a compound to determine its distance from the model's training data.

- Compute the Hat Matrix: For a given QSAR model with descriptor matrix ( X ), the hat matrix is calculated as ( H = X(X^T X)^{-1} X^T ) [13] [14].

- Calculate Leverage: The leverage for a compound ( i ) is the corresponding diagonal element of the hat matrix, ( h_{ii} ). Calculate the leverage values for all compounds in the training set [13].

- Define the Warning Leverage: The warning leverage (( h^* )) is typically set as ( h^* = 3p/n ), where ( p ) is the number of model descriptors plus one, and ( n ) is the number of training compounds [13].

- Apply to New Compounds: For a new compound, compute its leverage ( h{new} ). If ( h{new} > h^* ), the compound is considered to have high leverage and may be outside the model's Applicability Domain, and its prediction should be treated with caution [13].

Protocol 2: Implementing Conformal Prediction for Reliable Uncertainty Intervals

Conformal Prediction (CP) is a framework that produces prediction intervals with guaranteed coverage probabilities.

- Split the Data: Divide the labeled data into a proper training set and a calibration set.

- Train the Model: Train your predictive model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on the proper training set.

- Calculate Nonconformity Scores: Use the calibration set to compute a nonconformity score for each compound, which measures how dissimilar a compound is from the training set. A common score is the absolute difference between the predicted and actual value [17].

- Generate Prediction Intervals: For a new compound with an unknown value ( y ), form a set of candidate values. For each candidate, compute a nonconformity score and check if it is consistent with the scores from the calibration set. The prediction interval contains all candidate values that are sufficiently conformal, typically based on a pre-specified significance level ( \epsilon ) (e.g., 0.05 for a 95% prediction interval) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Computational Reagents for ADMET Model Validation

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of molecular structures that encode chemical and structural information. They form the feature space for QSAR models and AD calculation [18]. |

| Applicability Domain Method (e.g., KDE, Leverage) | A defined algorithm used to establish the boundaries of reliable prediction for a model. It is crucial for interpreting model results and assessing prediction reliability [13] [15]. |

| Conformal Prediction Framework | A statistical tool that provides valid prediction intervals for model outputs, offering calibrated uncertainty quantification that is not dependent on the underlying model assumptions [17]. |

| High-Quality/Curated ADMET Dataset | Experimental data for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties. The quality and relevance of this data are the most critical factors in building reliable models [10] [18]. |

| Censored Data Handler (e.g., Tobit Model) | A statistical adaptation that allows regression models to learn from censored experimental labels (e.g., IC50 > 10μM), thereby improving prediction accuracy and uncertainty estimation [16]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Model Prediction and Validation Workflow

This diagram illustrates the logical sequence for validating a computational prediction. A new compound is processed, and a prediction is made. The critical step is evaluating its position relative to the model's Applicability Domain, which directly determines the confidence level assigned to the prediction.

Deconstructing Predictive Uncertainty

This chart breaks down the two fundamental types of uncertainty in predictive modeling, their sources, key properties, and the appropriate strategies to address each one.

FAQs on Core Data Challenges

1. What are the primary data-related causes of model failure in computational ADMET? Model failure in computational ADMET is primarily linked to data quality and composition. Key issues include [18]:

- Low-quality data: Models trained on noisy, biased, or incorrect data will amplify these flaws. This is especially critical for models that learn continuously from uncurated new data [19].

- Data imbalance: Imbalanced datasets are a recognized challenge, where a lack of sufficient data for rare events (e.g., specific toxicity endpoints) leads to poor model performance on these critical cases [18].

- Use of unvalidated synthetic data: Relying solely on synthetic data without human oversight can result in models that perform well on simulated data but fail dramatically in real-world scenarios [19].

2. How does "model collapse" relate to my internal ADMET model training data? Model collapse is a degenerative process where a model's performance severely degrades after being trained on data generated by previous versions of itself. In an ADMET context, this doesn't look like gibberish but like a model that gradually "forgets" rare but critical patterns [20]. For example, a model trained recursively on its own predictions might eventually fail to flag rare, high-risk toxicological events, as these "tail-end" patterns vanish from the training data over successive generations [20].

3. What is the most effective strategy to prevent model degradation from poor data? A proactive, systemic strategy is to integrate Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) annotation. This involves humans actively reviewing, correcting, and annotating data throughout the machine learning lifecycle. HITL combines the speed and scale of AI with human nuance and judgment, creating a continuous feedback loop that immunizes models against drift and collapse by providing fresh, accurate, validated data for retraining [19].

4. Our experimental data comes from multiple labs and is highly variable. How can we use it for modeling? The key is robust data preprocessing. Before model training, data must undergo cleaning and normalization to ensure quality and consistency [18]. Furthermore, feature selection methods are crucial. These methods help determine the most relevant molecular descriptors or properties for a specific prediction task, reducing noise from redundant or non-informative variables and improving model accuracy [18].

5. Where can we find reliable public data for building or validating ADMET models? Several public databases provide pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties for robust model training and validation. The table below summarizes some of these key resources [18].

Table: Key Considerations for Public ADMET Data Repositories

| Consideration | Description |

|---|---|

| Data Provenance | Always verify the original source and experimental methods used to generate the data. |

| Standardization | Check if data from different studies has been normalized or is directly comparable. |

| Completeness | Assess the extent of missing data for critical endpoints or descriptors. |

| Documentation | Review the available metadata, which is essential for understanding the context of each data point. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performance is Poor on Rare Events (Sparse Data)

| Symptom | Investigation Question | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High accuracy on common endpoints but failures on rare toxicities. | Is the training data imbalanced? | Up-weight the tails. Intentionally oversample data from rare, high-risk categories (e.g., specific toxicity syndromes) during training [20]. |

| Model fails to generalize for underrepresented biological pathways. | Does my evaluation set cover edge cases? | Freeze gold tests. Maintain a fixed, human-curated set of test vignettes for rare events. Never use this set for training; use it solely to evaluate model performance on critical edge cases [20]. |

| Performance degrades over time as the model is retrained. | Are we in a model collapse feedback loop? | Blend, don't replace. Always keep a fixed percentage (e.g., 25-30%) of the original, high-fidelity human/experimental data in every retraining cycle to anchor the model to reality [20] [19]. |

Issue: Inconsistent Data from Multiple Sources (Variable & Non-Standardized Data)

| Symptom | Investigation Question | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty merging datasets from different labs or public sources. | Are we comparing apples to apples? | Implement a unified data layer. Use centralized repositories with structured data objects and clear metadata governance, replacing fragmented document-centric models. This ensures real-time traceability and compliance with data integrity principles [21]. |

| Model predictions are unstable and unreliable. | Have we reduced feature redundancy? | Apply feature selection. Use filter, wrapper, or embedded methods to identify and use only the most relevant molecular descriptors, eliminating noise from correlated or irrelevant variables [18]. |

| The data pipeline is slow and error-prone. | Is our validation process data-centric? | Adopt dynamic protocol generation. Leverage AI-driven systems to analyze data characteristics and auto-generate context-aware validation and preprocessing scripts, moving away from rigid, manual protocols [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Resource Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for ADMET Model Development

| Item / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Public ADMET Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) | Provide large-scale, publicly available datasets of pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties for initial model training and benchmarking [18]. |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculation Software (e.g., Dragon, PaDEL) | Generates numerical representations of chemical structures based on 1D, 2D, or 3D information. These descriptors are the essential input features for most QSAR and machine learning models [18]. |

| Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Annotation Platform | Provides a structured framework for human experts to review, correct, and annotate model outputs and complex edge cases, ensuring a continuous flow of high-quality data for model refinement [19]. |

| Feature Selection Algorithms (CFS, Wrapper Methods) | Identifies the most relevant molecular descriptors from a large pool of candidates for a specific prediction task, improving model accuracy and reducing overfitting [18]. |

| Standardized Bioassay Protocols | Detailed, consistent experimental methodologies for generating new ADMET data. They are critical for ensuring that new data produced in-house or across collaborators is consistent, reliable, and comparable [18]. |

Experimental Data Management & Model Validation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a robust workflow for managing experimental data and validating computational models, integrating key steps to mitigate data challenges.

Human-in-the-Loop Model Refinement System

This diagram illustrates the continuous feedback loop of a Human-in-the-Loop system, which is critical for maintaining model reliability and preventing collapse.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and scientists navigate the regulatory landscape for AI/ML models, specifically within the context of validating computational ADMET models with experimental data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core of the FDA's proposed framework for AI model credibility? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed a risk-based credibility assessment framework for AI models used to support regulatory decisions on drug safety, effectiveness, or quality [22] [23] [24]. This framework is a multi-step process designed to establish trust in a model's output for a specific Context of Use (COU). The COU clearly defines the model's role and the question it is intended to address [24].

2. What are the key watch-points for AI/ML model training from a regulatory perspective? Regulatory expectations for training AI/ML models, especially in a medical product context, focus on several critical areas [25]:

- Data Lineage and Splits: Document the origin, justification, and splitting strategy (training/validation/test) of your data.

- Bias and Fairness: Evaluate and mitigate bias to ensure consistent model performance across relevant demographic subgroups.

- Linkage to Clinical Claim: Clearly document how the model's architecture and logic support the specific clinical or research claim.

- Lifecycle Strategy: Define whether the model is "locked" at release or is adaptive, and have a plan (like a Predetermined Change Control Plan) for post-market updates.

- Monitoring and Feedback: Build plans for post-deployment performance monitoring and feedback loops from the start.

- Documentation and Quality Systems: Maintain rigorous version control and documentation for datasets, code, and model artifacts within a quality system.

3. How does the European Medicines Agency (EMA) view the use of AI in the medicinal product lifecycle? The EMA encourages the use of AI to support regulatory decision-making and recognizes its potential to get safe and effective medicines to patients faster [26]. The agency has published a reflection paper offering considerations for the safe and effective use of AI and machine learning throughout a medicine's lifecycle [26]. A significant milestone was reached in March 2025 when the EMA's human medicines committee (CHMP) issued its first qualification opinion for an AI methodology, accepting clinical trial evidence generated by an AI tool for diagnosing a liver disease [26].

4. What are the most common pitfalls that lead to performance degradation in deployed AI models? A major pitfall is training models only on pristine, high-quality data without accounting for real-world variability [25]. This can lead to poor performance when the model encounters:

- Data Drift: Changes in the distribution of input data over time.

- Real-World Noise: Variations in data sources, such as different imaging devices or patient populations with comorbidities.

- Edge Cases: Rare or unusual scenarios not well-represented in the training set.

5. My AI model will evolve with new data. What is the regulatory pathway for such adaptive models? For adaptive AI/ML models, regulators expect a proactive plan for managing changes. The FDA's traditional paradigm is not designed for continuously learning technologies, and they now recommend a Total Product Lifecycle (TPLC) approach [25]. A key tool is the Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP), which you can submit for your device. The PCCP should outline the types of anticipated changes (SaMD Pre-Specifications) and the detailed protocol (Algorithm Change Protocol) for validating those future updates [25]. Japan's PMDA has a similar system called the Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common AI/ML Model Validation Issues

| Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Model performs well in validation but fails in real-world use. | Data drift; real-world data differs from training/validation sets. | Implement continuous monitoring to detect data and concept drift. Use a more diverse dataset that reflects real-world variability for training [25]. |

| Model shows biased or unfair outcomes for specific subgroups. | Unmitigated bias in training data; lack of representative data for all subgroups. | Perform bias detection and fairness audits during development. Use challenge sets to stress-test the model on under-represented populations and document the results [28] [25]. |

| Regulatory agency questions model transparency and explainability. | Use of complex "black box" models without adequate explanation of decision-making process. | Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP or LIME. Provide a "model traceability matrix" linking inputs, logic, and outputs to the clinical/research claim [28] [25]. |

| Difficulty reproducing model training and results. | Lack of version control for datasets, code, and model artifacts; incomplete documentation. | Implement rigorous version control and maintain an audit trail for all components. Treat data and model artifacts as regulated components within a quality system [25]. |

| Uncertainty in quantifying model prediction confidence. | Model does not provide uncertainty estimates; challenges in interpreting model precision. | Focus on uncertainty quantification as part of the model's output. This is a known challenge highlighted by regulators and should be addressed in the model's credibility assessment [27]. |

Regulatory Framework Comparison

The table below summarizes the key regulatory approaches for AI/ML models in drug development from the FDA and EMA.

| Aspect | U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration) | EMA (European Medicines Agency) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Guidance | Draft Guidance: "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence..." (Jan 2025) [22] | Reflection Paper on AI in the medicinal product lifecycle (Oct 2024) [26] |

| Primary Focus | Risk-based credibility assessment framework for a specific Context of Use (COU) [22] [24] | Safe and effective use of AI throughout the medicine's lifecycle, in line with EU legal requirements [26] |

| Key Methodology | Seven-step credibility assessment process [24] [27] | Risk-based approach for development, deployment, and monitoring; first qualification opinion issued in 2025 [26] [27] |

| Lifecycle Approach | Encourages a Total Product Lifecycle (TPLC) approach, with Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCP) for adaptive models [25] | Integrated into the workplan of the Network Data Steering Group (2025-2028), focusing on guidance, tools, collaboration, and experimentation [26] |

| Documentation Emphasis | Documentation of the credibility assessment plan and results; model traceability [22] [25] | Robust documentation, data integrity, traceability, and human oversight in line with GxP standards [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Regulatory Tests

Protocol for Bias Detection and Fairness Audit

This protocol is essential for establishing model fairness, a key regulatory expectation [28] [25].

- Objective: To identify and quantify unwanted bias in the AI model's predictions against sensitive demographic subgroups (e.g., based on age, sex, race/ethnicity).

- Materials: A held-out test dataset that is diverse and representative of the intended population, with annotations for sensitive attributes.

- Procedure:

- Stratify Test Data: Split the test dataset into subgroups based on the sensitive attributes.

- Run Predictions: Use the trained AI model to generate predictions on the entire test set and on each subgroup.

- Calculate Metrics: Compute performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) for the overall population and for each subgroup.

- Compare Performance: Analyze disparities in metrics across subgroups. Common techniques include disparate impact analysis.

- Mitigate (if found): If significant bias is detected, mitigation strategies may include re-sampling the training data, using fairness-aware algorithms, or refining features.

- Reporting: Document the methodology, all results, and any mitigation actions taken. This is critical for regulatory submissions [25].

Protocol for Robustness and Stress Testing

This protocol tests the model's resilience to imperfect or unexpected inputs, validating its real-world reliability [28] [25].

- Objective: To evaluate the model's performance under challenging conditions, such as noisy, incomplete, or out-of-distribution data.

- Materials: The primary test dataset, plus a separate "challenge set" containing edge cases, adversarial examples, and data that simulates real-world noise.

- Procedure:

- Baseline Performance: Establish a baseline performance on the clean, primary test dataset.

- Introduce Variations: Systematically introduce variations to the test data. This could include:

- Adding random noise to input data.

- Simulating missing data points.

- Using out-of-distribution samples (data the model was not trained on).

- Re-evaluate Performance: Run the model on these modified datasets and record the performance metrics.

- Analyze Degradation: Quantify the performance drop compared to the baseline. A robust model will show minimal degradation.

- Reporting: Document the types of variations tested, the corresponding performance results, and an analysis of the model's limitations.

Workflow Diagrams

FDA AI Model Credibility Assessment

AI Model Lifecycle Management

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists key tools and frameworks mentioned in regulatory discussions that are essential for developing and validating robust AI/ML models.

| Tool / Framework | Category | Primary Function in AI/ML Validation |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explainable AI (XAI) | Interprets complex model output by quantifying the contribution of each feature to a single prediction, enhancing transparency [28] [29]. |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Explainable AI (XAI) | Creates a local, interpretable model to approximate the predictions of any black-box model, aiding in explainability [28] [29]. |

| Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) | Regulatory Strategy | A formal plan submitted to regulators outlining anticipated future modifications to an AI model and the protocol for validating them, crucial for adaptive models [25]. |

| Disparate Impact Analysis | Bias & Fairness | A statistical method to measure bias by comparing the model's outcome rates between different demographic groups [28] [29]. |

| Version Control Systems (e.g., Git) | Documentation & Reproducibility | Tracks changes to code, datasets, and model parameters, ensuring full reproducibility and auditability for regulatory scrutiny [25]. |

| Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) | Guiding Principles | A set of principles established by the FDA to guide the design, development, and validation of ML-enabled medical devices, promoting best practices [25] [27]. |

Next-Generation Methods for Building and Testing ADMET Models

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing Graph Neural Networks and Transformers for molecular representation, with a specific focus on validating computational ADMET models.

FAQ 1: My model performs well during training but generalizes poorly to external test sets or experimental data. How can I improve its real-world applicability?

Poor generalization often stems from data quality and splitting issues, not just model architecture [10]. Unlike potency optimization, ADMET optimization often relies on heuristics, and models trained on low-quality data are unlikely to succeed in practice [10].

- Root Cause 1: Low-Quality or Inconsistent Training Data. A primary issue is using datasets curated inaccurately from dozens of publications, where the same compounds tested in the "same" assay by different groups show almost no correlation [10].

- Solution: Prioritize high-quality, consistently generated experimental data from relevant assays. Initiatives like OpenADMET are generating such data specifically for building reliable models [10]. Always check the provenance and consistency of your training data.

- Root Cause 2: Incorrect Data Splitting. A model's performance is often evaluated with a random split of the data. However, this can lead to data leakage and over-optimistic performance if the model is tested on molecules very similar to those it was trained on [10].

- Solution: For a more realistic assessment of a model's predictive power, use a time-split or scaffold-split. Evaluate models prospectively through blind challenges where predictions are made for compounds the model has never seen before [10].

FAQ 2: I am encountering a "CUDA out of memory" error during training. What are the most effective ways to reduce memory usage?

This is a common issue when training large models, especially with 3D structural information [30].

- Immediate Action: Reduce the

per_device_train_batch_sizevalue in your training arguments. This is the most direct way to lower memory consumption [30]. - Advanced Strategy: Implement gradient accumulation. This technique allows you to effectively use a larger overall batch size by accumulating gradients over several forward/backward passes before updating the model weights [30].

FAQ 3: How can I effectively integrate prior molecular knowledge (like fingerprints) into a deep learning model?

Combining graph-based representations with descriptor-based representations often leads to better model performance [31].

- Solution: Use molecular fingerprints as complementary input features. For example, the FP-GNN model integrates three types of molecular fingerprints with graph attention networks [31]. The MoleculeFormer architecture incorporates prior molecular fingerprints alongside features learned from atomic and bond graphs [31].

- Fingerprint Selection: The choice of fingerprint can be task-dependent. For classification tasks, ECFP and RDKit fingerprints are often strong performers, while for regression tasks, MACCS keys or a combination of MACCS and EState fingerprints may be more effective [31].

FAQ 4: How can I make my GNN or Transformer model more interpretable for a drug discovery team?

Interpretability is crucial for building trust and guiding chemical design.

- Attention Mechanisms: Models like MoleculeFormer use attention mechanisms to highlight which parts of a molecular structure (atoms or bonds) have a greater impact on the prediction. This can be visualized to provide mechanistic insights [31].

- KAN Integration: Newer architectures like Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) offer improved interpretability by highlighting chemically meaningful substructures, as they use learnable univariate functions that can be more transparent than standard MLPs [32].

Performance Comparison of Advanced Architectures

The table below summarizes the performance of various advanced architectures on molecular property prediction tasks, providing a quantitative basis for model selection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representation Architectures

| Architecture | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoleculeFormer [31] | Integrates GCN and Transformer modules; uses atomic & bond graphs. | Robust performance across 28 datasets in efficacy/toxicity, phenotype, and ADME evaluation [31]. | Tasks requiring integration of multiple molecular views (atom, bond, 3D). |

| KA-GNN (Kolmogorov-Arnold GNN) [32] | Replaces MLPs with Fourier-based KANs in node embedding, message passing, and readout. | Consistently outperforms conventional GNNs in accuracy and computational efficiency on seven benchmarks [32]. | Researchers prioritizing accuracy, parameter efficiency, and interpretability. |

| Transformer (without Graph Priors) [33] | Uses standard Transformer on Cartesian coordinates, without predefined graphs. | Competitive energy/force mean absolute errors vs. state-of-the-art equivariant GNNs; learns distance-based attention [33]. | Scalable molecular modeling; cases where hard-coded graph inductive biases may be limiting. |

| FP-GNN [31] | Integrates multiple molecular fingerprints with graph attention networks. | Enhances model performance and interpretability compared to graph-only models [31]. | Leveraging prior knowledge from molecular fingerprints to boost graph-based learning. |

Table 2: Performance of Molecular Fingerprints on Different Task Types (from MoleculeFormer study) [31]

| Fingerprint Type | Classification Task (Avg. AUC) | Regression Task (Avg. RMSE) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP + RDKit | 0.843 | - | Optimal combination for classification tasks [31]. |

| MACCS + EState | - | 0.464 | Optimal combination for regression tasks [31]. |

| ECFP (Single) | 0.830 | - | Standout single fingerprint for classification [31]. |

| MACCS (Single) | - | 0.587 | Standout single fingerprint for regression [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Architectures

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and validating key advanced architectures.

Protocol: Implementing the MoleculeFormer Architecture

MoleculeFormer is a multi-scale feature integration model designed for robust molecular property prediction [31].

1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering:

- Input Representations: Generate both an atom graph (atoms as nodes) and a bond graph (bonds as nodes) for each molecule.

- Feature Sets: For the atom graph, include features like atomic number and valence electrons. For the bond graph, include bond type and, if available, bond length [31].

- 3D Information: Incorporate 3D structural information while applying rotational equivariance constraints to ensure the model is invariant to rotation and translation [31].

- Molecular Fingerprints: Generate a combination of molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP and RDKit for classification; MACCS and EState for regression) to be used as complementary input features [31].

2. Model Architecture Setup:

- Independent Modules: Use independent Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) and Transformer modules to extract features from the atom and bond graphs.

- Graph-Representation Node: Introduce a special graph-representation node (inspired by NLP) that interacts with all other nodes via the Transformer's attention mechanism. This avoids the information loss associated with traditional pooling operations [31].

- Feature Integration: Fuse the outputs from the GCN modules, Transformer modules, and the molecular fingerprint embeddings for the final prediction.

3. Training and Interpretation:

- Training: Train the model end-to-end on the target property prediction task.

- Interpretation: Use the attention weights from the Transformer module to analyze the correlation between the graph-representation node and each atom/bond node. This allows you to identify which parts of the molecule the model "attends to" for its prediction [31].

Protocol: Implementing KA-GNN (Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Network)

KA-GNNs leverage the Kolmogorov-Arnold theorem to enhance the expressiveness and interpretability of standard GNNs [32].

1. Fourier-Based KAN Layer Setup:

- Core Idea: Replace the standard linear transformations and fixed activation functions (e.g., ReLU) in an MLP with learnable univariate functions (using Fourier series) on the edges of the network.

- Implementation: The Fourier-based KAN layer uses a sum of sine and cosine functions with learnable coefficients. This allows the model to effectively capture both low-frequency and high-frequency patterns in the graph data [32].

2. Architectural Integration:

- KA-GCN Variant:

- Node Embedding: Compute a node's initial embedding by passing its atomic features and the average of its neighboring bond features through a KAN layer.

- Message Passing: Follow the standard GCN scheme but update node features using residual KAN layers instead of MLPs [32].

- KA-GAT Variant: Incorporate edge embeddings initialized with a KAN layer, in addition to KAN-based node features, within a graph attention framework [32].

3. Theoretical and Empirical Validation:

- Theoretical Grounding: The architecture is grounded in the strong approximation capabilities of Fourier series, as established by Carleson's theorem and Fefferman's multivariate extension [32].

- Validation: Empirically compare the fitting performance of the Fourier-KAN against a standard two-layer MLP on representative functions to confirm superior approximation capability [32].

Protocol: Training a Transformer Without Graph Priors

This protocol challenges the necessity of hard-coded graph structures by using a standard Transformer on atomic coordinates [33].

1. Input Representation:

- Data Format: Use the raw Cartesian coordinates of all atoms in a molecule as the primary input. No predefined graph (e.g., based on covalent bonds or distance cutoffs) should be constructed.

- Positional Encoding: While the standard Transformer may require positional information, the coordinates themselves provide this. The model must learn to interpret spatial relationships from the sequence of coordinates.

2. Model and Training:

- Architecture: Use a standard Transformer encoder architecture without any custom, physics-informed layers.

- Training Objective: Train the model to predict molecular energies and forces, matching the training compute budget of a state-of-the-art equivariant GNN for a fair comparison (e.g., on the OM2 5 dataset) [33].

- Analysis: After training, analyze the learned attention maps. The model should have discovered physically consistent patterns, such as attention weights that decay with increasing interatomic distance, without being explicitly programmed to do so [33].

Architectural Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and logical structures of the discussed architectures.

MoleculeFormer Multi-Scale Integration

KA-GNN Architectural Variants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and datasets essential for research in molecular representation learning.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Representation Learning

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ADMET Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenADMET Datasets [10] | Experimental Dataset | Provides high-quality, consistently generated experimental ADMET data. | Foundation for training and validating reliable models; addresses core data quality issues [10]. |

| RDKit [31] [34] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Generates canonical SMILES, molecular graphs, fingerprints (e.g., RDKit fingerprint), and descriptors. | Critical for data preprocessing, feature engineering, and representation conversion [31] [34]. |

| MoleculeNet [31] | Benchmark Suite | A collection of standardized molecular property prediction datasets. | Provides benchmark tasks for fair comparison of new architectures against existing models [31]. |

| OM2 5 Dataset [33] | Quantum Chemistry Dataset | Contains molecular conformations with associated energies and forces. | Used for training and benchmarking models on quantum mechanical properties [33]. |

| ZINC Database [34] | Compound Library | A public database of commercially available chemical compounds. | Source of drug-like molecules for pre-training or evaluating models [34]. |

Leveraging Multi-Task Learning to Improve Generalization and Data Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using Multi-Task Learning (MTL) over Single-Task Learning (STL) for ADMET prediction?

MTL improves generalization and data efficiency by leveraging shared information across related tasks. This is particularly beneficial for small-scale ADMET datasets, where pooling information from multiple endpoints yields more robust shared features and helps the model learn a more generalized representation of the chemical space. For example, the QW-MTL framework demonstrated that MTL significantly outperformed strong single-task baselines on 12 out of 13 standardized ADMET classification tasks [35].

Q2: During MTL training, I encounter unstable performance and slow convergence. What could be the cause?

This is a classic symptom of gradient conflict, where the gradients from different tasks point in opposing directions during optimization, creating interference and biased learning [36]. This is often due to large heterogeneity in task objectives, data sizes, and learning difficulties [35]. Solutions include implementing gradient balancing algorithms like FetterGrad [36] or using adaptive task-weighting schemes [35] [37].

Q3: How should I split my dataset for a multi-task ADMET project to avoid data leakage and ensure a realistic evaluation?

To prevent cross-task leakage and ensure rigorous benchmarking, you must use aligned data splits. This means maintaining the same train, validation, and test partitions for all endpoints, ensuring no compound in the test set has measurements in the training set for any task [37]. Preferred strategies include:

- Temporal Splits: Partition compounds based on experiment or database addition dates to simulate prospective prediction [37].

- Scaffold Splits: Group compounds by their core chemical scaffolds (e.g., Bemis-Murcko) to maximize structural diversity between splits and test performance on novel chemotypes [37].

Q4: My multi-task model performs well on some ADMET endpoints but poorly on others. How can I balance this?

This imbalance is common and requires dynamic loss balancing. Instead of using a simple average of task losses, employ a weighted scheme. The QW-MTL framework, for instance, uses a learnable exponential weighting mechanism that combines dataset-scale priors with adaptable parameters to dynamically adjust each task's contribution to the total loss during training [35] [37].

Q5: Can I use MTL effectively when I have very little labeled data for a specific ADMET task of interest?

Yes, this is a key strength of MTL. Frameworks like MGPT (Multi-task Graph Prompt Learning) are specifically designed for few-shot learning. By pre-training on a heterogeneous graph of various entity pairs (e.g., drug-target, drug-disease) and then using task-specific prompts, the model can transfer knowledge from data-rich tasks to those with limited data, enabling robust performance with minimal samples [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Symptoms: Model performance across all or most tasks is worse than their single-task counterparts.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low task relatedness | Calculate task-relatedness metrics (e.g., label agreement for chemically similar compounds) [37]. | Curate a more related set of ADMET endpoints for joint training. Remove tasks that are chemically or functionally divergent [37]. |

| Improper data splitting | Verify that your train/validation/test splits are aligned across all tasks and that no data has leaked from train to test [37]. | Re-split the dataset using a rigorous method like temporal or scaffold splitting to ensure a realistic and leak-free evaluation [37]. |

| Destructive gradient interference | Monitor the cosine similarity between task gradients during training. Consistent negative values indicate conflict [36]. | Implement an optimization algorithm that mitigates gradient conflict, such as FetterGrad [36] or AIM, which learns a policy to mediate destructive interference [37]. |

Issue 2: High Performance Variance on Small-Scale Tasks

Symptoms: Predictions for tasks with smaller datasets are erratic and have high uncertainty.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss function dominated by large-scale tasks | Inspect the magnitude of individual task losses at the start of training. The loss from large tasks may be orders of magnitude greater. | Implement an adaptive task-weighting strategy. The exponential sample-aware weighting in QW-MTL (w_t = r_t^softplus(logβ_t)) is designed for this [35] [37]. |

| Insufficient representation for small-task domains | The shared feature space may not capture patterns critical for the low-resource task. | Enrich the model's input features. Consider incorporating 3D quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., dipole moment, HOMO-LUMO gap) to provide a richer, physically-grounded representation that benefits all tasks [35]. |

Issue 3: Model Fails to Generalize to Novel Chemical Structures

Symptoms: The model performs well on the test set but fails in real-world applications on new compound series.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting to training scaffold domains | Check if your test set contains scaffolds that are well-represented in the training data. | Use a scaffold-based or maximum-dissimilarity split for both training and evaluation to ensure the model is tested on truly novel chemotypes [37]. |

| Limited molecular representation | The model may rely on a single, insufficient representation (e.g., only 2D graphs). | Adopt a multi-view fusion framework like MolP-PC, which integrates 1D molecular fingerprints, 2D molecular graphs, and 3D geometric representations to capture multi-dimensional molecular information [39]. |

Experimental Protocols for MTL in ADMET

Protocol 1: Implementing Dynamic Task Weighting with QW-MTL

This protocol outlines the methodology for implementing the learnable weighting scheme from the QW-MTL framework [35].

- Compute Dataset Scale Priors: For each task

t, calculate its relative dataset size:r_t = n_t / (Σ_i n_i), wheren_tis the number of samples for taskt. - Initialize Learnable Parameters: Initialize a learnable parameter vector

logβ_tfor all tasks. - Calculate Task Weights: For each task, compute the weight

w_t = r_t ^ softplus(logβ_t). Thesoftplusfunction ensures the exponent is always positive. - Compute Total Loss: The overall training loss is the weighted sum:

L_total = Σ_t ( w_t * L_t ), whereL_tis the loss for taskt. - Joint Optimization: Update both the model parameters and the learnable

logβ_tparameters simultaneously via backpropagation to minimizeL_total.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Gradient Conflict with the FetterGrad Algorithm

This protocol is based on the FetterGrad algorithm developed for the DeepDTAGen model to align gradients between distinct tasks [36].

- Forward Pass: Perform a standard forward pass through the shared network for a batch of data.

- Compute Task Losses: Calculate the individual loss for each task (e.g., DTA prediction and drug generation).

- Calculate Task Gradients: For each task

i, compute the gradient of its loss with respect to the shared parameters,g_i = ∇_θ L_i. - Minimize Gradient Distance: Introduce an additional regularization term to the total loss that minimizes the Euclidean Distance (ED) between the gradients of the tasks:

L_reg = ED(g_task1, g_task2). - Update Parameters: Update the shared model parameters by performing a gradient descent step on the combined loss:

L_total = L_task1 + L_task2 + λ * L_reg, whereλis a regularization hyperparameter.

Key Relationship and Workflow Diagrams

MTL Optimization with Gradient Alignment

Adaptive Task-Weighting Mechanism

Multi-View Molecular Representation

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools, datasets, and algorithms essential for implementing MTL in ADMET prediction.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [35] [37] | Benchmark Dataset | Provides curated ADMET datasets with standardized leaderboard-style train/test splits, enabling fair and rigorous comparison of MTL models. |

| Chemprop-RDKit Backbone [35] | Software/Model | A strong baseline model combining a Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) with RDKit molecular descriptors. Serves as a robust foundation for MTL extensions. |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors [35] | Molecular Feature | Enriches molecular representations with 3D electronic structure information (e.g., dipole moment, HOMO-LUMO gap), crucial for predicting metabolism and toxicity. |

| FetterGrad Algorithm [36] | Optimization Algorithm | Mitigates gradient conflicts in MTL by minimizing the Euclidean distance between task gradients, leading to more stable and efficient convergence. |

| Aligned Data Splits (Temporal/Scaffold) [37] | Data Protocol | Prevents cross-task data leakage and ensures realistic model validation by maintaining consistent compound partitions across all ADMET endpoints. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my computational model for CYP2B6/CYP2C8 inhibition perform poorly, and how can I improve it?

Answer: Poor performance for these specific isoforms is often due to limited dataset size, a common challenge as these isoforms have fewer experimentally tested compounds compared to others like CYP3A4 [40]. To improve your model:

- Employ Multi-task Learning (MTL): Train a single model to predict inhibition for multiple CYP isoforms simultaneously. MTL leverages shared information across related tasks (e.g., inhibition of CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4) to enhance generalization, especially for isoforms with smaller datasets [40].

- Utilize Data Imputation: Address the problem of missing inhibition data for compounds in your dataset. Multitask models incorporating data imputation have shown significant improvement in prediction accuracy for small datasets like CYP2B6 and CYP2C8 [40].

- Leverage Graph-Based Models: Use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) which naturally represent molecular structures and have emerged as powerful tools for modeling complex CYP enzyme interactions with improved precision [41].

FAQ 2: How can I assess my model's reliability for novel chemical compounds not seen during training?

Answer:

- Define the Applicability Domain: Systematically analyze the relationship between your training data and the new compounds. The model's reliability is higher for new compounds that are structurally similar to those it was trained on. Community initiatives like OpenADMET are generating datasets to help define and assess these applicability domains [10].

- Perform Scaffold-Based Splitting: During model validation, split your data so that entire molecular scaffolds (core structures) are held out in the test set. This tests the model's ability to generalize to truly novel chemotypes, rather than just to slight variations of training molecules [10].

- Quantify Prediction Uncertainty: Implement methods that estimate the confidence of each prediction. While many techniques exist, prospective testing on new, reliable data is needed to properly validate them [10].

FAQ 3: My experimental and computational results for CYP450 inhibition are inconsistent. What are the potential causes?

Answer: Inconsistencies can stem from several sources:

- Data Quality and Variability: The experimental data used to train the model may be inconsistent. IC50 values for the same compound can vary significantly between different laboratories due to differences in assay protocols, making it difficult for models to learn consistent patterns [10].

- Assay Drift and Reproducibility: Changes in experimental conditions over time (assay drift) can affect the quality of the data generated and used for validation [10].

- Model's Applicability Domain: The compound you are testing may fall outside the chemical space that the model was trained on, leading to unreliable predictions [41] [10].

FAQ 4: Are global models trained on large, public datasets better than models trained on my specific chemical series?

Answer: The debate between global and local models is ongoing. The optimal choice may depend on your specific goal:

- Global Models are trained on diverse chemical structures and are better at predicting properties for a wide range of novel compounds. They benefit from large, diverse datasets [10].

- Local (Series-Specific) Models are trained exclusively on compounds from a specific chemical series. They can be highly accurate for that series but may fail to generalize outside of it.

- Systematic comparisons using diverse datasets are needed to determine the best approach for a given scenario. It is often beneficial to test both strategies [10].