Beyond the Library: Modern Strategies for Exploring Chemical Space to Discover Novel Scaffolds in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary computational and AI-driven strategies for exploring the vast chemical space to identify novel molecular scaffolds.

Beyond the Library: Modern Strategies for Exploring Chemical Space to Discover Novel Scaffolds in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary computational and AI-driven strategies for exploring the vast chemical space to identify novel molecular scaffolds. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, advanced methodologies including generative AI and quantum computing, practical optimization techniques to enhance synthetic accessibility and sample-efficiency, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide serves as a roadmap for leveraging chemical space exploration to accelerate the discovery of innovative, druggable compounds for challenging therapeutic targets.

Mapping the Uncharted: Defining Chemical Space and Scaffold Diversity for Drug Discovery

The chemical space of potential drug-like small molecules is a realm of almost incomprehensible vastness, estimated to contain over 10⁶⁰ compounds [1]. To contextualize this magnitude, this number approximates the count of atoms in the entire Milky Way galaxy [1]. This infinite landscape, known as "chemical space," represents the set of all possible small molecules that could theoretically exist, yet only a minuscule fraction has been synthesized or tested [1]. For perspective, major public compound databases like PubChem or ChEMBL contain millions of molecules, which is negligible compared to the totality of this virtual universe [1]. This disparity creates both extraordinary opportunity and significant challenge for drug discovery researchers seeking novel scaffolds.

The fundamental dilemma in modern drug discovery is that while chemical space is effectively infinite, biologically active molecules tend to cluster in narrow regions of this space [1]. This clustering creates substantial risk for innovators; companies investing years in unlocking a target's biology may find their work swiftly followed by competitors who design structurally similar, safer, or higher-quality molecules and reach clinical trials in a fraction of the time [1]. Consequently, the strategic exploration and protection of chemical space has become as crucial as the discovery process itself, driving the development of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) and computational methods to navigate this cosmic expanse efficiently.

Theoretical Foundations: Defining and Mapping the Chemical Universe

Conceptual Frameworks and Key Definitions

Chemical space is formally defined as a multidimensional space where molecular properties—both structural and functional—define coordinates and relationships between compounds [2]. Within this overarching universe exist numerous chemical subspaces (ChemSpas) distinguished by shared structural or functional features [2]. Of particular importance is the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS), which comprises molecules with biological activity—both beneficial and detrimental—spanning drug discovery, agrochemistry, natural products, and toxic compounds [2].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Chemical Space Exploration

| Concept | Definition | Significance in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Space | The set of all possible small molecules that could exist, estimated at >10⁶⁰ drug-like compounds [1] | Represents the total universe of discoverable compounds |

| Scaffold | The core molecular structure, often comprising ring systems and linkers, while peripheral components may vary [1] | Determines fundamental binding properties and provides the structural foundation for drug candidates |

| Scaffold Hopping | Designing structurally distinct molecules that retain similar biological activity to the original compound [3] | Enables discovery of novel IP while maintaining efficacy; crucial for patent navigation |

| Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) | Subset of chemical space comprising molecules with biological activity [2] | Focuses exploration on regions with higher probability of therapeutic utility |

Molecular Representation: The Language of Chemical Space

To computationally navigate chemical space, molecules must be translated into computer-readable formats through molecular representation methods [3]. These representations bridge the gap between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties [3]. Traditional approaches include:

- String-based representations: Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) provides compact encoding of chemical structures as strings [3]

- Molecular fingerprints: Encode substructural information as binary strings or numerical values, such as extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) [3]

- Molecular descriptors: Quantify physical or chemical properties like molecular weight, hydrophobicity, or topological indices [3]

Modern AI-driven approaches employ deep learning techniques including graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformers to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large datasets [3]. These advanced representations better capture subtle structure-function relationships and enable more efficient exploration of chemical space [3].

Methodological Approaches: Navigating the Infinite

AI-Driven Exploration: The LEGION Framework

The LEGION (Latent Enumeration, Generation, Integration, Optimization, and Navigation) framework represents a paradigm shift in chemical space exploration [1]. This powerful AI-driven workflow addresses not only efficient searching but comprehensive coverage of chemical space to protect innovation from fast followers [1]. LEGION employs a multi-pronged strategy:

- Maximizing Scaffold Diversity: Unlike conventional approaches that over-optimize around few known scaffolds, LEGION tweaks the generative reward system to give all promising molecules equal credit while penalizing highly similar ones, pushing the system to explore new structural shapes [1].

- Handling Complex Chemistry: Generative models often struggle with complex scaffolds having multiple attachment points. LEGION simplifies tricky structures by systematically replacing attachment points with common drug side-chains, making them computationally manageable [1].

- Combinatorial Explosion: After initial generation, LEGION implements a mixing-and-matching step where side-chain fragments from one scaffold are added to attachment points of other scaffolds, exponentially multiplying the number of virtual compounds generated [1].

In proof-of-concept testing, a single round of combinatorial explosion from approximately 12,000 scaffolds yielded nearly 123 billion structures [1]. This massive-scale generation enables regions of chemical space that would otherwise remain unexplored to be disclosed at scale, preventing competitors from patenting these structures [1].

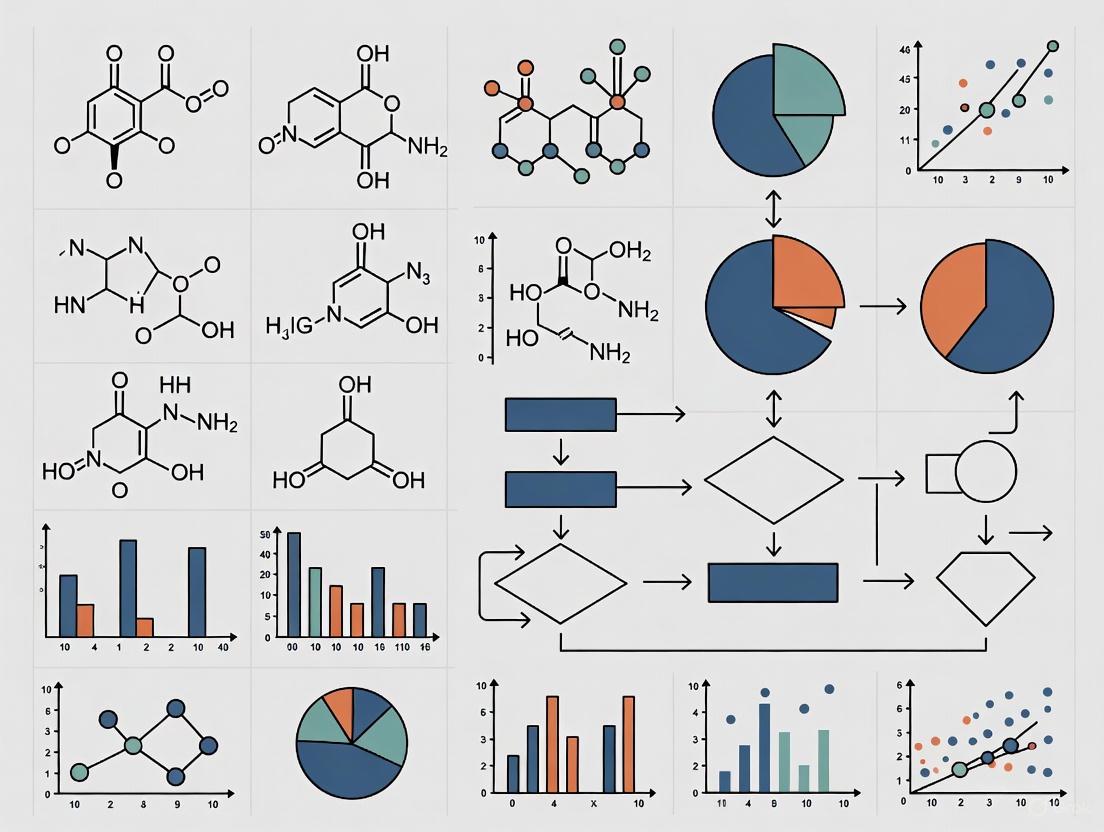

Figure 1: LEGION AI Workflow for Comprehensive Chemical Space Exploration. The LEGION framework employs a multi-stage process to maximize coverage of chemical space, from initial scaffold diversification through combinatorial explosion to generate billions of virtual compounds [1].

Chemical Space Visualization: Mapping the Unseeable

As chemical libraries grow to millions of compounds, effective visualization becomes essential for human interpretation [4]. The 'Big Data' era in medicinal chemistry presents analytical challenges because while computers can process millions of structures, final decisions remain in human hands, creating demand for visual navigation methods [5]. Modern approaches include:

- Dimensionality reduction techniques: Project high-dimensional chemical space into 2D or 3D for human comprehension [4]

- Chemical space maps: Enable interactive exploration and analysis of activity/property landscapes [4]

- Visual validation: Supports quality control of QSAR/QSPR models through intuitive representation [5]

These visualization methods extend beyond chemical compounds to include reactions and chemical libraries, providing medicinal chemists with intuitive tools for navigating structural and property relationships [4]. When combined with deep generative modeling, chemical space visualization enables interactive exploration of both known and novel regions [4].

Library Design Strategies: Focused vs. Make-on-Demand Approaches

Two predominant philosophies exist for constructing chemical libraries for screening:

- Scaffold-based libraries: Built on scaffold structuring and decoration guided by chemical expertise, such as the eIMS library (578 in-stock compounds) and its virtual companion vIMS library (821,069 compounds) derived from the same scaffolds [6]

- Make-on-demand spaces: Reaction- and building block-based approaches, exemplified by Enamine REAL Space and GalaXi, which offer massive collections of synthesis-ready virtual compounds [6] [7]

A comparative assessment revealed similarity between these approaches but limited strict overlap, with scaffold-based methods offering high potential for lead optimization [6]. The GalaXi chemical space, built in partnership with WuXi LabNetwork, offers one of the world's largest collections of synthesis-ready virtual compounds, featuring nearly 26 billion tangible molecules generated from 185 validated reactions and over 30,000 high-quality building blocks [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Chemical Space Generation Platforms

| Platform/Study | Scale of Generation | Key Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEGION AI Framework [1] | 123 billion structures from ~12,000 scaffolds | 34,000+ unique scaffolds identified for NLRP3 | Intellectual property protection & novel scaffold discovery |

| Anyo Lab MolGen [8] | Estimated explorable space: 10²³ to 10²⁹ molecules | 75.3% uniqueness in 1 billion sample | De novo lead-like hit identification with high diversity |

| GalaXi Chemical Space [7] | 25.8 billion synthesis-ready compounds | 185 validated reactions, 30,000+ building blocks | Make-on-demand tangible compounds for practical screening |

Experimental Protocols: Practical Implementation

Case Study: NLRP3 Inhibitor Development Using LEGION

The application of LEGION to NLRP3—a protein central to inflammation in numerous diseases—demonstrates the practical implementation of comprehensive chemical space exploration [1]. The experimental protocol comprised:

Step 1: Initial Scaffold Identification

- Researchers employed a combination of generative AI tools for designing new molecules and AI-based screening of existing molecular databases [1]

- Initial output identified over 34,000 unique scaffolds with potential NLRP3 binding affinity [1]

Step 2: Scaffold Simplification and Preparation

- Complex scaffolds with multiple attachment points were systematically simplified by replacing attachment points with common drug side-chains [1]

- This process limited free attachment points to computationally manageable numbers, resulting in nearly 94,000 final scaffolds [1]

Step 3: Generative Chemistry Expansion

- Prepared scaffolds were fed into the Chemistry42 generative chemistry engine [1]

- The system iteratively added and modified structural makeup and side-chains, yielding 6.5 million virtual compounds ready for virtual filtering and screening [1]

Step 4: Combinatorial Explosion

- A subset of scaffolds with two attachment points underwent combinatorial explosion [1]

- This process generated over 100 million structures as a feasible random sample of the total 123 billion structures generated [1]

Step 5: Expert Validation

- The most promising scaffolds underwent review by experienced medicinal chemists to confirm plausibility, novelty, and relevance for drug development [1]

- This human-in-the-loop validation ensured computational output represented credible chemical space expansion rather than computational noise [1]

The outcome was the open-sourcing of over 120 million AI-generated NLRP3 molecules, strategically making vast regions of NLRP3 chemical space unpatentable to fast followers while protecting Insilico's innovation [1].

Protocol for Chemical Space Estimation Using Ecological Models

Researchers at Anyo Lab developed a novel protocol for estimating the size of explorable chemical space using mathematical frameworks borrowed from ecology [8]:

Species Estimation Methodology:

- Generate a large sample of chemically valid molecules (1 billion in their study) [8]

- Apply ecological species-estimators: Chao1, ACE, and Good-Turing [8]

- Treat each unique molecule as a "species" for estimation purposes [8]

- Analyze how predictions update with increasing sample sizes to assess convergence [8]

Extrapolation Methodology:

- Model the unique fraction of molecules as a logarithmic function of the number generated [8]

- Extrapolate the function to estimate a lower bound prediction of unique molecules [8]

- Apply the same methodology to unique scaffolds using three scaffolding techniques:

- True Murcko Scaffolds (ring systems and linkers without double-bonded atoms)

- RDKit Murcko Scaffolds (includes double-bonded atoms)

- Generic Scaffolds (all atoms and bonds are carbon and single bonds) [8]

This approach yielded an estimated explorable chemical space of 10²⁶ molecules (with 95% confidence interval between 10²³ and 10²⁹) for their molecular generator [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool/Resource | Type/Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Chemistry Engines (e.g., Chemistry42) [1] | AI-driven molecular generation platforms | Creates novel molecular structures based on target parameters and training data |

| Scaffold Analysis Tools (Murcko, RDKit) [8] | Computational methods for scaffold extraction | Identifies and classifies core molecular structures from generated compounds |

| Molecular Representation Methods (SMILES, SELFIES, Graph Representations) [3] | Formats for encoding chemical structures as computer-readable data | Translates molecular structures into formats usable by machine learning algorithms |

| Make-on-Demand Chemical Spaces (GalaXi, Enamine REAL Space) [7] [6] | Synthesis-ready virtual compound libraries | Provides access to tangible compounds for virtual screening and experimental validation |

| Visualization Platforms (infiniSee, Chemical Space Maps) [4] [7] | Tools for dimensional reduction and visual navigation | Enables human interpretation of high-dimensional chemical data and relationships |

| Public Compound Databases (ChEMBL, PubChem) [2] | Curated repositories of known compounds and properties | Provides reference data for model training and validation of novel compounds |

Discussion: Implications and Future Directions

Strategic Intellectual Property Protection

The LEGION framework introduces a paradigm shift in intellectual property strategy for drug discovery [1]. By generating large families of molecules around each scaffold and disclosing them publicly, companies can block huge swaths of chemical space from competitors [1]. This creates stronger patent positions and greater protection for innovation, fundamentally reshaping how IP battles are fought in biotech [1]. The approach doesn't just accelerate discovery timelines but offers a new model for securing competitive advantage through preemptive disclosure of chemical space [1].

Limitations and Challenges

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in comprehensive chemical space exploration:

- Structural Data Dependency: Methods like LEGION rely heavily on structural data about target proteins, such as 3D crystal structures and known ligand interactions [1]. For targets without deep structural information, coverage would be less extensive.

- Underexplored Regions: Certain chemical subspaces remain underrepresented, including metal-containing molecules, macrocycles, protein-protein interaction modulators, and mid-sized peptides [2]. Most chemoinformatics tools are optimized for small organic compounds, creating blind spots for these important therapeutic classes [2].

- Universal Descriptors: The structural diversity across BioReCS presents challenges for developing consistent chemical space using molecular descriptors [2]. While new approaches like neural network embeddings show promise, systematic molecular fingerprints for biomaterials and inorganic molecules remain limited [2].

Emerging Frontiers

Future directions in chemical space exploration include developing more universal molecular descriptors that accommodate diverse compound classes [2], addressing pH-dependent chemical space to better reflect physiological conditions [2], and integrating human expertise through interactive visualization and validation tools [4] [5]. As AI methods continue evolving, the focus will shift from merely exploring chemical space to intelligently navigating its most promising regions while securing intellectual property to reward innovation investment.

Figure 2: The Evolution of Chemical Space Exploration Strategy. The field is transitioning from limited exploration of known regions toward comprehensive coverage of unexplored chemical territory through integrated approaches combining AI generation, tangible compound libraries, and human expertise [1] [4] [7].

In the realm of small-molecule drug discovery, a scaffold refers to the core structure of a molecule, describing the sub-structure shared by a group of compounds with the same framework [9]. These fundamental architectural blueprints typically consist of one or more core rings and can range from planar, aromatic compounds to complex three-dimensional structures [9]. The most widely applied definition in medicinal chemistry, originally introduced by Bemis and Murcko, generates scaffolds by removing all substituents (R-groups) while retaining aliphatic linkers between ring systems [10]. This conceptual framework allows researchers to classify and analyze compounds based on their underlying structural skeletons rather than their peripheral modifications.

Scaffolds serve as organizational principles in chemical space exploration, providing a systematic approach to navigating the vast universe of drug-like molecules estimated to exceed 10⁶⁰ compounds [8]. By focusing on these core structures, researchers can identify fundamental building blocks of bioactive molecules and establish structural relationships among diverse compounds. The systematic analysis of scaffolds enables medicinal chemists to track the evolution of molecular architectures across drug development stages, from initial leads to marketed drugs, and to make informed decisions about compound prioritization and optimization strategies [10]. This scaffold-centric perspective has become increasingly important in the age of computational drug discovery, where AI-generated scaffold libraries are revolutionizing the process of identifying novel therapeutic candidates [9].

Scaffolds in Bioactivity and Target Engagement

Activity Profiles and Target Relationships

Scaffolds play a decisive role in determining the biological activity and target selectivity of drug molecules. Each scaffold is associated with a characteristic activity profile—the combination of target annotations of all compounds sharing that core structure [10]. These profiles reveal fascinating relationships between structural blueprints and biological effects, ranging from closely overlapping to distinct target interactions. Systematic studies have demonstrated that drug scaffolds exhibit a variety of activity profile relationships, with some scaffolds showing remarkable specificity for single targets while others display promiscuous behavior across multiple target classes [10].

The concept of consensus activity profiles provides a qualitative and quantitative framework for assessing the activity similarity of structurally related drugs represented by the same scaffold [10]. This approach allows researchers to distinguish scaffolds representing drugs active against distinct targets from those with similar target profiles. By analyzing these consensus profiles, medicinal chemists can derive target hypotheses for individual drugs and make predictions about potential off-target effects or repurposing opportunities. This scaffold-activity relationship mapping is particularly valuable when exploring structural analogs for lead optimization, as it helps identify core structures with desired polypharmacology or improved selectivity profiles.

Scaffold Promiscuity and Selectivity

The degree to which a scaffold interacts with multiple biological targets—its promiscuity—is a critical parameter in drug design. Scaffold-based promiscuity is calculated as the total number of target annotations comprising the scaffold's activity profile [10]. Understanding the promiscuity tendencies of different scaffold classes enables more informed decisions in lead selection. Some scaffolds inherently tend toward narrow target engagement, making them suitable for diseases where specific inhibition is required, while others with broader target interactions may be advantageous for complex diseases requiring multi-target approaches.

Recent analyses have revealed systematic differences in activity profile relationships between scaffolds derived from approved drugs versus those from bioactive compounds in research databases [10]. Surprisingly, studies have identified 221 drug scaffolds that were not found in currently available bioactive compounds, suggesting that current drug space is chemically distinct from the broader universe of explored bioactive compounds [10]. This finding highlights the potential for discovering novel bioactive scaffolds by studying approved drugs and their structural relationships.

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold-Target Relationships

| Relationship Type | Structural Features | Biological Implications | Drug Design Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Specific | Highly constrained geometry with complementary binding motifs | High selectivity for single target class | Narrow-spectrum drugs with reduced side effects |

| Promiscuous | Flexible core with multifunctional recognition elements | Engagement with multiple target families | Polypharmacology approaches for complex diseases |

| Scaffold-Hopping | Structural variation maintaining pharmacophore | Similar activity with improved properties | Overcoming patent constraints or toxicity issues |

Structural Relationships and Classification

Types of Structural Relationships

The structural landscape of scaffolds can be systematically organized through defined relationship categories. Research has established four primary types of structural relationships between drug scaffolds and bioactive scaffolds [10]:

Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Relationship: Defined as a pair of compounds that differ only by a structural change at a single site, typically involving small replacements of R-groups [10]. The exchange of substructures that transforms one compound into another is termed a chemical transformation, and size restrictions are usually applied to limit structural differences to meaningful yet conservative changes.

Synthetic Relationship: Generated using retrosynthetic combinatorial analysis procedure (RECAP) rules that fragment bonds according to reaction information [10]. Compounds forming RECAP-MMPs are considered synthetically related, providing valuable insights for medicinal chemists planning synthetic routes for scaffold exploration.

Substructure Relationship: Occurs when a scaffold is entirely contained within another larger scaffold [10]. Such relationships reveal hierarchical organization in chemical space, with simpler cores embedded within more complex architectures. Analysis is typically limited to scaffolds differing by one or two rings to avoid detecting very distant relationships.

Cyclic Skeleton (CSK) Equivalence: Represents the highest level of structural abstraction, where scaffolds are transformed by converting all heteroatoms to carbon and setting all bond orders to one [10]. CSK-equivalent scaffolds are topologically identical and differ only by heteroatom substitutions or bond order variations.

Structural Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for analyzing structural relationships between molecular scaffolds:

Experimental Analysis of Scaffolds

Quantitative Scaffold Analysis Methodology

Advanced experimental methods enable detailed analysis of scaffolds in various contexts, including tissue engineering and biomaterial science. One established protocol for quantitative analysis of cells encapsulated in scaffolds involves specific staining and imaging techniques [11]. The method details include:

Sample Staining Protocol:

- A scaffold fragment of at least 0.64 cm² is placed in a 24-well fluorescence microscopy plate with opaque side walls

- In vivo staining of cell nuclei within the scaffold using Hoechst 33342 fluorochrome, highly specific for double-stranded DNA molecules

- Addition of 1 µl of Hoechst 33342 solution (10 µg/ml) to each well containing scaffold fragment and 2 ml culture medium

- Incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Removal of dye medium and washing twice with phosphate buffer (PBS)

- Addition of 0.3-1 ml phosphate buffer to prevent sample drying during analysis [11]

Data Visualization and Recording:

- Transfer of plate to fluorescence microscopy facility equipped with Z-stack function

- Imaging using fluorescence channel (excitation 377 nm, emission 477 nm)

- Capture of 5 or more fields of view using 4x or 10x objective

- Layer-by-layer shooting along Z-axis to depth of ≤530 µm with subsequent image stitching (Z-stack)

- Generation of stitched Z-stack images for each field of view [11]

Image Processing and Quantitative Analysis:

- Processing of stitched Z-stack images using specialized software (e.g., Gen 5 Image)

- Application of fluorescence intensity threshold filter (>7000) and object area filter (<30 µm)

- Counting of cell nuclei in each stitched Z-stack image

- Calculation of average cell count across multiple images

- Determination of cell density in scaffold volume using formula: [ K = \frac{N}{B \times C \times D \times 10^{-9}} ] where K = cells per mm³, N = average cell count, B/C/D = field dimensions in µm [11]

Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function in Scaffold Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 | Fluorochrome, excitation 377 nm/emission 477 nm | Highly specific staining of double-stranded DNA for cell nucleus visualization in scaffolds [11] |

| Fluorescence Microscopy Plate | 24-well, opaque side walls (e.g., Black Visiplate TC) | Optimal vessel for fluorescence-based imaging while minimizing background signal interference [11] |

| Cytation 5 Imager | Wide-field fluorescence microscope with Z-stack function | Enables layer-by-layer imaging through scaffold depth with subsequent image stitching capability [11] |

| Gen5 Image Software | Image analysis platform | Processes stitched Z-stack images, applies filters, and enables quantitative cell counting [11] |

| Phosphate Buffer (PBS) | Standard formulation, pH 7.4 | Washing and hydration medium for maintaining scaffold integrity during analysis [11] |

Computational Approaches to Scaffold Exploration

Scaffold Hopping and Computational Design

Scaffold hopping represents a critical strategy in medicinal chemistry for generating novel, patentable drug candidates by identifying compounds with different core structures but similar biological activities [12]. This approach helps overcome challenges such as intellectual property constraints, poor physicochemical properties, metabolic instability, and toxicity issues [12]. Several computational frameworks have been developed to facilitate scaffold hopping:

ChemBounce: An open-source computational framework that identifies core scaffolds and replaces them using a curated library of over 3 million fragments derived from the ChEMBL database [12]. The tool evaluates generated compounds based on Tanimoto and electron shape similarities to ensure retention of pharmacophores and potential biological activity.

FTrees Algorithm: A pharmacophore-based similarity search method that introduces "fuzziness" while maintaining functionality, allowing escape from the similarity gravitational field of a molecule while generating results with similar functionalities [13]. This algorithm serves as the engine for the Scaffold Hopper Mode in infiniSee software.

ReCore Algorithm: Focuses on structure-based core replacement by selecting a portion of the molecule to be replaced using vectors while keeping decorations (side chains) intact [13]. The search identifies replacements that fit specified 3D criteria and can be refined with additional pharmacophore constraints.

These computational approaches enable systematic exploration of unexplored chemical space, making them valuable tools for hit expansion and lead optimization in modern drug discovery [12]. Successful applications of scaffold hopping have led to marketed drugs including Vadadustat, Bosutinib, Sorafenib, and Nirmatrelvir [12].

AI-Generated Scaffold Libraries

Artificial intelligence has transformed scaffold exploration through the generation of novel molecular frameworks. AI-generated scaffold libraries primarily utilize deep-learning generative modeling approaches such as g-DeepMGM, which uses recurrent neural networks (RNN) and long short-term memory units (LSTM) to learn SMILES strings and molecular characteristics [9]. These models generate target-focused molecules by learning probability distributions from training sets.

The explorable chemical space of AI-based molecular generators is astonishingly large. Research indicates that tools like Anyo Lab's MolGen can access a chemical space estimated at 10²⁶ compounds, with exceptional diversity demonstrated by high Tanimoto dissimilarity scores (0.889 for full molecules) [8]. Analysis of scaffold diversity reveals predicted minimum numbers of unique scaffolds at approximately 1.1 × 10¹⁰ for RDKit Murcko scaffolds, 6.5 × 10⁹ for True Murcko scaffolds, and 1.2 × 10⁸ for Generic scaffolds [8].

Table 3: AI Tools for Scaffold Generation and Their Applications

| AI Tool/Platform | Core Technology | Scaffold Generation Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| g-DeepMGM | RNN/LSTM networks learning SMILES strings | Generation of target-focused molecular scaffolds | Learns molecular syntax and structure-property relationships [9] |

| RFdiffusion | Diffusion models for 3D structure generation | Protein-structure-guided scaffold generation | Iterative refinement of 3D molecular geometries [9] |

| Stable Diffusion WebUI | Text-to-scaffold generation with visualization | Rapid prototyping of novel scaffolds | High-resolution chemical visualization for academic research [9] |

| ModelScope | Pre-trained models for scaffold optimization | Collaborative scaffold discovery across institutions | Open-source community with diverse model library [9] |

Scaffold-Based Drug Design Applications

Overcoming Development Challenges

Scaffold-based drug design provides strategic solutions to common challenges in drug development. An unwanted scaffold—a structural component that forms the pharmacophore but causes toxicity—can be replaced through scaffold hopping to rescue promising compounds late in the R&D process [13]. Similarly, patent-protected scaffolds of successful drugs can be modified to create novel, patentable chemotypes that target the same blockbuster mechanism of action [13].

The most efficient method for scaffold hopping involves introducing a wild card parameter that retains the core essence of the compound while delivering structurally distinct motifs [13]. This strategic fuzziness allows researchers to escape the similarity gravitational field of a molecule while maintaining similar functionalities. By combining this approach with orthogonal methods such as 3D alignment and molecular fingerprints, researchers can identify compounds that maintain relatedness across multiple analytical dimensions [13].

3D Methods in Scaffold Optimization

Three-dimensional approaches provide essential refinement for scaffold-based drug design, particularly when attempting to overcome scaffold limitations. While 2D methods can yield success, structural modifications crucial for scaffold optimization often require 3D consideration [13]. Key 3D methods include:

- SeeSAR's Similarity Scanner Mode: Performs ligand-based virtual screening with 3D alignment capabilities [13]

- FlexS: Enables 3D compound alignment and superposition-focused virtual screening [13]

- InfiniSee xREAL: Exclusive platform for screening ultra-large compound catalogs featuring trillions of compounds using pharmacophore-based similarity [13]

These 3D approaches allow incorporation of key project insights through constraints applied to template molecules, ensuring resulting compounds maintain critical functionalities in appropriate 3D arrangements [13]. This is particularly important when multiple key features define the pharmacophore and must be preserved in proposed scaffolds.

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Current Limitations in Scaffold Research

Despite significant advances, several challenges persist in scaffold-based drug discovery:

Data Quality and Availability: AI model effectiveness highly depends on high-quality, diverse data, yet pharmaceutical data is often incomplete, inconsistent, or biased [9]. The industry has only obtained experimental data from a minute fraction of possible synthetic compounds (less than one billion out of 10³⁰), with uneven quality and reproducibility [9].

Limited Biological Understanding: Current AI applications focus predominantly on molecular design and ligand screening but lack comprehensive understanding of complex biological environments where drugs operate [9]. This limitation restricts accurate prediction of drug safety and efficacy.

Synthetic Feasibility: AI-generated scaffolds often prioritize binding affinity over synthetic accessibility, resulting in molecules that are difficult to synthesize or validate [9]. This disconnect between in silico design and practical synthesis remains a significant hurdle.

Lack of Negative-Result Data: The underpublication of "failed" data compared to positive findings creates gaps in training machine learning models, affecting their predictive performance [9].

Integration Workflow for Scaffold-Based Discovery

The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for scaffold-based drug discovery, combining computational and experimental approaches:

Future Directions

The future of scaffold-based drug discovery lies in addressing current limitations through enhanced data quality, interdisciplinary collaboration, and improved algorithmic design [9]. The integration of AI-generated scaffold libraries with experimental validation creates a virtuous cycle of innovation, where computational predictions inform laboratory synthesis and biological testing results refine AI models. As these technologies mature, scaffold-based approaches will continue to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic candidates, particularly for challenging targets and underserved disease areas.

The expanding exploration of chemical space through advanced computational methods reveals the incredible structural diversity available for drug discovery. With estimates of up to 10¹⁴ unique molecules accessible through current generators [8], the potential for discovering novel bioactive scaffolds remains largely untapped. This vast landscape, properly navigated through sophisticated scaffold-based strategies, holds the key to addressing unmet medical needs through innovative therapeutic design.

The exploration of chemical space is a fundamental challenge in modern drug discovery. With the estimated number of drug-like molecules exceeding 10^60, the development of strategic approaches to navigate this vast expanse is crucial for identifying novel therapeutic compounds [14]. Two dominant paradigms have emerged for constructing and screening chemical libraries: the traditional scaffold-based library design and the increasingly popular make-on-demand chemical space approach. Scaffold-based libraries employ a product-oriented design, starting from core structures known to be compatible with target binding sites and decorating them with diverse substituents [6] [15]. In contrast, make-on-demand spaces utilize a reaction-oriented approach, systematically combining available building blocks using robust chemical reactions to create ultra-large enumerable compound collections [6] [16]. This technical analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of these two methodologies, examining their underlying principles, chemical content, implementation workflows, and performance characteristics to guide researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for novel scaffold research.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Scaffold-Based Libraries

Scaffold-based library design is a knowledge-driven approach that begins with the identification of molecular frameworks or scaffolds demonstrated to have intrinsic binding compatibility with target proteins or protein families. These scaffolds are typically derived from known active compounds, natural products, or through virtual screening of core structures against target binding sites [15]. Once relevant scaffolds are identified, libraries are created by systematically decorating these cores with diverse R-groups selected from customized collections of substituents [6] [17]. This approach captures target specificity through the strategic selection of scaffolds that complement the topological and physicochemical features of the binding site.

The scaffold-based methodology enables the creation of both physical libraries (compounds in-stock and plated for high-throughput screening) and much larger virtual libraries (enumerated compounds accessible through synthesis) [17]. For example, research groups have successfully created essential in-stock libraries (eIMS) containing 578 compounds alongside companion virtual libraries (vIMS) of 821,069 compounds derived from the same scaffold set [6] [17]. This hierarchical library structure allows for initial screening of available compounds followed by expansion into related chemical space for lead optimization.

Make-on-Demand Chemical Spaces

Make-on-demand chemical spaces represent a paradigm shift toward reaction-based library design focused on synthetic accessibility and maximal coverage of chemical space. These spaces comprise virtual compounds that can be rapidly synthesized upon selection from robust chemical reactions and readily available building blocks [14] [16]. The Enamine REAL Space and eXplore are prominent examples, containing billions to trillions of virtual compounds generated from one- or two-step reactions using tiered building blocks with guaranteed availability [14] [16].

The fundamental architecture of make-on-demand spaces is built upon carefully curated reaction sets (47 robust chemical reactions in the case of eXplore) and building block collections filtered by synthetic accessibility and delivery time [16]. This design ensures that virtually any compound identified within the space can be synthesized and delivered within a practical timeframe, typically 2-4 weeks [16]. The unprecedented scale of these libraries (recently reaching trillions of compounds) provides unprecedented opportunities for identifying novel chemotypes but introduces significant computational challenges for virtual screening [14] [18].

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Content

Library Characteristics and Composition

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Scaffold-Based vs. Make-on-Demand Libraries

| Parameter | Scaffold-Based Libraries | Make-on-Demand Spaces |

|---|---|---|

| Design Approach | Product-oriented, knowledge-based | Reaction-oriented, accessibility-based |

| Library Size | Hundreds to hundreds of thousands | Billions to trillions |

| Coverage of FDA-Approved Drugs | High within focused areas | ~8% exact matches, ~44% close analogs |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Generally high, with low to moderate synthetic difficulty | Guaranteed via tiered building blocks and robust reactions |

| Chemical Diversity | Focused around privileged scaffolds | Extremely broad across all available chemistries |

| Primary Application | Target-focused screening, lead optimization | Ultra-large virtual screening, novel hit identification |

Overlap and Complementarity

Comparative assessments reveal limited strict overlap between scaffold-based libraries and make-on-demand chemical spaces, indicating significant complementarity between the two approaches [6]. Interestingly, a substantial portion of the R-groups used in scaffold-based library decoration are not identified as such in make-on-demand libraries, suggesting different chemical preferences and design principles [6] [17].

Analysis using multiple similarity search methods (FTrees, SpaceLight, SpaceMACS) against FDA-approved drugs demonstrates that make-on-demand spaces contain exact matches for approximately 8% of drugs and close analogs (similarity >0.8) for an additional 44% [16]. The remaining drugs lack close analogs primarily due to complex synthesis requirements not covered by standard one- to two-step reactions or the absence of specific building blocks needed for their construction [16].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Scaffold-Based Library Design Workflow

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Library Design

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite | Molecular docking, scaffold design | Structure-based scaffold identification [15] [19] |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation | Machine learning-guided screening [14] |

| Enamine Building Blocks | Chemical Reagents | R-group sources for library decoration | Library synthesis and expansion [6] |

| KNIME | Data Analytics Platform | Scaffold library classification, sub-library extraction | Bemis-Murcko structure analysis [19] |

| CatBoost | Machine Learning Algorithm | Classification of top-scoring compounds | Accelerated virtual screening [14] |

The design and implementation of scaffold-based libraries follows a systematic workflow:

Scaffold Identification and Validation: Molecular scaffolds are identified through structure-based virtual screening of core structures against target binding sites using docking programs such as DOCK 4.0 or MOE [15] [19]. Additionally, scaffolds are derived from known active compounds by deleting substituents from core structures while preserving binding pharmacophores [15].

R-Group Selection and Library Enumeration: Customized collections of R-groups are curated based on chemical diversity, synthetic feasibility, and drug-like properties. These substituents are systematically combined with validated scaffolds to generate virtual libraries [6] [17]. For example, the vIMS library containing 821,069 compounds was derived from 578 essential scaffolds [17].

Synthetic Accessibility Assessment: Proposed compounds are evaluated for synthetic feasibility using calculated metrics to ensure practical accessibility. Analyses indicate overall low to moderate synthetic difficulty for scaffold-based libraries [6].

Experimental Validation: Prioritized compounds are synthesized and subjected to biological testing. Active compounds serve as starting points for further optimization through iterative library design [19].

Diagram 1: Scaffold-Based Library Design Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from scaffold identification through lead optimization.

Make-on-Demand Screening Approaches

The enormous scale of make-on-demand chemical spaces necessitates specialized computational screening strategies:

Machine Learning-Guided Docking Screens: This approach combines machine learning classification with molecular docking to enable screening of billion-compound libraries. A classifier (e.g., CatBoost) is trained to identify top-scoring compounds based on docking of a subset (1 million compounds), then used to select compounds for full docking assessment from the larger library [14]. This protocol reduces computational cost by more than 1,000-fold while maintaining high sensitivity (0.87-0.88) [14].

Bottom-Up Fragment-Based Approach: This innovative strategy systematically explores the chemical space from fragment-sized compounds (up to 14 heavy atoms), which represents a relatively small but complete region of chemical space [18]. Fragment hits are analyzed to define essential cores for target binding, which are then used to query upper layers of chemical space through focused library enumeration [18].

Synthon-Based Screening: Methods like V-SYNTHES use synthon-based ligand screening to avoid costly direct screening of fully enumerated libraries [19]. This approach screens a library of scaffolds first, then expands favored scaffolds with different substituents for a second-round screening, significantly reducing computational requirements [19].

Diagram 2: Make-on-Demand Screening Workflows. Two complementary approaches for navigating ultra-large chemical spaces: machine learning-accelerated docking (left) and bottom-up fragment-based screening (right).

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Scaffold-Based Discovery of Nav1.7 Inhibitor

A recent application of scaffold-based screening led to the discovery of a novel Nav1.7 inhibitor for treating neuropathic pain. Researchers constructed an Oxindole-Based Readily Accessible Library (OREAL) characterized by unique chemical space, ideal drug-like properties, and structural diversity [19]. The library was generated using carbenoid-involved reactions (CIRs) known for high efficiency and minimal waste production [19].

The screening protocol involved:

- Scaffold Library Creation: Over 20 million virtual molecules were generated with 1,278 scaffolds using 39 reactions, then classified by Bemis-Murcko structure [19].

- First-Round Scaffold Screening: The scaffold library was docked to Nav1.7, identifying 18 scaffolds with favorable binding energy [19].

- Second-Round Expanded Screening: A sub-library was extracted based on the 18 selected scaffolds and subjected to a second docking round, yielding 42 virtual hits [19].

- Experimental Validation: Two compounds demonstrated Nav1.7 inhibitory activity, with compound C4 showing potent inhibition and effectively reversing paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain in rodent models [19].

This case study demonstrates how scaffold-based screening of a focused library can efficiently identify novel bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential.

Machine Learning-Guided Screen of Multi-Billion Compound Library

The application of machine learning-guided docking to make-on-demand spaces was demonstrated through a virtual screen of 3.5 billion compounds against G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [14]. The protocol employed a conformal prediction framework with CatBoost classifiers trained on Morgan2 fingerprints to identify virtual active compounds [14].

Key results included:

- Computational Efficiency: The approach reduced the number of compounds requiring explicit docking by more than 1,000-fold [14].

- Experimental Confirmation: Testing of predictions identified ligands for GPCR targets, including compounds with multi-target activity tailored for therapeutic effect [14].

- Robust Performance: The method achieved high sensitivity (0.87-0.88) while guaranteeing that error rates did not exceed the selected significance level (8-12%) [14].

This implementation demonstrates that machine learning-guided screening can practically access the vast chemical diversity of make-on-demand spaces while maintaining manageable computational requirements.

Integration and Future Perspectives

The comparative analysis reveals that scaffold-based libraries and make-on-demand chemical spaces offer complementary rather than competing approaches to chemical space exploration. Scaffold-based libraries provide target-focused efficiency through knowledge-guided design, while make-on-demand spaces offer unprecedented chemical diversity with guaranteed synthetic accessibility [6] [16].

Emerging integrated strategies leverage the strengths of both approaches:

- Bottom-Up Exploration: This methodology begins with exhaustive fragment screening (exploring the "bottom" of chemical space), then grows promising fragments into drug-sized compounds through scaffold expansion in make-on-demand spaces [18].

- Machine Learning-Augmented Design: AI/ML approaches are being developed to identify novel scaffolds within make-on-demand spaces that capture the essential binding features of known active compounds [14].

- Reaction-Based Scaffold Design: New scaffold sets are being developed based on robust chemical reactions used in make-on-demand spaces, ensuring both synthetic accessibility and target relevance [19].

The ongoing growth of make-on-demand libraries toward trillions of compounds will further intensify the need for sophisticated navigation strategies [14] [18]. Future advancements will likely focus on AI-driven methods that can seamlessly integrate structure-based design with reaction-based enumeration to efficiently explore the most relevant regions of chemical space for drug discovery.

In the field of drug discovery, the systematic analysis of molecular scaffolds—the core structural frameworks of molecules—is fundamental to exploring chemical space and prioritizing compounds for synthesis and screening. Scaffold diversity analysis provides medicinal chemists with critical insights into the structural composition of compound libraries, enabling the identification of novel chemotypes and helping to avoid over-representation of similar structures [20]. This exploration is crucial for understanding Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and for the strategic design of libraries that maximize the potential for discovering compounds with new biological activities [21]. The process of "scaffold hopping," or identifying new core structures that retain biological activity, relies heavily on robust quantitative methods for assessing scaffold distributions and uniqueness, allowing researchers to expand intellectual property opportunities and improve drug properties [3].

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions of Molecular Scaffolds

Hierarchical Scaffold Representations

A critical advancement in scaffold analysis has been the development of hierarchical representations, which allow researchers to visualize and classify compounds at different levels of structural abstraction. Unlike single-level definitions, hierarchies provide a multi-resolution view of chemical space.

- Bemis-Murcko Scaffolds: This foundational approach defines a molecular framework as the union of all ring systems and linker atoms connecting them, while removing all side chain atoms [22] [21].

- Schuffenhauer Scaffolds (Scaffold Tree): This method creates a tree hierarchy through the iterative removal of rings based on a priority list, resulting in a linear progression of scaffolds from complex to simple for each molecule [22].

- Oprea Scaffolds (Scaffold Topologies): These represent the most abstracted form—connected graphs with the minimal number of nodes required to describe the ring structure, obtained by iteratively replacing vertices of degree two with a single edge [22].

- Molecular Anatomy: This recent approach introduces a multi-dimensional network of nine different molecular representations at varying abstraction levels, combined with fragmentation rules to create a flexible framework for identifying relevant chemical moieties [21].

Table 1: Common Scaffold Definitions and Their Characteristics

| Scaffold Type | Level of Abstraction | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bemis-Murcko | Low | Includes all rings and connecting linkers | Initial library diversity assessment |

| Graph Framework | Medium | Atom connectivity only (disregards atom type and bond order) | Similarity searching |

| Scaffold Topology (Oprea) | High | Minimal nodes describing ring structure | Identification of core ring system patterns |

| Cyclic Skeleton | Very High | No bond or atom type information | Exploration of fundamental scaffold architectures |

Quantitative Metrics for Scaffold Diversity Analysis

Core Diversity Metrics

Quantifying scaffold diversity requires specific metrics that can evaluate the structural distribution of compounds within a library. These measurements allow for direct comparison between libraries of different sizes and origins.

The scaffold diversity of a compound library can be measured independently of its size through clustering approaches based on maximum common substructures [20]. This process involves identifying druglike compounds, clustering them by scaffolds, and then applying diversity metrics. Analysis of commercial screening collections has revealed that libraries generally fall into four categories: large- and medium-sized combinatorial libraries ( exhibiting low scaffold diversity), diverse libraries (medium diversity and size), and highly diverse libraries (high diversity but small size) [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Scaffold Diversity Analysis

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Frequency | Number of compounds sharing a common scaffold | Identifies over- and under-represented scaffolds | Large combinatorial libraries show high frequency for few scaffolds [20] |

| Scaffold Diversity Index | Normalized measurement independent of library size | Allows comparison between libraries of different sizes | Highly diverse libraries have a high diversity index despite small size [20] |

| Scaffold Coverage | Proportion of library represented by top N scaffolds | Measures redundancy | Analysis of 2.4M commercial compounds revealed distinct library categories [20] |

| Hierarchical Branching Factor | Number of child scaffolds per parent in a hierarchy | Indicates structural diversity at different abstraction levels | PubChem analysis enabled creation of 8-level hierarchy with molecules as leaves [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Diversity Assessment

Protocol 1: Basic Scaffold Diversity Analysis

This foundational workflow is adapted from the method used to analyze 2.4 million compounds from 12 commercial sources [20]:

Data Preparation and Filtering

- Start with molecular structures in standardized format (e.g., SMILES, SDF)

- Apply druglikeness filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five, molecular weight thresholds)

- Remove duplicates and invalid structures

Scaffold Extraction

- Generate Bemis-Murcko scaffolds for all compounds using standardized algorithms

- Optional: Apply additional abstraction levels (e.g., graph frameworks, topologies)

Scaffold Clustering

- Cluster compounds by maximum common substructures (scaffolds)

- Calculate scaffold frequencies and distributions

Diversity Quantification

- Compute diversity metrics independent of library size

- Compare diversity profiles across different libraries

- Identify scaffold families for targeted library acquisition

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Scaffold Analysis with Scaffvis

This protocol utilizes the Scaffvis tool for hierarchical visualization against the background of empirical chemical space, as demonstrated in the analysis of the PubChem Compound database [22]:

Hierarchy Definition

- Establish an 8-level scaffold hierarchy with a virtual root (level 0) and molecules as leaves (level 9)

- Ensure each molecule maps to exactly eight scaffolds, one for each level

Background Chemical Space Mapping

- Use PubChem Compound or another comprehensive database as reference chemical space

- Precompute the scaffold hierarchy for the background set

Target Dataset Analysis

- Map user compounds onto the background hierarchy

- Visualize using a zoomable tree map where square size encodes scaffold frequency in the background

- Use color coding to indicate frequency in the user dataset

Interpretation

- Identify scaffolds that are rare in the background but present in user data

- Recognize common scaffolds to avoid redundancy

- Use interactive features to navigate between hierarchy levels

Advanced Analysis Techniques and Visualization Approaches

Multi-Dimensional Hierarchical Analysis with Molecular Anatomy

The "Molecular Anatomy" approach addresses limitations of single-representation methods by employing multiple scaffold definitions simultaneously [21]. This method uses nine different molecular representations at varying abstraction levels, from detailed Bemis-Murcko scaffolds to highly abstracted cyclic skeletons. The workflow for implementing Molecular Anatomy includes:

Multi-Level Scaffold Generation

- Process each compound through all nine representation levels

- Generate correlated molecular frameworks interconnected in a multi-dimensional network

Network-Based Visualization

- Create a network graph connecting compounds through shared scaffolds at different levels

- Enable navigation through scaffold space for SAR analysis

- Identify activity cliffs where small structural changes cause significant potency differences

Application to HTS Data

- Stratify compounds by activity levels (e.g., percent inhibition)

- Identify scaffolds enriched in active compounds across multiple representation levels

- Cluster structurally diverse compounds that share abstract frameworks

This approach proved particularly valuable when analyzing 26,092 commercial compounds screened against HDAC7, where it successfully identified active chemotypes that would have been separated using traditional single-scaffold methods [21].

Chemical Space Network Analysis for Activity Landscapes

Modern scaffold analysis extends beyond simple diversity metrics to include activity landscapes, which correlate structural similarity with biological activity. The protocol for this analysis involves:

Similarity Calculation

- Generate molecular fingerprints (ECFP4, MACCS)

- Compute pairwise similarity matrices

Network Construction

- Represent compounds as nodes and similarities as edges

- Apply thresholding to retain significant connections only

- Use tools like RDKit and NetworkX for implementation [23]

Activity Landscape Visualization

- Incorporate pairwise activity differences

- Identify activity cliffs (pairs with high structural similarity but large potency differences)

- Map consensus patterns to assess global chemical space diversity

This approach was successfully applied to characterize 576 Spleen Tyrosine Kinase (SYK) inhibitors, revealing heterogeneous SAR patterns and specific activity cliff generators like CHEMBL3415598 [23].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Scaffold Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffvis | Visualization Tool | Interactive, zoomable tree map for hierarchical scaffold visualization | Web-based client-server application [22] |

| Molecular Anatomy | Analysis Platform | Multi-dimensional hierarchical scaffold analysis with network visualization | Web interface at https://ma.exscalate.eu [21] |

| ECFP4/MACCS Fingerprints | Molecular Representation | Structural characterization for similarity calculation and network analysis | RDKit, OpenBabel [23] |

| Scaffold Tree | Algorithm | Rule-based ring disassembly to create scaffold hierarchies | Implementation in various cheminformatics toolkits [22] |

| RDKit & NetworkX | Programming Libraries | Chemical informatics and network analysis for activity landscape modeling | Open-source Python libraries [23] |

Visualizing Analysis Workflows

Hierarchical Scaffold Analysis Workflow

Hierarchical Scaffold Analysis Workflow

Molecular Anatomy Multi-Dimensional Analysis

Molecular Anatomy Multi-Dimensional Analysis

The quantitative analysis of scaffold distributions and uniqueness provides an essential foundation for effective chemical space exploration in drug discovery. By employing hierarchical representations, robust diversity metrics, and advanced visualization tools, researchers can navigate complex structure-activity relationships and prioritize novel chemotypes with greater confidence. The integration of multi-dimensional analysis frameworks like Molecular Anatomy with activity landscape modeling represents the cutting edge of this field, enabling more efficient identification of promising scaffolds while maximizing the diversity of compound collections. As artificial intelligence approaches continue to evolve, particularly graph neural networks and language models for molecular representation [3], the capacity for scaffold hopping and novel chemical entity discovery will further accelerate, enhancing our ability to explore the vastness of chemical space systematically.

The escalating use of pesticides in agriculture and urban areas has led to significant contamination of aquatic ecosystems, posing substantial risks to non-target species [24]. Among these, fish such as the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are highly vulnerable due to their permeable gills and ecological importance, making them a key model in ecotoxicological studies [24] [25]. The vast and structurally diverse chemical space of pesticides, however, remains largely unmapped, presenting a major hurdle for environmental risk assessment and the design of safer compounds.

Framed within a broader thesis on chemical space exploration for novel scaffolds, this case study details the application of the Structure-Similarity Activity Trailing (SimilACTrail) map, a novel cheminformatics approach, to systematically investigate the structural diversity of pesticides and their acute toxicity to rainbow trout [24]. This integrated workflow moves beyond traditional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models by combining chemical space analysis with machine learning (ML) and quantitative Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (q-RASAR) strategies, offering a predictive and interpretable framework for pesticide prioritization [24] [26].

Methodology: The SimilACTrail Workflow and Predictive Modeling

This section outlines the core experimental protocols and computational methodologies employed in the study.

Dataset Curation and Chemical Space Mapping

The investigation began with a curated dataset of 311 pesticides with known acute toxicity (96-hour LC50) to rainbow trout, sourced from the literature [24]. During model optimization, 12 pesticides exhibiting high residuals were excluded based on statistical thresholds, resulting in a refined modeling set of 299 compounds [24].

The core of the chemical space exploration was the SimilACTrail mapping approach, executed using an in-house Python code repository [24]. This method is essential for visualizing the relationship between structural similarity and biological activity. The process likely involves:

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating a set of molecular descriptors for each pesticide to numerically represent their chemical structures.

- Similarity Matrix Construction: Calculating the pairwise structural similarity between all compounds in the dataset, potentially using indices like the Tanimoto index, which is an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations [24].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Projecting the high-dimensional similarity data into a 2D map to visualize clusters and trails of compounds with similar structures and activities.

Development of Predictive Models

Following the chemical space analysis, robust predictive models were built.

- Machine Learning (ML) Classifier: A supervised ML classifier was developed using optimized hyperparameters to achieve robust predictive performance for toxicity classification [24] [26].

- QSAR and q-RASAR Modeling: The study constructed traditional QSAR models and advanced q-RASAR models. The q-RASAR approach integrates conventional molecular descriptors with similarity and error-based metrics from the read-across protocol, enhancing predictive reliability and mechanistic interpretability [24]. Model validation adhered to strict OECD guidelines, ensuring statistical reliability and mechanistic interpretability [24].

External Validation and Data Gap Filling

The best-performing model was used to predict the toxicity of over 2,000 pesticides from external sources like the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB) and PubChem, achieving over 92% reliability for compounds within the model's Applicability Domain (AD) [24]. The AD was assessed using Williams and Insubria plots to identify where predictions were reliable [24].

Results and Discussion: Key Findings and Mechanistic Insights

The application of the outlined methodology yielded significant quantitative and qualitative results.

Chemical Space and Scaffold Diversity

The SimilACTrail map revealed a highly unique and diverse pesticide chemical space. The analysis showed several clusters with exceptionally high singleton ratios, ranging from 80.0% to 90.3% [24]. This indicates that a vast majority of pesticides in these clusters are structurally distinct from their nearest neighbors, underscoring the broad scaffold diversity and the challenge of predicting toxicity for structurally novel compounds.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings from the Study

| Aspect | Key Finding | Quantitative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Initial pesticides | 311 compounds [24] |

| Refined modeling set | 299 compounds [24] | |

| Chemical Space | Singleton ratio in clusters | 80.0% - 90.3% [24] |

| Model Prediction | Reliability for external pesticides within AD | >92% [24] |

| External Validation | Pesticides with filled toxicity data gaps | >2000 compounds [24] |

Model Performance and Critical Structural Features

The integrated modeling strategy successfully generated high-performance predictive tools. The q-RASAR models, in particular, demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional QSAR models, offering higher predictive efficacy and lower mean absolute error [24] [27].

Mechanistic interpretation of the models identified key molecular features that drive acute toxicity in rainbow trout. Critical descriptors included:

- Polarizability and Lipophilicity: These properties were highlighted as major drivers of toxicity, influencing chemical uptake and bioaccumulation [24].

- Electrotopological State Indices: These describe the electronic environment of specific atoms, reflecting interactions with biological targets [27].

- Presence of Chlorine Atoms and Rotatable Bonds: Structural features such as chlorine atoms and the number of rotatable bonds were significant in species-specific models, affecting reactivity and molecular flexibility [27].

- Van der Waals Volume and Hydrogen Bond Acceptors: Molecular size and the ability to form weak hydrogen bonds were also identified as influential factors [27].

The following table details key software, databases, and computational tools that are essential for replicating this chemical space analysis and modeling workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| alvaDesc | Software | Calculates molecular descriptors for QSAR and q-RASAR models, enabling exploration of structural diversity and mechanistic interpretation [26]. |

| SimilACTrail (in-house Python code) | Software/Custom Script | Maps the chemical space by analyzing Structure-Similarity Activity Trails; critical for visualizing clustering and scaffold diversity [24]. |

| PPDB (Pesticide Properties DataBase) | Database | Provides data for external validation and toxicity data gap filling for thousands of pesticides [24]. |

| PubChem | Database | A source of chemical structures and bioactivity data used for external validation sets [24]. |

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Database | Provides experimentally reported toxicity data (e.g., LC50, EC50) for various species, used for dataset curation [28]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Used for chemical structure standardization, descriptor calculation, and scaffold generation in computational pesticide studies [29] [30]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow and the logical relationship between chemical features and toxicity, as revealed by the study.

Diagram 1: SimilACTrail study workflow.

Diagram 2: Toxicity drivers and mechanisms.

This case study demonstrates that the SimilACTrail mapping approach provides a powerful framework for navigating the complex and largely unique chemical space of pesticides. By integrating this analysis with robust machine learning and q-RASAR models, the study offers a reliable, interpretable, and reproducible alternative to traditional fish toxicity testing [24]. The identification of key structural features like polarizability and lipophilicity delivers actionable insights for the rational design of next-generation pesticides that are effective yet environmentally benign.

The limitations of the work, including its focus on acute toxicity and the potential uncertainty for structurally novel pesticides, chart a course for future research [24]. Expanding these methodologies to chronic and mixture toxicity endpoints, and continuously refining the models with new data, will be crucial. Ultimately, this integrated cheminformatics workflow stands as a vital tool for supporting regulatory prioritization efforts under USEPA and ECHA frameworks, contributing to more sustainable environmental risk assessment and the strategic discovery of novel scaffolds [24].

The Methodological Toolkit: AI, Generative Models, and Quantum Computing for Scaffold Exploration

The pursuit of novel chemical entities is fundamentally constrained by the limitations of existing compound libraries. While high-throughput screening and virtual screening rely on predefined libraries, these represent an infinitesimal fraction of the estimated drug-like chemical space, which is projected to encompass up to 10^60 molecules [31]. This disparity has driven the emergence of computational de novo design as a transformative strategy to overcome this limitation by generating novel compounds from scratch based on the three-dimensional structure of a biological target [32]. Among the various methodologies, rule-based fragment assembly has proven particularly successful, combining principles from fragment-based drug design with computational efficiency and medicinal chemistry knowledge. This whitepaper examines two prominent platforms exemplifying this approach: the Systemic Evolutionary Chemical Space Explorer (SECSE) and LigBuilder V3. These platforms systemically navigate chemical space to discover novel, diverse small molecules that serve as attractive starting points for further experimental validation, thereby addressing a critical need in early-stage drug discovery against challenging targets [32] [18].

Rule-based fragment assembly platforms operate on the principle of constructing novel molecules within a protein's binding pocket through iterative modification of fragment starting points. This process miniaturizes a "Lego-building" approach, where fragments are strategically grown and optimized to enhance complementary interactions with the target [32]. The core components typically include a molecular generator, a fitness evaluator (often using molecular docking), and a selection mechanism (commonly a genetic algorithm) to triage promising candidates for the next generation [32] [31].

The following table provides a structured comparison of the two featured platforms, highlighting their distinct capabilities and design philosophies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of SECSE and LigBuilder V3 Platforms

| Feature | SECSE | LigBuilder V3 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Evolutionary fragment growing integrated with deep learning [32] | Multiple-purpose structure-based de novo design and optimization [33] |

| Key Construction Method | Knowledge-based transformation rules (growing, mutation, bioisostere, reaction) [32] | Growing, linking, merging; Chemical Space Exploring Algorithm [31] |

| Unique Capabilities | - Deep learning module for elite selection- Customizable rule database- Integration with multiple docking programs [34] [32] | - Multi-target drug design- Mimic design & lead optimization- Synthesis analysis & auto-recommendation [33] |

| Primary Use Case | Systemic chemical space exploration for novel hit-finding [32] | Versatile applications from de novo design to lead optimization and fragment linking [33] |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) | Filters for drug-likeness, rotatable bonds, ring properties, and synthetic accessibility score [34] | Retrosynthesis analysis integrated into the design process [31] |

Technical Architecture and Workflows

SECSE: Systemic Evolutionary Exploration

SECSE implements a computational search strategy conceptually inspired by fragment-based drug design. Its workflow is cyclical, leveraging a genetic algorithm to iteratively evolve populations of molecules toward improved fitness, evaluated primarily through molecular docking scores [32].

The platform's molecular generator employs a comprehensive set of over 3,000 knowledge-based transformation rules, strategically categorized into four types: growing rules (adding fragments to replaceable hydrogen atoms), mutation rules, bioisostere replacement rules, and reaction-based rules [32]. This rule-based approach provides a controlled yet creative exploration of chemical space, grounded in established medicinal chemistry principles.

Diagram Title: SECSE Workflow

The process initiates with the preparation of input fragments and the target protein structure. Fragments with fewer than 13 heavy atoms can be exhaustively enumerated to ensure diversity, though any defined structures or functional groups can serve as starting points [32]. These initial fragments are docked into the protein's binding pocket, and those demonstrating high docking scores or ligand efficiency are selected as elite candidates. The molecular generator then applies its transformation rules to these elites, creating a new generation of "child" molecules. These children undergo clustering and sampling to create a representative pool, which is then docked back into the pocket. Molecules that achieve high scores while maintaining reasonable 3D orientation (hereditary from parents) are selected as new elites. This evolutionary cycle repeats for multiple generations, accumulating a substantial number of compounds. To enhance efficiency, SECSE incorporates a graph-based machine learning module to accelerate the elite selection process in each iteration. Finally, the resulting hit compounds are visually inspected before selection for wet lab synthesis [32].

LigBuilder V3: A Multi-Purpose De Novo Design Approach

LigBuilder V3 is a versatile, multiple-purpose program for structure-based de novo drug design and optimization. Its architecture supports a wider range of specific design scenarios beyond general exploration, including lead optimization, fragment linking, and mimic design [33].

A key innovation in LigBuilder V3 is its Cavity module, which automatically detects and analyzes the ligand-binding site of a target protein, estimates its druggability, and can generate receptor-based pharmacophore models [33]. This provides a foundational understanding of the target environment before molecular construction begins.

Diagram Title: LigBuilder V3 Build Module

The Build module facilitates various design goals. Its de novo design mode uses a "Chemical Space Exploring Algorithm" that begins with minimal seed structures (e.g., a single sp3 carbon) and performs iterative growing and fragment extraction, avoiding reliance on pre-assigned seed structures for broader exploration [31]. For lead optimization, the platform can take known active compounds and systematically optimize them to improve activity. The fragment linking capability finds optimal ways to connect separate fragments that bind to different sub-pockets, integrating their pharmacophores into a single compound with enhanced affinity [33]. A particularly sophisticated feature is mimic design, which generates novel compounds that mimic known inhibitors through three strategies: automatically generating a biased scoring function based on known inhibitors, extracting and optimizing key fragments from them, and performing drug-like heterocycle ring replacements [33]. The platform also supports multi-target drug design, creating single ligands that effectively bind to multiple distinct receptor conformations or targets, supporting all its primary design modes [33].

Experimental Implementation and Protocols

SECSE Configuration and Execution