Beyond the Molecule: Best Practices in Molecular Representation for Robust ADMET Modeling

Accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is a critical bottleneck in drug discovery.

Beyond the Molecule: Best Practices in Molecular Representation for Robust ADMET Modeling

Abstract

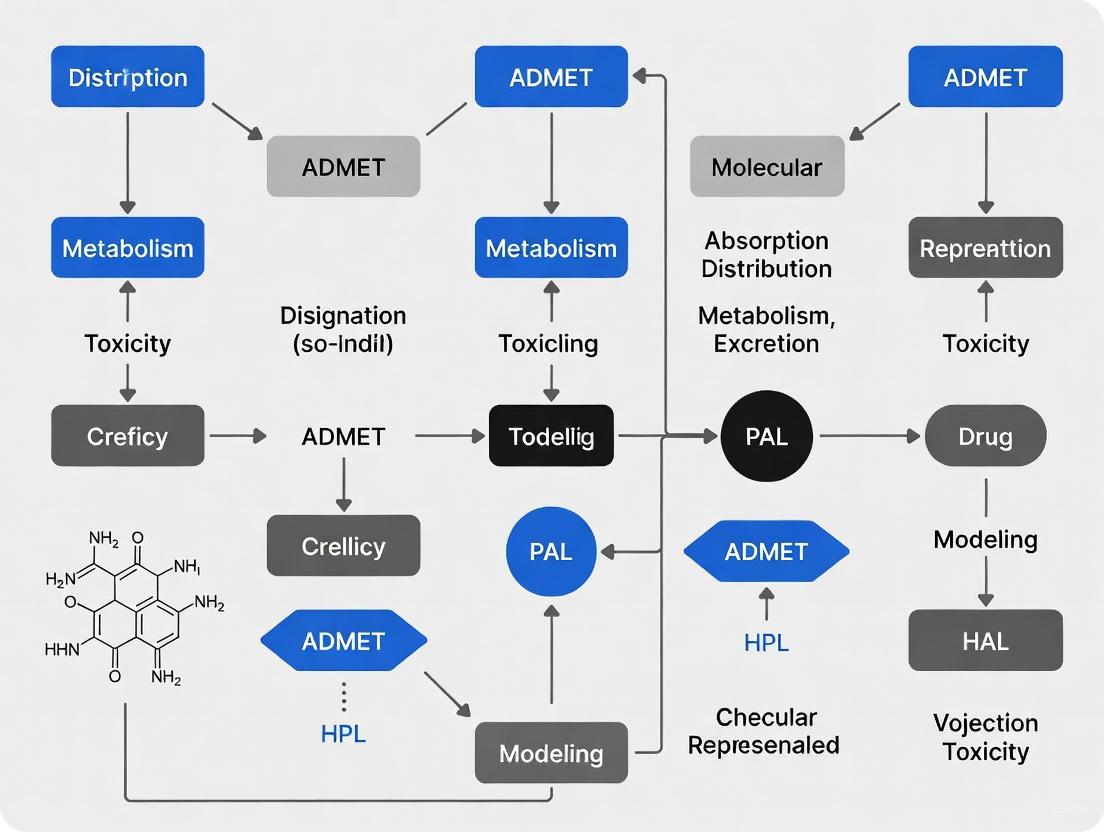

Accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is a critical bottleneck in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the evolving best practices for molecular representation, a cornerstone of reliable ADMET modeling. We explore the journey from traditional descriptors to modern AI-driven embeddings, detail methodological applications of graph neural networks and language models, and address key troubleshooting challenges like data quality and model generalizability. Furthermore, the article outlines rigorous validation frameworks, including community blind challenges and statistical benchmarking, essential for translating computational predictions into real-world drug development success.

From SMILES to Embeddings: The Evolution of Molecular Representation

The Critical Role of Molecular Representation in ADMET Prediction

In the field of drug discovery, the accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is crucial for reducing late-stage attrition and accelerating the development of safer, more effective therapeutics. The foundation of any computational ADMET model lies in how chemical structures are translated into a numerical format that machine learning (ML) algorithms can process—a step known as molecular representation [1]. The choice of representation directly influences a model's ability to capture complex structure-property relationships, its performance on novel chemical scaffolds, and its ultimate utility in real-world drug discovery projects [2] [1].

Despite the emergence of sophisticated deep learning architectures, the selection and justification of molecular representations often remain unsystematic. Many studies prioritize algorithm design, while treating representation as an afterthought, sometimes simply concatenating multiple feature types without clear reasoning [1]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on best practices for molecular representation, provides a structured overview of prevalent representation schemes, their empirical performance, and detailed protocols for their evaluation and application in ADMET modeling research.

Core Molecular Representation Schemes

Molecular representations can be broadly categorized into three groups: classical hand-crafted features, learned embeddings from deep learning models, and hybrid approaches that combine multiple schemes.

Classical Hand-Crafted Representations

These are human-engineered features derived from chemical principles and heuristics.

- Molecular Descriptors: These are numerical values that capture specific physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polar surface area) or topological features of the molecule. Packages like RDKit can generate hundreds of such 2D descriptors [1].

- Structural Fingerprints: These are bit vectors that encode the presence or absence of specific substructures or molecular paths. A common example is the Morgan fingerprint (also known as Circular fingerprints), which captures circular environments around each atom in the molecule up to a specified radius [3] [1]. They are highly effective for similarity searching and are a staple in ligand-based modeling.

Learned Representations

With the advent of deep learning, models can now learn their own feature representations directly from data.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs, such as Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs), directly operate on a molecular graph where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [4] [1]. These models learn to aggregate information from a node's neighbors, creating dense vector embeddings that encapsulate both atomic properties and the overall topological structure. The CLMGraph framework used in admetSAR3.0 is an example of a multi-task GNN that uses contrastive learning for enhanced representations [5].

- Pre-trained Foundation Models: Inspired by natural language processing, some models are pre-trained on massive datasets of chemical structures (e.g., from PubChem and ChEMBL) or quantum mechanical properties [6]. Examples include MolE, MolGPS, and MolMCL [6]. These models generate context-aware embeddings that can be fine-tuned for specific ADMET endpoints. Current evidence suggests their performance is promising but not yet consistently superior to simpler methods, especially when task-specific ADMET data is available [6].

Hybrid and Specialized Representations

To leverage the strengths of different approaches, hybrid methods are increasingly common.

- Descriptor-Augmented Embeddings: This approach combines learned representations with classical descriptors. For instance, Receptor.AI's model integrates Mol2Vec (a Word2Vec-inspired substructure embedding) with curated physicochemical descriptors or a comprehensive set of 2D descriptors from the Mordred library to boost predictive accuracy [7].

- Multi-Task and Federated Representations: Training a single model on multiple ADMET endpoints simultaneously allows the representation to capture underlying biological relationships [8]. Furthermore, federated learning enables the training of models on diverse, distributed proprietary datasets without sharing data, systematically expanding the chemical space the model's representation can learn from and improving its generalizability [8].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

The effectiveness of a representation is highly context-dependent, varying with the specific ADMET endpoint, the chemical space of the dataset, and the model architecture used.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Representation Performance in ADMET Modeling

| Representation Type | Examples | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Performance (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Descriptors | RDKit 2D Descriptors | Intuitive, chemically interpretable, fast to compute | May miss complex, non-linear structural patterns | Often outperformed by fingerprints and GNNs in recent benchmarks [1] |

| Structural Fingerprints | Morgan Fingerprints | Strong performance for similarity, well-established, fast | Hand-crafted nature may limit generalization | Competitive with deep learning methods; outperforms descriptors in many cases [1] [6] |

| Graph Neural Networks | MPNN (e.g., Chemprop), CLMGraph | Learns task-specific features directly from molecular graph | Higher computational cost; "black-box" nature | State-of-the-art on many benchmarks; used in comprehensive platforms like admetSAR3.0 [5] [1] |

| Pre-trained Models | MolE, MolGPS, MolMCL | Potential for transfer learning from vast data | Benefits on ADMET not yet fully consistent | Mixed results in Polaris ADMET challenge; MolMCL (5th place) beat other pre-trained models [6] |

| Hybrid Representations | Mol2Vec + Mordred Descriptors | Combines structural and physicochemical context | Increased feature dimensionality and complexity | Receptor.AI reports highest accuracy with curated hybrid models [7] |

Benchmarking studies reveal that there is no single "best" representation for all tasks. A 2025 benchmarking study concluded that the optimal choice of model algorithm and feature representation is highly dataset-dependent [1]. Furthermore, analysis from the Polaris ADMET competition showed that the relative performance of different modeling approaches (e.g., descriptor-based vs. fingerprint-based) can vary significantly across different drug discovery programs, highlighting the danger of extrapolating results from a single dataset [6].

Experimental Protocols for Representation Evaluation

To establish a robust and reproducible workflow for evaluating molecular representations, researchers should adopt a structured, multi-stage process. The following protocol outlines the key steps from data preparation to model assessment.

Protocol: A Structured Workflow for Evaluating Molecular Representations

Objective: To systematically compare the impact of different molecular representations on the performance of machine learning models for predicting a specific ADMET endpoint.

Step 1: Data Curation and Standardization

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset from reliable public sources (e.g., ChEMBL, TDC, PharmaBench) or in-house assays [9] [1].

- Data Cleaning:

- Standardize Structures: Use tools like the RDKit MolStandardize function or the standardisation tool by Atkinson et al. to canonicalize SMILES, neutralize charges, and handle tautomers [1].

- Remove Inorganics/Salts: Filter out organometallic compounds and inorganic salts. For salt complexes, extract the parent organic compound to ensure consistency [1].

- Deduplicate: For duplicates with consistent measured values, keep the first entry. Remove the entire group of duplicates if the values are inconsistent (e.g., differing binary labels or regression values outside a defined range like 20% of the inter-quartile range) [1].

- Assay Consistency: For public data, be aware of experimental variability. Leveraging LLM-based systems to extract and standardize experimental conditions from assay descriptions is an emerging best practice [9].

Step 2: Data Splitting

To properly assess a model's ability to generalize, it is critical to split the data into training, validation, and test sets using more than one strategy.

- Random Split: The standard approach; randomly assigns compounds to each set. Useful for a baseline assessment.

- Scaffold Split: Splits the data based on molecular scaffolds (Bemis-Murcko framework). This tests the model's performance on entirely novel chemotypes, which is a more realistic and challenging benchmark for drug discovery [1] [6]. The Polaris ADMET competition used a temporal split from a real drug program, which is considered a gold standard for simulating a prospective application [6].

Step 3: Feature Generation

Generate the diverse set of molecular representations to be evaluated. At a minimum, include:

- RDKit 2D Descriptors (normalized) [1]

- Morgan Fingerprints (radius=2, nBits=1024) [3] [1]

- A graph-based representation (e.g., for an MPNN like Chemprop) [1]

- Any relevant pre-trained embeddings (e.g., from MolE or MolMCL) [6]

Step 4: Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

- Algorithm Selection: Train a diverse set of ML algorithms on each representation. This should include both classical methods (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM) and modern deep learning architectures (e.g., MPNNs) [3] [1].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Perform a dataset-specific hyperparameter search for each model and representation combination. This ensures a fair comparison by ensuring each model is performing at its best [1].

Step 5: Rigorous Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate models on the held-out test set using multiple metrics (e.g., Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression, AUC-ROC for classification, and Spearman correlation for ranking) [6].

- Statistical Significance: Move beyond comparing single performance scores. Apply statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., paired t-tests on cross-validation folds) to determine if the performance differences between representation-algorithm pairs are statistically significant [1].

- Applicability Domain: Analyze the model's performance relative to the chemical space of its training data to understand where predictions are most reliable.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Molecular Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics and ML | Core toolkit for generating descriptors (RDKit 2D), Morgan fingerprints, and molecular standardization [3] [1] |

| PharmaBench | Data Benchmark | Curated ADMET dataset | Provides high-quality, standardized data for training and fair benchmarking of different representations [9] |

| TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons) | Data Benchmark | Aggregated ADMET datasets | Offers a leaderboard and diverse datasets to explore representation performance across endpoints [1] |

| Chemprop | Software Library | Deep Learning | Implements Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) for graph-based representation learning [1] |

| admetSAR3.0 | Web Platform | ADMET Prediction & Optimization | Utilizes advanced multi-task GNN (CLMGraph), showcasing state-of-the-art representation learning [5] |

| Apheris Federated Network | Framework | Collaborative Modeling | Enables training representations on diverse, distributed data without centralizing it, expanding chemical coverage [8] |

The critical role of molecular representation in ADMET prediction cannot be overstated. While advanced deep learning and pre-trained models offer exciting avenues, classical fingerprints and structured hybrid approaches remain powerfully competitive. The key to success lies not in seeking a universal "best" representation, but in adopting a rigorous, systematic evaluation protocol that tests multiple representations on the specific chemical space and endpoints of interest. By prioritizing data quality, using scaffold splits for validation, and employing statistical testing, researchers can make informed decisions about molecular representation, thereby building more predictive and reliable ADMET models that accelerate drug discovery.

Application Notes: Performance and Use-Cases in ADMET Modeling

Traditional molecular representation methods remain foundational in cheminformatics, providing robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient features for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Their performance in conjunction with classical machine learning models is highly competitive, often matching or surpassing more complex deep learning approaches. [10] [11] [12]

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The following tables summarize the performance of traditional representations across various predictive modeling tasks, including ADMET and odor perception, highlighting their versatility.

Table 1: Performance of Molecular Representations with Different Machine Learning Models on Odor Prediction Tasks (AUROC) [13]

| Feature Set | Random Forest (RF) | eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | 0.784 | 0.828 | 0.810 |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | 0.743 | 0.802 | 0.769 |

| Functional Group (FG) | 0.697 | 0.753 | 0.723 |

Table 2: Top-Performing Fingerprint Combinations for Different Task Types [14]

| Task Type | Best Single Fingerprint | Performance (Single) | Best Fingerprint Combination | Performance (Combined) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | ECFP / RDKit | Avg. AUC: 0.830 | ECFP + RDKit | Avg. AUC: 0.843 |

| Regression | MACCS | Avg. RMSE: 0.587 | MACCS + EState | Avg. RMSE: 0.549 |

Table 3: Key Traditional Molecular Representations and Their Characteristics [10] [15] [11]

| Representation Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Common Applications in ADMET |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | RDKit Descriptors, Mordred Descriptors | Numeric vectors describing physicochemical properties (e.g., MolWt, LogP, TPSA). Provide detailed, interpretable features. [10] [15] | Predicting physical properties (e.g., solubility); often well-suited for regression tasks. [11] [14] |

| Structural Fingerprints | MACCS, PubChem Fingerprints | Binary structural keys based on predefined substructures or functional groups. Simple and efficient. [10] [16] | Broad applicability in classification and similarity searching; MACCS excels in some regression tasks. [14] |

| Topological Fingerprints | Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) | Capture atom environments and molecular connectivity through a circular hashing algorithm. Excellent for capturing structure-activity relationships. [13] [15] [11] | High performance in activity classification, toxicity prediction, and virtual screening. [13] [12] |

Key Insights for ADMET Modeling

- Model and Algorithm Selection: Gradient-boosted decision tree algorithms, particularly XGBoost, consistently demonstrate top-tier performance when paired with traditional representations like fingerprints and descriptors. [10] [13] [12] Their ability to handle sparse, high-dimensional data and capture non-linear relationships makes them ideally suited for this domain.

- Strategic Fingerprint Selection: The optimal choice of fingerprint is often task-dependent. For classification tasks, ECFP and RDKit fingerprints provide detailed discriminative power, while for regression tasks, simpler fingerprints like MACCS may capture the most relevant continuous relationships. [14]

- Complementary Nature of Features: While combining different feature representations (e.g., multiple fingerprint types or fingerprints with descriptors) does not always yield dramatic improvements, strategic combinations can enhance model performance and robustness. [12] For instance, pairing ECFP with ErG, Avalon fingerprints, and molecular properties has been shown to be effective. [12]

Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing traditional molecular representations in predictive ADMET workflows.

Protocol 1: Featurization of Small Molecules using Descriptors and Fingerprints

Application Note: This protocol describes the generation of expert-based molecular feature vectors from SMILES strings, forming the basis for training machine learning models in ADMET prediction.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 4 in Section 3.0 for a complete list of software and libraries.

Procedure:

- Input and Standardization:

- Provide a list of small molecules as canonical SMILES strings.

- Standardize the molecular structure using RDKit, including steps such as sanitization, neutralization, and removal of salts.

Compute Molecular Descriptors:

- Utilize the RDKit or PaDEL-Descriptor software to calculate a comprehensive set of numerical descriptors. [15] [11]

- Common descriptors include molecular weight (MolWt), topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP), and count of rotatable bonds.

- Normalize the resulting descriptor vector (e.g., Z-score normalization) to ensure features are on a comparable scale.

Generate Molecular Fingerprints:

- ECFP (e.g., ECFP4):

- Using RDKit, set the radius parameter (often 2 for ECFP4) and the final bit vector length (e.g., 2048).

- The algorithm iteratively captures circular atom neighborhoods, hashing them into a fixed-length bit vector. [13]

- MACCS Keys:

- Generate a 166-bit binary fingerprint based on the presence or absence of 166 predefined structural fragments. [10]

- Other Fingerprints:

- ECFP (e.g., ECFP4):

Data Output:

- The final output is a feature matrix (samples x features) containing combined or individual descriptor and fingerprint vectors, ready for model training.

Protocol 2: Building an XGBoost Model for ADMET Classification

Application Note: This protocol outlines the training and evaluation of an XGBoost classifier, a top-performing model, using molecular features for a binary ADMET endpoint (e.g., hERG inhibition, CYP450 substrate).

Materials:

- Feature matrix and corresponding binary labels from Protocol 1.

- Python environment with

scikit-learn,xgboost, andnumpylibraries.

Procedure:

- Data Partitioning:

- Split the dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) sets using a scaffold split, which groups molecules based on core Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This evaluates the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes, simulating a real-world scenario. [10]

Hyperparameter Optimization:

- Perform a randomized grid search with 5-fold cross-validation on the training set.

- Fine-tune key XGBoost parameters as listed in Table 5. [10]

Model Training:

- Train the final XGBoost model on the entire training set using the optimal hyperparameters identified in the previous step.

Model Evaluation:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Software and Libraries for Traditional Molecular Representation [10] [15] [11]

| Item Name | Type/Package | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Library | Core cheminformatics toolkit; used for reading SMILES, calculating descriptors, and generating fingerprints (ECFP, MACCS). [10] [13] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Calculates a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors and fingerprints directly from structures. [11] |

| Python Scikit-learn | Library | Provides standard machine learning algorithms, data splitting, preprocessing, and model evaluation tools. |

| XGBoost | Library | Implements the gradient boosting algorithm, a top-performing model for structured/tabular data like fingerprints and descriptors. [10] [13] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Python Library/Resource | Provides curated, benchmark ADMET datasets with predefined training/test splits for fair model evaluation. [10] |

Table 5: Key XGBoost Hyperparameters for Optimization [10]

| Hyperparameter | Description | Typical Search Values |

|---|---|---|

n_estimators |

Number of gradient boosted trees. | [50, 100, 200, 500, 1000] |

max_depth |

Maximum depth of a tree, controls model complexity. | [3, 4, 5, 6, 7] |

learning_rate |

Step size shrinkage to prevent overfitting. | [0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3] |

subsample |

Fraction of instances used for training each tree. | [0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0] |

colsample_bytree |

Fraction of features used for training each tree. | [0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0] |

reg_alpha |

L1 regularization term on weights. | [0, 0.1, 1, 5, 10] |

reg_lambda |

L2 regularization term on weights. | [0, 0.1, 1, 5, 10] |

The evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) has ushered in a transformative era for molecular representation in drug discovery, shifting from predefined, rule-based features to data-driven learning paradigms. Modern AI-driven approaches leverage deep learning models to directly extract and learn intricate features from molecular data, enabling a more sophisticated understanding of molecular structures and their properties, particularly for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction. These methods have emerged as pivotal tools for managing intricate data landscapes and have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across various tasks, including new drug design, drug target identification, and molecular property profiling. The adaptability of pre-trained AI models renders them indispensable assets for driving data-centric advancements, furnishing a robust framework that expedites innovation and discovery. The integration of these technologies throughout the drug discovery process enables improved predictive accuracy, reduced development costs, and decreased late-stage failures, addressing the critical bottleneck that ADMET evaluation represents in the drug development pipeline.

Table 1: Core AI Architectures for Molecular Representation

| Architecture | Core Representation | Key Strengths | Primary ADMET Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) | Naturally captures molecular topology and structural relationships [17] | Property prediction, toxicity assessment, interaction analysis [17] |

| Transformers | Sequential tokens (e.g., from SMILES) or graph nodes | Captures long-range, hierarchical dependencies in data [18] | Drug-target identification, virtual screening, lead optimization [18] |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Latent space vectors (compressed molecular representation) | Enables generative design and exploration of chemical space [15] [19] | De novo molecular design, scaffold hopping [15] [19] |

Application Notes: AI Methods in ADMET Modeling

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Molecular Property Prediction

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have revolutionized drug design processes by accurately modeling molecular structures and interactions with binding targets. Over the past five years, GNNs have emerged as transformative tools by accurately modeling molecular structures and their interactions. These networks operate by representing molecules as graphs where atoms serve as nodes and bonds as edges, allowing the model to natively capture the structural topology of compounds. This representation is particularly advantageous for ADMET modeling as it directly mirrors how chemists perceive molecular structure and reactivity. Breakthroughs in predicting molecular properties, drug repurposing, toxicity assessment, and interaction analysis have significantly sped up drug discovery.

GNN-driven innovations improve predictive accuracy by learning from both local atomic environments and global molecular structure. The message-passing mechanism in GNNs allows atoms to aggregate information from their neighbors, creating increasingly sophisticated representations of molecular substructures. This capability is crucial for predicting ADMET endpoints that often depend on specific functional groups or structural motifs. Furthermore, generative GNNs are enhancing virtual screening and novel molecule design, expanding the available chemical space for drug discovery while prioritizing compounds with favorable ADMET profiles.

Transformer Architectures for Chemical Language Understanding

Transformer models have emerged as pivotal tools within the realm of drug discovery, distinguished by their unique architectural features and exceptional performance in managing intricate data landscapes. These models leverage self-attention mechanisms to process sequential molecular representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) or SELFIES, treating them as a specialized chemical language. This approach allows transformers to capture complex, long-range dependencies within the molecular structure that might be challenging for other architectures to recognize.

The adaptability of pre-trained transformer-based models renders them indispensable assets for driving data-centric advancements in drug discovery. These models can be fine-tuned for specific ADMET endpoints with relatively small datasets, leveraging knowledge gained during pre-training on large, diverse chemical libraries. Transformer architectures have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across various tasks, including protein design, molecular dynamics simulation, drug target identification, virtual screening, and lead optimization. Their ability to comprehend intricate hierarchical dependencies inherent in sequential data makes them particularly valuable for understanding metabolic pathways and toxicity mechanisms.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for Molecular Generation and Optimization

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) represent a powerful class of deep generative models that learn a compressed, continuous latent representation of molecular structures. Unlike GNNs and Transformers that are primarily used for predictive modeling, VAEs excel at generating novel molecular structures with desired properties, making them particularly valuable for scaffold hopping and de novo drug design. In the context of ADMET optimization, VAEs can be trained to generate molecules that maintain target activity while improving specific pharmacokinetic or safety profiles.

The VAE framework consists of an encoder that maps molecules to a latent space and a decoder that reconstructs molecules from points in this space. By sampling from the latent space and decoding these points, researchers can generate new molecular structures not present in the original training data. When combined with property prediction models, this capability enables directed exploration of chemical space toward regions with improved ADMET characteristics. VAEs have shown particular promise in scaffold hopping—discovering new core structures while retaining similar biological activity—which is crucial for overcoming toxicity issues or patent limitations associated with existing lead compounds.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI Representations on ADMET Endpoints

| Model Type | Solubility Prediction (RMSE) | hERG Inhibition (AUC-ROC) | Metabolic Stability (Accuracy) | CYP450 Inhibition (AUC-ROC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNNs (Graphormer) | 0.68 [20] | 0.83 [17] | 78.5% [17] | 0.81 [17] |

| SMILES Transformers | 0.72 [18] | 0.81 [18] | 76.2% [18] | 0.79 [18] |

| VAE-based Models | 0.75 [15] | 0.78 [19] | 74.8% [19] | 0.77 [19] |

| Traditional ML | 0.85 [21] | 0.75 [21] | 72.1% [21] | 0.72 [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pretraining Graph Transformers with Quantum Mechanical Properties

Application Note: This protocol describes a methodology for pretraining Graph Transformer architectures on atom-level quantum-mechanical (QM) features to enhance performance in downstream ADMET modeling tasks. This approach leverages fundamental physical information to learn more meaningful molecular representations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Software: Custom Graphormer implementation [20], RDKit library, quantum chemistry calculation packages (e.g., for GFN2-xtb and DFT calculations)

- Datasets: Publicly available dataset of ~136k organic molecules with optimized geometries and computed atomic properties (charge, Fukui indices, NMR shielding constants) [20]

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Generate 2D molecular graphs from the dataset, representing atoms as nodes and bonds as edges.

- Extract atom-level quantum mechanical properties for each non-hydrogen atom in the molecules.

- Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets (recommended ratio: 80:10:10).

Model Pretraining:

- Implement a Graphormer architecture with 20 hidden layers to study pretraining effects on deep models.

- Configure the model for multi-task regression of atomic properties.

- Train the model using mean squared error loss between predicted and actual QM properties.

- Use the Adam optimizer with learning rate of 0.0001 and batch size of 32.

Model Fine-tuning:

- Select downstream ADMET tasks from Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) benchmarks.

- Replace the pretraining head with task-specific output layers.

- Fine-tune the entire model on the ADMET dataset with reduced learning rate (20-50% of pretraining rate).

- Employ early stopping based on validation performance to prevent overfitting.

Model Evaluation:

- Evaluate model performance on held-out test sets for each ADMET endpoint.

- Compare against baselines including randomly initialized models and models pretrained with other strategies (e.g., molecular-level properties or self-supervised atom masking).

- Analyze latent representations to verify preservation of pretraining information.

Troubleshooting:

- If model fails to converge during pretraining, verify the quality and distribution of QM properties.

- For overfitting during fine-tuning, implement stronger regularization or reduce model complexity.

- If performance gains are minimal, ensure sufficient similarity between pretraining data and downstream tasks.

Protocol 2: Cross-Pharma Federated Learning for ADMET Modeling

Application Note: This protocol outlines the implementation of federated learning across multiple pharmaceutical organizations to collaboratively train ADMET models without sharing proprietary data. This approach addresses data scarcity and diversity limitations that often constrain model generalizability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Hardware: Distributed computing infrastructure with secure communication channels

- Software: Apheris Federated Learning Platform or equivalent, kMoL open-source library [8]

- Datasets: Distributed proprietary ADMET datasets from participating pharmaceutical companies

Procedure:

- Network Setup:

- Establish a secure federated learning network with complete data governance for each participant.

- Define consensus model architecture (typically multi-task GNN or Transformer).

- Implement cryptographic protocols for secure model aggregation.

Data Harmonization:

- Each participant performs internal data curation and normalization.

- Map heterogeneous assay data to standardized ADMET endpoints.

- Apply scaffold-based splitting to ensure realistic evaluation.

Federated Training Cycle:

- Step 1: Central server initializes global model and shares with all participants.

- Step 2: Each participant trains the model locally on their proprietary data for a specified number of epochs.

- Step 3: Participants send model updates (gradients or parameters) to the secure aggregator.

- Step 4: Aggrator computes weighted average of model updates using federated averaging.

- Step 5: Updated global model is distributed back to participants.

- Repeat steps 2-5 until convergence.

Model Validation:

- Each participant evaluates the federated model on their local hold-out test sets.

- Compare performance against locally-trained baselines.

- Assess model applicability domain and performance on novel scaffolds.

Troubleshooting:

- If model divergence occurs, reduce learning rate or implement stricter update clipping.

- For participation imbalance, implement appropriate weighting strategies in aggregation.

- If communication overhead is excessive, increase local computation between aggregations.

Protocol 3: VAE-Based Scaffold Hopping with Activity Retention

Application Note: This protocol describes the use of Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for scaffold hopping in lead optimization, aiming to discover novel core structures while maintaining desired biological activity and improving ADMET properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Hardware: GPU-accelerated workstations

- Software: VAE implementation with property prediction heads, RDKit, molecular docking software

- Datasets: Curated set of active compounds with associated biological activity and ADMET data

Procedure:

- Model Training:

- Train a VAE on a diverse collection of drug-like molecules represented as SMILES strings or molecular graphs.

- Incorporate property prediction heads for activity and key ADMET endpoints.

- Use a combined loss function: reconstruction loss + KL divergence + property prediction loss.

Latent Space Exploration:

- Encode known active compounds with undesirable ADMET properties into the latent space.

- Identify directions in latent space that correlate with improved ADMET profiles.

- Sample points along these directions while remaining near activity-preserving regions.

Molecular Generation:

- Decode sampled latent points to generate novel molecular structures.

- Apply chemical validity checks and synthetic accessibility filters.

- Use property predictors to prioritize generated compounds with improved ADMET profiles.

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top-ranked compounds for experimental testing.

- Evaluate maintained target activity and improved ADMET properties.

- Iterate based on experimental results to refine the generative model.

Troubleshooting:

- If generated molecules are chemically invalid, adjust decoder architecture or use alternative representations like SELFIES.

- For lack of diversity in generated compounds, increase the weight of KL divergence in the loss function.

- If activity is not maintained, strengthen the property prediction loss for the target activity.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AI-Driven ADMET Modeling

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Repository | Provides curated benchmark datasets for ADMET modeling [20] | Public |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and handles molecular conversions [20] | Open Source |

| Graphormer | Software Library | Implements graph transformer architectures for molecular property prediction [20] | Open Source |

| PCQM4Mv2 Dataset | Quantum Chemical Dataset | Provides HOMO-LUMO gaps and other quantum properties for pretraining [20] | Public |

| Apheris Federated Platform | Software Platform | Enables secure cross-pharma collaborative learning without data sharing [8] | Commercial |

| OpenADMET Datasets | Experimental Data | Provides high-quality, consistently generated ADMET data for model training [2] | Public |

Best Practices and Implementation Guidelines

The implementation of AI-driven molecular representations in ADMET modeling requires careful consideration of several factors to ensure robust and generalizable performance. First, data quality and consistency are paramount—models trained on heterogeneous, low-quality data show poor correlation and generalizability. Initiatives like OpenADMET that generate consistent, high-quality experimental data specifically for model development are crucial for advancing the field. Second, the choice of pretraining strategy significantly impacts downstream performance. Pretraining on fundamental molecular properties, such as quantum mechanical features, provides models with a strong physical basis that enhances performance on ADMET endpoints with limited data.

For optimal results, researchers should:

- Implement scaffold-based splitting rather than random splitting when evaluating model performance to better simulate real-world application on novel chemotypes.

- Consider federated learning approaches when possible to leverage diverse chemical space coverage without compromising proprietary data.

- Apply multi-task learning strategically for related ADMET endpoints to leverage shared underlying mechanisms while being mindful of potential negative transfer between unrelated tasks.

- Regularly participate in blind challenges such as those offered by Polaris and OpenADMET to objectively assess model performance on prospective compound series.

The field continues to evolve with promising research directions including explainable AI (XAI) for model interpretation, uncertainty quantification for reliable prediction confidence, and multi-scale modeling that integrates structural information with higher-order biological data. As these technologies mature, they hold the potential to substantially improve drug development efficiency and reduce the current 40-45% clinical attrition rate attributed to ADMET liabilities.

Modern drug discovery is an exceptionally complex and costly endeavor, often requiring over a decade and investments exceeding $1-2 billion to bring a single new therapeutic to market [22]. Despite these substantial investments, the pharmaceutical industry continues to face staggering failure rates, with more than 90% of drug candidates failing during clinical development, frequently due to efficacy, safety, or poor pharmacokinetic profiles [22]. A significant proportion of these failures—approximately 10-15%—are directly attributable to unfavorable biopharmaceutical properties, including poor solubility, limited permeability, or extensive metabolism [22].

Traditional drug discovery methods, which often relied on serendipitous findings and non-systematic approaches, are increasingly proving inadequate to address the multifaceted challenges of contemporary drug development [23]. These conventional approaches, including random screening, trial-and-error methods, and ethnopharmacology, emerged before the current understanding of molecular targets and systems pharmacology [24] [23]. While these methods successfully identified foundational therapeutics like penicillin and quinine, they operate without the target-specific knowledge and predictive capabilities that modern drug discovery demands [23].

The limitations of these traditional paradigms have become particularly pronounced in the critical area of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction, where inadequate molecular representation and forecasting methods contribute significantly to late-stage attrition [21] [7]. This application note examines the specific shortcomings of traditional drug discovery approaches and contrasts them with emerging computational strategies, providing structured experimental protocols and quantitative comparisons to guide researchers toward more effective molecular representation in ADMET modeling.

Key Limitations of Traditional Drug Discovery Methods

Fundamental Methodological Shortcomings

Traditional drug discovery approaches are characterized by several inherent limitations that restrict their efficiency and success rates in modern pharmaceutical development:

High Resource Consumption: Traditional in vitro or in vivo target discovery methods are notoriously time-consuming and labor-intensive, creating significant bottlenecks that limit the pace of drug discovery [25]. The experimental burden of standard ADMET assessment methods, including cell-based permeability and metabolic stability studies, makes them difficult to scale for high-throughput workflows [7].

Lack of Target Specificity: Traditional methods often function without prior identification of drug targets, focusing instead on measuring complex phenotypic responses in vivo rather than targeted molecular interactions [23]. This approach, while sometimes successful in identifying active compounds, provides limited mechanistic understanding of drug action.

High Attrition Rates: The failure to adequately predict ADMET properties contributes significantly to drug candidate attrition. Issues with solubility, permeability, transporter-mediated efflux, and extensive metabolism account for approximately 10-15% of clinical failures [22].

Insufficient Exploration of Chemical Space: Methods like random screening and trial-and-error are inherently limited in their ability to navigate the vast, nearly infinite chemical space of potential drug candidates [15]. These approaches typically examine only a tiny fraction of possible compounds and scaffolds.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Traditional and Modern Drug Discovery Methods

| Characteristic | Traditional Methods | Modern Computational Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification Timeline | Months to years [25] | Days to weeks [25] |

| Chemical Space Exploration | Limited by experimental throughput [15] | Virtually unlimited via in silico screening [15] |

| ADMET Prediction Accuracy | Moderate (species-specific bias) [7] | High (improving with larger datasets) [26] [7] |

| Resource Requirements | High (specialized equipment, reagents) [21] | Lower (computational infrastructure) [21] |

| Success Rate | Low (<12% clinical approval) [22] | Potentially higher with better prediction [21] [22] |

| Scalability | Limited by experimental throughput [7] | Highly scalable with computing power [15] |

Molecular Representation in ADMET Modeling: From Traditional to AI-Driven Approaches

Evolution of Molecular Representation Methods

The representation of molecular structures has evolved significantly from traditional rule-based approaches to contemporary data-driven paradigms:

Traditional Molecular Representations: Early approaches relied on simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings, molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity), and molecular fingerprints that encode substructural information as binary strings or numerical values [15]. While computationally efficient, these representations often struggle to capture the intricate relationships between molecular structure and biological activity [15].

Modern AI-Driven Representations: Recent advancements employ deep learning techniques including graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformers to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from complex datasets [15]. These approaches capture both local and global molecular features, enabling more accurate predictions of ADMET properties and biological activity [15].

Impact on ADMET Prediction Performance

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representation Methods in ADMET Prediction

| Representation Method | Prediction Accuracy Range | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | 60-75% [26] | Interpretable, computationally efficient [15] | Limited representation capability [15] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | 65-80% [26] | Fast similarity searching [24] | Predefined features limit novelty [15] |

| Graph Neural Networks | 75-90% [15] [26] | Capture structural relationships [15] | Higher computational demands [15] |

| Transformer-based Models | 80-92% [15] | Context-aware representations [15] | Extensive data requirements [15] |

| Multimodal Representations | 85-94% [15] [26] | Integrate multiple data types [15] | Complex implementation [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Molecular Representation Methods

Protocol 1: Benchmarking ADMET Prediction Models

Purpose: To systematically evaluate and compare the performance of different molecular representation methods for predicting key ADMET properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset Sources: Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) ADMET datasets, ChEMBL, PubChem [26]

- Software Tools: RDKit for descriptor calculation, DeepLearning libraries (PyTorch/TensorFlow), scikit-learn for traditional ML [26]

- Computational Resources: Workstation with GPU acceleration (recommended: NVIDIA RTX 3080 or equivalent) [21]

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Curation:

- Obtain standardized ADMET datasets from public repositories (e.g., TDC) [26]

- Apply rigorous data cleaning: remove duplicates, standardize SMILES representations, address measurement inconsistencies [26]

- Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain distribution of key properties [26]

Feature Generation:

Model Training and Validation:

- Implement multiple algorithm classes: Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, Gradient Boosting, and Deep Neural Networks [21] [26]

- Perform hyperparameter optimization using Bayesian optimization or grid search [26]

- Validate using nested cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing to assess significance of performance differences [26]

Performance Assessment:

- Evaluate models on hold-out test sets using metrics appropriate for task type (AUC-ROC for classification, RMSE for regression) [26]

- Conduct external validation using datasets from different sources to assess generalizability [26]

- Perform error analysis to identify patterns in prediction failures [26]

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables quantitative comparison of different molecular representation approaches, identifying optimal strategies for specific ADMET endpoints and providing insights into the trade-offs between model complexity, interpretability, and predictive accuracy [26].

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of In Silico ADMET Predictions

Purpose: To validate computational ADMET predictions using established in vitro assays.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Lines: Caco-2 cells for permeability assessment, HEK293 cells transfected with specific transporters, primary hepatocytes for metabolism studies [22] [7]

- Assay Kits: CYP450 inhibition screening kits, MTT cell viability assay kits, hERG inhibition assay kits [7]

- Analytical Equipment: LC-MS/MS systems for quantitative analysis, fluorescence plate readers, automated patch clamp systems for hERG screening [7]

Procedure:

- Compound Selection:

In Vitro Assay Execution:

- Permeability Assessment: Culture Caco-2 cells for 21-24 days to form differentiated monolayers, measure apparent permeability (Papp) of test compounds [22]

- Metabolic Stability: Incubate compounds with human liver microsomes or hepatocytes, quantify parent compound depletion over time [7]

- Transporter Interactions: Assess P-glycoprotein and BCRP substrate potential using transfected cell lines [22]

- Toxicity Screening: Conduct hERG inhibition assays using patch clamp or fluorescence-based methods, perform hepatotoxicity assessment in HepG2 cells [7]

Data Correlation Analysis:

Expected Outcomes: This validation protocol establishes the real-world performance of computational ADMET models, builds confidence in their predictive capability, and identifies areas requiring model improvement [26] [7].

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Traditional vs. Modern Drug Discovery Workflow

Molecular Representation Evolution in ADMET Modeling

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Method Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, DeepChem [26] | Molecular descriptor calculation and cheminformatics | Open-source, extensive descriptor libraries, Python-based |

| AI/ML Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, scikit-learn [21] [26] | Model development and training | Flexible architectures, GPU acceleration, comprehensive algorithms |

| ADMET Databases | TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons), ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [21] [26] | Training data for predictive models | Curated ADMET endpoints, standardized formats, large compound sets |

| In Vitro Assay Systems | Caco-2 cells, transfected cell lines, human hepatocytes [22] [7] | Experimental validation of predictions | Biologically relevant, standardized protocols, regulatory acceptance |

| Molecular Representation Libraries | Mol2Vec, GraphConv, Transformer models [15] [7] | Advanced feature extraction | Learned representations, context-aware, structure-informed |

The limitations of traditional drug discovery methods are no longer acceptable in an era of precision medicine and increasingly complex therapeutic targets. The high resource consumption, limited target specificity, insufficient chemical space exploration, and inadequate ADMET prediction capabilities of these approaches contribute significantly to the unsustainable attrition rates in pharmaceutical development [25] [22].

Modern computational strategies, particularly AI-driven molecular representation methods, offer a transformative path forward. By leveraging graph neural networks, transformer models, and multimodal learning, these approaches enable more accurate prediction of ADMET properties, facilitate navigation of broader chemical spaces, and support rational drug design [15]. The integration of these advanced computational methods with targeted experimental validation creates a synergistic framework that addresses the fundamental limitations of traditional approaches.

For researchers engaged in molecular representation for ADMET modeling, the adoption of these modern methodologies is essential for improving prediction accuracy, reducing late-stage attrition, and ultimately enhancing the efficiency of the drug discovery pipeline. The protocols and analyses presented in this application note provide a foundation for implementing these advanced approaches and transitioning from traditional limitations to contemporary solutions in pharmaceutical research and development.

The pursuit of novel chemical entities in drug discovery is perpetually challenged by the need to balance structural innovation with favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. Scaffold hopping, the strategic replacement of a molecule's core structure to generate novel chemotypes while retaining biological activity, serves as a critical methodology for overcoming intellectual property constraints and optimizing drug-like properties [27] [28]. The success of this endeavor is fundamentally constrained by a single factor: the effectiveness of molecular representation. The chosen representation dictates a model's ability to capture the essential features of molecular structure and bioactivity, thereby enabling accurate navigation through the vast and complex landscape of chemical space [29]. Within the context of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) modeling, the challenge is magnified; representations must not only preserve pharmacophoric elements but also encode the intricate structural features that dictate metabolic fate and toxicological outcomes [30]. This application note details the protocols and best practices for leveraging advanced molecular representations to bridge the gap between scaffold hopping initiatives and reliable ADMET prediction, thereby de-risking the exploration of novel chemical space.

Foundational Concepts and Best Practices

The Critical Role of Molecular Representation

Molecular representation acts as the foundational language for all computational drug discovery tasks. An effective representation translates a chemical structure into a numerical or graphical format that machine learning algorithms can process, directly influencing the model's ability to recognize patterns and make accurate predictions [29] [31]. The relationship between representation and scaffold hopping is symbiotic; a high-quality representation allows for the identification of structurally diverse yet functionally equivalent cores, which is the very definition of a successful hop [27].

In the specific context of ADMET modeling, representations must be particularly adept at capturing features relevant to pharmacokinetics and toxicity. This includes, but is not limited to, surface electrostatics, hydrogen bonding potential, and the presence of specific functional groups or substructures known to interact with metabolic enzymes such as the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) family [30]. Graph-based representations, which naturally model atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, have emerged as a powerful standard because they explicitly encode the connectivity and topology of a molecule, providing a rich feature set for deep learning models [30].

Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

Scaffold hopping is not a monolithic technique but encompasses a spectrum of strategies characterized by the degree of structural alteration. Understanding this classification is vital for selecting the appropriate computational tools and representations.

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

| Hop Degree | Description | Key Techniques | Impact on Novelty & Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° (Heterocycle Replacements) | Minor modifications, such as swapping carbon and heteroatoms in a ring. | Bioisosteric replacement, heterocycle swapping. | Low structural novelty; high probability of retaining biological activity. |

| 2° (Ring Opening/Closure) | More extensive changes involving the breaking or formation of ring systems. | Ring opening, ring closure, ring fusion. | Medium structural novelty; requires careful conformational analysis to maintain pharmacophore alignment. |

| Topology-Based Hopping | Significant alterations to the molecular graph topology. | Pharmacophore-based searching, shape-based alignment. | High structural novelty; higher risk of losing activity, but potential for major IP advantages. |

The trade-off between the degree of structural novelty and the success rate of maintaining biological activity is a central consideration [27]. Small-step hops (1°) frequently succeed but may offer limited intellectual property advantages, whereas large-step, topology-based hops can yield breakthrough novel chemotypes but carry a higher risk of attrition [27]. The workflow for a scaffold hopping campaign, from lead identification to the final optimized compound with improved properties, can be visualized as a structured process.

Diagram 1: A generalized scaffold hopping workflow for lead optimization.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Graph-Based Molecular Representation for CYP Inhibition Prediction

Objective: To construct a predictive model for CYP inhibition using graph-based representations, enabling the evaluation of novel scaffolds for metabolic liability early in the design cycle.

Background: CYP enzymes, including CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, are responsible for metabolizing a vast majority of clinically used drugs. Predicting inhibition is crucial for avoiding drug-drug interactions [30]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) naturally represent molecular structure and have shown superior performance in modeling these complex interactions.

Materials & Reagents:

- Dataset: Curated CYP inhibition data from sources like the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [32] [30].

- Software: Python libraries including PyTorch or TensorFlow, and deep learning libraries for GNNs (e.g., PyTor Geometric, DGL).

- Computing: A GPU-enabled computing environment is recommended for efficient model training.

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Assemble a dataset of molecular structures (as SMILES strings) with corresponding binary or continuous CYP inhibition values.

- Apply standard data cleaning: remove duplicates, handle missing values, and check for activity cliff compounds.

- Partition the data into training, validation, and test sets using a temporal or scaffold-based split to better simulate real-world predictive performance [2].

Molecular Graph Construction:

- Convert each SMILES string into a molecular graph.

- Nodes (Atoms): Encode using features such as atom type (one-hot encoding), degree, hybridization, formal charge, and aromaticity.

- Edges (Bonds): Encode using features such as bond type (single, double, triple, aromatic), conjugation, and stereochemistry.

Model Training with a Graph Neural Network:

- Implement a GNN architecture such as a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Graph Attention Network (GAT). The attention mechanism in GATs can help in interpreting important substructures [30].

- The model learns to generate a dense vector representation (embedding) for each molecule by iteratively aggregating information from neighboring atoms and bonds.

- Feed the final graph embedding into a fully connected layer for the binary (inhibitor/non-inhibitor) or regression (inhibition potency) task.

- Train the model using a suitable loss function (e.g., Binary Cross-Entropy) and optimizer (e.g., Adam).

Model Validation and Interpretation:

- Evaluate the trained model on the held-out test set using metrics like AUC-ROC, precision-recall, and F1-score.

- Employ Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as analyzing attention weights or using methods like GNNExplainer, to identify which atoms or substructures the model deems critical for CYP inhibition. This provides actionable insights for medicinal chemists to design away from metabolic hotspots [30].

Protocol: Implementing a Scaffold Hopping Workflow with 3D Pharmacophore Alignment

Objective: To replace a central scaffold with a novel core while conserving the spatial orientation of key functional groups critical for target binding and ADMET properties.

Background: This protocol leverages the concept that bioactivity is often determined by the 3D arrangement of pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups) rather than the 2D molecular backbone [27]. This is exemplified by the historical transformation of the rigid morphine into the more flexible tramadol, where key pharmacophore features were conserved despite significant 2D structural differences [27].

Materials & Reagents:

- Software: Molecular docking software (e.g., Schrödinger, MOE), pharmacophore modeling tools (e.g., MOE, Phase), and scaffold hopping software (e.g., ReCore, BROOD, Spark) [28].

- Input Structure: A high-quality 3D structure of the lead compound, ideally from a protein-ligand co-crystal structure.

Procedure:

- Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Based on the co-crystal structure or a well-docked pose of the lead molecule, identify the essential pharmacophoric elements that interact with the protein target.

- Define the geometric constraints (distances, angles) between these features to create a 3D pharmacophore query.

Database Search and Core Replacement:

- Using scaffold hopping software (e.g., ReCore), specify the scaffold region of the lead molecule to be replaced.

- The algorithm will search a database of ring fragments to identify novel cores that can geometrically satisfy the attachment points for the existing substituents (R-groups).

- The output is a list of proposed novel compounds with replaced scaffolds.

3D Conformational Alignment and Validation:

- Generate low-energy 3D conformers for the top proposed compounds.

- Superimpose these conformers onto the original pharmacophore model to ensure critical features are maintained. Tools like the Flexible Alignment in Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) are designed for this task [27].

- A successful hop, as seen in the Roche BACE-1 inhibitor example, will show a high degree of overlap for the key pharmacophore points and the retained substituents, even if the connecting core is entirely different [28].

In Silico ADMET Profiling:

- Subject the proposed compounds to predictive ADMET models, such as those for solubility, permeability, and CYP inhibition, using the protocols described in Section 3.1.

- This integrated step is crucial for prioritizing scaffolds that not only maintain potency but also exhibit desirable drug-like properties.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold Hopping and ADMET Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| ReCore (BiosolveIT) | Software | Identifies scaffold replacements that match the geometry of existing substituents [28]. |

| BROOD (OpenEye) | Software | Performs scaffold hopping via 3D shape and chemical feature comparison [28]. |

| Spark (Cresset) | Software | Uses field-based similarity to propose bioisosteric replacements and scaffold hops [28]. |

| ADMET Predictor (Simulations Plus) | Software/Platform | Predicts over 175 ADMET properties from molecular structure, useful for post-hop evaluation [33]. |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Database | Provides curated datasets for ADMET property prediction to train and validate models [32]. |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library | A Python library for building and training Graph Neural Networks on molecular graph data [30]. |

Case Studies and Data Analysis

The practical application of these protocols is best illustrated through real-world examples from the literature.

Case Study 1: Optimizing a BACE-1 Inhibitor for Solubility A team at Roche aimed to improve the solubility of a BACE-1 inhibitor candidate for Alzheimer's disease. The original lead contained a central phenyl ring, contributing to high lipophilicity (logD) [28]. Using the ReCore software, they performed a scaffold hop, replacing the phenyl ring with a trans-cyclopropylketone moiety. The resulting compound maintained excellent potency for BACE-1, as confirmed by co-crystallization, while achieving a significant reduction in logD and a concomitant improvement in solubility. This success underscores how a targeted core replacement, guided by computational prediction, can directly address a specific physicochemical liability without sacrificing activity.

Case Study 2: Discovering a Novel ROCK1 Kinase Inhibitor In a collaboration between Charles River and Chiesi Farmaceutici, a novel core-hopping workflow was applied to design an inhibitor of the kinase ROCK1. The workflow combined brute-force enumeration with 3D shape screening. Starting from a known inhibitor, the team discovered a novel chemotype featuring a seven-membered azepinone ring [28]. X-ray crystallography revealed that despite the completely different central scaffold, the novel compound and the original ligand shared nearly identical poses, with key hinge-binding and P-loop interacting groups overlapping perfectly. This topology-based hop successfully generated a novel, patentable chemotype with maintained efficacy.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Advanced Representation Models on ADMET Tasks

| Model/Approach | Molecular Representation | ADMET Task / Dataset | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auto-ADMET [34] | Grammar-based Genetic Programming (GGP) | 12 benchmark ADMET datasets | Superior performance on 8/12 datasets vs. baseline methods (XGBOOST, pkCSM) |

| MSformer-ADMET [32] | Multiscale, fragment-aware Transformer | 22 tasks from TDC (Classification & Regression) | Superior performance across a wide range of endpoints vs. SMILES-based and graph-based models |

| Graph-Based Models (GCN/GAT) [30] | Molecular Graph (Atom/Bond Features) | Prediction for major CYP isoforms (e.g., 3A4, 2D6) | High precision in modeling drug-enzyme interactions; improved with attention mechanisms |

Integrated Discussion

The interplay between molecular representation, scaffold hopping, and ADMET prediction forms a critical feedback loop in modern drug design. As demonstrated, graph-based representations and 3D pharmacophore models provide the necessary granularity to execute successful scaffold hops while anticipating ADMET liabilities. The emergence of more sophisticated representations, such as the fragment-aware, multiscale approach of MSformer-ADMET, promises even greater generalization across diverse chemical tasks [32]. Furthermore, the adoption of AutoML frameworks like Auto-ADMET can help automate the process of selecting the optimal model and representation for a given ADMET endpoint, personalizing the predictive pipeline to the specific chemical space of interest [34].

A significant challenge that remains is the quality and consistency of the underlying experimental data used for training. As noted in the field, a lack of correlation between results for the same assay conducted by different groups can severely limit model reliability [2]. Initiatives like OpenADMET, which focus on generating high-quality, consistent experimental data specifically for model development, are therefore paramount for future progress [2].

The logical relationships between data, representation, model training, and their impact on the practical applications of scaffold hopping and ADMET profiling can be summarized in a single diagram, illustrating the integrated pipeline from computational design to a successfully optimized compound.

Diagram 2: The critical pathway from data and representation to successful scaffold hopping.

Implementing Modern AI Representations: A Practical Guide for ADMET Endpoints

Molecular representation learning serves as the foundational step in modern computational chemistry and drug discovery, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological activities. The transition from traditional descriptor-based approaches to sophisticated AI-driven representations has significantly enhanced our ability to predict critical ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties. As the chemical space explored in drug discovery expands, selecting an appropriate molecular representation has become increasingly critical for developing accurate, generalizable, and interpretable predictive models. This application note provides a structured comparison of three predominant molecular representation paradigms—graph-based, language model-based, and high-dimensional feature approaches—to guide researchers in selecting optimal methodologies for their specific ADMET modeling challenges.

The evolution of molecular representation has progressed from manual descriptor calculation to automated feature learning, with each paradigm offering distinct advantages for specific applications in ADMET prediction.

Graph-Based Representations

Graph-based methods explicitly represent molecules as topological graphs where atoms correspond to nodes and bonds to edges. This natural alignment with molecular structure enables these approaches to effectively capture spatial relationships and functional group arrangements. Modern implementations utilize Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that employ neighborhood aggregation to learn complex structural patterns. Recent innovations like MolGraph-xLSTM address traditional GNN limitations in capturing long-range dependencies by incorporating extended Long Short-Term Memory architectures, demonstrating significant performance improvements across multiple ADMET benchmarks [35]. These models are particularly valuable for predicting properties governed by specific molecular substructures or metabolic pathways, such as CYP450 metabolism [30].

Language Model-Based Representations

Language model-based approaches treat molecular representations as textual sequences, primarily using SMILES strings or similar line notations. By adapting transformer architectures and tokenization strategies from natural language processing, these models learn contextual relationships between molecular subunits. The MLM-FG model introduces a novel pre-training strategy that randomly masks chemically significant functional groups, compelling the model to develop a deeper understanding of structural context [36]. Hybrid approaches like fragment-SMILES tokenization further enhance performance by incorporating both atomic and substructural information, demonstrating state-of-the-art results in multi-task ADMET prediction [37]. These methods excel at exploring vast chemical spaces and identifying structurally diverse compounds with similar properties.

High-Dimensional Feature Representations

High-dimensional feature representations encompass traditional molecular descriptors and fingerprints that encode chemical information as numerical vectors. These include calculated physicochemical properties, topological indices, and binary fingerprints indicating substructure presence. Methods like FP-BERT employ substructure masking pre-training strategies on extended-connectivity fingerprints to derive high-dimensional molecular representations [15]. While sometimes limited in capturing complex structural relationships, these representations offer computational efficiency and high interpretability, making them valuable for quantitative structure-activity relationship studies and models requiring explicit feature importance analysis [1].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Molecular Representation Paradigms

| Representation Type | Data Structure | Key Strengths | Common Algorithms | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph-Based | Topological graph (nodes/edges) | Captures structural hierarchies; Natural molecular mapping | GCN, GAT, MPNN, GIN | CYP metabolism prediction, Toxicity assessment |

| Language Model-Based | Sequential string (SMILES/SELFIES) | Explores novel chemical space; Transfer learning capabilities | Transformer, BERT, RoBERTa | Scaffold hopping, Multi-property prediction |

| High-Dimensional Features | Numerical vector (descriptors/fingerprints) | Computational efficiency; High interpretability | Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost | QSAR modeling, Virtual screening |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

To objectively evaluate representation performance, we compiled benchmark results across standardized ADMET datasets. The following tables summarize key metrics for classification and regression tasks from recent literature.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on ADMET Classification Tasks (AUROC)

| Representation Model | BBB Penetration | CYP2C9 Inhibition | AMES Mutagenicity | Hepatotoxicity | Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolGraph-xLSTM [35] | - | 0.866* | - | - | 0.684 |

| MLM-FG [36] | 0.970 | 0.920 | 0.890 | 0.910 | - |

| FP-BERT [15] | 0.940 | 0.890 | 0.860 | 0.870 | - |

| Hybrid Fragment-SMILES [37] | 0.960 | 0.910 | 0.880 | 0.900 | - |

| Ensemble Descriptors [1] | 0.930 | 0.880 | 0.850 | 0.860 | 0.670 |

*Average performance across multiple CYP isoforms

- : Data not reported in benchmark studies

Table 3: Performance Comparison on ADMET Regression Tasks (RMSE)

| Representation Model | Solubility (logS) | Plasma Protein Binding | Half-Life | Clearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolGraph-xLSTM [35] | 0.527 | 11.772 | - | - |

| MLM-FG [36] | 0.510 | - | 0.320 | 0.280 |

| FP-BERT [15] | 0.650 | - | 0.410 | 0.350 |

| Hybrid Fragment-SMILES [37] | 0.540 | - | 0.350 | 0.310 |

| Ensemble Descriptors [1] | 0.680 | 13.500 | 0.450 | 0.390 |

- : Data not reported in benchmark studies

Analysis of these benchmarks reveals several key trends. Graph-based approaches like MolGraph-xLSTM demonstrate strong performance in complex property prediction, particularly for metabolism-related endpoints, achieving an average AUROC improvement of 3.18% for classification tasks and RMSE reduction of 3.83% for regression tasks compared to baseline methods [35]. Language model-based representations excel in solubility prediction and scenarios requiring transfer learning, with MLM-FG outperforming existing SMILES- and graph-based models in 9 of 11 benchmark tasks [36]. High-dimensional feature representations provide competitive performance with significantly lower computational requirements, making them practical for resource-constrained environments [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Graph-Based Representation with GNN

Purpose: To create a graph-based molecular representation system for predicting CYP450 metabolism using a message-passing neural network framework.

Materials:

- RDKit cheminformatics toolkit

- PyTor Geometric or DGL library

- CYP450 inhibition dataset (e.g., from ChEMBL)

- Standard computing infrastructure (GPU recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Convert SMILES strings to molecular graphs using RDKit

- Initialize node features using atom descriptors (atom type, degree, hybridization, etc.)

- Initialize edge features using bond descriptors (bond type, conjugation, etc.)

- Split dataset using scaffold splitting to ensure generalization [30]

Model Architecture:

Training Configuration:

- Utilize Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Implement cosine annealing learning rate scheduler

- Apply gradient clipping with maximum norm 1.0

- Use binary cross-entropy loss for classification tasks

Interpretation Analysis:

- Extract attention weights to identify structural determinants

- Visualize important substructures using RDKit mapping

- Validate identified substructures against known metabolic pathways

Protocol: Implementing Language Model Representation with Transformer

Purpose: To develop a SMILES-based molecular representation system using transformer architecture for multi-task ADMET prediction.

Materials:

- Tokenization library (SMILES or hybrid tokenizer)

- Transformer architecture (BERT or RoBERTa base)

- Pre-training corpus (e.g., 10-100 million molecules from PubChem)

- ADMET benchmark datasets

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

Tokenization Strategy:

- For standard SMILES: Character-level tokenization

- For hybrid approaches: Combine high-frequency fragments with character-level tokens

- Implement strategic masking of functional groups during pre-training [36]

Pre-training Phase:

- Train model on large-scale unlabeled molecular dataset (10M-100M compounds)

- Use masked language modeling objective with 15% masking ratio

- Employ early stopping based on validation perplexity

Fine-tuning Phase:

- Add task-specific prediction heads for each ADMET endpoint

- Implement multi-task learning with balanced sampling [37]

- Use gradient accumulation for small batch sizes

Validation:

- Evaluate on hold-out test sets with scaffold split

- Perform ablation studies on tokenization strategies

- Compare against baseline models using statistical testing

Protocol: Implementing High-Dimensional Feature Representation

Purpose: To create a comprehensive molecular representation using engineered descriptors and fingerprints for efficient ADMET modeling.

Materials:

- RDKit or alvaDesc for descriptor calculation

- Scikit-learn or XGBoost for machine learning

- Feature selection algorithms

- ADMET datasets with clean experimental measurements [1]

Procedure:

- Feature Generation:

- Calculate 200+ RDKit molecular descriptors (constitutional, topological, etc.)

- Generate extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) with radius 2 and 1024 bits

- Compute additional physicochemical properties (logP, TPSA, etc.)

Feature Processing:

- Remove near-constant features (variance thresholding)

- Address missing values using imputation or removal

- Standardize features to zero mean and unit variance

Feature Selection:

- Apply recursive feature elimination with cross-validation

- Use mutual information scoring to identify relevant features

- Remove highly correlated features (Pearson correlation >0.95)

Model Training:

- Implement ensemble methods (Random Forest, XGBoost)

- Optimize hyperparameters using Bayesian optimization

- Apply nested cross-validation for robust performance estimation

Model Interpretation: