Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) Methods in Modern Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) methodologies, essential for predicting the in vivo performance of drug products based on in vitro data.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) Methods in Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) methodologies, essential for predicting the in vivo performance of drug products based on in vitro data. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles and regulatory definitions of IVIVC, delves into advanced methodological applications across diverse dosage forms, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex formulations, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing the latest advancements and practical insights, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to develop robust IVIVC models, thereby accelerating formulation development, reducing regulatory burden, and minimizing the need for extensive clinical studies.

Understanding IVIVC: Core Principles, Regulatory Standards, and Correlation Levels

In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) is a foundational scientific approach in modern pharmaceutical development, defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as "a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in vivo response" [1]. Typically, the in vitro property represents the rate or extent of drug dissolution or release, while the in vivo response reflects plasma drug concentration or the amount of drug absorbed [1]. This correlation serves as a critical bridge between laboratory measurements and clinical performance, enabling researchers to predict a drug's bioavailability and therapeutic effect based on dissolution data.

The regulatory significance of IVIVC is substantial, as recognized by health authorities worldwide. According to FDA guidance issued in September 1997, which remains the primary regulatory document on this topic, IVIVC provides comprehensive recommendations for developing documentation to support IVIVC for oral extended release (ER) drug products submitted in New Drug Applications (NDAs), Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs), or Antibiotic Drug Applications (AADAs) [2]. The establishment of a validated IVIVC offers multiple strategic advantages throughout the drug development lifecycle and regulatory review process, including serving as a surrogate for in vivo bioequivalence studies under specific conditions and supporting dissolution specification setting [2].

Levels of IVIVC: A Comparative Analysis

The FDA guidance formally recognizes multiple levels of IVIVC, each differing in complexity, predictive power, and regulatory utility. Understanding these categories is essential for selecting the appropriate correlation strategy for a specific drug development program.

Table: Comparative Analysis of IVIVC Levels

| Aspect | Level A | Level B | Level C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption | Statistical correlation using mean in vitro and mean in vivo parameters | Correlation between a single in vitro time point and one PK parameter |

| Predictive Value | High – predicts the full plasma concentration–time profile | Moderate – does not reflect individual PK curves | Low – does not predict the full PK profile |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Most preferred by FDA; supports biowaivers and major formulation changes | Less robust; usually requires additional in vivo data | Least rigorous; not sufficient for biowaivers or major formulation changes |

| Use Case | Requires ≥2 formulations with distinct release rates; supports biowaivers | Compares mean dissolution time with mean residence or absorption time | May support early development insights but requires supplementation for regulatory acceptance |

Table: Regulatory Application and Acceptance of IVIVC Levels

| IVIVC Level | Biowaiver Support | Formulation Change Evaluation | Dissolution Specification Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level A | Full support for major changes | Comprehensive evaluation capability | Primary basis for establishing clinically relevant specifications |

| Level B | Limited support, requires justification | Restricted application | Not typically used for specification setting |

| Level C | Generally not accepted for biowaivers | Limited utility for change evaluation | Insufficient for standalone specification setting |

| Multiple Level C | May support certain changes with validation | Moderate evaluation capability | Can support specification setting with comprehensive data |

Among these levels, Level A IVIVC represents the most precise and valuable category, establishing a point-to-point relationship between the entire in vitro dissolution profile and the entire in vivo absorption profile [3]. This level provides the highest predictive capability for the complete plasma concentration-time profile and is consequently the most preferred by regulatory agencies for supporting biowaivers and justifying formulation changes. Level A correlation typically requires data from at least two formulations with different release rates (e.g., slow, medium, and fast), though a single formulation may be acceptable under specific circumstances [3].

In contrast, Level B IVIVC utilizes statistical moment analysis, comparing the mean in vitro dissolution time to the mean in vivo residence time or mean in vivo absorption time [3] [4]. While this approach provides a useful statistical relationship, it does not reflect the actual shape of individual pharmacokinetic curves, limiting its predictive power and regulatory utility. Consequently, Level B correlations are significantly less common in regulatory submissions and are generally not suitable for establishing quality control specifications.

The Level C IVIVC establishes a single-point relationship, correlating one dissolution time point (e.g., t50%, t90%) with one pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., Cmax, AUC) [3] [4]. This represents the simplest form of correlation but offers the lowest predictive capability as it does not characterize the complete dissolution profile. While Level C correlations can provide valuable insights during early formulation development, they are insufficient as standalone evidence for regulatory decisions such as biowaivers. A variation known as Multiple Level C correlates multiple dissolution time points with one or more pharmacokinetic parameters, offering improved predictive capability and potentially supporting certain regulatory applications when Level A correlation cannot be achieved.

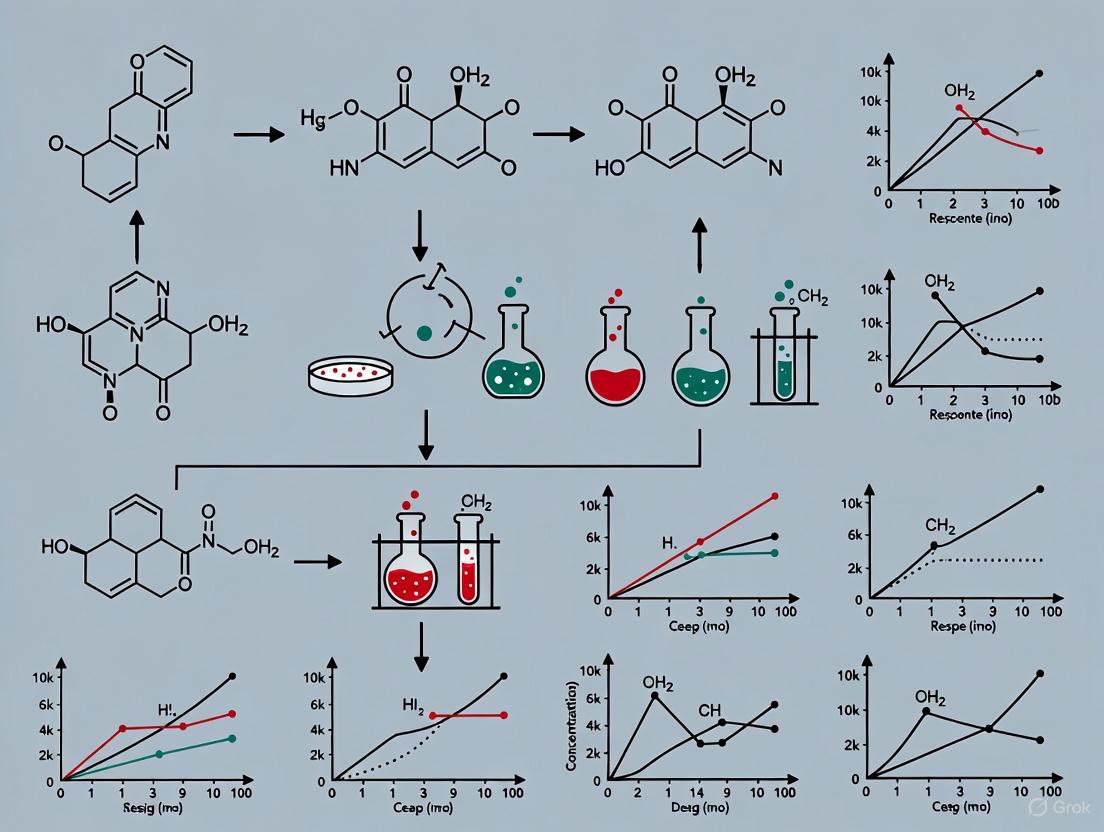

IVIVC Level Relationships and Data Flow

Experimental Protocols for IVIVC Development

Formulation Design and Development

The development of a robust IVIVC begins with careful formulation design. For a Level A IVIVC, which is most valuable for regulatory applications, a minimum of two formulations with different release rates (typically slow, medium, and fast) should be developed [3]. These formulations should differ meaningfully in their release characteristics to establish a meaningful correlation, typically varying by 10-20% in release rates. It is critical that these formulations maintain the same release mechanism while altering only the release rate through modifications in excipient composition, manufacturing process parameters, or structural characteristics. During this phase, researchers must carefully characterize critical quality attributes (CQAs) of each formulation, including drug content uniformity, particle size distribution, and morphological characteristics, as these factors may significantly influence both in vitro dissolution and in vivo performance.

For generic drug products, the formulation development process must also demonstrate pharmaceutical equivalence to the Reference Listed Drug (RLD) while creating meaningful variations in release rates for IVIVC development [1]. This often requires strategic formulation approaches that alter release characteristics without changing fundamental drug release mechanisms. Common techniques include modifying polymer concentrations in matrix systems, adjusting coating thickness in coated systems, or varying the ratio of immediate-release to extended-release components in multiparticulate systems.

In Vitro Dissolution Testing Methodologies

The selection and validation of appropriate in vitro dissolution methods are fundamental to establishing a meaningful IVIVC. The dissolution testing should employ conditions that discriminate between formulations with different release rates while maintaining biorelevance. According to regulatory standards, dissolution testing for IVIVC development should include a sufficient number of time points to adequately characterize the dissolution profile shape—typically a minimum of 5-6 time points for extended-release formulations [1].

Table: Standard Dissolution Apparatus and Media for Different Formulation Types

| Formulation Type | Apparatus | Dissolution Media | Testing Duration | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER Tablets | USP Apparatus I (Basket) or II (Paddle) | 0.1 N HCl, phosphate buffers (pH 6.8-7.4) | Until ≥80% release | Rotation speed (50-100 rpm), sink conditions |

| ER Capsules (Beads/Pellets) | USP Apparatus I (Basket) or II (Paddle) | Phosphate buffers (pH 6.5-7.5) | Until ≥80% release | Use of glass beads to prevent pellet floating |

| Enteric Coated Tablets | USP Apparatus II (Paddle) | 0.01 N HCl followed by phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 | 2 hours in acid, then buffer until ≥80% release | pH change methodology, enzyme addition |

| Lipid-Based Formulations | USP Apparatus II with lipolysis models | Biorelevant media with surfactants, lipolysis models | Variable based on formulation | Digestion kinetics, bile salt concentration |

For complex formulations such as lipid-based systems, traditional dissolution methods may be insufficient, and more sophisticated approaches are required. For lipid-based formulations (LBFs), additional characterization tools such as lipolysis assays and combined digestion-permeation models may be necessary to capture the complex interplay of digestion, solubilization, and permeation processes that influence in vivo performance [4]. Similarly, for long-acting injectable formulations based on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), flow-through cell apparatus and in vivo-mimicking environments have shown promise in improving prediction accuracy [5] [6].

The dissolution method must be properly validated for specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness according to regulatory standards. Additionally, the method should demonstrate discriminatory power by detecting meaningful differences in release rates between formulations while maintaining adequate reproducibility.

In Vivo Study Design and Data Collection

The clinical component of IVIVC development requires careful study design and execution. For oral dosage forms, a single-dose, crossover study design in healthy human volunteers is typically employed, with a sufficient washout period between treatments. The study should include frequent blood sampling to adequately characterize the absorption phase, peak concentration, and elimination phase of the plasma concentration-time profile—typically 12-18 time points for extended-release formulations.

Key pharmacokinetic parameters including AUC (area under the curve), Cmax (maximum concentration), and Tmax (time to reach Cmax) should be calculated for each formulation. The in vivo absorption or dissolution profile is then determined through mathematical deconvolution methods, which can be model-dependent (e.g., using Wagner-Nelson or Loo-Riegelman methods) or model-independent (numerical deconvolution) [6]. For IVIVC development, the fraction of drug absorbed is typically used as the in vivo response variable.

When designing in vivo studies for IVIVC, it is essential to consider factors such as food effects, circadian rhythms, and demographic characteristics of the study population that might influence drug absorption. The study should be conducted under well-controlled conditions with appropriate ethical approvals and informed consent procedures.

Model Development and Validation

The core of IVIVC establishment involves developing a mathematical relationship between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption data. For Level A correlation, this typically involves comparing the mean fraction dissolved in vitro to the mean fraction absorbed in vivo at corresponding time points. The most common approaches include:

- Time-Scaling Approach: Direct point-to-point correlation after appropriate time scaling

- Convolution-Based Approach: Using numerical deconvolution to estimate in vivo absorption

- Nonlinear Modeling: Applying nonlinear regression models when linear relationships are insufficient

Once a preliminary model is developed, its predictive performance must be rigorously validated. According to regulatory standards, an IVIVC model is considered predictive if the absolute prediction error for Cmax and AUC is ≤10% for each formulation, and the overall average prediction error is ≤15% [3] [1]. Internal validation (using the same data set) or external validation (using an independent data set) approaches may be employed, with external validation being more rigorous and persuasive for regulatory purposes.

For models intended to support biowaivers, validation should demonstrate accurate prediction of in vivo performance for formulations with different release rates within the design space. The model should also be evaluated for robustness through sensitivity analysis, assessing how variations in input parameters affect prediction accuracy.

Applications in Drug Development and Regulatory Submissions

Biowaiver Support and Regulatory Submissions

The application of IVIVC in regulatory submissions provides significant advantages for pharmaceutical sponsors. A validated IVIVC, particularly Level A correlation, can support biowaivers—regulatory exemptions from conducting additional in vivo bioequivalence studies—in several scenarios:

- For post-approval changes: When certain scale-up and post-approval changes (SUPAC) are made to formulation, manufacturing process, equipment, or manufacturing site [1]

- For multiple strengths: When requesting waivers for in vivo BE studies for lower or higher strengths that are not proportionally similar in composition to the bio-batch, provided all strengths are qualitatively the same, have the same release mechanism, and demonstrate similar in vitro dissolution profiles [1]

- For dissolution method and specification justification: When setting clinically relevant dissolution specifications [2]

The utility of IVIVC in regulatory submissions is evidenced by real-world application data. Between January 1996 and December 2014, FDA databases recorded 14 ANDA submissions for generic oral ER drug products containing IVIVC data [1]. These submissions utilized IVIVC for various purposes, including supporting changes in dissolution methods and specifications, level 3 site manufacturing changes, waivers for different strengths, and addressing batch-to-batch variations. However, it is noteworthy that only one ANDA submission included adequate IVIVC information enabling completion of bioequivalence review within the first review cycle, highlighting the challenges in developing regulatory-acceptable IVIVC models [1].

Formulation Optimization and Quality Control

Beyond regulatory applications, IVIVC serves as a powerful tool throughout the drug development lifecycle. During formulation development, IVIVC can guide optimization of critical formulation parameters such as excipient selection, particle size distribution, and coating techniques to ensure consistent bioavailability and desired performance characteristics [3]. By establishing a quantitative relationship between formulation variables and in vivo performance, IVIVC enables more efficient and targeted formulation development.

In the context of quality control, IVIVC provides a scientific basis for establishing clinically relevant dissolution specifications. Rather than setting specifications based solely on batch-to-batch consistency, IVIVC allows manufacturers to define dissolution limits that ensure bioequivalence across batches [1]. This approach enhances product quality and consistency while potentially reducing regulatory burdens through justification of wider specification ranges when supported by IVIVC data.

The integration of IVIVC with Quality by Design (QbD) principles further strengthens pharmaceutical development by linking critical quality attributes to clinical performance [3]. This systematic approach to development emphasizes understanding and control based on sound science and quality risk management, with IVIVC serving as a key tool for establishing clinically relevant specifications and design spaces.

Advanced Applications and Special Cases

IVIVC for Complex Dosage Forms

The application of IVIVC principles extends beyond conventional oral extended-release formulations to more complex drug delivery systems. For lipid-based formulations (LBFs), which are crucial for enhancing oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs, IVIVC development presents unique challenges due to complex processes involving digestion, solubilization, and permeation [4]. Traditional dissolution tests often fail to adequately predict in vivo performance for LBFs, necessitating more sophisticated in vitro models such as lipolysis assays and biorelevant media that better simulate gastrointestinal conditions.

For long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations, particularly those based on biodegradable polymers like poly(lactide-co-glycolide) or PLGA, IVIVC development is complicated by extended release durations (weeks to months) and complex release mechanisms involving polymer erosion and degradation [6]. The small number of FDA-approved LAI formulations (only 25 compared with thousands of oral extended-release formulations) reflects the difficulties in LAI development and characterization [6]. Recent advances in in vitro release testing methods, including flow-through apparatus and in vivo-mimicking environments, show promise for improving IVIVC for these challenging delivery systems [5].

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

The field of IVIVC continues to evolve with advancements in analytical technologies and computational methods. The integration of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling with IVIVC represents a promising approach for enhancing predictive capability, particularly for complex formulations [4] [7]. PBPK models incorporate physiological parameters such as organ perfusion rates, tissue distribution kinetics, and metabolic pathways to create more comprehensive and physiologically realistic simulations of drug behavior in humans.

Similarly, the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning approaches to IVIVC enables analysis of complex datasets to identify patterns and improve prediction accuracy [3]. These technologies can help overcome traditional limitations in IVIVC development by handling multidimensional data and nonlinear relationships that challenge conventional mathematical approaches.

Looking ahead, the convergence of advanced technologies such as microfluidics, organ-on-a-chip systems, and high-throughput screening assays holds immense potential for augmenting the predictive power and scope of IVIVC studies [3]. These technologies enable more sophisticated and biorelevant in vitro testing environments that better capture the complexity of in vivo conditions. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical industry is moving toward more personalized approaches to drug therapy, and IVIVC methodologies are expected to evolve to support the development of tailored formulations with optimized performance for specific patient populations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IVIVC Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in IVIVC Development | Application Examples | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Simulates gastrointestinal fluids to enhance predictive capability | Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FaSSIF), Fed State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FeSSIF) | Buffer capacity, surfactant composition, osmolarity matching physiological conditions |

| USP Dissolution Apparatus | Standardized equipment for in vitro release testing | USP Apparatus I (Basket), II (Paddle), IV (Flow-Through Cell) | Calibration, validation, mechanical specification compliance |

| Lipolysis Assay Components | Models lipid digestion processes for LBFs | Calcium chloride, taurocholate salts, pancreatic extracts | pH-stat control, titration calibration, enzyme activity standardization |

| PLGA Polymers | Biodegradable polymer for long-acting injectables | Various lactide:glycolide ratios, end-group modifications, molecular weights | Characterization of molecular weight, polydispersity, crystallinity |

| Permeability Enhancement Excipients | Improves drug absorption for BCS Class II/IV compounds | Surfactants, permeability enhancers, absorption modifiers | Cytotoxicity assessment, compatibility with absorption pathways |

| Deconvolution Software | Mathematical calculation of in vivo absorption profiles | Wagner-Nelson, Loo-Riegelman, numerical deconvolution methods | Algorithm validation, statistical weighting, model selection criteria |

| PBPK Modeling Platforms | Integrates physiological parameters with formulation performance | GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim | Population library adequacy, system parameter verification |

In vitro-in vivo correlation represents a powerful methodology that bridges pharmaceutical development and clinical performance, enabling more efficient and scientifically rigorous drug development. The regulatory framework established by FDA guidance, though primarily focused on oral extended-release dosage forms, provides a solid foundation for IVIVC development across various dosage forms and application scenarios. The different levels of IVIVC—A, B, and C—offer varying degrees of predictive capability and regulatory utility, with Level A providing the most comprehensive correlation for supporting critical development and regulatory decisions.

The successful development and application of IVIVC requires careful attention to formulation design, analytical method development, clinical study execution, and mathematical modeling. While challenges remain, particularly for complex dosage forms such as lipid-based systems and long-acting injectables, advances in biorelevant dissolution testing, computational modeling, and emerging technologies continue to expand the applications and predictive power of IVIVC approaches. As pharmaceutical sciences evolve toward more targeted and personalized therapies, IVIVC methodologies will continue to play an essential role in ensuring that in vitro performance reliably predicts in vivo behavior, ultimately supporting the development of safe, effective, and consistent drug products for patients.

In vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as "a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in vivo response" [8] [9]. In practice, the in vitro property is typically the rate or extent of drug dissolution or release, while the in vivo response is generally the plasma drug concentration or amount of drug absorbed [8] [4]. Since the FDA published its regulatory guidance on IVIVC for extended release (ER) oral dosage forms in 1997, the establishment and application of IVIVC has gained significant importance in the field of pharmaceutics [8].

A well-validated IVIVC model serves as a powerful tool in pharmaceutical development and regulation. Its primary advantage lies in its ability to predict in vivo performance based on in vitro dissolution data, which can reduce the need for costly and time-consuming bioequivalence studies involving human subjects [3] [10]. Furthermore, IVIVC enhances the understanding of a drug product's characteristics, facilitates the establishment of clinically relevant dissolution specifications, and supports regulatory decisions for both New Drug Applications (NDAs) and Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) [3] [10].

The IVIVC Hierarchy: Levels and Classifications

The IVIVC hierarchy is categorized into different levels based on the degree of correlation and predictive power. The U.S. FDA guidance recognizes several levels of correlation, with Level A representing the most informative category and Level D being the least informative [8]. The following sections provide a detailed examination of each correlation level.

Level A IVIVC: The Gold Standard

Level A IVIVC represents a point-to-point relationship between the in vitro dissolution rate and the in vivo input rate (e.g., the rate of drug absorption) [8] [3] [10]. It is considered the most informative and robust level of correlation and is the only type that can support a biowaiver (a regulatory waiver for in vivo bioequivalence studies) for certain post-approval changes [8] [3].

- Predictive Power: High; capable of predicting the entire plasma concentration-time profile [3].

- Regulatory Acceptance: Most preferred by regulatory agencies for supporting biowaivers for major formulation and manufacturing changes [3] [10].

- Development Requirements: Typically requires data from at least two or three formulations with different release rates (e.g., slow, medium, and fast) [8] [3].

The mathematical foundation of a Level A correlation often involves a two-step process employing deconvolution techniques to estimate the in vivo absorption time course, which is then directly compared to the in vitro dissolution profile [8] [10]. The relationship is generally linear, though non-linear correlations are also acceptable [8].

Level B IVIVC: Statistical Moments Analysis

Level B IVIVC utilizes the principles of statistical moment analysis. It compares the mean in vitro dissolution time (MDTin vitro) to either the mean in vivo residence time (MRTin vivo) or the mean in vivo dissolution time (MDTin vivo) [8] [10].

- Predictive Power: Moderate; does not reflect the actual shape of the plasma concentration-time curve [8] [3].

- Regulatory Acceptance: Less robust; generally not suitable for setting quality control specifications or for obtaining biowaivers [3].

- Key Limitation: While it uses all available in vitro and in vivo data, it is not a point-to-point correlation. Different in vivo profiles can result in the same mean time values, thus limiting its predictive capability [8].

Level C and Multiple Level C IVIVC: Single-Point and Multi-Point Relationships

Level C IVIVC establishes a single-point relationship, correlating one dissolution parameter (e.g., t50%, the time for 50% of the drug to dissolve) with one pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., Cmax, AUC) [8] [3].

- Predictive Power: Low; does not represent the complete shape of the plasma profile, which is critical for characterizing the in vivo performance of extended-release products [8].

- Utility: Primarily useful in the early stages of formulation development for screening pilot formulations [8] [3].

Multiple Level C IVIVC extends this concept by relating the amount of drug dissolved at several time points to one or more pharmacokinetic parameters [8]. It requires dissolution data from at least three time points covering the early, middle, and late stages of the dissolution profile [8].

- Predictive Power: Can be as useful as a Level A correlation if it effectively captures the entire dissolution profile [8].

- Regulatory Context: If a Multiple Level C correlation is achievable, then developing a Level A correlation is usually feasible and preferred [8].

Level D IVIVC: Qualitative Ranking

Level D IVIVC is a qualitative or rank-order correlation and is not considered a true correlation for regulatory purposes. It is not mentioned in the FDA IVIVC Guidance and serves only as a tool for early formulation development with no regulatory value [8] [4].

Comparative Analysis of IVIVC Levels

The table below provides a consolidated comparison of the key characteristics of Levels A, B, C, and Multiple Level C IVIVC.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of IVIVC Levels

| Aspect | Level A | Level B | Level C | Multiple Level C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption [8] [3]. | Correlation of mean in vitro dissolution time to mean in vivo residence or dissolution time [8]. | Single-point relationship between a dissolution parameter (e.g., t50%) and a PK parameter (e.g., Cmax, AUC) [8]. | Relationship between dissolution at several time points and one or more PK parameters [8]. |

| Predictive Value | High: Predicts the full plasma concentration-time profile [3]. | Moderate: Does not reflect the actual in vivo curve shape [8]. | Low: Cannot predict the full PK profile [8] [3]. | Moderate to High: If it captures the entire profile, can be as useful as Level A [8]. |

| Data Used | All data points from dissolution and absorption profiles [8]. | All data, but condensed into mean parameters [8]. | Single dissolution time point and a single PK parameter [8]. | Multiple dissolution time points and PK parameters [8]. |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Gold standard; can support biowaivers [8] [3]. | Limited; usually requires additional in vivo data [3]. | Low; not sufficient for biowaivers [3]. | May support biowaivers if it correlates all critical time points [8] [10]. |

| Primary Use Case | Surrogate for bioequivalence studies; setting dissolution specifications [3] [10]. | Formulation development tool [3]. | Early development screening [8] [3]. | Justifying dissolution specifications; early development [8] [10]. |

Figure 1: The IVIVC Hierarchy - This diagram illustrates the hierarchy of IVIVC levels, with Level A representing the highest predictive power and regulatory acceptance, descending to Level D, which is qualitative and has no regulatory value.

Methodological Workflow for IVIVC Development

Developing a robust IVIVC, particularly a Level A correlation, requires a systematic and multi-stage approach. The process involves mathematical manipulation to construct a functional relationship between in vitro dissolution (input) and in vivo dissolution or absorption (output) [9].

Key Experimental Protocols

The following workflow outlines the primary steps for establishing a Level A IVIVC, which is the most common type used in regulatory submissions [8] [10]:

- Formulation Selection: Develop and select at least two or three formulations with different release rates (e.g., slow, medium, and fast). The in vitro dissolution profiles should differ meaningfully, ideally by at least 10% at various time points [8] [10].

- In Vivo Data Generation: Obtain in vivo plasma concentration-time profiles for the selected formulations through clinical studies. An immediate-release (IR) formulation or an intravenous (IV) dose is often used as a reference [8] [10].

- Deconvolution Analysis: Estimate the in vivo absorption or dissolution time course from the plasma concentration data. This can be achieved using:

- Correlation Model Establishment: Plot the fraction of drug absorbed in vivo (obtained from deconvolution) against the fraction of drug dissolved in vitro for each formulation. Establish a mathematical relationship, which can be linear or non-linear (e.g., Sigmoid, Weibull, Higuchi) [8].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the predictability of the developed IVIVC model. This involves:

- Internal Validation: Using the data from which the model was built. The prediction error (%PE) for pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax and AUC) should be ≤10% on average to be considered acceptable [8] [10].

- External Validation: Predicting the in vivo performance of a new formulation not used in building the model [8].

Figure 2: Level A IVIVC Development Workflow - This diagram outlines the key experimental and mathematical steps involved in establishing a predictive Level A IVIVC model.

Critical Considerations and Potential Pitfalls

Successful IVIVC development requires careful consideration of several factors to avoid common traps:

- Use of Mean vs. Individual Data: Averaging in vivo plasma profiles can obscure individual variability, especially if there are significant differences in lag time (Tlag) or time to maximum concentration (Tmax) between subjects. IVIVC is discouraged for highly variable drugs as the inherent variability can mask formulation-dependent differences [11].

- Time Scaling and Lag Time Correction: Disparities between the timescales of in vitro and in vivo release may require the use of time-scaling factors to align the profiles for correlation development [8] [11].

- Flip-Flop Kinetics: In cases where the absorption rate is slower than the elimination rate (flip-flop kinetics), the apparent in vivo release profile estimated by deconvolution may be misleading if not properly accounted for [11].

- Biopharmaceutical and Physiological Factors: Drug properties such as solubility, permeability, and pKa, as well as physiological conditions like gastrointestinal pH and transit time, must be considered as they fundamentally influence both dissolution and absorption [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for IVIVC Studies

| Item / Method | Function in IVIVC Development |

|---|---|

| USP Apparatus I/II/III/IV | Standardized dissolution equipment to simulate various drug release conditions under controlled agitation and temperature [12]. |

| Biorelevant Media | Dissolution media (e.g., FaSSIF, FeSSIF) designed to mimic the composition, pH, and surface tension of human gastrointestinal fluids, improving the biopredictiveness of in vitro tests [4] [12]. |

| pH-Stat Titration | A technique used particularly for lipid-based formulations to monitor and control pH during in vitro lipolysis assays, simulating the digestion process in the gut [4]. |

| Deconvolution Software | Computational tools (e.g., Phoenix WinNonlin) for performing model-dependent or numerical deconvolution to estimate the in vivo input rate from plasma concentration data [8] [11]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic modeling platforms used to integrate in vitro dissolution data with physiological parameters for more accurate prediction of in vivo performance [3] [12]. |

The hierarchy of IVIVC provides a structured framework for correlating in vitro drug product performance with in vivo outcomes. Level A IVIVC stands as the most robust and regulatory-friendly correlation, offering a point-to-point predictive model that can reduce the need for additional clinical studies. While Level B and Level C correlations offer utility in early formulation development, their predictive power and regulatory acceptance are limited. The development of a successful IVIVC demands a meticulous methodological approach, accounting for formulation characteristics, physiological variables, and potential analytical pitfalls. As pharmaceutical scientists continue to face challenges with complex drug products, such as non-oral dosage forms and lipid-based systems, the principles of IVIVC remain a cornerstone of efficient, predictive, and patient-centric drug development [8] [4] [3].

In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) is a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form (typically the rate or extent of drug dissolution or release) and a relevant in vivo response (such as plasma drug concentration or amount of drug absorbed). [3] The establishment of a robust IVIVC plays a pivotal role in modern drug development by enhancing the understanding of dosage form performance, supporting regulatory submissions, and potentially reducing the need for certain clinical bioequivalence studies. [3] For researchers and drug development professionals, a successful IVIVC can expedite product development, optimize formulations, and establish clinically relevant dissolution specifications. However, the path to a successful IVIVC is governed by a complex interplay of physicochemical, biopharmaceutical, and physiological factors. Understanding and controlling these factors is critical, especially for complex drug products like nanomedicines and lipid-based formulations, where traditional correlation models often fall short. [13] [4] This guide provides a comparative analysis of these critical factors and the experimental protocols used to navigate them.

Comparative Analysis of Critical IVIVC Factors

The success of developing a predictive IVIVC model is highly dependent on a triad of factors related to the drug, the formulation, and the biological system. The table below summarizes these critical factors and their impact on IVIVC for different formulation types.

Table 1: Critical Factors Governing IVIVC Success Across Formulation Types

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Impact on IVIVC | Considerations for Conventional Oral Dosage Forms | Considerations for Complex Formulations (e.g., Nanomedicines, Lipid-Based Formulations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties | Drug Solubility & Permeability | Determines absorption mechanism and dissolution limitation. BCS Class II & IV drugs are more challenging. [4] | BCS Class I & III drugs often have more straightforward correlations. | For LBFs, dynamic solubilization supersedes equilibrium solubility. For nanomedicines, surface properties can alter permeability. [13] [4] |

| Particle Size & Crystalline Form | Directly influences dissolution rate. | Critical for immediate-release formulations of poorly soluble drugs. | For ASDs, maintaining the amorphous form is crucial to prevent precipitation and altered performance. [14] | |

| Biopharmaceutical & Formulation Factors | Formulation Design & Release Mechanism | Dictates the drug release profile, which must be mirrored by the in vitro method. [3] | Well-established for standard extended-release (ER) systems. | Highly complex for LBFs (digestion, micellization) and nanomedicines (nanoparticle-specific absorption pathways). Standard dissolution tests are often inadequate. [13] [4] |

| In Vitro Dissolution Method | Must be biorelevant and discriminate formulation changes. [14] | USP apparatus with standard buffers is often sufficient. | Requires sophisticated models (e.g., biphasic, lipolysis) to simulate GI environment. Method must be tailored to formulation. [14] [4] | |

| Physiological & Patient Factors | Gastrointestinal pH & Motility | Affects drug dissolution, solubility, and residence time. [4] | Can be simulated with pH-shift dissolution methods. | A major source of variability. Lipid digestion is pH-dependent and affects LBF performance. [4] |

| Variability in Anatomy & Physiology | Causes inter-subject variability in vivo that is hard to capture in vitro. [13] [4] | Population-based averages are typically used. | A significant hurdle for nanomedicines, leading to "highly deviating in-vitro and in-vivo data." [13] | |

| Food Effects (Fed/Fasted State) | Alters GI physiology, profoundly impacting solubility and absorption. | Commonly assessed in bioavailability studies. | Particularly critical for LBFs, as food intake stimulates bile secretion and lipid digestion, drastically altering formulation performance. [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Robust IVIVC Development

Level A IVIVC Development for Amorphous Solid Dispersions

A 2025 study on itraconazole immediate-release (IR) tablets provides a robust protocol for establishing a Level A IVIVC for a spray-dried solid dispersion (SDD) of a BCS Class II drug. [14]

- Objective: To develop an FDA level A IVIVC that predicts in vivo pharmacokinetic (PK) performance from in vitro dissolution for itraconazole SDD tablets, assessing the impact of polymer grade, disintegrant level, and dry granulation processing. [14]

- Formulation Design: Three tablet formulations with distinct release rates were developed: Fast-, Medium-, and Slow-release. This is a regulatory requirement for Level A IVIVC, as per FDA guidance. [14] [3]

- In Vitro Methodology:

- Apparatus: USP dissolution apparatus.

- Media: Simulated intestinal fluid (phosphate buffer, pH 6.4).

- Key Modification: To better mimic in vivo conditions, tablets were triturated into particles prior to immersion to attenuate disintegration differences observed between the Medium and Slow formulations in vivo. [14]

- In Vivo Study: A human pharmacokinetic study was conducted, comparing the test tablets against an oral solution used to define post-dissolution disposition. [14]

- IVIVC Modeling: A direct, differential-equation-based IVIVC model approach was employed. The model established a point-to-point correlation between the in vitro dissolution profile and the in vivo absorption profile. [14]

- Validation: The model met the FDA's internal predictability requirements for a Level A IVIVC, demonstrating its ability to accurately predict in vivo performance based on in vitro data. [14]

IVIVC Challenges and Protocols for Lipid-Based Formulations

Developing IVIVC for Lipid-based Formulations (LBFs) is particularly challenging due to their complex digestion and solubilization processes. The following protocol outlines a modern approach.

- Objective: To construct a predictive IVIVC for LBFs, which must account for dynamic processes like lipid digestion, micelle formation, and potential lymphatic transport, not captured by traditional tests. [4]

- In Vitro Toolbox:

- USP Dissolution: Often insufficient alone but used as a initial test.

- Lipolysis Assays: The primary tool for LBFs. This pH-stat model simulates the enzymatic digestion of lipids in the GI tract, measuring the rate of drug precipitation or incorporation into colloidal structures. [4]

- Combined Dissolution/Permeation Models: Biphasic systems (aqueous and organic solvent) or those incorporating membranes (e.g., PAMPA) can simultaneously assess drug release and partitioning, which is more biorelevant for absorption prediction. [4]

- In Silico Integration: Given the limitations of in vitro models, Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is increasingly integrated. PBPK models can incorporate data from lipolysis assays to simulate and predict human PK, helping to bridge the in vitro-in vivo gap. [4]

- Validation: Correlating in vitro lipolysis parameters (e.g., extent of precipitation) with in vivo pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC, C~max~) from animal or human studies. Success is mixed, with case studies on drugs like fenofibrate and cinnarizine showing only qualitative (Level D) or failed correlations, highlighting the need for model refinement. [4]

The workflow below illustrates the integrated experimental and modeling approach required for developing IVIVC for complex formulations.

Diagram 1: Integrated IVIVC Development Workflow for Complex Formulations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and instruments critical for executing the experimental protocols described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IVIVC Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application in IVIVC | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Spray-Dried Dispersion (SDD) | Enhances solubility and dissolution rate of poorly soluble drugs by creating an amorphous form. | Itraconazole SDD using polymers like HPMCAS was central to developing a Level A IVIVC. [14] |

| Lipid Excipients (Oils, Surfactants) | Core components of Lipid-Based Formulations (LBFs); solubilize drugs and promote absorption via digestion. | Classified into Types I-IV (e.g., triglycerides, mixed glycerides, surfactants). Critical for formulating SEDDS/SMEDDS. [4] |

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Simulate the composition, pH, and surface tension of human gastrointestinal fluids for predictive in vitro release. | Use of USP simulated intestinal fluid (phosphate buffer, pH 6.4) for itraconazole tablets. [14] Lipolysis assays use media containing bile salts and phospholipids. [4] |

| pH-Stat Titrator | Essential apparatus for in vitro lipolysis assays; monitors and maintains pH by titrating NaOH, quantifying fatty acids released from lipid digestion. | Used to evaluate the dynamic digestion of LBFs and its impact on drug precipitation. [4] |

| PBPK Modeling Software | In-silico platform that integrates physiological, drug, and formulation data to simulate and predict human pharmacokinetics. | Used to model subcutaneous injectables and inform IVIVC for complex delivery systems. [7] |

Establishing a successful IVIVC is a cornerstone of efficient and scientifically rigorous drug development. The journey is governed by a critical triad of factors: the physicochemical properties of the API, the biopharmaceutical design of the formulation, and the inherent physiological variability of the patient population. As demonstrated, the strategies and experimental protocols must be tailored to the formulation's complexity. While Level A IVIVC is achievable for solid dispersions with careful biorelevant method design, lipid-based formulations and nanomedicines present greater challenges, necessitating advanced in vitro tools like lipolysis assays and their integration with PBPK modeling. The absence of specific regulatory guidelines for novel nanomedicines further underscores the need for continued research and collaboration between industry and regulators. [13] For scientists, mastering these factors and leveraging the available toolkit is essential for bridging the gap between in vitro performance and in vivo efficacy, ultimately accelerating the delivery of robust and effective drug products to patients.

The Role of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) in IVIVC Development

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) serves as a fundamental scientific framework for streamlining drug development by categorizing active pharmaceutical ingredients based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability [15]. This classification provides a rational basis for predicting drug absorption and establishing in vitro-in vivo correlations (IVIVC), which are mathematical models relating the rate and extent of drug dissolution to its absorption profile in humans [16]. For regulatory bodies, the BCS guides decisions on biowaivers—approvals that exempt certain drug products from costly and time-consuming bioequivalence studies, particularly for BCS Class I and III compounds [17]. As the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing challenges with poorly soluble compounds, the strategic integration of BCS with IVIVC modeling has become indispensable for developing predictive dissolution methods, optimizing formulations, and ensuring product quality throughout the product lifecycle [12] [18].

The following sections explore how BCS classification directs IVIVC development strategies across different drug classes, with specific experimental case studies and methodological considerations for establishing robust correlations.

BCS Classification and Its Direct Impact on IVIVC Strategy

The BCS categorizes drug substances into four classes based on two key parameters: solubility, determined by the highest dose strength soluble in ≤250 mL of aqueous media across pH 1-7.5, and permeability, based on the extent of absorption ≥90% in humans [15] [18]. These properties directly influence the feasibility and approach for developing IVIVCs.

Table 1: BCS Classification and Corresponding IVIVC Considerations

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Rate-Limiting Step for Absorption | IVIVC Feasibility & Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Gastric emptying | Generally not necessary for biowaivers; IVIVC may be useful for modified-release formulations |

| Class II | Low | High | Dissolution rate | Excellent candidates for IVIVC; focus on developing biorelevant dissolution methods |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability rate | Challenging; permeation-limited absorption reduces correlation with dissolution |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Complex (both dissolution and permeability) | Most difficult; requires advanced formulation technologies |

For BCS Class II drugs, which exhibit dissolution rate-limited absorption, IVIVC is particularly advantageous [15]. The low solubility of these compounds means that in vivo dissolution becomes the slowest step in the absorption process, creating a direct mechanistic link between in vitro dissolution profiles and in vivo performance that can be quantitatively modeled [12]. This relationship enables formulators to use dissolution testing as a surrogate for bioequivalence studies, significantly accelerating development timelines for both new drug products and generics [19].

Experimental Approaches for Establishing IVIVC Across BCS Classes

Case Study: BCS Class II Drug – Lamotrigine Extended-Release Tablets

A recent study with lamotrigine, a BCS Class IIb weak base with pH-dependent solubility, demonstrated a systematic approach to IVIVC development for an extended-release formulation [12]. Researchers employed a Quality by Design (QbD) framework to establish patient-centric quality standards through these key experimental steps:

- Dissolution Method Development: Multiple dissolution apparatus (USP II and USP III) with both biorelevant media (fasted-state simulated intestinal fluid) and standard compendial media were evaluated to identify the most biopredictive conditions [12].

- In Vivo Data Collection: Clinical pharmacokinetic data were obtained from reference formulations to establish the in vivo absorption profile [12].

- IVIVC Model Building: A Level A correlation was developed by comparing in vitro dissolution data with in vivo absorption profiles derived through deconvolution [12].

- Predictability Validation: The IVIVC model was validated using internal and external validation sets, demonstrating its predictive capability for new formulations [12].

- PBPK Modeling Integration: A physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model combined with the validated IVIVC established clinically relevant dissolution specifications that accounted for inter-individual variability in patient physiology [12].

This integrated approach successfully established a predictive IVIVC that could support biowaiver considerations for post-approval changes and ensure consistent product quality without additional clinical studies [12].

Case Study: BCS Class II Drug – Bicalutamide Immediate-Release Tablets

For the poorly soluble BCS Class II drug bicalutamide, researchers employed a biphasic dissolution system to establish a predictive Level A IVIVC [19]. This innovative methodology addressed the limitations of traditional compendial methods:

- Apparatus: USP Apparatus II (paddle) modified with an organic phase [19]

- Aqueous Phase: 300 mL of pH 6.8 phosphate buffer [19]

- Organic Phase: 200 mL of 1-octanol (pre-saturated with buffer) [19]

- Sampling: Simultaneous collection from both phases at predetermined time points [19]

- Analytical: UV spectrophotometry at 272 nm (octanol) and 273 nm (buffer) [19]

The biphasic system provided an excellent correlation (r² = 0.98) between in vitro partitioning and in vivo absorption data [19]. By simultaneously measuring dissolution and partitioning, this method better simulated the in vivo absorption process, where drug molecules must first dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids before partitioning through the intestinal membrane. The resulting IVIVC successfully predicted the pharmacokinetic parameters of a generic product compared to the reference product, with AUC and Cmax ratios of 1.04 ± 0.01 and 0.951 ± 0.026, respectively, demonstrating its utility in generic product development [19].

Figure 1: Systematic Workflow for IVIVC Development of BCS Class II Drugs. This diagram illustrates the integrated in vitro and in vivo approach required to establish predictive IVIVC models, from initial method development through validation and regulatory applications.

Special Considerations: Advanced Formulations and Correlation Levels

For complex drug delivery systems such as lipid-based formulations (LBFs), establishing IVIVC presents additional challenges. LBFs, which are particularly valuable for enhancing the bioavailability of BCS Class II and IV drugs, involve dynamic processes including digestion, solubilization, and potential lymphatic transport that are not captured by traditional dissolution methods [4] [20]. The predictability of conventional in vitro tests for LBFs has been questionable, with studies showing that only approximately 50% of drugs tested using pH-stat lipolysis models correlated well with in vivo data [20].

Different levels of IVIVC provide varying degrees of predictive power and regulatory utility [4] [20]:

- Level A: Point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo input rate (most informative, regulatory preferred)

- Level B: Comparison of mean in vitro dissolution time and mean in vivo residence time

- Level C: Single point relationship (e.g., dissolution at one time point vs. AUC or Cmax)

- Multiple Level C: Relationships at several dissolution time points

- Level D: Qualitative ranking (lowest predictive value)

Table 2: Experimental Conditions for IVIVC Development from Case Studies

| Drug Product | BCS Class | Dissolution Apparatus | Dissolution Media | Analytical Method | Correlation Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamotrigine ER Tablets [12] | IIb | USP II (paddle) and USP III | Biorelevant (FaSSIF) and compendial buffers | HPLC | Level A |

| Bicalutamide IR Tablets [19] | II | Modified USP II with biphasic system | pH 6.8 phosphate buffer + 1-octanol | UV Spectrophotometry | Level A |

| Mesalazine Enteric-Coated Tablets [21] | Not specified | Reciprocating cylinder (USP Apparatus III) | pH progression (1.2, 4.5, 5.5, 6.0, 6.8) | UV Spectrophotometry | Not specified |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IVIVC Studies

The experimental protocols for establishing IVIVC require specific reagents, apparatus, and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key research solutions and their applications in IVIVC development based on the case studies examined:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IVIVC Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in IVIVC Studies | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Simulates gastrointestinal environment for predictive dissolution testing | Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FaSSIF) [12] |

| Biphasic Dissolution Systems | Simultaneously measures dissolution and partitioning kinetics | 1-octanol organic phase with aqueous buffer [19] |

| USP Dissolution Apparatus | Standardized equipment for dissolution testing | USP Apparatus II (paddle), USP III (reciprocating cylinder) [12] [21] |

| Chromatographic Reference Standards | Quantitative analysis of drug concentration | Lamotrigine USP reference standard [12] |

| Surfactants for Sink Conditions | Maintains sink conditions for poorly soluble drugs | Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) in dissolution media [19] |

| pH Adjustment Reagents | Modifies dissolution media to simulate GI pH progression | Hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, buffer salts [21] |

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System provides an essential framework for guiding IVIVC development, with BCS Class II drugs representing the most suitable candidates due to their dissolution rate-limited absorption. The integration of biopredictive dissolution methods with physiologically-based modeling enables the establishment of robust IVIVCs that can support regulatory decisions, including biowaivers for scale-up and post-approval changes. As pharmaceutical development increasingly focuses on poorly soluble compounds, the strategic application of BCS-based IVIVC approaches will continue to play a vital role in optimizing drug product quality while reducing the need for extensive clinical studies. Future directions include the development of more sophisticated in vitro models that better capture complex in vivo processes, particularly for advanced drug delivery systems such as lipid-based formulations and nanomedicines.

Advanced IVIVC Modeling Techniques and Applications Across Dosage Forms

In the realm of pharmaceutical development, In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) represents a critical predictive mathematical model that establishes a relationship between a biological property derived from a dosage form and a physicochemical property of the same formulation [16]. Specifically, a Level A IVIVC is the most stringent and informative category, providing a point-to-point correlation between the in vitro dissolution rate and the in vivo input rate of the drug product [4] [22]. This level of correlation is considered the gold standard for regulatory purposes as it allows for the prediction of in vivo bioavailability based on in vitro dissolution data, thereby reducing the need for extensive and costly human studies [14] [22].

The establishment of a Level A IVIVC is particularly valuable for supporting biowaivers, setting clinically relevant dissolution specifications, and optimizing formulations during development [4]. For poorly soluble drugs, including those formulated as lipid-based formulations (LBFs) and amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs), developing a robust Level A IVIVC presents unique challenges but offers significant rewards in predicting in vivo performance [4] [14]. This guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step methodology for establishing a Level A IVIVC, from initial deconvolution techniques to final model building and validation.

Fundamental Concepts and Regulatory Framework

Understanding IVIVC Levels

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) defines IVIVC as "the establishment of a rational relationship between a biological property, or a parameter derived from a biological property, produced by a dosage form and a physicochemical property or characteristic of the same dosage form" [4]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) further clarifies IVIVC as "a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in vivo response" [4]. Different levels of IVIVC provide varying degrees of predictive power and regulatory acceptance:

- Level A: Represents a point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption rate, representing the most predictive model that can serve as a surrogate for bioequivalence studies [4] [22].

- Level B: Utilizes the principles of statistical moment analysis, comparing mean in vitro dissolution time to mean in vivo residence time or mean in vitro dissolution time to mean in vivo dissolution time [4].

- Level C: Establishes a single-point relationship between a dissolution parameter (e.g., t50%) and a pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., AUC or Cmax) [4].

- Multiple Level C: Expands Level C correlation to multiple time points and pharmacokinetic parameters, offering improved predictability over single-point correlations [4].

Regulatory Significance and Applications

Regulatory agencies including the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) recognize validated Level A IVIVC models as sufficient for biowaiver applications, enabling formulation changes without additional clinical studies [22]. Furthermore, a properly validated Level A IVIVC allows for the establishment of clinically relevant dissolution specifications that ensure consistent product quality and performance throughout its lifecycle [4]. The credibility of an IVIVC model is determined through rigorous validation processes, including internal and external predictability assessments, which evaluate how well the model can predict in vivo performance from in vitro data [14].

Table 1: Comparison of IVIVC Levels and Their Characteristics

| IVIVC Level | Type of Correlation | Predictive Capability | Regulatory Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level A | Point-to-point relationship between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption rate | High - can predict entire plasma concentration profile | Biowaivers for formulation and process changes; setting dissolution specifications |

| Level B | Compares mean in vitro dissolution time to mean in vivo dissolution time | Moderate - uses statistical moments analysis | Limited regulatory utility; primarily for formulation development guidance |

| Level C | Single-point relationship between dissolution parameter and pharmacokinetic parameter | Low - relates only specific points | Supportive role in development; insufficient for biowaivers |

| Multiple Level C | Multiple point relationships between dissolution parameters and pharmacokinetic parameters | Moderate - improved predictability over Level C | May support biowaivers in certain cases with justification |

Step-by-Step Methodology for Level A IVIVC Development

Formulation Selection and Study Design

The initial phase in developing a Level A IVIVC involves careful formulation selection and study design. Researchers should develop at least three formulations with different release rates – typically fast, medium, and slow-releasing versions – to adequately characterize the relationship between in vitro dissolution and in vivo performance [14]. These formulations should exhibit significant differences in their dissolution profiles to establish a meaningful correlation. For immediate-release formulations of poorly soluble drugs, such as the itraconazole amorphous solid dispersion tablets studied successfully, this may involve varying the polymer grades, disintegrant levels, or employing different processing techniques like dry granulation [14].

For lipid-based formulations, which present unique challenges due to their complex digestion and solubilization processes, formulation selection should consider the Lipid Formulation Classification System (LFCS) [4]. Type I formulations consist purely of oils; Type II include oils and lipophilic surfactants; Type III incorporate oils, surfactants, and co-solvents; while Type IV contain only surfactants and co-solvents without traditional lipids [4]. Each type exhibits different behaviors in both in vitro tests and in vivo environments, necessitating tailored approaches to IVIVC development.

In Vitro Dissolution Method Development

Developing a biorelevant dissolution method is crucial for establishing a meaningful Level A IVIVC. The dissolution conditions should ideally reflect the gastrointestinal environment that the formulation will encounter in vivo. For conventional formulations, standard USP apparatus with appropriate media may suffice, but for more complex systems like LBFs and ASDs, more sophisticated approaches are necessary:

- For lipid-based formulations, incorporating lipolysis models that simulate intestinal digestion processes may be essential for predicting in vivo performance [4].

- For amorphous solid dispersions, methods such as triturating tablets into particles prior to dissolution testing may better mimic the attenuated disintegration that occurs in vivo [14].

- The use of biorelevant media simulating fasted or fed state intestinal fluids can significantly improve the predictability of dissolution tests [4].

Recent research on itraconazole ASDs employed USP simulated intestinal fluid (phosphate buffer) adjusted to pH 6.4, with tablets triturated into particles prior to immersion to better mimic in vivo disintegration patterns [14]. This attention to biopredictive methodology was crucial to their successful Level A IVIVC development.

In Vivo Data Collection and Study Protocols

Conducting well-designed pharmacokinetic studies in appropriate animal models or human subjects is essential for obtaining reliable in vivo data for IVIVC development. Key considerations include:

- Study Population: For human studies, typically 12-36 healthy adult volunteers are employed in crossover designs to minimize variability [14].

- Reference Formulation: Including an oral solution or rapidly dissolving formulation as a reference can help establish the "input function" for deconvolution [14].

- Sampling Strategy: Adequate blood sampling should be conducted to properly characterize the absorption phase – typically 12-18 samples over 24-72 hours depending on the drug's pharmacokinetics.

- Fed vs. Fasted State: For some formulations, particularly LBFs, evaluating both fasted and fed states may be necessary as food effects can significantly impact performance [4].

Table 2: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters for IVIVC Development

| Parameter | Description | Role in IVIVC |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax | Maximum observed plasma concentration | Reflects rate and extent of absorption |

| Tmax | Time to reach Cmax | Indicates absorption rate |

| AUC0-t | Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to last measurable time point | Measures total drug exposure |

| AUC0-∞ | Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to infinity | Represents complete drug exposure |

| Absorption Profile | Time course of drug absorption derived via deconvolution | Directly correlated with dissolution profile in Level A IVIVC |

Data Analysis Techniques: Deconvolution and Model Building

Deconvolution Methods

Deconvolution is the mathematical process used to determine the time course of drug absorption in vivo, which is then correlated with the in vitro dissolution profile. Two primary approaches are employed:

- Model-Dependent Methods: These techniques assume a specific pharmacokinetic model (e.g., one- or two-compartment models) and fit the observed plasma concentration data to derive the input function.

- Model-Independent Methods: Utilizing numerical deconvolution approaches, these methods do not assume a specific pharmacokinetic model and instead use a reference formulation (typically an oral solution or intravenous administration) to determine the input function.

For the itraconazole ASD Level A IVIVC, researchers employed a "direct, differential-equation-based IVIVC model approach, using an oral solution for post-dissolution disposition" with fast-, medium-, and slow-release tablets [14]. This model-dependent approach successfully met FDA internal predictability requirements for Level A IVIVC.

Correlation Model Development

Once the in vivo absorption time course has been derived via deconvolution, correlation models are developed to relate the fraction dissolved in vitro to the fraction absorbed in vivo. Common mathematical approaches include:

- Linear models: Simple proportional relationships between dissolved and absorbed fractions

- Non-linear models: Including polynomial, logarithmic, or Weibull functions that capture more complex relationships

- Direct differential equation models: As employed in the itraconazole ASD case study [14]

The mathematical relationship is typically expressed as: Fabs(t) = f(Fdiss(t)) where Fabs(t) is the fraction absorbed at time t and Fdiss(t) is the fraction dissolved at time t.

Figure 1: Level A IVIVC Development Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dissolution Testing Protocols for Different Formulation Types

Lipid-Based Formulations

For lipid-based formulations, traditional dissolution tests often fail to predict in vivo performance due to their inability to simulate lipid digestion processes. The pH-stat lipolysis model has emerged as a more biorelevant approach:

- Preparation of Digestion Medium: Create an intestinal digestion medium containing Tris buffer, bile salts, phospholipids, and calcium ions at physiologically relevant concentrations.

- Lipolysis Reaction: Add the lipid formulation to the medium and initiate digestion with pancreatic extract while maintaining pH stat titration.

- Sampling and Analysis: Collect samples at predetermined time points, immediately inhibit further lipolysis, and analyze for drug content in different phases (aqueous, pellet, oil).

- Data Interpretation: Calculate the percentage of drug in the aqueous phase (representing potentially absorbable drug) over time to generate the dissolution profile.

Studies have shown variable success with this approach – while Feeney et al. found that only half of the drugs studied using the pH-stat lipolysis device correlated well with in vivo data, it remains one of the most promising methods for LBFs [4].

Amorphous Solid Dispersions

For immediate-release ASDs, such as the itraconazole tablets successfully correlated:

- Media Selection: Use USP simulated intestinal fluid (phosphate buffer) adjusted to pH 6.4 to simulate intestinal conditions [14].

- Apparatus Selection: Standard USP Apparatus I or II with appropriate agitation speed (typically 50-75 rpm).

- Sample Preparation: For some formulations, triturating tablets into particles prior to dissolution may better mimic in vivo disintegration [14].

- Sampling and Analysis: Collect samples at appropriate time intervals (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes) and analyze for drug content.

- Sink Conditions: Maintain sink conditions where possible, though for poorly soluble drugs this may not be feasible.

Pharmacokinetic Study Protocols

Well-designed clinical or preclinical studies are essential for generating quality in vivo data:

- Study Design: Randomized crossover designs are preferred to minimize inter-subject variability.

- Dosing: Administer test formulations (fast, medium, slow release) and reference standard (solution or immediate-release formulation) with appropriate washout periods.

- Blood Sampling: Collect serial blood samples at strategic time points to adequately characterize the absorption phase – typically more frequent sampling during early time points.

- Bioanalytical Methods: Use validated analytical methods (LC-MS/MS typically) for quantitation of drug concentrations in plasma.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC) using non-compartmental analysis.

Figure 2: Level A IVIVC Correlation Model Concept

Case Study: Successful Level A IVIVC Implementation

A recent landmark study successfully established an FDA Level A IVIVC for amorphous solid dispersion-enabled itraconazole tablets, representing one of the few reported cases for immediate-release formulations [14]. This case provides a validated template for Level A IVIVC development:

Formulation Strategy and Experimental Design

Researchers developed three tablet formulations with distinct release rates – Fast, Medium, and Slow – containing itraconazole as a spray-dried dispersion [14]. The release rates were modulated through different grades of the same polymer, varying disintegrant levels, and employing dry granulation processing. This careful formulation design created the necessary dissolution rate variability essential for robust correlation development.

Biorelevant Dissolution Method Development

The dissolution method employed USP simulated intestinal fluid (phosphate buffer) at pH 6.4 [14]. Critically, to better mimic the attenuated disintegration that occurs in vivo, tablets were triturated into particles prior to their immersion into dissolution media, addressing a key challenge in establishing IVIVC for immediate-release formulations.

Pharmacokinetic Study and Data Analysis

The human pharmacokinetic study employed an oral solution as a reference for post-dissolution disposition, allowing for accurate determination of the absorption time course [14]. The direct, differential-equation-based IVIVC model approach successfully met all FDA internal predictability requirements for Level A IVIVC, demonstrating the robustness of their methodology.

Model Validation and Regulatory Compliance

The researchers conducted comprehensive credibility assessment of their FDA Level A IVIVC model, including model verification and validation considerations aligned with the question of interest, context of use, and model risk [14]. This rigorous approach highlights the importance of not just developing the correlation but thoroughly validating it against regulatory standards.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for IVIVC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in IVIVC |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Phosphate buffers, FaSSIF/FeSSIF, simulated gastric/intestinal fluids | Mimics gastrointestinal environment for predictive dissolution testing |

| Pancreatic Enzymes | Pancreatin with specified lipase/amylase/protease activity | Essential for lipolysis models evaluating lipid-based formulations |

| Synthetic Surfactants | SLS, Polysorbates, Cremophor types | Enhances solubility and maintains sink conditions in dissolution media |

| Pharmacokinetic Reference Standards | Certified reference materials with documented purity | Quantitation of drug concentrations in biological matrices |

| Chromatographic Columns | C18, phenyl, or other specialized stationary phases | Separation and analysis of drug in dissolution and biological samples |

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Challenges with Complex Formulations

Lipid-based formulations present particular challenges for IVIVC development due to their complex digestion, solubilization, and potential lymphatic transport [4]. Case studies highlight these difficulties – Do et al. found in vitro dispersion data failed to distinguish between LBFs administered in fasted or fed states in rats, while Larsen et al. observed precipitation during in vitro lipolysis that didn't correlate with in vivo performance [4]. These discrepancies emphasize the need for more sophisticated in vitro models that better simulate the dynamic in vivo environment.

Nanomedicines represent another challenge, as their absorption profile "varies widely with that of its conventional dosage forms mainly due to the physicochemical modifications and results in highly deviating in-vitro and in-vivo data" [13]. The unique properties of nanoparticles necessitate specialized approaches to IVIVC development that account for their distinct absorption mechanisms.

Model Validation and Acceptance Criteria

For regulatory acceptance of a Level A IVIVC, the FDA recommends specific validation criteria focusing on prediction errors:

- Internal Validation: The average absolute percent prediction error (%PE) for Cmax and AUC should be ≤10%, and the prediction error for individual formulations should not exceed 15% [14].

- External Validation: If applicable, the model should successfully predict the in vivo performance of additional formulations not used in model development.

- Context of Use Consideration: Model verification and validation should consider the specific question of interest and model risk [14].

The successful itraconazole Level A IVIVC met these FDA internal predictability requirements, providing a template for appropriate validation approaches [14].

Establishing a Level A IVIVC represents a significant achievement in pharmaceutical development, offering substantial benefits in reducing development costs, streamlining regulatory approvals, and ensuring product quality throughout its lifecycle. The step-by-step methodology outlined – from careful formulation design through biorelevant dissolution testing, robust pharmacokinetic studies, appropriate deconvolution techniques, and rigorous model validation – provides a roadmap for successful implementation.

Future advancements in IVIVC will likely come from improved in vitro tools that better simulate gastrointestinal physiology, particularly for challenging formulations like LBFs and nanomedicines [4]. Additionally, the integration of in silico modeling and machine learning approaches holds promise for enhancing IVIVC predictability, especially for drugs with complex absorption mechanisms [22]. As these methodologies evolve, the pharmaceutical industry can expect more efficient development pathways for even the most challenging drug molecules, ultimately accelerating patient access to important medicines.

In vitro–in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is a critical scientific approach in pharmaceutical development, establishing a predictive relationship between a drug product's in vitro dissolution and its in vivo pharmacokinetic behavior [3]. The primary goal is to create a mathematical model that can serve as a surrogate for in vivo studies, thereby streamlining development, optimizing formulations, and supporting regulatory decisions [4] [3]. For conventional immediate-release or extended-release dosage forms, established IVIVC methodologies are well-documented. However, complex formulations such as lipid-based drug delivery systems (LBDDS) present unique challenges due to their dynamic solubilization processes, interaction with digestive enzymes, and complex absorption pathways [4].