Beyond the Rule of Five: Optimizing Molecular Descriptors for Advanced Permeability Prediction in Drug Discovery

Accurately predicting molecular permeability is a critical challenge in drug discovery, especially for complex therapeutic modalities like cyclic peptides and heterobifunctional degraders that operate beyond traditional chemical space.

Beyond the Rule of Five: Optimizing Molecular Descriptors for Advanced Permeability Prediction in Drug Discovery

Abstract

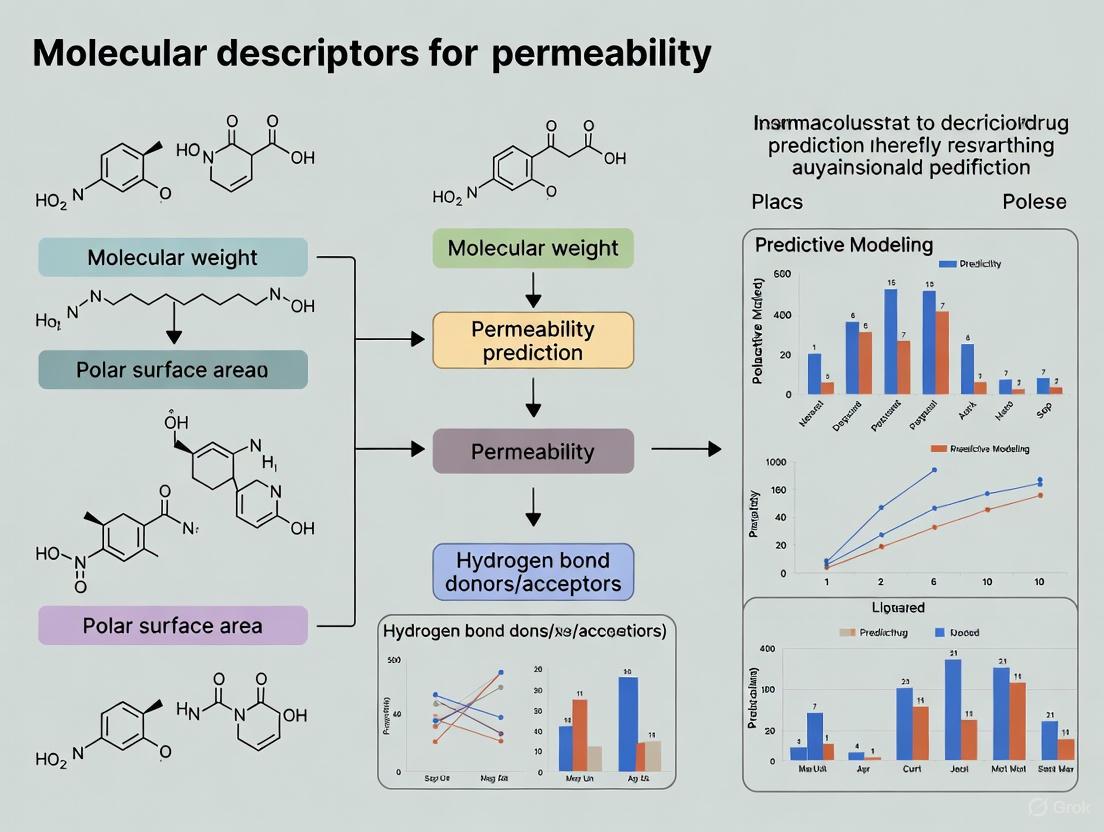

Accurately predicting molecular permeability is a critical challenge in drug discovery, especially for complex therapeutic modalities like cyclic peptides and heterobifunctional degraders that operate beyond traditional chemical space. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing molecular descriptors to enhance permeability prediction models. We explore the foundational relationship between molecular structure and permeability, evaluate traditional and advanced AI-driven methodologies, and present systematic strategies for feature selection and model troubleshooting. Through a comparative analysis of validation techniques and benchmark studies, we demonstrate how optimized descriptor selection can significantly improve model accuracy and interpretability, ultimately accelerating the design of permeable drug candidates.

The Blueprint of Permeability: Core Principles and Molecular Descriptors

The Critical Barrier in Drug Development

Permeability prediction is a fundamental challenge in modern drug discovery, directly impacting a compound's efficacy, bioavailability, and ultimate clinical success. A drug's ability to permeate biological membranes—such as the intestinal epithelium for absorption or the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for central nervous system (CNS) targets—determines whether it can reach its site of action in sufficient concentration [1] [2]. Despite its importance, accurately forecasting this property remains a significant bottleneck. The high failure rates of drug candidates, often due to poor pharmacokinetics, underscore the critical need for reliable predictive tools that can efficiently triage molecules early in the discovery pipeline [3].

This challenge is multifaceted. Biological membranes are complex, and permeability is governed by a confluence of passive transport, active influx, and efflux by transporter proteins [1] [4]. Experimental methods for determining permeability, such as cell-based assays (Caco-2, MDCK) and parallel artificial membrane permeability assays (PAMPA), are often time-consuming, costly, and low-throughput, making them impractical for screening vast chemical libraries [5] [6]. Consequently, the drug discovery industry increasingly relies on in silico models to bridge this gap, though these too face their own set of obstacles, which will be explored in this technical support guide.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical issues and questions encountered by researchers in the field of permeability prediction.

Data and Modeling Challenges

FAQ 1: Our machine learning model for BBB permeability performs well on the training set but generalizes poorly to new compound classes. What could be the issue?

- Potential Cause: The model may be overfitting to the specific chemical space of your training data and failing to extrapolate beyond its "applicability domain." This is a common problem when datasets are too small, lack chemical diversity, or have inherent biases [7].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Applicability Domain: Use methods like the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) algorithm to determine if your new compounds are structurally similar to your training set [6].

- Expand and Diversify Training Data: Incorporate larger, more diverse datasets. For BBB permeability, the B3DB database, which compiles over 7,800 compounds from 50 literature sources, can provide a more robust foundation for model training [3].

- Utilize Multitask Learning (MTL): Train a single model on multiple related endpoints simultaneously. A model predicting both Caco-2 permeability and MDCK-MDR1 efflux ratio can leverage shared information, often leading to higher accuracy and generalization than single-task models [2].

- Employ Physics-Based Methods: For critical compounds, use physics-based tools like the PerMM web server. These methods, which calculate permeability coefficients based on solubility-diffusion theory and membrane transfer energy profiles, are less reliant on specific training data and can offer better insights for novel chemotypes [7].

FAQ 2: How can we obtain meaningful permeability predictions for complex molecules like cyclic peptides, which often violate traditional rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five?

- Potential Cause: Traditional models based on simple molecular descriptors (e.g., logP, molecular weight) fail to capture the "chameleonic" properties of cyclic peptides—their ability to shift conformation in different environments to enable permeability [8] [9].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Adopt Specialized Deep Learning Models: Use models specifically designed for cyclic peptides, such as CPMP (Cyclic Peptide Membrane Permeability), which is based on a Molecular Attention Transformer (MAT). This architecture uses molecular graph structures and inter-atomic distances to capture complex structure-property relationships [5].

- Leverage Optimizer Tools: For lead optimization, use applications like C2PO (Cyclic Peptide Permeability Optimizer). This deep learning-based tool can take a starting structure and suggest chemical modifications predicted to improve membrane permeability [8].

- Incorporate Advanced Descriptors: Ensure your feature set includes descriptors for internal hydrogen bonding, which can lower the apparent polarity of cyclic peptides and increase permeability. Some commercial software like MembranePlus has begun integrating this parameter into their transport models [9].

FAQ 3: Our experimental PAMPA results do not correlate well with cell-based (Caco-2) assays. Which result should we trust?

- Potential Cause: PAMPA measures passive transcellular permeability through a synthetic lipid membrane, while Caco-2 cells contain active influx and efflux transporters (e.g., P-gp, BCRP) in addition to a more complex biological barrier. Discrepancies often arise for compounds that are substrates of these transporters [2] [6].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Determine Transport Mechanism: Run bidirectional assays (apical-to-basolateral and basolateral-to-apical) in Caco-2 cells to calculate an Efflux Ratio (ER). An ER significantly greater than 2 indicates active efflux, explaining the discrepancy with PAMPA [2].

- Use Assays in Tandem: Employ PAMPA as a high-throughput primary screen to identify compounds with good passive permeability. Follow up with Caco-2 assays on promising leads to understand the full picture of transport, including any active components [6].

- In Silico Modeling: Build or use models that predict both passive permeability and efflux liability. Machine learning models augmented with physicochemical features like LogD and pKa have shown improved accuracy in predicting these complex endpoints [2].

Interpretability and Decision-Making

FAQ 4: Our deep learning model for permeability is a "black box," making it difficult to gain chemical insights for lead optimization. How can we make the predictions more interpretable?

- Potential Cause: High-performing models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformers are inherently complex and do not readily identify which structural features drive the prediction.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Apply methods like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret machine learning models. SHAP analysis can rank molecular descriptors by their importance to the prediction, providing actionable insights [6].

- Use Models that Explain Synergistic Effects: Adopt explainable frameworks designed to identify combinations of molecular substructures that synergistically influence permeability. This moves beyond single-feature importance to reveal how groups of substructures collectively affect the property, offering deeper chemical insight for molecular design [4].

- Consider Intrinsically Interpretable Models: For tasks where interpretability is paramount, models like Explainable Boosting Machines (EBM) can offer a good balance between performance and transparency [6].

This section provides standardized methodologies for key experiments and consolidates quantitative performance data for various modeling approaches.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Intrinsic Caco-2 Permeability Assay

This protocol measures the passive permeability of a compound across a Caco-2 cell monolayer in the presence of efflux transporter inhibitors [2].

- Cell Culture: Grow Caco-2 cells to confluence on a semi-permeable filter support for 21-28 days to ensure full differentiation.

- Inhibitor Pre-treatment: Pre-incubate the cell monolayer with a cocktail of inhibitors for the main intestinal efflux transporters (P-gp, BCRP, MRP1).

- pH Gradient Setup: Use a pH of 6.5 on the apical side (donor) and 7.4 on the basolateral side (receiver) to mimic the physiological intestinal gradient.

- Dosing and Sampling: Add the test compound to the apical side. Collect samples from the basolateral side at 45 and 120 minutes.

- Analysis:

- Quantify compound concentrations in all samples using LC-MS/MS.

- Calculate the apparent permeability ((P{app})) in units of ( \times 10^{-6} ) cm/s using the formula: ( P{app} = (dQ/dt) / (A \times C0) ), where (dQ/dt) is the transport rate, (A) is the filter area, and (C0) is the initial donor concentration.

- Determine recovery to ensure mass balance.

Protocol 2: Building a Machine Learning Model for Permeability Prediction

A generalized workflow for creating a classification model to predict permeability (e.g., BBB+/-) from molecular structure [3] [6].

- Data Curation:

- Collect a dataset of compounds with reliable experimental permeability labels (e.g., from public sources like B3DB or internal assays).

- Standardize chemical structures (SMILES) using a tool like RDKit or the ChEMBL structure pipeline.

- Handle class imbalance using techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) if necessary [4].

- Feature Engineering:

- Molecular Descriptors: Calculate physicochemical properties (e.g., Molecular Weight, LogP, Topological Polar Surface Area).

- Fingerprints: Generate 2D structural fingerprints, such as 2048-bit Morgan fingerprints, using RDKit.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Split data into training, validation, and hold-out test sets (e.g., 80/10/10).

- Train multiple algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, Graph Neural Networks) on the training set.

- Optimize hyperparameters using the validation set.

- Evaluate final model performance on the unseen test set using metrics like Accuracy, ROC-AUC, and Precision-Recall.

Quantitative Performance of Select Permeability Prediction Models

Table 1: Benchmarking performance of various machine learning models for different permeability endpoints.

| Permeability Endpoint | Model Type | Dataset | Key Performance Metric | Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) | Random Forest (RF) | B3DB (7,807 compounds) | Test Accuracy | ~91% | [3] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) | Ensemble (RF + XGB) | 1,757 compounds | Validation Accuracy | 93% | [1] |

| PAMPA | Random Forest (RF) | 5,447 compounds | External Test Accuracy | 91% | [6] |

| PAMPA | Graph Attention Network (GAT) | 5,447 compounds | External Test Accuracy | 86% | [6] |

| Cyclic Peptide (Caco-2) | CPMP (MAT Model) | 1,310 peptides | Test R² | 0.62 | [5] |

| Caco-2 / MDCK Efflux | Multitask MPNN (with LogD/pKa) | >10,000 internal compounds | Superior performance vs. single-task and non-augmented models | Reported | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details key computational and experimental reagents essential for permeability prediction research.

Table 2: Essential research tools and resources for permeability prediction.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics and machine learning; generates molecular descriptors and fingerprints from SMILES. | Open-source |

| B3DB | Database | Benchmark dataset for BBB permeability; contains ~7,800 compounds with labels. | Public |

| CycPeptMPDB | Database | Literature-collected permeability data for cyclic peptides. | Public |

| PerMM Server | Web Tool | Physics-based modeling of passive translocation; calculates membrane binding energies and permeability coefficients. | Public |

| C2PO | Application | Deep learning-based optimizer for improving cyclic peptide membrane permeability. | Public (code) |

| CPMP | Model | Deep learning model (Molecular Attention Transformer) for cyclic peptide permeability prediction. | Open-source |

| ADMET Predictor | Software | Commercial platform for predicting ADMET properties, including permeability and transporter effects. | Commercial |

| MembranePlus | Software | Mechanistic modeling of in vitro permeability (Caco-2, PAMPA) and hepatocyte systems. | Commercial |

| Caco-2 / MDCK-MDR1 Cells | Biological Reagent | In vitro cell models for assessing intestinal permeability and P-gp mediated efflux. | Commercial |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Permeability Prediction Workflow

Model Selection Logic

Key Physicochemical Properties Governing Passive Diffusion

FAQs: Core Concepts and Property Relationships

What are the key physicochemical properties that govern passive diffusion across biological membranes?

Passive diffusion of molecules across biological membranes is primarily governed by a set of key physicochemical properties. These properties determine how easily a molecule can dissolve in and traverse the lipid bilayer.

Key Properties:

- Lipophilicity (Log P): This is a measure of a molecule's partitioning between oil and water phases, indicating its hydrophobicity. Higher lipophilicity generally favors passive diffusion through lipid bilayers. A calculated octanol–water partition coefficient (Log P) below 5 is typically considered analyzable for passive diffusion in experimental systems [10].

- Polar Surface Area (PSA): This describes the total surface area contributed by polar atoms (like oxygen and nitrogen). A lower PSA is generally favorable for diffusion, as it reduces the energy penalty for entering a hydrophobic environment. The Veber rules, for instance, use PSA as a key parameter for predicting oral bioavailability [10].

- Molecular Size and Compactness: Properties like molecular weight and the radius of gyration (Rgyr) are critical. Smaller and more compact molecules diffuse more readily. For molecules in the beyond-rule-of-five (bRo5) chemical space, the radius of gyration is a dominant predictor of passive permeability [11].

- Hydrogen Bonding Capacity: The count of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors on a molecule influences its permeability. Fewer hydrogen bond donors, in particular, are correlated with higher permeability, as they reduce the molecule's energy cost of desolvation [10].

- Molecular Polarizability: This property influences the free energy barriers for a molecule to penetrate a dense membrane. It is one of the parameters used in regression models to estimate diffusion barriers [12].

The following table summarizes the impact of these key properties:

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties Governing Passive Diffusion

| Property | General Impact on Passive Diffusion | Experimental/Prediction Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity (Log P) | Generally positive correlation; overly high log P can lead to poor solubility or sequestration [10]. | Analyzable space typically for Log P < 5; used in QSPR models [10]. |

| Polar Surface Area (PSA) | Inverse correlation; lower PSA favors diffusion [10] [11]. | A core parameter in Veber rules and other drug-likeness guidelines [10]. |

| Molecular Size/Weight | Inverse correlation; smaller molecules diffuse more easily [10]. | Permeability decreases with increasing molecular weight; critical for bRo5 space [11]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) Count | Inverse correlation; fewer HBDs favor diffusion [10]. | A key parameter in Lipinski's Rule of 5 [10]. |

| Radius of Gyration (Rgyr) | Inverse correlation; more compact molecules are more permeable [11]. | A dominant 3D descriptor for predicting permeability in bRo5 space [11]. |

| Molecular Polarizability | Influences the free energy barrier for membrane penetration [12]. | Used in linear regression models to predict diffusion barriers [12]. |

How do these properties interact in complex molecules, and how can we model their combined effect?

For complex molecules, especially large and flexible ones like heterobifunctional degraders and cyclic peptides that occupy beyond-rule-of-five (bRo5) chemical space, traditional 2D descriptors often fail to fully capture permeability. The interplay of properties like intramolecular hydrogen bonds (IMHBs), 3D polar surface area (3D-PSA), and radius of gyration (Rgyr) becomes critical [11].

Advanced Modeling Approaches:

- 3D Conformational Descriptors: Using conformational ensembles from techniques like well-tempered metadynamics provides more physically meaningful descriptors. Compact conformations with internal hydrogen bonding that shield polar groups can make a molecule a "chameleon" and significantly enhance its permeability [11] [13].

- Machine Learning (ML) Models: ML models that incorporate these 3D descriptors show consistently improved predictive performance for passive permeability compared to those using only 2D descriptors. Graph-based models, such as Directed Message Passing Neural Networks (DMPNN), have shown top performance in benchmarking studies, particularly when formulated as regression tasks [11] [13].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom MD simulations can calculate the free energy profiles (Potential of Mean Force) for a molecule crossing a membrane. This provides detailed, physical insights into the translocation process and can quantify activation barriers, which for various drugs can range from ~6-13 kcal/mol for permeable molecules to 37-63 kcal/mol for ionized molecules [12] [14].

Table 2: Modeling Techniques for Passive Permeability Prediction

| Modeling Technique | Key Descriptors/Inputs | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSPR/2D ML Models | Log P, TPSA, HBD/HBA count, molecular weight [13]. | Fast; useful for high-throughput virtual screening of small molecules. | Less effective for large, flexible molecules (e.g., cyclic peptides); fails to capture conformation. |

| 3D ML Models | Ensemble-derived 3D-PSA, Rgyr, IMHB count [11]. | Superior for bRo5 space; accounts for molecular flexibility and "chameleonic" behavior. | Computationally more intensive; requires generation of conformational ensembles. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | All-atom representation of molecule and membrane [12] [14]. | Provides atomic-level detail and free energy barriers; high physical realism. | Computationally very expensive; limited sampling can lead to inaccuracies. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Interpreting Discrepancies Between Predicted and Experimental Permeability

Problem: Your compound has favorable physicochemical properties based on simple rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of 5) but shows low experimental permeability.

Solution Steps:

- Verify Assay Conditions: Check for signal loss mechanisms in your experimental setup. In systems like Droplet Interface Bilayers (DIBs), a hydrophobic drug (high Log P) can partition into the surrounding oil phase or lipid micelles, leading to signal decay and misclassification of permeability. Ensure your assay accounts for this [10].

- Consider Molecular Charge: The free energy barrier for passive diffusion can be dramatically higher (37-63 kcal/mol) for ionized molecules compared to their neutral counterparts (e.g., 6-25 kcal/mol) [12]. Check the ionization state of your molecule at the experimental pH.

- Investigate "Chameleonic" Behavior: For larger, flexible molecules like cyclic peptides, permeability may depend on the ability to form compact conformations with internal hydrogen bonds that reduce the exposed polar surface area. Use molecular dynamics simulations or advanced ML models that use 3D descriptors to assess this potential [11] [13].

- Rule Out Active Efflux: Low apparent permeability might not be due to poor passive diffusion but could be caused by active efflux transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein) pumping the compound out of the cell. Conduct experiments with and without efflux transporter inhibitors [15].

Guide 2: Selecting a Predictive Model for Permeability

Problem: You need to choose a computational model to predict passive diffusion for a diverse compound library, including both small molecules and larger peptides.

Solution Steps:

- Categorize Your Compounds:

- For small molecules (<500 Da), traditional QSPR models or ML models using 2D descriptors (Log P, TPSA) can provide a good and fast initial estimate [10] [13].

- For larger, flexible molecules (e.g., cyclic peptides, degraders in bRo5 space), prioritize models that use 3D conformational descriptors (Rgyr, 3D-PSA, IMHB) [11].

- Evaluate Model Performance Metrics: When benchmarking models, note that regression tasks often outperform classification for permeability prediction. Be cautious of data splitting strategies; scaffold splits, while more rigorous, can yield lower generalizability if the training set's chemical diversity is reduced [13].

- Validate with External Data: Always test the model's predictions against a small set of experimentally known compounds from your chemical space of interest. For cyclic peptides, the CycPeptMPDB database is a valuable resource for external validation [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Passive Membrane Transport Analysis Using Droplet Interface Bilayers (DIBs)

This is a label-free HPLC-MS method to assess membrane transport of drug mixtures across a biomimetic membrane [10].

1. Hypothesis: The permeability of a drug across a DIB can be classified based on its physicochemical properties and the membrane's composition.

2. Workflow Diagram:

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: DIB Production. Form biomimetic bilayers by contacting water-in-oil droplets, each stabilized by a lipid monolayer, on a custom device with controlled actuation. The oil phase contains dissolved lipids (e.g., POPE) in hexadecane [10].

- Step 2: Assay Setup. Place a mixture of structurally diverse drugs in the "donor" droplet. The "acceptor" droplet contains buffer. Allow the system to incubate for a defined period (e.g., 16 hours) to allow for diffusion [10].

- Step 3: Sample Recovery. After incubation, actuate the device to disconnect the DIB by unzipping the contacted lipid monolayers. Recover the donor and acceptor droplets separately with a pipette [10].

- Step 4: HPLC-MS Analysis. Analyze the initial drug mixture and the recovered donor and acceptor droplets using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS). Identify each drug based on its column retention time and mass peak [10].

- Step 5: Data Analysis and Classification. Quantify the peak area for each drug in the donor and acceptor chromatograms. Classify permeability:

- Permeable (P=1): Equilibrium reached between donor and acceptor.

- Slightly Permeable (P=0.5): Drug detected in acceptor but not at equilibrium.

- Impermeable (P=0): Drug not detected in the acceptor (below the limit of detection) [10].

- Step 6: Correlation with Properties. Benchmark the permeability classifications against calculated molecular descriptors such as Log P, polar surface area, and hydrogen bond donor count [10].

4. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Key Reagents for DIB Permeability Assay

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phospholipids (e.g., POPE) | Forms the biomimetic lipid monolayer around droplets and the bilayer at their interface, creating the permeability barrier. |

| Hexadecane Oil | The bulk oil phase in which the water-in-oil droplets are formed and housed. |

| FDA-Approved Drug Library | Provides a structurally and physicochemically diverse set of compounds for testing. |

| HPLC-MS System | Provides the analytical separation (HPLC) and sensitive, label-free detection (MS) for quantifying drug concentrations in each droplet. |

Protocol 2: A Simple Dialysis Tubing Experiment to Demonstrate Diffusion

This classic experiment demonstrates the principles of diffusion and the role of a semipermeable membrane, suitable for foundational educational or pilot studies [16].

1. Hypothesis: The movement of molecules through a semipermeable membrane (dialysis tubing) is influenced by the molecule's size.

2. Workflow Diagram:

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Prepare the Dialysis Bag. Obtain a piece of dialysis tubing that has been soaked in water to make it soft and pliable. Tie one end securely to form a bag. Using a funnel, fill the bag with a glucose and starch solution. Tie the open end, leaving some space for expansion [17] [16].

- Step 2: Prepare the Beaker. Fill a beaker with distilled water and add a Lugol's iodine (IKI) solution, which will give the water a yellowish-amber color [17] [16].

- Step 3: Initiate the Experiment. Place the sealed dialysis bag containing the glucose-starch solution into the beaker with the IKI solution. Ensure the bag is fully submerged. Let the setup stand for 20-30 minutes [17] [16].

- Step 4: Record Observations. After the incubation period, observe the colors inside the dialysis bag and in the beaker solution. Use a glucose test strip to test for the presence of glucose in the beaker solution [16].

- Step 5: Expected Results and Analysis:

- The inside of the dialysis bag will turn dark blue because the small IKI molecules diffuse into the bag and react with starch, forming a blue complex.

- The beaker will test positive for glucose because the small glucose molecules diffuse out of the bag into the beaker.

- The starch remains inside the bag because its large molecules cannot pass through the pores of the dialysis tubing.

- This demonstrates that the dialysis tubing is a semipermeable membrane, allowing small molecules (glucose and IKI) to diffuse through while blocking large molecules (starch) [16].

4. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 4: Key Reagents for Dialysis Tubing Experiment

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Dialysis Tubing | Acts as an artificial semipermeable membrane, simulating the selective barrier of a cell membrane. |

| Starch Solution | A high molecular weight polysaccharide used to demonstrate the impermeability of large molecules. |

| Glucose Solution | A low molecular weight monosaccharide used to demonstrate the permeability of small molecules. |

| Lugol's Iodine (IKI) | A solution of iodine and potassium iodide; a small molecule indicator that turns blue-black in the presence of starch. |

| Glucose Test Strips | Used to detect the presence of glucose that has diffused out of the dialysis bag into the surrounding solution. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are molecular descriptors and why are they crucial for permeability prediction? Molecular descriptors are numerical values that quantify the structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties of a molecule [18]. In permeability prediction, they serve as the input features for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) or machine learning models. The core principle is that variations in a molecule's structure, captured by these descriptors, directly influence its ability to permeate biological barriers like the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria or the blood-brain barrier [19] [1] [18]. Using the right taxonomy of descriptors allows researchers to build predictive models that can prioritize promising drug candidates, reducing the need for costly and time-consuming experimental screening [19] [18].

Q2: What is the practical difference between 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors? The dimensionality refers to the structural representation used to calculate the descriptor [20].

- 1D-Descriptors are derived from the molecular formula alone and are typically constitutive, such as molecular weight or atom counts [20]. They are simple and fast to compute.

- 2D-Descriptors are based on the molecular graph, which encodes atom connectivity without 3D coordinates. Examples include topological indices and molecular fingerprints [20]. They capture aspects of molecular branching and shape.

- 3D-Descriptors require a three-dimensional conformation of the molecule and include properties like molecular volume, solvent-accessible surface area, and molecular interaction fields [20]. They can capture stereochemistry and spatial polarity but depend on the accuracy of the input conformation.

Q3: My QSAR model for predicting porin permeability is overfit. How can I improve its generalizability? Overfitting often occurs when the model is overly complex relative to the amount of training data, frequently due to using too many irrelevant descriptors [20] [18]. To address this:

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection techniques to identify and use only the most relevant descriptors. Methods include filter, wrapper, or embedded methods to reduce dimensionality and noise [18].

- Rigorous Validation: Use external validation with a completely held-out test set. Additionally, employ scaffold splitting, where the data is split such that molecules with different core structures are in the training and test sets. This tests the model's ability to generalize to truly novel chemotypes [13].

- Simplify the Model: If you have a small dataset, consider using simpler models like Partial Least Squares (PLS) or models with built-in regularization [18].

Q4: For predicting cyclic peptide membrane permeability, which type of descriptors and models show the best performance? A recent systematic benchmark of 13 AI methods found that the best performance for predicting cyclic peptide permeability came from graph-based models, such as the Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) [13]. Graph-based representations inherently capture the connectivity and topology of the molecule. Furthermore, formulating the problem as a regression task generally outperformed binary classification approaches. While deep learning models excelled, simpler models like Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) also achieved competitive results, especially when using well-curated molecular descriptors or fingerprints [13].

Q5: How do I handle missing values or standardize chemical structures before calculating descriptors? Data preparation is a critical step for building a robust model [18].

- Standardization: Standardize chemical structures by removing salts, normalizing tautomers, and handling stereochemistry consistently. Tools like RDKit are commonly used for this [18].

- Missing Values: For datasets with a low fraction of missing values, one common approach is to remove the compounds with missing data. Alternatively, imputation methods (e.g., k-nearest neighbors) can be used to estimate the missing values [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Performance and Low Predictive Power on External Test Sets This indicates that the model fails to generalize to new data.

| Phase | Action & Checklist |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | • Check Data Quality: Is the dataset large and diverse enough? Are the biological activity measurements reliable and consistent? [18]• Check Data Splitting: Was an external test set used, and was it completely withheld from model training and tuning? [18]• Check Feature Selection: Are there too many descriptors compared to the number of compounds? Use feature selection to reduce redundancy [20] [18]. |

| Solution | 1. Curate Your Dataset: Ensure high data quality and cover a diverse chemical space [18].2. Apply Rigorous Splitting: Use scaffold splitting to assess generalization to new core structures [13].3. Use a Simple Model: Start with a simpler, more interpretable model (e.g., PLS, RF) as a baseline before moving to complex deep learning models [13]. |

Problem: Model Interpreting Non-Causative Correlations (Chance Correlation) The model learns patterns from noise or irrelevant descriptors rather than true structure-property relationships.

| Phase | Action & Checklist |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | • Inspect Descriptors: Are the selected descriptors chemically intuitive and relevant to permeability (e.g., related to size, polarity, charge)? [19] [1]• Validate Statistically: Use Y-randomization (scrambling the response variable). If a model built on scrambled data shows high performance, it indicates chance correlation [18]. |

| Solution | 1. Leverage Domain Knowledge: When selecting descriptors, incorporate known factors that influence permeability, such as molecular weight, total polar surface area, lipophilicity (logP), and electric dipole moment [19] [1] [13].2. Apply Robust Validation: Always use internal cross-validation and a final external test set for a reliable performance estimate [18]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results When Predicting Permeability Across Different Barriers A model trained for one barrier (e.g., intestinal absorption) performs poorly on another (e.g., blood-brain barrier).

| Phase | Action & Checklist |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | • Barrier Specificity: Different biological barriers have distinct physicochemical and biological constraints. The BBB, for instance, is particularly restrictive and influenced by specific efflux transporters [1]. |

| Solution | 1. Barrier-Specific Models: Develop separate, barrier-specific QSAR models. Do not assume a universal permeability model [1].2. Incorporate Barrier-Relevant Descriptors: For the BBB, key descriptors often include logP, molecular weight, and polar surface area [1]. For bacterial porin permeability, molecular size, net charge, and electric dipole are also critical [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Building a QSAR Model for Permeability Prediction

The following workflow outlines the key steps for developing a validated QSAR model to predict molecular permeability [18].

1. Dataset Curation Compile a dataset of chemical structures and their experimentally measured permeability coefficients (e.g., from literature or databases like CycPeptMPDB) [13]. Ensure the dataset is of high quality, with documented experimental conditions and a diverse chemical space [18].

2. Data Preparation

- Standardize Structures: Use cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit) to remove salts, normalize tautomers, and handle stereochemistry [18].

- Handle Missing Values: For a small number of missing values, remove the compounds or use imputation methods [18].

- Scale Data: Normalize the biological activity data (e.g., log-transform) and scale molecular descriptors to have zero mean and unit variance [18].

3. Descriptor Calculation & Feature Selection

- Calculation: Use software like PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, or RDKit to calculate a comprehensive set of 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors for all compounds [18].

- Selection: Apply feature selection methods (e.g., genetic algorithms, LASSO regression, or random forest feature importance) to identify the most relevant and non-redundant descriptors. This prevents overfitting and improves model interpretability [20] [18].

4. Data Splitting Split the dataset into three parts:

- Training Set: Used to build the model.

- Validation Set: Used to tune model hyperparameters.

- External Test Set: Reserved for the final, unbiased evaluation of the model's predictive power. For a rigorous test of generalizability, use scaffold splitting [13].

5. Model Building and Internal Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate algorithms based on data size and complexity (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) for interpretability, Random Forest (RF) or Support Vector Machines (SVM) for non-linear relationships, or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for complex structures) [18] [13].

- Internal Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation or leave-one-out cross-validation on the training set to estimate model performance and avoid overfitting [18].

6. External Validation and Model Evaluation

- Final Assessment: Use the untouched external test set to evaluate the final model's predictive performance. This provides a realistic estimate of how the model will perform on new, unseen compounds [18].

- Evaluation Metrics: Report relevant metrics such as R² (for regression) or Accuracy/ROC-AUC (for classification), along with Mean Squared Error (MSE) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The table below lists key resources used in molecular descriptor calculation and permeability prediction research.

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for standardizing structures, calculating molecular descriptors, and generating fingerprints [13]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software capable of calculating multiple molecular descriptors and fingerprints for large compound libraries [18]. | |

| Dragon | A commercial software widely used for the calculation of a very large number of molecular descriptors [18]. | |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES Strings | A line notation for representing molecular structures as text, used as input for string-based models (e.g., RNNs) [13]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Bit strings that represent the presence or absence of particular substructures or features in a molecule, used for similarity searching and machine learning [13]. | |

| Molecular Graphs | A representation where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges, serving as the input for powerful Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [13]. | |

| Key Descriptors for Permeability | logP | The partition coefficient, measuring lipophilicity, a critical factor for passive diffusion through membranes [1] [13]. |

| Total Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | Describes the surface area associated with polar atoms, highly correlated with translocation through polar environments like porin channels and membrane permeation [19] [13]. | |

| Molecular Weight (MW) | A 1D descriptor; molecular size is a primary filter for many permeability barriers (e.g., BBB, porins) [19] [1]. | |

| Electric Dipole Moment | A 3D descriptor characterizing the molecule's charge separation; crucial for interacting with the electrostatic fields inside protein channels like bacterial porins [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What makes Beyond Rule of Five (bRo5) molecules and cyclic peptides so challenging for permeability prediction?

Traditional permeability prediction models are based on rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five, which work well for small, rigid molecules. bRo5 compounds (typically MW 500-3000) and cyclic peptides violate these rules and exhibit complex behaviors. The principal challenge is their chameleonicity—the ability to adopt different conformations in different environments. They display an "open" conformation in aqueous settings to expose polar groups for solubility, and a "closed" conformation in lipid membranes to shield these groups for permeability. This dynamic behavior is difficult to capture with conventional molecular descriptors designed for smaller, less flexible molecules [21] [22].

Q2: What are the key experimental assays for measuring permeability, and how do they differ?

The choice of assay is critical, as each provides different information. The most common assays used for bRo5 molecules and cyclic peptides are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Key Experimental Permeability Assays

| Assay Name | Description | Application & Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PAMPA(Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay) | Measures passive diffusion across an artificial phospholipid membrane [21]. | High-throughput; low-cost; useful for early-stage screening of passive transport [5]. |

| Caco-2 | Uses a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that forms a monolayer with tight junctions and expresses various transporters [21]. | Models active and passive transport, including efflux; more biologically relevant but slower and more expensive than PAMPA [5]. |

| RRCK(Ralph Russ Canine Kidney) | Uses a canine kidney cell line [5]. | Similar application to MDCK and Caco-2 assays for predicting cellular permeability [5]. |

| MDCK(Madin-Darby Canine Kidney) | Uses a different canine kidney cell line [5]. | Another cell-based model used to assess permeability; often transfected with human transporters like MDR1 to study specific efflux [5]. |

Q3: Our team has a cyclic peptide hit with poor permeability. What are the primary chemical modification strategies to improve it?

Several strategies have been developed to enhance the membrane permeability of cyclic peptides, often by encouraging the "closed," permeability-competent conformation [22].

- N-methylation: Adding methyl groups to backbone amide nitrogen atoms reduces the number of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs). This decreases desolvation energy and can promote the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, stabilizing a closed conformation [22].

- Amide Bond Isosteres: Replacing amide bonds with non-standard linkages (e.g., olefins, heterocycles) can improve metabolic stability and reduce polarity [22].

- Steric Occlusion: Introducing bulky side chains can physically shield polar groups from the hydrophobic environment of the membrane [22].

- Macrocycle Size and Sequence Optimization: Adjusting the ring size and the sequence of amino acids can pre-organize the molecule into a conformation that is more amenable to membrane passage [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Discrepancy Between In Silico Prediction and Experimental Permeability Results

Problem: A bRo5 compound shows good predicted permeability in a simple model (e.g., based on LogP), but fails in a cell-based assay (e.g., Caco-2).

Solution:

- Investigate Efflux Transporter Involvement: The most common cause is efflux by transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp). To troubleshoot:

- Run the Caco-2 assay in both apical-to-basolateral (A-B) and basolateral-to-apical (B-A) directions. A B-A/A-B ratio greater than 2-3 is a strong indicator of active efflux.

- Repeat the assay in the presence of a specific efflux transporter inhibitor (e.g., Elacridar for P-gp). A significant increase in A-B permeability confirms transporter involvement [23].

- Assess Conformational Dynamics: Simple descriptors like LogP or tPSA are static and miss chameleonicity.

- Use advanced computational methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations in both aqueous and lipid environments to see if the molecule adopts a permeability-prone state [21].

- Employ experimental techniques like NMR spectroscopy to study the molecule's conformation in different solvents.

Issue 2: Poor Aqueous Solubility Obscuring Permeability Measurement

Problem: A compound is so insoluble that a reliable permeability coefficient (e.g., Papp) cannot be determined, as the concentration gradient driving diffusion is negligible.

Solution:

- Determine the Dose Number (Do): Calculate the Do to quantify the solubility problem. A Do greater than 1 indicates insufficient solubility. The formula is: Do = (dose / 250 mL) / thermodynamic solubility [21].

- Use Kinetic Solubility for Early Screening: In early discovery, use kinetic solubility measurements from DMSO stocks. This is high-throughput and requires little compound, but be aware it may overestimate true thermodynamic solubility [21].

- Medicinal Chemistry Strategies: Improve intrinsic solubility through structure modification.

- Introduce Ionizable Groups: Adding a basic or acidic group can enhance solubility at relevant pH levels.

- Reduce Crystal Lattice Energy: Disrupting strong intermolecular interactions in the solid state by introducing conformational strain or lowering symmetry can improve solubility [21].

- Employ Formulation Aids: As a last resort in testing, use co-solvents (e.g., DMSO), surfactants, or cyclodextrins to create a temporary, apparent increase in solubility for the assay. Remember, this does not solve the fundamental solubility issue [21].

Data Presentation: Performance of Modern Predictive Models

Given the limitations of traditional QSAR, new machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models have been developed specifically for cyclic peptides. The table below summarizes the performance of some recently published tools.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cyclic Peptide Permeability Prediction Models

| Model Name | Model Type | Input Features | Reported Performance (R²) | Key Features / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2PO [22] | Deep Learning (Graph Transformer) & Optimizer | Molecular Graph Structure | N/A (Optimization tool) | First-in-class optimizer that suggests chemical modifications to improve permeability; uses a post-correction tool for chemical validity [22]. |

| CPMP [5] | Deep Learning (Molecular Attention Transformer) | SMILES, 3D Conformations, Bond Info | PAMPA: 0.67Caco-2: 0.75RRCK: 0.62MDCK: 0.73 | Open-source; integrates molecular graph structure and inter-atomic distances; accessible for high-throughput screening pipelines [5]. |

| PharmPapp [5] | Not Specified (KNIME pipeline) | Not Specified | Caco-2/RRCK: 0.484 - 0.708 | Limited to the KNIME platform; performance is less robust than newer models [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Utilizing the C2PO Tool for Cyclic Peptide Optimization

Purpose: To use the C2PO (Cyclic Peptide Permeability Optimizer) tool to generate structurally modified cyclic peptides with improved predicted membrane permeability [22].

Methodology:

- Input: Provide the starting cyclic peptide structure in SMILES notation.

- Optimization Engine: The underlying Graph Transformer model calculates the gradient of a "desired loss" function (aiming for a target permeability value). Using a modified HotFlip algorithm, it approximates the best atomic substitutions (flips) to minimize this loss.

- Structure Generation: The algorithm proposes new molecules by flipping atoms at the most favorable positions. A beam search technique explores the top candidates iteratively.

- Validity Correction: A key step involves passing the generated structures through an automated, dictionary-based molecular correction tool. This ensures the output molecules are chemically valid, circumventing a common issue with ML-generated structures.

- Output: A list of proposed cyclic peptide structures, ranked by their improved predicted permeability and similarity to the original compound.

Protocol 2: Predicting Permeability with the CPMP Model

Purpose: To predict the membrane permeability of a cyclic peptide using the CPMP (Cyclic Peptide Membrane Permeability) deep learning model [5].

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Represent the cyclic peptide as a SMILES string. The model automatically processes this to generate 3D molecular conformations, bond information, and atom features.

- Feature Encoding: Construct three key matrices:

- Atom Feature Matrix: Represents atom types and properties.

- Distance Matrix: Encodes inter-atomic distances.

- Adjacency Matrix: Represents the molecular graph structure (atomic connectivity).

- Model Architecture (MAT Core): The matrices are fed into the Molecular Attention Transformer (MAT). The MAT's self-attention mechanism is enhanced by incorporating the distance and adjacency information, allowing it to effectively capture complex structure-property relationships. This is followed by position-wise feed-forward networks, a global pooling layer, and a final fully-connected layer for prediction.

- Output: The model outputs a predicted permeability value (LogPexp) for the input cyclic peptide.

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Diagram: CPMP Model Workflow for Permeability Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Permeability Research of bRo5 Molecules

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PAMPA Kit | A commercially available kit containing artificial phospholipid membranes on a multi-well plate. | High-throughput, low-cost assessment of passive transcellular permeability in a non-cell-based system [21]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line that spontaneously differentiates into enterocyte-like cells. | The gold-standard in vitro model for predicting oral absorption, accounting for passive diffusion, paracellular transport, and active efflux/influx [21] [24]. |

| Transporter Inhibitors(e.g., Elacridar, Ko143) | Small molecule inhibitors specific for efflux transporters (P-gp and BCRP, respectively). | Used in cell-based assays (Caco-2, MDCK) to confirm and quantify the role of specific efflux transporters in limiting permeability [23]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used to generate molecular descriptors (e.g., Morgan fingerprints), process SMILES strings, and handle molecular graphs for machine learning tasks [22] [5]. |

| CycPeptMPDB Database | A public database of literature-collected permeability data for cyclic peptides. | Serves as the primary data source for training and benchmarking new machine learning models like C2PO and CPMP [22] [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of error in experimental permeability measurements? Errors in permeability testing often stem from instrumentation inaccuracies, inadequate sample preparation, and improper boundary conditions during experiments [25]. For shale reservoirs, using steady-state methods for low-permeability samples (below 0.1 mD) can yield significant errors (up to 96.84%) compared to pulse decay methods due to factors like long measurement times leading to temperature fluctuations and device leakage [26]. Consistently following standardized protocols is crucial to minimize inter-laboratory variability, as demonstrated in permeability benchmarks where adherence to guidelines reduced result scatter to below 25% [27].

FAQ 2: Which machine learning model is most effective for predicting cyclic peptide permeability? Based on recent systematic benchmarking of 13 AI methods, graph-based models, particularly the Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN), consistently achieve top performance for predicting cyclic peptide membrane permeability [28]. The Molecular Attention Transformer (MAT) is another high-performing architecture, achieving R² values of 0.67 for PAMPA permeability prediction and outperforming traditional machine learning methods like Random Forest (RFR) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) [29]. For polymer pipeline hydrogen loss prediction, neural network models have demonstrated exceptional predictive ability with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99999 [30].

FAQ 3: How does data splitting strategy affect model generalizability? Scaffold-based splitting, intended to rigorously assess generalization to new chemical structures, actually yields substantially lower model generalizability compared to random splitting [28]. This counterintuitive result occurs because scaffold splitting reduces chemical diversity in training data. For optimal performance, researchers should use random splitting while ensuring duplicate measurements are consistently allocated to the training set to prevent data leakage [28].

FAQ 4: What molecular representations work best for permeability prediction? Model performance strongly depends on molecular representation. Graph-based representations that capture atomic relationships generally outperform other approaches [28] [29]. For cyclic peptides, representations incorporating molecular graph structures and inter-atomic distances in attention mechanisms have proven particularly effective [29]. Simpler representations like molecular fingerprints can still achieve competitive results with methods like Random Forest [28].

FAQ 5: Which experimental permeability assay should I choose for my research? The optimal assay depends on your permeability range and research goals. For shale reservoirs with permeability below 0.1 mD, pulse decay methods are more reliable than steady-state methods [26]. For cyclic peptide screening, PAMPA assays provide high-throughput capability with extensive data for model training (6,701 samples available), while cell-based assays (Caco-2, RRCK, MDCK) offer biological relevance but with smaller dataset sizes [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Generalization to New Molecular Scaffolds

Problem: Your trained model performs well on validation data but poorly on new molecular scaffolds not represented in training.

Solution:

- Verify Data Splitting: Implement scaffold-based splitting during validation to better estimate real-world performance [28].

- Expand Training Diversity: Incorporate diverse molecular classes beyond your primary focus area [19].

- Feature Analysis: Ensure your molecular descriptors capture universal permeability determinants rather than scaffold-specific artifacts [19].

- Transfer Learning: For small datasets, fine-tune models pre-trained on larger permeability datasets [29].

Prevention: During initial experimental design, consciously sample from multiple molecular classes and scaffold types rather than focusing on narrow chemical space [19].

Issue 2: High Discrepancy Between Experimental and Predicted Permeability Values

Problem: Significant inconsistencies exist between your experimental measurements and computational predictions.

Solution:

- Audit Experimental Conditions: Verify that permeability assays follow standardized protocols, as minor methodological variations can cause significant scatter [27].

- Check Applicability Domain: Ensure your test compounds fall within the chemical space of the model's training data [28].

- Compare Multiple Methods: Implement several prediction approaches (correlation-based, neural network, etc.) to identify consensus predictions [30].

- Validate with Reference Compounds: Include compounds with well-established permeability values as internal controls [26].

Diagnostic Table:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic overprediction | Training data bias toward high-permeability compounds | Apply class balancing or augment with low-permeability examples [28] |

| High variance in predictions | Inadequate feature representation | Switch to graph-based molecular representations [29] |

| Inconsistent errors across similar compounds | Assay variability | Standardize experimental protocol and verify measurement stability [27] |

Issue 3: Insufficient Data for Training Accurate Prediction Models

Problem: Limited experimental permeability data prevents training of robust machine learning models.

Solution:

- Leverage Public Databases: Utilize curated databases like CycPeptMPDB containing thousands of cyclic peptide permeability measurements [28].

- Data Augmentation: Apply legitimate augmentation strategies while avoiding data leakage [28].

- Transfer Learning: Use models pre-trained on related molecular property prediction tasks [29].

- Hybrid Modeling: Combine data-driven approaches with physics-based models requiring fewer parameters [30].

Implementation Workflow:

Issue 4: Inconsistent Permeability Measurements Across Replicates

Problem: Experimental permeability measurements show high variability between technical replicates.

Solution:

- Standardize Sample Preparation: In textile permeability testing, standardized specimen preparation reduced inter-laboratory variability to below 25% [27].

- Control Environmental Factors: Regulate temperature and humidity, as fluctuations during long measurements (especially in steady-state methods) significantly impact results [26].

- Validate Instrument Calibration: Regularly calibrate pressure sensors and flow measurement devices [26] [25].

- Implement Quality Controls: Include reference materials with known permeability in each experimental batch.

Prevention Protocol:

- Pre-experiment: Calibrate instruments, verify environmental controls

- Sample Preparation: Follow standardized protocols for consistent packing/placement

- During Experiment: Monitor temperature stability, especially for lengthy tests

- Post-experiment: Include data quality checks (e.g., pressure decay curves)

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Pipeline for Permeability Prediction

Based on: Systematic benchmarking of 13 AI methods for cyclic peptide permeability prediction [28]

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- Data Curation: Collect and standardize permeability measurements from CycPeptMPDB or similar databases [28]

- Molecular Representation: Convert compounds to appropriate representation (graph-based recommended) [29]

- Model Training: Implement multiple algorithms with proper cross-validation

- Performance Evaluation: Assess using multiple metrics (R², MSE, MAE) across different data splits

- Deployment: Apply best-performing model to new compound prediction

Protocol 2: Experimental Permeability Measurement Selection Guide

Based on: Comparative study of permeability testing methods for shale reservoirs [26]

Method Selection Table:

| Method | Optimal Permeability Range | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State | > 0.1 mD | Simple operation, established theory [26] | Long measurement time, temperature sensitivity [26] |

| Pulse Decay | < 0.1 mD | Reduced test time, minimal temperature effects [26] | Complex data analysis, requires equilibrium time [26] |

| NMR | 10⁻³ - 100 mD | Rapid, non-destructive, pore structure insight [26] | Requires model calibration, limited to specific fluids [26] |

| PAMPA | Cyclic peptides | High-throughput, artificial membrane [29] | Lacks biological complexity [29] |

| Cell-Based (Caco-2, etc.) | Drug candidates | Biological relevance, accounts for transporters [29] | Lower throughput, higher cost [29] |

Implementation Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Permeability Research:

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CycPeptMPDB Database | Curated database of ~7,334 cyclic peptides with permeability data [28] | Compiles data from 47 studies; essential for model training |

| PAMPA Assay Kit | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay for high-throughput screening [29] | Artificial membrane system; higher throughput than cell-based assays |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Human colon epithelial cancer cells for permeability modeling [29] | Provides biological transport insight; includes efflux systems |

| Carbon Fabric Preforms | Standardized porous media for permeability benchmarking [27] | Enables inter-laboratory comparison; 2×2 twill, 285 g/m² areal density |

| NMR Relaxometry Equipment | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance for non-destructive permeability estimation [26] | Based on T₂ relaxation times; rapid measurement capability |

| Molecular Graph Representation | Atomic-level representation for machine learning [29] | Nodes=atoms, edges=bonds; enables DMPNN and MAT models |

| RDKit Cheminformatics | Open-source toolkit for molecular fingerprint generation [28] | Generates 1024-bit Morgan fingerprints for traditional ML |

Performance Comparison Tables

Table 1: Machine Learning Model Performance for Permeability Prediction

| Model Type | Molecular Representation | R² Value | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMPNN | Molecular Graph | 0.67 (PAMPA) [28] | Cyclic peptides with diverse scaffolds |

| MAT | Graph + Attention | 0.67-0.75 (Various assays) [29] | Cyclic peptides with transfer learning |

| Random Forest | Molecular Fingerprints | 0.39-0.67 [28] [29] | Moderate-sized datasets, interpretability |

| Neural Network | Pipeline Parameters | 0.99999 (Correlation) [30] | Hydrogen loss in polymer pipelines |

| Correlation Model | Algebraic Expressions | 5% error [30] | Rapid estimation of pipeline permeation |

Table 2: Experimental Method Performance Characteristics

| Method | Measurement Time | Error Range | Suitable Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State | Hours to days | >96% for <0.1 mD [26] | High-permeability rocks (>0.1 mD) |

| Pulse Decay | Minutes to hours | <28% for <0.1 mD [26] | Low-permeability shale, tight rocks |

| PAMPA | High-throughput | R²=0.67 (ML prediction) [29] | Cyclic peptides, drug-like molecules |

| Cell-Based Assays | Moderate throughput | R²=0.62-0.75 [29] | Compounds with active transport |

| NMR | Minutes | 19.43% error vs. pulse decay [26] | Core samples with fluid saturation |

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Descriptor Calculation and Model Implementation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of using handcrafted physicochemical descriptors in QSPR studies?

Handcrafted physicochemical descriptors provide a transparent and interpretable foundation for QSPR models. Unlike some complex "black box" machine learning features, these descriptors are often grounded in well-understood chemical principles, such as lipophilicity (often represented by logP) and molecular weight [1]. This interpretability allows researchers to gain valuable insights into the relationship between molecular structure and macroscopic properties, which is essential for guiding the rational design of new compounds, such as those intended to cross the blood-brain barrier [1] [31].

FAQ 2: My QSPR model performs well on training data but poorly on new compounds. What could be the cause?

This issue often stems from overfitting or the model being applied outside its applicability domain [31]. Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex and learns noise from the training data instead of the underlying relationship. Furthermore, a model is only reliable for predicting new compounds that are structurally similar to those in its training set. Validating the model through rigorous methods, such as external validation with a separate test set and establishing a defined applicability domain, is crucial to ensure its predictive power for new chemicals [31].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the predictive performance of my descriptor-based QSPR model?

Two key strategies are descriptor optimization and model integration. Rather than using all available descriptors, it is beneficial to identify and select the most relevant molecular features for the specific property being studied [32] [33]. Additionally, combining different types of descriptors or fingerprints can create a more comprehensive molecular representation. For instance, building a conjoint fingerprint by supplementing a key-based fingerprint like MACCS with a topological fingerprint like ECFP has been shown to capture complementary information and improve predictive performance in deep learning models [34].

FAQ 4: What are common data quality issues that can undermine a QSPR model?

The foundation of any robust QSPR model is high-quality input data. Common issues include data scarcity, which can limit the model's ability to learn general patterns, and inconsistencies in experimental data from different sources [32] [35]. For properties like gas permeability in polymers, which can be an arduous task to measure empirically, inconsistencies in the compiled data spanning decades can introduce noise [35]. Always ensure data is curated and standardized before model development.

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Model Performance and Overfitting

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High training accuracy, low prediction accuracy | Model overfitting to noise in the training data. | Apply feature selection techniques (e.g., genetic algorithms) to reduce redundant descriptors and use cross-validation. | [33] [31] |

| Model fails to generalize to new external compounds | Compounds are outside the model's Applicability Domain (AD). | Define the model's AD using appropriate methods and only use it for predictions within this domain. | [31] |

| Weak or non-existent structure-property relationship | The selected descriptors are not relevant to the target property. | Re-evaluate descriptor choice; incorporate domain knowledge (e.g., lipophilicity for permeability). | [1] [31] |

Data Quality and Preparation

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent predictive results | Underlying data is scarce or highly variable. | Use large, high-quality datasets and check for consistency in experimental protocols. | [32] [35] |

| Descriptor collisions or loss of chemical insight | Use of hashed fingerprints where different structures map to the same bit. | Use non-hashed, interpretable fingerprints like MACCS keys for better mechanistic insight. | [35] |

| Model is sensitive to small changes in the training set | The model is not robust, potentially due to outliers. | Investigate the training set for outliers and apply data randomization (Y-scrambling) to check for chance correlations. | [31] |

Descriptor Selection and Interpretation

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty interpreting the model's decisions | Using complex "black box" descriptors or models. | Prioritize interpretable descriptors and use model-agnostic interpretation tools like SHAP. | [33] [35] |

| Standalone descriptor set provides limited predictive power | The molecular representation only captures one aspect of the chemistry. | Develop a conjoint fingerprint by combining two supplementary fingerprint types (e.g., MACCS and ECFP). | [34] |

| Unclear how molecular changes affect the property | The model lacks mechanistic insight. | Use methods that dynamically adjust descriptor importance to link key molecular features to the endpoint. | [33] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Developing a Robust QSPR Model with Handcrafted Descriptors

The following workflow outlines the essential steps for building a validated QSPR model, from data collection to deployment.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Collection and Curation: Compile a dataset of compounds with reliably measured property data. The quality of the model is directly dependent on the quality of the input data [35]. For properties like blood-brain barrier permeability (BBBp), data is often sourced from public databases and literature, and classified into categories like BBB+ (permeable) and BBB- (impermeable) [1].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute handcrafted molecular descriptors for all compounds. These can include:

- Physicochemical Descriptors: logP (lipophilicity), molecular weight, polar surface area.

- Topological Descriptors: Derived from the molecular graph structure.

- Fingerprints: Predefined structural keys like MACCS keys or ECFP fingerprints [34].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize or standardize the descriptor values to a common scale to prevent models from being biased by descriptors with large numerical ranges.

- Descriptor Optimization (Feature Selection): Identify the most relevant subset of descriptors. This reduces model complexity, mitigates overfitting, and improves interpretability. Techniques can range from genetic algorithms [33] to more modern embedded methods.

- Model Construction: Split the data into a training set (typically 80%) and a test set (20%). Use the training set to build the model with a chosen algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) [1].

- Internal Validation: Assess the model's robustness using the training data. Common techniques include:

- External Validation: This is the most critical step for establishing predictive power. Use the held-out test set, which was not used in training or feature selection, to evaluate the model's performance on new data [31].

- Define Applicability Domain (AD): Characterize the structural and descriptor space of the training set. The model should only be used to predict compounds that fall within this domain to ensure reliability [31].

Protocol: Implementing a Conjoint Fingerprint Approach

This methodology enhances model performance by combining multiple descriptor types.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Generate Multiple Featurizations: For each molecule in the dataset, compute two or more different types of molecular fingerprints. A common and effective pair is MACCS keys (a substructure-based fingerprint) and ECFP (a circular topological fingerprint) [34].

- Create the Conjoint Fingerprint: Concatenate the vectors from the individual fingerprints to form a single, longer feature vector that represents the molecule. This combined vector captures both holistic substructure presence and local atom environment information [34].

- Model Training and Evaluation: Use the conjoint fingerprint vectors as input for machine learning or deep learning models (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks). This approach has been shown to yield improved predictive performance compared to using standalone fingerprints because it harnesses the complementarity of different descriptor types [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and concepts essential for working with handcrafted descriptors in QSPR.

| Tool/Concept | Type | Function in QSPR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCS Keys | Molecular Fingerprint | A set of 166 predefined structural fragments (bits) used to represent a molecule. Provides an interpretable, fixed-length representation suitable for similarity searching and QSAR. | [35] [34] |

| ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint) | Molecular Fingerprint | A topological circular fingerprint that captures atomic neighborhoods. It is excellent for capturing local structural features without a predefined list. | [34] |

| logP | Physicochemical Descriptor | Measures the partition coefficient of a molecule between octanol and water, representing its lipophilicity. A critical descriptor for predicting permeability, absorption, and distribution. | [1] [31] |

| Applicability Domain (AD) | Modeling Framework | Defines the chemical space on which a QSPR model was trained. Predicting compounds outside the AD may lead to unreliable results, making its definition a best practice. | [31] |

| SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) | Model Interpretation Tool | A game-theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model. It quantifies the contribution of each descriptor to an individual prediction, aiding interpretability. | [35] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main strengths of RDKit, Mordred, and DOPtools?

- RDKit: A versatile cheminformatics library excellent for basic molecular manipulation and descriptor calculation. It provides a wide array of built-in descriptors and is a de facto standard in many research areas [36] [37].

- Mordred: A comprehensive descriptor calculation library that computes a vast set of descriptors (2D and 3D), often used for high-throughput screening and complex property prediction [36].

- DOPtools: A specialized Python platform that not only calculates chemical descriptors but also provides a unified API for machine learning libraries like scikit-learn, along with built-in hyperparameter optimization using Optuna. It is especially suited for modeling reaction properties [36] [38].

Q2: I encounter a RuntimeError related to multiprocessing when using Mordred's calc.pandas. How can I resolve this?

This common issue on Windows occurs when the Python multiprocessing library attempts to start new processes before the current one is fully initialized [39]. A reliable workaround is to protect the entry point of your script with if __name__ == '__main__': This ensures the code is executed only when the script is run directly, not when it is imported.

Q3: Can DOPtools handle reactions and complex mixtures, unlike other descriptor libraries? Yes, this is a key advantage of DOPtools. It provides specialized functions for modeling reaction properties. You can calculate descriptors classically (by concatenating descriptors for all reaction components like reactants and products) or by using the Condensed Graph of Reaction (CGR) representation, which encodes the entire reaction as a single graph [36].

Q4: How can I easily calculate all available RDKit descriptors for a molecule?

While RDKit doesn't offer a single built-in function, you can easily create one by iterating through the Descriptors._descList [40].

Q5: Is DOPtools still compatible with Mordred descriptors? As of the most recent update (Version 1.3.7, June 2025), Mordred has been removed as a dependency from DOPtools due to lack of support and dependency issues [41]. If you require Mordred descriptors in your workflow, you will need to calculate them separately and integrate the results manually or use Mordred directly.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling of Hydrogens and Atomic Counts in RDKit

Problem: The GetNumAtoms() method returns fewer atoms than expected because, by default, RDKit only counts "heavy" (non-hydrogen) atoms [37].

Solution:

- Use the

onlyExplicit=Falseparameter to include hydrogen atoms in the count. - If you need to work explicitly with hydrogens in other operations, use the

Chem.AddHs()function to add them to the molecule object.

Issue 2: Integrating Descriptors from Multiple Libraries into a Unified Machine Learning Workflow

Problem: Different descriptor libraries output data in unique formats, making it difficult to create a single, cohesive feature table for machine learning models [36].

Solution: DOPtools is explicitly designed to solve this problem. Its ComplexFragmentor class acts as a scikit-learn compatible transformer that can concatenate features from different sources (e.g., structural descriptors from one column, solvent descriptors from another) into a unified feature table ready for model training [41].

Example configuration for associating different data columns with their feature generators:

Experimental Protocols for Permeability Prediction

Protocol 1: Building a Baseline Model with RDKit Descriptors

This protocol outlines the steps to create a simple yet effective model for membrane permeability prediction using commonly available RDKit descriptors.

- Data Curation: Obtain a dataset of molecules with experimentally measured permeability coefficients (e.g., PAMPA values). Public resources like CycPeptMPDB for cyclic peptides can be used [13].

- Descriptor Calculation: For each molecule SMILES string, calculate a set of relevant physicochemical descriptors. Key descriptors for permeability often include [42] [13]:

- Molecular Weight (

MolWt) - Topological Polar Surface Area (

TPSA) - Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors (

NumHDonors) - Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (

NumHAcceptors) - Octanol-water partition coefficient (

MolLogP)

- Molecular Weight (

- Data Splitting: Split the data into training (80%) and test (20%) sets. For a more rigorous assessment of generalizability, use a scaffold split to separate molecules with different core structures [13].

- Model Training and Validation: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest or Support Vector Machine) on the training set and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (regression) or ROC-AUC (classification) [13].

Protocol 2: Advanced Workflow with DOPtools for Hyperparameter Optimization

This protocol leverages DOPtools' automation capabilities to optimize both the descriptor set and model parameters simultaneously.

- Input Preparation: Prepare a CSV file containing molecule SMILES strings and the corresponding experimental permeability values.

- Configuration: Create a JSON configuration file specifying the types of descriptors to calculate (e.g., RDKit fingerprints, molecular fragments) and the machine learning algorithms to benchmark (e.g., SVM, XGBoost, Random Forest) [36] [41].

- Automated Optimization: Use the DOPtools Command Line Interface (CLI) to launch the optimization process. The library uses the Optuna framework to efficiently search for the best combination of hyperparameters and descriptor types [36].

- Model Interpretation: For models built on fragment descriptors, use the integrated

ColorAtomclass to visualize atomic contributions to the predicted permeability, providing insights into which structural features are favorable or unfavorable [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and their primary function in descriptor-based permeability research.

| Tool/Library Name | Primary Function | Key Application in Permeability Research |

|---|---|---|