Beyond the Domain: Strategies to Overcome Applicability Domain Limitations in Modern QSAR Modeling

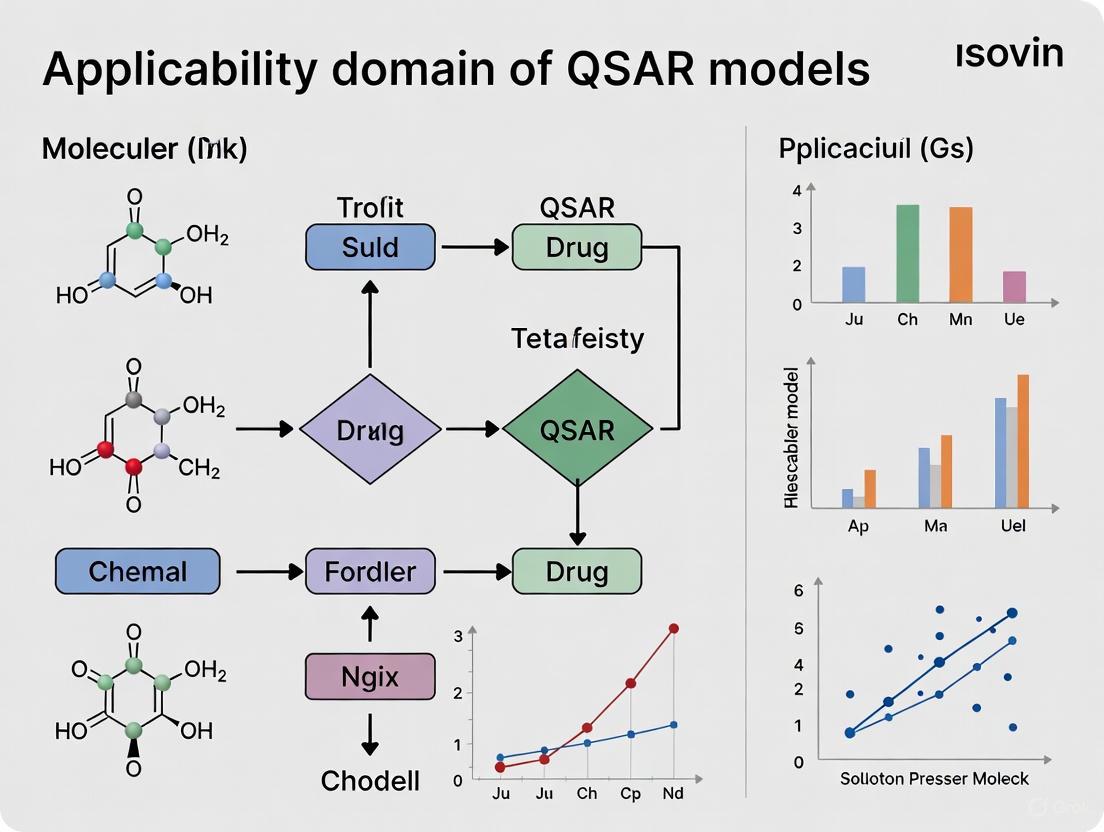

This article addresses the critical challenge of Applicability Domain (AD) limitations in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, a well-known constraint that confines model reliability to specific regions of chemical space.

Beyond the Domain: Strategies to Overcome Applicability Domain Limitations in Modern QSAR Modeling

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of Applicability Domain (AD) limitations in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, a well-known constraint that confines model reliability to specific regions of chemical space. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the foundational principles of AD, including the similarity principle and error-distance relationship. It provides a methodological review of current techniques for AD determination, from distance-based to advanced kernel density estimation. The article further investigates troubleshooting and optimization strategies to expand model domains and enhance predictive power, supported by validation frameworks and performance metrics tailored for real-world virtual screening tasks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodologies, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the tools to build more robust, reliable, and extensively applicable QSAR models for accelerated drug discovery.

The QSAR Applicability Domain: Understanding the Foundations and Core Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Applicability Domain (AD) and why is it a mandatory principle for QSAR models?

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the boundaries within which a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model's predictions are considered reliable [1]. It represents the chemical, structural, or biological space covered by the training data used to build the model [1]. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), defining the applicability domain is a mandatory principle for validating QSAR models for regulatory purposes [2] [3] [1]. Its core function is to estimate the uncertainty in the prediction of a new compound based on how similar it is to the compounds used to build the model [3]. Predictions for compounds within the AD are interpolations and are generally reliable, whereas predictions for compounds outside the AD are extrapolations and are considered less reliable or untrustworthy [3] [1].

Q2: My query compound is structurally similar to a training set molecule but received a high untrustworthiness score. What could be the cause?

This situation often arises from a breakdown of the "Neighborhood Behavior" (NB) assumption [4]. Neighborhood Behavior means that structurally similar molecules should have similar properties. A high untrustworthiness score in this context signals an "activity cliff" or "model cliff"—a pair of structurally similar compounds with unexpectedly different biological activities [5] [4]. From an operational perspective, your query compound might be:

- Located in a sparsely populated region of the training set's chemical space, even if a single neighbor is close [3].

- An outlier in the model's descriptor space, despite apparent structural similarity. The AD assessment is typically based on the model's descriptors, not raw chemical structures [3] [1].

- Affected by a correlation breakdown in one or more critical descriptors that the model relies on heavily [4].

Q3: What are the most common methods for determining the Applicability Domain, and how do I choose one?

There is no single, universally accepted algorithm for defining the AD, but several established methods are commonly employed [3] [1]. The choice often depends on the model's complexity, the descriptor types, and the regulatory context.

Table: Common Methods for Determining the Applicability Domain of QSAR Models

| Method Category | Description | Key Advantages | Common Algorithms/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range-Based | Defines the AD based on the minimum and maximum values of each descriptor in the training set. | Simple, intuitive, and computationally easy [3]. | Bounding Box [1]. |

| Distance-Based | Assesses the distance of a query compound from the training set compounds in the chemical space. | Intuitive; provides a continuous measure of similarity. | Euclidean Distance, Mahalanobis Distance [1], Leverage (from the hat matrix) [3] [1]. |

| Geometrical | Defines a geometrical boundary that encloses the training set compounds. | Can provide a more refined boundary than a simple bounding box. | Convex Hull [1]. |

| Probability Density-Based | Models the underlying probability distribution of the training set data. | Statistically robust; can identify dense and sparse regions in the chemical space. | Kernel-weighted sampling, Gaussian models [1]. |

| Standardization Approach | A simple method that standardizes descriptors and identifies outliers based on the number of standardized descriptors beyond a threshold [3]. | Easy to implement with basic software like MS Excel; a standalone application is available [3]. | "Applicability domain using standardization approach" tool [3]. |

Q4: How can I visually identify regions where my QSAR model performs poorly?

The visual validation of QSAR models is an emerging approach to address the "black-box" nature of complex models [5] [6]. By using dimensionality reduction techniques, you can project the chemical space of your validation set onto a 2D map.

- Procedure: Tools like MolCompass use a pre-trained parametric t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) model to create a 2D scatter plot where each point represents a compound, and structurally similar compounds are grouped together [5].

- Visualization: You can then color-code the points based on the model's prediction error (e.g., the difference between predicted and experimental values). Compounds or entire regions of the chemical space with large errors become immediately visible, revealing the model's weaknesses and "model cliffs" [5]. This graphical representation complements numerical AD methods by making it easier to interpret the model's performance across different chemical regions [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Chemicals Detected Outside the Applicability Domain

Problem: Your query chemical has been flagged as being outside the model's Applicability Domain, but you still need an estimate for your assessment.

Solution:

- Do Not Use the Prediction: The first and most critical step is to treat the prediction as unreliable and not use it for regulatory decisions or scientific conclusions [3] [7].

- Diagnose the Cause: Use the AD method's output to understand why the compound is outside the domain.

- If using a leverage-based approach, a high leverage value means the compound is extreme in the model's descriptor space, potentially exerting a strong influence on the model if it were part of the training set [3] [1].

- If using a distance-based method, a large distance to the nearest k neighbors indicates the compound is isolated in the chemical space and lacks sufficiently similar analogs in the training data [1].

- If using the standardization approach, a high number of standardized descriptors falling outside the ±3 standard deviation range pinpoints which specific descriptors are causing the issue [3].

- Seek Alternative Methods:

- Alternative (Q)SAR: Use a different QSAR model trained on a more relevant chemical domain [7].

- Weight of Evidence: Consider using the (Q)SAR prediction coupled with other data (e.g., from read-across, in vitro tests) in a "weight of evidence" approach to build a stronger case [7].

- Experimental Data: If possible and necessary, generate experimental data to fill the data gap [7].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Domain Estimation Across Different Tools

Problem: You run the same dataset through different AD estimation tools (e.g., a standalone tool vs. a KNIME node) and get different results for the same compounds.

Solution: This discrepancy is common because the AD is not a uniquely defined concept, and different tools implement different algorithms [1].

- Verify Algorithm Alignment: Ensure you understand the core algorithm used by each tool. For example, the "Enalos Domain –Similarity" node in KNIME is distance-based, while the "Enalos Domain – Leverages" node is leverage-based [3]. They measure different aspects of the chemical space and will naturally yield different results.

- Check Descriptor Consistency: Confirm that the exact same set of model descriptors, pre-processed in the same way (e.g., using the same scaling and normalization), is being used as input for all tools. Inconsistent descriptor input is a primary source of discrepant results.

- Establish a Consistent Benchmark: For your work, choose one primary AD method that is most suitable for your model type and use it consistently for all assessments. You can use a second method for confirmation, but your reporting should be based on the primary method.

Issue 3: Poor Model Reproducibility and Documentation

Problem: You are trying to reproduce a QSAR model from a scientific publication to verify its AD, but the documentation is insufficient.

Solution: This is a widespread issue, with one study finding that only 42.5% of QSAR articles were potentially reproducible [8].

- Request Missing Information: As a first step, contact the corresponding author of the publication to request the missing data (e.g., the exact chemical structures of the training set, the experimental endpoint values, the calculated descriptor values, or the full mathematical equation of the model) [8].

- Follow Best Practices for Your Own Reporting: To improve the field and the transparency of your own work, adhere to best practices for QSAR model reporting [8]. Ensure your documentation includes, at a minimum:

- Chemical Structures: Standardized structures for all training and test set compounds.

- Experimental Data: The experimental endpoint values for all compounds under the same conditions.

- Descriptor Values: The calculated values for all descriptors used in the final model.

- Algorithm and Parameters: The mathematical representation of the model and all software/algorithm parameters used.

- Predicted Values: The predicted activity/property values for all compounds.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Determining AD via the Standardization Approach

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing the simple yet effective standardization approach for AD determination [3].

Principle: A compound is considered outside the AD if it is an outlier in the model's descriptor space. This is identified by standardizing the model's descriptors for both training and test compounds and counting how many fall outside a defined range [3].

Table: Research Reagents & Software Solutions for Standardization AD

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Tools / Formula | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of the structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties of molecules. The raw input for the AD calculation. | Descriptors calculated by software like PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit [9]. | ||

| Standardization Formula | Transforms descriptors to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, allowing for comparison across different scales. | ( Ski = (Xki - \bar{X}i) / \sigma{Xi} ) where ( Ski ) is the standardized descriptor, ( Xki ) is the original value, ( \bar{X}i ) is the mean, and ( \sigma{Xi} ) is the standard deviation [3]. | ||

| AD Threshold | The cutoff value for defining an outlier descriptor. | A common threshold is | Ski | > 3 [3]. |

| Outlier Compound Criterion | The rule for flagging a compound as outside the AD. | If the number of its outlying descriptors ( | Ski | > 3) is greater than a predefined number (e.g., zero, meaning any outlier descriptor flags the compound) [3]. |

| Standalone Software | A dedicated application for performing this specific AD calculation. | "Applicability domain using standardization approach" tool [3]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Input Data: Compile a matrix containing the values of all 'n' descriptors (appearing in the QSAR model) for all 'm' training set compounds.

- Calculate Summary Statistics: For each descriptor (i) in the training set, calculate its mean (( \bar{X}i )) and standard deviation (( \sigma{Xi} )) [3].

- Standardize Training Set Descriptors: Apply the standardization formula to every descriptor value for every training set compound. This generates a matrix of standardized values, ( Ski ), for the training set [3].

- Identify Training Set Outliers (Optional): Scan the standardized training set matrix. Any training compound with one or more |Ski| > 3 can be considered an "X-outlier" and might be investigated for its influence on the model [3].

- Standardize Test/Query Compound Descriptors: For each new compound to be predicted, standardize its descriptor values using the mean and standard deviation obtained from the training set in Step 2.

- Apply AD Decision Rule: For each query compound, count the number of its standardized descriptors where |Ski| > 3. If this count is greater than a pre-defined threshold (e.g., zero), the compound is considered outside the AD of the model, and its prediction should not be trusted [3].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this process:

Protocol 2: Workflow for Visual Validation of the AD

This protocol uses chemical space visualization to qualitatively assess and interpret the Applicability Domain and model performance [5] [6].

Principle: A parametric t-SNE model is trained to project high-dimensional chemical descriptor data into a 2-dimensional space while preserving chemical similarity. This map allows researchers to visually inspect the distribution of training and test compounds and identify regions of poor prediction [5].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Curate a dataset of chemical structures (both training and test sets) and calculate a set of molecular descriptors [9] [5].

- Model Training (or Application): Train a parametric t-SNE model on the training set descriptors, or use a pre-trained model like the one in the MolCompass framework. This model is an artificial neural network that acts as a deterministic projector from the high-dimensional descriptor space to a 2D plane [5].

- Projection: Use the trained parametric t-SNE model to project all compounds (training, test, and new queries) onto the same 2D chemical map.

- Visual Validation:

- Color by Set: Use different colors for training and test compounds to see if the test set adequately covers the training chemical space.

- Color by Prediction Error: For the test set, color the points based on the magnitude of the prediction error. This instantly reveals "model cliffs"—areas where structurally similar compounds have high prediction errors [5].

- Define AD Visually: The densely populated areas of the training set can be interpreted as the core AD. Sparse regions or areas far from any training compound are visually identified as outside the AD.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the visual validation process:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Molecular Similarity Principle and how does it relate to the Applicability Domain (AD) of QSAR models?

The Molecular Similarity Principle is a foundational concept in cheminformatics which states that similar molecules tend to have similar properties [10] [11]. This principle is formally known as the similarity-property principle [11]. In the context of QSAR modeling, this principle provides the philosophical basis for defining the Applicability Domain (AD) [12]. The AD is the chemical space defined by the model's training set and the model's response to new compounds is reliable only when the new compounds are sufficiently similar to the training data. Predictions for molecules outside this domain, which are structurally dissimilar to the training set, are considered unreliable [13] [12].

Q2: My QSAR model performs well in cross-validation but fails to predict new compounds accurately. What is the most likely cause?

The most probable cause is that the new compounds you are trying to predict fall outside the Applicability Domain of your model [14] [12]. Cross-validation primarily tests a model's internal consistency, but does not guarantee its predictive power for entirely new chemical scaffolds [14]. The prediction error of QSAR models generally increases as the chemical distance to the nearest training set molecule increases [15]. To diagnose this, you should implement an AD method to determine if your new compounds are indeed too dissimilar from your training set.

Q3: Why do some modern machine learning models for image recognition seem to extrapolate successfully, while QSAR models are strictly limited to their applicability domain?

This discrepancy arises from the fundamental nature of the problems, not just the algorithms. In image recognition, images from the same class (e.g., different Persian cats) can be as pixel-dissimilar as images from different classes (e.g., a cat and an electric fan) [15]. The model must learn high-level, abstract features to succeed. In QSAR, the relationship between structure and activity is often more direct and localized in chemical space, adhering strongly to the similarity principle [15]. However, evidence suggests that with more powerful algorithms and larger datasets, the performance of QSAR models can also improve in regions distant from the training set, effectively widening their applicability domain [15].

Q4: What are the practical consequences of making predictions outside a model's Applicability Domain?

Predictions made outside the AD are highly prone to large errors and unreliable uncertainty estimates [13]. For instance, in potency prediction (pIC50), the mean-squared error can increase from an acceptable 0.25 (corresponding to ~3x error in IC50) for in-domain compounds to 2.0 (corresponding to a ~26x error in IC50) for out-of-domain compounds [15]. This level of inaccuracy is sufficient to misguide a lead optimization campaign, wasting significant synthetic and assay resources.

Q5: Is the Tanimoto coefficient on Morgan fingerprints the only way to define the Applicability Domain?

No, it is one of the most common methods, but it is not the only one. The AD can be defined using a variety of chemical distance metrics and statistical methods [13] [12]. Other fingerprint types (e.g., atom-pair, path-based), kernel density estimation (KDE) in feature space, Mahalanobis distance, convex hull approaches, and leverage are all valid techniques [13] [15] [16]. The choice of method depends on the model and the nature of the chemical space.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Prediction Error on New Data

Symptoms: A QSAR model shows low cross-validation errors but exhibits high residuals when predicting new, external compounds.

Diagnosis and Solution Flowchart:

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Procedures:

- Quantify Similarity: Calculate the distance from the new compound to the training set. A common method is to compute the Tanimoto distance on Morgan fingerprints to the nearest neighbor in the training set [15].

- Apply AD Threshold: Compare the calculated distance to a pre-defined threshold. A typical starting threshold for Tanimoto similarity is 0.4 to 0.6, but this should be validated for your specific dataset [15]. If the distance is larger than the threshold, the compound is Out-of-Domain (OD).

- Interpret Results:

- If OD: The high error is expected. The solution is to expand the training set with compounds that are chemically similar to the new compounds you wish to predict [13].

- If In-Domain (ID): The model itself may be inadequate. Consider improving the model by using more sophisticated machine learning algorithms, trying different molecular descriptors, or gathering more bioactivity data for the existing chemical space [15].

Problem: Defining the Applicability Domain for a New QSAR Model

Symptoms: You have built a QSAR model and need to establish a reliable method to flag future predictions as reliable or unreliable.

Solution: Several methodologies exist. The following table compares common approaches for defining the AD.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Defining the Applicability Domain (AD) of QSAR Models

| Method | Brief Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-Based (e.g., Tanimoto) | Measures the distance (e.g., Tanimoto) in fingerprint space between a new compound and its nearest neighbor in the training set [15] [12]. | Intuitive, fast to compute, directly tied to the similarity principle. | Requires choosing a threshold; may not capture complex data distributions [13]. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) | A statistical method that models the probability density of the training data in feature space. A new sample is assessed based on its likelihood under this model [13]. | Accounts for data sparsity; handles arbitrarily complex geometries of ID regions; no pre-defined shape for the domain [13]. | Can be computationally intensive for very large datasets. |

| Leverage & PCA | Based on the concept of the optimal prediction space, it uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and measures the leverage of a new sample [12] [17]. | Well-established statistical foundation; good for descriptor-based models. | The convex hull of training data can include large, empty regions with no training data [13]. |

| Consensus/Ensemble Methods | Combines multiple AD definitions (e.g., leveraging, similarity, residual) to provide a more robust assessment [12]. | Systematically better performance than single methods; more reliable outlier detection [12]. | Increased complexity of implementation. |

Recommended Protocol for Initial AD Implementation:

- Represent Molecules: Encode your training and test molecules using a relevant fingerprint (e.g., ECFP/Morgan fingerprints) or molecular descriptor set [15] [11].

- Calculate Training Distances: For each molecule in the training set, calculate its distance (e.g., Tanimoto distance) to every other training molecule. Establish a threshold (e.g., the 5th percentile of nearest-neighbor distances in the training set) or use a predefined value (e.g., 0.4) [15].

- Validate the AD Definition: Perform external validation with a test set. Plot the model's prediction error (e.g., residual magnitude) against the calculated dissimilarity measure. A well-defined AD will show a strong correlation between high error and high dissimilarity [13].

- Deploy for Prediction: For any new compound, calculate its distance to the nearest training set molecule. If the distance exceeds your threshold, flag the prediction as "Outside AD - Use with Caution".

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for AD Analysis in QSAR

| Tool / Resource | Function in AD Analysis | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ECFPs) | Molecular Representation | A circular fingerprint that identifies the set of radius-n fragments in a molecule, providing a bit-string representation used for similarity calculations [15]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | Similarity/Distance Metric | The most popular similarity measure for comparing chemical structures represented by fingerprints. It is calculated as the size of the intersection divided by the size of the union of the fingerprint bits [15] [11]. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) | Probabilistic Domain Assessment | A non-parametric way to estimate the probability density function of the training data in feature space. It is used to identify regions with low data density as out-of-domain [13]. |

| Applicability Domain using the Rivality Index (ADAN) | Advanced Domain Classification | A method that calculates a "rivality index" for each molecule, estimating its chance of being misclassified. Molecules with high positive RI values are considered outside the AD [12]. |

| Autoencoder Neural Networks | Spectral/Feature Space Reconstruction | Used to define the AD of neural network models, particularly with spectral data. A high spectral reconstruction error indicates the sample is anomalous and outside the AD [16]. |

A foundational observation in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is that the error of a prediction tends to increase as the chemical's distance from the model's training data grows [18]. This robust relationship holds true across various machine-learning algorithms and molecular descriptors [18]. Understanding and managing this phenomenon is crucial for developing reliable models, and it is intrinsically linked to the concept of the Applicability Domain (AD)—the chemical space within which the model's predictions are considered reliable [1].

This technical guide addresses frequent questions and provides methodologies to help researchers diagnose, visualize, and mitigate errors related to the applicability domain in their QSAR workflows.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my QSAR model make inaccurate predictions for some chemicals, even with high internal validation scores?

This common issue often arises when the chemical being predicted falls outside your model's Applicability Domain (AD).

- Problem Explanation: A model is primarily valid for interpolation within the chemical space defined by its training data; predictions for chemicals outside this space are extrapolations and tend to be less reliable [1]. The prediction error has been shown to correlate well with a chemical's distance from the training set [19] [18]. High internal validation scores do not guarantee model performance on entirely new types of chemicals.

- Solution:

- Define your Applicability Domain: Always characterize the AD of your model. Common methods include range-based methods (bounding box), distance-based methods (Euclidean, Mahalanobis, or Tanimoto distance to training set), or leverage-based methods [1].

- Use Advanced Distance Metrics: Consider implementing the Sum of Distance-Weighted Contributions (SDC), a Tanimoto distance-based metric that considers contributions from all molecules in the training set. Studies show SDC correlates highly with prediction error and can outperform simpler distance-to-model metrics [19].

- Estimate Error Bars: Use the SDC metric to build a robust root mean squared error (RMSE) model. This allows you to provide an individual RMSE estimate for each prediction, giving a quantitative sense of its reliability [19].

FAQ 2: How can I visually determine if a new chemical is within my model's applicability domain?

While visual assessment has limits, you can use a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) plot to get a two-dimensional projection of the chemical space.

- Problem Explanation: The applicability domain is a multi-dimensional concept. A PCA plot provides a simplified, albeit incomplete, view of this space.

- Solution & Workflow:

- Compute Descriptors: Calculate the same molecular descriptors used in your QSAR model for both the training set and the new target chemical(s).

- Perform PCA: Conduct a PCA on the descriptor data for the training set and project the new chemical(s) onto the same principal components.

- Generate Plot: Create a scatter plot of the first two principal components (PC1 vs. PC2).

- Interpret Results: A target chemical that falls within the dense cluster of training compounds is likely within the AD. A chemical located in a sparsely populated or empty region of the plot is likely outside the AD, and its prediction should be treated with caution. The diagram below illustrates this workflow.

FAQ 3: My model's applicability domain method isn't flagging unreliable predictions. What's wrong?

Standard Applicability Domain methods may be overly optimistic. Recent research calls for more stringent analysis.

- Problem Explanation: Standard AD algorithms can erroneously tag predictions as reliable. These errors often occur in specific subspaces (cohorts) with high prediction error rates, highlighting the inhomogeneity of the AD space [20]. The reliability of the AD method itself is often not validated.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Error Analysis: Apply tree-based error analysis workflows to identify cohorts within your AD with the highest prediction error rates [20].

- Rigorously Validate your AD Method: The selected AD method should be rigorously validated to demonstrate its suitability for the specific model and chemical space [20].

- Use Ensemble Methods: The variance of predictions from an ensemble of QSAR models can serve as a useful AD metric and may sometimes outperform distance-to-model metrics [19].

Experimental Protocols for Error-Distance Analysis

Protocol 1: Implementing the Sum of Distance-Weighted Contributions (SDC) Metric

This protocol details how to use the SDC metric to estimate prediction errors for individual molecules [19].

- Objective: To calculate a canonical distance-based metric that correlates with QSAR prediction error and provides an individual RMSE estimate for each molecule.

- Materials: A curated training set of chemicals with known activities and a set of target chemicals for prediction.

- Methodology:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute a defined set of molecular descriptors for all chemicals in the training and target sets.

- SDC Calculation: For each target chemical, calculate its SDC value. This metric takes into account contributions from all molecules in the training set, weighted by their Tanimoto distance to the target.

- Model Building: Develop a robust RMSE model based on the correlation between the SDC values and the observed prediction errors from model validation.

- Error Estimation: For a new prediction, use its SDC value and the RMSE model to provide an individual error estimate.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Prediction Reliability

| Metric | Description | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Distance-Weighted Contributions (SDC) | A Tanimoto distance-based metric considering all training molecules. | High correlation with prediction error; enables individual RMSE estimates. | [19] |

| Mean Distance to k-Nearest Neighbors | Mean distance to the k closest training set compounds. | Intuitive; widely used. | [19] [1] |

| Ensemble Variance | Variance of predictions from an ensemble of models. | Does not rely on input descriptors; can outperform simple distance metrics. | [19] |

| Leverage (from Hat Matrix) | Identifies influential chemicals in regression-based models. | Useful for defining structural AD in linear models. | [1] |

Protocol 2: Tree-Based Error Analysis for Applicability Domain Refinement

This protocol uses error analysis to identify weak spots within the nominal applicability domain [20].

- Objective: To identify cohorts of chemicals within the AD that have high prediction error rates, thereby refining the understanding of the model's reliable space.

- Materials: A validated QSAR model and a test set with known experimental values.

- Methodology:

- Generate Predictions: Use your QSAR model to predict activities for the test set.

- Calculate Prediction Errors: Compute the absolute error for each chemical in the test set.

- Build Error Tree: Using the molecular descriptors, build a decision tree to predict the absolute error of each chemical. The tree will split the chemical space into cohorts based on descriptor thresholds.

- Identify High-Error Cohorts: Analyze the resulting tree to identify the cohorts (leaf nodes) with the highest mean absolute error. These are regions where the AD method may be failing, and predictions are less reliable, even if the chemical is nominally "within" the AD.

- Rational Model Refinement: Focus data expansion and model retraining efforts on these high-error cohorts to improve the model iteratively [20].

The following diagram maps the logical relationship of this refinement cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Metrics for QSAR Applicability Domain Analysis

| Tool / Metric | Function in Error-Distance Analysis |

|---|---|

| SDC Metric | Provides a canonical distance measure to estimate individual prediction errors for any machine-learning method [19]. |

| Tree-Based Error Analysis | Identifies subspaces with high prediction error rates within the nominal applicability domain, enabling rational model refinement [20]. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | A comprehensive software that supports profiling, data collection, and read-across, including functionalities for assessing category consistency and applicability [21]. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL, Dragon) | Generates the numerical molecular descriptors required for calculating distances and defining the chemical space [9]. |

FAQs: Understanding Applicability Domain (AD) and the Chemical Space Problem

Q1: What is the Applicability Domain (AD) of a QSAR model, and why is it a problem in drug discovery?

The Applicability Domain (AD) is the region of chemical space surrounding the compounds with known experimental activity that were used to train a QSAR model. Within this domain, models are trusted to make accurate predictions, primarily through interpolation between known data points [15]. The fundamental problem is that the vast majority of synthesizable, drug-like compounds are distant from any previously tested compound. One analysis showed that for common kinase targets, most drug-like compounds have a Tanimoto distance on Morgan fingerprints greater than 0.6 to the nearest tested compound. If models are restricted to a conservative AD, they cannot access this vast chemical space, severely limiting their utility for exploring new lead molecules [15].

Q2: How is "distance" from the training set typically measured in QSAR?

The most common approaches involve calculating the Tanimoto distance on molecular fingerprints, such as Morgan fingerprints (ECFP). This distance roughly represents the percentage of molecular fragments present in only one of two molecules [15]. Other methods include:

- Distance-based methods: Measuring the distance to the nearest training set compound or the centroid of the training set [12].

- Density-based methods: Using techniques like Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to assess if a new compound lies in a region of feature space that is well-populated by the training data [13].

- Model-specific methods: Such as leverage or DModX [12].

Q3: My model is highly accurate on the test set, but fails on new, seemingly similar compounds. Could this be an OOD problem?

Yes. A model's performance on a standard test set, which is often randomly split from the original data, only evaluates its ability to interpolate. Real-world chemical datasets often have a clustered structure. A random split can leave these clusters intact, making prediction seem easy. The true test of a model is its ability to predict compounds that are structurally distinct from the training set (e.g., based on different molecular scaffolds), which is a form of extrapolation. Error robustly increases with distance from the training set, so your new compounds are likely OOD, where the model is inherently less accurate [15].

Q4: What is the difference between OOD detection in general machine learning and AD in QSAR?

In conventional ML tasks like image recognition, models based on deep learning must and can extrapolate successfully. For example, image classifiers can correctly identify a Persian cat even if it looks very different from any cat in the training set in terms of pixel space [15]. In contrast, traditional QSAR models have been confined to interpolation within a defined AD. This disconnect suggests that with more powerful algorithms and larger datasets, better extrapolation for QSAR may be possible [15]. The term OOD detection is now commonly used in deep learning to identify inputs that are statistically different from the training data, which is the same fundamental concept as the AD [22].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: High Prediction Error on New Compound Scaffolds

Problem: Your QSAR model performs well on compounds similar to the training set but shows high errors when predicting compounds with new core structures (scaffolds).

Diagnosis: This is a classic scaffold-based extrapolation failure, where the new scaffolds place the compounds outside the model's applicability domain [15].

Solution:

- Quantify the Distance: Calculate the Tanimoto distance (or your preferred distance metric) between the new scaffold and the nearest compound in your training set. A high distance (e.g., >0.6 for Tanimoto on ECFP) confirms the OOD issue [15].

- Implement a Formal AD Method: Don't rely on intuition. Integrate an AD method into your workflow.

- Simple Method: Use the distance to nearest neighbor in the training set and set a threshold based on the model's error profile [12].

- Advanced Method: Employ a consensus or density-based approach like Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) on the feature space to define complex, multi-faceted AD boundaries [13].

- Action: Flag all predictions for compounds that fall outside the defined AD as unreliable. Do not use these predictions to guide chemical synthesis without strong experimental validation.

Issue 2: Unreliable Uncertainty Estimates for OOD Compounds

Problem: Your model's built-in uncertainty quantification (UQ) is not reliable. It sometimes assigns high confidence to incorrect predictions for OOD compounds.

Diagnosis: Standard deterministic models are often poorly calibrated and can be overconfident on OOD data [23]. The uncertainty estimates do not accurately reflect the true prediction error.

Solution:

- Switch to Uncertainty-Aware Models: Use modeling techniques that provide better uncertainty estimates.

- Deep Ensembles: Train multiple deep learning models with different random initializations. The disagreement (variance) between their predictions is a powerful measure of uncertainty. High disagreement often indicates OOD samples [23].

- Gaussian Processes: These models naturally provide a predictive variance along with the prediction.

- Use Uncertainty for OOD Detection: Actively use the predictive uncertainty to detect OOD samples. Set a threshold on the uncertainty; any input causing uncertainty above this threshold is classified as OOD, and its prediction is considered untrustworthy [23].

Issue 3: Determining if a Dataset is Suitable for Model Building

Problem: Before investing time in building a model, you want to know if the dataset has inherent properties that will lead to a robust model with a wide AD.

Diagnosis: Some datasets are inherently more "modelable" than others due to the underlying structure-activity relationship.

Solution:

- Calculate Dataset Modelability Index (MODI): This pre-modeling metric assesses the degree of overlap between active and inactive compounds in the chemical space. A high MODI suggests a clear structure-activity relationship is present and a reliable model can be built [12].

- Calculate the Rivality Index (RI): For each compound, the RI measures its propensity to be correctly classified. Compounds with high positive RI values are likely to be outliers or near the AD boundary. A dataset with many high-RI compounds may produce a model with a narrow AD [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Establishing the Applicability Domain using Distance and Density Metrics

Objective: To define a robust applicability domain for a QSAR regression model to flag unreliable predictions.

Materials:

- Training set molecular descriptors (

X_train) - Test compound descriptors (

X_test) - A fitted QSAR model (

M_prop)

Methodology:

- Feature Space Definition: Use the same molecular descriptors (e.g., ECFP fingerprints or a set of physicochemical descriptors) used to build the QSAR model.

- Calculate Dissimilarity:

- Step 2.1 (Distance-based): For each test compound

t_iinX_test, compute its distance to the nearest neighbor inX_train. The Tanimoto distance is standard for fingerprints [15]. - Step 2.2 (Density-based): Fit a Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) model on the

X_traindata. Use the KDE to calculate the log-likelihood for eacht_i, which represents how "typical" it is of the training distribution [13].

- Step 2.1 (Distance-based): For each test compound

- Set Thresholds:

- Analyze the distribution of distances/KDE log-likelihoods for the training set itself.

- Set a threshold (e.g., the 5th percentile of training set KDE scores) below which a test compound is considered OOD [13].

- Application: For any new compound, calculate its dissimilarity score. If the score is worse (higher distance or lower density) than the threshold, classify its prediction as OOD and untrustworthy.

The following workflow visualizes this protocol:

Protocol 2: OOD Detection for Classification using Uncertainty-Aware Deep Learning

Objective: To detect OOD samples (e.g., compounds with novel mechanisms or scaffolds) using predictive uncertainty from a deep learning classifier.

Materials:

- A dataset of known compounds and their activity classes (ID data).

- A deep learning architecture (e.g., a Graph Neural Network).

Methodology:

- Train an Ensemble:

- Train

N(e.g., 5) instances of your deep learning model on the same ID training data, but with different random seeds for weight initialization. This creates a deep ensemble [23].

- Train

- Define Uncertainty Metric:

- For a given input compound, each model in the ensemble outputs a predicted class probability vector.

- Calculate the predictive entropy (or the variance across models) as the measure of uncertainty. High entropy indicates high uncertainty [23].

- Calibrate the Uncertainty Threshold:

- Use a separate validation set (comprising only ID data) to determine a baseline level of uncertainty.

- Set an uncertainty threshold that accepts a desired level of ID data (e.g., 95%) [23].

- Deployment and Detection:

- For a new compound, pass it through the ensemble.

- Calculate the average prediction (for the class) and the predictive entropy.

- If the entropy is above the threshold, classify the compound as OOD and do not trust the predicted activity class.

Data Presentation: Error vs. Chemical Distance

Table 1: Relationship Between Tanimoto Distance and QSAR Model Prediction Error (Log IC50) [15]

| Tanimoto Distance to Training Set (Approx. Quantile) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) of Log IC50 | Typical Error in IC50 | Interpretation for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close (Low distance) | ~0.25 | ~3x | Sufficiently accurate for hit discovery & lead optimization. |

| Medium | ~1.0 | ~10x | Can distinguish potent from inactive, but less precise. |

| Far (High distance) | ~2.0 | ~26x | Generally unreliable for guiding chemical optimization. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for AD and OOD Analysis

| Tool / Algorithm Category | Specific Examples | Function in AD/OOD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP), Atom-Pair Fingerprints, Path-based Fingerprints [15] | Encode molecular structure into a numerical vector for calculating chemical similarity and distance. |

| Distance Metrics | Tanimoto Distance, Euclidean Distance, Mahalanobis Distance [15] [13] | Quantify the similarity or dissimilarity between two compounds in a defined chemical space. |

| Density Estimation Methods | Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [13] | Models the probability density of the training data in feature space to identify sparse or OOD regions. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Methods | Deep Ensembles [23], Gaussian Processes | Provides a measure of the model's confidence in its predictions, which can be used to detect OOD samples. |

| Pre-modeling Metrics | Modelability Index (MODI), Rivality Index (RI) [12] | Assesses the inherent "modelability" of a dataset and identifies potential outliers before model building. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is my QSAR model unreliable for predicting the activity of novel scaffold compounds? Your model is likely operating outside its Applicability Domain (AD). QSAR models are fundamentally tied to the chemical space of their training data. Predictions for molecules that are structurally dissimilar to the training set compounds (high Tanimoto distance) are extrapolations and come with significantly higher error rates [15]. For instance, a mean-squared error (MSE) on log IC50 can increase from 0.25 (typical of ~3x error in IC50) for similar molecules to 2.0 (typical of ~26x error in IC50) for distant molecules [15].

2. Can't powerful ML algorithms like Deep Learning overcome the interpolation limitation in QSAR? While deep learning has shown remarkable extrapolation in fields like image recognition, its application to small molecule prediction often still conforms to the similarity principle. Evidence shows that even modern deep learning algorithms for QSAR exhibit a strong, robust trend of increasing prediction error as the distance to the training set grows [15]. The key is that image recognition models learn high-level, semantic features (e.g., "cat ears"), allowing them to recognize these concepts in novel pixel arrangements. In contrast, many QSAR approaches rely on chemical fingerprints where distance directly correlates with structural similarity [15].

3. My random forest model cannot predict values higher than the maximum in the training set. Is it broken? No, this is expected behavior. Methods like Random Forest (RF) are inherently incapable of predicting target values outside the range of the training set because they make predictions by averaging the outcomes from individual decision trees [24] [25]. For extrapolation tasks, you need to consider alternative formulations or algorithms.

4. What is a practical method for defining the Applicability Domain of my model? A straightforward and statistically sound method is the standardization approach. It involves standardizing the descriptors of the training set and calculating the mean and standard deviation for each. For any new compound, its standardized values are computed using the training set's parameters. A compound is considered outside the AD if the absolute value of any of its standardized descriptors exceeds a typical threshold, often set at 3 (analogous to a z-score) [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Performance in Lead Optimization

Description: The model fails to identify new compounds with higher potency (activity) than any existing in the training set, which is the core goal of lead optimization.

Diagnosis: This is a classic extrapolation problem (type two), where the goal is to predict activities (y) beyond the range in the training data [24] [25]. Standard regression models are often poorly suited for this task.

Solution: Implement a Pairwise Approach (PA) formulation.

- Concept: Instead of learning a univariate function

f(drug) → activity, learn a bivariate functionF(drug1, drug2) → signed difference in activity[24] [25]. - Rationale: This reformulates the problem to focus on ranking and comparing pairs of drugs, which is more aligned with the goal of finding the best candidates.

- Implementation:

- Data Generation: Create a new dataset where each sample is a pair of compounds, and the target variable is the difference in their activity values.

- Model Training: Train a model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on this pairwise data. Siamese Neural Networks are a popular architecture for this [24].

- Ranking: Use the trained pairwise model to compare new candidate compounds against known ones. Employ a ranking algorithm to sort all compounds (training and test) based on the predicted pairwise differences [24] [25].

- Result: This approach has been shown to "vastly outperform" standard regression in identifying top-performing and extrapolating compounds [25].

Problem: High Prediction Error for Structurally Novel Compounds

Description: Model predictions are accurate for close analogs but become highly unreliable for chemistries not well-represented in the training data.

Diagnosis: The query compounds are outside the model's Applicability Domain (AD).

Solution: Conduct a formal Applicability Domain analysis.

- Concept: The AD is the "physico-chemical, structural, or biological space" on which the model was trained. Predictions are only reliable for compounds within this domain [3].

- Methodology (Standardization Approach) [3]:

- Standardize the model descriptors for the training set compounds using the formula:

S_ki = (X_ki - X̄_i) / σ_iwhereS_kiis the standardized descriptorifor compoundk,X_kiis the original descriptor value,X̄_iis the mean of descriptoriin the training set, andσ_iis its standard deviation. - For any new compound, calculate its standardized descriptors using the same

X̄_iandσ_ifrom the training set. - Define a threshold (e.g., ±3). If the absolute value of any standardized descriptor for the new compound exceeds this threshold, it is flagged as being outside the AD, and its prediction should be considered unreliable.

- Standardize the model descriptors for the training set compounds using the formula:

- Alternative Methods: Other AD methods include leverage-based approaches, Euclidean distance, and probability density distribution [3] [26].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Error vs. Distance to Training Set in QSAR vs. Image Recognition

| Field / Task | ML Algorithm | Distance Metric | Trend in Prediction Error | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR / Drug Potency [15] | RF, SVM, k-NN, Deep Learning | Tanimoto Distance (on Morgan Fingerprints) | Strong increase with distance | Models are constrained to interpolation within a chemical applicability domain. |

| Image Recognition [15] | ResNeXt (Deep Learning) | Euclidean Distance (in Pixel Space) | No correlation with distance | Models can extrapolate effectively, as performance is based on high-level features, not pixel proximity. |

Table 2: Extrapolation Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms

| Algorithm | Extrapolation Capability | Key Limiting Factor / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) [24] [25] [27] | Poor | Cannot predict beyond the range of training set y-values due to averaging. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) [27] | Limited | Less stable in extrapolation, performance depends on kernel. |

| Gaussian Process (GPR) [27] | Moderate | Some potential with appropriate kernel selection; provides uncertainty estimates. |

| Decision Trees, XGBoost, LightGBM [27] | Poor | Tree-based models generally struggle with extrapolation. |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) [28] | Good (Contextual) | Can outperform convolutional networks (CNNs) in extrapolation for some tasks (e.g., nanophotonics). |

| Pairwise Formulation [24] [25] | Excellent | Reformulates the problem, enabling top-rank extrapolation by focusing on relative differences. |

Protocol 1: Implementing the Pairwise Approach for Extrapolation

This protocol is adapted from studies that applied the pairwise formulation to thousands of drug design datasets [24] [25].

Data Preparation:

- Represent each drug molecule using a molecular fingerprint (e.g., 1024-bit Morgan fingerprint, radius 2) [25].

- Define the target variable as

pXC50(-log of the measured activity).

Generate Pairwise Dataset:

- From your training set of

Ncompounds, create a new dataset of compound pairs. - For each pair (i, j), the input feature is the difference between their feature vectors:

Δx = x_i - x_j. - The target variable is the signed difference in their activity:

Δy = y_i - y_j.

- From your training set of

Model Training:

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, or Gradient Boosting Machine) to learn the function:

F(Δx) → Δy. - Alternatively, a Siamese Neural Network architecture can be used, which processes two inputs through identical subnetworks [24].

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, or Gradient Boosting Machine) to learn the function:

Ranking for Prediction:

- To rank a set of compounds (including both training and novel test compounds), use a ranking algorithm.

- The pairwise model

Fis used to compare compounds, and the resulting matrix of predicted differences is processed to produce a global ranking, identifying those predicted to have the highest activity [24] [25].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Extrapolation Performance

Data Splitting:

Define Metrics:

- Extrapolation Metric: The ability to identify test set examples with true activity values greater than the maximum value (

y_train,max) in the training set [24]. - Top-Performance Metric: The ability to rank true top-performing test samples (e.g., within the top 10% of the entire dataset) highly [24] [25].

- Extrapolation Metric: The ability to identify test set examples with true activity values greater than the maximum value (

Validation:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation using this sorted/split strategy to obtain a robust estimate of the model's extrapolation capability [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for QSAR Modeling and AD Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP) [15] | A standard method to convert molecular structure into a fixed-length binary vector (bit-string) representing the presence of substructural features. Serves as the primary input feature for many QSAR models. |

| Tanimoto Distance [15] | A similarity metric calculated between Morgan fingerprints. Used to quantify the structural distance of a query molecule to the nearest compound in the training set, which is core to defining the AD. |

| Standardization Approach Algorithm [3] | A simple, statistically based method for determining the Applicability Domain by standardizing model descriptors and flagging compounds with out-of-range values. |

| Siamese Neural Network [24] | A neural network architecture designed to compare two inputs. It is particularly well-suited for implementing the pairwise approach (PA) in QSAR. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox [29] | A software tool that provides a comprehensive workflow for (Q)SAR model building, validation, and includes features for assessing the Applicability Domain. |

Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

Pairwise Approach Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for implementing the Pairwise Approach to QSAR, which enhances extrapolation performance.

Error vs. Distance Relationship

This diagram contrasts the fundamental relationship between prediction error and distance from the training data in QSAR versus Image Recognition tasks.

A Practical Guide to Applicability Domain Determination Methods

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of defining an Applicability Domain (AD) in a QSAR model? The Applicability Domain defines the boundaries within which a QSAR model's predictions are considered reliable. It ensures that predictions are made only for new compounds that are structurally similar to the chemicals used to train the model, thereby minimizing the risk of unreliable extrapolations. According to OECD validation principles, defining the AD is a mandatory step for creating a QSAR model fit for regulatory purposes [30] [1] [31].

Q2: When should I use a Bounding Box over a Convex Hull method? The Bounding Box is a simpler and computationally faster method, making it a good choice for an initial, rapid assessment of your model's AD. However, it is less accurate as it cannot identify empty regions within the defined hyper-rectangle. The Convex Hull provides a more precise definition of the training space's outer boundaries but becomes computationally prohibitive with high-dimensional data. It is best used when the number of descriptors is very low (e.g., 2 or 3) and computational complexity is not a concern [30] [1].

Q3: What does a 'high leverage' value indicate for a query compound? A high leverage value for a query compound signifies that it is far from the centroid of the training data in the model's descriptor space. Such a compound is considered an influential point and may be an outlier. Predictions for high-leverage compounds should be treated with caution, as they represent extrapolations beyond the model's established domain. A common threshold is the "warning leverage," set at three times the average leverage of the training set (p/n, where p is the number of model descriptors and n is the number of training compounds) [30].

Q4: A compound falls within the PCA Bounding Box but is flagged as an outlier by the leverage method. Why does this happen? This discrepancy occurs because the PCA Bounding Box only checks if the compound's projection onto the Principal Components falls within the maximum and minimum ranges of the training set. It does not account for the data distribution within that box. The leverage method (based on Mahalanobis distance), however, considers the correlation and density of the training data. A compound could be within the overall range (PCA Bounding Box) but located in a sparse region of the chemical space that was not well-represented in the training set, leading to a high leverage value [30].

Q5: What are the most common reasons for a large proportion of my test set falling outside the defined AD? This typically indicates a significant mismatch between the chemical spaces of your training and test sets. Common causes include:

- Insufficiently Representative Training Set: The training set does not cover the structural diversity present in the test set.

- Incorrect Descriptor Choice: The selected descriptors fail to capture the relevant structural features that define similarity for your specific endpoint.

- Overly Restrictive AD Thresholds: The criteria for being "inside" the domain (e.g., the distance threshold) may be set too strictly. The chosen AD method itself might be too simplistic (e.g., a standard Bounding Box) for the complexity of your data [30] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The Convex Hull method fails to produce a result or takes an extremely long time.

- Cause: The computational complexity of calculating a Convex Hull increases exponentially with the number of dimensions (descriptors). For typical QSAR models with dozens of descriptors, the calculation becomes intractable [30].

- Solution:

- Reduce Dimensionality: Apply feature selection or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of dimensions to 3 or fewer before constructing the Convex Hull.

- Use an Alternative Method: Switch to a less computationally intensive AD method. A PCA Bounding Box or a distance-based method like leverage or k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) are practical alternatives for high-dimensional data [30] [32].

Problem: The Bounding Box method accepts compounds that are clear outliers.

- Cause: The standard Bounding Box only considers the range of each descriptor independently. It cannot account for correlations between descriptors or identify "holes" within the hyper-rectangle where no training data exists [30].

- Solution:

- Use PCA Bounding Box: This method rotates the axes to align with the directions of maximum variance, partially accounting for descriptor correlations.

- Implement a Distance-Based Method: Incorporate the Mahalanobis distance or leverage, which are sensitive to the correlation structure of the training data. A compound might be within the range for each descriptor but still be far from the data centroid in the multivariate space [30].

- Combine Methods: Define the AD using a combination of a Bounding Box (for a quick check) and a leverage threshold (for a more refined assessment).

Problem: Inconsistent AD results are obtained when using different descriptor sets for the same model.

- Cause: The Applicability Domain is defined in the context of the specific descriptors used to build the model. Different descriptor sets represent different chemical spaces, so the resulting ADs will naturally differ [1].

- Solution:

- Use a Robust Descriptor Set: Ensure the selected descriptors are relevant, non-redundant, and meaningfully related to the endpoint being modeled.

- Document the Context: Always report the AD method in conjunction with the specific descriptor set used. The AD is inseparable from the model's algorithm and descriptors (OECD Principle 2 and 3) [31].

Problem: How to optimally set the threshold for a leverage-based AD?

- Cause: There is no universally optimal threshold, but established heuristics exist based on the training set's properties [30].

- Solution:

- Calculate the Warning Leverage: The most common threshold is the warning leverage, h, calculated as 3p/n, where 'p' is the number of model parameters (descriptors + 1) and 'n' is the number of training compounds.

- Visualize and Refine: Plot the leverage of training compounds against their standardized residuals. This Williams plot can help identify outliers and verify the reasonableness of the chosen threshold. Query compounds with a leverage greater than h should be considered outside the AD [30].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Defining an Applicability Domain using the Bounding Box Method

- Objective: To establish a simple, range-based AD for a QSAR model.

- Materials: A validated QSAR model and its training set of

ncompounds, each characterized bypmolecular descriptors. - Methodology:

- For each of the

pdescriptors used in the model, calculate its maximum and minimum value across the entire training set. - The AD is defined as the p-dimensional hyper-rectangle enclosed by these min-max values.

- For a new query compound, calculate its

pdescriptors. - Evaluation: If the value of every descriptor for the query compound falls within the corresponding min-max range of the training set, the compound is inside the AD. If any descriptor value falls outside this range, the compound is outside the AD [30] [1].

- For each of the

- Technical Notes: This method is fast but should be used with caution as it often overestimates the true AD.

Protocol 2: Defining an Applicability Domain using the Leverage Method

- Objective: To establish a multivariate distance-based AD that accounts for the data distribution.

- Materials: A validated QSAR model, its training set data matrix

X(n x p), and the model matrix (e.g.,Xwith a column of 1s for the intercept). - Methodology:

- Calculate the hat matrix: ( H = X(X^T X)^{-1} X^T ) [30].

- The leverage of each training compound is the corresponding diagonal element of the

Hmatrix. - Calculate the average leverage for the training set: ( \bar{h} = p/n ), where

pis the number of model descriptors andnis the number of training compounds. - Set the warning leverage (threshold): ( h^* = 3 \times \bar{h} ) [30].

- For a query compound with descriptor vector

x, calculate its leverage: ( h = x^T (X^T X)^{-1} x ). - Evaluation: If the query compound's leverage ( h ) is less than or equal to the warning leverage ( h^* ), it is inside the AD. If ( h > h^* ), it is outside the AD and its prediction is unreliable.

Protocol 3: Systematic Evaluation and Optimization of AD Methods

- Objective: To select the optimal AD method and its hyperparameters for a specific QSAR model and dataset [32].

- Materials: A dataset with known outcomes, a defined machine learning model

y = f(x). - Methodology:

- Perform Double Cross-Validation (DCV) on the entire dataset to obtain predicted

yvalues for all samples [32]. - For each candidate AD method (e.g., Bounding Box, kNN, Leverage) and its hyperparameters (e.g., k in kNN, threshold in leverage):

- Calculate the AD index (e.g., leverage value, distance) for each sample.

- Sort all samples from most to least "reliable" according to the AD index.

- Calculate the coverage (fraction of data included) and the corresponding Root-Mean-Squared Error (RMSE) as more samples are progressively included.

- Calculate the Area Under the Coverage-RMSE Curve (AUCR) [32].

- Evaluation: The optimal AD method and hyperparameter combination is the one that yields the lowest AUCR value, as it provides the best trade-off between high coverage and low prediction error [32].

- Perform Double Cross-Validation (DCV) on the entire dataset to obtain predicted

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Tool Name | Function in AD Assessment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Quantitative representations of chemical structure; form the basis of the chemical space for all AD methods [30]. | Can be topological, geometrical, or electronic. Must be relevant to the modeled endpoint. |

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | A dimensionality reduction technique; used to create a PCA Bounding Box that accounts for descriptor correlations [30]. | Transforms original descriptors into orthogonal PCs. Helps mitigate multicollinearity. |

| Hat Matrix (H) | The core mathematical object for calculating leverage values in regression-based QSAR models [30]. | ( H = X(X^T X)^{-1} X^T ). Its diagonal elements are the leverages. |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | A distance-based method used as an alternative or supplement to geometric methods. Measures local data density [32]. | Hyperparameter k must be chosen (e.g., 5). Robust to the shape of the data distribution. |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) | An advanced density-based method for AD that can identify local outliers missed by global methods [32]. | Compares the local density of a point to the local densities of its neighbors. |

Workflow Diagram for AD Method Selection

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for selecting and applying range-based and geometric AD methods.

Decision Workflow for Range-Based and Geometric AD Methods

Comparative Analysis of AD Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the discussed AD methods to aid in selection.

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bounding Box | Range-based | Checks if descriptors are within min-max range of training set [30]. | Simple, fast, easy to interpret [30]. | Cannot detect correlated descriptors or empty regions inside the box; often overestimates AD [30]. |

| PCA Bounding Box | Range-based/Geometric | Projects data onto PCs, then applies a bounding box in PC space [30]. | Accounts for correlations between descriptors [30]. | Still cannot identify internal empty regions; choice of number of PCs adds complexity [30]. |

| Convex Hull | Geometric | Defines the smallest convex polytope containing all training points [30] [1]. | Precisely defines the outer boundaries of the training set. | Computationally infeasible for high-dimensional data (curse of dimensionality) [30] [1]. |

| Leverage | Distance-based (Geometric) | Measures the Mahalanobis distance of a compound to the centroid of the training data [30]. | Accounts for data distribution and correlation structure; well-suited for regression models [30]. | Limited to the descriptor space of the model; requires matrix inversion, which can be unstable. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core relationship between the distance to my training set and my model's prediction error? Prediction error, such as the Mean-Squared Error (MSE) when predicting bioactivity (e.g., log IC50), robustly increases as the distance to the nearest training set compound increases [15]. This is a fundamental expression of the molecular similarity principle. The following table summarizes this relationship for a QSAR model predicting log IC50 [15]:

| Mean-Squared Error (MSE) on log IC50 | Typical Error on IC50 | Sufficiency for Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | ~3x | Accurate enough to support hit discovery and lead optimization [15] |

| 1.0 | ~10x | Sufficient to distinguish a potent lead from an inactive compound [15] |

| 2.0 | ~26x | Can still distinguish between potent and inactive compounds [15] |

Q2: I'm getting high errors even on compounds that are somewhat similar to my training set. What's wrong? High error for "somewhat similar" compounds often indicates you are hitting an activity cliff, where small structural changes cause large activity changes [33]. This is particularly common in Natural Product chemistry. Your choice of molecular fingerprint may also be to blame; different fingerprints can provide fundamentally different views of chemical space [33]. Benchmark multiple fingerprint types on your specific dataset to identify the best performer.

Q3: Should I use a distance-based approach or a classifier's confidence score to define the Applicability Domain (AD)? For classification models, confidence estimation (using the classifier's built-in confidence) generally outperforms novelty detection (using only descriptor-based distance) [26]. Benchmark studies show that class probability estimates from the classifier itself are consistently the best measures for differentiating reliable from unreliable predictions [26]. Use distance-based methods like Tanimoto when you need an AD independent of a specific classifier model.

Q4: How do I choose the right molecular fingerprint for my distance calculation? The optimal fingerprint depends on your chemical space and endpoint. Below is a performance summary from a benchmark study on over 100,000 natural products, but the insights are broadly applicable [33]. Performance was measured using the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) for bioactivity prediction tasks; higher AUC is better.

| Fingerprint Category | Example Algorithms | Key Characteristics | Relative Performance for Bioactivity Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular | ECFP, FCFP | Encodes circular atom neighborhoods around each atom; the de-facto standard for drug-like compounds [15] [33] | Can be matched or outperformed by other fingerprints for specialized chemical spaces like Natural Products [33] |

| Path-Based | Atom Pair (AP), Depth First Search (DFS) | Encodes linear paths or atom pairs within the molecular graph [33] | Can outperform ECFP on some NP datasets [33] |

| String-Based | MHFP, MAP4 | Operates on the SMILES string; can be less sensitive to small structural changes [33] | Can outperform ECFP on some NP datasets [33] |

| Substructure-Based | MACCS, PUBCHEM | Each bit encodes the presence of a predefined structural moiety [33] | Performance varies [33] |

| Pharmacophore-Based | PH2, PH3 | Encodes potential interaction points (e.g., H-bond donors) rather than pure structure [33] | Performance varies [33] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Tanimoto Distance Results

- Symptoms: The same pair of molecules returns different similarity scores when using different software or fingerprint parameters.

- Solution: Ensure consistency in your computational protocol.

- Standardize Molecules: Always standardize chemical structures (e.g., remove salts, neutralize charges, handle tautomers) before fingerprint calculation [33].

- Document Parameters: When using a fingerprint like ECFP, note the key parameters: radius (often 2 for ECFP4) and bit length (e.g., 1024, 2048) [15].

- Use the Same Tool: Calculate fingerprints and distances for an entire project using the same cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel) to ensure internal consistency [9].

Problem: High Mahalanobis Distance for Seemingly Ordinary Compounds

- Symptoms: A compound with descriptor values that appear to be within the range of the training set is flagged as an outlier by the Mahalanobis distance.

- Solution: This typically indicates the compound lies in a region of chemical space that is sparsely populated in your training set, even if individual descriptors seem normal.

- Visualize: Use PCA (Principal Component Analysis) to project your training and test sets into 2D or 3D space. The flagged compound will likely be in a low-density region of the training set cloud.

- Check Feature Correlation: Mahalanobis distance accounts for correlation between descriptors. Check if your compound has an unusual combination of descriptor values, even if each one is normal in isolation.

- Consider a Consensus: Do not rely on a single AD method. Combine the Mahalanobis distance with other measures, such as the distance to the k-nearest neighbors, to get a more robust assessment [12] [26].

Problem: My Model Fails to Generalize to New Scaffolds

- Symptoms: The model is accurate for compounds similar to the training set but fails dramatically for new chemotypes or core scaffolds.

- Solution: This is a core limitation of interpolation-based QSAR models. The following workflow outlines a strategic approach to diagnose and address this issue.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Category | Item | Function in Distance-Based AD |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Packages | RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics; calculates fingerprints (ECFP, etc.), descriptors, and distances [33] [34] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor, Mordred | Software to calculate thousands of molecular descriptors from structures [9] | |

| Scikit-learn | Python ML library; contains functions for Euclidean and Mahalanobis distance calculations, plus many clustering and validation tools [26] | |

| Key Metrics & Algorithms | Tanimoto / Jaccard Similarity | The most common metric for calculating similarity between binary fingerprints like ECFP [15] [33] |

| Euclidean Distance | Measures straight-line distance in a multi-dimensional descriptor space. Sensitive to scale, so descriptor standardization is critical [35] | |

| Mahalanobis Distance | Measures distance from a distribution, accounting for correlations between descriptors. Useful for defining multi-parameter AD [36] [12] | |

| Applicability Domain Indexes (e.g., RI, MODI) | Simple, model-independent indexes (e.g., Rivality Index) that can predict a molecule's predictability without building the full QSAR model [12] | |

| Experimental Protocols | Benchmarking Fingerprints | Protocol: Systematically calculate multiple fingerprint types (e.g., ECFP, Atom Pair, MHFP) for your dataset. Evaluate their performance on a relevant task (e.g., bioactivity prediction) to select the best one for your chemical space [33] |

| Defining a Distance Threshold | Protocol: Plot model error (e.g., MSE) against Tanimoto distance to the training set. Set the AD threshold at the distance where error exceeds a level acceptable for your project (e.g., corresponding to a 10x error in IC50) [15] | |

| Consensus AD | Protocol: Instead of a single method, define a molecule as inside the AD only if it passes multiple criteria (e.g., within a Tanimoto threshold AND has a low Mahalanobis distance AND is predicted with high confidence by the classifier) [12] [26] [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using KDE over simpler methods for defining the Applicability Domain (AD) in QSAR models?

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) provides a fundamental non-parametric method to estimate the probability density function of your data, uncovering its hidden distributions without assuming a specific form [37]. For QSAR models, this translates to several key advantages over simpler geometric or distance-based methods (like convex hulls or nearest-neighbor distances) [13]. KDE naturally accounts for data sparsity and can trivially handle arbitrarily complex geometries and multiple disjointed regions in feature space that should be considered in-domain. Unlike a convex hull, which might designate large, empty regions as in-domain, KDE identifies domains based on regions of high data density, offering a more nuanced and reliable measure of similarity to the training set [13].

FAQ 2: How does the choice of bandwidth parameter 'h' impact my KDE-based Applicability Domain, and how can I select an appropriate value?

The bandwidth parameter (h) is a free parameter that has a strong influence on the resulting density estimate and, consequently, your AD [38]. It controls the smoothness of the estimated density function:

- An undersmoothed estimate (

htoo small) contains too many spurious data artifacts and is too sensitive to the noise in the training data. The resulting AD will be overly conservative and fragmented. - An oversmoothed estimate (

htoo large) obscures much of the underlying structure of the data. The resulting AD will be too permissive, potentially including regions where the model is not reliable [38].