Beyond the Trial: A Strategic Framework to Improve RCT Generalizability for Real-World Impact

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to addressing the critical challenge of generalizing Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) findings to real-world populations.

Beyond the Trial: A Strategic Framework to Improve RCT Generalizability for Real-World Impact

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to addressing the critical challenge of generalizing Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) findings to real-world populations. It explores the foundational limitations of RCTs regarding external validity and contrasts them with the strengths of Real-World Evidence (RWE). The content delves into advanced methodological frameworks, including generalizability, transportability, and privacy-preserving data linkage, offering practical steps for application. It further tackles common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for dealing with biased or incomplete data and concludes with robust validation techniques and case studies that demonstrate how integrated evidence can successfully inform regulatory decisions and clinical practice.

The Generalizability Gap: Why RCT Findings Fail in the Real World

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on RCT Limitations

Q1: If RCTs are the 'gold standard,' why are their results often not applicable to my real-world patients?

RCTs are designed for high internal validity (confidence that the intervention caused the outcome) but often achieve this at the expense of external validity, or generalizability [1] [2]. This occurs due to:

- Highly Selected Populations: Restrictive eligibility criteria create a "trial population" that differs from the typical clinical population [3] [4]. For example, a study in Alberta showed almost 40% of patients in the province's cancer registry would be ineligible for a typical oncology trial [3].

- Artificial Settings: The highly protocolized nature of RCTs, with strict treatment regimens and intense monitoring, does not reflect real-world clinical practice [5] [3]. Results obtained under these "ideal circumstances" may not hold up in routine care.

Q2: What specific patient groups are most commonly excluded from RCTs, limiting generalizability?

RCTs frequently exclude patients with complex profiles commonly seen in practice. A study evaluating oncology trials found that real-world patients often have more heterogeneous and worse prognoses than RCT participants [4]. Key excluded groups often include:

- Patients with significant comorbidities (e.g., chronic kidney disease, heart failure) [1] [4].

- Patients with poor performance status or frailty [4].

- Patients from certain racial or socioeconomic backgrounds, which are often linked to prognosis [4].

Q3: Besides generalizability, what are other major inherent limitations of RCTs?

Table: Key Inherent Limitations of Randomized Controlled Trials

| Limitation | Brief Description | Impact on Research and Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment Challenges | Difficulty enrolling participants, especially in rare diseases or less common patient subgroups; can lead to underpowered or prematurely closed trials [5] [3]. | Slows down research; may lead to inconclusive results even for important clinical questions [5]. |

| High Cost & Complexity | Extensive infrastructure, monitoring, and long follow-up periods make RCTs expensive and complex to run [1] [6]. | Limits the number of questions that can be investigated; may not be feasible for all research inquiries [6]. |

| Ethical Constraints | It is not ethical to randomize patients for certain questions (e.g., harmful exposures like smoking) or when clinical consensus strongly favors one treatment [2]. | Leaves gaps in the evidence base that must be filled by other study designs. |

| Limited Safety Data | RCTs are often time-limited and not powered to assess rare or long-term adverse events [3]. | A complete safety profile of an intervention can only be understood with post-marketing real-world evidence [3]. |

Q4: How can Real-World Evidence (RWE) complement the evidence from RCTs?

Real-World Evidence (RWE), derived from data collected in routine clinical practice, provides essential complementary information [3]. Key strengths of RWE include:

- Assessing Effectiveness: Showing how a treatment performs in broader, unselected patient populations outside the ideal trial setting [3] [2].

- Identifying Rare or Long-Term Safety Outcomes: Utilizing data from larger populations over longer observation periods [3].

- Informing Use in Rare Cancers or Subgroups: Providing evidence when RCTs are not feasible due to small patient numbers [3].

Regulators like the FDA now recognize RWE as an important component of the evidence base for drug approvals [3].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common RCT Problems

Issue: Low Patient Recruitment in RCTs

Problem: The trial is failing to enroll enough participants, risking being underpowered or failing completely.

Solution:

- Action 1: Simplify Protocol & Data Collection. Use streamlined protocols that collect only data immediately relevant to prespecified endpoints. Consider a "large simple trial" design to reduce burden on sites and patients [1].

- Action 2: Broaden Eligibility Criteria. Re-evaluate exclusion criteria. A study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer found that common lab value exclusions did not significantly alter hazard ratios, suggesting some criteria could be safely relaxed [3] [4].

- Action 3: Leverage Electronic Health Records (EHRs). Use EHRs to identify and recruit eligible patients more efficiently and assess clinical outcomes with minimal patient contact [2].

Issue: RCT Results Lack Generalizability to Real-World Population

Problem: The trial was completed successfully, but the results do not seem to apply to the broader, more complex patient population in your clinic.

Solution:

- Action 1: Conduct a Trial Emulation Analysis. Emulate the RCT using real-world data to see how results translate. The

TrialTranslatorframework uses machine learning to stratify real-world patients by prognostic risk and then emulates the trial within these groups [4]. - Action 2: Use RWE with Advanced Causal Inference Methods. When RCTs are not possible, high-quality observational studies using causal inference methods (e.g., Directed Acyclic Graphs, propensity score weighting) can provide robust evidence on effectiveness in real-world populations [2].

- Action 3: Report Generalizability in RCT Publications. During trial registration and publication, transparently report sampling methods and the use of any sample correction procedures to improve the assessment of generalizability [7].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Machine Learning Framework for Assessing RCT Generalizability (TrialTranslator)

This protocol, based on a study published in Nature Medicine, details a method to systematically evaluate how well the results of an oncology RCT apply to different risk groups of real-world patients [4].

1. Objective: To assess the generalizability of a phase 3 oncology RCT result to real-world patients by emulating the trial within machine learning-identified prognostic phenotypes.

2. Materials and Reagents Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Trial Emulation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Nationwide EHR-derived Database (e.g., Flatiron Health) | Provides longitudinal, real-world patient data on demographics, treatments, and outcomes for analysis [4]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Platform for data processing, machine learning model development, and survival analysis. |

| Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) Survival Model | The top-performing ML model used to predict patient mortality risk from the time of metastatic diagnosis [4]. |

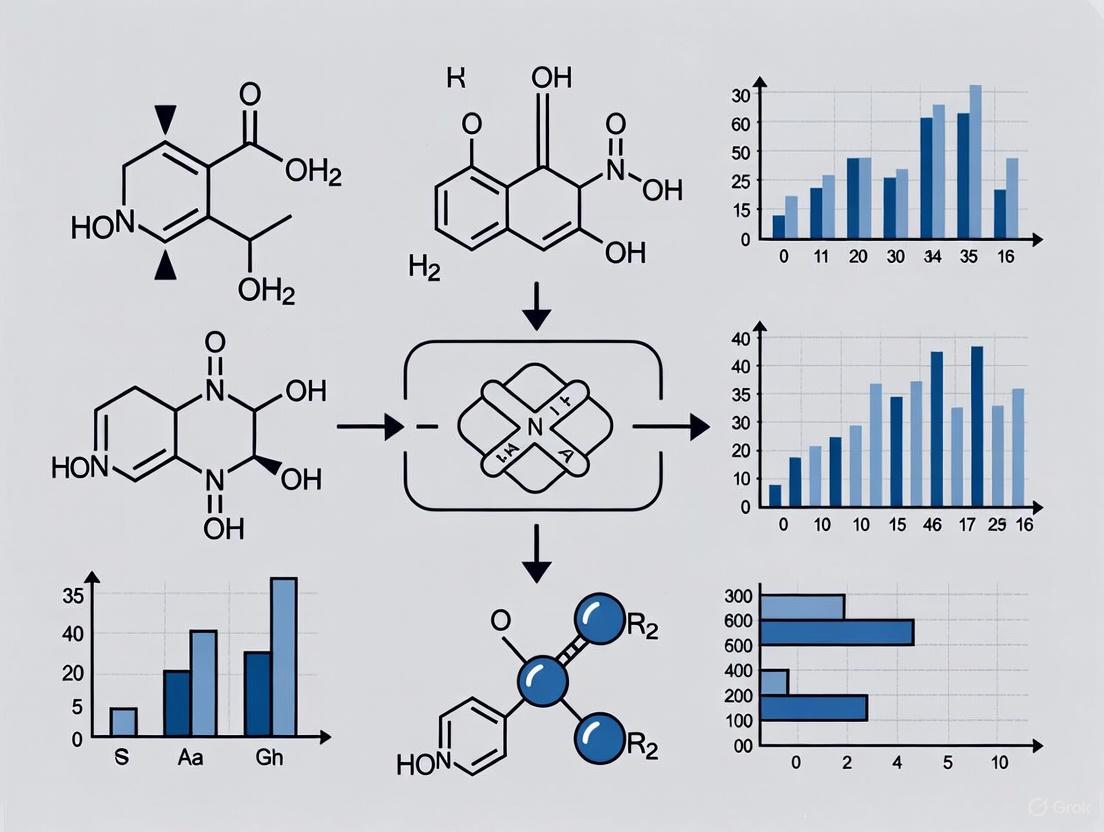

3. Workflow Diagram

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

Step I: Prognostic Model Development

- Develop cancer-specific prognostic models using real-world data to predict patient mortality risk from the time of metastatic diagnosis. Models can include Gradient Boosting Survival Model (GBM), Random Survival Forest, and penalized Cox models [4].

- Select the top-performing model based on the time-dependent Area Under the Curve (AUC) for 1-year or 2-year overall survival. In the referenced study, the GBM consistently demonstrated superior performance [4].

- Use the selected model to calculate a mortality risk score for each patient in the database.

Step II: Trial Emulation

- Eligibility Matching: Identify real-world patients in the EHR database who received either the treatment or control regimens from the landmark RCT and who meet the RCT's key eligibility criteria (e.g., correct cancer type, line of therapy, biomarker status) [4].

- Prognostic Phenotyping: Using the mortality risk scores from Step I, stratify the eligible patients into three prognostic phenotypes: Low-risk (bottom tertile), Medium-risk (middle tertile), and High-risk (top tertile) [4].

- Survival Analysis:

- Apply Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) within each phenotype to balance features (e.g., age, performance status, biomarkers) between the treatment and control arms [4].

- For each phenotype, estimate the treatment effect by calculating Restricted Mean Survival Time (RMST) and median Overall Survival (mOS) from the IPTW-adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves [4].

- Compare these real-world estimates to the results reported in the original RCT to identify for which patient phenotypes the trial results are generalizable.

5. Expected Output: The analysis typically reveals that low and medium-risk real-world patients have survival times and treatment benefits similar to the RCT, while high-risk patients show significantly lower survival and diminished treatment benefit, highlighting the limited generalizability of the RCT to this subgroup [4].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the practical impact of restrictive eligibility criteria on my research? Restrictive criteria can significantly limit the applicability of your findings. A systematic review of high-impact trials found that over 70% excluded pediatric populations, 38.5% excluded older adults, 54.1% excluded individuals on commonly prescribed medications, and 39.2% excluded based on conditions related to female sex [8]. This creates a population that differs fundamentally from real-world patients, potentially making your results less relevant to clinical practice.

Q2: How can I quantitatively assess how well my study population represents the real world? You can implement a Benchmarking Controlled Trial methodology. This involves using electronic health records (EHR) to create two cohorts: an "Indication Only" cohort (all patients with the target condition) and an "Indication + Eligibility Criteria" cohort (those who would qualify for your trial). Compare baseline characteristics between these cohorts and your actual trial population to identify significant differences in disease severity, comorbidities, demographics, and clinical metrics [9].

Q3: What are the most common but problematic exclusion criteria I should avoid? The most frequently problematic exclusions involve age (particularly children and elderly), patients with common comorbidities, those taking concomitant medications, and women (especially regarding reproductive status) [8]. Industry-sponsored trials and drug intervention studies are particularly prone to extensive exclusions related to comorbidities and concomitant medications, which are often poorly justified [8].

Q4: How does the trial setting itself affect generalizability? The healthcare setting significantly impacts results. For example, one analysis found national differences in how quickly patients were investigated resulted in dramatically different treatment effects for the same intervention [10]. Center selection bias also matters—when only high-performing centers with excellent safety records participate, the results may not replicate in typical clinical settings with higher complication rates [10].

Q5: What reporting standards should I follow to enhance transparency about generalizability? Adhere to the CONSORT 2025 Statement, which provides updated guidelines for reporting randomized trials [11]. For protocols, use the SPIRIT 2025 Statement, which includes 34 items addressing trial design, conduct, and analysis [12]. Both emphasize transparent reporting of eligibility criteria, participant flow, and settings to help users assess applicability to their populations.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Significant Differences Between RCT and Real-World Populations

Symptoms: Your trial results show better outcomes than observed in clinical practice, or subgroup analyses reveal different treatment effects in specific patient groups.

Diagnosis: Eligibility criteria have created a study population that doesn't represent real-world patients in terms of disease severity, comorbidities, age, or other relevant characteristics [9].

Solution: Implement population benchmarking before trial initiation:

- Extract EHR data from potential recruitment sites for your target condition

- Apply your eligibility criteria to create a synthetic trial-eligible cohort

- Compare characteristics between the real-world population and trial-eligible cohort

- Identify over-excluded groups and consider modifying criteria that unnecessarily restrict enrollment of clinically relevant subpopulations [9]

Problem: Selection Bias in Cluster-Randomized Trials

Symptoms: Differential consent rates between intervention and control groups, or baseline imbalances in important prognostic factors.

Diagnosis: When clusters (e.g., clinics, hospitals) are randomized before participant recruitment, and both recruiters and potential participants know the allocation, selection bias can occur [13].

Solution: Mitigate through design and analysis:

- Use blinded recruiters whenever possible

- Document screening and refusal patterns by arm

- Compare characteristics of consenters vs. refusers within each arm

- Use statistical methods to adjust for random cluster variation in consent patterns [13]

- Consider covariate-constrained randomization to balance important prognostic factors across arms

Problem: Poor Transportability of Treatment Effects

Symptoms: Your rigorously conducted trial shows significant benefits, but real-world applications yield diminished effects or different safety profiles.

Diagnosis: Heterogeneity of treatment effect (HTE) exists, where factors beyond the intervention itself (age, comorbidities, adherence patterns) modify the measured effect [9] [14].

Solution: Enhance applicability through better characterization:

- Document what actually happened in the trial beyond the protocol (actual adherence, co-interventions, patient characteristics) [15]

- Report probabilities for both favorable and adverse outcomes

- Use statistical methods like propensity scores to quantify differences between trial participants and target populations [15]

- Consider pragmatic trial elements that mimic real-world conditions when appropriate [2]

Evidence Tables

Table 1: Frequency of Common Exclusion Criteria in High-Impact Journal RCTs

| Exclusion Category | Percentage of Trials | Examples | Justification Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-based | 72.1% | Children (60.1%), Older adults (38.5%) | Mixed |

| Concomitant Medications | 54.1% | Common prescription drugs | Often poorly justified |

| Medical Comorbidities | 81.3% | Renal impairment, liver disease, cardiovascular conditions | Only 47.2% strongly justified |

| Sex-related | 39.2% | Pregnancy potential, reproductive status | Variable |

| Reporting Issues | 12.0% | Criteria not clearly reported | N/A |

Data from systematic sampling review of RCTs in high-impact general medical journals (1994-2006) [8]

Table 2: Documented Population Differences Between RCTs and Real-World Cohorts

| Trial Example | Key Population Differences | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Sitagliptin vs. Glimepiride (T2DM) | RCT patients had longer diabetes duration (8.69 vs 3.30 years) and higher fasting glucose (169.04 vs 141.55) | Trial population had more advanced disease [9] |

| PROVE-IT (ACS) | RCT patients had more adverse lipid profiles and higher cardiovascular risk | More severe baseline state may exaggerate absolute benefit [9] |

| RENAAL (Diabetic Nephropathy) | RCT patients had higher rates of complications (amputation: 8.86% vs 1.60%) | Advanced disease progression in trial population [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Population Representativeness Assessment

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate how well your study population represents the target real-world population.

Materials:

- Electronic Health Record system with data extraction capabilities

- Statistical software (R, Python, or SAS)

- Pre-specified eligibility criteria list

Procedure:

- Define index cohort: Extract all patients with the target medical condition from EHR data

- Apply eligibility criteria: Programmatically apply each inclusion/exclusion criterion to create trial-eligible cohort

- Characterize populations: Calculate baseline characteristics for:

- Entire indication cohort

- Trial-eligible cohort

- Actual trial participants (if available)

- Statistical comparison: Use appropriate tests (t-tests, chi-square) to compare:

- Indication cohort vs. trial-eligible cohort

- Trial-eligible cohort vs. actual trial participants

- Effect size calculation: Compute standardized differences for key prognostic variables

- Sensitivity analysis: Test impact of modifying most restrictive criteria [9]

Output Interpretation:

- Standardized differences >0.1 indicate meaningful imbalance

- Significant p-values (<0.05) suggest important differences between populations

- Variables with large imbalances may be effect modifiers

Protocol 2: Generalizability Framework Application

Purpose: To systematically assess and document applicability of trial findings.

Materials:

- CONSORT 2025 checklist [11]

- Applicability assessment framework [15]

- Target population characterization data

Procedure:

- Document RCT context using the TIDieR framework:

- Brief name: Why, What, Who provided

- Procedures: How, Where, When and How much

- Tailoring: Modifications, How well (actual adherence) [11]

- Characterize both populations:

- RCT population: Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, disease severity

- Target population: Same variables from real-world data sources

- Assess effect modifiers:

- Identify potential treatment effect modifiers from literature

- Compare distribution of modifiers between RCT and target populations

- Apply transportability methods if appropriate:

- Use propensity score methods to weight RCT population to target population [15]

- Apply meta-analytic approaches to assess heterogeneity

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Generalizability Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Record Data | Provides real-world population characteristics | Benchmarking study populations against clinical practice [9] |

| CONSORT 2025 Checklist | Ensures transparent reporting of trial methods and findings | All randomized trials; improves assessment of external validity [11] |

| SPIRIT 2025 Guidelines | Guides comprehensive protocol development | Trial planning phase; ensures addressing of applicability issues [12] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Quantifies differences between trial participants and target populations | Transportability analysis; generalizability assessment [15] |

| Heterogeneity of Treatment Effect (HTE) Analysis | Identifies variation in treatment effects across subgroups | Both design and analysis phases; informs personalized medicine [9] |

Process Visualization

Eligibility Criteria Create Applicability Gap

This diagram illustrates how restrictive eligibility criteria filter the broad real-world population into a more homogeneous study group, creating a gap between the population in which treatments are tested and the population in which they are ultimately applied.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are RWD and RWE?

- Real-World Data (RWD) is data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources [16].

- Real-World Evidence (RWE) is the clinical evidence regarding the usage and potential benefits or risks of a medical product derived from the analysis of RWD [16].

How does evidence from RWE differ from that Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)? RWE and RCT evidence are complementary. The table below summarizes their key differences [16] [17]:

| Aspect | RCT Evidence | Real-World Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Demonstrate efficacy under ideal, controlled settings | Demonstrate effectiveness in routine care |

| Focus | Investigator-centric | Patient-centric |

| Setting | Experimental | Real-world |

| Population | Homogeneous, selected via strict criteria | Heterogeneous, reflects typical patients |

| Treatment Protocol | Prespecified and fixed | Variable, at physician’s and patient’s discretion |

| Comparator | Placebo/standard practice per protocol | Usual care or alternative therapies as chosen in practice |

| Patient Monitoring | Rigorous, continuous, and scheduled | Variable, as per usual clinical practice |

| Data Collection | Structured case report forms | Routine clinical records (e.g., EHRs, claims) |

Why is RWE needed if RCTs are the 'gold standard'? While RCTs offer high internal validity by controlling variables to establish causal effects, their strict inclusion criteria create an "idealized" patient population that often does not represent the broader, more diverse patients treated in actual clinical practice [16] [17]. RWE provides greater external validity, showing how a drug performs in real-world patients, including the elderly, those with comorbidities, and other groups often excluded from RCTs [16] [7]. It helps answer questions about long-term safety, effectiveness, and usage patterns that RCTs are not designed to address [16] [18].

Is RWE recognized by regulatory bodies like the FDA? Yes, major regulatory bodies formally recognize and have developed frameworks for the use of RWE. In the US, the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) mandated the FDA to develop a program for evaluating RWE for regulatory decisions [17] [19]. The FDA has since released a specific RWE Framework and multiple guidance documents [17]. Similarly, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and other international agencies are actively integrating RWE into their decision-making processes [17] [19].

For what regulatory purposes has RWE been used successfully? RWE has supported numerous regulatory decisions, including new drug approvals, label expansions, and safety monitoring. The following table provides concrete examples from the FDA [20]:

| Drug (Product) | Regulatory Action Date | Summary of RWE Use |

|---|---|---|

| Aurlumyn (Iloprost) | Feb 2024 | A retrospective cohort study using medical records served as confirmatory evidence for efficacy in treating severe frostbite [20]. |

| Vimpat (Lacosamide) | Apr 2023 | Safety data from the PEDSnet network supported a new pediatric loading dose regimen [20]. |

| Vijoice (Alpelisib) | Apr 2022 | Approval was based on a single-arm study using data from an expanded access program, with medical records providing evidence of effectiveness [20]. |

| Orencia (Abatacept) | Dec 2021 | A non-interventional study using a transplant registry (CIBMTR) served as pivotal evidence for a new indication [20]. |

| Prolia (Denosumab) | Jan 2024 | An FDA study of Medicare claims data identified a risk of severe hypocalcemia, leading to a Boxed Warning update [20]. |

Troubleshooting Common RWE Challenges

This section addresses specific methodological issues you might encounter when designing RWE studies intended for regulatory submission.

Challenge 1: How do I mitigate bias from missing or incomplete data in EHRs?

- Problem: Real-world data from sources like Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are often collected inconsistently, leading to missing information on critical baseline characteristics (e.g., prior treatments, tumor stage, ECOG scores). This can introduce confounding bias and make it difficult to establish comparability between study cohorts [21].

- Solution:

- Proactive Data Source Assessment: Before finalizing your study design, assess the candidate RWD source for completeness and quality. Prioritize data sources where key clinical variables are well-documented [21].

- Inclusion of Unstructured Data: Supplement structured data fields by extracting information from unstructured sources, such as clinician notes and radiology reports, using natural language processing (NLP) where feasible [21] [17]. In the successful application for Ibrance, the submission included such unstructured source data [21].

- Pre-specify Handling Methods: Clearly outline in your statistical analysis plan (SAP) how you will handle missing data (e.g., through multiple imputation or other appropriate methods) [21].

Challenge 2: My RWE study has a small or non-random sample. How can I improve its generalizability?

- Problem: Small sample sizes, common in rare disease or oncology studies, limit statistical power and the ability to draw strong conclusions. Furthermore, non-random sampling can lead to selection bias, reducing the external validity of your findings [21] [7].

- Solution:

- Data Linkage: Combine data from multiple sources (e.g., linking a registry with claims data) to increase the sample size and capture more patient characteristics. Be aware that this can introduce data heterogeneity that must be managed [21].

- Sample Correction Procedures: To improve generalizability from a non-random sample, employ statistical techniques such as weighting (e.g., using propensity scores) or raking to align your study sample with the known characteristics of the target population [7]. A 2024 study noted that while the use of these procedures is increasing, it remains low, indicating an area where rigorous studies can stand out [7].

Challenge 3: What are the common pitfalls in using RWE for regulatory submissions, and how can I avoid them?

- Problem: Regulatory submissions that incorporate RWE are often challenged on both procedural and methodological grounds [21].

- Solution: Adhere to the following best practices:

- Avoid: Failing to Share a Pre-specified Protocol and SAP. The FDA emphasizes transparency to guard against "p-hacking" or data dredging [21].

- Fix: Engage Early with Regulators. Provide draft versions of your study protocol and statistical analysis plan to the agency for review and comment before finalizing them and conducting the analyses [21].

- Avoid: Using Subjective Endpoints. Outcomes that rely on physician judgment (e.g., tumor response rates) can be difficult to capture uniformly from RWD [21].

- Fix: Use Objective Endpoints. Whenever possible, design your study around endpoints with well-defined, objective diagnostic criteria, such as overall survival, stroke, or myocardial infarction, which are more reliably captured in RWD [21].

- Avoid: Inadequate Justification of Data Quality. Simply having RWD is not enough; you must prove it is fit for purpose.

- Avoid: Failing to Share a Pre-specified Protocol and SAP. The FDA emphasizes transparency to guard against "p-hacking" or data dredging [21].

Experimental Protocol: Designing a Regulatory-Grade RWE Study

The following workflow outlines the key stages for designing a robust RWE study intended to support a regulatory decision.

Protocol Title: Design and Execution of a Regulatory-Grade RWE Study Using a Retrospective Cohort Design.

Objective: To generate robust RWE on the comparative effectiveness or safety of a medical product using routinely collected healthcare data, with the goal of supporting a regulatory submission.

Methodology Details:

- Step 1: Identify & Assess RWD Source(s): Select the most appropriate source (e.g., EHR, claims, disease registry) based on the study question. Critically assess data quality, completeness, and provenance. For multi-source studies, demonstrate how data can be integrated and harmonized using a common data model [21] [17].

- Step 2: Develop Pre-specified Study Protocol & SAP: Before any analysis, document the entire study design in a detailed protocol. This must include the study population definition (including all inclusion/exclusion criteria), exposure and outcome definitions (with validated coding algorithms), statistical分析方法, and plans for handling missing data and confounding [21]. This guards against bias from re-running analyses until a desired result is found.

- Step 3: Engage with Regulators for Early Feedback: A critical and often overlooked step. Share the draft protocol and SAP with the relevant regulatory agency (e.g., FDA, EMA) to get feedback and alignment on the proposed approach before finalizing the study [21].

- Step 4: Execute Analysis Plan & Address Biases: Conduct the analysis exactly as pre-specified. Use appropriate causal inference methods like propensity score matching/weighting to control for measured confounding. Perform comprehensive sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the findings to various assumptions [21] [17].

- Step 5: Prepare Submission Package with Transparency: Compile the final submission, including the final protocol, SAP, complete results, and a clear account of any deviations from the planned analysis. Transparency is key to building regulatory confidence [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RWE Generation

This table lists key "reagents" — in this case, data sources, methodological approaches, and tools — essential for conducting high-quality RWE research.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Provide detailed clinical data from routine practice, including diagnoses, procedures, lab results, and physician notes [16] [17]. |

| Claims & Billing Data | Track healthcare utilization, medication fills, and coded diagnoses/procedures for large populations over time [16] [17]. |

| Disease & Product Registries | Offer longitudinal, structured data on patients with specific conditions or treatments, often including patient-reported outcomes [16] [17]. |

| Common Data Models (CDMs) | Standardize data from different sources into a consistent format, enabling large-scale, reproducible analysis across networks (e.g., OHDSI/OMOP, FDA Sentinel) [16] [17]. |

| Propensity Score Methods | A statistical technique to reduce confounding bias in observational studies by creating a balanced comparison cohort [21] [17]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Extracts structured information from unstructured clinical text (e.g., pathology reports, doctor's notes) to enrich RWD [17]. |

| RWE Assessment Tools (e.g., ESMO-GROW) | Provide structured checklists and frameworks to guide the planning, reporting, and critical appraisal of RWE studies, improving rigor and transparency [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary methodological gap that limits the generalizability of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)?

RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating new interventions due to their high internal validity achieved through randomization. However, they often have extensive inclusion and exclusion criteria that systematically exclude patients with poorer functional status or significant comorbidities. This creates a fundamental gap, as these excluded patients are routinely treated in real-world practice, raising concerns about whether RCT findings translate to broader patient populations [22].

Q2: How can Real-World Evidence (RWE) help bridge this generalizability gap?

Real-World Evidence directly addresses the generalizability limitation of RCTs. Because RWE is generated as a byproduct of healthcare delivery, it reflects the outcomes of interventions in the actual, diverse patient population that receives treatment in routine practice. This provides critical data on treatment effectiveness in patient groups typically underrepresented in clinical trials, such as those with poorer performance status or other comorbidities [22] [23].

Q3: What are the key strengths and limitations of using Real-World Data (RWD) for research?

The table below summarizes the core strengths and limitations of Real-World Evidence:

| Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|

| Assessment of generalizability of RCT findings [22] | Poorer internal validity compared to RCTs [22] |

| Long-term surveillance of outcomes [22] | Inability to adequately adjust for all confounding factors [22] |

| Research in rare diseases or where RCTs are not feasible [22] | Inherent biases in study design [22] |

| Increased external validity and larger sample sizes [22] | Data not collected for research purposes (e.g., billing data) [23] |

| More resource- and time-efficient than RCTs [22] | Lack of randomization, leading to systematic differences between groups [23] |

Q4: Is a large sample size in a real-world study sufficient to eliminate bias?

No. A common misconception is that a very large dataset—for example, containing ten million records—will automatically yield the correct answer if fed into an algorithm. From a statistical perspective, this is incorrect. A larger volume of data does not eliminate inherent biases related to how and why the data were collected [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge 1: Confounding in Real-World Evidence Studies

Problem: You are concerned that the results of your real-world study are biased because of confounding—systematic differences between patient groups receiving different treatments that influence the outcome.

Solution Steps:

- Hypothetical Design Exercise: Before analyzing the data, define what an ideal RCT to answer your question would look like. Specify the data you would collect for each patient and how you would measure outcomes [23].

- Data Harmonization: Map your available real-world data (e.g., Electronic Health Records, claims data) to this idealized design. This process helps identify specific gaps and limitations in your dataset [23].

- Advanced Statistical Methods: Employ robust causal inference methods, such as propensity score matching or weighting, to create more comparable groups from the observed data. The use of External Control Arms constructed from RWD can also be a solution when randomization is difficult [24].

Challenge 2: Assessing Long-Term Outcomes in a Diverse Population

Problem: An RCT showed promising results for a new oncology drug, but you need to understand its long-term effectiveness and safety in a broader, real-world population, including patients with comorbidities.

Solution Steps:

- Data Source Identification: Leverage longitudinal databases such as comprehensive electronic health record systems, cancer registries, or provincial healthcare databases [22].

- Cohort Definition: Define your study cohort with inclusive criteria that reflect clinical practice, including patients with poorer functional status (e.g., ECOG 2+) and comorbidities who were excluded from the original RCT [22].

- Long-Term Follow-Up: Analyze outcomes over an extended timeframe. RWE is particularly strong for providing this long-term surveillance data, which can reveal long-term side effects and survival outcomes that may not be apparent in shorter-term trials [22].

Methodological Frameworks and Data Integration

Integrated Evidence Generation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a proposed framework for systematically integrating RCT and RWE to build a more complete evidence base.

Quantitative Comparison of Trial vs. Real-World Populations

The table below summarizes key quantitative differences that create the evidence gap.

| Characteristic | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Real-World Evidence (RWE) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Population | Highly selected (often healthier, fewer comorbidities) [23] | Broad and inclusive, reflects clinical practice [22] [23] |

| Estimated Cancer Patient Participation | < 10% [22] | N/A (aims to include all treated patients) |

| Internal Validity | High (due to randomization) [22] [23] | Lower (susceptible to bias and confounding) [22] |

| External Validity (Generalizability) | Often limited [22] [23] | High [22] [23] |

| Data Collection | Prospective, pre-specified, and uniform [23] | Retrospective, from routine care (e.g., EHR, claims) [22] |

| Typical Use Case | Establishing efficacy and safety for regulatory approval [22] | Assessing effectiveness, patterns of care, and outcomes in practice [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential methodological components for conducting robust studies on population differences.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Data | Provides large-scale, longitudinal data on patient characteristics, treatments, and outcomes in a real-world setting [22] [23]. |

| Propensity Score Methods | A statistical technique used to adjust for confounding in observational studies by making treated and untreated groups more comparable [24]. |

| External Control Arms | Use of RWD to create a control group for a single-arm trial or to augment an existing RCT control arm when randomization is not feasible [24]. |

| Pragmatic Trial Design | A trial design that aims to maximize applicability of results to routine clinical practice by using broader eligibility criteria and flexible interventions [24]. |

| Data Quality Assessment Framework | A set of procedures to evaluate and improve the quality of RWD, recognizing it was collected for care, not research [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Evidence Integration

Protocol 1: Prospective Planning of Complementary RWE and RCT Studies

Objective: To generate complementary evidence on a new immunotherapy for bladder cancer by proactively planning an RWE study alongside an ongoing RCT.

Methodology:

- Identify Evidentiary Gap: An RCT is ongoing but results are years away. The treatment is already in use, creating uncertainty for clinicians [23].

- Cohort Construction using EHR Data: Identify patients receiving the new immunotherapy and a comparator cohort receiving standard chemotherapy from oncology EHR databases [23].

- Outcome Comparison: Conduct a head-to-head comparison of overall survival or other relevant time-to-event outcomes between the two real-world cohorts, using appropriate statistical methods to control for confounding [23].

- Evidence Integration: Compare the RWE results with the findings from the RCT once they become available. The RWE can fill the "evidentiary gap" and provide earlier insights, while the RCT validates the findings in a controlled setting [23].

Outcome: In a real-world example, this approach showed that immunotherapy had a worse outcome early on but better long-term survival, a finding that was later confirmed when the RCT completed, demonstrating how both methods build a cohesive "edifice of evidence" [23].

Protocol 2: Assessing Generalizability of a Specific RCT

Objective: To quantify how well the results of a published RCT for a thoracic malignancy apply to patients treated in your local healthcare system.

Methodology:

- Define RCT Criteria: Extract all inclusion and exclusion criteria from the published RCT [22].

- Apply Criteria to Local Database: Query your local cancer registry or EHR database to identify all patients who received the relevant therapy. Then, apply the RCT's criteria to determine what percentage of your real-world population would have been eligible for the trial [22].

- Compare Outcomes: Compare the baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes (e.g., overall survival, toxicity rates) between the "RCT-eligible" subgroup and the "RCT-ineligible" subgroup within your local population [22].

- Interpretation: Significant differences in outcomes between these subgroups indicate a limitation in the generalizability of the original RCT findings to your broader patient population [22].

Bridging the Divide: Methodological Frameworks for Generalizability and Transportability

Diagnostic Guide: Is It a Generalizability or Transportability Problem?

Use this diagnostic table to determine the appropriate framework for your study and the key considerations for each.

| Aspect | Generalizability | Transportability |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship of Trial to Target | Trial sample is a subset of a target population [25]. | Trial and target populations are distinct; target includes individuals unable to participate in the trial [25]. |

| Core Question | "What would be the effect if applied to the entire population from which the trial participants were sourced?" | "What would be the effect if applied to a completely different population?" |

| Common Data Structure | Individual-level data from the trial and the broader target population [25]. | Individual-level covariate data from both the trial and the distinct target population; treatment and outcome only in the trial sample [25] [26]. |

| Key Assumption | The trial sample, though not perfectly representative, comes from the target population. | Differences between populations can be accounted for using measured covariates [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My trial and target populations differ significantly on key covariates. What is the primary statistical risk?

A: The primary risk is bias in the estimated treatment effect for the target population. This occurs when the distributions of effect modifiers—variables that influence how an individual responds to the treatment—differ between the trial and target groups. If these differences are not accounted for, the trial's effect estimate will not accurately reflect the effect in the target population [25].

Q2: When is it inappropriate to even attempt a generalizability or transportability analysis?

A: These methods are inappropriate when biases arise from fundamental differences in:

- Study setting (e.g., a controlled clinic vs. a home environment).

- Treatment administration (e.g., timing, formulation, or accompanying care).

- Outcome measurement (e.g., a professionally administered test vs. a self-reported survey) [25]. These methods only address bias from differences in the distribution of measured patient characteristics, not these other sources of external validity bias.

Q3: I have a very low response rate in my RCT. How much does this limit generalizability?

A: A low response rate makes an RCT prone to participation bias, but it does not automatically invalidate generalizability. One study of home care recipients (5.5% response rate) found that while participants differed from nonparticipants on some baseline factors (e.g., age, dental care use), they were similar on many others (e.g., morbidity, hospitalizations). This suggests generalizability may be more limited than often assumed, but the extent must be empirically checked [27]. Using routine data (e.g., claims data) to compare participants and all nonparticipants is a robust way to assess this bias [27].

Q4: What are the most common methodological approaches for these analyses?

A: A 2025 scoping review found that the majority of applied studies use methods that incorporate weights (e.g., inverse probability of sampling weights) to make the trial sample resemble the target population [28]. These methods are most often applied to transport effect estimates from Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) to target populations defined by observational studies [28] [26].

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Generalizability or Transportability Analysis

Follow this step-by-step workflow to structure your analysis [25].

| Step | Key Actions | Critical Checks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess Appropriateness | Define the target population. Determine if a generalizability or transportability question exists. | Ensure the research question is not confounded by differences in setting, treatment, or outcome measurement [25]. |

| 2. Ensure Data Availability | Secure individual-level data on covariates from both trial and target. Ensure treatment and outcome data are available from the trial. | Verify that key potential effect modifiers are measured and can be harmonized across data sources [25]. |

| 3. Check Identifiability Assumptions | Evaluate assumptions like conditional exchangeability (no unmeasured effect modifiers) and positivity. | Assess the feasibility of these assumptions given the study design and available data [25]. |

| 4. Select & Implement Method | Choose a statistical method (e.g., weighting, outcome modeling). | Consider the pros and cons of each method. Use established statistical packages for implementation [25]. |

| 5. Assess Population Similarity | Quantify the similarity between the trial and target populations using metrics like the effective sample size (ESS) after weighting. | Determine if the populations are sufficiently similar to proceed. A very low ESS may indicate limited overlap [29]. |

| 6. Address Data Issues | Handle missing data and measurement error in covariates. | Apply appropriate methods (e.g., multiple imputation) to prevent bias [25]. |

| 7. Plan Sensitivity Analyses | Design analyses to test the robustness of findings to potential violations of key assumptions, especially unmeasured confounding. | Strengthen conclusions by showing how results might change under different scenarios [25]. |

| 8. Interpret Findings | Compare the translated estimate to the original trial estimate. | Integrate results from sensitivity analyses into the final interpretation [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Causal Inference

This table details key methodological "reagents" and their functions in generalizability and transportability analyses.

| Tool / Method | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Inverse Probability of Sampling Weights | Creates a pseudo-population where the distribution of covariates in the trial sample matches that of the target population [29]. | Can be unstable if weights are very large. Monitor the Effective Sample Size (ESS). |

| Outcome Regression Modeling | Models the relationship between covariates, treatment, and outcome in the trial, then predicts outcomes for the target population [25]. | Relies on correct model specification. Can be efficient if the model is accurate. |

| G-Computation | A standardization technique that uses an outcome model to estimate the average outcome under different treatment policies for the target population. | Also dependent on correct model specification. Useful for time-varying treatments. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Quantifies how robust the findings are to potential unmeasured confounding or other assumption violations [25]. | Not a primary method, but essential for strengthening the credibility of conclusions [25]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving Generalizability of RCT Findings

Common Problem: The Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap

Description: A significant disconnect exists between the positive results of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) and the inconsistent outcomes observed when the intervention is applied in routine clinical practice [30]. This is often due to strict RCT inclusion criteria that exclude patients with complex comorbidities or socioeconomic factors, creating a population that doesn't reflect real-world diversity [30] [23].

Solution: Implement a workflow to assess, augment, and validate RCT findings using real-world data (RWD).

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary limitation of RCTs that this workflow addresses? A: The primary limitation is lack of generalizability [23]. RCTs are conducted under ideal, controlled conditions with specific patient populations, often excluding individuals with poorer prognoses, multiple health conditions, or those facing barriers to clinical trial access [30] [23]. Consequently, results may not fully translate to broader, more diverse real-world populations.

Q2: When should I consider using real-world data to complement an RCT? A: Consider using RWD in the following scenarios, as illustrated in the table below.

Table: Scenarios for Integrating Real-World Data with RCTs

| Scenario | Description | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Evidentiary Gaps | When an RCT is ethically or practically impossible, or when a new treatment is approved via pathways like the FDA's accelerated approval without a head-to-head RCT [23]. | Provides timely evidence for clinical decision-making. |

| Long-Term Outcomes | When assessing the long-term durability of benefits or safety concerns that a short-duration RCT cannot capture [30]. | Reveals long-term effectiveness and rare or delayed adverse events. |

| Heterogeneous Populations | When needing to evaluate treatment effects in patient subgroups (e.g., those with comorbidities) typically excluded from RCTs [30]. | Enables a more personalized approach to pain management. |

Q3: What are the major pitfalls when working with real-world data? A: The major pitfalls include:

- Confounding and Selection Bias: The lack of randomization means there can be systematic differences between patients who receive a treatment and those who do not, influenced by factors like symptom severity or clinician judgment [30].

- Data Quality Issues: Data from electronic medical records or claims databases are collected for clinical care and billing, not research. This can lead to inconsistent recording of outcomes, undocumented adverse events, and missing data crucial for analysis [30] [23].

- Misinterpretation of Data Volume: A common misconception is that a very large dataset (e.g., millions of patients) automatically produces the correct answer. However, more data does not eliminate inherent biases [23].

Workflow: Bridging the RCT and Real-World Evidence Gap

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for leveraging real-world evidence to assess and improve the generalizability of RCT findings.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Appropriateness for RWD Integration This initial assessment determines if and how RWD can address specific limitations of your RCT.

- Identify RCT Limitations: Clearly list the constraints of your original trial. Common limitations include a homogeneous patient population, short follow-up period, or idealized treatment conditions [30] [23].

- Formulate Research Question: Based on the limitations, frame a specific question. Example: "How does the efficacy of Drug X, demonstrated in a trial with healthy adults, translate to effectiveness in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities in a community setting?"

- Determine Data Needs: Identify the specific data points required to answer this question (e.g., long-term adherence rates, safety outcomes in a broader population, performance in specific excluded subgroups).

Protocol 2: Designing an Observational Study with RWD This protocol outlines the methodology for constructing a robust real-world study.

- Cohort Definition: Using the RWD source (e.g., Electronic Health Records, claims database), define your study cohorts. This includes an intervention group (patients who received the treatment) and a comparator group (patients who received a relevant alternative treatment) [23].

- Bias Mitigation: To address the lack of randomization, employ statistical techniques to minimize confounding.

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM): This technique balances measured characteristics between the treatment and comparator groups, simulating some aspects of randomization. A key limitation is that PSM can narrow the patient population, potentially affecting generalizability [30].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct additional analyses to test how sensitive your results are to unmeasured confounding.

- Outcome Harmonization: Define and align the outcomes from the RWD with those from the RCT. For example, map clinical billing codes from claims data to specific health outcomes measured in the trial [23].

Protocol 3: Interpreting Combined Evidence This final protocol guides the synthesis of evidence from both the RCT and RWD.

- Compare and Contrast: Place results from the RCT and the real-world study side-by-side. Look for patterns of consistency or divergence.

- Contextualize Differences: If findings differ, investigate potential reasons. For example, reduced effectiveness in the real world could be due to lower adherence or a sicker patient population, not necessarily an ineffective drug [30].

- Build an "Edifice of Evidence": Avoid over-relying on any single study. Instead, view the RCT and RWD as complementary bricks that, together, build a more complete and reliable body of evidence about a treatment's true value in clinical practice [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for RWD Research

| Item / Method | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Provides longitudinal, clinical data on pain scores, functional outcomes, comorbidities, and medication use collected during routine care [30]. | Data may be inconsistent and recorded for billing/clinical purposes, not research. Key outcomes like quality of life may be missing [30]. |

| Claims Databases | Offers large-scale data on healthcare utilization, prescriptions, and procedures, useful for population-level studies [30]. | Lacks granular clinical detail and cannot reliably capture patient-reported outcomes like psychosocial functioning [30]. |

| Propensity Score Matching (PSM) | A statistical method used to reduce selection bias in observational studies by balancing known confounding variables between treatment and control groups [30]. | Can improve internal validity but may limit generalizability by narrowing the study population to only matched patients [30]. |

| CONSORT Statement | A 25-item checklist providing a framework for the transparent and complete reporting of RCTs, which is essential for evaluating their quality and limitations [31] [32]. | Critical for assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the original RCT before designing a real-world follow-up [32]. |

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard for establishing causal treatment effects due to their high internal validity achieved through random assignment [33] [34]. However, their findings often lack generalizability (external validity) to real-world populations because trial participants are frequently highly selected and may not represent patients encountered in routine clinical practice [7]. Real-world evidence (RWE) trials, which use data collected from routine healthcare settings, offer a potential solution with better generalizability but require robust statistical methods to address confounding bias inherent in non-randomized data [7] [33].

Propensity score methods and outcome modeling serve as crucial analytical techniques to reduce selection bias in observational studies, thereby improving the reliability and generalizability of clinical research findings to broader patient populations [35] [34]. This technical guide addresses common implementation challenges and provides practical solutions for researchers working to bridge the gap between RCT efficacy and real-world effectiveness.

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the fundamental purpose of propensity score methods?

Propensity score methods aim to reduce selection bias in observational studies by balancing the distribution of observed baseline covariates between treated and untreated groups, thereby mimicking some key properties of randomized experiments [35] [34]. The propensity score itself is defined as the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed baseline characteristics [34]. These methods help improve the generalizability of findings by creating more comparable groups that better represent real-world populations [7].

How does inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) create a pseudo-population?

IPTW uses weights based on the propensity score to create a "pseudo-population" where measured confounders are equally distributed across treatment groups [33]. Weights are calculated as the inverse of the probability of receiving the actual treatment: 1/propensity score for the treated group and 1/(1-propensity score) for the untreated group [33]. This weighting scheme effectively creates a scenario where treatment assignment is independent of the measured covariates, approximating the conditions of a randomized trial [36] [33].

When should stabilized weights be used in IPTW analysis?

Stabilized weights should be used to address the problem of extreme weights and inflated sample sizes in the pseudo-population [37]. Standard IPTW weights often double the effective sample size in the pseudo-data, leading to underestimated variances and inappropriately narrow confidence intervals [37]. Stabilized weights preserve the original sample size and provide more appropriate variance estimates while maintaining the consistency of the treatment effect estimate [37].

Table: Comparison of Weighting Approaches in IPTW

| Weight Type | Formula (Treated) | Formula (Untreated) | Sample Size Impact | Variance Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstabilized | 1/PS | 1/(1-PS) | Inflated | Underestimated |

| Stabilized | P(T=1)/PS | P(T=0)/(1-PS) | Preserved | Appropriate |

PS = Propensity Score; P(T=1) = Marginal probability of treatment; P(T=0) = Marginal probability of no treatment [37]

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge 1: Extreme Propensity Score Weights

Problem Identification Extreme weights occur when certain patients have very high or very low probabilities of receiving their actual treatment, leading to influential observations that can destabilize effect estimates [37] [33]. This often indicates possible positivity violations, where some patient subgroups have minimal chance of receiving one treatment [36].

Diagnostic Steps

- Examine the distribution of estimated propensity scores in both treatment groups

- Calculate the range of weights and identify observations with weights above a predetermined threshold (e.g., >10)

- Assess the effective sample size in the weighted population [37]

Solution Strategies

- Use stabilized weights to reduce variability while maintaining unbiasedness [37]

- Truncate extreme weights by setting a maximum value (e.g., 10 for unstabilized weights)

- Consider alternative approaches such as overlap weights or matching weights if extreme weights persist [33]

Extreme Weights Troubleshooting Path

Challenge 2: Poor Covariate Balance After Propensity Score Adjustment

Problem Identification Despite propensity score adjustment, measured covariates remain imbalanced between treatment groups, potentially leading to biased effect estimates [38].

Diagnostic Steps

- Calculate standardized mean differences for all covariates before and after adjustment

- Visualize the distribution of propensity scores in both groups

- Assess variance ratios for continuous covariates [38]

Solution Strategies

- Refine the propensity score model by including interaction terms or non-linear terms for predictors [33]

- Consider alternative balancing methods such as covariate balancing propensity scores

- Use different propensity score techniques like optimal matching instead of weighting if balance remains poor [38]

Table: Covariate Balance Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Target Threshold | Interpretation | Software Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Mean Difference | <0.1 | Adequate balance | R: tableone; SAS: PROC STDIZE |

| Variance Ratio | 0.8-1.25 | Similar spread | R: cobalt; Stata: pstest |

| Kolmorogov-Smirnov Statistic | >0.05 | Similar distributions | R: cobalt |

Challenge 3: Model Specification Uncertainty

Problem Identification Uncertainty about which covariates to include in the propensity score model and whether to include non-linear terms or interactions [33] [34].

Diagnostic Steps

- Evaluate causal assumptions using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs)

- Assess clinical knowledge about variable relationships

- Test model fit and predictive performance [34]

Solution Strategies

- Include all known confounders - variables that affect both treatment and outcome [33]

- Include variables related to the outcome even if not associated with treatment to improve precision [33]

- Avoid variables affected by the treatment (mediators) to prevent bias [33]

- Use machine learning methods like random forests or boosting for complex relationships when sample size permits [34]

Covariate Selection Causal Pathways

Experimental Protocols

Propensity Score Estimation Protocol

Step 1: Variable Selection

- Include all known pre-treatment confounders that affect both treatment and outcome

- Incorporate variables associated with the outcome only to improve precision

- Exclude variables that are consequences of treatment (mediators) [33]

- Consider including clinically relevant interactions and non-linear terms [33]

Step 2: Model Fitting

- Use logistic regression for binary treatments:

ln(PS/(1-PS)) = β₀ + β₁X₁ + ... + βₚXₚ[38] - For complex relationships, consider machine learning approaches (random forests, boosting) [34]

- Validate model discrimination using c-statistic or ROC curves

Step 3: Propensity Score Extraction

- Extract predicted probabilities from the fitted model

- Assess common support by visualizing overlapping regions of propensity score distributions [38]

IPTW Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Weight Calculation

- For unstabilized weights:

weight = treatment/PS + (1-treatment)/(1-PS)[33] - For stabilized weights:

weight = treatment*P(T=1)/PS + (1-treatment)*P(T=0)/(1-PS)[37] - Where P(T=1) is the marginal probability of treatment in the sample

Step 2: Weight Assessment

- Examine weight distribution using histograms or summary statistics

- Calculate effective sample size:

(sum(weights))² / sum(weights²)[37] - Consider truncation if extreme weights persist (e.g., at 1st and 99th percentiles)

Step 3: Outcome Analysis

- Apply weights in outcome models using appropriate procedures (e.g.,

svyglmin R) - Use robust variance estimators or bootstrap methods for confidence intervals [37]

Balance Assessment Protocol

Step 1: Pre-adjustment Assessment

- Calculate standardized differences for all covariates before adjustment

- Visualize propensity score distributions by treatment group [38]

Step 2: Post-adjustment Assessment

- Recalculate standardized differences after weighting/matching

- Target absolute standardized difference <0.1 for adequate balance [38]

- Assess distributional balance using statistical tests or visualizations

Step 3: Iterative Refinement

- Refine propensity score model if balance is inadequate

- Consider alternative approaches if balance cannot be achieved

Current Research Context

The use of RWE to improve generalizability of trial findings is gaining traction in clinical research. Recent data shows that the share of RWE trial registrations with information on sampling increased from 65.27% in 2002 to 97.43% in 2022, with trials using random samples increasing from 14.79% to 28.30% over the same period [7]. However, sample correction procedures to address non-random sampling remain underutilized, implemented in less than 1% of nonrandomly sampled RWE trials as of 2022 [7], indicating significant opportunity for methodological improvement.

Table: RWE Trial Registration Trends (2002-2022)

| Year | Registrations with Sampling Info | Trials with Random Samples | Nonrandom Trials with Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 65.27% | 14.79% | 0.00% |

| 2022 | 97.43% | 28.30% | 0.95% |

Source: Analysis of clinicaltrials.gov, EU-PAS, and OSF-RWE registry data [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Propensity Score Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| R: tableone package | Covariate balance assessment | Standardized mean differences, pre/post balance | CreateTableOne(data, strata = "treatment") |

| R: WeightIt package | Propensity score weighting | Multiple weighting methods, diagnostics | weightit(treat ~ x1 + x2, data) |

| R: cobalt package | Balance assessment | Love plots, comprehensive balance stats | bal.tab(weight_output) |

| SAS: PROC PSMATCH | Propensity score analysis | Matching, weighting, stratification | PROC PSMATCH region=cs; |

| Stata: teffects package | Treatment effects | IPW, matching, AIPW | teffects ipw (y) (treat x1 x2) |

| Python: Causalinference | Causal estimation | Propensity scores, matching, weighting | causal.fit_propensity() |

Method Selection Framework

Method Selection Decision Path

This framework emphasizes that method selection should be guided by the target population of inference (ATE = average treatment effect; ATT = average treatment effect on the treated; ATO = average treatment effect in the overlap) and the degree of covariate overlap between treatment groups [34].

The Problem: The RCT and Real-World Evidence Gap

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for establishing the efficacy of medical interventions, answering the critical question: "Can the drug work?" under ideal, controlled conditions [39]. However, their stringent eligibility criteria, limited geographical and socioeconomic diversity, high costs, and long lag-times to results often limit their generalizability [39] [40]. This creates a significant "efficacy-effectiveness gap," where a treatment proven to work in a trial may not demonstrate the same level of benefit in routine clinical practice [39].

Conversely, Real-World Data (RWD)—data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of healthcare routinely collected from sources like electronic health records (EHRs), claims data, and registries—excels at showing how a drug performs in heterogeneous, real-world patient populations [39] [41]. Evidence derived from this data, Real-World Evidence (RWE), is increasingly used to support regulatory decisions and label expansions [39] [40]. The challenge is that studies attempting to replicate RCT results using observational RWD have frequently shown discordant results, highlighting the inherent methodological differences and potential biases in these data sources [39].

The Solution: An Integrated Approach

Integrating RCT and RWD data systematically, rather than viewing them as hierarchical or competing alternatives, is key to bridging this gap [24]. This integration allows researchers to:

- Extend Follow-up: Observe long-term outcomes of trial participants beyond the trial's conclusion [42].

- Enrich Patient Histories: Gain a more comprehensive view of a patient's health journey before, during, and after the trial [40].

- Reduce Patient Burden: Minimize redundant data collection and improve trial efficiency [40].

- Improve Generalizability: Characterize how trial results apply to underrepresented groups or broader real-world populations [42].

Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage (PPRL) is the critical enabling technology for this integration. PPRL allows for the matching of patient records across disparate data sources (e.g., RCT databases and EHRs) without the need to exchange direct, personally identifiable information (PII), thus protecting patient privacy and complying with regulations like HIPAA [43] [44].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core PPRL Workflow for RCT-RWD Integration

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process of linking RCT participant data with real-world data sources using a PPRL methodology.

Protocol: Implementing a PPRL Linkage for Trial Follow-up

This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide for researchers looking to implement a PPRL project to extend the follow-up of clinical trial participants using RWD.

Objective: To create a longitudinal patient dataset by linking records from a completed RCT with subsequent real-world data from electronic health records and claims databases to assess long-term outcomes.

Materials & Reagents:

| Item | Function/Specification |

|---|---|

| RCT Participant Dataset | Contains the clinical trial data for each participant. Must include a unique trial subject ID and necessary PII for linkage. |

| Real-World Data Sources | EHR from healthcare systems or insurance claims data. Must cover the geographic and temporal period of interest post-trial [40]. |

| PPRL Software Toolkit | A set of software packages used by data owners to extract and garble their data, and by the linkage agent to perform the matching [44]. Example: CODI PPRL tools. |

| Standardized PII List | A predefined, consented list of identifiers used for linkage (e.g., full name, date of birth, sex at birth, address). Must be consistently formatted across datasets [44]. |

| Secure Data Transfer Environment | A secure, often encrypted, channel for transmitting garbled data (tokens) from data owners to the linkage agent. |

| Linkage Quality Assurance (QA) Toolkit | A set of data quality checks applied at multiple stages of the PPRL process to ensure high match rates and accuracy [44]. |

Methodology:

Project Scoping & Governance:

- Define the clear research question and required RWD sources.

- Establish a governance framework that defines roles, responsibilities, and data use agreements between all parties (trial sponsor, RWD partners, linkage agent) [43].

- Secure ethical approval and ensure patient consent for data linkage is in place, where required [42].

Data Preparation and Standardization:

- At each data owner site (both RCT and RWD sources), standardize the raw PII fields to a common format (e.g., capitalize names, use a standard date format).

- Resolve inconsistencies and typographical errors in the PII to the greatest extent possible. Data quality at this stage is paramount for linkage accuracy [43].

Tokenization (Garbling/Hashing):

- Using the PPRL software, data owners convert the standardized PII into encrypted tokens (e.g., using a bloom filter-based method) [43] [45].

- This process is one-way and deterministic: the same PII will always produce the same token, but the original PII cannot be reconstructed from the token.

- Output: A file containing the trial subject ID (for RCT data) or the local patient ID (for RWD) and its associated set of tokens. Original PII is never shared.

Secure Transfer and Matching:

- The token files from all data owners are securely transferred to a trusted third-party Linkage Agent.

- The Linkage Agent uses probabilistic matching algorithms to compare tokens across the datasets and identify which tokens from the RCT dataset and the RWD datasets belong to the same individual [44].

- For each matched set of records, the Linkage Agent generates a new, anonymous LinkID.

Creation of the Analysis Dataset:

- The Linkage Agent returns a cross-walk file that maps the original dataset-specific IDs (trial subject ID, EHR patient ID) to the new, shared anonymous LinkID.

- The RCT data and the relevant RWD are then linked together using this cross-walk file to create a final, de-identified analysis dataset for the researcher.

Linkage Quality Assurance:

- Implement the QA toolkit to assess linkage quality at multiple stages [44].

- Key metrics include precision (the proportion of correctly matched links among all found links) and recall (the proportion of true matches that were successfully found), which in well-designed implementations can exceed 90% [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key components and considerations for building a PPRL solution for integrating clinical research data.

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in PPRL | Key Considerations for Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| PPRL Technique (Bloom Filter) | A reference standard method for creating encrypted tokens from PII. It allows for approximate string matching while preserving privacy [43]. | Choice of technique impacts accuracy and privacy. Bloom filters have been successfully scaled in large projects like the NIH N3C [43]. |

| Linkage Agent | A trusted third party that receives tokens from all data owners and performs the matching process without ever seeing the raw PII [44]. | Can be an independent organization or a dedicated unit within a larger entity. Critical for building trust in the system [45]. |

| Data Use Agreements (DUAs) | Legal contracts that govern the sharing and use of the linked, de-identified data. | Must clearly define the research purpose, data security requirements, and prohibitions against re-identification attempts. |

| Quality Assurance (QA) Toolkit | A set of checks to monitor and validate the linkage process and output quality [44]. | Essential for identifying issues like low birthdate concordance. Should include checks at data extraction, tokenization, and matching stages [44]. |

| Common Data Model (e.g., OMOP) | A standardized data structure into which both RCT and RWD can be transformed. | Not required for linkage, but greatly facilitates meaningful analysis after linkage by harmonizing variables like diagnoses and treatments [41]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Data Linkage and Quality

Q: The linkage process resulted in a lower match rate than expected. What are the primary factors that could cause this?

A: Low match rates are often a data quality issue at the source. Key factors to investigate include:

- PII Completeness and Accuracy: High rates of missing or incorrect PII fields (e.g., misspelled names, transposed birth dates) in either the RCT or RWD sources will significantly reduce match rates [43]. Implement stricter data validation at the point of entry in the RCT and profile RWD sources for completeness before linkage.

- Lack of Overlap: The RWD source may not have full coverage of the geographic regions or time periods where the trial participants received their care. Ensure the selected RWD sources are fit-for-purpose for your trial population [40].

- Tokenization Configuration: Inconsistent configuration of the tokenization/hashing algorithms between data owners can lead to non-matching tokens for the same individual. Standardize the PPRL software version and configuration settings across all partners [44].

Q: How can we validate the accuracy of our PPRL linkage?

A: While a perfect "gold standard" is often unavailable, several strategies can be employed:

- Use a Validation Subset: If consent permits, for a small subset of participants, use a trusted third party to perform a traditional linkage with clear-text PII and compare the results to the PPRL output [43].

- Assess Internal Consistency: Check the plausibility of matched data. For example, the diagnosis in the RWD should logically follow the trial indication. Illogical matches can indicate linkage errors.

- Benchmark Against Known Metrics: Compare the demographic characteristics of the matched cohort to the original RCT population and the broader RWD population to check for unexpected selection biases.

FAQ 2: Methodological and Analytical Challenges

Q: After successful linkage, how do we address confounding and bias when analyzing the combined data?

A: The linked dataset remains observational for the RWD portion. Rigorous study design is crucial:

- Target Trial Emulation: Design your observational analysis to emulate the design of a hypothetical RCT (the "target trial"), explicitly defining inclusion criteria, treatment strategies, outcomes, and statistical analysis plans before examining the linked data [41].

- Advanced Statistical Methods: Use techniques like propensity score matching or inverse probability of treatment weighting to adjust for measured confounders and create more comparable groups from the real-world population [40] [41].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct analyses to assess how sensitive your results are to unmeasured confounding.

Q: Our clinical trial collected specific lab values and imaging at protocol-defined timepoints, but the linked RWD has irregular, clinically driven collections with potential missingness. How should we handle this?

A: This is a common challenge. Solutions include:

- Define New, RWD-Feasible Endpoints: Create composite or proxy endpoints that can be reliably captured in RWD (e.g., "time to treatment discontinuation or next therapy" instead of progression-free survival based on strict scan schedules) [39].

- Multiple Imputation: Use statistical methods to impute missing data, making reasonable assumptions about the missingness mechanism and incorporating a range of predictive variables available in the linked dataset.