Beyond Rigid Locks: Solving Protein Flexibility to Revolutionize Molecular Docking in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of protein flexibility in molecular docking and the advanced computational strategies developed to address it.

Beyond Rigid Locks: Solving Protein Flexibility to Revolutionize Molecular Docking in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of protein flexibility in molecular docking and the advanced computational strategies developed to address it. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of protein dynamics, from induced-fit mechanisms to allosteric regulation. The scope covers a wide array of methodological approaches, including ensemble docking from Molecular Dynamics simulations, machine learning-driven models like Re-Dock and FABFlex, and flexible side-chain refinement. We evaluate the performance, accuracy, and practical application of these techniques through comparative benchmarks and validation studies, offering troubleshooting insights for optimizing docking protocols. Finally, the article synthesizes key takeaways on how overcoming the flexibility hurdle is transforming structure-based drug design, enabling the targeting of challenging proteins and accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics.

The Protein Flexibility Problem: Why Rigid Docking Fails in Real-World Drug Design

Molecular docking, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, aims to predict how a small molecule (ligand) interacts with a biological target at the atomic level [1]. Despite decades of advancement, a central challenge persists: protein flexibility. Traditional rigid docking, which treats both partners as static structures, often fails because biomolecules are inherently dynamic [2] [1]. This technical support document, framed within a thesis on solving protein flexibility, guides researchers through the evolving theories of biomolecular recognition and their practical implications for troubleshooting docking experiments. Understanding the shift from the rigid "lock-and-key" hypothesis to modern dynamic models like "conformational selection" is crucial for interpreting results and selecting the right methodological approach [3] [4].

Theoretical Framework: Evolving Models of Biomolecular Recognition

The following section details the progression of models that describe how proteins and ligands recognize and bind to each other.

The Lock-and-Key Model

- Core Principle: Proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, this model posits that the ligand (key) possesses a fixed, complementary geometry to the protein's binding site (lock) [4]. Binding is a simple, rigid-body association.

- Relevance to Docking: This is the foundational assumption of rigid docking protocols. While computationally efficient, its oversimplification is a major source of inaccuracy in many real-world applications where binding sites are not pre-formed [1].

The Induced Fit Model

- Core Principle: Introduced by Koshland in 1958, this model states that the binding partner induces a conformational change in the protein's structure upon binding [3] [5]. The final complementary shape is achieved only after the initial interaction.

- Implications for Docking: This model necessitates flexible docking methods that can simulate the structural adjustments of the protein upon ligand binding. It is often more accurate but is computationally demanding [2].

The Conformational Selection Model

- Core Principle: This modern paradigm, rooted in the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model of allostery, proposes that the unliganded protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple conformations [3] [5]. The ligand does not induce a new shape but rather selects and stabilizes a pre-existing complementary conformation from this ensemble, shifting the population toward the bound state [3] [4].

- Implications for Docking: This model demands a paradigm shift from docking to a single protein structure to docking against conformational ensembles [4]. It explains how binding at one site (allosteric) can affect the activity at another distant site through population shifts [3].

The Extended Conformational Selection Model

Current understanding suggests that pure induced fit or conformational selection are rare. Instead, an extended model is widely applicable, where binding involves a repertoire of both selection and subsequent adjustment steps [3]. This is often described as an "interdependent protein dance," where the partners undergo a series of mutual conditional steps before achieving the final bound complex [3].

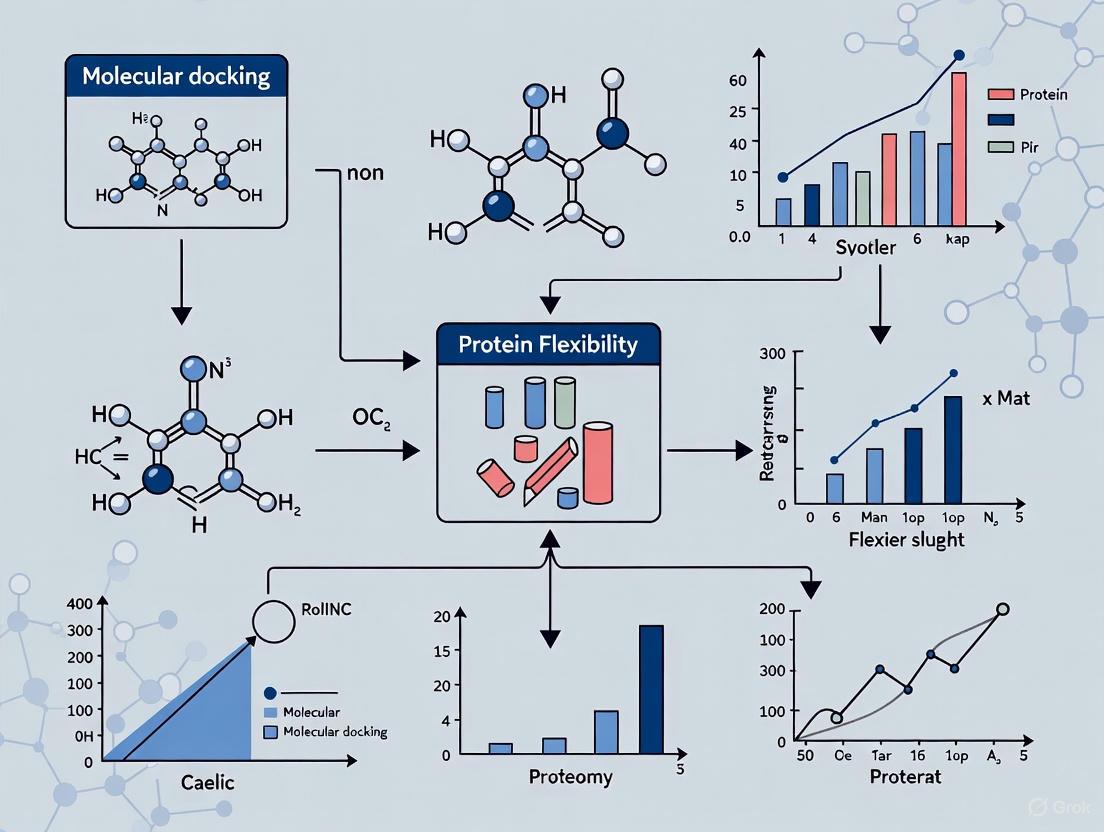

The diagram below illustrates the logical progression from a single, rigid conformation to an ensemble-based view of binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, methods, and their functions central to studying biomolecular recognition and tackling protein flexibility.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Methods for Studying Biomolecular Recognition

| Item/Method | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Probes the role of specific residues in binding and conformational change. | Essential for validating computational predictions of key interaction points. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Provides atomic-resolution data on protein dynamics and transient populations in solution [4]. | Critical for experimentally characterizing conformational ensembles. |

| Stopped-Flow Fluorimetry | Measures rapid binding kinetics (e.g., k_obs) to distinguish between binding mechanisms [5]. | A hyperbolic increase in k_obs with [L] is often, but not exclusively, assigned to induced fit [5]. |

| X-ray Crystallography | Provides high-resolution, static snapshots of protein-ligand complexes. | May trap a single conformation, missing the full dynamic ensemble. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computationally simulates the physical movements of atoms over time, revealing pathways and dynamics [4] [6]. | Used to generate conformational ensembles and study binding pathways. |

| Conformational Ensemble | A collection of protein structures representing its dynamic state; used for ensemble docking [4]. | Can be generated by MD simulations, NMR data, or multiple crystal structures. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges related to protein flexibility and molecular docking.

FAQ 1: My docking simulations successfully predict the binding pose, but the calculated binding affinity does not correlate with my experimental activity data. Why?

- Potential Cause: Inaccurate scoring functions. The mathematical functions used to predict binding affinity often struggle to represent the true thermodynamics of the interaction, which includes complex effects like entropy, solvation/desolvation, and conformational changes [1].

- Solution:

- Use Consensus Scoring: Employ multiple scoring functions and look for consensus rather than relying on a single method [1].

- Incorporate Solvent Effects: Ensure your docking protocol explicitly accounts for water molecules, especially those that are structurally conserved and mediate interactions [1] [6].

- Consider Entropic Penalties: Be aware that ligands with many rotatable bonds incur a higher entropy cost upon binding, which is often poorly estimated by scoring functions [1].

FAQ 2: How can I determine if my system follows an induced fit or a conformational selection mechanism?

- The Challenge: The two mechanisms are often difficult to distinguish with equilibrium measurements alone. Kinetics are often more informative [5].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Measure Binding Kinetics: Use a method like stopped-flow fluorescence to measure the observed rate constant (kobs) of binding over a wide range of ligand concentrations [L] [5].

- Analyze the kobs vs. [L] Plot:

- If kobs decreases with increasing [L], it is strong, but not absolute, evidence for conformational selection (Scheme 2) [5].

- If kobs increases with increasing [L], it is compatible with an induced fit mechanism (Scheme 3) but can also be explained by conformational selection under certain conditions. Further analysis is required [5].

- Probe the Unliganded State: Use NMR spectroscopy to determine if the unliganded protein samples conformations that resemble the bound state. The presence of such low-populated states is a hallmark of conformational selection [3] [4].

The workflow below outlines the key decision points in this diagnostic process.

FAQ 3: How can I account for full protein flexibility in my virtual screening campaigns?

- The Problem: Docking with full, on-the-fly protein flexibility is computationally prohibitive for screening large compound libraries [2].

- Recommended Solutions:

- Ensemble Docking: This is the most practical and widely used approach. Dock your ligand library against an ensemble of multiple protein conformations (e.g., from MD simulations, NMR models, or multiple crystal structures) [2]. This implicitly accounts for large-scale conformational changes.

- Use Soft Potentials: Some docking programs allow the use of "soft" van der Waals potentials, which reduce the penalty for minor atomic clashes, effectively allowing for small side-chain movements without explicitly sampling them.

- Focus on Critical Flexibility: If known, allow only key side chains in the binding site to be flexible during docking, while keeping the protein backbone rigid. This balances accuracy and computational cost.

FAQ 4: How do I handle protonation states and tautomerism of ligands in docking?

- The Challenge: The appropriate protonation state or tautomeric form of a ligand can be different in solution and in the protein-bound state. Docking with an incorrect form leads to failed predictions [1].

- Solution:

- Pre-generate States: Prior to docking, generate all possible reasonable protonation states and tautomers at physiological pH using tools like LigPrep (Schrödinger) or MOE (Chemical Computing Group).

- Dock All Forms: Dock each generated state separately and analyze the results. The form that achieves the best complementary fit and score is often the correct one for the binding site environment.

- Use pKa Prediction Tools: Employ software to predict ligand pKa values to guide which protonation states are most likely.

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating a Conformational Ensemble via Molecular Dynamics (MD)

Purpose: To create a set of diverse protein structures for ensemble docking that captures intrinsic flexibility [4] [6].

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain a starting protein structure (e.g., from the PDB).

- Use a program like

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(AMBER) to add missing hydrogens, place the protein in a solvation box (e.g., TIP3P water), and add counterions to neutralize the system.

- Energy Minimization:

- Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove bad steric clashes and relax the system.

- Equilibration:

- Perform a short (100-200 ps) simulation under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) conditions to stabilize the temperature.

- Follow with a simulation under NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) conditions to stabilize the density of the system.

- Production MD:

- Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a time scale relevant to your protein's dynamics (typically tens to hundreds of nanoseconds). The required length depends on the slowest conformational change of interest.

- Trajectory Analysis and Clustering:

- Analyze the resulting trajectory to remove translational and rotational motion.

- Use a clustering algorithm (e.g., GROMACS

cluster) based on the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone to group similar conformations. - Select representative structures (e.g., the central structure of the most populous clusters) to form your final conformational ensemble for docking.

Protocol: Distinguishing Binding Mechanisms via Stopped-Flow Kinetics

Purpose: To experimentally determine whether a ligand binding event follows induced fit or conformational selection kinetics [5].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified protein and ligand in an appropriate assay buffer.

- Data Collection:

- Using a stopped-flow instrument, rapidly mix the protein and ligand solutions at a 1:1 ratio across a series of final ligand concentrations ([L]).

- Monitor a signal that changes upon binding (e.g., intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), or a fluorescent probe's signal).

- For each concentration, collect multiple kinetic traces and average them.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit each individual kinetic trace to a single-exponential equation to extract the observed rate constant (kobs).

- Plot kobs as a function of the final ligand concentration [L].

- Interpretation:

FAQ: Understanding the Cross-Docking Problem

What is cross-docking and why does it often fail? Cross-docking refers to the attempt to dock a ligand into a protein structure that was solved in the presence of a different ligand or in its unbound (apo) state [7]. This often fails because the protein's active site can be biased toward the native ligand present during experimental structure determination. Movements in the backbone, side chains, and active site metals can create a binding site geometry that is incompatible with the new ligand, leading to misdocking that cannot be overcome without accounting for these conformational shifts [7].

What is the performance difference between rigid and flexible docking? Typical rigid protein-ligand docking, which uses a single static receptor structure, shows the best performance rates between 50 and 75% [7]. In contrast, docking methods that incorporate full protein flexibility can significantly enhance pose prediction success rates to 80–95% [7].

What are conformational selection and induced fit? These are two primary models explaining ligand binding:

- Conformational Selection: The protein naturally exists as an ensemble of conformations. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing complementary conformation, shifting the population distribution [7] [8].

- Induced Fit: The binding of the ligand induces a conformational change in the protein to optimize their fit [7] [8]. These models are not mutually exclusive; a mixed binding mechanism is likely for many proteins. For docking, the key takeaway is that some mechanism of receptor conformational change must be incorporated for accurate predictions [7].

How do I know if my target protein is too flexible for rigid docking? Low accuracy in predicted structures for regions that depend on interactions with other domains or ligands can be a red flag [9]. Additionally, long stretches of amino acids predicted to be coils or with low confidence scores from tools like AlphaFold may indicate intrinsically disordered regions that fall outside the scope of conventional rigid docking [9]. Consensus prediction methods that merge multiple disorder prediction algorithms can also help identify such flexible regions [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Cross-Docking Failures and Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Root Cause | Solution & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Failed pose prediction during virtual screening for a known ligand. | The single protein conformation used creates a steric clash or incorrect geometry for the new ligand [7]. | Use an ensemble docking approach. Dock into multiple relevant protein structures (e.g., apo and holo forms) and combine the results [11]. |

| Inaccurate binding affinity prediction despite correct binding pose. | Standard scoring functions are negatively impacted by protein flexibility and solvation effects, failing to accurately describe the interaction [7]. | Post-process docking results with more sophisticated molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to refine the pose and calculate binding free energies [8]. |

| A potent inhibitor is missed entirely in a screen. | The protein conformation required to accommodate the inhibitor is not represented in the rigid receptor model [11]. | Implement a tool like FlexE, which explicitly considers side-chain and loop flexibility by combining parts from an ensemble of structures during the docking process [11]. |

| Poor results with a homology model. | Ambiguities in side-chain placement and loop modeling create an inaccurate or biased binding site [11]. | Generate multiple homology models or use rotamer libraries to create a united protein description for docking, allowing the algorithm to select optimal conformations [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Ensemble Docking Strategy

Objective: To improve docking reliability for a flexible protein target by using an ensemble of structures.

Materials Needed:

- Protein Structure Ensemble: A set of experimentally determined structures (from the PDB) for the target protein. Ideal ensembles have highly similar backbone traces but different side-chain conformations or loop movements [11].

- Ligand Database: The set of small molecules to be docked.

- Computational Tools:

Methodology:

Ensemble Curation:

- Collect multiple crystal or NMR structures of your target from the PDB. Prioritize structures solved with different ligands or in the apo state.

- Superimpose all structures based on their backbone atoms to ensure a common frame of reference.

Docking Execution:

- Approach 1 - Cross-Docking and Merging: Dock each ligand from your database into every individual structure in your ensemble. Merge the results from all runs into a single ranked list based on the docking score [11].

- Approach 2 - Integrated Ensemble Docking (e.g., with FlexE): Use a tool like FlexE, which creates a "united protein description" from the superimposed ensemble. The algorithm then selects the optimal combination of partial structures for each ligand during the docking process itself [11].

Validation:

- If the experimental binding mode of a ligand is known (from a crystal structure), use the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the heavy atoms between the predicted and known pose to assess accuracy. A solution with an RMSD below 2.0 Å is generally considered successful [11].

- Compare the success rates and the quality of the top-ranked poses from the ensemble method against the results from docking into a single, rigid structure.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Material | Function in Flexible Docking |

|---|---|

| FlexE | A docking tool that explicitly handles protein structure variations by combining parts from an ensemble of input structures during ligand placement [11]. |

| AlphaFold/ColabFold | Provides highly accurate predicted protein structures for targets without experimental data; low confidence scores (pLDDT) can signal flexible/disordered regions [12] [9]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Used to generate an ensemble of protein conformations for docking or to refine and re-score docked poses by simulating the dynamic binding process [8]. |

| Conformational Disorder Predictors (e.g., DISEMBL, IUPRED) | Bioinformatic tools that identify intrinsically disordered or flexible regions from the amino acid sequence, helping to define construct boundaries for experimental work [10]. |

| Rotamer Libraries | Collections of statistically favored side-chain conformations; can be used to computationally generate alternative protein models for docking [11]. |

Performance Comparison: Rigid vs. Flexible Docking

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from validation studies, highlighting the advantage of flexible methods.

| Docking Method | Key Feature | Test Context | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Receptor Docking (e.g., standard FlexX) | Single, fixed protein conformation. | Cross-docking of 60 ligands into 105 protein structures [11]. | Found a pose with RMSD < 2.0 Å in 63% of cases (top 10 solutions) [11]. |

| Ensemble Docking (FlexE) | Combines multiple protein structures during docking. | Docking the same 60 ligands into a united protein description of the ensemble [11]. | Found a pose with RMSD < 2.0 Å in 67% of cases (top 10 solutions) [11]. |

| Fully Flexible Docking (Various methods) | Incorporates full protein flexibility. | General review of flexible docking methodologies [7]. | Can enhance pose prediction success up to 80–95% [7]. |

Workflow Diagram: Ensemble Docking Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting an ensemble docking study to overcome the cross-docking challenge.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Protein Flexibility in Docking

FAQ 1: Why does my docking simulation fail to reproduce the known binding pose from a crystal structure?

The Problem: This is a classic "cross-docking" problem where the active site conformation is biased toward the specific ligand it was crystallized with [7]. When you attempt to dock a different ligand into this rigid structure, critical steric clashes or missing interactions prevent correct pose prediction.

Solutions:

- Use Multiple Receptor Conformations: Instead of a single rigid structure, employ an ensemble of protein conformations. These can be obtained from:

- Implement Flexible Side-Chains: Allow specific side-chains in the binding pocket to sample alternative rotamers during the docking procedure. Residues with long side chains (3+ dihedral angles) like Arg, Lys, and Gln are particularly important to flex [15].

- Verify Conformational Selection: Ensure your chosen receptor structure represents a biologically relevant state. A conformation from a crystal structure with a similar ligand type may yield better results.

FAQ 2: How can I identify if side-chain flexibility is critical for my target protein?

The Problem: Incorporating full side-chain flexibility is computationally expensive. You need to identify which residues are likely to undergo conformational changes upon binding to focus your computational resources effectively.

Solutions:

- Analyze Structural Databases: Use resources like PDBFlex to quantify the natural conformational variability of each residue in your protein across multiple experimental structures [13].

- Identify High-Variability Residues: Residues with higher B-factors, alternate locations in PDB files, or those shown to vary between structures are prime candidates for flexibility [16].

- Check Side-Chain Length and Type: Longer, polar side-chains (e.g., Arg, Lys, Glu) have higher propensity for large conformational changes (>120° in χ angles) compared to shorter or non-polar residues [15].

- Calculate Solvent Exposure: Surface-exposed side-chains at binding interfaces show greater conformational variability than buried cores [15] [16].

FAQ 3: My docking results show good pose prediction but poor correlation with experimental binding affinities. What flexibility-related factors might be causing this?

The Problem: Accurate pose prediction (geometry) does not guarantee accurate binding affinity (scoring). This scoring failure often peaks at intermediate RMSD values (1.5-2.0 Å), suggesting subtle conformational adjustments critically impact energy calculations [7].

Solutions:

- Incorporate Backbone Flexibility: For affinity prediction, even small backbone movements (often ignored in docking) can be crucial. Consider using methods that allow limited backbone flexibility or ensemble-based docking.

- Account for Allosteric Effects: Your ligand might be binding to an allosteric site, causing conformational changes distant from the active site that affect function [14]. Use methods like molecular dynamics to detect allosteric networks.

- Include Solvation Effects: Protein flexibility upon binding often reorganizes water networks. Use scoring functions that explicitly account for solvation/desolvation effects, which are coupled to protein flexibility [7].

- Validate with MM-GBSA: Perform more rigorous binding free energy calculations using molecular mechanics with generalized Born and surface area solvation (MM-GBSA) on docked poses, which can better handle flexibility [14].

FAQ 4: How can I detect and characterize allosteric binding sites computationally?

The Problem: Allosteric sites are often hidden in crystal structures and only become apparent when considering protein dynamics and conformational ensembles.

Solutions:

- Use Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Run MD simulations of the apo protein to identify transient pockets and communication networks between distant sites [14].

- Implement Allosteric Prediction Methods: Apply specialized methods like MBAP (Molecular Dynamics-Based Allosteric Prediction) that combine MD with MM-GBSA energy decomposition to identify residues involved in allosteric signal transmission [14].

- Analyze Correlated Motions: Use statistical analyses of MD trajectories (e.g., principal component analysis) to identify residues that move cooperatively, suggesting allosteric pathways.

- Leverage Evolutionary Information: Some methods use sequence co-evolution patterns to predict allosteric sites, though these work best with large protein families.

Quantitative Data on Protein Flexibility

Table 1: Side-Chain Conformational Variability by Residue Type

| Residue Type | Number of χ Angles | Average Dihedral Angle RSD | Average RMSD (Å) | Propensity for Large Transitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (Ser, Val) | 1-2 | 40-55° | 0.75-1.22 Å | Low - Local adjustments only |

| Long (Lys, Arg) | 3-4 | 111-135° | 1.94-2.54 Å | High - Full rotamer transitions |

| Aromatic (Phe, Tyr) | 2 | ~55° | ~1.22 Å | Medium - Restricted motion |

| Polar (Asn, Gln) | 2-3 | 55-111° | 1.22-1.94 Å | Medium-High |

| Cys, Pro | 1-2 | <40° | <0.75 Å | Very Low - Restricted |

Data derived from systematic analysis of bound-unbound structures in DOCKGROUND benchmark set [15]

Table 2: Performance Impact of Incorporating Protein Flexibility in Docking

| Docking Method | Rigid Receptor Performance | Flexible Receptor Performance | Key Limitations Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Rigid Docking | 50-75% success rate | - | Sampling failure, cross-docking bias |

| Flexible Side-Chain Docking | - | Improves to ~80% success | Side-chain induced fit |

| Full Flexible Docking | - | 80-95% success rate | Backbone adjustments, allosteric effects |

| Ensemble Docking | - | 75-90% success rate | Multiple accessible states, conformational selection |

Performance rates for pose prediction based on comparative studies of docking programs [7]

Experimental Protocols for Flexibility Analysis

Protocol 1: Molecular Dynamics-Based Allosteric Prediction (MBAP)

Based on the MBAP method validated for threonine dehydrogenase [14]

Objective: Identify indirect-binding sites and potential mutations to modulate allosteric regulation.

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure (PDB ID if available)

- Use molecular docking to position allosteric effector if complex structure unavailable

- Solvate system in TIP3P water box with 12 Å padding

- Neutralize with counterions

MD Simulation:

- Run 100+ ns simulation in NPT ensemble (310K, 1 atm)

- Use Langevin dynamics with 5.0 ps⁻¹ damping coefficient

- Apply periodic boundary conditions

- Track RMSD of backbone residues to verify stability

Energy Decomposition:

- Use MM-GBSA method to calculate binding free energy

- Decompose energy contributions per residue

- Identify residues contributing >0.1 kcal/mol to binding

Saturation Mutagenesis Prediction:

- Perform in silico saturation mutagenesis on candidate residues

- Run 1 ns MD simulation for each mutant

- Compare binding energies to wild-type

- Select mutations with significant energy changes for experimental testing

Expected Outcomes: Identification of previously unknown allosteric residues and mutations that modulate allosteric regulation, validated by in vitro assays.

Protocol 2: Side-Chain Conformational Variability Quantification

Based on large-scale analysis of PDB structures [16]

Objective: Quantify natural conformational variability of side-chains to inform docking protocols.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation:

- Collect non-redundant set of protein chains (<25% sequence identity)

- Apply resolution cutoff (e.g., <3.5 Å)

- Exclude nucleic acid-bound complexes

Reliability Assessment:

- Calculate point electron density for all atoms

- Mark atoms with electron density >1σ in 2|Fo|-|Fc| map as reliable

- Classify side-chains with any unreliable atoms as flexible

Alternate Location Analysis:

- Extract residues with multiple conformations in PDB

- Calculate occupancy-weighted average positions

- Measure dihedral angle differences between alternate states

Cross-Structure Comparison:

- Superpose multiple structures of same protein

- Align by backbone atoms

- Calculate side-chain RMSD and dihedral angle changes

- Correlate variability with solvent exposure, residue type, and local environment

Expected Outcomes: Quantitative profile of side-chain flexibility for each residue type, informing which residues to treat as flexible in docking studies.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Diagram Title: Conformational Selection vs Induced Fit in Protein-Ligand Binding

Diagram Title: Computational Workflow for Allosteric Site Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Protein Flexibility Research

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function | Access/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBFlex Database | Database | Analyzes structural variations of identical proteins across PDB | http://pdbflex.org [13] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software | Simulates protein dynamics and conformational changes | GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, CHARMM [17] [14] |

| MM-GBSA Methods | Computational Method | Decomposes binding free energy into residue contributions | AMBER, SCHRÖDINGER [14] |

| ATLAS Database | MD Database | Pre-computed simulations of ~2000 representative proteins | https://www.dsimb.inserm.fr/ATLAS [17] |

| GPCRmd | Specialized Database | MD simulations focused on GPCR family dynamics | https://www.gpcrmd.org/ [17] |

| BioLiP | Database | Identifies biologically relevant ligands for proteins | Integrated with PDBFlex [13] |

| DOCKGROUND Benchmark Sets | Dataset | Curated bound-unbound structures for docking validation | Used for side-chain variability studies [15] |

| Alternate Location PDB Entries | Experimental Data | Provides direct evidence of side-chain conformational heterogeneity | Filter PDB for multi-conformation residues [16] |

Advanced Technical Considerations

When implementing flexibility in docking protocols, consider these critical technical aspects:

Thresholds for Significant Movement:

- Coordinate differences <0.6-0.8 Å may fall within experimental uncertainty [18]

- Backbone Cα RMSD >2.0 Å between bound and unbound structures indicates significant flexibility [15]

- Dihedral angle changes >120° typically represent transitions between rotameric states [15]

Side-Chain Classification by Flexibility:

- Fixed Conformations: Buried residues with definite coordinates

- Discrete Conformations: Multiple well-defined states with clear electron density

- Cloud Conformations: Continuous conformational regions

- Flexible Conformations: Poorly defined in electron density maps [16]

Computational Cost Management:

- Focus flexibility on interface residues showing high variability in PDBFlex analysis [13]

- Prioritize long, polar side-chains over short, non-polar ones [15]

- Use implicit solvent models for initial screening, explicit solvent for refinement

- Consider hierarchical approaches: rigid docking first, then flexible refinement of top hits

By systematically addressing protein flexibility using these troubleshooting approaches, databases, and protocols, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy of molecular docking outcomes for drug discovery applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Protein Flexibility in Drug Discovery

FAQ 1: How does protein flexibility contribute to drug resistance? Drug resistance can arise from mutations that alter a protein's flexibility and dynamics, not just its static structure. For instance, a point mutation (N368S) in Abl kinase, the target of the anti-cancer drug Imatinib (Gleevec), does not significantly change the drug's binding affinity but drastically reduces its residence time. All-atom molecular dynamics simulations revealed that this mutation triggers long-range changes in the protein's flexibility, opening a new, faster dissociation pathway for the drug that is not available in the wild-type protein [19]. This demonstrates how mutations can exploit protein dynamics to confer resistance.

FAQ 2: Why are allosteric modulators often more selective than orthosteric drugs? Allosteric modulators achieve high selectivity by binding to sites that are less evolutionarily conserved than the active (orthosteric) site [20] [21]. A key mechanism involves exploiting differential protein flexibility and "cryptic pockets." These are binding sites that are not visible in static crystal structures but open dynamically in specific protein subtypes. For example, a highly selective positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of the M1 muscarinic receptor binds a cryptic pocket that forms far more frequently in M1 than in the closely related M2, M3, and M4 receptors, despite their nearly identical static structures [22].

FAQ 3: How can protein flexibility lead to entropically driven drug binding? Some high-affinity drugs with long residence times bind in a way that increases the flexibility of the target protein in its ligand-bound state. In a study on HSP90 inhibitors, compounds that bound and induced a helical conformation in a flexible lid region displayed slow association and dissociation rates, high affinity, and high cellular efficacy. Their binding was predominantly entropically driven because the helical conformation conferred greater flexibility to the protein in the bound state compared to other bound conformations [23]. This represents an unusual but powerful strategy for drug design.

FAQ 4: What computational methods can predict cryptic allosteric pockets? Several computational approaches can identify transient allosteric sites:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Long-timescale MD simulations can capture spontaneous protein motions, revealing pockets that open and close dynamically [22] [21].

- Normal Modes Analysis (NMA): This method analyzes protein flexibility and can detect significant changes in flexibility upon allosteric ligand binding, helping to predict allosteric site locations [24] [25].

- Machine Learning (ML) and Network-Based Approaches: Integrated models are now using ML trained on structural data and network analysis of allosteric communication pathways to improve prediction accuracy [21].

Troubleshooting Guides for Key Experimental Challenges

Guide 1: Investigating Mechanisms of Drug Resistance

Problem: A point mutation is causing drug resistance without a clear change in binding affinity, suggesting a kinetic mechanism.

Investigation Protocol:

- Confirm Binding Kinetics: Use surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or similar biophysical methods to measure the association (

k_on) and dissociation (k_off) rates of the drug for both the wild-type and mutant protein. Confirm that a changed residence time (τ = 1/k_off) underlies the resistance [19] [23]. - Perform All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- System Setup: Model the drug bound to both the wild-type and mutant protein structures in a solvated lipid bilayer (for membrane proteins) or water box.

- Simulation Parameters: Run multiple, microsecond-long simulations using a force field like CHARMM or AMBER.

- Analysis: Calculate the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residues to map changes in flexibility. Use path-finding algorithms or analysis of collective variables to identify and compare the dominant drug dissociation pathways for the wild-type and mutant proteins [19].

- Experimental Validation: Based on simulation results, design mutations predicted to destabilize the newly discovered dissociation pathway in the mutant. Test if these "second-site" mutations restore the drug's residence time and efficacy in biochemical or cellular assays [22].

Guide 2: Designing Subtype-Selective Allosteric Modulators

Problem: Designing a selective drug for one protein subtype is difficult because the orthosteric and known allosteric sites are highly conserved.

Investigation Protocol:

- Identify a Cryptic Pocket:

- MD Sampling: Run extensive MD simulations (multiple µs-scale replicates) of the apo forms of the different subtypes.

- Pocket Detection: Use a pocket detection algorithm (e.g., FPOCKET, MDpocket) to analyze trajectories for transiently opening cavities. Compare the probability and characteristics of cryptic pocket formation across subtypes [22].

- Validate the Cryptic Pocket:

- Mutagenesis: Design point mutations in the cryptic pocket region that are predicted to sterically hinder its opening without affecting the global structure.

- Binding Assays: Test the affinity of your selective modulator against the wild-type and mutant proteins. A significant drop in affinity for the mutant, but not for a non-selective control modulator, validates the functional importance of the cryptic pocket [22].

- Ligand Docking and Optimization: Dock candidate modulators into the open conformation of the cryptic pocket. Use the binding pose to guide chemical optimization for better shape complementarity and interactions within this dynamic site [21].

Quantitative Data on Flexibility and Drug Binding

Table 1: Impact of Protein Conformation on Binding Kinetics and Thermodynamics of HSP90 Inhibitors [23]

| Compound ID | Protein Conformation | Residence Time, τ (min) | Binding Affinity, KD (nM) | Thermodynamic Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loop | 2 | 46 | Enthalpic |

| 6 | Loop | 4 | 18 | Enthalpic |

| 8 | Helical | 120 | 4.8 | Entropic |

| 14 | Helical | 180 | 0.6 | Entropic |

| 16 | Helical | 90 | 0.4 | Entropic |

Table 2: Experimental Validation of a Cryptic Pocket in M1 Muscarinic Receptor [22]

| Receptor Construct | Positive Allosteric Modulator (PAM) | Binding Affinity, pKi | Impact of Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 Wild-Type | BQZ12 (M1-selective) | 7.7 | Baseline |

| M1 Y2.64A Mutant | BQZ12 (M1-selective) | <5.0 | ~270-fold decrease |

| M1 Wild-Type | LY2119620 (non-selective) | 8.0 | Baseline |

| M1 Y2.64A Mutant | LY2119620 (non-selective) | 7.9 | No change |

Essential Experimental & Computational Workflows

Workflow for Investigating Flexibility-Based Mechanisms

Cryptic Pocket Formation and Targeting

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Studying Protein Flexibility

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | Performs Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to model protein motion and flexibility [24] [19]. | Simulating cryptic pocket opening in a GPCR [22]. |

| Normal Modes Analysis (NMA) Software | Calculates collective motions of a protein; used to predict flexibility and allosteric sites [24] [25]. | Identifying global flexible regions linked to an active site. | |

| Databases | Allosteric Database (ASD) | Curated database of known allosteric sites and modulators for training ML models and analysis [21]. | Validating a predicted allosteric site against known sites. |

| GPCRmd | Specialized database for MD trajectories of GPCRs [21]. | Accessing pre-run simulation data for a target receptor. | |

| Experimental Methods | Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Tests the functional role of specific residues in flexibility and binding [22] [23]. | Validating the role of a residue in a cryptic pocket. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Measures binding affinity (KD) and thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS) [23]. | Determining if binding is enthalpically or entropically driven. | |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures real-time binding kinetics (kon, koff) [19] [23]. | Investigating changes in drug residence time due to a mutation. |

A Toolbox for Flexibility: From Ensemble Docking to AI-Driven Dynamic Predictions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is ensemble docking and why is it necessary? Ensemble docking is a structure-based drug design method that involves docking candidate ligands into multiple conformations (an ensemble) of a target protein. It is necessary because proteins are flexible and exist in an ensemble of conformational states. Traditional rigid docking using a single protein structure is an incomplete representation and shows performance rates between 50-75%, while flexible docking methods that account for this flexibility can enhance pose prediction accuracy to 80-95% [7]. This approach better accounts for the inherent plasticity of binding sites that can adopt different shapes for different ligands.

Q2: What are the main sources for generating protein conformational ensembles? Protein ensembles can be generated from both experimental and computational sources:

- Experimental Structures: Multiple X-ray crystallography or NMR structures of the same protein, particularly those solved with different ligands or in apo form [26].

- Computational Sampling: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, including enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics, which can explore conformational space beyond what's available through crystallography alone [27].

- Homology Models: For targets with limited experimental structures, carefully built homology models can provide additional conformational diversity [28].

Q3: How many structures should I include in my docking ensemble? There is no universal optimum number, as it depends on the specific protein system. However, studies suggest that 6-8 clusters from MD trajectories may be sufficient to create an effective ensemble [29]. Machine learning approaches can help identify the most important conformations - for CDK2, research showed that a few of the most important conformations were sufficient to reach 1 kcal/mol accuracy in affinity prediction [26]. The key is to balance computational cost with the benefit of including additional conformations, as false positive rates can increase with ensemble size.

Q4: Can I mix experimental and computational structures in the same ensemble? Yes, combining experimental structures with computationally sampled conformations can provide a more comprehensive representation of the protein's conformational landscape. Experimental structures offer experimentally validated states, while MD simulations can reveal transitions and intermediate states not captured crystallographically. This hybrid approach can be particularly valuable for capturing rare but functionally important states [27].

Q5: How do I handle water molecules in ensemble docking? Water molecules can be included in docking experiments in different modes depending on the docking software. For example, in GOLD, waters can be included in 'toggle' mode (where they can be turned on or off), 'spin' mode (where their orientations are optimized), or 'toggle and spin' mode [30]. The decision should be based on the known structural biology of the target - conserved, structural waters are often retained, while more mobile waters might be removed or allowed flexibility during docking.

Q6: What's the difference between conformational selection and induced fit in ensemble docking? Most ensemble docking methods implicitly assume the conformational selection model, where the ligand selects from among pre-existing conformations sampled by the apo-protein. The alternative induced fit model suggests the bound conformation is induced by ligand binding and may not be well-sampled in apo simulations [28]. In reality, most binding events likely involve a combination of both mechanisms, but ensemble docking is better suited to address conformational selection.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Poor Cross-docking Performance

Symptoms: Ligands that should bind fail to dock correctly into non-cognate protein structures (structures solved with different ligands).

Solutions:

- Expand Your Ensemble: If cross-docking fails, your ensemble may lack relevant conformational states. Extend MD simulation times or include more diverse experimental structures [29].

- Check Binding Site Definition: Ensure the binding site is consistently defined across all ensemble members. Even small variations can significantly impact docking results.

- Verify Protein Preparation: Inconsistent protonation states, missing residues, or alternate conformations across structures can cause cross-docking failures. Use consistent preparation protocols.

Table: Cross-docking Performance Improvement with Ensemble Docking

| System | Rigid Cross-docking Result | Ensemble Docking Result | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2 (STU ligand) | Failed (no correct pose) | RMSD 1.255 Å | Successful docking [29] |

| Factor Xa (FXV ligand) | RMSD >2 Å (poor score) | RMSD 1.385 Å | Significant improvement [29] |

| Factor Xa (4PP ligand) | RMSD >2 Å (poor score) | RMSD 1.498 Å | Significant improvement [29] |

Problem: Inconsistent Docking Results Across Ensemble Members

Symptoms: The same ligand gets dramatically different scores and poses across different ensemble conformations without clear rationale.

Solutions:

- Implement Machine Learning Ranking: Use tools like Ensemble Optimizer (EnOpt) that apply machine learning to identify the most relevant conformations and generate composite scores, rather than relying on simple averages or best-score approaches [31].

- Analyze Feature Importance: Leverage ML-based feature importance metrics to identify which conformations actually contribute to binding predictions and focus on these.

- Check for Structural Artifacts: Some conformations might represent crystallization artifacts or non-physiological states. Remove outliers that don't represent biologically relevant states.

Problem: Zero Energy Scores in HADDOCK Ensemble Docking

Symptoms: After running ensemble docking in HADDOCK, results show zero energies and incorrect docking, even though single-structure docking works correctly.

Solutions:

- Check Restraint Numbering: "Zero energies most likely means your restraints were problematic and were not used... Check the residue numbering, check if it matches the restraints numbering" [32].

- Verify Ensemble Preparation: When combining multiple PDBs into an ensemble, ensure consistent atom numbering and residue indexing across all structures.

- Validate Input Structures: Check that all structures in the ensemble are properly formatted and contain all necessary atoms for the docking calculation.

Problem: Excessive Computational Time

Symptoms: Ensemble docking takes prohibitively long due to large ensemble sizes.

Solutions:

- Apply Clustering: Use structural clustering algorithms (like RMSD-based clustering) to identify representative structures rather than docking to all sampled conformations [29].

- Implement Graph-Based Selection: For large sets of experimental structures, graph-based redundancy removal can be more efficient than clustering for selecting non-redundant conformations [26].

- Use Smart Preselection: Employ methods like molecular dynamics to identify druggable conformations before comprehensive docking [27].

Problem: Poor Correlation with Experimental Affinity Data

Symptoms: Docking scores don't correlate well with experimental binding affinities, even with multiple conformations.

Solutions:

- Combine with Machine Learning Rescoring: Use ensemble docking poses as input for machine learning scoring functions, which often outperform traditional scoring functions [26].

- Ensure Adequate Sampling: The lack of correlation might indicate your ensemble doesn't include the relevant biological conformations. Consider enhanced sampling methods.

- Validate with Known Actives/Inactives: Test your ensemble with compounds of known activity before applying to novel compounds.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Ensemble Docking Workflow

Diagram Title: Ensemble Docking Workflow

Molecular Dynamics Ensemble Generation Protocol

Purpose: To generate biologically relevant protein conformations for ensemble docking when experimental structures are limited or lack diversity.

Steps:

- System Setup:

- Obtain starting structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Prepare protein: add hydrogens, optimize side chains, fill missing loops

- Retain crystallographic waters near binding site if available [29]

Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Use AMBER14SB or similar force field for protein

- Parameterize small molecules with OpenFF 2.0 or similar

- Apply hydrogen-mass repartitioning (HMR) with 4fs timesteps

- Run equilibration (100ps) followed by production simulation (4ns minimum)

- Save frames every 2ps (2000 frames for 4ns simulation) [29]

Trajectory Clustering:

- Define active site as residues within 6Å of reference ligand

- Use mass-weighted RMSD-based clustering algorithm

- Extract 6-20 cluster representatives (medoids) [29]

- Minimize atoms within 8Å of binding site for each selected snapshot

Validation:

- Perform self-docking of known ligands to verify pose reproduction

- Conduct cross-docking tests between different ligand systems

- Compare against original crystal structures for rationality

Machine Learning-Enhanced Ensemble Docking with EnOpt

Purpose: To optimize conformation selection and scoring in ensemble docking using machine learning.

Steps:

- Input Preparation:

- Format docking scores as n×m matrix (n compounds × m conformations)

- Prepare CSV file listing known active compounds as positive controls [31]

Model Training:

- Use gradient boosted trees (XGBoost) or random forest

- Implement 3-fold cross-validation

- Set number of estimators to 15 (default) to avoid overfitting

- Use default hyperparameters unless system-specific optimization needed [31]

Prediction and Analysis:

- Apply leave-one-out prediction within cross-validation framework

- Calculate activity probabilities for all compounds (EnOpt scores)

- Generate feature importance metrics for each conformation

- Output performance metrics (AUROC, PRAUC, BEDROC, enrichment factors)

Ensemble Refinement:

- Identify most important conformations through feature importance

- Refine ensemble by focusing on high-importance conformations

- Iterate if necessary with refined ensemble

Table: Performance Comparison of Docking Approaches

| Method | Pose Prediction Accuracy | Affinity Prediction | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Docking | 50-75% [7] | Poor correlation | Low | Initial screening, rigid targets |

| Traditional Ensemble Docking | 80-95% [7] | Moderate improvement | Medium-High | Flexible targets with known conformations |

| MD + Ensemble Docking | Improved cross-docking [29] | Context dependent | High | Targets with limited experimental data |

| ML-Enhanced Ensemble Docking | Similar to traditional ensemble | Significant improvement [31] | Medium (after training) | Targets with known actives for training |

Table: Key Software Tools for Ensemble Docking

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOLD | Docking Software | Genetic algorithm-based docking | Multiple binding site definitions, water handling modes, ensemble docking workflow [30] |

| HADDOCK | Information-driven Docking | Biomolecular docking | Handles protein ensembles, experimental restraints, flexible interface [27] |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | MD simulations | High performance, explicit solvent simulations, trajectory analysis [27] |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling | Metadynamics and enhanced MD | Free energy calculations, path collective variables [27] |

| EnOpt | Machine Learning Tool | Ensemble docking optimization | Gradient boosted trees, feature importance, activity probability prediction [31] |

| Flare | Comprehensive Platform | MD + Docking integration | End-to-end workflow, Python API, Lead Finder docking engine [29] |

Table: Critical Experimental Considerations

| Consideration | Impact on Results | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Size | Too small: missing relevant statesToo large: false positives, high cost | Start with 6-20 diverse conformations, use ML to refine [26] [29] |

| Conformation Selection | Biased ensemble leads to biased results | Combine experimental & computational structures, ensure diversity [28] |

| Binding Site Definition | Inconsistent definition compromises comparisons | Use consistent residue numbering, same spatial definition across ensemble |

| Water Handling | Can dramatically affect binding modes | Test different protocols: remove, toggle, or spin waters [30] |

| Protonation States | Incorrect states prevent proper binding | Use consistent protonation protocol, consider biological conditions |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can I generate a diverse conformational ensemble for a protein target before docking? Performing multiple, independent MD simulation replicates is a foundational strategy. For instance, the ATLAS database protocol involves running three replicates of 100 ns simulations for each protein, each starting with different random initial velocities. This approach helps sample a broader conformational space than a single, long trajectory and provides more reliable data for subsequent docking studies [33].

2. My MD simulations show limited backbone flexibility, hindering the sampling of relevant conformations for docking. What strategies can I use? Consider implementing enhanced sampling techniques. Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) can be used to explore specific conformational changes. A key consideration is the restraint strategy; instead of rigidly fixing all protein heavy atoms, a more effective method is to apply harmonic restraints only to the Cα atoms located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand. This allows for a more natural and flexible protein environment during sampling, leading to a more biologically relevant release pathway for the ligand [34].

3. Are there efficient alternatives to all-atom MD for sampling flexibility in large protein systems? Yes, coarse-grained methods like CABS-flex offer a computationally efficient alternative. The CABS-flex method uses a coarse-grained model and Monte Carlo simulations to study protein flexibility, achieving speeds 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than all-atom MD. It is particularly useful for quickly generating structural ensembles for large proteins or initial screening, and these ensembles can be reconstructed to all-atom models for further analysis or docking [35].

4. How can I validate that my conformational ensemble is biologically relevant and not just computational artifacts? Cross-validate your results with experimental data. Compare your simulation-derived metrics, such as Root Mean Square Fluctuations (RMSF) or B-factors, with experimental B-factors from X-ray crystallography or data from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). Furthermore, analyze your ensemble for known functional motions, such as hinge-bending regions or allosteric pathways, to ensure the sampled dynamics align with the protein's known biology [33] [36].

5. What is a standard protocol for running an all-atom MD simulation to generate a conformational ensemble? A standardized protocol, as used for the ATLAS database, includes [33]:

- Force Field: CHARMM36m.

- Water Model: TIP3P.

- System Setup: Place the protein in a triclinic box, solvate, and neutralize with ions (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Energy Minimization: 5,000 steps using the steepest descent algorithm.

- Equilibration:

- NVT ensemble for 200 ps.

- NPT ensemble for 1 ns.

- (Apply position restraints on heavy atoms during equilibration).

- Production Run: Run multiple replicates (e.g., 3x 100 ns) without restraints, saving coordinates frequently (e.g., every 10 ps).

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate Sampling of Functionally Relevant States

Problem: The MD simulation fails to capture large-scale conformational changes or rare events that are critical for ligand binding.

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low RMSd values throughout the trajectory. | Simulation time is too short. | Extend simulation time if computationally feasible. |

| Ligand binding site remains rigid in docking. | Insufficient sampling of backbone motions. | Employ enhanced sampling methods (e.g., metadynamics, replica exchange). |

| Starting from a single, rigid crystal structure. | Use an ensemble of starting structures (e.g., from NMR, different PDB entries, or AlphaFold2 models). | |

| Functional loops remain in a single conformation. | High energy barriers for loop movement. | Use targeted MD or SMD to explore specific loop motions. |

Step-by-Step Resolution Protocol:

- Pre-processing: Generate an initial conformational ensemble using a fast, coarse-grained method like CABS-flex to identify potentially flexible regions [35].

- System Setup: Prepare the system as per the standard protocol [33].

- Enhanced Sampling: If a specific functional motion is known (e.g., a hinge bending), define a Collective Variable (CV) and apply an enhanced sampling technique to bias the simulation along that CV.

- Validation: Cluster the resulting trajectories and check if the clusters represent known functional states. Validate by measuring the solvent accessibility of the binding site or calculating residue cross-correlations to identify allosteric pathways.

Issue 2: Unstable Simulations or Non-Physical Protein Behavior

Problem: The simulation crashes or the protein structure unfolds/denatures unexpectedly.

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation crashes with "LINCS warning". | Incorrect bond parameters, especially for non-standard ligands. | Use tools like ACPYPE or GAFF to carefully parameterize small molecules. Use a smaller timestep (e.g., 1 fs) [34]. |

| Rapid increase in protein RMSd. | Incorrect system setup (e.g., bad contacts, missing solvent). | Re-check the initial structure preparation, including protonation states and missing residues. Ensure proper energy minimization and equilibration [33]. |

| Local unfolding in specific regions. | Inaccurate force field for certain amino acids or protein types. | Research known force field limitations and consider switching to a more modern force field (e.g., CHARMM36m, Amber ff99SB-ILDN). |

Step-by-Step Resolution Protocol:

- Structure Preparation: Use software like Pymol to repair missing residues in the initial PDB file. Use tools like

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(AMBER) to correctly add hydrogens and assign protonation states [34]. - Parameterization: For any non-standard ligand, perform quantum chemical geometry optimization and derive electrostatic potential-fitted charges (e.g., using the RESP method) before generating parameters with GAFF [34].

- Careful Equilibration: Do not skip or shorten the equilibration phases. Monitor the system temperature, pressure, and density during NVT and NPT equilibration to ensure stability before starting the production run [33].

- Analysis: Visually inspect the first few nanoseconds of the production run to catch early signs of instability.

Issue 3: High Computational Cost for Large Systems

Problem: The system size makes all-atom MD prohibitively expensive, limiting sampling time and conformational diversity.

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Very slow simulation performance. | Large system size (e.g., membrane proteins, large complexes). | Utilize coarse-grained (CG) models like CABS-flex for initial, rapid sampling [35]. |

| Inability to run long enough simulations to observe relevant dynamics. | Limited computational resources. | Combine short all-atom MD with CG simulations in a multiscale approach. |

Step-by-Step Resolution Protocol:

- Preliminary CG Simulation: Run a CABS-flex simulation on the large system to identify key flexible domains and generate an ensemble of conformations [35].

- Focus on Region of Interest: Extract a smaller subsystem containing the binding site and flexible regions identified in step 1.

- All-Atom Refinement: Perform more expensive all-atom MD simulations on this smaller, more computationally tractable subsystem to refine the conformational details and interactions.

- Integrate for Docking: Use the combined CG and all-atom ensembles as multiple receptor conformations for molecular docking studies [37].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized All-Atom MD for Conformational Ensemble Generation

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to build the ATLAS database [33].

Objective: To generate a standardized, biologically relevant conformational ensemble of a protein for use in flexible molecular docking.

Key Reagents and Resources:

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| GROMACS 2019.4+ | Software suite to perform MD simulations. |

| CHARMM36m Force Field | Defines energy parameters for atoms in the protein, water, and ions. |

| TIP3P Water Model | Explicit water model for solvation. |

| MODELLER / AlphaFold2 | Software for homology modeling or predicting missing residues in the initial structure. |

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain your protein's initial 3D structure (e.g., from PDB or an AlphaFold2 prediction).

- Remove all water molecules and non-essential ligands to ensure a uniform starting point.

- Model any missing loops or residues using MODELLER (for gaps ≤5 residues) or AlphaFold2 (for gaps of 6–10 residues).

- Generate the protein topology using the CHARMM36m force field.

Solvation and Ionization:

- Place the protein in a periodic triclinic box, ensuring a minimum distance (e.g., 1.0 nm) between the protein and box edges.

- Solvate the system with TIP3P water molecules.

- Add Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions to neutralize the system's net charge and bring the salt concentration to 150 mM.

Energy Minimization:

- Run an energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm for 5,000 steps to relieve any steric clashes.

Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Run for 200 ps, maintaining a constant temperature of 300 K using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Apply position restraints on protein heavy atoms.

- NPT Equilibration: Run for 1 ns, maintaining a constant pressure of 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. Keep the position restraints on.

Production Simulation:

- Remove all positional restraints.

- Run multiple independent replicates (a minimum of 3 is recommended) of 100 ns each. Use different random seeds for initial velocities in each replicate.

- Save the atomic coordinates every 10 ps for analysis.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this standardized protocol:

Protocol 2: Integrating MD Ensembles with Molecular Docking

This protocol outlines how to use the conformational ensemble generated from MD to improve molecular docking outcomes, addressing the limitations of rigid-receptor docking [37] [8].

Objective: To account for protein flexibility in molecular docking by using an ensemble of receptor conformations derived from MD simulations.

Key Reagents and Resources:

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| MD Simulation Trajectory | The source of multiple protein conformations. |

| Clustering Tool (e.g., GROMACS cluster) | Identifies representative structures from the trajectory. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Software (e.g., AutoDock, GOLD) to perform docking. |

Procedure:

- Generate Conformational Ensemble: Follow Protocol 1 to obtain an MD trajectory of your target protein.

- Cluster the Trajectory:

- After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure (e.g., the protein backbone), perform a cluster analysis (e.g., using the GROMACS

clustercommand with the gromos algorithm). - This analysis groups similar protein conformations from the trajectory based on their RMSd.

- After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure (e.g., the protein backbone), perform a cluster analysis (e.g., using the GROMACS

- Extract Representative Structures:

- Select the central structure from the most populated clusters. These structures represent the dominant conformational states sampled during the simulation.

- Prepare Structures for Docking:

- Prepare each representative structure for docking by adding charges, assigning atom types, and defining the binding site grid.

- Ensemble Docking:

- Perform molecular docking of your ligand library against each representative protein structure in the ensemble.

- Analyze Results:

- Analyze the docking poses and scores across all receptor conformations. A ligand that scores well across multiple conformations may be a more robust binder. Alternatively, a ligand that only fits well in a specific, rarely sampled conformation might induce a conformational selection.

The logical flow of this integrative approach is shown below:

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Docking Methods

The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for modern docking approaches, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy and computational speed.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Flexible Docking Methods

| Method | Model Type | Key Function | Ligand RMSD < 2Å (%) | Pocket RMSD (Å) | Relative Speed (vs. DynamicBind) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FABFlex [38] | Regression-based, Multi-task | Blind flexible docking (pocket, ligand, & pocket prediction) | 40.59% | 1.10 | 208x | Speed and accuracy in blind flexible docking |

| DynamicBind [38] [39] | Diffusion-based | Models protein backbone/sidechain flexibility & cryptic pockets | Information Missing | Information Missing | 1x (Baseline) | Handles significant conformational changes |

| Re-Dock [39] [40] | Diffusion-based | Flexible & realistic docking with diffusion bridge | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Realistic modeling of binding scenarios |

| DiffDock [39] | Diffusion-based | Predicts ligand pose via denoising score function | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | State-of-the-art pose accuracy on known pockets |

| EquiBind [39] | Regression-based | Identifies key points for rigid ligand docking | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Fast inference speed |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol for FABFlex-based Blind Flexible Docking

Objective: To predict the bound (holo) structure of a ligand and its protein target from their unbound (apo) states without prior knowledge of the binding site [38].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the apo protein (e.g., from AlphaFold2 prediction or an experimental apo structure) [38].

- Obtain the 3D structure of the ligand in its unbound state.

Pocket Identification:

- Feed the apo protein structure into the pocket prediction module.

- This module, built using an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network, identifies the residues most likely to constitute the binding site, addressing the "blind" nature of the docking task [38].

Initial Holo Structure Prediction:

- The identified pocket and the apo ligand are passed to the ligand and pocket docking modules.

- The ligand docking module predicts the coordinates of the ligand in its holo (bound) conformation.

- Simultaneously, the pocket docking module predicts the coordinates of the protein binding pocket in its holo conformation [38].

Iterative Refinement:

- The initial predictions from the ligand and pocket modules are fed into an iterative update mechanism.

- This mechanism allows for continuous, mutual refinement of both the ligand and pocket coordinates over several cycles, improving the final complex's accuracy [38].

Output:

- The model outputs the final predicted 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex (the holo structure).

Protocol for Ensemble-based Docking with MD

Objective: To incorporate target protein flexibility by docking ligands into an ensemble of protein conformations derived from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [41].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Generate Protein Conformational Ensemble:

- Perform an all-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation of the target protein in a solvated system.

- Analyze the simulation trajectory for stability using metrics like Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to ensure the simulated dynamics are realistic [41].

Cluster Conformations:

- Use clustering algorithms (e.g., based on RMSD) on the MD trajectory to group structurally similar protein conformations.

- Select representative structures from the largest clusters to create a structural ensemble that captures the protein's flexibility [41].

Dock to the Ensemble:

Analyze Results:

- Compare the docking results across all ensemble members.

- The pose with the most favorable (lowest) binding energy or the one that appears most frequently across clusters is typically selected as the final predicted binding mode [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: When should I use a regression-based model like FABFlex versus a generative/diffusion-based model like Re-Dock or DynamicBind?

- A: The choice depends on your project's priorities.

- Use FABFlex when computational speed is critical, such as in virtual screening of large compound libraries, and when you need a unified model for blind flexible docking. It provides a good balance of speed and accuracy [38].

- Use DynamicBind or Re-Dock when you are dealing with proteins that undergo large conformational changes (e.g., involving backbone movement or cryptic pockets) and accuracy is the paramount concern, even at the cost of significantly longer computation times [38] [39].

Q2: My model predicts a ligand pose with good affinity, but the bond lengths and angles look distorted. How can I validate the physical realism of the generated structure?

- A: This is a common challenge with AI-generated molecular structures [42]. Perform post-docking checks:

- Use Validation Tools: Employ software libraries like PoseBusters, which contain multiple tests for structural errors, including bond lengths, bond angles, and steric clashes [42].

- Check Chemical Stability: Manually inspect or use rule-based filters (e.g., REOS) to identify chemically unstable functional groups or unrealistic ring strain in the generated molecules [42].

- Assign Bond Orders Correctly: The raw output of some generative models is a 3D point cloud (atom types and coordinates). Use robust cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., OEChem) to correctly assign bonds and bond orders, as this can be error-prone with standard open-source tools [42].

Q3: What is the best way to handle docking when the true binding pocket is unknown or differs from the standard annotation (blind docking)?

- A: Blind docking is a key strength of newer deep learning models.

- Integrated Prediction: Methods like FABFlex have a built-in pocket prediction module that directly identifies the binding site from the apo protein structure as part of its end-to-end process [38].

- Hybrid Approach: Alternatively, you can use a dedicated pocket detection algorithm (e.g., ICMPocketFinder [43]) first, and then use a high-accuracy docking tool to dock the ligand into the predicted pocket.

Q4: How can I account for minor but critical side-chain rearrangements during docking without running a full flexible docking simulation?

- A: Consider the following strategies:

- Ensemble Docking: Use an ensemble of protein structures where side-chain conformations have been subtly varied, either from MD simulations or side-chain rotamer sampling [41].

- Flexible Residue Selection: Some traditional docking software allows you to specify key side chains as "flexible" during the docking process, which samples their rotamers while keeping the rest of the protein rigid [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Flexible Docking Experiments

| Item Name | Type | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FABFlex Model [38] | Software Tool | Performs fast, accurate blind flexible docking via regression. | Ideal for high-throughput scenarios; code is publicly available. |

| Re-Dock Model [39] [40] | Software Tool | Performs flexible docking using a diffusion bridge model. | Better for capturing large conformational changes; slower. |

| PDBBind Database [38] [39] | Dataset | A public benchmark of protein-ligand complexes for training and testing. | Essential for model validation and fair performance comparison. |

| AlphaFold2 [38] [39] | Software Tool | Predicts apo protein structures from sequence. | Provides realistic input structures for apo-docking experiments. |

| PoseBusters [42] | Validation Tool | Checks AI-generated 3D structures for physical realism (bonds, angles, clashes). | Critical for quality control of predicted complexes. |

| OpenEye OEChem Toolkit [42] | Cheminformatics Library | Correctly assigns bonds and bond orders from 3D coordinates (XYZ files). | Solves a common problem in processing generative model output. |

| REOS Filters [42] | Filtering Tool | Rapidly eliminates molecules with reactive, toxic, or unstable chemical groups. | Ensures generated ligands are chemically sensible and synthesizable. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Normal Modes Analysis (NMA)

Q1: My Normal Modes Analysis fails to reproduce the observed conformational change in my protein. What could be wrong?

- Problem: The direction of motion predicted by the lowest-frequency normal modes does not match experimental data.

- Solutions:

- Check Protein Completeness: NMA is sensitive to missing residues, particularly in terminal regions, which can prejudice the predicted collectivity and direction of motion [44]. Ensure your input structure is complete or consider using modeling tools to fill in gaps.

- Investigate Higher-Order Modes: While low-frequency modes often capture large-scale motions, the observed conformational change may be described by a combination of modes. Don't just rely on the single lowest mode; examine the first 20 modes. In one-third of cases, a single mode suffices, but for others, a linear combination is necessary [44].

- Verify Mobile Regions: Use the correlation function Cj to check if the NMA successfully identifies the actual mobile regions of your protein. A low average Cj for the lowest mode (e.g., below 0.35) suggests the motion is not well-captured by the dominant mode [44].

- Understand the Limitations: NMA uses a harmonic approximation and cannot model energy barriers or multiple minima. It is best suited for reproducing conformational changes that result from intrinsic thermal motions rather than those requiring substantial induced fit [44].

Q2: How can I use NMA to predict if my protein will undergo large conformational change upon binding?

- Protocol: You can use the characteristic frequencies of normal modes to reliably predict the extent of conformational change.

- Calculate the normal modes for your protein of interest using an elastic network model (e.g., with Cα atoms only and a simple pairwise Hookean potential) [44].

- Analyze the distribution of low-frequency modes. Proteins with a higher propensity for large conformational change (>2 Å Cα RMSD) tend to have a distinct profile in their low-frequency normal modes compared to more rigid proteins [44].

- This predictive power can inform your docking strategy, indicating whether a rigid-body approach is likely to be sufficient or if flexible docking is necessary [44].

Flexible Side-Chain and Backbone Refinement

Q3: During flexible refinement, my model becomes physically unrealistic or the energy increases. How can I stabilize the refinement process?

- Problem: Refinement of highly flexible regions leads to steric clashes, unrealistic geometries, or high-energy states.

- Solutions:

- Apply Motion-Based Regularization: Use methods that exploit the physical property that conformational change tends to preserve local geometry. Implement regularizers that encourage locally smooth and rigid motion in high-density regions of the map to prevent overfitting and non-physical deformations [45].